1. Introduction

Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) is unaffected by weather and time, making it one of the key tools for modern reconnaissance. It plays an increasingly important role in remote sensing [

1]. Through years of technological innovation, SAR systems have made significant advancements in resolution, polarization, and operational modes, enabling the acquisition of high-resolution SAR images [

2]. Aircraft, as an important type of target, has considerable value in both civilian and military domains, and aircraft detection is helpful for the effective airport management in civilian field and the combat and deployment in military applications [

3]. Therefore, precise detection of aircraft targets in high-resolution SAR images has substantial practical significance.

In the field of target detection in SAR images, there are two main types of approaches: traditional methods and deep learning methods. Traditional SAR target detection methods mainly rely on feature extraction and classifiers [

4], and their target recognition typically consists of three stages: detection, discrimination, and identification [

5]. In the detection stage, algorithms identify suspicious regions that may include actual targets and false alarms. The representative methods include the Constant False Alarm Rate (CFAR) [

6] algorithm based on clutter statistics and threshold extraction, along with its various improvements, such as Cell Averaging CFAR (CA-CFAR) [

7], Adaptive Cell Averaging CFAR (ACCA-CFAR) [

8], Stepwise Accumulation Cell Averaging CFAR (SCCA-CFAR) [

9], Order Statistics CFAR (OS-CFAR) [

10], and Smallest CFAR (SO-CFAR) [

11]. In the discrimination and identification stages, targets are differentiated from false alarms based on features such as size, shape, and semantics [

12]. Specifically for SAR aircraft target detection, the popular features include geometric features, gray-level statistical features, texture features, and electromagnetic scattering features, which are widely studied and applied, such as: Gao et al. [

13] successfully extracted the geometric parameters of aircraft targets in high-resolution SAR images by combining local self-similarity, the DBSCAN algorithm and the Hough transform. Chen et al. [

14] proposed a template matching method involving two relaxation variables to match significant feature vectors of aircraft targets, achieving favorable results. In traditional feature extraction and classifier-based methods, feature extraction often relies on prior knowledge and has strong interpretability. However, such methods are often limited to specific scenarios due to strong reliance on prior knowledge, resulting in limitations in scene generalization capabilities.

In recent years, with the rapid advancement of deep learning and its remarkable performance in various downstream tasks within the image domain, deep learning-based object detection algorithms have gradually gained prominence [

15]. These algorithms are typically classified into two categories: single-stage and two-stage detection frameworks. In the two-stage detection network, the detection generally involves two main steps. The first step is generating candidate regions, and the second step focuses on precise bounding box regression and classification of these regions. The key developments in these algorithms can be summarized as follows: RCNN (Region-based Convolutional Neural Networks) [

16] was one of the first to apply convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to object detection; subsequently, Fast R-CNN [

17] introduced the RoI Pooling strategy and employed the selective search algorithm to process candidate boxes, which enabled feature extraction to be performed just once on the original image, thus significantly reducing computational complexity; Faster R-CNN [

18] introduced Region Proposal Networks (RPN) to replace the selective search algorithm for generating candidate regions, enabling an end-to-end object detection framework; Mask R-CNN [

19] added an additional segmentation branch, allowing the network to handle both object detection and image segmentation tasks simultaneously. In the single-stage detection network, such as YOLO, SSD [

20], RetinaNet [

21], CenterNet [

22], FCOS [

23], EfficientDet [

24], and DETR [

25], the detection is completed in one step, which offers faster detection speeds, making them more suitable for real-time applications. Among these, anchor-free detection networks, such as YOLOv8, CenterNet, and FCOS, which do not require predefined anchors and exhibit greater adaptability to object shapes and scales, have garnered increasing attention in recent research.

Currently, mainstream detection networks, such as the YOLO series, Faster R-CNN and RetinaNet, are primarily designed for optical images, which have excellent performance. However, when directly applied to SAR images, the results are often unsatisfactory [

26]. The main reason is that there are significant differences between SAR and optical images in imaging principles, features and noise characteristics. The features of optical images are well-defined edges, rich texture information and low noise, while SAR images are influenced by scattering and speckle noise, leading to blurred and irregular target textures and structures. Furthermore, SAR imaging platforms are typically positioned at higher altitudes, which means that aircraft targets in SAR images are often small to medium-sized, adding further complexity to the application of existing models.

Most existing deep learning-based aircraft detection methods for SAR images train CNN models with classification and bounding box regression loss functions. These networks focus solely on the difference between true labels and high-confidence predictions within a single image, which fails to fully leverage the semantic relationship between target pixels of interest and background pixels in feature space. This weakens the model’s ability to recognize scattered aircraft points in complex areas, thereby restricting its feature extraction effect and generalization ability in large-scale aircraft regions. The core idea of contrastive learning is to minimize the distance between features of the same category in feature space and increase the distance between features of different categories. This simple concept has been widely applied in recent years in areas such as self-supervised learning for image features and model pretraining [

27]. For example, Kang et al. [

28] proposed a supervised contrastive learning-based regularization method for extracting urban buildings in high-resolution SAR images, which enhanced the similarity of similar pixels and the difference between dissimilar pixels, thus improving building recognition accuracy. Khosla et al. [

29] achieved better performance than traditional models trained with cross-entropy loss on the ImageNet dataset using supervised contrastive learning with given label information.

In independent classification tasks, relying on the principle of highly consistent features within the same class and significant differences across classes is typically effective. However, when it is applied to target detection, the situation becomes more complex. Target detection not only requires accurate classification of the target, but also needs to provide rich information for precisely performing bounding box regression. Therefore, relying solely on feature consistency to predict target categories will struggle to meet the diverse requirements of the regression process. Additionally, selecting positive and negative samples in contrastive learning also presents a challenge. The definitions of positive and negative samples are often relatively clear in the classification or segmentation tasks. However, this distinction becomes more complex in target detection, especially when the boundaries between the background and the target are unclear.

To address the aforementioned issues, this paper proposes the FCCS-YOLO network, an enhanced version of the YOLOv8 detection network, specifically designed for aircraft detection in SAR images. The new detection framework improves aircraft detection performance by adjusting the layer of target detection, introducing a novel (Conv-Passthrough-DSC) CPD feature map downsampling module, adopting Skew Intersection over Union (SIOU) regression loss function, and designing a supervised contrastive learning regularization method for SAR image aircraft detection.

The structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 presents the methodology,

Section 3 discusses the experiments and compares them with existing research, and

Section 4 provides an analysis of the experimental results. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper with a summary of the findings and suggests potential directions for future research.

2. Materials and Methods

In this section, we will provide a detailed introduction to the FCCS-YOLO network, focusing on the YOLOv8 object detection framework, the improvements made in FCCS-YOLO based on YOLOv8, and the reasons for these modifications.

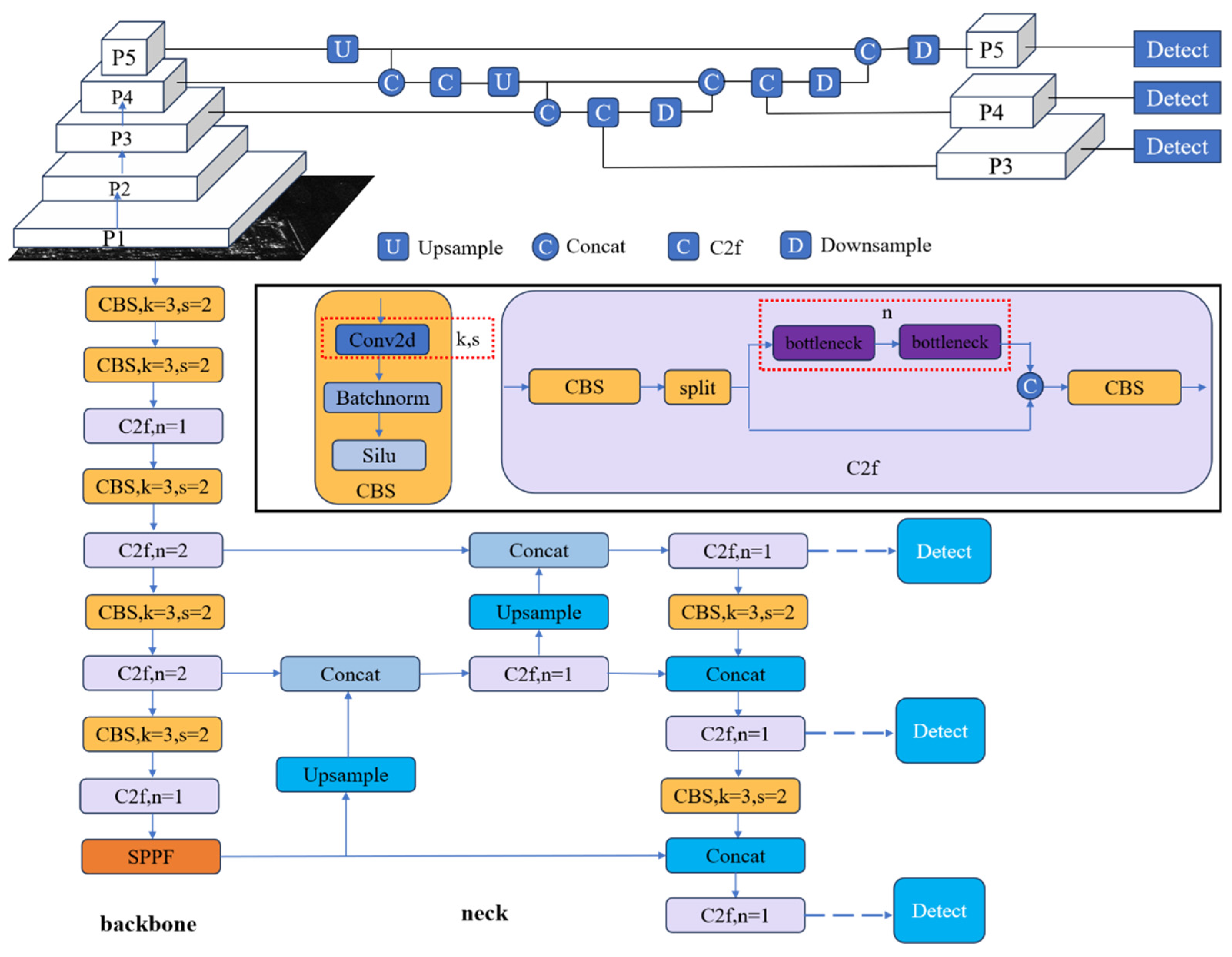

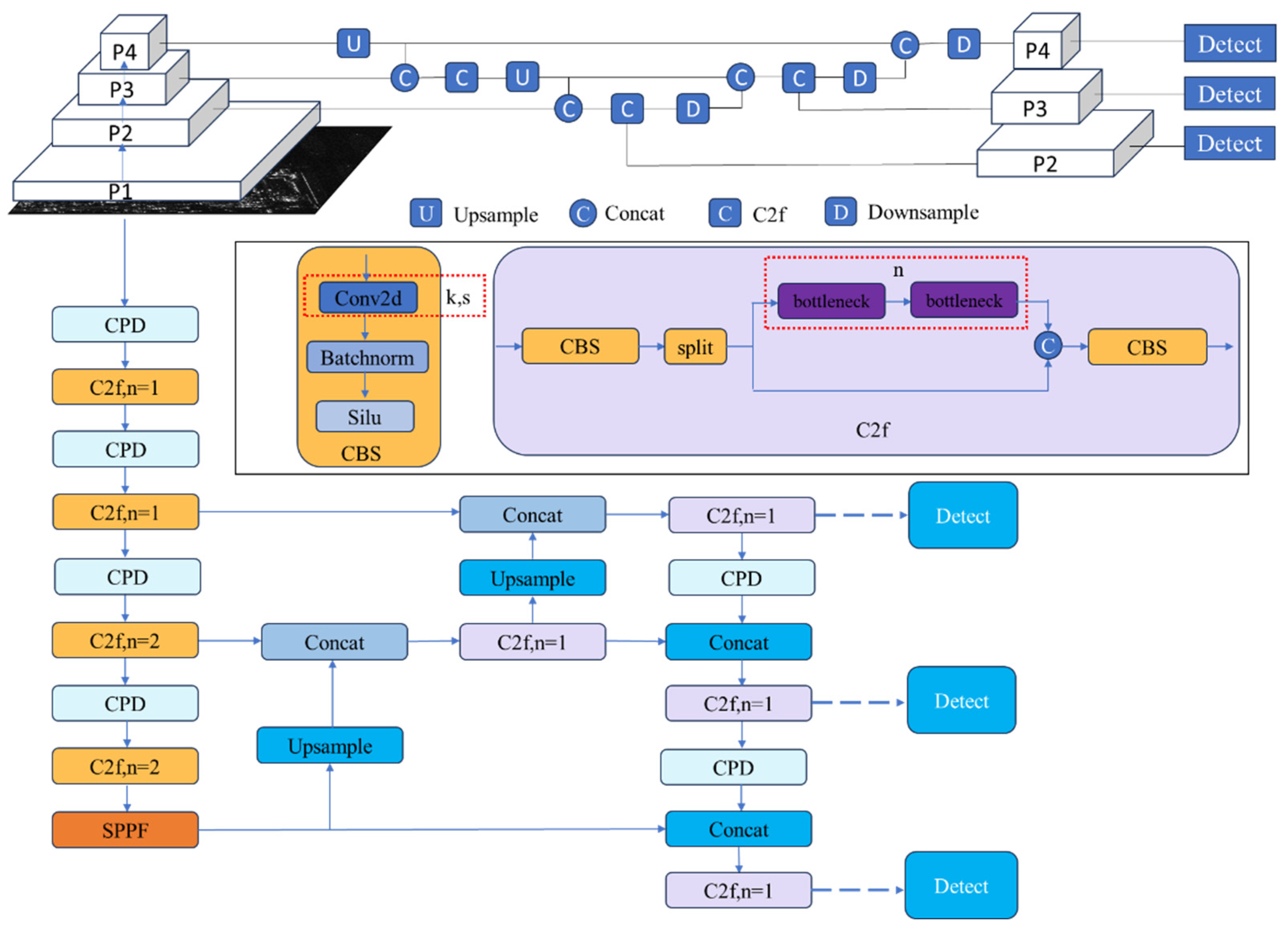

2.1. YOLOv8 Network

YOLOv8 introduces new features and improvements based on YOLOv5 [

30], achieving a better balance between speed and accuracy. It is available in five different model sizes—n, s, m, l, and x—based on network depth and width. Among these, the ’n’ model has the lowest computational load and parameters, making it suitable for deployment on low-resource devices. The overall structure of the YOLOv8 network consists of three main components: the Backbone, Neck, and Head, which are responsible for feature extraction, feature fusion, and object localization and regression, respectively. The network architecture is shown in

Figure 1.

The Backbone consists of CBS, C2f, and SPPF. The C2f (Causal Convolutional Fusion) module is a simplified version of the C3 (Cross-Stage Partial) module, achieved by reducing one convolutional layer. Additionally, inspired by the ELAN (Efficient Layer Aggregation Network) structure in YOLOv7 [

31], the bottleneck module is used to efficiently expand the gradient branches, enhancing the gradient flow and accelerating model convergence. At the network’s top layer, SPPF (Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fast) is employed to capture information from multiple receptive fields.

The Neck combines the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) [

32] and Path Aggregation Network (PAN) [

33], facilitating the fusion of low- and high-scale information to generate feature maps with rich semantic content.

The Head is composed of classification and regression branches. In contrast to YOLOv5, the confidence prediction branch is omitted, which effectively achieves decoupling of classification and regression.

YOLOv8 loss function comprises classification and regression losses. The regression loss is further divided into CIOU (Complete Intersection over Union) [

34] loss function and DFL (Distribution Focal Loss) [

35] loss function. The CIOU loss measures the discrepancy between the predicted and ground truth bounding boxes by considering factors like overlap, aspect ratio, and center distance, while the DFL loss function refines the regression of bounding box offsets by modeling the distribution of possible offsets more precisely.

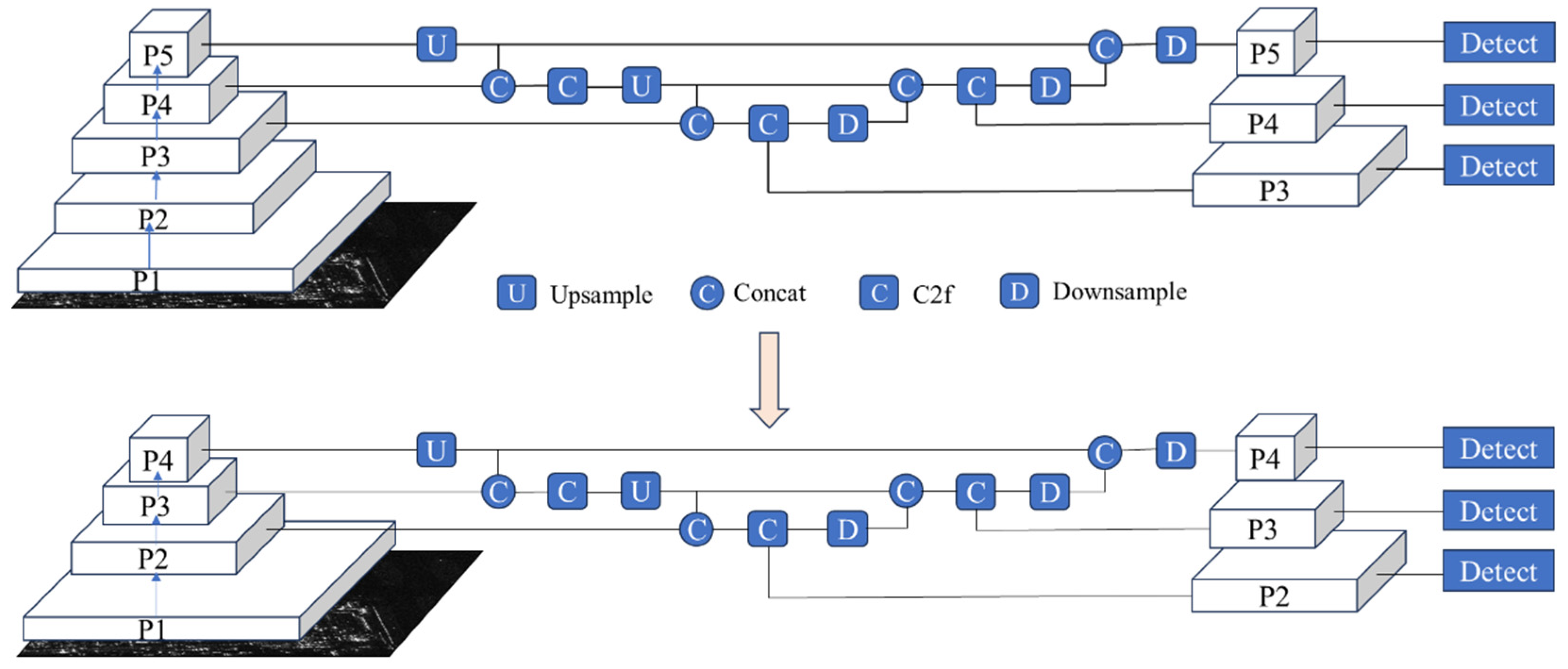

2.2. Object Detection Layer Adjustment

In YOLOv8 and other networks based on optical images, deeper network architectures are commonly employed, with multiple down-sampling operations used for feature extraction. Feature maps increasingly capture higher-level semantic information as the feature extraction progresses, while finer details are gradually lost. In the YOLOv8n object detection network, the backbone generates five feature maps through five down-sampling and feature extraction stages. These feature maps, with resolutions of 320×320, 160×160, 80×80, 40×40 and 20×20, are designated as P1, P2, P3, P4 and P5, respectively. As the resolution of these feature maps decreases, the finer details are progressively diminished, while the higher-level semantic information becomes more prominent. During the feature fusion stage, the information from the P3, P4, and P5 feature maps is combined, integrating high-level semantic features with low-level details from the earlier layers. This fusion process results in the final feature maps, with resolutions of 80×80, 40×40 and 20×20 for P3, P4 and P5, respectively.

Although downsampling feature maps increases the receptive field of neurons and enables the extraction of richer semantic information, the continuous downsampling can lead to the loss of significant positional information and make it difficult for the model to effectively focus on the target location for aircraft targets in SAR images, where targets occupy fewer pixels. Furthermore, the loss of semantic information caused by downsampling also negatively affects small targets’ feature learning and detection. To improve detection performance for medium and small-sized aircraft targets in SAR images, the network structure is adjusted by removing the downsampling operation and feature extraction module at the P5 feature map level, along with the corresponding detection head. For feature fusion, the P2, P3, and P4 feature maps extracted by the backbone are used for feature fusion and target detection. The adjusted network structure is shown in

Figure 2.

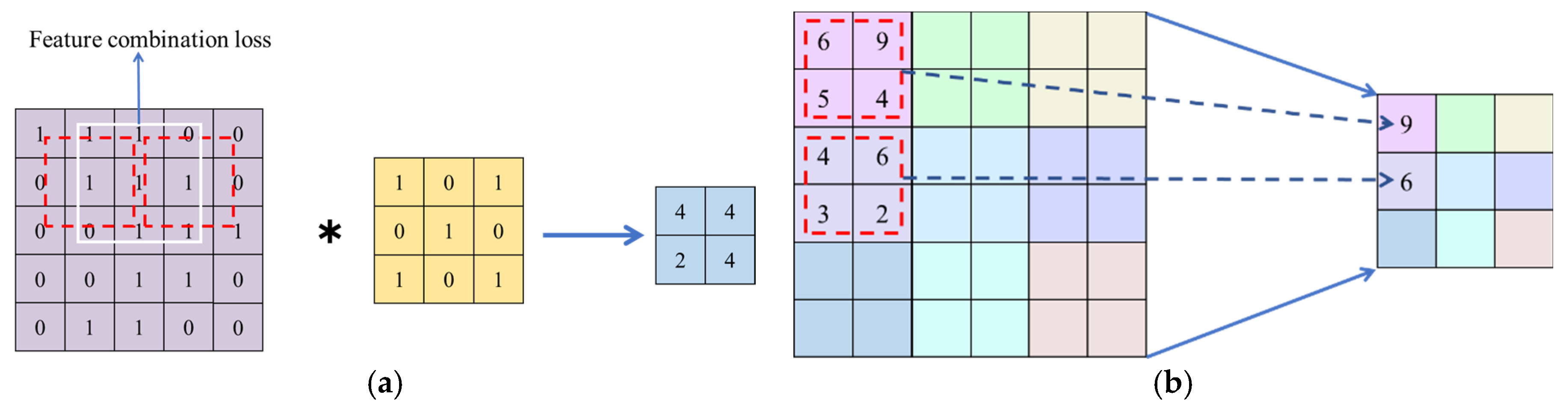

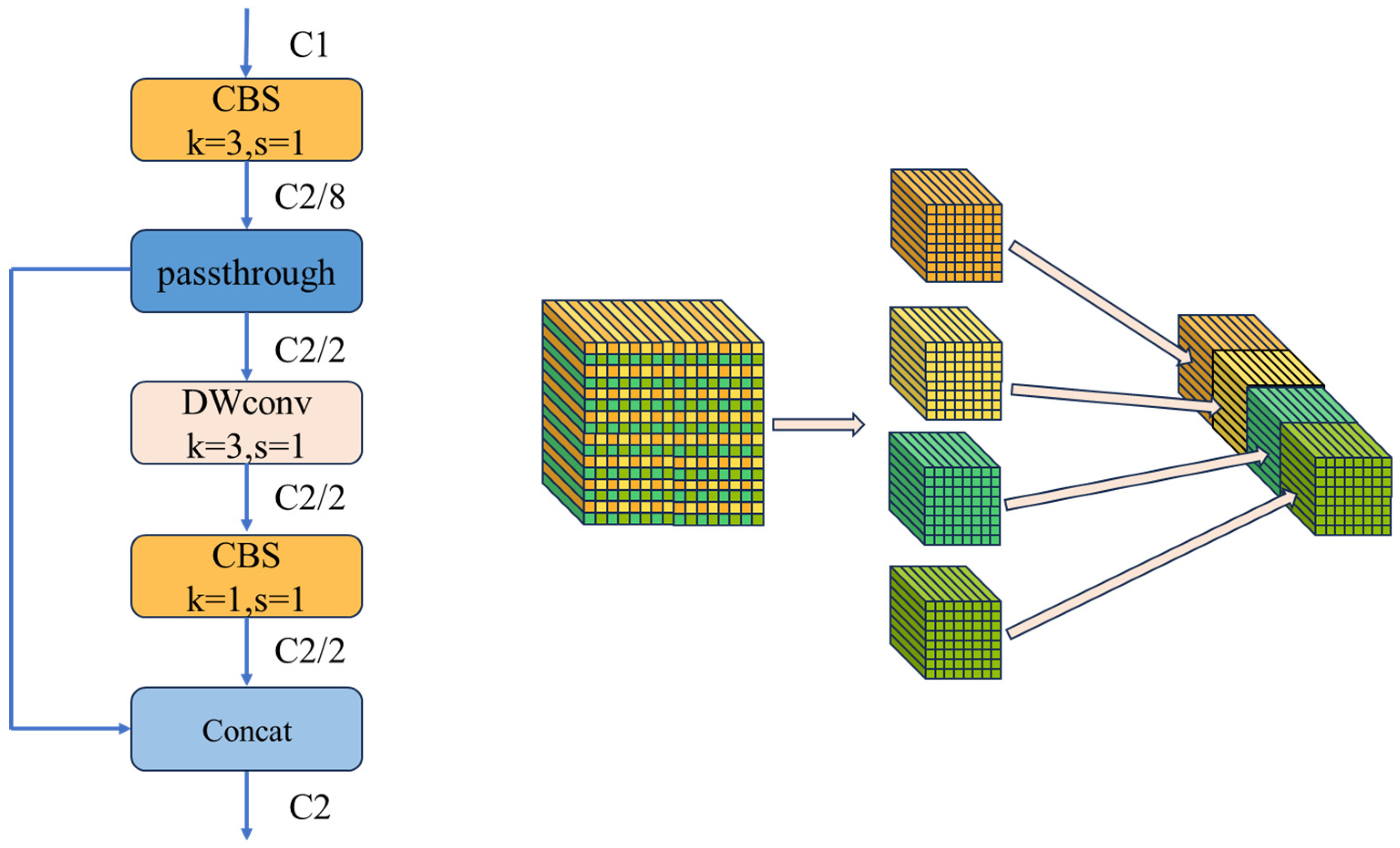

2.3. CPD Module

In convolutional neural networks, the backbone network typically follows a paradigm that combines downsampling and feature extraction. Common downsampling techniques for feature maps include pooling operations and strided convolutions. Pooling operations, including max pooling and average pooling, downsample feature maps by selecting the maximum or average value within local regions, typically using 2×2 or 3×3 kernels with a stride of 2. While pooling is simple and efficient, max pooling may cause the loss of certain feature information, which negatively impact the model’s translation invariance. Meanwhile, average pooling may lead to feature blurring, particularly when extracting edge information, which poses a significant challenge for detecting aircraft targets in SAR images. Another downsampling method is strided convolution, which reduces the feature map size by increasing the stride of the convolutional kernel. However, strided convolution involves higher computational costs and may increase model complexity, making the training process more difficult. Additionally, due to the nature of the stride, strided convolution can lead to the loss of certain feature combinations during downsampling, which subsequently reduces the diversity of extracted features.

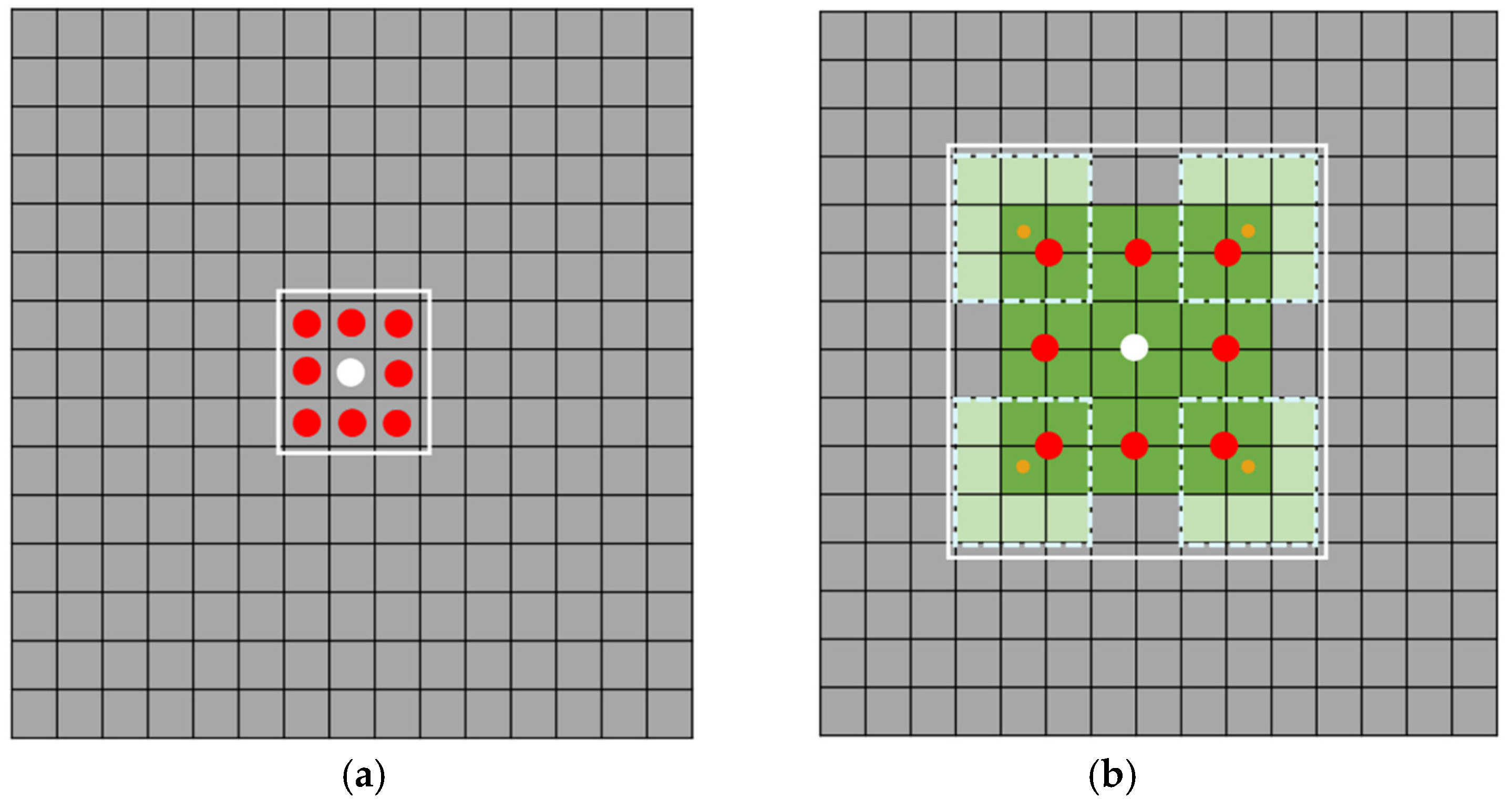

Figure 3 illustrates the downsampling processes of max pooling and strided convolution, respectively.

To address the aforementioned issue, we propose a novel downsampling structure, referred to as CPD module. This module can effectively enlarge the receptive field of the feature map while performing downsampling and ensuring computational efficiency simultaneously. The structure of the CPD module is illustrated in

Figure 4.

For an input feature map

X with width

W and height

H, as well as the number of channels

. After downsampling, the output feature map is expected to have a width of W/2, height of

H/2, and

channels. The first step is to apply a convolution operation with a kernel size of 3×3 and stride 1, adjusting the number of channels to 1/8 of the output channels. Next, a passthrough operation is applied to integrate some spatial information into the channels, resulting in feature map

, with its width and height reduced to half of the input feature map, and the number of channels adjusted to half of the output feature map. Afterward, depthwise separable convolution (DSC) [

36] is applied to further integrate spatial and channel information, producing a refined feature map

. Finally, concatenating

and

along the channel dimension, the final downsampled feature map is obtained, with a size of H/2, W/2 and

.

When downsampling using a strided convolution with a kernel size of 3 and stride 2, the computational cost is

In contrast, when the CPD module is used, the computational cost is

As for the number of channels, the number in the output feature map is typically expanded to twice that of the input feature map. Therefore, the downsampling scheme proposed in this paper significantly reduces computational complexity. As the number of output channels increases, the computation cost can be reduced to as low as half of the original.

Downsampling using a stride-2 convolution with a 3x3 kernel results in each feature point in the feature map having a receptive field that corresponds to a 3x3 surrounding area. In comparison, using the CPD module for downsampling increases the receptive field to 8x8, as illustrated in

Figure 5. The white circle marks the current feature point, and the solid white box indicates the perceptible range of information from the feature center. Serving as the primary downsampling structure of the network, the CPD module effectively compensates for the reduced receptive field resulting from the removal of the P5 feature map.

The overall structure of the FCCS-YOLO network after incorporating the CPD module as the downsampling component is shown in

Figure 6.

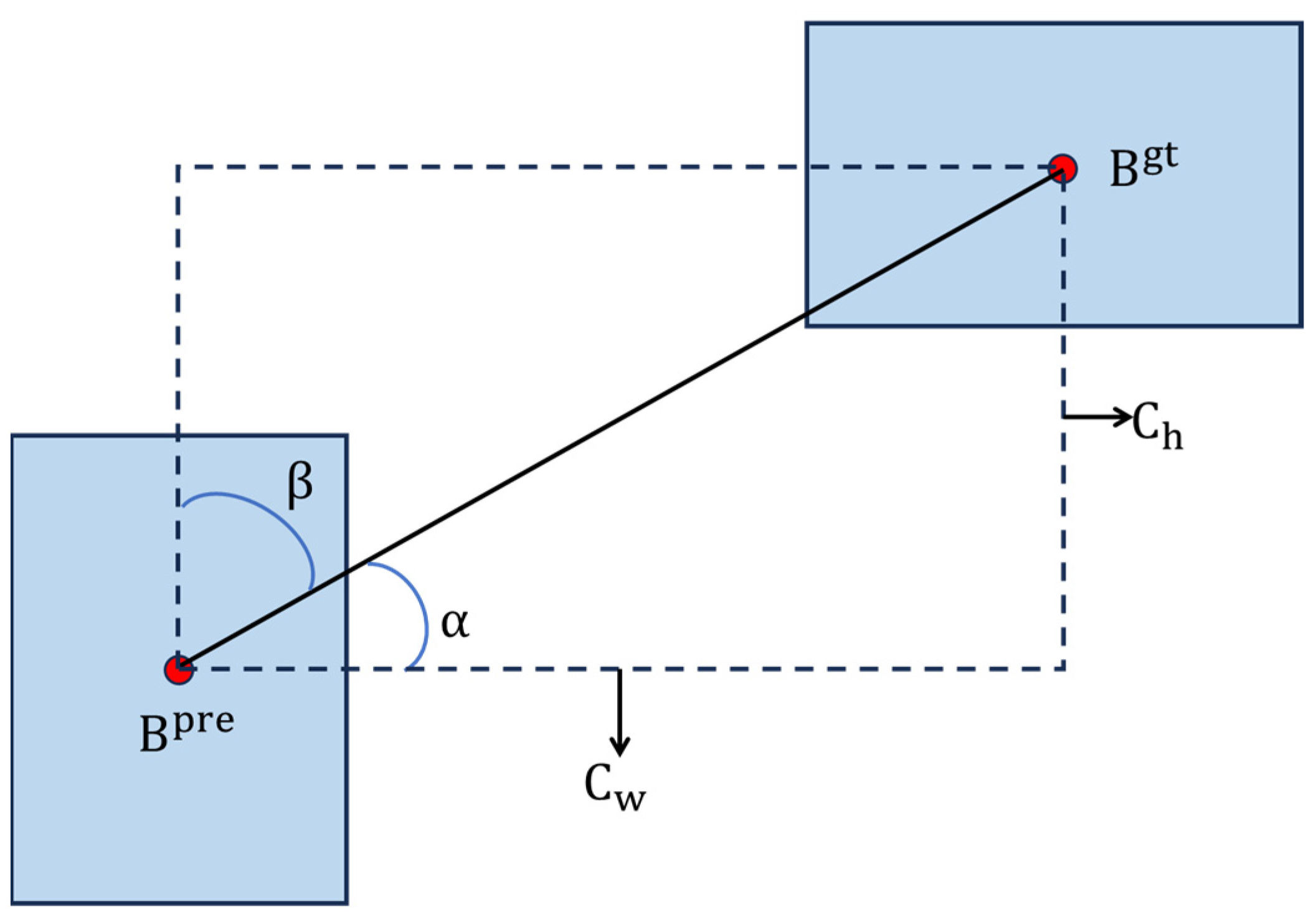

2.4. SIOU Loss

In deep learning-based target detection tasks, the selection of the loss function is critical to model performance [

37]. YOLOv8 utilizes the CIOU loss function, defined as follows:

In Equations (3) and (4), and represent the coordinates of the center points of the predicted box and the ground truth box (GtBox), respectively; denotes the Euclidean distance; represents the diagonal distance of the minimum enclosing rectangle that contains both the predicted box and the GtBox; represents the width of the GtBox; represents the height of the GtBox; denotes the width of the predicted box; and denotes the height of the predicted box.

Although the CIOU loss function considers the overlap area, center point distance, and aspect ratio between the predicted box and GTBox during box regression, it has the drawback of degenerating into the standard IOU loss function when the aspect ratios of the predicted box and GTBox are consistent, which affects the performance of box regression. To address this issue, SIOU [

38] further optimizes the CIOU by incorporating the calculation of angular deviation, enhancing its performance in rotated and tilted object detection. SIOU comprehensively considers various attributes of the bounding box, such as size, position and angle, thereby improving both localization accuracy and the stability of box regression. During training, SIOU encourages the model’s predicted box to quickly align with the GTBox along a specific axis, enabling the model to find the optimal detection box more efficiently.

Figure 7 illustrates the SIOU calculation.

The calculation formula of the SIOU loss function is given below:

In equations (5) to (11), ∆ represents the distance loss, Ω represents the shape loss, and denote the width and height of the minimum enclosing rectangle between the predicted box and the GTBox. The angle loss Λ represents the minimum angle between the line connecting the center points of the predicted box and the GTBox, while the shape loss Ω primarily describes the shape difference between the predicted box and the GTBox.

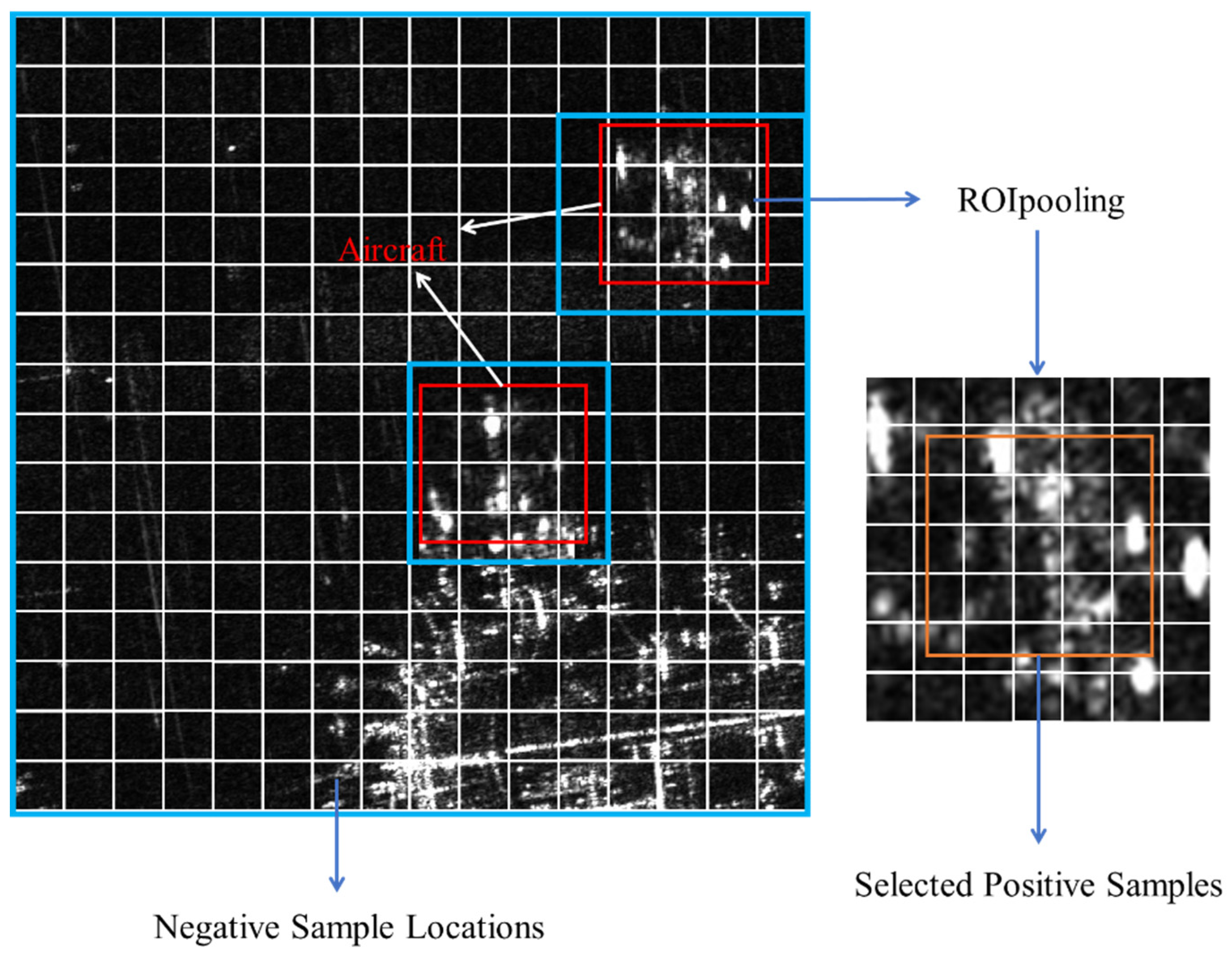

2.5. Contrastive Learning Regularization Method

Features with small intra-class variance and large inter-class variance are generally more discriminative. Therefore, applying contrastive learning to constrain the features extracted by the network is effective for tasks like semantic segmentation or classification, as these tasks rely on feature classifiers, where feature discriminability directly improves classification performance. However, for target detection in SAR images, attention must also be paid to details such as the position, size, and shape of the object, which presents challenges when using contrastive learning. When applied to high-level features, contrastive learning may cause the network to prioritize feature consistency, potentially overlooking important details like position and shape.

To address the challenge of applying contrastive learning to target detection in SAR images, this paper proposes incorporating contrastive learning regularization into the P2 feature map extracted by the backbone after analyzing the structure and function of different parts of the convolutional neural network, aiming to constrain the similarity of local features within the same class and the dissimilarity of local features across different classes. On the one hand, the P2 feature map, extracted by the backbone, has undergone several layers of feature extraction, meaning each feature point on the feature map contains some local information from its surroundings. On the other hand, since the feature extraction occurs at a relatively low level, each feature point on the feature map has a smaller receptive field compared to higher-level feature maps or feature maps after feature fusion, preventing the aircraft target region from being contaminated by excessive features from non-aircraft target areas.

The proposed contrastive learning method for aircraft target detection in SAR images aims to optimize the following loss:

In equations (12-18), represents the number of positive sample points, represents the number of negative sample points, represents the average feature of positive samples, and represents the average feature of negative samples. The constant τ is used to prevent division by zero, ensuring the accuracy of the loss calculation. and represent the cosine losses between the features of positive and negative samples, respectively, guiding the angle between the feature of a sample and its average feature to be as small as possible. represents the cosine loss between positive and negative samples, guiding the angle between the average feature of positive samples and the average feature of negative samples to be as large as possible. represents the magnitude loss between positive sample features and negative sample features, guiding the magnitude of the feature between positive and negative samples to be as close as possible.

The loss function designed in this paper combines cosine loss and magnitude loss to form the similarity measurement mechanism for the contrastive learning task. Specifically, cosine loss ensures semantic consistency in the direction of similar samples, allowing for accurate similarity assessment even when feature magnitudes differ. Magnitude loss constrains the vector magnitude to enforce consistency in feature strength, thereby enhancing the stability of feature representations. Compared to traditional Euclidean distance metrics, the proposed design shows significant advantages. By separately measuring and constraining direction and magnitude, the proposed loss function demonstrates higher flexibility and robustness in contrastive learning tasks, better accommodating the diverse feature expression needs of samples.

To address the issue of positive and negative sample selection in contrastive learning for aircraft detection in SAR images, this paper uses the pixel-level positive and negative sample selection strategy shown in

Figure 8. Positive samples are taken from the features corresponding to all aircraft target regions. For a given aircraft target, the feature map corresponding to its GTBox is first extracted using ROI Pooling, resulting in a 7×7 feature map. Since the outermost feature points contain more background information, the central 5×5 region of this 7×7 feature map is selected as the positive sample features and added to the positive sample set. For negative samples, after excluding the regions corresponding to positive samples, random feature points are sampled from the remaining areas of the feature map to form the negative sample set. Since the data loading is randomized during train, the network not only focuses on information within the same image but also learns the distribution of positive and negative samples across the entire dataset.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the YOLOv8 Network.

Figure 1.

Architecture of the YOLOv8 Network.

Figure 2.

Schematic of detection layer adjustment.

Figure 2.

Schematic of detection layer adjustment.

Figure 3.

Feature map downsampling methods. (a) The downsampling process using max pooling, (b) The downsampling process using strided convolution.

Figure 3.

Feature map downsampling methods. (a) The downsampling process using max pooling, (b) The downsampling process using strided convolution.

Figure 4.

Structure diagram of the Conv-Passthrough-DSC (CPD) module. The left shows the overall structure of the CPD module, and the right illustrates the passthrough operation.

Figure 4.

Structure diagram of the Conv-Passthrough-DSC (CPD) module. The left shows the overall structure of the CPD module, and the right illustrates the passthrough operation.

Figure 5.

Receptive field analysis. (a) Receptive field of the feature map after downsampling by a stride-2 convolution with a 3x3 kernel. (b) Receptive field of the feature map after downsampling by the CPD module.

Figure 5.

Receptive field analysis. (a) Receptive field of the feature map after downsampling by a stride-2 convolution with a 3x3 kernel. (b) Receptive field of the feature map after downsampling by the CPD module.

Figure 6.

Overall structure of the FCCS-YOLO network.

Figure 6.

Overall structure of the FCCS-YOLO network.

Figure 7.

Skew Intersection over Union (SIOU) Calculation Diagram.

Figure 7.

Skew Intersection over Union (SIOU) Calculation Diagram.

Figure 8.

Illustration of Positive and Negative Sample Sampling.

Figure 8.

Illustration of Positive and Negative Sample Sampling.

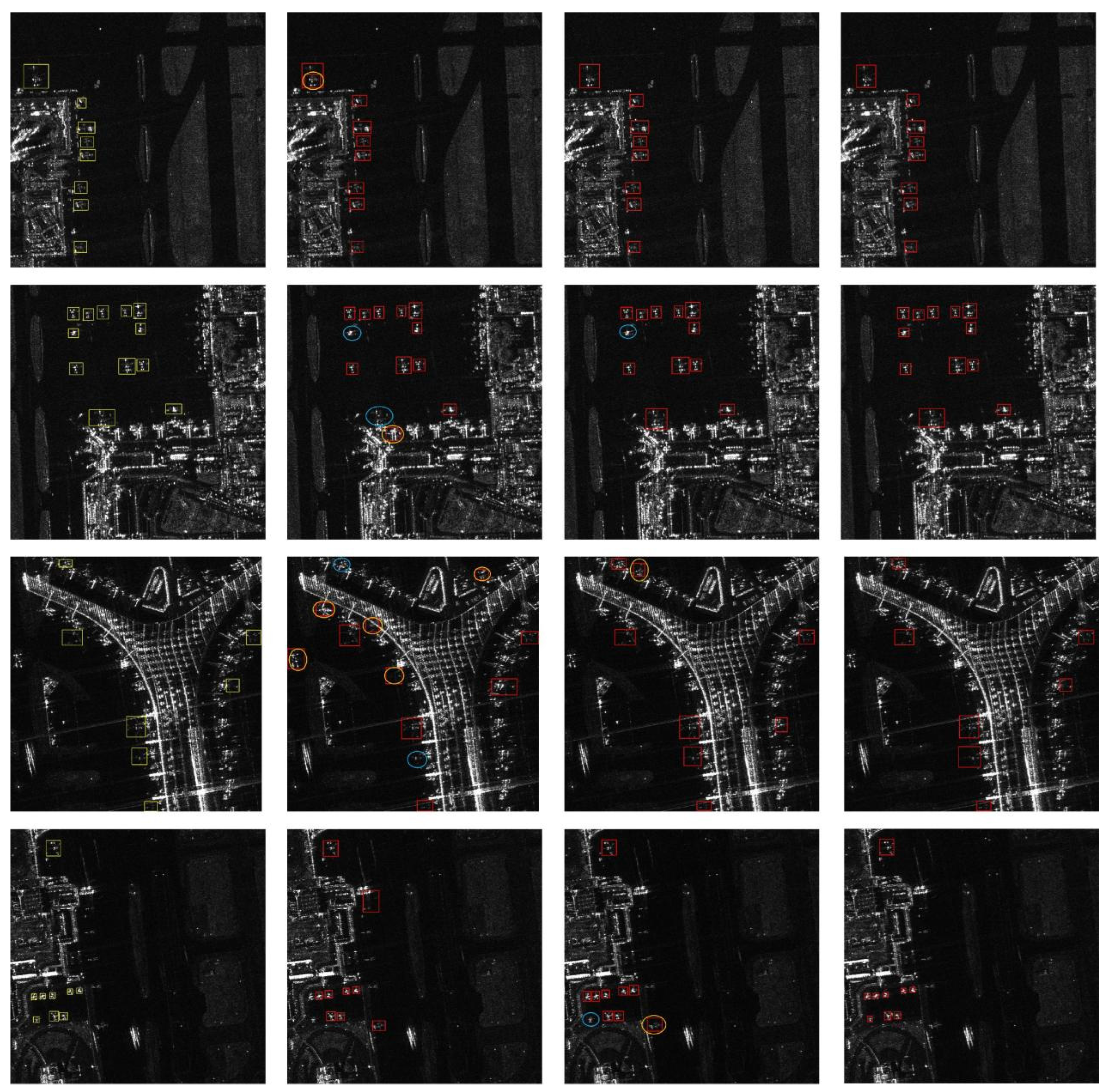

Figure 9.

The visual results on the SAR-AIRcraft-1.0 dataset are displayed. The first column represents the ground truth, the second column shows the detection results from Faster-RCNN, the third column presents the YOLOv8 detection results, and the fourth column displays the detection results from FCCS-YOLO.

Figure 9.

The visual results on the SAR-AIRcraft-1.0 dataset are displayed. The first column represents the ground truth, the second column shows the detection results from Faster-RCNN, the third column presents the YOLOv8 detection results, and the fourth column displays the detection results from FCCS-YOLO.

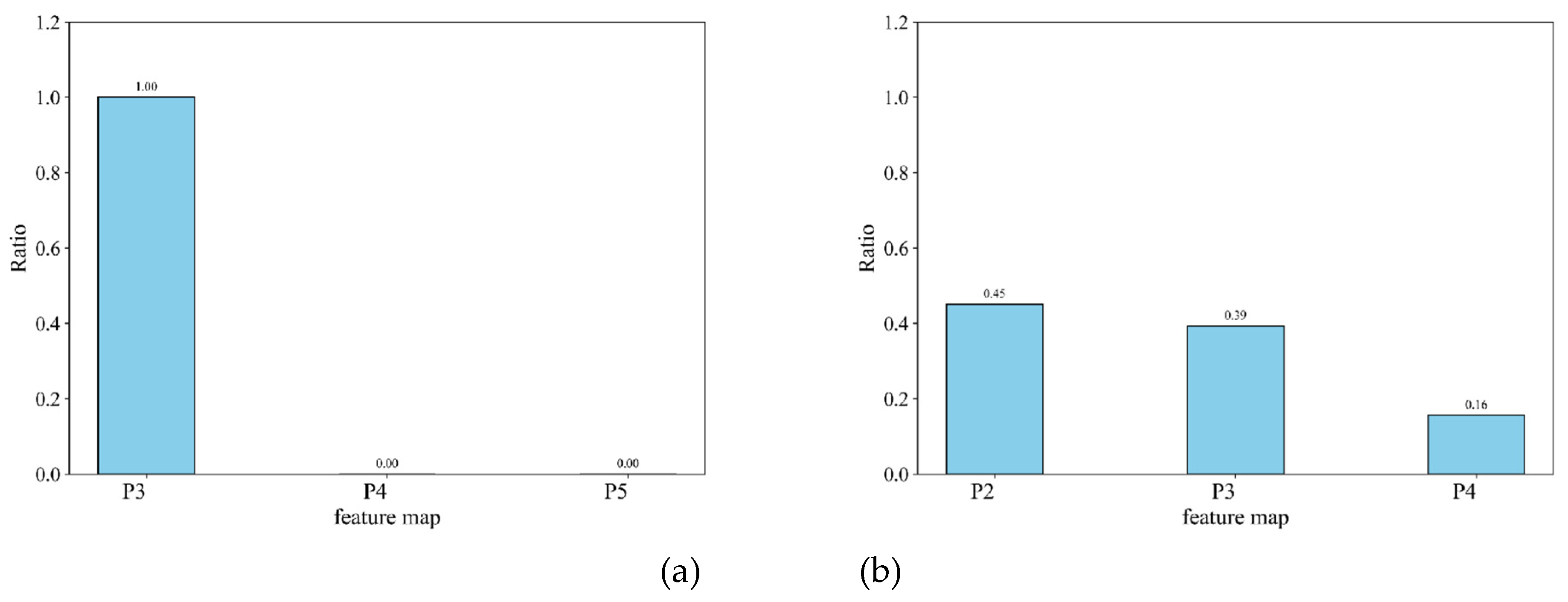

Figure 10.

Proportions of High-Confidence Predictions Across Feature Maps. (a) illustrates the distribution of high-confidence predictions across feature maps in the YOLOv8n, while (b) illustrates the distribution of high-confidence predictions across feature maps after modifying the detection layers.

Figure 10.

Proportions of High-Confidence Predictions Across Feature Maps. (a) illustrates the distribution of high-confidence predictions across feature maps in the YOLOv8n, while (b) illustrates the distribution of high-confidence predictions across feature maps after modifying the detection layers.

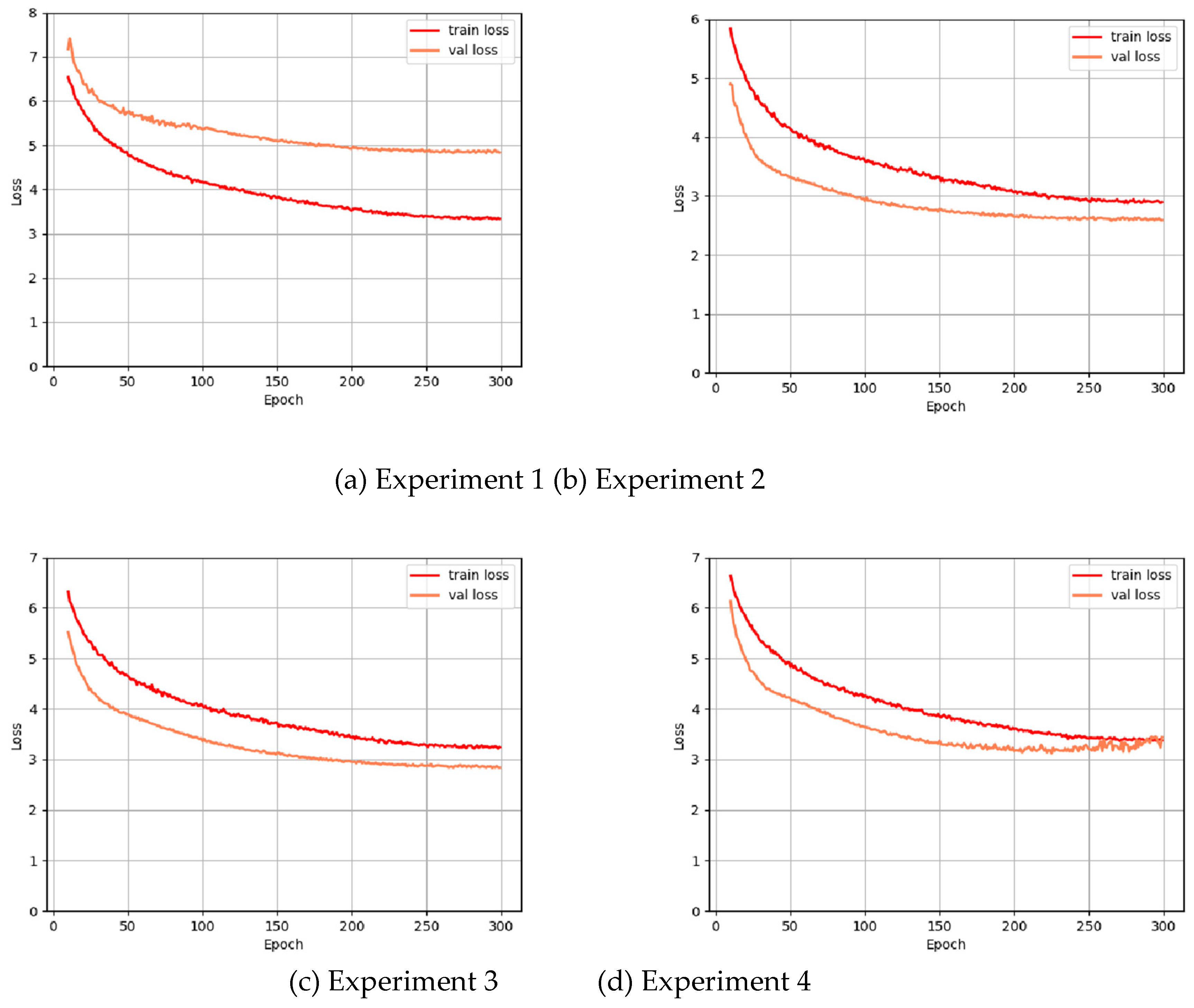

Figure 11.

Loss Curve During Training.

Figure 11.

Loss Curve During Training.

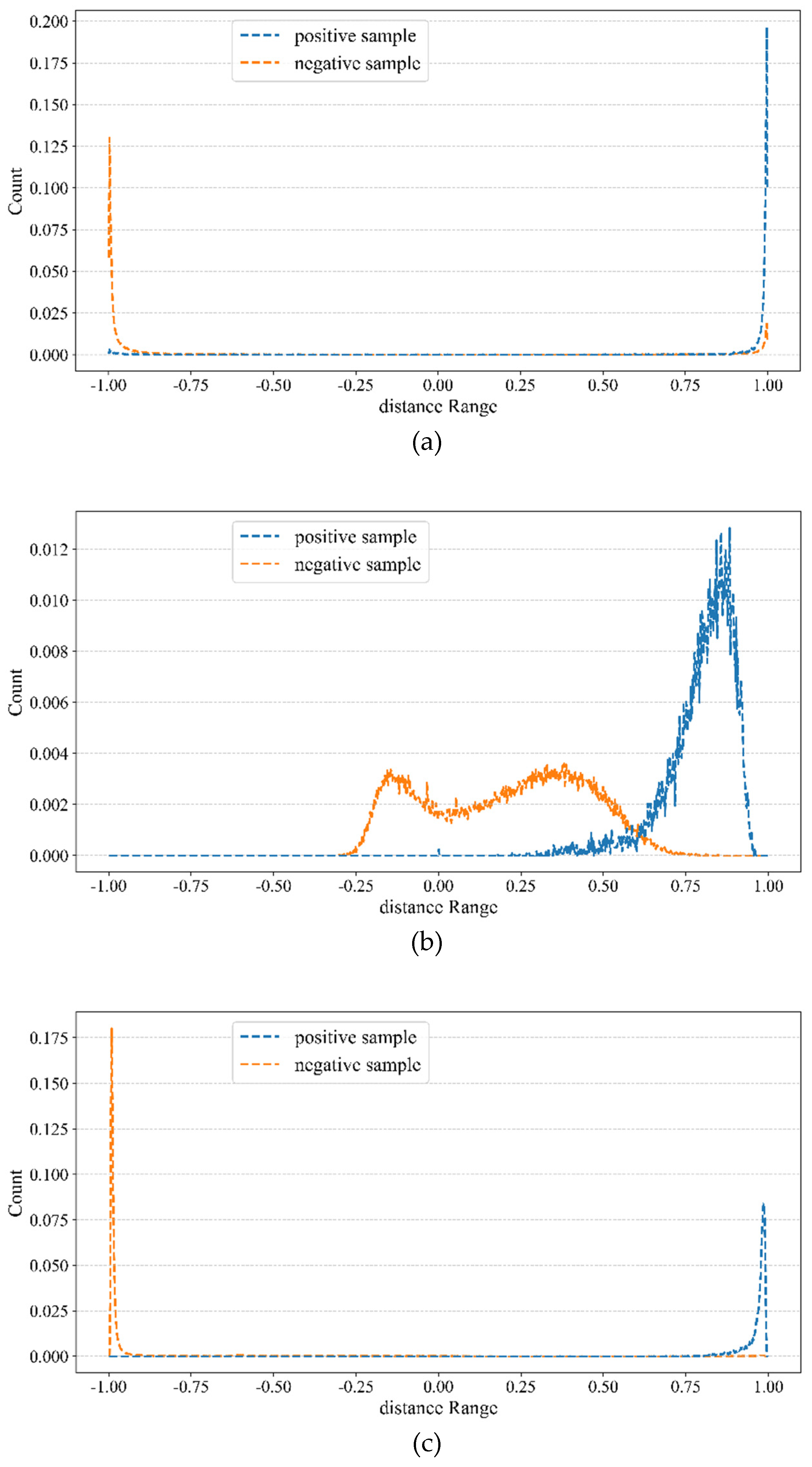

Figure 12.

The distance distribution of positive and negative samples relative to the average positive sample in the feature map.

Figure 12.

The distance distribution of positive and negative samples relative to the average positive sample in the feature map.

Table 1.

Ablation experiments.

Table 1.

Ablation experiments.

| |

A

|

B

|

C

|

D

|

E

|

| layer adjustment |

× |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

| CPD |

× |

× |

√ |

√ |

√ |

| SIOU |

× |

× |

× |

√ |

√ |

| contrastive learning |

× |

× |

× |

× |

√ |

| mAP50 (%) |

93.8 |

93.9 |

94.3 |

94.8 |

95.5 |

| P (%) |

86.3 |

85.5 |

86.5 |

87.1 |

90.0 |

| R (%) |

89.0 |

91.3 |

91.4 |

92.0 |

93.2 |

| Params (M) |

3.01 |

0.98 |

0.87 |

0.87 |

0.87 |

Table 2.

FCCS-YOLO versus other networks on the SAR-AIRcraft-1.0 dataset.

Table 2.

FCCS-YOLO versus other networks on the SAR-AIRcraft-1.0 dataset.

|

Methods

|

mAP50 (%)

|

P (%)

|

R (%)

|

Params (M)

|

| Faster R-CNN |

70.5 |

72.2 |

75.3 |

44.25 |

| Cascade R-CNN |

77.8 |

89.0 |

79.5 |

50.2 |

| SSD |

79.2 |

82.0 |

78.2 |

45 |

| FCOS |

87.0 |

76.5 |

80.6 |

34.5 |

| CenterNet |

90.9 |

82.3 |

82.1 |

34 |

| YOLOv5 |

92.1 |

87.3 |

83.6 |

4.53 |

| YOLOv8 |

93.8 |

86.3 |

89.0 |

3.01 |

| FCCS-YOLO |

95.5 |

90.1 |

93.2 |

0.87 |