Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Model Formulation

2.1. Model Equations

3. Results and Discussion

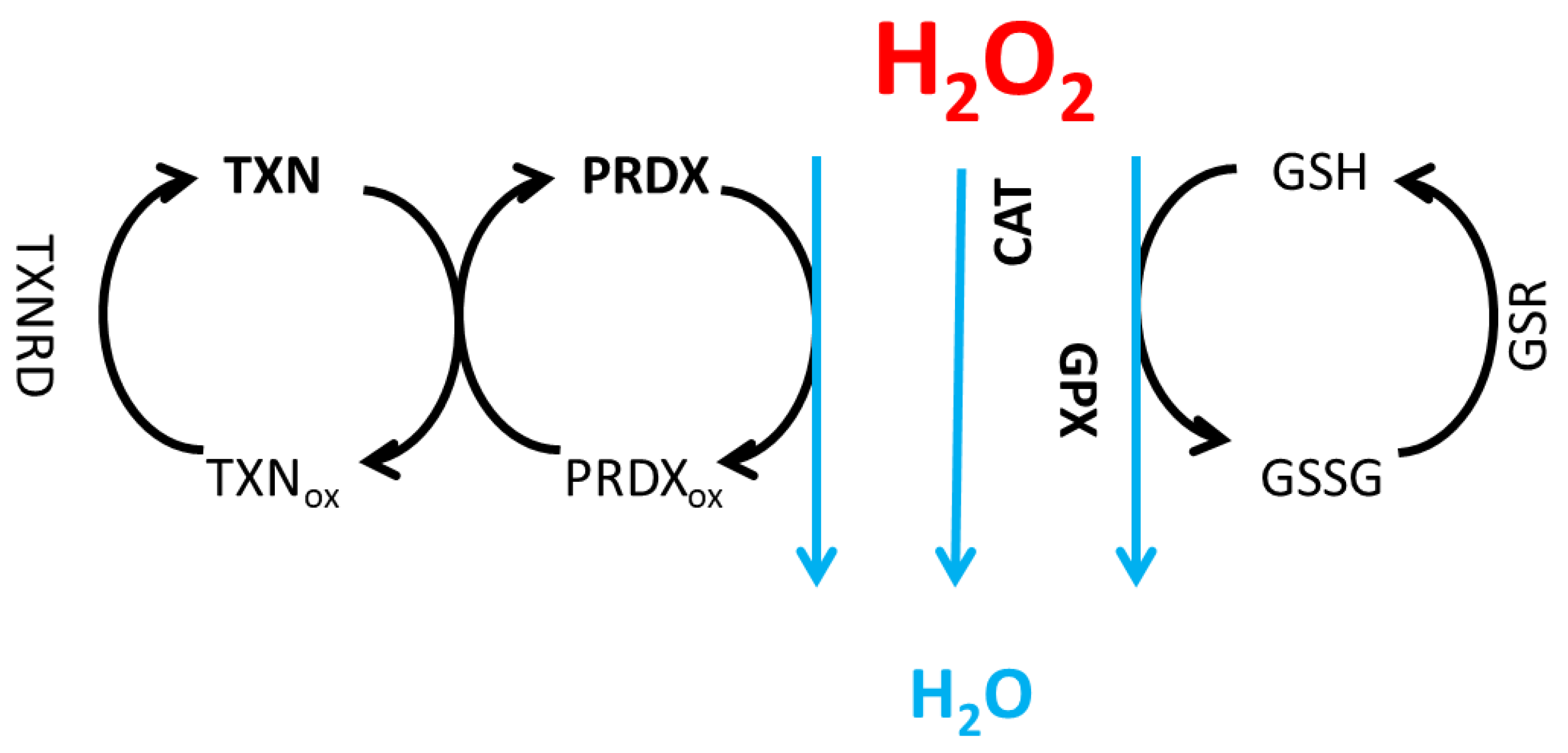

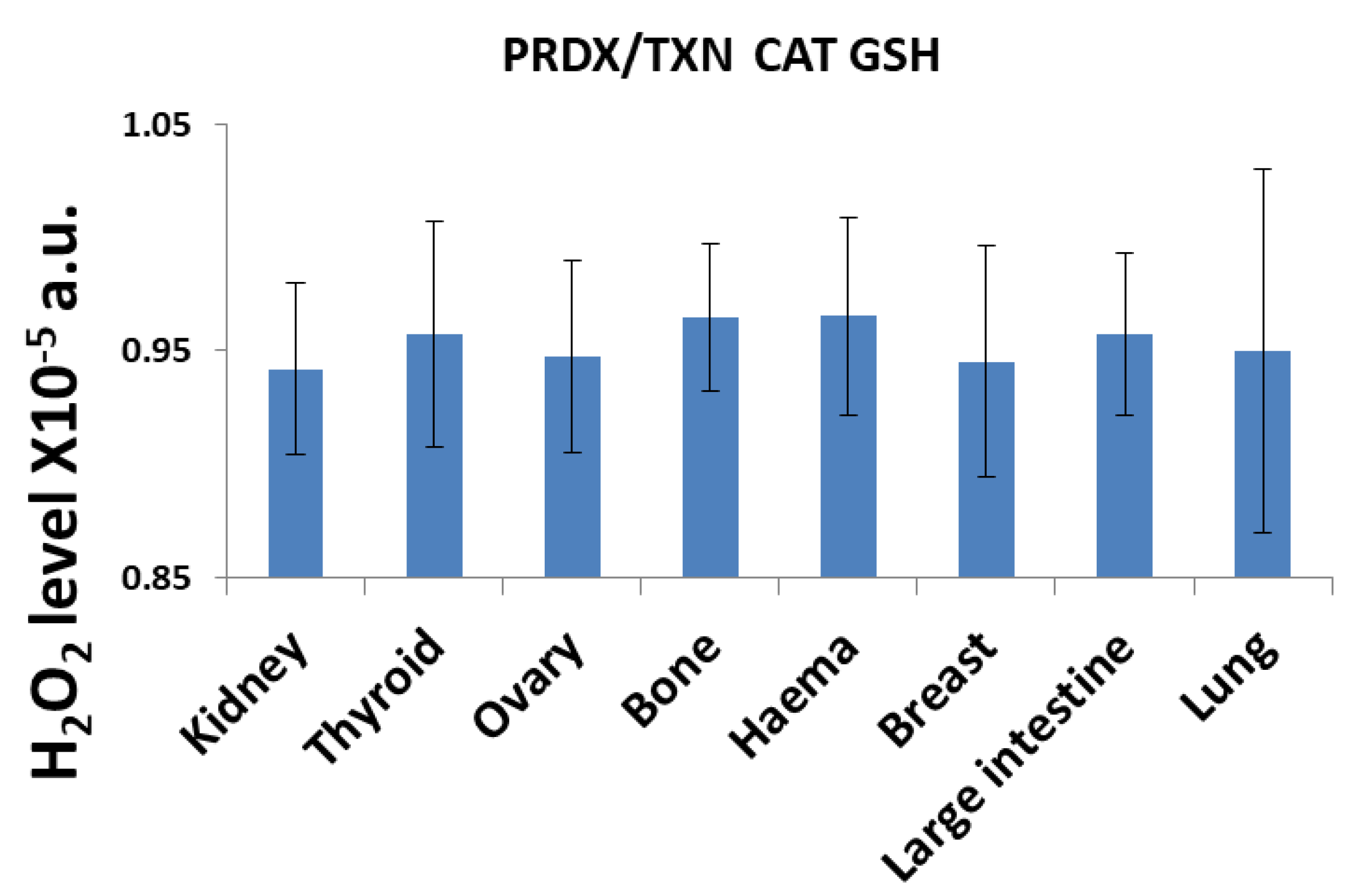

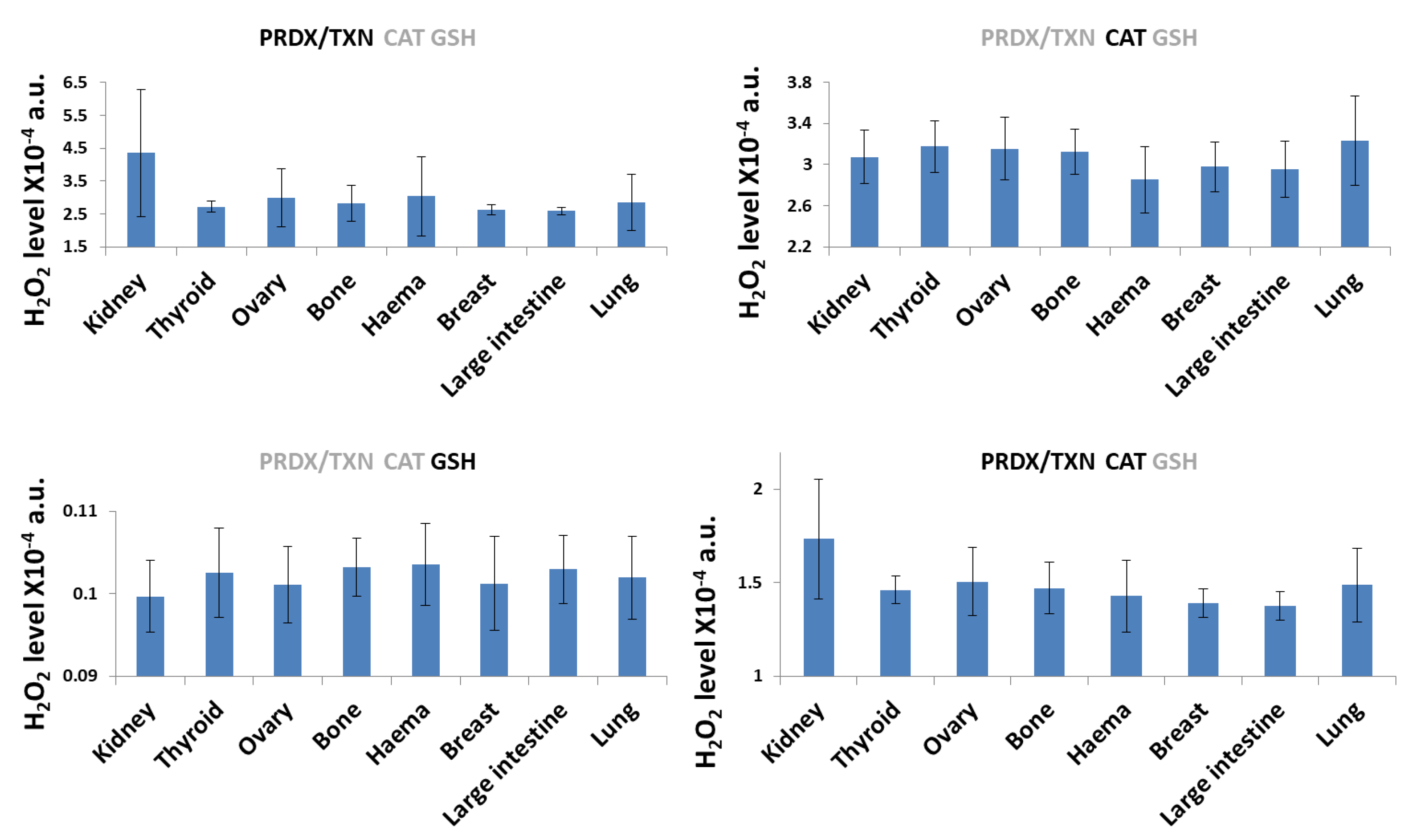

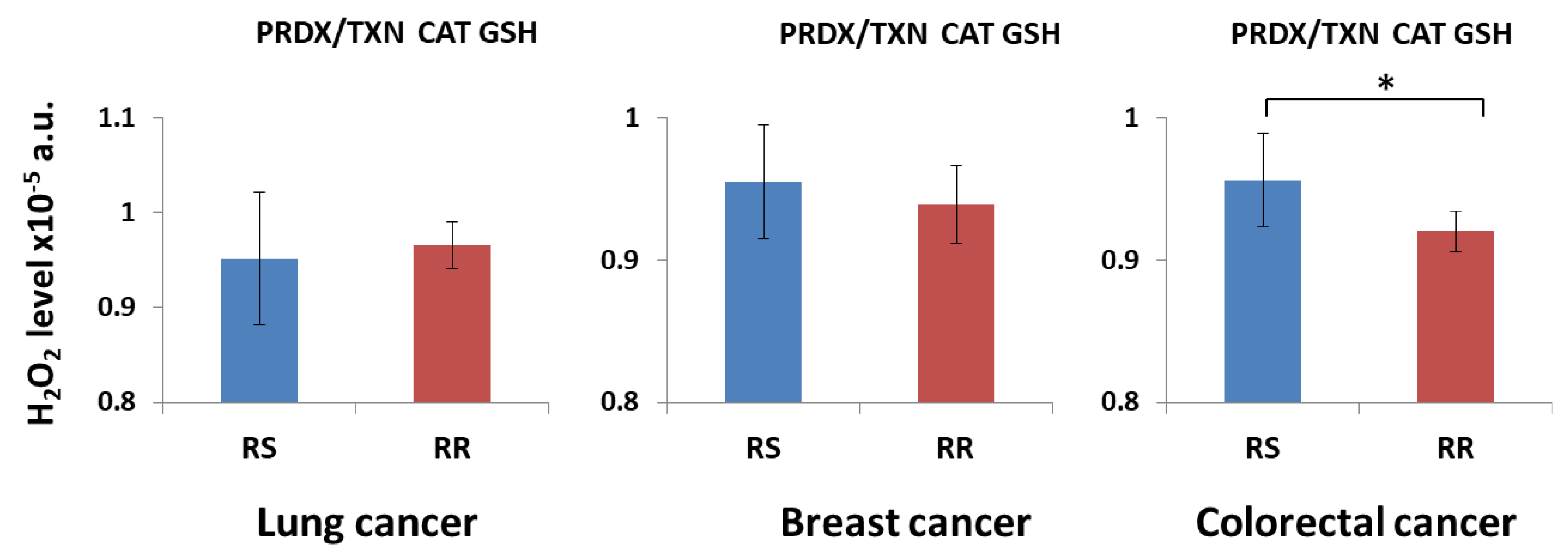

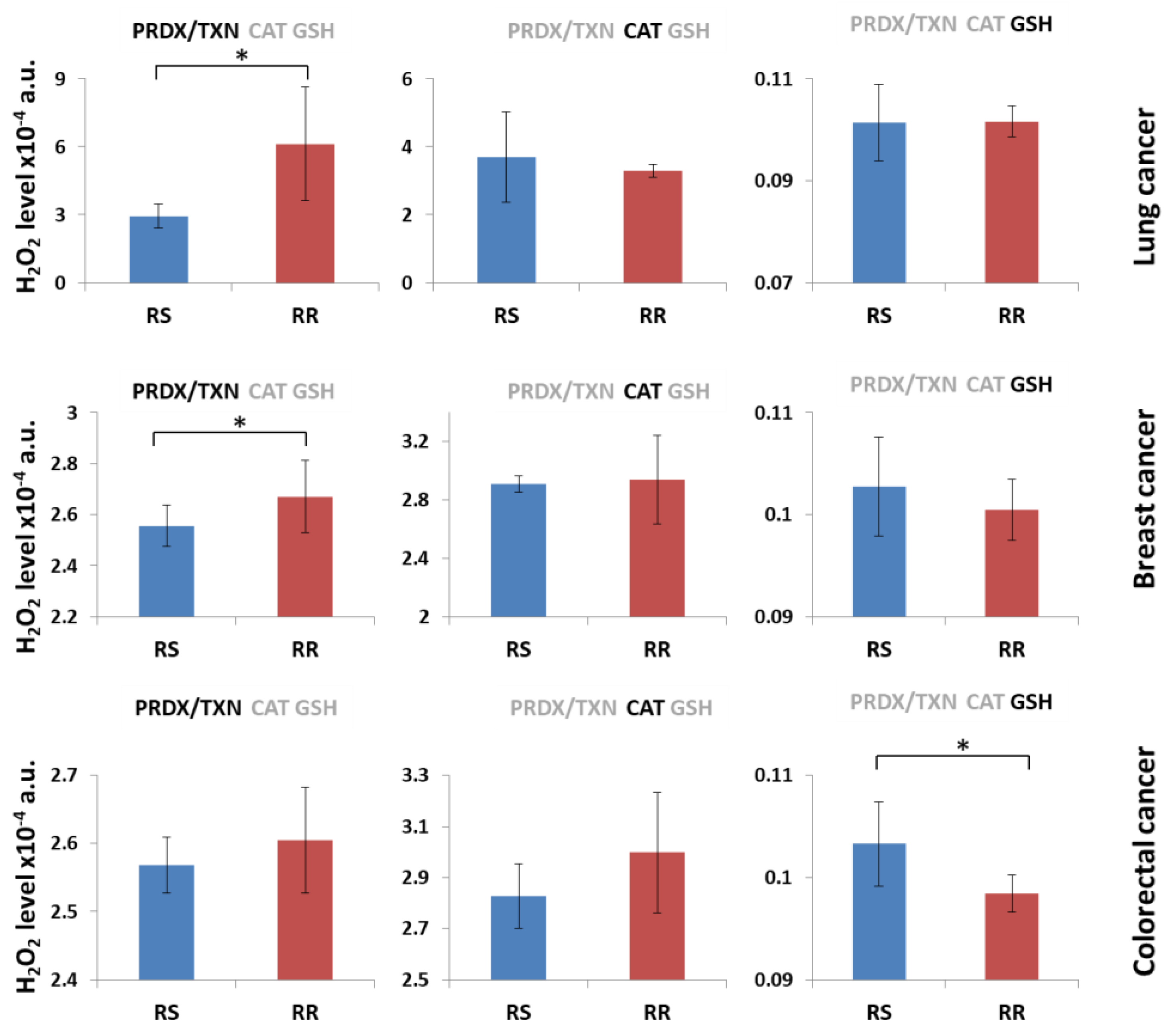

3.1. H2O2 Neutralization Pathways and Their Connection to Radioresistance

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sarsour, E.H.; Kumar, M.G.; Chaudhuri, L.; Kalen, A.L.; Goswami, P.C. Redox control of the cell cycle in health and disease. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling, 2009, 11, 2985–3011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xing, D.; Gao, X. Low-power laser irradiation activates Src tyrosine kinase through reactive oxygen species-mediated signaling pathway. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 2008, 217, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinendegen, L.; Pollycove, M.; Sondhaus, C.A. Responses to Low Doses of Ionizing Radiation in Biological Systems. Nonlinearity in Biology, Toxicology, Medicine, 2004, 2, 154014204905074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trachootham, D.; Lu, W.; Ogasawara, M.A.; Valle, N.R.D.; Huang, P. Redox regulation of cell survival. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling, 2008, 10, 1343–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thannickal, V.J.; Fanburg, B.L. Reactive oxygen species in cell signaling. American Journal of Physiology - Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology, 2000, 279, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bienert, G.P.; Schjoerring, J.K.; Jahn, T.P. Membrane transport of hydrogen peroxide. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes, 2006, 1758, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, J.R.; Yang, S.; Peroxide, H.; Signaling, R. ; vol.; no.; pp. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, F.; Cadenas, E. Cellular titration of apoptosis with steady state concentrations of H2O2: submicromolar levels of H2O2 induce apoptosis through fenton chemistry independent of the cellular thiol state. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2001, 30, 1008–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülden, M.; Jess, A.; Kammann, J.; Maser, E.; Seibert, H. Cytotoxic potency of H2O2 in cell cultures: impact of cell concentration and exposure time. Free Radic Biol Med, 2010, 49, 1298–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdon, R. Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide in relation to mammalian cell proliferation. Free radical biology & medicine, 1995, 18, 775–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Koo, N.; Min, D.B.; Species, R.O. ; Aging; Nutraceuticals. A., Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 2004, 3, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, S.; et al. Hypoxia stabilizes the H2O2-producing oxidase Nox4 in cardiomyocytes via suppressing autophagy-related lysosomal degradation. Genes to Cells, 2024, 29, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radi, R.; Cassina, A.; Hodara, R.; Quijano, C.; Castro, L. Peroxynitrite reactions and formation in mitochondria. Free radical biology & medicine, 2002, 33, 1451–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henle, E.; Linn, S. ; Formation; prevention, and repair of DNA damage by iron/hydrogen peroxide. The Journal of biological chemistry, 1997, 272, 19095–19098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Florence, T.M. The production of hydroxyl radical from hydrogen peroxide. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry, 1984, 22, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puppo, A.; Halliwellt, B. Formation of hydroxyl radicals from hydrogen peroxide in the presence of iron Is haemoglobin a biological Fenton reagent? Biochem. J, 1988, 249, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, A.; Yan, L.-J.; Jana, C.K.; Das, N. Role of Catalase in Oxidative Stress- and Age-Associated Degenerative Diseases. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, A. Glutathione metabolism and its selective modification. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1988, 263, 17205–17208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelly, C.L. Regulation of glutathione synthesis. Molecular Aspects of Medicine, 2009, 30, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamiec, M.; Skonieczna, M. UV radiation in HCT 116 cells influences intracellular H2O2 and glutathione levels, antioxidant expression, and protein glutathionylation. Acta Biochimica Polonica, 2019, 66, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immenschuh, S.; Baumgart-Vogt, E. ; Peroxiredoxins; oxidative stress; cell proliferation. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling, 2005, 7, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poynton, R.A.; Hampton, M.B. Peroxiredoxins as biomarkers of oxidative stress. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - General Subjects, 2014, 1840, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sue, G.R.; Ho, Z.C.; Kim, K. Peroxiredoxins: A historical overview and speculative preview of novel mechanisms and emerging concepts in cell signaling. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2005, 38, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, O.H.; Degnan, S.M. Antioxidant enzymes that target hydrogen peroxide are conserved across the animal kingdom, from sponges to mammals. Scientific Reports, 2023, 13, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glorieux, C.; Calderon, P.B. ; Catalase, a remarkable enzyme: Targeting the oldest antioxidant enzyme to find a new cancer treatment approach. Biological Chemistry, 2017, 398, 1095–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Cederbaum, A.I. Mitochondrial catalase and oxidative injury. NeuroSignals, 2001, 10, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margis, R.; Dunand, C.; Teixeira, F.K.; Margis-Pinheiro, M. Glutathione peroxidase family – an evolutionary overview. The FEBS Journal, 2008, 275, 3959–3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powis, G.; Montfort, W.R. Properties and biological activities of thioredoxins. Annual review of biophysics and biomolecular structure, 2001, 30, 421–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnér, E.S.J.; Holmgren, A. Physiological functions of thioredoxin and thioredoxin reductase. European Journal of Biochemistry, 2000, 267, 6102–6109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, D.; Coimbra, S.; Rocha, S.; Santos-Silva, A. ; Inhibition of erythrocyte’s catalase, glutathione peroxidase or peroxiredoxin 2 – Impact on cytosol and membrane. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 2023, 739, 109569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitozo, P.A.; et al. A study of the relative importance of the peroxiredoxin-, catalase-, and glutathione-dependent systems in neural peroxide metabolism. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2011, 51, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciesielska, S.; Bil, P.; Gajda, K.; Poterala-Hejmo, A.; Hudy, D.; Rzeszowska-Wolny, J. Cell type-specific differences in redox regulation and proliferation after low UVA doses. PLOS ONE, 2019, 14, e0205215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bil, P.; Ciesielska, S.; Jaksik, R.; Rzeszowska-Wolny, J. Circuits Regulating Superoxide and Nitric Oxide Production and Neutralization in Different Cell Types: Expression of Participating Genes and Changes Induced by Ionizing Radiation. Antioxidants, 2020, 9, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aon, M.A.; et al. Glutathione/thioredoxin systems modulate mitochondrial H2O2 emission: An experimental-computational study. The Journal of General Physiology, 2012, 139, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortassa, S.; Aon, M.A.; Winslow, R.L.; O’Rourke, B. A Mitochondrial Oscillator Dependent on Reactive Oxygen Species. Biophysical Journal, 2004, 87, 2060–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kembro, J.M.; Aon, M.A.; Winslow, R.L.; O’Rourke, B.; Cortassa, S.; Energetics, I.M. , Redox and ROS Metabolic Networks: A Two-Compartment Model. Biophysical Journal, 2013, 104, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, C.F.; Schafer, F.Q.; Buettner, G.R.; Rodgers, V.G.J. The rate of cellular hydrogen peroxide removal shows dependency on GSH: Mathematical insight into in vivo H2O2 and GPx concentrations. Free Radical Research, 2007, 41, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghandi, M.; et al. Next-generation characterization of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Nature, 2019, 569, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambarsari, L.; Lindawati, E. ; Isolation, Fractionation and Characterization of Catalase from Neurospora crassa (InaCC F226)’. [CrossRef]

- Makino, N.; Mochizuki, Y.; Bannai, S.; Sugita, Y. Kinetic Studies on the Removal of Extracellular Hydrogen Peroxide by Cultured Fibroblasts. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1994, 269, 1020–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpenko, I.L.; Valuev-Elliston, V.T.; Ivanova, O.N.; Smirnova, O.A.; Ivanov, A.V. Peroxiredoxins-The Underrated Actors during Virus-Induced Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland), 2021, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manta, B.; Hugo, M.; Ortiz, C.; Ferrer-Sueta, G.; Trujillo, M.; Denicola, A. The peroxidase and peroxynitrite reductase activity of human erythrocyte peroxiredoxin 2. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 2009, 484, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.J.; Kim, N.; Seong, K.M.; Youn, H.; Youn, B. Investigation of Radiation-induced Transcriptome Profile of Radioresistant Non-small Cell Lung Cancer A549 Cells Using RNA-seq. PLOS ONE, 2013, 8, e59319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amornwichet, N.; et al. The EGFR mutation status affects the relative biological effectiveness of carbon-ion beams in non-small cell lung carcinoma cells. Sci Rep, 2015, 5, 11305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.K.; Bell, M.H.; Nirodi, C.S.; Story, M.D.; Minna, J.D. Radiogenomics- predicting tumor responses to radiotherapy in lung cancer. Semin Radiat Oncol, 2010, 20, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagounis, I.V.; et al. Repression of the autophagic response sensitises lung cancer cells to radiation and chemotherapy. Br J Cancer, 2016, 115, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schilling, D.; Bayer, C.; Li, W.; Molls, M.; Vaupel, P.; Multhoff, G. Radiosensitization of Normoxic and Hypoxic H1339 Lung Tumor Cells by Heat Shock Protein 90 Inhibition Is Independent of Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1α. PLoS One, 2012, 7, e31110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Kim, W.; Kwon, T.; Youn, H.; Kim, J.S.; Youn, B. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 enhances radioresistance and aggressiveness of non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncotarget, 2016, 7, 23961–23974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberal, F.D.C.G.; McMahon, S.J. Characterization of Intrinsic Radiation Sensitivity in a Diverse Panel of Normal, Cancerous and CRISPR-Modified Cell Lines. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023, 24, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdeking, M.; et al. Efficiency of moderately hypofractionated radiotherapy in NSCLC cell model. Front Oncol, 2024, 14, 1293745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, J.; et al. Radiation sensitivity of human lung cancer cell lines. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol, 1989, 25, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.S.; et al. Radiotherapy diagnostic biomarkers in radioresistant human H460 lung cancer stem-like cells. Cancer Biol Ther, 2016, 17, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.S.; Casciati, A.; Bakar, Z.A.; Hamzah, H.; Ahmad, T.A.T.; Noor, M.H.M. The Detection of DNA Damage Response in MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 Breast Cancer Cell Lines after X-ray Exposure. Genome Integrity, 2023, 14, 20220001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristol, M.L.; et al. Dual functions of autophagy in the response of breast tumor cells to radiation. Autophagy, 2012, 8, 739–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruss, C.; et al. Neoadjuvant radiotherapy in ER+, HER2+, and triple-negative -specific breast cancer based humanized tumor mice enhances anti-PD-L1 treatment efficacy. Front Immunol, 2024, 15, 1355130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.-S.; et al. Overcoming radioresistance of breast cancer cells with MAP4K4 inhibitors. Sci Rep, 2024, 14, 7410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M.; et al. Development and characterisation of acquired radioresistant breast cancer cell lines. Radiation Oncology, 2019, 14, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafontaine, J.; Boisvert, J.-S.; Glory, A.; Coulombe, S.; Wong, P. Synergy between Non-Thermal Plasma with Radiation Therapy and Olaparib in a Panel of Breast Cancer Cell Lines. Cancers, 2020, 12, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastasov, N.; et al. Radiation resistance due to high expression of miR-21 and G2/M checkpoint arrest in breast cancer cells. Radiation Oncology (London, England), 2012, 7, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschenbrenner, B.; et al. Simvastatin Is Effective in Killing the Radioresistant Breast Carcinoma Cells. Radiol Oncol, 2021, 55, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S.; Rajagopalan, D.; Hora, S.; Jadhav, S.P. Breast Cancer: From Transcriptional Control to Clinical Outcome. in Breast Cancer - From Biology to Medicine, P. V. Pham, Ed. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ‘HCC70: A model of triple negative breast cancer’. Accessed: 22, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://oncology.labcorp.

- Steffen, A.-C.; Göstring, L.; Tolmachev, V.; Palm, S.; Stenerlöw, B.; Carlsson, J. Differences in radiosensitivity between three HER2 overexpressing cell lines. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging, 2008, 35, 1179–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, A.; Nasonova, E.; Kutsalo, P.; Czerski, K. Chromosomal radiosensitivity of human breast carcinoma cells and blood lymphocytes following photon and proton exposures. Radiat Environ Biophys, 2023, 62, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder-Heurich, B.; et al. Functional deficiency of NBN, the Nijmegen breakage syndrome protein, in a p.R215W mutant breast cancer cell line. BMC Cancer, 2014, 14, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobunai, T.; Watanabe, T.; Fukusato, T. ; REG4; NEIL2, and BIRC5 Gene Expression Correlates with Gamma-radiation Sensitivity in Patients with Rectal Cancer Receiving Radiotherapy. Anticancer Research, 2011, 31, 4147. [Google Scholar]

- Guardamagna, I.; Lonati, L.; Savio, M.; Stivala, L.A.; Ottolenghi, A.; Baiocco, G. An Integrated Analysis of the Response of Colorectal Adenocarcinoma Caco-2 Cells to X-Ray Exposure. Front Oncol, 2021, 11, 688919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morini, J.; Babini, G.; Barbieri, S.; Baiocco, G.; Ottolenghi, A. The Interplay between Radioresistant Caco-2 Cells and the Immune System Increases Epithelial Layer Permeability and Alters Signaling Protein Spectrum. Front Immunol, 2017, 8, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, A.L.; Price, M.E.; Mothersill, C.; McKeown, S.R.; Robson, T.; Hirst, D.G. Relationship between clonogenic radiosensitivity, radiation-induced apoptosis and DNA damage/repair in human colon cancer cells. Br J Cancer, 2003, 89, 2277–2283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rödel, C.; Haas, J.; Groth, A.; Grabenbauer, G.G.; Sauer, R.; Rödel, F. Spontaneous and radiation-induced apoptosis in colorectal carcinoma cells with different intrinsic radiosensitivities: Survivin as a radioresistance factor. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics, 2003, 55, 1341–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, R.E.; et al. Targeting Acid Ceramidase to Improve the Radiosensitivity of Rectal Cancer. Cells, 2020, 9, 2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L. ; Huang,Chunli; Yang,Xiaojun; Zhang,Qiuqin; Chen, ‘Prognostic roles of mRNA expression of peroxiredoxins in lung cancer. OncoTargets and Therapy, 2018, 11, 8381–8388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciesielska, S.; Slezak-Prochazka, I.; Bil, P.; Rzeszowska-Wolny, J. Micro RNAs in Regulation of Cellular Redox Homeostasis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2021, 22, 6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.; Kim, S.; Kang, D. The Role of Hydrogen Peroxide and Peroxiredoxins throughout the Cell Cycle. Antioxidants (Basel), 2020, 9, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Nie, J.; Wang, R.; Mao, W. The Cell Cycle G2/M Block Is an Indicator of Cellular Radiosensitivity. Dose-Response, 2019, 17, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamamoto, T.; et al. Correlation between γ-ray-induced G2 arrest and radioresistance in two human cancer cells. International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics, 1999, 44, 905–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Pearson, P.S.; Kooshki, M.; Spitz, D.R.; Poole, L.B.; Zhao, W.; Robbins, M.E. Decreasing peroxiredoxin II expression decreases glutathione, alters cell cycle distribution, and sensitizes glioma cells to ionizing radiation and H2O2. Free Radic Biol Med, 2008, 45, 1178–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciegienka, S.J.; et al. D-penicillamine combined with inhibitors of hydroperoxide metabolism enhances lung and breast cancer cell responses to radiation and carboplatin via H2O2-mediated oxidative stress. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 2017, 108, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohshour, M.O.; Najafi, L.; Heidari, M.; Sharaf, M.G. Antiproliferative Effect of H2O2 against Human Acute Myelogenous Leukemia KG1 Cell Line. Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies, 2013, 6, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilema-Enríquez, G.; Arroyo, A.; Grijalva, M.; Amador-Zafra, R.I.; Camacho, J. Molecular and Cellular Effects of Hydrogen Peroxide on Human Lung Cancer Cells: Potential Therapeutic Implications. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2016, 2016, 1908164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubezio, P.; Civoli, F. Flow cytometric detection of hydrogen peroxide production induced by doxorubicin in cancer cells. Free radical biology & medicine, 1994, 16, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, R.; et al. Hydrogen peroxide mediates the cell growth and transformation caused by the mitogenic oxidase Nox1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2001, 98, 5550–5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Coulter, J.A.; Yang, R. Octaarginine-modified gold nanoparticles enhance the radiosensitivity of human colorectal cancer cell line LS180 to megavoltage radiation. Int J Nanomedicine, 2018, 13, 3541–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.; et al. Impact of DNA repair and reactive oxygen species levels on radioresistance in pancreatic cancer. Radiotherapy and Oncology, 2021, 159, pp. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conour, J.E.; Graham, W.V.; Gaskins, H.R. A combined in vitro/bioinformatic investigation of redox regulatory mechanisms governing cell cycle progression. Physiol Genomics, 2004, 18, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehn, M.; et al. Association of Reactive Oxygen Species Levels and Radioresistance in Cancer Stem Cells. Nature, 2009, 458, 780–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmink, B.L.; et al. GPx2 Suppression of H2O2 Stress Links the Formation of Differentiated Tumor Mass to Metastatic Capacity in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Research, 2014, 74, 6717–6730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinema, F.V.; et al. MitoTam induces ferroptosis and increases radiosensitivity in head and neck cancer cells. Radiother Oncol, 2024, 200, 110503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, W.H. Hydrogen peroxide inhibits the growth of lung cancer cells via the induction of cell death and G1-phase arrest. Oncology Reports. 2018. 40, 1787–1794. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, H.; Takada, K. Reactive oxygen species in cancer: Current findings and future directions. Cancer Sci, 2021, 112, 3945–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Moore, B.; Bai, Q.; Cook, K. Hydrogen Peroxide Enhances Radiation-induced Apoptosis and Inhibition of Melanoma Cell Proliferation | Request PDF. Anticancer Research, 2013, 33, 1799–1807. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, R.; et al. Radiosensitization using hydrogen peroxide in patients with cervical cancer. Molecular and Clinical Oncology, 2021, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busato, F.; Khouzai, B.E.; Mognato, M. Biological Mechanisms to Reduce Radioresistance and Increase the Efficacy of Radiotherapy: State of the Art. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guichard, M.; Dertinger, H.; Malaise, E.P. Radiosensitivity of Four Human Tumor Xenografts. Influence of Hypoxia and Cell-Cell Contact. Radiation Research, 1983, 95, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolus, N.E. Basic Review of Radiation Biology and Terminology. Journal of Nuclear Medicine Technology, 2017, 45, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Description | Symbol | Value1 [mM] |

|---|---|---|

| CAT concentration | CAT | 0.001 |

| PRDX concentration | PRDX | 0.15 |

| TXN concentration | TXN | 0.025 |

| TXNRD concentration | TXNRD | 0.025 |

| GSH concentration | GSH | 3.0 |

| GPX concentration | GPX | 0.05 |

| GSR concentration | GSR | 0.05 |

| Description | Symbol | Value [unit] |

|---|---|---|

| Rate constant of CAT | kCAT | 0.034 [mM-1ms-1] |

| Rate constant of PRDX | kPRDX | 0.26 [mM-1ms-1] |

| Rate constant of TXN | kTXNox | 0.23 [mM-1ms-1] |

| Rate constant of TXNRD | kTXNRD | 0.31 [mM-1ms-1] |

| Rate constant of GSR | kGSR | 0.08 [mM-1ms-1] |

| Rate constant of GPX1 | kGPX | 67 [mM-2ms-1] |

| H2O2 influx to the system1 | H2O2IN | 10-6[mMms-1] |

| Type of cancer | Cell line | Radiosensitive (RS)/ Radioresistant (RR) |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | A549 | RR | [43] |

| H1703 | RR | [44] | |

| H661 | RR | [45] | |

| H1299 | RR | [46] | |

| H1339 | RR | [47] | |

| H292 | RR | [48] | |

| H358 | RR | [48] | |

| H23 | RS | [48] | |

| H441 | RS | [49] | |

| H1650 | RS | [50] | |

| H522 | RS | [50] | |

| HCC827 | RS | [44] | |

| H69 | RS | [51] | |

| H460 | RS | [52] | |

| Breast | MCF-7 | RR | [53,54,55] |

| SK-BR-3 | RR | [56] | |

| ZR-751 | RR | [57] | |

| HCC1428 | RR | [58] | |

| T47D | RR | [59,60] | |

| HS578T | RR | [54] | |

| UACC-812 | RR | [61] | |

| MDA-MB-175VII | RR | [58] | |

| MDA-MB-361 | RS | [59] | |

| HCC70 | RS | [62] | |

| MDA-MB-231 | RS | [53,55,60] | |

| BT474 | RS | [54,63] | |

| JIMT-1 | RS | [55] | |

| CAL-51 | RS | [64] | |

| HCC1395 | RS | [65] | |

| Colorectal | HT115 | RR | [66] |

| DLD-1 | RR | [66] | |

| Lovo | RR | [66] | |

| HT29 | RR | [66] | |

| Caco-2 | RR | [67,68] | |

| SW480 | RR | [69,70] | |

| MDST8 | RR | [71] | |

| Colo-201 | RS | [66] | |

| Colo-205 | RS | [66] | |

| Colo-320 | RS | [66] | |

| HCT116 | RS | [66] | |

| SW48 | RS | [69,70] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).