Submitted:

31 October 2025

Posted:

04 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Mortality, Air Quality and Human Bioclimate Data

2.3. GAM modeling Framework

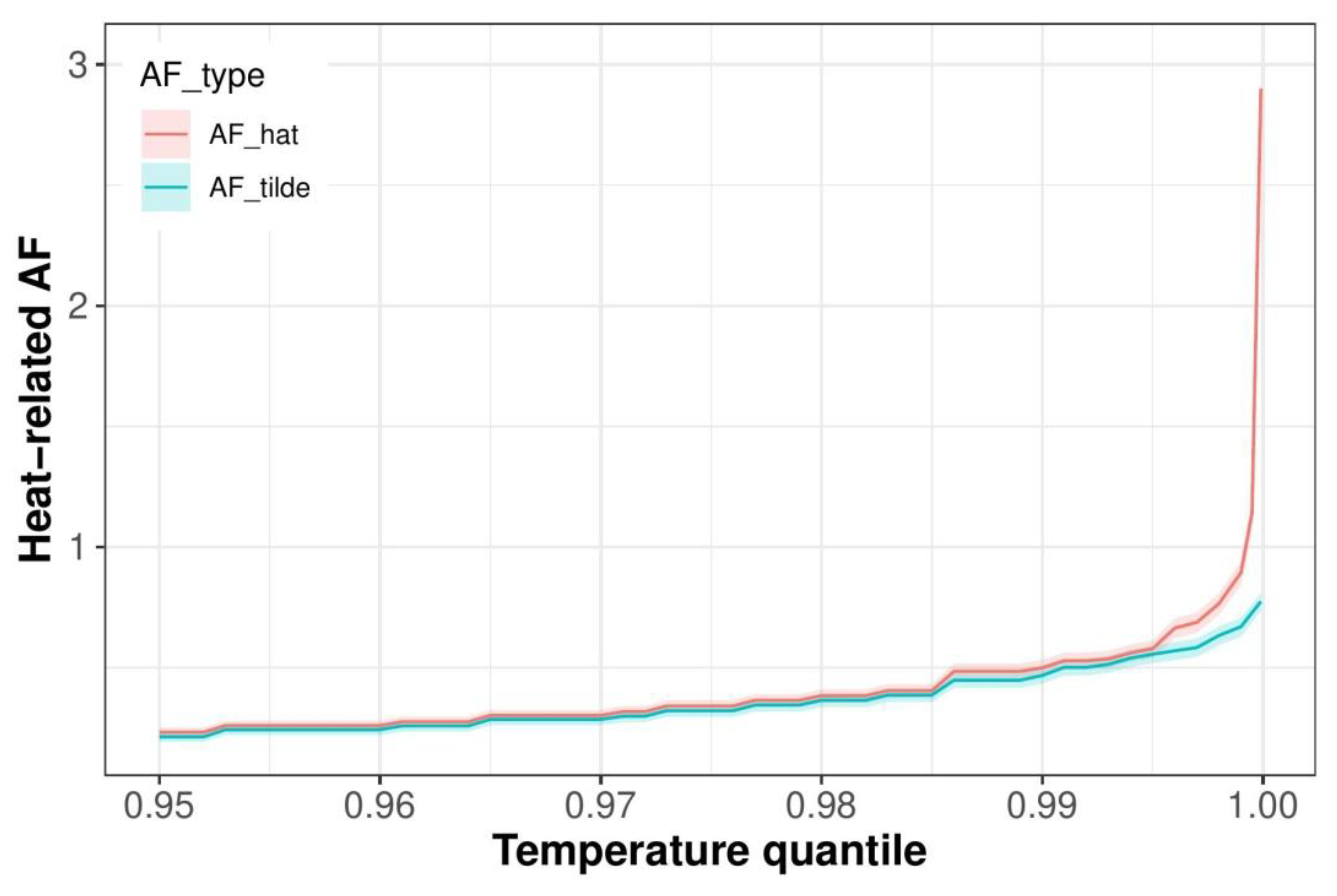

2.4. Attributable Fraction

3. Results

3.1. Observations on Population Dynamics, Mortality Trends, and Statistical Confidence

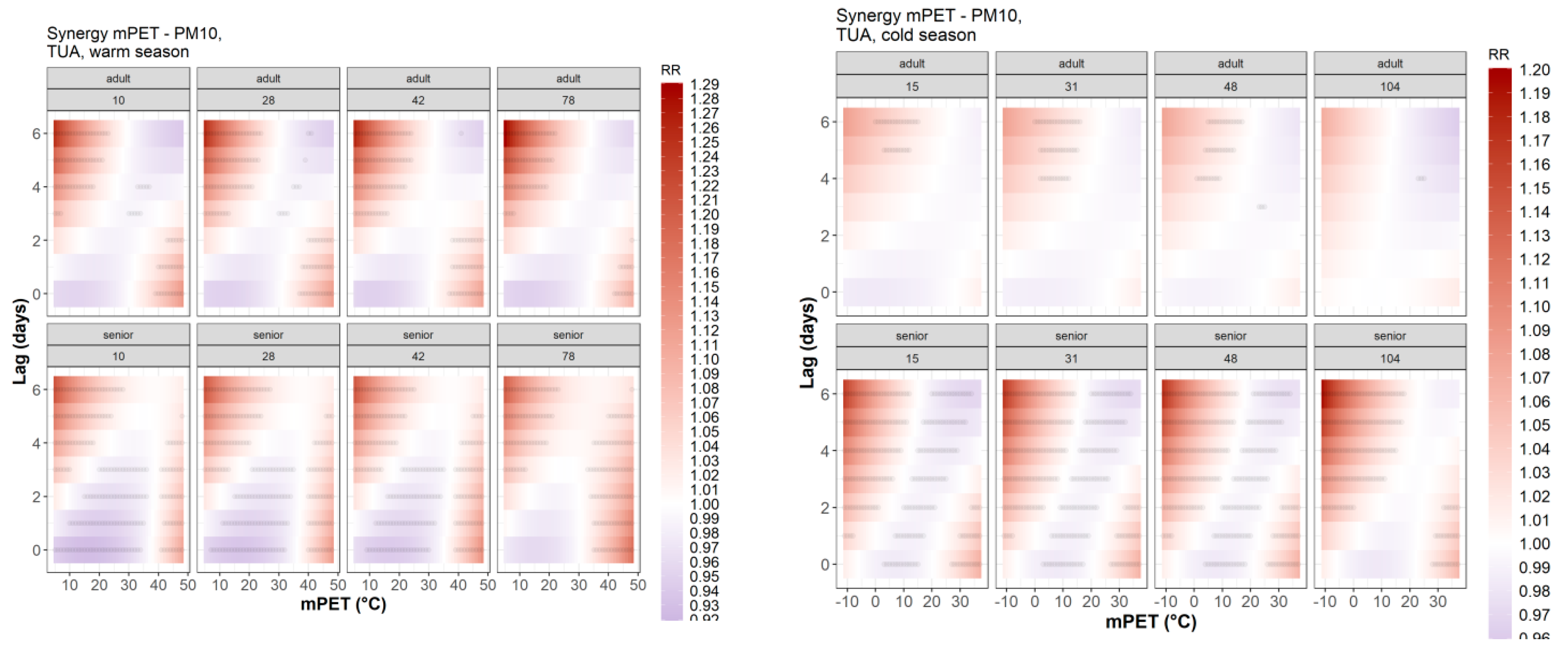

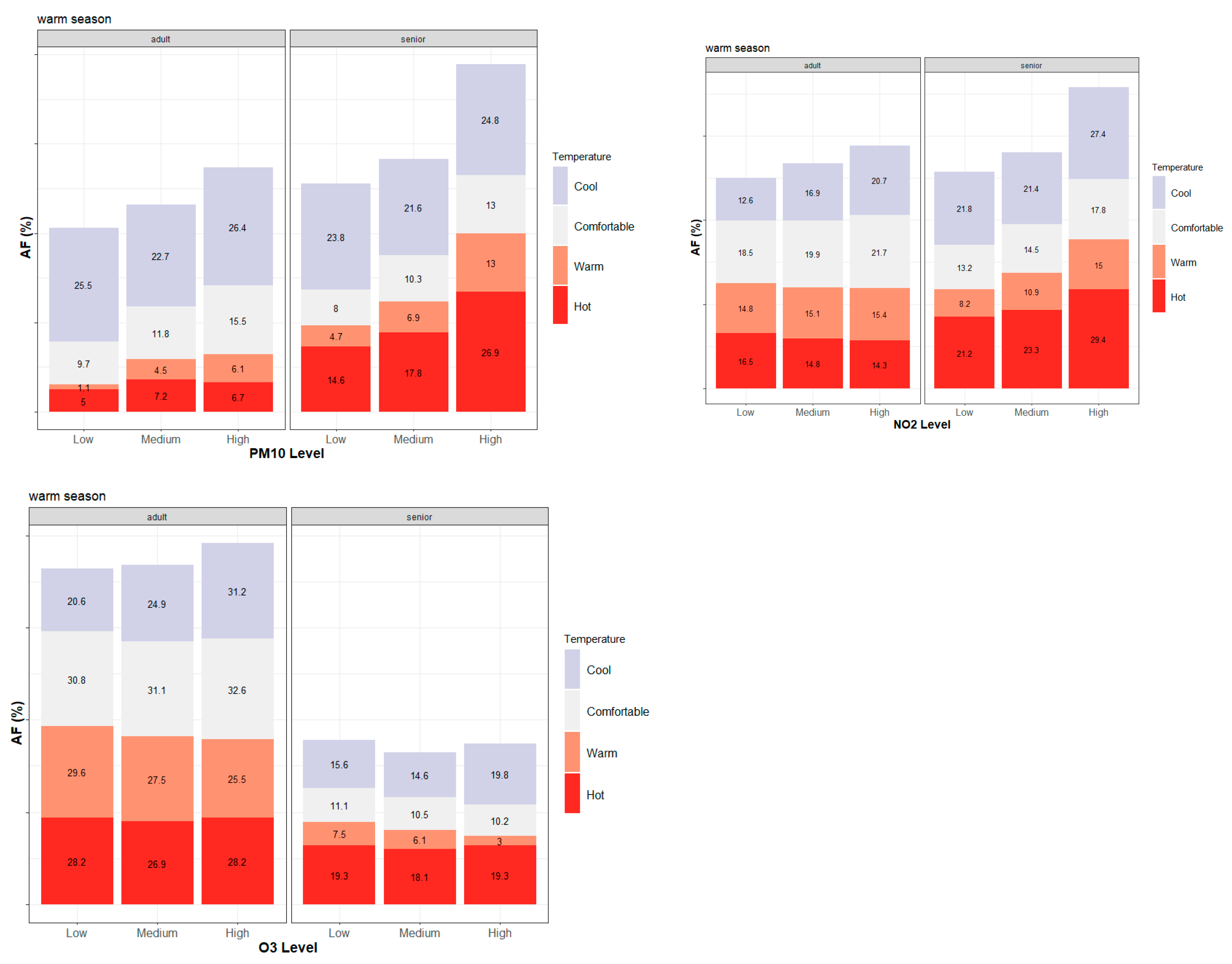

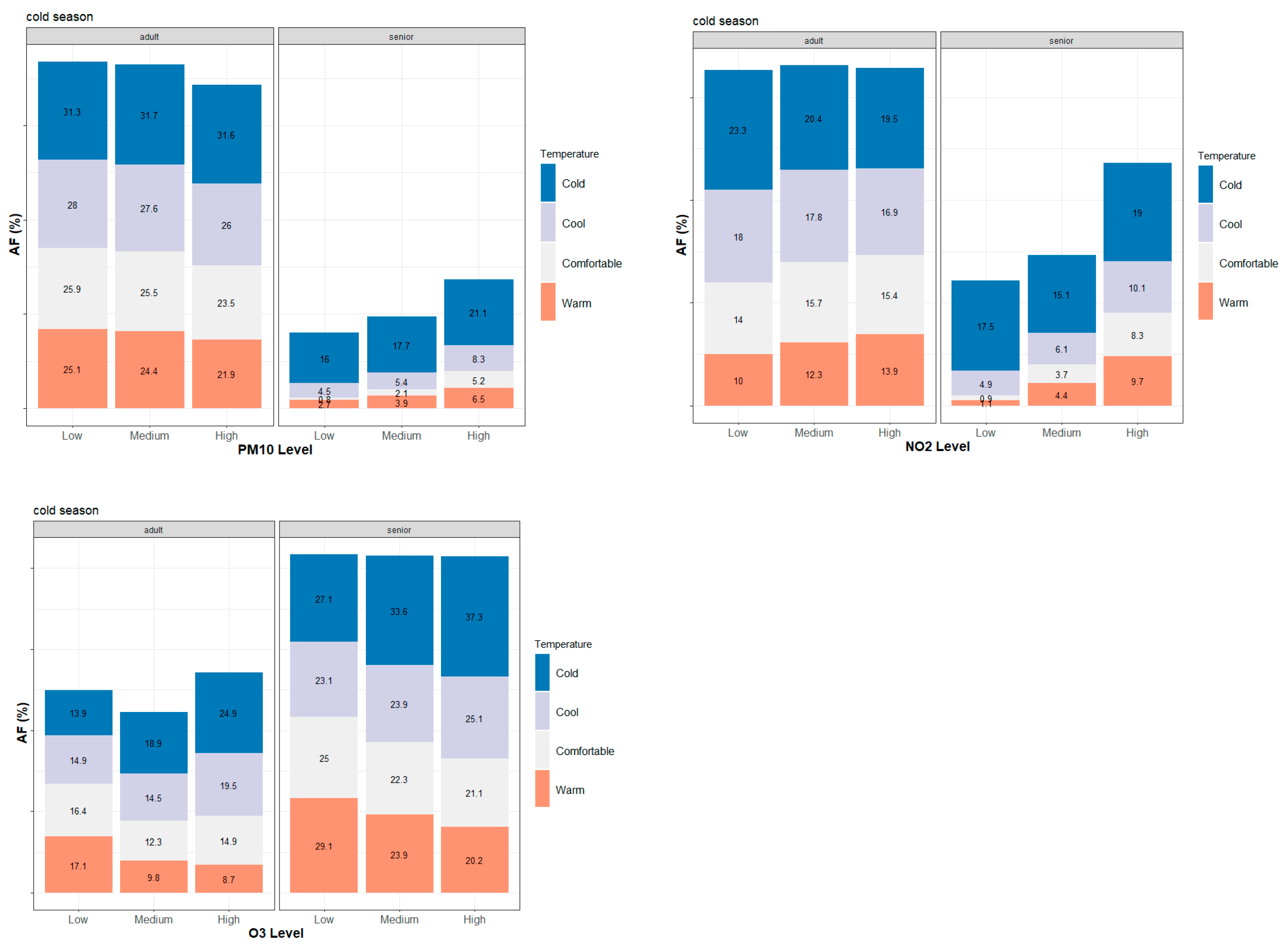

3.2. Seasonal and Age-Specific Patterns of Attributable Mortality Fractions

3.3. Intra-Urban Differences in Attributable Mortality

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AF | Attributable Fraction |

| DLNM | Distributed Lag Non-Linear Models |

| GAM | Generalized Additive Model |

| mPET | modified Physiologically Equivalent Temperature |

| TUA | Thessaloniki Urban Area |

Appendix A

References

- G. Lazoglou et al., “Identification of climate change hotspots in the Mediterranean,” Sci. Rep., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1–11, 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Kekkou, T. Economou, G. Lazoglou, and C. Anagnostopoulou, “Temperature Extremes and Human Health in Cyprus: Investigating the Impact of Heat and Cold Waves,” 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Zittis et al., “Climate Change and Weather Extremes in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East,” Rev. Geophys., vol. 60, no. 3, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Founda, K. V. Varotsos, F. Pierros, and C. Giannakopoulos, “Observed and projected shifts in hot extremes’ season in the Eastern Mediterranean,” Glob. Planet. Change, vol. 175, no. February, pp. 190–200, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Keppas et al., “Future climate change impact on urban heat island in two mediterranean cities based on high-resolution regional climate simulations,” Atmosphere (Basel)., vol. 12, no. 7, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Keppas et al., “Urban Heat Island and Future Projections: A Study in Thessaloniki, Greece,” in International conference on Environmental protection and disaster RISKs, ENVIRORISK 2020, 2021, pp. 201–212. [CrossRef]

- C. Giannaros, E. Galanaki, and I. Agathangelidis, “Climatology and Long-Term Trends in Population Exposure to Urban Heat Stress Considering Variable Demographic and Thermo–Physiological Attributes,” Climate, vol. 12, no. 12, pp. 1–17, 2024. [CrossRef]

- European Environmental Agency, “Air quality status report 2025,” 2025. https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/analysis/publications/air-quality-status-report-2025 (accessed Apr. 25, 2025).

- D. Akritidis, A. K. Georgoulias, B. Steffens, A. Pozzer, and P. Zanis, “The future health burden of air pollution in Greece and the associated drivers,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 994, no. March, p. 179897, 2025. [CrossRef]

- D. Parliari et al., “Short-Term Effects of Apparent Temperature on Cause-Specific Mortality in the Urban Area of Thessaloniki, Greece,” Atmosphere, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Parliari, C. Giannaros, S. Papadogiannaki, and D. Melas, “Short-Term Effects of Air Pollution on Mortality in the Urban Area of Thessaloniki, Greece,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 6, p. 548, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Elisa Gallo et al., “Heat-related mortality in Europe during 2023 and the role of adaptation in protecting health,” Nat. Med., 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Loupa, Z. P. Kryona, V. Pantelidou, and S. Rapsomanikis, “Are PM2.5 in the Atmosphere of a Small City a Threat for Health?,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 20, p. 11329, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Khomenko et al., “Premature mortality due to air pollution in European cities: a health impact assessment,” Lancet Planet. Heal., vol. 5, no. 3, pp. e121–e134, 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. Hu et al., “Does air pollution modify temperature-related mortality? A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Environ. Res., vol. 210, no. November 2021, p. 112898, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Rai et al., “Heat-related cardiorespiratory mortality: effect modification by air pollution across 482 cities from 24 countries,” Environ. Int., vol. 174, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Matzarakis, “A note on the assessment of the effect of atmospheric factors and components on humans,” Atmosphere (Basel)., vol. 11, no. 12, pp. 1–18, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Matzarakis, “Curiosities about thermal indices estimation and application,” Atmosphere (Basel)., vol. 12, no. 6, pp. 1–7, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. C. Chen, W. N. Chen, C. C. K. Chou, and A. Matzarakis, “Concepts and new implements for modified physiologically equivalent temperature,” Atmosphere (Basel)., vol. 11, no. 7, pp. 1–17, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. C. Chen and A. Matzarakis, “Modified physiologically equivalent temperature—basics and applications for western European climate,” Theor. Appl. Climatol., vol. 132, no. 3–4, pp. 1275–1289, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Giannaros et al., “A thermo-physiologically consistent approach for studying the heat-health nexus with hierarchical generalized additive modelling : Application in Athens urban area ( Greece ),” Urban Clim., vol. 58, p. 102206, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Parliari et al., “Comprehensive Approach for Assessing the Synergistic Impact of Air Quality and Thermal Conditions on Human Mortality: Case of Thessaloniki, Greece,” 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Economou et al., “Flexible distributed lag models for count data using mgcv,” Am. Stat., no. 856612, pp. 1–28, 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Gasparrini and M. Leone, “Attributable risk from distributed lag models,” BMC Med. Res. Methodol., vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 1–8, 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. Kalogeropoulos, D. Fragkopoulos, P. Andreopoulos, and A. Tragaki, “Shifting Sands: Examining and Mapping the Population Structure of Greece Through the Last Three Censuses,” Economies, vol. 12, no. 11, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Papadimitriou et al., “Successful aging and lifestyle comparison of Greeks living in Greece and abroad: the epidemiological Mediterranean Islands Study (MEDIS),” Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr., vol. 97, no. June, p. 104523, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Psistaki, P. Kouis, A. Michanikou, P. K. Yiallouros, S. I. Papatheodorou, and A. Κ. Paschalidou, “Temporal trends in temperature-related mortality and evidence for maladaptation to heat and cold in the Eastern Mediterranean region,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 943, no. March, p. 173899, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Progiou, N. Liora, I. Sebos, C. Chatzimichail, and D. Melas, “Measures and Policies for Reducing PM Exceedances through the Use of Air Quality Modeling : The Case of Thessaloniki, Greece,” Sustainability, no. 15, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Zyrichidou et al., “Adverse results of the economic crisis: A study on the emergence of enhanced formaldehyde (HCHO) levels seen from satellites over Greek urban sites,” Atmos. Res., vol. 224, no. March, pp. 42–51, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Rizos, C. Meleti, G. Kouvarakis, N. Mihalopoulos, and D. Melas, “Determination of the background pollution in the Eastern Mediterranean applying a statistical clustering technique,” Atmos. Environ., vol. 276, no. March, p. 119067, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Giannaros et al., “Hourly values of an advanced human-biometeorological index for diverse populations from 1991 to 2020 in Greece,” Sci. Data, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 1–10, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Matzarakis, F. Rutz, and H. Mayer, “Modelling radiation fluxes in simple and complex environments: Basics of the RayMan model,” Int. J. Biometeorol., vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 131–139, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Matzarakis, F. Rutz, and H. Mayer, “Modelling radiation fluxes in simple and complex environments - Application of the RayMan model,” Int. J. Biometeorol., vol. 51, no. 4, pp. 323–334, 2007. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Wood, “Fast stable restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models,” J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol., vol. 73, no. 1, pp. 3–36, 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. . Wood, Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R, 2nd Editio. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Parliari et al., “A comprehensive approach for assessing synergistic impact of air quality and thermal conditions on mortality: The case of Thessaloniki, Greece,” Urban Clim., vol. 56, no. July, p. 102088, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Economou and F. Garry, “Probabilistic simulation of big climate data for robust quantification of changes in compound hazard events,” Weather Clim. Extrem., vol. 38, no. November, p. 100522, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Honda et al., “Heat-related mortality risk model for climate change impact projection,” Env. Heal. Prev Med, no. 19, pp. 56–63, 2014. [CrossRef]

- A. Aglan et al., “Personal and community-level exposure to air pollution and daily changes in respiratory symptoms and oxygen saturation among adults with COPD,” Hyg. Environ. Heal. Adv., vol. 6, no. March, p. 100052, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chen et al., “Breathing in danger: Understanding the multifaceted impact of air pollution on health impacts,” Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf., vol. 280, no. April, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chang, A. X. Tan, K. C. Nadeau, and M. C. Odden, “Aging Hearts in a Hotter, More Turbulent World: The Impacts of Climate Change on the Cardiovascular Health of Older Adults,” Curr. Cardiol. Rep., vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 749–760, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. D. Meade et al., “Physiological factors characterizing heat-vulnerable older adults: A narrative review,” Environ. Int., vol. 144, no. June, p. 105909, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Fastl, A. Arnberger, V. Gallistl, V. K. Stein, and T. E. Dorner, “Heat vulnerability: health impacts of heat on older people in urban and rural areas in Europe,” Wien. Klin. Wochenschr., vol. 136, no. 17–18, pp. 507–514, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Spalt et al., “Time-Location Patterns of a Diverse Population of Older Adults: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis and Air Pollution (MESA Air),” J Expo Sci Env. Epidemiol., vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 349–355, 2016. [CrossRef]

- N. E. Klepeis et al., “The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): A resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants,” J. Expo. Anal. Environ. Epidemiol., vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 231–252, 2001. [CrossRef]

- T. Benoussaïd, I. Coll, H. Charreire, I. Makni, M. Costes, and A. Elessa Etuman, “Reassessing air pollution exposure: How daily mobility and activities shape individual risk in greater Paris,” Comput. Environ. Urban Syst., vol. 122, no. March, 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Anenberg, S. Haines, E. Wang, N. Nassikas, and P. L. Kinney, “Synergistic health effects of air pollution, temperature, and pollen exposure: a systematic review of epidemiological evidence,” Environ. Heal. A Glob. Access Sci. Source, vol. 19, no. 1, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. M. Rahman et al., “The Effects of Coexposure to Extremes of Heat and Particulate Air Pollution on Mortality in California Implications for Climate Change,” Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med., vol. 206, no. 9, pp. 1117–1127, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Stafoggia et al., “Joint effect of heat and air pollution on mortality in 620 cities of 36 countries,” Environ. Int., vol. 181, no. June, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang et al., “Effect modification of air pollution on the association between heat and mortality in five European countries,” Environ. Res., vol. 263, no. P1, p. 120023, 2024. [CrossRef]

- E. S. Coker, S. E. Cleland, D. McVea, M. Stafoggia, and S. B. Henderson, “The synergistic effects of PM2.5 and high temperature on community mortality in British Columbia,” npj Clean Air, vol. 1, no. 1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- P. Clark, M. H. Harris, J. S. Apte, and J. D. Marshall, “National and Intraurban Air Pollution Exposure Disparity Estimates in the United States: Impact of Data-Aggregation Spatial Scale,” Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett., vol. 9, no. 9, pp. 786–791, 2022. [CrossRef]

- van den Brekel et al., “Ethnic and socioeconomic inequalities in air pollution exposure: a cross-sectional analysis of nationwide individual-level data from the Netherlands,” Lancet Planet. Heal., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. e18–e29, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Rentschler and N. Leonova, “Air pollution kills – Evidence from a global analysis of exposure and poverty,” 2022. https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/developmenttalk/air-pollution-kills-evidence-global-analysis-exposure-and-poverty?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed Oct. 31, 2025).

- A. Tobias, C. F. S. Ng, Y. Kim, M. Hashizume, and L. Madaniyazi, “Compilation of open access time-series datasets for studying temperature-mortality association,” Data Br., vol. 55, p. 110694, 2024. [CrossRef]

| Thermal sensation | Warm period mPET thresholds | Cold period mPET thresholds |

|---|---|---|

| “Cold” | - | < 8 °C |

| “Cool” | < 18 °C | 8 °C - 18 °C |

| “Comfortable” | 18 °C - 23 °C | 18 °C - 23 °C |

| “Warm” | 23 °C - 35 °C | > 23 °C |

| “Hot” | > 35 °C | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).