Submitted:

16 December 2024

Posted:

17 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

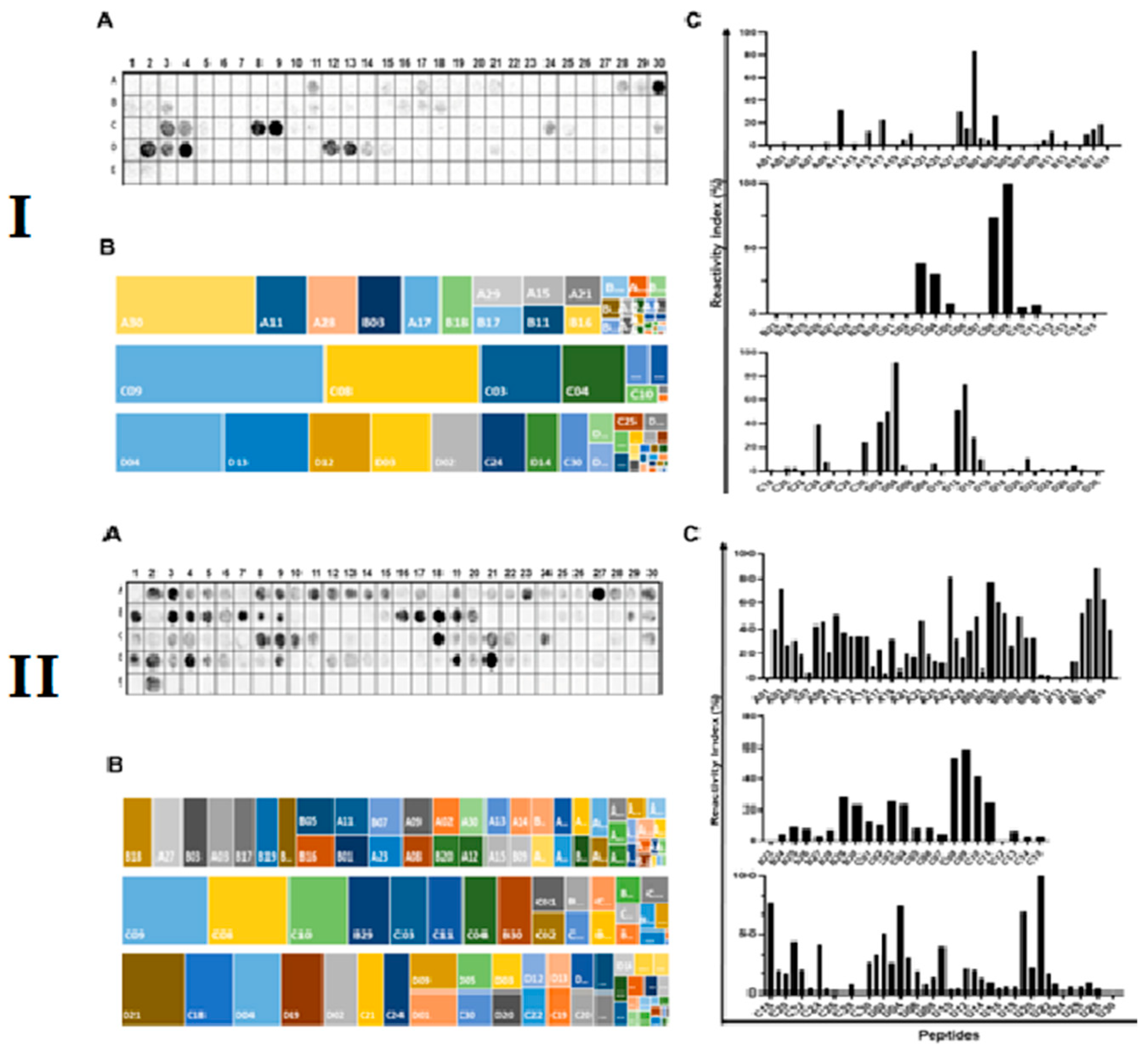

2.1. Identification of the Immunodominant IgA and IgM Epitopes in Cholera Toxin Subunits

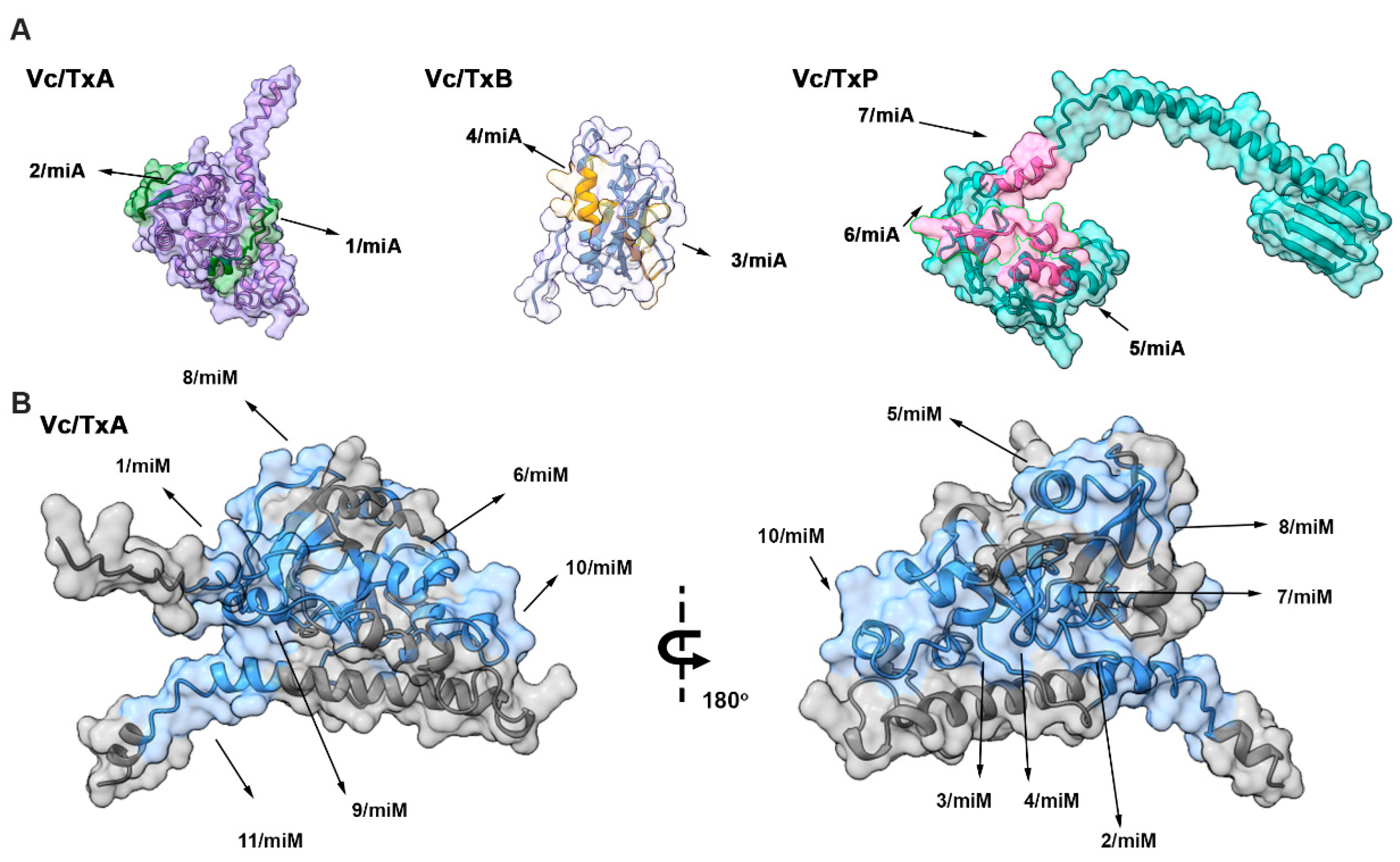

2.2. Spatial Localization of the Major IgA and IgM Epitopes Within the Three Chain of the Toxin

2.3. Spatial Distribution of the Reactive Epitopes of Enterotoxin A, B, and P

2.4. Specific and Cross-Immune IgA and IgM Epitopes

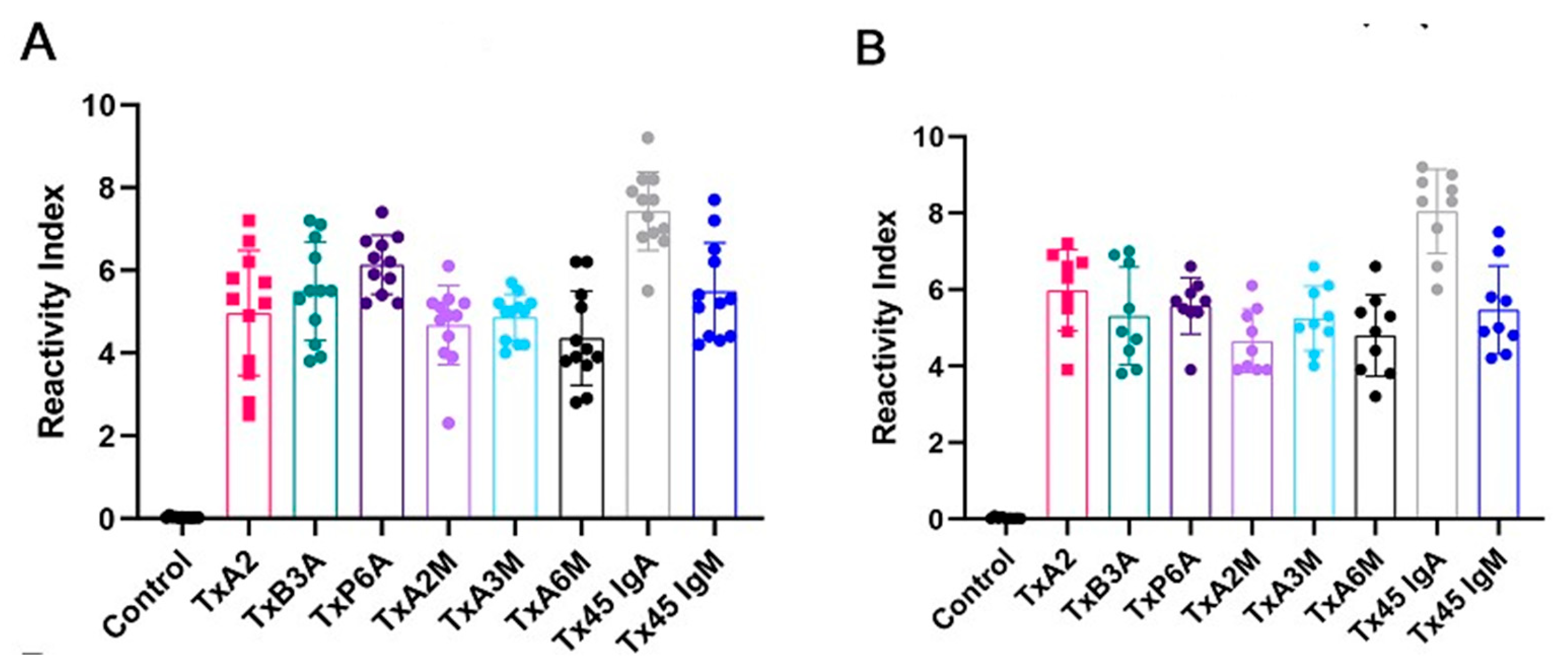

2.5. Reactivity of MAP4 and Chimeric Peptides via ELISA

3. Discussion

4. Conclusions

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Immunization of Mice

5.2. Synthesis of the Cellulose Membrane-Bound Peptide Array

5.3. Screening of SPOT Membranes

5.4. Scanning and Measurement of Spot Signal Intensities

5.5. Preparation of Single and Multi-Antigen Peptides (MAPs)

5.6. Preparation of 45-mer Chimeric Peptides

5.7. In House ELISA

5.8. Structural Localization of IgG Epitopes and Bioinformatics Tools

5.9. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, M.; Nelson, A.R.; Lopez, A.L. ; Sack, DA Updated global burden of cholera in endemic countries. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015, 9, e0003832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuki, Y.; Nojima., M.; Hosono, O.; Tanaka, H.; Kimura, Y.; Satoh, T.; Imoto, S.; Uematsu, S.; Kurokawa, S.; Kashima, K.; et al. Oral MucoRice-CTB vaccine for safety and microbiota-dependent immunogenicity in humans: A phase 1 randomized trial. Lancet Microbe 2021, 2, e429–e440. [CrossRef]

- Vezzulli, L.; Grande, C.; Reid, P.C.; Hélaouët, P.; Edwards, M.; Höfle, M.G.; Brettar, I.; Colwell, R.R.; Pruzzo, C. Climate influence on vibrio and associated human diseases during the past half-century in the coastal North Atlantic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016, 113, E5062–E5071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeb, R.; Tufford, D.; Scott, G.I.; Moore, J.G.; Dow, K. Impact of climate change on Vibrio vulnificus abundance and exposure risk. Estuaries Coasts 2018, 41, 2289–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Austin, C.; Oliver, J.D.; Alam, M.; Ali, A.; Waldor, M.K.; Qadri, F.; Martinez-Urtaza, J. Vibrio spp. Infections. Nat Rev Dis Prim 2018, 4, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Legros, D. Legros, D.; Partners of the Global Task Force on Cholerae Control. Global cholerae epidemiology: Opportunities to reduce the burden of cholera by 2030. J Infect Dis 2018, 218, S137–S140; Erratum in J Infect Dis 2019, 219, 509. [CrossRef]

- WHO. Cholerae; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cholera? gadsource =1&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIqYXdh PW1hgMVgUVIAB0qbwipEAAYASAAEgJ 1CfD_BwE (Accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Banerjee, T.; Grabon, A.; Taylor, M.; Teter, K. cAMP-Independent activation of the unfolded protein response by cholera toxin. Infect Immun 2021, 89, e00447–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clemens, J.D.; Nair, G.B.; Ahmed, T.; Qadri, F.; Holmgren, J. Cholerae. Lancet 2017, 390, 1539–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourque, D.L.; Bhuiyan, T.R.; Genereux, D.P.; Rashu, R.; Ellis, C.N.; Chowdhury, F.; Khan, A.I.; Alam, N.H.; Paul, A.; Hossain, L.; et al. Analysis of the human mucosal response to cholerae reveals sustained activation of innate immune signaling pathways. Infect Immun 2018, 86, e00594–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.; Holmgren, J. Cholera toxin-a foe & a friend. Indian J. Med. Res. 2011, 133, 153. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, R.K.; Miller, V.L.; Furlong, D.B.; Mekalanos, J.J. Use of phoA gene fusions to identify a pilus colonization factor coordinately regulated with cholera toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci. USA 1987, 84, 2833–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldor, M.K.; Colwell, R.; Mekalanos, J.J. The Vibrio cholerae O139 serogroup antigen includes an O-antigen capsule and lipopolysaccharide virulence determinants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994, 91, 11388–11392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperandio, V.; Giron, J.A.; Silveira, W.D.; Kaper, J.B. The OmpU outer membrane protein, a potential adherence factor of Vibrio cholerae. Infect Immun 1995, 63, 4433–4438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, D.K.; Sengupta, T.K.; Ghose, A.C. Major outer membrane proteins of Vibrio cholerae and their role in induction of protective immunity through inhibition of intestinal colonization. Infect Immun 1992, 60, 4848–4855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, B.; Nandy, R.K.; Sarkar, A.; Ghose, A.C. Structural features, properties, and regulation of the outer-membrane protein W (OmpW) of Vibrio cholerae. Microbiology 2005, 151, 2975–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadri, F.; Ali, M.; Chowdhury, F.; Khan, A.I.; Saha, A.; Khan, I.A.; Begum, Y.A.; Bhuiyan, T.R.; Chowdhury, M.I.; Uddin, M.J.; et al. Feasibility and effectiveness of oral cholerae vaccine in an urban endemic setting in Bangladesh: A cluster randomized open-label trial. Lancet 2015, 386, 1362–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi, Q.; Ferreras, E.; Pezzoli, L.; Legros, D.; Ivers, L.C.; Date, K.; Qadri, F.; Digilio, L.; Sack, D.A.; Ali, M.; et al. Protection against cholera from killed whole-cell oral cholerae vaccines: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral cholerae vaccine working group of the global task force on cholerae control. Lancet Infect Dis 2017, 17, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peak, CM; Reilly, A.L.; Azman, AS; Buckee, C.O. Prolonging herd immunity to cholerae via vaccination: Accounting for human mobility and waning vaccine effects. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018, 12, e0006257. [CrossRef]

- Royal, J.M.; Reeves, M.A.; Matoba, N. Repeated oral administration of a KDEL-tagged recombinant cholerae toxin B subunit effectively mitigates DSS colitis despite a robust immunogenic response. Toxins 2019, 11, 678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, S. Critical analysis of compositions and protective efficacies of oral killed cholera vaccines. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2014, 21, 1195–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; Cohen, M.B.; Kirkpatrick, B.D.; Brady, R.C.; Galloway, D.; Gurwith, M.; Hall, R.H.; Kessler, R.A.; Lock, M.; Haney, D.; et al. Single-dose live oral cholera vaccine CVD 103-HgR protects against human experimental infection with Vibrio cholerae El Tor. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 1329–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmgren, J.J. Modern history of cholera vaccines and the pivotal role of ICDDR. Infect Dis 2021, 224, S742–S748. [CrossRef]

- Wierzba, T.F. Oral cholera vaccines and their impact on the global burden of disease. Hum Vaccines Immunother 2019, 15, 1294–1301. 2019; 15, 1294–1301. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qadri, F.; Chowdhury, M.I.; Faruque, S.M.; Salam, M.A.; Ahmed, T.; Begum, Y.A.; Saha, A.; Al Tarique, A.; Seidlein, L.V.; Park, E.; et al. PXV Study Group, Peru-15, a live attenuated oral cholera vaccine, is safe and immunogenic in Bangladeshi toddlers and infants. Vaccine 2007, 25, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.I.; Islam, M.T.; Khan, Z.H.; Tanvir, N.A.; Amin, M.A.; Khan, I.I.; Bhuiyan, A.T.M.R.H.; Hasan, A.S.M.M.; Islam, M.S.; 0 Bari, T.I.A.; et al. Implementation and delivery of oral cholera vaccination campaigns in humanitarian crisis settings among Rohingya Myanmar nationals in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, KR; Lim, J.K.; Park, S.E.; Saluja, T.; Cho, S.I.; Wartel, T.A.; Lynch, J. Oral cholera vaccine efficacy and effectiveness. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1482. [CrossRef]

- Bi, Q.; Ferreras, E.; Pezzoli, L.; Legros, D.; Ivers, L.C.; Date, K.; Qadri, F.; Digilio, L.; Sack, DA; Ali, M.; et al. Oral cholerae vaccine working group of the global task force on cholerae control. Protection against cholerae from killed whole-cell oral cholerae vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2017, 17, 1080–1088. [CrossRef]

- Koelle, K.; Rodo, X.; Pascual, M.; Yunus, M.; Mostafa, G. Refractory periods and climate forcing in cholerae dynamics. Nature 2005, 436, 696–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatib, A.M.; Ali, M.; von Seidlein, L.; Kim, D.R.; Hashim, R.; Reyburn, R.; Ley, B.; Thriemer, K.; Enwere, G.; Hutubessy, R.; et al. Effectiveness of an oral cholerae vaccine in Zanzibar: Findings from a mass vaccination campaign and observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2012, 1, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmgren, J. An update on cholerae immunity and current and future cholerae vaccines. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.; Sur, D.; You, Y.A.; Kanungo, S.; Sah, B.; Manna, B.; Puri, M.; Wierzba, T.F.; Donner, A.; Nair, G.B.; et al. Herd protection by a bivalent killed whole-cell oral cholerae vaccine in the slums of Kolkata, India. Clin Infect Dis 2013, 56, 1123–1131. [CrossRef]

- Naidu, A.; Lulu, S.S. Mucosal and systemic immune responses to Vibrio cholerae infection and oral cholerae vaccines (OCVs) in humans: a systematic review. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2022, 18, 1307–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanungo, S.; Azman, AS; Ramamurthy, T.; Deen, J.; Dutta, S. Cholerae. Lancet 2022, 399, 1429–1440. [CrossRef]

- De-Simone, S.G.; Napoleão-Pêgo, P.; Gonçalves, P.S.; Provance-Jr, D.W.; Morel, C.M.; Silva, F.R. B Cell epitope mapping of the Vibrio cholerae toxins A, B and P. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, D.F.H. Automated solid-phase peptide synthesis. Methods Mol Biol 2020, 2103, 59–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prim, D.; Rebeaud, F.; Cosandey, V.; Marti, R.; Passeraub, P.; Pfeifer, M.E. ADIBO-based "click" chemistry for diagnostic peptide micro-array fabrication: physicochemical and assay characteristics. Molecules 2013, 18, 9833–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinkhasov, J.; Alvarez, M.L.; Pathangey, L.B.; Tinder, TL; Mason, H.S.; Walmsley, A.M.; Gendler, S.J.; Mukherjee, P. Analysis of a cholerae toxin B subunit (CTB) and human mucin 1 (MUC1) conjugate protein in a MUC1-tolerant mouse model. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2010, 59, 1801–1811. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.; Holmgren, J. Cholerae toxin structure, gene regulation, and pathophysiological and immunological aspects. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 1347–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharati, K.; Ganguly, N.K. Cholerae toxin: A paradigm of a multifunctional protein. Indian J. Med. Res. 2011, 133, 179. [Google Scholar]

- Sikora, A.E. Proteins secreted via the type II secretion system: Smart strategies of Vibrio cholerae to maintain fitness in different ecological niches. PLoS Pathog 2013, 9, e1003126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekalanos, J.; Collier, R.; Romig, W. Enzymic activity of cholerae toxin. II. Relationships to proteolytic processing, disulfide bond reduction, and subunit composition. J. Biol. Chem. 1979, 254, 5855–5861. [CrossRef]

- Mayo, S.; Royo, F.; Hau, J. Correlation between adjuvanticity and immunogenicity of cholerae toxin B subunit in orally immunized young chickens. APMIS 2005, 113, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, GA; Holmes, R.K. Evaluation of TcpF-A2-CTB chimera and evidence of additive protective efficacy of immunizing with TcpF and CTB in the suckling mouse model of cholerae. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42434. [CrossRef]

- Adachi, M.; Kurihara, Y.; Nojima, H.; Takeda-Shitaka, M.; Kamiya, K.; Umeyama, H. Interaction between the antigen and antibody is controlled by the constant domains: normal mode dynamics of the HEL-HyHEL-10 complex. Protein Sci. 2003, 12, 2125–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Liu, Y.; Tao, R.; Hsi, J.; Shao, Y.; Wang, H. Cholerae Toxin B subunit acts as a potent systemic adjuvant for HIV-1 DNA vaccination intramuscularly in mice. Hum. Vaccines Immunother 2014, 10, 1274–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayo, S.; Royo, F.; Hau, J. Correlation between adjuvanticity and,immunogenicity of cholera toxin B subunit in orally immunized young chickens. APMIS 2005, 113, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyt, B.A.; Baliga, R.; Sinclair, A.M.; Carroll, S.F.; Peterson, M.S. Structure, function, and therapeutic use of IgM antibodies. Antibodies (Basel). 2020, 9, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Shen, H.; Zhang, R.; Ji, C.; Wang, Y.; Su, C.; Xiao, J. Immunoglobulin M perception by FcμR. Nature. 2023, 615, 907–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiramoto, E.; Tsutsumi, A.; Suzuki, R.; Matsuoka, S.; Arai, S.; Kikkawa, M.; Miyazaki, T. The IgM pentamer is an asymmetric pentagon with an open groove that binds the AIM protein. Sci Adv. 2018, 4, eaau1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Su C, Ji C, Xiao J. CD5L associates with IgM via the J chain. Nat Commun. 2024, 15, 8397. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Min, Q.; Xiong, E.; Heyman, B.; Wang, J.Y. Regulation of humoral immune responses and B cell tolerance by the IgM Fc R,eceptor (FcμR). Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020, 1254, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De-Simone, S.G.; Napoleão-Pêgo, P.; Gonçalves, P.S.; Lechuga, G.C.; Cardoso, S.V.; Provance, D.W. Jr.; Morel, C.M.; da Silva, F.R. B-Cell epitope mapping of the Vibrio cholera Toxins A, B, and P and an ELISA assay. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 24, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casadevall, A.; Janda, A. Immunoglobulin isotype influences affinity and specificity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2012, 109, 12272–12273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayeed, M.A.; Islam, K.; Hossain, M.; Akter, N.J.; Alam, M.N.; Sultana, N.; Khanam, F.; Kelly, M.; Charles, R.C.; Kováč, P.; et al. Development of a new dipstick (Cholkit) for rapid detection of Vibrio cholerae O1 in acute watery diarrheal stools. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018, 12, e0006286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heyman, B.; Shulman, M.J. in Encyclopedia of Immunobiology (ed. DeFranco A.L and Ratcliffe, M.J.H.) 2016, p1–14. Academic Press, ISBN 012374282X, 9780123742827.

- Li, Y.; Shen, H.; Zhang, R.; Ji, C.; Wang, Y.; Su, C.; Xiao, J. Immunoglobulin M perception by FcμR. Nature 2023, 615, 907–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Min, Q.; Xiong, E.; Heyman, B.; Wang, J.Y.; Liu, J. Regulation of Humoral Immune Responses and B Cell Tolerance by the IgM Fc Receptor (FcμR). Adv Exp Med Biol 2020, 1254, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Simone, S.G.; Gomes, L.R.; Napoleão-Pêgo, P.; Lechuga, G.C.; Pina, J.C.; Silva, F.R. Identification of linear B epitopes liable for the protective immunity of diphtheria toxin. Vaccines 2021, 9, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzembo, B.; Kitahara, K.; Ohno, A.; Debnath, A.; Okamoto, K.; Miyoshi, S.I. Cholerae rapid diagnostic tests for the detection of Vibrio cholerae O1: An updated meta-analysis. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021, 11, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzembo, B.A.; Kitahara, K.; Debnath, A.; Okamoto, K.; Miyoshi, S.I. Accuracy of cholera rapid diagnostic tests: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022, 28, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, E.J.; Grembi, J.A.; Chao, D.L.; Andrews, J.R.; Alexandrova, L.; Rodriguez, P.H.; Ramachandran, V.V.; Sayeed, MA; Wamala, J.F.; Debes, A.K.; et al. Gold standard cholera diagnostics are tarnished by lytic bacteriophage and antibiotics. J Clin Microbiol 2020, 58. e00412-20. [CrossRef]

- Ramamurthy, T.; Das, B.; Chakraborty, S.; Mukhopadhyay, A.K.; Sack, DA Diagnostic techniques for rapidly detecting Vibrio cholerae O1/O139. Vaccine. 2020, 38, A73-A82. [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Velagic, M.; Connor, S. Development of a simple, rapid, and sensitive molecular diagnostic assay for cholera. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023, 17, e0011113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareitaher, T.; Sadat, T.; Seyed, AS; Gargari, L.M. Immunogenic efficacy of DNA and protein-based vaccine from a chimeric gene consisting of OmpW, TcpA, and CtxB, of Vibrio cholerae. Immunobiology 2022, 227, 152190. [CrossRef]

- Zereen, F.; Akter, S.; Sobur, M.A.; Hossain, M.T.; Rahman, M.T. Molecular detection of Vibrio cholerae from human stool collected from SK Hospital, Mymensingh, and their antibiogram. J Adv Vet Anim Res. 2019, 6, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, S.; Velagic, M.; Connor, S. Development of a simple, rapid, and sensitive molecular diagnostic assay for cholera. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023, 17, e0011113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, M.; Nelson, A.R.; Lopez, A.L.; Sack, D.A. Updated global burden of cholera in endemic countries. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015, 9, e0003832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pezzoli, L. Oral cholera vaccine working group of the global task force on cholera control. Global oral cholera vaccine use, 2013-2018. Vaccine 2020, 38 Suppl 1, A132-A140. [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.R.; Napoleão-Pêgo, P.; De-Simone, S.G. Identification of linear B epitopes of pertactin of Bordetella pertussis induced by immunization with whole and acellular vaccine. Vaccine 2014, 32, 6251–6258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De-Simone, S.G.; Napoleão-Pêgo, P.; Lechuga, G.C.; Carvalho, J.P.R.S.; Gomes, L.R.; Cardoso, S.V.; Morel, C.M.; Provance-Jr, D.W.; Silva, F.R.S. High-throughput IgG epitope mapping of tetanus neurotoxin: implications for immunotherapy and vaccine design. Toxins 2023, 15, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutsinas, G.; Shuaib, C.; Guo, W.; Jarvis, S. Graph hierarchy: a novel framework to analyze hierarchical structures in complex networks. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 13943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De-Simone, S.; Souza, A.L.A.; Melgarejo, A.R.; Aguiar, A.S.; Provance, D.W., Jr. Development of elisa assay to detect specific human IgE anti-therapeutic horse sera. Toxicon 2017, 138, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.; Kucukural, A.; Zhang, Y. I-TASSER: A unified platform for automated protein structure and function prediction. Nat. Protoc 2010, 5, 725–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evansm, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Protein Code | Code | aa | Sequence | 2nd Structure * | Peptide Search ** |

| P01555 | TxA-1A | 51 | RGTQMNINLYDHARG | C | E. coli |

| TxA-2A | 146-160 | YRVHFGVLDEQLHRN | C | Sp | |

| P01556 | TxB-3A | 66-75 | REMAIITFKN | C+H | Sp |

| TxB-4A | 81-90 | SQKKAIERMK | H | E. coli | |

| P29485 | TxP-5A | 31-45 | KPERLIGTPSIIQT | C+H | Sp |

| TxP-6A | 81-90 | AIKRTRDFLN | C+H | Sp | |

| TxP-7A | 126-135 | QKKSVKERIK | C+H | Various bacteria | |

| P01555 | TxA-1M | 11-25 | FLSSFSYANDDKLYR | C | Various bacteria |

| TxA-2M | 41-50 | MPRGQSEYFD | C | Sp | |

| TxA-3M | 56-64 | NINLYDHAR | C+H | Sp | |

| TxA-4M | 71-80 | VRHDDGYVST | C | E. coli | |

| TxA-5M | 91-105 | GQTILSGHSTYYIYV | C+H | Various bacteria | |

| TxA-6M | 111-125 | NMFNVNDVLGAYSPH | C | Sp | |

| TxA-7M | 131-145 | VSALGGIPYSQIYGW | C | Various bacteria | |

| TxA-8M | 151-160 | GVLDEQLHRN | C | Sp | |

| TxA-9M | 171-185 | RGYRDRYYSNLDIAP | C | Sp | |

| TxA-10M | 191-205 | GLAGFPPEHRAWREE | C | Sp | |

| TxA-11M | 236-250 | VKRQIFSGYQSDIDT | C+H | Sp |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).