Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

14 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Geometric Structure of the World

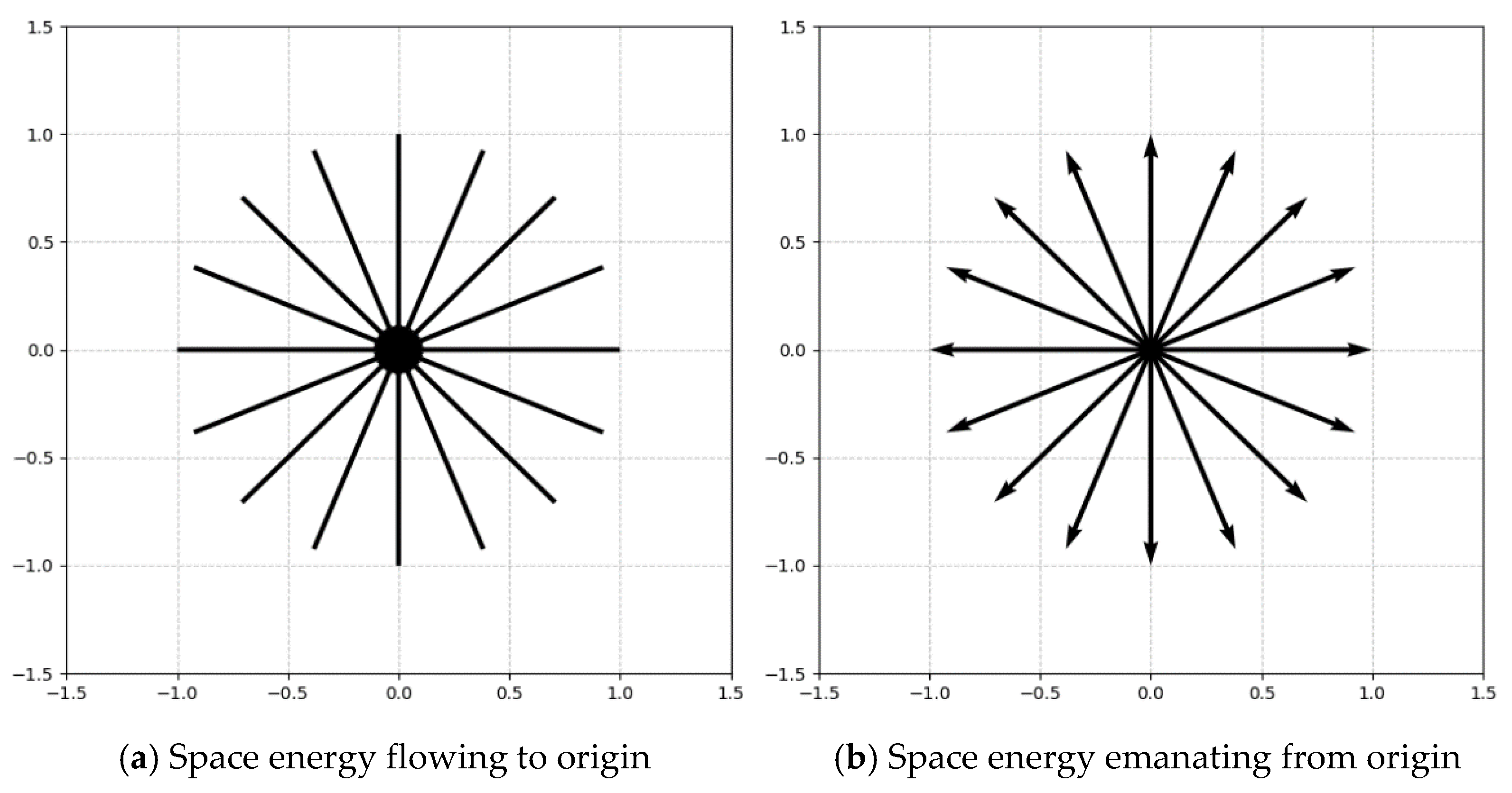

2.1. Matter-space Model

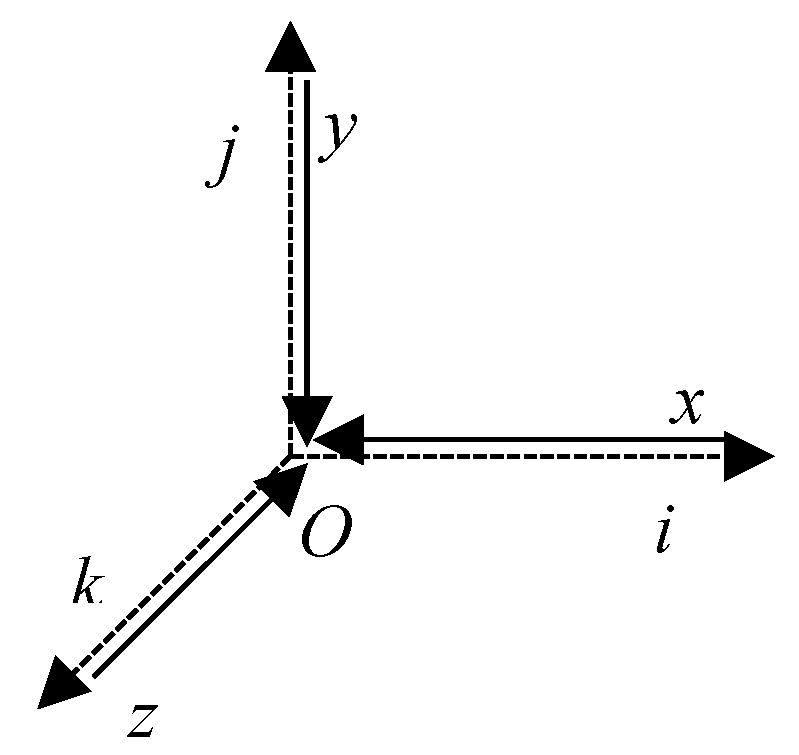

2.2.6. D Complex Spacetime

2.3. Space Vector Direction vs. Spin Direction

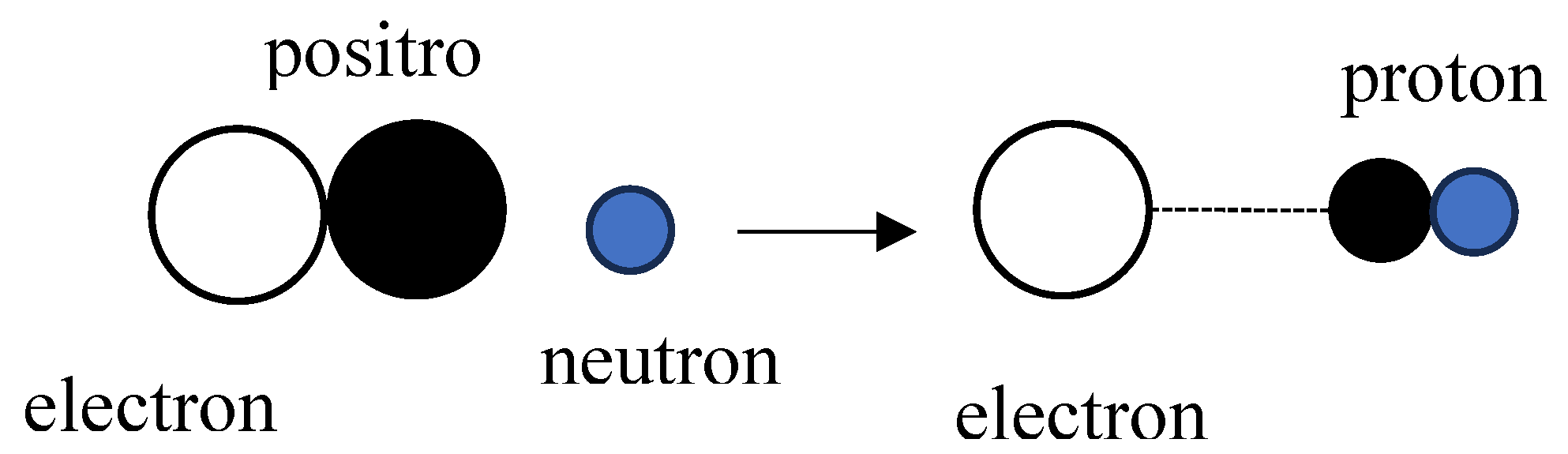

3. Neutron Universe Model

3.1. Origin of the Universe

3.2. Weak Interaction (Hawking Radiation = β-Radiation)

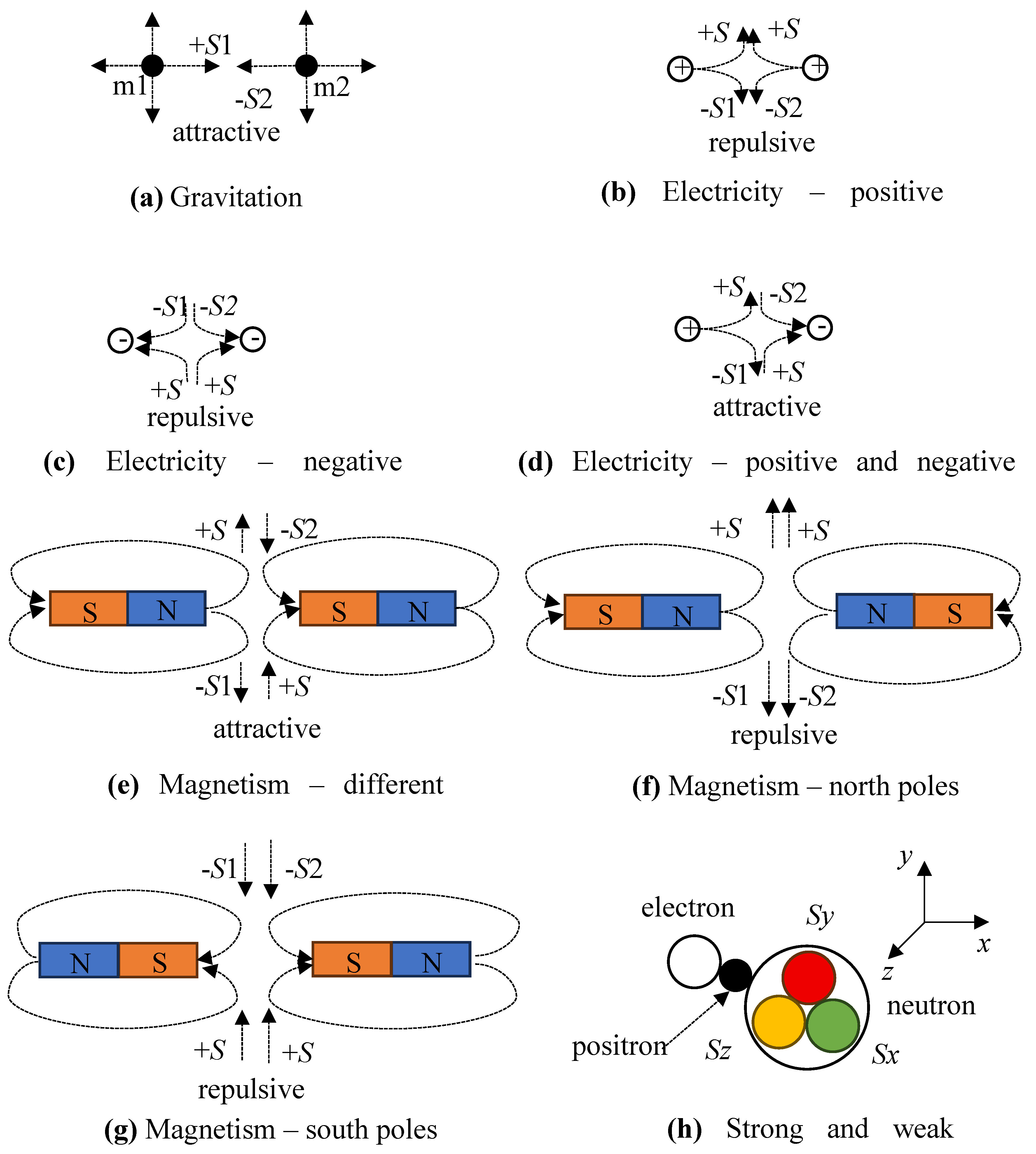

4. Unified Force Framework

4.1. Force Nature Formula

4.2. Potential Energy Formula

5. Discussions

- (1)

- The relative weakness of gravity and the origin of spacetime curvature. It can be explained through two mechanisms. First, as space diverges radially outward from a mass center in solid angles, its energy density diminishes with increasing radial distance. Second, as illustrated in Figure 4(a), gravitational attraction peaks along the axis connecting two objects’ centers of mass. At oblique angles, space vectors decompose into horizontal and vertical components. Crucially, only the horizontal component contributes to attraction, while the vertical component may induce repulsion, particularly when spins and share parallel upward alignment. This directional dependence also generates spacetime curvature: when an object passes near a massive body, it experiences maximized gravitational pull toward the body’s center, creating a trajectory bias toward the gravitational core. Concurrently, higher space energy density near massive bodies causes time dilation.

- (2)

- Short-range nature of strong and weak forces. Strong force: when neutrons are in close proximity, a symmetry (termed equal-weight in this framework enables quark-level interactions that produce attraction. However, as separation increases, particularly in nuclear peripheries, this symmetry breaks, causing the attractive force between quarks to attenuate exponentially with distance.

- (3)

- Origin of charge and revised Boson concept. This framework suggests the fundamental origin of electric charge emerges from energy separation in entangled particle-antiparticle pairs, where the particle endowed with positive/real energy manifests as negative charge, while its antiparticle counterpart carrying negative/imaginary energy manifests as positive charge. This energy-charge equivalence necessitates a revised conception of bosons: rather than elementary particles, bosons constitute entangled pairs of these positive and negative-energy entities whose net zero energy results in zero rest mass, with the positive-energy component possessing quantized energy . Upon measurement-induced entanglement collapse, this positive energy becomes detectable, as evidenced in phenomena like the photoelectric effect. Crucially, electron-positron annihilation provides experimental substantiation: when these separated fermions collide, they transform into entangled photon pairs, effectively converting fermionic closed strings into a bosonic open string configuration, where the charge-neutral fermion pair yields charge-neutral bosonic radiation, demonstrating the interconversion between separated charge states and integrated neutral bosonic states through entanglement dynamics.

6. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weinberg, S. A model of leptons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1967, 19, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgi, H.; Glashow, S.L. Unity of all elementary-particle forces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1974, 32, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.B.; Schwarz, J.H. Anomaly cancellations in supersymmetric D = 10 gauge theory and superstring theory. Phys. Lett. B 1984, 149, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. String theory dynamics in various dimensions. Nucl. Phys. B 1995, 443, 85–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C.; Smolin, L. Loop space representation of quantum general relativity. Nucl. Phys. B 1990, 331, 80–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiemann, T. Quantum spin dynamics (QSD). Class. Quantum Grav. 1998, 15, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlinde, E. On the origin of gravity and the laws of Newton. J. High Energ. Phys. 2011, 2011, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J.M. The large N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 1999, 38, 1113–1133. [Google Scholar]

- Searight, T.P. Mirror Matter from a Unified Field Theory. Found. Phys. 2021, 51, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adom, R. Manifestation of quantum forces in spacetime: towards a general theory of quantum forces. Found. Phys. 2025, 55, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partanen, M.; Tulkki, J. Gravity generated by four one-dimensional unitary gauge symmetries and the Standard Model. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2025, 88, 057802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashtekar, A.; Singh, P. Loop quantum cosmology: a status report. Class. Quantum Grav. 2011, 28, 213001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, L.; Cui, K.; Liu, X.; et al. Electron’s horizon in a 6-D complex space. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1804.04495. [Google Scholar]

- Omolo, J.A. Complex Spacetime Frame: Four-Vector Identities and Tensors. APM 2014, 4, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guido, G. The origin of the color charge into quarks. JHEPGC 2019, 5, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, S. Gravity theory with a dark extra dimension. Phys. Rev. D 2020, 101, 104040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisenberg, W. W. Zur Theorie des Ferromagnetismus. Z. Physik. 1928, 49, 619–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).