1. Introduction

The gneiss-dominated mountainous region of the Taihang Mountains is one of the areas in China severely affected by soil erosion. The ongoing impact of human activities has resulted in significant deterioration of the forest ecosystem and substantial biodiversity loss in this region. Consequently, forest degradation has occurred, manifesting in the transformation of forests into shrub lands and grassy slopes. This phenomenon has had deleterious effects on the soil, leading to exacerbated rates of erosion and an increase in the frequency of flood disasters [

1]. In order to enhance afforestation success within the specified site conditions and elevate farmers' living standards, mechanical land preparation has been utilised in recent years to manage the gneiss mountainous regions of the Taihang Mountains. This has resulted in the development of high-standard terraced fields with sloping gullies. The aforementioned fields have been cultivated with a range of economically viable tree species, including walnuts, apples, and cherries. This approach has not only led to the reforestation of barren mountains and the optimisation of land resource utilisation, but has also yielded substantial economic benefits. It has ensured optimal use of the limited soil, substantially increased vegetation cover in the mountainous areas, and dramatically enhanced the living standards of local residents [

2].

It is universally acknowledged that soil constitutes the foundation of agricultural production, supplying essential nutrients and water to crops and providing a stable medium for root growth. It is evident that a symbiotic relationship exists between plants and soil, where the cultivation of crops is contingent upon the inherent characteristics of the soil, including but not limited to, water availability, nutrient status, aeration, and temperature [

3,

4,

5]. Furthermore, the cultivation of crops exerts a specific influence on the soil's physical structure, nutrient equilibrium, and microbial community composition. The repeated cultivation of a single crop can result in a decline in soil nutrient balance, compromised soil quality, and a reduction in microbial diversity. This, in turn, can precipitate a decline in crop yield and quality [

6,

7,

8].

The management of agricultural activities has been demonstrated to have a profound impact on the composition and activity of soil microbial communities. This alteration is primarily caused by changes in the quantity and quality of plant residues entering the soil, as well as the excessive use of pesticides, fertilisers (synthetic or organic) and tillage practices. These changes in management have been shown to have significant consequences for soil quality, as evidenced by some studies [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. A study found that traditional tillage reduces the stability of aggregates, decreases the proportion of macroaggregates, and increases the proportion of microaggregates [

12]. The planting period exerts a significant influence on the soil's aggregate structure, in addition to altering its bulk density and porosity [

14]. Furthermore, the duration of crop cultivation has been demonstrated to influence the accumulation of nutrients and the flux of greenhouse gas emissions within the soil-vegetation system [

15,

16]. The practice of continuous crop cropping has been demonstrated to result in the accumulation of soil macro nutrients (e.g. organic matter, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, etc.). However, trace elements have been observed to exhibit differential changes, which has the potential to induce nutrient imbalance and consequently affect crop absorption, utilization, and growth health [

17,

18,

19,

20].

A mounting body of evidence suggests a close correlation between soil attributes and the composition of the soil microbial community [

21,

22]. It is evident that rhizosphere soil microorganisms play a pivotal role in the transformation and cycling of rhizosphere ecosystems, thereby contributing significantly to the maintenance of soil health [

23,

24]. However, it is imperative to acknowledge the profound impact of anthropogenic activities, such as ploughing, landfilling, pruning, and fertilising, on the composition of soil. These disturbances have the potential to induce changes in major physical, chemical or biological factors, which can further result in shifts in the structure and activity of soil microorganisms. Conversely, alterations in the community structure and functional diversity of rhizosphere soil microbes have been demonstrated to impact plant growth, fruit yield, and quality [

25,

26].

As demonstrated in the extant literature, the age of the fruit tree and its physiological status exert a significant influence on the composition of rhizosphere microorganism. Furthermore, by manipulating cultivation techniques that influence the structure of the rhizosphere microbial community, it is possible to regulate the growth and development of fruit trees [

27,

28]. However, the interrelationship between rhizosphere soil chemical indexes, microbial communities, and apple quality at different planting years remains to be elucidated.

Chronosequences have been proven to be an effective means of assessing the changing trends and rates of soil properties. This is achieved by replacing time with space, under the strict control of environmental factors [

29,

30]. Therefore, the decision was taken to select apple orchards of differing stand ages for the purpose of measuring changes in the microbial community structure and identifying the factors that led to these variations. The objective of this study is to explore the interactions between rhizosphere microorganisms and environmental factors, with a view to providing a scientific basis for the sustainable management of apple orchards in fragile mountain ecosystems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

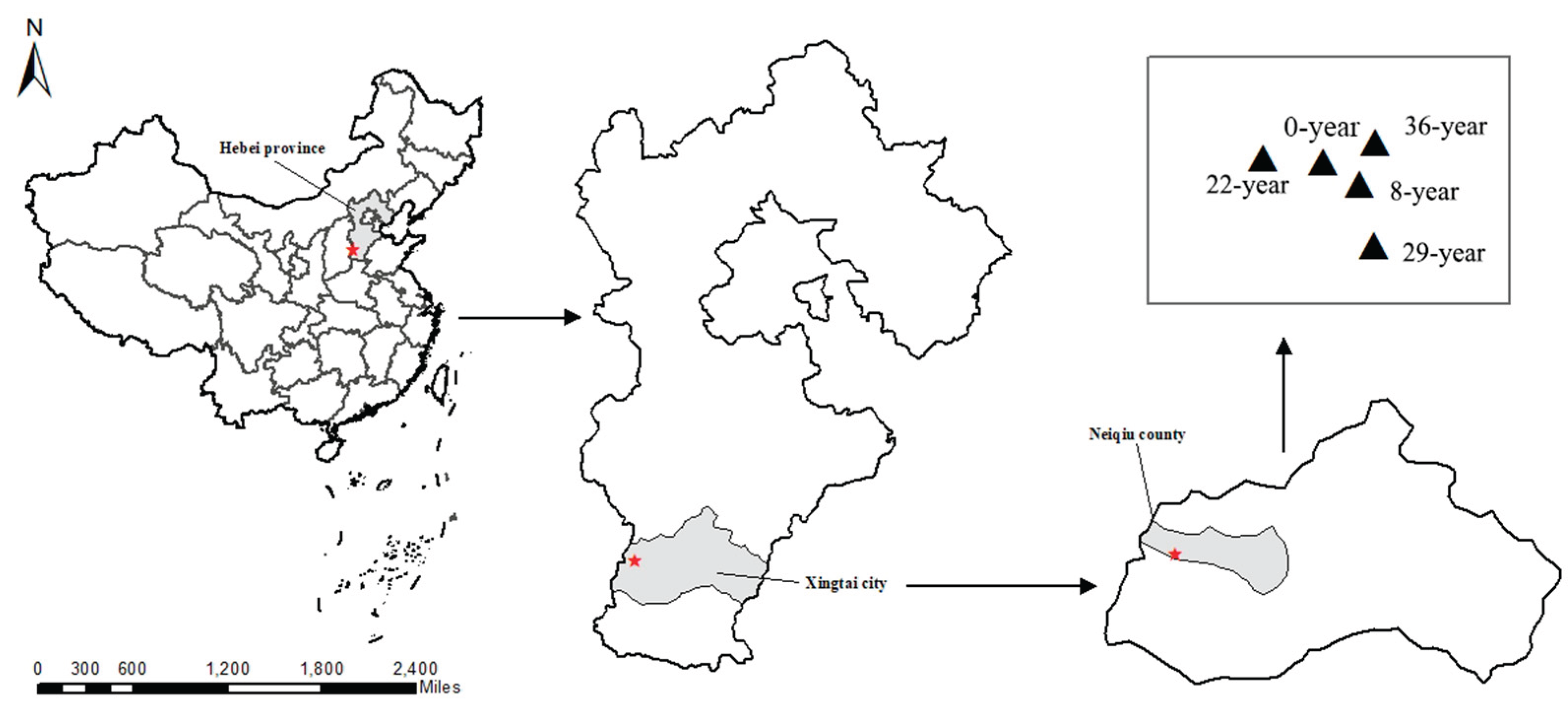

The study site (ca. 1500 ha) is located in Gangdi Village(114◦04′ -114◦06′ E, 37◦19′ -37◦22′ N,

Figure 1) , Neiqiu County, Hebei Province, China. This area belongs to a warm temperate monsoon climate with average annual temperature and precipitation of 11.8 ◦C and 685 mm, respectively. The frost-free period is 180 days. In addition, the soils in the study site are classified as Entisols in FAO Soil Taxonomy (FAO, 2014). Due to its remote location, the area has not been developed and utilized for a long time(>100 years). Notably, the trial sites have similar climatic and soil conditions because of the short distances (i.e., similar geomorphologic units; hills). Since 1984, the apple (variety 'Nagafu No.2’) was started planted in this region, and all apple plantations vary in their planting ages. The cultivation density of apple was set to about 667-1250 plants ha

-1 , and its row and plant spacing was 2.0-3.0 × 4.0-5.0 m. The field management measures (e.g., fertilization, pest prevention and weeding method, etc.) are similar among the trial sites.

2.2. Soil Sampling

The means of space-for-time replacement, a reliable method to monitor soil temporal changes, was applied to appraise the changing trends of soil variables (e.g., microbial characteristics) in a apple cultivation chronosequence which was situated on the same geomorphic units with similar management measures as well as soil and climatic status. Five chronosequence apple orchards (cultivar 'Nagafu No.2') representing continuous cultivation durations of 0-, 8-, 22-, 29-, and 36-year intervals (

Figure 1) were systematically investigated to quantify pedological evolution, including microbial community composition, bulk density stratification, pH dynamics, and associated biogeochemical parameters across cultivation decades. A completely randomized block design with three replicates was laid out for each apple plantation (15 plots; 3 replicates × 5treatments). The area of each plot was 100 m

2 (10 m × 10 m).

Soil sampling was conducted using a standardized protocol. Within each experimental plot, five soil cores (5cm diameter, 20cm depth) were randomly obtained from three soil depths (0–20, 20–40, and 40–60cm; major distribution area of apple root system) under apple canopies, and then, these soil samples were integrated into one combined sample. In total, 45 combined samples (15 plots × 3 depths) were obtained. After the removal of plant residues, macrofauna, and stones, these combined soil samples were carefully passed through a sieve (2mm) and then divided into two parts. One part was air-dried to determine soil physicochemical properties; the other part was conserved in a refrigerator (−80°C) for the measurement of soil microbial-associated characteristics.

2.3. Soil Environmental Chemistry Index Analysis

The Soil bulk density (BD) was determined using a ring with an internal volume of 50 cm

3 , while the capillary porosity(CP) and field capacity (FC) were determined using a Richards' pressure plate, all performed as described by Klute [

31]. The pH in the four aggregates was gauged in soil/water mixture (1:2.5) through a compound electrode pH meter(STARTER300, USA). The contents of soil organic matter (SOM) and total N (TN) were measured following the heated dichromate/titration method and the Semimicro Kjeldahl method [

32,

33], respectively. Total P content was determined by the molybdate colorimetric method after ascorbic acid reduction [

34]. Available nitrogen (AN) was determined by the alkaline hydrolysis diffusion method [

35]. Available P (AP) was extracted with 0.5 M sodium bicarbonate (pH 8.5) and determined by the Olsen method [

36]. Available K (AK) was extracted with 1 M ammonium acetate and then measured by atomic absorption spectrometry (NovAA300, Analytik Jena AG) [

37].

2.4. Soil Microbial Community (PLFAs) Analysis

To assess the impact of soil management practices on microbial activity and diversity, Microbial community Phospholipid Fatty Acids Analysis (PLFA) marker analysis and content calculation: PLFA was analyzed using the modified Bligh Dyer method [

38,

39]. Esterification C19:0 was used as the internal standard and measured using an Agilent 5890 gas chromatograph (GC). Different PLFA markers for specific microorganisms, 12: 0w, 14: 0w, 15: 0w, 16: 0w and 20: 0w marked bacteria, i15: 0w、a16: 0、i17: 0 and i18: 0 label Gram positive bacteria, i14: 0w label aerobic bacteria, 16: 1w9c labeled Gram negative bacteria, 10Me16: 0w tagged sulfate reducing bacteria, 10Mel17: 0w and 10Me18: 0w marked actinomycetes, 18: 0w tagged thermophilic hydrogen bacteria, 18: 1w9c and 18: 2w9 labeled fungi, 18: 1w7c labeled Pseudomonas aeruginosa, cy19: 0w8c labeled Burkholderia, 20: 4w6, 9, 12, 15 mark protozoa [

40]. The fatty acid nomenclature of Frostegård et al. [

41] was used.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The data was organized using Microsoft Office 2019. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Duncan tests was conducted to assess the effect of different apple plantation ages (or soil layer) on the physicochemical and microbial variables. Duncan tests were used for determining the significance level (p<0.05). Two-way ANOVA was conducted for comparing the differences in these soil variables with four apple plantation ages (0-, 8-, 22-, 29-and 36-years) and three soil depths (0–20, 20–40, and 40–60cm) as the main factors. SPSS 20.0 statistical software (SPSS, Chicago, United States) was used to perform the above-mentioned statistical analyses. Additionally, CANOCO software (version 5.0, Ithaca, NY) was applied for evaluated the effects of the soil physicochemical on microbial community through Redundancy analysis (RDA).

3. Results

3.1. Subsection Spatiotemporal Evolution of Soil Physical Properties

Soil acts as a critical medium for plant root growth and material-energy exchange, and its quality significantly influences crop health. The physical properties of soil in apple orchards with varying planting durations are summarized in

Table 1. As shown in

Table 1, the soil bulk density in the 0–20 cm, 20–40 cm, and 40–60 cm layers decreases gradually as the number of apple planting years increases. Specifically, during the first 8 years of planting, the decline is relatively rapid, with average annual reductions of 1.12%, 0.67%, and 1.43% for the respective layers. After 8 years, the changes become less pronounced, with average annual reductions of 0.40%, 0.60%, and 0.32%. The soil bulk density increases gradually with soil depth; however, this vertical gradient diminishes progressively as the number of years since apple planting increases. As the number of apple planting years increases, the capillary porosity and field water holding capacity in each soil layer gradually rise. Notably, changes in the 0–20 cm soil layer are more pronounced compared to those in the 40–60 cm layers. The soil capillary porosity and field water holding capacity gradually increase with soil depth, but this vertical difference gradually decreases with the extension of apple planting years.

3.2. Evolution of Soil Acidity and Alkalinity

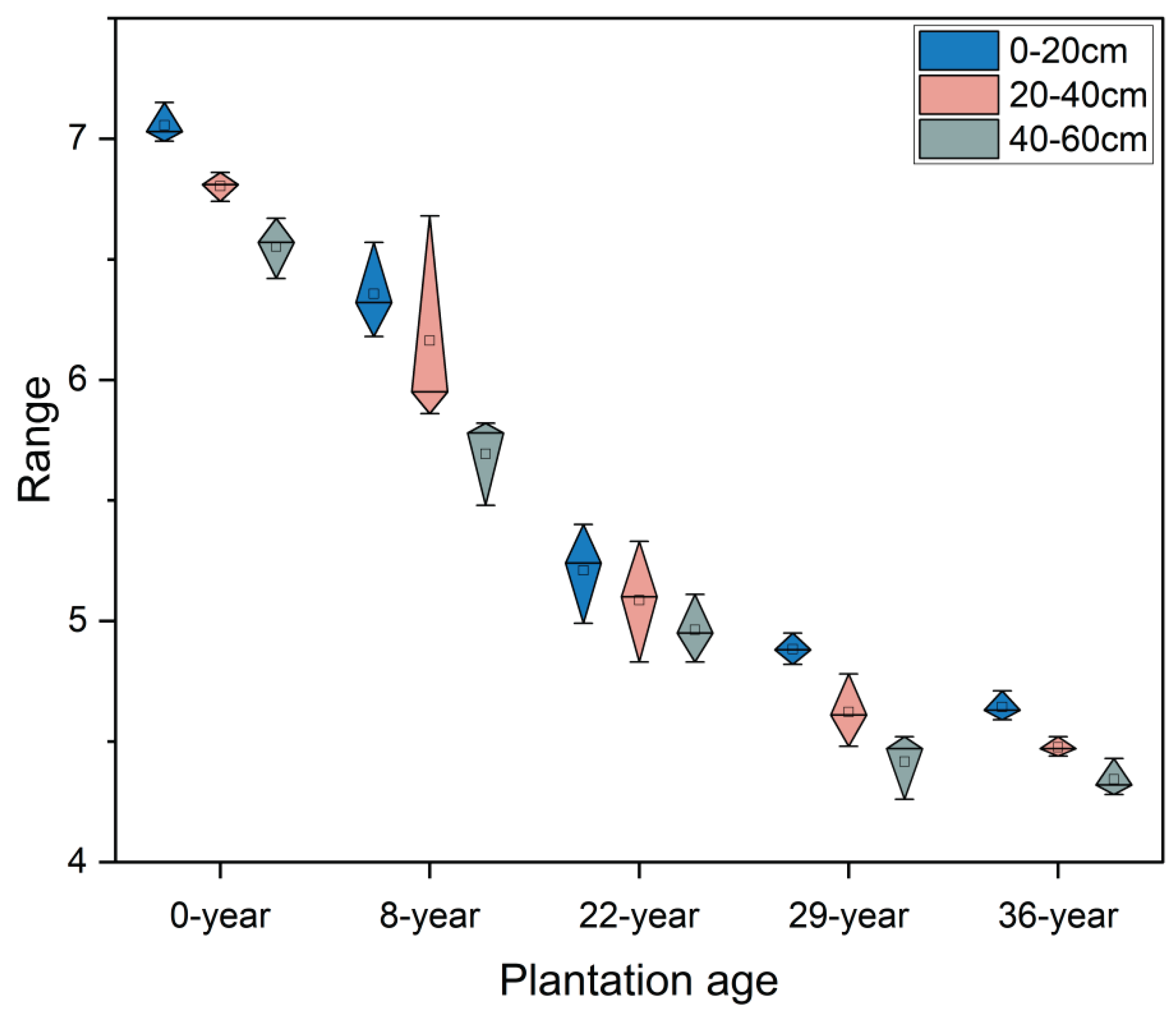

The pH value of soil solution is an important factor affecting plant growth and nutrient absorption. It can directly affect the absorption of minerals by plants and the activity of microorganisms in the soil, thereby further affecting the growth and development of plants. With the extension of apple planting years, the soil pH values in the 0-20cm, 20-40cm, and 40-60cm soil layers showed a gradually decreasing trend (

Figure 2). During the first 29 years of apple cultivation, soil pH decreased rapidly, The average annual decrease in soil layers of 0-20cm, 20-40cm, and 40-60cm is 1.06%, 1.11%, and 1.12%, respectively, and then gradually slows down thereafter. Vertically, the soil pH gradually decreases as the soil layer deepens, and this difference gradually decreases with the extension of apple planting years.

3.3. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Soil Fertility

Soil is the cornerstone of crop growth, and its fertility directly affects the growth, development, and final yield of crops. As shown in the table, with the extension of apple planting years, there have been significant changes in soil nutrients, but there are certain differences in the changing patterns of different nutrients. With the extension of apple planting years, SOM, TP, AN, and AK show a trend of first increasing and then stabilizing. Compared to 0-year, SOM, TP, AN, and AK of each soil layer in 36-year apple orchard has increased by 0.26-2.44, 0.86-1.41, 0.87-1.17, 0.24-0.46. With the extension of apple planting years, the AP in the soil continues to increase. Compared to the 0-year, The AP of the 0-20cm, 20-40cm, and 40-60cm in the 36-year apple orchard increased by 1.95-fold, 1.57-fold, and 2.90-fold, respectively. With the extension of apple planting years, the TN of soil shows a trend of first increasing and then decreasing. The TN of 0-20cm reaches its highest at 22-year, and 40-60cm reaches its highest at 29-year. In the vertical profile, soil nutrients decline as the soil layer deepens. Notably, the variations in SOM, TP, AN, and AP are more pronounced along the vertical gradient. Moreover, these differences gradually increase with the prolonged duration of apple cultivation.

Table 2.

Soil nutrient content of apple orchards with different planting years.

Table 2.

Soil nutrient content of apple orchards with different planting years.

| Indices |

plantation

age |

Soil depths |

| 0-20cm |

20-40cm |

40-60cm |

SOM

(g kg-1) |

0-year |

9.50 ± 0.80 e |

8.23 ± 0.53 c |

6.72 ± 0.80 b |

| 8-year |

14.60 ± 1.39 d |

10.43 ± 1.39 bc |

7.88 ± 0.80 ab |

| 22-year |

21.32 ± 1.45 c |

11.36 ± 2.12 bc |

7.88 ± 0.80 ab |

| 29-year |

36.14 ± 1.21 b |

12.75 ± 2.89 ab |

8.69 ± 0.35 a |

| 36-year |

32.67 ± 1.39 a |

15.99 ± 2.51 a |

8.46 ± 0.72 a |

TN

(g kg-1) |

0-year |

0.45 ± 0.04 a |

0.51 ± 0.03 a |

0.48 ± 0.07 a |

| 8-year |

0.68 ± 0.09 ab |

0.55 ± 0.03 a |

0.59 ± 0.07 ab |

| 22-year |

0.82 ± 0.03 bc |

0.48 ± 0.03 ab |

0.37 ± 0.02 bc |

| 29-year |

0.77 ± 0.05 c |

0.57 ± 0.01 ab |

0.68 ± 0.07 c |

| 36-year |

0.57 ± 0.08 d |

0.52 ± 0.06 b |

0.46 ± 0.05 c |

TP

(g kg-1) |

0-year |

0.43 ± 0.03 c |

0.49 ± 0.11 c |

0.40 ± 0.06 b |

| 8-year |

0.72 ± 0.13 b |

0.53 ± 0.06 c |

0.49 ± 0.46 ab |

| 22-year |

0.97 ± 0.20 ab |

0.70 ± 0.26 bc |

0.64 ± 0.03 ab |

| 29-year |

1.10 ± 0.10 a |

0.95 ± 0.13 a |

0.90 ± 0.14 a |

| 36-year |

1.03 ± 0.15 a |

0.92 ± 0.10 ab |

0.90 ± 0.05 a |

AN

(mg kg-1) |

0-year |

73.97 ± 11.85 b |

68.13 ± 0.40 b |

45.27 ± 4.28 b |

| 8-year |

80.73 ± 7.18 b |

70.00 ± 4.90 b |

63.93 ± 15.48 b |

| 22-year |

91.47 ± 14.57 b |

76.30 ± 7.95 b |

65.33 ± 6.80 b |

| 29-year |

158.20 ± 4.20 a |

131.25 ± 5.95 a |

96.60 ± 13.50 a |

| 36-year |

144.90 ± 3.50 a |

127.17 ± 15.08 a |

98.23 ± 25.34 a |

AP

(mg kg-1) |

0-year |

47.60 ± 9.30 c |

40.93 ± 0.40 b |

20.41 ± 1.39 d |

| 8-year |

77.14 ± 12.69 bc |

52.10 ± 4.37 b |

33.43 ± 2.91 c |

| 22-year |

79.40 ± 59.41 bc |

65.41 ± 6.30 ab |

39.73 ± 1.62 c |

| 29-year |

122.33 ± 9.93 ab |

71.93 ± 48.99 ab |

54.67 ± 6.41 b |

| 36-year |

140.67 ± 4.24 a |

105.19 ± 7.64 a |

79.60 ± 13.45 a |

AK

(mg kg-1) |

0-year |

230.43 ± 12.75 b |

203.47 ± 22.05 c |

208.37 ± 3.45 b |

| 8-year |

198.57 ± 11.75 c |

205.90 ± 13.70 c |

208.37 ± 1.45 b |

| 22-year |

252.50 ± 9.30 b |

262.30 ± 20.60 b |

237.77 ± 26.95 b |

| 29-year |

281.90 ± 8.30 a |

299.07 ± 18.65 a |

291.70 ± 17.20 a |

| 36-year |

286.80 ± 25.50 a |

296.60 ± 18.10 a |

281.87 ± 27.45 a |

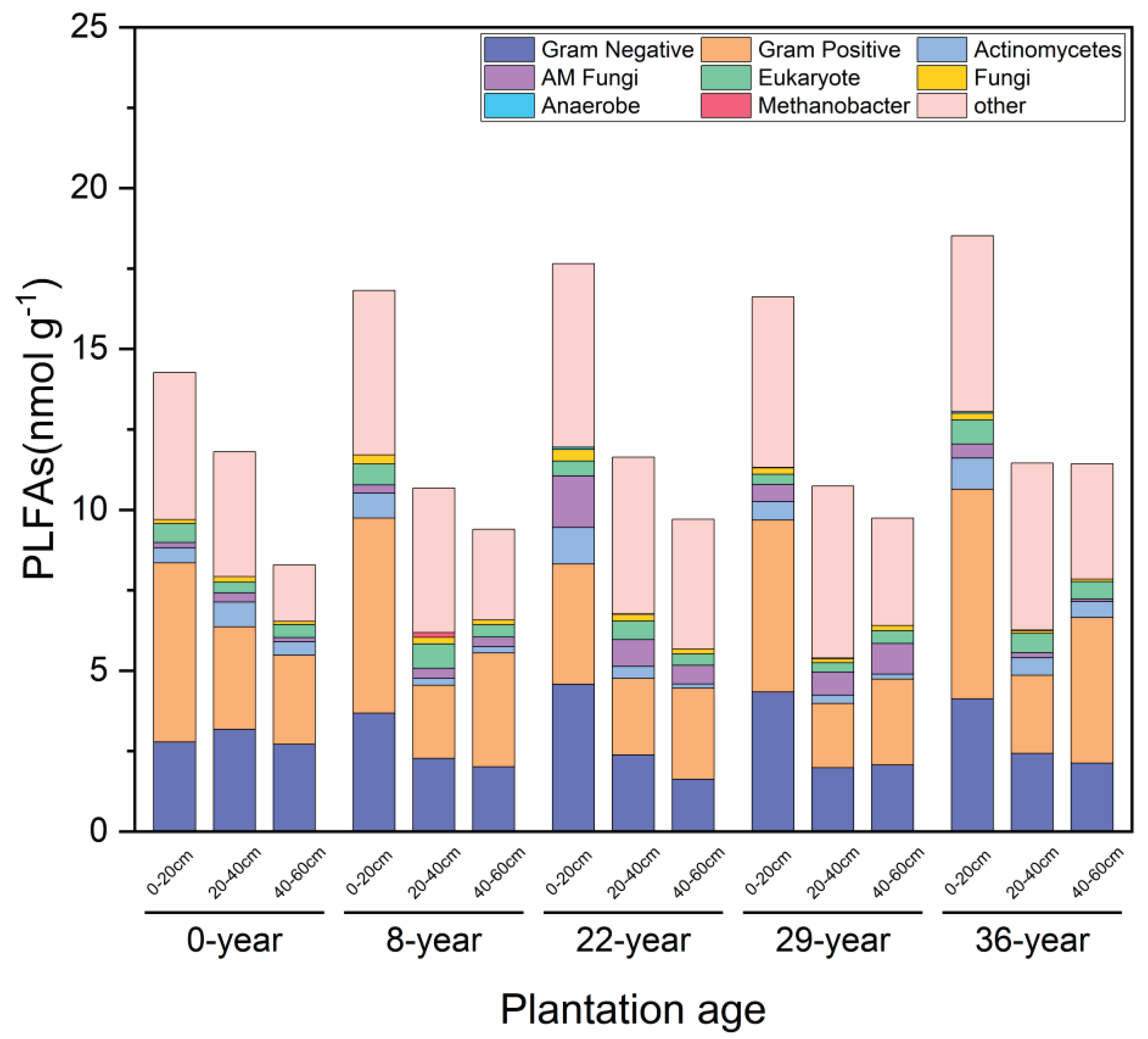

3.4. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Soil Microbial Quantity and Species

Soil microorganisms are an indispensable component of soil, playing an important role in maintaining soil ecological balance and biodiversity. In terms of the history of apple cultivation, with the extension of apple planting years, the total PLFAs content of soil microbial communities in the 0-20cm and 40-60cm soil layers showed a gradually increasing trend, among which Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria contributed relatively more. The total PLFAs content of the soil microbial community in the soil layer of 20-40 cm fluctuates, and among them, Gram-positive bacteria and Gram-negative bacteria contribute more significantly(

Figure 3). Vertically, the total PLFAs content of the soil microbial community gradually decreases as the soil layer deepens. However, with the extension of the apple cultivation years, the difference between the soil layers of 0-20 cm and 20-40 cm gradually increases, while the difference between the soil layers of 20-40 cm and 40-60 cm gradually decreases.

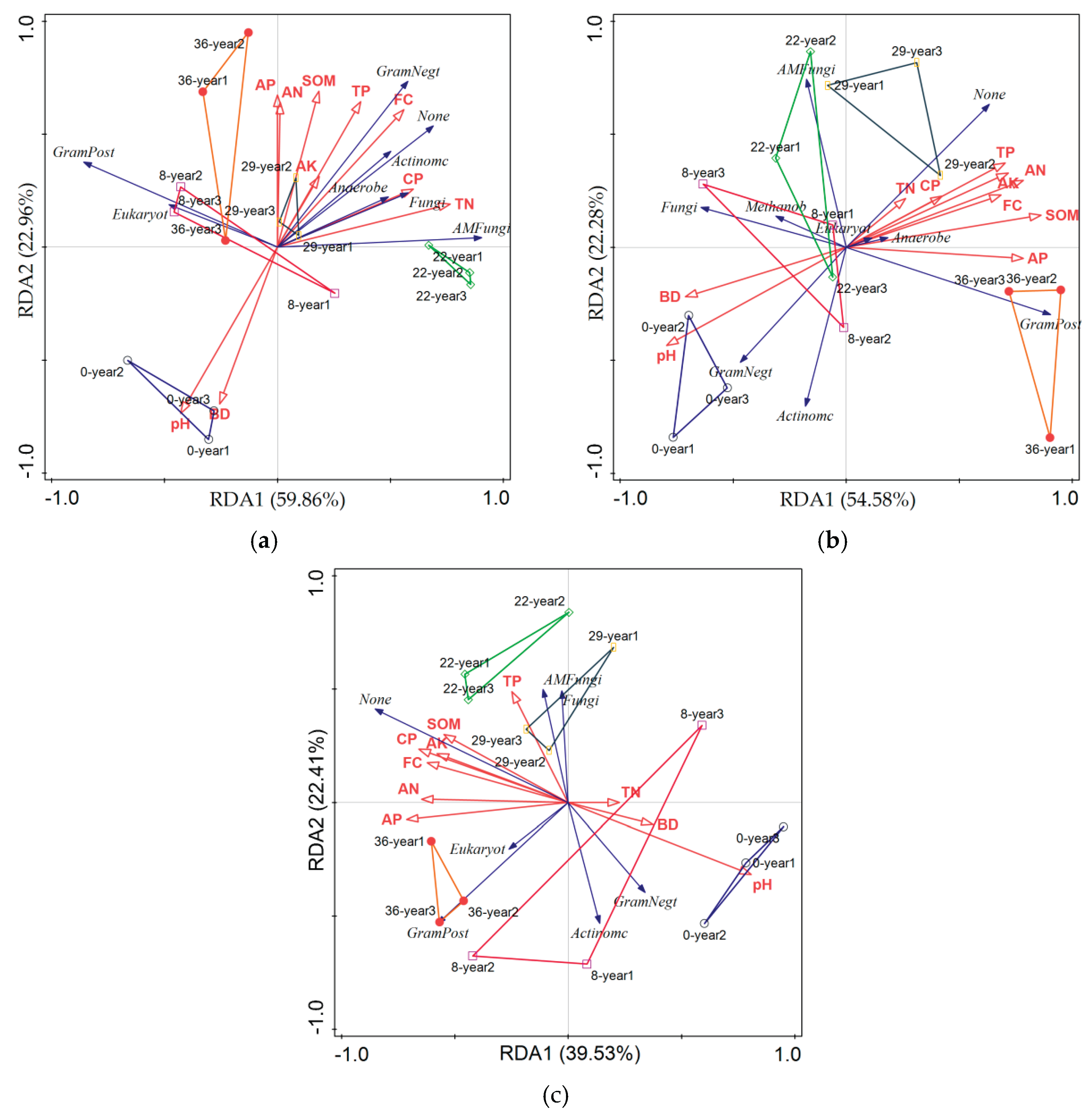

3.5. Correlation Between Soil Physical and Chemical Properties and Soil Microbial Communities

To further elucidate the correlation between soil physicochemical properties and microbial community characteristics, redundancy analysis (RDA) was conducted using soil microbial components and soil physicochemical properties as variables. The RDA analysis results (

Figure 4) show that in the 0-20cm soil layer, RDA1 and RDA2 explain 59.86% and 22.96% of the variance variation, respectively, with a cumulative contribution rate of 82.82%; In the 20-40cm soil layer, RDA1 and RDA2 explain 53.93% and 21.64% of the variance variation, respectively, with a cumulative contribution rate of 75.57%; In the 40-60cm soil layer, RDA1 and RDA2 explain 39.53% and 22.40% of the variance variation, respectively, with a cumulative contribution rate of 61.93%. From the microbial community composition of the sampling points, except for 8-year, the soil sampling points of apple orchards with other planting years are distributed on the symmetrical plane of 0-year. This indicates that the duration of apple cultivation has a significant impact on the community structure of soil microorganisms. Regardless of the soil layer, the Gram Positive community is consistent or similar to the 36 year soil sample point. According to forward analysis, soil Gram Negative and Actinomycetes communities are mainly influenced by pH, BD, and TP, while Gram Positive and Eukaryote communities are less affected by soil environmental factors.

4. Discussion

Soil, serving as the fundamental medium for plant root development and material-energy exchange, modulates crop health via the synergistic interactions of physical, chemical, and biological processes in terms of its quality status [

42]. Simultaneously, the interaction between crops and soil can modify the physicochemical characteristics and microbial community structure of the soil [

43]. This study investigates the spatiotemporal dynamics of soil quality in the gneiss mountainous regions of the Taihang Mountains under apple cultivation. By conducting multidimensional analyses of orchard soils with varying planting durations, a range of intricate and significant changing patterns are elucidated.

With the increase in apple planting years, significant changes have occurred in soil physical properties. Specifically, soil bulk density has decreased while porosity has increased. These alterations are primarily attributed to orchard management practices, including deep plowing and fertilization, as well as root growth activities. The penetration of root systems and the secretion of root exudates have improved soil aggregate structure, thereby enhancing soil porosity and reducing bulk density [

44,

45]. Due to the accumulation of soil organic carbon and total nitrogen, the soil physical structure is improved, and the nutrient content increases gradually [

46,

47]. However, we findings are slightly different from the findings of [

48]. that as planting years increased, soil porosity in goji berry orchards continuously decreased. This phenomenon is primarily associated with the reduction in soil organic carbon within goji berry orchards. Specifically, deep plowing, weeding, and fruit picking operations conducted between rows in goji berry orchards have disrupted soil aggregate structure, accelerated the decomposition of soil organic carbon, and consequently led to an increase in soil bulk density and a decrease in porosity.

Regarding soil nutrients, this study revealed that the soil organic matter content exhibits a gradual upward trend as the apple planting years accumulate. In the initial stages of cultivation, the substantial application of organic fertilizers and the relatively high vegetation coverage in orchards effectively contribute to the augmentation of soil organic matter. As the planting duration extends, soil microbial activity gradually stabilizes, nutrient cycling approaches equilibrium, and the soil nutrient content remains relatively stable at a certain level. The trends were consistent with the findings of Hou et al. [

49]. Notably, these findings contrast with those of Xu et al. [

50], who reported a decline in the organic matter content of orchard soil for apple trees aged between 8 and 15 years. The primary cause of this discrepancy is attributed to the long - term over - reliance on inorganic fertilizers, coupled with a neglect of organic fertilizer application. This highlights the importance of balanced fertilization strategies in maintaining optimal soil health and fertility in apple orchards.

As the number of apple planting years increases, the contents of soil nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus initially exhibit an upward trend, followed by a stabilization phase. These findings are consistent with the research results reported by Zhang et al. [

19] and Hou et al. [

49]. Zhang et al. [

19] further discovered that while the total nitrogen content in orchard soil significantly increased over extended planting periods, there were marked variations in the growth rates of different organic nitrogen components. Specifically, the rise in the proportion of non - acidic nitrogen decreases the mineralization rate of soil organic nitrogen, thereby impacting the supply capacity of soil inorganic nitrogen. In addition, Huang et al. [

51] discovered that long - term rice cultivation substantially modified the transformation of surface soil phosphorus and diminished its adsorption capacity. This phenomenon is likely associated with the alterations in the soil microbial community structure and the decline in enzyme activity.

Regarding soil acidification, our study revealed that the soil pH value exhibited a gradual decline as the apple cultivation period lengthened. This finding aligns with the research conducted by Li et al. [

52] in apple orchards situated on the Loess Plateau. The observed acidification is likely attributed to two primary factors: long - term fertilization practices and the release of exudates from apple roots. The application of acidic fertilizers, combined with the selective uptake of cations by the roots, disrupts the soil's inherent acid - base equilibrium [

53,

54]. Soil acidification can significantly influence the bioavailability of specific nutrients and reshape the soil microbial community structure. These changes, in turn, have the potential to exert profound impacts on crop growth and development, highlighting the need for comprehensive management strategies to mitigate the detrimental effects of soil acidification in apple orchards.

In the context of soil biological properties, the soil microbial biomass demonstrates a gradual upward trajectory as the apple planting years accumulate. The trends were consistent with the findings of Peruzzi et al. [

55]. Moreover, the structure of soil microbial communities in orchards with varying planting durations has undergone substantial transformations. The root exudates of fruit trees,which change across growth stages,provide diverse carbon sources that distinctly influence the colonization patterns of rhizosphere bacterial communities [

56]. The shifts in dominant bacterial species and their relative abundances are intricately linked to changes in soil physicochemical properties, with soil organic matter playing a particularly crucial role [

57]. Conversely, Arafat [

58] reported that as the tea tree planting years increase, the diversity of microbial communities in the rhizosphere soil of tea trees declines, likely due to the decrease in soil organic matter content. These contrasting findings suggest that long - term monoculture cultivation does not inevitably lead to a decrease in soil microbial community diversity. Instead, this outcome is highly contingent upon cultivation management practices, highlighting the importance of adopting appropriate management strategies to maintain or enhance soil microbial diversity in agricultural systems.

Regarding the spatial distribution, soil quality indicators exhibit pronounced disparities across varying soil depths. The surface soil layer (0 - 20 cm) has witnessed a notable enhancement in soil quality, primarily attributed to the direct influence of orchard management practices and the intensive activity of plant roots. Consequently, all relevant indicators in this layer outperform those of the deeper soil strata. As the soil depth increases, the rate of change in soil physical, chemical, and biological properties gradually diminishes. This vertical differentiation underscores the critical importance of tailoring fertilization, irrigation, and other management strategies to the distinct characteristics of different soil layers in orchard management. By doing so, we can optimize the utilization of soil resources and fully realize the soil's productive potential, ensuring sustainable and efficient apple cultivation.

5. Conclusions

Apple cultivation has exerted a profound impact on the physical, chemical, and biological properties of the soil in the gneiss mountainous regions of the Taihang Mountains. As the number of cultivation years increases, a series of discernible changes occur: soil bulk density decreases while porosity increases; the contents of soil organic matter, nitrogen, phosphorus, and other nutrients initially rise and subsequently stabilize; conversely, the soil pH value shows a declining trend. Additionally, soil microbial biomass has experienced a remarkable increase, accompanied by alterations in the microbial community structure.

Significant vertical differentiation is evident in soil quality indicators across various spatial layers, with more pronounced improvements observed in surface soil (0 - 20 cm) compared to deeper soil layers. This spatiotemporal evolution pattern offers a crucial scientific foundation for the sustainable management of apple orchards in the gneiss mountainous areas of the Taihang Mountains.

For future apple orchard management, it is imperative to implement targeted measures in accordance with the spatiotemporal characteristics of soil quality changes. Specifically, fertilization strategies should be adjusted rationally, with a particular focus on preventing and controlling soil acidification. Irrigation systems need to be optimized to enhance water use efficiency. Moreover, soil cultivation management should be strengthened to promote the improvement of soil structure. By adopting these comprehensive approaches, we can effectively maintain and enhance soil quality, thereby ensuring the long - term and sustainable development of the apple industry in this region.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Y. and Z.X.; methodology, L.Y., Z.X. and L.X.; software, L.X.; validation, L.Y., Z.X. and L.Z.; investigation, L.Y.; data curation, L.Y. and L.X.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Y.; writing—review and editing, L.Y., Z.X., L.X., L.Z. and C.M.; project administration, G.F.; funding acquisition, G.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Introducing Top Talent Program of Shandong (2023YSYY-006), National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFD1400800), and the Agricultural Scientific and Technological Innovation Project of Shandong Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CXGC2025F05).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article / Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the many graduate students and staff who are not listed as coauthors but were involved in maintaining the long-term field experiments and collecting the soil samples.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Guo, S.; Xu, Y. Analysis on Species Diversity of Vegetation in Restoration and Efficiency of Water in With Gneissose of Taihangshan Mountian Region. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 2007, 21, 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hou, Z.; Zhao, S.; Qi, G.; Zhang, X.; Guo, S. Evolution of plant species diversity and soil characteristics on hillslopes during vegetation restoration in the gneiss region of the Taihang Mountains after reclamation. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2018, 38, 5331–5339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaichi, M.R.; Keshavarz-Afshar, R.; Lu, B.; Rostamza, M. Growth and nutrient uptake of tomato in response to application of saline water, biological fertilizer, and surfactant. Journal of Plant Nutrition 2016, 40, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Wang, J.; Mostofa, M.G.; Fornara, D. Optimal water and fertilizer applications improve growth of Tamarix chinensis in a coal mine degraded area under arid conditions. Physiologia Plantarum 2020, 172, 371–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worou, O.N.; Gaiser, T.; Saito, K.; Goldbach, H.; Ewert, F. Simulation of soil water dynamics and rice crop growth as affected by bunding and fertilizer application in inland valley systems of West Africa. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment 2012, 162, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesarano; Zotti; Antignani; Marra; Scala; Bonanomi. SOIL SICKNESS AND NEGATIVE PLANT-SOIL FEEDBACK: A REAPPRAISAL OF HYPOTHESES. J PLANT PATHOL 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzola, M.; Manici, L.M. Apple Replant Disease: Role of Microbial Ecology in Cause and Control. Annual Review of Phytopathology 2012, 50, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weller, D.M. Microbial populations responsible for specific soil suppressiveness to plant pathogens. Annual Review of Phytopathology 2002, 40, 309–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- álvarez-Martín, A.; Hilton, S.L.; Bending, G.D.; Rodríguez-Cruz, M.S.; Sánchez-Martín, M.J. Changes in activity and structure of the soil microbial community after application of azoxystrobin or pirimicarb and an organic amendment to an agricultural soil. Applied Soil Ecology 2016, 106, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbuthia, L.W.; Acosta-Martínez, V.; Debryun, J.; Schaeffer, S.; Tyler, D.; Odoi, E.; Mpheshea, M.; Walker, F.; Eash, N. Long term tillage, cover crop, and fertilization effects on microbial community structure, activity: Implications for soil quality. Soil Biology & Biochemistry 2015, 89, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, B.R. Litter decomposition and organic matter turnover in northern forest soils. Forest Ecology & Management 2000, 133, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott,, E.T. Aggregate Structure and Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus in Native and Cultivated Soils1. Soil Science Society of America Journal 1986, 50, 627–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Sharma, P.K. Effect of long-term manuring and fertilizers on carbon pools, soil structure, and sustainability under different cropping systems in wet-temperate zone of northwest Himalayas. Biology&Fertility of Soils 2007, 44, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Qiu, W.; Hu, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, M.; Zhang, D.; Wu, T.; Tian, P.; Jiang, Y. Effects of cultivation history in paddy rice on vertical water flows and related soil properties. Soil and Tillage Research 2020, 200, 104613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, A.D.; Ribeiro, F.P.; Figueiredo, C.C.d.; Muller, A.G.; Vitoria Malaquias, J.; Santos, I.L.D.; Sá, M.A.C.d.; Soares, J.P.G.; Santos, M.V.A.D.; Carvalho, A.M.d. “Effects of soil management, rotation and sequence of crops on soil nitrous oxide emissions in the Cerrado: A multi-factor assessment”. Journal of Environmental Management 2023, 348, 119295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.H.; Liang, Z.W.; Suarez, D.L.; Wang, Z.C.; Wang, M.M.; Yang, H.Y.; Liu, M. Impact of cultivation year, nitrogen fertilization rate and irrigation water quality on soil salinity and soil nitrogen in saline-sodic paddy fields in Northeast China. The Journal of Agricultural Science 2015, 154, 632–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lewis, E.E.; Liu, Q.; Li, H.; Bai, C.; Wang, Y. Effects of long-term continuous cropping on soil nematode community and soil condition associated with replant problem in strawberry habitat. Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 30466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Yu, S. Vertical Distribution of Cu and Pd in Greenhouse Soils with Different Growing Years. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation 2016, 30, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, T.; Zucong, C. Characteristics of soil organic nitrogen components of orchards with different planting ages. Chinese Journal of Ecology 2015, 34, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.-W.; Li, K.; Guo, Y.-S.; Li, C.-X.; Xie, H.-G.; Hu, X.-X.; Zhang, L.-H.; Sun, Y.-N. Root zone soil nutrient change of vineyard with different planting years and related effect on replanted grape growth. Chinese Journal of Eco-Agriculture 2010, 18, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.-F.; Hou, Y.-L.; Ge, M.-Y.; Wang, K.; Liu, S.; Zhang, S.-L.; Li, G.; Chen, F. Carbon Dynamics of Reclaimed Coal Mine Soil under Agricultural Use: A Chronosequence Study in the Dongtan Mining Area, Shandong Province, China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuber, S.M.; Villamil, M.B. Meta-analysis approach to assess effect of tillage on microbial biomass and enzyme activities. Soil Biology & Biochemistry 2016, 97, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, C.S.; Hjelms?, M.H. Agricultural soils, pesticides and microbial diversity. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2014, 27, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.Y.; Xu, J.H.; Wu, L.K.; Wu, H.M.; Lin, W.X. Analysis of physicochemical properties and microbial diversity in rhizosphere soil of Achyranthes bidentata under different cropping years. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2017, 37, 5621–5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Chen, M.; Miao, P.; Cheng, W.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Ye, J.; Jia, X.; Wang, H. Effects of Different Planting Years on Soil Physicochemical Indexes, Microbial Functional Diversity and Fruit Quality of Pear Trees. Agriculture 2024, 14, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wenqing, L.I.; Binghai, D.U.; Hanhao, L.I. Effect of biochar applied with plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria(PGPR)on soil microbial community composition and nitrogen utilization in tomato. Pedosphere 2021, 31, 872–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Han, K.; Cai, Y.; Mu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, M.; Hou, C.; Gao, M.; Zhao, Q. Characterization of rhizosphere bacterial community and berry quality of Hutai No.8 (Vitis vinifera L.) with different ages, and their relations. Journal of the science of food and agriculture 2019, 99, 4532–4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Tang, Y.; Hu, C.; Zhan, T.; Zhao, X. Soil Applied Ca, Mg and B altered Phyllosphere and Rhizosphere Bacterial Microbiome and Reduced Huanglongbing Incidence in Gannan Navel Orange. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 791, 148046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uri, V.; Kukumägi, M.; Aosaar, J.; Varik, M.; Becker, H.; Aun, K.; Lõhmus, K.; Soosaar, K.; Astover, A.; Uri, M.; et al. The dynamics of the carbon storage and fluxes in Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) chronosequence. Science of the Total Environment 2022, 817, 152973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bokhorst, S.; Kardol, P.; Bellingham, P.J.; Kooyman, R.M.; Richardson, S.J.; Schmidt, S.; Wardle, D.A. Responses of communities of soil organisms and plants to soil aging at two contrasting long-term chronosequences. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2016, 106, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klute, A.; Fritschedanielson, R.; Sutherland, P.; Blake, G.; Hartge, K.; Bradford, J.; Bower, G.H.; Gee, G.W.; Bauder, J.; Gee, D.G. Methods of Soil Analysis 2d ed., pt. 1; Physical and Mineralogical Methods. Methods of Soil Analysis.part.physical & Mineralogical Methods 1986, 146, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebius, L.J. A Rapid Method for the Determination of Organic Carbon in Soil. Analytica Chimica Acta 1960, 22, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bremner, J.M. Determination of nitrogen in soil by the Kjeldahl method. Journal of Agricultural Science 1960, 55, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.; Riley, J.P. A modified single solution method for the determination of phosphate in natural waters. Analytica Chimica Acta 1962, 27, 678–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarma, B.; Farooq, M.; Gogoi, N.; Borkotoki, B.; Kataki, R.; Garg, A. Soil organic carbon dynamics in wheat - green gram crop rotation amended with Vermicompost and Biochar in combination with inorganic fertilizers: A comparative study. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 201, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulery, A.L.; Drees, L.R.; Baltensperger, D.; Barbarick, K.; Editorinchief, A.S.A.; Roberts, C.; Editorinchief, C.; Logsdon, S.; Editorinchief, S. Methods of Soil Analysis Part 5 — Mineralogical Methods. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottomley; P., S. [SSSA Book Series] Methods of Soil Analysis: Part 2—Microbiological and Biochemical Properties || Plasmid Profiles. 1994. [CrossRef]

- Dyer, E.G.; Bligh, W.J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Canadian Journal of Biochemistry and Physiology 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siles, J.A.; Gomez-Perez, R.; Vera, A.; Garcia, C.; Bastida, F. A comparison among EL-FAME, PLFA, and quantitative PCR methods to detect changes in the abundance of soil bacteria and fungi. Soil Biology & Biochemistry 2024, 198, 109557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, X.; Ning, D.; Zhou, X.; Feng, J.; Yuan, M.M.; Liu, S.; Guo, J.; Gao, Z.; et al. Reduction of microbial diversity in grassland soil is driven by long-term climate warming. Nature Microbiology 2022, 7, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frostegård, A.; Tunlid, A.; Bååth, E. Phospholipid Fatty Acid Composition, Biomass, and Activity of Microbial Communities from Two Soil Types Experimentally Exposed to Different Heavy Metals. Applied & Environmental Microbiology 1993, 59, 3605–3617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wu, H.; Wu, T.; Luo, Z.; Lin, W.; Liu, H.; Xiao, J.; Luo, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y. Soil microbial influences over coexistence potential in multispecies plant communities in a subtropical forest. Ecology 2024, 105, e4415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippot, L.; Chenu, C.; Kappler, A.; Rillig, M.C.; Fierer, N. The interplay between microbial communities and soil properties. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2023, 22, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumert, V.L.; Vasilyeva, N.A.; Vladimirov, A.A.; Meier, I.C.; Mueller, C.W. Root Exudates Induce Soil Macroaggregation Facilitated by Fungi in Subsoil. Frontiers in Environmental Science 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, C.J.; Pierret, A. Plant Roots and Soil Structure. Springer Netherlands 2011, 628–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras, M.D.L. Development of soil physical structure and biological functionality in mining spoils affected by soil erosion in a Mediterranean-Continental environment. Geoderma 2009, 149, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ?ourková, M.; Frouz, J.; Fettweis, U.; Bens, O.; Hüttl, R.F.; ?antr??ková, H. Soil development and properties of microbial biomass succession in reclaimed post mining sites near Sokolov (Czech Republic) and near Cottbus (Germany). Geoderma 2005, 129, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Qi, C.; Song, Y.; Peng, T.; Zhang, C.; Li, K.; Pu, M.; Sun, H.; Li, J.; He, X.; et al. Key Soil Abiotic Factors Driving Soil Sickness in Lycium barbarum L. Under Long-Term Monocropping. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Cheng, X.; Li, J.; Dong, Y. Magnesium and nitrogen drive soil bacterial community structure under long-term apple orchard cultivation systems. Applied Soil Ecology 2021, 167, 104103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Lu, X.; Li, J. Research on the Evolution Trend of Soil Nutrient of Different Tree Ages in Weibei Dry Plateau. Journal of Anhui Agricultural Sciences 2008, 36, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-M.; Thompson, A.; Zhang, G.-L. Long-term paddy cultivation significantly alters topsoil phosphorus transformation and degrades phosphorus sorption capacity. Soil and Tillage Research 2014, 142, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Andom, O.; Li, Y.; Cheng, C.; Deng, H.; Sun, L.; Li, Z. Responses of grape yield and quality, soil physicochemical and microbial properties to different planting years. European Journal of Soil Biology 2023, 120, 103587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neog, R. Assessing the impact of chemical fertilizers on soil acidification: A study on Jorhat district of Assam, India. Agricultural Science Digest 2018, 38, 270–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, A. Soil acidification from use of too much fertilizer. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 1994, 25, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peruzzi, E.; Franke-Whittle, I.H.; Kelderer, M.; Ciavatta, C.; Insam, H. Microbial indication of soil health in apple orchards affected by replant disease. Applied Soil Ecology 2017, 119, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippot, L.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Lemanceau, P.; Van, d.P.; Wim, H. Going back to the roots: The microbial ecology of the rhizosphere. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2013, 11, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, H.; Liu, Y.; Huang, S.; Qiao, W.; Chen, J.; Guo, T.; Zhang, X.; Guo, S.; Zhang, X.; Qi, G. Successive walnut plantations alter soil carbon quantity and quality by modifying microbial communities and enzyme activities. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arafat, Y.; Tayyab, M.; Khan, M.U.; Chen, T.; Lin, S. Long-Term Monoculture Negatively Regulates Fungal Community Composition and Abundance of Tea Orchards. Agronomy 2019, 9, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).