Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Small Object Detection

2.2. SAR Object Detection

2.3. Deformable and Grouped Convolutions

2.4. Texture Descriptors and Oriented Bounding Boxes

3. Methods

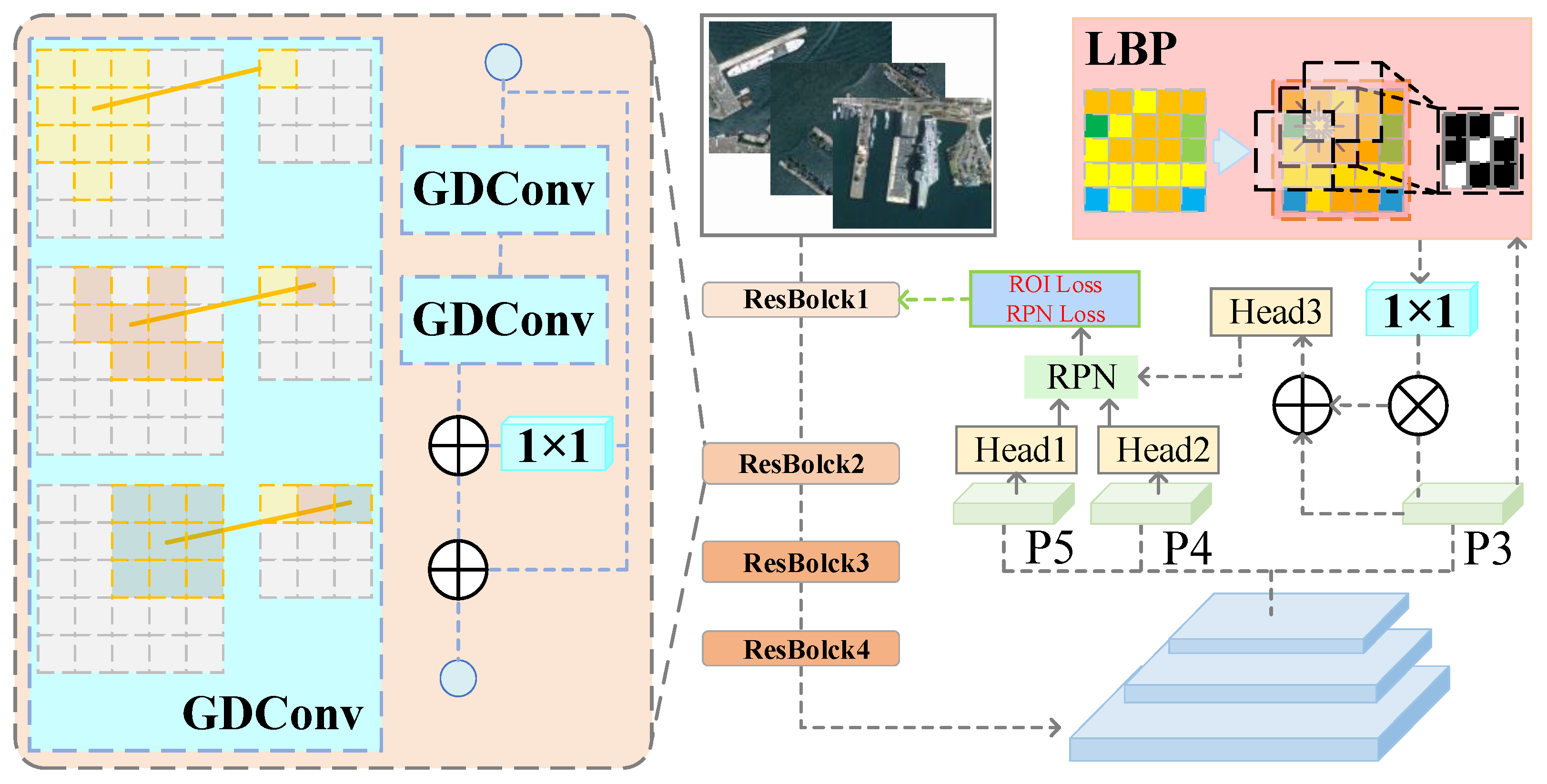

3.1. Overall Framework

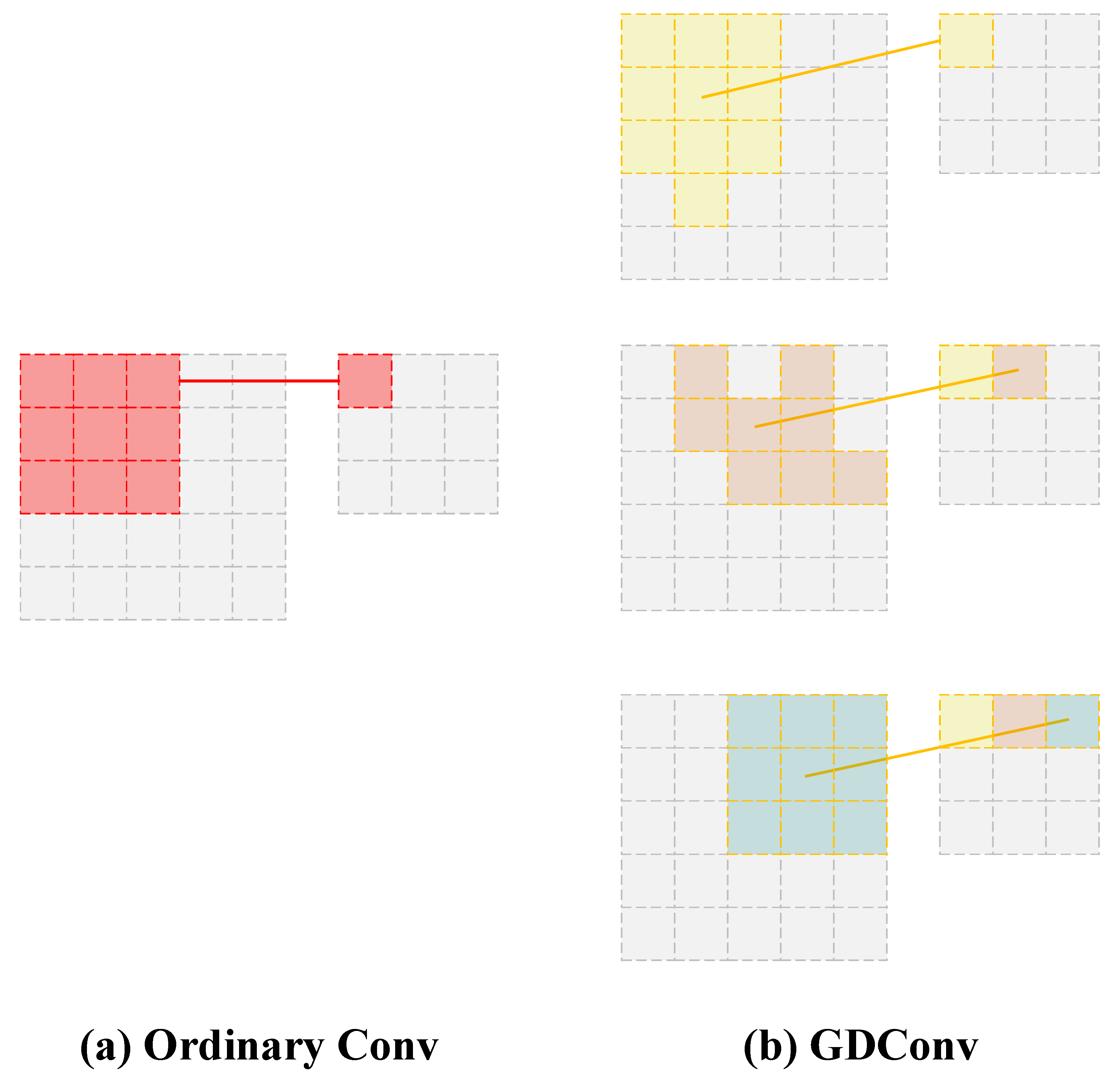

3.2. Grouped Deformable Convolution (GDConv)

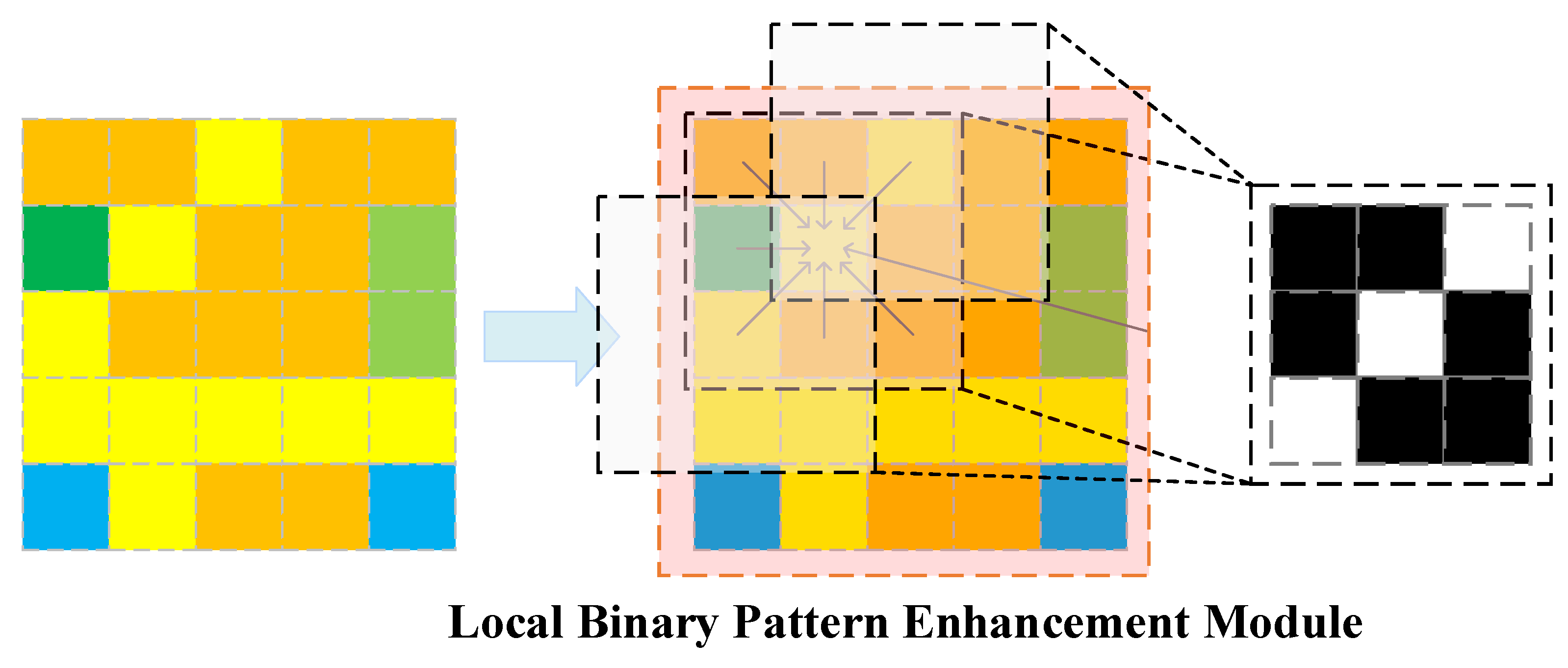

3.3. LBP Enhancement Module

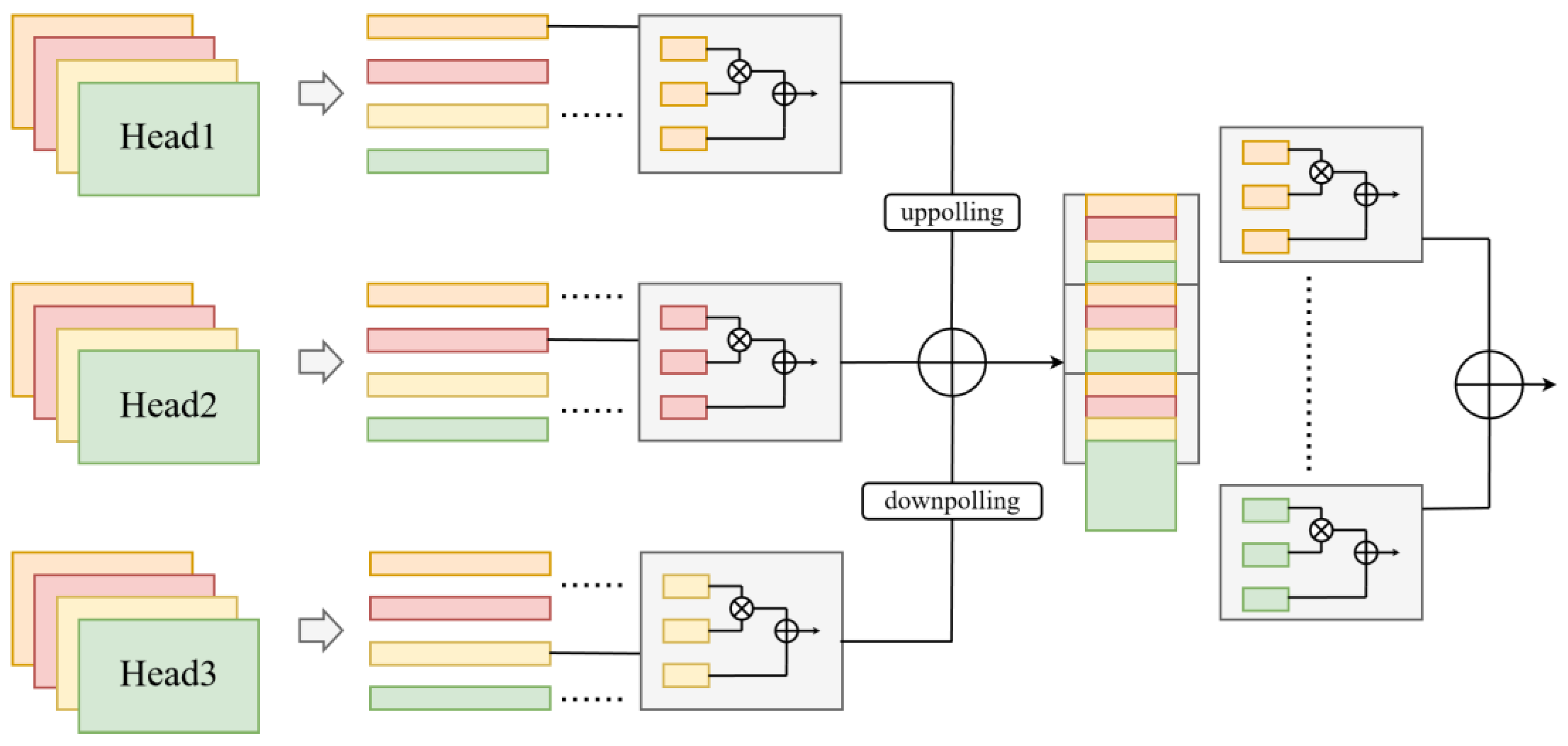

3.4. Vector Decomposition Module for Bounding Boxes

3.5. Loss Function

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets and Implementation

4.2. Comparative Experiment

4.3. Ablation Experiment

5. Conclusions

References

- R. Girshick, J. R. Girshick, J. Donahue, T. Darrell, and J. Malik, "Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation," in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 580-587, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Ren, K. S. Ren, K. He, R. Girshick, and J. Sun, "Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks," Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 28, 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. Redmon, S. J. Redmon, S. Divvala, R. Girshick, and A. Farhadi, "You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection," in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 779-788, 2016. [CrossRef]

- B. Wu, J. B. Wu, J. Huang, and Q. Duan, "Real-time Intelligent Healthcare Enabled by Federated Digital Twins with AoI Optimization," IEEE Network, pp. 1-1, 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Wu, Z. B. Wu, Z. Cai, W. Wu, and X. Yin, "AoI-aware resource management for smart health via deep reinforcement learning," IEEE Access, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T.-Y. Lin, P. T.-Y. Lin, P. Dollar, R. Girshick, K. He, B. Hariharan, and S. Belongie, "Feature pyramid networks for object detection," in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 2117-2125, 2017.

- J. Ding, N. J. Ding, N. Xue, Y. Long, G.-S. Xia, and Q. Lu, "Learning roi transformer for oriented object detection in aerial images," in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 2849-2858, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Huang, B. J. Huang, B. Wu, Q. Duan, L. Dong, and S. Yu, "A Fast UAV Trajectory Planning Framework in RIS-assisted Communication Systems with Accelerated Learning via Multithreading and Federating," IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, pp. 1-16, 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Yang, J. X. Yang, J. Yang, J. Yan, Y. Zhang, T. Zhang, Z. Guo, X. Sun, and K. Fu, "Scrdet: Towards more robust detection for small, cluttered and rotated objects," in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 8232-8241, 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Liang, M. D. Liang, M. Hashimoto, K. Iwata, X. Zhao, et al., "Co-occurrence probability-based pixel pairs background model for robust object detection in dynamic scenes," Pattern Recognition, vol. 48, no. 4, pp. 1374-1390, 2015. [CrossRef]

- B. Wu, J. B. Wu, J. Huang, and Q. Duan, "FedTD3: An Accelerated Learning Approach for UAV Trajectory Planning," in International Conference on Wireless Artificial Intelligent Computing Systems and Applications (WASA), pp. 13-24, Springer, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Z. Fang, S. Z. Fang, S. Hu, J. Wang, Y. Deng, X. Chen, and Y. Fang, "Prioritized Information Bottleneck Theoretic Framework With Distributed Online Learning for Edge Video Analytics," IEEE Transactions on Networking, pp. 1-17, 2025. [CrossRef]

- B. Wu and W. Wu, "Model-Free Cooperative Optimal Output Regulation for Linear Discrete-Time Multi-Agent Systems Using Reinforcement Learning," Mathematical Problems in Engineering, vol. 2023, no. 1, p. 6350647, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Li, J. H. Li, J. Chen, A. Zheng, Y. Wu, and Y. Luo, "Day-night cross-domain vehicle re-identification," in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 12626-12635, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T.-Y. Lin, P. T.-Y. Lin, P. Dollar, R. Girshick, K. He, B. Hariharan, and S. Belongie, "Feature pyramid networks for object detection," in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 2117-2125, 2017.

- D. Pan, B.-N. D. Pan, B.-N. Wu, Y.-L. Sun, and Y.-P. Xu, "A fault-tolerant and energy-efficient design of a network switch based on a quantum-based nano-communication technique," Sustainable Computing: Informatics and Systems, vol. 37, p. 100827, 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Wu, J. B. Wu, J. Huang, Q. Duan, L. Dong, and Z. A: Cai, "Enhancing vehicular platooning with wireless federated learning; arXiv:2507.00856. [CrossRef]

- J. Dai, H. J. Dai, H. Qi, Y. Xiong, Y. Li, G. Zhang, H. Hu, and Y. Wei, "Deformable convolutional networks," in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 764-773, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Xie, R. S. Xie, R. Girshick, P. Dollar, Z. Tu, and K. He, "Aggregated residual transformations for deep neural networks," in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 1492-1500, 2017. [CrossRef]

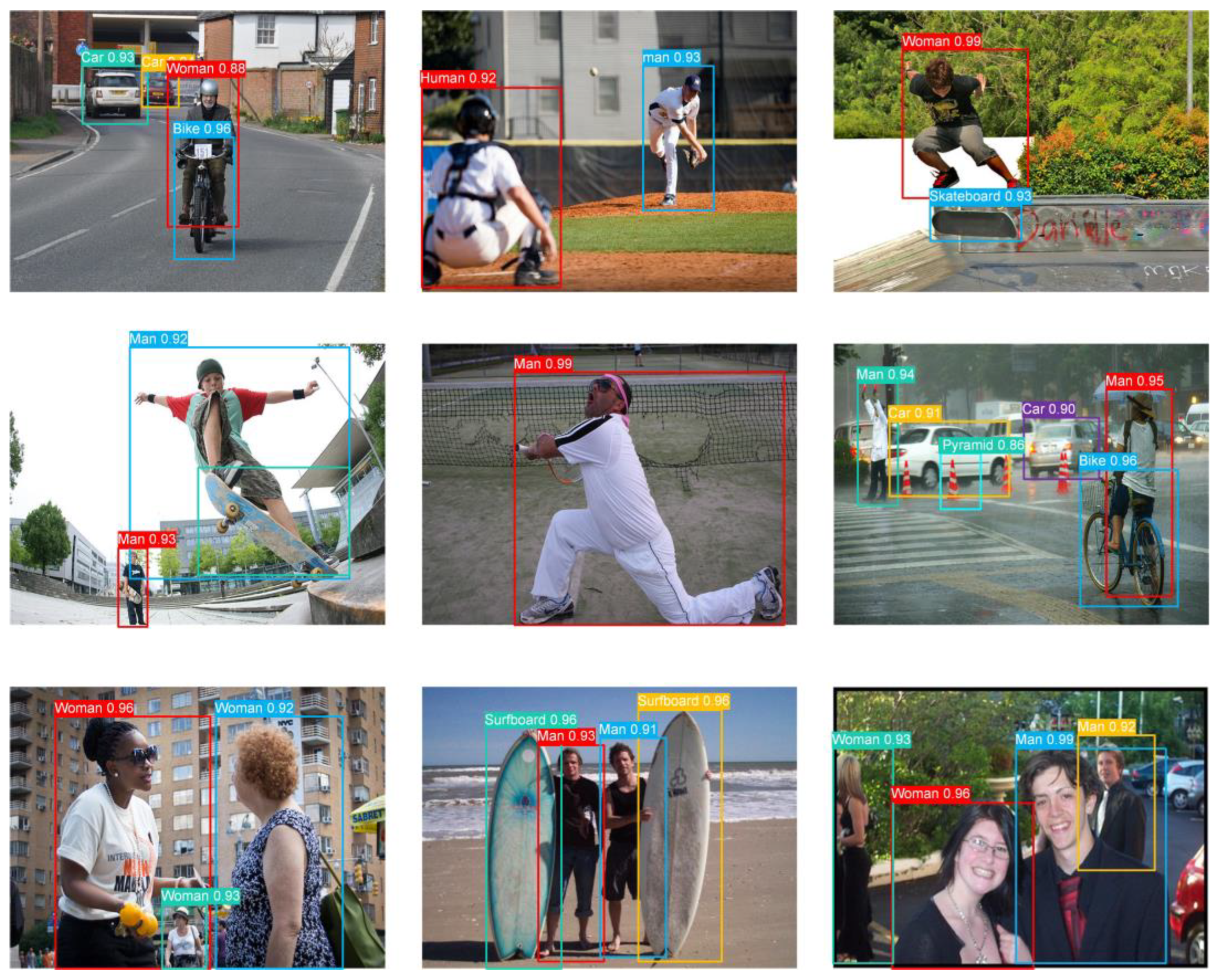

- M. Everingham, L. M. Everingham, L. Van Gool, C. K. Williams, J. Winn, and A. Zisserman, "The pascal visual object classes (voc) challenge," International Journal of Computer Vision, vol. 88, pp. 303-338, 2010. [CrossRef]

- T.-Y. Lin, M. T.-Y. Lin, M. Maire, S. Belongie, J. Hays, P. Perona, D. Ramanan, P. Dollar, and C. L. Zitnick, "Microsoft coco: Common objects in context," in *Computer Vision–ECCV 2014: 13th European Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, -12, 2014, Proceedings, Part V 13*, pp. 740-755, Springer, 2014. 6 September. [CrossRef]

- Russakovsky, J.A. Deng, H. Su, J. Krause, S. Satheesh, S. Ma, Z. Huang, A. Karpathy, A. Khosla, M. Bernstein, et al., "Imagenet large scale visual recognition challenge," International Journal of Computer Vision, vol. 115, pp. 211-252, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, P. Y. Liu, P. Sun, N. Wergeles, and Y. Shang, "A survey and performance evaluation of deep learning methods for small object detection," Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 172, p. 114602, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Cheng, X. G. Cheng, X. Yuan, X. Yao, K. Yan, Q. Zeng, X. Xie, and J. Han, "Towards large-scale small object detection: Survey and benchmarks," IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol. 45, no. 11, pp. 13467-13488, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Ozge Unel, B. O. F. Ozge Unel, B. O. Ozkalayci, and C. Cigla, "The power of tiling for small object detection," in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, pp. 0-0, 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Chen, M.-Y. C. Chen, M.-Y. Liu, O. Tuzel, and J. Xiao, "R-cnn for small object detection," in Asian Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 214-230, Springer, 2016. [CrossRef]

- X. Yang, J. X. Yang, J. Yang, J. Yan, Y. Zhang, T. Zhang, Z. Guo, X. Sun, and K. Fu, "Scrdet: Towards more robust detection for small, cluttered and rotated objects," in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 8232-8241, 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Garg, S. M. R. Garg, S. M. Seitz, D. Ramanan, and N. Snavely, "Where's waldo: matching people in images of crowds," in CVPR 2011, pp. 1793-1800, IEEE, 2011. [CrossRef]

- P. Parnes, K. P. Parnes, K. Synnes, and D. Schefstrom, "mStar: Enabling collaborative applications on the Internet," IEEE Internet Computing, vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 32-39, 2000. [CrossRef]

- Y. Mao, X. Y. Mao, X. Li, H. Su, et al., "Ship detection for SAR imagery based on deep learning: A benchmark," in 2020 IEEE 9th Joint International Information Technology and Artificial Intelligence Conference (ITAIC), vol. 9, pp. 1934-1940, IEEE, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Leng, Y. J. Leng, Y. Ye, M. Mo, C. Gao, J. Gan, B. Xiao, and X. Gao, "Recent advances for aerial object detection: A survey," ACM Computing Surveys, vol. 56, no. 12, pp. 1-36, 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhu, H. X. Zhu, H. Hu, S. Lin, and J. Dai, "Deformable convnets v2: More deformable, better results," in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 9308-9316, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Dai, H. J. Dai, H. Qi, Y. Xiong, Y. Li, G. Zhang, H. Hu, and Y. Wei, "Deformable convolutional networks," in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 764-773, 2017. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, K. C. X. Wang, K. C. Chan, K. Yu, C. Dong, and C. Change Loy, "Edvr: Video restoration with enhanced deformable convolutional networks," in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, pp. 0-0, 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhu, H. X. Zhu, H. Hu, S. Lin, and J. Dai, "Deformable convnets v2: More deformable, better results," in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 9308-9316, 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Ma, X. N. Ma, X. Zhang, H.-T. Zheng, and J. Sun, "Shufflenet v2: Practical guidelines for efficient cnn architecture design," in Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), pp. 116-131, 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Zhang, S. G. Zhang, S. Lu, and W. Zhang, "Cad-net: A context-aware detection network for objects in remote sensing imagery," IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 57, no. 12, pp. 10015-10024, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Ojala, M. T. Ojala, M. Pietikainen, and T. Maenpaa, "Multiresolution gray-scale and rotation invariant texture classification with local binary patterns," IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol. 24, no. 7, pp. 971-987, 2002. [CrossRef]

- N. Dalal and B. Triggs, "Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection," in 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR'05), vol. 1, pp. 886-893, IEEE, 2005. [CrossRef]

- T. Ojala, M. T. Ojala, M. Pietikainen, and T. Maenpaa, "Multiresolution gray-scale and rotation invariant texture classification with local binary patterns," IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol. 24, no. 7, pp. 971-987, 2002. [CrossRef]

- T. Ojala, M. T. Ojala, M. Pietikainen, and T. Maenpaa, "Gray scale and rotation invariant texture classification with local binary patterns," in *Computer Vision-ECCV 2000: 6th European Conference on Computer Vision Dublin, Ireland, -July 1, 2000 Proceedings, Part I 6*, pp. 404-420, Springer, 2000. 26 June. [CrossRef]

- C. Szegedy, W. C. Szegedy, W. Liu, Y. Jia, P. Sermanet, S. Reed, D. Anguelov, D. Erhan, V. Vanhoucke, and A. Rabinovich, "Going deeper with convolutions," in Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 1-9, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Oztel, G.I. Yolcu Oztel, and D. Akgun, "A hybrid lbp-dcnn based feature extraction method in yolo: An application for masked face and social distance detection," Multimedia Tools and Applications, vol. 82, no. 1, pp. 1565-1583, 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Nichani, A. E. Nichani, A. Radhakrishnan, and C. Uhler, "Do deeper convolutional networks perform better?," in International Conference on Machine Learning, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Zhao and M. Pietikainen, "Dynamic texture recognition using local binary patterns with an application to facial expressions," IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol. 29, no. 6, pp. 915-928, 2007. [CrossRef]

- K. Zhou, M. K. Zhou, M. Zhang, Y. Dong, J. Tan, S. Zhao, and H. Wang, "Vector decomposition-based arbitrary-oriented object detection for optical remote sensing images," Remote Sensing, vol. 15, no. 19, p. 4738, 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Li, S. N. Li, S. Jiang, J. Xue, S. Ye, and S. Jia, "Texture-aware self-attention model for hyperspectral tree species classification," IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing, vol. 62, pp. 1-15, 2023. [CrossRef]

- F. Zhou, Q. F. Zhou, Q. Chen, B. Liu, and G. Qiu, "Structure and texture-aware image decomposition via training a neural network," IEEE Transactions on Image Processing, vol. 29, pp. 3458-3473, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Yi, P. J. Yi, P. Wu, B. Liu, Q. Huang, H. Qu, and D. Metaxas, "Oriented object detection in aerial images with box boundary-aware vectors," in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, pp. 2150-2159, 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. Li, Y. W. Li, Y. Chen, K. Hu, and J. Zhu, "Oriented reppoints for aerial object detection," in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 1829-1838, 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Girshick, "Fast r-cnn," in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 1440-1448, 2015. [CrossRef]

| Method | HRSID | SSDD | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mAP50 | Precision | Recall | mAP50 | Precision | Recall | |

| YOLOv5s | 89.5% | 83.1% | 91.3% | 72.9% | 58.8% | 77.9% |

| YOLOv6-n | 89.9% | 85.5% | 91.4% | 82.0% | 87.2% | 86.4% |

| YOLOv7-tiny | 83.6% | 85.5% | 74.6% | 83.7% | 81.1% | 84.9% |

| YOLOv8n | 90.4% | 86.0% | 91.7% | 87.0% | 85.0% | 84.0% |

| YOLOX-s | 88.9% | 82.6% | 90.4% | 74.0% | 66.0% | 77.4% |

| CenterNet | 83.8% | 66.3% | 86.8% | 72.6% | 61.5% | 76.8% |

| FCOS | 82.1% | 76.2% | 85.1% | 69.5% | 53.1% | 76.0% |

| SSD300 | 80.0% | 70.5% | 84.5% | 67.2% | 52.3% | 75.4% |

| RetinaNet | 82.5% | 72.0% | 85.0% | 71.8% | 58.2% | 73.6% |

| Faster R-CNN | 80.5% | 66.9% | 83.4% | 69.5% | 67.2% | 74.2% |

| Cascade R-CNN | 86.0% | 74.0% | 87.8% | 76.4% | 70.0% | 78.8% |

| DETR | 81.0% | 70.0% | 80.0% | 71.0% | 60.2% | 78.3% |

| Deformable DETR | 89.1% | 84.3% | 90.0% | 79.8% | 84.2% | 81.9% |

| Sparse R-CNN | 85.0% | 78.0% | 86.0% | 78.0% | 73.0% | 79.0% |

| Dynamic R-CNN | 82.0% | 72.0% | 82.0% | 73.9% | 70.0% | 77.0% |

| GCNet | 81.5% | 70.0% | 82.0% | 75.0% | 65.2% | 79.0% |

| Libra R-CNN | 82.5% | 71.0% | 83.0% | 75.5% | 66.8% | 78.3% |

| DVDNet (Ours) | 90.9% | 86.2% | 91.7% | 87.2% | 90.4% | 90.7% |

| Method | HRSC2016 | VOC2012 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mAP50 | Precision | Recall | mAP50 | Precision | Recall | |

| YOLOv5s | 78.4% | 83.1% | 80.6% | 66.9% | 61.0% | 68.8% |

| YOLOv6-n | 78.1% | 82.7% | 80.2% | 66.3% | 60.5% | 68.0% |

| YOLOv7-tiny | 78.9% | 83.4% | 80.9% | 67.1% | 61.3% | 69.1% |

| YOLOv8n | 79.0% | 83.3% | 80.4% | 67.3% | 61.7% | 69.5% |

| YOLOX-s | 79.5% | 84.1% | 81.2% | 68.0% | 62.3% | 60.0% |

| CenterNet | 77.2% | 81.2% | 78.8% | 66.2% | 70.2% | 68.1% |

| FCOS | 78.3% | 82.6% | 80.2% | 67.5% | 61.5% | 69.2% |

| SSD300 | 74.1% | 79.0% | 76.3% | 64.9% | 70.0% | 70.7% |

| RetinaNet | 77.8% | 82.3% | 79.6% | 66.7% | 60.9% | 67.2% |

| Faster R-CNN | 79.2% | 84.0% | 81.1% | 67.8% | 61.8% | 69.9% |

| Cascade R-CNN | 80.6% | 84.5% | 82.5% | 68.7% | 62.5% | 60.9% |

| DETR | 78.5% | 83.0% | 80.3% | 68.1% | 62.4% | 70.4% |

| Deformable DETR | 79.8% | 84.2% | 81.9% | 68.9% | 63.0% | 70.9% |

| Sparse R-CNN | 79.7% | 84.3% | 81.6% | 68.6% | 73.0% | 71.0% |

| Dynamic R-CNN | 79.3% | 83.7% | 81.0% | 68.2% | 72.6% | 70.3% |

| GCNet | 78.7% | 82.9% | 80.5% | 67.0% | 60.8% | 68.2% |

| Libra R-CNN | 78.8% | 83.0% | 80.8% | 67.2% | 61.1% | 68.9% |

| DVDNet (Ours) | 80.7% | 85.0% | 83.0% | 75.4% | 74.7% | 72.7% |

| Combination | FPN | LBP | GDConv | HRSID | SSDD | ||||

| mAP50 | Precision | Recall | mAP50 | Precision | Recall | ||||

| None | 62.2% | 61.4% | 64.5% | 59.6% | 64.3% | 63.8% | |||

| FPN | √ | 75.0% | 62.1% | 65.5% | 72.0% | 65.1% | 64.8% | ||

| LBP | √ | 64.3% | 62.9% | 65.7% | 61.7% | 65.9% | 65.0% | ||

| GDConv | √ | 76.6% | 73.8% | 78.1% | 73.5% | 77.4% | 77.3% | ||

| LBP+GDConv | √ | √ | 89.5% | 74.9% | 79.0% | 85.9% | 78.6% | 78.1% | |

| DVDNet | √ | √ | √ | 90.9% | 86.2% | 91.7% | 87.2% | 90.4% | 90.7% |

| Combination | FPN | LBP | GDConv | HRSC2016 | VOC2012 | ||||

| mAP50 | Precision | Recall | mAP50 | Precision | Recall | ||||

| None | 55.2% | 60.5% | 58.4% | 45.2% | 50.5% | 68.4% | |||

| FPN | √ | 66.6% | 61.2% | 59.3% | 56.6% | 51.2% | 59.3% | ||

| LBP | √ | 57.1% | 62.0% | 59.5% | 53.1% | 57.0% | 56.4% | ||

| GDConv | √ | 68.0% | 72.8% | 70.7% | 64.4% | 62.5% | 63.4% | ||

| LBP+GDConv | √ | √ | 79.5% | 73.9% | 71.5% | 67.4% | 73.9% | 71.5% | |

| DVDNet | √ | √ | √ | 80.7% | 85.0% | 83.0% | 75.4% | 74.7% | 72.7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).