1. Introduction

Japan is experiencing a rapid increase in its aging population, with individuals aged 65 years and older now representing more than 21% of the total population, and this proportion is expected to continue increasing. In parallel with this demographic shift, the number of older inpatients in acute care hospitals has also been increasing, particularly among those aged 75 years and older [

1].

Older adults admitted to acute care hospitals are prone to decreased swallowing function due to multiple factors. Impaired swallowing not only influences the length of hospital stay but is also linked to prognosis in older adults. Several studies have examined the effects of nutritional status, oral function, and swallowing ability on dietary form in older adults. For example, Nakamori et al. [

2] reported that oral function—particularly tongue pressure—is closely associated with dietary form in older adults. Likewise, Arakawa et al. [

3] studied older patients with stroke in a convalescent rehabilitation ward and found a potential association between the eating-related item of the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) and nutritional status assessed with the Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI), suggesting that dietary form may influence independence in activities of daily living.

However, most previous studies did not evaluate dietary form in sufficient detail. Therefore, in this study, we assessed older adults (≥74 years) admitted to an acute care hospital. A swallowing specialist performed both videoendoscopic evaluation of swallowing (VE) and videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VF) for each patient to determine the appropriate dietary form. In addition, we examined the relationships among dietary form, oral health assessed with the Japanese version of the Oral Health Assessment Tool (OHAT-J) [

4], and functional independence measured with the FIM.

We hypothesized that poor oral health and low functional independence would be significantly associated with restricted dietary forms among older inpatients in acute care hospitals.

2. Materials and Methods

Participants

This study included 74 older adults (30 men and 44 women) admitted to the Department of Geriatric Medicine at Kanazawa Medical University Hospital between April 2023 and June 2025. The primary admission diagnoses were pneumonia in 15 patients (including 7 with aspiration pneumonia), cerebral infarction in 11, heart failure in 5, pyelonephritis in 4, liver dysfunction in 2, and other conditions in 34, such as rhabdomyolysis, dehydration, cholecystitis, urinary tract infection, respiratory failure, sepsis, and bacteremia.

Methods

1) Assessment of Oral Health

Oral health was evaluated using the Japanese version of the Oral Health Assessment Tool (OHAT-J), developed to screen for oral problems in older adults requiring care. The OHAT-J includes eight items, each scored on a three-point scale (0 = healthy, 1 = mild changes, 2 = severe problems). The total OHAT-J score, median values, and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for each item were calculated.

2) Evaluation of Dietary Form

Dietary form was determined by a swallowing specialist after an initial screening interview, followed by videoendoscopic evaluation of swallowing (VE) and videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VF). Dietary form was scored as follows:0 = no oral intake,

3) Assessment of Functional Independence

Functional independence was assessed using the FIM [

3], a tool widely applied in rehabilitation medicine. FIM scores were extracted from electronic medical records and were evaluated within 2 days of hospital admission. The FIM has a maximum total score of 126 points and includes two domains:

Motor Items (91 points total, 13 items): self-care (eating, grooming, etc.), sphincter control, transfers, and locomotion.

Cognitive Items (35 points total, 5 items): communication and social cognition.

Each item was scored on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (total assistance) to 7 (complete independence). Based on total FIM scores, patients were classified into four groups:

FIM-A group (mild impairment): 110–126 points

FIM-B group (moderate impairment): 80–109 points

FIM-C group (severe impairment): 50–79 points

FIM-D group (very severe impairment): 18–49 points.

Statistical Analysis

For multivariate analysis, dietary form was dichotomized into two categories: the modified diet group (scores 0–5, including no oral intake through fully mashed rice diets) and the regular diet group (scores 6–7, including soft rice and regular diets). Logistic regression was performed with this binary outcome as the dependent variable. To test whether other clinical and oral variables differed across FIM stages, the Kruskal–Wallis test was applied to continuous variables, including age, OHAT score, dietary form score, serum albumin, and number of remaining teeth. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Differences among the three FIM groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance. Relationships among OHAT-J total scores, FIM scores, age, and serum albumin (Alb) levels were examined with Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Logistic regression with the stepwise method was conducted, with dietary form as the dependent variable and other related factors as independent variables. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP Student Edition 18 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA), and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

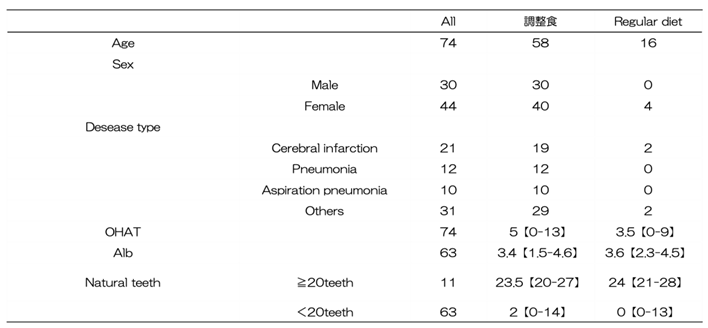

Table 1 presents the overall characteristics of the study participants. The mean age was 87.1 ± 6.0 years. The OHAT total score was relatively high at 5.1.

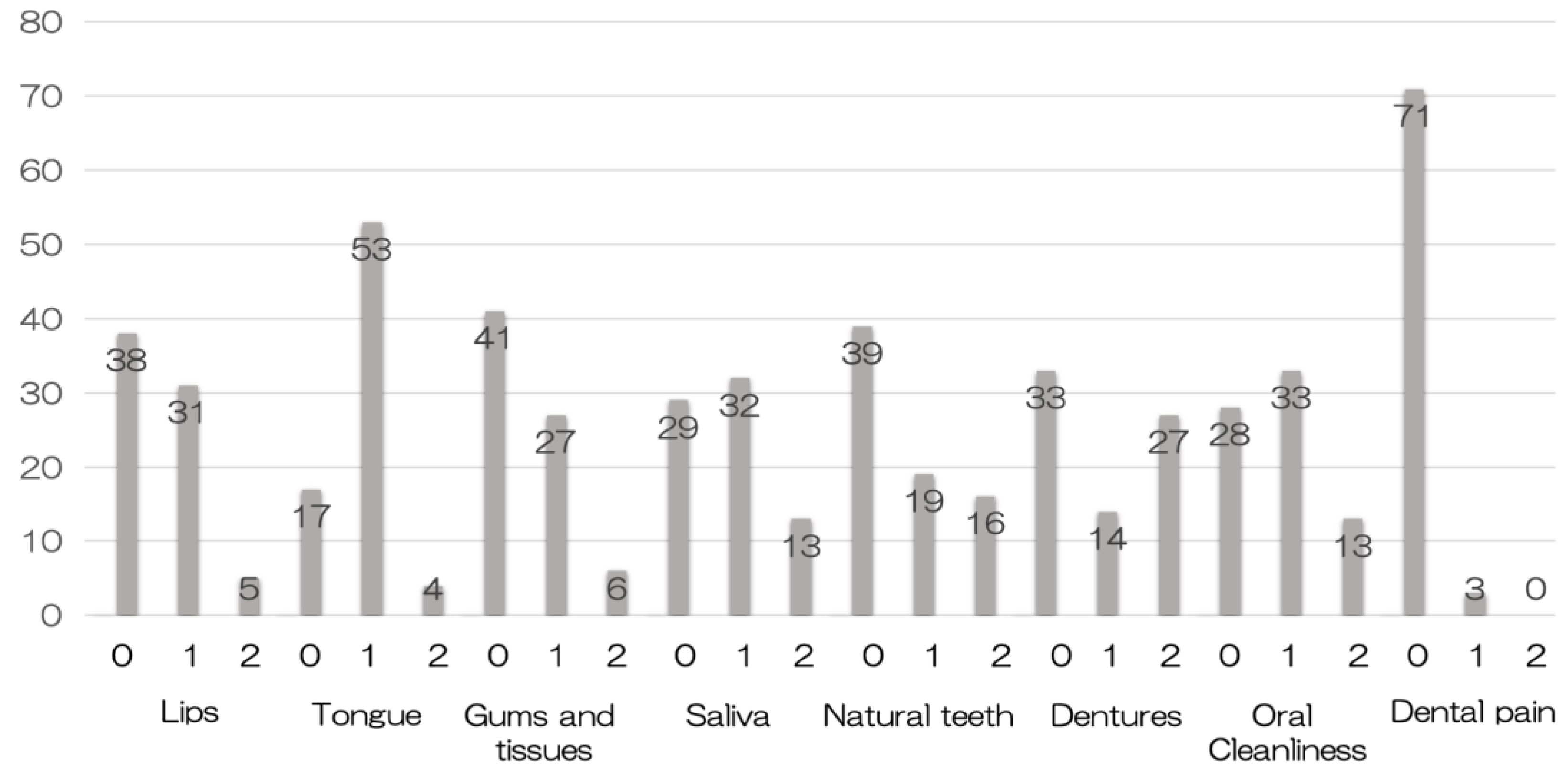

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of OHAT subitems. More patients were classified as having “oral changes” or “unhealthy” in the categories of tongue, saliva, and oral cleanliness than in other items (

Figure 1).

Table 1.

Participants characteristics by meal type.

Table 1.

Participants characteristics by meal type.

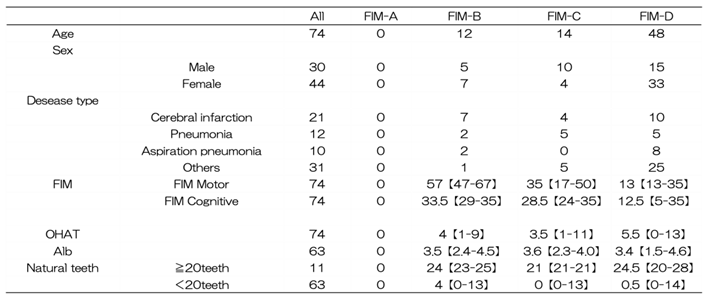

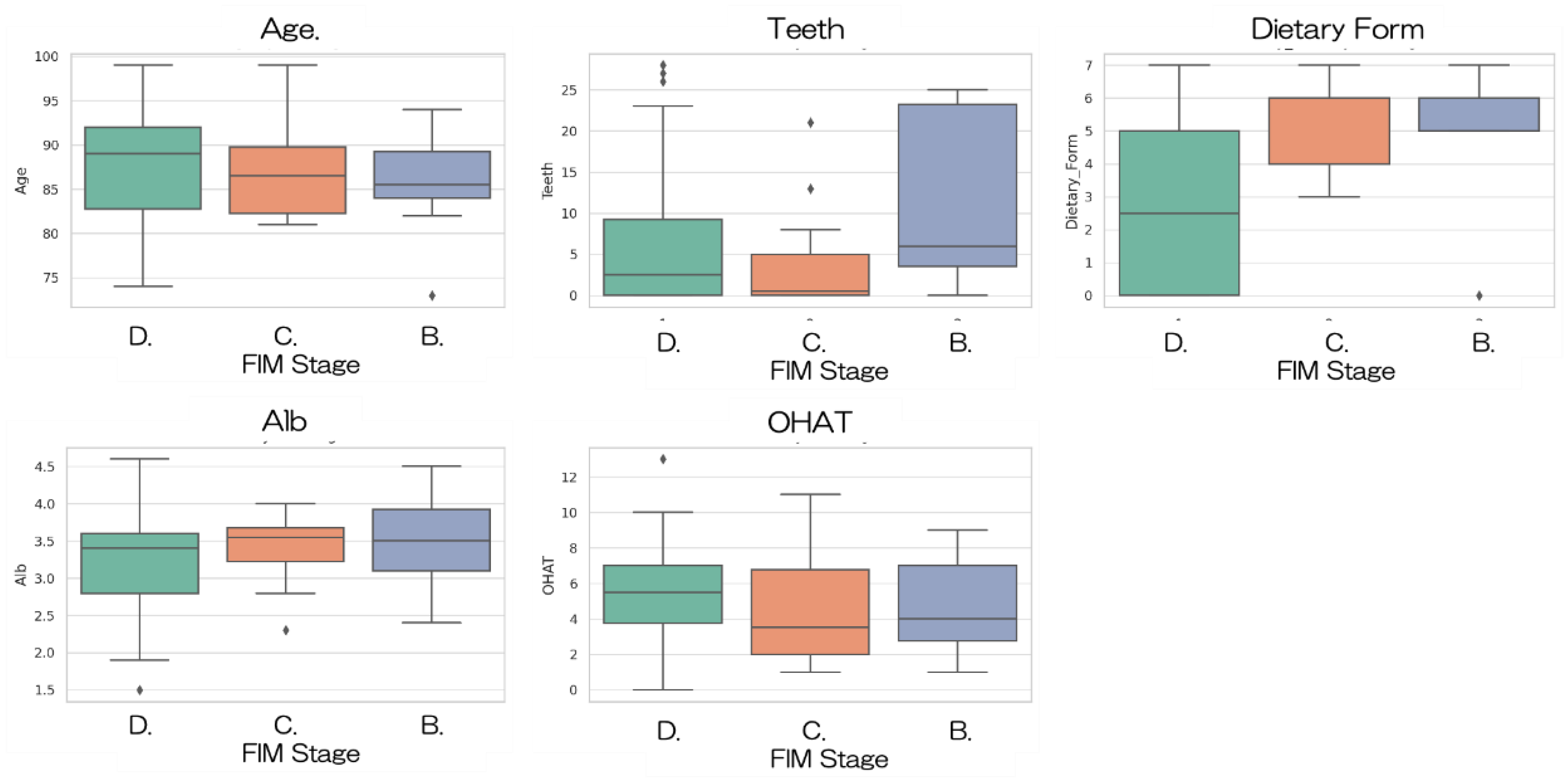

When stratified by FIM stage, significant differences were observed in dietary form (H = 18.20, p < 0.001). Patients with higher FIM stages were more likely to receive regular diets, whereas those with lower stages tended to require texture-modified diets (

Figure 2). No significant differences were observed in age (H = 1.59, p = 0.45), OHAT scores (H = 3.24, p = 0.20), serum albumin levels (H = 2.27, p = 0.32), or number of remaining teeth (H = 4.50, p = 0.11) among the FIM stages (Table2).

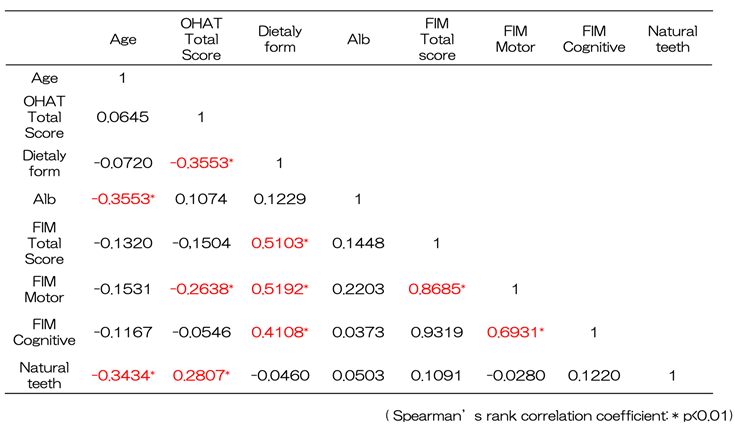

Table 3 presents the correlation analysis for FIM motor, FIM cognitive, and FIM total scores. All showed significant negative correlations with age and significant positive correlations with OHAT scores.

Table 2.

Participants characteristics by FIM type.

Table 2.

Participants characteristics by FIM type.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of independence and oral health and general health status.

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of independence and oral health and general health status.

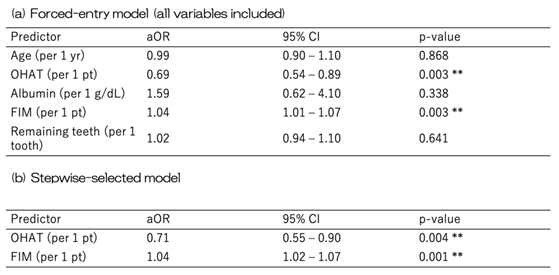

When dietary form was dichotomized into modified (0–5) and regular (6–7) groups, the results were consistent with the main analysis. Higher OHAT scores were significantly associated with a lower likelihood of being in the regular diet group (adjusted OR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.55–0.89; p = 0.004), while higher FIM scores were independently associated with a greater likelihood of being in the regular diet group (adjusted OR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.02–1.08; p = 0.002). Age, serum albumin, and number of remaining teeth were not significant predictors. In the forced-entry multivariable logistic regression model, higher OHAT scores were significantly associated with a lower likelihood of receiving a regular/soft diet (adjusted OR per 1-point increase, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.54–0.89; p = 0.003), whereas higher FIM scores were independently associated with a greater likelihood of a regular/soft diet (adjusted OR per 1-point increase, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01–1.07; p = 0.003). Age, serum albumin, and number of remaining teeth were again not significant predictors (

Table 4 (a)).

In the stepwise regression model, only OHAT and FIM remained significant predictors. Higher OHAT scores predicted a reduced likelihood of a regular/soft diet (adjusted OR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.55–0.90; p = 0.004), whereas higher FIM scores were associated with an increased likelihood (adjusted OR, 1.04; 95% CI, 1.02–1.07; p = 0.001) (

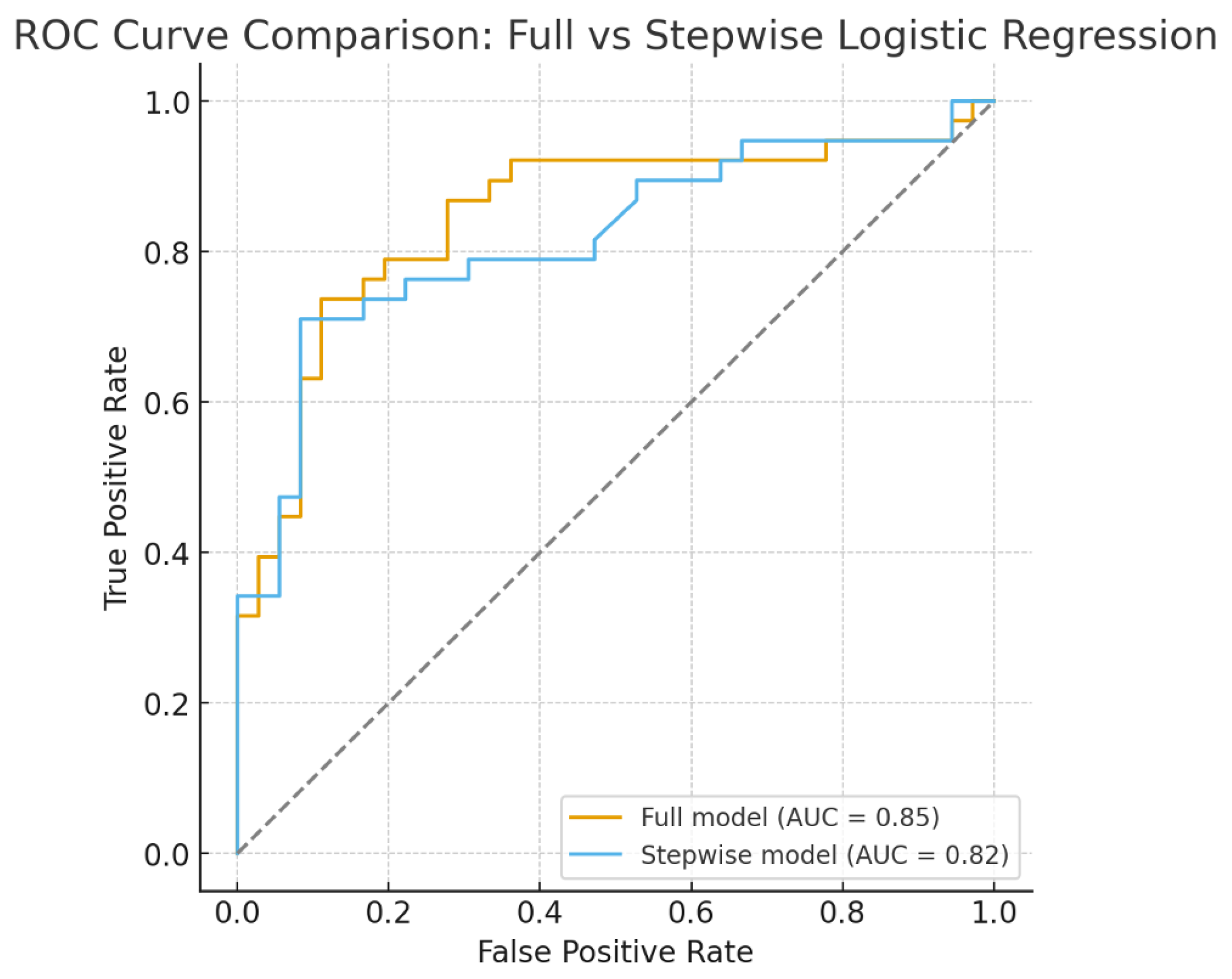

Table 4 (b)). To assess the discriminative ability of the models, ROC curve analysis was conducted. The full model, which included all variables, demonstrated good discrimination with an AUC of 0.85. The stepwise-selected model, which retained only OHAT and FIM, also showed good discrimination with an AUC of 0.82 (

Figure 3). These findings suggest that both models are clinically useful, although the simplified model may be more practical for routine clinical application.

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression for the likelihood of receiving a regular/soft diet (vs. fasting/dysphagia diet).

Table 4.

Multivariable logistic regression for the likelihood of receiving a regular/soft diet (vs. fasting/dysphagia diet).

4. Discussion

The OHAT was originally developed by Chalmers et al. in Australia as a structured screening instrument for evaluating oral health in institutionalized older adults, particularly those with cognitive impairment or limited ability to self-report oral conditions [

5]. The OHAT assesses eight domains: lips, tongue, gums, saliva, natural teeth, dentures, oral cleanliness, and dental pain. It provides a practical and reliable method for identifying oral problems in populations where access to dental professionals is limited or where daily monitoring by caregivers is required [

5,

6].

The Japanese version of the OHAT (OHAT-J) was subsequently translated and validated to ensure applicability in Japanese healthcare and long-term care contexts. The OHAT-J has demonstrated both reliability and validity for assessing oral health among older adults, including those in acute care hospitals and nursing homes [

4]. The availability of the OHAT-J enables medical and dental professionals, as well as non-dental healthcare workers, to evaluate oral health systematically and implement timely interventions to improve oral function, nutritional intake, and overall quality of life.

In hospitalized older adults, the OHAT-J is a valuable tool not only for screening but also for linking oral health status with broader clinical outcomes, such as dietary form, functional independence, and prognosis. Because impaired oral health may exacerbate swallowing difficulties and nutritional deficits, its integration into comprehensive geriatric assessment is of considerable clinical importance [

4].

The FIM is widely recognized as a reliable and valid tool for assessing independence in activities of daily living (ADLs) among hospitalized patients, including the older patients [

7]. The FIM provides a multidimensional evaluation of motor and cognitive domains, allowing clinicians to capture a comprehensive picture of functional status and prognosis [

8,

9]. Previous studies have demonstrated that lower FIM scores are associated with poorer nutritional status, longer hospital stays, and higher readmission rates, underscoring their prognostic value in geriatric and rehabilitative care [

10].

In the context of dysphagia and oral health, the eating-related items of the FIM have been shown to correlate with both oral function and dietary form [

3], suggesting that oral health impairment directly influences functional independence. Furthermore, improvements in swallowing function or nutritional management have been reported to result in parallel improvements in FIM scores, indicating that targeted interventions in oral and nutritional care may enhance overall independence [

3].

Taken together, integration of the FIM into multidisciplinary assessment provides not only an objective measure of patient outcomes but also a tool for evaluating the impact of interventions in oral health, nutrition, and rehabilitation medicine. This reinforces the importance of incorporating the FIM into clinical decision-making and research involving older inpatients with complex medical needs [

11,

12,

13].

Several studies have examined the relationship between nutritional status and functional independence in older patients with stroke admitted to convalescent rehabilitation wards. Kokura et al. demonstrated that a low GNRI on admission independently predicted smaller improvements in FIM scores, suggesting that nutritional risk negatively affects functional recovery [

11]. Similarly, Nii et al. reported that improvements in nutritional status and energy intake are associated with greater ADL recovery, as measured by FIM [

12]. Kishimoto et al. also showed that early weight maintenance or gain during rehabilitation was significantly correlated with improvements in Motor-FIM scores [

14]. Furthermore, Shimizu et al. found that lower dietary texture levels were associated with higher prevalence of malnutrition and sarcopenia in patients with stroke [

15], while Sawa et al. demonstrated that upgrading dietary texture levels contributed to improved nutritional status, ADL recovery, and discharge to home [

13]. Collectively, these findings indicate that both nutritional status and dietary form are important determinants of recovery of independence in ADLs.

This study demonstrated that oral health status, assessed with the OHAT-J, and functional independence, measured with the FIM, were significant predictors of dietary form among older inpatients in an acute care hospital. Patients with poorer oral health were more likely to require modified diets, whereas those with higher functional independence were more likely to tolerate a soft or regular diet. These findings emphasize the interrelationship between oral conditions and systemic functional capacity in guiding nutritional management for hospitalized older adults.

Our findings are consistent with previous reports showing that oral dysfunction, including impaired tongue pressure and poor oral hygiene, contributes to dysphagia and the need for texture-modified diets in older adults. In addition, functional independence has been reported to be associated with both nutritional status and swallowing ability, particularly in post-stroke patients, supporting the validity of our results. Notably, serum albumin and the number of remaining teeth were not independent predictors in our multivariate analyses, suggesting that functional capacity and oral environment may outweigh these traditional markers in determining dietary form during acute hospitalization.

The clinical implications of this study are substantial. The combination of OHAT-J and FIM provides a simple and reliable framework for predicting dietary form, enabling healthcare professionals to promptly identify patients at risk of aspiration or malnutrition. Early recognition and intervention may reduce complications, shorten hospital stays, and improve outcomes. Furthermore, this approach underscores the importance of collaboration between dental and rehabilitation teams in acute care settings.

Certain limitations should be acknowledged. First, this was a single-center study with a relatively small sample size, which may limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inferences. Longitudinal studies are needed to clarify whether improvements in oral health and functional independence directly lead to recovery of dietary form. Third, the study did not include detailed measurements of swallowing physiology, such as tongue pressure or pharyngeal residue, which might provide additional insights. Despite these limitations, the discriminative performance of our models was robust, supporting their clinical utility.

Future perspectives should also be addressed. Prospective studies are warranted to examine whether interventions, such as oral care and swallowing rehabilitation, can improve OHAT scores and FIM performance, thereby enhancing dietary form and preventing aspiration pneumonia. Incorporating physiological measures of swallowing, including tongue pressure and swallowing reflex latency, would provide further insights into the mechanisms linking oral and swallowing function to dietary form. It is also important to investigate how dietary form influences long-term outcomes, such as readmission rates, length of hospital stay, and overall prognosis after discharge. These findings underscore the significance of comprehensive nutritional and dysphagia management through interdisciplinary collaboration from the acute phase. Furthermore, international comparative studies may help clarify the unique characteristics of elderly care in Japan and contribute to global discussions on geriatric nutrition and swallowing management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.N. and M.O.; Methodology, H.N. and M.O.; Validation, H.N.; Formal Analysis, K.O. and T.M.; Investigation, O.K., T.M.; Resources, H.N.; Data Curation, T.M., E.M., Y.S., O.K., and Y.Y.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, K.O.; Writing – Review & Editing, H.N. and M.O.; Visualization, H.N.; Supervision, S.W., T.H. and M.O.; Project Administration, H.N. and O.K.; Funding Acquisition, M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.