Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

14 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Isolation and Phenotypic Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes

2.3. Genotypic Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes Isolates

2.3.1. DNA Extraction

2.3.2. Detection of Virulence Factors by PCR

2.3.3. Molecular Serotyping of Wild Isolates of Listeria Monocytogenes

2.4. Assessing the Virulence of L. monocytogenes Isolates on Chicken Embryos

2.4.1. Checking for the Dead Embryos

2.4.2. L. monocytogenes Inoculum

2.4.3. Infecting the Chicken Embryos with L. monocytogenes Wild Type Isolates

2.4.4. L. monocytogenes Detection in Chicken Liver Embryos

2.5. Ethical Declaration for the Use of Chicken Embryos

2.6. Assessment of the Antibiotic Resistance Profiles of Wild-Type L. monocytogenes Isolates

2.7. Antimicrobial Assays with Shrimp Chitosan Against L. monocytogenes Isolates

2.7.1. Chitosan Preparation

2.7.2. Chitosan Antimicrobial Assay

3. Results

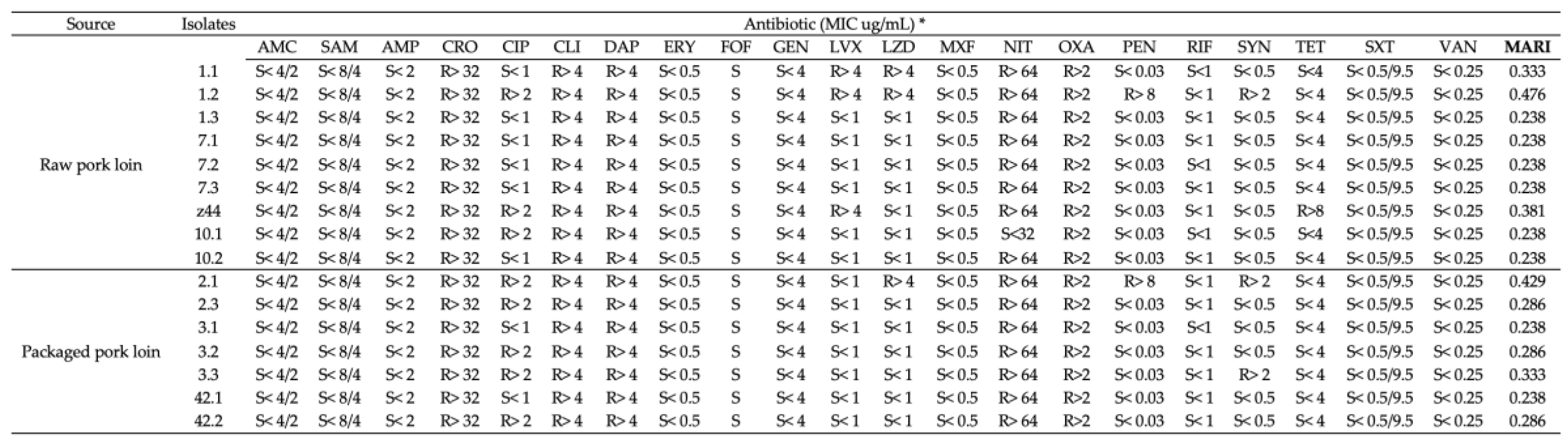

3.1. Identification of L. monocytogenes Isolates

3.2. Prevalence of L. monocytogenes in Fresh Pork Loin and Fresh Packaged Pork Loin

3.3. Serotype Identification of L. monocytogenes Isolates

3.4. Detection of Virulence Factors in L. monocytogenes Isolates

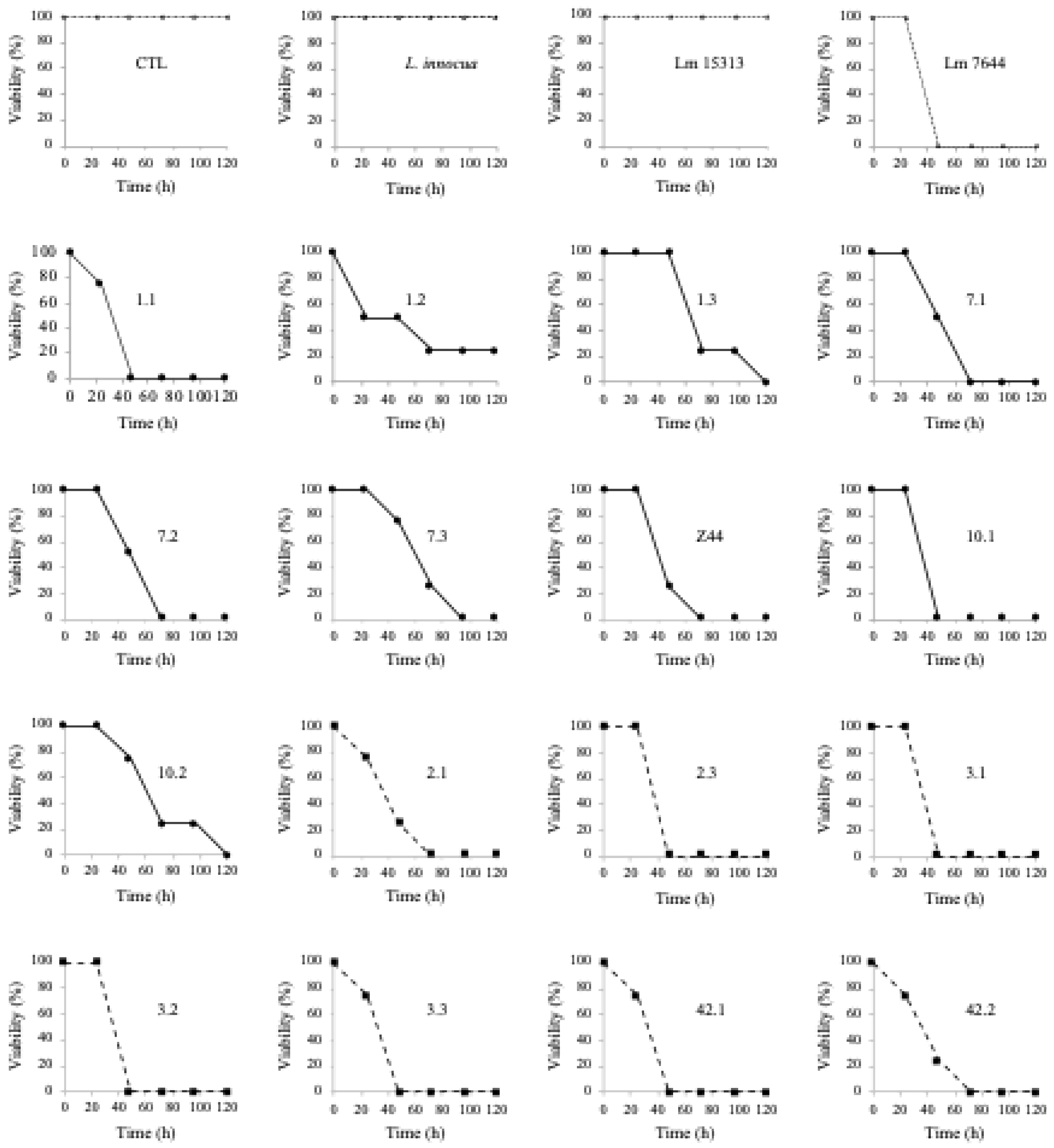

3.5. Assessing the Virulence of L. monocytogenes Isolates on Chicken Embryos

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carpentier, B.; Cerf, O. Review-Persistence of Listeria Monocytogenes in Food Industry Equipment and Premises. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2011, 145, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoder, D.; Pelz, A.; Paulsen, P. Transmission Scenarios of Listeria Monocytogenes on Small Ruminant on-Farm Dairies. Foods 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoder, D.; Guldimann, C.; Märtlbauer, E. Asymptomatic Carriage of Listeria Monocytogenes by Animals and Humans and Its Impact on the Food Chain. Foods 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muchaamba, F.; Eshwar, A.K.; Stevens, M.J.A.; Stephan, R.; Tasara, T. Different Shades of Listeria Monocytogenes: Strain, Serotype, and Lineage-Based Variability in Virulence and Stress Tolerance Profiles. Frontiers in Microbiology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doumith, M.; Buchrieser, C.; Glaser, P.; Jacquet, C.; Martin, P. Differentiation of the Major Listeria Monocytogenes Serovars by Multiplex PCR. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2004, 42, 3819–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducey, Thomas; Usgaard Thomas; Dunn Katherine A. ; Bielawski Joseph P.; Ward, T.J. Multilocus Genotyping Assays for Single Nucleotide Polymorphism-Based Subtyping of Listeria Monocytogenes Isolates. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2008, 74, 7629–7642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orsi, R.H.; Bakker, H.C. den; Wiedmann, M. Listeria Monocytogenes Lineages: Genomics, Evolution, Ecology, and Phenotypic Characteristics. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2011, 301, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra-Flores, J.; Holý, O.; Bustamante, F.; Lepuschitz, S.; Pietzka, A.; Contreras-Fernández, A.; Castillo, C.; Ovalle, C.; Alarcón-Lavín, M.P.; Cruz-Córdova, A.; et al. Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Listeria Monocytogenes Strains Isolated from Ready-to-Eat Foods in Chile. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Drug Administration Listeria (Listeriosis) Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/foodborne-pathogens/listeria-listeriosis#:~:text=Past%20listeriosis%20outbreaks%20in%20the,found%20in%20raw%20pet%20food.

- Bridges, D.F.; Bilbao-Sainz, C.; Powell-Palm, M.J.; Williams, T.; Wood, D.; Sinrod, A.J.G.; Ukpai, G.; McHugh, T.H.; Rubinsky, B.; Wu, V.C.H. Viability of and Salmonella Typhimurium after Isochoric Freezing. Journal of Food Safety 2020, 40, e12840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaître, N.; Rasschaert, G.; De Zutter, L.; Geeraerd, A.; De Reu, K. Genetic Listeria Monocytogenes Types in the Pork Processing Plant Environment: From Occasional Introduction to Plausible Persistence in Harborage Sites. Pathogens 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thévenot, D.; Dernburg, A.; Vernozy-Rozand, C. An Updated Review of Listeria Monocytogenes in the Pork Meat Industry and Its Products. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2006, 101, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pricope, L.; Nicolau, A.; Wagner, M.; Rychli, K. The Effect of Sublethal Concentrations of Benzalkonium Chloride on Invasiveness and Intracellular Proliferation of Listeria Monocytogenes. Food Control 2013, 31, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quereda, J.J.; Morón-García, A.; Palacios-Gorba, C.; Dessaux, C.; García-del Portillo, F.; Pucciarelli, M.G.; Ortega, A.D. Pathogenicity and Virulence of Listeria Monocytogenes: A Trip from Environmental to Medical Microbiology. Virulence 2021, 12, 2509–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kayode, A.J.; Igbinosa, E.O.; Okoh, A.I. Overview of Listeriosis in the Southern African Hemisphere—Review. Journal of Food Safety 2020, 40, e12732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Boland, J.A.; Domínguez-Bernal, G.; González-Zorn, B.; Kreft, J.; Goebel, W. Pathogenicity Islands and Virulence Evolution in Listeria. Microbes and Infection 2001, 3, 571–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Boland, J.A. ; Kuhn Michael; Berche Patrick; Chakraborty Trinad; Domı́nguez-Bernal Gustavo; Goebel Werner; González-Zorn Bruno; Wehland Jürgen; Kreft Jürgen Listeria Pathogenesis and Molecular Virulence Determinants. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2001, 14, 584–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntshanka, Z.; Ekundayo, T.C.; du Plessis, E.M.; Korsten, L.; Okoh, A.I. Occurrence and Molecular Characterization of Multidrug-Resistant Vegetable-Borne Listeria Monocytogenes Isolates. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1353–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA The European Union One Health 2018 Zoonoses Report. 2018.

- Lundén, J.; Autio, T.; Markkula, A.; Hellström, S.; Korkeala, H. Adaptive and Cross-Adaptive Responses of Persistent and Non-Persistent Listeria Monocytogenes Strains to Disinfectants. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2003, 82, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folsom, J.P.; Frank, J.F. Chlorine Resistance of Listeria Monocytogenes Biofilms and Relationship to Subtype, Cell Density, and Planktonic Cell Chlorine Resistance. Journal of Food Protection 2006, 69, 1292–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Møretrø, T.; Schirmer, B.C.T.; Heir, E.; Fagerlund, A.; Hjemli, P.; Langsrud, S. Tolerance to Quaternary Ammonium Compound Disinfectants May Enhance Growth of Listeria Monocytogenes in the Food Industry. International Journal of Food Microbiology 2017, 241, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardean, C.; Davidescu, C.M.; Nemeş, N.S.; Negrea, A.; Ciopec, M.; Duteanu, N.; Negrea, P.; Duda-seiman, D.; Musta, V. Factors Influencing the Antibacterial Activity of Chitosan and Chitosan Modified by Functionalization. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, Vol. 22, Page 7449 2021, 22, 7449–7449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momtaz, H.; Yadollahi, S. Molecular Characterization of Listeria Monocytogenes Isolated from Fresh Seafood Samples in Iran. Diagnostic Pathology 2013, 8, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Serotypes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Samples | Prevalence | L. monocytogenes isolates obtained | 1/2a | 1/2b | 4b | ND |

| Raw pork loin | 16 | 56.3 % | 9 | 1 (11.1 %) | 7 (77.8 %) | ̶̶̶ | 1 (11.1 %) |

| Raw packaged pork loin | 10 | 70 % | 7 | 1 (14.3 %) | 4 (57.1 %) | 1 (14.3 %) | 1 (14.3 %) |

| TOTAL | 26 | 61.5 % | 16 | 2 (12.5%) | 11 (68.75 %) | 1 (6.25 %) | 2 (12.5 %) |

| Source | Bacterial isolate | Virulence factors | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| actA | hlyA | lnlA | InlB | InlC | InlJ | Iap | plcA | plcB | prfA | Serotype | |||

| Raw pork loin | L. monocytogenes ATCC 7644* | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1/2a | |

| Lm 1.1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1/2b | ||

| Lm 1.2 | + | + | ND | ND | + | ND | + | + | + | + | 1/2b | ||

| Lm 1.3 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1/2b | ||

| Lm 7.1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1/2b | ||

| Lm 7.2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ND | + | + | 1/2b | ||

| Lm 7.3 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1/2b | ||

| Lm Z44 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1/2a | ||

| Lm 10.1 | + | + | + | ND | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1/2b | ||

| Lm 10.2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ND | ||

| Raw packaged pork loin | Lm 2.1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1/2a | |

| Lm 2.3 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1/2b | ||

| Lm 3.1 | ND | + | + | + | + | + | + | ND | + | + | 4b | ||

| Lm 3.2 | ND | + | + | + | + | + | + | ND | + | + | 1/2b | ||

| Lm 3.3 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1/2b | ||

| Lm 42.1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ND | ||

| Lm 42.2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 1/2b | ||

|

| Log (CFU/mL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolate | Initial Inoculum | Control† | Chitosan (0.25%)† | Acetic acid (1%)† | |

| Raw pork loin | Lm 1.1 | 6.36ª | 6.83ª | 0.00b | 6.54ª |

| Lm 1.2 | 6.55ª | 6.76ª | 0.00b | 6.13ª | |

| Lm 1.3 | 6.18ª | 6.35ª | 0.00b | 6.27ª | |

| Lm 7.1 | 6.33ª | 6.70ª | 0.00b | 6.12ª | |

| Lm 7.2 | 6.09ª | 6.59ª | 0.00b | 6.48ª | |

| Lm 7.3 | 6.32ª | 6.71ª | 0.00b | 6.21ª | |

| Lm z44 | 6.49ª | 6.58ª | 0.00b | 6.58ª | |

| Lm 10.1 | 5.87ª | 6.58ª | 4.03ª | 6.50ª | |

| Lm 10.2 | 6.39ª | 6.61ª | 0.00b | 6.33ª | |

| Packaged pork loin | Lm 2.1 | 5.11ª | 5.18ª | 0.00b | 5.11ª |

| Lm 2.3 | 5.13ª | 5.43ª | 0.00b | 5.28ª | |

| Lm 3.1 | 5.36ª | 5.53ª | 0.00b | 5.27ª | |

| Lm 3.2 | 5.55ª | 5.77ª | 0.00b | 5.57ª | |

| Lm 3.3 | 5.17ª | 5.24ª | 0.00b | 5.25ª | |

| Lm 42.1 | 5.61ª | 5.75ª | 0.00b | 5.40ª | |

| Lm 42.2 | 5.26ª | 5.63ª | 0.00b | 5.49ª | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).