Submitted:

24 September 2024

Posted:

25 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Genomic of L. monocytogenes Sublineages and Virulence Genes

2.2. Antimicrobial Resistance Gene Profiling

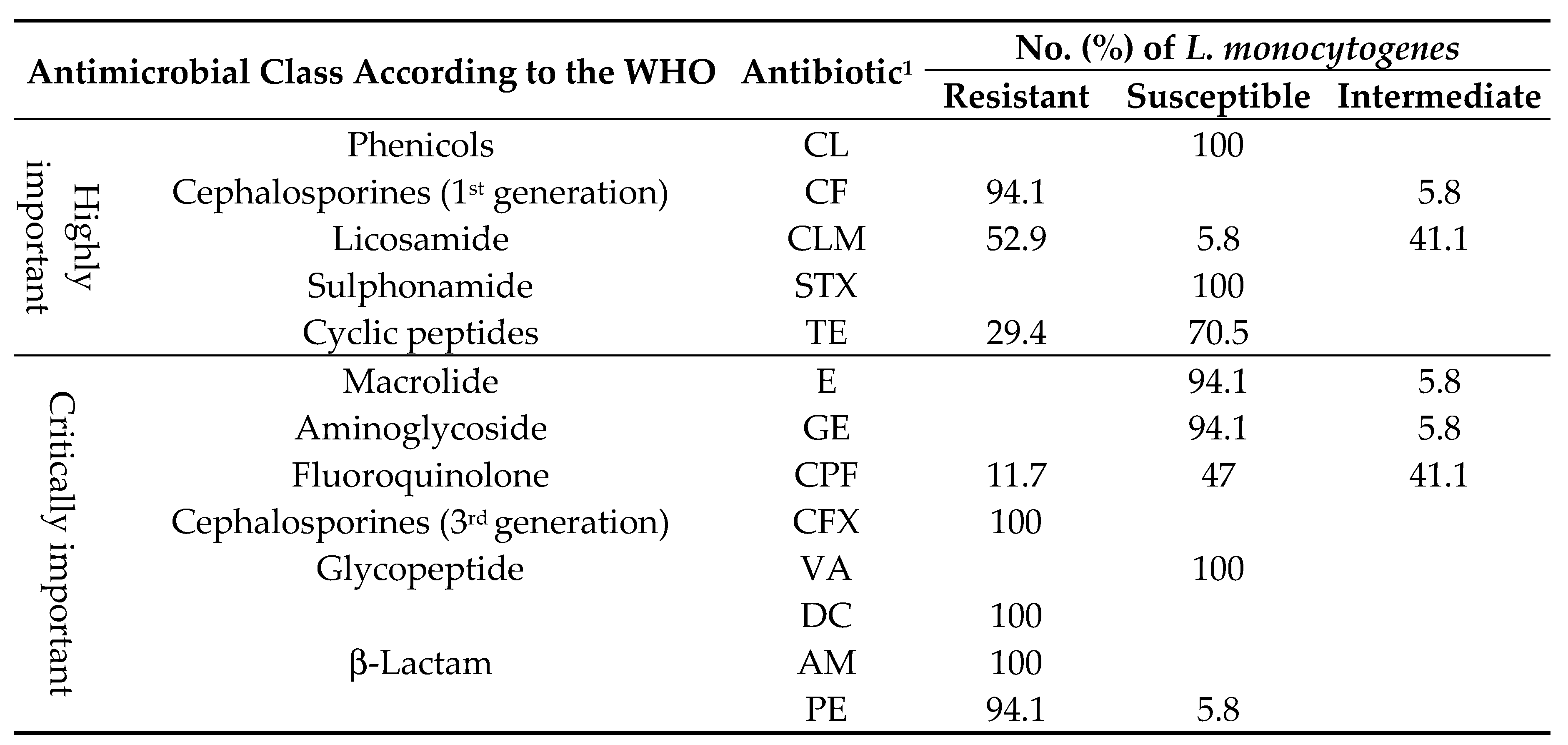

2.3. Antimicrobials, Sanitizing, Cadmium, and Biofilm

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains

4.2. Genomic Characterization: Genes Involved in Pathogenicity Islands, Biofilm Formation and Resistance Antibiotics

4.3. Phenotypic Characterization for the Persistence of L. monocytogenes

4.3.1. Disinfectant and Heavy Metal Sensitivity

4.3.2. Phenotypic Antibiotic Sensitivity and Resistance Analysis

4.3.3. Biofilm Formation Assay

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Charlier, C. , Perrodeau, É., Leclercq, A., Cazenave, B., Pilmis, B., Henry, B., Lopes, A., Maury, M. M., Moura, A., Goffinet, F., Dieye, H. B., Thouvenot, P., Ungeheuer, M. N., Tourdjman, M., Goulet, V., de Valk, H., Lortholary, O., Ravaud, P., Lecuit, M., MONALISA study group. Clinical features and prognostic factors of listeriosis: the MONALISA national prospective cohort study. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Boland, J.A. , Kuhn, M., Berche, P., Chakraborty, T., Domínguez-Bernal, G., Goebel, W., González-Zorn, B., Wehland, J., Kreft, J. Listeria pathogenesis and molecular virulence determinants. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001, 14, 584–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Listeria Infection (Listeriosis). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/listeria/about/index.html (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Listeria. Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/listeria#efsas-role (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Chen, M. , Chen, Y., Wu, Q., Zhang, J., Cheng, J., Li, F., Zeng, H., Lei, T., Pang, R., Ye, Q., Bai, J., Wang, J., Wei, X., Zhang, Y., Ding, Y. Genetic characteristics and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from fresh vegetables in China. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gartley, S. , Anderson-Coughlin, B., Sharma, M., Kniel, K.E. Listeria monocytogenes in Irrigation Water: An Assessment of Outbreaks, Sources, Prevalence, and Persistence. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayode, A.J. , Okoh, A.I. Incidence and genetic diversity of multi-drug resistant Listeria monocytogenes isolates recovered from fruits and vegetables in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 363, 109513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Interagency Food Safety Analytics Collaboration (IFSAC). 2022. Foodborne illness source attribution estimates for 2020 for Salmonella, Escherichia coli O157, and Listeria monocytogenes using multi-year outbreak surveillance data, United States. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/ifsac/media/pdfs/P19-2020-report- TriAgency-508.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Food & Drudg Administration (FDA). 2024. Recalls, Market Withdrawals, & Safety Alerts. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/safety/recalls-market-withdrawals-safety-alerts (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Food Standard Australia- New Zealand (FSANZ). Australian food recall statistics. Available online: https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/food-recalls/recallstats (accessed on 16 August 2024).

- Hu, X. , Zhou, Q., Luo, Y. Occurrence and source analysis of typical veterinary antibiotics in manure, soil, vegetables and groundwater from organic vegetable bases, northern China. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 2992–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popowska, M. , Rzeczycka, M., Miernik, A., Krawczyk-Balska, A., Walsh, F., Duffy, B. Influence of soil use on prevalence of tetracycline,streptomycin, and erythromycin resistance and associated resistance genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 1434–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, M. , Sadrabad, E.K., Hamidian, N., Heydari, A., Mohajeri, F.A. Prevalence and Antibiotic Resistance of Listeria monocytogenes in Chicken Meat Retailers in Yazd, Iran. J. Environ. Health Sustain. Dev. 2019, 4, 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broncano-Lavado, A. , Santamaría-Corral, G., Esteban, J., García-Quintanilla, M. Advances in bacteriophage therapy against relevant multidrug-resistant pathogens. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. , Bao, H., Yang, Z., He, T., Tian, Y., Zhou, Y., Pang, M., Wang, R., Zhang, H. Antimicrobial susceptibility, multilocus sequence typing, and virulence of Listeria isolated from a slaughterhouse in Jiangsu, China. BMC Microbiol. 2021, 21, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giono-Cerezo, S. , Santos-Preciado, J.I., Morfín-Otero, M.R., Torres-López, F.J., Alcántar-Curiel, M.D. Resistencia antimicrobiana. Importancia y esfuerzos por contenerla. Gac. Méd. Méx. 2020, 156, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentier, B. , Cerf, O. Review - Persistence of Listeria monocytogenes in food industry equipment and premises. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 145, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colagiorgi, A. , Bruini, I., Di Ciccio, P.A., Zanardi, E., Ghidini, S., Ianieri, A. Listeria monocytogenes Biofilms in the wonderland of food industry. Pathogens 2017, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T. , Jiang, X., Xu, X., Jiang, C., Kang, R., Jiang, X. Andrographolide Inhibits Biofilm and Virulence in Listeria monocytogenes as a Quorum-Sensing Inhibitor. Molecules 2022, 27, 3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, P. , Chajęcka-Wierzchowska, W., Zadernowska, A. High-Pressure Processing—Impacts on the Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance of Listeria monocytogenes Isolated from Food and Food Processing Environments. Foods 2023, 12, 3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. , Dong, S., Chen, H., Chen, J., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Yang, Y., Xu, Z., Zhan, L., Mei, L. Prevalence, Genotypic Characteristics and Antibiotic Resistance of Listeria monocytogenes From Retail Foods in Bulk in Zhejiang Province, China. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maćkiw, E. , Korsak, D., Kowalska, J., Felix, B., Stasiak, M., Kucharek, K., Postupolski, J. Incidence and genetic variability of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from vegetables in Poland. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 339, 109023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. , Wu, Q., Zhang, J., Yan, Z., Wang, J. Prevalence and characterization of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from retail-level ready-to-eat foods in South China. Food Control 2014, 38, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumith, M. , Buchrieser, C., Glaser, P., Jacquet, C., Martin, P. Differentiation of the major Listeria monocytogenes serovars by multiplex PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 3819–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, D. , Bodero, M., Riveros, G., Lapierre, L., Gaggero, A., Vidal, R.M., Vidal, M. Molecular epidemiology and genetic diversity of Listeria monocytogenes isolates from a wide variety of ready-to-eat foods and their relationship to clinical strains from listeriosis outbreaks in Chile. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poimenidou, S.V. , Dalmasso, M., Papadimitriou, K., Fox, E.M., Skandamis, P.N., Jordan, K. Virulence gene sequencing highlights similarities and differences in sequences in Listeria monocytogenes serotype 1/2a and 4b strains of clinical and food origin from 3 different geographic locations. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro-Cerdá, J. , Cossart, P. Microbe profile: Listeria monocytogenes: A paradigm among intracellular bacterial pathogens. Microbiology (Reading) 2019, 165, 719–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matle, I. , Mbatha, K.R., Madoroba, E. A review of Listeria monocytogenes from meat and meat products: Epidemiology, virulence factors, antimicrobial resistance and diagnosis. Onderstepoort J. Vet. Res. 2020, 87, e1–e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, K.M. , Kappell, A.D., Fox, E.M., Orabi, A., Samir, A. Prevalence, pathogenicity, virulence, antibiotic resistance, and phylogenetic analysis of biofilmproducing Listeria monocytogenes isolated from different ecological niches in Egypt: Food, humans, animals, and environment. Pathogens 2020, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.A. , Chandry, P.S., Kaur, M., Kocharunchitt, C., Bowman, J.P., Fox, E.M. Characterisation of Listeria monocytogenes food-associated isolates to assess environmental fitness and virulence potential. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 350, 109247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwu, C.D. , Okoh, A.I. Characterization of antibiogram fingerprints in Listeria monocytogenes recovered from irrigation water and agricultural soil samples. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pournajaf, A. , Rajabnia, R., Sedighi, M., Kassani, A., Moqarabzadeh, V., Lotfollahi, L., Ardebilli, A., Emadi, B., Irajian, G. Prevalence, and virulence determination of Listeria monocytogenes strains isolated from clinical and non-clinical samples by multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2016, 49, 624–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilchis-Rangel, R.E. , Espinoza-Mellado, M.R., Salinas-Jaramillo, I.J., Martinez-Peña, M.D., Rodas-Suárez, O.R. Association of Listeria monocytogenes LIPI-1 and LIPI-3 marker llsX with invasiveness. Curr. Microbiol. 2019, 76, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maury, M.M. , Tsai, Y.H., Charlier, C., Touchon, M., Chenal-Francisque, V., Leclercq, A., Criscuolo, A., Gaultier, C., Roussel, S., Brisabois, A., Disson, O., Rocha, E.P.C., Brisse, S., Lecuit, M. Uncovering Listeria monocytogenes hypervirulence by harnessing its biodiversity. Nat. Genet. 2016, 48, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafuna, T. , Matle, I., Magwedere, K., Pierneef, R.E., Reva, O.N. Whole Genome-Based Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes Isolates Recovered From the Food Chain in South Africa. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 669287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurice Bilung, L. , Sin Chai, L., Tahar, A.S., Ted, C.K., Apun, K. Prevalence, Genetic Heterogeneity, and Antibiotic Resistance Profile of Listeria spp. and Listeria monocytogenes at Farm Level: A Highlight of ERIC- and BOX-PCR to Reveal Genetic Diversity. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 3067494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, P. , Zakrzewski, A.J., Zadernowska, A., Chajęcka-Wierzchowska, W. Antimicrobial Resistance and Virulence Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes Strains Isolated from Food and Food Processing Environments. Pathogens 2022, 11, 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panera-Martínez, S. , Capita, R., García-Fernández, C., Alonso-Calleja, C. Viability and Virulence of Listeria monocytogenes in Poultry. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boháčová, M. , Zdeňková, K., Tomáštíková, Z., Fuchsová, V., Demnerová, K., Karpíšková, R., Pazlarová, J. Monitoring of resistance genes in Listeria monocytogenes isolates and their presence in the extracellular DNA of biofilms: a case study from the Czech Republic. Folia Microbiol. 2018, 63, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwu, C.D. , Okoh, A.I. Preharvest transmission routes of fresh produce associated bacterial pathogens with outbreak potentials: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krumperman, P.H. Multiple antibiotic resistance indexing of Escherichia coli to identify high-risk sources of fecal contamination of foods. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1983, 46, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titilawo, Y. , Sibanda, T., Obi, L., Okoh, A. Multiple antibiotic resistance indexing of Escherichia coli to identify high-risk sources of faecal contamination of water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 10969–10980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abriouel, H. , Omar, N.B., Molinos, A.C., López, R.L., Grande, M.J., Martínez-Viedma, P., Ortega, E., Cañamero, M.M., Galvez, A. Comparative analysis of genetic diversity and incidence of virulence factors and antibiotic resistance among enterococcal populations from raw fruit and vegetable foods, water and soil, and clinical samples. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2008, 123, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matereke, L.T. , Okoh, A.I. Listeria monocytogenes virulence, antimicrobial resistance and environmental persistence: A review. Pathogens 2020, 9, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, S. , Huys, G., Yde, M., D’Haene, K., Tardy, F., Vrints, M., Swings, J., Collard, J.M. Detection and characterization of tet(M) in tetracycline-resistant Listeria strains from human and food-processing origins in Belgium and France. J. Med. Microbiol. 2005, 54, 1151–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Novoa, M.G. , González-Torres, B., González-Gómez, J.P., Guerrero-Medina, P.J., Martínez-Chávez, L., Martínez-Gonzáles, N.E., Chaidez, C., Gutiérrez-Lomelí, M. Genomic Insights into Listeria monocytogenes: Organic Acid Interventions for Biofilm Prevention and Control. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) /Veterinary Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (VetCAST). Available online: https://www.eucast.org/ast_of_veterinary_pathogens (accessed on 13 August 2024).

- Parsons, C. , Lee, S., Kathariou, S. Heavy metal resistance determinants of the foodborne pathogen Listeria monocytogenes. Genes 2019, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullapudi, S. , Siletzky, R.M., Kathariou, S. Heavy-metal and benzalkonium chloride resistance of Listeria monocytogenes isolates from the environment of Turkey-processing plants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 1464–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D. , Deng, Y., Fan, R., Shi, L., Bai, J., Yan, H. Coresistance to Benzalkonium Chloride Disinfectant and Heavy Metal Ions in Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria innocua Swine Isolates from China. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2019, 16, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. , Zhou, Y., Bao, H., Zhang, L., Wang, R., Zhou, X. Plasmid-borne cadmium resistant determinants are associated with the susceptibility of Listeria monocytogenes to bacteriophage. Microbiol. Res. 2015, 172, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agency For Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR). Cadmium ToxGuide. (Listeriosis). Available online: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxguides/toxguide-5.pdf (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- Thévenot, D. , Dernburg, A., Vernozy-Rozand, C. An updated review of Listeria monocytogenes in the pork meat industry and its products. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2006, 101, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluszak, Z. , Gryń, G., Bauza-Kaszewska, J., Skowron, K.J., Wiktorczyk-Kapischke, N., Korkus, J., Pawlak, M., Szymańska, E., Kraszewska, Z., Buszko, K., Skowron, K. Prevalence and antimicrobialsusceptibility of Listeria monocytogenes strains isolated from a meat processing plant. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2021, 28, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duze, S.T. , Marimani, M., Patel, M. Tolerance of Listeria monocytogenes to biocides used in food processing environments. Food Microbiol. 2021, 97, 103758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Code of Federal Regulations (CFR). Part 178-Indirect Food Additives: Adjuvants, Production Aids, and Sanitizers. Available online: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-21/chapter-I/subchapter-B/part-178#178.1010 (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Xu, D. , Li, Y., Shamim Hasan Zahid, M., Yamasaki, S., Shi, L., Li, J.R., Yan, H. Benzalkonium chloride and heavy-metal tolerance in Listeria monocytogenes from retail foods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 190, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minarovičová, J. , Véghová, A., Mikulášová, M., Chovanová, R., Šoltýs, K., Drahovská, H., Kaclíková, E. Benzalkonium chloride tolerance of Listeria monocytogenes strains isolated from a meat processing facility is related to presence of plasmid-borne bcrABC cassette. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 2018, 111, 1913–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haubert, L. , Zehetmeyr, M.L., da Silva, W.P. Resistance to benzalkonium chloride and cadmium chloride in Listeria monocytogenes isolates from food and food-processing environments in southern Brazil. Can. J. Microbiol. 2019, 65, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, A.L. , Carrillo, C.D., Deschenes, M., Blais, B.W. Genomic markers for quaternary ammonium compound resistance as a persistence indicator for Listeria monocytogenes contamination in food manufacturing environments. J. Food Prot. 2021, 84, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratani, S.S. , Siletzky, R.M., Dutta, V., Yildirim, S., Osborne, J.A., Lin, W., Hitchins, A.D., Ward, T.J., Kathariou, S. Heavy metal and disinfectant resistance of Listeria monocytogenes from foods and food processing plants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 6938–6945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullapudi, S. , Siletzky, R.M., Kathariou, S. Diverse cadmium resistance determinants in listeria monocytogenes isolates from the Turkey processing plant environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 627–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanova, N. , Favrin, S., Griffiths, M.W. Sensitivity of Listeria monocytogenes to sanitizers used in the meat processing industry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 6405–6409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Alonso, V. , Ortiz, S., Corujo, A., Martínez-Suárez, J.V. Analysis of benzalkonium chloride resistance and potential virulence of Listeria monocytogenes isolates obtained from different stages of a poultry production chain in Spain. J. Food Prot. 2020, 83, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Suárez, J.V. , Ortiz, S., López-Alonso, V. Potential impact of the resistance to quaternary ammonium disinfectants on the persistence of Listeria monocytogenes in food processing environments. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, E.M. , Leonard, N., Jordan, K. Physiological and transcriptional characterization of persistent and nonpersistent Listeria monocytogenes isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 6559–6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capita, R. , Riesco-Peláez, F., Alonso-Hernando, A., Alonso-Calleja, C. Exposure of Escherichia coli ATCC 12806 to sublethal concentrations of food-grade biocides influences its ability to form biofilm, resistance to antimicrobials, and ultrastructure. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 1268–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veasey, S. , Muriana, P.M. Evaluation of electrolytically-generated hypochlorous acid (‘electrolyzed water’) for sanitation of meat and meat-contact surfaces. Foods 2016, 5, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travier, L. , Guadagnini, S., Gouin, E., Dufour, A., Chenal-Francisque, V., Cossart, P., Olivo-Marin, J.C., Ghigo, J.M., Disson, O., Lecuit, M. ActA Promotes Listeria monocytogenes Aggregation, Intestinal Colonization and Carriage. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, R. , Jayeola, V., Niedermeyer, J., Parsons, C., Kathariou, S. The Listeria monocytogenes key virulence determinants hly and prfa are involved in biofilm formation and aggregation but not colonization of fresh produce. Pathogens 2018, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colagiorgi, A. , Di Ciccio, P., Zanardi, E., Ghidini, S., Ianieri, A. A Look inside the Listeria monocytogenes Biofilms Extracellular Matrix. Microorganisms 2016, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda-Ruelas, G. , Eslava-Campos, C., Castro-del Campo, N., León-Félix, J., Chaidez-Quiroz, C. Listeriosis en México: importancia clínica y epidemiológica. Salud Pública Méx. 2014, 56, 654–659. [Google Scholar]

- Disson, O. , Moura, A., Lecuit, M. Making Sense of the Biodiversity and Virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 26th ed.; CLSI Supplement M100S; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Blasco, M.D. , Esteve, C., Alcaide, E. Multiresistant waterborne pathogens isolated from water reservoirs and cooling systems. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 105, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Novoa, M.G. , Navarrete-Sahagún, V., González-Gómez, J.P., Novoa-Valdovinos, C., Guerrero-Medina, P.J., García-Frutos, R., Martínez-Chávez, L., Martínez-Gonzáles, N.E., Gutiérrez-Lomelí, M. Conditions of in vitro biofilm formation by serogroups of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from hass avocados sold at markets in Mexico. Foods 2021, 10, 2097. [Google Scholar]

- Stepanović, S. , Ćirković, I., Ranin, L., Švabić-Vlahović, M. Biofilm formation by Salmonella spp. and Listeria monocytogenes on plastic surface. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2004, 38, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain no. | Source | Genetic determinants of virulence | Phylogenetic groups | Serotype | CdCl2 | CPF | Antimicrobial resistance genes | Antibiotic Resistance Pattern | MAR index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lm-11 | Vegetable | LIPI-1 + LIPI-2 | II.2 | 1/2b | R | S | --- | PE-CF-AM-CFX-DC | 0.38 |

| Lm-14 | Vegetable | LIPI-1 + LIPI-2 | II.2 | 1/2b | R | I | Ide | PE-CF-AM-CFX-DC | 0.38 |

| Lm-13 | Vegetable | LIPI-1+ LIPI-2 | II.2 | 1/2b | R | S | msrA + tetM | PE-CF-AM-CFX-DC-TE | 0.46 |

| Lm-17 | Vegetable | LIPI-1 + LIPI-2 | II.2 | 1/2b | R | I | Ide | PE-CF-AM-CFX-DC | 0.38 |

| Lm-18 | Vegetable | LIPI-1 + LIPI-2 | II.2 | 1/2b | R | I | Ide | PE-CF-AM-CFX-DC-CLM | 0.46 |

| Lm-42 | Fruit | LIPI-1+ LIPI-2 | II.2 | 1/2b | S | S | tetM | PE-CF-AM-CFX-DC-CLM-TE | 0.53 |

| Lm-43 | Fruit | LIPI-1+ LIPI-2 | II.2 | 1/2b | S | S | --- | PE-CF-AM-CFX-DC-TE | 0.46 |

| Lm-68 | Fruit | LIPI-1 + LIPI-2 | II.2 | 1/2b | S | I | Ide + msrA | PE-CF-AM-CFX-DC | 0.38 |

| Lm-136 | Fruit | LIPI-1 + LIPI-2 | II.2 | 1/2b | S | I | Ide | PE-CF-AM-CFX-DC-CLM | 0.46 |

| Lm-133 | Fruit | LIPI-1 + LIPI-2 | II.2 | 1/2b | S | S | --- | PE-CF-AM-CFX-DC-CLM | 0.46 |

| Lm-147 | Fruit | LIPI-1 + LIPI-2 | II.2 | 1/2b | S | R | Ide + tetM | PE-CF-AM-CFX-DC-CPF-CLM-TE | 0.61 |

| Lm-138 | Fruit | LIPI-1 + LIPI-2 | II.2 | 1/2b | R | I | Ide | PE-CF-AM-CFX-DC-CLM | 0.46 |

| Lm-19 | Vegetable | LIPI-1+ LIPI-2 + LIPI-3 | I.1 | 1/2a | S | S | tetM | PE-CF-AM-CFX-DC-TE | 0.46 |

| Lm-24 | Vegetable | LIPI-1+ LIPI-2 + LIPI-3 | I.1 | 1/2a | R | S | --- | PE-CF-AM-CFX-DC-CLM | 0.46 |

| Lm-15 | Vegetable | LIPI-1+LIPI-2 + LIPI-3 | I.1 | 1/2a | R | S | msrA | PE-CF-AM-CFX-DC-CLM | 0.46 |

| Lm-27 | Vegetable | LIPI-1 + LIPI-2 + LIPI-3+ LIPI-4 | I.1 | 1/2a | R | R | Ide + tetM | PE-CF-AM-CFX-DC-CPF-CLM-TE | 0.61 |

| Lm-41 | Vegetable | LIPI-1 + LIPI-2+ LIPI-3+ LIPI-4 | I.1 | 1/2a | R | I | Ide | AM-CFX-DC | 0.23 |

| Strain no. | Phylogenetic groups | Serotype | MIC (µg/mL) |

BC | CdCl2 | Biofilm formation (Microtiter plate assays) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lm-11 | II.2 | 1/2b | 6.2 | █ | █ | Moderate biofilm |

| Lm-14 | II.2 | 1/2b | 6.2 | █ | █ | Moderate biofilm |

| Lm-13 | II.2 | 1/2b | 6.2 | █ | █ | Moderate biofilm |

| Lm-17 | II.2 | 1/2b | 6.2 | █ | █ | Moderate biofilm |

| Lm-18 | II.2 | 1/2b | 3.1 | ☐ | █ | Moderate biofilm |

| Lm-27 | I.1 | 1/2a | 3.1 | ☐ | █ | Moderate biofilm |

| Lm-42 | II.2 | 1/2b | 3.1 | ☐ | ☐ | Moderate biofilm |

| Lm-43 | II.2 | 1/2b | 3.1 | ☐ | ☐ | Moderate biofilm |

| Lm-68 | II.2 | 1/2b | 3.1 | ☐ | ☐ | Moderate biofilm |

| Lm-133 | II.2 | 1/2b | 3.1 | ☐ | ☐ | Moderate biofilm |

| Lm-136 | II.2 | 1/2b | 3.1 | ☐ | ☐ | Moderate biofilm |

| Lm-138 | II.2 | 1/2b | 1.5 | ☐ | █ | Moderate biofilm |

| Lm-41 | I.1 | 1/2a | 0.7 | ☐ | █ | Moderate biofilm |

| Lm-147 | II.2 | 1/2b | 0.7 | ☐ | ☐ | Moderate biofilm |

| Lm-19 | I.1 | 1/2a | 0.7 | ☐ | ☐ | Moderate biofilm |

| Lm-24 | I.1 | 1/2a | 1.5 | ☐ | █ | Moderate biofilm |

| Lm-15 | I.1 | 1/2a | 1.5 | ☐ | █ | Moderate biofilm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).