1. Introduction

The foundational years of a child's life are critical for cognitive, language, and motor development, largely influenced risk factors at birth (e.g., birth weight, gestational weight, clinical adverse outcomes), and by their interactions within their immediate environment and with caregivers along the first two years of life. Given the rapid brain growth and maturation of nervous structures during this period, the quality of Early Childcare Centers (ECCs) extends far beyond basic needs such as hygiene, nutrition, and sleep [

1]. It is imperative to foster an environment that encourages interaction with both adults and peers and provides opportunities for exploration under the guidance of trained professionals [

1,

2,

3]; this approach is essential for nurturing development during these formative years.

Traditionally, the primary responsibility for nurturing early development has resided with the family, especially the mother. However, with the increasing need for dual-income households, caregiving responsibilities are frequently outsourced to ECCs [

4], often requiring a premature end to exclusive breastfeeding, an essential protective factor of de elopement, and altering the traditional caregiving dynamic [

4,[4,]. Consequently, infants are trusted to caregivers in ECCs at a younger age [

5]; this shift in. childcare underlines the growing reliance of parents on ECCs. How these changes affect children’s development is still uncertain, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where there is a pronounced gap in evidence on child opportunities and development outcomes within these settings [

6].

ECCs are uniquely settings to mitigate the developmental risks associated with socioeconomic disadvantages [

7,

8]. Lower socioeconomic status often associates with reduced parental education levels, which can adversely affect a child's developmental trajectory [

9]. ECCs not only provide crucial care but also serve as vital strategy to enhance the quality of life for children from economically challenged backgrounds by compensating for the lack of resources and educational opportunities within the home [

10]. Delivering high-quality care in ECCs, characterized by safe learning interactions within a secure environment handled by skilled and supportive staff, is fundamental [

2,

3,

11]. The adequacy of facilities [

8], optimal caregiver-to-child ratios [

12], structured routines [

13], access to educational toys [

9,

14], and staff awareness of developmental milestones [

3], are key indicators of ECC quality. These factors collectively support the child’s development, supplementing familial educational efforts [

2,

10].

Despite the recognized importance of ECCs, disparities exist between the resources and quality of care provided in public versus private centers, particularly in LMICs like Brazil. In Brazil public ECCs are often responsibility of the government, usually with limited coverage, equipment’s, professional training, and resources [

14,

15]. On the other hand, private ECCs frequented by middle and high-income families and have much more available human and equipment resources [

16]. These disparities can significantly impact developmental outcomes for children, warranting focused investigation into the conditions of childcare in these divergent settings [

17].

This study aims to bridge the knowledge gap by first comparing cognitive, language, and motor development outcomes among children in public and private ECCs, considering birth risk factors, family context (e.g., socioeconomic status, maternal education, breastfeeding duration), and daycare environment (e.g., staff experience, daily practices, and knowledge; and developmental opportunities). Additionally, it will examine the proximal and distal risk and protective factors affecting children development. It was hypothesized that children in private ECCs will exhibit higher developmental outcome scores, which would be influenced by better-informed childcare practices and richer developmental opportunities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This study involved children, teachers, and assistants from both public and private Early Childhood Care centers (ECCs) in southern Brazil using a multistage cluster design. The study adhered to ethical research principles outlined in Resolution 466/12 of the National Health Council. The research was approved by the university's ethical committee. Individual informed consent was obtained from children's parents and all professionals enrolled in the study; all ten ECCs participating in the study also provided their institutional informed consent.

In the first phase of selection, ten ECCs were chosen at random from a list of approximately 100 centers, both private and public, accredited by the local education board to serve full-time children aged zero to 24 months from low- and mid-low-income families. The principal researcher obtained consent for participation by reaching out to the education board and the administrators of these institutions, all of whom agreed to participate. In the second phase of selection, children aged 6 to 18 months who attended the ECCs daily and full-time (eight hours a day, five days a week, for at least six months) were randomly selected from each classroom in the chosen ECCs; these criteria of inclusion aiming to ascertain that the opportunities provided for the children’s development were mainly occurring in the collective educational setting. A total of 90 children met these criteria and were selected for the study; children with disabilities were excluded. Teachers and assistants became part of the study only if the children in their care were selected. To ensure clarity and understanding of the study's aims and procedures, the principal researcher conducted meetings with professionals and parents at the ECCs.

The sample size was determining using the G*Power program. For two-group comparisons using one-way ANOVA, a power level of .80, an effect size of .30, and a significance level of p =.050, required a minimum of 90 children. For hierarchical multiple linear regression analysis with fifteen predictors, controlling for age, a moderate effect size (Cohen's ƒ² = .30), a significant level of p = .050, and a power (1 - β) ψ = .80, a minimum sample size of 77 children was recommended. Out of the initially selected 90 children, three were diagnosed during the study with a genetic syndrome, neurological impairment, and visual and auditory deficits, and were therefore excluded. Additionally, three other children did not attend the ECCs on the designated assessment days. After three unsuccessful attempts to reach their parents, these children were also excluded. Consequently, the final sample consisted of 84 children. The adequacy of the final sample was reassessed, revealing that it was sufficient to achieve power of .80 with a moderate effect size (Cohen's ƒ²=.31) at a significance level of p < .050.

Therefore, the sample consisted of 84 children, with 41 boys and 43 girls, evenly distributed across public and private groups. Children's ethnicity, as per the Brazilian Governmental categorization [

18], was also similar across public and private ECCs. Most children were delivered via cesarean section, with no reported complications during delivery. Children attending public and private ECCs came from families of different socioeconomic status -SES. Most children from public ECCs were from families with low SES, while most children from private centers were from middle-low SES [

19]. None of the children lived below the Brazilian poverty line [

18].

Ten teachers and 14 assistants who were responsible for the children's care took part in the study. Each teacher was paired with a teaching assistant, with six teachers having full-time assistants (n = 6) and four teachers having part-time assistants (n = 8). All teachers held teaching degrees and had undergone specific training to care for children in this age group. Similarly, all assistants had completed at least a high school education and received training for childcare. Both teachers and assistants were exclusively female, aged between 25 and 35, and had several years of experience working with children.

Each ECCs had multidisciplinary administrative teams responsible for implementing the pedagogical plan and providing support to educators. The ratio of one teacher to one assistant for every 8 to 12 children adhered to the recommendations of the city board of education. This ratio was determined based on considerations of the pedagogical plan and the physical space available in the ECCs, ensuring that there were no more than six children per adult and a maximum of 18 children per teacher for children aged 0 to 2 years. The ECCs' classrooms were organized based on the children's ages, with separate areas designated for infants aged 6 to 12 months and toddlers aged 12 to 18 months.

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Socioeconomic Status

The Brazilian Economic Classification Criteria [

19] questionnaire was used to assess family SES. This tool evaluates SES by considering factors such as the number of automobiles and rooms in the household, ownership of appliances (e.g., freezer, washing machines, microwave, computers), employment of housekeepers, the education level of the household head, access to public services (e.g., piped water, paved streets), and monthly income. Based on the responses, families receive a score ranging from 0 to 100 points, which, along with the family’s monthly income, determines their classification into one of six categories: D/E (0-16 points, income up to R

$ 826.41), C2 (17-22 points, income up to R

$ 1,894.95), C1 (23-28 points, income up to R

$ 3,194.33), B2 (29-37 points, income up to R

$ 5,721.72), B1 (38-44 points, income up to R

$ 10,788.56), and A (45-100 points, income over R

$ 22,749.24).

2.2.2. Sociodemographic survey

Parents were provided with a survey to fill out, which collected information on the infant's age, sex, ethnicity, gestational age at birth, delivery method, and any complications occurring before, during, or after birth. It also inquired about the infant's APGAR score, general health and care practices, and the duration of breastfeeding.

2.2.3. Children development

The Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development - Third Edition (BSITD-III) [

20] was used to assess children’s motor, cognitive, and language development. This tool assesses infants' performance relative to their age, adjusting for corrected age in the case of premature birth up to 24 months. Widely acknowledged as the gold standard for assessing child development, the BSITD-III provides composite scores and categorization of performance. Scores of 85 or higher fall within the typical development range, while delays are categorized as severe (composite scores below 55), moderate (composite scores from 55 to 69), and mild (composite scores from 70 to 84) [

21].

2.2.4. Teachers' and assistants' knowledge

The Knowledge of Infant Development Inventory (KIDI) [

22], adapted for Brazilian children [

23], was used to assess caregivers' understanding of child milestones. The KIDI comprises 75 questions organized into four behavioral categories: care (i.e., beliefs, behaviors, and responsibilities), developmental milestones (i.e., motor, perceptual, and cognitive skills), principles (i.e., typical and atypical development), and health (i.e., nutrition and prevention of accidents). The total score, ranging from 0 to 100, is calculated by the ratio of correct answers to the total number of questions for each age group.

2.2.5. Teachers' practice

The Daily Activities of Infant Scale (DAIS) [

24] was used to assess the teachers’ practice. The DAIS comprises eight dimensions (i.e., feeding, bathing, changing clothes, nap time, quiet and active games, walking, and sleep). It uses pictures to identify the postures most assumed by the infant during the day, facilitated by the caretaker. Positions requiring less anti-gravitation control receive lower scores (A: low stimulation = 1; B: average stimulation = 2) while those demanding greater challenges receives higher scores (C: more stimulation = 3). Raw scores are provided for each dimension and total scores, ranging from 10 to 24. Only the teachers completed the scale, considering one for each child. In this study, the DAIS was also used to evaluate children aged 12 to 18 months. Adaptation of questions was deemed unnecessary, with expert consensus indicating that the questions were appropriate for this age group, reaching 97% agreement. The DAIS demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency indices (α values ranging from .80 to .85), and test-retest reliability results showed strong Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC values > .90) for assessing the daily care of children aged 12 to 18 months.

2.2.6. Childcare centers’ opportunities for development

The Affordances in the Daycare Environment for Motor Development (ADEMD) [

25] adapted from the AHEMD [

26] and validated for Brazilian children [

27] was used to assess the opportunities available for motor development at the ECCs. The ADEMD assess the potential for children’s development by examining the physical space (e.g., texture, inclinations, stairs, furniture, floor), the variety of daily activities (e.g., postures, use of devices, games), and the availability of fine and gross motor toys. The leading researcher collected the ADEMD information.

2.3. Procedures

The university’s research committee approved the study, which received further endorsement from the education secretary, who provided a list of institutions that enrolled children full-time. The leading researcher carried out the random process to select ten ECCs. Each selected ECCs agreed to participate in the research. The researcher also conducted random selection of children within these institutions. To engage the parents, the researchers organized meetings to outline the study's aims and the informed consent process. Consent forms were distributed to be taken home. For those parents who consented, the researchers detailed the protocols and questionnaires involved in the study.

Sociodemographic questionnaires were given to parents to complete at home and return to the researcher. All teachers and assistants at the ECCs consented to participate, signing the informed consent forms. They were then briefed on completing the KIDI [

22] and the DAIS [

24] individually. The principal researcher collected data for the ADEMD [

25] at each ECC on the initial visit. The data collection took approximately six months and were conducted in the first semester with the support of two doctoral and one undergraduate student. All surveys were completed prior to assessing child development.

The BSITD-III [

21] assessments were carried out in quiet rooms within the ECCs, under the supervision of teachers. Each assessment lasted about 60 minutes per infant. These sessions were recorded to enable later scoring by an independent examiner, ensuring that the process included an inter-rater reliability analysis using the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) for motor, cognitive, and language development scores. The ICC results showed high inter-rater reliability for motor (ICC = .98, 95% CI = .95-.99), cognitive (ICC = .98, 95% CI = .97-.99), and language (ICC = .95, 95% CI = .93-.97) scores.

2.4. Data analysis

Mean, standard deviations and correlations are presented. Chi-square tests and one-way ANOVA were used to compare public and private ECC’s. Cohen’s f

(f) was used as the ANOVA effect size index with recognized cut-offs (Cohen’s

f effect size:

f small = .10 to .24;

f moderate = .25 to .39;

f large

> .40) [

29].

Pearson and Spearman (when appropriate) correlation coefficients test were utilized adopting recognized cut-offs (very weak

r < .10; weak r = .10 to .30; moderate

r = .30 to .50; moderate to strong

r = .50 to .70; strong

r = .70 to .90; very strong

r > .90) [

28]. Hierarchical multiple regression was conducted to test if the independent variables significantly explain the motor, cognitive, and language outcomes. Variables groups were nested in three models. Initially, the first model included age, birth weight, birth height gestational age, mechanical ventilation, APGAR 5 [0] minute, days in the neonatal intensive care unit, and length of breastfeeding as the predictors. In the second model, besides the first mentioned variables, teachers' daily practice, teachers' and assistants' knowledge, teachers' and assistants’ experience, and mothers’ formal education (high school and college) were also predictors. The last model included indoor and outdoor ECCs physical space, fine and gross motor toys, families' monthly income, and ECCs category (public and private). The parameters were estimated using the least square method. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to examine the normality of residuals and a Q-Q plot with standardized residuals from the models was used to assess normality visually. Homoscedasticity was tested using the Breusch-Pagan test and by examining the scatterplot of residuals. The independence of error distribution was examined using Durbin–Watson statistics; values between 1.5 and 2.5 indicated no linear autocorrelation in the data (Ho, 2013). Collinearity was controlled using the VIF (variance inflation factor) test; values above five as indicators of collinearity and those variables were removed from the models. Akaike Information Criteria (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) were used to compare the quality of models; Adjusted R² and ΔR² were presented. Cohen's effect size for hierarchical multiple regression (

f [

2]) was estimated adopting recognized cut-offs (

f [

2] small = .02 to .15;

f [

2] moderate = .15 to .34;

f [

2] large

> .35) [

29] and power values

> .80 as strong; α-level = .050, two-tailed test, were adopted. Three statistical software, SPSS, R studio, and Jamovi 2.4.5 were used.

3. Results

3.1. Public and Private ECCs comparisons

Table 1 presents the results for individual and contextual factors for children at public and private ECCs. The one-way ANOVA showed that children from public and private ECCs had similar results in several individual characteristics. However, birth weight and family monthly income were significantly higher for children from private ECCs. In contrast, breastfeeding was maintained longer for children in public ECCs, with moderate effect sizes. Besides, teachers from public ECCs exposed children to more challenging postures during daily practices. Private ECCs had more suitable outdoor spaces, whereas public ECCs had more suitable indoor spaces.

Table 2 presents the group comparisons for children’s developmental outcomes. The results showed that children from public ECCs had significantly higher cognitive and language composite scores, with small effect size.

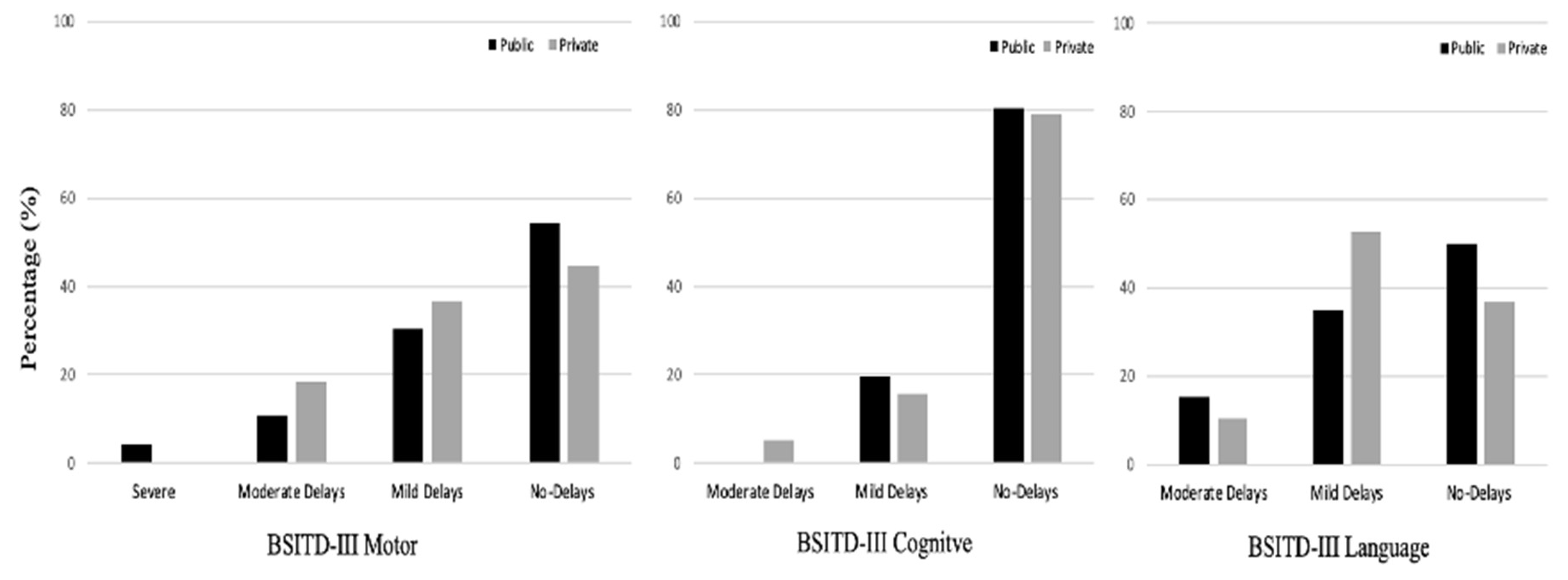

Regarding delay prevalence, although less prevalence of delays was observed for children in public ECCs in motor and language categorization of performance, no significant differences were found (

p > .050). Approximately 50% of the children showed motor delays, 20% cognitive delays, and 55% language delays.

Figure 1 presents the prevalence of delays (severe, moderate, and mild) and typical development [

20].

3.2. Association of risk and protective factors and children’s development

Several procedures were conducted to test the assumptions for the hierarchical regression analysis. The results showed that the normality of residuals was confirmed by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov (

p values > .05) for all models; the Q-Q plot visually also confirmed the normality. The Breusch-Pagan test (

p values > .050) and a scatterplot of residuals indicated the homoscedasticity of the models. The Durbin–Watson statistics indicated the independence of error distribution (values between 1.5 and 2.1). VIF test indicated collinearity (values from 6.1 to 21.5) for several variables (birth height, birth weight, mechanical ventilation, APGAR 5 [0] minute, days in the neonatal intensive care unit, teachers' experience, and assistant’s experience). When age, birth height, APGAR 5 [0] minute, days in the neonatal intensive care unit, and assistant’s experience variables were retrieved, all the models reached non-collinearity. The hierarchical theoretical model was created using the assumptions established by Victora et al (2015) [

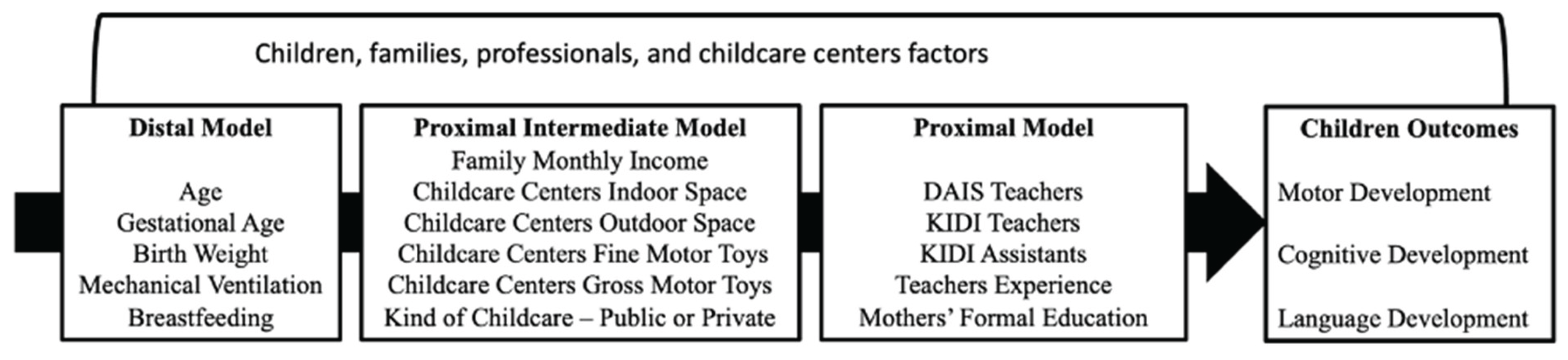

30], organizing all factors according to the proximity to the presented outcomes measured. The selection of the allocation levels of variables for the hierarchical model followed the logic of individual factors, factors in the context of child development, and factors of daily care of the child enrolling individuals and experiences within this daily routine. Three levels of variables were proposed and grouped in hierarchical blocks; those variables met all the statistical assumptions and therefore remained in the model;

Figure 2 presented the model.

Table 3 presents the correlation matrix between all variables that remained in the model. Positive, negative, and moderate/strong to very weak correlations (

r-values varying from -0.01 to 0.87) were observed among variables.

Table 3 presents the correlation matrix between all variables that remained in the model. Positive, negative, and moderate/strong to very weak correlations were observed among variables.

Regarding motor outcome, all three models were significant (mode 1: F(5,70) = 2.26, p < .045; model 2: F(10,65) = 5.65, p < .001; model 3: F(16,59) = 4.30, p < .001). Breastfeeding significantly explained the variance in model 1 (β = .28, p = .017). Breastfeeding (β = .27, p = .008), mechanical ventilation (β = .23, p < .025), and teachers experience (β = .58, p < .001) explained motor variance in model 2. However, when adjusted for all other variables (model 3), teachers’ daily practices (β = .23, p < .046), teachers experience (β = .47, p < .001), and gross motor toys (β = .41, p = .012) better explained the variance in motor scores.

Concerning cognitive outcome, all three models were significant (model 1: F(5,70) = 4.47, p = .001; model 2: F(10,65) = 3.56, p < .001; model 3: F(16,59) = 2.53, p = .005). In model 1, breastfeeding (β = .41, p = .002) explained the variance. In model 2, breastfeeding (β = .38, p = .001), mechanical ventilation (β = .25, p < .025), and teachers’ experience (β = .23, p < .049) explained the variance. However, when adjusted for all other variables (model 3), only breastfeeding (β = .41, p = .002) better explained the variance in cognitive scores.

Concerning language outcome, all three models were significant (mode 1: F(5,70) = 3.40,

p = .008; model 2: F(10,65) = 3.67,

p < .001; model 3: F(16,59) = 3.10,

p < .001). Breastfeeding significantly explained the variance in mode 1 (β = .38, p = .001). Breastfeeding (β = .30, p = .008) and teachers experience (β = .29, p = .014) significantly explained the variance in model 2. However, after adjusting for all other variables (model 3), teachers’ knowledge (β = .31, p = .030) and public ECCs (β = .75, p = .014) better explained the variance in language scores. The results of linear regressions are presented in

Table 4.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to comparing cognitive, language, and motor development outcomes between children in public and private ECCs, considering birth risks, family context, and daycare environment and examine the risk and protective factors affecting development. It was hypothesized that children in private ECCs will exhibit higher developmental scores, which would be influenced by better-informed childcare practices and richer developmental opportunities.

4.1. Public and Private ECC(s) comparisons: Children’s birth weight and breastfeeding

Significant differences were observed between children in public and private ECCs regarding birth weight and breastfeeding duration. Children in public ECCs had significantly lower birth weights, with a moderate effect size noted. All preterm infants (n = 7) in public ECCs had low birth weights (below 2,500 grams), in contrast to just one out of five preterm infants in private ECCs, indicating increased risk factors for children in public settings. Low birth weight, often linked with prematurity, tends to be more common among children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds [

9,

31].

Interestingly, children attending public ECCs were breastfed for longer periods, about seven months, while those in private ECCs were breastfed for approximately five months. This contradicts prior research in Brazil indicating that children from disadvantaged families are less likely to be breastfed [

32,

33]. The observed trend in this study suggests a complex interplay of cultural, economic, and policy-driven factors. For economically disadvantaged families, exclusive and prolonged breastfeeding becomes a feasible, cost-effective alternative to expensive formula milk. Across Brazil, there exists a strong consensus on the importance of extended breastfeeding for a child's health and development, deeply embedding it as a cultural norm [

34]. This practice is further reinforced by Brazilian policies aimed, through public health campaigns, promoting breastfeeding and the dissemination of its benefits. Moreover, the country's maternity leave policy, offering 120 days of full pay, provides mothers with the opportunity for exclusive breastfeeding [

35,

36]. These factors combined underlining the multifaceted influences on breastfeeding practices within the nation.

4.2. Public and Private ECCs comparisons: Families’ monthly income and SES

Children at public ECCs come from families with lower monthly incomes than those at private ECCs, although there were no significant differences in the mothers' formal education levels across both groups. In Brazil, economically disadvantaged families often choose public childcare, if available, primarily due to financial constraints and the pursuit of social and educational benefits for their children. Public ECCs are known to offer essential services at no cost, including structured educational activities, socialization opportunities, nutritious meals, and in some instances, routine health screenings7,11,37,38. Moreover, the public ECCs also provide a safe and supervised environment, reducing the risk of leaving children unattended at home or receiving inadequate care from older siblings. These offerings are particularly critical for low-income families who might otherwise find these services unaffordable.

However, despite Brazil's progressive early childhood education policies [

38,

39,

40], access to public ECCs for low-income families remains a significant challenge. The availability of public childcare has increased in recent decades, yet only 34% of those in need receive services regularly. Priority is given to children from families living in poverty, single-parent households, and those with mothers actively seeking or participating in the workforce [

38]. This approach aims to support the most vulnerable segments of society, as demonstrated by the families in the current study.

The limited availability of public ECCs has compelled a small yet noteworthy fraction of low-income families (7.9%) to stretch their finances to enroll their children in private centers, potentially impacting their economic stability. This scenario highlights the critical role that public ECCs play in not only fostering child development and providing a safe and nurturing environment for children but also in enabling parents, particularly mothers, to pursue employment or further education. By addressing the childcare needs of low-income families, Brazil's public childcare system could serve as a crucial mechanism in reducing social inequalities, underlining the importance of expanding access to quality childcare for all families.

4.3. Public and Private ECCs comparisons: Teacher’s daily practices

In the present study, teachers in the public ECCs provided better opportunities for children to experience challenging anti-gravitational postures during the daily care of the infant, during feeding, bathing, dressing, carrying, playing, and napping time routines than teachers from private daycares. Teachers’ practices in public ECCs are overcoming the traditional routines that focus only hygiene and feeding activities [

24] and had no time for interactions to nurture development previously reported [

9,

11,

14].

Public ECCs face resource constraints that require innovative, creative, and resourceful approaches to daily care by teachers. These educators engage children in activities that do not rely on costly equipment, instead used the available environment. They frequently arrange children in various floor positions for play, minimizing or avoiding traditional equipment such as baby comforts, highchairs, swing chairs, and fences. Simple items like pillows are utilized to support children in diverse postures, fostering engagement and exploration without the need for elaborate equipment. This innovative use of limited resources, coupled with enriched educational experiences for children from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, underscores the adaptability and commitment of teachers in public ECCs to create an inclusive and stimulating learning environment.

4.4. Public and Private ECCs comparisons: Childcare indoor and outdoor space

Public ECCs exhibited higher scores for attributes of indoor physical space, such as floor texture and equipment that facilitates children's stand-up activities, including tables, chairs, benches, and stairs. In contrast, private ECCs demonstrated superior outdoor features, encompassing grass, dirt, sand, sloped surfaces, stairs, and slides. The quality of both indoor classrooms and outdoor areas is key in executing educational programs that bolster children's development [

4]. Access to appropriate physical environments is essential for promoting learning opportunities, ensuring mobility, and enhancing social interactions in ECCs.

The quality of childcare facilities is particularly vital for children from vulnerable families, who might lack adequate physical and developmental opportunities at home [

2,

17]. This study found that the environments where children spend significant time—eight hours per day, five days a week—were predominantly rated as good in both public and private ECCs. While public ECCs provided a broader range of indoor opportunities and private ECCs offered better outdoor facilities, both types of settings adhered to appropriate standards, ensuring children's safety, and supporting teacher functionality.

4.5. Public and Private ECCs comparisons: Children’s development

Children in public ECCs exhibited higher cognitive and language scores than those from private centers, a finding that contrasts with prior research [

14]. This discrepancy raises several considerations. One potential explanation is the implementation of more demanding daily routines in public ECCs, as indicated by the DAIS assessment. Such routines likely enhance children's interactions in the activities on the floor, positively influencing cognitive and language development. Moreover, with public ECCs mostly serving children from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds, teachers’ efforts may be particularly geared toward mitigating environmental factors that could impede cognitive and language development at home. These findings underline the importance of scrutinizing the childcare curriculum and guidelines within ECC programs for a comprehensive understanding of their impact.

The high incidence of developmental delays among infants in both public and private ECCs is concerning, with about 50% exhibiting motor and language delays and around 20% showing cognitive delays. These results align with previous Brazilian studies reporting developmental delays prevalence ranging from 20% to 50% [

3,

41]. The literature also suggests that the high number of children per room in ECCs poses a risk for development [

14,

15,

16]. In this study, both public and private ECCs maintained a standard of one teacher and one assistant per room, with group sizes varying from small ratios (1 teacher to 6 children) to more crowded conditions (up to 1 teacher to 25 children). Such inadequate teacher-child ratios likely limit the necessary individual attention and interactions crucial for optimal development. Enhancing the quality of child-teacher interactions and fostering positive developmental outcomes may require a reduction in teacher-child ratios, a strategy that could beneficially affect care quality in both public and private ECCs in Brazil, thus helping to prevent developmental delays.

4.6. Risk and protective factors associated with children’s motor development: Teachers daily practices and professional experiences, and gross motor toys available for children

The hierarchical regression analysis concerning motor development outcomes revealed significant results across all three models. Initially, in the first two models, the variance in motor outcomes was explained by the length of breastfeeding, the need for mechanical ventilation, and the teacher's experience. However, when adjusting for the other variables, the factors that consistently remained significant in the final model were the teacher's daily practice (evaluated using the DAIS assessment), the teacher's years of experience, and the availability of gross motor toys for children. These variables collectively accounted for 41% of the variance in motor development outcomes.

Teachers' daily practices significantly and positively explained children’s motor development. The results showed that the teachers who were more effective in providing children with opportunities to play actively, on the floor and stand alone when playing, challenge them to acquire demanding postures during feeding (sitting alone or in chairs with minimal support) and during changing clothes (standing up when dressing them) promoted higher motor development levels. The results clearly indicated that teachers with higher scores in their daily practices were the ones who rarely had the children under their care seated in baby comforts or restricted movement chairs, in the cribs, or even caring around. Children under their care spend most of the day on the floor, moving around, exploring, and climbing (upstairs, over objects, or up onto the furniture). The results are aligned with previously studies showed that teachers with high-quality daily practice encourage child experience autonomy, positively impacting motor development [

3,

8,

11].

Additionally, teachers' experience also influenced children motor development. Experienced teachers promote children's motor skills through various activities such as encouraging movement around the room, using furniture and equipment for standing and walking exercises, participating in obstacle courses, dancing, climbing stairs, and engaging in manipulative activities like fitting cubes into boxes and using small objects. Implementing these activities effectively for young children (6 to 18 months) in group settings requires strong leadership, classroom management skills, problem-solving abilities, and decision-making skills. Experienced teachers also demonstrate patience, clear communication, and attentiveness to individual needs while planning and delivering age-appropriate lessons or activities. These skills are honed over years of teaching experience, and experienced teachers maybe be more adept at ensuring the quality of daily childcare processes compared to their less experienced counterparts, potentially leading to higher developmental outcomes for children.

Consistent with prior research, the availability of gross motor toys has been linked to enhanced motor development in children [

7,

9,

42,

43]. These toys, which necessitate the use of larger muscle groups, propel infants towards active engagement in physical activities such as crawling, walking, climbing, and reaching. This active engagement is crucial for strengthening muscles and developing coordination. The presence of toys within a child's reach in their environment fosters opportunities for exploration and engagement in challenging postures, contributing to the creation of meaningful experiences [

7]. Furthermore, gross motor toys facilitate environmental exploration and spatial navigation—whether it involves crawling through tunnels, maneuvering around obstacles, climbing over items, rocking on a horse, or pushing a toy cart. Such activities not only aid children in understanding their bodies' movement in relation to their surroundings but also positively affect their motor skills [

42,

43]. Therefore, gross motor toys are indispensable in supporting the motor development of infants.

4.7. Risk and protective factors associated with children’s cognitive development: Length of breastfeeding

The hierarchical regression analysis revealed significant findings concerning cognitive outcomes across all three models. Initially, in the first two models, factors such as the length of breastfeeding, mechanical ventilation, and teacher’s experience were identified as explanatory variables for cognitive variance. However, when controlling for all other factors, only the length of breastfeeding remained significant in the final model, explaining 24% of the variance in cognitive development. Children breastfed for longer durations (7 months) exhibit higher cognitive scores compared to those breastfed for shorter periods (five months or less).

Research consistently highlights the protective role of breastfeeding in cognitive development, as example in problem solving and memory, with enduring effects across childhood [

30,

44,

45,

46]. Moreover, breastfeeding's positive impact on cognitive development persists even after adjusting for maternal educational level [

44,

47], consistent with the findings of the present study. A plausible explanation for the association between breastfeeding duration and enhanced cognitive scores lies in the increased frequency and duration of interactions between mothers and children. These interactions promote direct verbal vocalizations [

44], thereby influencing the child's responsiveness to stimuli.

4.8. Risk and protective factors associated with children’s language development: Teachers’ knowledge and children’s enrollment in private or public ECCs

Regarding language outcome, the results from the hierarchical regression showed that all three models were significant. Initially, in the first two models, the teachers' experience explained the variance. However, when controlling for all other factors, the ones that remained significant in the last model were teachers' knowledge about children's development and children attending public ECCs, explaining 31% of the variance in language development.

Teachers' knowledge about child development plays a crucial role in shaping interactions and creating enriched environments encouraging language development [

10,

48]. Such knowledge enables teachers to interact more sensitively, understand children's needs better, and support their development in ECC environments. Specifically, teachers with a deeper understanding of developmental milestones and principles are likely better equipped to distinguish between typical and atypical language skills, facilitating early identification and support for children who may require additional assistance or directing families towards further services.

The distinction between children attending public and private ECCs emerges as a significant factor influencing language scores, with children in public ECCs exhibiting higher language development compared to those in private ECCs. This discrepancy likely arises from various factors, including differences in teacher quality, ECC physical environments, SES, and breastfeeding duration. Children in public ECCs benefit from several protective factors, particularly longer breastfeeding periods at home, which have been associated with better language outcomes [

45]. Additionally, they are exposed to high-quality teaching practices and favorable indoor physical spaces for play and exploration, factors that nurture development [

12,

14]. These factors collectively support language acquisition in children attending public ECCs.

It is important to acknowledge that families enrolling their children in public ECCs typically have lower monthly incomes and predominantly belong to low SES backgrounds. Many parents work in manual labor jobs with hourly wages, and in several cases, the mothers serve as the primary providers, necessitating longer hours of ECC attendance for their children. Despite these socioeconomic challenges, the present results suggest that public ECCs play a crucial role in extending family education and providing compensatory opportunities for language development.

5. Strength, limitations, and recommendations to further research

Children attending daily ECC are susceptible to several risk and protective factors, leading to different developmental outcomes, and this intricate process was investigated in the present study. Examining sociocultural variables (i.e., SES, family income, teachers' and assistants' knowledge, teachers' daily practices) in the context of collective non-parental childrearing is also a strength in the present study, there is still a considerable gap of evidence regarding how teachers' knowledge is related to child development in the first two years of life. Moreover, investigating how ECCs opportunities for children’s development are organized to nurture child development is another strength of this study. Furthermore, this study enrolled children from low and middle-income families in an LMIC; research for children from LIMIC countries – most of the world, is still scarce. Children's exposure to risks and the diversity of sociocultural factors lead to different trajectories of development in LMICs; these factors need to be examined, and specific strategies for ECCs must be implemented considering this cultural and economic diversity.

This study has several limitations. First, the study examined teachers' practices and knowledge. However, it was limited regarding exploring other domains of teachers' behaviors on which teacher knowledge may have an impact, such as demonstration of affection, empathy to the child's needs, dyads of interaction, and use of disciplinary actions. Also, the mother/child behaviors that occur during breastfeeding that could affect child development were not examined; we only examined the duration of breastfeeding; research must address this issue so that a better understanding of potentially protective factors that affect cognitive, motor, and language development in the first years of life. Therefore, future research should also address the teacher's and mothers' daily behaviors more in-depth; qualitative approaches may be exciting to these factors. Second, although it is not the focus of the present study, a longitudinal design addressing professional practice and knowledge and the impact on child development could provide insight into this complex multifactorial process of childrearing in collective environments. Third, we did not control for the effect of families' quality of care provided to the children when they return home at the end of the day. It is essential to highlight that the children stay eight hours in the ECC(s), with the time at home for the involvement of parents in child stimulation processes restricted to nights and weekends. However, responsive parents, even for a short time, can enhance child development; consequently, it was a limitation in the present study. Fourth, our sample size, although not small, did not allow for a further subdivision of the sample in the analysis (i.e., children with and without cognitive, language, and motor delays in public and private centers), understand how the factors addressed in the present study are related or different among these children could provide further insights to children development, a recommendation to further studies.

6. Conclusion

The results highlight the need for guidelines and investments to improve the quality of children’s experiences in the ECCs, in different features for public and private. Unambiguously in the present study, it is necessary to improve the public and private centers', teachers', and assistants' knowledge about children's development (means around or below 50% of correct answers), as well as their practices, and provide appropriate outdoor space for children from public ECC, and indoor for children from the private ECC. These findings reinforce the need for surveillance and promotion of educational opportunities for children at ECC(s), with critical attention to children more susceptible to risks or manifesting delays. This assumption is even more relevant to low-income families since those children are more likely to have combined risk factors due to lower SES, may have fewer home opportunities for development, and have mothers that are more driven to the workforce. Public policies should focus on strongly subsiding public ECCs, monitoring children's development, promoting teachers' accreditation and training, developing guidelines toward children's full developmental potential, and consolidating the right of every child in a LIMIC to have access to high-quality childcare. However, private centers must also be monitored by the educational council and receive incentives to improve the quality of care for these children. By outlining the intricate relationship between ECC environments and child development, particularly in the context of socioeconomic disparities, this study provided evidence to inform policy and practice, ensuring that all children, irrespective of background, have access to nurturing and developmental opportunities in their early years.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Alessandra Bombarda Müller and Nadia Cristina Valentini; Methodology, Alessandra Bombarda Müller, Helena Cristina V.S. Vieira, Glauber Carvalho Nobre and Nadia Cristina Valentini; Formal analysis, Helena Cristina V.S. Vieira, Carolina Panceri, Glauber Carvalho Nobre and Nadia Cristina Valentini; Investigation, Alessandra Bombarda Müller; Data curation, Alessandra Bombarda Müller and Carolina Panceri; Writing – original draft, Helena Cristina V.S. Vieira, Carolina Panceri and Glauber Carvalho Nobre; Writing – review & editing, Alessandra Bombarda Müller and Nadia Cristina Valentini; Project administration, Nadia Cristina Valentini; Funding acquisition, Nadia Cristina Valentini.

Funding

This research was funded by CNPq and CAPES, grant number Student scholarship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research was approved by the university's ethical committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Individual informed consent was obtained from children's parents and all professionals enrolled in the study; all ten ECCs participating in the study also provided their institutional informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request..

References

- Hentschel, E. Tran, H. T.T., Nguyen, V. H., Tran, T., & Yousafzai, A.K. (2023). The effects of a childcare training program on childcare quality and child development: Evidence from a quasi-experimental study in Vietnam. Children and Youth Services Review, 147, 106844. [CrossRef]

- Burchinal, M. (2018). Measuring early care and education quality. Child Development Perspectives, 12(1), 3–9. Available online: https://srcd.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/cdep.12260.

- Valentini, N.C. Almeida, C.S., & Smith, B.A. (2020). Effectiveness of a home-based early cognitive-motor intervention provided in daycare, home care, and foster care settings: Changes in motor development and context affordances. Early Human Development, 151, n 105223. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0378378220303480.

- Pereira, G.D. Dean, D., & Dean, P.M. (2020). Childcare outside the family for the under-threes: cause for concern? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 113(4), 140-142. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0141076820903494.

- Bai, D.L. Fong, D.Y.T. (2014). Tarrant M. Factors associated with breastfeeding duration and exclusivity in mothers returning to paid employment postpartum. Maternal Child Health Journal. 19, 990–999. [CrossRef]

- Draper, C.E.; et al. (2020). Publishing child development research from around the world: An unfair playing field resulting in most of the world's child population under-represented in research. Infant and Child Development, e2375, 1-13. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/icd.2375.

- Pereira, K.R.G. Valentini, N., & Saccani, R. (2016). Brazilian infant motor and cognitive development: Longitudinal influence of risk factors. Pediatrics International, 58(12), 1297–1306. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ped.13021.

- Zajonz, R. Müller, A.B., & Valentini, N.C. (2008). A influência de fatores ambientais no desempenho motor e social de crianças da periferia de Porto Alegre. Revista da Educação Física/UEM, 19(2), 159-171. Available online: http://www.periodicos.uem.br/ojs/index.php/RevEducFis/article/view/3220.

- Saccani, R. , Valentini, N.C., Pereira, K.R., Müller, A.B., & Gabbard, C. (2013). Associations of biological factors and affordances in the home with infant motor development. Pediatric International 55(2), 197–203. [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroeck, M. Lenaerts, K., & Beblavy, M. (2018). Benefits of Early Childhood Education and Care and the Conditions for Obtaining Them. European Expert Network on Economics of Education: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2018. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/14194adc-fc04-11e7-b8f5-01aa75ed71a1/language-en.

- Müller, A.B. , Saccani, R., & Valentini, N.C. (2016). Impact of compensatory intervention in 6- to 18-month-old babies at risk of motor development delays. Early Child Development and Care, 187, p.1707-1717. [CrossRef]

- Vandell, D.L. , Belsky, j., Burchinal, M., Vandergriff, N., Steinberg, L. (2010). Do effects of early child care extend to age 15 years? Results from the NICHD study of Early Child Care and Youth Development. Child Development, 81(3), 737-756. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1467-8624.2010.01431.x\.

- Werner, C.D. Linting, M., Vermeer, H.J., & Van IJzendoorn, M. (2016). Do Intervention Programs in Child Care Promote the Quality of Caregiver-Child Interactions? A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Prevention Science, 17, 259–273. [CrossRef]

- Felício, L.R. Morais, R.L.S., Tolentino, J.A., Amaro, L.L.M., & Pinto, S.A. (2012). The quality of public centers and development of economically disadvantaged children in a municipality Jequitinhonha Valley: a pilot study. Revista Pesquisa em Fisioterapia, 2(2), 70-82. [CrossRef]

- Attanasio, O. , Paes de Barros, R., Carneiro, P., Evans, D., Lima, L., Olinto, P., Schady, N, (2017). Impact of free availability of public childcare on labour supply and child development in Brazil. New Delhi: International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie).

- Evans, K.D. Kosec, K.L. (2011). Early child education: making programs work for Brazil's most important generation: Educação Infantil: Programas para a Geração Mais Importante do Brasil (Portuguese). Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/437551468226169400/Educação-Infantil-Programas-para-a-Geração-Mais-Importante-do-Brasil.

- Leroy, Gadsden, Guijarro, 2012). Leroy. J.L., Gadsden, P., Guijarro, M. (2012). The impact of daycare programmes on child health, nutrition, and development in developing countries: a systematic review. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 4(3), 472-496. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/19439342.2011.639457.

- IBGE – Brazilian institute of Geography and statistics (2021). City and States. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/cidades-e-estados/rs/porto-alegre.html?

- ABEP – Associação Brasileira de Empresas de Pesquisa (Brazilian Economic Classification Criteria) (2021). Available online: https://www.abep.org/criterio-brasil.

- Bayley, N. (2006). Bayley scales of infant and toddler development: administration manual. (3th ed.) Harcourt assessment.

- Johnson, S. Moore, T., & Marlow, N. (2014). Using the Bayley-III to assess neurodevelopmental delay: which cut-off should be used?. Pediatric research, 75(5), 670–674. [CrossRef]

- MacPhee, D. Manual: Knowledge of infant development inventory -KIDI (1981).Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina.

- Nobre-Lima, L. Vale-Dias, M.L., Mendes, T., Mónico, L., & Macphee, D. (2014). The Portuguese version of the Knowledge of Infant Development Inventory-P (KIDI-P). European Journal of Development Psychology, 2014, 11, 740–745.

- Bartlett, D.J. Fanning, J.K., Miller, L., Conti-Becker, A., & Doralp, S. (2008). Development of the daily activities of infant scale: A measure supporting early motor development. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 50(8), 613-617. [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.B. Valentini, N.C. (2014). ADEMD – IS - Affordance in the Daycare environment for Motor Development -Infant Scale (2014). Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/367221970_Affordances_in_the_Daycare_Environment_for_Motor_Development-Infant_Scale_-ADEMD-IS_English_version.

- Caçola, P. Gabbard, C., Santos, D.C., & Batistela, A.C.T. (2011). Development of the Affordances in the Home Environment for Motor Development - Infant Scale. Pediatrics International, 2011, 53(6), 820-825. [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.B. Valentini, N.C., & Bandeira, P.B. (2017). Affordances in the home environment for motor development: validity and reliability for the use in daycare setting. Infant Behavior and Development,46, 138–145. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28433877/.

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155–159.

- Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences – Second edition. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates (1988).

- Victora, C. G. , Horta, B. L., Loret de Mola, C., Quevedo, L., Pinheiro, R. T., Gigante, D. P., Gonçalves, H., & Barros, F. C. (2015). Association between breastfeeding and intelligence, educational attainment, and income at 30 years of age: a prospective birth cohort study from Brazil. The Lancet. Global health, 3(4), e199–e205. [CrossRef]

- WHO - World Health Organization (2018). Preterm Birth. Fact sheets.

- Boccolini, C. S. Carvalho, M. L., & Oliveira, M. I. C. (2015). Factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of life in Brazil: a systematic review. Revista De Saúde Pública, 49. [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.S. Barros, F.C., Horta, B.L., Menezes, A.M.B., Bassani, D., Tovo-Rodrigues, L., Lima, N.P., & Victora, C.G. (2019). Pelotas Cohorts Study Group. Breastfeeding exclusivity and duration: trends and inequalities in four population-based birth cohorts in Pelotas, Brazil, 1982-2015. International Journal of Epidemiology, 1, 48(Suppl 1): i72-i79. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kalil, I.R. Aguiar, A.D. (2023). The good breastfeeding mother: maternal perceptions about breastfeeding and weaning. Physis: Revista de Saúde Coletiva, 33, e33090. Available online: https://www.scielosp.org/article/physis/2023.v33/e33090/pt/.

- Boccolini, C. S. Boccolini, P. de M. M., Monteiro, F. R., Venâncio, S. I., & Giugliani, E. R. J. (2017). Breastfeeding indicators trends in Brazil for three decades. Revista de Saúde Pública, 51, 108. [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, F.R. Buccini, G.D.S., Venâncio, S.I., & da Costa, T.H.M. (2017). Influence of maternity leave on exclusive breastfeeding. Journal of Pediatrics (Rio Janeiro), 93(5), 475–81.

- Carniel, C.Z. Furtado, M.C.C., Vicente, J.B., Abreu, R.Z., Tarozzo, R.M., Cardia, S.E.T.R., Massei, M.C.I., & Cerveira, R.C.G.F. (2017). Influence of risk factors on language development and contributions of early stimulation: an integrative literature review. Revista CEFAC, 19(1):109-118. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/j/rcefac/a/VGrstgWgMdcJyHr5stDfpyP/?format=pdf&lang=en.

- Fundação Maria Cecilia Souto Vidigal (2022). Todos pela Educação & Fundação Maria Cecilia Souto Vidigal. Early Childhood: Early Childhood Policy Recommendations for Federal and State Governments, Todos pela Educação: São Paulo, Brazil, 2022.

- Brazilian government (2016). Early Childhood Legal Framework. Lei 13.267 de 8 de Março de 2016. Available online: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2015-2018/2016/lei/l13257.htm (accessed on 05 April 2024).

- Raikes, A. Alvarenga Lima, J.H.-N., &Abuchaim, B. (2023). Early Childhood Education in Brazil: Child Rights to ECE in Context of Great Disparities. Children, 10, 919. [CrossRef]

- Aristizábal, L.Y.G. , Rocha, P.R.H., Confortin, S.C., Simões, V.M.F., Bettiol, H., Barbieri, M.A., & da Silva A.A.M. (2023). Association between neonatal near miss and infant development: the Ribeirão Preto and São Luís birth cohorts (BRISA). BMC Pediatrics,18,23:125. [CrossRef]

- Fowler, A. (2017). What Degree Does the Home Environment Contribute to Gross Motor Skill Development in Young Children?" Kinesiology Class Publications, 1, 2-10. Available online: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/kinpapers/1.

- Valadi, S. Gabbard, C. (2020) The effect of affordances in the home environment on children’s fine- and gross motor skills, Early Child Development and Care, 190(8), 1225-1232. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/action/showCitFormats?doi=10.1080%2F03004430.2018.1526791.

- Bartels, M. van Beijsterveldt, C.E., & Boomsma, D.I. (2009). Breastfeeding, maternal education and cognitive function: A prospective study in twins. Behaviour Genetics, 39, 616–622. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19653092/.

- Leventakou, V. et al (2015) Breastfeeding duration and cognitive, language and motor development at 18 months of age: Rhea mother-child cohort in Crete, Greece. Journal of Epidemiology Community Health, 69, 232–239. [CrossRef]

- Oddy, W. H. Robinson, M., Kendall, G.E., Li, J., Zubrick, S.R., & Stanley, F.J. (2011) Breastfeeding and early child development: A prospective cohort study. Acta Paediatrica, 100(7), 992-9, 2011. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21299610.

- Lee, H.; et al. (2016). Effect of Breastfeeding Duration on Cognitive Development in Infants: 3-Year Follow-up Study. Journal of Korean Medicine Science, 31(4), 579-84. [CrossRef]

- Arace, A. , Prino, L.E., & Scarzello, D. (2021). Emotional Competence of Early Childhood Educators and Child Socio-Emotional Wellbeing. International Journal of Environment Research and Public Health, 18, 7633.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).