Introduction

Malnutrition is commonly observed among hospitalized patients, particularly older adults. However, it is often goes unrecognized and appropriate nutritional support is not consistently initiated upon admission. Traditionally, nutrition support teams [NSTs] were primarily consulted when attending physicians encountered difficulties in managing patients with evident nutritional deficiencies, especially regarding artificial nutrition. Although NSTs were originally established as multidisciplinary teams specializing in the initiation and management of artificial nutrition, the recent availability of a wide range of nutritional products has diminished the effectiveness of conventional reactive nutrition support approaches [

1].

To improve patient outcomes, it is essential to establish a systematic framework in which nutritional screening at admission, comprehensive nutritional assessment, and a formal diagnosis of malnutrition are routinely conducted. Such a framework should be supported by an institution-wide coordinated nutritional support system. The use of the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition [GLIM] criteria is recommended for diagnosing malnutrition [

2].

Based on patients’ nutritional status, individualized nutritional goals should be established upon admission, and evidence-based interventions—primarily involving dietary modification and oral nutritional supplementation [ONS]—should be implemented.

Kagansky et al. assessed the nutritional status of 414 hospitalized patients using the Mini Nutritional Assessment®, a validated screening tool. Their study demonstrated that malnourished patients had longer hospital stays, higher in-hospital mortality rates, and worse overall survival compared to well-nourished patients. Survival curves stratified by nutritional status [well-nourished, at risk of malnutrition, and malnourished] clearly indicated a significant association between poor nutritional status and worse prognosis among older inpatients [

3].

In Japan, inpatient care protocols require that patients undergo nutritional screening upon admission to determine the need for special nutritional management by a multidisciplinary team. If indicated, a comprehensive nutritional assessment must follow, leading to the formulation of a formal nutritional care plan, as mandated by facility accreditation standards. When this process becomes a mere formality, there is a risk that malnourished older patients will be overlooked, allowing their condition to worsen during hospitalization. Nutritional screening should be performed using reliable and validated tools, and in principle, should be conducted for all hospitalized patients.

Preoperative nutritional status is an important determinant of postoperative complications and length of stay. Also, in the field of oral and maxillofacial surgery, where many patients are older adults, the implementation of nutritional assessments is particularly warranted.

At the Osaka Dental University Hospital, a university-affiliated hospital specializing in dental care, the majority of inpatients are undergoing perioperative care in the oral and maxillofacial surgery department. All inpatients undergo nutritional screening using the Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 [NRS-2002], a tool validated for use in acutely disease adults [

4]. For patients identified as being at nutritional risk, further nutritional assessment is conducted based on the GLIM criteria.

The NRS-2002 is a widely used and reliable screening tool, primarily applied to adult patients in acute care hospitals. Its clinical utility has been demonstrated in various surgical settings [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. However, there is a paucity of systematic reports on inpatient nutritional screening in the field of dental and oral surgery.

This retrospective observational study, conducted under the leadership of the nutrition support team [NST], aims to investigate the clinical utility of NRS-2002 in patients hospitalized in the oral and maxillofacial surgery department. The study will evaluate the relationship between the NRS-2002 score at admission and clinical factors such as the purpose of hospitalization, anthropometric indices [height, weight, BMI], and length of hospital stay. Additionally, the study will examine the clinical characteristics of patients with an NRS-2002 score of ≥3.

Results

An overview of patient characteristics is presented in

Table 1. The mean age of the total cohort was 35.1 years, with females [34.4 years] tending to be slightly younger than males [36.3 years]. There were notable sex differences in anthropometric measurements: the average height, weight, and BMI in males were all higher than those in females. The mean length of hospital stay was 6.2 days, with females showing a slightly longer average duration than males [6.5 vs. 5.6 days].

The most common reason for hospitalization was jaw deformity [28.6%], accounting for nearly one-third of all cases. In such cases, patients usually undergo plate removal surgery six months to one year after initial orthognathic surgery. This procedure, classified as jaw deformity [plate removal], represented 14.6% of all admissions. Other common reasons for admission included tooth extraction [21.5%] and cysts [21.0%], with these three diagnoses together comprising approximately 70% of all cases. A sex-based analysis revealed that jaw deformities were more frequent in females [33.6%], while cysts were more prevalent in males [31.7%]. Less common admission reasons included inflammatory diseases [4.0%], benign tumors [3.8%], malignant tumors [1.6%], mucosal diseases [1.5%], and other causes such as trauma or foreign bodies [3.3%]. A total of 9 patients [1.6% of the cohort] were identified as being at nutritional risk, including 7 females and 2 males.

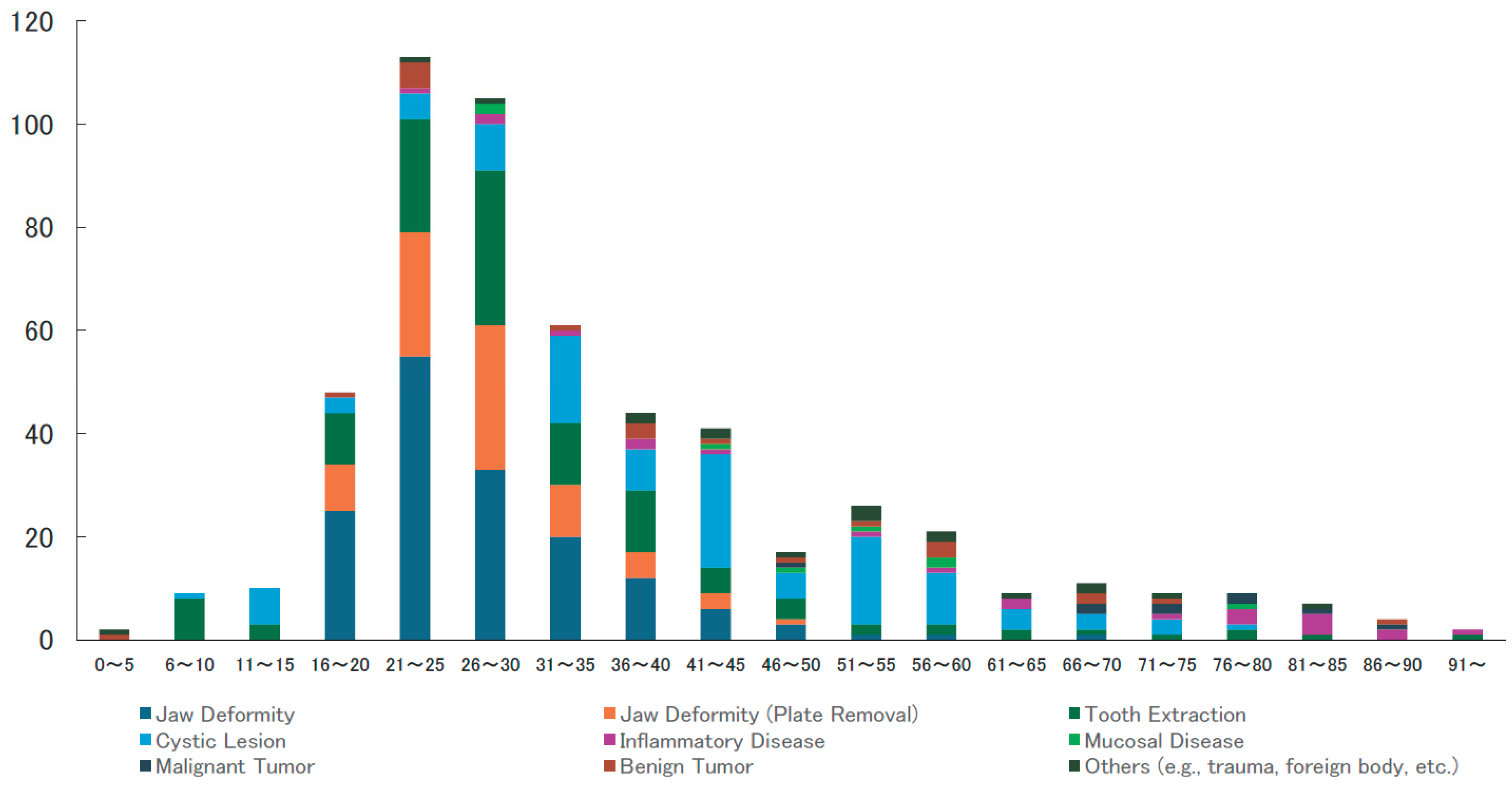

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of disease categories across different age groups. Jaw deformities and related procedures [e.g., plate removal] were predominantly observed in younger patients, particularly those in their late teens to twenties. In contrast, conditions such as cysts, inflammatory diseases, malignant tumors, and medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw [MRONJ] were more frequently found in older adults, indicating a clear age-related trend in disease prevalence.

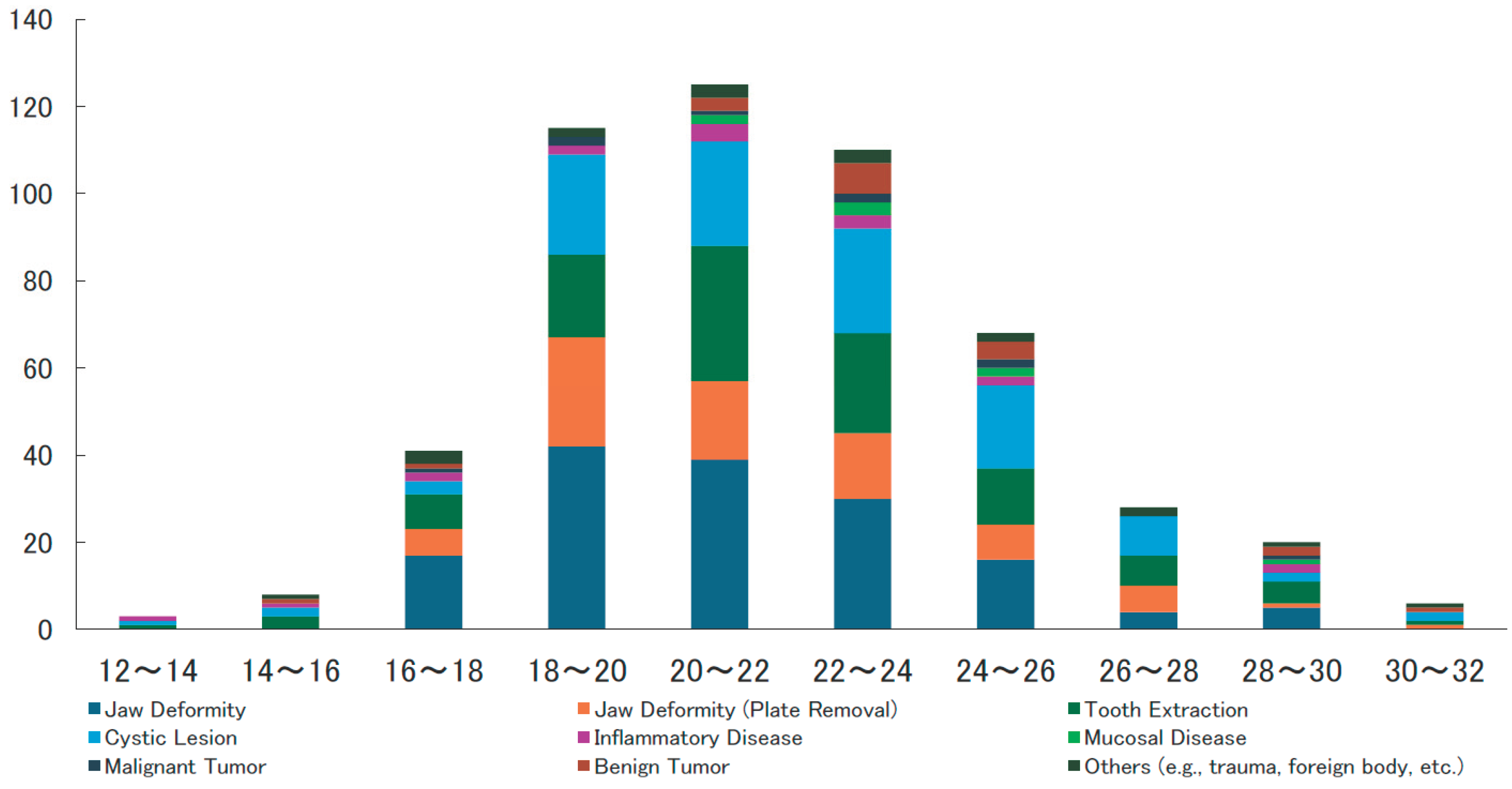

Figure 2 shows the relationship between BMI distribution and reason for hospitalization. While most patients had BMIs within the normal range [18.5–25.0], a number of patients exhibited either significantly low or high BMIs. In particular, underweight status [BMI < 18] was observed among older patients with severe conditions such as malignant tumors or osteomyelitis, suggesting a potential association with nutritional risk.

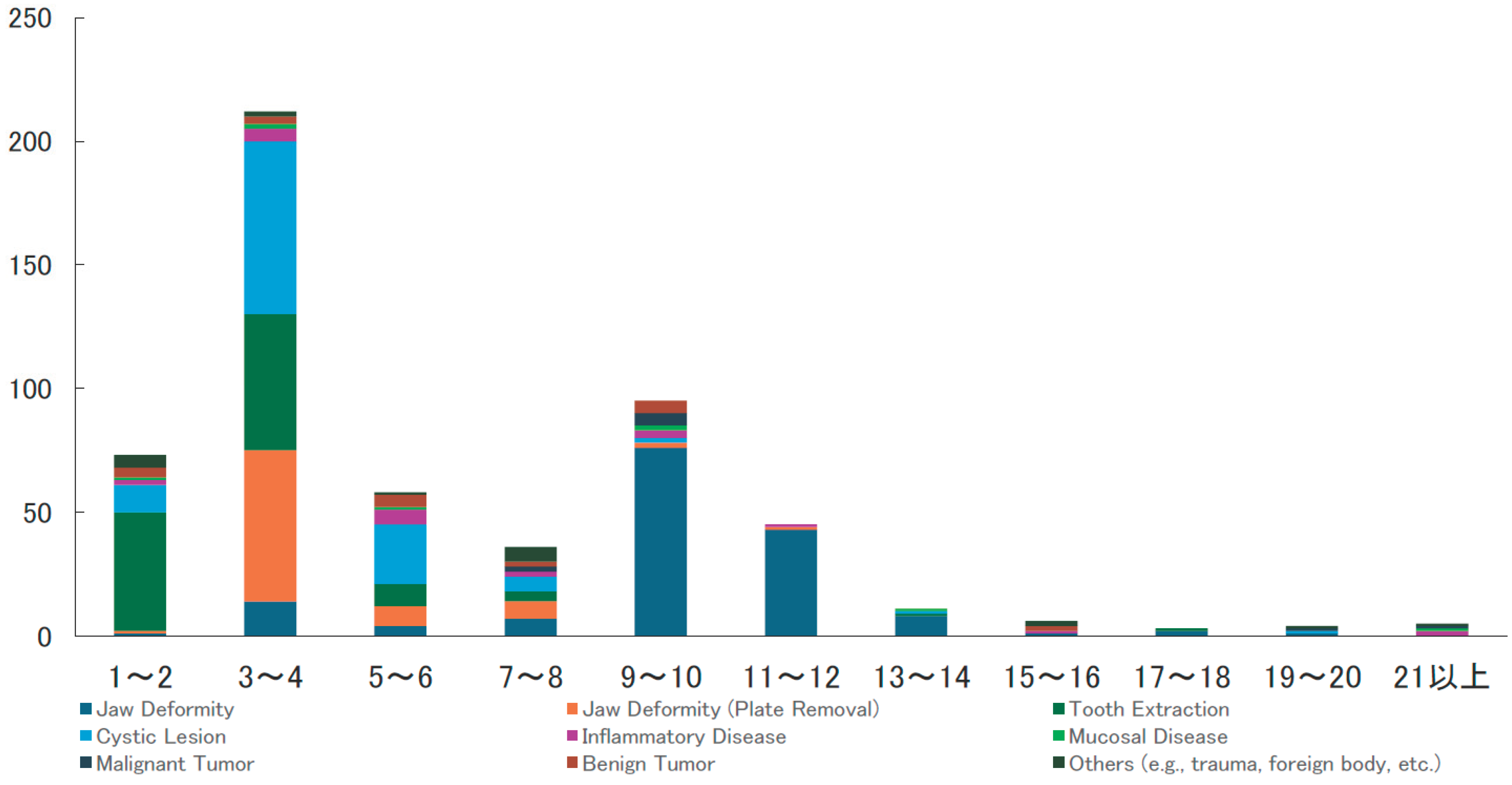

Figure 3 presents the distribution of hospital stay duration in relation to disease categories. Length of stay ranged from 1–2 days to over 21 days. The most frequent duration was 5–6 days, followed by 3–4 and 7–8 days, indicating that short to mid-term hospitalization was common. However, prolonged stays [≥10 days, and occasionally over 20 days] were seen in more severe cases, such as those involving osteonecrosis, osteomyelitis. Short stays were typical for cases involving tooth extraction and mucosal lesions.

Table 2 summarizes the clinical characteristics of patients with an NRS-2002 score of ≥3, indicative of nutritional risk. As prescribed previously, a total of 9 patients were identified as being at nutritional risk, including 7 females and 2 males. These patients tended to be older female adults with low BMI and serious conditions. Specific examples include a 91-year-old female with MRONJ who had a hospital stay of 63 days, and an 85-year-old female with osteomyelitis of mandibule and a BMI of 12.8.

Most of these patients had BMIs below 18.5 or were markedly underweight, and their hospital stays tended to be prolonged. Among them, only 3 of the 9 patients received oral nutritional supplements [ONS] during hospitalization. Furthermore, only 4 patients were formally diagnosed with malnutrition based on the GLIM criteria, despite having an NRS-2002 score indicating nutritional risk.

Discussion

This retrospective study examined the implementation and clinical relevance of nutritional risk screening using the Nutritional Risk Screening 2002 [NRS-2002] in 548 patients admitted to the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. The study population had a relatively young mean age of 35 years, with most admissions involving moderately invasive procedures such as orthognathic surgery and subsequent plate removal.

The characteristics of hospitalized patients in oral and maxillofacial surgery, as presented in

Table 1, revealed significant sex differences in anthropometric measurements such as height, weight, and BMI. However, there was no significant difference in age, indicating that both male and female patients belonged to comparable age groups. Length of hospital stay was significantly longer in females than in males [6.5 days vs. 5.6 days, p = 0.026]. This may be due to the higher proportion of orthognathic surgery cases among female patients, as well as potential sex-based differences in postoperative recovery related to pain and nutritional intake.

Sex-based differences in reasons for admission were also noted. Orthognathic surgery [including plate removal] was more common in female patients, suggesting a trend toward elective procedures for aesthetic or functional improvement among women. Conversely, cystic lesions were significantly more frequent in male patients than in females [31.7% vs. 13.6%, p < 0.001]. Previous reports have similarly documented a male predominance in odontogenic keratocysts [

10,

11,

12].

The higher prevalence of cystic lesions in males may be explained by behavioral and biological factors: men are less likely to seek timely dental care, leading to progression of caries and periodontal disease into chronic inflammatory lesions such as radicular cysts. Moreover, higher rates of smoking and alcohol consumption among men may impair tissue healing and promote chronic inflammation. Hormonal and immunological differences between sexes may also play a contributory role. For other conditions [e.g., tumors and inflammatory diseases], no significant sex differences were observed.

The proportion of patients with nutritional risk [NRS-2002 score ≥ 3] was very low overall [1.6%, 9/548], with no statistically significant sex difference [0.9% in men vs. 2.2% in women, p = 0.321]. This likely reflects the relatively young patient population undergoing oral surgery at our institution, in whom malnutrition is uncommon.

Figure 1 illustrates the age- and disease-specific distribution of patients. In younger age groups [10s to 30s], surgical interventions for jaw deformities [orthognathic surgery] are predominant. In middle-aged individuals [40s to 60s], the frequency of conditions such as tooth extraction, cysts, and inflammatory diseases increases, suggesting that treatment in this group is largely related to chronic conditions and dental caries or periodontal disease.In older adults [aged 70 and above], malignant tumors, mucosal diseases, and benign tumors become more prominent, indicating a higher proportion of neoplastic lesions associated with aging. “Others” [including trauma and foreign bodies] are observed across all age groups, implying that acute injuries and swallowing-related issues occur regardless of age.

Figure 2 presents the distribution of diseases by body mass index [BMI]. The majority of cases are clustered within the normal BMI range [20–24], suggesting that most patients are nutritionally stable. Jaw deformities and plate removal procedures are more frequent in the BMI 18–24 range, reflecting their prevalence among young individuals with slender to normal body types.Although fewer cases are observed in the high BMI category [≥30], conditions such as inflammation, cysts, and tooth extractions are still present, potentially indicating obesity as a risk factor for infections and chronic diseases.

In contrast, among individuals with low BMI [≤16], a relatively higher proportion of malignant tumors and mucosal diseases is observed, suggesting a possible association with malnutrition or cachexia.

Figure 3 shows the distribution of diseases by length of hospital stay. Short-term admissions [1–4 days] are the most common and are primarily associated with relatively minor procedures such as tooth extractions, cyst removal, and treatment of inflammatory conditions. Admissions lasting 5–10 days are more frequently associated with mucosal diseases, benign tumors, and plate removal, which may require more invasive or ongoing management. Long-term hospitalizations [over 10 days] are predominantly associated with malignant tumors and jaw deformities, reflecting the complexity of surgeries requiring general anesthesia and postoperative care. The presence of “Other” conditions in this group also suggests prolonged hospitalization due to trauma or complications.

Table 2 details the nine patients with nutritional risk [NRS-2002 score ≥ 3], consisting of two men and seven women. Of these, seven patients were aged 73 or older and tended to have lower BMIs. According to the GLIM criteria, 4 of the 9 cases [44%] were classified as malnourished. Oral nutritional supplements [ONS] were used in selected cases, particularly in patients with inadequate food intake, with a regimen of three daily doses [200 kcal each]. Dietary modifications were made progressively based on patient status [e.g., rice gruel to soft rice; minced diet to mousse]. Additionally, flavor-enhancing foods such as umeboshi paste and seaweed preserves were used to stimulate appetite. In some cases, this approach yielded notable results, such as an 85-year-old woman who gained 2.6 kg during her hospital stay.

In patients with extended hospitalizations [e.g., a 91-year-old woman hospitalized for 63 days], intensive nutritional strategies were implemented to support postoperative recovery. Although the majority of our oral surgery inpatients were younger individuals with low nutritional risk, high-risk patients received individualized and comprehensive nutritional management. Our institution provided high-quality nutritional support, including active use of ONS, individualized food textures, and consideration of patient preferences. Nutritional assessment based on the GLIM criteria was also integrated.

This study focused on perioperative nutritional care during hospitalization, without evaluating post-discharge outcomes or long-term nutritional status. Future studies should investigate postoperative weight changes and readmission rates to assess the sustainability and long-term impact of nutritional interventions.

As a result, only 1.6% of patients were identified as being at nutritional risk based on an NRS-2002 score of ≥3.

However, the nine patients identified as being at nutritional risk shared key characteristics: advanced age, low BMI, and severe underlying diseases such as medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw [MRONJ], or osteomyelitis of mandible. These patients also tended to have prolonged hospital stays. Among them, four were diagnosed with malnutrition according to the GLIM criteria, and three received oral nutritional supplements [ONS]. These findings suggest that NRS-2002 may be a valuable tool for the early identification of high-risk patients, even in surgical disciplines such as oral and maxillofacial surgery.

Our results align with previous studies conducted in other surgical fields [

5,

7,

8], supporting the utility of NRS-2002 as a first-line screening tool. Reports on its application in oral surgery remain scarce, and this study helps address that gap by providing new insights into its clinical application in this setting.

The observed age- and disease-specific trends were also noteworthy. Jaw deformities were more common among younger women, while cysts and malignant tumors were more frequently observed in older men. These distributions underscore the need for age- and disease-specific nutritional assessment and intervention strategies. Indeed, previous research has shown that hospitalized elderly patients diagnosed with malnutrition have a median survival time of just six months [

3], highlighting the importance of early nutritional interventions to improve outcomes.

A 2020 Japanese study [

13] reported that, among university hospital inpatients, 42% were at nutritional risk and 26% were malnourished. In contrast, the lower prevalence in our study likely reflects the younger and less critically disease population studied, suggesting a potential underestimation of nutritional risk frequency in this context. In older hospitalized patients, nutritional status is a prognostic factor that impacts not only clinical outcomes but also overall survival, independent of the underlying disease. Without adequate nutritional intake, patients may experience further deterioration in nutritional status during hospitalization. Nutritional care should, therefore, be integrated into disease treatment from the outset.

Recent advances in nutritional support emphasize individualized interventions, as demonstrated in the Effect of early nutritional support on Frailty, Functional Outcomes, and Recovery of malnourished medical inpatients Trial [EFFORT] [

14], where a three-step protocol—screening, assessment, and regular intervention—was implemented by multidisciplinary teams from the time of admission. The study showed significant reductions in mortality and complications, with 90% of interventions involving dietary enhancement and ONS, rather than artificial nutrition. These findings highlight the importance of “natural” oral nutritional support in clinical practice.

In the field of oral surgery, perioperative nutritional management should be based not on preoperative serum albumin alone, but on comprehensive evaluations such as those proposed by the GLIM criteria. Preoperative hypoalbuminemia and prolonged surgical duration in invasive oral surgical procedures have been reported as significant risk factors for postoperative oral complications [

15]. However, in the present study, nutritional screening using standardized tools was not performed. In Japan, serum albumin has historically been misused as a marker for malnutrition, but recent international guidelines [

16,

17,

18] no longer support this approach. Instead, structured and quantitative nutritional assessment should become the new standard.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, comparisons with other nutritional screening tools such as MUST or SGA were not performed. Second, the small number of patients with NRS ≥ 3 raises the possibility of underestimating or overlooking malnutrition; additional screening methods may be needed. Third, the relatively low proportion of older adults limits the applicability of our findings to frail elderly populations. Moreover, this study was conducted at a single institution over a 7-month period [August 2024 to February 2025], which may limit generalizability due to regional and seasonal factors. Nutritional interventions such as ONS were implemented in only a subset of patients, making it difficult to systematically evaluate their efficacy. With only 1.6% of patients scoring ≥ 3, statistical power was limited, and multivariate analyses were not feasible. Compared with other institutions serving older or multimorbid populations, potential selection bias should be considered.

This study clarified the applicability of NRS-2002 in the context of oral and maxillofacial surgery and revealed its associations with disease type, age, BMI, and clinical outcomes. While the overall prevalence of nutritional risk was low due to the young, generally healthy patient population, nutritional risk was notably concentrated among elderly patients with low BMI and severe diseases, indicating a high need for targeted intervention. Our findings suggest that NRS-2002 is a valid screening tool even in the perioperative management of oral surgical patients. They also support the importance of establishing an integrated workflow—from screening at admission, to assessment, to intervention—as part of routine clinical care.

Future directions include, expanding analysis to multicenter settings including older and more complex cases, evaluating the relationship between nutritional interventions and treatment outcomes, and standardizing NST involvement. Such steps will contribute to the development of a comprehensive coordinated nutritional support system to improve perioperative outcomes in oral and maxillofacial surgical patients.