4.1. Dataset Description

To evaluate the proposed method, we employ two publicly available datasets.

The

SSDD dataset [

40] contains a wide variety of maritime scenes, including port terminals, offshore waters, and open seas, with ship types ranging from small fishing boats to large container ships and tankers. Each image is standardized to a size of

pixels, with spatial resolutions spanning 3 m, 5 m, 8 m, and 10 m. The dataset is divided into training and testing sets in an 8:2 ratio. Annotations follow the

PASCAL VOC format, ensuring compatibility with common object detection pipelines and enabling consistent evaluation across experiments.

The

iVision-MRSSD dataset [

41] consists of 11,590 SAR image tiles, each of size

pixels. The images are acquired from six distinct satellite sensors, providing a wide range of spatial resolutions and imaging geometries. This multi-sensor diversity ensures coverage of varied maritime conditions, from open seas to cluttered coastal zones. The dataset includes both inshore (3,605) and offshore (7,985) scenes, as well as negative examples (images without ships) to improve background discrimination. On average, each image contains 2.4 ships, enabling both single-target and multi-target detection evaluation. The dataset is split into training (70%), validation (10%), and testing (20%) subsets, supporting robust model development and fair benchmarking.

A detailed comparison of the two datasets is provided in

Table 1.

4.2. Implementation Settings

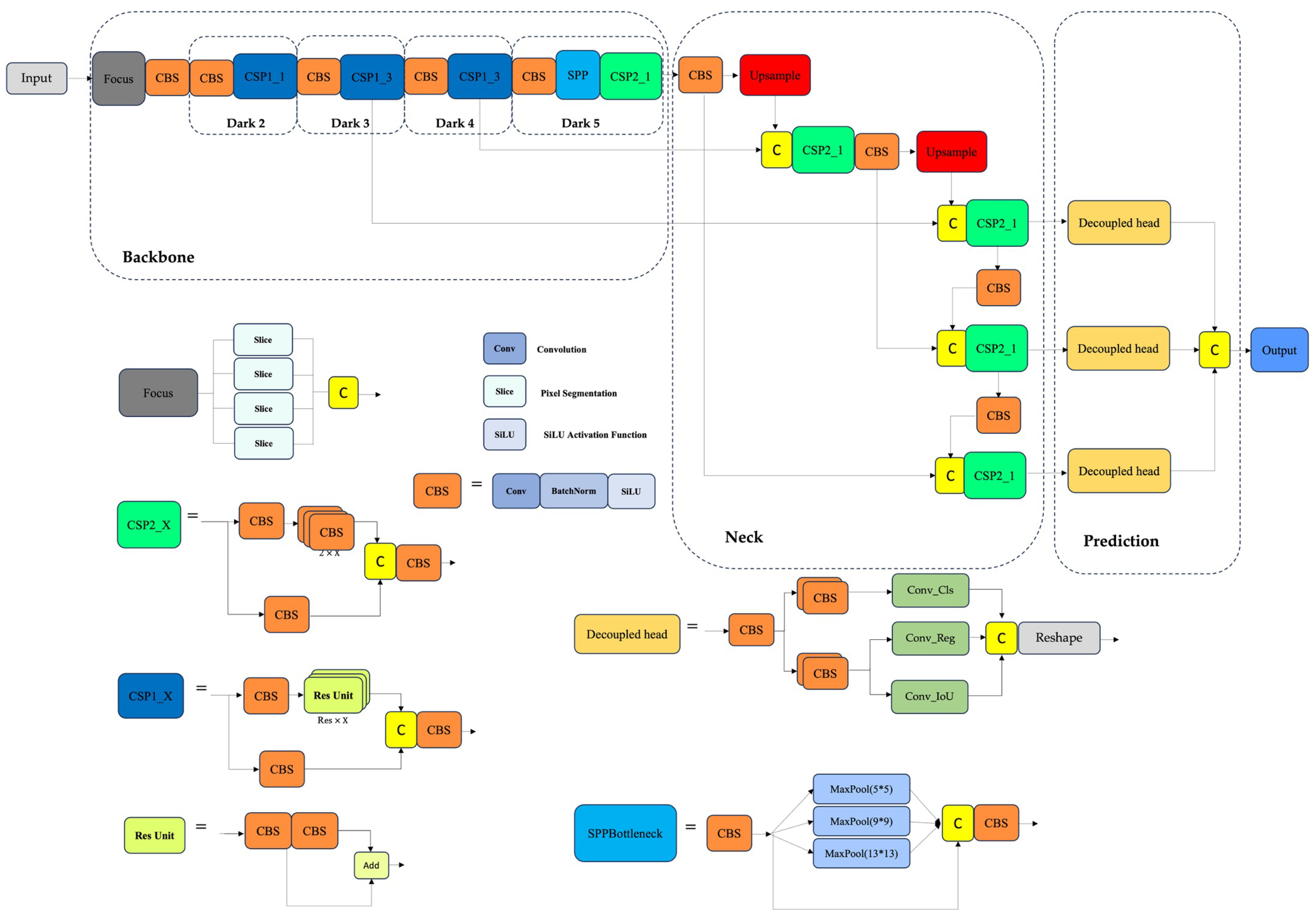

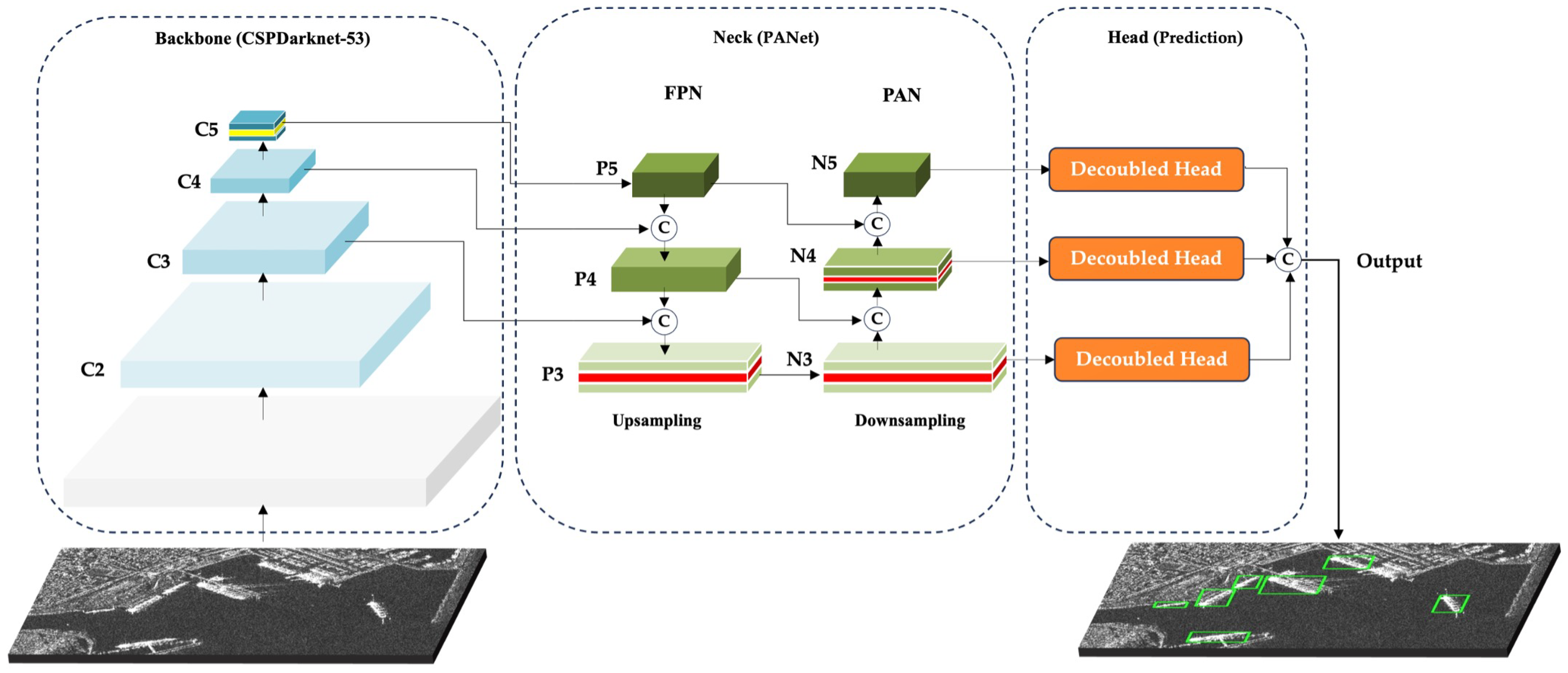

Since the SSDD dataset contains a relatively limited number of images, we adopt a transfer learning strategy by initializing the network with weights pre-trained on large-scale datasets. This enables the model to acquire general visual representations, thereby facilitating faster convergence and improved performance on the SAR-specific ship detection task. The baseline architecture is YOLOX-Tiny, configured with a depth multiplier of 0.33 and a width multiplier of 0.375, resulting in a compact network with approximately5.05M parameters.

All experiments were carried out on a Linux platform using PyTorch 2.0 and CUDA versions 11.x–12.x, with an NVIDIA Tesla T4 GPU (16 GB). The input resolution was fixed at pixels. Training was performed for 96 epochs, organized into four cycles of 24 epochs each, with a 5-epoch warm-up. Early stopping was applied with a patience of 12 epochs to mitigate overfitting.

Optimization was conducted using AdamW with an initial learning rate of (scaled by batch size) and a weight decay of 0.05. A cosine annealing schedule was employed for dynamic learning rate adjustment. Data augmentation strategies included Mosaic (1.0), MixUp (0.3), and horizontal flipping (0.5). Evaluation was carried out every two epochs with a confidence threshold of 0.5. To ensure reproducibility, all experiments used a fixed random seed (42) and four data loading workers.

4.3. Evaluation Indicators

To comprehensively assess the detection performance of the proposed model, we employ a set of standard evaluation metrics widely used in object detection research. These include accuracy indicators and multi-scale precision analyses tailored for SAR ship detection.

Precision (P) is defined as the ratio of correctly predicted positive samples—true positives (TP), to all samples predicted as positive, including false positives (FP). It reflects the model’s ability to minimize false alarms and is particularly critical in reducing false detections under cluttered SAR backgrounds:

Recall (R) measures the proportion of actual positive samples correctly identified by the model. It captures the model’s capacity to detect all relevant targets:

Precision and recall together provide a nuanced view of detection quality, especially important in maritime SAR scenarios where objects may be sparse or embedded in noisy backgrounds. The

F1 score, defined as the harmonic mean of

P and

R, offers a comprehensive measure of a model’s classification performance:

Average Precision (AP) measures the area under the precision–recall (PR) curve, evaluating the trade-off between precision and recall across confidence levels:

In this study, we report (computed at a fixed Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5) and the more comprehensive , averaged over multiple IoU thresholds from 0.5 to 0.95 in 0.05 increments. Additionally, we report , , and , corresponding to the model’s performance on small, medium, and large ship targets, respectively.

Intersection over Union (IoU) is a standard metric used to evaluate the accuracy of object detection models by comparing predicted bounding boxes to ground truth:

where

is the predicted bounding box, and

is the ground truth. A higher IoU indicates better localization accuracy.

Furthermore, computational efficiency is assessed using the number of parameters (

Params) and the number of floating-point operations (

FLOPs). The total parameter count is the sum across all layers. For a convolutional layer, it is given by:

where

and

denote kernel height and width,

is the number of input channels, and

is the number of output channels.

4.4. Ablation Experiments: Results and Analysis

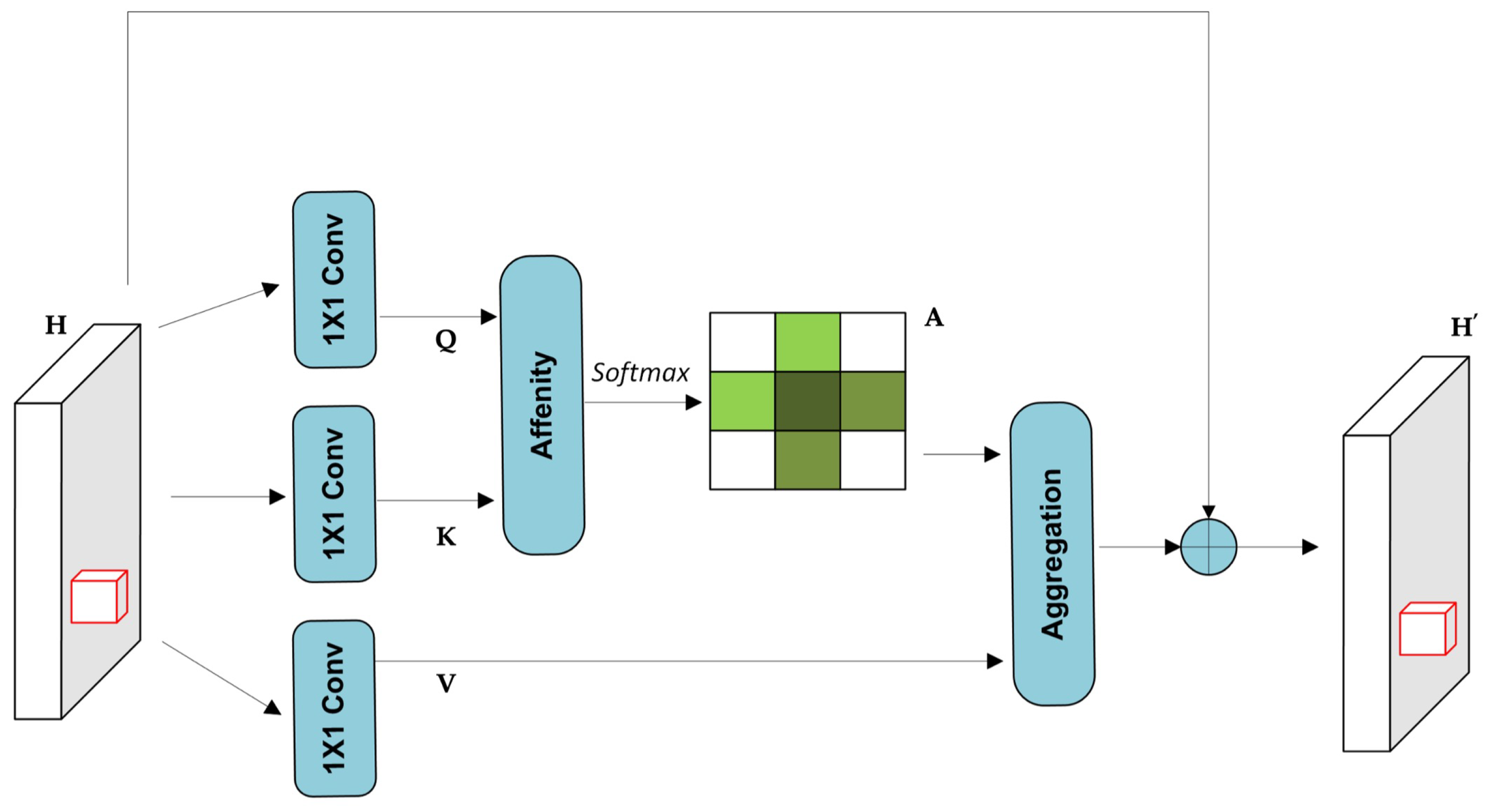

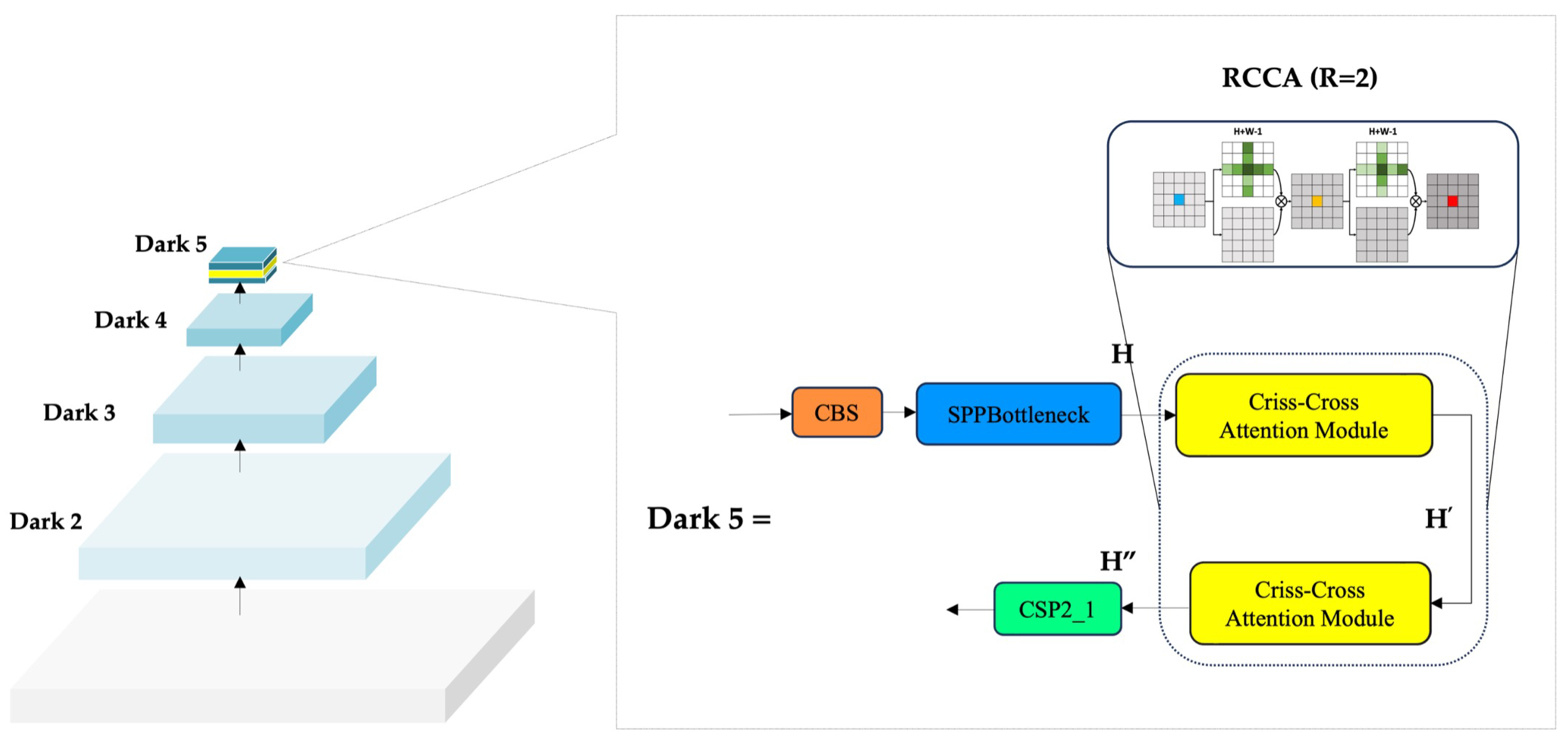

To ensure a principled integration of the proposed attention mechanism, an initial comparative evaluation was conducted against state-of-the-art alternatives. Specifically, CBAM and SimAM were embedded at the same spatial location as RCCA to enable a fair and isolated comparison. This preliminary study confirmed the superior representational capacity of RCCA, thereby justifying its selection for subsequent integration.

Following this, a three-stage ablation study was designed to systematically quantify the impact of each architectural enhancement. Spanning eight controlled configurations, the experiments independently assessed the contributions of contextual attention and deformable convolutions across both the backbone and neck. The final experiment integrated the most effective modules into a unified DRC2-Net design, highlighting their complementary synergy in boosting multi-scale SAR ship detection performance.

Table 2 reports the results of

Experiment 1, which examines the effect of contextual attention mechanisms embedded within the backbone. Using the default YOLOX-Tiny (

BB-0) as the baseline, several enhanced variants were evaluated by inserting attention modules immediately after the SPP bottleneck in the Dark5 stage. These configurations include

BB-1 (CBAM),

BB-2 (SimAM),

BB-3 (CCA), and

BB-4 (RCCA).

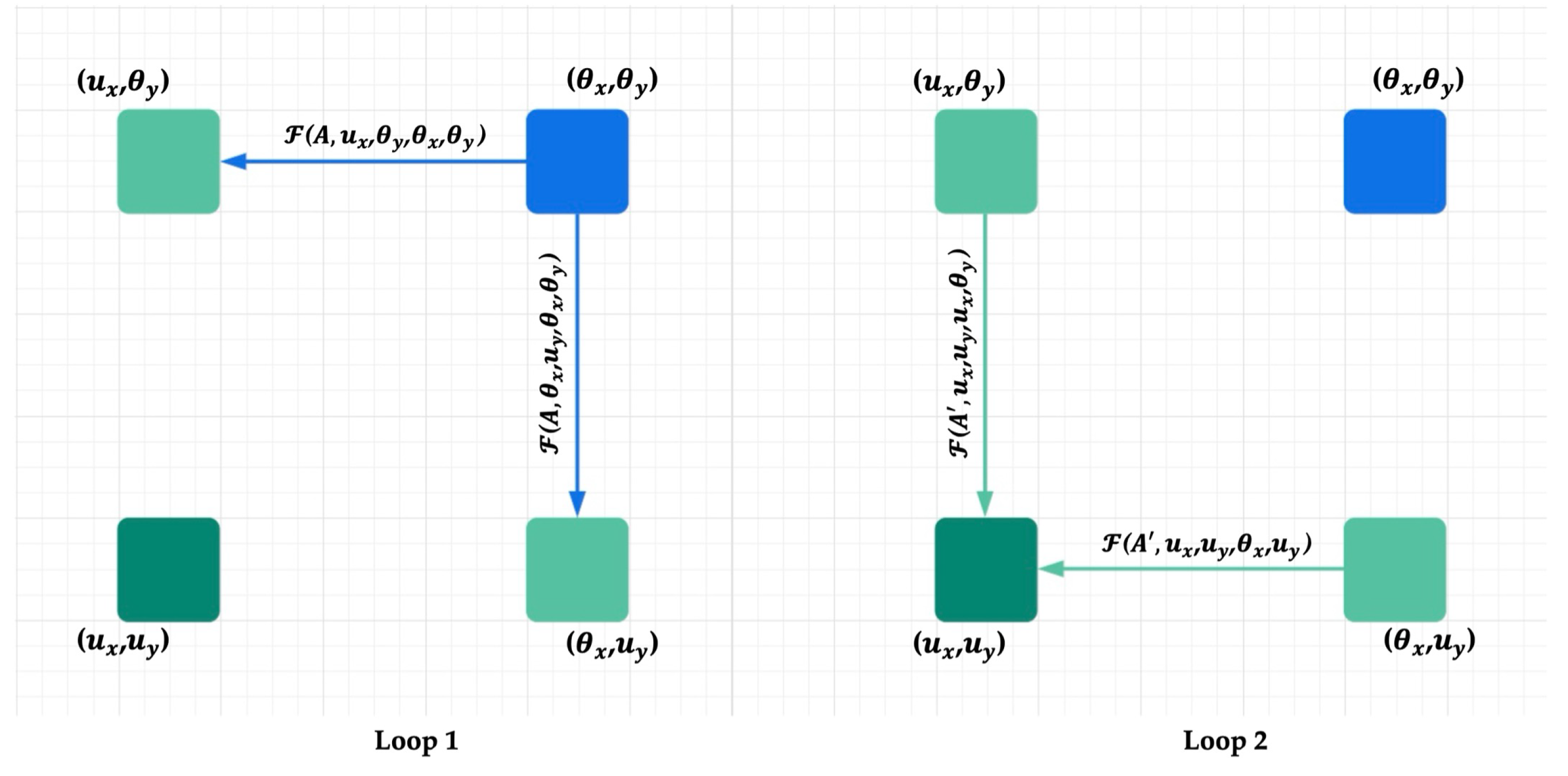

To systematically evaluate the effect of attention mechanisms within the YOLOX-Tiny backbone, five configurations were tested by inserting different modules after the SPP bottleneck in the Dark5 stage. The baseline (BB-0), without attention, achieved a solid reference performance with mAP@50 of 90.89%, AP of 61.32%, and F1-score of 94.57%. This configuration established the baseline semantic representation and localization capacity for SAR ship detection. Integrating CBAM (BB-1) produced the highest precision (97.30%) but reduced AP to 59.71% (% compared to baseline), indicating that while CBAM reinforces object confidence, it lacks sufficient adaptability in cluttered SAR scenes. SimAM (BB-2) reached 60.02% AP and the highest APm (89.63%), but only modestly improved recall (92.86%) and APl (+5.25%), suggesting its neuron-level importance estimation does not generalize well across scales. CCA (BB-3) enabled criss-cross feature interactions, yielding a balanced performance with AP of 61.21% and recall of 92.12%, alongside moderate improvements in APm, though it still underperformed for small and large targets. RCCA (BB-4), by contrast, achieved the best overall performance. Its iterative refinement across horizontal and vertical dimensions improved AP to 61.92% (+0.60%), recall to 93.04% (+0.55%), and APl to 84.21% (+5.26%), while maintaining strong precision (96.58%) and competitive mAP@50 (91.09%).

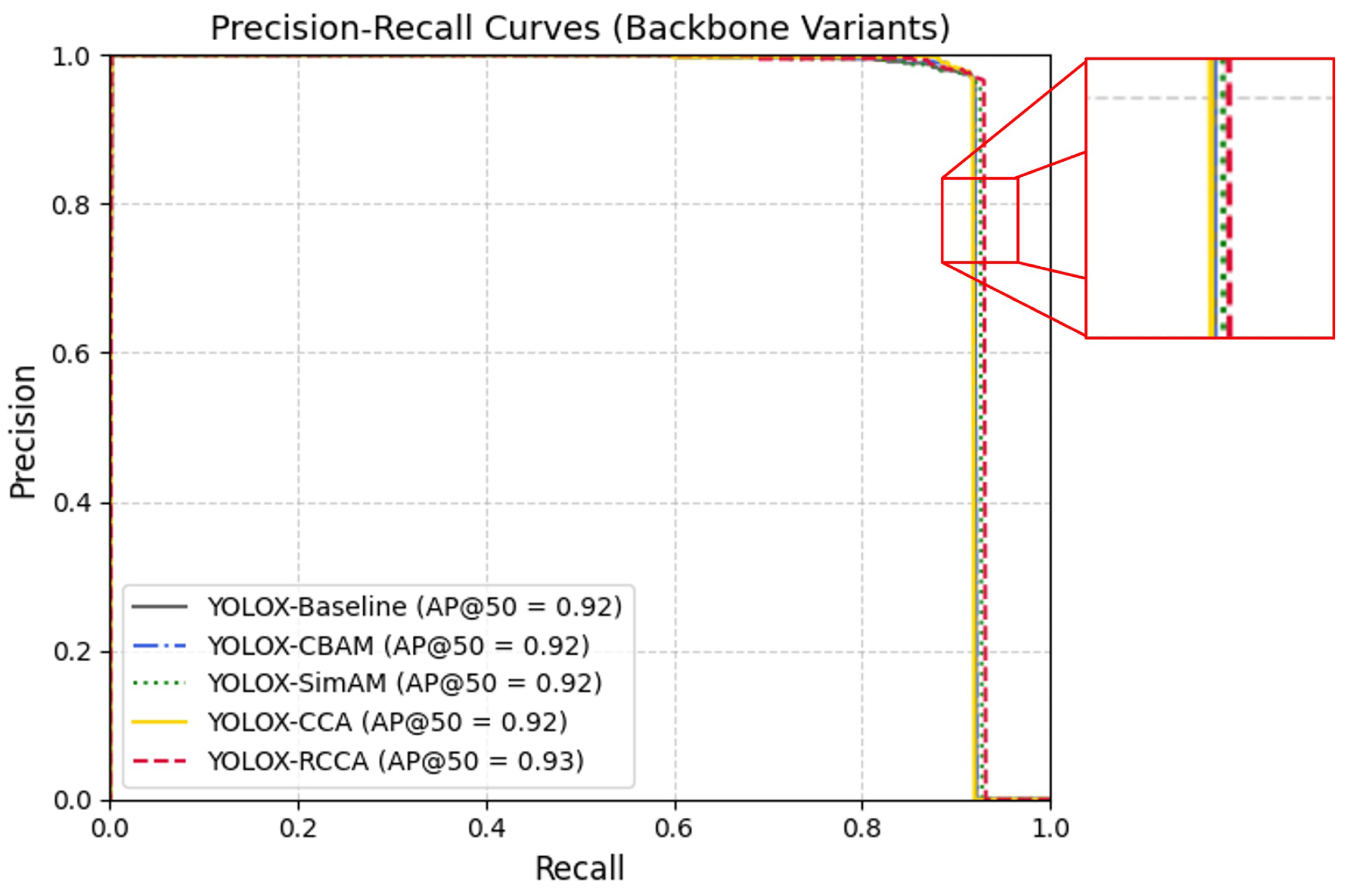

The results demonstrate that RCCA surpasses all tested alternatives, offering stronger contextual modeling and scale adaptability with minimal overhead. As shown in

Figure 9, the Precision–Recall curve confirms this advantage: the RCCA-enhanced backbone sustains higher precision across a broad recall range, yielding superior AP@50. This visual evidence reinforces the quantitative findings, validating RCCA’s role in strengthening spatial–semantic representation and supporting its integration into the final DRC

2-Net architecture.

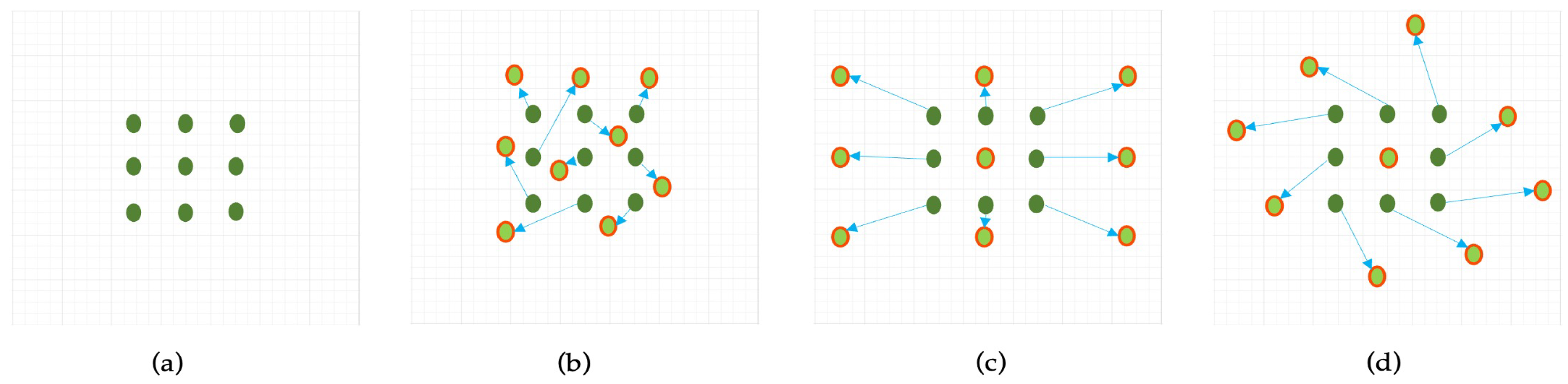

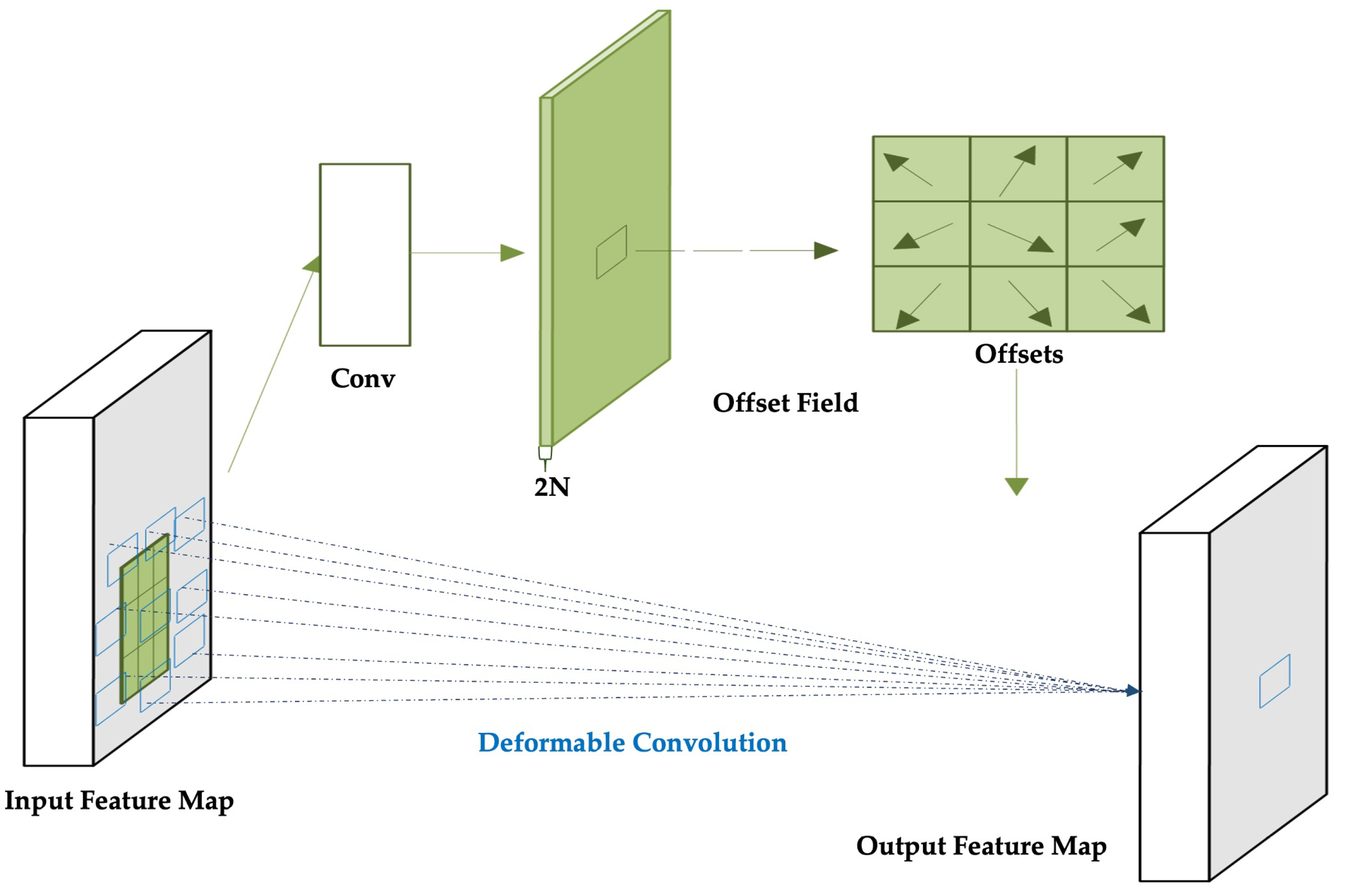

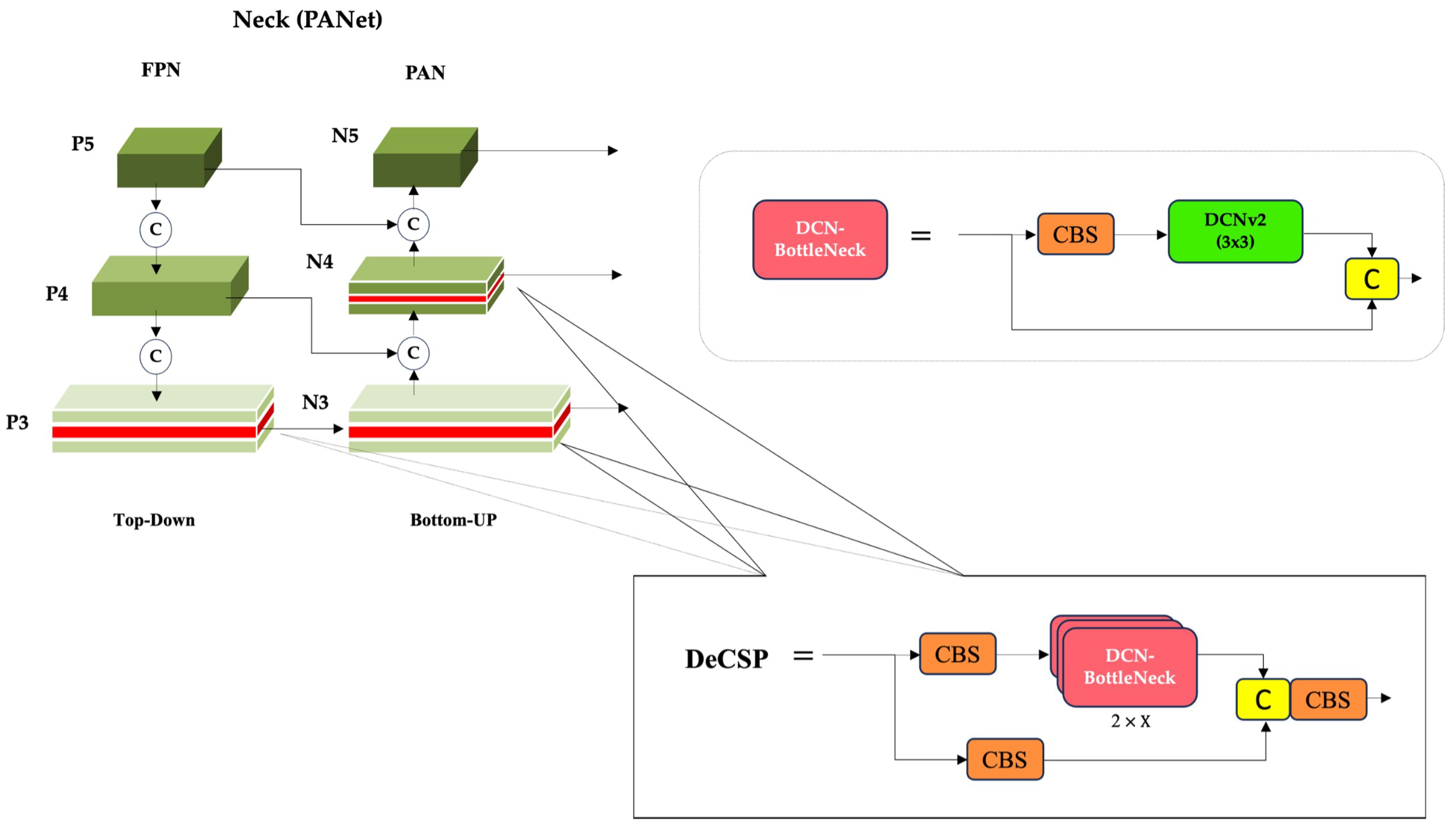

Table 3 presents the results of Experiment 2, which evaluates the impact of deformable convolutional enhancements within the neck while reusing the same backbone variants from Experiment 1. Three neck configurations were explored:

NK-0 denotes the original YOLOX neck;

NK-1 integrates two DeCSP blocks into the bottom-up path at C3_N3 and C3_N4; and

NK-2 extends this design by adding a third DeCSP block in the top-down path at C3_P3. This setup isolates the contribution of the neck, particularly the influence of DCNv2, on multi-scale feature fusion and spatial adaptability, while maintaining consistency in the backbone structure across all variants.

On the other hand, The baseline configuration (NK-0), which employs standard CSPLayers, establishes strong performance with the highest AP (61.32%) and APs (89.97%), confirming its suitability for small target detection. When two DeCSP blocks are introduced into the bottom-up path (NK-1), precision improves to 97.48% and APl rises to 84.21% (+5.26% over baseline), indicating that adaptive sampling strengthens localization for larger and irregular ship targets. However, the overall AP decreases slightly (60.53%), suggesting that the deformable design sacrifices some sensitivity to small-scale targets.

Extending the architecture with a third DeCSP block in the top-down path (NK-2) further boosts APm to 90.43% (+3.20%) and APl to 89.47% (+10.52%), demonstrating improved multi-scale refinement and geometric adaptability. Nevertheless, this configuration results in reduced mAP50 (-1.29%) and a noticeable decline in APs (-3.24%), confirming that excessive deformability can weaken fine-grained detection in cluttered SAR backgrounds. These findings highlight that while deformable convolutions benefit mid-to-large targets, they require balancing to maintain small-scale accuracy.

Table 4 presents the results of Experiment 3, which integrates the most effective components identified in the earlier studies—namely, the RCCA-augmented backbone (BB-4) and the 3-DeCSP neck configuration (NK-2)—into a unified architecture, referred to as DRC

2-Net. While the neck-only experiments indicated that deformable convolutions primarily benefit mid-to-large targets at the expense of small-scale accuracy, their combination with RCCA effectively balances this trade-off. In the final design, the three DeCSP modules work in harmony with RCCA, enhancing multi-scale representation without sacrificing the lightweight nature of the YOLOX-Tiny foundation.

Experiment 3 validates the complementary synergy between global contextual attention and deformable convolutional sampling. The integrated design enhances both semantic representation and spatial adaptability, yielding consistent improvements across scales. Specifically, DRC2-Net achieves gains of +0.98% in mAP@50, +0.61% in overall AP, and +0.49% in F1-score over the baseline YOLOX-Tiny. Notably, improvements are most pronounced for small-object detection (APs: +1.18%) and large-object detection (APl: +10.52%). In conclusion, DRC2-Net represents a focused architectural refinement of YOLOX-Tiny, where RCCA strengthens long-range contextual reasoning while DeCSP modules adaptively refine multi-scale spatial features. These enhancements deliver a lightweight yet powerful SAR ship detector that balances efficiency with robustness, making it suitable for real-time maritime surveillance in complex environments.

4.5. Comparative Evaluation with Lightweight and State-of-the-Art SAR Detectors on SSDD

To comprehensively assess the performance of the proposed DRC

2-Net, we benchmarked it against a range of representative object detectors. These include mainstream YOLO variants such as YOLOv5 [

42], YOLOv6 [

43], YOLOv3 [

44], YOLOv7-tiny [

45], and YOLOv8n [

46], as well as lightweight SAR-specific models including YOLO-Lite [

47] and YOLOSAR-Lite [

48].

As summarized in

Table 5, DRC

2-Net achieves the highest F1-score of

95.06%, outperforming all baseline detectors. It also attains the highest precision (96.77%) and a strong recall (93.41%), highlighting its ability to minimize false positives while maintaining sensitivity to true targets. These results demonstrate that the integration of contextual reasoning and geometric adaptability in DRC

2-Net leads to superior SAR ship detection performance across diverse conditions.

As summarized, the proposed DRC2-Net achieves superior performance across both general-purpose and SAR-specific lightweight detectors. It attains the highest F1-score of 95.06%, reflecting an optimal balance between precision (96.77%) and recall (93.41%). This is achieved with only 5.05M parameters and 9.59 GFLOPs, underscoring its efficiency. Compared to mainstream detectors such as YOLOv5 and YOLOv8n, which demonstrate strong precision above 95% but do not report F1-scores, DRC2-Net provides a more complete and favorable performance profile. While YOLOv7-tiny yields the highest recall (94.9%), its relatively lower precision (92.9%) and absence of F1-score reporting limit a balanced assessment.

In contrast, DRC2-Net consistently outperforms domain-specific lightweight models. YOLO-Lite achieves an F1-score of 93.39% and YOLOSAR-Lite 91.75%, yet both fall short of DRC2-Net’s accuracy while maintaining similar or larger parameter counts. With its compact size (5.05M parameters) and moderate computational cost (9.59 GFLOPs), DRC2-Net establishes a favorable balance between detection effectiveness and efficiency. These results make it particularly suitable for real-time SAR ship detection in resource-constrained environments, setting a new benchmark for lightweight detection frameworks. The strong gains further motivate broader generalization experiments on diverse and higher-resolution datasets such as iVision-MRSSD, discussed in the following section.

4.6. Quantitative Evaluation on the iVision-MRSSD Dataset

We further evaluated the proposed model on the recently introduced

iVision-MRSSD dataset, a high-resolution SAR benchmark released in 2023. In contrast to SSDD, iVision-MRSSD presents greater challenges due to its wide range of ship scales, dense coastal clutter, and highly diverse spatial scenarios, making it an appropriate benchmark for testing robustness in realistic maritime surveillance applications. A notable limitation of this domain is that many existing SAR ship detection models are not publicly available or lack detailed implementation specifications, hindering reproducibility. To ensure a fair and meaningful comparison, we therefore adopt uniform experimental settings wherever feasible and report the best available metrics as documented in the respective original publications. As shown in

Table 6, recent lightweight detectors such as YOLOv8n (58.1%), YOLOv11n (57.9%), and YOLOv5n (57.5%) achieve the highest overall Average Precision (AP) on the iVision-MRSSD dataset. These results demonstrate progress in global detection capability; however, they do not fully reflect robustness across different target scales.

A more detailed scale-wise evaluation highlights the advantage of the proposed DRC2-Net, which achieves 71.56% APs, 84.15% APm, and 78.43% APl. These values significantly surpass the competing baselines, particularly in the detection of small and medium-sized ships, which are often missed by other models due to resolution loss and heavy background clutter in SAR imagery. By comparison, YOLOv8n and YOLOv11n report strong overall AP, but their APs values (51.5% and 52.1%, respectively) reveal notable limitations in small object detection.

This performance gap emphasizes the importance of scale-aware design. The combination of RCCA for global contextual reasoning and DeCSP modules for adaptive receptive fields enables DRC2-Net to maintain consistent performance across scales. Consequently, the proposed framework provides a robust and efficient solution for complex SAR ship detection tasks, balancing accuracy and scale sensitivity in diverse maritime environments.

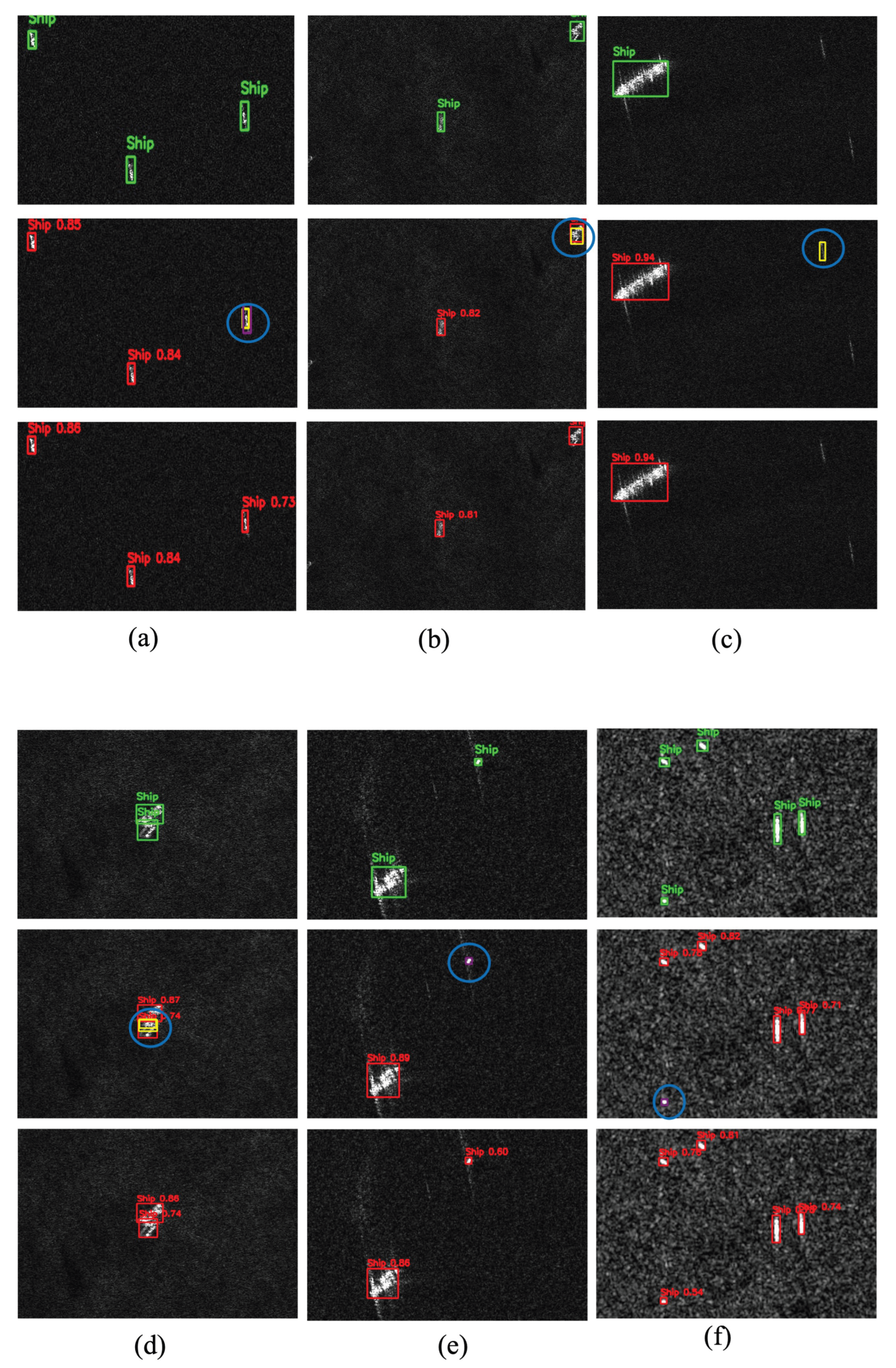

To qualitatively assess detection performance, representative scenes from the SSDD dataset are illustrated in

Figure 10. Columns (a–i) cover diverse maritime conditions, including open-sea scenarios, nearshore environments, and multi-scale ship distributions within cluttered backgrounds. These examples emphasize the inherent challenges of SAR-based ship detection and provide visual evidence of the improvements achieved by the proposed DRC

2-Net.

In all qualitative figures presented in this paper, each column corresponds to a different scene, with three rows displayed vertically: the top row shows ground-truth annotations, the middle row depicts predictions from the baseline YOLOX-Tiny, and the bottom row presents predictions from DRC2-Net. For consistency, the same color coding is applied throughout: green boxes denote ground truth, red boxes indicate correct detections, yellow boxes mark false positives, purple boxes highlight missed targets, and blue circles emphasize critical errors.

False alarms (yellow boxes) are most frequent in open-sea and offshore scenes (

Figure 10a, 10b, 10c, and 10d), where wakes and wave patterns often resemble ships and confuse conventional detectors. DRC

2-Net alleviates these errors through deformable convolutions, which adapt the receptive fields to better distinguish targets from clutter. Missed detections (purple boxes) appear mainly in

Figure 10e, 10f, and 10h, usually involving small or low-contrast ships. Notably, across all illustrated cases, DRC

2-Net missed only one target, demonstrating the advantage of RCCA in leveraging contextual cues to recover ambiguous or fragmented ships. Overall, these results confirm that DRC

2-Net achieves higher reliability by reducing false positives while improving sensitivity to challenging ship instances.

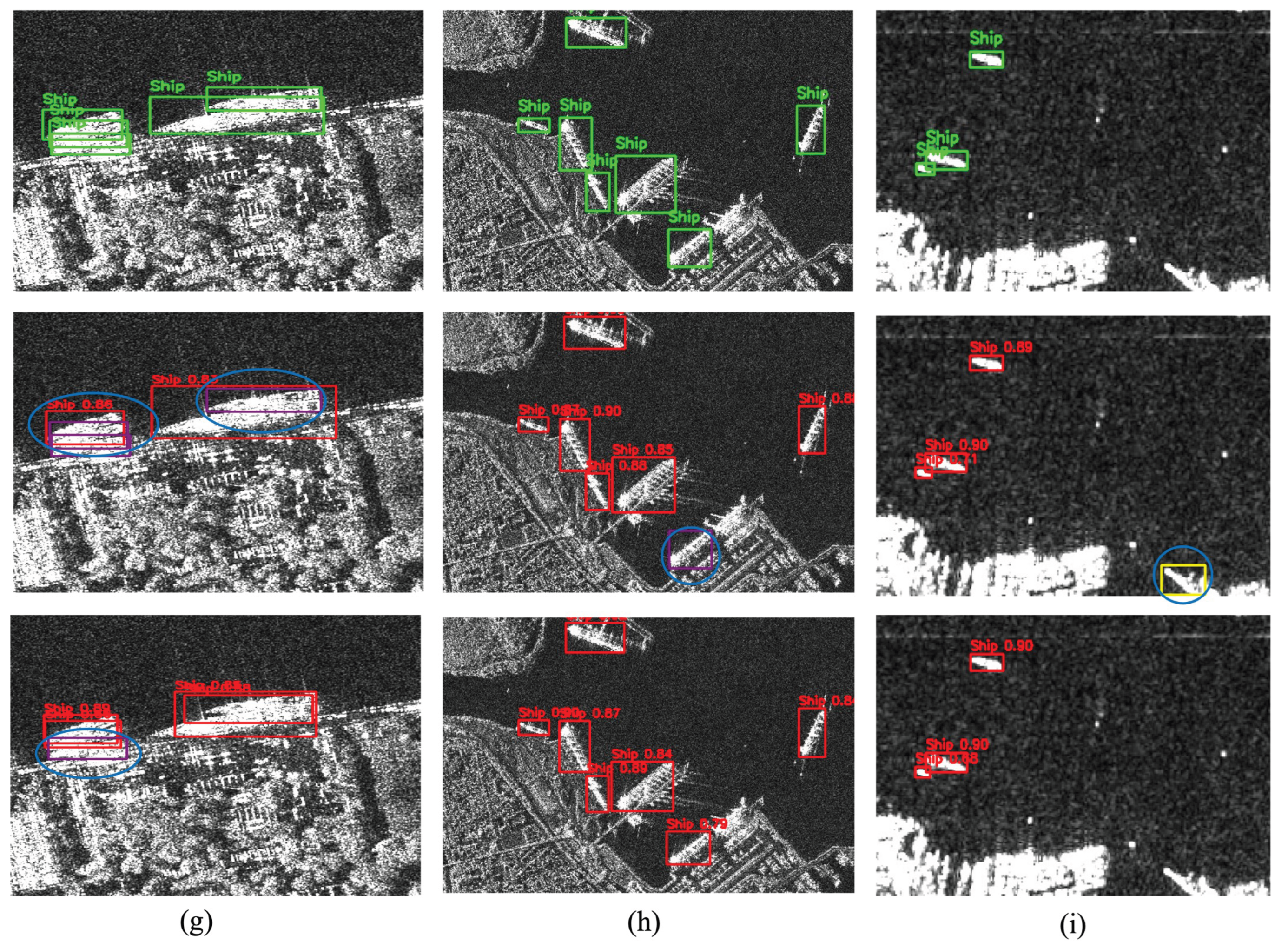

To further validate the generalization capability of the proposed DRC2-Net, instance-level visual comparisons were conducted across three representative sets of SAR scenes from the iVision-MRSSD dataset. These samples encompass data from six distinct satellite sensors and are grouped into three major scenarios, each highlighting specific detection challenges.

Figure 11 shows

Scenario A (a–e), covering shorelines, harbors, and congested maritime zones with dense vessel clusters and coastal infrastructure. These conditions often trigger false alarms and mislocalizations, particularly for small, low-resolution ships affected by scale variation and background interference. While the baseline YOLOX-Tiny frequently misses or misclassifies such targets, the proposed DRC

2-Net achieves more precise localization, especially near image edges, demonstrating greater robustness in challenging coastal environments.

Figure 12 presents

Scenario B (a–f), which depicts densely packed ships in far-offshore environments. These conditions are characterized by low signal-to-clutter ratios, heavy speckle noise, and ambiguous scattering patterns, all of which make target visibility and discrimination difficult. In such challenging scenes, missed detections frequently arise from faint radar returns and poorly defined object boundaries. Compared with the baseline, the proposed DRC

2-Net demonstrates stronger resilience to these issues, achieving more reliable detection under severe offshore clutter.

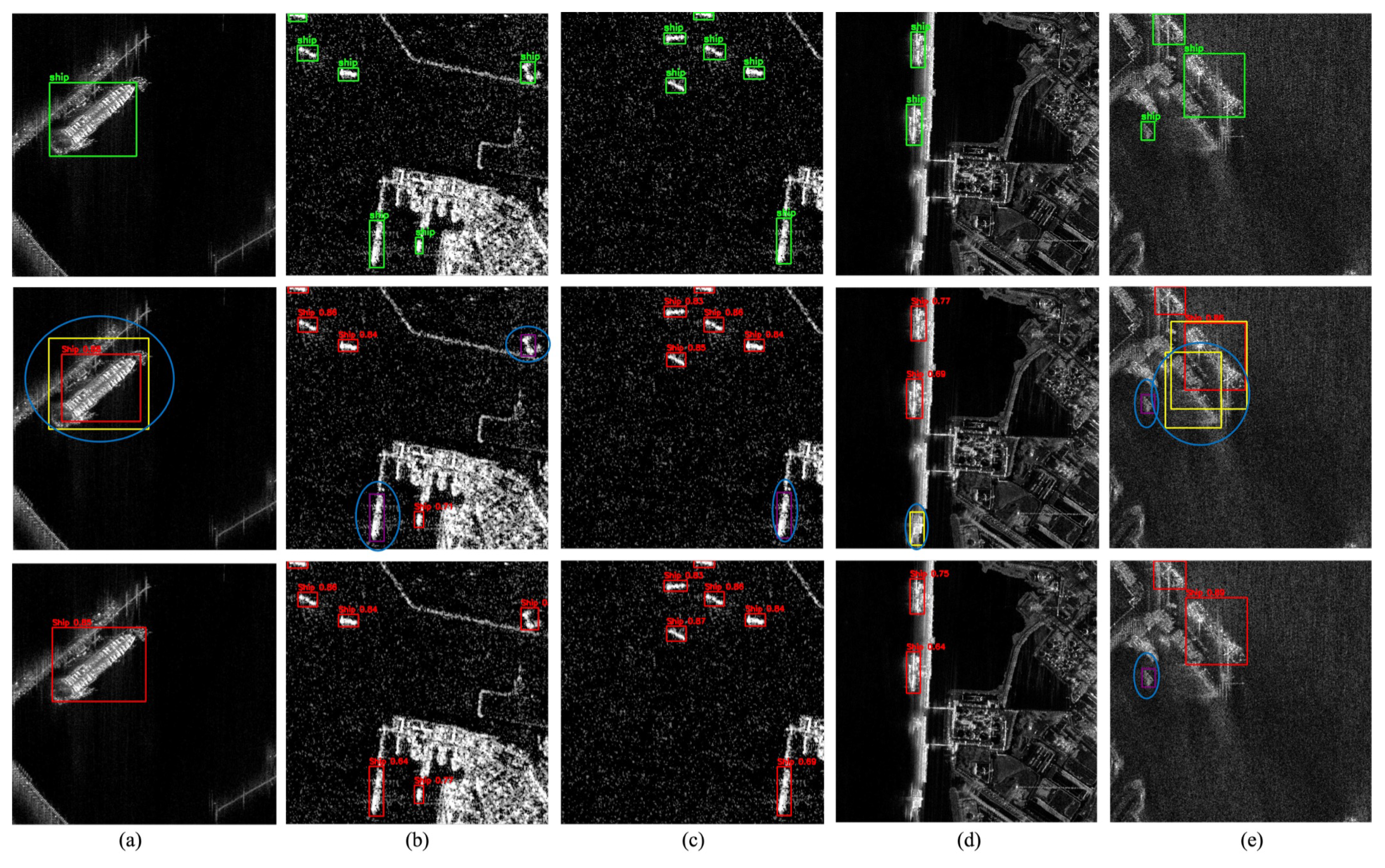

Figure 13 presents the final group of test scenes (

Scenario C), featuring severe speckle noise, clutter, and ambiguous scattering patterns typical of moderate-resolution SAR imagery and rough sea states. These challenging conditions often lead to false positives and missed detections in baseline models. By contrast, the proposed model demonstrates stronger robustness, accurately localizing vessels despite degraded image quality and complex backgrounds.

In contrast, the proposed DRC2-Net demonstrates enhanced robustness by combining deformable convolutions with contextual attention, effectively suppressing spurious responses and improving target discrimination. The qualitative results confirm DRC2-Net’s ability to localize small and multi-scale vessels even under adverse imaging conditions, highlighting its generalization capability across offshore, coastal, and noise-dominant scenarios in the iVision-MRSSD dataset.

A quantitative summary of detection performance in terms of correct detections, false alarms, and missed targets is provided in

Table 7. The results clearly demonstrate the superiority of the proposed model across all scenarios. In

Scenario A, DRC

2-Net correctly detects 94.4% of ships (17/18), compared to only 61.1% for YOLOX-Tiny. In

Scenario B, it achieves 95.7% accuracy (88/92) versus 83.7% for the baseline, reducing missed detections from 13 to 2. In the most challenging

Scenario C, DRC

2-Net identifies 91.7% of ships (22/24), while YOLOX-Tiny captures only 58.3%. These improvements highlight the model’s robustness, particularly in cluttered and noise-dominant SAR environments, achieving up to a

+33.4% gain in detection accuracy over the baseline.