1. Introduction

With the rapid development of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) technology, its applications in emergency rescue [

1], marine monitoring [

2], environmental surveillance [

3], and various other fields have become increasingly widespread. Particularly in the realm of information perception, UAVs leverage their advantages of flexible deployment, high mobility, and broad field of view to effortlessly acquire detailed information about target areas. However, dense multi-scale object detection remains one of the most challenging issues in object detection tasks due to factors such as small target sizes, large quantities, significant scale variations in UAV aerial imagery, resolution limitations, varying illumination conditions, and target occlusion [

4,

5,

6]. This not only demands detection algorithms to exhibit high accuracy and robustness but also requires real-time processing and analysis of massive image data to meet the urgent need for rapid response in practical applications [

7].

In the field of object detection, deep learning-based algorithms have become mainstream and are primarily divided into two-stage detection algorithms and single-stage detection algorithms based on their workflow. Two-stage detection algorithms [

8], such as the R-CNN series [

9], first generate region proposals and then perform feature extraction and classification on these regions. Although this approach achieves higher detection accuracy, it incurs higher computational costs and slower speeds, making it unsuitable for scenarios requiring rapid responses. The Faster R-CNN [

10] algorithm significantly improves detection speed by introducing a Region Proposal Network, but it still requires classification and bounding box regression for each candidate region, which limits its performance in real-time applications. In contrast, single-stage detection algorithms [

11], such as the YOLO (You Only Look Once) series [

12] and SSD series [

13], directly predict object classifications and bounding boxes on the entire image without generating region proposals, resulting in faster detection speeds suitable for real-time applications. Notably, the YOLO series has gained attention for its rapid detection speed and balanced performance, maintaining detection accuracy while ensuring speed. However, single-stage algorithms generally lag slightly behind two-stage algorithms in precision, particularly in small object detection.

Current mainstream object detection algorithms, primarily designed for natural scenes, often underperform when directly applied to UAV aerial imagery. This performance gap stems from significant differences between natural and aerial scenarios: drastic variations in object scales, high proportions of small objects, dense object distributions, and severe mutual occlusion. These factors collectively lead to a notable decline in detection accuracy [

14]. To address these challenges, researchers have proposed various model improvement strategies. Lin et al. [

15] pioneered the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN) architecture, enabling multi-scale feature interaction through cross-layer connections, which established a foundational framework for efficient feature fusion. Building on FPN, Liu et al. [

16] optimized feature propagation paths by proposing the Path Aggregation Network (PANet), which significantly enhanced the utilization of low-level features through a bottom-up augmentation path, though its performance remains highly sensitive to image quality. Deng et al. [

17] introduced a progressive scale transformation method combined with a global-local fusion mechanism, effectively boosting small object detection performance, but this approach shows clear limitations in tracking medium-to-large objects. Cai et al. [

18] improved detection accuracy by integrating a coordinate attention mechanism into the YOLOv4-tiny model, yet its generalization capability remains insufficient for cross-scene tracking tasks. Zhu et al. [

19] proposed a detection architecture combining multi-transformer prediction heads with CBAM attention, significantly optimizing small object detection, though its high computational complexity compromises real-time efficiency. For model efficiency optimization, Ma et al. [

20] innovatively employed channel splitting and recombination techniques, enhancing cross-scale feature interaction while achieving adaptive multi-level feature fusion. Sandler et al. [

21] designed an inverted residual structure with high-dimensional channel expansion, which improves feature representation while maintaining model lightweightness, but exhibits significant accuracy degradation in occluded scenarios. These studies demonstrate that balancing real-time performance with robust multi-scale object detection remains a critical technical bottleneck requiring breakthroughs in UAV image-based target detection.

To address the aforementioned challenges, this paper proposes an enhanced algorithm named DMF-YOLOv10 based on the YOLOv10s framework, specifically designed for UAV aerial image detection scenarios. The primary innovative contributions of this study are manifested in the following three aspects:

(1) Innovative Design of Dynamic Dilated Serpentine Convolution (DDSConv) Layer: This layer dynamically adjusts the dilation rate of convolutional kernels according to the scale variations of input features, enabling adaptive reshaping of receptive fields. This mechanism effectively captures local features of small targets in aerial images. The improvement specifically addresses the limitations of traditional convolutional layers in handling weak texture features and low pixel density in aerial imagery, thereby enhancing the extraction of discriminative deep feature representations.

(2) Multi-scale Feature Aggregation Module (MFAM): A dual-branch feature interaction strategy is proposed to achieve multi-scale information complementarity by fusing high-resolution detail features with deep semantic features. The module employs dual-dimensional spatial attention to dynamically weight fused features, effectively suppressing redundant information interference. Compared to traditional fusion methods, MFAM significantly reduces information loss while enhancing feature representation capability through the integration of spatial attention and adaptive weight allocation mechanisms, thereby providing more discriminative multi-scale representations for detection heads.

(3) MFAM-Neck Network for Aerial Objects: To address the challenges of large size variations and clustered small targets in aerial images, a dedicated neck network based on MFAM is designed for feature fusion. This architecture adopts a phased fusion strategy that reconstructs fusion pathways by associating dual-scale features, enabling fine-grained feature enhancement. Combined with MFAM's spatial co-optimization capability, the model significantly improves localization accuracy for multi-scale targets, particularly micro-scale objects.

(4) Extended Window-based Bounding Box Regression Loss Function (EW-BBRLF): Inspired by the auxiliary bounding box acceleration mechanism in Inner-IoU, this loss function integrates the direction-aware advantages of Complete Intersection over Union (CIoU) loss with the scale sensitivity of Ln norm. By adaptively adjusting auxiliary bounding box dimensions through a dynamic scaling coefficient, it enhances localization precision and detection accuracy.

The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews recent advancements in multi-scale object detection for aerial imagery.

Section 3 presents the improved model proposed for small object detection in UAV images, detailing the model architecture and operational principles of related modules.

Section 4 outlines the experimental environment and parameter configurations, followed by test results on VisDrone2019 and HIT-UAV datasets, including ablation studies, comparative evaluations, and visualization experiments designed to validate the effectiveness of the proposed method.

Section 5 concludes the paper and discusses potential directions for future research.

3. Proposed Model

3.1. Overview of YOLOv10

As a state-of-the-art achievement in real-time object detection, YOLOv10 incorporates innovative improvements while inheriting the advantages of its predecessors. The algorithm not only optimizes detection capabilities but also extends to multi-task support including classification, segmentation, and tracking. Its outstanding performance and architectural adaptability have garnered significant attention in the computer vision community [

41,

42,

43]. The YOLOv10s baseline model selected in this study employs a three-stage architecture: Backbone (feature extraction layer), Neck (feature fusion layer) and Head (prediction output layer). The network architecture is illustrated in

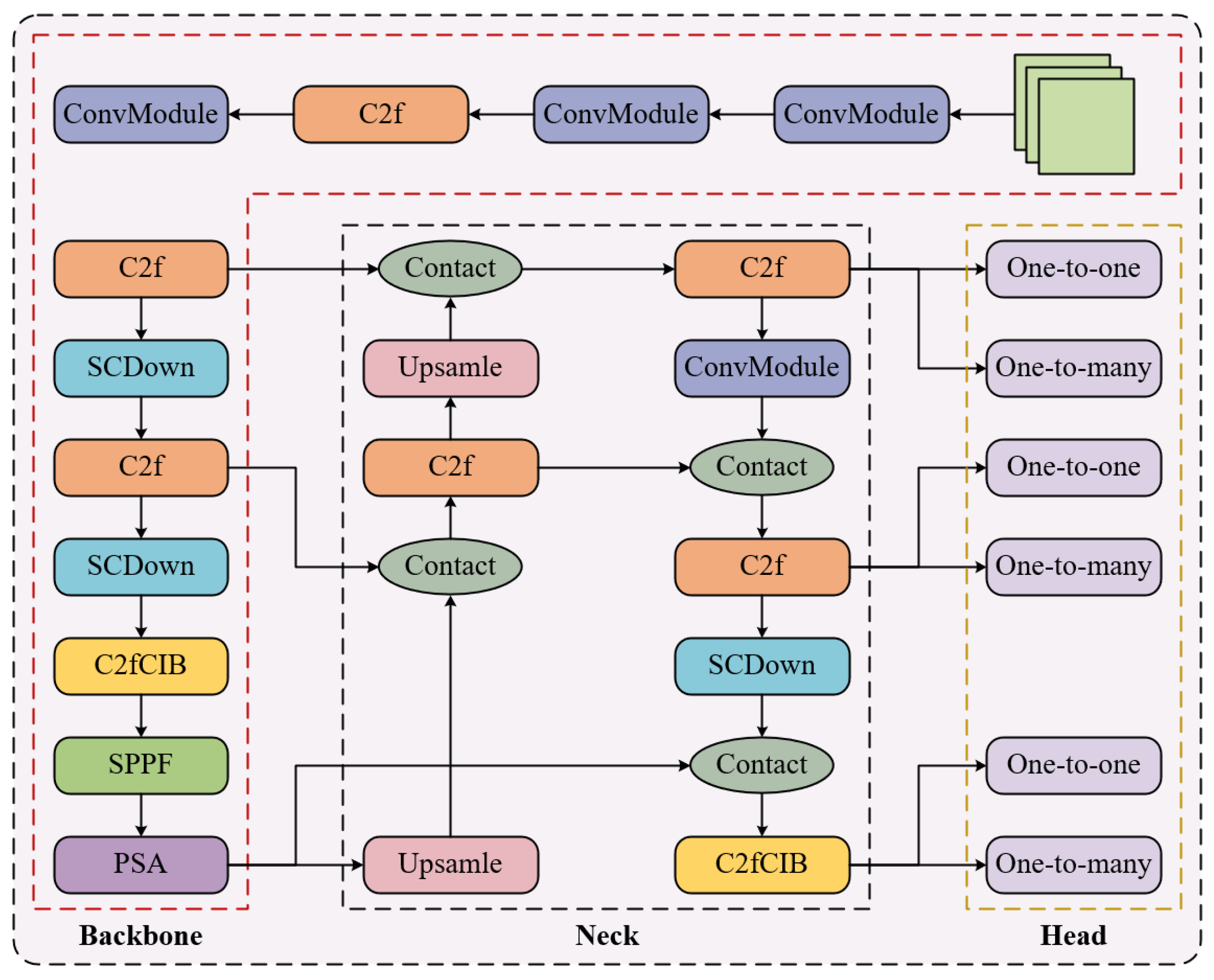

Figure 1.

The backbone architecture builds upon Darknet-53 by integrating YOLOv8's CSPLayer_2Conv (C2f) module for residual connections, while innovatively employing a Spatial-Channel Decoupled Downsampling (SCDown) module to enhance downsampling efficiency. To address redundancy caused by repetitive modules in traditional architectures across stages, the model implements an efficiency-accuracy equilibrium design strategy: it introduces Compact Inverted Residual Blocks (CIB) to optimize fundamental units, and dynamically adjusts network depth through a rank analysis-guided adaptive module configuration scheme. For unified multi-scale feature representation, the model retains YOLOv8's Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fusion (SPPF) module and innovatively appends Position-Sensitive Attention (PSA) after SPPF, effectively enhancing feature expressiveness while maintaining low computational overhead.

The neck adopts an enhanced variant of the Bidirectional Feature Pyramid Network (BiFPN) for multi-scale feature fusion. The feature pyramid network combines deep semantic information with shallow detail features through a top-down propagation path, significantly improving multi-scale target representation via hierarchical feature integration. As a complementary optimization mechanism, a reverse feature fusion pathway establishes a bottom-up propagation channel to refine local detail integration.

The head employs a decoupled prediction structure that separates classification and regression tasks into two independent branches. Each branch contains prediction modules composed of 3×3 and 1×1 convolutions, with dynamic label assignment strategies introduced to optimize positive/negative sample allocation. The anchor-free design eliminates preset anchor boxes from traditional approaches. Convolution-based feature mapping layers directly output target geometry parameters (center coordinates, dimensions) and class probability distributions. This end-to-end prediction mechanism simplifies the detection pipeline while enhancing adaptability to target deformation and scale variations.

However, the YOLOv10 baseline model exhibits limitations in small target detection tasks for drone aerial imagery, with core challenges stemming from insufficient adaptation of feature extraction, feature fusion, and loss function design to aerial scene characteristics. During feature extraction, while YOLOv10 constructs high-level semantic features through deep convolutional networks with progressive downsampling, this process significantly compresses the spatial resolution of feature maps, causing effective pixel information of small targets to nearly vanish in high-level features. In drone imagery, densely distributed small targets (e.g., vehicles, pedestrians) typically occupy only tens of pixels. The large receptive fields of deep networks, though beneficial for large object detection, excessively dilute local detail features of small targets through repeated downsampling, leading to irreversible loss of critical texture and shape information.

Regarding feature fusion mechanisms, although the model achieves multi-scale feature interaction through feature pyramid networks (FPN), it fails to effectively reconcile the conflict between low-semantic shallow features and low-resolution deep features. Aerial target detection requires simultaneous reliance on high-resolution features for precise localization and deep features for contextual reasoning. Existing fusion strategies may inadequately extract multi-scale contextual relationships for small targets due to insufficient response from channel attention mechanisms to low signal-to-noise small target features, or information attenuation during cross-scale feature concatenation.

Furthermore, the loss function design shows bias in small target optimization. Intersection over Union (IoU)-based localization loss demonstrates insufficient sensitivity to coordinate variations in tiny bounding boxes, with gradient updates prone to local optima when target sizes significantly deviate from anchor priors. The dynamic balance mechanism between classification and localization losses also lacks adaptive adjustment for the extreme positive-negative sample imbalance inherent to small targets, causing the model to neglect low-confidence small target predictions. These factors collectively constrain the model's capacity for comprehensive small feature mining and precise regression in aerial scenarios.

3.2. Proposed Method

3.2.1. Overall Network Architecture

Aerial images often contain numerous small targets that occupy limited proportions and pixel compositions in the image, typically exhibiting slender columnar geometric shapes. Current methods primarily rely on convolutional and pooling layers to extract high-level feature information related to targets [

44]. However, as convolutional layers are progressively stacked, feature map dimensions continuously shrink and resolutions degrade, causing small target information to be easily overlooked[

45].

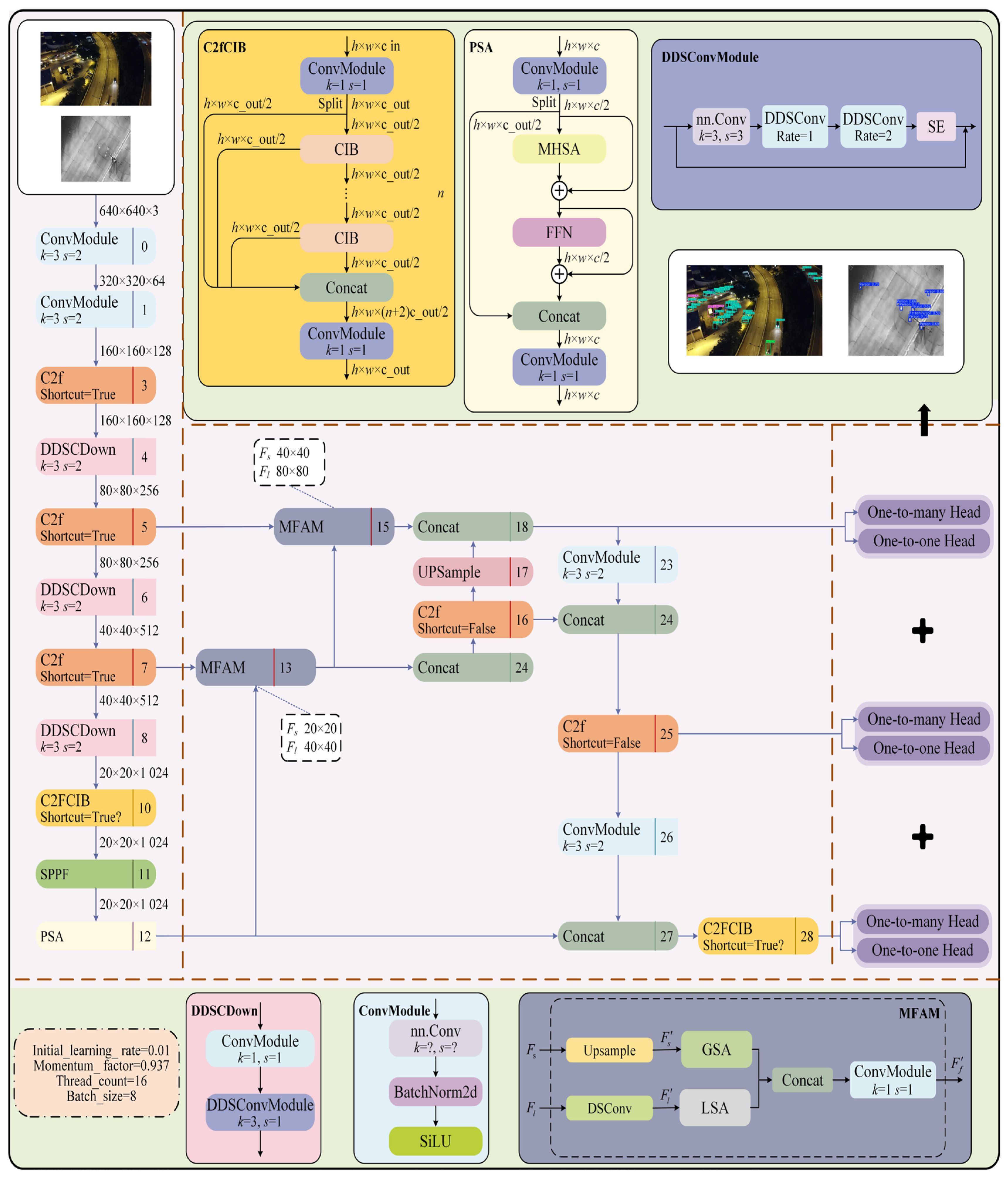

To address the limitations of YOLOv10 in detecting multi-scale targets, this paper proposes an innovative model, DMF-YOLO, designed to enhance the efficiency and accuracy of small target detection. The model improves adaptive multi-scale feature extraction capabilities through several modules. In the backbone, a Dynamic Dilated Snake Convolution (DDSConv) is designed to dynamically adjust the receptive field shape of convolutional kernels, enabling adaptive extraction of local features for multi-scale targets. This capability allows precise capture of critical information, effectively addressing feature extraction challenges in aerial images under conditions of weak local structures, sparse pixels, and complex background interference. For the neck design, a Multi-scale Feature Aggregation Module (MFAM) is constructed to integrate multi-layer feature maps, balancing robust semantic information with rich detail. This dual-branch architecture effectively preserves both local details and global contextual modeling. By introducing a spatial attention mechanism, the module strengthens the kernel's adaptive capacity to detect target-related features across spatial regions, thereby accommodating features of varying sizes and shapes across samples. Building on this, the MFAM-Neck further enhances multi-scale feature fusion, improving the network's perception of objects at different scales. The detection head retains the original YOLOv10 design. The refined network architecture is illustrated in

Figure 2.

3.2.2. Dynamic Dilated Snake Convolution (DDSConv)

Dynamic Snake Convolution effectively enhances perception of geometric structures by adaptively focusing on local features of thin and curved tubular shapes, achieving superior segmentation results in cardiac vessel datasets and the Massachusetts road dataset [

26]. Similar to blood vessels and road networks, drone-observed targets also exhibit slender and highly variable characteristics, with lengths and widths showing complex variations in images [

46]. However, Dynamic Snake Convolution cannot adaptively adjust the receptive field size, making it prone to offset imbalance under extreme scale variations or irregular aerial targets, thereby failing to focus on local features of small targets.To address these issues, we propose the Dynamic Dilated Snake Convolution (DDSConv), which dynamically adjusts the receptive field shape of convolutional kernels based on different dilation rates. Additionally, it adaptively focuses on local features of minute targets to more precisely capture their critical information. This design effectively resolves challenges related to fragile local structures, limited pixel counts, and interference from complex ground background information.

To enable convolutional kernels to more flexibly focus on complex geometric features of targets, DDSConv introduces deformation offsets . However, when the model is allowed to freely select deformation offsets, the receptive field tends to deviate from targets, particularly when processing slender structures. To address this, an iterative process with continuity constraints is implemented to prevent excessive divergence in detection results. During each convolutional operation, the model uses previous positions as references to sequentially select the next observation points, ensuring that attention balances flexibility and continuity for each target being processed. This approach facilitates the extraction of richer critical features and enhances model performance.

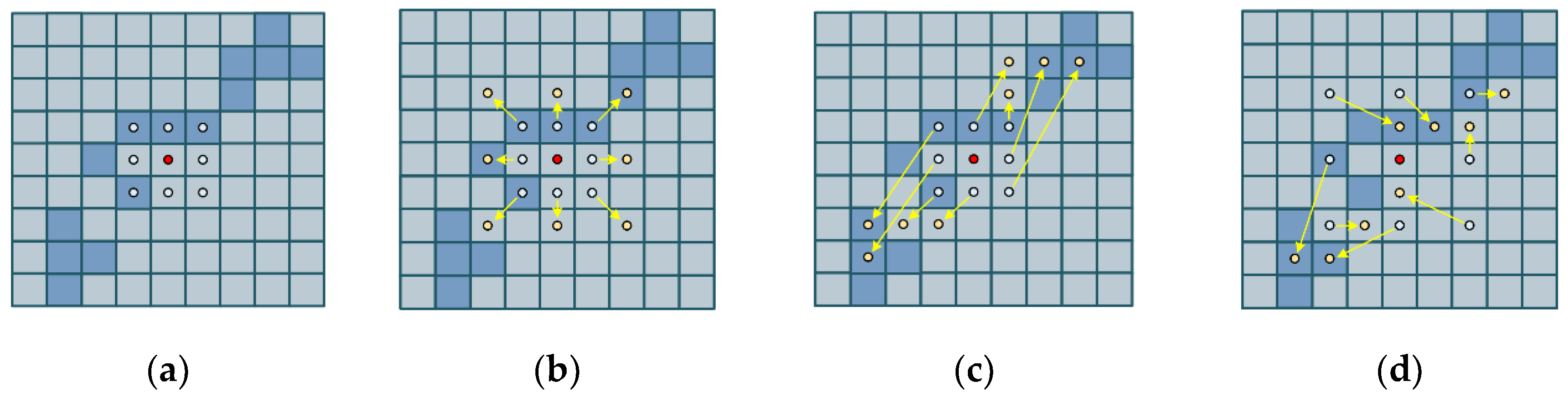

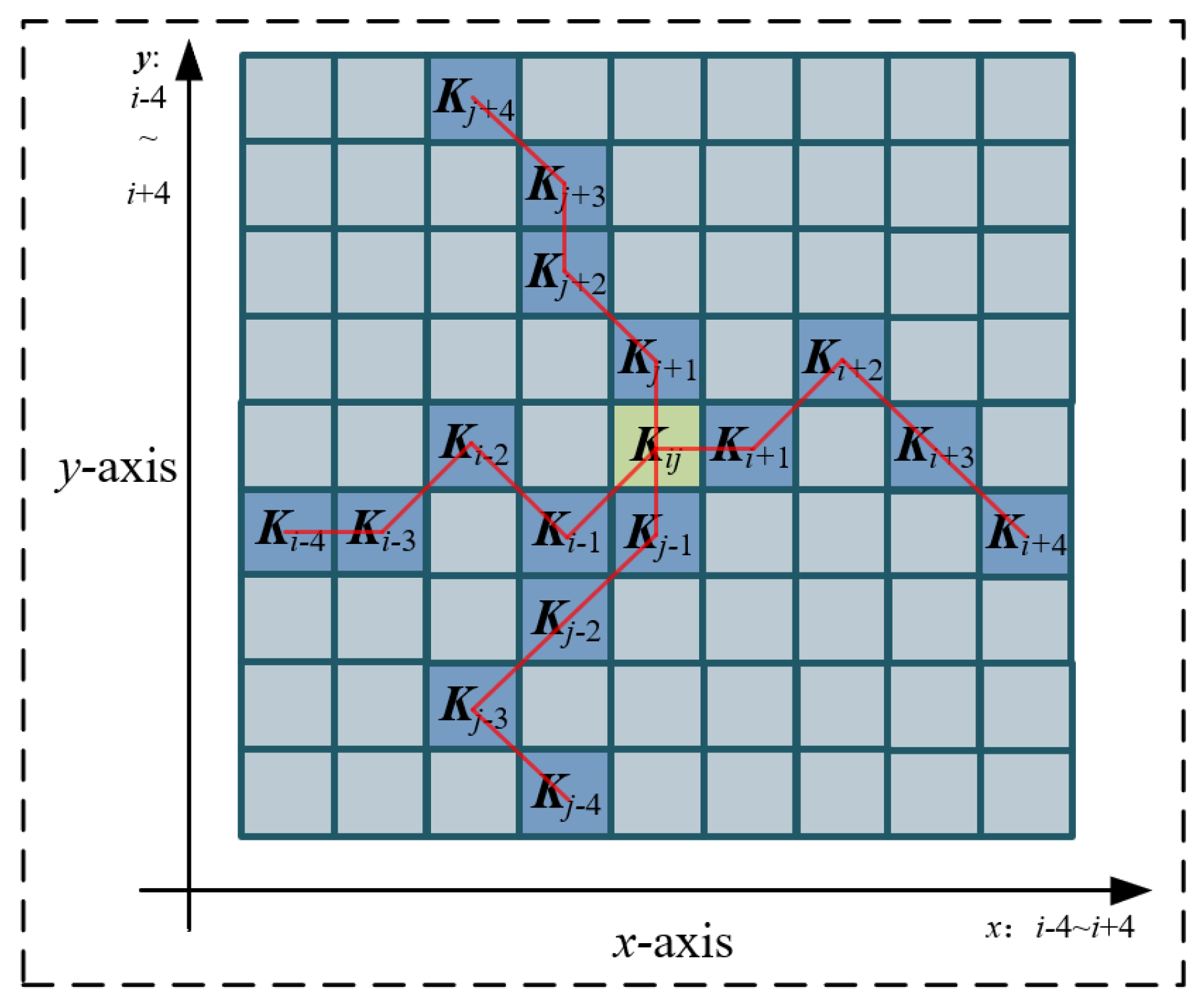

DDSConv samples input feature maps in the form of continuous stochastic grids, with the mathematical principles detailed as follows: Given a standard 2D convolution coordinate system

where the central coordinates are defined as

, and other grid positions are denoted as

,

. The selection of each grid position

in the convolution kernel follows a recursive process. Starting from the central position

, the position of distant grids

depends on the prior grid

. The position of each grid is incrementally adjusted relative to its predecessor by adding an offset

. Given a central distance

, the positional variation of the grid is defined as

. Different types of convolution operations are illustrated in

Figure 3.

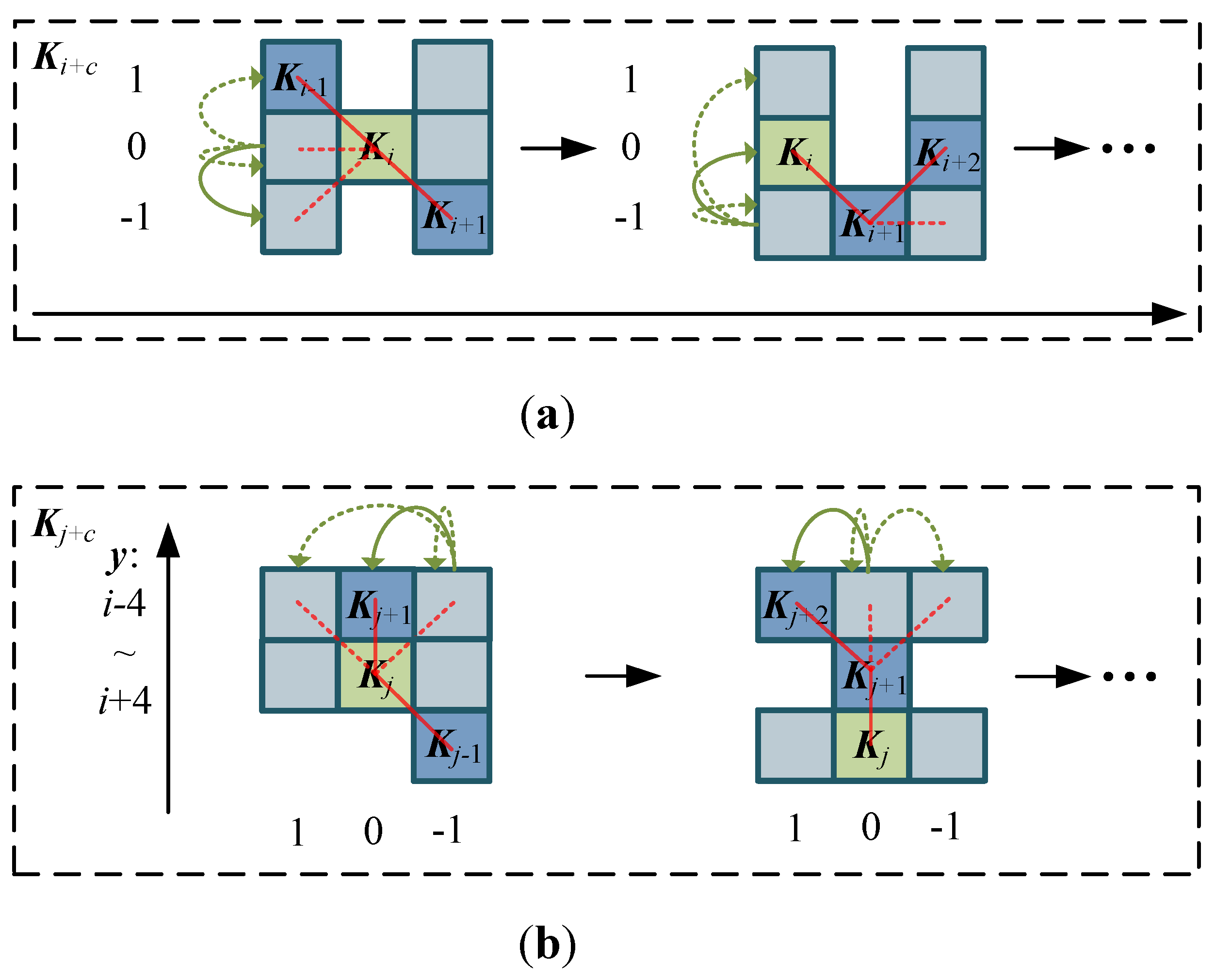

Based on the principles above, the variation of DDSConv in the axis direction is illustrated in

Figure 4(a), with the calculation formula expressed as

where

denotes the summation along the positive semi-axis of the

x-axis,

represents the summation along the negative semi-axis of the

x-axis,

is the kernel size, and

is the dilation factor.

The variation in the

y-axis direction is illustrated in

Figure 4(b), with the calculation formula expressed as

where

denotes the summation along the positive semi-axis of the

y-axis, and

represents the summation along the negative semi-axis of the

y-axis.

According to Equations (1) and (2), an example of the selectable range of receptive fields for the dynamic dilated serpentine convolution kernel during the feature extraction process is illustrated in

Figure 5.

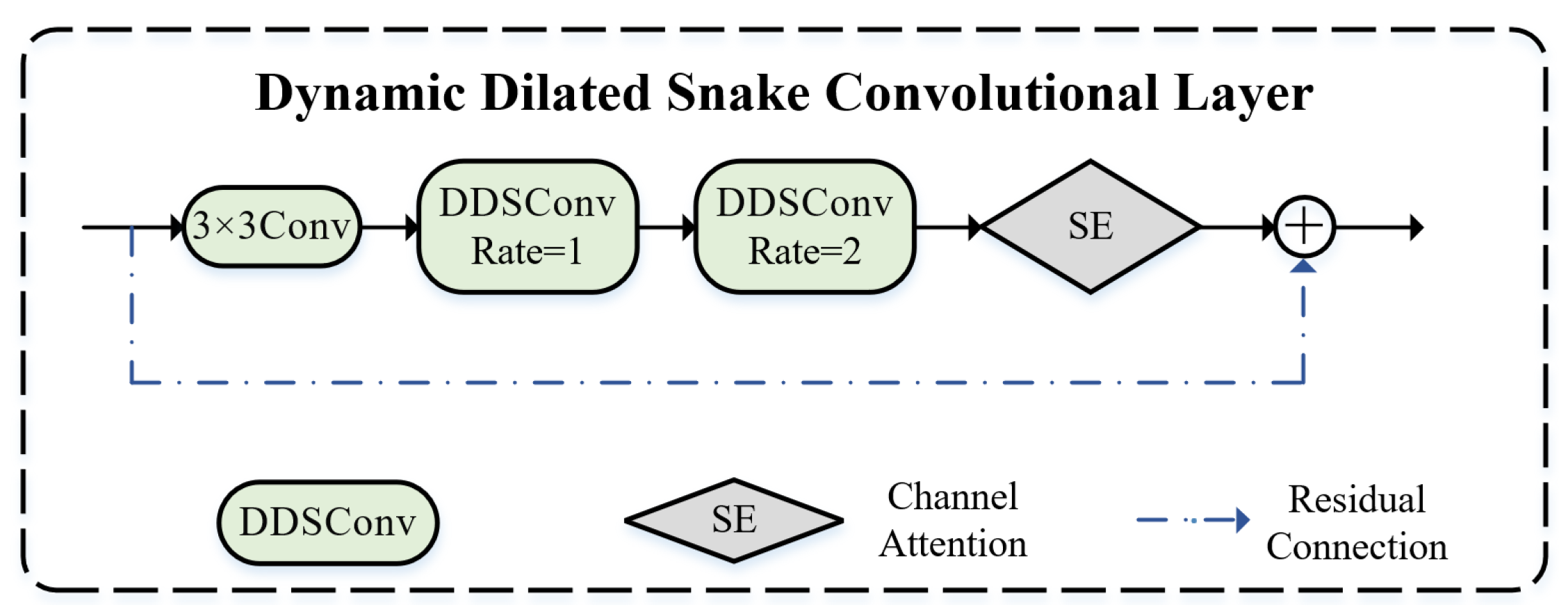

The Dynamic Dilated Snake Convolutional Layer (DDSConv Layer) based on a 3×3 standard convolution architecture is illustrated in

Figure 6. This structure employs two dilation rate parameters (1 and 2) to expand the receptive field. To enhance adaptive feature representation, the design systematically integrates a Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) module and achieves weighted fusion of multi-level features through cross-layer connections. The DDSConv Layer dynamically optimizes the morphological configuration and dilation parameters of the convolution kernel according to input feature characteristics. This dynamic tunability enables the network to capture multi-scale spatial patterns with higher precision, significantly improving the granularity of feature analysis, and demonstrates superior performance in aerial imagery object detection tasks requiring robust handling of complex background interference.

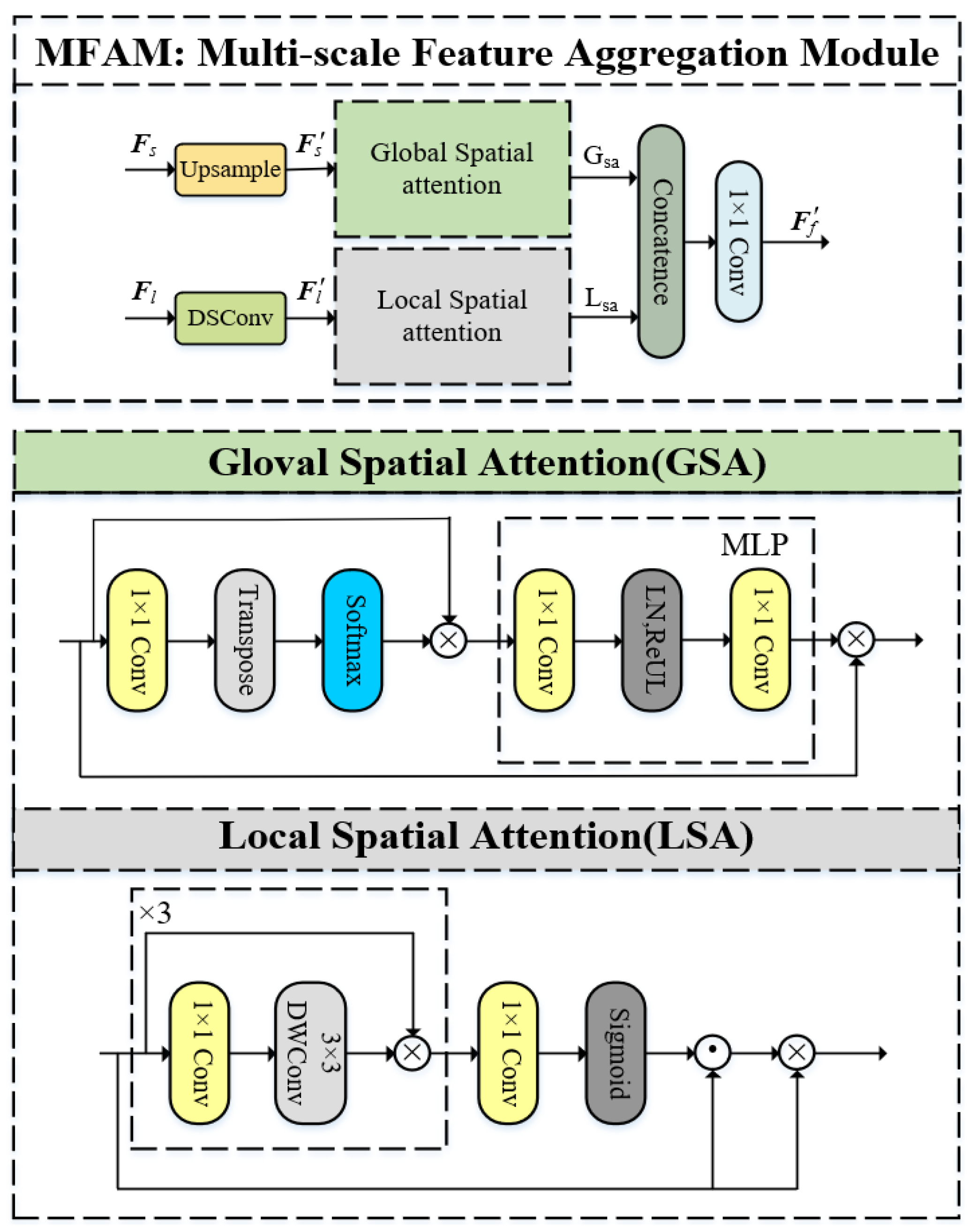

3.2.3. Multi-Scale Feature Aggregation Module (MFAM)

To simultaneously capture deep and shallow spatial features across different hierarchy levels and enable convolutional kernels to adapt to varying contextual environments, this paper proposes a MFAM. By introducing a spatial attention mechanism, the design enhances the kernel's adaptive capability to detect region-specific and target-relevant features at different spatial positions, thereby comprehensively considering global and local features with diverse sizes and shapes across diverse samples. The module incorporates two independent spatial attention units dedicated to processing global and local features respectively, as shown in

Figure 7.

Since shallow feature maps preserve richer local characteristics of multi-scale targets, the global spatial attention unit employs 1×1 small convolutional kernels to meticulously capture global features from shallow layers. In contrast, the local spatial attention unit utilizes 3×3 large convolutional kernels to extract global patterns from deep feature maps. This dual-branch architecture effectively preserves localized details and global contextual modeling, while separated channel dimensions optimize the balance between detection accuracy and computational resources. Finally, the outputs of both attention units are concatenated and processed through a 1×1 convolutional layer, with the mathematical formulation of this operation defined as:

where

denotes the feature map split operation.

represents the output concatenation operation.

corresponds to the pointwise convolution using a 1×1 kernel.

denotes the global spatial attention and

indicates the local spatial attention.

The GSA module focuses on long-range dependencies between pixels, serving as a complementary mechanism to local spatial attention. By capturing these long-range interactions, it significantly enhances the representational capacity of features. Let X be the input feature map. The process for generating global spatial attention is defined as follows:

where

denotes the global attention operator.

represents the Softmax activation function.

corresponds to the transpose operation.

is composed of two pointwise convolution layers, a ReLU nonlinear activation function, and a fully connected layer.

indicates the matrix multiplication operation.

The LSA module focuses more on local features within the spatial dimensions of a given feature map. Using the sub-feature map

as input, the calculation formula is defined as:

where

denotes the local attention operator.

represents the Sigmoid activation function.

consists of three stacked 1×1 convolutional layers and a 3×3 depthwise separable convolution layer.

indicates element-wise matrix multiplication. This structural design efficiently focuses on local spatial information with fewer parameters.

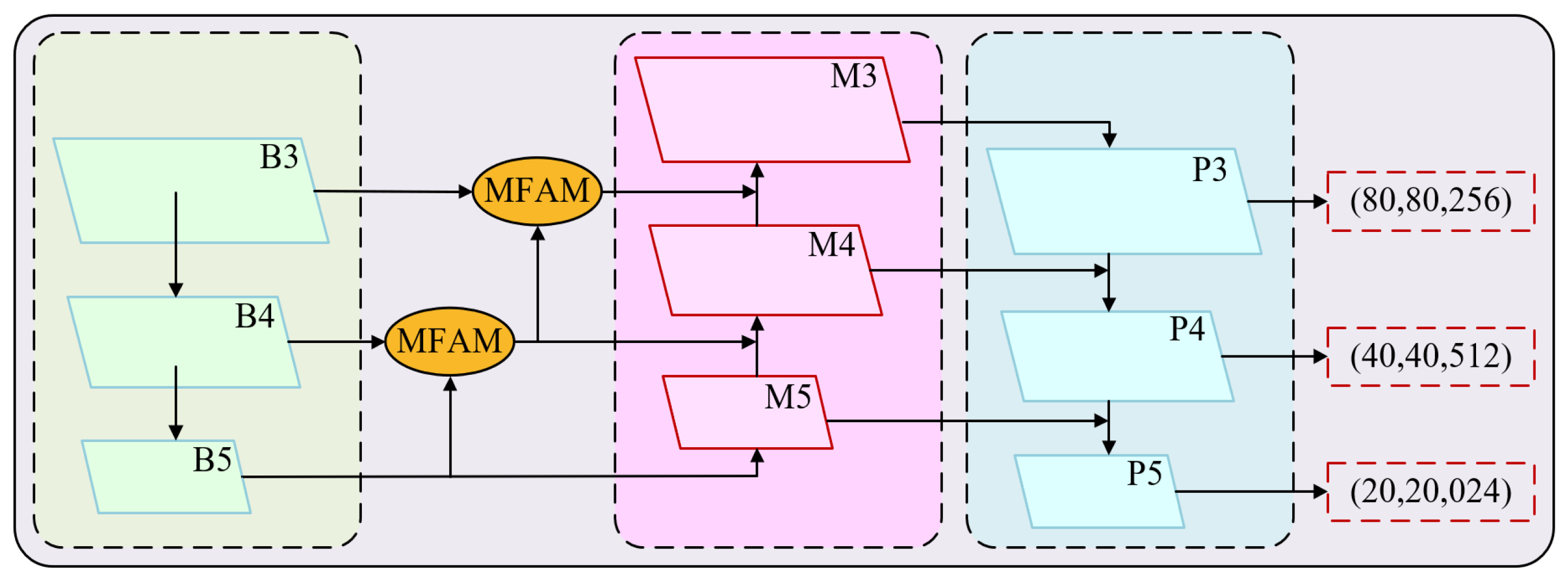

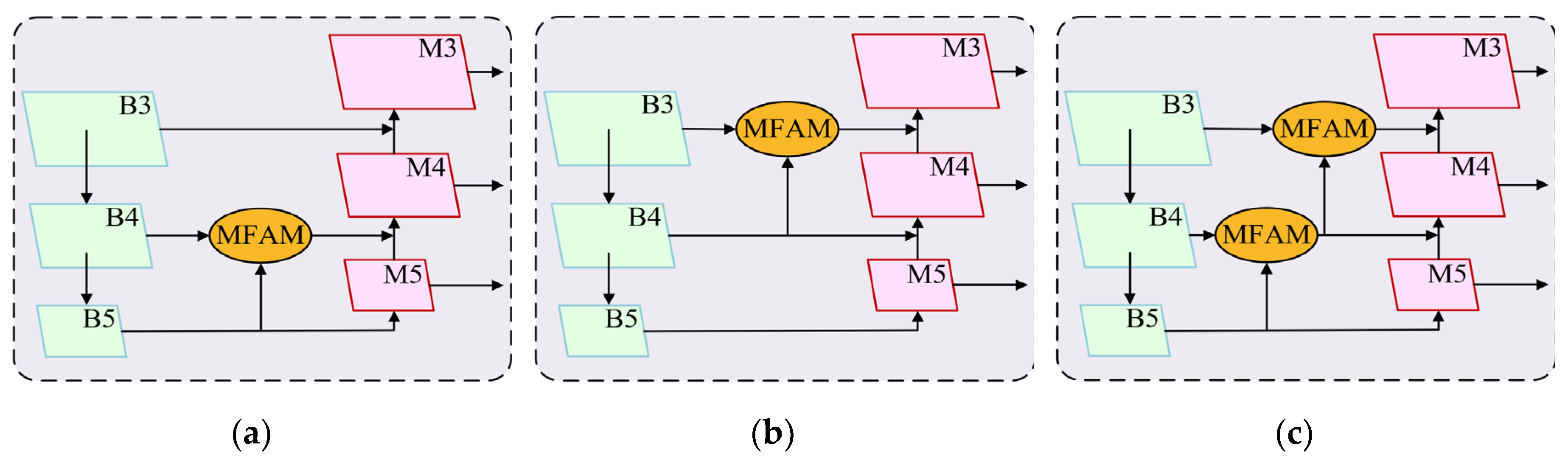

3.2.4. MFAM-Neck

In drone-captured images, target scale variations are often highly significant, with a prevalence of small-sized targets. To address these challenges in target detection, this paper proposes a novel MFAM-Neck framework, designed to adapt to hierarchical contextual environments. This framework effectively integrates shallow-layer features and deep-layer features from multi-scale feature maps. By leveraging the MFAM module to reconstruct fused feature information, MFAM-Neck provides high-quality feature support for target detection. The detailed architecture of the MFAM-Neck network is illustrated in

Figure 8.

The MFAM-Neck feature fusion network adopts a multi-scale fusion strategy, enhancing feature representation by integrating B3, B4, and B5 feature maps from different hierarchical layers of the backbone network. Given their distinct receptive fields and semantic abstraction levels, the network incorporates a MFAM in the Neck section. This module achieves effective feature fusion across dual-scale spatial features through an adaptive weight allocation mechanism. Specifically, the network employs bidirectional feature propagation paths, including top-down feature propagation and bottom-up feature aggregation. After multi-level feature fusion, the final output feature maps P3, P4, and P5 have dimensions of 80×80×256, 40×40×512, and 20×20×1024, respectively, reflecting multi-scale feature representations.

3.2.5. Loss Functions

The complex structures, background textures, and noise in drone aerial images often interfere with target localization and recognition, thereby degrading detection accuracy. By rationally designing the loss function, model convergence can be accelerated and regression performance improved. YOLOv8 introduces Distribution Focal Loss (DFL) and CIoU to evaluate bounding box regression losses. Although CIoU accounts for the center distance and aspect ratio between boxes, its aspect ratio is defined as a relative value rather than an absolute value, leading to suboptimal balancing of difficulty levels across different samples. Additionally, the use of inverse trigonometric functions in its calculation may increase computational overhead.

To address these issues and further accelerate model convergence, this paper introduces the concept of Inner-IoU, which employs auxiliary bounding boxes to enhance convergence, and proposes an Expanded-Window Bounding Box Regression Loss Function (EW-BBRLF). The core idea of EW-BBRLF is to improve bounding box regression through anchor box expansion and minimum point distance optimization. Building on the strengths of CIoU and Ln-norm loss, EW-BBRLF introduces a scaling factor to control the size of auxiliary bounding boxes, thereby enhancing localization precision and detection accuracy.

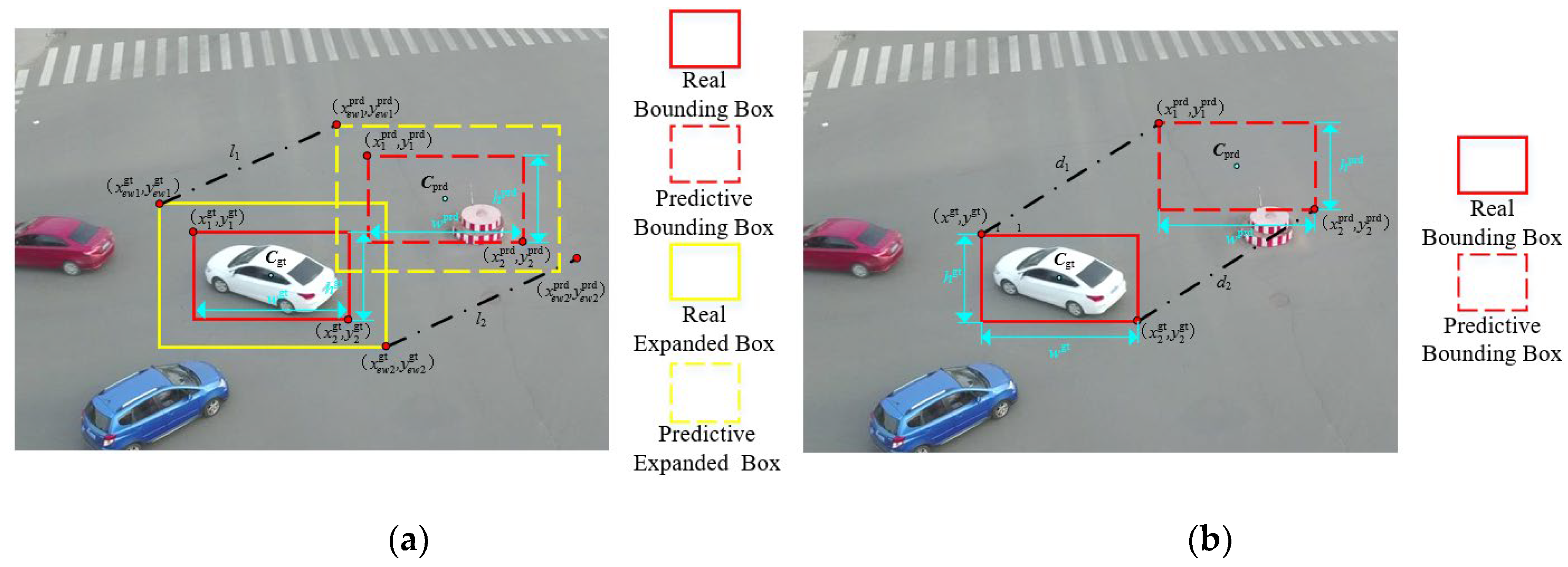

EW-BBRLF employs larger auxiliary bounding boxes when calculating IoU loss, effectively promoting regression for low-IoU samples and accelerating model convergence. Conversely, smaller auxiliary boxes aid in precise localization of high-IoU samples. However, small aerial targets often exhibit low IoU values due to their tiny size and insufficient feature information. Thus, leveraging large-scale expanded windows significantly improves bounding box regression accuracy for small targets. A comparative visualization of EW-BBRLF and CIoU is shown in

Figure 9.

Given the coordinates of the predictive bounding box

coordinates of the real bounding box

coordinates of the centre of the predictive bounding box

coordinates of the centre of the real bounding box

predictive box width, height

real box width, height

then the predicted expanded box is

where,

and

represent the top-left corner coordinate and bottom-right corner coordinate of the predicted expanded window, respectively. The calculation formula is defined as:

where

is the scaling factor to control the size of the expanded window, which is set to 1.2. Similarly, the true expanded window can be derived as:

The IoU of the bounding boxes is

where

denotes the overlapping area between the predicted bounding box and ground truth bounding box, calculated as

Similarly, the IoU of the expanded window is

The minimum-point-distance-based expanded window IoU is

where

and

represent the width and height of the image, respectively.

The loss function incorporating the expanded window is

Finally, the EW-BBRLF calculation formula is defined as

EW-BBRLF comprehensively integrates factors including aspect ratio differences, center point distance, and overlapping regions, while streamlining computational processes. This effectively addresses limitations inherent in the CIoU method. Furthermore, by controlling the scaling factor to generate larger expanded windows, EW-BBRLF mitigates challenges arising from small target sizes and insufficient feature information, significantly enhancing detection performance for small targets.

5. Conclusions

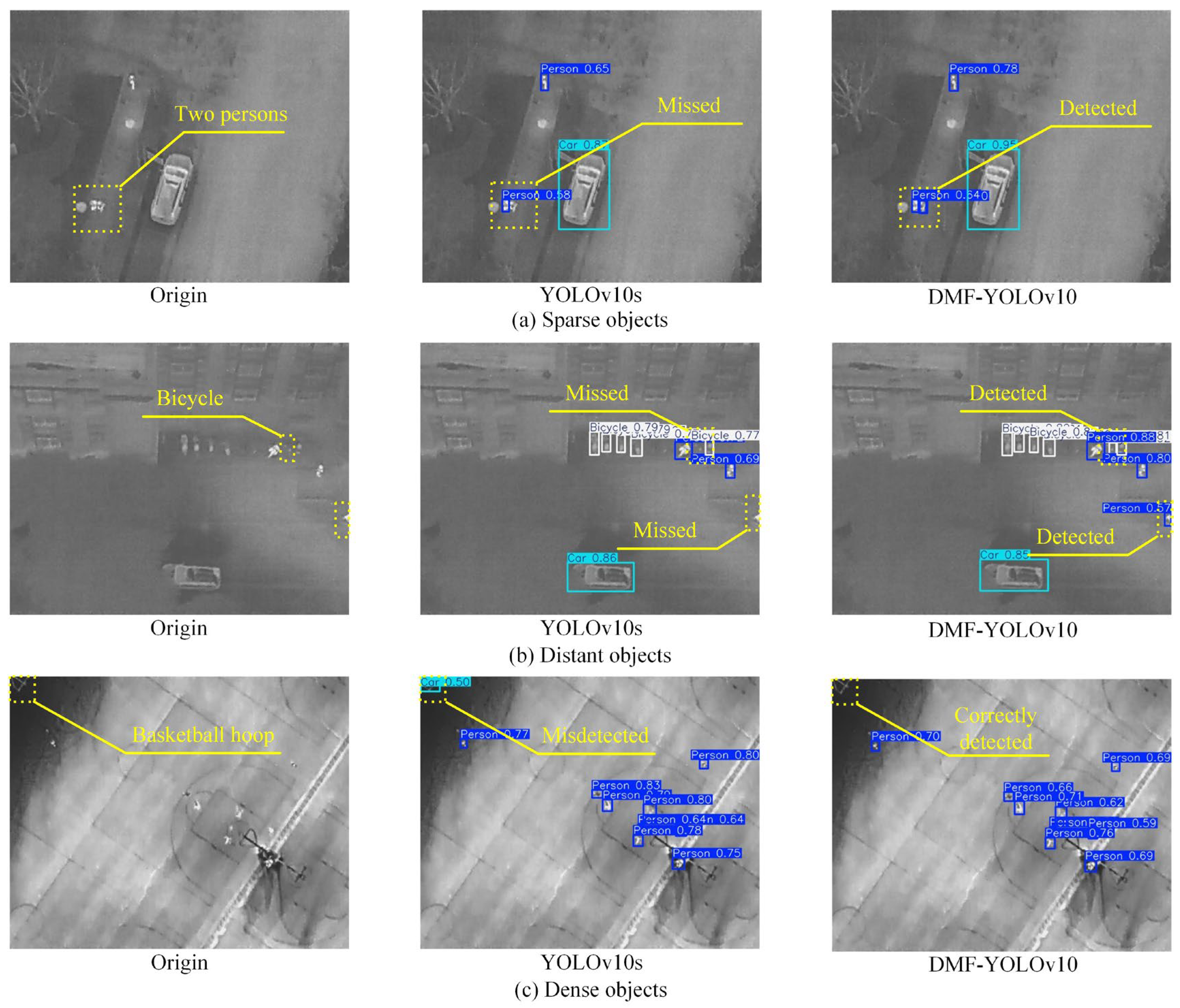

This paper proposes DMF-YOLO, an improved algorithm based on the YOLOv10 framework, to address the challenges of small target detection in UAV aerial images. By introducing Dynamic Dilated Snake Convolution (DDSConv), a Multi-scale Feature Aggregation Module (MFAM), and an Expanded Window-based Bounding Box Regression Loss Function (EW-BBRLF), the model significantly enhances detection capabilities for multi-scale targets, particularly micro-objects. Experimental results demonstrate that DMF-YOLO achieves 50.1% and 81.4% mAP50 on the VisDrone and HIT-UAV datasets, respectively, surpassing the baseline YOLOv10s by 27.1% and 2.6%, while increasing parameters by only 24.4% and 11.9%, validating the algorithm's balanced advantage between accuracy and efficiency. Visualization analyses further confirm the model's enhanced robustness in dense scenes, complex backgrounds, and long-distance scenarios, with notable improvements in small target feature extraction and localization precision.

Although DMF-YOLO achieves a favorable trade-off between parameter count and detection speed, computational overhead from dynamic convolution and multi-scale fusion modules remains a challenge. Future work may explore model compression techniques such as knowledge distillation, channel pruning, or dynamic network architecture design to meet real-time processing requirements on UAV edge devices. Additionally, UAVs often employ multimodal sensors (e.g., visible-light and infrared). Future research could investigate detection frameworks integrating multispectral or thermal imaging data to improve target recognition under complex lighting and adverse weather conditions.

Figure 1.

YOLOv10 network structure.

Figure 1.

YOLOv10 network structure.

Figure 2.

DMF-YOLO network structure.

Figure 2.

DMF-YOLO network structure.

Figure 3.

Different types of convolution operations. (a) Conv; (b) DConv; (c) DSConv; (d) DDSConv.

Figure 3.

Different types of convolution operations. (a) Conv; (b) DConv; (c) DSConv; (d) DDSConv.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the convolution kernel computed along the x- and y-axis directions. (a) x-axis; (b) y-axis.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the convolution kernel computed along the x- and y-axis directions. (a) x-axis; (b) y-axis.

Figure 5.

DDSConv feeling the range of wild options.

Figure 5.

DDSConv feeling the range of wild options.

Figure 6.

DDSConv Layer structure.

Figure 6.

DDSConv Layer structure.

Figure 7.

MFAM structure.

Figure 7.

MFAM structure.

Figure 8.

MFAM-Neck structure.

Figure 8.

MFAM-Neck structure.

Figure 9.

Comparison of EW-BBRLF and CIoU. (a) EW-BBRLF; (b) CIoU.

Figure 9.

Comparison of EW-BBRLF and CIoU. (a) EW-BBRLF; (b) CIoU.

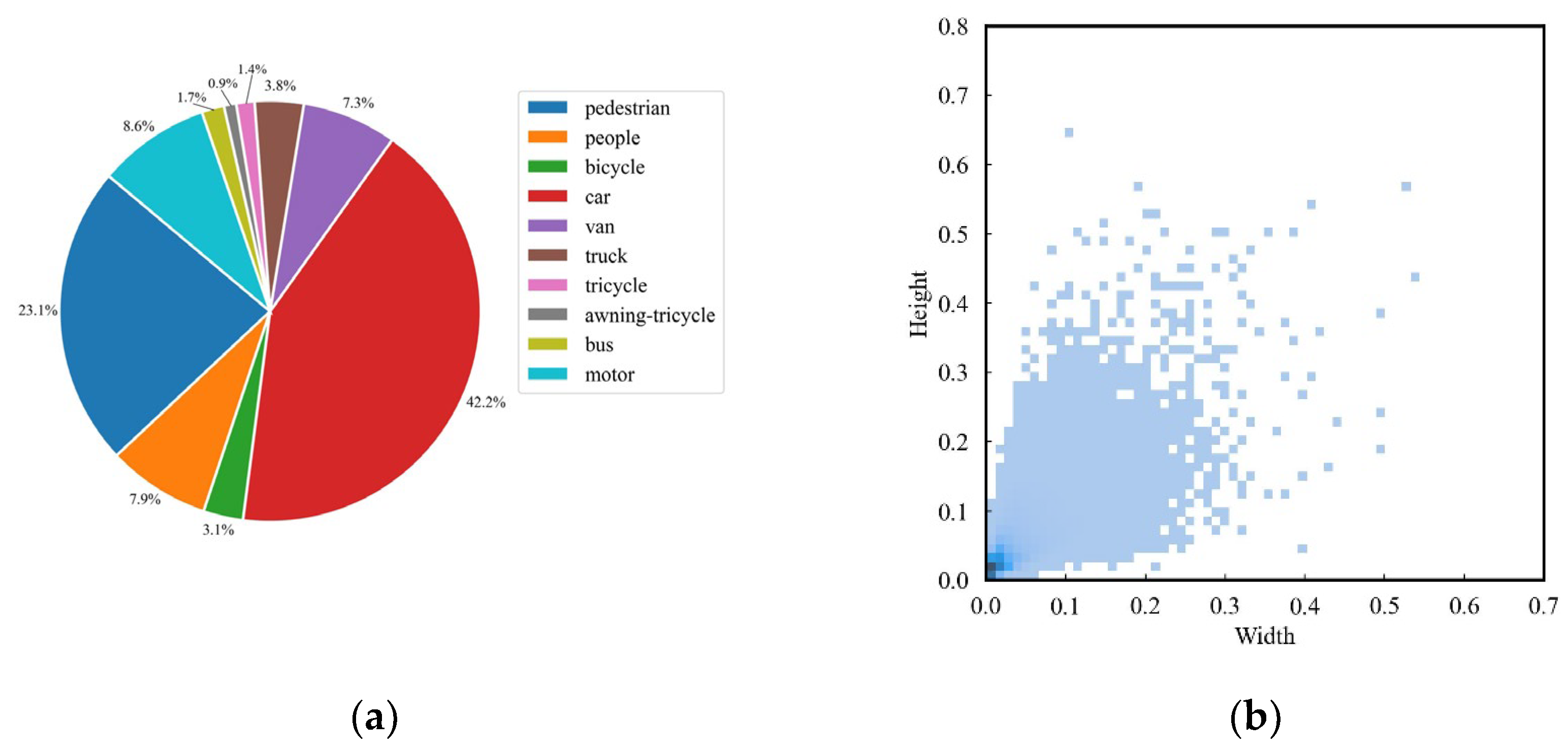

Figure 10.

Object type and size distribution of the VisDrone dataset. (a) Types of objects; (b) Object size distribution.

Figure 10.

Object type and size distribution of the VisDrone dataset. (a) Types of objects; (b) Object size distribution.

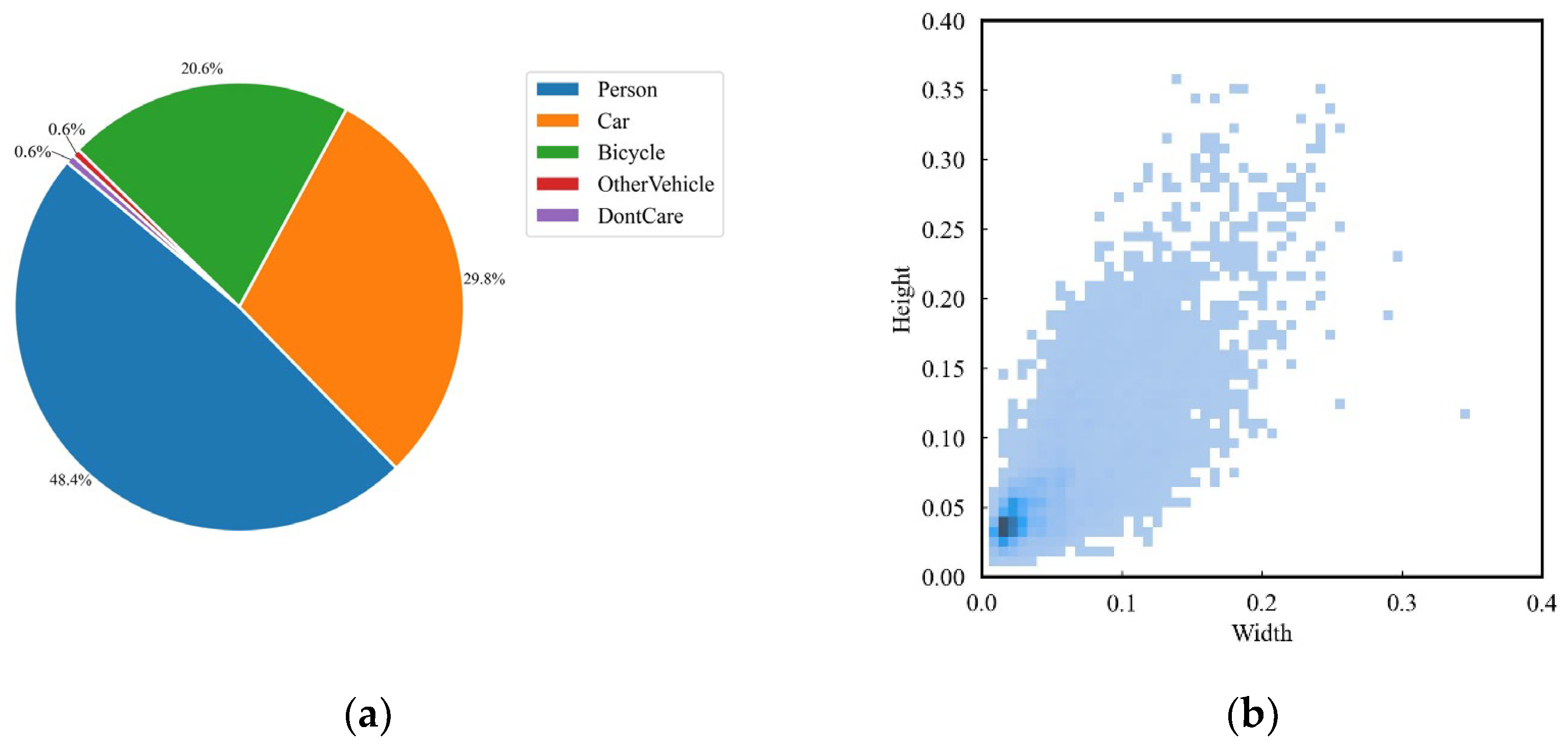

Figure 10.

Object type and size distribution of the HIT-UAV dataset. (a) Types of objects; (b) Object size distribution.

Figure 10.

Object type and size distribution of the HIT-UAV dataset. (a) Types of objects; (b) Object size distribution.

Figure 12.

Detailed Structures of the Three MFAM-Neck Variants. (a) MFAM-Neck-A; (b) MFAM-Neck-B; (c) MFAM-Neck-C.

Figure 12.

Detailed Structures of the Three MFAM-Neck Variants. (a) MFAM-Neck-A; (b) MFAM-Neck-B; (c) MFAM-Neck-C.

Figure 13.

Comparison of object detection in different scenes.

Figure 13.

Comparison of object detection in different scenes.

Figure 14.

Comparison of object detection in different scenes.

Figure 14.

Comparison of object detection in different scenes.

Figure 15.

Comparison of heat maps in scenes with distant objects.

Figure 15.

Comparison of heat maps in scenes with distant objects.

Figure 16.

mAP50 Comparisons of Different Models Across Categories.

Figure 16.

mAP50 Comparisons of Different Models Across Categories.

Figure 17.

Comparison of detection effect in different scenes.

Figure 17.

Comparison of detection effect in different scenes.

Table 1.

Training Hyperparameters.

Table 1.

Training Hyperparameters.

| Name |

Value |

Name |

Value |

| Optimizer |

SGD |

Training Epochs |

150 |

| Image Size |

640×640;512×512 |

Workers |

16 |

| Initial Learning Rate |

0.01 |

Learning Rate Decay |

0.0001 |

| Weight Decay |

0.0005 |

Batch Size |

8 |

| Momentum Factor |

0.937 |

Warmup Epochs |

3 |

Table 2.

Single-Module Ablation Experiments.

Table 2.

Single-Module Ablation Experiments.

| DDSConv |

MFAM |

EW-BBRLF |

P(%) |

R(%) |

mAP50(%) |

mAP50:95(%) |

Par(M) |

| - |

- |

- |

49.3 |

38.6 |

39.5 |

22.8 |

13.3 |

|

|

|

52.3 |

39.4 |

42.0 |

23.1 |

15.1 |

| |

|

|

54.0 |

42.2 |

44.3 |

25.4 |

18.6 |

| |

|

|

49.8 |

39.7 |

40.6 |

23.4 |

11.3 |

Table 3.

Multi-Module Ablation Experiments.

Table 3.

Multi-Module Ablation Experiments.

| DDSConv |

MFAM |

EW-BBRLF |

P(%) |

R(%) |

mAP50(%) |

mAP50:95(%) |

Par(M) |

| - |

- |

- |

49.3 |

38.6 |

39.5 |

22.8 |

13.3 |

|

|

|

52.3 |

39.4 |

42.0 |

23.1 |

15.1 |

|

|

|

58.2 |

46.1 |

48.3 |

30.4 |

21.6 |

|

|

|

54.6 |

43.2 |

45.8 |

27.4 |

15.1 |

| |

|

|

57.9 |

44.2 |

46.5 |

28.3 |

18.6 |

|

|

|

60.4 |

48.6 |

51.9 |

31.7 |

21.6 |

Table 4.

Experimental Comparison Results of the Three MFAM-Neck Variants.

Table 4.

Experimental Comparison Results of the Three MFAM-Neck Variants.

| Method |

mAP50(%) |

mAP50:95(%) |

Par(M) |

| YOLOv10s |

39.5 |

22.8 |

11.3 |

| YOLOv10l |

44.5 |

25.7 |

30.5 |

| MFAM-Neck-A |

42.3 |

24.5 |

15.8 |

| MFAM-Neck-B |

42.9 |

24.9 |

15.6 |

| MFAM-Neck-C |

44.3 |

25.4 |

18.6 |

Table 5.

Comparative Experimental Results of Different Methods.

Table 5.

Comparative Experimental Results of Different Methods.

| Method |

AP(%)

|

m1(%)

|

P(%)

|

R(%)

|

m2(%)

|

Par(M)

|

| Ped |

Peo |

Bic |

Car |

Van |

Tru |

Tri |

Awn |

Bus |

Mot |

all |

|

|

|

|

| RetinaNet |

13.0 |

7.9 |

1.4 |

45.5 |

19.9 |

11.5 |

6.3 |

4.2 |

17.8 |

11.8 |

13.9 |

37.5 |

28.4 |

12.0 |

15.8 |

| CenterNet |

22.6 |

20.6 |

14.6 |

59.7 |

24.0 |

21.3 |

20.1 |

17.4 |

37.9 |

23.7 |

26.2 |

39.8 |

30.3 |

14.3 |

19.1 |

| QueryDet |

56.8 |

37.4 |

17.6 |

80.3 |

41.9 |

41.8 |

24.2 |

10.1 |

62.1 |

44.8 |

41.7 |

48. 3 |

37.1 |

21.2 |

35.6 |

| YOLOv5s |

37.9 |

31.5 |

12.8 |

70.4 |

34.2 |

31.7 |

18.7 |

12.6 |

41.1 |

37.2 |

32.8 |

42.4 |

33.6 |

17.6 |

7.2 |

| MCA-YOLOv5 |

42.0 |

27.8 |

18.1 |

81.6 |

47.1 |

52.0 |

26.8 |

25.3 |

63.2 |

43.1 |

42.7 |

- |

- |

28.3 |

31.8 |

| YOLOv8s |

42.7 |

32.6 |

14.2 |

80.6 |

44.4 |

46.8 |

28.2 |

23.1 |

55.7 |

44.5 |

41.2 |

49.6 |

41.7 |

23.1 |

18.6 |

| YOLOv10s |

43.2 |

32.6 |

12.9 |

79.5 |

46.1 |

36.3 |

28.6 |

15.6 |

54.8 |

45.4 |

39.5 |

49.3 |

38.6 |

22.8 |

13.3 |

DAMO-

YOLOv10 |

50.8 |

43.8 |

26.0 |

81.1 |

53.7 |

49.9 |

41.8 |

27.9 |

67.1 |

53.3 |

47.5 |

55.9 |

43.2 |

25.4 |

16.4 |

| CA-YOLO |

55.5 |

45.8 |

23.5 |

85.5 |

52.7 |

42.1 |

38.2 |

22.3 |

64.6 |

57.5 |

48.8 |

62.1 |

45.1 |

27.6 |

31.1 |

| ours |

56.6 |

47.4 |

24.6 |

87.5 |

53.1 |

41.7 |

39.8 |

25.4 |

65.9 |

59.7 |

50.1 |

60.4 |

48.6 |

29.7 |

17.6 |

| Note: m1 is the mAP50 indicator and m2 is the mAP50:95 indicator. |

Table 6.

Test results of different models.

Table 6.

Test results of different models.

| Method |

mAP50(%) |

mAP50:95(%) |

Par(M) |

Test Speed (ms) |

| YOLOv5s |

77.2 |

47.9 |

15.6 |

4.8 |

| YOLOv8s |

80.1 |

49.3 |

18.2 |

5.6 |

| YOLOv10s |

79.3 |

49.5 |

12.5 |

3.8 |

| YOLOv10l |

80.6 |

50.9 |

43.2 |

13.6 |

| CA-YOLOv10 |

81.1 |

51.4 |

23.5 |

8.9 |

| Ours |

81.4 |

52.8 |

14.2 |

4.5 |