Submitted:

11 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Diets

2.2. Feeding Management

2.3. Growth Performance

2.4. Apparent Nutrient Metabolism

2.5. Digestive Organ Index

2.6. Jejunal Morphology

2.7. 16S rDNA Sequencing and Analysis

2.8. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Growth Performance

3.2. Apparent Nutrient Metabolism

3.3. Digestive Organ Index

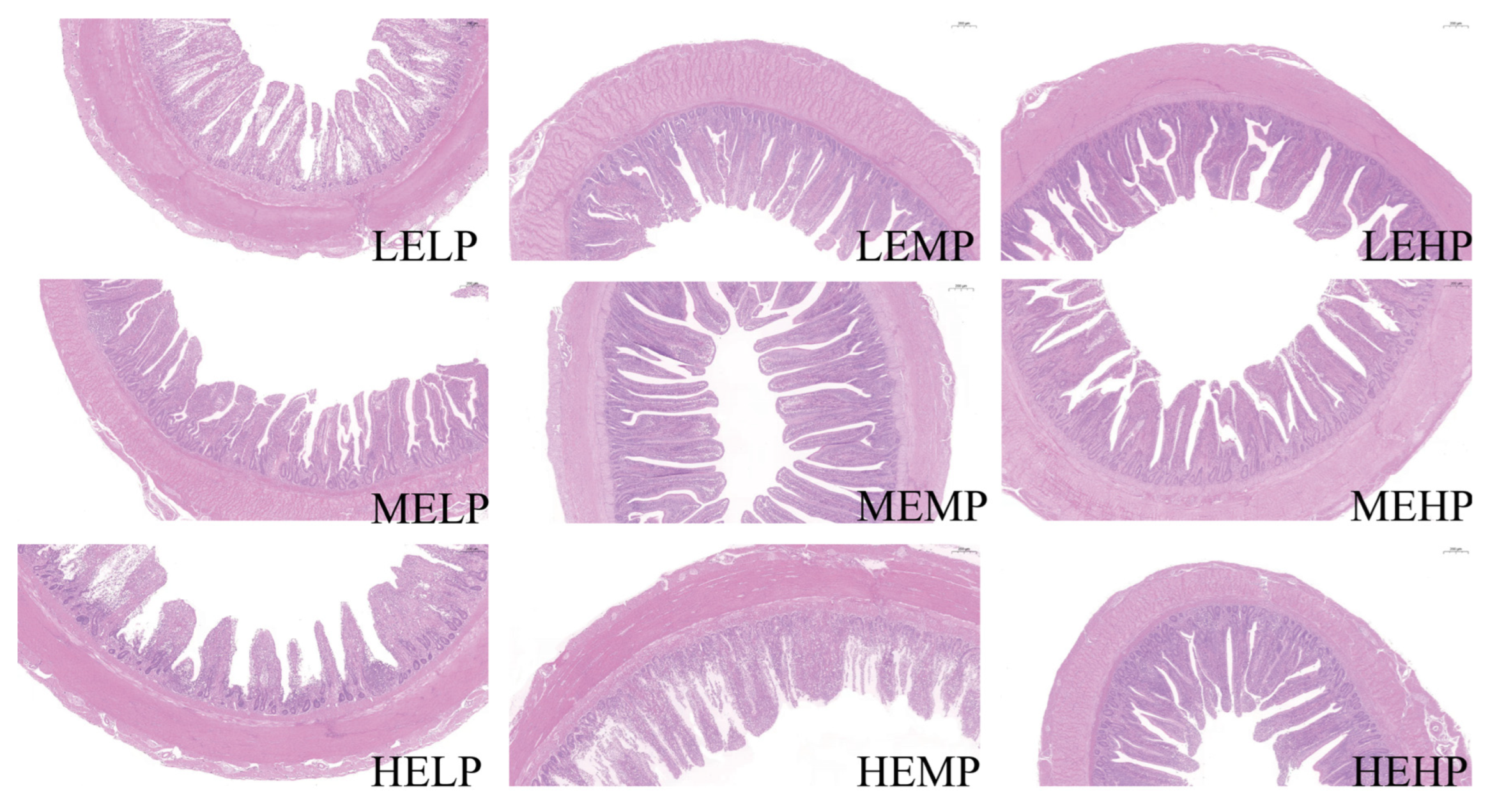

3.4. Jejunal Morphology

4. Discussion

4.1. Growth Performance and Apparent Nutrient Metabolism

4.2. Digestive Organ Index and Jejunal Morphology

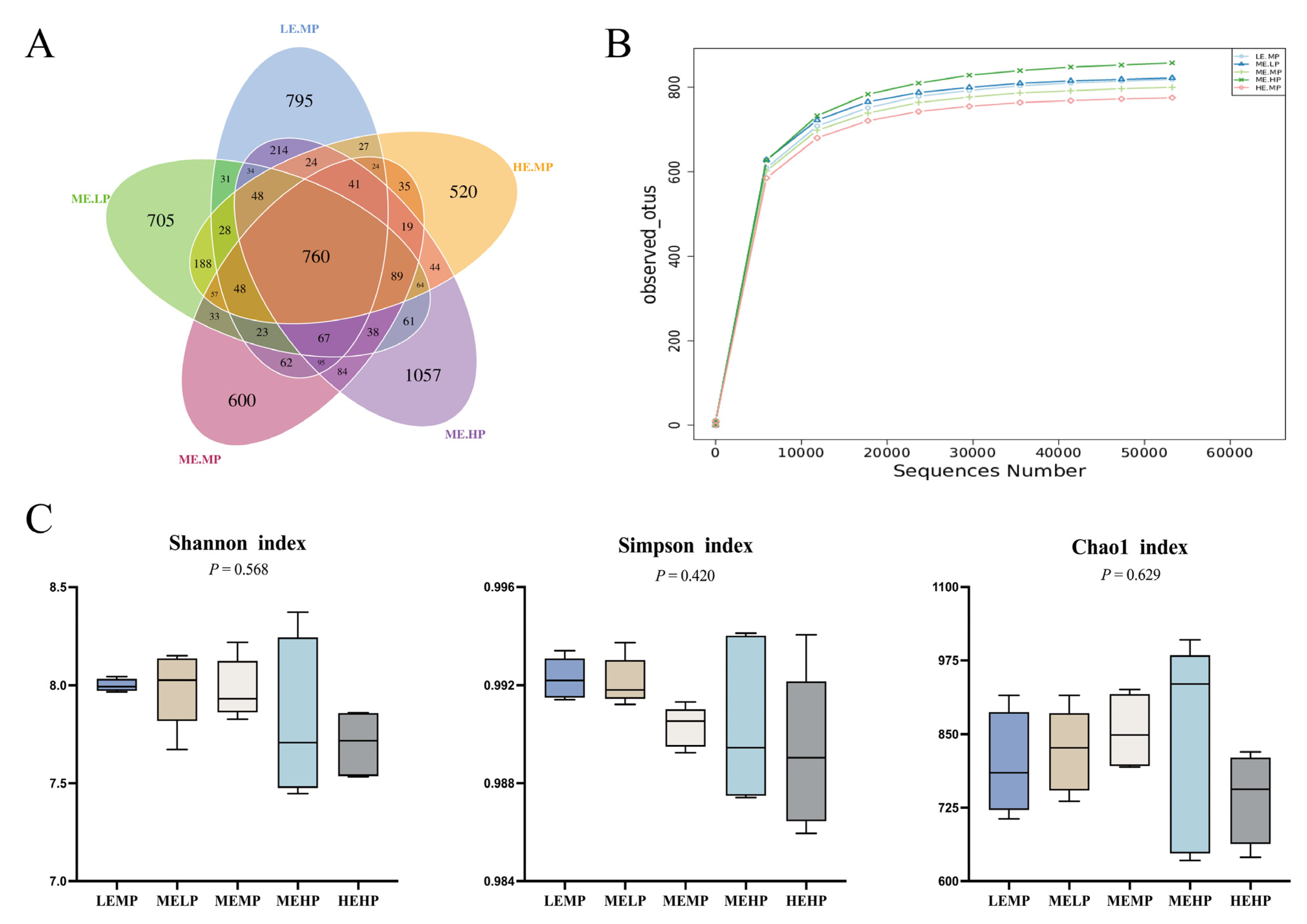

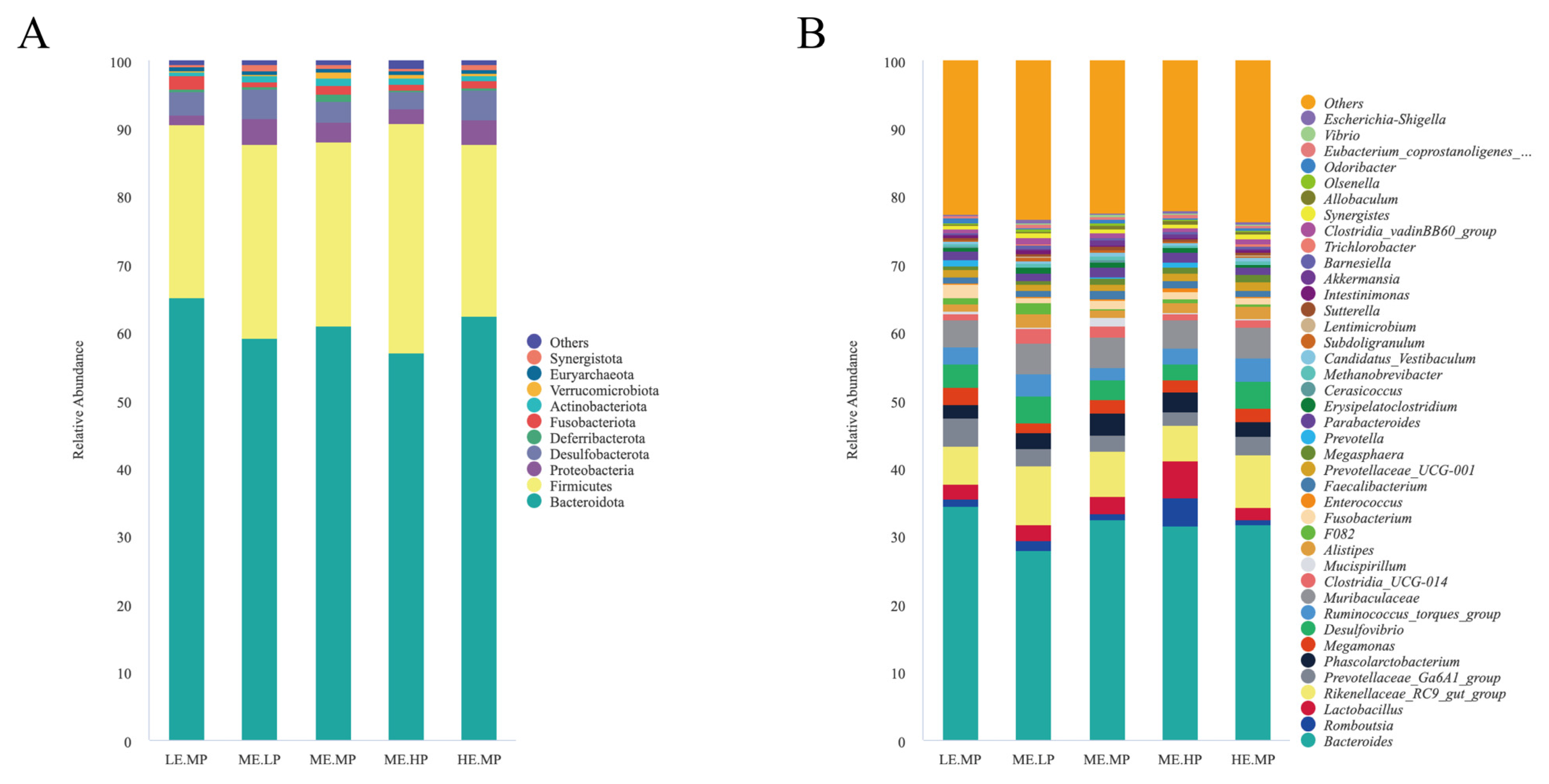

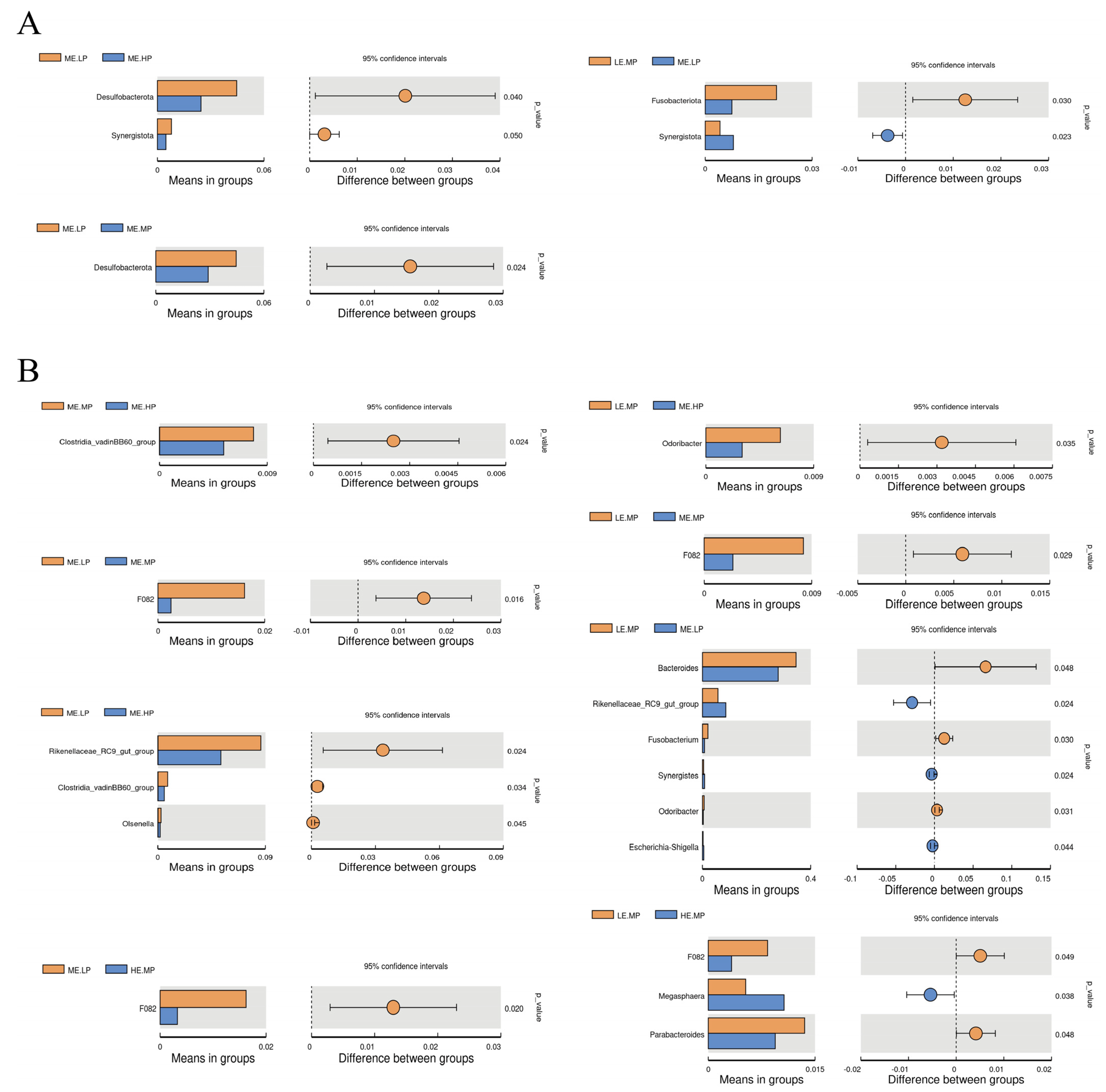

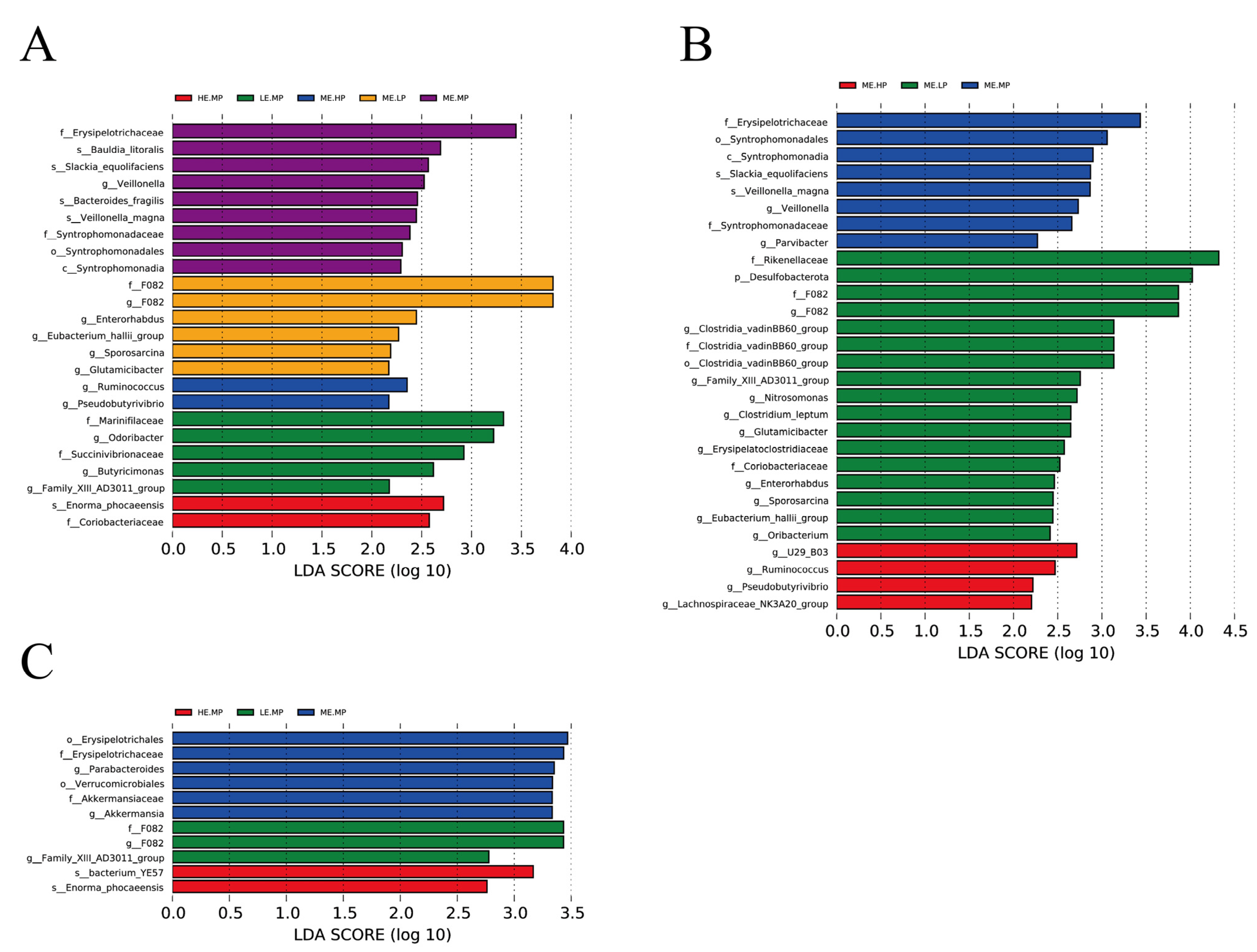

4.3. Cecal Microbiome

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ME | Metabolizable energy |

| CP | Crude protein |

| ADG | Average daily gain |

| F/G | Feed-to-gain ratio |

| VH | Villus height |

| CD | Crypt depth |

| MLT | Muscle layer thickness |

| DM | Dry matter |

| GE | Gross energy |

References

- Zhang, Qianqian, Hongtao Zhang, Yukun Jiang, Jianping Wang, De Wu, Caimei Wu, Lianqiang Che, Yan Lin, Yong Zhuo, Zheng Luo, Kangkang Nie, and Jian Li. “Chromium Propionate Supplementation to Energy- and Protein-Reduced Diets Reduces Feed Consumption but Improves Feed Conversion Ratio of Yellow-Feathered Male Broilers in the Early Period and Improves Meat Quality.” Poultry Science 103, no. 2 (2024): 103260.

- Shen, Yutian, Wentao Li, Lixia Kai, Yuqing Fan, Youping Wu, Fengqin Wang, Yizhen Wang, and Zeqing Lu. “Effects of Dietary Metabolizable Energy and Crude Protein Levels on Production Performance, Meat Quality and Cecal Microbiota of Taihe Silky Fowl during Growing Period.” Poultry Science 104, no. 1 (2025): 104654.

- Ko, Hanseo, Jinquan Wang, Josh Wen-Cheng Chiu, and Woo Kyun Kim. “Effects of Metabolizable Energy and Emulsifier Supplementation on Growth Performance, Nutrient Digestibility, Body Composition, and Carcass Yield in Broilers.” Poultry Science 102, no. 4 (2023): 102509.

- Laudadio, V., L. Passantino, A. Perillo, G. Lopresti, A. Passantino, R. U. Khan, and V. Tufarelli. “Productive Performance and Histological Features of Intestinal Mucosa of Broiler Chickens Fed Different Dietary Protein Levels.” Poultry Science 91, no. 1 (2012): 265-70.

- Yu, Yao, Chunxiao Ai, Caiwei Luo, and Jianmin Yuan. “Effect of Dietary Crude Protein and Apparent Metabolizable Energy Levels on Growth Performance, Nitrogen Utilization, Serum Parameter, Protein Synthesis, and Amino Acid Metabolism of 1- to 10-Day-Old Male Broilers.” International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25, no. 13 (2024).

- Hu, Hong, Ying Huang, Anjian Li, Qianhui Mi, Kunping Wang, Liang Chen, Zelong Zhao, Qiang Zhang, Xi Bai, and Hongbin Pan. “Effects of Different Energy Levels in Low-Protein Diet on Liver Lipid Metabolism in the Late-Phase Laying Hens through the Gut-Liver Axis.” Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology 15, no. 1 (2024): 98.

- Chang, C., Q. Q. Zhang, H. H. Wang, Q. Chu, J. Zhang, Z. X. Yan, H. G. Liu, and A. L. Geng. “Dietary Metabolizable Energy and Crude Protein Levels Affect Pectoral Muscle Composition and Gut Microbiota in Native Growing Chickens.” Poultry Science 102, no. 2 (2023): 102353.

- Goodarzi Boroojeni, Farshad, W. Vahjen, K. Männer, A. Blanch, D. Sandvang, and J. Zentek. “Bacillus Subtilis in Broiler Diets with Different Levels of Energy and Protein.” Poultry Science 97, no. 11 (2018): 3967-76.

- Li, Wentao, Lixia Kai, Wei Wei, Yuqing Fan, Yizhen Wang, and Zeqing Lu. “Dietary Metabolizable Energy and Crude Protein Levels Affect Taihe Silky Fowl Growth Performance, Meat Quality, and Cecal Microbiota during Fattening.” Poultry Science 103, no. 12 (2024): 104363.

- Zhou, Luli, Dingfa Wang, Khaled Abouelezz, Liguang Shi, Ting Cao, and Guanyu Hou. “Impact of Dietary Protein and Energy Levels on Fatty Acid Profile, Gut Microbiome and Cecal Metabolome in Native Growing Chickens.” Poultry Science 103, no. 8 (2024): 103917.

- Wen, Chaoliang, Wei Yan, Chunning Mai, Zhongyi Duan, Jiangxia Zheng, Congjiao Sun, and Ning Yang. “Joint Contributions of the Gut Microbiota and Host Genetics to Feed Efficiency in Chickens.” Microbiome 9, no. 1 (2021): 126.

- Jackson, Starr, J. D. Summers, and S. Leeson. “Effect of Dietary Protein and Energy on Broiler Carcass Composition and Efficiency of Nutrient Utilization.” Poultry Science 61, no. 11 (1982): 2224-31.

- Zhao, J. P., J. L. Chen, G. P. Zhao, M. Q. Zheng, R. R. Jiang, and J. Wen. “Live Performance, Carcass Composition, and Blood Metabolite Responses to Dietary Nutrient Density in Two Distinct Broiler Breeds of Male Chickens1.” Poultry Science 88, no. 12 (2009): 2575-84.

- Candrawati, Desak Putu Mas Ari. “The Effect of Different Energy-Protein Ratio in Diets on Feed Digestibility and Performance of Native Chickens in the Starter Phase.” International Journal of Fauna and Biological Studies 7 (2020): 92-96.

- Matus-Aragón, Miguel Ángel, Fernando González-Cerón, Josafhat Salinas-Ruiz, Eliseo Sosa-Montes, Arturo Pro-Martínez, Omar Hernández-Mendo, Juan Manuel Cuca-García, and David Jesús Chan-Díaz. “Productive Performance of Mexican Creole Chickens from Hatching to 12 Weeks of Age Fed Diets with Different Concentrations of Metabolizable Energy and Crude Protein.” Animal Bioscience 34, no. 11 (2021): 1794-801.

- Dong, Liping, Yumei Li, Yonghong Zhang, Yan Zhang, Jing Ren, Jinlei Zheng, Jizhe Diao, Hongyu Ni, Yijing Yin, Ruihong Sun, Fangfang Liang, Peng Li, Changhai Zhou, and Yuwei Yang. “Effects of Organic Zinc on Production Performance, Meat Quality, Apparent Nutrient Digestibility and Gut Microbiota of Broilers Fed Low-Protein Diets.” Scientific Reports 13, no. 1 (2023): 10803.

- Mera-Zúñiga, F., A. Pro-Martínez, J. F. Zamora-Natera, E. Sosa-Montes, J. D. Guerrero-Rodríguez, S. I. Mendoza-Pedroza, J. M. Cuca-García, R. M. López-Romero, D. Chan-Díaz, C. M. Becerril-Pérez, A. J. Vargas-Galicia, and J. Bautista-Ortega. “Soybean Meal Substitution by Dehulled Lupine (Lupinus Angustifolius) with Enzymes in Broiler Diets.” Asian-Australas J Anim Sci 32, no. 4 (2019): 564-73.

- Hou, Jinwang, Lizhi Lu, Lina Lian, Yong Tian, Tao Zeng, Yanfen Ma, Sisi Li, Li Chen, Wenwu Xu, Tiantian Gu, Guoqin Li, and Xin Liu. “Effects of Coated Sodium Butyrate on the Growth Performance, Serum Biochemistry, Antioxidant Capacity, Intestinal Morphology, and Intestinal Microbiota of Broiler Chickens.” Frontiers In Microbiology 15 (2024): 1368736.

- Corsetti, Giovanni, Evasio Pasini, Tiziano M. Scarabelli, Claudia Romano, Arashpreet Singh, Carol C. Scarabelli, and Francesco S. Dioguardi. “Importance of Energy, Dietary Protein Sources, and Amino Acid Composition in the Regulation of Metabolism: An Indissoluble Dynamic Combination for Life.” Nutrients 16, no. 15 (2024): 2417.

- Dairo, Festus, Akinyele Adesehinwa, A. T, and J. Oluyemi. “High and Low Dietary Energy and Protein Levels for Broiler Chickens.” African Journal of Agricultural Research 5 (2010): 2030-38.

- Musigwa, Sosthene, Natalie Morgan, Robert A. Swick, Pierre Cozannet, and Shu-Biao Wu. “Energy Dynamics, Nitrogen Balance, and Performance in Broilers Fed High- and Reduced-Cp Diets.” Journal of Applied Poultry Research 29, no. 4 (2020): 830-41.

- Zeng, Q. F., P. Cherry, A. Doster, R. Murdoch, O. Adeola, and T. J. Applegate. “Effect of Dietary Energy and Protein Content on Growth and Carcass Traits of Pekin Ducks.” Poultry Science 94, no. 3 (2015): 384-94.

- Geng, Ai Lian, Qian Qian Zhang, Cheng Chang, Hai Hong Wang, Qin Chu, Jian Zhang, Zhi Xun Yan, and Hua Gui Liu. “Dietary Metabolizable Energy and Crude Protein Levels Affect the Performance, Egg Quality and Biochemical Parameters of a Dual-Purpose Chicken.” Animal Biotechnology 34, no. 7 (2023): 2714-23.

- Frikha, M., H. M. Safaa, E. Jiménez-Moreno, R. Lázaro, and G. G. Mateos. “Influence of Energy Concentration and Feed Form of the Diet on Growth Performance and Digestive Traits of Brown Egg-Laying Pullets from 1 to 120 Days of Age.” Animal Feed Science and Technology 153, no. 3 (2009): 292-302.

- Yang, Haiming, Zhi Yang, Zhiyue Wang, Wei Wang, Kaihua Huang, Wenjia Fan, and Tianli Jia. “Effects of Early Dietary Energy and Protein Dilution on Growth Performance, Nutrient Utilization and Internal Organs of Broilers.” Italian Journal of Animal Science 14, no. 2 (2015): 3729.

- Peng, Jie, Weiying Huang, Wei Zhang, Yanlin Zhang, Menglin Yang, Shiqi Zheng, Yantao Lv, Hongyan Gao, Wei Wang, Jian Peng, and Yanhua Huang. “Effect of Different Dietary Energy/Protein Ratios on Growth Performance, Reproductive Performance of Breeding Pigeons and Slaughter Performance, Meat Quality of Squabs in Summer.” Poultry Science 102, no. 7 (2023): 102577.

- Incharoen, Tossaporn, Koh-en Yamauchi, Tomoki Erikawa, and Hisaya Gotoh. “Histology of Intestinal Villi and Epithelial Cells in Chickens Fed Low-Crude Protein or Low-Crude Fat Diets.” Italian Journal of Animal Science 9, no. 4 (2010): e82.

- Sun, Z. H., Z. X. He, Q. L. Zhang, Z. L. Tan, X. F. Han, S. X. Tang, C. S. Zhou, M. Wang, and Q. X. Yan. “Effects of Energy and Protein Restriction, Followed by Nutritional Recovery on Morphological Development of the Gastrointestinal Tract of Weaned Kids1.” Journal of Animal Science 91, no. 9 (2013): 4336-44.

- Gu, X., and D. Li. “Effect of Dietary Crude Protein Level on Villous Morphology, Immune Status and Histochemistry Parameters of Digestive Tract in Weaning Piglets.” Animal Feed Science and Technology 114, no. 1 (2004): 113-26.

- Buwjoom, T., K. Yamauchi, T. Erikawa, and H. Goto. “Histological Intestinal Alterations in Chickens Fed Low Protein Diet.” Journal of Animal Physiology and Animal Nutrition 94, no. 3 (2010): 354-61.

- Houshmand, M., K. Azhar, I. Zulkifli, M. H. Bejo, and A. Kamyab. “Effects of Nonantibiotic Feed Additives on Performance, Nutrient Retention, Gut Ph, and Intestinal Morphology of Broilers Fed Different Levels of Energy.” Journal of Applied Poultry Research 20, no. 2 (2011): 121-28.

- Garçon, C. J. J., J. L. Ellis, C. D. Powell, A. Navarro Villa, A. I. Garcia Ruiz, J. France, and S. de Vries. “A Dynamic Model to Measure Retention of Solid and Liquid Digesta Fractions in Chickens Fed Diets with Differing Fibre Sources.” animal 17, no. 7 (2023): 100867.

- Yokoyama, M. T., and J. R. Carlson. “Microbial Metabolites of Tryptophan in the Intestinal Tract with Special Reference to Skatole.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 32, no. 1 (1979): 173-78.

- Huang, Yichen, Xing Shi, Zhiyong Li, Yang Shen, Xinxin Shi, Liying Wang, Gaofei Li, Ye Yuan, Jixiang Wang, Yongchao Zhang, Lei Zhao, Meng Zhang, Yu Kang, and Ying Liang. “Possible Association of Firmicutes in the Gut Microbiota of Patients with Major Depressive Disorder.” Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 14 (2018): 3329-37.

- Willis, C. L., J. H. Cummings, G. Neale, and G. R. Gibson. “Nutritional Aspects of Dissimilatory Sulfate Reduction in the Human Large Intestine.” Current Microbiology 35, no. 5 (1997): 294-98.

- Rowan, Fiachra, Neil G. Docherty, Madeline Murphy, T. Brendan Murphy, J. Calvin Coffey, and P. Ronan O’Connell. “Bacterial Colonization of Colonic Crypt Mucous Gel and Disease Activity in Ulcerative Colitis.” Annals of Surgery 252, no. 5 (2010): 869-75.

- Zhou, Xinhong, Shiyi Li, Yilong Jiang, Jicheng Deng, Chuanpeng Yang, Lijuan Kang, Huaidan Zhang, and Xianxin Chen. “Use of Fermented Chinese Medicine Residues as a Feed Additive and Effects on Growth Performance, Meat Quality, and Intestinal Health of Broilers.” Frontiers In Veterinary Science 10 (2023): 1157935.

- Saleem, Kinza, Saima, Abdur Rahman, Talat Naseer Pasha, Athar Mahmud, and Zafar Hayat. “Effects of Dietary Organic Acids on Performance, Cecal Microbiota, and Gut Morphology in Broilers.” Tropical Animal Health and Production 52, no. 6 (2020): 3589-96.

- Yin, Zhenchen, Shuyun Ji, Jiantao Yang, Wei Guo, Yulong Li, Zhouzheng Ren, and Xiaojun Yang. “Cecal Microbial Succession and Its Apparent Association with Nutrient Metabolism in Broiler Chickens.” mSphere 8, no. 3 (2023): e00614-22.

- Liu, Yue, Akiber Chufo Wachemo, HaiRong Yuan, and XiuJin Li. “Anaerobic Digestion Performance and Microbial Community Structure of Corn Stover in Three-Stage Continuously Stirred Tank Reactors.” Bioresource Technology 287 (2019): 121339.

- Sebastià, Cristina, M. Folch Josep, Maria Ballester, Jordi Estellé, Magí Passols, María Muñoz, M. García-Casco Juan, I. Fernández Ana, Anna Castelló, Armand Sánchez, and Daniel Crespo-Piazuelo. “Interrelation between Gut Microbiota, Scfa, and Fatty Acid Composition in Pigs.” mSystems 9, no. 1 (2023): e01049-23.

- Han, Haoqi, Liyang Zhang, Yuan Shang, Mingyan Wang, Clive J. C. Phillips, Yao Wang, Chuanyou Su, Hongxia Lian, Tong Fu, and Tengyun Gao. “Replacement of Maize Silage and Soyabean Meal with Mulberry Silage in the Diet of Hu Lambs on Growth, Gastrointestinal Tissue Morphology, Rumen Fermentation Parameters and Microbial Diversity.” Animals, no. 11 (2022).

- Zhu, Yixiao, Zhisheng Wang, Rui Hu, Xueying Wang, Fengpeng Li, Xiangfei Zhang, Huawei Zou, Quanhui Peng, Bai Xue, and Lizhi Wang. “Comparative Study of the Bacterial Communities Throughout the Gastrointestinal Tract in Two Beef Cattle Breeds.” Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 105, no. 1 (2021): 313-25.

- Ma, Jiayu, Jian Wang, Shad Mahfuz, Shenfei Long, Di Wu, Jie Gao, and Xiangshu Piao. “Supplementation of Mixed Organic Acids Improves Growth Performance, Meat Quality, Gut Morphology and Volatile Fatty Acids of Broiler Chicken.” Animals, no. 11 (2021).

- Kou, Ruixin, Jin Wang, Ang Li, Yuanyifei Wang, Dancai Fan, Bowei Zhang, Wenhui Fu, Jingmin Liu, Hanyue Fu, and Shuo Wang. “2’-Fucosyllactose Alleviates Ova-Induced Food Allergy in Mice by Ameliorating Intestinal Microecology and Regulating the Imbalance of Th2/Th1 Proportion.” Food & Function 14, no. 24 (2023): 10924-40.

- Zhang, Bing, Haoran Zhang, Yang Yu, Ruiqiang Zhang, Yanping Wu, Min Yue, and Caimei Yang. “Effects of Bacillus Coagulans on Growth Performance, Antioxidant Capacity, Immunity Function, and Gut Health in Broilers.” Poultry Science 100, no. 6 (2021): 101168.

- Huber-Ruano, Isabel, Enrique Calvo, Jordi Mayneris-Perxachs, M. Mar Rodríguez-Peña, Victòria Ceperuelo-Mallafré, Lídia Cedó, Catalina Núñez-Roa, Joan Miro-Blanch, María Arnoriaga-Rodríguez, Aurélie Balvay, Claire Maudet, Pablo García-Roves, Oscar Yanes, Sylvie Rabot, Ghjuvan Micaelu Grimaud, Annachiara De Prisco, Angela Amoruso, José Manuel Fernández-Real, Joan Vendrell, and Sonia Fernández-Veledo. “Orally Administered Odoribacter Laneus Improves Glucose Control and Inflammatory Profile in Obese Mice by Depleting Circulating Succinate.” Microbiome 10, no. 1 (2022): 135.

| Items | LE | ME | HE | ||||||

| LP | MP | HP | LP | MP | HP | LP | MP | HP | |

| Ingredients, % | |||||||||

| Corn | 47.32 | 44.00 | 47.18 | 47.92 | 49.02 | 46.50 | 50.27 | 48.40 | 47.34 |

| Soybean meal | 6.98 | 11.85 | 18.10 | 7.90 | 13.56 | 18.78 | 8.03 | 12.22 | 16.10 |

| Wheat middling | 16.70 | 18.00 | 11.50 | 18.00 | 13.80 | 14.20 | 14.50 | 13.70 | 12.00 |

| Soybean oil | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 3.40 | 3.40 | 3.40 |

| Wheat barn | 21.80 | 19.17 | 16.60 | 18.20 | 15.80 | 12.90 | 16.94 | 14.94 | 12.90 |

| Corn protein meal | 1.10 | 1.16 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.82 | 2.45 | 3.50 |

| Mountain flour | 1.72 | 1.72 | 1.66 | 1.64 | 1.60 | 1.58 | 1.60 | 1.58 | 1.54 |

| CaHPO4 | 1.30 | 1.26 | 1.29 | 1.38 | 1.40 | 1.38 | 1.45 | 1.44 | 1.45 |

| NaCl | 0.50 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.40 |

| Premix1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Lys | 0.34 | 0.23 | 0.09 | 0.33 | 0.22 | 0.08 | 0.35 | 0.25 | 0.17 |

| L-Met | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.20 |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Analysis results of nutrient level2 | |||||||||

| DM, % | 94.66 | 94.06 | 94.96 | 94.63 | 95.24 | 95.50 | 96.48 | 95.60 | 94.66 |

| Gross energy, MJ/kg |

11.27 | 11.20 | 11.20 | 11.70 | 11.70 | 11.70 | 12.12 | 12.13 | 12.13 |

| CP, % | 13.53 | 15.40 | 17.26 | 14.80 | 15.33 | 16.71 | 14.44 | 15.35 | 16.93 |

| Nutrient levels3 | |||||||||

| CP, % | 14.00 | 15.52 | 17.01 | 14.00 | 15.50 | 17.03 | 14.04 | 15.50 | 17.01 |

| ME, MJ/kg | 11.28 | 11.28 | 11.29 | 11.70 | 11.70 | 11.69 | 12.12 | 12.12 | 12.13 |

| Ca, % | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.07 | 1.07 |

| P, % | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| AP, % | 0.35 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.40 |

| Ca/P | 1.42 | 1.44 | 1.44 | 1.42 | 1.43 | 1.43 | 1.43 | 1.43 | 1.43 |

| Lys, % | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.85 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| Met, % | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.41 |

| ME, MJ/kg | CP, % | ADG/g | ADFI/g | F/G |

| 11.28 | 14.0 | 21.52d | 78.99ab | 3.67a |

| 15.5 | 21.26d | 78.68abc | 3.70a | |

| 17.0 | 21.52d | 76.93c | 3.58ab | |

| 11.70 | 14.0 | 21.66d | 78.54abc | 3.62ab |

| 15.5 | 24.02a | 77.66bc | 3.23d | |

| 17.0 | 22.67c | 77.00c | 3.40c | |

| 12.12 | 14.0 | 21.58d | 77.59bc | 3.60ab |

| 15.5 | 22.35c | 78.71abc | 3.52bc | |

| 17.0 | 23.34b | 79.83a | 3.42c | |

| SEM | 0.187 | 0.240 | 0.030 | |

| Main effect means | ||||

| ME | 11.28 | 21.43b | 78.20 | 3.65a |

| 11.70 | 22.78a | 77.73 | 3.42b | |

| 12.12 | 22.42a | 78.71 | 3.51b | |

| CP | 14.0 | 21.59b | 78.37 | 3.63a |

| 15.5 | 22.54a | 78.35 | 3.49b | |

| 17.0 | 22.51a | 77.92 | 3.47b | |

| P-value | ME | <0.001 | 0.139 | <0.001 |

| CP | <0.001 | 0.558 | <0.001 | |

| ME*CP | <0.001 | 0.011 | <0.001 | |

| ME, MJ/kg | CP, % | Dry matter % | Gross energy % | Crude protein % |

| 11.28 | 14.0 | 64.77 | 62.47 | 67.03ab |

| 15.5 | 64.50 | 63.04 | 67.29a | |

| 17.0 | 64.15 | 65.60 | 64.63c | |

| 11.70 | 14.0 | 64.25 | 65.37 | 65.85abc |

| 15.5 | 65.01 | 67.21 | 66.51ab | |

| 17.0 | 64.42 | 67.08 | 65.56bc | |

| 12.12 | 14.0 | 64.38 | 67.23 | 62.70d |

| 15.5 | 63.95 | 66.33 | 64.67c | |

| 17.0 | 64.19 | 66.66 | 64.32c | |

| SEM | 0.089 | 0.382 | 0.309 | |

| Main effect means | ||||

| ME | 11.28 | 64.47 | 63.70b | 66.32a |

| 11.70 | 64.56 | 66.55a | 65.97a | |

| 12.12 | 64.17 | 66.74a | 63.90b | |

| CP | 14.0 | 64.46 | 65.02 | 65.19b |

| 15.5 | 64.49 | 65.53 | 66.16a | |

| 17.0 | 64.25 | 66.45 | 64.84b | |

| P-value | ME | 0.135 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CP | 0.418 | 0.061 | 0.018 | |

| ME*CP | 0.100 | 0.071 | 0.021 | |

| ME, MJ/kg | CP, % | Proventriculus/g | Gizzard/g | Duodenum/cm | Jejunoileum/cm | Cecum/cm |

| 11.28 | 14.0 | 5.37 | 39.30ab | 22.20b | 107.75 | 36.00 |

| 15.5 | 5.33 | 36.85bc | 21.00b | 113.50 | 38.00 | |

| 17.0 | 5.20 | 33.39c | 23.20b | 114.20 | 39.00 | |

| 11.70 | 14.0 | 4.98 | 35.96bc | 22.23b | 97.50 | 32.60 |

| 15.5 | 5.91 | 38.35ab | 27.20a | 121.25 | 33.80 | |

| 17.0 | 5.52 | 34.34c | 21.50b | 112.40 | 35.40 | |

| 12.12 | 14.0 | 5.57 | 39.05ab | 22.20b | 108.20 | 36.20 |

| 15.5 | 6.02 | 39.64ab | 21.80b | 121.00 | 38.00 | |

| 17.0 | 6.53 | 40.96a | 26.25a | 119.20 | 42.75 | |

| SEM | 0.114 | 0.521 | 0.386 | 1.746 | 0.643 | |

| Main effect means | ||||||

| ME | 11.28 | 5.30b | 36.54b | 22.21b | 112.00 | 37.54a |

| 11.70 | 5.38b | 36.07b | 23.80a | 110.54 | 33.93b | |

| 12.12 | 6.00a | 39.77a | 23.21ab | 115.79 | 38.77a | |

| CP | 14.0 | 5.30 | 38.10 | 22.21 | 104.48b | 34.93b |

| 15.5 | 5.75 | 38.28 | 23.50 | 118.58a | 36.60ab | |

| 17.0 | 5.75 | 36.23 | 23.62 | 115.27a | 38.77a | |

| P-value | ME | 0.011 | 0.002 | 0.039 | 0.283 | <0.001 |

| CP | 0.100 | 0.099 | 0.055 | 0.002 | 0.011 | |

| ME*CP | 0.223 | 0.034 | <0.001 | 0.471 | 0.699 | |

| ME, MJ/kg | CP, % |

Crypt Depth, CD/μm |

Villus Height, VH/μm |

VH/CD |

Muscle Layer Thickness, MLT/μm |

| 11.28 | 14.0 | 128.19de | 702.44c | 5.33bc | 271.45ab |

| 15.5 | 131.10cd | 699.45c | 5.08cd | 276.10ab | |

| 17.0 | 135.15abc | 628.31d | 4.62de | 279.55a | |

| 11.70 | 14.0 | 132.51bcd | 744.55b | 4.98cd | 182.95d |

| 15.5 | 131.83bcd | 799.02a | 6.24a | 280.55a | |

| 17.0 | 130.32cd | 684.28c | 5.15bc | 246.30c | |

| 12.12 | 14.0 | 139.53a | 679.58c | 5.11bcd | 273.67ab |

| 15.5 | 123.68e | 629.25d | 4.39e | 247.85c | |

| 17.0 | 136.84ab | 753.82b | 5.60b | 256.47bc | |

| SEM | 0.626 | 4.854 | 0.063 | 3.050 | |

| Main effect means | |||||

| ME | 11.28 | 132.25 | 675.89b | 4.97b | 275.79a |

| 11.70 | 131.41 | 737.09a | 5.44a | 220.62c | |

| 12.12 | 134.05 | 688.12b | 5.12b | 261.28b | |

| CP | 14.0 | 134.58a | 703.63ab | 5.12 | 227.78b |

| 15.5 | 129.38b | 714.03a | 5.33 | 270.05a | |

| 17.0 | 133.65a | 681.29b | 5.10 | 259.74a | |

| P-value | ME | 0.359 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| CP | <0.001 | 0.043 | 0.624 | <0.001 | |

| ME*CP | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).