1. Introduction

Chronic low back pain is a leading cause of disability (

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/low-back-pain), and the lumbar facet (zygapophyseal) joints are a well-recognized source of pain in a significant subset of patients. Studies estimate that facet joint degeneration contributes to approximately 15–45% of axial low back pain cases. These small posterior spinal joints can elicit both localized and referred pain, but accurately diagnosing facet-mediated pain is challenging without invasive tests. Typically, physicians rely on medial branch nerve blocks (MBB)(injections of local anaesthetic near the facet joint nerve supply) to confirm the diagnosis, since clinical features and radiological imaging (scans, i.e., computed tomography – CT or magnetic resonance imaging – MRI) are often insufficient [

1]. Each facet joint is innervated by two tiny medial branch nerves, and standard practice is to perform diagnostic blocks using local anaesthetics to improve diagnostic accuracy [

2]. To confirm the diagnosis after MBB, patient’s pain relief is expected to last for the duration of local anaesthetics used for the block. This process underscores a major limitation in current care, diagnostic accuracy for facet pain hinges on invasive procedures that carry inconvenience and risk particularly for cervical and thoracic levels. A variety of treatment modalities are employed for facet joint arthritis-related back pain, with the goals of providing pain relief and improving function. These include conservative measures (analgesic medications, physiotherapy, participation in a pain management programme), corticosteroid injections either into the facet joint or around the medial branch nerves, and neuroablative procedures to disrupt the pain-transmitting nerves [

3]. The most common neuroablative technique is radiofrequency (RF) medial branch neurotomy (also called RF ablation or rhizotomy), which uses thermal energy to coagulate the nerve. Other approaches have been explored, such as cryoablation (freezing the nerve), pulsed RF, laser ablation, and variations of RF technology like cooled RF probes or trident probes that create larger lesions. These interventions aim to denervate the facet joint and thereby alleviate pain. However, the outcomes of such treatments have been variable where systematic reviews have reported conflicting efficacy results across studies [

4].

In general, medial branch neurotomy is considered effective in the short term, but pain often recurs over time as nerves regenerate [

5]. Indeed, evidence-based guidelines have characterized RF facet neurotomy as providing strong evidence for short-term relief but only moderate evidence for long-term relief of facet joint pain [

6]. The NICE guidelines recommend RF neurotomy following a successful MBB for lumbar facet joint-mediated low back pain [

7]. However, they do not provide specific recommendations for the use of RF neurotomy in the cervical or thoracic spine. Despite this, RF neurotomy is frequently performed at all spinal levels within NHS clinical practice. Steroid facet injections, on the other hand, tend to yield only transient relief and have not shown clear long-term benefit; recent guidelines do not recommend therapeutic intra-articular facet injections as a definitive treatment. Thus, despite being mainstays of care, these therapies have important limitations [

8]. Key limitations of current treatments include issues of invasiveness, inconsistent durability, side effects, and patient compliance. If the diagnostic blocks fail to provide relief, the patient is denied the neurotomy, often leading to frustration after having undergone invasive tests with no therapeutic benefit. Even when blocks are positive and RF ablation is performed, the procedure involves inserting needles adjacent to the spine under imaging guidance, an invasive step that carries small risks such as bleeding, infection, or nerve irritation, rarely nerve injury and muscle weakness. Many patients experience post-procedural soreness, and some develop localized numbness or dysesthesias in the distribution of the ablated nerve. Furthermore, pain relief from medial branch RF tends to last around 6–12 months in majority of the cases, after which the nerve may regrow and symptoms return. Repeating the procedure is possible, but each cycle adds cost, procedural risk, where the methodological limitation of X-ray-guided RF neurotomy lies in its reliance on anatomical landmarks, specifically the junction between the superior articular process and the transverse process of the target vertebra, for cannula placement, without direct visualization of the medial branch nerve. Furthermore, motor or multifidus muscle stimulation, which serves as a functional confirmation of proximity to the target nerve, may not be elicited consistently across all spinal levels, even when optimal anatomical positioning is achieved. The need for precise, parallel alignment of electrodes to the medial branch nerve for effective radiofrequency neurotomy not only impacts lesion efficacy and outcomes but also underscores diagnostic challenges, as technical variability and patient factors can contribute to false-positive or false-negative block results that may misguide treatment [

9]. All these factors (repeat injections, fluoroscopy exposure, moderate longevity of relief) can negatively impact patient compliance and overall healthcare costs [

5]. There is a clear need for a treatment that is less invasive, more adaptable, more patient-friendly, and provides equal or better pain relief with fewer side effects [

10].

Focused ultrasound has emerged as a promising, non-invasive alternative for treating facet joint arthritis pain. Focused ultrasound (FUS) is a technology that concentrates multiple intersecting beams of ultrasound energy on a precise target deep in the body, causing localized ablation of tissue at the focal point while sparing surrounding structures. In the context of facetogenic back pain, the idea is to direct high-intensity ultrasound to the medial branch nerves (or the peri-capsular tissue) to thermally neurolyse them without any incision or needle insertion. Because the ultrasound can be focused with millimeter accuracy, it can reach the target nerves through soft tissues without damaging overlying skin, muscle, or bone, especially under image guidance. Magnetic Resonance-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) allows real-time visualization of the tissue and temperature monitoring during sonication, ensuring that the energy is delivered to the intended spot at therapeutic levels. The result is a precise ablation of the nerve pathways carrying pain from arthritic facet joints, effectively achieving the same goal as RF neurotomy but completely noninvasively. Early clinical experience with focused ultrasound for back pain is very encouraging. Several pilot studies and clinical trials have been conducted or are underway. A recent systematic review identified multiple preclinical and clinical studies (50 patients across 5 clinical reports) using high-intensity focused ultrasound for facet joint pain; notably, all clinical studies reported significant pain reduction, with average pain scores dropping by several points on 0–10 Numeric Rating Scale at 6 to 12 months after treatment [

11]. Impressively, not a single study reported procedure-related complications or adverse events, highlighting the safety of the approach. One prospective trial of focused ultrasound neurotomy in 30 patients demonstrated pain relief outcomes comparable to conventional RF ablation at 6 months post-FUS, 82.6% of patients were “responders” (≥2-point reduction in pain without increase in medication), and mean pain scores fell from 7.1/10 at baseline to ~3.3/10 [

12]. Patients in that study tolerated the procedure well, with no significant side effects or complications noted during follow-up. In light of these results, focused ultrasound is gaining recognition as a viable treatment for facet joint pain. It has progressed to early-stage clinical trials and even regulatory approvals, e.g., an MR-guided focused ultrasound system (Insightec Exablate) and a portable focused ultrasound device (FUSMobile) have recently been approved in Europe and Canada for the treatment of facetogenic low back pain. Ongoing trials in the US, Germany, Taiwan, and Israel are further investigating its efficacy. In summary, the state-of-the-art in facet joint pain management may soon include focused ultrasound as a non-invasive, precise, and potentially superior modality. This paper presents a novel engineering approach for implementing focused ultrasound therapy with real-time feedback control. We explore how this method can enhance existing treatments by offering high-intensity ablation for targeted tissue destruction and low-intensity neuromodulation to manage recurring conditions as nerves regenerate over time.

2. Methods

2.1. Anatomical Modeling

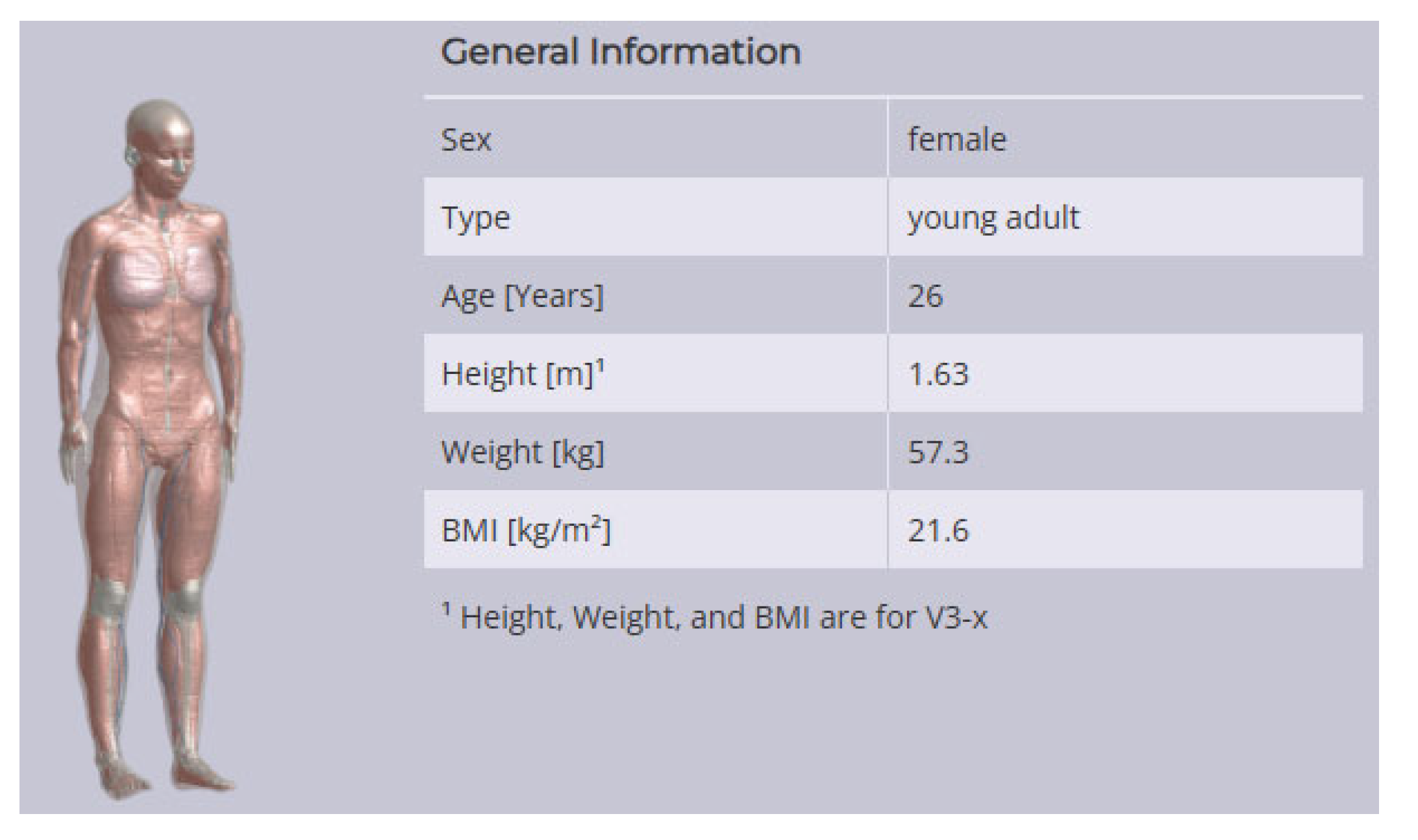

The simulation study utilized the ELLA model from the Virtual Population dataset within the Sim4Life platform (ZMT Zurich MedTech AG), extending the modelling approach developed by Hemangi Dixit in her prior work on magnetic stimulation of the spinal cord [

13]. This high-resolution, anatomically detailed model enabled accurate segmentation and localization of lumbar spinal features, particularly between vertebral levels L3 and S1. This region of interest (ROI) was selected to encompass the lumbar facet joints and the associated medial branch nerves that are key targets in the context of facetogenic back pain – see

Figure 2a. Tissue segmentation for bone, muscle, fat, connective tissue, and peripheral nerves was reviewed using Sim4Life’s Anatomical Scene Viewer. The relevant acoustic and thermal material properties for these tissues were extracted from the Sim4Life database to inform the acoustic-thermal simulation pipeline. Subsequent simulations for in-vitro testing were conducted on a simplified tissue model using the open-source k-Wave MATLAB toolbox (

http://www.k-wave.org/). These k-Wave simulations leveraged the extracted Sim4Life parameters to model ultrasound propagation, tissue heating, and thermal dose accumulation under controlled exposure conditions, providing a reproducible framework for experimental translation – see

Figure 2b.

Figure 1.

ELLA model from the Virtual Population dataset within the Sim4Life platform (ZMT Zurich MedTech AG).

Figure 1.

ELLA model from the Virtual Population dataset within the Sim4Life platform (ZMT Zurich MedTech AG).

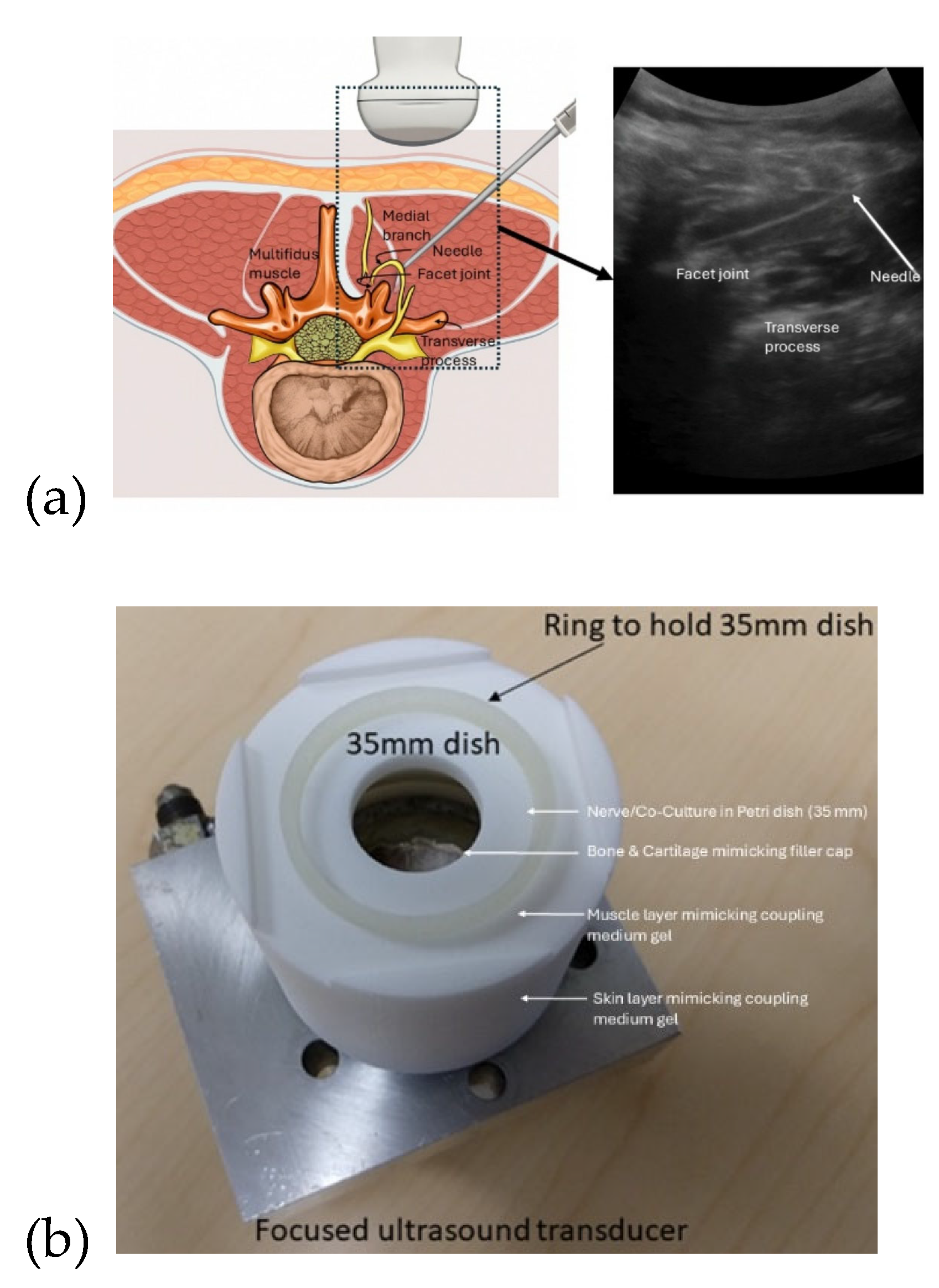

Figure 2.

(a) Ultrasound-guided lumbar facet joint injection offers a radiation-free approach for accurate diagnosis and treatment of facet-mediated low back pain. (b) Custom in-vitro test fixture (designed by Mancheung Cheung, University at Buffalo) enabled bench-top evaluation of a focused ultrasound transducer system (from Engineering Acoustics Incorporated, USA). The setup aligns a 35 mm petri dish at the bowl transducer's 45 mm focus, allowing controlled delivery of ultrasound through coupling gel to tissue-mimicking phantoms. This configuration supports reproducible testing of acoustic effects i.e. pressure, heating, cavitation, and radiation force that are critical for validating neuromodulation models like Neuronal Intramembrane Cavitation Excitation proposed for nerve inhibition.

Figure 2.

(a) Ultrasound-guided lumbar facet joint injection offers a radiation-free approach for accurate diagnosis and treatment of facet-mediated low back pain. (b) Custom in-vitro test fixture (designed by Mancheung Cheung, University at Buffalo) enabled bench-top evaluation of a focused ultrasound transducer system (from Engineering Acoustics Incorporated, USA). The setup aligns a 35 mm petri dish at the bowl transducer's 45 mm focus, allowing controlled delivery of ultrasound through coupling gel to tissue-mimicking phantoms. This configuration supports reproducible testing of acoustic effects i.e. pressure, heating, cavitation, and radiation force that are critical for validating neuromodulation models like Neuronal Intramembrane Cavitation Excitation proposed for nerve inhibition.

2.2. Transducer Configuration and Acoustic Simulation

Figure 2a illustrates ultrasound-guided lumbar facet joint injections as a radiation-free alternative to fluoroscopy for diagnosing and treating facet-mediated low back pain [

14]. This technique targets medial branch nerves (typically L3–L5) using real-time imaging to guide needle placement for intra-articular injections or medial branch blocks. It is feasible and effective, even outside radiology suites, with up to 96% success when joints are visible [

14]. This same ultrasound workflow can also guide non-invasive FUS therapies. Low-intensity FUS enables neuromodulation of medial branch nerves, while high-intensity FUS can ablate facet joint nerve structures for longer-term relief. Ultrasound imaging supports accurate targeting, while simulations (e.g., Sim4Life, k-Wave) optimize safety and precision. For in-vitro validation, a 2D model of a single-element transducer (40 mm aperture, 45 mm focus [

15]) based on the ELLA model was used to represent posterior access to the L4–L5 facet joint region (see

Figure 2b). The acoustic simulation was conducted using the k-Wave MATLAB toolbox (

http://www.k-wave.org/) to model focused ultrasound delivery targeting the facet joint at a 45 mm depth. A single-element bowl-shaped transducer was modelled with a 40 mm aperture and 45 mm radius of curvature, operating at a center frequency of 0.5 MHz. The acoustic medium was defined with properties representative of muscle tissue, including a sound speed of 1580 m/s, density of 1090 kg/m³, and absorption coefficient of 0.5 dB/(MHz

1.1·cm). A continuous wave pressure source with amplitude 0.1 MPa was used to generate the acoustic field for low-intensity focused ultrasound (LIFU) neuromodulation. The computational domain spanned 60 mm axially and 50 mm laterally, with a grid resolution ensuring 10 points per wavelength. The simulation duration was 50 µs, with a Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy (CFL) number of 0.5. The source signal was distributed across the bowl geometry using kWaveArray with bilinear interpolation. A binary sensor mask recorded the resulting pressure field at the midplane. From the simulated pressure amplitudes, the acoustic intensity and heat deposition (Q) were derived by converting the frequency-dependent absorption from decibel to neper units.

2.3. Thermal Modeling for HIFU Ablation

To simulate thermal effects associated with high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), a continuous wave pressure source with amplitude 1 MPa was used to generate the acoustic field, and the acoustic intensity and Q were then used to initialize a thermal simulation via kWaveDiffusion, incorporating thermal properties (conductivity = 0.49 W/m·K, specific heat = 3421 J/kg·K) for temperature rise and dose accumulation (CEM43) under heating (30 s) and cooling (20 s) phases where ultrasound imaging can be performed.

2.4. Neuromodulation Protocol for LIFU

LIFU simulations were conducted to evaluate neuromodulatory potential without inducing thermal damage. The model computed the Mechanical Index (MI) from peak negative pressure as an estimate of cavitation risk. To model the mechanism of pulsed LIFU for peripheral nerve inhibition [

16,

17], we incorporated the Neuronal Intramembrane Cavitation Excitation (NICE) model, which attributes ultrasound-induced neural excitation to the oscillation of nanoscale intramembrane cavities, or "sonophores," within the lipid bilayer [

18]. These oscillations dynamically modulate membrane capacitance, generating displacement currents that can modulate the excitable tissue [

19]. Here, we assumed that nerve effects correlated with the product of the squared acoustic pressure and squared frequency supporting the inertial origin of the neuromodulation [

20].

2.5. Ultrasound Therapy Device Design

To explore focused ultrasound as a therapeutic option for facet joint pain, we developed a proof-of-concept specialized high-power ultrasound driving system with responsive, feedback-controlled operation. The proposed system is based on research undertaken by Demian Didenko at the University of Lincoln, which comprised of a resonant piezoelectric transducer, a custom-designed electronic driving circuit (power amplifier) at an excitation frequency of ~28 kHz, and a feedback controller for real-time optimization of ultrasound delivery. The design emphasis was on maintaining the transducer at its optimal operating point (resonance) automatically, and on monitoring acoustic signals from the load to detect cavitation and adjust power in real time. This concept can ensure that the maximum therapeutic effect (neuromodulation or nerve ablation) is achieved efficiently and safely, despite changes in operating conditions. Key components of the system include a switch-mode power amplifier for driving the transducer and a Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) controller that continually tunes the driving frequency for optimal output.

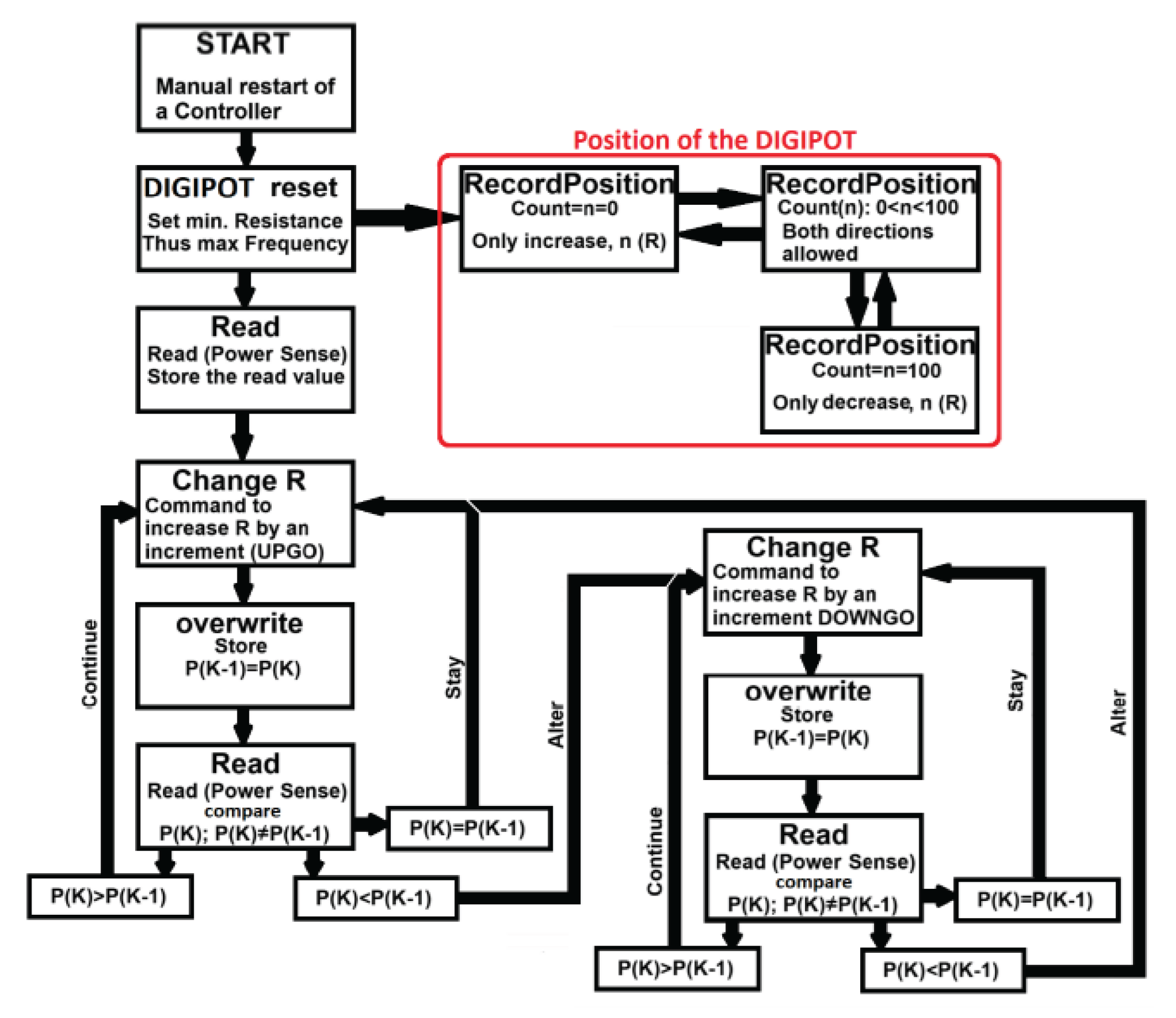

Figure 3.

The MPPT control loop dynamically adjusts the driving frequency to track changes in resonance caused by variations in load or transducer temperature, ensuring continuous delivery of peak power to the transducer.

Figure 3.

The MPPT control loop dynamically adjusts the driving frequency to track changes in resonance caused by variations in load or transducer temperature, ensuring continuous delivery of peak power to the transducer.

Startup and Buffalo Blue Sky collaborator funding supported research at the University at Buffalo, USA, while NCODE seed funding at the University of Birmingham, UK, supported validation of an in vitro bioreactor for co-culture.

2.6. Power Amplifier and Frequency Control

The ultrasound transducer in our system is a piezoelectric device that operates most efficiently at its resonant frequency. Even slight deviations from this frequency can markedly reduce power transfer due to the high Q-factor of the transducer. It is therefore important to include an active frequency control loop using MPPT. The transducer can be driven by a Class D half-bridge switching amplifier, chosen for its high electrical efficiency and ability to deliver the needed power levels in a compact form. Class D operation (pulse-width modulated switching) does introduce significant electrical noise and harmonics, which makes traditional phase-lock or zero-crossing feedback methods less reliable. Instead, the design employs a feedback strategy based on direct power measurement. Two commercial sensor ICs are used to continuously measure the voltage and current delivered to the transducer, from which the instantaneous electrical power consumed can be calculated. This measured power serves as the feedback signal for the MPPT algorithm. In essence, the controller slightly perturbs the driving frequency and observes the effect on power; it then adjusts the frequency in the direction that increases power, iterating until the maximum power point is found and maintained. Through this mechanism, the system can find, lock onto, and track the transducer’s resonant frequency in real time. When the resonance drifts due to changes in the load or the transducer’s temperature, the MPPT loop automatically compensates by shifting the driving frequency to the new resonant point, thus continuously delivering peak power into the transducer. This approach yields both maximal acoustic output and high electrical efficiency without manual tuning. By avoiding phase-detection circuits and instead using a simplified power-control signal, the design remains robust against the distortions of the switching amplifier. In summary, the amplifier+MPPT controller combination ensures the transducer always operates at its optimal frequency and power output, even over extended treatment periods or varying conditions.

2.7. Cavitation Detection and Acoustic Feedback Control

In addition to electrical feedback, our system incorporates an acoustic feedback mechanism geared towards monitoring the cavitation activity induced by the ultrasound. Cavitation, i.e., the formation and violent collapse of microbubbles in a liquid or tissue, is a key effect of high-intensity ultrasound and can contribute to tissue ablation (though in the context of precise nerve ablation and NICS neuromodulation, excessive cavitation might be undesirable as it can cause unpredictable tissue damage). In our design, a wide-bandwidth microphone (sensitive in the range ~100 Hz to 80 kHz) is positioned near the ultrasound focus or in the coupling medium to eavesdrop on acoustic emissions during therapy. The rationale is that the onset of cavitation is accompanied by distinct acoustic signatures, specifically, the emission of broadband noise and subharmonic frequencies (integer fractions of the main ultrasound frequency) that are not present during purely linear ultrasound propagation. In experimental testing, when the transducer was driven at ~28 kHz in water, the microphone reliably detected not only the 28 kHz fundamental tone but also strong signals at the half-frequency (~14 kHz) and one-third frequency (~9 kHz) once cavitation bubbles began to form. These subharmonics appeared concurrently with observable cavitation effects (such as visible microbubbles). The system processes the microphone signal (using filtering to isolate the subharmonic band) and feeds this information to the controller. This enables a form of closed-loop control where the presence and intensity of cavitation can guide the therapy, e.g., if strong cavitation is desired (in certain therapeutic strategies [

21]), the controller could increase power until subharmonic signals indicate robust cavitation, then modulate to sustain that level. Conversely, if cavitation is to be avoided (to prevent tissue damage), the controller can detect its onset and dial back the power. This acoustic feedback loop provides a direct handle on the ultrasound’s bioeffect in real time. Notably, this method is highly responsive, i.e., small changes in cavitation activity are sensed immediately via acoustic emissions, and it requires minimal additional hardware (a microphone and filter), making it an elegant complement to the electrical MPPT control. In the context of facet joint therapy, acoustic monitoring could ensure that the ultrasound dose is sufficient to gently ablate nerve tissue (perhaps indicated by a threshold of acoustic emission).

2.8. Real-Time Resonance Tracking for Therapeutic Application

The integration of MPPT and cavitation feedback is particularly advantageous for maintaining treatment efficacy during a focused ultrasound procedure. As treatment progresses, factors like tissue heating, blood flow, and patient motion can alter the acoustic environment and the transducer’s load characteristics. The proposed system integrates real-time resonance tracking with ultrasound imaging feedback (subharmonics source localisation), ensuring the transducer consistently operates at peak performance by dynamically compensating for shifts in acoustic impedance caused by temperature or tissue changes. This is critical in long treatments (for example, an ablation that might last several minutes of cumulative sonication) because a detuned transducer would deliver far less energy to the target. The MPPT controller continuously adjusts the driving frequency on the order of milliseconds, effectively “hunting” around the resonance to ensure maximum power transfer at all times. Meanwhile, the ultrasound imaging can serve as a safeguard and optimization tool by listening to the subharmonic signals, the system can infer whether the ultrasound focus is achieving the intended effect (nerve ablation should correlate with heating of tissue, which in turn produces acoustic emissions). If the treatment area or conditions change (e.g. changes in tissue perfusion), the combination of electrical and acoustic feedback allows the system to adapt quickly. In a fully realized clinical device, these feedback controls could be tied into a closed-loop protocol that automatically adjusts focus, power, duration, or frequency to achieve a desired therapeutic endpoint (for instance, termination of sonication once a certain acoustic feedback signature is observed, indicating successful treatment). Thus, the engineering system described here lays the groundwork for a smart focused ultrasound therapy platform, i.e., one that not only delivers energy precisely, but also monitors and adjusts that delivery in real time for optimal outcomes.

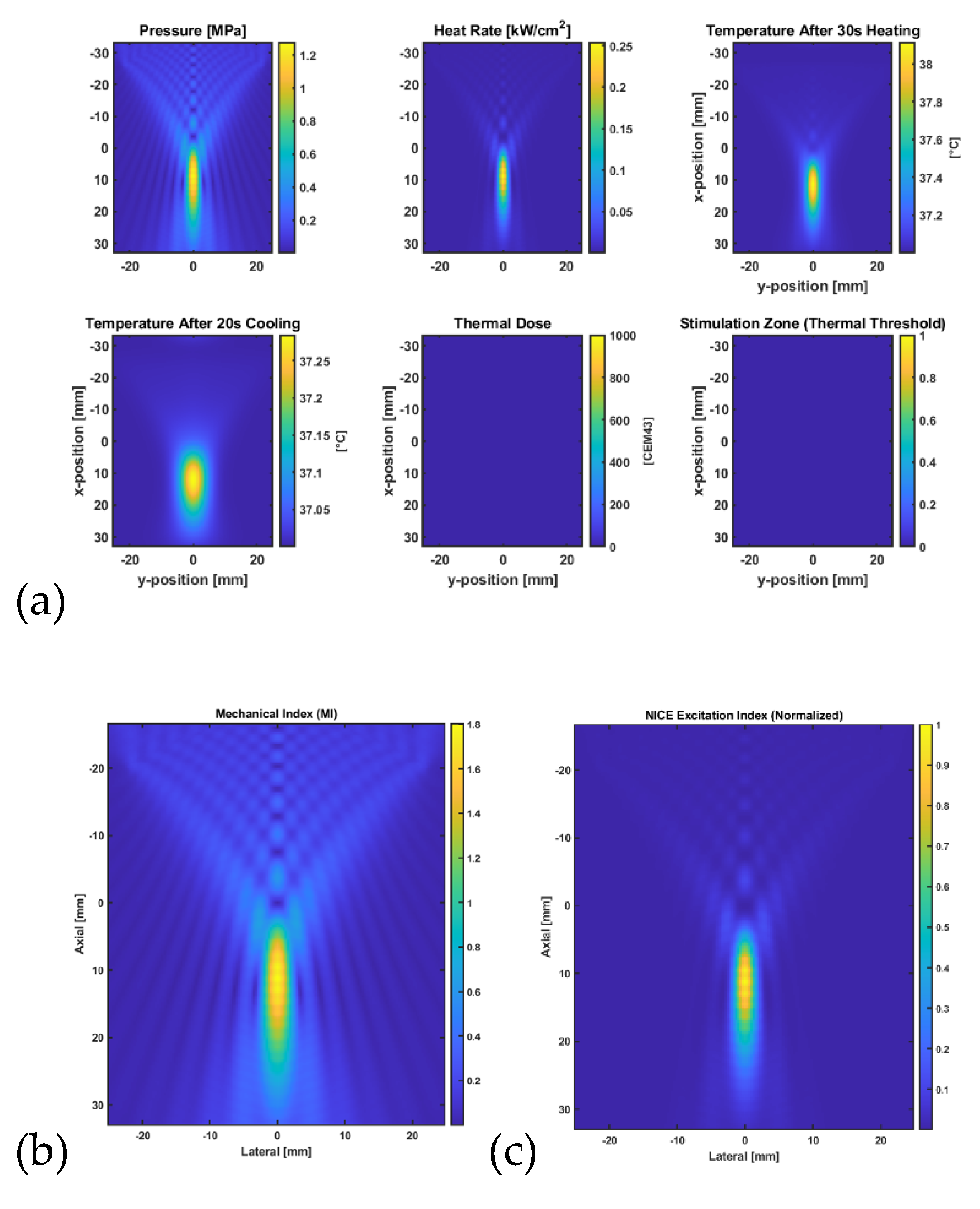

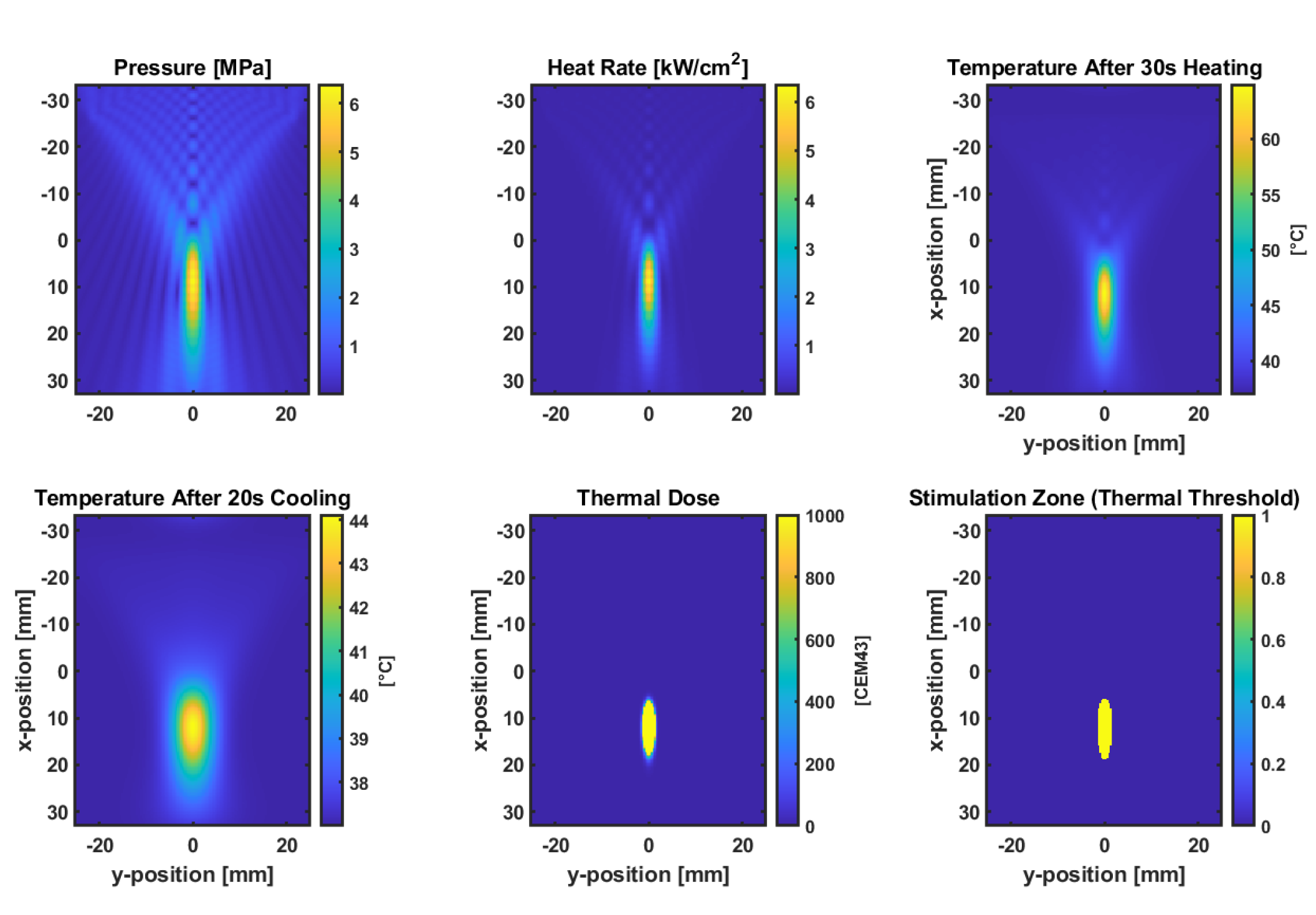

Figure 4 illustrates the simulation results that assessed the acoustic and thermal response of a focused bowl transducer targeting a lumbar facet joint model at a 45 mm depth using the k-Wave MATLAB toolbox. A continuous-wave 0.5 MHz insonation was applied at a pressure amplitude of 100 kPa for 30 seconds, followed by 20 seconds of passive cooling. The resulting peak pressure distribution confirmed focal localization, with heat deposition calculated from acoustic absorption. The bioheat equation simulated a temperature rise above baseline (37°C), and the accumulated thermal dose (CEM43). A mechanical index (MI) map was generated to evaluate safety limits, and an excitation proxy based on the NICE model estimated the likelihood of neuromodulatory effects. The highest NICE index and MI were co-localized near the acoustic focus, suggesting potential for targeted, non-ablative neuromodulation. The FDA-approved MI limit of 1.9 represents the maximum permissible threshold for diagnostic ultrasound imaging to minimize the risk of cavitation-related bioeffects.

2.9. Thermal Simulation for Ablation

Figure 5 shows the results from simulation modelling the acoustic and thermal effects of a focused bowl ultrasound transducer targeting the lumbar facet joint at a 45 mm depth, using a continuous wave at 0.5 MHz and a peak pressure amplitude of 0.5 MPa. Pressure fields and heating rates were computed via the k-Wave toolbox, and bioheat transfer modelling was performed using the kWaveDiffusion class. After 30 seconds of insonation followed by 20 seconds of cooling, the tissue temperature at the focus exceeded 43°C, with the thermal dose map (CEM43) confirming a localized ablation zone. The results indicate that the chosen ultrasound parameters can generate sufficient thermal dose for controlled ablation in moderately perfused tissue [

22].

3. Results

3.1. Acoustic Simulation for Neuromodulation

3.2. MPPT Controller Performance

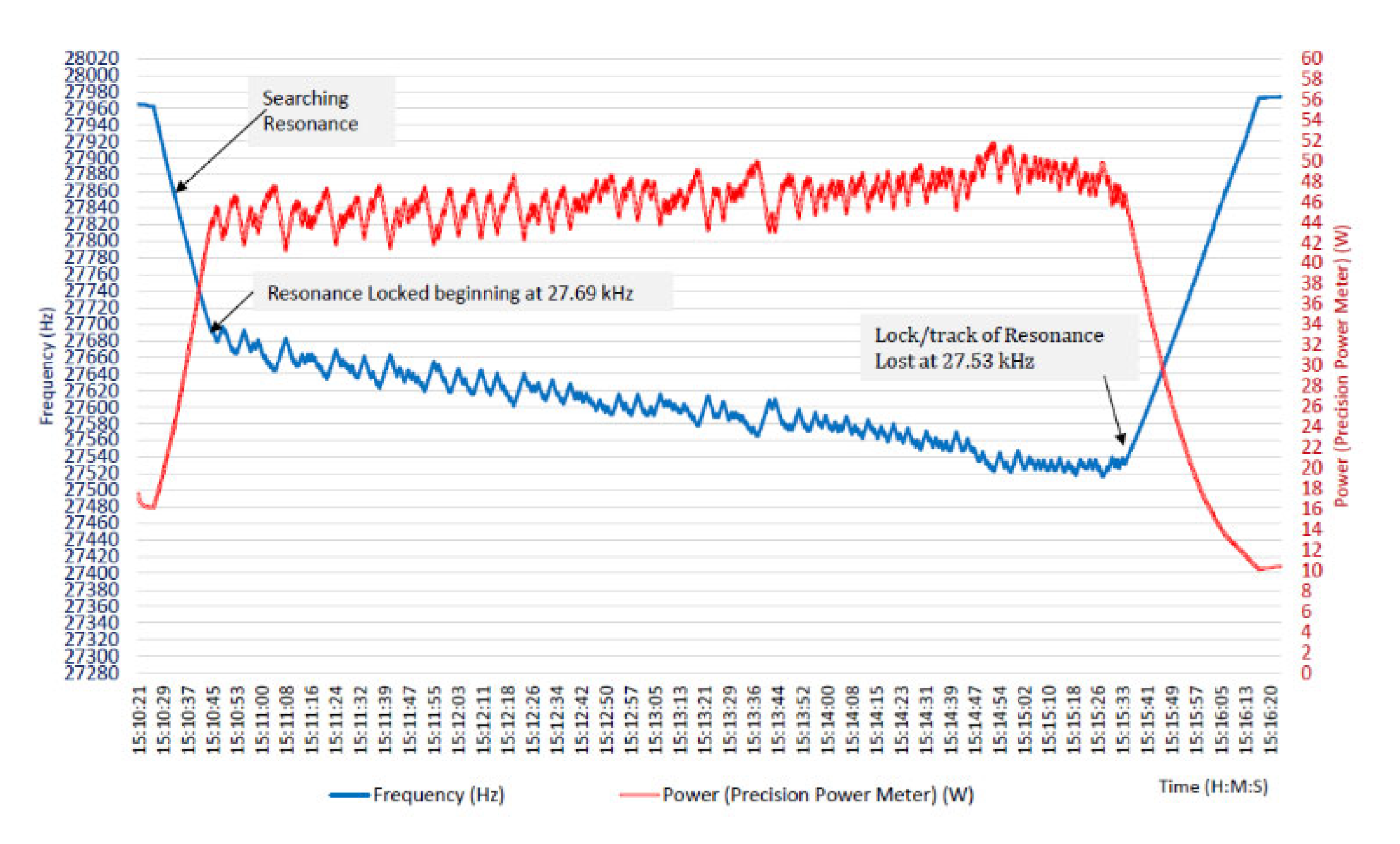

The prototype focused ultrasound driving system was validated through bench experiments using piezoelectric transducers in liquid media (water) to simulate treatment conditions. The MPPT frequency control proved highly effective in finding and maintaining the transducer’s resonant frequency under varying conditions. For example, in one test the transducer’s series resonance was initially measured at approximately 27.69 kHz. The MPPT algorithm was activated, and within a short time it had locked onto the resonance and brought the transducer output power to near its maximum rated value (in this case, about 45–50 W). The system then continuously operated in a closed-loop manner for an extended period (several minutes), tracking the resonant frequency as it gradually shifted due to self-heating of the transducer and other factors. Notably, over ~5 minutes of run time, the controller automatically adjusted the drive from 27.69 kHz to about 27.53 kHz to follow the transducer’s drift. Despite this 160 Hz change in frequency, the delivered power remained consistently high, actually showing a slight upward trend as the system optimized power transfer.

Figure 6 from Didenko’s thesis shown here recorded the frequency (blue trace) and power (red trace) over time, illustrating how the MPPT controller made small oscillatory adjustments around the resonance point, i.e., visible as minor ripples, in order to continually verify and achieve the maximum power point.

These results demonstrate that the MPPT control logic can successfully tune the system in real time, compensating for thermal or loading changes, and keep the transducer output at peak levels. Importantly, no manual re-tuning was required; the algorithm autonomously handled frequency adjustments, which is crucial for a hands-off therapy device. Operation at true resonance with optimal impedance matching maximized the electrical efficiency of the amplifier-transducer system as well. The Class D amplifier, when coupled with the MPPT controller, delivered power in a highly efficient manner, i.e., minimal energy was wasted as heat in the electronics because the controller avoided off-resonance conditions that can cause elevated currents and losses. The prototype could run for prolonged periods without significant performance degradation, maintaining stable voltage and current waveforms. By holding the transducer at its power peak, the system inherently ensured it was at the highest vibrational amplitude for a given drive voltage, thus maximizing the acoustic output (important for achieving therapeutic heating in tissue). In summary, the technical validation showed that the feedback-controlled amplifier could reliably drive an ultrasonic transducer at its dynamic resonant frequency and sustain maximum acoustic power output over time. This capability is a critical foundation for any focused ultrasound therapy, as it means the device can deliver the intended dose of energy consistently and efficiently.

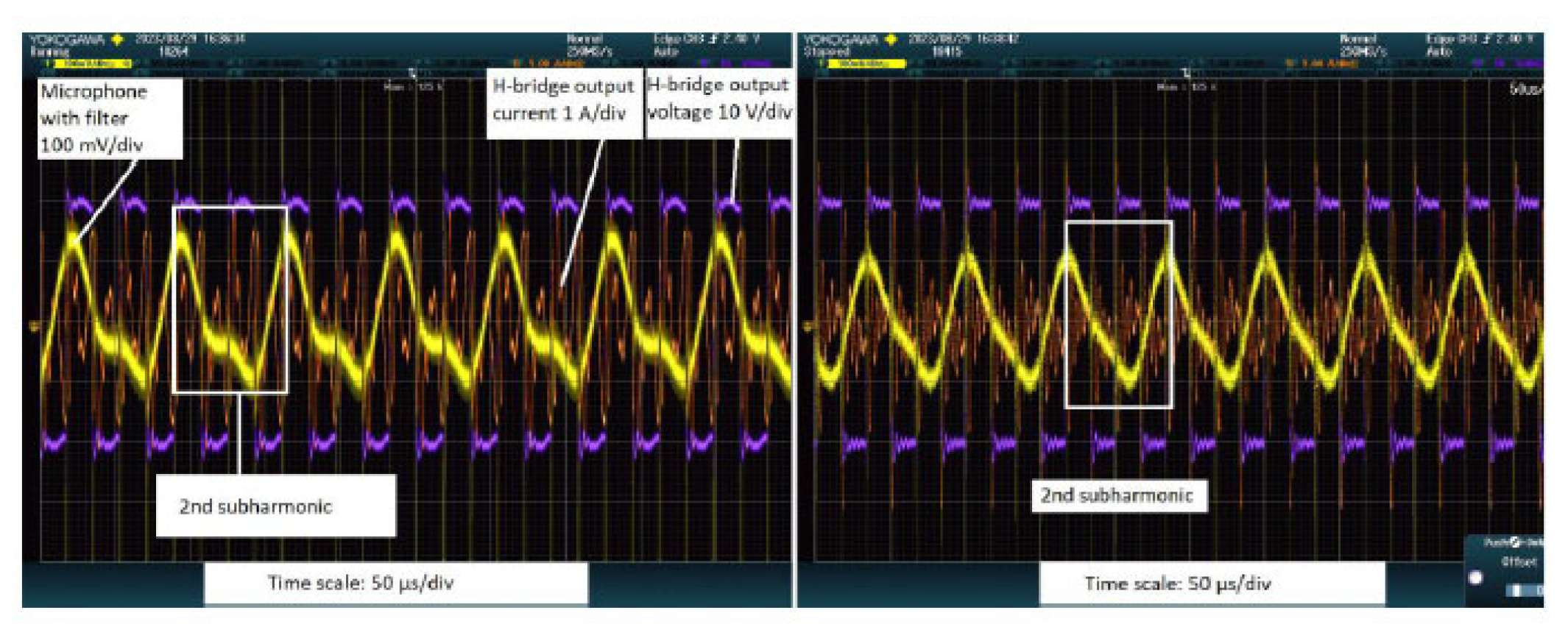

3.3. Cavitation Detection and Feedback Results

The experiments also verified the ability of the acoustic monitoring system to detect cavitation events in real time. During high-power ultrasound tests in a water bath, we performed the standard aluminum foil test, i.e., a thin foil placed in the ultrasound field becomes pitted with tiny holes when cavitation bubbles form and implode, to qualitatively confirm cavitation. Concurrently, the wideband microphone listening to the bath recorded the acoustic spectrum of emissions. The results were clear, when the ultrasound power was increased to the cavitation threshold, the microphone signal began to exhibit distinct subharmonic frequencies at half and one-third of the driving frequency (along with broadband noise), whereas below the cavitation threshold these subharmonics were absent. For instance, at an excitation frequency of ~28 kHz, a strong peak around 14 kHz (the 1/2 subharmonic) and another around ~9 kHz (the 1/3 subharmonic) appeared in the audio spectrum once cavitation bubbles were actively forming. Subjectively, a high-pitched audible sound (on the order of a few kHz) could be heard emanating from the apparatus when cavitation was present, corresponding to these subharmonic tones.

Figure 7 from Didenko’s thesis shows the microphone output and confirmed the emergence of subharmonic peaks precisely during the periods of cavitation (correlated with visible bubble activity) and their disappearance when the power or frequency moved away from cavitation conditions.

These findings validated that an acoustic sensor could serve as a cavitation detector, providing at least a yes/no (possibly, even quantitative to be validated in the future) indication of whether the ultrasound is causing cavitation activity in the medium. Building on detection, we propose validating this acoustic feedback as an alternative control input for the system. In principle, the controller could adjust the drive output to modulate cavitation, e.g., increasing power until the desired level of subharmonic signal is achieved (meaning sufficient cavitation for neuromodulation versus ablation effect) and then maintaining that level by slight power or frequency tweaks. The experimental runs demonstrated feasibility by showing the acoustic feedback’s responsiveness. It offers a fast-response feedback loop since any change in cavitation (even momentary) instantly alters the acoustic emissions, which the controller can pick up in real time. Additionally, this method directly ties into the effectiveness of the ultrasound delivery rather than optimizing an electrical parameter (power input) alone, the system could optimize an outcome parameter (cavitation intensity, which relates to the stress being imparted to tissues). In the context of therapy, such a feedback mechanism could help ensure that enough energy is being deposited to achieve ablation (since a certain threshold of tissue effect would produce acoustic emissions), thereby acting as a safety net against under-treating or over-treating. Overall, the experiments confirmed that our system can not only drive the transducer at resonance but also sense the acoustic by-products of ultrasound-tissue interaction, laying the groundwork for closed-loop therapeutic control. The combined evidence from the prototype’s performance is that a focused ultrasound treatment system can be made adaptive and self-regulating, potentially leading to more consistent and safer clinical outcomes.

4. Discussion

FUS therapy for facet joint pain represents a paradigm shift when compared to conventional interventions like RF ablation, steroid injections, or surgery. The results of our responsive ultrasound system, together with emerging clinical data, suggest several key advantages in efficacy, safety, and patient experience.

4.1. Efficacy and Clinical Outcomes

Both RF neurotomy and FUS aim to achieve facet joint denervation, and clinical studies indicate that when patient selection is appropriate, both can effectively reduce pain. Conventional RF medial branch ablation has a long track record of pain relief rates of roughly 60–80% at 3–6 months are commonly reported in the literature for well-selected patients (those with successful diagnostic blocks)[

12]. Focused ultrasound now appears capable of matching these outcomes. In the first prospective FUS trials, pain scores likewise fell by 4+ points (on a 0–10 scale) in the months following treatment. The 30-patient study by Gofeld et al. [

12] documented an average pain score improvement from 7.1 to 3.3 at 6 months post-FUS, with 82.6% of patients meeting the responder criterion (at least a 2-point pain reduction without increased opioids). These numbers are on par with, if not better than, typical RF results over the same timeframe. Furthermore, a systematic review of focused ultrasound for facet pain noted that all clinical reports to date showed meaningful pain reduction at follow-ups up to a year, and no treatment failures or adverse events were reported [

11]. While long-term durability beyond one year remains to be fully studied for FUS (since it is a newer modality), the current evidence suggests that its efficacy in the medium term is at least equivalent to RF ablation. It is also worth noting that focused ultrasound can target not only the medial branch nerve but also the periarticular tissue; some studies used FUS to heat the facet joint capsule as well [

11]. Then, Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound (LIPUS) shows promise in treating osteoarthritis, but current research is limited by inconsistent treatment parameters and a lack of standardized protocols [

23]. The biological effects of LIPUS depend heavily on variables such as intensity, frequency, and exposure time, which are not yet optimized for clinical use. Moreover, combining LIPUS with biomaterials offers exciting potential for enhanced therapeutic outcomes, though technical challenges remain. Despite encouraging preclinical results, clinical applications are still mostly restricted to symptom relief

4.2. Safety and Side Effect Profile

Focused ultrasound’s noninvasive nature yields a dramatically different safety profile compared to interventions involving needles or incisions. There is no risk of infection because the skin is not broken with FUS. There are also no scars or wound healing issues, and patients can usually resume normal activity almost immediately after the procedure. In contrast, RF medial branch neurotomy, while considered minimally invasive, still entails inserting probe needles into the paraspinal area under sterile conditions. Though complications are infrequent, there is a finite risk of infection, hematoma, or nerve damage (if the needle placement is imperfect) in any needle-based procedure. RF neurotomy may be incomplete or aborted when patients are unable to tolerate prone positioning or experience intolerable pain during the procedure. Another consideration is radiation exposure where RF ablations are often guided by fluoroscopy (X-ray), which exposes both patient and clinician to ionizing radiation. Focused ultrasound, particularly under MRI guidance, avoids ionizing radiation altogether, which is a safety benefit for patients who may require that. Regarding side effects, RF ablation typically causes local soreness for days to weeks and can cause a small region of numbness or dysesthesia in the distribution of the lesioned nerve (as reported in ~20% of patients in some series)[

24],[

25]. Patients had some post-procedure localized pain, and a minority had numbness in the back area due to the nerve ablations. Focused ultrasound, by contrast, has so far not shown comparable side effects in clinical trials, patients have “tolerated the procedure well” with no significant side effects or complications observed [

12]. The absence of neuropathic side effects is notable; presumably, FUS lesions the nerve in a controlled focal spot similar to RF, but without mechanically irritating it via needle insertion or causing collateral muscle/skin injury that could contribute to pain. This improved safety and tolerability profile means FUS could be repeated or applied to multiple levels with less concern. It may also make FUS suitable for patients who are on anti-coagulation or have higher infection risk, for whom injections or surgery would be contraindicated. In summary, focused ultrasound offers a significantly safer and less invasive experience, which is likely to translate to higher patient satisfaction.

4.3. Profile Precision and Technical Advantages

Both RF and FUS rely on accurate targeting of a small nerve branch. In RF procedures, precision depends on the interventionalist’s skill in needle placement using anatomical landmarks using fluoroscopic views, along with patient feedback (stimulating the needle to elicit tingling in the paraspinal muscles and more importantly excluding twitches along the distribution of the main nerve root which mandates readjustment of RF electrode). In contrast, focused ultrasound targeting is image-guided and can be extremely precise, especially under MRI. The ability to visualize the exact anatomic target (the facet joint or the nerve region) in real time and to monitor temperature rise in the tissue (with MR thermometry) means that the ablation can be confined to the intended spot with millimeter accuracy. The FUS energy can also be shaped and steered electronically or by adjusting the transducer, allowing multiple adjacent treatment spots to cover a larger nerve area if needed without additional incisions. This potentially addresses one limitation of traditional RF i.e. the anatomical variations. For example, the sacral lateral branch nerves (analogous to lumbar medial branches) have a variable course, and standard RF probes may miss some of them; cooled RF was introduced to create larger lesions to account for this variability. FUS, with its ability to produce a precise yet volumetric lesion by moving the focal point, could similarly cover the anatomical variations of the nerve’s path without requiring multiple needles or a larger probe. Repeatability is another major advantage of FUS. Because FUS does not damage intervening tissue along the beam path, the same device can be used flexibly for either ablation or neuromodulation, depending on clinical needs. This non-invasive approach allows treatments to be safely repeated if pain recurs or if the initial response is insufficient. One could retreat the same facet joints months or years later with essentially the same technique and low risk. Repeating RF ablation is certainly done in practice, but repeated invasive procedures can become progressively less appealing to patients and can lead to cumulative scar tissue around the nerve or target area. With FUS, each treatment is independent and does not physically alter the approach path. Additionally, the feedback-controlled system we demonstrated could further improve precision by maintaining the transducer at resonance. Moreover, by incorporating acoustic feedback from ultrasound imaging, the system ensures consistent dose delivery and adapts to real-time changes in tissue or treatment conditions. Traditional RF generators do not have that adaptive control; they deliver set energy for a set time and cannot adjust if, say, tissue impedance changes or if the patient moves slightly. The ultrasound imaging feedback mechanisms proposed for FUS provide a level of control that can result in a more reliable lesion size and effect. This might reduce instances of under-treatment (if the focus was slightly off or energy was insufficient) which can happen with RF if the needle is not perfectly placed and aligned. Thus, technologically, FUS can be made a very precise and controllable tool, well-suited to ablate small pain-causing nerves with minimal collateral impact.

4.4. Patient Compliance and Workflow

The introduction of FUS could streamline the treatment process for facet joint pain, improving patient compliance. Under current standards, patients often undergo weeks or months of conservative therapy, then multiple diagnostic injections, before finally receiving a definitive RF ablation if indicated. Each step has drop-offs due to patient reluctance (needles in the spine can be intimidating and painful) and logistical burden. Focused ultrasound could potentially reduce the number of procedures, i.e., it might serve as a one-step therapeutic and diagnostic procedure. For instance, if a patient has a history and exam suggestive of facet pain, rather than performing MBB, the physician could perform a FUS neuromodulation. If the patient’s pain improves significantly afterward, that both confirms the diagnosis and provides lasting therapy effectively combining the diagnostic and ablation treatment phases. Here, in cases of uncertainty, a low-intensity FUS sonication (below the threshold for permanent ablation) could be used as a “test”, analogous to a diagnostic block, since ultrasound can also be used to modulate nerve activity transiently [

26]. The concept of using high-frequency currents or pulses for temporary nerve blocks has been discussed in pain management; low intensity focused ultrasound might achieve a similar effect noninvasively, allowing a trial treatment without irreversible changes. This would avoid the scenario of patients going through painful diagnostic blocks only to be denied further therapy if the blocks are negative. From a patient experience standpoint, FUS is likely to be far more palatable. The elimination of needles is a huge psychological relief for many patients with needle phobia or anxiety. Additionally, recovery is essentially immediate with FUS where patients do not have puncture wounds or significant post-procedure pain, so compliance with follow-up and rehabilitation (exercises, etc.) may improve because the patient is not sidelined by soreness. All these factors suggest that patient compliance and satisfaction could be higher with focused ultrasound, and the overall pathway from diagnosis to relief could be faster and smoother. There will likely be less need for post-procedure pain medication, and patients can return to work or daily activities more quickly, which has socioeconomic benefits.

4.5. Comparative and Economic Considerations

From a healthcare systems perspective, focused ultrasound might also prove cost-effective in the long run. While the upfront cost of FUS equipment is high, eliminating multiple injections and procedures per patient can offset this. For example, under current practice a patient may have diagnostic blocks (MBB) and RF ablation only after a successful outcome of MBB, that is at least two interventional sessions plus associated imaging and medications. If instead one FUS session achieves the result, that is a reduction in resource utilization. Moreover, if FUS provides longer-lasting relief (a hypothesis to be tested as more long-term data emerge), it could reduce the frequency of retreatment. If focused ultrasound can match or surpass RF outcomes, supported by early data showing a 6-month responder rate of 82.6% [

12], it could reduce dependence on pain medications and additional interventions, thereby lowering the overall costs of chronic pain management. Additionally, the fact that several devices like the Insightec Exablate and FUSMobile have obtained approval in Europe/Canada means that payers and providers are beginning to invest in this technology. Over time, economies of scale and procedural efficiency could make FUS a financially favorable option as well. The expanding body of clinical evidence and engineering advances also strongly support FUS as a promising therapeutic modality, not only in its established role in stroke neuromodulation [

27], but also in emerging applications such as the treatment of osteoarthritis [

28].

4.6. Limitations

The ultrasound imaging feedback-controlled FUS system enhances treatment precision by using acoustic signals to monitor tissue response in real time. It can detect signs of effective nerve targeting such as cavitation from acoustic changes, funding the source, and adjusting energy delivery accordingly. This allows for personalized treatment reducing power near critical structures to prevent damage or increasing intensity if the tissue resists ablation. Unlike fixed-dose RF, this adaptive approach may improve safety, consistency, and outcomes. A key limitation of this study is the use of a low, fixed frequency (28 kHz) for controller testing, which lacks the spatial precision and safety profile needed for targeted neuromodulation. At this frequency, the large wavelength (~5.5 cm) limits millimeter-scale targeting and increases the risk of off-target effects due to reduced cavitation thresholds. For reference, the relationship between frequency and clinical utility was found to be roughly as follows; at 28 kHz, the wavelength is ~5.5 cm, which is too diffuse; at 250 kHz, ~6 mm is suitable for deep neuromodulation; at 500 kHz, ~3 mm is standard for focused therapy; and at 1 MHz, ~1.5 mm enables high precision for shallow targets. While 28 kHz was suitable for early prototyping, future development needs to incorporate adaptive focusing at higher frequencies (200 kHz–1.5 MHz), which offer better spatial resolution, safer cavitation control, and are more appropriate for deep, localized neuromodulation.