1. Introduction

West Nile (WNV) and Usutu (USUV) viruses are two emerging arboviruses belonging to the

Orthoflavivirus genus. They are mainly transmitted through the bites of infected

Culex spp. mosquitoes [

1]. Other modes of transmission have also been described in the literature, but they are less common [

2,

3,

4]. These viruses are maintained in an enzootic cycle involving passeriform (mainly common blackbird

Turdus merula) and strigiform (great grey owls -

Strix nebulosa) birds as reservoirs on one hand and ornithophilic mosquitoes, particularly

Culex pipiens on the other hand. These mosquitoes are endemic to France, and their activity period extends from June to late November, meaning that most WNV or USUV cases occur during the summer or fall seasons. These viruses can also be transmitted to dead-end hosts (which certainly develop a low viremia, insufficient to re-infect mosquitoes [

5]) have been identified [

6] : horses [

7,

8,

9,

10], dogs [

7,

8], rodents [

11], squirrels [

12], wild boar [

13,

14] and roe deer [

14]. The virus has also been detected in bats, whose epidemiological role is as yet undetermined [

15]. In humans, a wide range of symptoms are described in the literature, from flu-like illness to severe neurological disorders as encephalitis or meningitis [

16]. For several years, WNV has been responsible for multiple outbreaks, the most well-known being the 1999 outbreak in New York. Following this outbreak, a study was conducted to determine whether WNV could survive through the winter by being maintained in overwintering female mosquitoes. In New York City, researchers tested and found multiple pools of overwintering Culex mosquitoes positive for WNV RNA [

17]. Another study conducted in California showed that several factors contribute to WNV persistence during the cold season [

18]. It is also known that WNV can be vertically transmitted in

Aedes mosquitoes, allowing the virus to be passed to the offspring of overwintering mosquitoes in laboratory experiments [

19]. This transmission occurs during oviposition, when WNV enters in mosquito eggs [

20].

In France, avian mortality data from 2018 suggested the endemization of USUV, particularly in certain regions such as Centre-Val de Loire, Ile-de-France and Pays de la Loire [

21]. Mosquito capture missions were carried out around birds outbreak areas that emerged during the project to assess their transmission potential. SAGIR network which is dedicated to epidemiological surveillance, through the collection of dead or moribund birds and mammals (opportunistic sampling method). This participatory surveillance program aims at detecting as early as possible abnormal mortality or morbidity signals. A total of 33 outbreaks across metropolitan France (representing 47 bird carcasses) were analyzed and recorded in the database from 2020 to 2022. After the 2018 epizootic in blackbird populations with high mortality [

22], there was little mortality afterwards until 2022 in mainland France. Since 2022, it appears that the mortality had increased [

23].

As part of the surveillance of WNV and USUV, several mosquito collection campaigns were conducted between 2021 and 2024 in northeastern French departments where infected birds had been identified. These collections aimed to examine mosquito species potentially involved in the overwintering persistence of these viruses.

The aim of our study was therefore to estimate the transmission of two arboviruses, West Nile and Usutu viruses, by overwintering mosquitoes in northern France and to determine whether overwintering females play a role in maintaining these viruses during the cold season within the natural virus cycle.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mosquitoes Field Collections

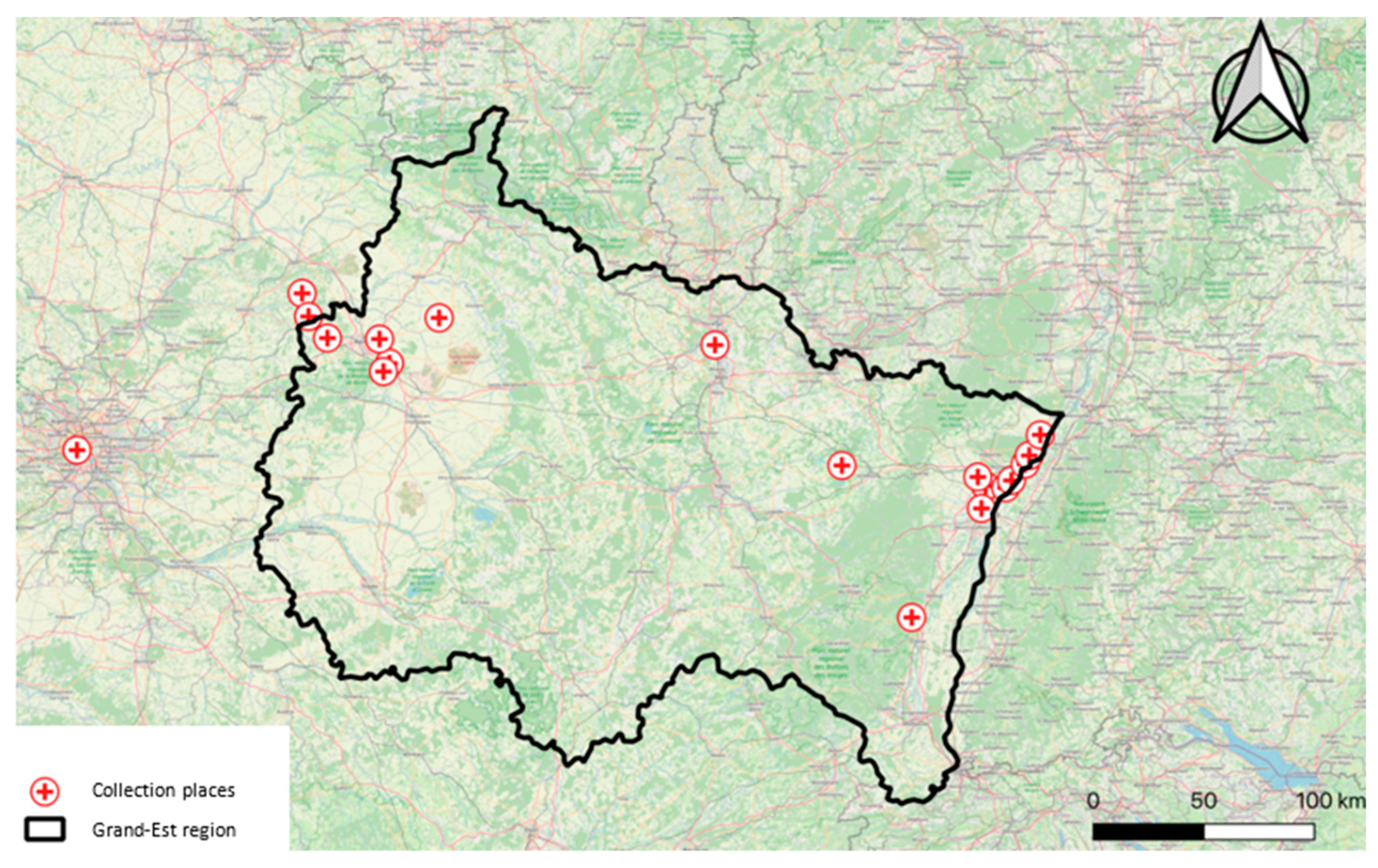

Between October 2021 and February 2024, five mosquito field surveys were conducted in five departments of northeastern France: Moselle, Aisne, Marne, Haut-Rhin, and Bas-Rhin where dead birds infected with USUV were found [

24] (

Figure 1). These collections allowed them to capture 10,617 overwintering female mosquitoes. Mosquitoes were collected using an insect pooter, allowing to capture directly the mosquitoes in locations such as caves, bunkers, and hunting grounds, which are known to serve as overwintering habitats [

25] (

Figure 2).

Various mosquito species were collected from these different locations: Culex pipiens, Culiseta annulata, Anopheles maculipennis, Anopheles plumbeus, Culex territans, Culex hortensis, and Aedes vexans.

When overwintering female mosquitoes are captured, specimens of the same species are grouped into pools of up to ten individuals. The number of mosquitoes in each tube ranged from 1 to 10.

2.2. Total Nucleic Acid Purification

Female mosquito pools were homogenized in 1000µL of Minimum Elementary Medium (MEM) supplemented with 3% of Amphotericin B, 1% of Kanamycin, 1% of Penicillin-Streptomycin as previously described [

26].

A 100 µL aliquot of the homogenized mosquito sample was mixed with 100 µL of PBS buffer and 100 µL of lysis buffer.

Viral RNA was extracted using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The final elution volume was 90 µL. All collected female specimens were tested for WNV and USUV RNA detection.

2.3. WNV and USUV RNA Detection

A combination of primers was used with two WNV-specific (WNV duo) and two USUV-specific (USUV duo) real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assays to screen female mosquito pools. The WNV duo consists of two systems targeting different genome regions: one targets the Capsid [

27] and the other targets the non-coding region (3'NC) [

28]. The USUV duo system consists of two assays targeting the non-structural 5 protein (NS5) [

29,

30] see

Table 1 and

Table 2. The MS2 (internal control to ensure effective RNA extraction) qRT-PCR assay was tested on all pools.

PCR amplification was conducted using the SuperScript III Platinum One-Step qRT-PCR kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with a reaction mix of 25 µL, including 5 µL of RNA template. The reaction was carried out on an a CFX96 thermal cycler, software version 3.1 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA), under the following conditions: reverse transcription at 50 °C for 15 minutes, initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 minutes, followed by 45 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds and 58 °C for 45 minutes.

2.4. Pan-Flavivirus RNA Detection

All the mosquitoes were tested by qRT-PCR with a pan-flavivirus assay using specific system targeting the Non-structural protein 5 (NS5) of the flaviviruses (

Table 3) [

31]. A one-step qRT-PCR assay using SYBR Green and melting curve analysis was performed by using 1× GoTaq qPCR Master Mix (Promega) with a reaction mix of 20µL, including 4µL of RNA template. The reaction was carried out on a thermocycleur QuantStudio™ 12K Flex Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific), under the following conditions: reverse transcription at 50 °C for 15 minutes, initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 minutes, followed by the PCR stages : 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 seconds, 50°C for 30 seconds and 75°C for 1 minute. To finish the melt curve stage includes two cycles : 60°C for 1 minute followed by 95°C for 15 seconds.

3. Results

3.1. Mosquito Collection

A total of 10,617 overwintering female mosquitoes were collected in different places in northeastern France during the cold season between October 2021 to February 2024. The morphological identification of mosquitoes revealed four genera:

Culex spp. (9360 specimens, 963 pools),

Culiseta spp. (825 specimens, 101 pools),

Anopheles spp. (421 specimens, 52 pools),

Aedes spp. (11 specimens, 5 pools) (

Figure S1).

3.2. Viral Screening

All 1,121 mosquito pools tested by qRT-PCR were negative for West Nile virus, Usutu virus, and pan-Flavivirus (

Table 4 and

Table S1).

4. Discussion

This study screened 10,617 overwintering female mosquitoes across five departments in northeastern France using highly sensitive RT-PCR assays targeting independently WNV and USUV, and a broad pan-Flavivirus system. All pools tested negative, indicating no evidence of viral RNA persistence in these mosquitoes during the cold season.

Several factors may explain the absence of WNV and USUV RNA detection in overwintering female mosquitoes. First, the low total number of overwintering mosquitoes collected could be a factor. Additionally, the mosquitoes collected may not be competent for the transmission of these viruses. But a study conducted by French researchers assessed the vector competence for Culex pipiens species present in northeastern France. The results showed that they are capable of transmitting WNV and USUV [

5].

Overwintering mosquitoes enter a state of diapause, characterized by reduced metabolic activity and feeding cessation. While this state could theoretically allow viral persistence, our results suggest that WNV and USUV may not survive the physiological stress of diapause in French mosquito populations. Laboratory studies have shown that vertical transmission - critical for arbovirus overwintering - varies significantly by mosquito species and viral strain.

Our results contrast with findings in other studies. In New York City, overwintering

Culex pipiens were tested positive for WNV RNA during the winter of 2000, suggesting localized viral persistence in hibernating mosquitoes [

17].

In South Moravia (Czech Republic), the overwintering was demonstrated by the detection of WNV lineage 2 in three out of 573 total pools (total mosquito population: 27,872) of

Culex pipiens collected in 2017, marking the first evidence of overwintering WNV in Central Europe [

32].

In the Netherlands, two studies were conducted to investigate the role of overwintering mosquitoes. In the first study, none of the 4,200 mosquitoes collected during the winters of 2020 and 2021 tested positive for WNV or USUV by RT-PCR [

33]. In the other study, one pool out of 504 total pools (total mosquito population: 4,857) tested positive for an Africa 3 strain of USUV [

34].

In Germany, a study provided the first evidence of West Nile virus overwintering in mosquitoes. One pool of

Culex pipiens out of 722 total pools (total mosquito population: 6,101), collected in early March 2021 tested positive for WNV RNA [

35].

There are many reasons that could explain the differences within each study and between these studies such as sampling locations, year of collection, mosquito species composition of captures, different overwintering capabilities of WNV and USUV. Also in these studies, the very low rates of positivity indicate that WNV and/or USUV are rare in dormant Culex populations. While overwintering mosquitoes likely contribute to viral persistence, their role appears limited given low detection rates. However, even sporadic cases could seed outbreaks when conditions favor vector activity.

The discrepancy between our results and these studies may reflect differences in regional viral prevalence, mosquito population dynamics, or overwintering behaviors. For instance, the New York and Czech studies were conducted in regions with well-established WNV enzootic cycles and higher annual incidence rates. In contrast, northeastern France has experienced sporadic WNV and USUV activity. Avian mortality cases linked to Usutu are sporadic, but the infection is enzootic. Clinical expression, and thus mortality, is not only related to the intensity of viral circulation, but also to the immune status of the population and probably to the circulating strains [

21]. Additionally, the mosquito species composition in France—dominated by

Culex pipiens (88% of collected specimens)—differs slightly from other regions where

Culex subspecies with distinct overwintering behaviors (e.g.,

Culex pipiens pipiens vs.

Culex pipiens molestus) may influence viral survival.

While

Culex pipiens in France has demonstrated laboratory competence for WNV and USUV transmission [

22], field conditions may reduce this capacity. Viral replication in mosquitoes is temperature-dependent, and colder winters in northeastern France (compared to Mediterranean climates) may reduce viral replication below detectable thresholds. Furthermore, the absence of blood-fed females in our collections (all specimens were unfed) suggests that mosquitoes had not recently acquired the virus from avian reservoirs prior to hibernation. This contrasts with regions where late-season blood-feeding bridges viral transmission into the overwintering period. Laboratory experiments exposing

Culex pipiens to WNV/USUV under diapause-like conditions would clarify whether physiological stressors limit viral survival.

The absence of viral RNA in mosquitoes raises questions about how WNV and USUV persist in France. One plausible explanation is reintroduction via migratory birds, which serve as primary reservoirs, but there is probably a local persistence of viruses. The virus could overwinter in the bird populations, including blackbirds. To verify this, it would be necessary to have access to hunted birds (since hunting takes place during autumn and winter). Controlling the sampling process would allow for prevalence estimation, and using dead birds would make it possible to test different organs by PCR. Similarly, WNV outbreaks in Europe often correlate with avian migration patterns rather than local overwintering. Additionally, non-mosquito pathways - such as persistent infection in reptiles or overwintering in ticks - remain underexplored but could contribute to viral maintenance.

While this study provides robust evidence against mosquito-mediated overwintering of WNV/USUV in northeastern France, several limitations warrant consideration. The collection focused on artificial overwintering sites (e.g., bunkers, caves), potentially overlooking natural habitats where mosquitoes might exhibit different behaviors.

The absence of viral persistence in overwintering mosquitoes suggests that seasonal WNV/USUV transmission in northeastern France is likely driven by reintroduction via migratory birds or localized enzootic cycles during warmer months. This has important implications for public health strategies: (i) resources should focus on monitoring avian populations and active mosquito vectors during peak transmission seasons (June–November) rather than overwintering sites; (ii) integrating migratory bird tracking with mosquito surveillance could improve outbreak prediction; (iii) vector control targeting Culex pipiens breeding sites (e.g., stagnant water) in late spring may disrupt enzootic transmission before human cases emerge.

The absence of WNV and USUV RNA in overwintering female mosquitoes collected across northeastern France between 2021 and 2024 challenges the hypothesis that these vectors play a role in maintaining arboviral transmission during the cold season in this region. This study provides compelling evidence that overwintering female mosquitoes in northeastern France do not serve as reservoirs for WNV or USUV during the cold season. While this reduces concerns about wintertime transmission, it reinforces the need for vigilant summer surveillance and interdisciplinary approaches to arbovirus management. Our results contrast with studies from other temperate regions, such as North America and Central Europe, where overwintering mosquitoes have been implicated in viral persistence. They underscore the complexity of arbovirus ecology and highlight the need to consider regional variations in vector biology, environmental conditions, and alternative viral maintenance mechanisms when designing surveillance and control strategies. Future research should explore the ecological drivers of viral persistence in temperate regions, particularly as climate change alters mosquito behavior and avian migration patterns.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Repartition of mosquito species by collection places ; Table S1: Detailed table of collection dates and locations, collected species, and results.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D, A.B.F. and R.C.; methodology, P.J., J-p.M., H.F., B.M., J.D. and R.C.; validation, R.C. and B.M.; investigation, P.J., J-p.M., H.F., B.M. and J.D. ; resources, R.C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.J., R.C., A.D.; writing—review and editing, M.V., A.D., R.C. ; supervision, R.C. , A.B.F. ; project administration, A.B.F.; funding acquisition, J.D. and A.B.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the MOSQUITWO project (Agence Nationale de Sécurité Sanitaire de l’Alimentation, de l’Environnement et du Travail), grant number 2020-01-129. The material for molecular detection of viruses was provided by the European virus archive-Marseille (EVAM) under the label technological platforms of Aix-Marseille University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We thank Laurence Thirion, Pierre Combe, Gregory Molle and Cecile Baronti for providing the EVAM reagents.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WNV |

West Nile Virus |

| USUV |

Usutu virus |

| qRT-PCR |

real time Reverse transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PCR |

Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| NS5 |

Non-Structural protein 5 |

| Spp. |

Species pluralis |

| RNA |

Ribonucleic Acid |

| SAGIR |

French national network for the epidemiological surveillance of wildlife diseases |

| MEM |

Minimum Essential Medium |

| 3’NC |

3’ Non-Coding |

| EQA |

External Quality Assessment |

| COFRAC |

French national body for laboratory and certification accreditation |

| EVAM |

European Virus Archive – Marseille |

| Lyo P&P |

Primers and Probes Lyophilized |

| PBS |

Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

References

- Kuchinsky, S.C.; Duggal, N.K. Chapter Two - Usutu Virus, an Emerging Arbovirus with One Health Importance. In Advances in Virus Research; Macdiarmid, R., Lee, B., Beer, M., Eds.; Academic Press, 2024; Vol. 120, pp. 39–75. [Google Scholar]

- Pealer, L.N.; Marfin, A.A.; Petersen, L.R.; Lanciotti, R.S.; Page, P.L.; Stramer, S.L.; Stobierski, M.G.; Signs, K.; Newman, B.; Kapoor, H.; et al. Transmission of West Nile Virus through Blood Transfusion in the United States in 2002. N Engl J Med 2003, 349, 1236–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwamoto, M.; Jernigan, D.B.; Guasch, A.; Trepka, M.J.; Blackmore, C.G.; Hellinger, W.C.; Pham, S.M.; Zaki, S.; Lanciotti, R.S.; Lance-Parker, S.E.; et al. Transmission of West Nile Virus from an Organ Donor to Four Transplant Recipients. N Engl J Med 2003, 348, 2196–2203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, E.B.; O’Leary, D.R. West Nile Virus Infection: A Pediatric Perspective. Pediatrics 2004, 113, 1375–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinet, J.-P.; Bohers, C.; Vazeille, M.; Ferté, H.; Mousson, L.; Mathieu, B.; Depaquit, J.; Failloux, A.-B. Assessing Vector Competence of Mosquitoes from Northeastern France to West Nile Virus and Usutu Virus. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2023, 17, e0011144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilibic-Cavlek, T.; Petrovic, T.; Savic, V.; Barbic, L.; Tabain, I.; Stevanovic, V.; Klobucar, A.; Mrzljak, A.; Ilic, M.; Bogdanic, M.; et al. Epidemiology of Usutu Virus: The European Scenario. Pathogens 2020, 9, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seroprevalence of West Nile and Usutu Viruses in Military Working Horses and Dogs, Morocco, 2012: Dog as an Alternative WNV Sentinel Species? | Epidemiology & Infection | Cambridge Core Available online:. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/epidemiology-and-infection/article/seroprevalence-of-west-nile-and-usutu-viruses-in-military-working-horses-and-dogs-morocco-2012-dog-as-an-alternative-wnv-sentinel-species/F1E419419D8A8C04D458474207430C8C (accessed on 14 May 2025).

- Maquart, M.; Dahmani, M.; Marié, J.-L.; Gravier, P.; Leparc-Goffart, I.; Davoust, B. First Serological Evidence of West Nile Virus in Horses and Dogs from Corsica Island, France. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 2017, 17, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csank, T.; Drzewnioková, P.; Korytár, Ľ.; Major, P.; Gyuranecz, M.; Pistl, J.; Bakonyi, T. A Serosurvey of Flavivirus Infection in Horses and Birds in Slovakia. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 2018, 18, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bażanów, B.; Jansen van Vuren, P.; Szymański, P.; Stygar, D.; Frącka, A.; Twardoń, J.; Kozdrowski, R.; Pawęska, J.T. A Survey on West Nile and Usutu Viruses in Horses and Birds in Poland. Viruses 2018, 10, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diagne, M.M.; Ndione, M.H.D.; Di Paola, N.; Fall, G.; Bedekelabou, A.P.; Sembène, P.M.; Faye, O.; Zanotto, P.M. de A.; Sall, A.A. Usutu Virus Isolated from Rodents in Senegal. Viruses 2019, 11, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, C.; Lecollinet, S.; Caballero, J.; Isla, J.; Luzzago, C.; Ferrari, N.; García-Bocanegra, I. Are Tree Squirrels Involved in the Circulation of Flaviviruses in Italy? Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 2018, 65, 1372–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escribano-Romero, E.; Lupulović, D.; Merino-Ramos, T.; Blázquez, A.-B.; Lazić, G.; Lazić, S.; Saiz, J.-C.; Petrović, T. West Nile Virus Serosurveillance in Pigs, Wild Boars, and Roe Deer in Serbia. Veterinary Microbiology 2015, 176, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bournez, L.; Umhang, G.; Faure, E.; Boucher, J.-M.; Boué, F.; Jourdain, E.; Sarasa, M.; Llorente, F.; Jiménez-Clavero, M.A.; Moutailler, S.; et al. Exposure of Wild Ungulates to the Usutu and Tick-Borne Encephalitis Viruses in France in 2009–2014: Evidence of Undetected Flavivirus Circulation a Decade Ago. Viruses 2020, 12, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cadar, D.; Becker, N.; Campos, R. de M.; Börstler, J.; Jöst, H.; Schmidt-Chanasit, J. Usutu Virus in Bats, Germany, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis 2014, 20, 1771–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonin, Y. Circulation of West Nile Virus and Usutu Virus in Europe: Overview and Challenges. Viruses 2024, 16, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasci, R.S.; Savage, H.M.; White, D.J.; Miller, J.R.; Cropp, B.C.; Godsey, M.S.; Kerst, A.J.; Bennett, P.; Gottfried, K.; Lanciotti, R.S. West Nile Virus in Overwintering Culex Mosquitoes, New York City, 2000. Emerg Infect Dis 2001, 7, 742–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisen, W.K.; Wheeler, S.S. Overwintering of West Nile Virus in the United States. J Med Entomol 2019, 56, 1498–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baqar, S.; Hayes, C.G.; Murphy, J.R.; Watts, D.M. Vertical Transmission of West Nile Virus by Culex and Aedes Species Mosquitoes. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1993, 48, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, L. Further Observations on the Mechanism of Vertical Transmission of Flaviviruses by Aedes Mosquitoes. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1988, 39, 123–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouchez-Zacria, M.; Calenge, C.; Villers, A.; Lecollinet, S.; Gonzalez, G.; Quintard, B.; Leclerc, A.; Baurier, F.; Paty, M.-C.; Faure, É.; et al. Relevance of the synergy of surveillance and populational networks in understanding the Usutu virus outbreak within common blackbirds (Turdus merula) in Metropolitan France, 2018. Peer Community Journal 2025, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decors, A.; Beck, C. 2018, En France : Record de Circulation Du Virus Usutu. Faune sauvage 2019, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Schopf, F.; Sadeghi, B.; Bergmann, F.; Fischer, D.; Rahner, R.; Müller, K.; Günther, A.; Globig, A.; Keller, M.; Schwehn, R.; et al. Circulation of West Nile Virus and Usutu Virus in Birds in Germany, 2021 and 2022. Infect Dis (Lond) 2025, 57, 256–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecollinet, S.; Blanchard, Y.; Manson, C.; Lowenski, S.; Laloy, E.; Quenault, H.; Touzain, F.; Lucas, P.; Eraud, C.; Bahuon, C.; et al. Dual Emergence of Usutu Virus in Common Blackbirds, Eastern France, 2015. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 2225–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romiti, F.; Casini, R.; Del Lesto, I.; Magliano, A.; Ermenegildi, A.; Droghei, S.; Tofani, S.; Scicluna, M.T.; Pichler, V.; Augello, A.; et al. Characterization of Overwintering Sites (Hibernacula) of the West Nile Vector Culex Pipiens in Central Italy. Parasit Vectors 2025, 18, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauffman, E.B.; Franke, M.A.; Kramer, L.D. Detection Protocols for West Nile Virus in Mosquitoes, Birds, and Nonhuman Mammals. In West Nile Virus; Colpitts, T.M., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2016; Vol. 1435, pp. 175–206. ISBN 978-1-4939-3668-7. [Google Scholar]

- Linke, S.; Ellerbrok, H.; Niedrig, M.; Nitsche, A.; Pauli, G. Detection of West Nile Virus Lineages 1 and 2 by Real-Time PCR. Journal of Virological Methods 2007, 146, 355–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Anne Hapip, C.; Liu, B.; Fang, C.T. Highly Sensitive TaqMan RT-PCR Assay for Detection and Quantification of Both Lineages of West Nile Virus RNA. Journal of Clinical Virology 2006, 36, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weissenböck, H.; Bakonyi, T.; Rossi, G.; Mani, P.; Nowotny, N. Usutu Virus, Italy, 1996. Emerg Infect Dis 2013, 19, 274–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolay, B.; Weidmann, M.; Dupressoir, A.; Faye, O.; Boye, C.S.; Diallo, M.; Sall, A.A. Development of a Usutu Virus Specific Real-Time Reverse Transcription PCR Assay Based on Sequenced Strains from Africa and Europe. Journal of Virological Methods 2014, 197, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scaramozzino, N.; Crance, J.-M.; Jouan, A.; DeBriel, D.A.; Stoll, F.; Garin, D. Comparison of Flavivirus Universal Primer Pairs and Development of a Rapid, Highly Sensitive Heminested Reverse Transcription-PCR Assay for Detection of Flaviviruses Targeted to a Conserved Region of the NS5 Gene Sequences. J Clin Microbiol 2001, 39, 1922–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudolf, I.; Betášová, L.; Blažejová, H.; Venclíková, K.; Straková, P.; Šebesta, O.; Mendel, J.; Bakonyi, T.; Schaffner, F.; Nowotny, N.; et al. West Nile Virus in Overwintering Mosquitoes, Central Europe. Parasit Vectors 2017, 10, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blom, R.; Schrama, M.J.J.; Spitzen, J.; Weller, B.F.M.; van der Linden, A.; Sikkema, R.S.; Koopmans, M.P.G.; Koenraadt, C.J.M. Arbovirus Persistence in North-Western Europe: Are Mosquitoes the Only Overwintering Pathway? One Health 2022, 16, 100467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koenraadt, C.J.M.; Münger, E.; Schrama, M.J.J.; Spitzen, J.; Altundag, S.; Sikkema, R.S.; Munnink, B.B.O.; Koopmans, M.P.G.; Blom, R. Overwintering of Usutu Virus in Mosquitoes, The Netherlands. Parasit Vectors 2024, 17, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kampen, H.; Tews, B.A.; Werner, D. First Evidence of West Nile Virus Overwintering in Mosquitoes in Germany. Viruses 2021, 13, 2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).