Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

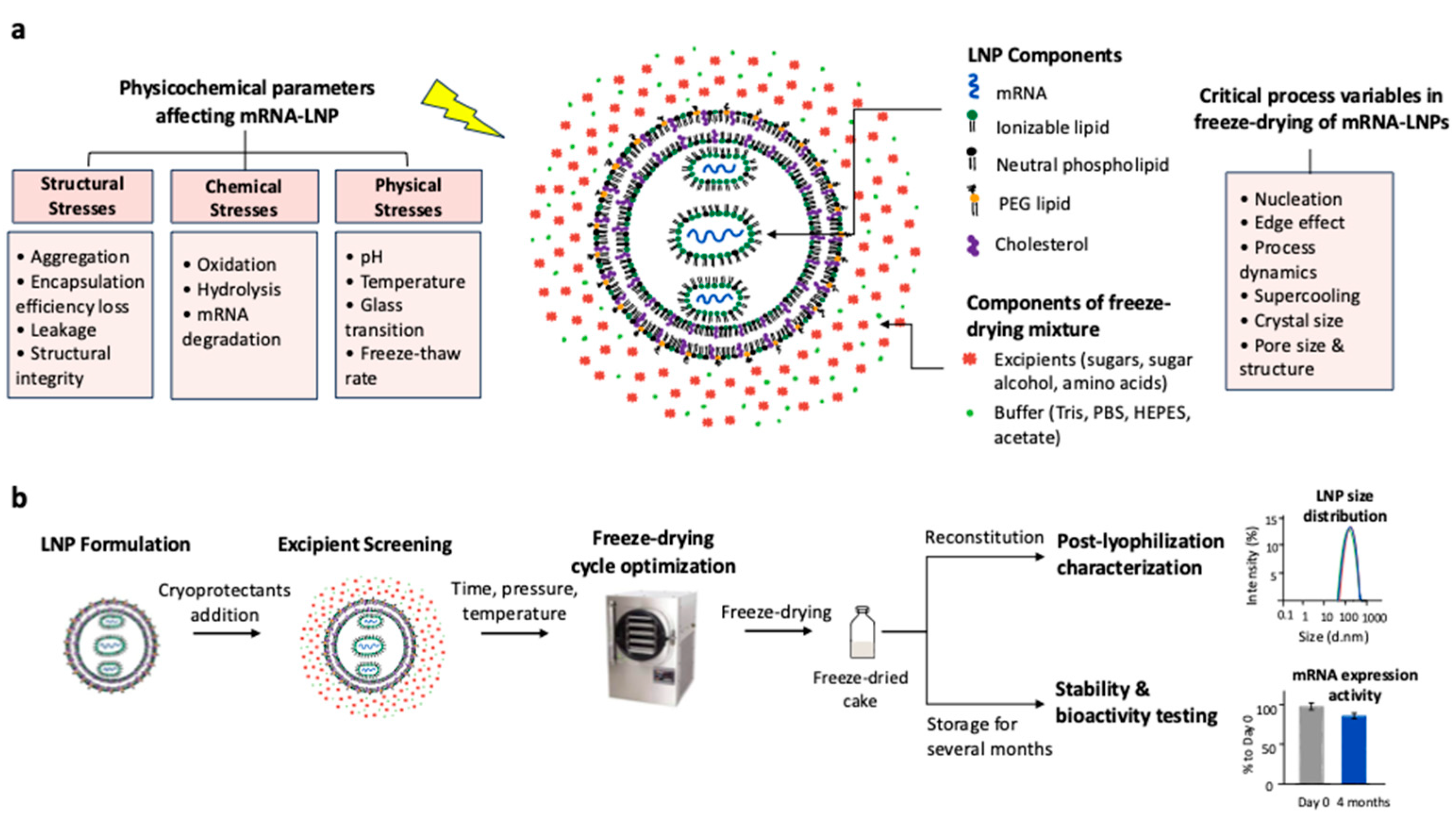

2. Stability of mRNA-LNP Vaccines

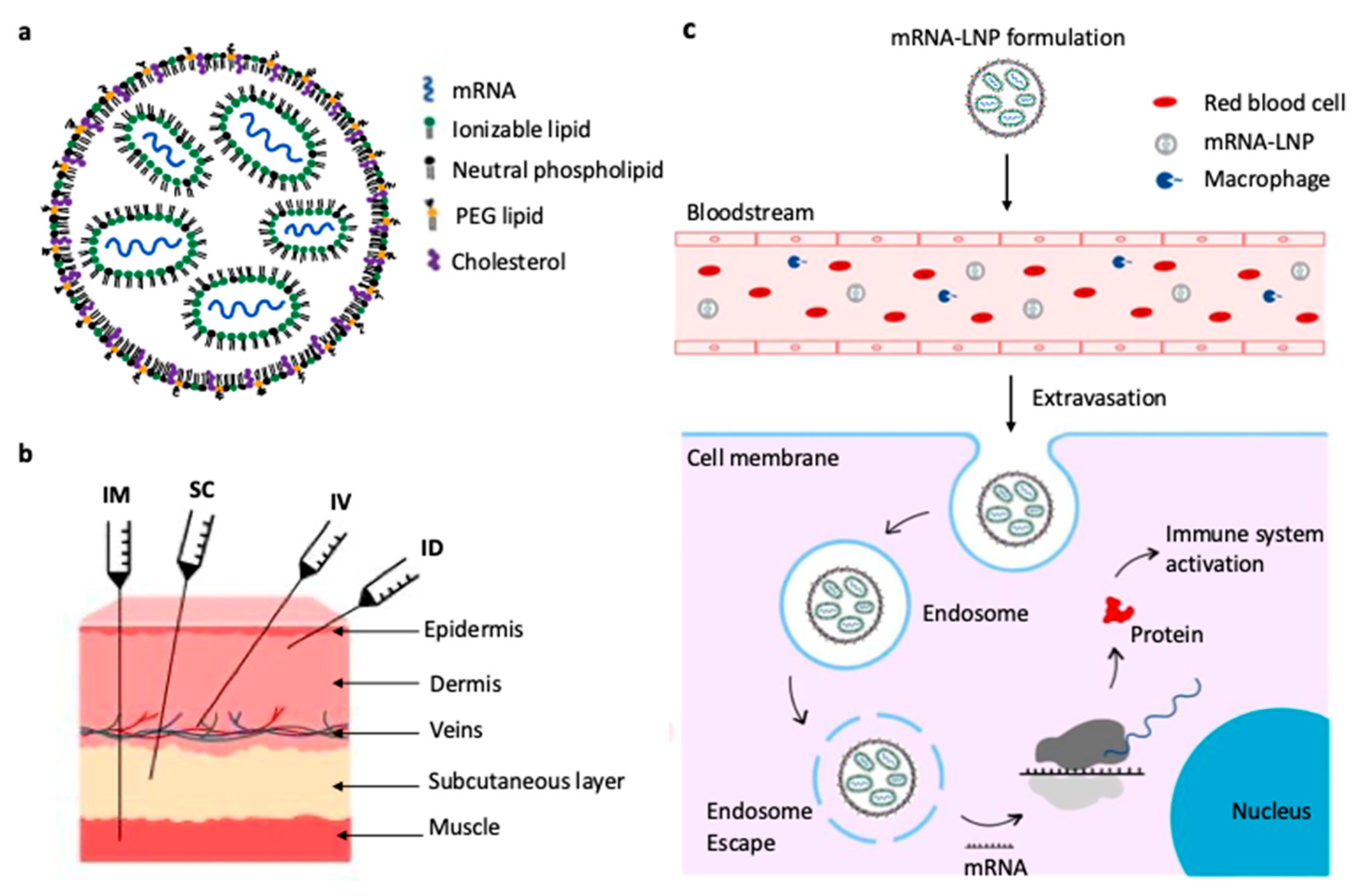

2.1. Structure of mRNA-LNP Vaccines

2.2. Stabilizing mRNA-LNP Through Freeze-Drying

2.3. Challenges During Freeze-Drying of mRNA-LNP

3. Formulations

3.1. Influence of Lipid Composition

3.2. Stabilizers

3.2.1. Sugars

3.2.2. Sugar Alcohols

3.2.3. Amino Acids

| Formulations | Protecting Mechanism | Positive Impacts on mRNA-LNP | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sugars | Sucrose | Protective coating and prevents mechanical damage, vitrification (formation of a glassy matrix), water replacement (hydrogen bonds), cryoprotection | Prevents LNP aggregation, preserves particle size, maintains mRNA integrity, reduces freeze and dehydration stresses | [7,12,47,53,54] |

| Trehalose | Increase formulations' viscosity, high glass transition temperature (Tg), low crystallization risk, vitrification, water replacement, cryoprotection | Higher Tg' than sucrose, maintains structural integrity, enhances LNP' resistance to drying | [22,49,53,55,56,57] | |

| Maltose | Glass matrix formation | Often combined with sucrose, helps prevent structural collapse | [21,58] | |

| Sugar alcohol | Mannitol | Bulking agent, prevents cake shrinkage | Prevents cake collapse, may reduce aggregation but can crystallize unfavorably | [37,46,50] |

| Buffer choices | Tris | Scavenges hydroxyl radicals, stabilizes pH during freezing | Reduces pH shift, improves encapsulation and transfection efficiency, and reduces zeta potential shift | [39,42,59,60,61] |

| PBS | Ionic stabilization maintains a stable pH during freezing and drying but is prone to pH shift in the presence of sodium ion | Common but inferior to Tris, used for its ionic strength, can decrease encapsulation efficiency and stability | [37,39,42,59] | |

| HEPES | PH buffering, stabilizing effect during freeze-thaw | Helps to maintain LNP's integrity during freeze-thaw cycles and long-term storage | [59] | |

3.3. Influence of pH and Buffer

3.4. Impact of Reconstitution Buffer

| Formulations (w/v) | Buffer/ pH | Reconstitution | Stability | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% sucrose 10% maltose |

5 mM Tris/ pH 8 | Water | Physicochemical properties do not significantly change for 12 weeks after storage at room temperature and for at least 24 weeks after storage at 4°C | [21] |

| 8.8% sucrose, 2% trehalose, 0.04% mannitol |

- | - | The lyophilized mRNA-LNP were stable at 2–8 °C, and it did not reduce immunogenicity in vivo or in vitro. | [68] |

| 8.7% sucrose | (PBS) | 90 μl of nuclease-free water | Optimal O9 mRNA-LNP could be stored at 4 °C for more than 12 weeks and at room temperature for 4 weeks after lyophilization. | [32] |

| 10% sucrose | PBS/ pH 7.4 | Deionized water | LNP-RNA vaccines are stably stored in 10% w/v sucrose in PBS at −20 °C for at least 30 days. | [37] |

| 20% maltose | Tris 5 mM/ pH 7.4 | 300 μl RNase-free water | Lyophilized LNP retained their in vivo bioactivity at an almost unaffected level for 1 year when stored at 4°C. Lyophilized LNP also presented unaltered thermo-stability at room temperature (25°C) for 4 weeks. | [39] |

| 12.5% sucrose | 20 mM Tris/ pH 7.4 |

400 μl of Tris-, phosphate- or PBS buffer at pH 7.4 | Lyophilized mRNA LNP preserved their functionality when stored at 4°C, 22°C and even at 37°C for 12 weeks. | [42] |

| 5% sucrose/ 5 % trehalose |

- | - | 5% (w/v) sucrose or trehalose LLNs stored in liquid nitrogen maintained mRNA delivery efficiency for over three months. | [54] |

| 9% trehalose/ 1 % PVP |

20 mM Tris / pH 7.4 | 275 μl RNase-free water | The most promising formulations for storage at higher temperatures were identified as 9% (w/v) trehalose + 1% (w/v) PVP, with only a slight increase in size over 6 months at 25 °C, while maintaining PDI and encapsulation efficiency. | [69] |

| 10% sucrose / 5% trehalose | 10 mm Tris / pH 7.4 | Water | Lyophilized mRNA-LNP can be stored at 4°C for at least 12 months and for at least 8 hours after reconstitution at ambient temperature without a significant change in product quality. They also preserved the in vitro biological activity and immunogenicity in mice, comparable to that of freshly prepared mRNA-LNP. | [70] |

| 10% sucrose / 9% mannitol / 1% PEG60 | Tris | Water | Dry powder formulation that could maintain the physicochemical properties of LNP-mRNA after storage at 4 °C for at least two months. | [66] |

| 10% sucrose | - | Nuclease-free water | Lyophilized form of LION/repRNA-CoV-2S with 10 % w/v sucrose, maintained in vivo immunogenicity after 1 week at 25 °C and 6 months at 2–8 °C. Lyophilized LION/repRNA-PyCS vaccine with 10% w/v sucrose, stored for 12 months at 2–8 °C, demonstrated no loss in immunogenicity. | [71] |

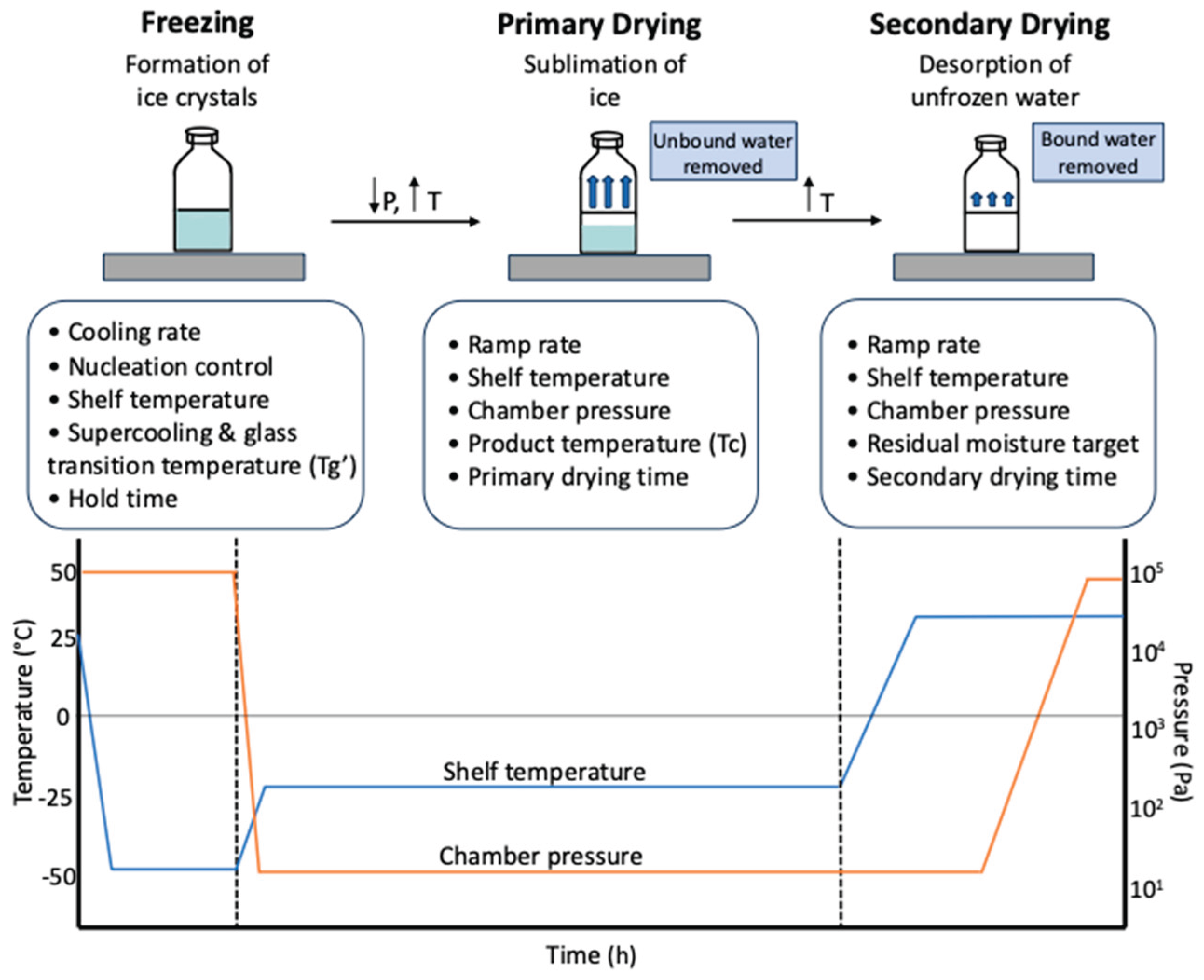

4. Lyophilization Process Development and Intensification

5. Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) and Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs)

5.1. Critical Process Parameters (CPPs)

5.2. Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs)

| Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) | Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) |

|---|---|

| • Lipid composition and molar ratios e.g., ionizable lipid, helper lipid, cholesterol, PEG-lipid) |

• Particle size and PDI (affects biodistribution, cellular uptake, and dose uniformity) |

| • Buffer type and pH (affects LNP assembly, mRNA stability, and lyophilization compatibility) |

• Encapsulation efficiency (% of mRNA encapsulated; impacts potency and dosing) |

| • Lipid: mRNA weight ratio (key determinant for encapsulation and particle stability) |

• Zeta potential (an indicator of colloidal stability and cellular interaction) |

| • Mixing rate and temperature during microfluidic formulation (impacts LNP size and uniformity) |

• mRNA integrity and purity (determines efficacy; assessed by electrophoresis, HPLC) |

| • Freeze-drying (lyophilization) cycle parameters (freezing rate, primary/secondary drying temps and pressures) |

• Lipid composition/identity post-processing (assures no degradation or phase separation) |

| • Cryoprotectant type and concentration (e.g., sucrose, trehalose; critical for preserving structure) |

• Appearance and cake structure (e.g., collapse, shrinkage, or uniformity after lyophilization) |

| • Residual moisture content (influenced by secondary drying endpoint) |

• Moisture content (affects storage stability and reconstitution) |

| • Reconstitution conditions (solvent type, volume, and agitation) |

• Reconstitution time (speed and ease of redispersion into solution) |

| • Storage temperature and container closure system | • Potency / Transfection efficiency (in vitro and in vivo functional activity of mRNA-LNP) |

6. Analytics for the Freeze-Drying Study

7. Conclusion

References

- Zhang, N.-N. et al. A Thermostable mRNA Vaccine against COVID-19. Cell 182, 1271-1283.e16 (2020).

- Chivukula, S. et al. Development of multivalent mRNA vaccine candidates for seasonal or pandemic influenza. NPJ Vaccines 6, 153 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Sittplangkoon, C. et al. mRNA vaccine with unmodified uridine induces robust type I interferon-dependent anti-tumor immunity in a melanoma model. Front Immunol 13, (2022). [CrossRef]

- Qiu, K. et al. mRNA-LNP vaccination-based immunotherapy augments CD8+ T cell responses against HPV-positive oropharyngeal cancer. NPJ Vaccines 8, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Krienke, C. et al. A noninflammatory mRNA vaccine for treatment of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Science (1979) 371, 145–153 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, F. et al. Murine liver repair via transient activation of regenerative pathways in hepatocytes using lipid nanoparticle-complexed nucleoside-modified mRNA. Nat Commun 12, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E. et al. Lipid Nanoparticle-Delivered Chemically Modified mRNA Restores Chloride Secretion in Cystic Fibrosis. Molecular Therapy 26, 2034–2046 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Perez-Garcia, C. G. et al. Development of an mRNA replacement therapy for phenylketonuria. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 28, 87–98 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G., Tang, T., Chen, Y., Huang, X. & Liang, T. mRNA vaccines in disease prevention and treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther 8, 365 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, N., Weissman, D. & Whitehead, K. A. mRNA vaccines for infectious diseases: principles, delivery and clinical translation. Nat Rev Drug Discov 20, 817–838 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T. et al. Tumour mRNA-loaded dendritic cells elicit tumor-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in patients with malignant glioma. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 52, 632–637 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, M. et al. A phase I/IIa study of the mRNA-based cancer immunotherapy CV9201 in patients with stage IIIB/IV non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 68, 799–812 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Hernando, J. J. et al. Vaccination with dendritic cells transfected with mRNA-encoded folate-receptor-α for relapsed metastatic ovarian cancer. Lancet Oncology 8, 451–454 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z. et al. Novel mRNA adjuvant ImmunER enhances prostate cancer tumor-associated antigen mRNA therapy via augmenting T cell activity. Oncoimmunology 13, (2024). [CrossRef]

- Van Tendeloo, V. F. et al. Induction of complete and molecular remissions in acute myeloid leukemia by Wilms' tumor 1 antigen-targeted dendritic cell vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107, 13824–13829 (2010).

- Golubovskaya, V. et al. mRNA-Lipid Nanoparticle (LNP) Delivery of Humanized EpCAM-CD3 Bispecific Antibody Significantly Blocks Colorectal Cancer Tumor Growth. Cancers (Basel) 15, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Sung, H. et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 71, 209–249 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Hashiba, K. et al. Overcoming thermostability challenges in mRNA–lipid nanoparticle systems with piperidine-based ionizable lipids. Commun Biol 7, (2024). [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M. N. & Roni, M. A. Challenges of Storage and Stability of mRNA-Based COVID-19 Vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 9, 1033 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Young, R. E., Hofbauer, S. I. & Riley, R. S. Overcoming the challenge of long-term storage of mRNA-lipid nanoparticle vaccines. Molecular Therapy 30, 1792–1793 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Muramatsu, H. et al. Lyophilization provides long-term stability for a lipid nanoparticle-formulated, nucleoside-modified mRNA vaccine. Molecular Therapy 30, 1941–1951 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Hansen, L. J. J., Daoussi, R., Vervaet, C., Remon, J.-P. & De Beer, T. R. M. Freeze-drying of live virus vaccines: A review. Vaccine 33, 5507–5519 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Hou, X., Zaks, T., Langer, R. & Dong, Y. Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nature Reviews Materials vol. 6 1078–1094 . [CrossRef]

- Ai, L. et al. Lyophilized mRNA-lipid nanoparticle vaccines with long-term stability and high antigenicity against SARS-CoV-2. Cell Discov 9, 9 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Swetha, K. et al. Recent Advances in the Lipid Nanoparticle-Mediated Delivery of mRNA Vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 11, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Sercombe, L. et al. Advances and challenges of liposome assisted drug delivery. Front Pharmacol 6, (2015). [CrossRef]

- Granot, Y. & Peer, D. Delivering the right message: Challenges and opportunities in lipid nanoparticles-mediated modified mRNA therapeutics—An innate immune system standpoint. Semin Immunol 34, 68–77 (2017). [CrossRef]

- AboulFotouh, K. et al. Effect of lipid composition on RNA-Lipid nanoparticle properties and their sensitivity to thin-film freezing and drying. Int J Pharm 650, (2024). [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X. & Lee, R. J. The role of helper lipids in lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) designed for oligonucleotide delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 99, 129–137 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Eygeris, Y., Gupta, M. & Sahay, G. Self-assembled mRNA vaccines. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 170, 83–112 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Hajj, K. A. & Whitehead, K. A. Tools for translation: Non-viral materials for therapeutic mRNA delivery. Nat Rev Mater 2, (2017). [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. et al. Design and lyophilization of mRNA-encapsulating lipid nanoparticles. Int J Pharm 662, 124514 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Schoenmaker, L. et al. mRNA-lipid nanoparticle COVID-19 vaccines: Structure and stability. Int J Pharm 601, 120586 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Houseley, J. & Tollervey, D. The Many Pathways of RNA Degradation. Cell 136, 763–776 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Trenkenschuh, E. & Friess, W. Freeze-drying of nanoparticles: How to overcome colloidal instability by formulation and process optimization. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 165, 345–360 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Packer, M., Gyawali, D., Yerabolu, R., Schariter, J. & White, P. A novel mechanism for the loss of mRNA activity in lipid nanoparticle delivery systems. Nat Commun 12, 6777 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Kim, B. et al. Optimization of storage conditions for lipid nanoparticle-formulated self-replicating RNA vaccines. Journal of Controlled Release 353, 241–253 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Li, W. et al. Application of Saccharide Cryoprotectants in the Freezing or Lyophilization Process of Lipid Nanoparticles Encapsulating Gene Drugs for Regenerative Medicine. (2024). [CrossRef]

- Alejo, T. et al. Comprehensive Optimization of a Freeze-Drying Process Achieving Enhanced Long-Term Stability and In Vivo Performance of Lyophilized mRNA-LNPs. Int J Mol Sci 25, 10603 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Shirane, D. et al. Development of an Alcohol Dilution–Lyophilization Method for the Preparation of mRNA-LNPs with Improved Storage Stability. Pharmaceutics 15, 1819 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Shirane, D. et al. Development of an Alcohol Dilution–Lyophilization Method for the Preparation of mRNA-LNPs with Improved Storage Stability. Pharmaceutics 15, 1819 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Meulewaeter, S. et al. Continuous freeze-drying of messenger RNA lipid nanoparticles enables storage at higher temperatures. Journal of Controlled Release 357, 149–160 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Gan, K. H., Bruttini, R., Crosser, O. K. & Liapis, A. I. Freeze-drying of pharmaceuticals in vials on trays: effects of drying chamber wall temperature and tray side on lyophilization performance. Int J Heat Mass Transf 48, 1675–1687 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Klepzig, L. S., Juckers, A., Knerr, P., Harms, F. & Strube, J. Digital twin for lyophilization by process modeling in manufacturing of biologics. Processes 8, 1–31 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. et al. Effect of mRNA-LNP components of two globally-marketed COVID-19 vaccines on efficacy and stability. NPJ Vaccines 8, 156 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.-C. et al. Impact of formulation on the quality and stability of freeze-dried nanoparticles. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 169, 256–267 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Kafetzis, K. N. et al. The Effect of Cryoprotectants and Storage Conditions on the Transfection Efficiency, Stability, and Safety of Lipid-Based Nanoparticles for mRNA and DNA Delivery. Adv Healthc Mater 12, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Flood, A., Estrada, M., McAdams, D., Ji, Y. & Chen, D. Development of a Freeze-Dried, Heat-Stable Influenza Subunit Vaccine Formulation. PLoS One 11, e0164692 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L. S. & Zografi, G. Sugar–polymer hydrogen bond interactions in lyophilized amorphous mixtures. J Pharm Sci 87, 1615–1621 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, K. et al. Stable and inhalable powder formulation of mRNA-LNPs using pH-modified spray-freeze drying. Int J Pharm 665, 124632 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Kommineni, N., Butreddy, A., Sainaga Jyothi, V. G. S. & Angsantikul, P. Freeze-drying for the preservation of immunoengineering products. iScience 25, 105127 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Falconer, R. J. Advances in liquid formulations of parenteral therapeutic proteins. Biotechnol Adv 37, 107412 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Lball, R., Bajaj, P. & Whitehead, K. A. Achieving long-term stability of lipid nanoparticles: Examining the effect of pH, temperature, and lyophilization. Int J Nanomedicine 12, 305–315 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P. et al. Long-term storage of lipid-like nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Bioact Mater 5, 358–363 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y. et al. Trehalose in Biomedical Cryopreservation-Properties, Mechanisms, Delivery Methods, Applications, Benefits, and Problems. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 9, 1190–1204 (2023).

- Sola-Penna, M. & Meyer-Fernandes, J. R. Stabilization against Thermal Inactivation Promoted by Sugars on Enzyme Structure and Function: Why Is Trehalose More Effective Than Other Sugars? Arch Biochem Biophys 360, 10–14 (1998).

- Roos, Y. Melting and glass transitions of low molecular weight carbohydrates. Carbohydr Res 238, 39–48 (1993). [CrossRef]

- Elbrink, K., Van Hees, S., Holm, R. & Kiekens, F. Optimization of the different phases of the freeze-drying process of solid lipid nanoparticles using experimental designs. Int J Pharm 635, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Henderson, M. I., Eygeris, Y., Jozic, A., Herrera, M. & Sahay, G. Leveraging Biological Buffers for Efficient Messenger RNA Delivery via Lipid Nanoparticles. Mol Pharm 19, 4275–4285 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Oude Blenke, E. et al. The Storage and In-Use Stability of mRNA Vaccines and Therapeutics: Not A Cold Case. J Pharm Sci 112, 386–403 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Kolhe, P., Amend, E. & Singh, S. K. Impact of freezing on pH of buffered solutions and consequences for monoclonal antibody aggregation. Biotechnol Prog 26, 727–733 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F. et al. Research Advances on the Stability of mRNA Vaccines. Viruses 15, 668 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Lewis, L. M., Badkar, A. V., Cirelli, D., Combs, R. & Lerch, T. F. The Race to Develop the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine: From the Pharmaceutical Scientists' Perspective. J Pharm Sci 112, 640–647 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Wayment-Steele, H. K. et al. Theoretical basis for stabilizing messenger RNA through secondary structure design. bioRxiv (2021). [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y. et al. Physicochemical and structural insights into lyophilized mRNA-LNP from lyoprotectant and buffer screenings. Journal of Controlled Release 373, 727–737 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y. et al. Design and lyophilization of lipid nanoparticles for mRNA vaccine and its robust immune response in mice and nonhuman primates. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 30, 226 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Garidel, P., Pevestorf, B. & Bahrenburg, S. Stability of buffer-free freeze-dried formulations: A feasibility study of a monoclonal antibody at high protein concentrations. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 97, 125–139 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Li, M. et al. Lyophilization process optimization and molecular dynamics simulation of mRNA-LNPs for SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. NPJ Vaccines 8, 153 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Ruppl, A. et al. Formulation screening of lyophilized mRNA-lipid nanoparticles. Int J Pharm 671, (2025). [CrossRef]

- Wang, B. et al. Lyophilized monkeypox mRNA lipid nanoparticle vaccines with long-term stability and robust immune responses in mice. Hum Vaccin Immunother 21, 2477384 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Gulati, G. K. et al. Preclinical development of lyophilized self-replicating RNA vaccines for COVID-19 and malaria with improved long-term thermostability. Journal of Controlled Release 377, 81–92 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. F. H., Wagner, C. E. & Kamen, A. A. Development of Long-Term Stability of Enveloped rVSV Viral Vector Expressing SARS-CoV-2 Antigen Using a DOE-Guided Approach. Vaccines (Basel) 12, (2024). [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. F. H., Youssef, M., Nesdoly, S. & Kamen, A. A. Development of Robust Freeze-Drying Process for Long-Term Stability of rVSV-SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. Viruses 16, 942 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Franks, F. Freeze-drying of bioproducts: putting principles into practice. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 45, 221–229 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Ghaemmaghamian, Z., Zarghami, R., Walker, G., O'Reilly, E. & Ziaee, A. Stabilizing vaccines via drying: Quality by design considerations. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 187, (2022). [CrossRef]

- Lamoot, A. et al. Successful batch and continuous lyophilization of mRNA LNP formulations depend on cryoprotectants and ionizable lipids. Biomater Sci 11, 4327–4334 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Stitz, L. et al. A thermostable messenger RNA based vaccine against rabies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 11, e0006108 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, D., Noro, J., Silva, C., Cavaco-Paulo, A. & Nogueira, E. Protective Effect of Saccharides on Freeze-Dried Liposomes Encapsulating Drugs. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 7, (2019). [CrossRef]

- Anindita, J. et al. Development of a Ready-to-Use-Type RNA Vaccine Carrier Based on an Intracellular Environment-Responsive Lipid-like Material with Immune-Activating Vitamin E Scaffolds. Pharmaceutics 15, 2702 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Patel, S. M. et al. Lyophilized Drug Product Cake Appearance: What Is Acceptable? J Pharm Sci 106, 1706–1721 (2017).

- Li, B. et al. Combinatorial design of nanoparticles for pulmonary mRNA delivery and genome editing. Nat Biotechnol 41, 1410–1415 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Sato, S. et al. Understanding the Manufacturing Process of Lipid Nanoparticles for mRNA Delivery Using Machine Learning. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo) 72, 529–539 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Identifying Critical Quality Attributes for mRNA/LNP. https://www.biophorum.com/news/an-industry-standard-for-mrna-lnp-analytics/.

- A guide to RNA-LNP formulation screening - Inside Therapeutics. https://insidetx.com/review/a-guide-to-rna-lnp-formulation-screening/.

- Koganti, V., Luthra, S. & Pikal, M. J. The Freeze-Drying Process: The Use of Mathematical Modeling in Process Design, Understanding, and Scale-Up. in Chemical Engineering in the Pharmaceutical Industry: R&D to Manufacturing 801–817 (John Wiley and Sons, 2010). doi:10.1002/9780470882221.ch41.

- Defining the required critical quality attributes (CQAs) and phase requirements for mRNA/ LNP product development and manufacture Defining the required critical quality attributes (CQAs) and phase requirements for mRNA/LNP product development and manufacture 2. (2023).

- Baden, L. R. et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. New England Journal of Medicine 384, 403–416 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Haque, M. A., Shrestha, A., Mikelis, C. M. & Mattheolabakis, G. Comprehensive analysis of lipid nanoparticle formulation and preparation for RNA delivery. Int J Pharm X 8, 100283 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Hermosilla, J. et al. Analysing the In-Use Stability of mRNA-LNP COVID-19 Vaccines ComirnatyTM (Pfizer) and SpikevaxTM (Moderna): A Comparative Study of the Particulate. Vaccines (Basel) 11, 1635 (2023).

- Wang, T. et al. Development of lyophilized mRNA-LNPs with high stability and transfection efficiency in specific cells and tissues. Regen Biomater 12, (2025).

- Schmidt, A., Helgers, H., Vetter, F. L., Juckers, A. & Strube, J. Digital Twin of mRNA-Based SARS-COVID-19 Vaccine Manufacturing towards Autonomous Operation for Improvements in Speed, Scale, Robustness, Flexibility and Real-Time Release Testing. Processes 9, 748 (2021). [CrossRef]

| Freezing (Temperature/ Time) | Primary drying (Temperature/ Pressure/ Time) | Secondary drying (Temperature/ Pressure/ Time) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| -45 °C / 3h | -25 °C / 2.7 Pa / 84h | 30 °C / 2.7 Pa / 5h | [21] |

| -40 °C / 2h | -35 °C / 10 Pa / 24h | 25 °C / 5h | [76] |

| -40 °C / 2h | -10 °C / 16 Pa / 17h | 2 °C / 6.8 Pa / 10h | [77] |

| -80 °C / 6h | -50 °C / 6 Pa / 24h | [78] | |

| -30 °C / 3h | -25 °C / 5-10 Pa / 16-18h | 22-27 °C / 20 Pa / 5h | [32] |

| -80 °C | 12h | - | [53,54] |

| -40 °C / 40 min -40 °C / 20 min |

-30 °C / 1h -20 °C / 1h -10 °C / 1h 0 °C / 1h |

10 °C / 1h 20 °C / 1h 30 °C / 3h |

[40,79] |

| -50 °C / 5h | -15 °C / 24 Pa / 12h |

30 °C / 13.3 Pa / 7h |

[39] |

| -40 °C / 3h | -20 °C / 13 Pa/ 10h | 25 °C / 5h | [69] |

| -20 °C | -30 °C / 3 Pa/ 30h | 25 °C / 3 Pa / 6h | [70] |

| -50 °C / 3h | -50 °C / 1h / 27 Pa -40 °C / 1h / 27 Pa -35 °C / 12h / 27 Pa |

30 °C / 10h | [66] |

| -50 °C / 1.5h | -30 °C / 7 Pa / 17.5h | 25 °C / 7 Pa / 1.5h | [71] |

| Property | Analytical Method | Reference Study | Recommended Standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle size | Dynamic light scattering (DLS) | [21,32,37,39,42,54,68] | Between 80 and 110 nm for optimal cellular uptake and biodistribution |

| Nanoparticle morphology, size, and internal structure | Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Cryogenic Electron Microscope Cryo-Transmission Electron Microscopy (Cryo-TEM) |

[32,37,39,69] [21,68] [68,70] [24,66] |

Uniform spherical or vesicular structures depending on the design Between 50 and 150 nm for optimal cellular uptake and biodistribution |

| Polydispersity index (PDI) | Dynamic light scattering (DLS) | [21,32,39,42,68] | ≤ 0.2 indicates a homogeneous particle population |

| Zeta potential | Electrophoretic light scattering (ELS) Dynamic light scattering (DLS) |

[32,37,39,42,54] | ± 20 to 30 mV is generally sufficient for colloidal stability and minimal aggregation |

| mRNA encapsulation efficiency | Quant-it Ribogreen fluorescence assay | [21,32,39,42,68] | ≥ 90-95% is typically targeted for therapeutic efficacy |

| mRNA concentration | Ribogreen fluorescence assay | [21,39] | Consistency across batches is key, the quantitative threshold depends on dose |

| mRNA integrity | Capillary electrophoresis | [21,32,39,68] | Intact single bands, degradation products should be minimal or absent |

| Lipid content | Ultra high-performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) | [21] | Must match expected lipid: mRNA molar ratios |

| Residual moisture | Karl Fischer Titration | [69] | < 1% w/w is typically recommended to ensure long-term stability and prevent degradation |

| Visual appearance (cake quality) | Visual inspection (macroscopic evaluation) | [69] | Cake should be uniform, white, intact, without collapse or shrinkage |

| In vitro transfection efficiency | Luciferase report assay, GFP expression assay | [39,90] | Comparable or improved transfection vs freshly prepared LNP |

| In vitro cytotoxicity | Cell viability assays (CCK-8, MTT) | [68,90] | Usually, > 80% cell viability |

| In vivo immunogenicity | ELISA, HAI assay/titer | [21,24,68] | Robust and comparable immune response to fresh vaccine |

| In vivo biodistribution | IVIS imaging, fluorescence/ RNA quantification in organs | [39,90] | Distribution to the target tissue, low off-target accumulation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).