Submitted:

22 January 2025

Posted:

24 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Though a variety of methods are used to conduct West Nile virus (WNV) surveillance, accurate prediction and prevention of outbreaks remains a global challenge. Previous studies have established that the concentration of antibodies to mosquito saliva is directly related to the intensity of exposure to mosquito bites and can be a good proxy to determine risk of infection in human populations. To assess exposure characteristics and transmission dynamics among avian communities, we tested the levels of IgY antibodies against whole salivary glands of Aedes albopictus and Culex quinquefasciatus, as well as WNV antigen, in 300 Northern cardinals sampled from April 2019 to October 2019 in St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana. Though there were no significant differences in antibody responses among sex or age groups, exposure to Ae. albopictus bites was more positively associated with exposure to WNV compared with Cx. quinquefasciatus exposure (ρ = 0.2525, p <0.001; ρ = 0.1752, p = 0.02437). This association was more pronounced among female birds (ρ = 0.3004, p = 0.0075), while no significant relationship existed between exposure to either mosquito vector and WNV among male birds in the study. In general, two seasonal trends in exposure were found, noting that exposure to Ae. albopictus becomes less intense throughout the season (ρ = -0.1529, p = 0.04984), while recaptured birds in the study were found to have increased exposure to Cx. quinquefasciatus by the end of the season (ρ = 0.277, p = 0.0468). Additionally, we report the identification of several immunogenic salivary proteins, including D7 family proteins, from both mosquito vectors among the birds. Our results suggest the role of Ae. albopictus as an early season enzootic vector of WNV, facilitated by Northern cardinal breeding behaviors, enhancing the potential to increase infections among Cx. quinquefasciatus mosquitoes in the late season contributing to human disease incidence and epizootic spillover in the environment.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Aedes albopictus and Culex quinquefasciatus Mosquito Rearing and Salivary Gland Extract (SGE) Preparation

2.3. ELISA Testing Against Culex quinquefasciatus and Aedes albopictus Salivary Gland Extract

2.4. ELISA Testing Against West Nile Virus Whole Cell Lysate Antigen

2.5. Mosquito SGE Protein Electrophoresis and Immunoblotting

2.6. In-Gel Digestion and LCMS Preparation

2.7. Protein Identification

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of the Study Population

3.2. WNV-Infected Mosquito Pools

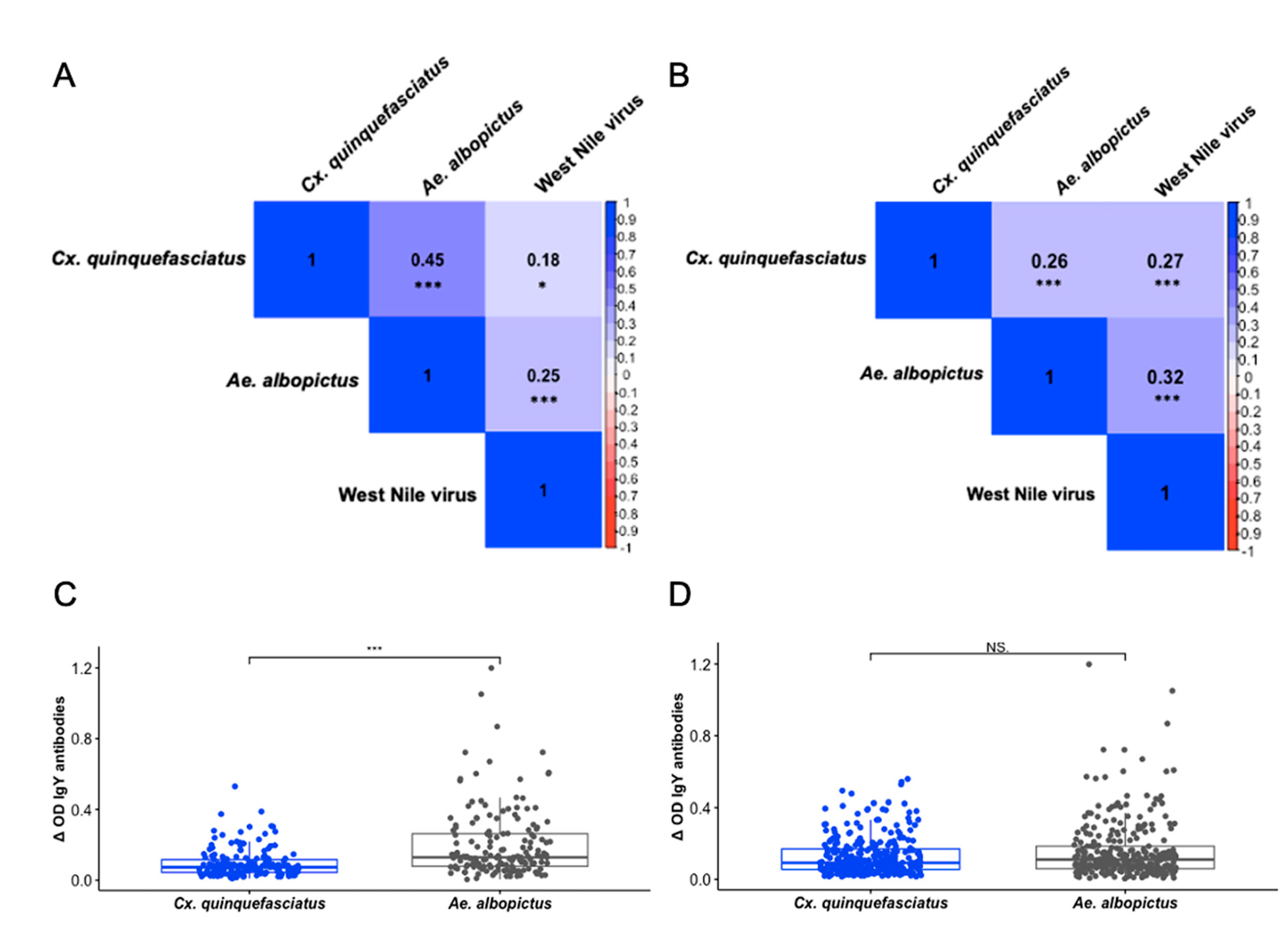

3.3. IgY Responses Are Associated Among Culex quinquefasciatus, Aedes albopictus, and West Nile Virus

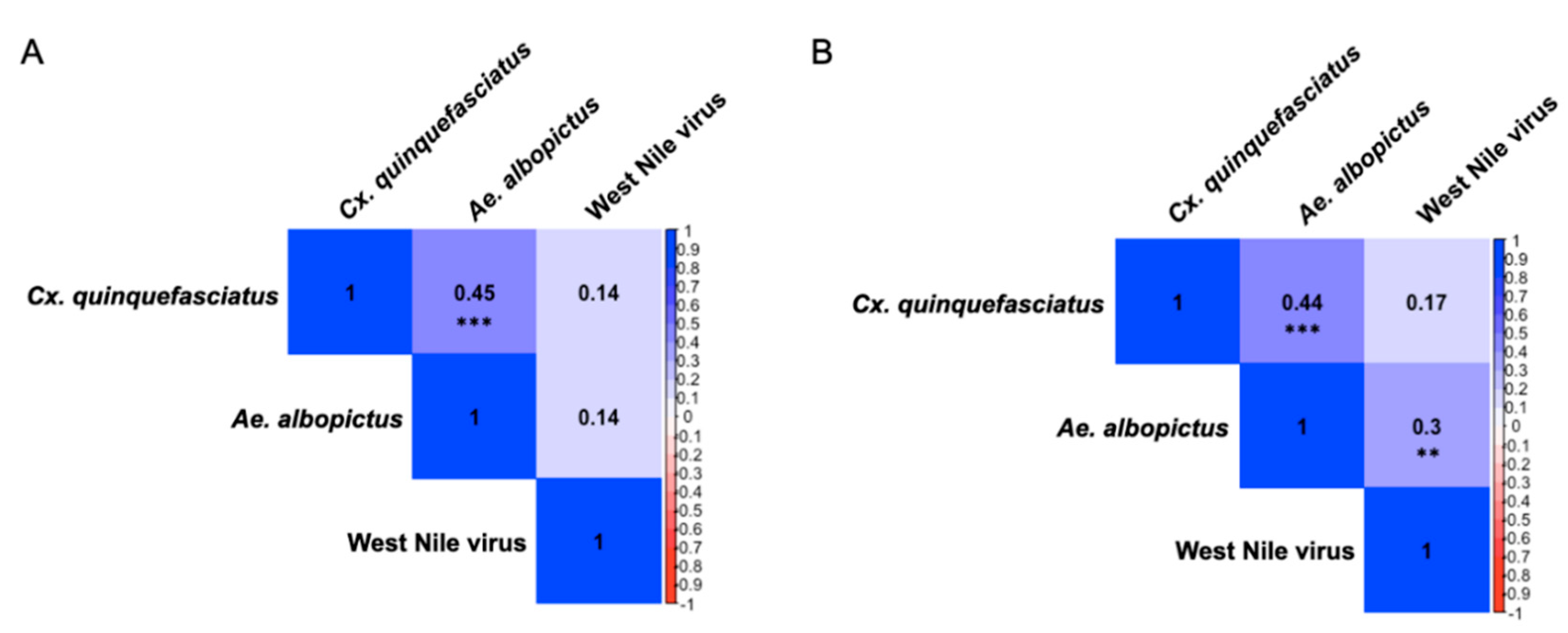

3.4. Presence of Sex-Specific Associations of IgY Response to Aedes albopictus and West Nile virus

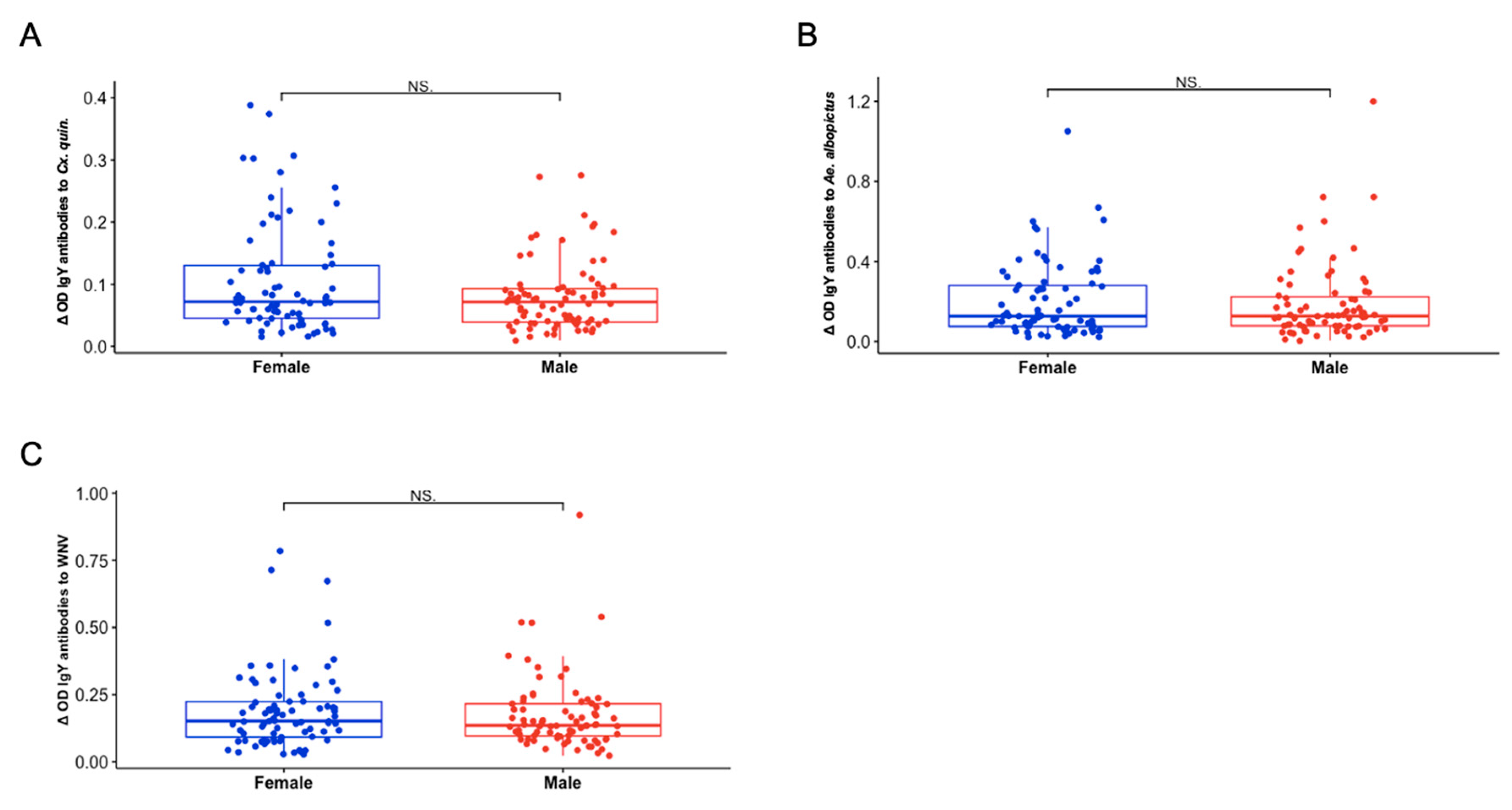

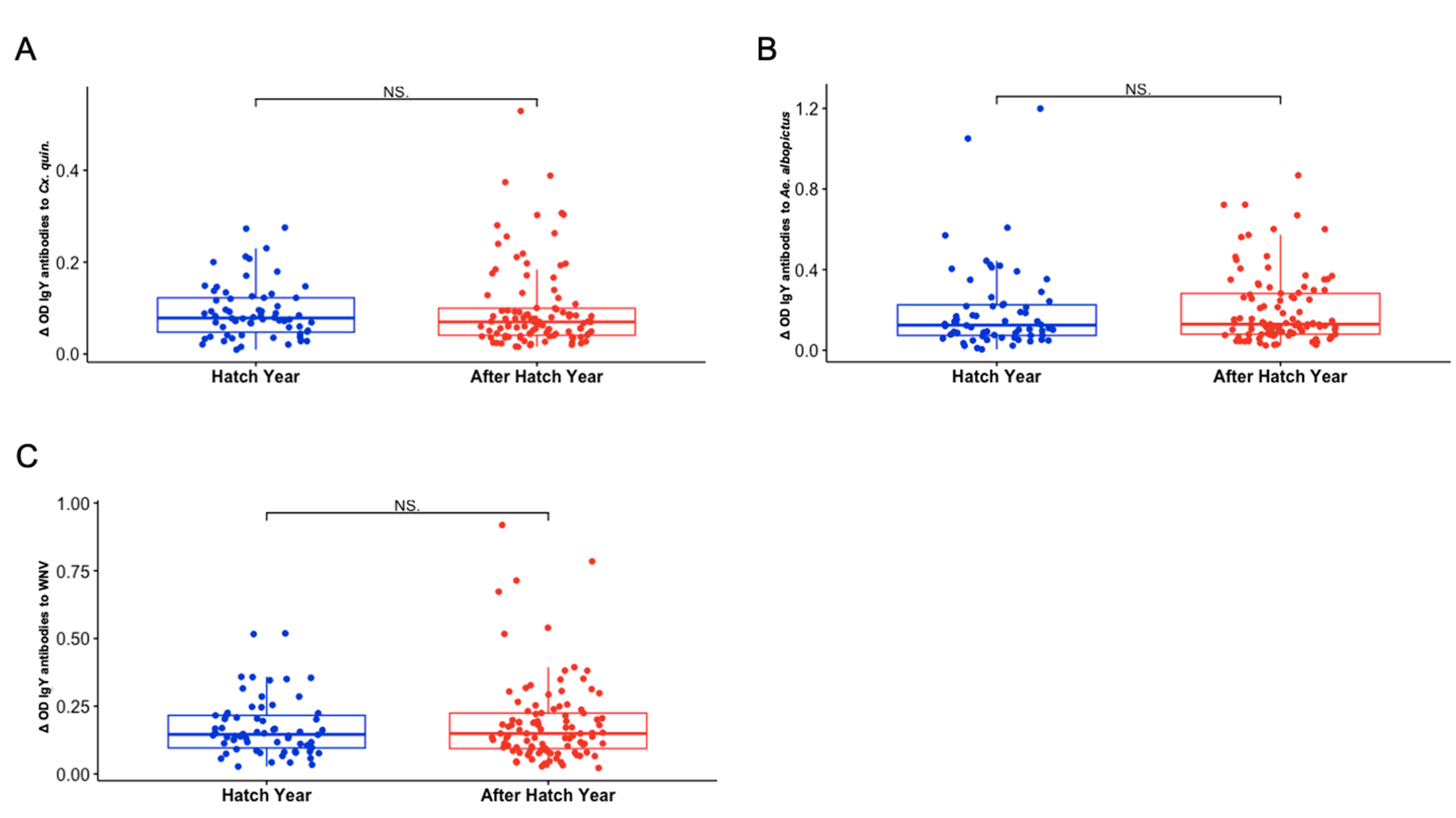

3.5. Sex and Hatch Year Are Not Important Variables Defining Exposure to Aedes albopictus or Culex quinquefasciatus Mosquito Bites Among Northern Cardinals

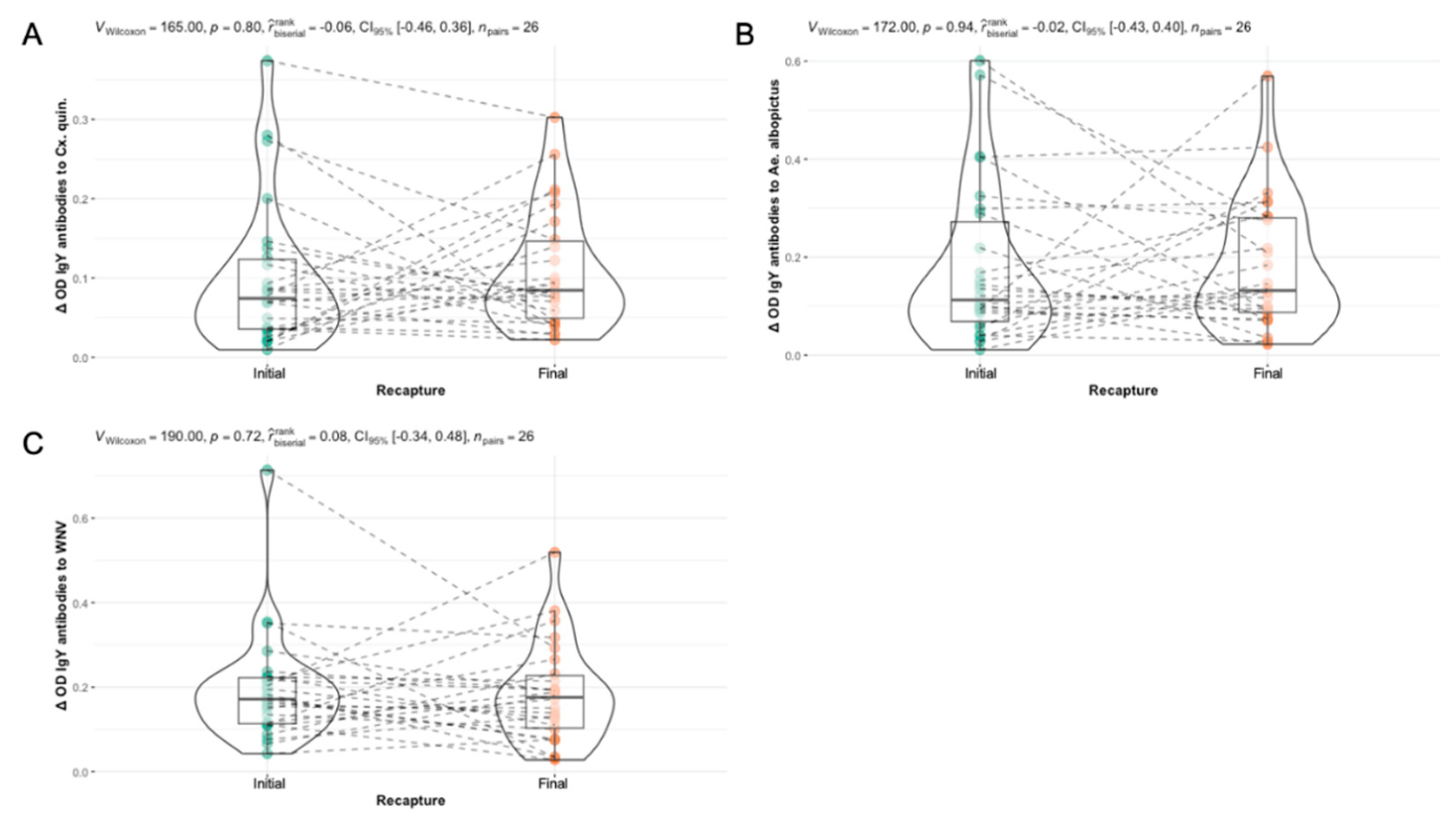

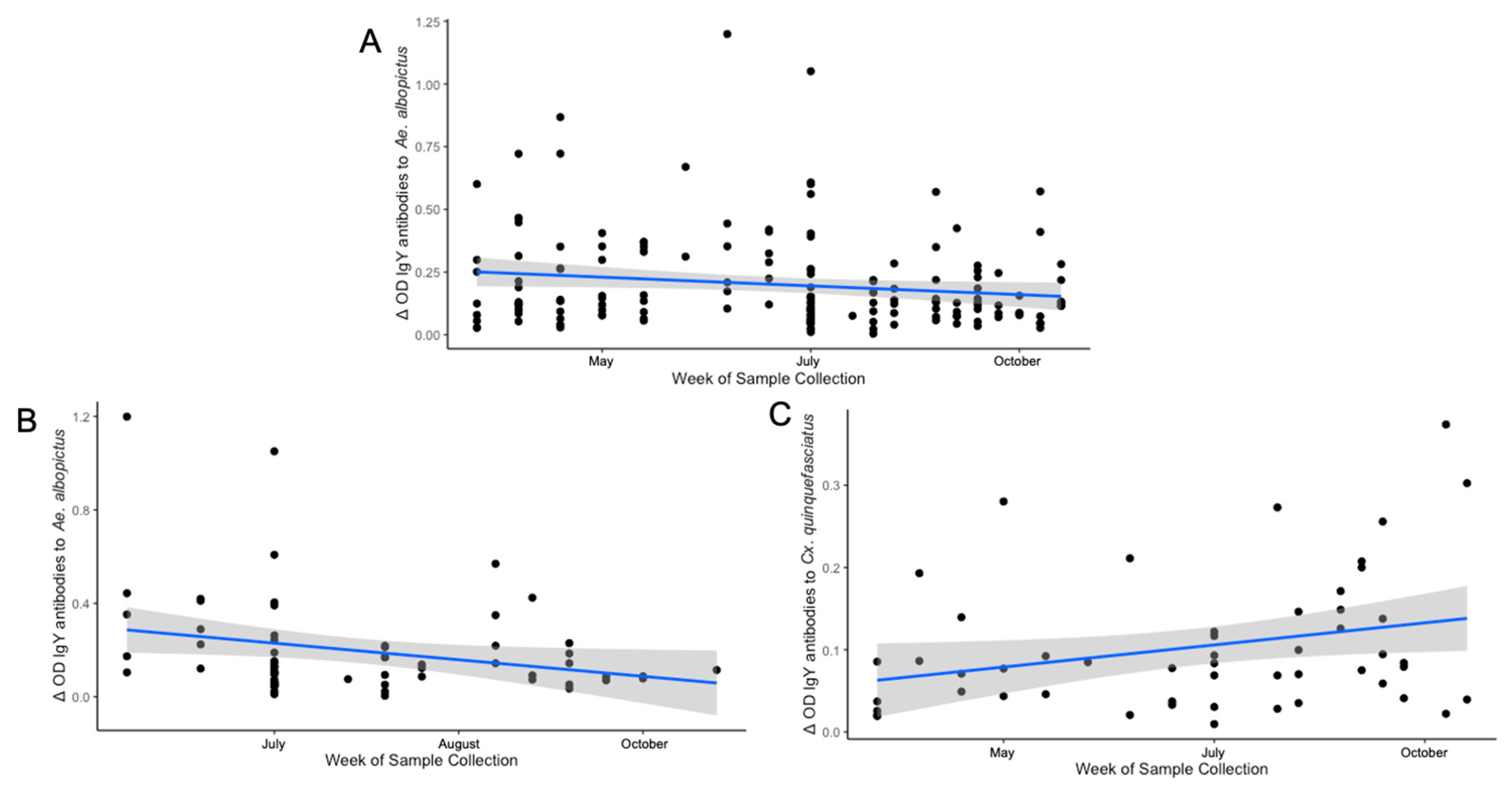

3.6. Differences in Seasonal Exposure to Aedes albopictus and Culex quinquefasciatus Among Northern Cardinals

| Cx. quinquefasciatus | Ae. albopictus | West Nile virus | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Birds (n = 165) | 0.0797 p = 0.3087 |

-0.1529 p = 0.04984* |

0.0606 p = 0.4394 |

| After Hatch Year (n = 101) | 0.0599 p = 0.5513 |

-0.0826 p = 0.4117 |

0.1215 p = 0.2262 |

| Hatch Year (n = 64) | 0.1546 p = 0.2226 |

-0.2482 p = 0.04799* |

-0.0277 p = 0.828 |

| Male (n = 80) | -0.0277 p = 0.828 |

-0.1709 p = 0.1295 |

0.0093 p = 0.9349 |

| Female (n = 78) | 0.1592 p = 0.1639 |

-0.1185 p = 0.3015 |

0.1099 p = 0.3377 |

| Recaptured Birds (n = 52)1 |

0.2770 p = 0.0468* |

-0.0132 p = 0.9259 |

0.1126 p = 0.4267 |

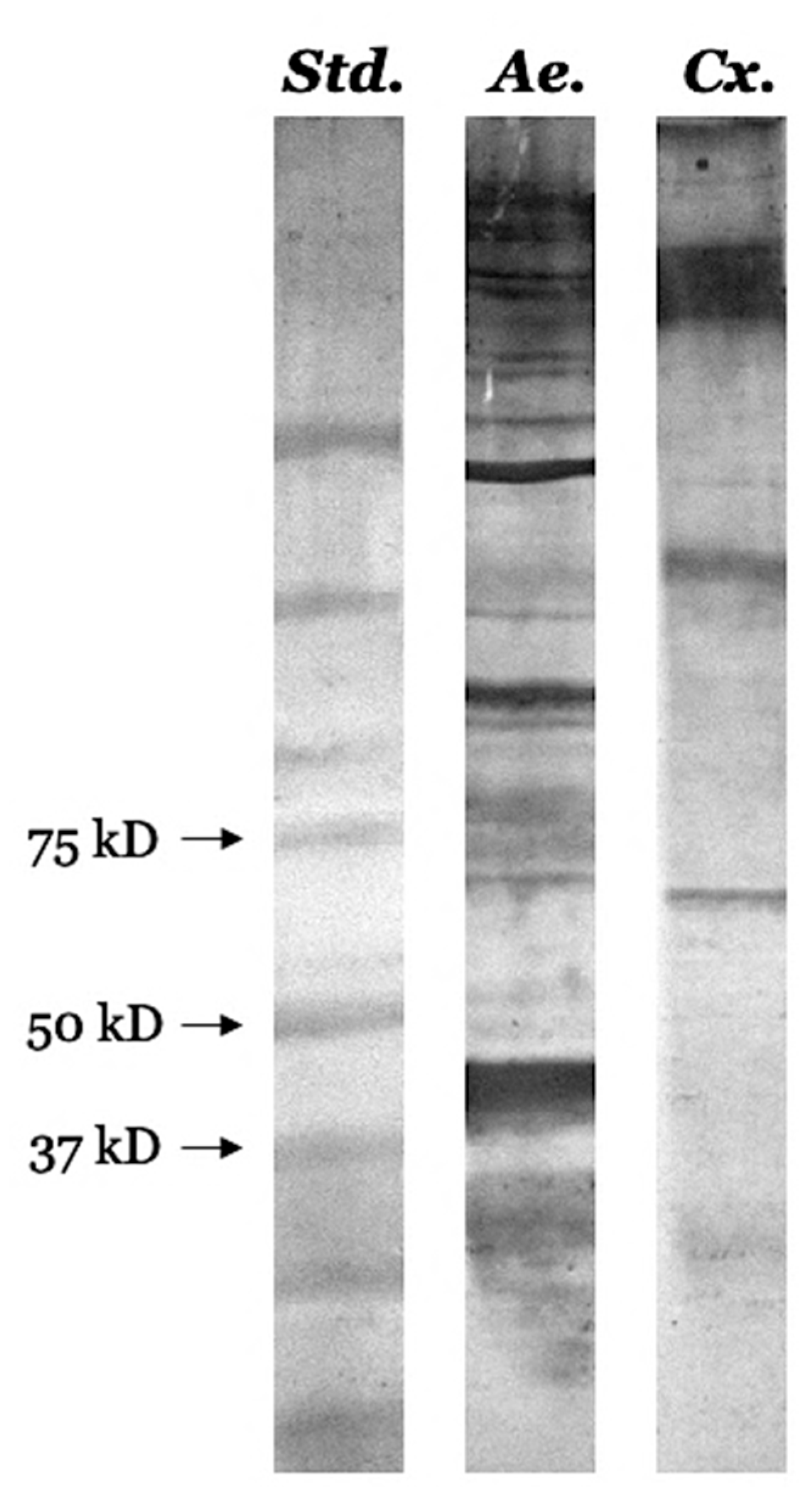

3.7. Identification of Several Pharmacologically Active Immunogenic Proteins

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABC | Ammonium bicarbonate |

| ACN | Acetonitrile |

| Ae. | Aedes |

| Cx. | Culex |

| ELISA | Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay |

| FA | Ferulic acid |

| IAA | Indole-3-acetic acid |

| IgY | Immunoglobulin Y |

| LCMS | Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| OD | Optical density |

| PBS | Phosphate buffered saline |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride |

| SGE | Salivary gland extract |

| WNV | West Nile virus |

References

- CDC Epidemiology and Ecology | Mosquitoes | . (2022, June 29). https://www.cdc.gov/mosquitoes/guidelines/west-nile/epidemiology-ecology.html.

- Hayes, E.B.; Komar, N.; Nasci, R.S.; Montgomery, S.P.; O’Leary, D.R.; Campbell, G.L. Epidemiology and Transmission Dynamics of West Nile Virus Disease. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2005, 11, 1167–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komar, N.; Langevin, S.; Hinten, S.; Nemeth, N.; Edwards, E.; Hettler, D.; Davis, B.; Bowen, R.; Bunning, M. Experimental Infection of North American Birds with the New York 1999 Strain of West Nile Virus. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2003, 9, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, R.S.; Mead, D.G.; Kitron, U.D. Limited Spillover to Humans from West Nile Virus Viremic Birds in Atlanta, Georgia. Vector Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 2013, 13, 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraji, A.; Egizi, A.; Fonseca, D.M.; Unlu, I.; Crepeau, T.; Healy, S.P.; Gaugler, R. Comparative Host Feeding Patterns of the Asian Tiger Mosquito, Aedes albopictus, in Urban and Suburban Northeastern USA and Implications for Disease Transmission. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2014, 8, e3037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, R.A.; West, P.A.; Lindsay, S.W. Suitability of two carbon dioxide-baited traps for mosquito surveillance in the United Kingdom. Bulletin of Entomological Research. 2007, 97, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, H.M.; Niebylski, M.L.; Smith, G.C.; Mitchell, C.J.; Craig, G.B., Jr. Host-Feeding Patterns of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) at a Temperate North American Site. Journal of Medical Entomology. 1993, 30, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vouillon, A.; Barthelemy, J.; Lebeau, L.; Nisole, S.; Savini, G.; Lévêque, N.; Simonin, Y.; Garcia, M.; Bodet, C. Skin tropism during Usutu virus and West Nile virus infection: An amplifying and immunological role. Journal of Virology. 2023, 98, e01830-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, S.L.; Ross, T.M.; Evans, J.D. West Nile Virus. Clinics in Laboratory Medicine. 2010, 30, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratard, R. (2021). West Nile Virus Annual Report.

- Rochlin, I.; Faraji, A.; Healy, K.; Andreadis, T.G. West Nile Virus Mosquito Vectors in North America. Journal of Medical Entomology. 2019, 56, 1475–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West Nile Virus | La Dept. Of Health. (n.d.). Retrieved May 16. 2024, from https://ldh.la.gov/page/west-nile-virus.

- Louisiana Arbovirus Surveillance Summary 2020. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://ldh.la.gov/assets/oph/Center-PHCH/Center-CH/infectious-epi/Arboviral/arboweekly/2020_wnv_reports/ARBO_2049.pdf.

- West Nile Virus | La Dept. Of Health. (n.d.). Retrieved May 16. 2024, from https://ldh.la.gov/assets/oph/Center-PHCH/Center-CH/infectious-epi/Arboviral/arboweekly/2023_WNV_Reports/ARBO_2352.pdf.

- Reagan, K.L.; Machain-Williams, C.; Wang, T.; Blair, C.D. Immunization of Mice with Recombinant Mosquito Salivary Protein D7 Enhances Mortality from Subsequent West Nile Virus Infection via Mosquito Bite. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2012, 6, e1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londono-Renteria, B.L.; Eisele, T.P.; Keating, J.; James, M.A.; Wesson, D.M. Antibody Response Against Anopheles albimanus (Diptera: Culicidae) Salivary Protein as a Measure of Mosquito Bite Exposure in Haiti. Journal of Medical Entomology. 2010, 47, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Londono-Renteria, B.; Cardenas, J.C.; Cardenas, L.D.; Christofferson, R.C.; Chisenhall, D.M.; Wesson, D.M.; McCracken, M.K.; Carvajal, D.; Mores, C.N. Use of Anti-Aedes aegypti Salivary Extract Antibody Concentration to Correlate Risk of Vector Exposure and Dengue Transmission Risk in Colombia. PLOS ONE. 2013, 8, e81211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldonado-Ruiz, L.P.; Montenegro-Cadena, L.; Blattner, B.; Menghwar, S.; Zurek, L.; Londono-Renteria, B. Differential Tick Salivary Protein Profiles and Human Immune Responses to Lone Star Ticks (Amblyomma americanum) From the Wild vs. A Laboratory Colony. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, A.I.; Gould, H.J.; Sutton, B.J.; Calvert, R.A. Avian IgY Binds to a Monocyte Receptor with IgG-like Kinetics Despite an IgE-like Structure *. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008, 283, 16384–16390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Syed Atif, A.; Tan, S.C.; Leow, C.H. Insights into the chicken IgY with emphasis on the generation and applications of chicken recombinant monoclonal antibodies. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2017, 447, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco, B.L.B.; Nogueira, C.P.; Venancio, E.J. IgY Antibodies from Birds: A Review on Affinity and Avidity. Animals. 2023, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Londono-Renteria, B.; Patel, J.C.; Vaughn, M.; Funkhauser, S.; Ponnusamy, L.; Grippin, C.; Jameson, S.B.; Apperson, C.; Mores, C.N.; Wesson, D.M.; Colpitts, T.M.; Meshnick, S.R. Long-Lasting Permethrin-Impregnated Clothing Protects Against Mosquito Bites in Outdoor Workers. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 2015, 93, 869–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, J.E.; Holton, D.; Liu, J.; McMurdo, H.; Murciano, A.; Gohd, R. A novel enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the detection of antibodies to HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins based on immobilization of viral glycoproteins in microtiter wells coated with concanavalin A. Journal of immunological methods 1990, 132, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team (2024). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

- Patil, I. Visualizations with statistical details: The 'ggstatsplot' approach. Journal of Open Source Software. 2021, 6, 3167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcà, B.; Struchiner, C.J.; Pham, V.M.; Sferra, G.; Lombardo, F.; Pombi, M.; Ribeiro, J.M.C. Positive selection drives accelerated evolution of mosquito salivary genes associated with blood-feeding. Insect Molecular Biology. 2014, 23, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diniz, D.F.A.; de Albuquerque, C.M.R.; Oliva, L.O.; de Melo-Santos, M.A.V.; Ayres, C.F.J. Diapause and quiescence: Dormancy mechanisms that contribute to the geographical expansion of mosquitoes and their evolutionary success. Parasites & Vectors. 2017, 10, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doucoure, S.; Mouchet, F.; Cournil, A.; Goff, G.L.; Cornelie, S.; Roca, Y.; Giraldez, M.G.; Simon, Z.B.; Loayza, R.; Misse, D.; Flores, J.V.; Walter, A.; Rogier, C.; Herve, J.P.; Remoue, F. Human Antibody Response to Aedes aegypti Saliva in an Urban Population in Bolivia: A New Biomarker of Exposure to Dengue Vector Bites. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2012, 87, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montiel, J.; Carbal, L.F.; Tobón-Castaño, A.; Vásquez, G.M.; Fisher, M.L.; Londono-Rentería, B. IgG antibody response against Anopheles salivary gland proteins in asymptomatic Plasmodium infections in Narino, Colombia. Malaria Journal. 2020, 19, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buezo Montero, S.; Gabrieli, P.; Montarsi, F.; Borean, A.; Capelli, S.; De Silvestro, G.; Forneris, F.; Pombi, M.; Breda, A.; Capelli, G.; Arcà, B. IgG Antibody Responses to the Aedes albopictus 34k2 Salivary Protein as Novel Candidate Marker of Human Exposure to the Tiger Mosquito. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamer, G.L.; Walker, E.D.; Brawn, J.D.; Loss, S.R.; Ruiz, M.O.; Goldberg, T.L.; Schotthoefer, A.M.; Brown, W.M.; Wheeler, E.; Kitron, U.D. Rapid amplification of West Nile virus: the role of hatch-year birds. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008, 8, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdebenito, J.O.; Halimubieke, N.; Lendvai, Á.Z.; Figuerola, J.; Eichhorn, G.; Székely, T. Seasonal variation in sex-specific immunity in wild birds. Scientific Reports. 2021, 11, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, J.C.; Nakamura, A.; Coon, C.A.; Martin, L.B. The effect of exogenous corticosterone on West Nile virus infection in Northern Cardinals (Cardinalis cardinalis). Veterinary Research. 2012, 43, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breeding—Northern Cardinal—Cardinalis cardinalis—Birds of the World. (n.d.). Retrieved December 3, 2024, from https://birdsoftheworld.org/bow/species/norcar/cur/breeding.

- Lampman, R.L.; Krasavin, N.M.; Ward, M.P.; Beveroth, T.A.; Lankau, E.W.; Alto, B.W.; Muturi, E.; Novak, R.J. West Nile Virus Infection Rates and Avian Serology in East-Central Illinois. Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association. 2013, 29, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West Nile Virus Antibodies in Avian Species of Georgia, USA: 2000–2004. (n.d.). [CrossRef]

- Kaspers, B.; Göbel, T.W.; Schat, K.A.; Vervelde, L. Avian Immunology (3rd ed.) (Academic Press, 2022).

- Lamb, J.S.; Tornos, J.; Lejeune, M.; Boulinier, T. Rapid loss of maternal immunity and increase in environmentally mediated antibody generation in urban gulls. Scientific Reports. 2024, 14, 4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiawsirisup, S.; Platt, K.B.; Evans, R.B.; Rowley, W.A. A Comparision of West Nile Virus Transmission by Ochlerotatus trivittatus (COQ.), Culex pipiens (L.), and Aedes albopictus (Skuse). Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 2005, 5, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Root, J.J.; Bosco-Lauth, A.M. West Nile Virus Associations in Wild Mammals: An Update. Viruses. 2019, 11, Article 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egizi, A.M.; Farajollahi, A.; Fonseca, D.M. Diverse Host Feeding on Nesting Birds May Limit Early-Season West Nile Virus Amplification. Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 2014, 14, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komar, N.; Panella, N.A.; Langevin, S.A.; Brault, A.C.; Amador, M.; Edwards, E.; Owen, J.C. AVIAN HOSTS FOR WEST NILE VIRUS IN ST. TAMMANY PARISH, LOUISIANA, 2002. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2005, 73, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obenauer, P.J.; Kaufman, P.E.; Allan, S.A.; Kline, D.L. Host-Seeking Height Preferences of Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in North Central Florida Suburban and Sylvatic Locales. Journal of Medical Entomology. 2009, 46, 900–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, R.S.; Mead, D.G.; Hamer, G.L.; Brosi, B.J.; Hedeen, D.L.; Hedeen, M.W.; McMillan, J.R.; Bisanzio, D.; Kitron, U.D. Supersuppression: Reservoir Competency and Timing of Mosquito Host Shifts Combine to Reduce Spillover of West Nile Virus. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2016, 95, 1174–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, H.M.; Anderson, M.; Gordon, E.; Mcmillen, L.; Colton, L.; Delorey, M.; Sutherland, G.; Aspen, S.; Charnetzky, D.; Burkhalter, K.; Godsey, M. Host-Seeking Heights, Host-Seeking Activity Patterns, and West Nile Virus Infection Rates for Members of the Culex pipiens Complex at Different Habitat Types Within the Hybrid Zone, Shelby County, TN, 2002 (Diptera: Culicidae). Journal of Medical Entomology 2008, 45, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Louisiana Arbovirus Surveillance Summary 2021. (2022, January 1). Retrieved from https://ldh.la.gov/assets/oph/Center-PHCH/Center-CH/infectious-epi/Arboviral/arboweekly/2021_WNV_Reports/ARBO_2152.pdf.

- Cendejas, P.M.; Goodman, A.G. Vaccination and Control Methods of West Nile Virus Infection in Equids and Humans. Vaccines. 2024, 12, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, J.R.; Hamer, G.L.; Levine, R.S.; Mead, D.G.; Waller, L.A.; Goldberg, T.L.; Walker, E.D.; Brawn, J.D.; Ruiz, M.O.; Kitron, U.; Vazquez-Prokopec, G. Multi-Year Comparison of Community- and Species-Level West Nile Virus Antibody Prevalence in Birds from Atlanta, Georgia and Chicago, Illinois, 2005–2016. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2023, 108, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Site n (%) |

1 | 2 | 3 |

| 116 (70.3) | 11 (6.7) | 38 (23) | |

|

Sex n (%) |

Male | Female | Not available |

| 80 (48.5) | 78 (47.3) | 7 (4.2) | |

|

Age n (%) |

Hatch Year | After Hatch Year | Not available |

| 64 (38.8) | 101 (61.2) | 0 (0) | |

|

Mass (g) |

Average | Minimum | Maximum |

| 39.022 | 3 | 46 |

| Protein Name | ID | MW (Da) |

|---|---|---|

|

Aedes albopictus ~38-44 kDa band | ||

| Uncharacterized protein (Aedes albopictus) | A0AAB0A6X6 | 38,495 |

| Uncharacterized protein (Aedes albopictus) | A0A182G0N4 | 41,526 |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit beta | A0A023ERL5 | 38,453 |

| Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase | A0A023EQM6 | 39,152 |

| Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase [NAD(+)] | A0A182GGV8 | 38,604 |

| Putative actin filament-coating protein tropomyosin | A0A023ETF0 | 43,859 |

|

Aedes albopictus ~26-34 kDa band | ||

| 14-3-3 protein epsilon | A0A023ENU3 | 29,418 |

| Enoyl-CoA hydratase, mitochondrial | A0A023EPZ2 | 31,511 |

| ATP synthase subunit gamma | A0A023ENY5 | 32,711 |

| Uncharacterized protein (Aedes albopictus) | A0A182GDW0 | 29,466 |

| ADP/ATP translocase | A0A023EP24 | 32,904 |

| Proteasome subunit alpha type | A0A023ENX8 | 28,843 |

| Regulator of microtubule dynamics protein 1 | A0A182GHN2 | 26,069 |

| Electron transfer flavoprotein subunit beta | A0A023ENM9 | 27,466 |

| N-acetyltransferase domain-containing protein | A0A023EKP0 | 27,121 |

| Proteasome subunit alpha type | A0A023EL07 | 27,671 |

| Putative 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 | A0A023ENR7 | 27,211 |

| Uncharacterized protein (Aedes albopictus) | A0A182H2F8 | 26,847 |

| Uncharacterized protein (Aedes albopictus) | A0A182G1S0 | 27,190 |

|

Culex quinquefasciatus ~68-70 kDa band | ||

| H(+)-transporting two-sector ATPase | A0A8D8DSN3 | 68,188 |

| Transmembrane protease serine 9 | A0A8D8JS99 | 70,089 |

| Heat shock protein 70 B2 | B0X501 | 69,919 |

|

Culex quinquefasciatus ~30-36 kDa band | ||

| Regucalcin | A0A8D8BZB5 | 33,670 |

| Long form salivary protein D7L2 | B0X6Z1 | 36,051 |

| Tropomyosin-2 | A0A8D8A960 | 35,025 |

| Probable elongation factor 1-beta | A0A8D8KQV6 | 31,741 |

| Enoyl-CoA hydratase ECHA12 | B0W6D4 | 33,912 |

| Malate dehydrogenase | A0A1Q3FI32 | 35,186 |

| ADP/ATP translocase | B0WFA5 | 32,972 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).