Submitted:

13 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Moving Beyond the JCQ and Demand/Control Model

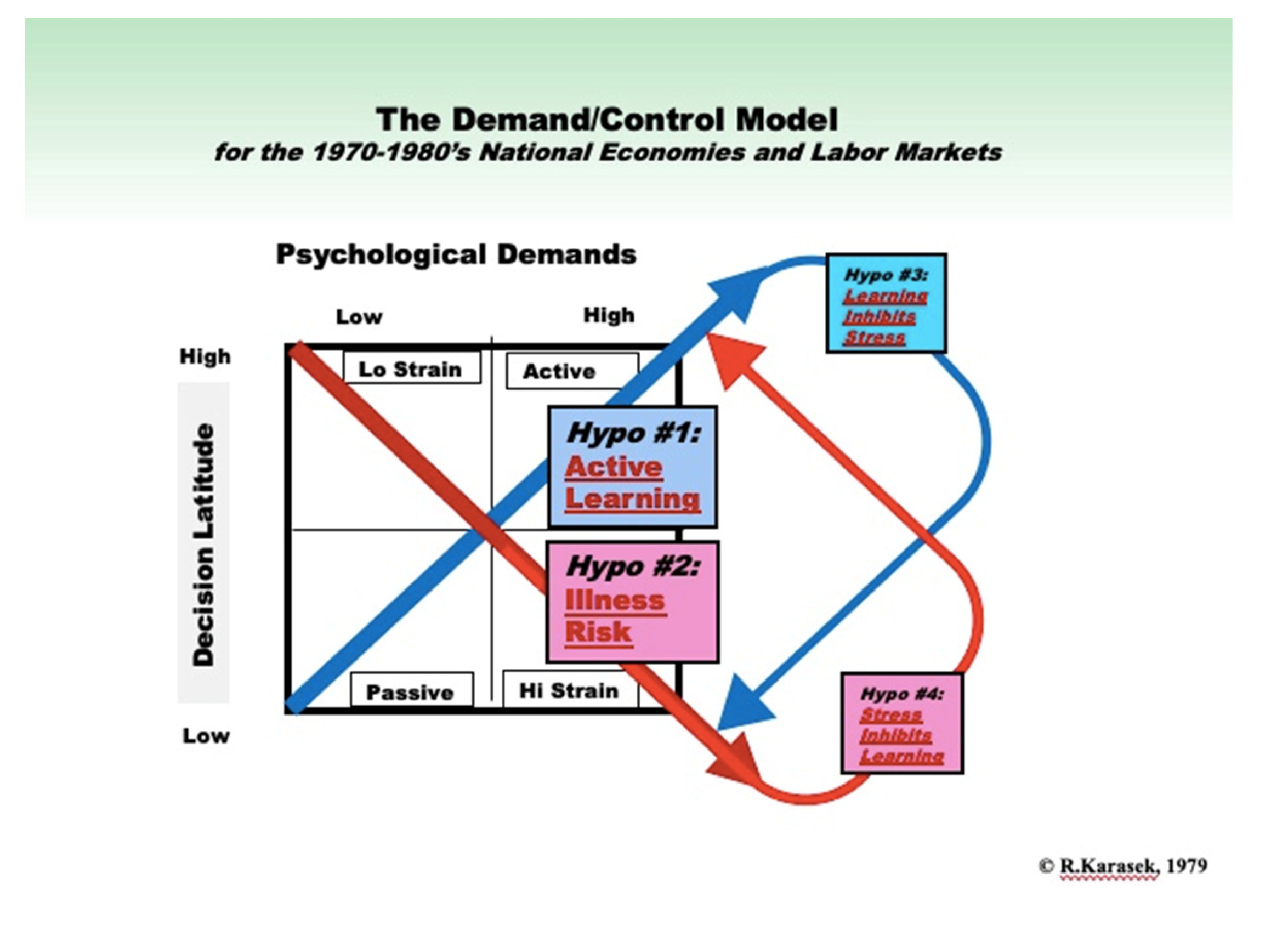

1.1. Brief Review of the Demand/Control Model

1.2. Moving Beyond the Classic D/C Model’s Task Level

1.2.1. Status of the D/C Model—Today

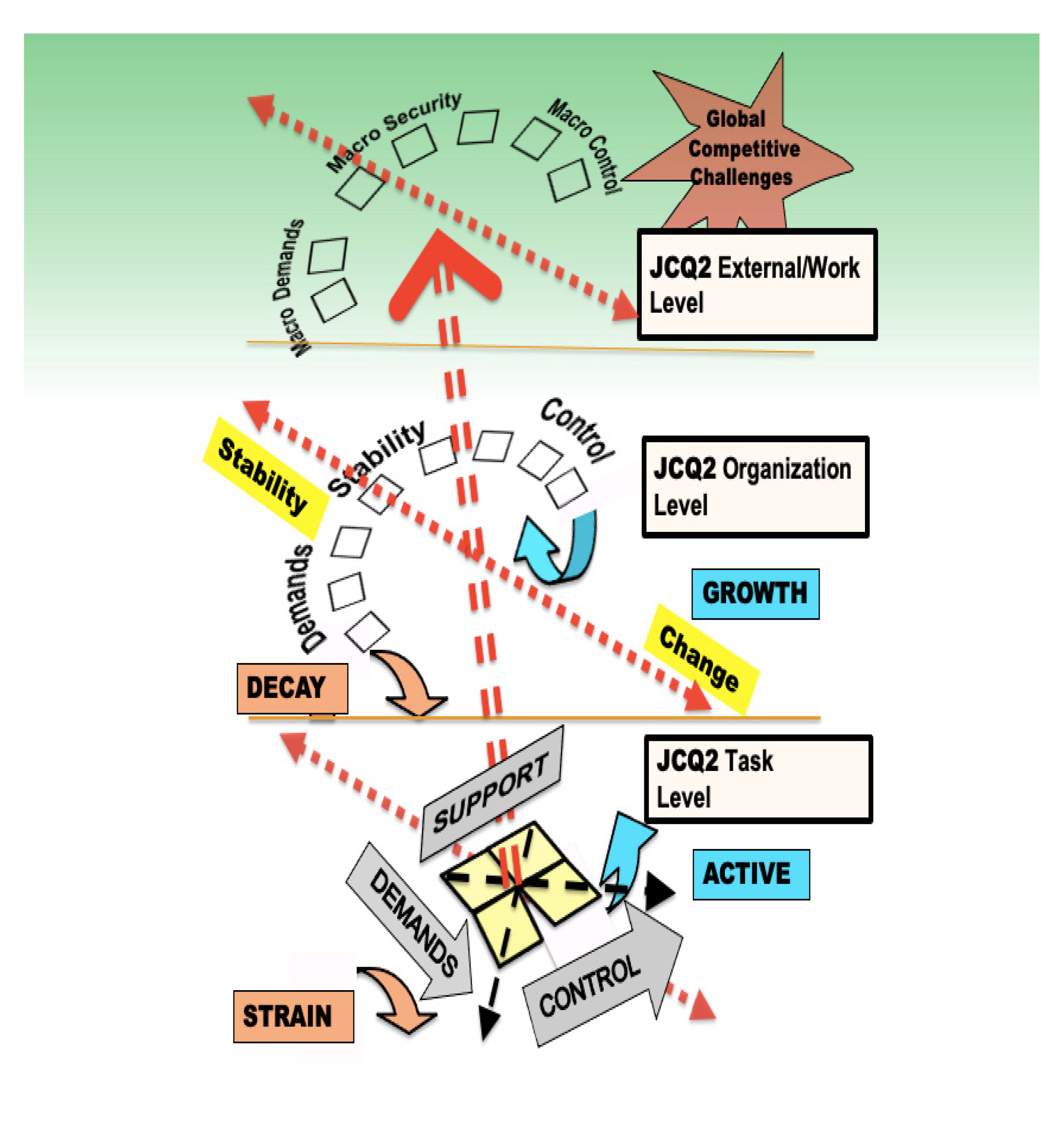

1.2.2. Evolution of the Theoretical Model for the JCQ2: From D/C to A/D/C

1.2.3. JCQ2 Practical Criteria

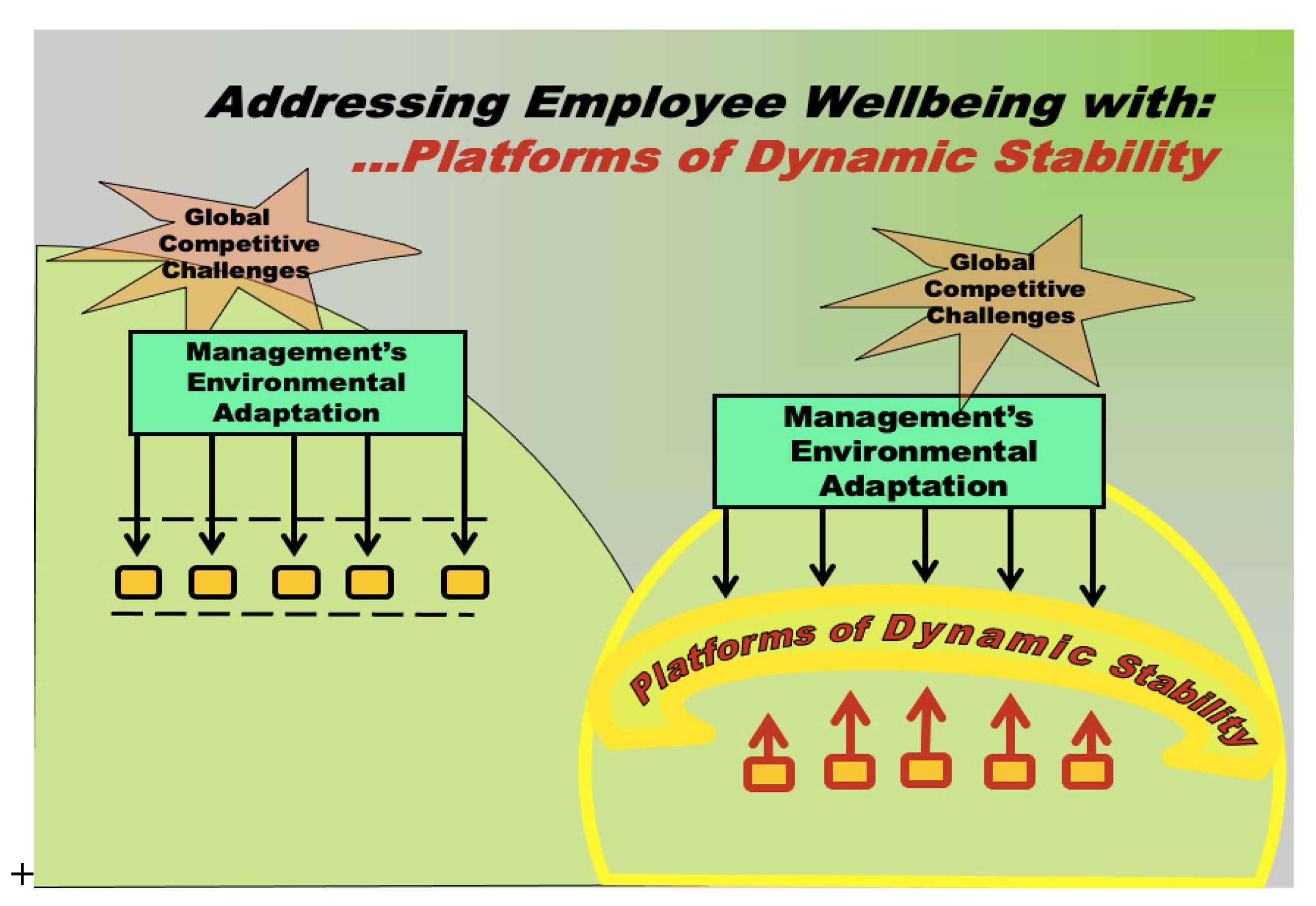

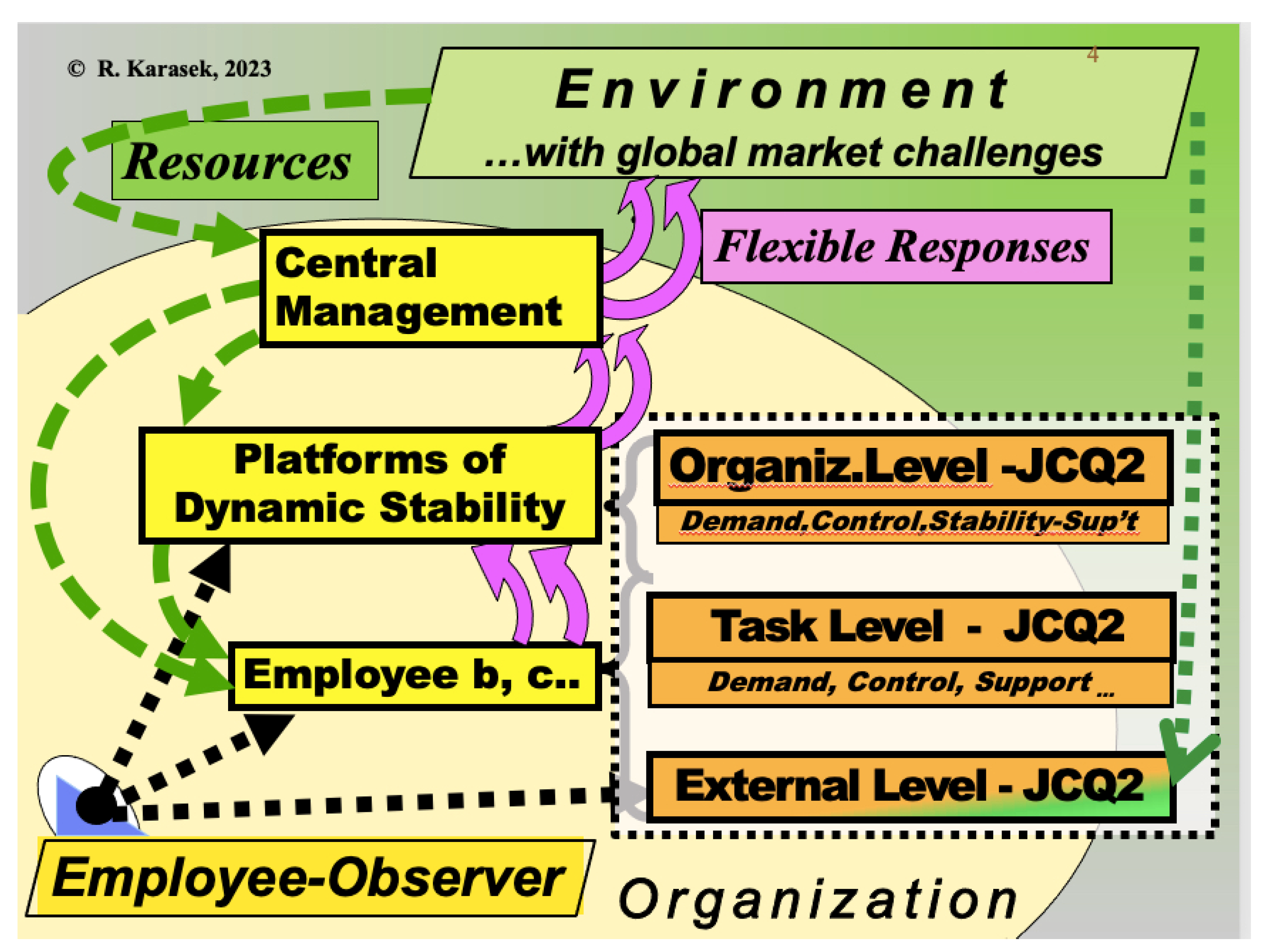

1.3. Transdisciplinary Theoretic Base Across Multiple-Levels: A Spine and Limbs Intellectual Bridge to Bring Active Health Promotion Agency

1.3.1. A Seamless, Upward Pathway for Workplace Health Promotion

1.3.2. Flipping a Systems-Theory Hierarchy—To Put the Human Being on Top

1.3.3. Developing a Multi-Level Intellectual Bridge Concept for Both Promotion and Sustainability

- In Section 2 below our first stage of integration – at the micro-level, is anchored in psychology and focuses on individual motivations. It defines conducivity’s collaborative self-actualizing behavior using motivation theory and group dynamic theory to articulate micro-level boundary-spanning social behavior relating to both disease-preventing growth and disease-related decay.

- In Section 3 and Section 4 the workplace organization’s internal functions will be linked - via system theory propositions – to research in organizational sociology and psychology to support both our selection of JCQ2 scales at the organization level and Bottom-up workplace redesign processes. The new JCQ2 organization level scales specifically address the costs and difficulties, as well as the unexpectedly large bonuses associated the processes involved in health promotion. This is the most challenging set of system science/social science theory relations, but it underpins the largest number of JCQ2 scales for multi-level D/C/S-S model’s characteristic workplace predictions – in Section 5. It then further provides a platform for the External-To-Work scales in a forthcoming paper in this issue.

- Finally, in a separate paper in this Special Issue which focuses on macro-level themes, a further extrapolation of the “intellectual bridge” utilizes the JCQ2’s conducive behavior task and organization scales in relation to economics and political theory. That paper attempts to explain how JCQ2 usage could monitor global progress in major current social issue areas such as climate sustainability and Western democratic societal stability, as well as psychosocial workplace health. In our ever-more constantly integrated, multibillion person world, many populations, and economists 13, are looking for precisely such “next steps forward” in societal development. Examples of forward-looking search process include Lerouge and Karasek’s conference on a New Economy of Innovative and Healthy Work [52] and a major European Union “Beyond-Growth” Conference [53].

2. The New Individual Level: Extending the JCQ2-ADC Theory Platform at: Assessment of Growth and Decay/Disease

2.1. GROWTH: Active Work for Wellbeing Promotion, Conducive Behavior and Collaborative Self-Actualization

2.2. DECAY/DISEASE: Work Stress-Related Health Risks

3. Organization Level: JCQ2 Workplace Assessment: Evolving an Extended Theory Base

3.1. JCQ2 Solutions to Multi-Level Workplace Context Challenges: Mid-Level Core Concepts Using a Multi-Level Systems Theory Base

3.2. Mid-Level Core Concepts (Stage 1—Method Evolution)

3.3. Newly Generalized D/C/S-S Dimensions (Stage 2—Method Evolution)

3.4. Extension of the ADC with “Spine and Limbs” Concepts to Explain Bottom-Up Workplace Participation: A Grounded Speculation: (Stage 3—Method Evolution)

4. Translation of Theory to JCQ2 Multi-Level Organizational Hypotheses: Platforms of Dynamic Stability

4.1. JCQ2 Multi-Level Organizational Hypotheses: Platforms of Dynamic Stability

4.2. An Organizational Management/Leadership View

4.3. A Worker’s Shop Floor View

4.4. Dynamic Adaptation and Stability Support Processes in Mid-Level Organizational Function

4.5. Nine Requirements for Developing Platforms of Dynamic Stability: Two Characteristics, Four Preconditions, Two Pitfalls, and a Possibility

4.5.1. Characteristic #1. Extensive Feasibility of Direct Democratic Development

4.5.2. Characteristics #2. Flexibility of Social Integration

4.5.3. Precondition #3. Surplus for Mid-Level Platform of Dynamic Stability

4.5.4. Precondition #4. Competencies, Diversity and Division of Labor

4.5.5. Precondition #5. “Rules” of Work Process and JCQ2 Scales

4.5.6. Precondition #6, A Development Pathway Meta-Narrative (A Social Organizational “DNA”)

4.5.7. Pitfalls #7 and #8: Failures and Demands

4.5.8. Possibility # 9: Growth Towards a New Level of Functionality

4.6. Healthy Work Redesign Process Literature on Platforms of Dynamic Stability and Participative Democracy

5. Definition of JCQ2 Scales from Multi-Level Demand, Control and Support-Stability Concepts and Literature

5.1. Introduction: D/C/S-S Framework as an Empirically Valid Scale Structure

5.2. A Review of the JCQ2 Developmental Process

5.3. Review of JCQ2 Scales in D/C/S-S Areas

5.3.1. JCQ2 Demand Concept and Scales

5.3.2. JCQ2 Control Concept and Scales

5.3.3. JCQ 2.0 Social Stability/Support Concept and Scales

5.3.4. JCQ 2.0 External-To-Work Scales: Effects from Beyond the Organization

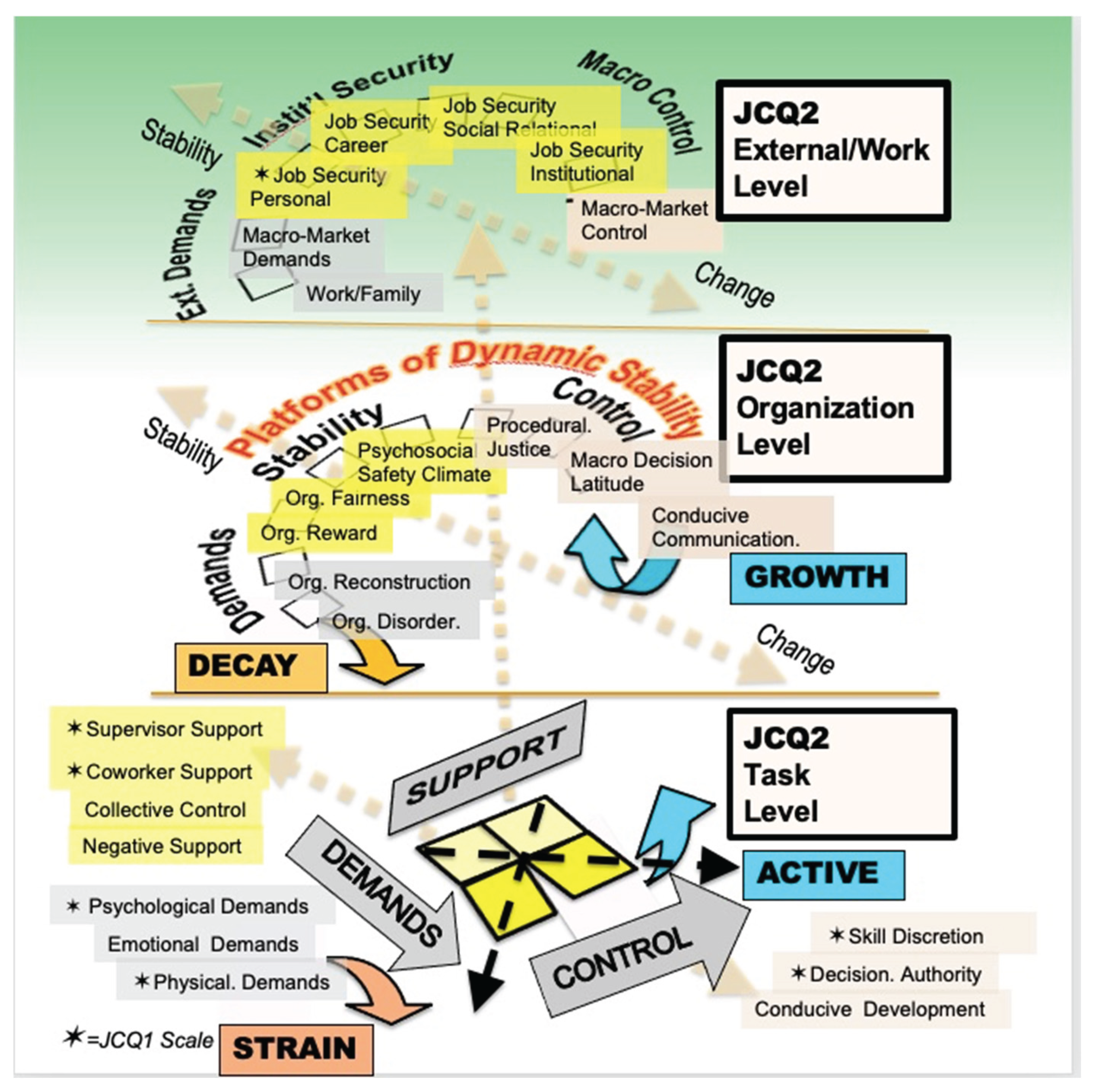

5.4. Visualization of JCQ2 Organization-Level Scales

5.5. Overview of Scale Evolution from JCQ1 to JCQ2

5.6. Simplifying the Empirical Validations of the JCQ2

6. Discussion

6.1. Discussion

6.2. JCQ2 Practical Guidelines and Validation

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Karasek, R. , The Associationalist Demand–Control (ADC) Theory: Toward a Sustainable Psychosocial Work Environment, in Handbook of Socioeconomic Determinants of Occupational Health: From Macro-level to Micro-level Evidence, T. Theorell, Editor. 2021, Springer. p. 573-610.

- Niedhammer, I. , et al., Psychometric properties of the French version of Karasek's "Job Content Questionnaire" and its scales measuring psychological pressures, decisional latitude and social support: the results of the SUMER. 2006, Sante Publique (Vandoeuvre-les-Nancy.

- Karasek, R. and T. Theorell, Healthy work: Stress, productivity and the reconstruction of working life. 1990: Basic Books, Hachette.

- Brisson, C. , et al., Reliability and validity of the French version of the 18-item Karasek job content questionnaire. Work & Stress 1998, 12, 322–326. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, T.M. and R. Karasek, Validity and reliability of the job content questionnaire in formal and informal jobs in Brazil. Scandinavian Journal of Work Environment and Health 2008, Supplement 6, 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami, N. , et al., Assessment of job stress dimensions based on the job de-mands-control model of employees of telecommunication and electric power companies in Japan: Reliability and validi-ty of the Japanese version of job content questionnaire. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 1995, 2, 358–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y., W. M. Luh, and Y.L. Guo, Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Job Content Questionnaire in Taiwanese workers. Int J Behav Med 2003, 10, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phakthongsuk, P. and N. Apakupakul, Psychometric properties of the Thai version of the 22-item and 45-item Karasek job content questionnaire. Int J Occup Med Environ Health 2008, 21, 10–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagheri Hossein Abadi, M. , et al., Social Support, and Depression in Iranian Nurses. Journal of Nurs-ing Re-search.

- Eum KD, et al. , Psychometric properties of the Korean version of the job content questionnaire: data from health care workers.. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2007, 80, 497–504. [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, N. , et al., Validation of the Job Content Questionnaire among hospital nurses in Vietnam. Journal of Occupational Health 2020. 62(ue 1): p. 12086,‐12086.

- Karasek, R. , The impact of the work environment on life outside the job., in Dept of Sociology and Labor Relations. 1976, Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Boston. p. 349.

- Karasek, R. , Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly 1979, 24, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. , Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, T.H. and R.H. Rahe, The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 1967, 11, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, A.M. and S.K. Parker, Redesigning work design theories: The rise of relational and proactive perspectives. Academy of Management Annals 2009, 3, 317–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taris, T.W. and J.A. Feij, Learning and strain among newcomers: A three-wave study on the effects of job demands and job control. The Journal of psychology 2004, 138, 543–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, E. , et al., The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A., M. Van Veldhoven, and D. Xanthopoulou, Beyond the Demand-Control Model: Thriving on High Job Demands and Resources. Journal of Personnel Psychology 2010, 9, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollard, M.F. and A.B. Bakker, Psychosocial safety climate as a precursor to conducive work environments, psychological health problems, and employee engagement. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 2010, 83, 579–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czikszentmihalyi, M. , Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. 1990, New York: Harper & Row.

- Gonzalez-Mulé, E. and B. Cockburn, Worked to death: The relationships of job demands and job control with mortality. Personnel Psychology 2017, 70, 73–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R. , Job socialization: The carry-over effects of work on political and leisure activities. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 2004, 24, 284–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, C. , et al., The influence of active jobs in midlife on leisure activity in old age. Part 4 in: Nilsen C Do psychosocial working conditions contribute to healthy and active aging? Studies of mortality, late-life health and leisure.. 2017, Karolinska Institute: Solna, Sweden.

- Hovbrandt, P. , et al., Psychosocial Working Conditions and Social Participation. A 10-Year Follow-Up of Senior Workers. IJERPH.

- Dollard, M.F. and A.H. Winefield, A test of the demand–control/support model of work stress in correctional officers. Journal of occupational health psychology 1998, 3, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taris, T.W. , et al., Learning new behaviour patterns: A longitudinal test of Karasek's active learning hypothesis among Dutch teachers. Work & Stress 2003, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, S. , Van den Broeck, A., Holman, D., Work Design Influences: a Synthesis of Multilevel Factors that affect the Design of Jobs. Academy of Management Annals 2017, 11, 267–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, U. , Frankenhaeuser, M., Pituitary-adrenal and sympathetic-adrenal correlates of distress and effort. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 1980. 24(3‐4): p. 125‐130.

- Karasek, R. , Baker, D., Marxer, F., Ahlbom, A., Theorell,T., Job Decision Latitude, Job Demands, and Cardiovascular Disease: A Prospective Study of Swedish Men. Am J Public Health 1981, 71, 694–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J. and E. Hall, Job Strain, Work Place Social Support, and Cardiovascular Dsease: A Cross-Sectional Study of a Random Sample of the Swedish Working Population. American Journal of Public Health 1988, 78, 1336–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uehata, T. , Long working hours and occupational stress-related cardiovascular attacks among middle-aged workers in Japan. J Hum Ergo (Tokyo) 1991. 20, 147–153.

- Ke, D.-S. , Overwork, Stroke, and Karoshi-death from Overwork. Acta Neurol Taiwan 2012, 21, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Karasek, R. , The political implications of psychosocial work redesign: a model of the psychosocial class structure. International Journal of Health Services 1989, 19, 481–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasek, R. , An alternative economic vision for healthy work: Conducive economy. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 2004, 24, 397–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R. , The social behaviors in conducive production and exchange. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 2004, 24, 457–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R. , Low social control and physiological deregulation - the stress-disequilibrium theory, towards a new demand-control model. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health 2008, 6 (Suppl 2008), 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J.H. , Signals and boundaries: Building blocks for complex adaptive systems. 2012, Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Briggs, J. and F.D. Peat, Turbulent mirror: An illustrated guide to chaos theory and the science of wholeness. 1989: HarperCollins Publishers.

- Bertalanffy, L.v. , General system theory: Foundations, development, applications. 1968: G. Braziller.

- Luhmann, N., D. Baecker, and P. Gilgen, Introduction to systems theory. 2013: Polity Cambridge.

- Tooby, J., L. Cosmides, and H.C. Barrett, The second law of thermodynamics is the first law of psychology: evolutionary developmental psychology and the theory of tandem, coordinated inheritances: comment on Lickliter and Honeycutt Psychological Bulletin 2003. 129, 858–865.

- Daly, H.E. , Beyond growth: the economics of sustainable development. 2014: Beacon Press.

- Keshavarz Mohammadi N, et al., Exploring settings as social complex adaptive systems in setting-based health research: a scoping review. Health promotion international 2024. 39 (1): daae001.

- Buzsaki, G. , Rhythms of the Brain. 2006: Oxford university press.

- Copernicus, N. , De Revolutionibus Orbitum Coelestium 1543: Nuremberg Press.

- Rank, O. , Art and artist: Creative urge and personality development. 1932, New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Mazzucato, M. , The value of everything: Making and taking in the global economy. 2018: Hachette UK.

- Raworth, K. , Doughnut economics: seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. 2017: Chelsea Green Publishing.

- Piketty, T. , A brief history of equality. 2022: Harvard University Press.

- Fukuyama, F. , Liberalism and its Discontents. 2022: Profile Books.

- Lerouge, L. and R. Karasek. Towards a New Economy of Innovative and Healthy Work. in Towards a New Economy of Innovative and Healthy Work. 2016. Univ. of Bordeaux, France. keynote resources annotated: https://healthywork2016.sciencesconf.org/resource/page/id/6.

- European Union. Beyond Growth 2023 in Beyond Growth 2023. 2023. Brussels, Conference, May 15-17: European Union.

- Sen, A. , Commodities and Capabilities: Amartya Sen. 1999: Oxford University Press.

- White, R.W. , Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence. Psychological Review 1959, 66, 297–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scitovsky, T. , The joyless economy. 1976: Oxford University Press.

- Maslow, A.H. , A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review 1943, 50, 370–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. , A preface to motivation theory, Psychosomatic medicine 1943. 5, 85–92. [CrossRef]

- Maslow, A.H. , The instinctoid nature of basic needs. Journal of personality 1954.

- Gallie, D. , et al., The implications of direct participation for organisational commitment, job satisfaction and affective psychological well-being: a longitudinal analysis. Industrial Relations Journal 2017, 48, 174–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Hernández, P. , et al., Mindfulness and job control as moderators of the relationship between demands and innovative work behaviours. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones 2020, 36, 95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, P.E. , Role differentiation in small groups. American Sociological Review 1955, 20, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descartes, R. , Meditations on first philosophy: With selections from the objections and replies. 2008: Oxford University Press.

- Parsons, T. , The social system. 1951: The Free Press.

- Theorell, T. , et al., A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theorell, T. , et al., A systematic review of studies in the contributions of the work environment to ischaemic heart disease development. The European Journal of Public Health 2016, 26, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasek, R. , The Stress-Disequilibrium Theory of Chronis Disease Development: Low Social Control and Physiological De-regulation. 2005, University of Masachusetts Lowell. p. 1-38.

- Siegal, J. and M. Rogawski, A function for REM sleep: regulation of noradrnergc receptor activity. Brain Research 1988, 472(3), 213–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilankovic, N., A. Ilankovic, and V. Ilanvokic., New Hypothses and Theory and Functions of Sleep and Dreams. Macedonian Journal of Meducal Science 2014, 7, 78–82. [Google Scholar]

- Recordati, G. , A thermodynamic model of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. Autonomic Neuroscience 2003, 103, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buxton, R.B. , Recharging the brain’s batteries: a thermodynamic perspective on modeling brain energetics. Front Sci 2025, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huikuri, H. , Castellanos, A.,Myerburg, R.,, Sudden Death Due to Cardiac Arrythmias. New England Journal of Medicine 2001, 345. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, S.I. , Life as No One Knows It: The Physics of Life’s Emergence. 2015, New York.

- Theorell, T. and N. A., Cultural activity at work: reciprocal associations with depressive symptoms in employees. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2019, 92, 1131–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karasek, R. and S. Collins, P.O.T.D. - Social Prevention-Only Treatable Disease. 2014, University of Massachusetts Lowell: Lowell, Massachusetts, US. p. 50.

- New York Times Editorial Board, Protecting Competition is a Vital Goal, , 2023, in New York Times. 2023, New York Times: New York. p. 11. 26 August.

- Phillippon, T. , The Great Reversal. 2019.

- Standing, G. , The precariat: The new dangerous class. 2011: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Dhondt, S., F. D. Pot, and K.O. Kraan, The importance of organizational level decision latitude for well-being and organizational commitment. Team Performance Management 2014, 20, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderfeldt, B. , et al., Does organization matter? A multilevel analysis of the demand-control model applied to human services. Social science & medicine 1997, 44, 527–534. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.M. , et al., Schools that learn (updated and revised): A fifth discipline fieldbook for educators, parents, and everyone who cares about education. 2012: Currency.

- Frigon, A. and D.L. Rigby, Where do capabilities reside? Analysis of related technological diversification in multi-locational firms. Regional Studies 2022, 56, 2045–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D. and R.L. Kahn, The Social Psychology of Organizations. 2nd ed. 1978, New York: Wiley. 838.

- Weber, M. , Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology. Vol. 2. 1978: University of California press.

- Weber, M. , From Max Weber: essays in sociology. 2009, Routledge.

- Locke, J., Two Treatises of Government and A Letter Concerning Toleration (second treatise). 1690: Yale University Press.

- Karasek, R. and L. Lerouge, A New Economy of Innovative and Healthy Work-Keynote Resources Annotated. 2016, CNRS, U. Bordeaux: University of Bordeaux, France.

- Karasek, R. , Lower health risk with increased job control among white collar workers. Journal of Organizational Behavior 1990, 11, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achterbergh, J. and D. Vriens, Organizations: Social systems conducting experiments. 2nd Rev. ed. 2010: Springer.

- Sitter, L.U.D., J. F.D. Hertog, and B. Dankbaar, From complex organizations with simple jobs to simple organizations with complex jobs. Human relations 1997, 50, 497–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrodinger, E. , What is Life. 1943, New York.

- Ashby, R. , An introduction to cybernetics. 1956: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Prigogine, I. and G. Nicolis, Biological order, structure and instabilities1. Quarterly reviews of biophysics 1971, 4(2-3), 107-148.

- Pincus, S. , Approximate entropy as a measure of system complexity PNAS Proc Nat Acad Sci 1991. 88(March 1991), 2297–2301.

- Skinner, J.E. , Pratt, C.M., Vybiral,T., A reduction in the correlation dimension of heartbeat intervals precedes imminent ventricular fibrillation in human subjects. American Heart Journal 1993, 125, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prigogine, I. and I. Stengers, Order out of chaos: Man's new dialogue with nature. 1984: Bantam Books.

- Chomsky, N. , Syntactic Structures. 1957, The Hague: Mouton.

- Gustavsen, B. , Work Organization and ‘the Scandinavian Model'. Economic and Industrial Democracy 2007, 28, 650–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, H. , International law in cyberspace, in USCYBERCOM Inter-Agency Legal Conference 2012, Achived: Ft. Meade US.

- Hagedorn-Rasmussen, P., Robust organisationsforandring - design om implementering i orkanens øje, ed. P. Hagedorn-Rasmussen. 2016, Denmark: Samfundslitteratur (Danish).

- Lengnick-Hall, C.A. and T.E. Beck, Adaptive fit versus robust transformation: How organizations respond to environmental change. Journal of Management 2005, 31, 738–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E. and K.M. Sutcliffe, Managing the unexpected: Resilient performance in an age of uncertainty. 2007: Jossey-Bass.

- Taylor, C. , et al., Psychosocial Safety Climate as a Factor in Organisational Resilience: Implications for Worker Psychological Health, Resilience, and Engagement. Psychosocial Safety Climate 2019. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Orton, J.D. and K.E. Weick, Loosely coupled systems: A reconceptualization. Academy of Management Review 1995, 15, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittel, J. , New directions for relational coordination theory, in Oxford handbook of positive organizational scholarship, K.S. Cameron and G.M. Spreitzer, Editors. 2011, University Press: Oxford. p. 74–94.

- Hvid, H. and P. Hasle, Human development and working life. 2003, England: Ashgate Publishing.

- Cooley, M. , Architect or bee? 1980: Langley Technical Services Slough.

- Homans, G.C. , The Human Group. 2017: Routledge.

- Kauffman, S.A. , The origins of order: Self-organization and selection in evolution. 1993: Oxford University Press, USA.

- Karasek, R. , Tool for creating healthier workplaces: The conducivity process. Bulletin of Science, Technology and Society 2004, 24, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsrud, E. , Democracy at work—Norwegian experiences with non-bureaucratic forms of organization. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 1977. 13, 410–421.

- Fuller, L.L. , American Legal Philosophy at Mid-Century--A Review of Edwin W. Patterson's Jurisprudence, Men and Ideas of the Law. J. Legal Educ. 1953, 6, 457. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, L.L. , The morality of law. 1964.

- Agbenyikey, W. , et al., Empirical Validation and Value Added of the External-To-Work Scales of the Multilevel Job Content Questionnaire 2.0 (JCQ 2) International Journal of Environmental Reseach and Pubic Health, 2025.

- Demerouti, E. , Design your own job through job crafting. European Psychologist 2014, 19, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollard, M.F. and R.A. Karasek, Building psychosocial safety climate: Evaluation of a socially coordinated PAR risk management stress prevention study, in Contemporary occupational health psychology: Global perspectives on research and practice, J. Houdmont and S. Leka, Editors. 2010, Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK. p. 208–233.

- Hall, G.B., M. F. Dollard, and J. Coward, Psychosocial safety climate: Development of the PSC-12. International Journal of Stress Management 2010, 17, 353–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollard, M.F. and T. Bailey, Building psychosocial safety climate in turbulent times: The case of COVID-19. Journal of Applied Psychology 2021, 106, 951. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Loh, M. , et al., Associationalist Demand Control (ADC) Theory: The role of Psychosocial Safety Climate in the platform of dynamic stability in ICOH-WOPS-ASPA A. Nakata and A. Shimazu, Editors. 2023, ICOH-WOPS-ASPA Tokyo. p. 1.

- Abualoush, S. , et al., The effect of knowledge sharing on the relationship between empowerment, service innovative behavior and entrepreneurship. International Journal of Data and Network Science 2022, 6, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.B., R. F. Cook, and K.R. Pelletier, Toward an integrated framework for comprehensive organizational wellness: Concepts, practices, and research in workplace health promotion, in Handbook of occupational health psychology, J.C. Quick and L.E. Tetrick, Editors. 2003, American Psychological Association: Washington, DC. p. 69–95.

- Eisenberger, R. , et al., Perceived organizational support. Journal of Applied Psychology 1986, 71, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayrhofer, W. , Warning: Flexibility can damage your organizational health! Employee Relations 1997, 19, 519–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deneen, P.J. , Why liberalism failed. 2019: Yale University Press.

- Deneen, P. , Regime Change: Towards a Postliberal Future. 2023: Swift Press.

- Karasek, R. , Labor participation and job quality policy: Requirements for an alternative economic future. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health 1997, 23, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Choi, B. , et al., Socioeconomic status, job strain, and common mental disorders: an ecological (occupational) analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment and Health 2008, Supplement 6, 22–32.

- Hertel-Fernandez, A., T. Skocpol, and J. Sclar, When Political Mega-Donors Join Forces [to] Organize U.S. Politics on the Right and Left 2018 (?), Columbia University.

- Sperling, N. and B. Barnes, Reaction to Hamas Attack Leaves Some…Hollywood, an Ideological bubble.. a bastion of progressive politics..and liberal ideas..”, in Los Angeles Times. 2023: Los Angeles.

- Henley, J. , How Europe's far right is marching steadily into the mainstream, in Guardian. 2023: London.

- Luchman, J.N. and M.G. González-Morales, Demands, control, and support: A meta-analytic review of work characteristics interrelationships. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 2013, 18, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fila, M.J., J. Purl, and R.W. Griffeth, Job demands, control and support: Meta-analyzing moderator effects of gender, nationality, and occupation. Human Resource Management Review 2017, 27, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chungkham, H.S. , et al. , Factor structure and longitudinal measurement invariance of the demand control support model: an evidence from the Swedish Longitudinal Occupational Survey of Health (SLOSH). PLoS One 2013, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Agbenyikey, W., et al., Internationally Comparative Psychometrics and Internal Validity Assessment of the Multilevel Job Content Questionnaire 2.0 (JCQ 2) International Journal of Environmental Reseach and Pubic Health 2025,.

- Formazin, M., et al., The Structure of Demand, Control, and Support underlying the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ) 2.0. International Journal of Environmental Reseach and Pubic Health 2025,.

- Formazin, M., et al., International Empirical Validation and Value Added of the Multilevel Job Content Questionnaire 2.0 (JCQ 2). International Journal of Environmental Reseach and Pubic Health 2025,.

- Formazin, M., et al., The association of scales from the revised Job Content Questionnaire 2.0 (JCQ 2) with burnout and affective commitment among German employees. International Journal of Environmental Reseach and Pubic Health 2025,.

- Kristeva, G. , ZZZ- Future economic and employmnt Implications of AI. 2024, International Monetary Fund: Washington, D.C.

- Cazzaniga, M. , et al., AI Will Transform the Global Economy. Let’s Make Sure It Benefits Humanity Gen-AI: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Work, in Series: Staff Discussion Notes No. 2024/001. 2024, International Monetary Fund: Washington, D.C. p. 41.

- Goodman, E.P. and J. Trehu, Algorithmic Auditing: Chasing AI Accountability. Santa Clara High Technology Law Journal 2023, 39, 289. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C. and S.E. Jackson, The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of organizational behavior 1981, 2, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, T. , et al., The impact of restructuring on employee well-being: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Work & Stress 2016, 30, 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, M. , Organisational restructuring/downsizing, OHS regulation and worker health and wellbeing. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 2007, 30, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinlan, M., C. Mayhew, and P. Bohle, The global expansion of precarious employment, work disorganisation, and consequences for occupational health: A review of recent research. International Journal of Health Services 2001, 31, 335–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LePine, J.A., N. P. Podsakoff, and M.A. LePine, A meta-analytic test of the challenge stressor–hindrance stressor framework: An explanation for inconsistent relationships among stressors and performance. Academy of Management Journal 2005, 48, 764–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P., J. A. LePine, and M.A. LePine, Differential challenge stressor-hindrance stressor relationships with job attitudes, turnover intentions, turnover, and withdrawal behavior: a meta-analysis. Journal of applied psychology 2007, 92, 438–438. [Google Scholar]

- McPhee, R. and P. Zaug, The communicative constitution of organizations: A framework for exploration. Electronic Journal of Communication 2000, 10, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, L. and A. Nicotera, Building theories of organizations: The constititive role of communication. 2009: Routledge.

- Siegrist, J. , Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 1996, 1, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.V. , Collective control: Strategies for survival in the workplace, in The psychosocial work environment: Work organization, democratization and health, J.V. Johnson and G. Johansson, Editors. 1991, Baywood Publishing Company, Inc. p. 121–132.

- Clays, E. , et al. , Long-term changes in the perception of job characteristics: results from the Belstress II-study. Journal of occupational health 2006, 48, 339–346. [Google Scholar]

- Pelfrene, E. , et al., The job content questionnaire: methodological considerations and challenges for future research. Archives of Public Health 2003, 61, 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Clays, E. , et al., Job stress and depression symptoms in middle-aged workers—prospective results from the Belstress study. Scandinavian journal of work, environment & health, 2007, 252-259.

- Dextras-Gauthier, J., A. Marchand, and V. Haines, Organizational culture, work organization conditions, and mental health: A proposed integration. International Journal of Stress Management 2012, 19, 81–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, R.E. and J. Rohrbaugh, A spatial model of effectiveness criteria: Towards a competing values approach to organizational analysis. Management Science 1983, 29, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dollard, M.F. and D.Y. Neser, Worker Health is good for the economy: Union density and psychosocial safety climate as determinants of country differences in worker health and productivity in 31 European Countries. Social Science and Medicine 2013, 92, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houtman, I.L. , et al., Dutch monitor on stress and physical load: Risk factors, consequences, and preventive action. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 1998, 55, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iavicoli, S. , et al., Occupational health and safety policy and psychosocial risks in Europe: The role of stakeholders’ perceptions. Health Policy 2011, 101, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dollard, M., K. Osborne, and I. Manning, A macro-level shift in modelling work distress and morale. Journal of Organizational Behavior 2013, 34, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedorn-Rasmussen, P. , P-SWOT-et redskab til dialogisk udforskning. 2017.

- Karasek, R. , et al., The Job content questionnaire (JCQ): An instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 1998, 3, 322–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| 1 | Analyses in the JCQ2 Pilot studies in following papers confirms the empirically utility of the combination of skill discretion and decision authority, as does much other research. At the macro-level, the relationship between (a) skill and capability development contributions (from conducive behavior) and (b) the generalized control propositions used to evolve the Platforms of Dynamic Stability construct (Section 4) are further discussed in a forthcoming paper in this issue (Paper 8, on global risk monitoring). However, potentially significant occupational differences between these two constructs are discussed at the micro-level in [3] Karasek and Theorell , 1990 p. 58 -61). |

| 2 | Definitions: The generic social scientific terms such as “individual level,” “societal level” are descriptive of different human behavioral levels. Task level, Organization level, and External-To-Work level are this paper’s JCQ2 instrument scale level labels. |

| 3 | In fact the D/C model can be considered a precursor to the JD-R (see JDR model of Figure 1 from 2001 [18] is functionally analogous to Karasek’s 1976 dissertation figure (pps. 73[78], (also pps.66 -74)) [12] ((See Supplement, Fig 5-S)). |

| 4 | Examples include health and longevity [22], active leisure and political activity [23], post-retirement social engagement [24], and a longitudinal study of senior workers in Sweden [25]. |

| 5 | Bottom-up Note #1: Also simplistically: Demands can be related to classical physics’ First Law of Thermodynamics and Control related to the Second Law of Theormodynamics.. We do not emphasize this terminolgy in this social scicnce manuscript, but we nevertheless attempt to retain a number of core limitations and insights therefrom. |

| 6 | The D/C model’s original health research hypotheses which were consistent with psycho-endocrine response duality emerging in the then-current 1970-80’s Swedish physiological work stress and cardiovascular disease research (Lundberg and Frankenhaeuser in 1980, [29], Karasek, et al in 1981[30]). Even a 3-dimensional image of D/C/S work demands and cardiovascular disease emerged (Johnson and Hall in 1988 [31], (Uehata (1991)[32] and Ke (2012) [33]. |

| 7 | Task-level social support was already added as a “moderator” scale in the early 1980’s by Johnson and Hall, [31] and appears as a vertical precursor to multi-level analyses in Figure 2. |

| 8 |

Emergent properties is the CAS-system theory label for such for such across-level evolutions and potential feedback-related processes, as Cho discusses [44]. |

| 9 | To illustrate this point, consider the following extrapolation of systems theory as a thought experiment: the actions of a large and relentlessly efficient multilevel, hierarchically functioning system focused on attainment of a major global goal, positioned at the top of a globally integrated economy. It could command a cascading set of hierarchically controlling actions down to the level of “us” JCQ2 respondents - now assisted by inscrutable artificial intelligence-based communication, facial recognition programming, etc. - placing human beings as low level automatons in processes directed to only benefit organizations in top of the global economy. |

| 10 | We can try to differentiate the multi-level analytic model developed here from several other multi-level approaches which do not have direct human wellbeing as a driver: (a). An army at war; (b). System theory is used as a “humanely-focused” multi-level boundary spanning, theoretical perpective by van Bertalanffy [40], but as a natural scientist he uses only natural science examples without a human agency component (c). A partially analogous theoretical approach is used by Buzsaki [45] to describe the human brain as a multi-level complex structure with three major levels and integrated operation. He shows: (i) that multilevel modeling as needed to understand brain function, (ii) that each level must be understood in terms of its unique internal functional mechanisms (with evolutionarily recent mental function mainly built “on-top-of” more primitive structures); and (c) that empirical data is needed to validate the inter-level linkage hypotheses. The obvious major difference is that this JCQ2 paper integrates the multi-level behaviors of sentient human beings (who must be at the ”top-level”), while Buzsaki integrates ”bottom-level” neurons into complex overall brain operations. |

| 11 | Intellectually, Östergren has noted that this modification involves effectively undertaking a ”reverse Copernican flip” - for the multiple JCQ2-relevant levels of social behavior (for us as sentient Homo Sapiens sapiens). The astronomer [46] Copernicus in 1543 ushered in the primacy of the natural sciences in Western intellectual discourse by demonstrating that man was not at the center of the universe (with the earth instead revolvimg around the sun). Here we attempt a partial ”Copernican-reversal” by placing human wellbeing back into the center of our own global economic social order’s universe, with the assistance of several physical science-based logical propositions. |

| 12 | 500 years ago such thoughts were revolutionary in that these very words “molders and overcomers” [of their fate] from Pico dello Mirandola’s book “Oration of the Dignity of Man” in 1486 lead to the first Church of Rome printed book banning by Pope Innocent VIII in 1487. Thereafter, in Europe’s age of reformation and revolutions economic philosophers such as Locke, Ricardo and Smith evolved the modern market economy based on the individual’s material goods consumpion. In more modern times “molders and overcomers” [of their fate] are alluded to in a significanty different manner by psychoanalyst Otto Rank [47] . He introduces psychosocial innovations relevant for the JCQ2 which include: (a) the action learning principles that are reflected in platforms of Dynamic Stability in Section 4; and (b) the social relational motivational structure reflected in conducive behaviors in Section 2-1, where Rank’s object relations theory, relational therapy and gestalt therapy in psychoanalysis helped move the field of psychoanalysis beyond Freud’s originating biological drive-based conceptions. |

| 13 | Economists, especially in urbanized sections of advanced economies, are looking for new solutions ([48] Mazzucato, [49] Raworth, and [50] Piketty). Positive scenarios are being offered, and also with solutions requiring the appropriately equitable redistribution policies (such as recently discussed (2022) by inequality economist Thomas Piketty [50].The constructive search continues even in a world where great poverty and inequality are yielding the consequent marginalization which then supports simultaneously conflicting dialogues relating to regression to past social values [51] (see Fukuyama, 2022). We suggest -alternatively - focus on conducive behavior – as is discussed in the section below: the simplest forms of conducive behaviors are ubiquitous: they are core elements of the repertoire of basic of human social interactions, occurring for example in barter processes (see Figure 1 [36]) and can be the basis of future progress. |

| 14 | Several definitions of “surplus”and surplus value appear in this paper (full discussion of the topic is outside this paper’s boundaries). Our CSV discussion above focuses on analytic concepts and tools to assess the Non-Material components of value creation central to economic and social processes in 21st century developed societies. This first formulation of surplus value, Definition A, involves is very broad definition of surplus, but one that can stepwise evolve into a raison d’etre for collaborative work organization. Karasek [36] (see Supplement: Figure 2-S) four stages in the general presentation of conducive behavior, initially beginning in barter: an outside-company-boundary, producer/consumer social interaction. When conducive processes dynamically link employees to customers and move inside a company-boundary they give rise to Conducive Production (see Karasek 2004 [35], see Supplement: Figure 1-S), which is a dynamic sequence of value development in multiple market contexts. Such broad definitions of surplus, are also impled for (C) the ordering capacity creation discussion (Section 3-D), and (D) for the Platforms of Dynamic Stability discussion (Section 4-E-c). However, Definition A must be differentiated from a second Definition B: conventional business economics computations of profit computations for within company operations which are primarily material value computations and much more specifically defined, for example: direct market-measurable production costs, plus allocatable indirect costs. Obviously Definition A also differentiates CSV from the powerful Material Surplus Value discussion that Marx articulated for surplus value extracted by production process owners under 19th century capitalism’s legal systems, closely related to Definition B. |

| 15 | Powerful Artificial Intelligence (AI) computer-generated capabilities do not accrue to any living being (or to any member of a human society with distinctly-bounded membership and unique member personalities), and thus such capabilites become “person-less”- and useless to promote - or even validate - human social integration. The identity-hiddn impersonality of the communication fails to guarantee any equitable distribution of input or output resources to participants. Furthermore, the notable lack of equality between communicating parties - based on the huge economic resources AI needs to create its Large Language Model plaforms -is inconsistent with the reciprocal dynamic value generation process noted above. |

| 16 | As Slater has shown [62], individuals who are otherwise typically autonomously functioning and self-regulating need to differentiate themselves - demonstrating “who they are” - before they are willing to yield some of their autonomy to the collectivity’s rules and norms. |

| 17 | This definition of identity is a step beyond Descartes [63] 1643 formulation: “I think, therefore I am;“ and is distinct from Parson’s contemporary [64] demographic-based ascriptive status identity-based categories (age, gender, ethnicity, etc.). |

| 18 | A more complete discussion in Karasek, 2004, 2005, 2008 [37,67] , cites physiological evidence behind this ”high-level” theory of disease causation, based on a muti-level version of open systems theory (also recently updated [1]). Some similarities with the list of propositions there presented can be found in hypotheses relating to the function of REM sleep formulated by Siegal and Rogawski [68] and others [69]. Also, Recordati's [70] and Buxton [71] present a multi-level theory of a central nervous system based on thermodynamic propositions. |

| 19 | The ambitious claim is made in the Karasek’s SDT articles [37,67] that since there is is no low-level, single-system physiological failure explanation, there is likely to be a high level context explanation for their cause – and that high-level ordering capacity deficits - possibly only transitory - are indeed a consistent explanation of a escalating systemic deregulatory failure. Such failures can be often be evidence of a chronic disease. |

| 20 | Biologists and biophysicists [73] have recently turned greater attention to ”high-level,” healthy, regenerative (anabolic) processes - often with systems-theoretic implications, and which might be considered a physiological consequence of Active Work. For example, workplace cultural activty-based prevention programs have been demonstrated as health promoting [74]. This commentary is further extended in unpublished memos on Socially-focused Prevention-Only-Treatable-Disease [75] (S.P.-O.T.D) by Karasek and Collins. |

| 21 | Democrtic development - since Locke’s times in 1690’s England: at the beginnings of democratic governments - have always implied the need of an active ”mid-level” to protect citzens at the low level from excess domination by the highest level social forces. In Locke’s time that meant protection against the autocracy of the Devine Right of kings, via a mid-level which was then, and still is, our very contemporary ”representtve democracy” [86]). |

| 22 | Bottom-up Note #2: The very-generally applicable Second Law of Thermodynamics, which governs interrelationships between order and disorder and describes the limits on creating high-level complex systems (see Section 3-D and the sull set of Bottom-up Notes). |

| 23 | The origins of the more generalized ADC formulation can already be seen in the [13]1979 D/C model publication: “the individual’s job decision latitude [control] is the constraint which modulates the release or transformation of ‘stress’ (potential energy) into the energy of action,” which is an explanation with energy and order origins presented as a task design concept. |

| 24 | Bottom-up Note #3: Our term ordering capacity [37,67]) is what is often referred to in systems theory and thermodynamics references as Neg-Entropy. Ordering capacity represents the possibility of creating Work. Ordered Work is the very generalized definition of the coordination multiple channels of disorganized energy, with many degrees of freedom, into the constrained energy, with very few degrees of freedom – which can then be precisely commanded and controlled, Top-Down, for the Work’s energetic and precise actions to be taken. Work processes are defined when they as embodying information about exact times, places, persons, forces, etc.: bringing order out of chaos. Adopting Second Law language the creation of ordered work outcomes is labeled a ”Neg-Entropy Pump.[37,67] (Karasek, 2005, Figures 2 and 3; and Karasek, 2008, Figure 2; see also Supplement, Figure 4-S) , and going “up and down the neg-entropy hil Figure 3 [67]. Briggs and Peat popular-press’s book [39], with its dual thematic structure: from Order to Chaos and from Chaos to Order, was a partial inspiration of Karasek’s SDT model [37] ordering capacity creation hypotheses. This process is described by physicist Schrodinger [91] p. 26: we “extract ‘order’ from the envronment” [to undertake our life functions], and as a result“we give off heat.” |

| 25 | Bottom-up Note #4: Rhetorically the “daily life of the animal” is thus: it goes around and around constantly seaching to find food and shelter enough just to survive for another day – and then do the same again, and again, the next day (and also reproduces). Prigogine in 1978 won his Nobel prize for describing such order maintaining and order creating systems which he labeled: “disspative systems” because of the environmental energy they must constantly consume. They also demonstrate self-organizing, life-like behavior. |

| 26 | Bottom-up Note #5: This baseline is likely reflected related to the commonly used basal metabolic rate (BMR) in terms of human energy consumption. Separately, new basline levels of ordering capacity required for complex system functioning may also exist, for example the measurent methodologieas for Approximate Entopy [94]. Skinner [95] discusses to the nmber of independetly functiong reguatory sub-systems in an organism needed to maintain healthy stablity in constantly challenging environments. |

| 27 | Bottom-up Note #6; The concept of constraints to build up higher lervel order is discussed by Chomsky [97] in the context of human language development. |

| 28 | Bottom-up Note #7: The “precision” of the underlying building blocks reperesent themselves high level of order capacity and there construction itself required a major investment, all just to be able to create the foundation for the next higher level step. This higher level next step, while costly, will have the power and the capacity to produce outcome actions for the complex organization that are far higher in sophistation or breadth of imnpact then the lower- level itself could supply. Examples: (a): enzymes which can create important proteins in high volumes; (b): construction frameworks which shape and support new pouring concrete for a concrete bridge. |

| 29 | One progressive, work-organization example was the Swedish government’s LOM (Leadership, Organization, Management) umbrella program as organized by Gustavsen [98](1990_). in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s. |

| 30 | Koh, clarifies that in this US state department-archived memo. He was a Senior Advisor to the US Departemnt of State, and a legal historian. |

| 31 | Bottom-up Note #8:. Equilibrium of Flows terminology is used herein a new manner relevant for our ordering capacity discussion, but other forms of this general construct are a commonplace explanatory tool in almost every introductory economics textbook. Chapter 1 of such textbooks might show the two polarities of the modern free-market economy - with company on the one side with goods produced and wages paid; and the worker on the other side with labor applied and purchases made. These all flow in a continuous equilbrium of cycles which represent the economy’s life-blood circulation (albiet: for physical commodities). An elaborated further usage can be found in Figure 3 of Karasek, 2021 - which adds a parallel structure of two Conducive Value also with poles for companies and workers with flows in between them - and additionally also flows between the respective company and worker poles in the parallel commodity and conducive value “economies.” |

| 32 | See Definitions of Surplus p. 12 (footnote 14). |

| 33 | Returning to our system theory physical science base, we can note that a physical object’s movement “momentum” can also generate stability. For example, a bicycle provides the rider a stable platform while in rapid motion, when it is constantly guided towards an external goal. |

| 34 | Bottom-up Note #9. Prigogene has used non-linear forms of thermodynamics to formulate a theory of "self-organizing systems,” [93, 96] – implying opportunities to ”grow” exist everywhere for complex systems in the natural world: grass, flowers, and molds, etc. grow with internally (i.e.: self-determined) futures which adapt to environmental conditions. We contend that such growth also occurs naturally in complex social sysrems, which can only be “molded” into hierarchically-controlled behavior patterns through use of specifically structured external forces (constraints). Also Kauffman [109] has postulated that there are only two requirements for, i.e., the definition of, a living entity: (a) the ability to reproduce, and (b) the "ability to perform a thermodynamic work cycle". |

| 35 | The shop-level work redesign dialogues of the Conducivity Game in Karsek’s Nord Net project in Sweden [110] developed tools to specifically promote such structures. Less specifically focused contemporary examples include company “training workshops,” which often span worker and management representatives to foster multi-level communication. Major early examples were found in the national cross-level dialogues fundamental for the development and progress of the international Industrial Democracy movement in Sweden and Norway by Gustavsen in 1990 [98] and by Thorsrud in 1987 [111]. |

| 36 | See Definitions of Surplus, page 12, footnote 124 |

| 37 | Fuller’s list: comprehensibility; non-contradictory rules; rules consistent with power of actor; relative stability; transparency, non-retroactivity; consistency between announced and enforced rules. |

| 38 | Hertel-Fernandez, et al [128] document a duality/split in the ultra-wealthy political donor class in the US (circa 2016) which consistent with Karasek’s dual psychosocial class-structure predictions [34]. Hertel-Fernandez’s Figure 4 shows that Donor Consortia #1 as 46% of its sources of wealth from a “material/commodity-related”- industry base: mining, manufacturing, trade/distribution industries. By contrast Donor Consortia #2 has 50% of its contributions “non-material” wealth base: professional services, information, education/arts (such sources of wealth would beconsistnt with our conducive economy, discussed in Section 2-1). A smaller portion – about 35% - of wealth sources are common to both Donor Consortia: finance, insurance, real estate industries. |

| 39 |

[39] A new AI-based, monitoring question is added to psychologial demand scale for future use in an updated JCQ2 version: JCQ 2.01. Major, future AI effects on employment and economic inequality [138] are discussed by the Interntional Monetary fund[139]. |

| 40 | Supplemental exploratory findings using SEM modeling in the German Pilot data to test the closeness of association between scales are roughly consistent with this simple spiral picture. The organizational support scales Organizational Fairness and Psychosocial Safety Climate are quite highly correlated (.62). in a SEM model that includes Conducive Communication as an organizational control indicator. When Conducive Communication is combined together with Macro Decision Latitude and Procedural Justice this ordering produces the strongest SEM model. A less “good fit” occurs when grouping Conducive Communication with organizational support scales for fairnss and climate. A model using Procedural Justice as an organizational control indicator fits better than one using it as an organizational support indicator. On the organizational demands end of the “spiral,” the associations are somewhat less clear. The correlation between Organizational Restructuring and Organizational Disorder is only moderate at.35: (however, the Oganizational Restructuring scale has only one item in the German Pilot study). |

| 41 | In forthcoming papers in preparation for this special issue: 1. Internationally Comparative Psychometrics and Internal Validity Assessment, (Special Issue label Paper 2) [134] Agbenyikey, W. Li, J., Cho S-I., McLinton, S., Dollard, M., Formazin, M., Choi, BK. Houtmam, I., Karasek, R., (in submission for IJERPH, 2025), This paper selects internationally congruent and compact scale-question sets across four countries and tests their reliabilities. 2. The Structure of Demand, Control, and Support Underlying the JCQ 2.0; (Special Issue label Paper 3)[135], Formazin M, Choi B-K, Dollard M, Li J, Agbenyikey W, Cho S-I, Houtman I, Karasek, R;, This paper tests the validity of Composites scales for D/C/S-S dimensions to reduce the 18 detailed task and organization level detailed scales to three composites at each of two levels. (in submission for IJERPH, 2025), 3. JCQ2 Task and Organization-level Associations with Dependent Variables in Australia and Germany, (Special Issue label Paper 4 - in submission, for IJERPH, 2025), [136] Formazin, M., Dollard, M., Choi, BK., Li J., Agbenyikey, W., Cho, S-I., Houtman, I., Karasek, R.,. This paper presents findings based on the Composite Scales from the paper above. This allows reduction of the hypotheses tested to basic Job strain and Active work core predictions across two levels (based on the multi-level Spine and Limb dynamic relations presented in Section 1-C above), and further reduces the international testing scope to two non-Asian counties (Germany and Australia). 4. JCQ2 External-To-Work Scale Associations in Germany (Special Issue label Paper 5) [114] Agbenyikey W., Clays, E., Formazin, M., Karasek, R., (in preparation for IJERPH, 2025), This paper assess the JCQ2 added predictive value using the External-To-Work Scale level in D/C/S-S. 5. JCQ2 Detailed Task and Organizational Level Scale Associations with Burnout and Engagement in Germany (Special Issue label Paper 6)[137], Formazin, M., Martus, P., Burr, H., Pohrt, A., Choi, BK., Dollard, M., Karasek, R. (in publicationfor IJERPH, 2025). 6. JCQ2 Global Risk Monitoring – The JCQ2 monitoring goals briefly noted in Section 1-C above are adapted to address important social economic risks in the global economy (Special Issue label Paper 8; in preparation for IJERPH, 2025). |

| 42 | The JCQ Center, originally created at University of Massachusetts Lowell, has been transferred to the JCQ Center under Oresund Synergy ApS, Copenhagen, Denmark, operating not for profit. Instrument usage fees cover costs to maintain reliablity of the instrument standardization in an international context: including: usage review, administrative and distribution costs, and website-based communication. Usage permission for the JCQ2 and cost information can be obtained at (www.jcqcenter.org). |

| JCQ2 Scale Type and Origin(Footnote) | Recommended JCQ 2.0 Scales | Keywords |

|---|---|---|

|

JCQ 2.0/2.1 Scales – Task Level (modified JCQ 1.0 scales) | ||

| C-*r |

Skill Discretion*r, Decision Authority (when added=Decision Latitude JCQ1) |

learn new, creative, develop self /lot of say, own decisions, few decisions [R] |

| D-*r | Quantitative Psychological Demands*r | work fast, excessive, enough time[R], conflicting demands, easy[R],task monitoring -2.1 |

|

S-*r |

Supervisor Support*r, Coworker Support*r (when added=Social Support JCQ 1) |

supervisor: concerned, supportive, respectful / coworkers: friendly, supportive, respectful |

| --*r | Physical Demands*r | physical effort, heavy lift, body awkward |

|

JCQ 2.0 Scales -Task Level | ||

| D-L | Emotional Demands | demanding, suppression emotion |

| C-N |

Conducive Development |

skills w/o pressure, job motivates skills, decide development |

| S-L | Collective Control | coworker unity, coworkers pitch in-2.1, competition [R], distrust [R] , |

| S-N | Negative Social Support | harassments, isolation |

|

JCQ 2.0 Scales- Organizational Level | ||

| C-N |

Conducive Communication |

customer feedback, fit customer needs, upskilling supported, person-to-person -2.1, [others help my skill - 2.1], [I help others´ skills - 2.1 |

| C-N | Organizational Decision Latitude | influence, parties represented, informed |

|

C-L |

Procedural Justice | hear all concerns, information accuracy, can disagree, |

|

S-L |

Organizational Rewards | salary adequate, appreciation adequate |

| S-N |

Organizational Fairness |

re-organization benefits, re-organization manageable |

| S-L |

Psychosocial Safety Climate |

active stress prevention policy, consultation all parties, listened to, psychological well-being equal priority |

|

D-N |

Organizational Restructuring | cost cutting, management turnover |

|

D-N |

Organizational Disorder | work process, planning, poor tasks, organizational goals |

|

JCQ 2.0 / 2.1 Scales – External-to-work Level | ||

| D/S- r* | Job Insecurity-Person (~ JCQ1) | lose job, security [R], life decisions, |

| D/S-N | Job Insecurity-Career | career prospects [R], skills valuable [R], no change opportunities |

| D/S-N | Job Insecurity-Social Relation | use work social relations, use friends, use family |

|

D/S-N |

Job Insecurity-Institutional Support | government resources [R], job search help [R] |

|

D-N |

Macro/Global Economic Demands/Insecurity | global economy affects demands, affects insecurity, [company experiences pressures -2.1] |

|

C-N |

Macro/Labour Market Control |

global economy affects work influence [R], labour market control perception |

|

D-L |

Work/Family Boundary | work interferes family energy, plans amily interferes with work -2.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).