Submitted:

11 July 2025

Posted:

14 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Epidemiology of Potentially Protective Effects of Smoking and Exercise

Evidence for an Association

Limitations

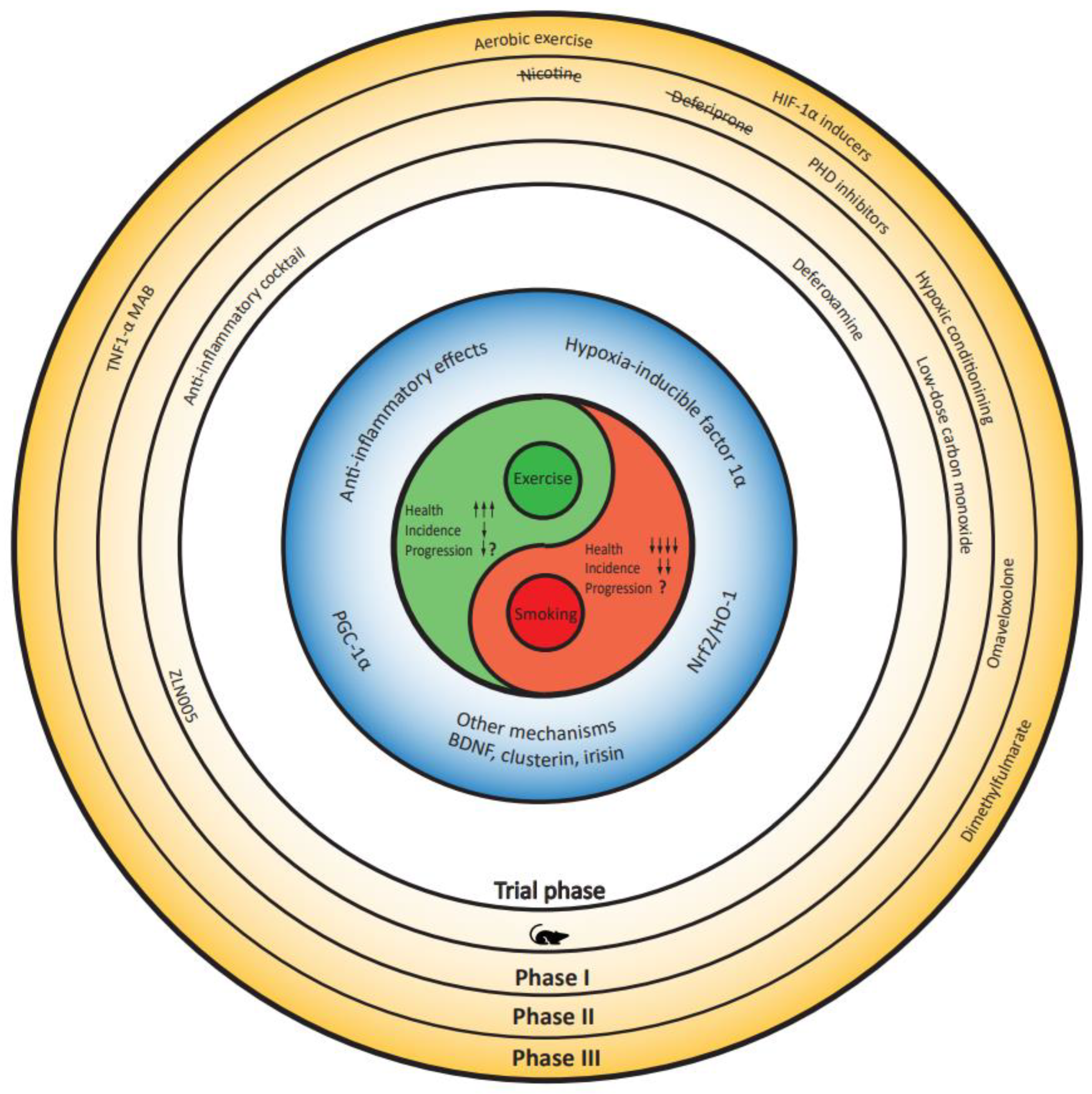

Protective Mechanisms in Smoking and Exercise?

Overlapping Mechanisms

- Hypoxia response pathway (HIF-1)

- Nrf2/HO-1

- PGC-1α

- Anti-inflammatory effects

- Other mechanisms

Translation of Evidence into Therapeutic Opportunities

Nicotine

Low-Dose Carbon Monoxide

Hypoxic Conditioning

Small-Molecule Approaches

Conclusion

References

- Fang, X., et al. Association of Levels of Physical Activity With Risk of Parkinson Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 1, e182421 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Breckenridge, C.B., Berry, C., Chang, E.T., Sielken, R.L., Jr. & Mandel, J.S. Association between Parkinson’s Disease and Cigarette Smoking, Rural Living, Well-Water Consumption, Farming and Pesticide Use: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 11, e0151841 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Nefzger, M.D., Quadfasel, F.A. & Karl, V.C. A retrospective study of smoking in Parkinson’s disease. Am J Epidemiol 88, 149-158 (1968). [CrossRef]

- Kessler, II & Diamond, E.L. Epidemiologic studies of Parkinson’s disease. I. Smoking and Parkinson’s disease: a survey and explanatory hypothesis. Am J Epidemiol 94, 16-25 (1971). [CrossRef]

- Baumann, R.J., Jameson, H.D., McKean, H.E., Haack, D.G. & Weisberg, L.M. Cigarette smoking and Parkinson disease: 1. Comparison of cases with matched neighbors. Neurology 30, 839-843 (1980). [CrossRef]

- Marttila, R.J. & Rinne, U.K. Smoking and Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand 62, 322-325 (1980). [CrossRef]

- Godwin-Austen, R.B., Lee, P.N., Marmot, M.G. & Stern, G.M. Smoking and Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 45, 577-581 (1982). [CrossRef]

- Janssen Daalen, J.M., Schootemeijer, S., Richard, E., Darweesh, S.K.L. & Bloem, B.R. Lifestyle Interventions for the Prevention of Parkinson Disease: A Recipe for Action. Neurology 99, 42-51 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Organization, W.H. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2023: protect people from tobacco smoke. (2023).

- Tanner, C.M., et al. Smoking and Parkinson’s disease in twins. Neurology 58, 581-588 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Gallo, V., et al. Exploring causality of the association between smoking and Parkinson’s disease. Int J Epidemiol 48, 912-925 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Mappin-Kasirer, B., et al. Tobacco smoking and the risk of Parkinson disease: A 65-year follow-up of 30,000 male British doctors. Neurology 94, e2132-e2138 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Domenighetti, C., et al. Mendelian Randomisation Study of Smoking, Alcohol, and Coffee Drinking in Relation to Parkinson’s Disease. J Parkinsons Dis 12, 267-282 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Baleon, C., Ong, J.S., Scherzer, C.R., Renteria, M.E. & Dong, X. Understanding the effect of smoking and drinking behavior on Parkinson’s disease risk: a Mendelian randomization study. Sci Rep 11, 13980 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Ritz, B.R. & Kusters, C.D.J. The Promise of Mendelian Randomization in Parkinson’s Disease: Has the Smoke Cleared Yet for Smoking and Parkinson’s Disease Risk? J Parkinsons Dis 12, 807-812 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.K., et al. Nicotine activates HIF-1alpha and regulates acid extruders through the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor to promote the Warburg effect in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Eur J Pharmacol 950, 175778 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Daijo, H., et al. Cigarette smoke reversibly activates hypoxia-inducible factor 1 in a reactive oxygen species-dependent manner. Sci Rep 6, 34424 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Muller, T. & Hengstermann, A. Nrf2: friend and foe in preventing cigarette smoking-dependent lung disease. Chem Res Toxicol 25, 1805-1824 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Erlich, A.T., Brownlee, D.M., Beyfuss, K. & Hood, D.A. Exercise induces TFEB expression and activity in skeletal muscle in a PGC-1alpha-dependent manner. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 314, C62-C72 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Halling, J.F., et al. PGC-1alpha regulates mitochondrial properties beyond biogenesis with aging and exercise training. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 317, E513-E525 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Lira, V.A., Benton, C.R., Yan, Z. & Bonen, A. PGC-1alpha regulation by exercise training and its influences on muscle function and insulin sensitivity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 299, E145-161 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J., et al. Neuroprotective effect of nicotine on dopaminergic neurons by anti-inflammatory action. Eur J Neurosci 26, 79-89 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Rose, K.N., et al. Neuroprotection of low dose carbon monoxide in Parkinson’s disease models commensurate with the reduced risk of Parkinson’s among smokers. bioRxiv (2024). [CrossRef]

- Oertel, W.H., et al. Transdermal Nicotine Treatment and Progression of Early Parkinson’s Disease. NEJM Evidence 2, EVIDoa2200311 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Janssen Daalen, J.M., et al. Multiple N-of-1 trials to investigate hypoxia therapy in Parkinson’s disease: study rationale and protocol. BMC Neurol 22, 262 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Janssen Daalen, J.M., et al. The Hypoxia Response Pathway: A Potential Intervention Target in Parkinson’s Disease? Mov Disord 39, 273-293 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Nie, J., et al. Independent and Joint Associations of Tea Consumption and Smoking with Parkinson’s Disease Risk in Chinese Adults. J Parkinsons Dis 12, 1693-1702 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Gallo, V., et al. Exploring causality of the association between smoking and Parkinson’s disease. Int J Epidemiol 48, 912-925 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Kim, R., Yoo, D., Jung, Y.J., Han, K. & Lee, J.Y. Smoking Cessation, Weight Change, and Risk of Parkinson’s Disease: Analysis of National Cohort Data. J Clin Neurol 16, 455-460 (2020).

- Sieurin, J., Zhan, Y., Pedersen, N.L. & Wirdefeldt, K. Neuroticism, Smoking, and the Risk of Parkinson’s Disease. J Parkinsons Dis 11, 1325-1334 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., Wang, B., Xiao, Y., Wang, D. & Chen, W. Secondhand smoking and neurological disease: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Rev Environ Health 36, 271-277 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Han, C., Lu, Y., Cheng, H., Wang, C. & Chan, P. The impact of long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and second-hand smoke on the onset of Parkinson disease: a review and meta-analysis. Public Health 179, 100-110 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Gatto, N.M., et al. Passive smoking and Parkinson’s disease in California Teachers. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 45, 44-49 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Gigante, A.F., Martino, T., Iliceto, G. & Defazio, G. Smoking and age-at-onset of both motor and non-motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 45, 94-96 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Gabbert, C., et al. Coffee, smoking and aspirin are associated with age at onset in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol 269, 4195-4203 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Rosas, I., et al. Smoking is associated with age at disease onset in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 97, 79-83 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Gigante, A.F., et al. Smoking in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: preliminary striatal DaT-SPECT findings. Acta Neurol Scand 134, 265-270 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Moccia, M., et al. Non-Motor Correlates of Smoking Habits in de Novo Parkinson’s Disease. J Parkinsons Dis 5, 913-924 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Doiron, M., Dupre, N., Langlois, M., Provencher, P. & Simard, M. Smoking history is associated to cognitive impairment in Parkinson’s disease. Aging Ment Health 21, 322-326 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Neshige, S., Ohshita, T., Neshige, R. & Maruyama, H. Influence of current and previous smoking on current phenotype in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci 427, 117534 (2021). [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, E.J., et al. Smokeless tobacco use and the risk of Parkinson’s disease mortality. Mov Disord 20, 1383-1384 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.Y., et al. Association between smoking and all-cause mortality in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 9, 59 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., et al. Physical activity and risk of Parkinson’s disease in the Swedish National March Cohort. Brain 138, 269-275 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Mak, M.K., Wong-Yu, I.S., Shen, X. & Chung, C.L. Long-term effects of exercise and physical therapy in people with Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol 13, 689-703 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Tsukita, K., Sakamaki-Tsukita, H. & Takahashi, R. Long-term Effect of Regular Physical Activity and Exercise Habits in Patients With Early Parkinson Disease. Neurology 98, e859-e871 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Jin, C., Jiang, Y. & Wu, H. Association between regular physical activity and biomarker changes in early Parkinson’s disease patients. Parkinsonism Relat Disord, 105771 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Schenkman, M., et al. Effect of High-Intensity Treadmill Exercise on Motor Symptoms in Patients With De Novo Parkinson Disease: A Phase 2 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol 75, 219-226 (2018). [CrossRef]

- van der Kolk, N.M., et al. Effectiveness of home-based and remotely supervised aerobic exercise in Parkinson’s disease: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 18, 998-1008 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Johansson, M.E., et al. Aerobic Exercise Alters Brain Function and Structure in Parkinson’s Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Neurol 91, 203-216 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Ben-Shlomo, Y. Smoking and neurogenerative diseases. Lancet 342, 1239 (1993).

- Zhang, L., et al. Beneficial Effects on Brain Micro-Environment by Caloric Restriction in Alleviating Neurodegenerative Diseases and Brain Aging. Front Physiol 12, 715443 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Y.H., et al. Genetic variants in nicotinic receptors and smoking cessation in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 62, 57-61 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Rose, K.N., Schwarzschild, M.A. & Gomperts, S.N. Clearing the Smoke: What Protects Smokers from Parkinson’s Disease? Mov Disord (2024). [CrossRef]

- Yang, F., et al. Moist smokeless tobacco (Snus) use and risk of Parkinson’s disease. Int J Epidemiol 46, 872-880 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., et al. Association between cigarette smoking and Parkinson’s disease: a neuroimaging study. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 15, 17562864221092566 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Ma, C., Liu, Y., Neumann, S. & Gao, X. Nicotine from cigarette smoking and diet and Parkinson disease: a review. Transl Neurodegener 6, 18 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Rose, K.N., et al. Neuroprotection of low dose carbon monoxide in Parkinson’s disease models commensurate with the reduced risk of Parkinson’s among smokers. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 10, 152 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Koskinen, L.O., Collin, O. & Bergh, A. Cigarette smoke and hypoxia induce acute changes in the testicular and cerebral microcirculation. Ups J Med Sci 105, 215-226 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Fricker, M., et al. Chronic cigarette smoke exposure induces systemic hypoxia that drives intestinal dysfunction. JCI Insight 3(2018). [CrossRef]

- Allam, M.F., Campbell, M.J., Hofman, A., Del Castillo, A.S. & Fernández-Crehuet Navajas, R. Smoking and Parkinson’s disease: systematic review of prospective studies. Mov Disord 19, 614-621 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y., et al. Does smoking impact dopamine neuronal loss in de novo Parkinson disease? Ann Neurol 82, 850-854 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Allam, M.F., Del Castillo, A.S. & Navajas, R.F. Parkinson’s disease, smoking and family history: meta-analysis. Eur J Neurol 10, 59-62 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Scheltens, P., et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 397, 1577-1590 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Ott, A., et al. Smoking and risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in a population-based cohort study: the Rotterdam Study. Lancet 351, 1840-1843 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Bloem, B.R., Okun, M.S. & Klein, C. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 397, 2284-2303 (2021).

- Darweesh, S.K.L., et al. Inhibition of Neuroinflammation May Mediate the Disease-Modifying Effects of Exercise: Implications for Parkinson’s Disease. J Parkinsons Dis 12, 1419-1422 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W., Ko, J., Ju, C. & Eltzschig, H.K. Hypoxia signaling in human diseases and therapeutic targets. Exp Mol Med 51, 1-13 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Smeyne, M., Sladen, P., Jiao, Y., Dragatsis, I. & Smeyne, R.J. HIF1alpha is necessary for exercise-induced neuroprotection while HIF2alpha is needed for dopaminergic neuron survival in the substantia nigra pars compacta. Neuroscience 295, 23-38 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Nava, R.C., et al. Repeated sprint exercise in hypoxia stimulates HIF-1-dependent gene expression in skeletal muscle. Eur J Appl Physiol 122, 1097-1107 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, M.E. & Rundqvist, H. Skeletal muscle hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and exercise. Exp Physiol 101, 28-32 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Pallardo-Fernández, I., Iglesias, V., Rodríguez-Rivera, C., González-Martín, C. & Alguacil, L.F. Salivary clusterin as a biomarker of tobacco consumption in nicotine addicts undergoing smoking cessation therapy. Journal of Smoking Cessation 15, 171-174 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.L., Valencia, A.P., Marcinek, D.J. & Traustadottir, T. High intensity muscle stimulation activates a systemic Nrf2-mediated redox stress response. Free Radic Biol Med 172, 82-89 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Muthusamy, V.R., et al. Acute exercise stress activates Nrf2/ARE signaling and promotes antioxidant mechanisms in the myocardium. Free Radic Biol Med 52, 366-376 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Monir, D.M., Mahmoud, M.E., Ahmed, O.G., Rehan, I.F. & Abdelrahman, A. Forced exercise activates the NrF2 pathway in the striatum and ameliorates motor and behavioral manifestations of Parkinson’s disease in rotenone-treated rats. Behav Brain Funct 16, 9 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Li, T., et al. Effects of different exercise durations on Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway activation in mouse skeletal muscle. Free Radic Res 49, 1269-1274 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Done, A.J., Gage, M.J., Nieto, N.C. & Traustadottir, T. Exercise-induced Nrf2-signaling is impaired in aging. Free Radic Biol Med 96, 130-138 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, A.S., Jr., et al. Moderate-Intensity Physical Exercise Protects Against Experimental 6-Hydroxydopamine-Induced Hemiparkinsonism Through Nrf2-Antioxidant Response Element Pathway. Neurochem Res 41, 64-72 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Garbin, U., et al. Cigarette smoking blocks the protective expression of Nrf2/ARE pathway in peripheral mononuclear cells of young heavy smokers favouring inflammation. PLoS One 4, e8225 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Thompson, D., et al. Exercise-induced expression of heme oxygenase-1 in human lymphocytes. Free Radic Res 39, 63-69 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Baglole, C.J., Sime, P.J. & Phipps, R.P. Cigarette smoke-induced expression of heme oxygenase-1 in human lung fibroblasts is regulated by intracellular glutathione. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295, L624-636 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Shih, R.H., Cheng, S.E., Hsiao, L.D., Kou, Y.R. & Yang, C.M. Cigarette smoke extract upregulates heme oxygenase-1 via PKC/NADPH oxidase/ROS/PDGFR/PI3K/Akt pathway in mouse brain endothelial cells. J Neuroinflammation 8, 104 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Alves de Souza, R.W., et al. Skeletal muscle heme oxygenase-1 activity regulates aerobic capacity. Cell Rep 35, 109018 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Tang, K., Wagner, P.D. & Breen, E.C. TNF-alpha-mediated reduction in PGC-1alpha may impair skeletal muscle function after cigarette smoke exposure. J Cell Physiol 222, 320-327 (2010).

- Guo, M., et al. Cigarette smoking and mitochondrial dysfunction in peripheral artery disease. Vasc Med 28, 28-35 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Godoy, J.A., Valdivieso, A.G. & Inestrosa, N.C. Nicotine Modulates Mitochondrial Dynamics in Hippocampal Neurons. Mol Neurobiol 55, 8965-8977 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Borkar, N.A., et al. Nicotine affects mitochondrial structure and function in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 325, L803-L818 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Bae, E.J., et al. TNF-alpha promotes alpha-synuclein propagation through stimulation of senescence-associated lysosomal exocytosis. Exp Mol Med 54, 788-800 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y., et al. Neuroprotective effects of endurance exercise against neuroinflammation in MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease mice. Brain Res 1655, 186-193 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Leem, Y.H., Park, J.S., Park, J.E., Kim, D.Y. & Kim, H.S. Suppression of neuroinflammation and alpha-synuclein oligomerization by rotarod walking exercise in subacute MPTP model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem Int 165, 105519 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Petersen, A.M. & Pedersen, B.K. The anti-inflammatory effect of exercise. J Appl Physiol (1985) 98, 1154-1162 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Tuon, T., et al. Physical Training Regulates Mitochondrial Parameters and Neuroinflammatory Mechanisms in an Experimental Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015, 261809 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Kalkman, H.O. & Feuerbach, D. Modulatory effects of alpha7 nAChRs on the immune system and its relevance for CNS disorders. Cell Mol Life Sci 73, 2511-2530 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Otterbein, L.E., et al. Carbon monoxide has anti-inflammatory effects involving the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Nat Med 6, 422-428 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Guo, Q., Pan, X., Qin, L. & Zhang, P. Smoking and impaired bone healing: will activation of cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway be the bridge? Int Orthop 35, 1267-1270 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Lakhan, S.E. & Kirchgessner, A. Anti-inflammatory effects of nicotine in obesity and ulcerative colitis. J Transl Med 9, 129 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Stuckenholz, V., et al. The alpha7 nAChR agonist PNU-282987 reduces inflammation and MPTP-induced nigral dopaminergic cell loss in mice. J Parkinsons Dis 3, 161-172 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S., et al. 3-[(2,4-Dimethoxy)benzylidene]-anabaseine dihydrochloride protects against 6-hydroxydopamine-induced parkinsonian neurodegeneration through alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor stimulation in rats. J Neurosci Res 91, 462-471 (2013). [CrossRef]

- El-Zayadi, A.R. Heavy smoking and liver. World J Gastroenterol 12, 6098-6101 (2006).

- Arnson, Y., Shoenfeld, Y. & Amital, H. Effects of tobacco smoke on immunity, inflammation and autoimmunity. J Autoimmun 34, J258-265 (2010). [CrossRef]

- De Miguel, Z., et al. Exercise plasma boosts memory and dampens brain inflammation via clusterin. Nature 600, 494-499 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Carnevali, S., et al. Clusterin decreases oxidative stress in lung fibroblasts exposed to cigarette smoke. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 174, 393-399 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M., Van der Does, W., Elzinga, B.M., Molendijk, M.L. & Penninx, B.W. Association between smoking, nicotine dependence, and BDNF Val66Met polymorphism with BDNF concentrations in serum. Nicotine Tob Res 17, 323-329 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Shafiee, A., et al. Effect of smoking on Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) blood levels: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 349, 525-533 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Wrann, C.D., et al. Exercise induces hippocampal BDNF through a PGC-1alpha/FNDC5 pathway. Cell Metab. 18, 649-659 (2013).

- Kam, T.I., et al. Amelioration of pathologic alpha-synuclein-induced Parkinson’s disease by irisin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 119, e2204835119 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.Y.D., et al. The neuroprotective effect of nicotine in Parkinson’s disease models is associated with inhibiting PARP-1 and caspase-3 cleavage. PeerJ 5, e3933 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Charbonneau, P.-F. & Damier, P. Nicotine in Parkinson’s Disease — a Therapeutic Track Gone up in Smoke? NEJM Evidence 2, EVIDe2300167 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Urianstad, T., et al. Carbon monoxide supplementation: evaluating its potential to enhance altitude training effects and cycling performance in elite athletes. J Appl Physiol (1985) 137, 1092-1105 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Burtscher, J., Syed, M.M.K., Lashuel, H.A. & Millet, G.P. Hypoxia Conditioning as a Promising Therapeutic Target in Parkinson’s Disease? Mov Disord 36, 857-861 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Halliday, M.R., Abeydeera, D., Lundquist, A.J., Petzinger, G.M. & Jakowec, M.W. Intensive treadmill exercise increases expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha and its downstream transcript targets: a potential role in neuroplasticity. Neuroreport 30, 619-627 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Jain, I.H., et al. Hypoxia as a therapy for mitochondrial disease. Science 352, 54-61 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Jain, I.H., et al. Leigh Syndrome Mouse Model Can Be Rescued by Interventions that Normalize Brain Hyperoxia, but Not HIF Activation. Cell Metab 30, 824-832 e823 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Gutsaeva, D.R., et al. Transient hypoxia stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis in brain subcortex by a neuronal nitric oxide synthase-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci 28, 2015-2024 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Osorio, R.S., et al. Sleep-disordered breathing advances cognitive decline in the elderly. Neurology 84, 1964-1971 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Leng, Y., McEvoy, C.T., Allen, I.E. & Yaffe, K. Association of Sleep-Disordered Breathing With Cognitive Function and Risk of Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol 74, 1237-1245 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Yeh, N.C., Tien, K.J., Yang, C.M., Wang, J.J. & Weng, S.F. Increased Risk of Parkinson’s Disease in Patients With Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Population-Based, Propensity Score-Matched, Longitudinal Follow-Up Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 95, e2293 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Devos, D., et al. Targeting chelatable iron as a therapeutic modality in Parkinson’s disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 21, 195-210 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Devos, D., et al. Trial of Deferiprone in Parkinson’s Disease. N Engl J Med 387, 2045-2055 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Robledinos-Anton, N., Fernandez-Gines, R., Manda, G. & Cuadrado, A. Activators and Inhibitors of NRF2: A Review of Their Potential for Clinical Development. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019, 9372182 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Han, J.M., et al. Protective effect of sulforaphane against dopaminergic cell death. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 321, 249-256 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Deng, C., Tao, R., Yu, S.Z. & Jin, H. Inhibition of 6-hydroxydopamine-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress by sulforaphane through the activation of Nrf2 nuclear translocation. Mol Med Rep 6, 215-219 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Siebert, A., Desai, V., Chandrasekaran, K., Fiskum, G. & Jafri, M.S. Nrf2 activators provide neuroprotection against 6-hydroxydopamine toxicity in rat organotypic nigrostriatal cocultures. J Neurosci Res 87, 1659-1669 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Khot, M., et al. Dimethyl fumarate ameliorates parkinsonian pathology by modulating autophagy and apoptosis via Nrf2-TIGAR-LAMP2/Cathepsin D axis. Brain Res 1815, 148462 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Lastres-Becker, I., et al. Repurposing the NRF2 Activator Dimethyl Fumarate as Therapy Against Synucleinopathy in Parkinson’s Disease. Antioxid Redox Signal 25, 61-77 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, M., et al. Distinct Nrf2 Signaling Mechanisms of Fumaric Acid Esters and Their Role in Neuroprotection against 1-Methyl-4-Phenyl-1,2,3,6-Tetrahydropyridine-Induced Experimental Parkinson’s-Like Disease. J Neurosci 36, 6332-6351 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Jing, X., et al. Dimethyl fumarate attenuates 6-OHDA-induced neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells and in animal model of Parkinson’s disease by enhancing Nrf2 activity. Neuroscience 286, 131-140 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Lynch, D.R., et al. Efficacy of Omaveloxolone in Friedreich’s Ataxia: Delayed-Start Analysis of the MOXIe Extension. Mov Disord 38, 313-320 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Madsen, K.L., et al. Safety and efficacy of omaveloxolone in patients with mitochondrial myopathy: MOTOR trial. Neurology 94, e687-e698 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Pettersson-Klein, A.T., et al. Small molecule PGC-1alpha1 protein stabilizers induce adipocyte Ucp1 expression and uncoupled mitochondrial respiration. Mol Metab 9, 28-42 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.N., et al. Novel small-molecule PGC-1alpha transcriptional regulator with beneficial effects on diabetic db/db mice. Diabetes 62, 1297-1307 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B., et al. PGC-1alpha, a potential therapeutic target for early intervention in Parkinson’s disease. Sci Transl Med 2, 52ra73 (2010).

- Cheong, J.L.Y., de Pablo-Fernandez, E., Foltynie, T. & Noyce, A.J. The Association Between Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Parkinson’s Disease. J Parkinsons Dis 10, 775-789 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Lang, A.E. & Espay, A.J. Disease Modification in Parkinson’s Disease: Current Approaches, Challenges, and Future Considerations. Mov Disord 33, 660-677 (2018). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).