Submitted:

23 April 2025

Posted:

24 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Consent for publication

Abbreviations

| BGS | Biogent sentinel trap |

| GAT | Gravid Aedes trap |

| DENV | Dengue virus |

| DHF | Dengue haemorrhagic fever |

| DSS | Dengue shock syndrome |

| ITN | Insecticide treated net |

| IRS | Indoor residual spray |

| DF | Dengue fever |

| YF | Yellow fever |

| CHIK | Chikungunya |

| ZIK | Zika |

| IHR | International health regulations |

| WHO | World health organisation |

| IRR | Incidence rate ratio |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| ELISA | Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction |

| MIR | Mosquito infection rate |

References

- Guzman, A.; Istúriz, R.E. Update on the global spread of dengue. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2010, 36, S40–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady OJ, Gething PW, Bhatt S, Messina JP, Brownstein JS, Hoen AG, et al. Refining the global spatial limits of dengue virus transmission by evidence-based consensus. PlosNegl Trop Dis. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Control ECfDPa. Dengue cases January-December 2023. 2023.

- World Health Organization. Dengue - Global situation. Geneva, Switzerland. 2024.

- Control ECfDPa. Dengue worldwide overview. 2024.

- Who. Dengue and severe dengue. World Health Organisation, Geneva, Switzerland. 2024.

- Bhatt, S.; Gething, P.W.; Brady, O.J.; Messina, J.P.; Farlow, A.W.; Moyes, C.L.; et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature. 2013, 496, 504–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waggoner, J.J.; Gresh, L.; Vargas, M.J.; Ballesteros, G.; Tellez, Y.; Soda, K.J.; et al. Viremia and clinical presentation in Nicaraguan patients infected with Zika virus, chikungunya virus, and dengue virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2016, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Dengue - Global situation. Geneva, Switzerland. 2023.

- World Health Organization. Dengue and severe dengue. Geneva, Switzerland. 2022.

- Boillat-Blanco, N.; Klaassen, B.; Mbarack, Z.; Samaka, J.; Mlaganile, T.; Masimba, J.; Franco Narvaez, L.; Mamin, A.; Genton, B.; Kaiser, L. Dengue fever in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: clinical features and outcome in populations of black and non-black racial category. BMC Infect Dis. 2018, 18, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, M.G.; Harris, E. Dengue. Lancet 2015, 385, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, J.P.; Brady, O.J.; Golding, N.; Kraemer, M.U.; Wint, G.; Ray, S.E.; Pigott, D.M.; Shearer, F.M.; Johnson, K.; Earl, L. The current and future global distribution and population at risk of dengue. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 1508–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, S.N. 17 Taxonomy and Evolutionary Relationships of Flaviviruses. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever 2014, 322. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman, M.G.; Halstead, S.B.; Artsob, H.; Buchy, P.; Farrar, J.; Gubler, D.J.; Hunsperger, E.; Kroeger, A.; Margolis, H.S.; Martínez, E. Dengue: a continuing global threat. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, S7–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harapan, H.; Michie, A.; Sasmono, R.T.; Imrie, A. Dengue: a minireview. Viruses 2020, 12, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najri, N.; Mazlan, Z.; Jaimin, J.; Mohammad, R.; Yusuf, N.M.; Kumar, V.S.; Hoque, M. Genotypes of the dengue virus in patients with dengue infection from Sabah, Malaysia. Journal of Phys. Conference Series; 2019.

- Holmes, E.C.; Twiddy, S.S. The origin, emergence and evolutionary genetics of dengue virus. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2003, 3, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasmono, R.T.; Wahid, I.; Trimarsanto, H.; Yohan, B.; Wahyuni, S.; Hertanto, M.; Yusuf, I.; Mubin, H.; Ganda, I.J.; Latief, R. Genomic analysis and growth characteristic of dengue viruses from Makassar, Indonesia. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015, 32, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodenhuis-Zybert, I.A.; Wilschut, J.; Smit, J.M. Dengue virus life cycle: viral and host factors modulating infectivity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010, 67, 2773–2786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzman, M.G.; Alvarez, M.; Halstead, S.B. Secondary infection as a risk factor for dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome: an historical perspective and role of antibody-dependent enhancement of infection. Arch. Virol. 2013, 158, 1445–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, M.G.; Gubler, D.J.; Izquierdo, A.; Martinez, E.; Halstead, S.B. Dengue infection. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2016, 2, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, D.W.; Green, S.; Kalayanarooj, S.; Innis, B.L.; Nimmannitya, S.; Suntayakorn, S.; Endy, T.P.; Raengsakulrach, B.; Rothman, A.L.; Ennis, F.A. Dengue viremia titer, antibody response pattern, and virus serotype correlate with disease severity. J. Infect. Dis. 2000, 181, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moi, M.L.; Takasaki, T.; Omatsu, T.; Nakamura, S.; Katakai, Y.; Ami, Y.; Suzaki, Y.; Saijo, M.; Akari, H.; Kurane, I. Demonstration of marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) as a non-human primate model for secondary dengue virus infection: high levels of viraemia and serotype cross-reactive antibody responses consistent with secondary infection of humans. J. Gen. Virol. 2014, 95, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarasinghe, A.; Kuritsky, J.N.; Letson, G.W.; Margolis, H.S. Dengue virus infection in Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2011, 17, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang RC, editor Dengue in Africa. Report of the scientific working group meeting on dengue Geneva: WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases. 2007.

- Chipwaza, B.; Mugasa, J.P.; Selemani, M.; Amuri, M.; Mosha, F.; Ngatunga, S.D.; Gwakisa, P.S. Dengue and Chikungunya fever among viral diseases in outpatient febrile children in Kilosa district hospital, Tanzania. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2014, 8, e3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parreira, R.; Centeno-Lima, S.; Lopes, A.; Portugal-Calisto, D.; Constantino, A.; Nina, J. Dengue virus serotype 4 and chikungunya virus coinfection in a traveller returning from Luanda, Angola, January 2014. Eurosurveillance 2014, 19, 20730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautret, P.; Simon, F.; Askling, H.H.; Bouchaud, O.; Leparc-Goffart, I.; Ninove, L.; Parola, P. Dengue type 3 virus infections in European travellers returning from the Comoros and Zanzibar, February-April 2010. Eurosurveillance 2010, 15, 19541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubler, D.J.; Nalim, S.; Tan, R.; Saipan, H. Variation in susceptibility to oral infection with dengue viruses among geographic strains of Aedes aegypti. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1979, 28, 1045–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, L.; Roseboom, L.E.; Gubler, D.J.; Lien, J.C.; Chaniotis, B.N. Comparative susceptibility of mosquito species and strains to oral and parenteral infection with dengue and Japanese encephalitis viruses. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1985, 34, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, P.M.; Rico-Hesse, R. Efficiency of dengue serotype 2 virus strains to infect and disseminate in Aedes aegypti. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2003, 68, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leta, S.; Beyene, T.J.; De Clercq, E.M.; Amenu, K.; Kraemer, M.U.; Revie, C.W. Global risk mapping for major diseases transmitted by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 67, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, O.J.; Hay, S.I. The Global Expansion of Dengue: How Aedes aegypti Mosquitoes Enabled the First Pandemic Arbovirus. Annu Rev Entomol 2020, 65, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, S.; Luedtke, A.; Langevin, E.; Zhu, M.; Bonaparte, M.; Machabert, T.; Savarino, S.; Zambrano, B.; Moureau, A.; Khromava, A. Effect of dengue serostatus on dengue vaccine safety and efficacy. New Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponlawat, A.; Harrington, L.C. Blood feeding patterns of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus in Thailand. J. Med. Entomol. 2005, 42, 844–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.G.; Washington, M.; Guynup, T.; Tarrand, C.; Dewey, E.M.; Fredregill, C.; Duguma, D.; Pitts, R.J. Feeding habits of vector mosquitoes in Harris County, TX, 2018. J. Med. Entomol. 2020, 57, 1920–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, D.; Chen, R.; Diagne, C.T.; Ba, Y.; Dia, I.; Sall, A.A.; Weaver, S.C.; Diallo, M. Bloodfeeding patterns of sylvatic arbovirus vectors in southeastern Senegal. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2013, 107, 200–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivan, A.; Shriram, A.; Sunish, I.; Vidhya, P. Host-feeding pattern of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in heterogeneous landscapes of South Andaman, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. Parasitol. Res. 2015, 114, 3539–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olson, M.F.; Ndeffo-Mbah, M.L.; Juarez, J.G.; Garcia-Luna, S.; Martin, E.; Borucki, M.K.; Frank, M.; Estrada-Franco, J.G.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.A.; Fernández-Santos, N.A. High rate of non-human feeding by Aedes aegypti reduces Zika virus transmission in South Texas. Viruses 2020, 12, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sene, N.M.; Diouf, B.; Gaye, A.; Gueye, A.; Seck, F.; Diagne, C.T.; Dia, I.; Diallo, D.; Diallo, M. Blood feeding patterns of Aedes aegypti populations in Senegal. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2022, 106, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruszynski, C.A.; Stenn, T.; Acevedo, C.; Leal, A.L.; Burkett-Cadena, N.D. Human blood feeding by Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in the Florida Keys and a review of the literature. J. Med. Entomol. 2020, 57, 1640–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.H.; Van Wyk, H.; Morrison, A.C.; Coloma, J.; Lee, G.O.; Cevallos, V.; Ponce, P.; Eisenberg, J.N. The biting rate of Aedes aegypti and its variability: A systematic review (1970–2022). PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0010831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, E.; Medeiros, M.C.; Carbajal, E.; Valdez, E.; Juarez, J.G.; Garcia-Luna, S.; Salazar, A.; Qualls, W.A.; Hinojosa, S.; Borucki, M.K. Surveillance of Aedes aegypti indoors and outdoors using Autocidal Gravid Ovitraps in South Texas during local transmission of Zika virus, 2016 to 2018. Acta Trop. 2019, 192, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalpadado, R.; Amarasinghe, D.; Gunathilaka, N.; Ariyarathna, N. Bionomic aspects of dengue vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus at domestic settings in urban, suburban and rural areas in Gampaha District, Western Province of Sri Lanka. Parasites Vectors 2022, 15, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadee, D.D.; Martinez, R. Landing periodicity of Aedes aegypti with implications for dengue transmission in Trinidad, West Indies. J. Soc. Vector Ecol. 2000, 25, 158–163. [Google Scholar]

- Vairo, F.; Nicastri, E.; Meschi, S.; Schepisi, M.S.; Paglia, M.G.; Bevilacqua, N.; Mangi, S.; Sciarrone, M.R.; Chiappini, R.; Mohamed, J. Seroprevalence of dengue infection: a cross-sectional survey in mainland Tanzania and on Pemba Island, Zanzibar. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 16, e44–e46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vairo, F.; Nicastri, E.; Yussuf, S.M.; Cannas, A.; Meschi, S.; Mahmoud, M.A.; Mohamed, A.H.; Maiko, P.M.; De Nardo, P.; Bevilacqua, N. IgG against dengue virus in healthy blood donors, Zanzibar, Tanzania. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2014, 20, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moi, M.L.; Takasaki, T.; Kotaki, A.; Tajima, S.; Lim, C.-K.; Sakamoto, M.; Iwagoe, H.; Kobayashi, K.; Kurane, I. Importation of dengue virus type 3 to Japan from Tanzania and Côte d’Ivoire. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010, 16, 1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chipwaza B, Sumaye RD, Weisser M, Gingo W, Yeo NK-W, Amrun SN, et al., editors. Occurrence of 4 dengue virus serotypes and chikungunya virus in Kilombero Valley, Tanzania, during the dengue outbreak in 2018. Open forum infectious diseases; 2021: Oxford Univ Press US.

- Hertz, J.T.; Munishi, O.M.; Ooi, E.E.; Howe, S.; Lim, W.Y.; Chow, A.; Morrissey, A.B.; Bartlett, J.A.; Onyango, J.J.; Maro, V.P. Chikungunya and dengue fever among hospitalized febrile patients in northern Tanzania. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012, 86, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Dengue outbreak in the United Republic of Tanzania. 2014.

- Mboera, L.E.; Mweya, C.N.; Rumisha, S.F.; Tungu, P.K.; Stanley, G.; Makange, M.R.; Misinzo, G.; De Nardo, P.; Vairo, F.; Oriyo, N.M. The risk of dengue virus transmission in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania during an epidemic period of 2014. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, M.E.; Msafiri, F.; Affara, M.; Gehre, F.; Moremi, N.; Mghamba, J.; Misinzo, G.; Thye, T.; Gatei, W.; Whistler, T. Molecular Characterization and Phylogenetic Analysis of Dengue Fever Viruses in Three Outbreaks in Tanzania Between 2017 and 2019. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, K.; Morita, R.; Egawa, K.; Hirai, Y.; Kaida, A.; Shirano, M.; Kubo, H.; Goto, T.; Yamamoto, S.P. Dengue virus type 1 infection in traveler returning from Tanzania to Japan, 2019. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwanyika, G.O.; et al. Co-circulation of Dengue Virus Serotypes 1 and 3 during the 2019 epidemic in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. PloS Negl Trop Dis. 2019.

- Mwanyika, G.O.; Sindato, C.; Rugarabamu, S.; Rumisha, S.F.; Karimuribo, E.D.; Misinzo, G.; Rweyemamu, M.M.; Hamid, M.M.A.; Haider, N.; Vairo, F. Seroprevalence and associated risk factors of chikungunya, dengue, and Zika in eight districts in Tanzania. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 111, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SACIDS. Dengue Outbreaks in Tanzania: Recent Trends and Importance of Research Data in Disease Surveillance. Morogoro, Tanzania: Southern African Centre for Infectious Disease Surveillance; 2019.

- Vairo, F.; Mboera, L.E.; De Nardo, P.; Oriyo, N.M.; Meschi, S.; Rumisha, S.F.; Colavita, F.; Mhina, A.; Carletti, F.; Mwakapeje, E. Clinical, virologic, and epidemiologic characteristics of dengue outbreak, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, 2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2016, 22, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shauri, H.S.; Ngadaya, E.; Senkoro, M.; Buza, J.J.; Mfinanga, S. Seroprevalence of Dengue and Chikungunya antibodies among blood donors in Dar es Salaam and Zanzibar, Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajeguka, D.C.; Kaaya, R.D.; Mwakalinga, S.; Ndossi, R.; Ndaro, A.; Chilongola, J.O.; Mosha, F.W.; Schiøler, K.L.; Kavishe, R.A.; Alifrangis, M. Prevalence of dengue and chikungunya virus infections in north-eastern Tanzania: a cross sectional study among participants presenting with malaria-like symptoms. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

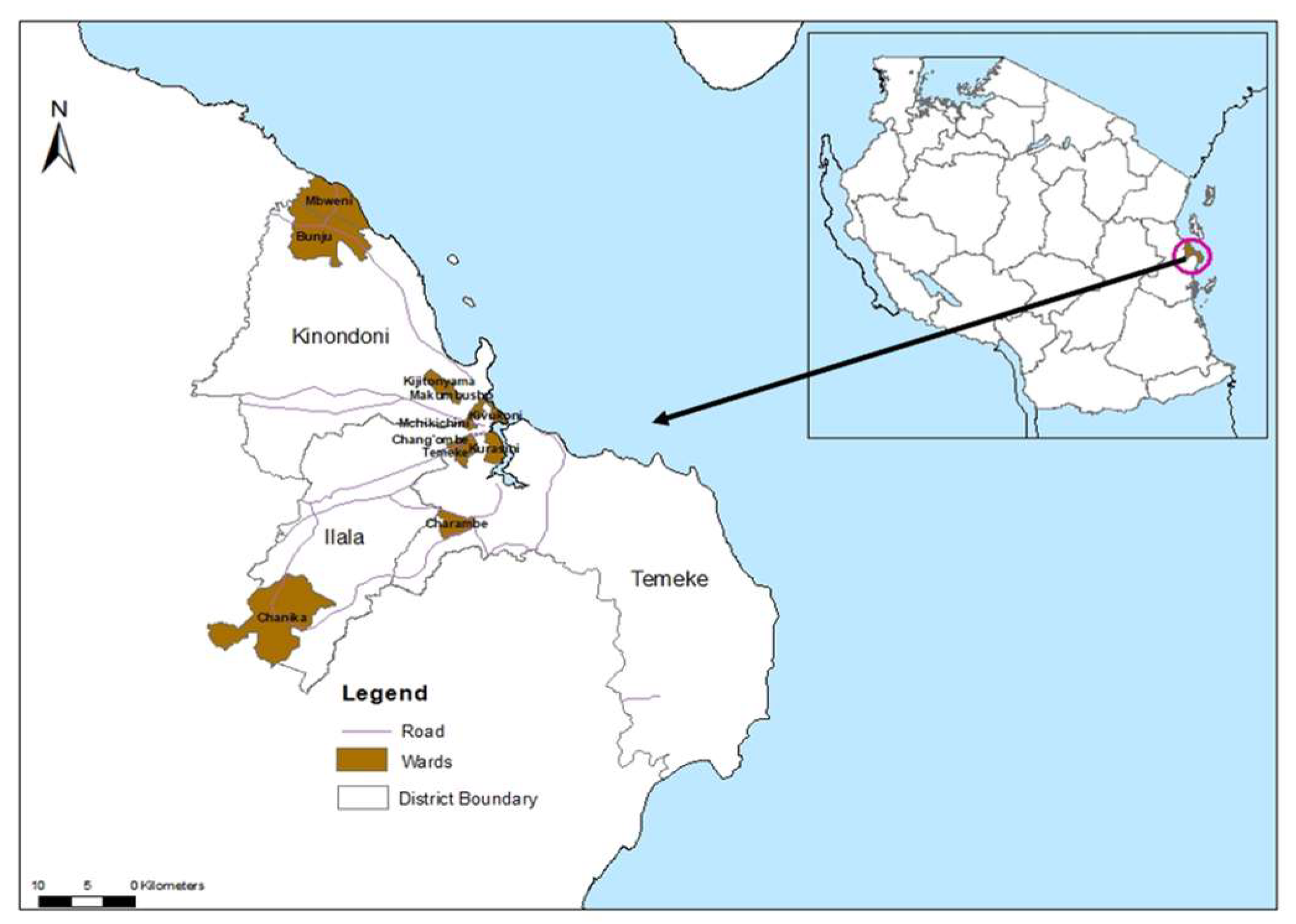

- National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Office of Chief Government Statistician President’s Office, F., Economy and Development Planning. Population and Housing Census. Administrative units Population Distribution and Age and Sex Distribution Report Tanzania- volume1a. 2022.

- Msellemu, D.; Gavana, T.; Ngonyani, H.; Mlacha, Y.P.; Chaki, P.; Moore, S.J. Knowledge, attitudes and bite prevention practices and estimation of productivity of vector breeding sites using a Habitat Suitability Score (HSS) among households with confirmed dengue in the 2014 outbreak in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0007278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machange, J.J.; Maasayi, M.S.; Mundi, J.; Moore, J.; Muganga, J.B.; Odufuwa, O.G.; Moore, S.J.; Tenywa, F.C. Comparison of the Trapping Efficacy of Locally Modified Gravid Aedes Trap and Autocidal Gravid Ovitrap for the Monitoring and Surveillance of Aedes aegypti Mosquitoes in Tanzania. Insects 2024, 15, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkerson, R.C.; Linton, Y.-M.; Strickman, D. Mosquitoes of the World; Johns Hopkins University Press: 2021.

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L. The MIQE Guidelines: M inimum I nformation for Publication of Q uantitative Real-Time PCR E xperiments. Oxford University Press: 2009.

- Pérez-Castro, R.; Castellanos, J.E.; Olano, V.A.; Matiz, M.I.; Jaramillo, J.F.; Vargas, S.L.; Sarmiento, D.M.; Stenström, T.A.; Overgaard, H.J. Detection of all four dengue serotypes in Aedes aegypti female mosquitoes collected in a rural area in Colombia. Mem. Do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2016, 111, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balingit, J.C.; Carvajal, T.M.; Saito-Obata, M.; Gamboa, M.; Nicolasora, A.D.; Sy, A.K.; Oshitani, H.; Watanabe, K. Surveillance of dengue virus in individual Aedes aegypti mosquitoes collected concurrently with suspected human cases in Tarlac City, Philippines. Parasites Vectors 2020, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beier, J.C.; Perkins, P.V.; Wirtz, R.A.; Koros, J.; Diggs, D.; Gargan, T.P.; Koech, D.K. Bloodmeal identification by direct enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), tested on Anopheles (Diptera: Culicidae) in Kenya. J. Med. Entomol. 1988, 25, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyasi, P.; Bright Yakass, M.; Quaye, O. Analysis of dengue fever disease in West Africa. Exp. Biol. Med. 2023, 248, 1850–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Dengue and Severe Dengue Fact Sheet. Geneva, Switzerland. 2019.

- Masika, M.M.; Korhonen, E.M.; Smura, T.; Uusitalo, R.; Vapalahti, K.; Mwaengo, D.; Jääskeläinen, A.J.; Anzala, O.; Vapalahti, O.; Huhtamo, E. Detection of dengue virus type 2 of Indian origin in acute febrile patients in rural Kenya. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langat, S.K.; Eyase, F.L.; Berry, I.M.; Nyunja, A.; Bulimo, W.; Owaka, S.; Ofula, V.; Limbaso, S.; Lutomiah, J.; Jarman, R. Origin and evolution of dengue virus type 2 causing outbreaks in Kenya: Evidence of circulation of two cosmopolitan genotype lineages. Virus Evol. 2020, 6, veaa026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bank, A.D. Urbanization in Africa. 2012.

- World Health Organization. Urban yellow fever risk management: preparedness and response: Handbook for national operational planning. Geneva, Switzerland. 2023.

- Mwanyika, G.; Mboera, L.E.; Rugarabamu, S.; Lutwama, J.; Sindato, C.; Paweska, J.T.; Misinzo, G. Co-circulation of Dengue Virus Serotypes 1 and 3 during the 2019 epidemic in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. bioRxiv 2019, 763003. [Google Scholar]

- Chilongola, J.O.; Mwakapuja, R.S.; Horumpende, P.G.; Vianney, J.-M.; Shabhay, A.; Mkumbaye, S.I.; Semvua, H.S.; Mmbaga, B.T. Concurrent Infection With Dengue and Chikungunya Viruses in Humans and Mosquitoes: A Field Survey in Lower Moshi, Tanzania. East Afr. Sci. 2022, 4, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, N.K.; Mumo, E.; Morlighem, C.; Macharia, P.M.; Snow, R.W.; Linard, C. Mosquito-borne diseases in urban East African Community region: a scoping review of urban typology research and mosquito genera overlap, 2000-2024. Front. Trop. Dis. 2024, 5, 1499520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojica, J.; Arévalo, V.; Juarez, J.G.; Galarza, X.; Gonzalez, K.; Carrazco, A.; Suazo, H.; Harris, E.; Coloma, J.; Ponce, P. A numbers game: mosquito-based arbovirus surveillance in two distinct geographic regions of Latin America. J. Med. Entomol. 2025, 62, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maneerattanasak, S.; Ngamprasertchai, T.; Tun, Y.M.; Ruenroengbun, N.; Auewarakul, P.; Boonnak, K. Prevalence of dengue, Zika, and chikungunya virus infections among mosquitoes in Asia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2024, 107226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapua, S.A.; Hape, E.E.; Kihonda, J.; Bwanary, H.; Kifungo, K.; Kilalangongono, M.; Kaindoa, E.W.; Ngowo, H.S.; Okumu, F.O. Persistently high proportions of plasmodium-infected Anopheles funestus mosquitoes in two villages in the Kilombero valley, South-Eastern Tanzania. Parasite Epidemiol. Control 2022, 18, e00264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lwetoijera, D.W.; Harris, C.; Kiware, S.S.; Dongus, S.; Devine, G.J.; McCall, P.J.; Majambere, S. Increasing role of Anopheles funestus and Anopheles arabiensis in malaria transmission in the Kilombero Valley, Tanzania. Malar. J. 2014, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, G. Epidemiologic models in studies of vetor-borne diseases: The re dyer lecture. Public Health Rep. 1961, 76, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouf, B.; Sene, N.M.; Ndiaye, E.H.; Gaye, A.; Ngom, E.H.M.; Gueye, A.; Seck, F.; Diagne, C.T.; Dia, I.; Diallo, M. Resting behavior of blood-fed females and host feeding preferences of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) morphological forms in Senegal. J. Med. Entomol. 2021, 58, 2467–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badolo, A.; Sombié, A.; Yaméogo, F.; Wangrawa, D.W.; Sanon, A.; Pignatelli, P.M.; Sanon, A.; Viana, M.; Kanuka, H.; Weetman, D. First comprehensive analysis of Aedes aegypti bionomics during an arbovirus outbreak in west Africa: Dengue in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 2016–2017. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivan, A.; Shriram, A.N.; Sunish, I.P.; Vidhya, P.T. Host-feeding pattern of Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae) in heterogeneous landscapes of South Andaman, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India. Parasitol Res 2015, 114, 3539–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, C.C.; Webb, C.E.; Graham, G.C.; Craig, S.B.; Zborowski, P.; Ritchie, S.A.; Russell, R.C.; van den Hurk, A.F. Blood sources of mosquitoes collected from urban and peri-urban environments in eastern Australia with species-specific molecular analysis of avian blood meals. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2009, 81, 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melgarejo-Colmenares, K.; Cardo, M.V.; Vezzani, D. Blood feeding habits of mosquitoes: hardly a bite in South America. Parasitol Res 2022, 121, 1829–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruszynski, C.A.; Stenn, T.; Acevedo, C.; Leal, A.L.; Burkett-Cadena, N.D. Human Blood Feeding by Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in the Florida Keys and a Review of the Literature. J Med Entomol 2020, 57, 1640–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell JR, Tabachnick WJ. History of domestication and spread of Aedes aegypti-a review. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2013;108(suppl 1):11-7.

- Diallo, M.; Sall, A.A.; Moncayo, A.C.; Ba, Y.; Fernandez, Z.; Ortiz, D.; Coffey, L.L.; Mathiot, C.; Tesh, R.B.; Weaver, S.C. Potential role of sylvatic and domestic African mosquito species in dengue emergence. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2005, 73, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, M.J.; Murdock, C.C.; Kelly, P.J. Sylvatic cycles of arboviruses in non-human primates. Parasit Vectors 2019, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepkorir, E.; Lutomiah, J.; Mutisya, J.; Mulwa, F.; Limbaso, K.; Orindi, B.; Ng'ang'a, Z.; Sang, R. Vector competence of Aedes aegypti populations from Kilifi and Nairobi for dengue 2 virus and the influence of temperature. Parasit Vectors 2014, 7, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouck, H.K. Host preferences of various strains of Aedes aegypti and A. simpsoni as determined by an olfactometer. Bull World Health Organ 1972, 47, 680–683. [Google Scholar]

- Monath, T.P.; Vasconcelos, P.F. Yellow fever. J. Clin. Virol. 2015, 64, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteva, L.; Vargas, C. Coexistence of different serotypes of dengue virus. J. Math. Biol. 2003, 46, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Velasco-Hernández, J.X. Competitive exclusion in a vector-host model for the dengue fever. J. Math. Biol. 1997, 35, 523–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouédraogo, W.M.; Zanré, N.; Sombié, A.; Yameogo, F.; Gnémé, A.; Sanon, A.; Costantini, C.; Kanuka, H.; Viana, M.; Weetman, D.; et al. Blood-Feeding Patterns and Resting Behavior of Aedes aegypti from Three Health Districts of Ouagadougou City, Burkina Faso. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2024, 111, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badolo, A.; Sombié, A.; Yaméogo, F.; Wangrawa, D.W.; Sanon, A.; Pignatelli, P.M.; Sanon, A.; Viana, M.; Kanuka, H.; Weetman, D.; McCall, P.J. First comprehensive analysis of Aedes aegypti bionomics during an arbovirus outbreak in west Africa: Dengue in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, 2016-2017. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2022, 16, e0010059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Captain-Esoah, M.; Kweku Baidoo, P.; Frempong, K.K.; Adabie-Gomez, D.; Chabi, J.; Obuobi, D.; Kwame Amlalo, G.; Balungnaa Veriegh, F.; Donkor, M.; Asoala, V.; et al. Biting Behavior and Molecular Identification of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) Subspecies in Some Selected Recent Yellow Fever Outbreak Communities in Northern Ghana. J Med Entomol 2020, 57, 1239–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montenegro-Quiñonez, C.A.; Louis, V.R.; Horstick, O.; Velayudhan, R.; Dambach, P.; Runge-Ranzinger, S. Interventions against Aedes/dengue at the household level: a systematic review and meta-analysis. eBioMedicine 2023, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utarini, A.; Indriani, C.; Ahmad, R.A.; Tantowijoyo, W.; Arguni, E.; Ansari, M.R.; Supriyati, E.; Wardana, D.S.; Meitika, Y.; Ernesia, I.; et al. Efficacy of Wolbachia-Infected Mosquito Deployments for the Control of Dengue. N Engl J Med 2021, 384, 2177–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, S.B.; Tchouassi, D.P.; Turell, M.J.; Bastos, A.D.S.; Sang, R. Entomological assessment of dengue virus transmission risk in three urban areas of Kenya. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019, 13, e0007686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| DENV serotype detected | Primer and probes | Nucleotide sequence (5’ → 3’) | Fluorophore and 3’ Quencher |

|---|---|---|---|

| DENV-1 | DEN-1 forward | CAAAAGGAAGTCGTGCAATA | FAM |

| DEN-1 reverse | CTGAGTGAATTCTCTCTACTGAACC | ||

| DEN-1 probe | CATGTGGTTGGGAGCACGC | ||

| DENV-2 | DEN-2 forward | CAGGCTATGGCACTGTCAC | HEX |

| DEN-2 reverse | CCATTTGCAGCAACACCATC | ||

| DEN-2 probe | CTCTCCGAGAACGGGCCTCGACTTCAA | ||

| DENV-3 | DEN-3 forward | GGACTGGACACACGCACTCA | CY5 |

| DEN-3 reverse | CATGTCTCTACCTTCTCGACTTGTCT | ||

| DEN-3 probe | ACCTGGATGTCGGCTGAAGGAGCTTG | ||

| DENV-4 | DEN-4 forward | TTGTCCTAATGATGCTGGTCG | CY5.5 CY5/BHQ3 |

| DEN-4 reverse | TCCACCTGAGACTCCTTCCA | ||

| DEN-4 probe | TTCCTACTCCTACGCATCGCATTCCG |

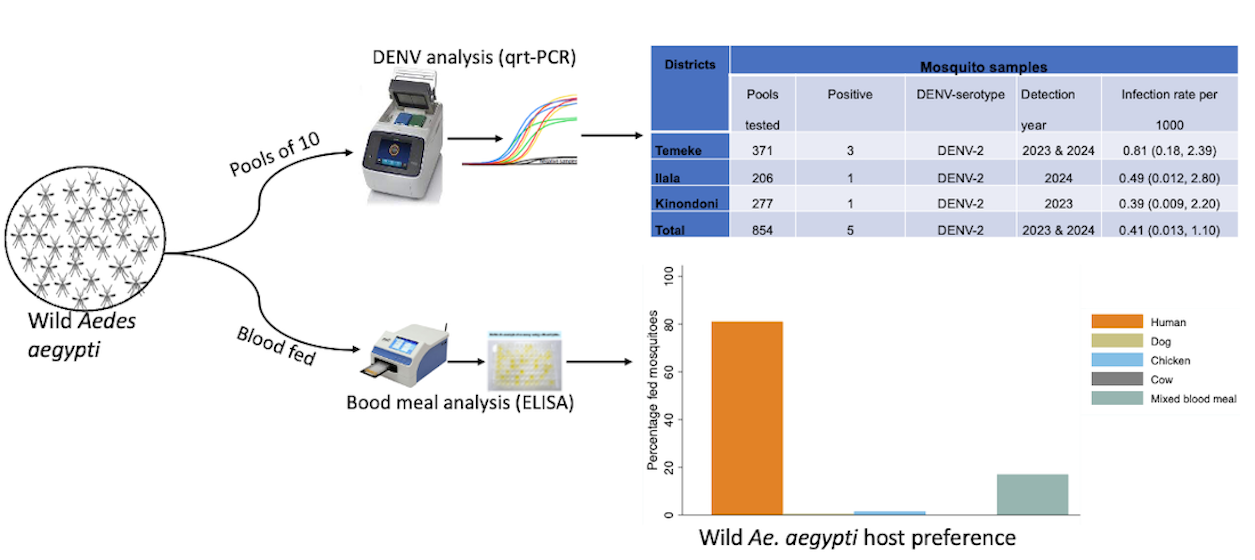

| Districts | Mosquito samples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pools tested | Positive | DENV-serotype | Detection year | Infection rate per 1000 | |

| Temeke | 371 | 3 | DENV-2 | 2023 & 2024 | 0.81 (0.18, 2.39) |

| Ilala | 206 | 1 | DENV-2 | 2024 | 0.49 (0.012, 2.80) |

| Kinondoni | 277 | 1 | DENV-2 | 2023 | 0.39 (0.009, 2.20) |

| Total | 854 | 5 | DENV-2 | 2023 & 2024 | 0.41 (0.013, 1.10) |

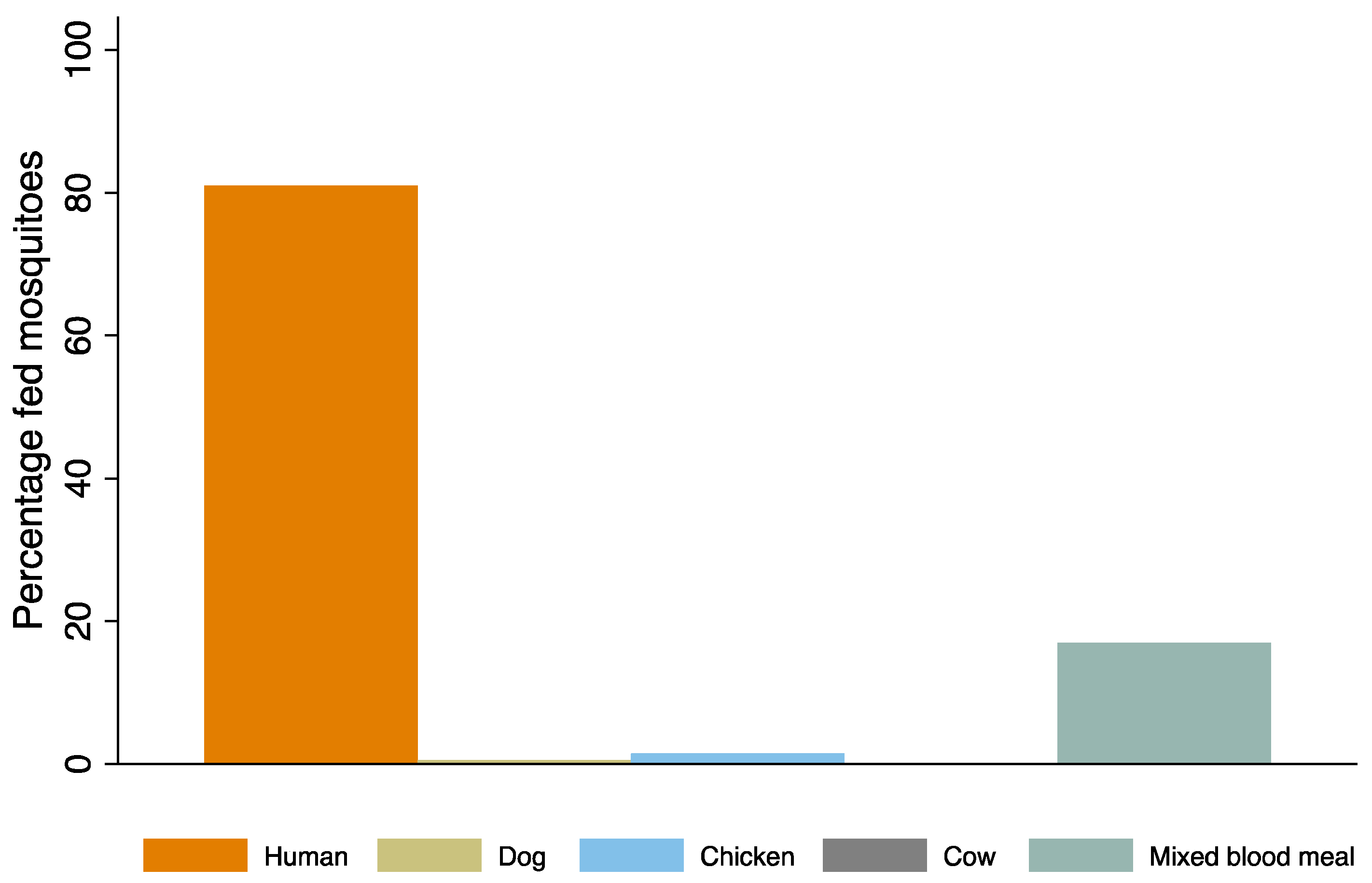

| Traps | BGS trap | Prokopack aspirator | GAT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood fed Aedes aegypti | 57 | 142 | 6 |

| Percentage blood fed | 27.8 | 69.3 | 2.9 |

| N | n(%) | IRR (95%CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collection location | ||||

| Indoors | 54 | 76 (21.5) | 1 | - |

| Outdoors | 54 | 278 (78.5) | 4.33 (2.38-7.89) | <0.001 |

| Districts | ||||

| Ilala | 18 | 42 (11.9) | 1 | - |

| Kinondoni | 18 | 135 (38.1) | 4.24 (1.98-9.06) | <0.001 |

| Temeke | 18 | 177 (50.0) | 5.03 (2.39-10.58) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).