Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods:

2.1. Data Sources

2.2. Survival Analysis

2.3. Expression and Clinical Analysis

2.4. Estimation of Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB)

2.5. Functional Enrichment Analysis

2.6. Estimation of Stromal and Immune Scores and Immune Infiltration Analysis

2.7. Chemotherapy Response Prediction

2.8. scRNA-seq Analysis and Expression Levels of ALDH3A1 in Pancreatic Cancer Cell Lines

2.9. Cell Culture

2.10. Human Samples

2.11. Immunohistochemistry

2.12. qPCR

2.13. Western Blot

2.14. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

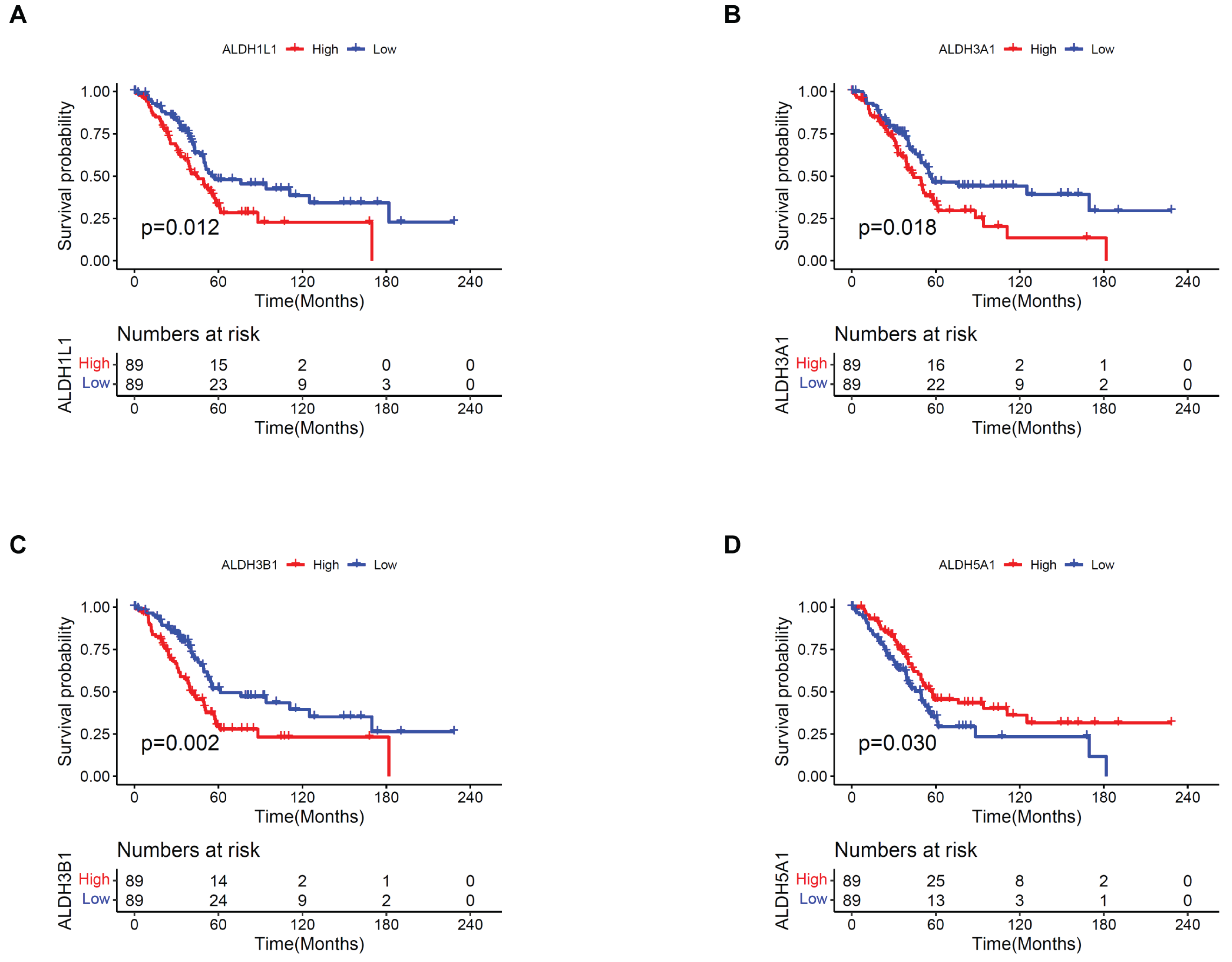

3.1. Prognostic Value of ALDHs in PAAD

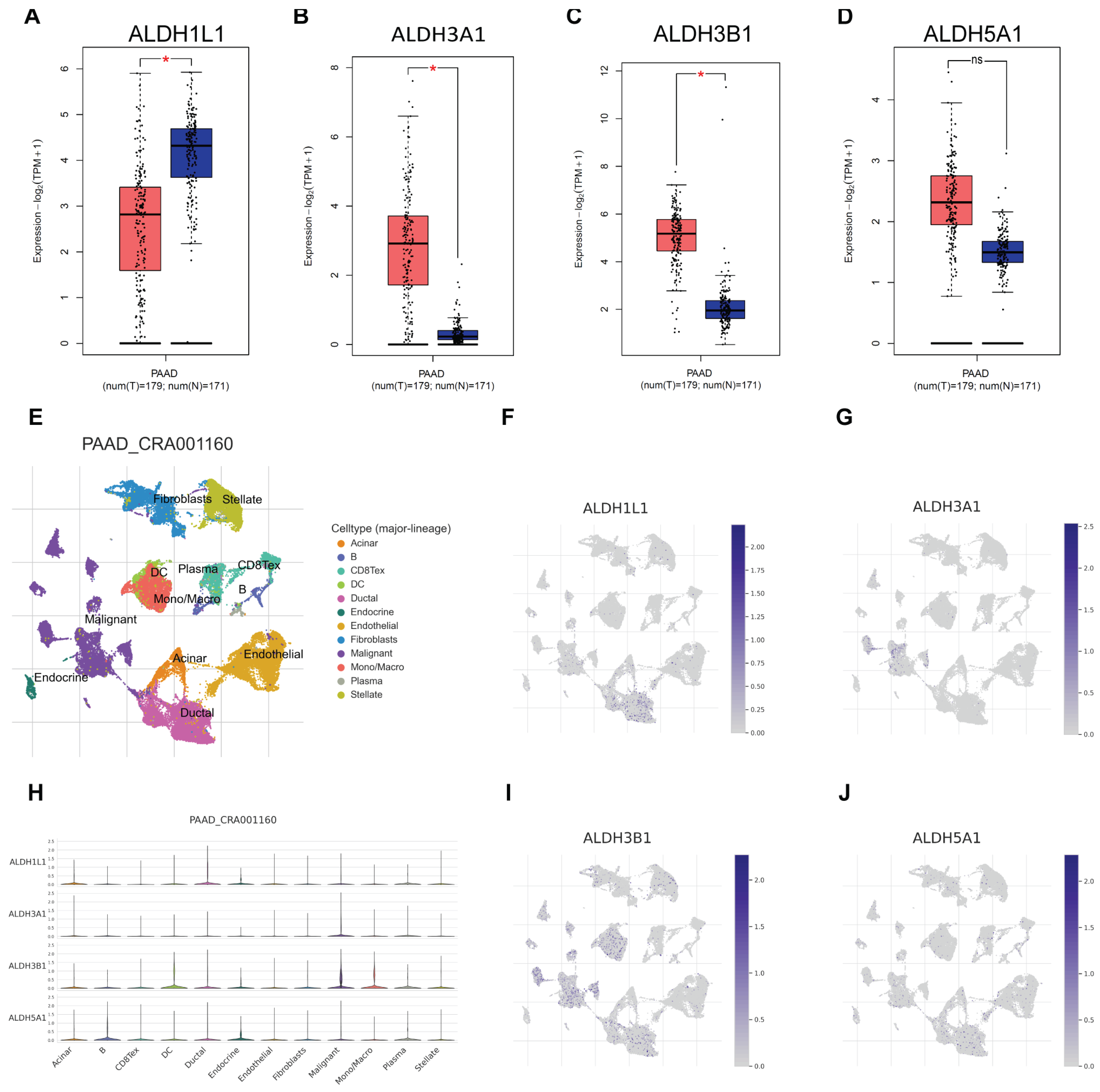

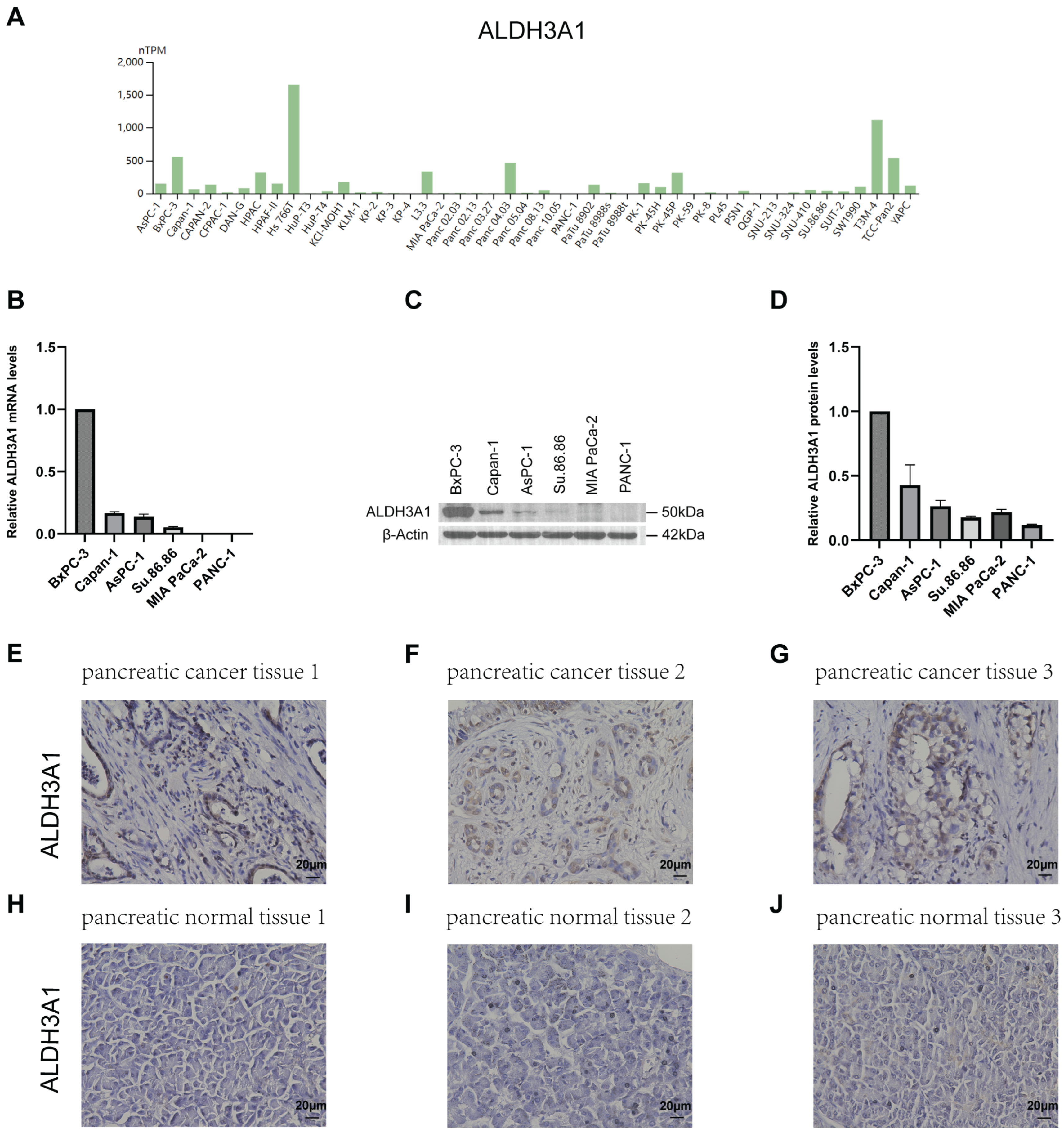

3.2. Correlation Between ALDH Expression in PAAD and ALDH3A1 Levels in Pancreatic Cancer Tissues, Normal Tissues, and Cell Lines

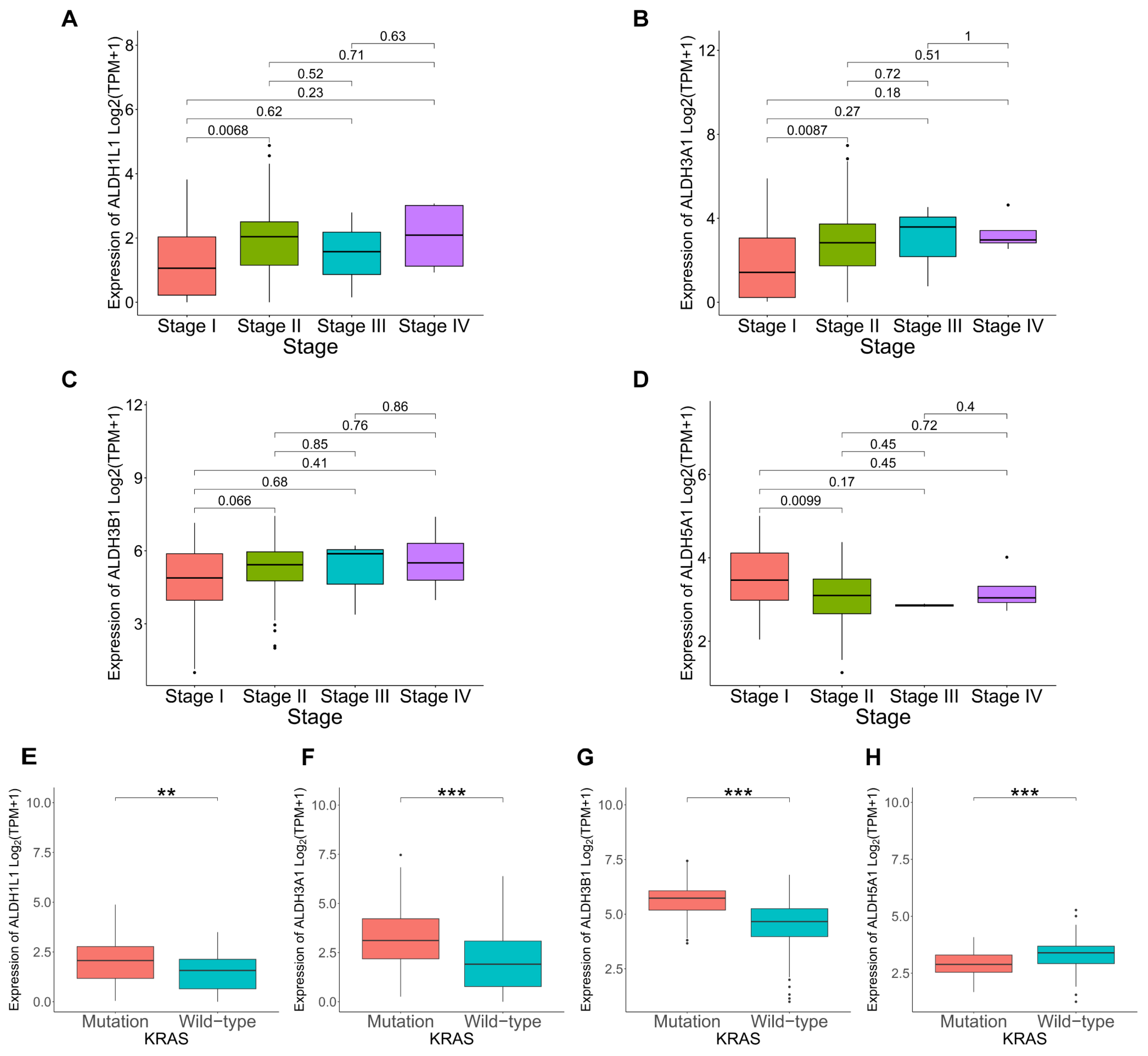

3.3. Correlation Between ALDHs Expression and Clinicopathological Parameters in PAAD

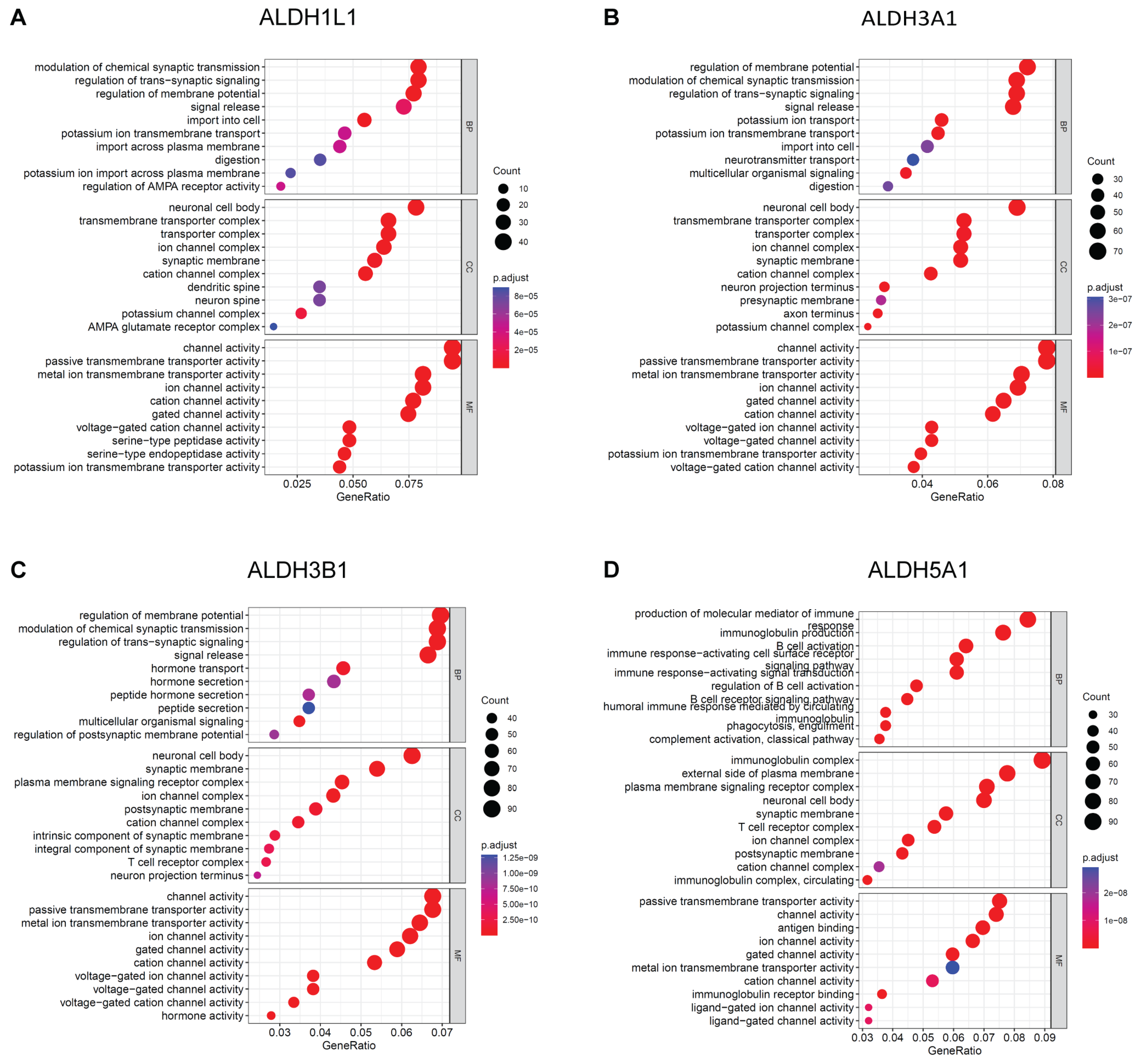

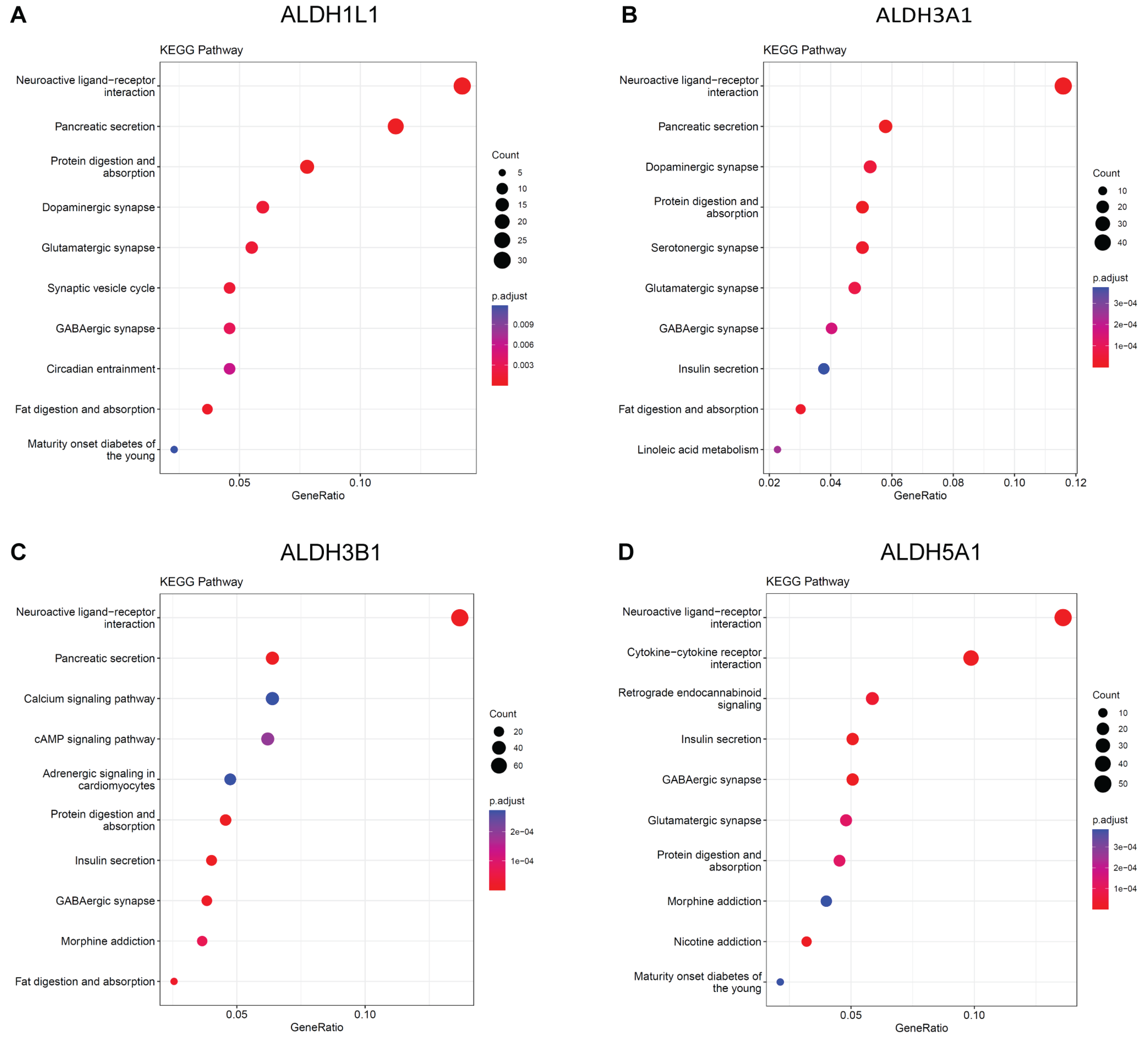

3.4. Enrichment Analysis on ALDHs

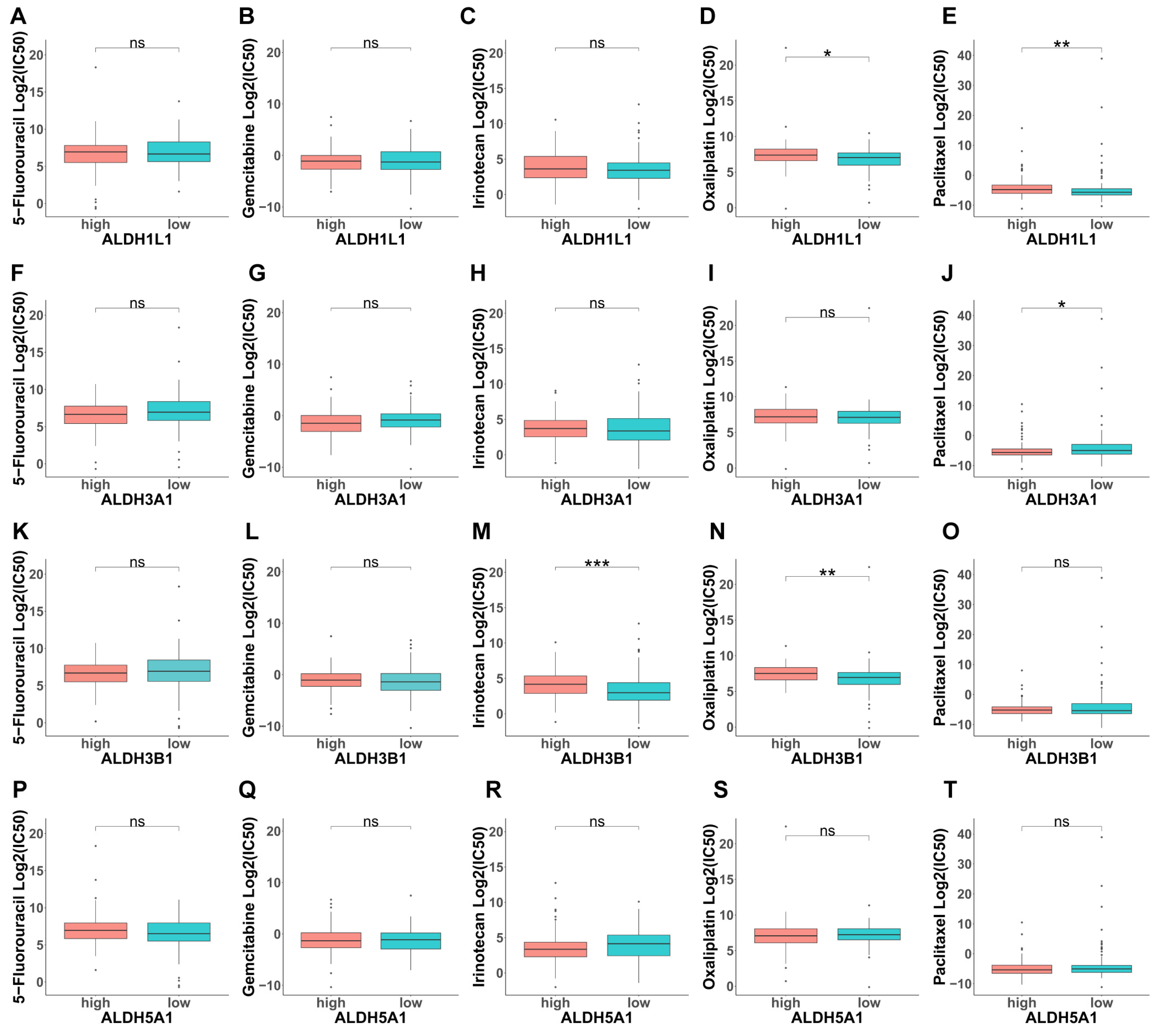

3.5. Analysis of the Contribution of ALDHs to Drug Resistance

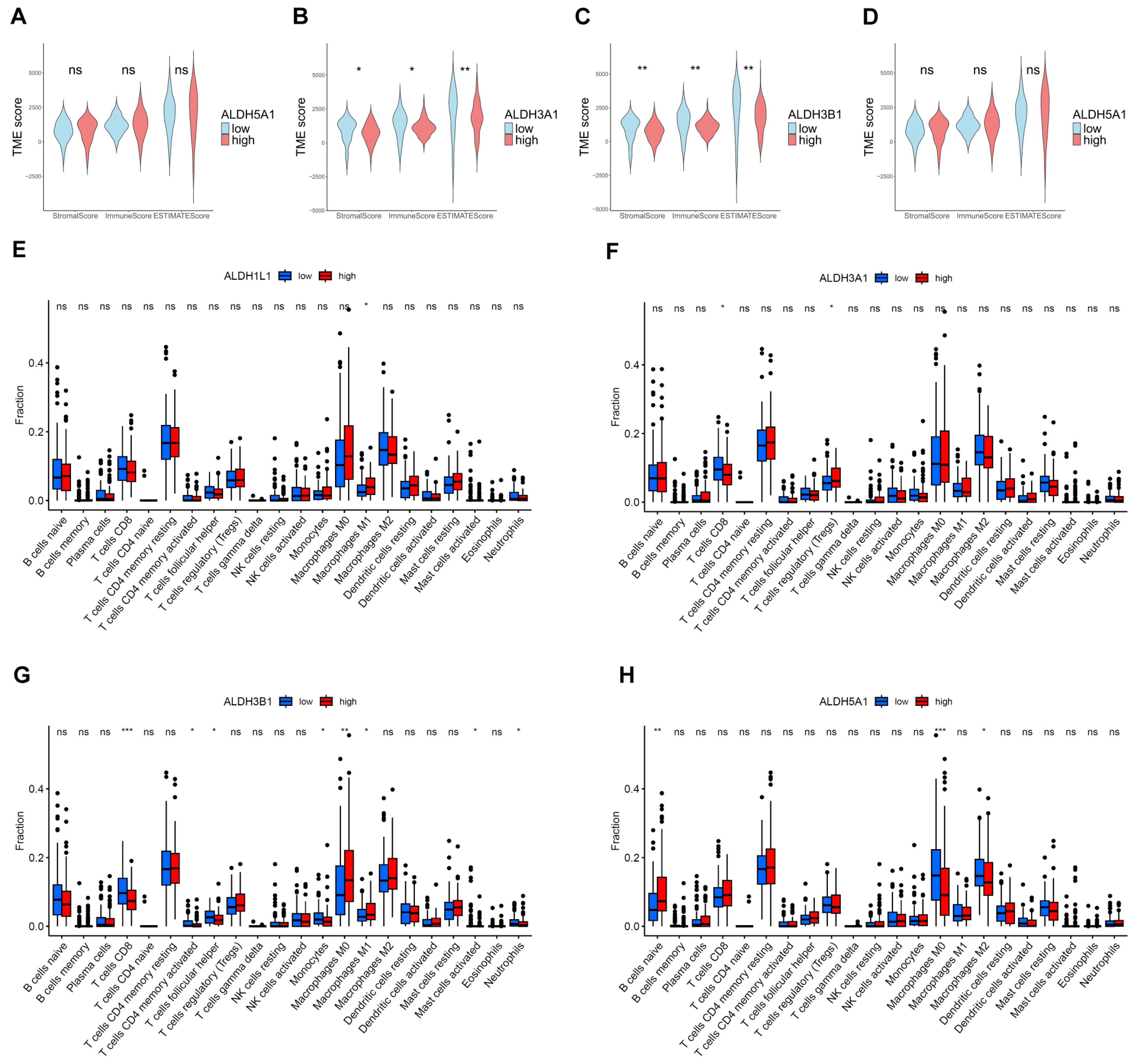

3.6. Correlations Between ALDHs Expression of Immune Infiltration

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Limitations of the Study

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Fuchs, H.E.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahib, L.; Smith, B.D.; Aizenberg, R.; Rosenzweig, A.B.; Fleshman, J.M.; Matrisian, L.M. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: The unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 2913–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conroy, T.; Hammel, P.; Hebbar, M.; Ben Abdelghani, M.; Wei, A.C.; Raoul, J.-L.; Choné, L.; Francois, E.; Artru, P.; Biagi, J.J.; et al. FOLFIRINOX or Gemcitabine as Adjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2395–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neoptolemos, J.P.; Palmer, D.H.; Ghaneh, P.; Psarelli, E.E.; Valle, J.W.; Halloran, C.M.; Faluyi, O.; O’Reilly, D.A.; Cunningham, D.; Wadsley, J.; et al. Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017, 389, 1011–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizrahi, J.D.; Surana, R.; Valle, J.W.; Shroff, R.T. Pancreatic cancer. Lancet 2020, 395, 2008–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleeff, J.; Korc, M.; Apte, M.; La Vecchia, C.; Johnson, C.D.; Biankin, A.V.; Neale, R.E.; Tempero, M.; Tuveson, D.A.; Hruban, R.H.; et al. Pancreatic cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 16022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, W.J.; Stagos, D.; Marchitti, S.A.; Nebert, D.W.; Tipton, K.F.; Bairoch, A.; Vasiliou, V. Human aldehyde dehydrogenase genes: alternatively spliced transcriptional variants and their suggested nomenclature. Pharmacogenetics Genom. 2009, 19, 893–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasiliou, V.; Nebert, D.W.J.H.g. Analysis and update of the human aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) gene family. 2005, 2, 1-6.

- Zanoni, M.; Bravaccini, S.; Fabbri, F.; Arienti, C. Emerging Roles of Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Isoforms in Anti-cancer Therapy Resistance. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 795762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, B.; Wu, W.; Cheng, T.; Schlitter, A.M.; Qian, C.; Bruns, P.; Jian, Z.; Jäger, C.; Regel, I.; Raulefs, S.; et al. A subset of metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas depends quantitatively on oncogenic Kras/Mek/Erk-induced hyperactive mTOR signalling. Gut 2015, 65, 647–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, S.; Qian, X.; Shi, M.; Li, H.; Peng, C.; Ding, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, B.; Xu, G.; Lv, Y.; et al. ALDH1A3 Accelerates Pancreatic Cancer Metastasis by Promoting Glucose Metabolism. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebollido-Rios, R.; Venton, G.; Sánchez-Redondo, S.; i Felip, C.I.; Fournet, G.; González, E.; Fernández, W.R.; Escuela, D.O.B.; Di Stefano, B.; Penarroche-Díaz, R.; et al. Dual disruption of aldehyde dehydrogenases 1 and 3 promotes functional changes in the glutathione redox system and enhances chemosensitivity in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Oncogene 2020, 39, 2756–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Fu, L. The role of ALDH2 in tumorigenesis and tumor progression: Targeting ALDH2 as a potential cancer treatment. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 1400–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Li, C.; Kang, B.; Gao, G.; Li, C.; Zhang, Z. GEPIA: A web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W98–W102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayakonda, A.; Lin, D.-C.; Assenov, Y.; Plass, C.; Koeffler, H.P. Maftools: efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 2018, 28, 1747–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.-G.; Han, Y.; He, Q.-Y. clusterProfiler: An R Package for Comparing Biological Themes Among Gene Clusters. OMICS J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshihara, K.; Shahmoradgoli, M.; Martínez, E.; Vegesna, R.; Kim, H.; Torres-Garcia, W.; Treviño, V.; Shen, H.; Laird, P.W.; Levine, D.A.; et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, A.M.; Liu, C.L.; Green, M.R.; Gentles, A.J.; Feng, W.; Xu, Y.; Hoang, C.D.; Diehn, M.; Alizadeh, A.A. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeser, D.; Gruener, R.F.; Huang, R.S. oncoPredict: an R package for predicting in vivo or cancer patient drug response and biomarkers from cell line screening data. Briefings Bioinform. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Soares, J.; Greninger, P.; Edelman, E.J.; Lightfoot, H.; Forbes, S.; Bindal, N.; Beare, D.; Smith, J.A.; Thompson, I.R.; et al. Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC): a resource for therapeutic biomarker discovery in cancer cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D955–D961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohri, N.; Häußler, J.; Javakhishvili, N.; Vieweg, D.; Zourelidis, A.; Trojanowicz, B.; Haemmerle, M.; Esposito, I.; Glaß, M.; Sunami, Y.; et al. Gene expression dynamics in fibroblasts during early-stage murine pancreatic carcinogenesis. iScience 2024, 28, 111572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyer, F.; Lüdje, W.; Karpf, J.; Saher, G.; Beckervordersandforth, R. Distribution of Aldh1L1-CreERT2 Recombination in Astrocytes Versus Neural Stem Cells in the Neurogenic Niches of the Adult Mouse Brain. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, J.; Brian, C.; Pappa, A.; Panayiotidis, M.I.; Franco, R. Mitochondrial Metabolism in Astrocytes Regulates Brain Bioenergetics, Neurotransmission and Redox Balance. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, S.; Zhang, C.; Xie, K.-P. Therapeutic resistance of pancreatic cancer: Roadmap to its reversal. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Rev. Cancer 2021, 1875, 188461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Zavala, J.S.; Calleja, L.F.; Moreno-Sánchez, R.; Yoval-Sánchez, B. Role of Aldehyde Dehydrogenases in Physiopathological Processes. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2019, 32, 405–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, P.M.-H.; Chen, C.-H.; Yeh, C.-C.; Lu, H.-J.; Liu, T.-T.; Chen, M.-H.; Liu, C.-Y.; Wu, A.T.H.; Yang, M.-H.; Tai, S.-K.; et al. Transcriptome analysis and prognosis of ALDH isoforms in human cancer. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Januchowski, R.; Wojtowicz, K.; Zabel, M. The role of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) in cancer drug resistance. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2013, 67, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raha, D.; Wilson, T.R.; Peng, J.; Peterson, D.; Yue, P.; Evangelista, M.; Wilson, C.; Merchant, M.; Settleman, J. The Cancer Stem Cell Marker Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Is Required to Maintain a Drug-Tolerant Tumor Cell Subpopulation. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 3579–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Li, H.; Chen, X.; Luo, X. Dual roles and therapeutic potential of ALDH3 family members in cancer. Chem. Interactions 2025, 418, 111622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavudi, K.; Nuguri, S.M.; Pandey, P.; Kokkanti, R.R.; Wang, Q.-E. ALDH and cancer stem cells: Pathways, challenges, and future directions in targeted therapy. Life Sci. 2024, 356, 123033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ginestier, C.; Hur, M.H.; Charafe-Jauffret, E.; Monville, F.; Dutcher, J.; Brown, M.; Jacquemier, J.; Viens, P.; Kleer, C.G.; Liu, S.; et al. ALDH1 Is a Marker of Normal and Malignant Human Mammary Stem Cells and a Predictor of Poor Clinical Outcome. Cell Stem Cell 2007, 1, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinavahi, S.S.; Bazewicz, C.G.; Gowda, R.; Robertson, G.P. Aldehyde Dehydrogenase Inhibitors for Cancer Therapeutics. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 40, 774–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, W.; Cruickshank, B.M.; Arun, R.P.; MacLean, M.R.; Cahill, H.F.; Morales-Quintanilla, F.; Dean, C.A.; Wasson, M.-C.D.; Dahn, M.L.; Coyle, K.M.; et al. ALDH1A3 is the switch that determines the balance of ALDH+ and CD24−CD44+ cancer stem cells, EMT-MET, and glucose metabolism in breast cancer. Oncogene 2024, 43, 3151–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurowski, K.; Föll, M.; Werner, T.; Schilling, O.; Werner, M.; Fichtner-Feigl, S.; Bengsch, B.; Bronsert, P.; Holzner, P.A.; Timme, S. Impact of ALDH1A1 Expression in Intrahepatic Cholangiocellular Carcinoma. J. Cancer 2025, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.-Q.; He, J.-R.; Wang, H.-Y. Decreased expression of ALDH1L1 is associated with a poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2011, 29, 1843–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Han, Y.; Yu, L.; Luo, B.; Hu, Z.; Li, X.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X.; Huang, W.; Wang, H.; et al. Decreased expression of ALDH5A1 predicts prognosis in patients with ovarian cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2017, 18, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, M.; Lu, L.; Zander, D.S.; Sreerama, L.; Coco, D.; Moreb, J.S. ALDH1A1 and ALDH3A1 expression in lung cancers: Correlation with histologic type and potential precursors. Lung Cancer 2008, 59, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Cui, Y.; Zhu, Y. Comprehensive analysis reveals signal and molecular mechanism of mitochondrial energy metabolism pathway in pancreatic cancer. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 1117145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buscail, L.; Bournet, B.; Cordelier, P. Role of oncogenic KRAS in the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Visser, K.E.; Joyce, J.A. The evolving tumor microenvironment: From cancer initiation to metastatic outgrowth. Cancer Cell 2023, 41, 374–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melssen, M.M.; Sheybani, N.D.; Leick, K.M.; Slingluff, C.L. Barriers to immune cell infiltration in tumors. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e006401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raskov, H.; Orhan, A.; Christensen, J.P.; Gögenur, I. Cytotoxic CD8+ T cells in cancer and cancer immunotherapy. Br. J. Cancer 2021, 124, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doser, R.L.; Knight, K.M.; Deihl, E.W.; Hoerndli, F.J. Activity-dependent mitochondrial ROS signaling regulates recruitment of glutamate receptors to synapses. eLife 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poturnajova, M.; Kozovska, Z.; Matuskova, M. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 and 1A3 isoforms – mechanism of activation and regulation in cancer. Cell. Signal. 2021, 87, 110120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Croker, A.K.; Allan, A.L. Inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) activity reduces chemotherapy and radiation resistance of stem-like ALDHhiCD44+ human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 133, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciccone, V.; Simonis, V.; Del Gaudio, C.; Cucini, C.; Ziche, M.; Morbidelli, L.; Donnini, S. ALDH1A1 confers resistance to RAF/MEK inhibitors in melanoma cells by maintaining stemness phenotype and activating PI3K/AKT signaling. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2024, 224, 116252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Januchowski, R.; Wojtowicz, K.; Sterzyſska, K.; Sosiſska, P.; Andrzejewska, M.; Zawierucha, P.; Nowicki, M.; Zabel, M. Inhibition of ALDH1A1 activity decreases expression of drug transporters and reduces chemotherapy resistance in ovarian cancer cell lines. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 78, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Chai, S.; Wang, P.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wang, K. Aldehyde dehydrogenases and cancer stem cells. Cancer Lett. 2015, 369, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muralikrishnan, V.; Hurley, T.D.; Nephew, K.P. Targeting Aldehyde Dehydrogenases to Eliminate Cancer Stem Cells in Gynecologic Malignancies. Cancers 2020, 12, 961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.-P.; Tsai, M.-F.; Chang, T.-H.; Tang, W.-C.; Chen, S.-Y.; Lai, H.-H.; Lin, T.-Y.; Yang, J.C.-H.; Yang, P.-C.; Shih, J.-Y.; et al. ALDH-positive lung cancer stem cells confer resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Cancer Lett. 2013, 328, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Qin, C.; Yang, X.; Zhao, B.; Li, T.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, W. Phthalocyanine and photodynamic therapy relieve albumin paclitaxel and gemcitabine chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Exp. Cell Res. 2025, 446, 114455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).