Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

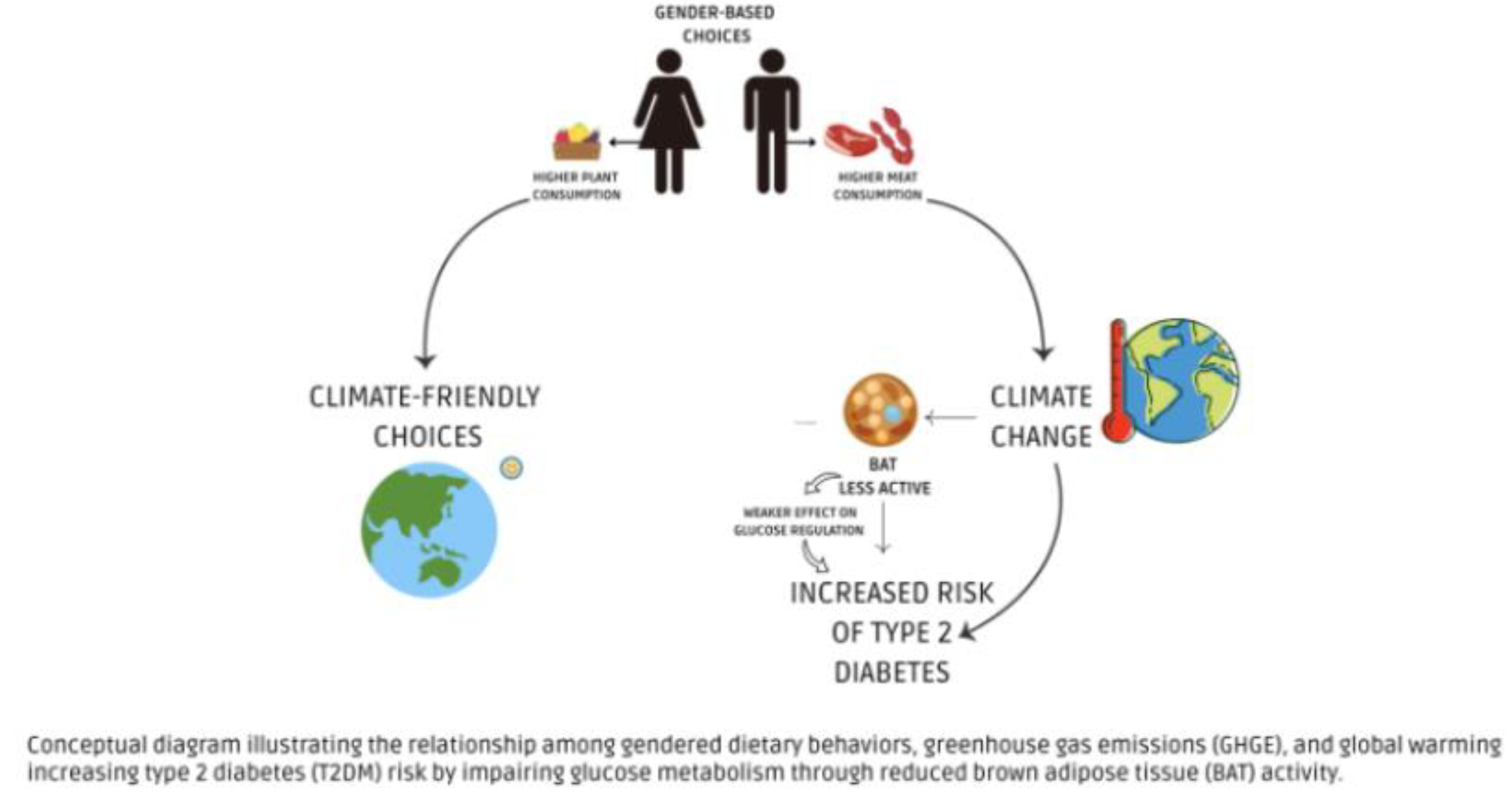

2. Climate Change and Its Impact on Diabetes

3. Gender Differences in Dietary Choices and Their Impact on Climate Change

4. Conclusions and Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Poore, J.; Nemecek, T. Reducing Food’s Environmental Impacts through Producers and Consumers. Science (80-. ). 2018, 360, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley, J. A.; Ramankutty, N.; Brauman, K. A.; Cassidy, E. S.; Gerber, J. S.; Johnston, M.; Mueller, N. D.; O’Connell, C.; Ray, D. K.; West, P. C.; Balzer, C.; Bennett, E. M.; Carpenter, S. R.; Hill, J.; Monfreda, C.; Polasky, S.; Rockström, J.; Sheehan, J.; Siebert, S.; Tilman, D.; Zaks, D. P. M. Solutions for a Cultivated Planet. Nature 2011, 478, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symonds, M. E.; Farhat, G.; Aldiss, P.; Pope, M.; Budge, H. Brown Adipose Tissue and Glucose Homeostasis–the Link between Climate Change and the Global Rise in Obesity and Diabetes. Adipocyte 2019, 8, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Marken Lichtenbelt, W. D.; Vanhommerig, J. W.; Smulders, N. M.; Drossaerts, J. M. A. F. L.; Kemerink, G. J.; Bouvy, N. D.; Schrauwen, P.; Teule, G. J. J. Cold-Activated Brown Adipose Tissue in Healthy Men. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009, 360, 1500–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, P.; Zhang, L.; Qiu, Y.; Ren, J.; Sun, X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, L.; Cheng, S.; Liu, S.; Zhuang, H.; Lu, D.; Zhang, S.; Liang, H.; Chen, S. Heat Stress Reduces Brown Adipose Tissue Activity by Exacerbating Mitochondrial Damage in Type 2 Diabetic Mice. J. Therm. Biol. 2024, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Dong, W.; Yuan, B.; Yang, Y.; Yang, D.; Lin, X.; Chen, C.; Zhang, W. Vitamin E Confers Cytoprotective Effects on Cardiomyocytes under Conditions of Heat Stress by Increasing the Expression of Metallothionein. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2016, 37, 1429–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, P.; Zhang, Z. H.; Huang, X. F.; Shi, Y. C.; Khandekar, N.; Yang, H. Q.; Liang, S. Y.; Song, Z. Y.; Lin, S. Cold Exposure Promotes Obesity and Impairs Glucose Homeostasis in Mice Subjected to a High-fat Diet. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 18, 3923–3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoneshiro, T.; Kataoka, N.; Walejko, J. M.; Ikeda, K.; Brown, Z.; Yoneshiro, M.; Crown, S. B.; Osawa, T.; Sakai, J.; McGarrah, R. W.; White, P. J.; Nakamura, K.; Kajimura, S. Metabolic Flexibility via Mitochondrial BCAA Carrier SLC25A44 Is Required for Optimal Fever. Elife 2021, 10, e66865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willett, W.; Rockström, J.; Loken, B.; Springmann, M.; Lang, T.; Vermeulen, S.; Garnett, T.; Tilman, D.; DeClerck, F.; Wood, A.; Jonell, M.; Clark, M.; Gordon, L. J.; Fanzo, J.; Hawkes, C.; Zurayk, R.; Rivera, J. A.; De Vries, W.; Majele Sibanda, L.; Afshin, A.; Chaudhary, A.; Herrero, M.; Agustina, R.; Branca, F.; Lartey, A.; Fan, S.; Crona, B.; Fox, E.; Bignet, V.; Troell, M.; Lindahl, T.; Singh, S.; Cornell, S. E.; Srinath Reddy, K.; Narain, S.; Nishtar, S.; Murray, C. J. L. Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission on Healthy Diets from Sustainable Food Systems. Lancet 2019, 393, 447–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Springmann, M.; Godfray, H. C. J.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. Analysis and Valuation of the Health and Climate Change Cobenefits of Dietary Change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113, 4146–4151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, R. R.; Anderson, K. R.; Fry, J. L. Sex-Specific Variation in Metabolic Responses to Diet. Nutr. 2024, Vol. 16, Page 2921 2024, 16, 2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feraco, A.; Armani, A.; Amoah, I.; Guseva, E.; Camajani, E.; Gorini, S.; Strollo, R.; Padua, E.; Caprio, M.; Lombardo, M. Assessing Gender Differences in Food Preferences and Physical Activity: A Population-Based Survey. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varì, R.; Silenzi, A.; d’Amore, A.; Catena, A.; Masella, R.; Scazzocchio, B. MaestraNatura Reveals Its Effectiveness in Acquiring Nutritional Knowledge and Skills: Bridging the Gap between Girls and Boys from Primary School. Nutr. 2023, Vol. 15, Page 1357 2023, 15, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varì, R.; D’amore, A.; Silenzi, A.; Chiarotti, F.; Del Papa, S.; Giovannini, C.; Scazzocchio, B.; Masella, R. Improving Nutrition Knowledge and Skills by the Innovative Education Program MaestraNatura in Middle School Students of Italy. Nutr. 2022, Vol. 14, Page 2037 2022, 14, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satija, A.; Bhupathiraju, S. N.; Rimm, E. B.; Spiegelman, D.; Chiuve, S. E.; Borgi, L.; Willett, W. C.; Manson, J. A. E.; Sun, Q.; Hu, F. B. Plant-Based Dietary Patterns and Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes in US Men and Women: Results from Three Prospective Cohort Studies. PLoS Med. 2016, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mauvais-Jarvis, F.; Bairey Merz, N.; Barnes, P. J.; Brinton, R. D.; Carrero, J. J.; DeMeo, D. L.; De Vries, G. J.; Epperson, C. N.; Govindan, R.; Klein, S. L.; Lonardo, A.; Maki, P. M.; McCullough, L. D.; Regitz-Zagrosek, V.; Regensteiner, J. G.; Rubin, J. B.; Sandberg, K.; Suzuki, A. Sex and Gender: Modifiers of Health, Disease, and Medicine. Lancet 2020, 396, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plows, J. F.; Stanley, J. L.; Baker, P. N.; Reynolds, C. M.; Vickers, M. H. The Pathophysiology of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springmann, M.; Wiebe, K.; Mason-D’Croz, D.; Sulser, T. B.; Rayner, M.; Scarborough, P. Health and Nutritional Aspects of Sustainable Diet Strategies and Their Association with Environmental Impacts: A Global Modelling Analysis with Country-Level Detail. Lancet Planet. Heal. 2018, 2, e451–e461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meo, S. A.; Meo, A. S. Climate Change and Diabetes Mellitus - Emerging Global Public Health Crisis: Observational Analysis. Pakistan J. Med. Sci. 2024, 40, 559–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDF Diabetes Atlas. Global Diabetes Data & Statistics. Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Schlienger, J. L. Complications Du Diabète de Type 2. Press. Medicale 2013, 42, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Ley, S. H.; Hu, F. B. Global Aetiology and Epidemiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Its Complications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bommer, C.; Heesemann, E.; Sagalova, V.; Manne-Goehler, J.; Atun, R.; Bärnighausen, T.; Vollmer, S. The Global Economic Burden of Diabetes in Adults Aged 20–79 Years: A Cost-of-Illness Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasaki, H.; Yagyu, H.; Shimano, H. A Comprehensive Analysis of Diabetic Complications and Advances in Management Strategies. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2025, 32, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdés, S.; Doulatram-Gamgaram, V.; Lago, A.; Torres, F. G.; Badía-Guillén, R.; Olveira, G.; Goday, A.; Calle-Pascual, A.; Castaño, L.; Castell, C.; Delgado, E.; Menendez, E.; Franch-Nadal, J.; Gaztambide, S.; Girbés, J.; Gomis, R.; Ortega, E.; Galán-García, J. L.; Aguilera-Venegas, G.; Soriguer, F.; Rojo-Martínez, G. Ambient Temperature and Prevalence of Diabetes and Insulin Resistance in the Spanish Population: Di@bet.Es Study. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 180, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Managing Diabetes in the Heat. CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/articles/managing-diabetes-in-the-heat.html (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Blauw, L. L.; Aziz, N. A.; Tannemaat, M. R.; Blauw, C. A.; de Craen, A. J.; Pijl, H.; Rensen, P. C. N. Diabetes Incidence and Glucose Intolerance Prevalence Increase with Higher Outdoor Temperature. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2017, 5, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Vega, M.; Gutiérrez-Repiso, C.; Muñoz-Garach, A.; Lima-Rubio, F.; Morcillo, S.; Tinahones, F. J.; Picón-César, M. J. Relationship between Environmental Temperature and the Diagnosis and Treatment of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: An Observational Retrospective Study. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penn Leonard Davis Institute (Penn LDI). People with Type 2 Diabetes and Extreme Temperatures. Penn LDI. Available online: https://ldi.upenn.edu/our-work/research-updates/extreme-heat-and-cold-put-people-with-type-2-diabetes-at-risk-for-dangerous-health-conditions/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Kenny, G. P.; Yardley, J.; Brown, C.; Sigal, R. J.; Jay, O. Heat Stress in Older Individuals and Patients with Common Chronic Diseases. C. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2010, 182, 1053–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Xiao, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, H.; Huang, K. Insulin Desensitization and Cell Senescence Induced by Heat Stress in Pig Testicular Cell Model. Anim. Biotechnol. 2023, 34, 4947–4956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Song, Y.; Xie, H.; Dong, M. An Update on Brown Adipose Tissue and Obesity Intervention: Function, Regulation and Therapeutic Implications. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2023, 13, 1065263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, D. G. Mitochondrial Proton Leaks and Uncoupling Proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenerg. 2021, 1862, 148428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanssen, M. J. W.; Hoeks, J.; Brans, B.; Van Der Lans, A. A. J. J.; Schaart, G.; Van Den Driessche, J. J.; Jörgensen, J. A.; Boekschoten, M. V.; Hesselink, M. K. C.; Havekes, B.; Kersten, S.; Mottaghy, F. M.; Van Marken Lichtenbelt, W. D.; Schrauwen, P. Short-Term Cold Acclimation Improves Insulin Sensitivity in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Nat. Med. 2015, 21, 863–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, B. T.; Morton, N. M.; Stimson, R. H. Substrate Utilization by Brown Adipose Tissue: What’s Hot and What’s Not? Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne). 2020, 11, 571659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkel, M.; Schmid, S. M.; Iwen, K. A. Physiology and Clinical Importance of White, Beige and Brown Adipose Tissue. Internist 2019, 60, 151–159. [Google Scholar]

- Schilperoort, M.; Hoeke, G.; Kooijman, S.; Rensen, P. C. N. Relevance of Lipid Metabolism for Brown Fat Visualization and Quantification. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 2016, 27, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, M.; Okamatsu-Ogura, Y.; Matsushita, M.; Watanabe, K.; Yoneshiro, T.; Nio-Kobayashi, J.; Iwanaga, T.; Miyagawa, M.; Kameya, T.; Nakada, K.; Kawai, Y.; Tsujisaki, M. High Incidence of Metabolically Active Brown Adipose Tissue in Healthy Adult Humans: Effects of Cold Exposure and Adiposity. Diabetes 2009, 58, 1526–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, X.; Shao, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y. Characterization of Brown Adipose Tissue 18F-FDG Uptake in PET/CT Imaging and Its Influencing Factors in the Chinese Population. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2016, 43, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au-Yong, I. T. H.; Thorn, N.; Ganatra, R.; Perkins, A. C.; Symonds, M. E. Brown Adipose Tissue and Seasonal Variation in Humans. Diabetes 2009, 58, 2583–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.; Bova, R.; Schofield, L.; Bryant, W.; Dieckmann, W.; Slattery, A.; Govendir, M. A.; Emmett, L.; Greenfield, J. R. Brown Adipose Tissue Exhibits a Glucose-Responsive Thermogenic Biorhythm in Humans. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopkins, T.; Ragsdale, C.; Seo, J. Elevated Ambient Temperature Reduces Fat Storage through the FoxO-Mediated Insulin Signaling Pathway. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0317971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, Z. S.; McCurdy, C. E. Short-Term Thermoneutral Housing Alters Glucose Metabolism and Markers of Adipose Tissue Browning in Response to a High-Fat Diet in Lean Mice. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2018, 315, R627–R637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Märker, T.; Sell, H.; Zilleßen, P.; Glöde, A.; Kriebel, J.; Margriet Ouwens, D.; Pattyn, P.; Ruige, J.; Famulla, S.; Roden, M.; Eckel, J.; Habich, C. Heat Shock Protein 60 as a Mediator of Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Insulin Resistance. Diabetes 2012, 61, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Q.; Benmarhnia, T.; Jalaludin, B.; Shen, X.; Yu, Z.; Ren, M.; Liang, Q.; Wang, J.; Ma, W.; Huang, C. Assessing the Effects of Non-Optimal Temperature on Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in a Cohort of Pregnant Women in Guangzhou, China. Environ. Int. 2021, 152, 106457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, G. L.; Luo, J.; Park, A. L.; Feig, D. S.; Moineddin, R.; Ray, J. G. Influence of Environmental Temperature on Risk of Gestational Diabetes. CMAJ 2017, 189, E682–E689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teyton, A.; Sun, Y.; Molitor, J.; Chen, J. C.; Sacks, D.; Avila, C.; Chiu, V.; Slezak, J.; Getahun, D.; Wu, J.; Benmarhnia, T. Examining the Relationship between Extreme Temperature, Microclimate Indicators, and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in Pregnant Women Living in Southern California. Environ. Epidemiol. 2023, 7, E252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, N.; Xu, R.; Wei, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Guo, C.; Zhu, X.; Peng, J.; Qian, Y. Influence of Temperature on the Risk of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Hypertension in Different Pregnancy Trimesters. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retnakaran, R.; Ye, C.; Kramer, C. K.; Hanley, A. J.; Connelly, P. W.; Sermer, M.; Zinman, B. Impact of Daily Incremental Change in Environmental Temperature on Beta Cell Function and the Risk of Gestational Diabetes in Pregnant Women. Diabetologia 2018, 61, 2633–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vallianou, N. G.; Geladari, E. V.; Kounatidis, D.; Geladari, C. V.; Stratigou, T.; Dourakis, S. P.; Andreadis, E. A.; Dalamaga, M. Diabetes Mellitus in the Era of Climate Change. Diabetes Metab. 2021, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Persichetti, A.; Sciuto, R.; Rea, S.; Basciani, S.; Lubrano, C.; Mariani, S.; Ulisse, S.; Nofroni, I.; Maini, C. L.; Gnessi, L. Prevalence, Mass, and Glucose-Uptake Activity of 18F-FDG-Detected Brown Adipose Tissue in Humans Living in a Temperate Zone of Italy. PLoS One 2013, 8, e63391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellet, V.; Routhier-Labadie, A.; Bellemare, W.; Lakhal-Chaieb, L.; Turcotte, E.; Carpentier, A. C.; Richard, D. Outdoor Temperature, Age, Sex, Body Mass Index, and Diabetic Status Determine the Prevalence, Mass, and Glucose-Uptake Activity of 18F-FDG-Detected BAT in Humans. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 96, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, M.; Solazzo, E.; Guizzardi, D.; Monforti-Ferrario, F.; Tubiello, F. N.; Leip, A. Food Systems Are Responsible for a Third of Global Anthropogenic GHG Emissions. Nat. Food 2021 23 2021, 2, 198–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, P.; Steinfeld, H.; Henderson, B.; Mottet, A.; Opio, C.; Dijkman, J.; Falcucci, A.; Tempio, G. Tackling Climate Change through Livestock—A Global Assessment of Emissions and Mitigation Opportunities; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Auclair, O.; Eustachio Colombo, P.; Milner, J.; Burgos, S. A. Partial Substitutions of Animal with Plant Protein Foods in Canadian Diets Have Synergies and Trade-Offs among Nutrition, Health and Climate Outcomes. Nat. Food 2024, 5, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Boer, J.; de Witt, A.; Aiking, H. Help the Climate, Change Your Diet: A Cross-Sectional Study on How to Involve Consumers in a Transition to a Low-Carbon Society. Appetite 2016, 98, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehfest, E.; Bouwman, L.; Van Vuuren, D. P.; Den Elzen, M. G. J.; Eickhout, B.; Kabat, P. Climate Benefits of Changing Diet. Clim. Change 2009, 95, (1–2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapp, A. L.; Wyma, N.; Alessandrini, R.; Ndinda, C.; Perez-Cueto, A.; Risius, A. Recommendations to Address the Shortfalls of the EAT–Lancet Planetary Health Diet from a Plant-Forward Perspective. Lancet Planet. Heal. 2025, 9, e23–e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, M. C.; Willits-Smith, A.; Meyer, R.; Keoleian, G. A.; Rose, D. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Energy Use Associated with Production of Individual Self-Selected US Diets. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 04404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenfeld, D. L.; Tomiyama, A. J. Gender Differences in Meat Consumption and Openness to Vegetarianism. Appetite 2021, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkala, E. A. E.; Hugg, T. T.; Jaakkola, J. J. K. Awareness of Climate Change and the Dietary Choices of Young Adults in Finland: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS One 2014, 9, e97846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruby, M. B.; Heine, S. J. Meat, Morals, and Masculinity. Appetite 2011, 56, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castronuovo, L.; Guarnieri, L.; Tiscornia, M. V.; Allemandi, L. Food Marketing and Gender among Children and Adolescents: A Scoping Review. Nutr. J. 2021, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amson, A.; Bagnato, M.; Remedios, L.; Pritchard, M.; Sabir, S.; Gillis, G.; Pauzé, E.; White, C.; Vanderlee, L.; Hammond, D.; Kent, M. P. Beyond the Screen: Exploring the Dynamics of Social Media Influencers, Digital Food Marketing, and Gendered Influences on Adolescent Diets. PLOS Digit. Heal. 2025, 4, e0000729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopwood, C. J.; Zizer, J. N.; Nissen, A. T.; Dillard, C.; Thompkins, A. M.; Graça, J.; Waldhorn, D. R.; Bleidorn, W. Paradoxical Gender Effects in Meat Consumption across Cultures. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culliford, A.; Bradbury, J. A Cross-Sectional Survey of the Readiness of Consumers to Adopt an Environmentally Sustainable Diet. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downs, S. M.; Merchant, E. V.; Sackey, J.; Fox, E. L.; Davis, C.; Fanzo, J. Sustainability Considerations Are Not Influencing Meat Consumption in the US. Appetite 2024, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willits-Smith, A.; Aranda, R.; Heller, M. C.; Rose, D. Addressing the Carbon Footprint, Healthfulness, and Costs of Self-Selected Diets in the USA: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Lancet Planet. Heal. 2020, 4, e98–e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirwan, L. B.; Walton, J.; Flynn, A.; Nugent, A. P.; McNulty, B. A. Preliminary Environmental Analyses of Irish Adult Food Consumption Data to Facilitate a Transition to Sustainable Diets. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2022, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallström E, Bajzelj B, Håkansson N, Sjörs J, Åkesson A, Wolk A, Sonesson U. Dietary climate impact: contribution of foods and dietary patterns by gender and age in a Swedish population. J Clean Prod. 2021, 306, 127189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, J. M. G.; Falkenberg, T.; Nöthlings, U.; Heinzel, C.; Borgemeister, C.; Escobar, N. Changing Dietary Patterns Is Necessary to Improve the Sustainability of Western Diets from a One Health Perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjellberg, M.; Skoglund, W.; Haller, H. Decreasing the Carbon Footprint of Food through Public Procurement—A Case Study from the Municipality of Härnösand. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1156784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allenden, N.; Hine, D. W.; Craig, B. M.; Cowie, A. L.; McGreevy, P. D.; Lykins, A. D. What Should We Eat? Realistic Solutions for Reducing Our Food Footprint. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 32, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).