1. Introduction

Chemically and genetically inactivated pertussis toxin (PTx) is one of the most important antigenic components that compromise current acellular pertussis vaccines1-3. Glutaraldehyde, a protein cross-linking agent, has been widely used by many vaccine manufacturers to deactivate PTx over the past few decades. Glutaraldehyde could react actively with N-terminal amino groups of peptides, α-amino groups of amino acids, and sulfhydryl groups of cysteine, resulting in modifications of the surface of PTx and the formation of complex, high-molecular-weight protein species4,5. Our previous unpublished and others’ work have demonstrated that the structural changes impaired biochemical activities (residual toxicity) dependent on modifications of its two distinct functional domains: an A protomer (consisting of S1 subunit) and a B oligomer (made up of S2, S3, S4, and S5 subunits)6-8. In addition, glutaraldehyde treatment also destroys the immunogenicity of PTx9,10. Detoxified PTx must maintain reasonable immunogenicity to ensure the high quality of acellular pertussis vaccines; thus, quality control of PT toxoid (PTd) is important.

It was proved that the overall structure changes could affect both linear and conformational epitopes, which can, in turn, influence immunogenicity4,10. Additionally, neutralizing antibodies directed against wild-type PTx fail to recognize chemically detoxified PTx11. Taken together, the integrity of the natural structure of PTx is critical for its antigenicity or immunogenicity. However, it is still unclear how the alterations in the structure of PTx could affect its antigenic properties and immunogenicity. Furthermore, how much the changes in antigenic characteristics could impair immunogenicity remained explored. In this context, an assay able to quantify antigenic properties of PTx could specifically indicate its quality post-detoxification.

Our unpublished work indicated that glutaraldehyde treatment causes dramatic structural changes in the A protomer and B-oligomer, especially the S2 subunit. We hypothesize that the structural alterations impair neutralizing epitopes on the two functional domains. Accordingly, we established a sandwich ELISA analyzing antigenic properties of PTd preparations by using two monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) 1B7 against S1 and 11E6 against the S2/3 subunit as the detecting antibody. The two mAbs directly neutralize epitopes in the S1 and S2/3 regions of PTx, and their protective activities are demonstrated in vitro and vivo12-16. Subsequently, we applied the established ELISA assay to evaluate the retention of neutralizing epitopes on PTx with different degrees of detoxification. Then, the immunogenicity of acellular pertussis vaccine candidates containing various PTd preparations was evaluated by measuring serum anti-PTx-specific IgG. A correlation analysis of anti-PTx-specific antibody response and the number of neutralizing epitopes was performed. Finally, the assay was applied to assess the consistency of commercial batches of PTx and PTd intermediates. We are excited to share these notable findings in this manuscript and hope our work could give insightful indications for others working on developing and manufacturing acellular pertussis vaccines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of PTd and PTd Containing Vaccine Formulation

To investigate the detoxification effect of glutaraldehyde concentration on PTx, various PTd preparations were produced as described but with modification17. In brief, purified PTx was detoxified with 0.5% glutaraldehyde in 50% glycerol for different times ranging from 10 minutes to 24 hours. The detoxification process was performed at room temperature and terminated by adding sodium L-aspartate to a final concentration of 0.25 M. Subsequently, the detoxification mixture was diafiltered through a 30-kD membrane and then sterile filtered. To obtain acellular pertussis vaccine candidates, 25 μg PTd was absorbed into 1.3 mg/mL aluminum hydroxide.

2.2. Assay of Neutralizing Epitopes in S1 and S2/3 Subunits

Neutralizing epitopes in the S1 and S2/3 subunits were quantified using a sandwich ELISA established in this study. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies (pAbs) against PTd, prepared as we previously described, were used as the capture antibody18. Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) specific to the S1 (1B7, NIBSC code 99/506) and S2/3 (11E6, NIBSC code 99/526) subunits served as the detecting antibody. In brief, 96-well microtitration plates (Greiner Bio-One, Fricken-hausen, Germany) were pre-coated with murine pAbs and incubated overnight at 4°C. The plates were washed four times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 as the washing buffer. For blocking, 100 μL of PBS containing 2% milk (assay buffer) was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. After aspirating the assay buffer, in-house reference (PTx) and PTd samples were prepared with the assay buffer and added to the wells. The starting concentration of PTx was set at 200 ng/mL to construct standard curves, with up to six serial dilutions used. Detecting mAbs were added according to the manufacturer’s instructions, followed by secondary peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse antibodies (Sera Care, Milford, MA, USA). The absorbance of each well was measured using a Multiskan FC reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 450/630 nm. The content of neutralizing epitopes in the S1 and S2/3 subunits was expressed in ng/mL. Subsequently, the assay’s specificity, accuracy, and precision were evaluated.

2.3 . Immunization

5–6 weeks old female mice (strain NIH) were injected intraperitoneally with a 0.5 mL one-third of a human single dose of vaccine candidates or PBS. 4 weeks post-immunization, mice were anesthetized and bled for serum, the serum was separated and stored at −20 ℃ until use. In all anti-PTx serological assays, the serum raised against PBS was the negative control, and the first international reference preparation (IRP) of mouse anti-PTx serum (97/642, NIBSC) was used as the positive control.

2.4. Assay of Measuring PTx-Specific Immunoglobulins (Ig), Total IgG

Antibodies against PTx were determined by ELISA assays previously described18-20. Briefly, 96-well microtitration plates (Greiner Bio-One, Fricken-hausen, Germany) were pre-added with the purified PTx and kept overnight at 4°C. The plates were washed 5 times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20. For blocking, 100 μL of PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin (assay buffer) was added and incubated at 37°C for one hour. After the assay buffer was aspirated, NIBSC reference serum (eight steps of 2-fold dilutions (1/100 to 1/409,600) were prepared with assay buffer) and Immune sera were added (diluted 2-fold for seven dilutions starting at 1/100), followed by the addition of secondary peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse antibodies (Sera Care, Milford, MA, USA). The absorbance of each well was read using a Multiskan FC reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 450/630 nm. The antibodies against PTx were expressed in IU/mL.

2.5. Ethics Statement for Animal Experiments

All animals used in this study were housed and cared for in facilities accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC). The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) approved all experiments.

3. Results

3.1. Establishment of the Neutralizing Epitopes Qualification ELISA Assay

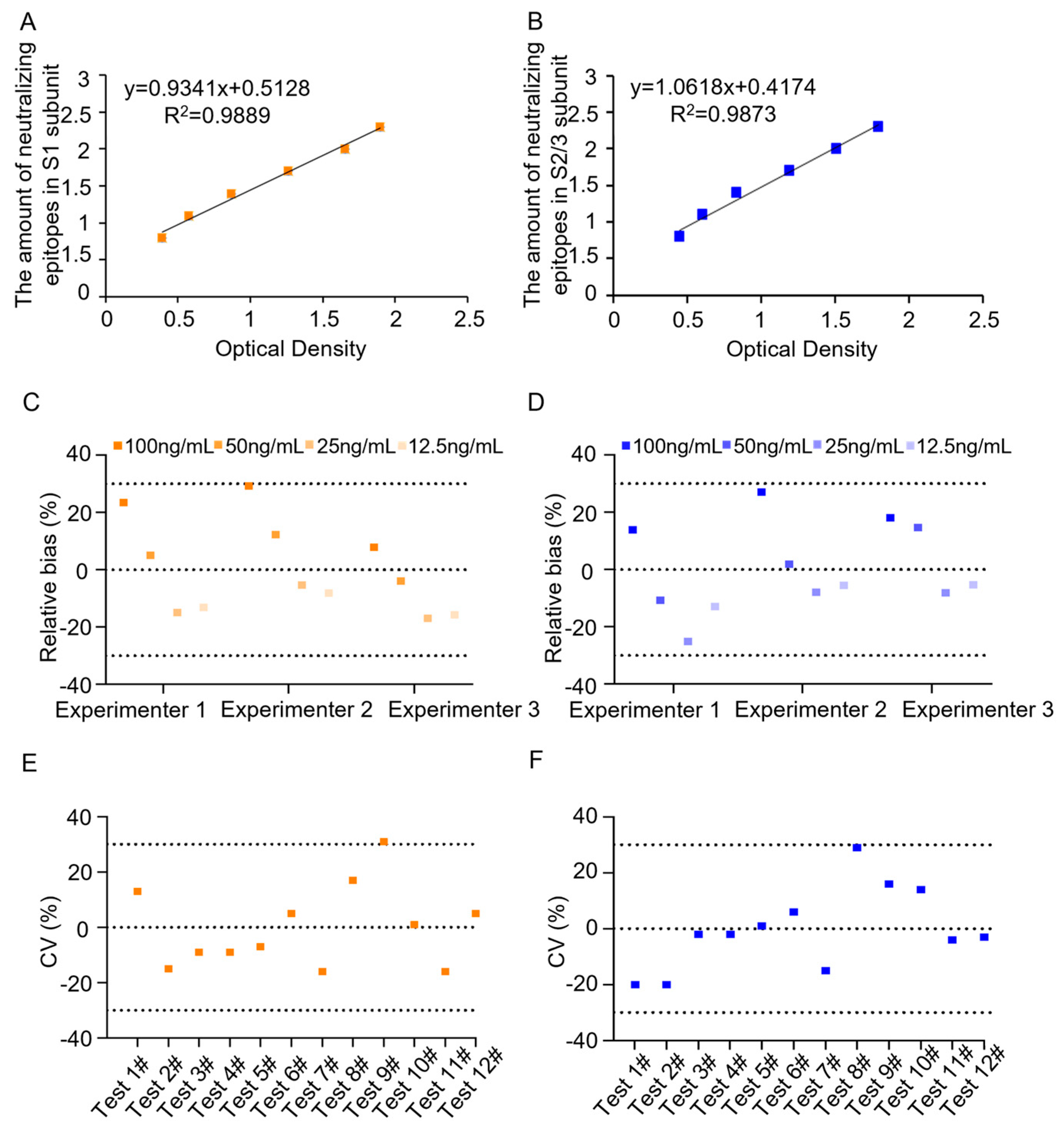

3.1.1. Working Range and Detection Limit

The 96-well plates were prepared as described in section 2.2. To determine the working range and construct the standard binding curves, the initial concentration of PTx reference was set at 400 ng/mL, followed by eight serial 2-fold dilutions: 200, 100, 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, and 3.125 ng/mL, in addition, the work concentration of pAbs for coating were investigated. The work concentrations of mAbs against S1 and S2/3 were chosen according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. A linear regression analysis was performed by plotting the logarithm of the PTx reference concentration against the corresponding optical density (OD) reading. It was observed that the curve fitting was optimal within the concentration range of 6.25 ng/mL to 200 ng/mL, with the R

2 values above 0.98 (

Figure 1). In addition, OD readings of the PTx reference at 6.25 ng/mL were significantly above the cutoff values (

Table 1). Therefore, five replicate experiments subsequently confirmed this working range, consistently yielding R² values of 0.98 or higher (

Figure S1&S2). Thus, the working range was set between 6.25 and 200 ng/mL, and the lowest detection limit was determined as 6.25 ng/mL.

3.1.2. Specificity

To validate the assay’s specificity in measuring epitopes in the S1 subunit, a batch of PTx was used as the positive control. The S2/4 subunit served as an interference control, while the assay buffer acted as the negative control. Similarly, to assess the assay’s specificity for the S2 subunit, the same batch of PTx and the S2/4 subunit were employed as the positive control, with the assay buffer as the negative control. The results showed that the OD values of the interference controls at high concentration and negative control were below the cutoff value; OD readings of the positive controls at low concentration were significantly above the cutoff value (

Table 1), indicating reasonable specificity of the assay.

3.1.3. Accuracy

To study the assay’s accuracy, produce spiked PTx samples with concentrations of 100 (high value), 50 (middle high value), 25 (middle low value), and 12.5 ng/mL (low value) by diluting the PTx reference with the assay buffer. The measured values of the spiked samples were determined by testing 3 times. The recovery rate and relative bias were then calculated based on the measured and theoretical values. The results indicated that the three spiked samples had recovery rates between 70% and 130%, with a relative bias of less than 30% (

Figure 1C&D), demonstrating good accuracy.

3.1.4. Precision

To assess the assay’s precision, we first evaluated its reproducibility by having the first experimenter analyze a batch of PTd samples six consecutive times. To evaluate the intermediate precision, the same PTd sample was tested by the second experimenter for another six consecutive times. The coefficient of variation (CV, %) of 12 results was calculated. The results showed that CVs were less than 30% (

Figure 1E&F), indicating good assay precision.

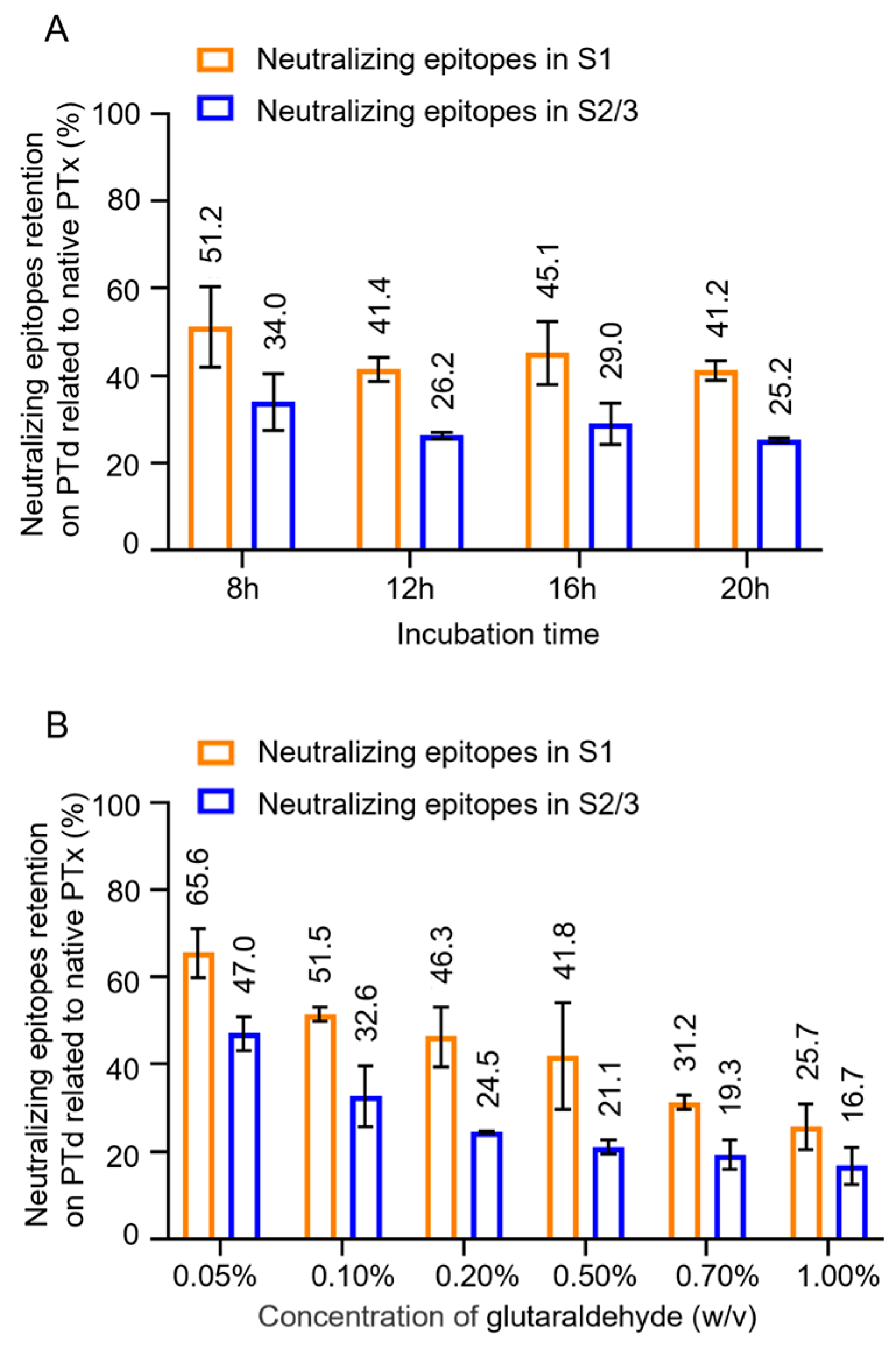

3.2. The Effect Glutaraldehyde Treatment on Antigenic Properties of PTx

The assay was conducted to analyze the changes in the antigenic properties of PTx following glutaraldehyde detoxification. Notably, as the degree of detoxification increased (with longer incubation time), there was no significant decreasing trend in the quantity of neutralizing epitopes in PTd (

Figure 2A,

Table S1). However, the retention percentage of neutralizing epitopes in the S2/3 subunit showed a more significant decline, dropping from 47.0% to 16.7%, compared to the S1 subunit, where retention decreased from 65.6% to 25.7% (

Figure 2B). This indicates that the S2/3 subunit is more sensitive to the degree of detoxification.

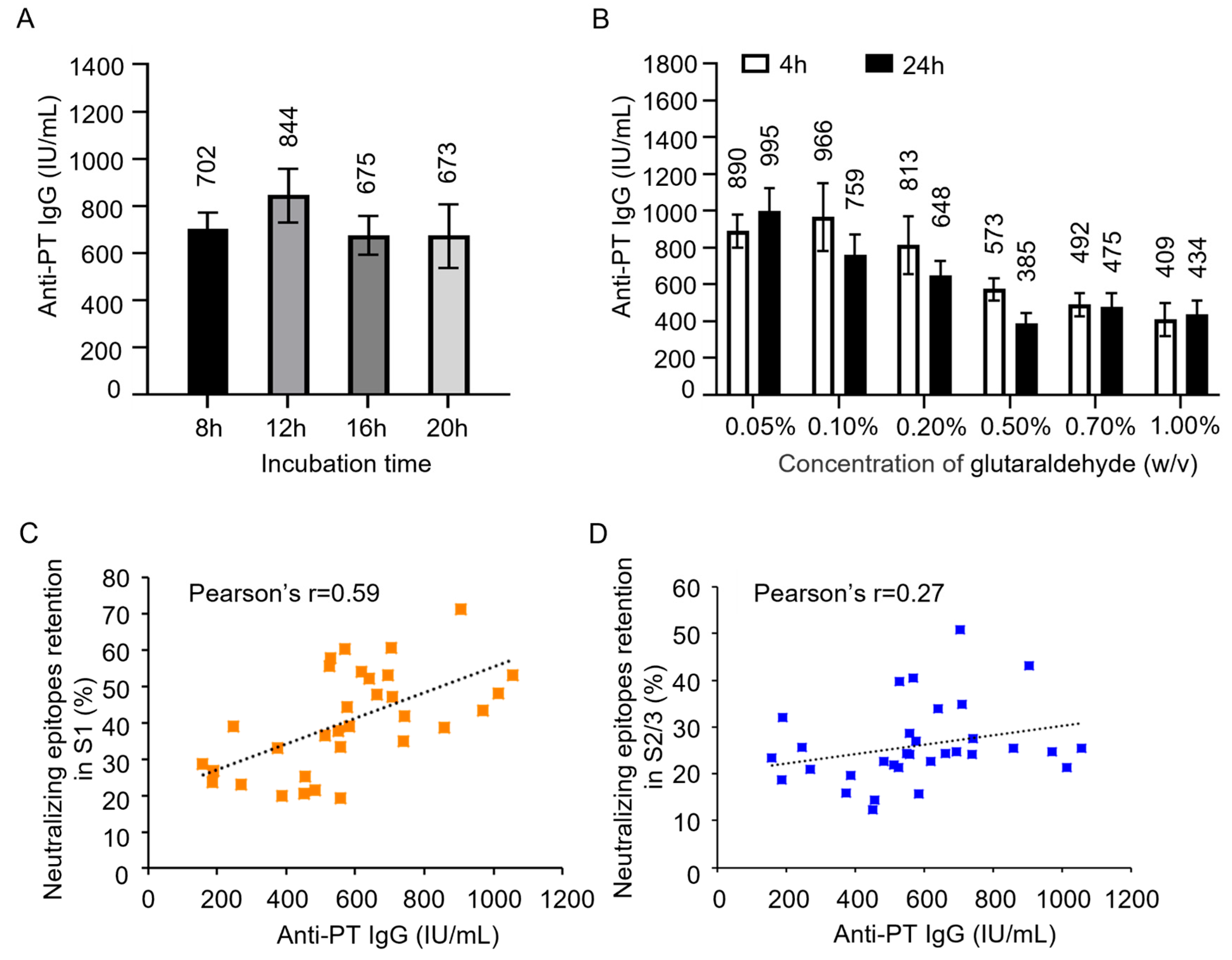

3.3. Correlation Between Neutralizing Epitope Content and Immunogenicity In Vivo

To investigate how much the retention percentage of neutralizing epitopes in PTx affects its immunogenicity and antigenicity. PTd preparations of different degrees of detoxification were absorbed into aluminum to produce acellular pertussis vaccine candidates. NIH female Mice were immunized intraperitoneally with 1/3 human single dose (16.67 μg of PTd antigen) of vaccine candidates. The anti-PTx antibody level in immunized sera was analyzed as described in “

Section 2 Materials and Methods”. As the concentration of glutaraldehyde increased, there was a decreasing trend in anti-PT IgG response (

Figure 3A-B), indicating that the detoxification degree affects the immunogenicity of PTx. In addition, we observed a strong correlation between the anti-PTx IgG response and the neutralizing epitope in the S1 subunit (Pearson’s r=0.59,

Figure 3C), while the correlation with the neutralizing epitope in the S2/3 subunit is weak (Pearson’s r=0.27,

Figure 3D).

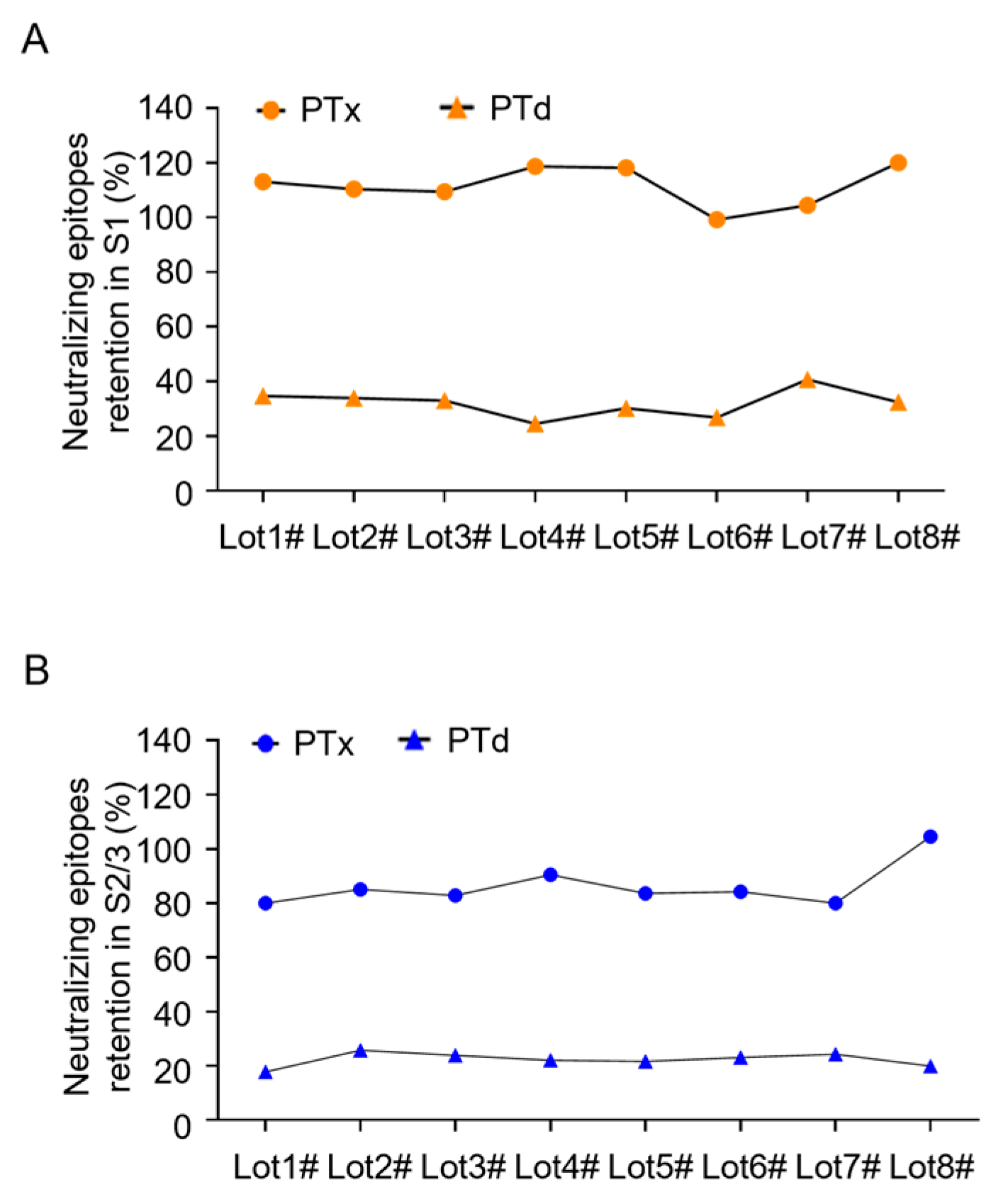

3.4. Monitoring Consistency of Neutralizing Epitopes in PTd Preparations

Our evaluation of the antigen quality and batch consistency of the PTx antigen component, based on the analysis of 8 batches of purified PTx and PTd preparations produced by identical processes, has uncovered findings with significant potential implications. The retention percentage of neutralizing epitopes was a key focus. The number of neutralizing epitopes in S1 and S2/3 subunits of the purified PTx bulks ranged from 80% to 120% related to the in-house PTx reference. In comparison, the epitopes in the S1 subunit varied between 24.5% and 40.7%, and in the S2/3, between 17.7% and 25.7% in PTd preparations. These findings indicate that the assay is suitable for evaluating batch-to-batch consistency by quantifying variations in neutralizing antibody retention.

4. Discussion

Chemical or genetically detoxified PTx is a critical component of acellular pertussis vaccines, and the quality of PTx is essential for the vaccine’s efficacy. Chemical detoxification with glutaraldehyde causes significant structural changes in PTx, leading to a reduction in bioactivities associated with the A protomer and B oligomer6-8. These structural alterations can also affect the antigen properties of PTx, potentially compromising its immunogenicity9,10. Therefore, evaluating the antigenic properties of PTx is an important topic for quality control of acellular pertussis vaccine.

In this manuscript, we introduced a sandwich ELISA assay by using two mAbs, 1B7 against S1 and 11E6 against S2/3 subunits, which accurately quantifies the number of neutralizing epitopes in the S1 and S2/3 subunits and provides a precise reflection of the antigenic changes in glutaraldehyde-inactivated PTx. This study started with the establishment and validation of the ELISA assay. Through multiple experiments, we determined the linear working range and detection limits. The assay demonstrated a wide working range from 6.25 ng/mL to 200 ng/mL, with a reasonable sensitivity as low as 10 ng/mL. Following that, the assay showed exciting specificity to the S1 subunit without cross-reactivity with subunits of B oligomer. However, we didn’t demonstrate the cross-reactivity of 11E6 with S1 because we failed to separate S1 from S2 during purification. Notably, Sato, H., and colleagues have already proved the excellent specificity of 1B7 and 11E616. The assay also exhibits good accuracy, with a recovery rate of spiked samples ranging from 70% to 130%. Additionally, the coefficient of variation of each measured value relative to the theoretical value was less than 30%, demonstrating good precision.

After its establishment, the assay was first used to assess the quality of PTd preparations with varying levels of detoxification. The assay was sensitive to detect the difference in the number (or retention percentage) of neutralizing epitopes in these PTd preparations that share the same protein content. Moreover, the immunogenicity of PTd preparations was positively correlated with the number of neutralizing epitopes retained. However, it is striking that weak correlations were found between anti-PTx IgG response and the neutralizing epitopes in the S2/3 subunit compared to the strong correlations observed for the neutralizing epitopes in the S1 subunit. This could be explained by the fact that more neutralizing epitopes were preserved in the S1 subunit of PTx post-detoxification by glutaraldehyde; in other words, the anti-PTx-specific antibody responses are triggered mainly by neutralizing epitopes retained in the S1 subunit of PTd9.

Later, the assay was used to evaluate the quality of the purified PTx bulks and PTd intermediates. Notably, these purified PTx bulks showed minor variations in the number of neutralizing epitopes, indicating good consistency between batches. Furthermore, different PTd intermediates also displayed antigenic properties with slight variations; specifically, the retention percentage of neutralizing epitopes in S1 and S2/3 subunits of PTd preparations was around 30% and 20% relative to PTx, respectively, demonstrating a stable chemical detoxification process by glutaraldehyde.

Assays for the final lot of the acellular pertussis vaccine can be conducted using in vivo methods to evaluate serology in mice or guinea pigs. However, these methods do not apply to PTd preparations due to time constraints19. However, protein content quantification is commonly performed for assaying antigen components of acellular pertussis vaccines marketed in mainland China, which is essential but insufficient for identifying the masked epitopes caused by glutaraldehyde treatment. In this context, we and others have proposed a single radial diffusion (SRD) technique for measuring the total antigen content of PTx, FHA, and PRN bypasses aldehyde-induced masking of epitopes 18,21. Although the SRD technique is valuable for batch consistency monitoring, it cannot distinguish between intact and structurally compromised antigens. Unlike the SRD assay, the ELISA assay in this manuscript specifically targets functional neutralizing epitopes critical for protective immunity. It offers a more refined assessment of antigenic quality, linking detoxification-induced structural changes to immunogenicity.

Additionally, many vaccine manufacturers prefer to use an ELISA, which is more efficient in quantifying PTx and evaluating the consistency of PTd preparations22-24. Given that the integrity of the natural structure of PTx is greatly destroyed by glutaraldehyde treatment, resulting in a significant loss of some critical neutralizing epitopes in S1, S2, and/or S3, contributing to the protection in vivo12,25,26. For assay purposes, it is more logical to analyze changes in neutralizing epitopes of PTx after detoxification, as this more accurately represents the actual antigenic changes of PTx.

5. Conclusion

To conclude, we established an in vitro assay that precisely reflects the antigenic changes of PTx post-glutaraldehyde detoxification. The antigenic properties of PTd preparations are closely related to immunogenicity. We also demonstrated that the assay is a potential alternative for monitoring the quality of PTx and PTd preparations in manufacturing high-quality acellular pertussis vaccines.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Determination of working range and assay detection limit for the S1 subunit; Figure S2: Determination of working range and assay detection limit for the S2/3 subunit; Figure S3: Effect of glutaraldehyde inactivation on neutralizing epitopes in S1 and S2/3 subunit (supplementary data).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W. and W.W.; methodology, X.W., X.C., C.W. and K.T.; software, X.W., X.C., and C.W.; validation, X.W., X.C., C.W. and K.T.; formal analysis, X.W., X.C. and C.W.; investigation, C.W., X.W., X.C. and W.W.; resources, W.W. and S.P.; data curation, X.W., X.C., C.W., and K.T.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W. and W.W.; writing—review and editing, W.W. and S.P. visualization, C.W.; supervision, W.W. and S.P.; project administration, W.W. and S.P.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by China National Biotech Group Co., ltd, Sinopharm, grant number KTZC1200006B.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Additional data will be made available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Yu Ma, Shi-hui Li, Yue-xia Liang, Na Zhang, Han-zhang Tao, Ying-jie Wang and Xin-shuo Zhu for technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors Xi Wang, Chong-yang Wu, Xin-yue Cui, Ke Tao, Wen-ming Wei and Shu-yuan Pan are employed by Beijing Institute of Biological Products Co., ltd; Additionally, Shu-yuan Pan has received funding support from China National Biotech Group Co., ltd.

Biographical note for the Corresponding Author

Wenming WEI, Ph.D., Associate Researcher, group leader. Wenming WEI is an associate researcher at Beijing Institute of Biological Products Co., Ltd (BIBP), Sinopharm. He is also the head of the lab for novel bacterial vaccine research and development. He was recruited to Pasteur-Paris University International doctoral program (PPU) from 2017 to 2020. He has worked in vaccine research and development for more than ten years. Since 2023, he has set up his group at BIBP. Over the past two years, he and his group members have dedicated themselves to chemically detoxifying pertussis toxin and characterizing pertussis toxoid to develop a high-quality acellular pertussis vaccine. They were also actively developing novel vaccines against bacterial pathogens such as Bordetella pertussis and Neisseria meningitidis based on genetically modified bacteria strains and outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) technology platform.

References

- Esposito S, Stefanelli P, Fry NK, Fedele G, He QS, Paterson P, Tan T, Knuf M, Rodrigo C, Olivier CW, et al. Pertussis Prevention: Reasons for Resurgence, and Differences in the Current Acellular Pertussis Vaccines. Front Immunol. 2019;10: 1344. [CrossRef]

- Gregg KA, Merkel TJ. Pertussis Toxin: A Key Component in Pertussis Vaccines? Toxins.2019;11(10). [CrossRef]

- Biggelaar VD, A. H. J., Poolman AHJ, Jan T. Predicting future trends in the burden of pertussis in the 21st century: implications for infant pertussis and the success of maternal immunization. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2016;15(1): 69-80. [CrossRef]

- Habeeb A, Hiramoto R. Reaction of proteins with glutaraldehyde. Arch Biochem Biophys.1968; 126(1): 16-26. [CrossRef]

- Richards F, Knowles JR. Glutaraldehyde as a protein cross-linking reagent. JMol Bid. 1968; 37: 231–233.

- Goldsmith JA, Nguyen AW, Wilen RE, Wijagkanalan W, McLellan JS, Maynard JA. Structural Basis for Antibody Neutralization of Pertussis Toxin. bioRxiv. 2024; [CrossRef]

- Hokyun Oh, Kim BG, Nam KT, Hong SH, Ahn DH, Choi GS, Kim H, Hong JT, Ahn BY. Characterization of the carbohydrate binding and ADP-ribosyltransferase activi-ties of chemically detoxified pertussis toxins. Vaccine. 2013; 31(29): 2988-2993. [CrossRef]

- Yuen C, Asokanathan C, Cook S. Effect of different detoxification procedures on the residual pertussis toxin activities in vaccines. Vaccine. 2016; 34(18): 2129-2134. [CrossRef]

- Knuutila A, Dalby T, Barkoff AM, Jorgensen CS, Fuursted K, Mertsola J, Markey K, He QS. Differences in epitope-specific antibodies to pertussis toxin after infection and acellular vaccinations. Clinical & Translational Immunology. 2020; 9: e1161. [CrossRef]

- Seubert A, D’Oro U, Scarselli M, Pizza M. Genetically detoxified pertussis toxin (PT-9K/129G): implications for immunization and vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014; 13(10): 1191-1204. [CrossRef]

- Ibsen P. The effect of formaldehyde, hydrogen peroxide and genetic detoxification of pertussis toxin on epitope recognition by murine monoclonal antibodies. Vaccine. 1996; 14(5): 359-368. [CrossRef]

- Sato H, Sato Y. Relationship between structure and biological and protective activities of pertussis toxin. Dev Biol Stand. 1991; 73: 121-132.

- Sutherland J, Maynard JA. Characterization of a key neutralizing epitope on pertussis toxin recognized by monoclonal antibody 1B7. Biochemistry. 2009; 48(50): 11982-11993. [CrossRef]

- Wagner E, Wang X, Bui A, Maynard JA. Synergistic Neutralization of Pertussis Toxin by a Bispecific Antibody In Vitro and In Vivo. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2016; 23(11): 851-862. [CrossRef]

- Sato H, Sato Y, Ohishi I. Comparison of Pertussis Toxin (PT)-Neutralizing Activities and Mouse-Protective Activities of Anti-PT Mouse Monoclonal Antibodies. Infection and immunity. 1991, p. 3832-3835.

- Sato H, Sato Y. Protective Activities in Mice of Monoclonal Antibodies against Pertussis Toxin. Infection and immunity. 1990, p. 3369-3374.

- Tan L, Fahim RE, Jackson G, Phillips K, Wah P, Alkema D, Zobrist G, Herbert A, Boux L, Chong P. A novel process for preparing an acellular pertussis vaccine composed of non-pyrogenic toxoids of pertussis toxin and filamentous hemagglutinin. Mol Immunol. 1991 ; 28(3) : 251-255. [CrossRef]

- Wu CY; Wang X, Zhou Y, Zhu XS, Ma Y, Wei WM, Zhang YT. Development and Implementation of a Single Radial Diffusion Technique for Quality Control of Acellular Pertussis Vaccines. Vaccines. 2025; 13, 116. [CrossRef]

- Winsnes R, Sesardic D, Daas A, Terao E, Behr-Gross M. Collaborative study on a Guinea pig serological method for the assay of acellu-lar pertussis vaccines. Pharmeur Bio Sci Notes. 2009 ; 1109(1) : 27-40. PMID: 20144450.

- Zhang YT, Guo YC, Dong Y, Liu YW, Zhao YX, Yu SZ, Li SH, Wu CY, Yang BF, Li WL, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a combined DTacP-sIPV-Hib vaccine in animal models. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2005; 18(7): 2160158. [CrossRef]

- Schild GC, Wood JM, Newman RW. A single radial immunodiffusion technique for the assay of influenza hemagglutinin antigen: Proposals for an assay method for the haemagglutinin content of influenza vaccines. Bull WHO. 1975; 52, 223–231. PMID: 816480.

- Aydin S, Emre E, Ugur K, Aydin MA, Sahin B, Cinar V, Akbulut T. An overview of ELISA: a review and update on best laboratory practices for quantifying peptides and proteins in biological fluids. J Int Med Res. 2025; 53(2). [CrossRef]

- Waritani T, Chang J, McKinney B, Terato K. An ELISA protocol to improve the accuracy and reliability of serological antibody assays. MethodsX. 2017; 4:153-165. [CrossRef]

- Alhajj M, Zubair M, Farhana A. Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2025; Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK555922/.

- Arciniega J, Shahin RD, Burnette WN, Bartley TD, Burns D. Contribution of the B oligomer to the protective activity of genetically attenuated pertussis toxin. Infect Immun. 1991 ; 59(10). [CrossRef]

- Sutherland J, Chang C, Yoder SM, Rock MT, Maynard JA. Antibodies Recognizing Protective Pertussis Toxin Epitopes Are Preferentially Elicited by Natural Infection versus Acellular Immunization. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 2011; 18(6): 954-962. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).