Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

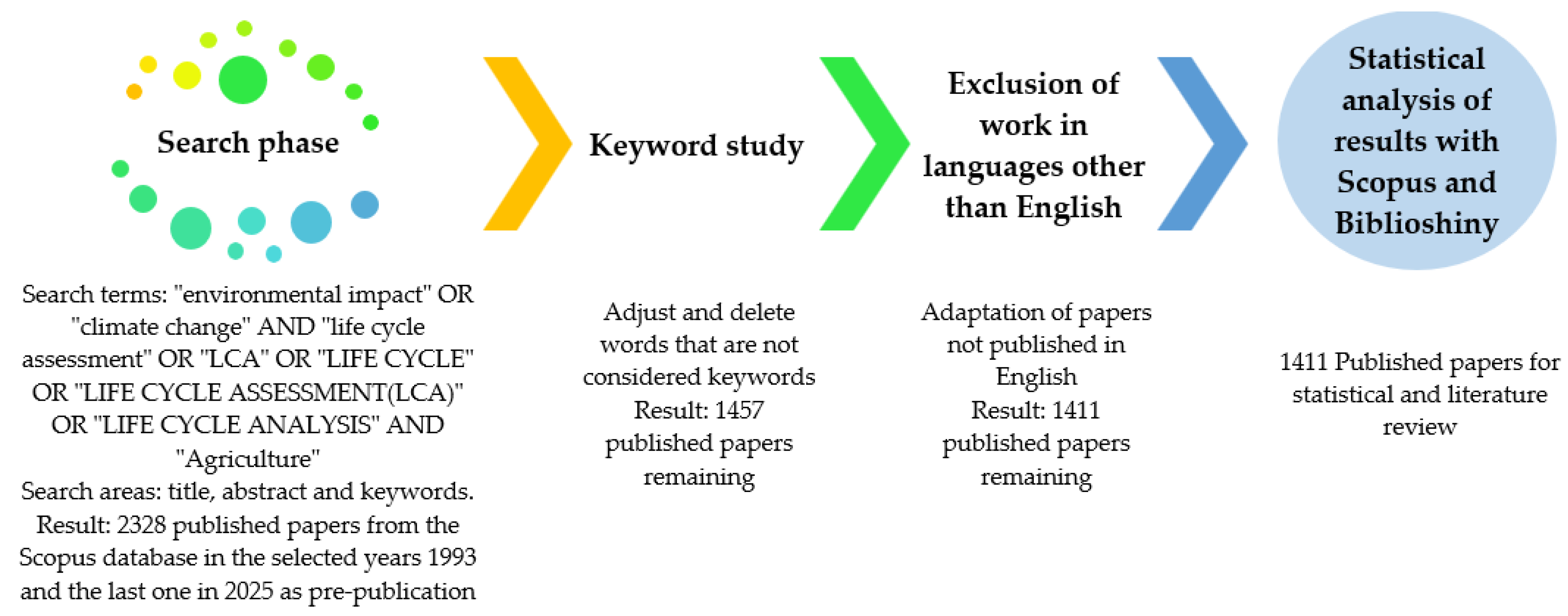

2. Materials and Methods

3. Reference Results

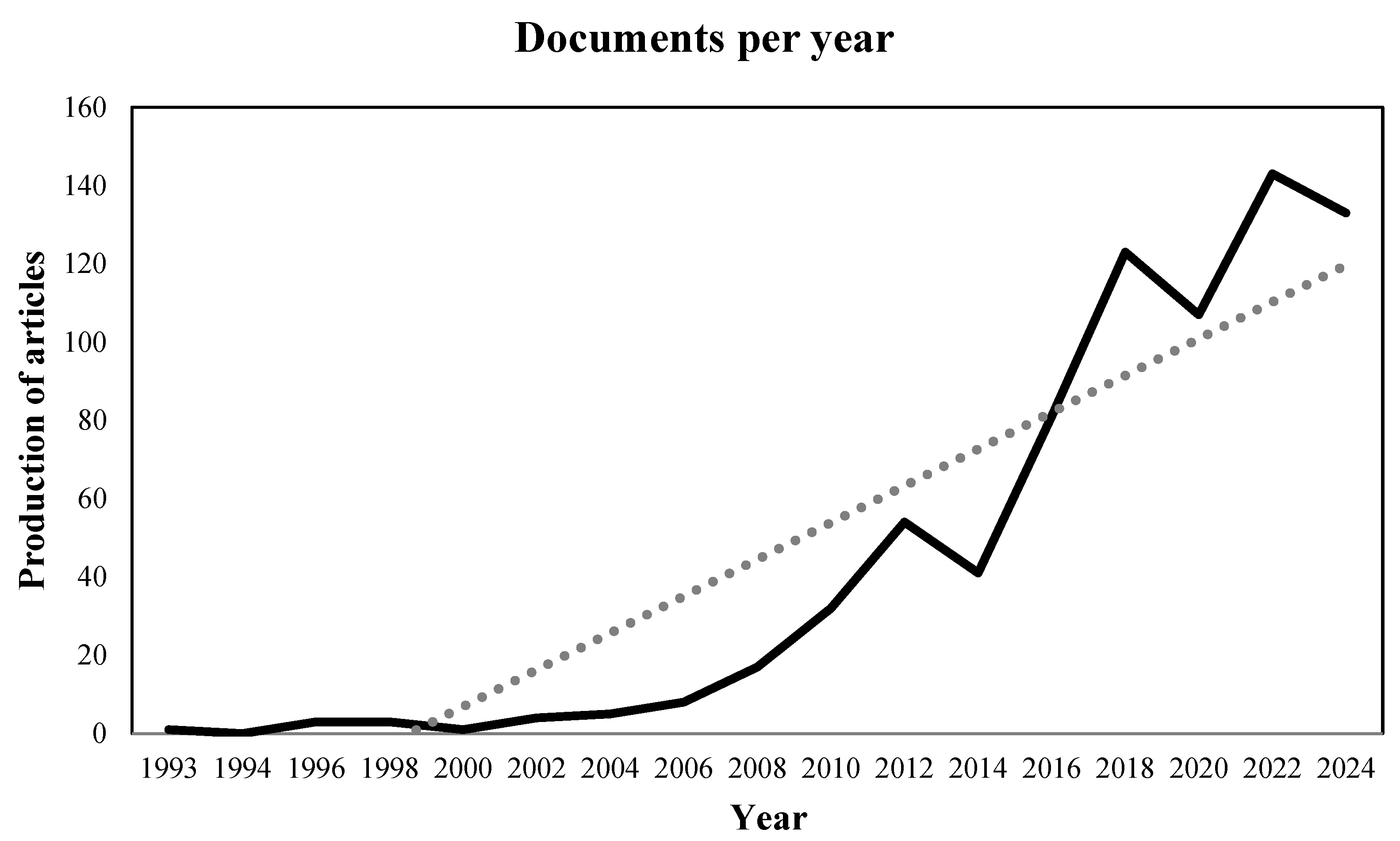

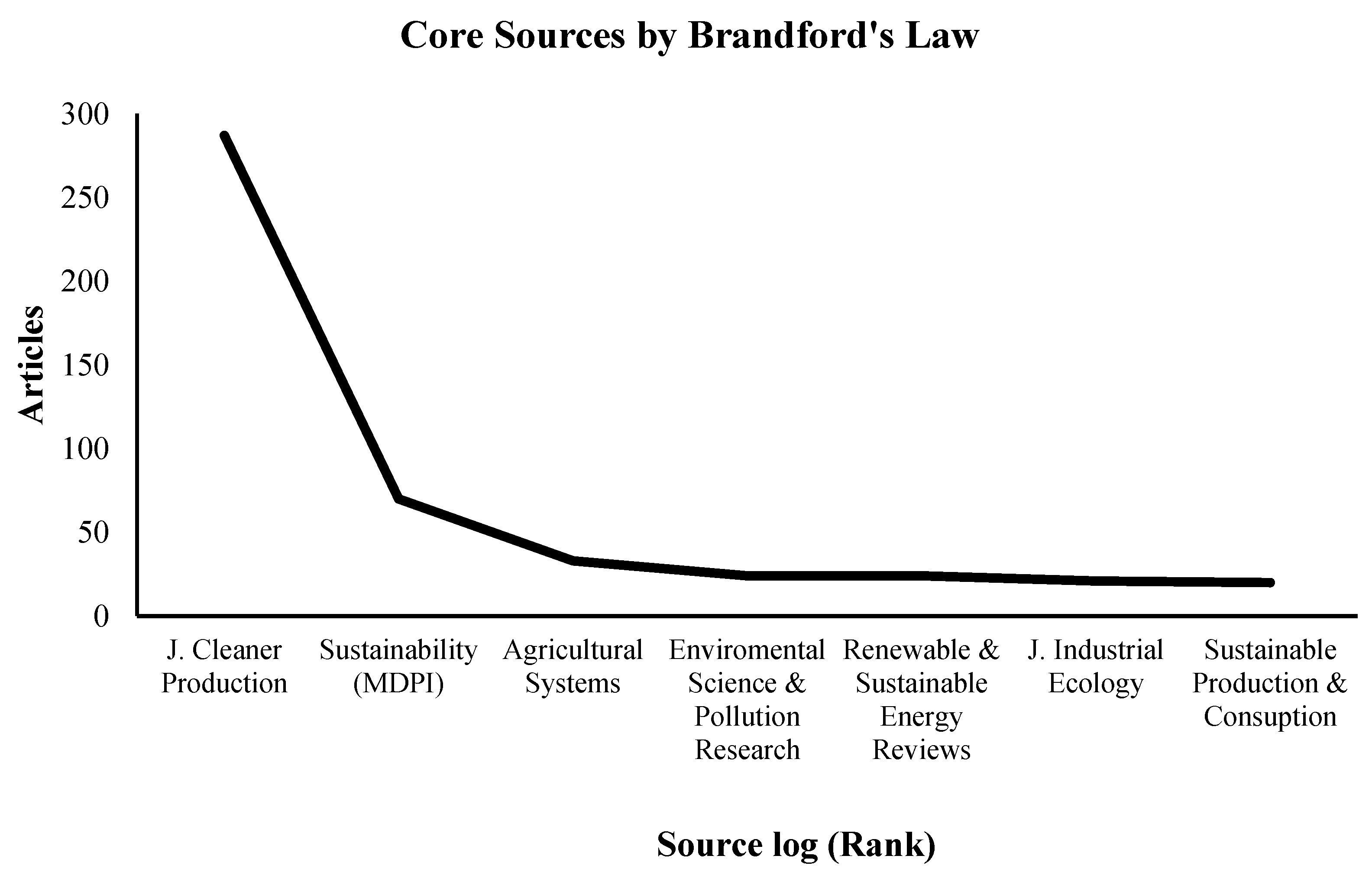

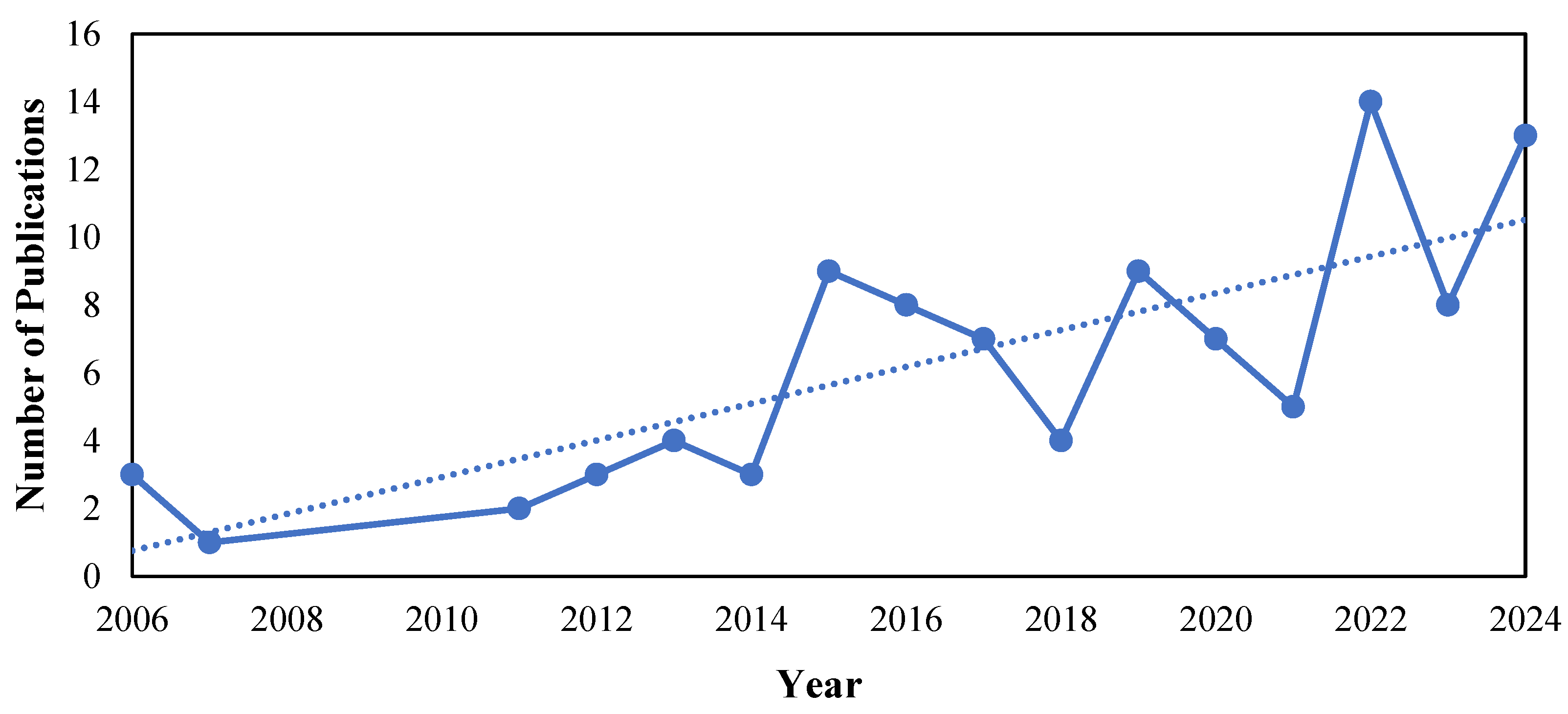

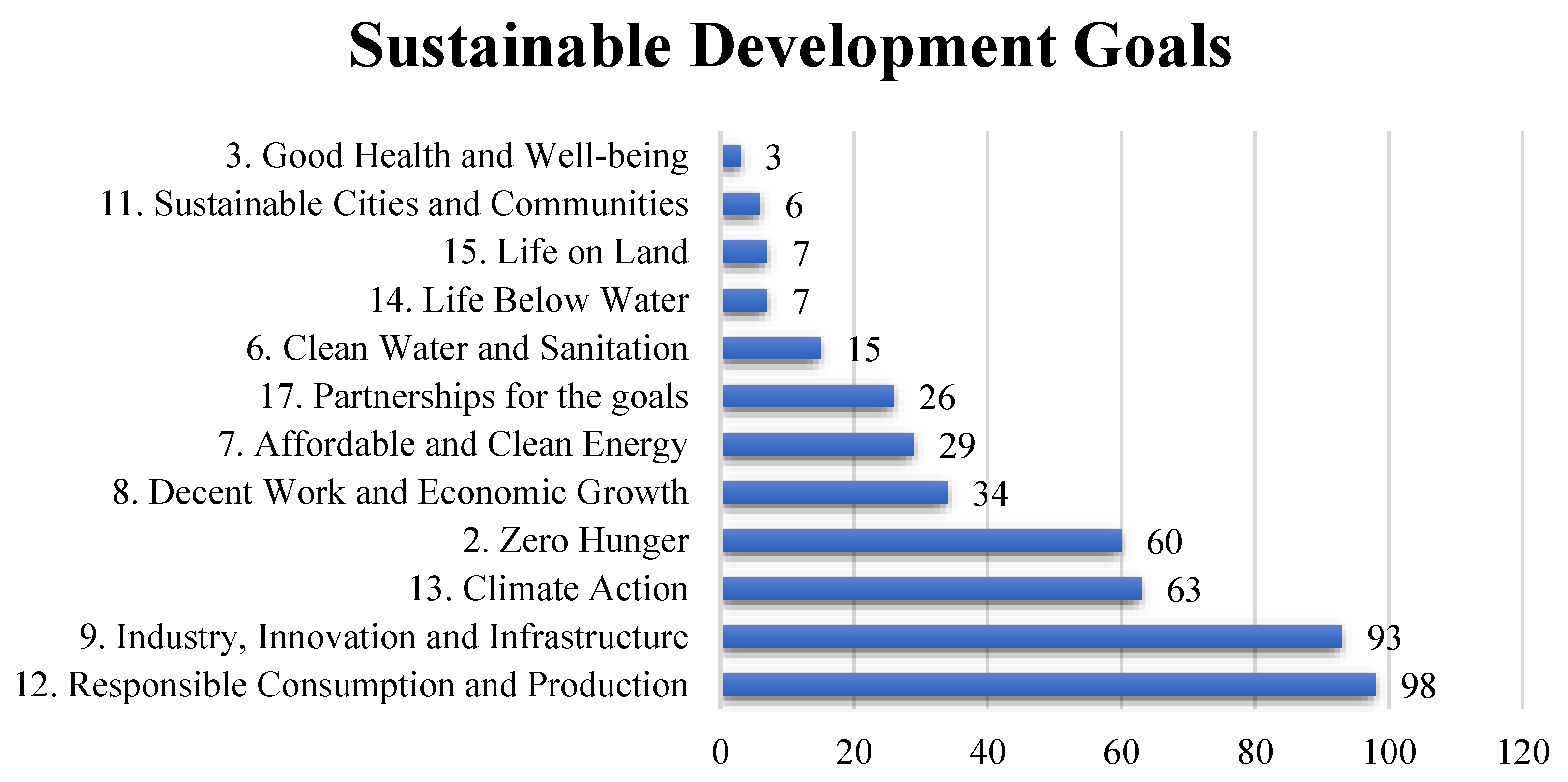

3.1. Bibliography Review

3.2. Narrative Review

4. Research Gaps and Proposal for Future Research

- Predominance of Static LCA Approaches: A significant portion (99%) of the analyzed studies rely on static LCA models, neglecting the inherent dynamism of agricultural systems and the temporal variability of key parameters, such as climate change impacts and evolving agricultural practices.

- Geographical Bias: The geographical scope of the existing literature exhibits a marked bias towards European and North American contexts (82% of studies), potentially limiting the applicability of findings to tropical and African agricultural systems.

- Limited Integration of Environmental and Economic Dimensions: Only a minority of studies (26%) integrate both environmental and economic indicators, thereby constraining the ability to formulate holistic policy recommendations.

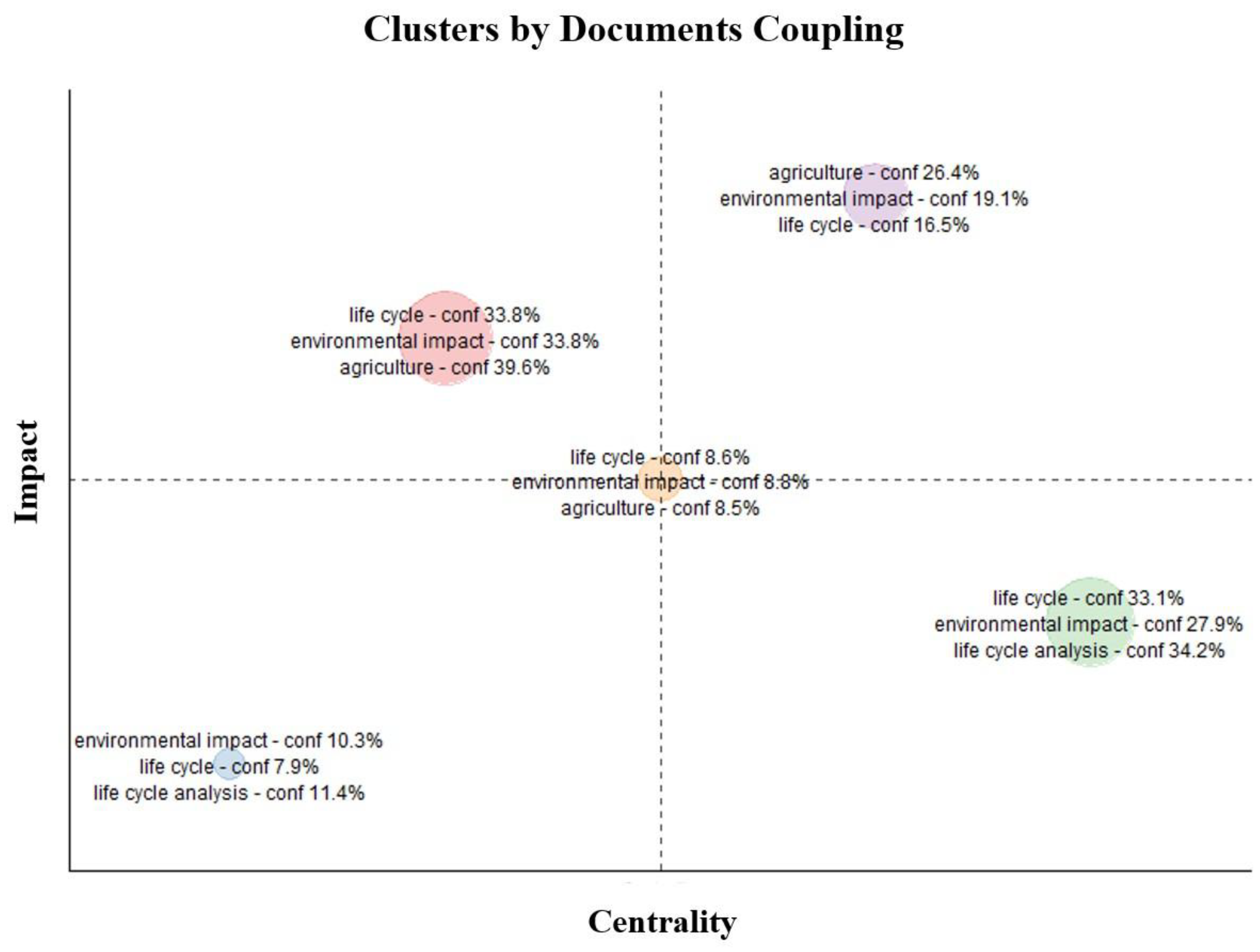

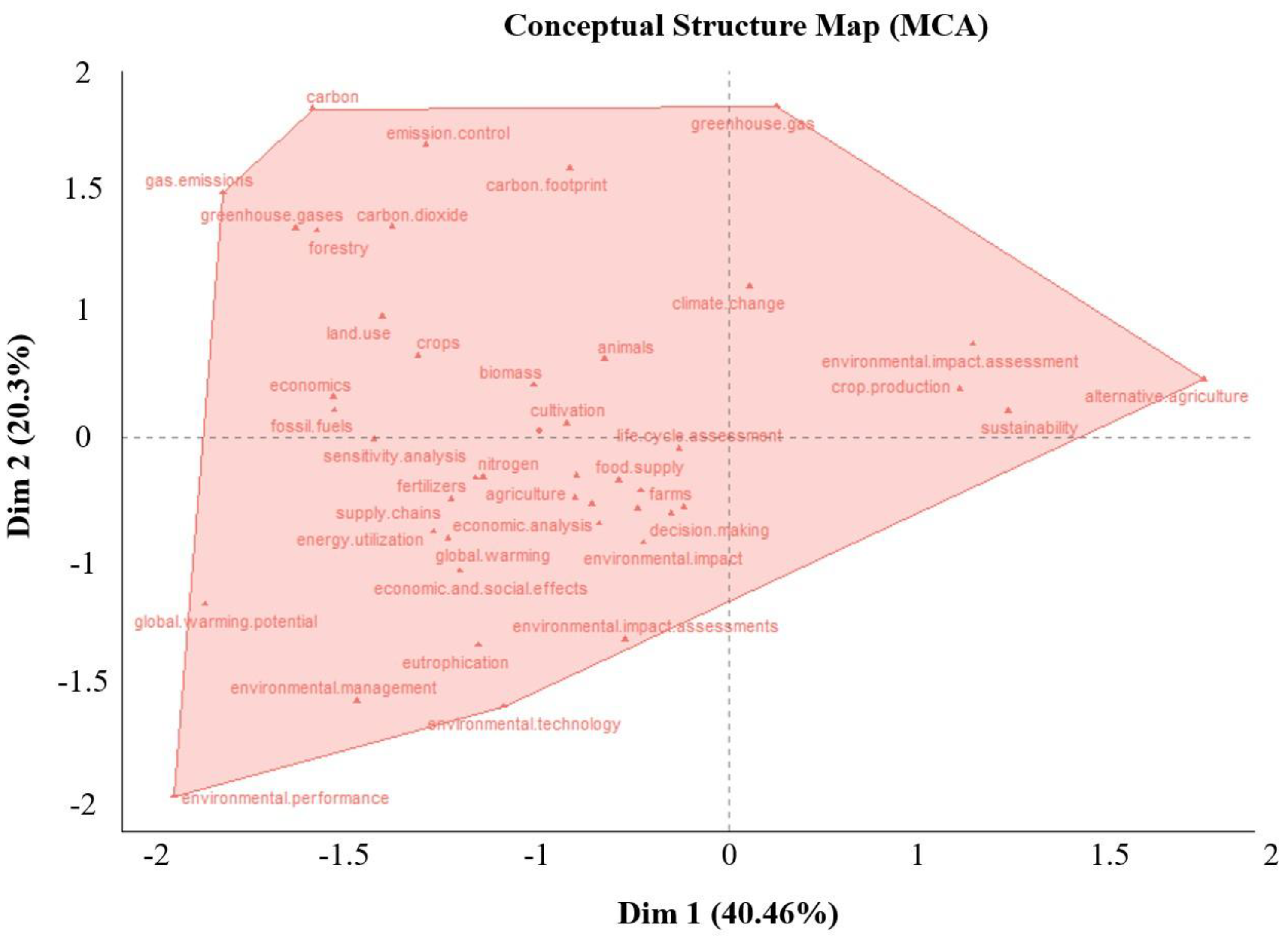

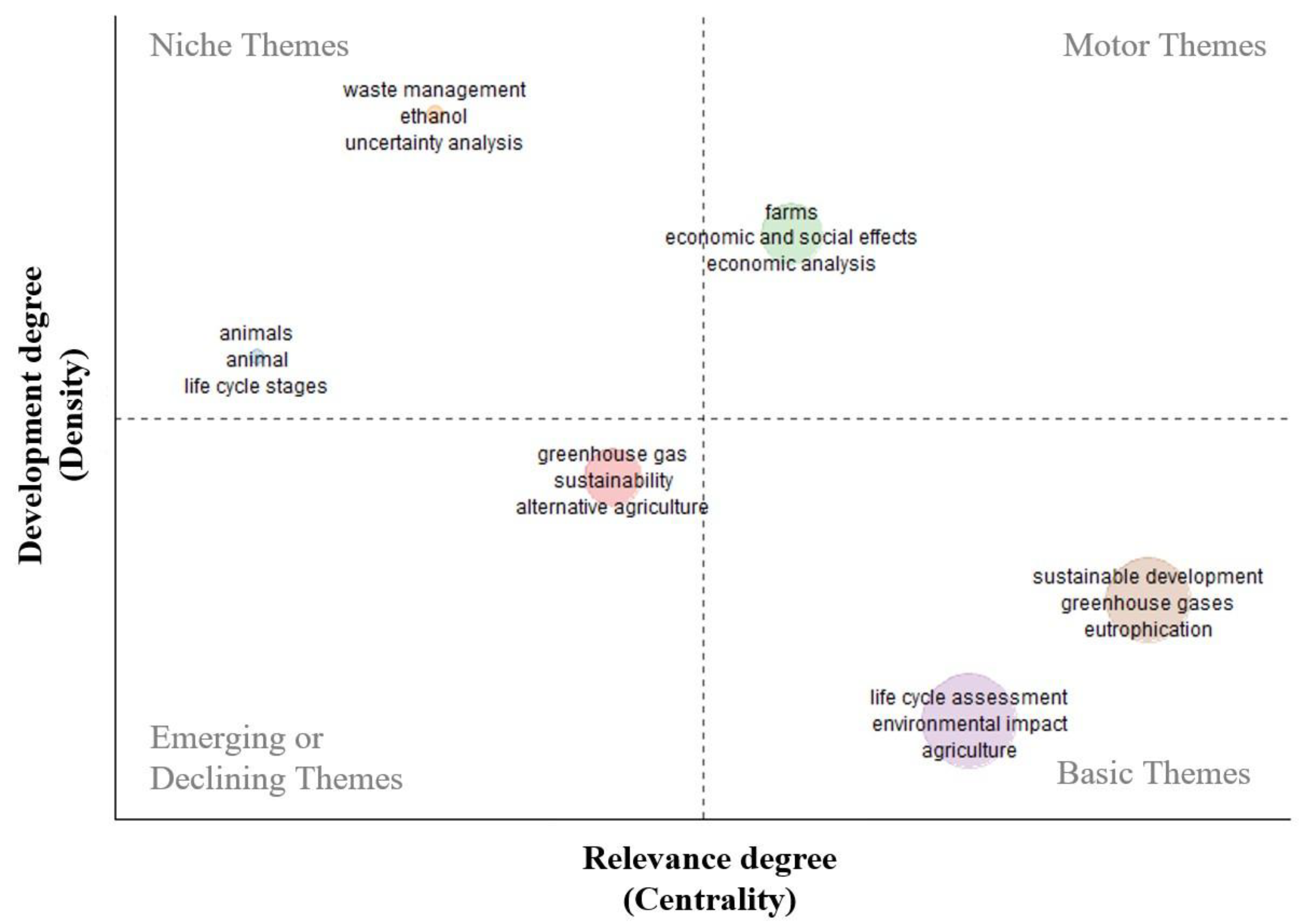

- The thematic map reveals Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) as a central concept in the assessment of environmental impacts and promotion of sustainability within the field.

- Analysis of the co-citation network identifies key researchers and influential publications that have shaped the field.

- The network of research collaborations indicates some dispersion between research groups, potentially suggesting specialization within different sub-areas of the field.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davoudi, S. Climate risk and security: new meanings of “the environment” in the English planning system. Eur Plan Stud. 2012, 21, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, C. A critical process analysis of wine production to improve cost efficiency, wine quality and environmental performance. 2003. p. 31–44. [CrossRef]

- Bastianoni, S.; Capasso, S.; Menna, F. Environmental and economic sustainability. In Morata, A.; López, C. Wine Safety, Consumer Preference, Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 73–83. [Google Scholar]

- Altieri, M.A.; et al. Agroecology and the design of climate change-resilient farming systems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 869–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, T.; Fujimori, S.; Shin, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Masui, T.; Tanaka, A. Impacts of land use, population, and climate change on global food security. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 775–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sygkollitou, E. Environmental Psychology (in Greek). Athens: Ellinika Grammata, 1997.

- Martinez-Blanco, J.M.; Antón, A.; Rieradevall, J.; Castellari, M.; Muñoz, P. Comparing nutritional value and yield as functional units in the environmental assessment of horticultural production with organic or mineral fertilization. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2011, 16, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maja, M.M.; Ayano, S.F. The impact of population growth on natural resources and farmers’ capacity to adapt to climate change in low-income countries. Earth Syst. Environ. 2021, 5, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, B. Chapter 12: Resources and sustainable development. In Environmental Science: A Canadian Perspective; Freedman, B., Ed.; Dalhousie University: Halifax, Canada, 2018; pp. 289–314. [Google Scholar]

- Population Media Center. How are population growth and climate change related? 2023. Available online: https://www.populationmedia.org/the-latest/population-growth-and-climate-change (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Gomiero, T.; Pimentel, D.; Paoletti, M.G. Is there a need for a more sustainable agriculture? Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2011, 30, 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakiotis, A. Environmental education. In Angelidis, Z.; Papadopoulou, P., Athanasiou, Ch., Eds.; PPE: Environmental Education and Sustainability; Hellenic Open University: Patras, Greece, 2003; pp. 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Jickling, B. Education for sustainability: a seductive idea, but is it enough for my grandchildren. In Blanken, H., Ed. Met een duurzaam perspectief, essaybundel bij de slotconferentie Extra Impuls 1996–1999; NCDO: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Huckle, J. Realising sustainability in changing times. In Huckle, J.; Sterling, S., Ed.; Education for Sustainability; Earthscan: London, UK, 1996; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Liarakou, G.; Florogiti, E. Environmental: education in education for sustainable development: reflections, trends and proposals; Nisos: Athens, Greece, 2007.

- UNESCO. UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development 2005–2014: International Implementation Scheme – Draft; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Alston JM, Alston, J. M.; Pardey, P.G. Agriculture in the global economy. J. Econ. Perspect. 2014, 28, 121–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, R.F.; et al. The impact of population pressure on agricultural land towards food sufficiency (case in West Kalimantan Province, Indonesia). IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 256, 012050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.E.; et al. A natural resource scarcity typology: theoretical foundations and strategic implications for supply chain management. J. Bus. Logist. 2012, 33, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariani, R.D.; Susilo, B. Population pressure on agricultural land due to land conversion in the suburbs of Yogyakarta. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1039, 012039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitz, V.; Meybeck, A.; Lipper, L.; Young, C.; Braatz, S. Climate change and food security: risks and responses. FAO Report 2016. [CrossRef]

- Zekić, S.; et al. Determining agricultural impact on environment. Outlook Agric. 2018, 47, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, D.; Katz, J.N. Implementing panel-corrected standard errors in R: The pcse package. J. Stat. Softw. 2011, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006. Environmental management – life cycle assessment – principles and framework; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/37456.html (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- ISO 14044:2006. Environmental management – life cycle assessment – requirements and guidelines; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006; Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/38498.html (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Arvanitoyannis, I.S.; Kotsanopoulos, K.V.; Veikou, A. Life cycle assessment (ISO 14040) implementation in foods of animal and plant origin: review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2014, 54, 1253–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jirapornvaree, I.; Suppadit, T.; Kumar, V. Assessing the environmental impacts of agrifood production. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2021, 24, 1099–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waltman, L.; et al. The Leiden Ranking 2011/2012: data collection, indicators, and interpretation. CWTS, Leiden University: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2012. Available online: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1202.3941.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0; The Cochrane Collaboration: London, UK, 2011; Available online: https://handbook.cochrane.org (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- Zhong, Z. Processes for environmentally friendly and/or cost-effective manufacturing. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2021, 36, 987–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caicedo Solano, N.E.; García Llinás, G.A.; Montoya-Torres, J.R. Towards the integration of lean principles and optimization for agricultural production systems: a conceptual review proposition. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 100, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieverding, H.; et al. A life cycle analysis (LCA) primer for the agricultural community. Agron. J. 2020, 112, 3788–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, B.; Agrawal, M. Carbon footprints of agriculture sector. In Muthu, S.S., Ed. Environmental Footprints and Eco-design of Products and Processes; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Halog, A. Towards better life cycle assessment and circular economy: on recent studies on interrelationships among environmental sustainability, food systems and diet. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 27, 515–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkat, K. Comparison of twelve organic and conventional farming systems: a life cycle greenhouse gas emissions perspective. J. Sustain. Agric. 2012, 36, 620–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziolas, E.; et al. Life cycle assessment and multi-criteria analysis in agriculture: synergies and insights. In Zopounidis, C.; Doumpos, M., Figueira, J., Eds.; Multiple Criteria Decision Making; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 289–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, C.R.; Larivière, V. Measuring Research: What Everyone Needs to Know; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2024; Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Measuring_Research.html?id=O3I8DwAAQBAJ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Rousseau, R.; Egghe, L.; Guns, R. Becoming Metric-Wise: A Bibliometric Guide for Researchers; Chandos Publishing: Hull, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Glä Glänzel, W.; Moed, H.F.; Schmoch, U.; Thelwall, M. (Eds.) Springer Handbook of Science and Technology Indicators; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Pattnaik, D. Forty-five years of Journal of Business Research: a bibliometric analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 109, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. Research constituents, intellectual structure, and collaboration patterns in Journal of International Marketing: an analytical retrospective. J. Int. Mark. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Pattnaik, D.; Ashraf, R.; Ali, I.; Kumar, S.; Donthu, N. Value of special issues in the Journal of Business Research: a bibliometric analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.K.; Marrone, M.; Singh, A.K. Conducting systematic literature reviews and bibliometric analyses. Aust. J. Manag. 2019, 45, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, G.; Wetterich, F.; Geier, U. Life cycle assessment framework in agriculture on the farm level. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2000, 5, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habersatter, K. Ökobilanz von Packstoffen – Stand 1990; BUWAL: Bern, Switzerland, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Heijungs, R.; Guinée, J.B.; Huppes, G.; Langreijer, R.M.; de Haes, H.A.U.; Sleeswijk, A.W. Environmental life cycle assessment of products – backgrounds 9267; CML: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1992; 130p. [Google Scholar]

- Audsley, E. Harmonisation of Environmental Life Cycle Assessment for Agriculture. Final Report, Concerted Action AIR3-CT94-2028; European Commission, DG VI Agriculture: Brussels, Belgium, 1997; p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- FAL. Ökobilanzen – Beitrag zu einer nachhaltigen Landwirtschaft; Schriftenreihe FAL: Zürich, Switzerland, 2002; 37p. [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard, G.; Nemecek, T. Swiss agricultural life cycle assessment (SALCA): an integrated environmental assessment concept for agriculture. In Proceedings of the International Conference “Integrated Assessment of Agriculture and Sustainable Development”, AgSAP Office, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 134–135. [Google Scholar]

- Sleeswijk, A.W.; Meussen, M.J.G.; van Zeijts, H.; Kleijn, R.; Leneman, H.; Reus, J.; Sengers, H. Application of LCA to agricultural products; CML: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1996; 106p. [Google Scholar]

- Moutik, B.; Summerscales, J.; Graham-Jones, J.; Pemberton, R. Life cycle assessment research trends and implications: a bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedkoop, M.; Spriensma, R. The Eco-Indicator 99: a damage oriented method for life cycle impact assessment, methodology report, 3rd ed.; PRé Consultants: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2001; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/247848113 (accessed on 6 June 2025).

- Jolliet, O.; Margni, M.; Charles, R.; Humbert, S.; Payet, J.; Rebitzer, G.; Rosenbaum, R. IMPACT 2002+: a new life cycle impact assessment methodology. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2003, 8, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . Guinée, J.B. Handbook on life cycle assessment: operational guide to the ISO standards. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2002, 7, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- . Finnveden, G.; Hauschild, M.; Ekvall, T.; Guinée, J.; Heijungs, R.; Hellweg, S.; Koehler, A.; Pennington, D.; Suh, S. Recent developments in life cycle assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 91, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potting, J.; Hauschild, M.Z. Background for spatial differentiation in life cycle impact assessment. The EDIP2003 Methodology; DTU Library: Kongens Lyngby, Denmark, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Binnemans, K.; Jones, P.T.; Blanpain, B.; Van Gerven, T.; Yang, Y.; Walton, A.; Buchert, M. Recycling of rare earths: a critical review. J. Clean Prod. 2013, 51, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levasseur, A.; Lesage, P.; Margni, M.; Deschênes, L.; Samson, R. Considering time in LCA: dynamic LCA and its application to global warming impact assessments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 3169–3174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrickson, C.; Horvath, A.; Joshi, S.; Lave, L. Economic input-output models for environmental life-cycle assessment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1998, 32, 184A–191A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellegaard, O.; Wallin, J.A. The bibliometric analysis of scholarly production: how great is the impact? Scientometrics 2015, 105, 1809–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pritchard, A. Statistical bibliography or bibliometrics. J. Doc. 1969, 25, 348. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, C.R.; Cone, D.C.; Sarli, C.C. Using publication metrics to highlight academic productivity and research impact. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2014, 21, 1160–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durieux, V.; Gevenois, P.A. Bibliometric Indicators: Quality Measurements of Scientific Publication. Radiology 2010, 255, 342–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowley, J.; Slack, F. Conducting a literature review. Manag. Res. News 2004, 27, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachos, G.K. Evaluating Basic Research Using Bibliometric Techniques; [Εκδότης]: Athens, Greece, 2019; ISBN 9789602868485. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, J.E. An index to quantify an individual's scientific research output. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 16569–16572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornmann, L.; Daniel, H.D. What do we know about the h-index? J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2007, 58, 1381–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H. Google Scholar Metrics for Publications. 2012. Available online: https://googlescholar.blogspot.com.br (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Jones, T.; Huggett, S.; Kamalski, J. Finding a way through the scientific literature: indexes and measures. World Neurosurg. 2011, 76, 36–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egghe, L. Theory and practise of the g-index. Scientometrics 2006, 69, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biradar, N.; Kumbar, P. A comparative study: application of Bradford’s law of scattering to the epidemiology literature of India and Japan. Res. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2020, 4, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, S.C. Sources of information on specific subjects. Engineering: An Illustrated Weekly Journal 1934, 10, 85–86. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, S.C. Specific subjects. J. Inf. Sci. 1985, 10, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zupic, I.; Cater, T. Bibliometric methods in management and organization. Organ. Res. Methods 2015, 18, 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, B.V.; Banister, D. How to write a literature review paper? Transp. Rev. 2016, 36, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonaki, E.G.; Arvanitis, K.G.; Piromalis, D.D. Current trends and challenges in the deployment of IoT technologies for climate smart facility agriculture. Int. J. Sustain. Agric. Manag. Inform. 2019, 5, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Mao, G.; Zhao, L.; Zuo, J. Mapping the scientific research on life cycle assessment: a bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 20, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; et al. Mapping the scientific research on life cycle assessment: a bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 20, 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarnicola, B.; Tassielli, G.; Renzulli, P.A.; Castellani, V.; Sala, S. Environmental impacts of food consumption in Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieverding, H.; et al. A life cycle analysis (LCA) primer for the agricultural community. Agron. J. 2020, 112, 3788–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebitzer, G.; Ekvall, T.; Frischknecht, R.; Hunkeler, D.; Norris, G.; Rydberg, T.; Schmidt, W.P.; Suh, S.; Weidema, B.P.; Pennington, D.W. Life cycle assessment part 1: framework, goal and scope definition, inventory analysis, and applications. Environ. Int. 2004, 30, 701–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, A.; et al. Nexus on climate change: agriculture and possible solution to cope future climate change stresses. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 14211–14232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anton, A.; et al. Improvement of agricultural life cycle assessment studies through spatial differentiation and new impact categories: case study on greenhouse tomato production. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 9454–9462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, N.; Martin, A.; Camfield, L. Can agricultural intensification help attain Sustainable Development Goals? Evidence from Africa and Asia. Third World Q. 2019, 40, 926–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelock, V.G. Multidimensional environmental social governance sustainability framework: integration, using a purchasing, operations, and supply chain management context. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 923–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hietala, M.; Geysmans, R. Social sciences and radioactive waste management: acceptance, acceptability, and a persisting socio-technical divide. J. Risk Res. 2020, 25, 423–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.C.; et al. Trends in ecology and conservation over eight decades. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2021, 19, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikis, J.; Baležentis, T. Agricultural sustainability assessment framework integrating sustainable development goals and interlinked priorities of environmental, climate and agriculture policies. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1702–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; et al. A bibliometric analysis of sustainable agriculture: based on the Web of Science (WOS) platform. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 38928–38949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelletier, N.; Arsenault, N.; Tyedmers, P. Scenario-modeling potential eco-efficiency gains from a transition to organic agriculture: life cycle perspectives on Canadian canola, corn, soy and wheat production. Environ. Manag. 2008, 42, 989–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdivia, S.; et al. Principles for the application of life cycle sustainability assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 1900–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, D.S.; Tyagi, S.; Soni, S.K. A techno-economic analysis of digital agriculture services: an ecological approach toward green growth. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 19, 3859–3870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, C.K.; Singh, S. Best management practices for agricultural nonpoint source pollution: policy interventions and way forward. World Water Policy 2019, 5, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, J.; et al. Modeling to evaluate and manage climate change effects on water use in Mediterranean olive orchards with respect to cover crops and tillage management. Adv. Agric. Syst. Model. 2015, 5, 237–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabaldón-Leal, C.; et al. Impact of changes in mean and extreme temperatures caused by climate change on olive flowering in southern Spain. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, S940–S957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boitshwarelo, B.; Reedy, A.K.; Billany, T. Envisioning the use of online tests in assessing twenty-first century learning: a literature review. Res. Pract. Technol. Enhanc. Learn. 2017, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reynolds, T.W.; et al. Environmental impacts and constraints associated with the production of major food crops in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Food Secur. 2015, 7, 795–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, S.; et al. The evolution of life cycle assessment in European policies over three decades. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 2295–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoolman, E.D.; et al. How interdisciplinary is sustainability research? Analyzing the structure of an emerging scientific field. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 7, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; et al. Effects of spatial scale on life cycle inventory results. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 54, 1293–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tziolas, E.; et al. Life cycle assessment and multi-criteria analysis in agriculture: synergies and insights. In Multiple Criteria Decision Making; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 289–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørn, A.; et al. Review of life-cycle based methods for absolute environmental sustainability assessment and their applications. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 083001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustafson, D.; et al. In pursuit of more fruitful food systems. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2022, 27, 1267–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonaki, E.G.; Arvanitis, K.G.; Piromalis, D.D. Current trends and challenges in the deployment of IoT technologies for climate smart facility agriculture. Int. J. Sustain. Agric. Manag. Inform. 2019, 5, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | h index | g index | M index | TC | NP | PY start |

| Nemecek T | 17 | 22 | 0,8947368 | 1613 | 22 | 2006 |

| Bacenetti JJ | 10 | 13 | 0,9090909 | 513 | 13 | 2014 |

| Rieravevall J | 10 | 11 | 0,6666666 | 755 | 11 | 2010 |

| Van der Werf HMG | 10 | 11 | 0,5 | 1205 | 11 | 2005 |

| Wang X | 10 | 13 | 0,7692307 | 386 | 13 | 2012 |

| Gaillard G | 9 | 10 | 0,4736842 | 913 | 10 | 2006 |

| Nabali - Pelesaraei A | 8 | 8 | 1 | 646 | 8 | 2017 |

| Gabarrell X | 7 | 8 | 0,4666666 | 484 | 8 | 2010 |

| Zhang Y | 7 | 9 | 0,4375 | 243 | 9 | 2009 |

| Aubin J | 6 | 6 | 0,375 | 351 | 6 | 2009 |

| Source | Rank | Freq | cumFreq |

| Journal of Cleaner Production | 1 | 287 | 287 |

| Sustainability (Switzerland) | 2 | 70 | 357 |

| Agricultural Systems | 3 | 33 | 390 |

| Environmental Science and Pollution Research | 4 | 24 | 414 |

| Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews | 5 | 24 | 438 |

| Journal of Industrial Ecology | 6 | 21 | 459 |

| Sustainable Production and Consumption | 7 | 20 | 479 |

| Label | Group | Freq | Centrality | Impact |

| environmental impact - conf 21.9% life cycle - conf 14.6% agriculture - conf 13.3% |

1 | 27 | 0,54298317 | 4,72050265 |

| life cycle - conf 29.3% agriculture - conf 26.7% environmental impact - conf 21.9% |

3 | 18 | 0,52981857 | 1,84077243 |

| life cycle - conf 56.1% agriculture - conf 60% environmental impact - conf 56.2% |

5 | 48 | 1,43121433 | 1,66410422 |

| Source | Publications |

| Journal of Cleaner Production | 31 |

| Sustainability (Switzerland) | 6 |

| Sustainable Production and Consumption | 5 |

| Agricultural Systems | 4 |

| Environmental Impact Assessment Review | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).