Submitted:

20 February 2025

Posted:

21 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

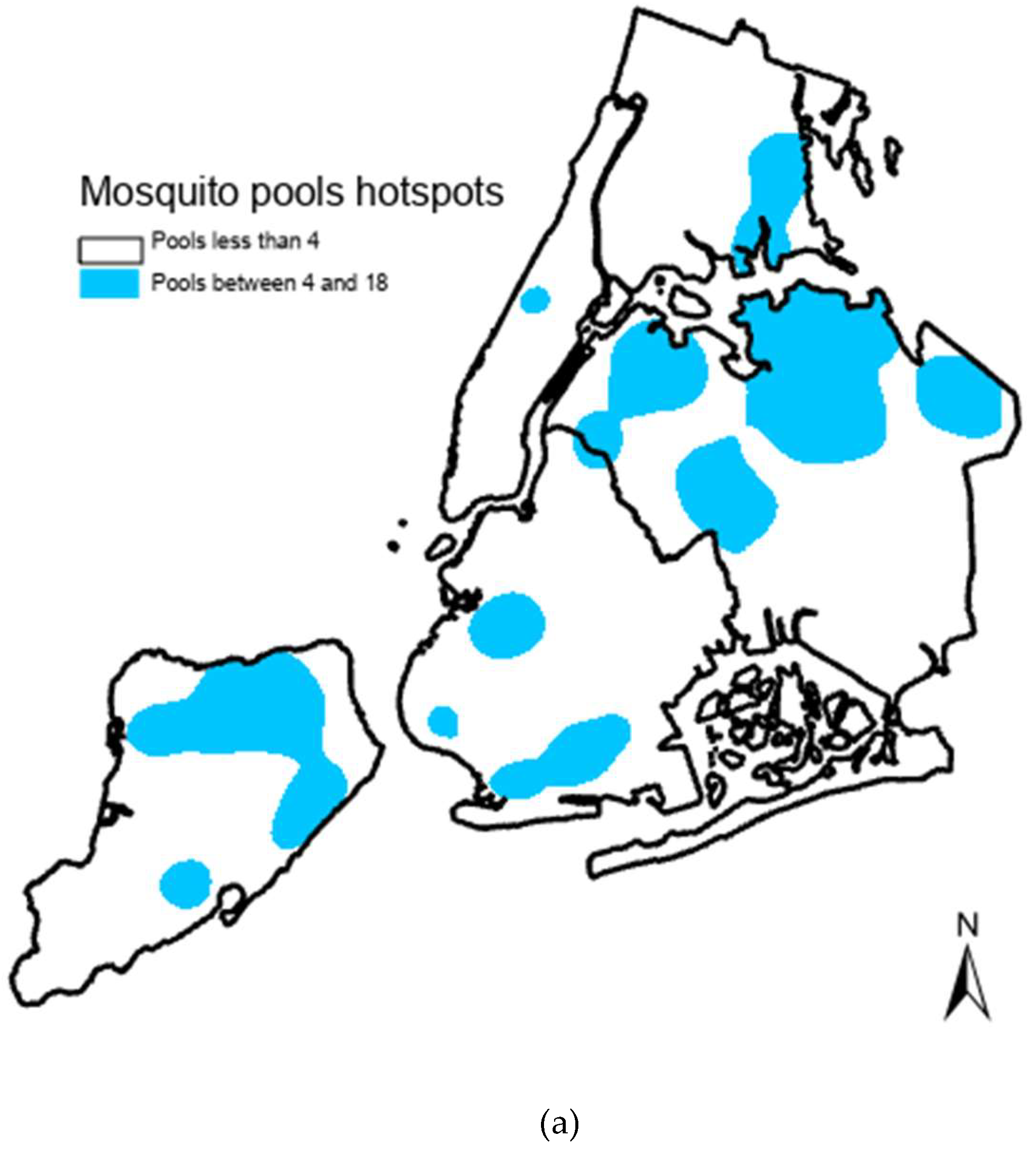

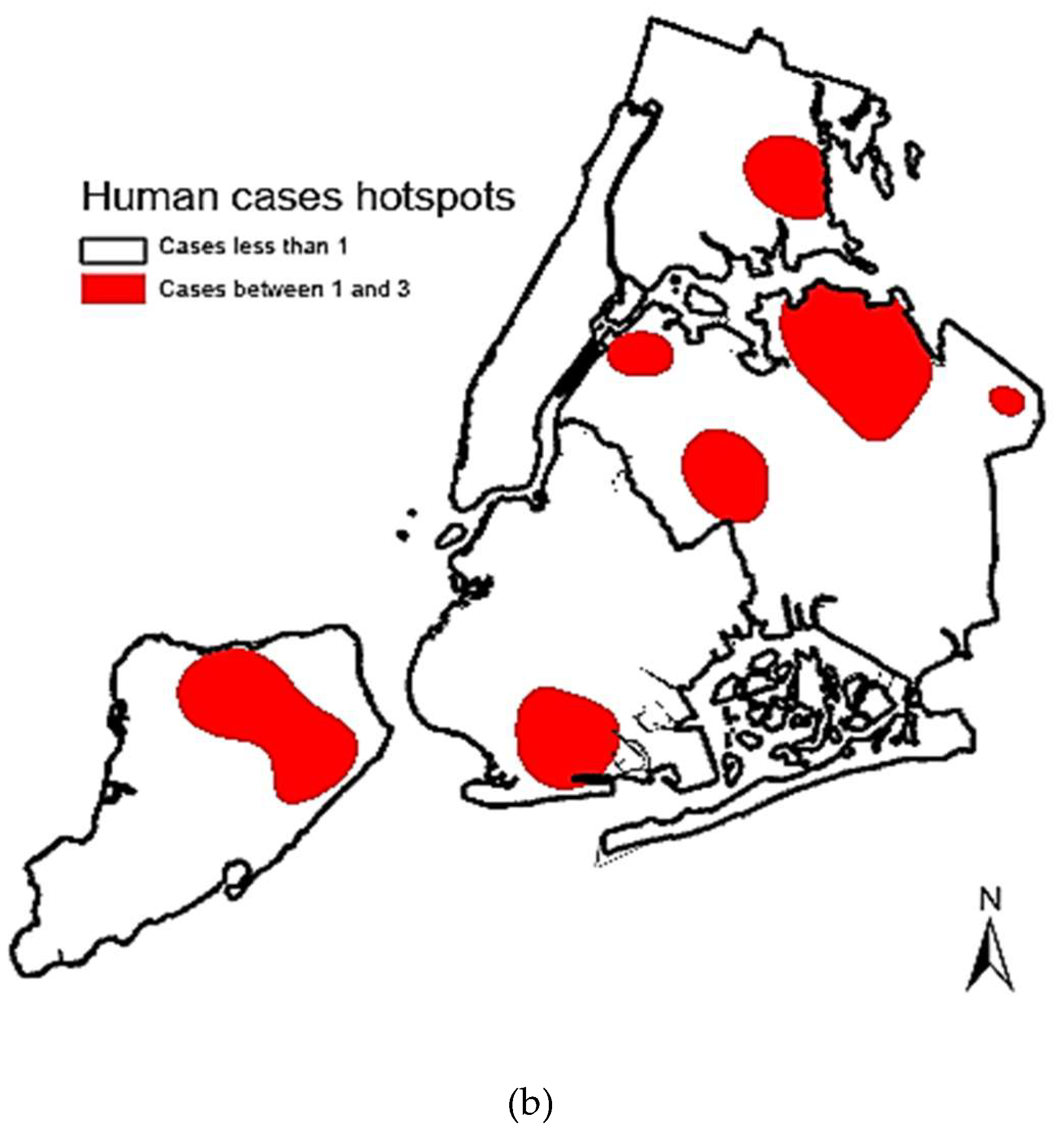

The 1999 West Nile Virus (WNV) outbreak in NYC marked the first introduction of the virus into the Western Hemisphere. This study examines two decades (2000-2019) of surveillance data, analyzing human cases (381 cases, 35 fatalities) and mosquito pools (6,632 positive pools). Findings highlight the dominant role of Culex species, particularly Cx. salinarius, in human transmission, with 69% of cases occurring near infected mosquito pools. Spatial analyses reveal transmission hotspots, emphasizing the importance of species-specific mosquito control. These insights contribute to refining urban vector management and public health strategies against WNV outbreaks.

Keywords:

Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Surveillance and Data Collection

2.4. Statistical and Spatial Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

|

Year |

Human Cases Classification | Number of positive mosquito pools | Pools associated with human cases *** | ||||||||

| Human Cases | Confirmed Local human cases * | Human cases with positive mosquito pools within a 5-mile radius** | Cx. pipiens & Cx. restuans | Cx. salinarius | Other species | Total positive pools | Cx. pipiens & Cx. restuans | Cx. salinarius | Other species | Total associated positives pools | |

| 2000 | 14 | 10 | 9 | 105 | 32 | 28 | 165 | 12 | 21 | 5 | 38 |

| 2001 | 9 | 5 | 3 | 210 | 24 | 9 | 243 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| 2002 | 29 | 21 | 8 | 151 | 35 | 13 | 199 | 18 | 23 | 0 | 41 |

| 2003 | 32 | 25 | 22 | 234 | 35 | 8 | 277 | 40 | 33 | 0 | 73 |

| 2004 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 148 | 10 | 26 | 184 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2005 | 14 | 13 | 9 | 119 | 3 | 0 | 122 | 17 | 3 | 0 | 20 |

| 2006 | 12 | 12 | 9 | 167 | 15 | 14 | 196 | 43 | 11 | 3 | 57 |

| 2007 | 18 | 17 | 4 | 159 | 12 | 3 | 174 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| 2008 | 15 | 15 | 8 | 182 | 9 | 6 | 197 | 15 | 3 | 1 | 19 |

| 2009 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 39 | 1 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2010 | 42 | 41 | 34 | 375 | 18 | 0 | 393 | 108 | 19 | 0 | 127 |

| 2011 | 11 | 11 | 7 | 170 | 9 | 2 | 181 | 11 | 9 | 1 | 21 |

| 2012 | 41 | 40 | 24 | 288 | 24 | 0 | 312 | 40 | 17 | 0 | 57 |

| 2013 | 10 | 9 | 3 | 236 | 11 | 2 | 249 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 9 |

| 2014 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 350 | 12 | 9 | 371 | 32 | 4 | 1 | 37 |

| 2015 | 38 | 32 | 26 | 789 | 32 | 6 | 827 | 158 | 31 | 3 | 192 |

| 2016 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 280 | 2 | 0 | 282 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 2017 | 21 | 20 | 13 | 759 | 24 | 3 | 786 | 49 | 9 | 0 | 58 |

| 2018 | 36 | 34 | 31 | 928 | 69 | 27 | 1,024 | 119 | 53 | 11 | 183 |

| 2019 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 370 | 35 | 5 | 410 | 16 | 14 | 0 | 30 |

| Total | 381 | 338 | 233 | 6,059 | 412 | 161 | 6,632 | 708 | 251 | 27 | 986 |

| Characteristic | Cx. pipiens and Cx. restuans | Cx. salinarius | Other Species |

| Mosquito pools associated with human cases | 708 | 251 | 27 |

| Percentage of all positive pools for each species (%) | 11.69% | 60.92% | 16.77% |

| Number of human cases associated | 193 | 124 | 21 |

| Human cases with only one positive mosquito species | 106 | 38 | 2 |

| Average distance to human cases (miles) | 1.25 | 3.22 | 2.47 |

| Percentage of mosquito pools associated with human cases within 1 mile (%) | 22.21% | 1.62% | 0.61% |

| Percentage within 1–2 miles (%) | 49.59% | 2.33% | 0.91% |

| Percentage within 2–5 miles (%) | 0 | 21.5% | 1.22% |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Bajwa, W.I. A taxonomic checklist and relative abundance of the mosquitoes of New York City. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 2018, 34, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, W.I.; Merlino, M. Application of relational Bayesian networks to vector control in New York City. International Journal of Infectious Diseases & Epidemiology 2021, 2, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ronca, S.E.; Ruff, J.C.; Murray, K.O. A 20-year historical review of West Nile virus since its initial emergence in North America: Has West Nile virus become a neglected tropical disease? PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2021, 15, e0009190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, L.D.; Ciota, A.T.; Kilpatrick, A.M. Introduction, spread, and establishment of West Nile virus in the Americas. Journal of Medical Entomology 2019, 56, 1448–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilpatrick, A.M. Globalization, land use, and the invasion of West Nile virus. Science 2011, 334, 323–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, S. Effects of climate change on vector-borne diseases: An updated focus on West Nile virus in humans. Emerging Topics in Life Sciences 2019, 3, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaff, N.K.; Cheruvelil, K.S.; Nateghi, R. Predicting the influence of climate change on West Nile virus transmission: A machine learning approach. Environmental Research 2020, 186, 109527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubaugh, N.D.; Ebel, G.D.; Goebel, S.H.; Weger-Lucarelli, J.; Kuhn, J.H.; Brault, A.C. Genomic epidemiology reveals multiple introductions of West Nile virus into the United States and adaptive evolution. PLoS Pathogens 2019, 15, e1007678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraguti, M.; Magallanes, S.; Mora-Rubio, C.; Bravo-Barriga, D.; Marzal, A.; Hernandez-Caballero, I.; Aguilera-Sepúlveda, P.; Llorente, F.; Pérez-Ramírez, E.; Guerrero-Carvajal, F.; Jiménez-Clavero, M.Á.; Frontera, E.; Ortiz, J.A.; de Lope, F. Implications of migratory and exotic birds and the mosquito community on West Nile virus transmission. Infectious Diseases 2023, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrzljak, A.; Dinjar-Kujundzic, P.; Santini, M.; Barbić, L.; Košuta, I.; Savić, V.; Tabain, I.; Vilibić-Čavlek, T. West Nile virus: An emerging threat in the transplant population. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases 2020, 20, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, R.M.; Ahearn, S.C.; McConchie, A.; Glaser, C.; Jean, C.; Barker, C.; Park, B.; Padgett, K.; Parker, E.; Aquino, E.; Kramer, V. Early warning system for West Nile virus risk areas, California, USA. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2011, 17, 1445–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeGroote, J.P.; Sugumaran, R.; Brend, S.M.; Tucker, B.J.; Bartholomay, L.C. Landscape, demographic, entomological, and climatic associations with human disease incidence of West Nile virus in the state of Iowa, USA. International Journal of Health Geographics 2008, 7, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komar, N. West Nile virus: Epidemiology and ecology in North America. Advances in Virus Research 2006, 61, 185–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidecke, J.; Lavarello Schettini, A.; Rocklöv, J. West Nile virus ecoepidemiology and climate change. PLOS Climate 2023, 2, e0000129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, J.R.; Chaves, L.F.; Armstrong, P.M. Ecological predictors of mosquito population and arbovirus transmission synchrony estimates. Journal of Medical Entomology 2023, 60, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggal, N.K.; Langwig, K.E.; Ebel, G.D.; Brault, A.C. On the fly: Interactions between birds, mosquitoes, and the environment that have molded West Nile virus genomic structure over two decades. Journal of Medical Entomology 2019, 56, 1467–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajwa, W.I.; Slavinski, S.; Shah, Z.; Zhou, L.; Bazli, T.V. Comprehensive mosquito surveillance and control plan. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene 2025, New York, NY. Retrieved from https://www.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/wnv/2025/wnvplan2025.

- Farajollahi, A.; Fonseca, D.M.; Kramer, L.D.; Kilpatrick, A.M. (2011). ‘Bird biting’ mosquitoes and human disease: A review of the role of Culex pipiens complex mosquitoes in epidemiology. Infection, Genetics, and Evolution 2011, 11, 1577–1585. [Google Scholar]

- Eder, M.; Cortes, F.; Teixeira de Siqueira Filha, N.; Araújo de França, G.V.; Degroote, S.; Braga, C.; Turchi Martelli, C.M. Scoping review on vector-borne diseases in urban areas: Transmission dynamics, vectorial capacity, and coinfection. Infectious Diseases of Poverty 2018, 7, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, J.L.; Park, B.; Carpenter, K.; Ngo, T.E.; Civen, R.; Reisen, W.K. Comparison of enzootic risk measures for predicting West Nile disease, Los Angeles, California, USA, 2004–2010. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2012, 18, 1298–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciota, A.T.; Drummond, C.L.; Ruby, M.A.; Drobnack, J.; Ebel, G.D.; Kramer, L.D. Dispersal of Culex mosquitoes (Diptera: Culicidae) from a wastewater treatment facility. Journal of Medical Entomology 2012, 49, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdonschot, A.M.; Besse-Lototskaya, A.A. Flight distance of mosquitoes (Culicidae): A metadata analysis to support the management of barrier zones around rewetted and newly constructed wetlands. Limnologica 2014, 45, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, G.L.; Kitron, U.D.; Goldberg, T.L.; Brawn, J.D.; Loss, S.R.; Ruiz, M.O.; Hayes, D.B.; Walker, E.D. Host selection by Culex mosquitoes and its role in arbovirus transmission. Journal of Vector Ecology 2008, 33, 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick, A.M.; Kramer, L.D.; Jones, M.J.; Marra, P.P.; Daszak, P. West Nile virus epidemics in North America are driven by shifts in mosquito feeding behavior. PLoS Biology 2006, 4, e82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilpatrick, A.M.; Pape, W.J. Predicting human West Nile virus infections with mosquito surveillance data. American Journal of Epidemiology 2013, 178, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccetti, N.; Fasano, A.; Ferraccioli, F.; Gomez Ramirez, J.; Stilianakis, N.I. Host selection and forage ratio in West Nile virus–transmitting Culex mosquitoes: Challenges and knowledge gaps. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2022, 16, e0010819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, K.R.; Johnson, M.P.; Hayes, D.E. The role of Culex salinarius in West Nile virus transmission: An urban perspective. Journal of Vector Ecology 2024, 49, 157–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amely, M.B.; Nathan, D.B.; Lawrence, E.R.; Barry, W.A.; Lindsay, P.C. Vector potential index: Bridging competence and contribution as an integrative measure of relative transmission capability. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Weaver, S.C.; Charlier, C.; Vasilakis, N.; Lecuit, M. Zika, chikungunya, and other emerging vector-borne viral diseases. Annual Review of Medicine 2018, 69, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochlin, I.; Faraji, A.; Healy, K.; Andreadis, T.G. West Nile virus mosquito vectors in North America. Journal of Medical Entomology 2019, 56, 1475–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauver, J.R.; Pecher, L.; Schurich, J.A.; Bolling, B.G.; Calhoon, M.; Grubaugh, N.D.; Burkhalter, K.L.; Eisen, L.; Andre, B.G.; Nasci, R.S.; Lebailly, A.; Ebel, G.D.; Moore, C.G. Temporal and spatial variability of entomological risk indices for West Nile virus infection in northern Colorado: 2006–2013. Journal of Medical Entomology 2015, 53, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benelli, G.; Canale, A.; Higuchi, A.; Murugan, K.; Pavela, N.M. The recent outbreaks of Zika virus: Mosquito control faces a further challenge. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease 2016, 6, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2012). Global strategy for dengue prevention and control 2012–2020. WHO Press. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/75303/9789241504034_eng.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).