1. Introduction

Sustained systemic inflammation exists within many chronic diseases, including diabetes (DM) [

1], cancer (CA) [

2], obesity [

2], cardiovascular disease (CVD) [

3], hypertension (HTN) [

1], and chronic venous leg ulcers (CVLUs) [

4]. There is also substantial evidence linking low socioeconomic status (SES) with higher rates of inflammation [

5] and chronic disease [

6]. Preventing and treating chronic diseases relies on the identification of early-stage inflammatory biomarkers [

7]. The novel inflammatory adipokine biomarkers, leptin, and adiponectin, regulate many bodily functions including inflammation [

8].

Lifecourse theory proposes that not one event or factor affects disease states, but many events and many factors, over time, contribute to an ‘allostatic load’, or chronic exposure to elevated or fluctuating endocrine hormone or neural responses, that an individual experiences as stressful, resulting in an increase of disease processes [

9]. Numerous factors with behavioral, biological, psychological, and environmental origins cause inflammation. Factors of each type (i.e., behavioral, biological, etc.) interact with factors of other types. For instance, a person with low SES may eat an unhealthy diet due to an inability to access healthy food sources. This diet may lead to obesity, abnormal gut microbiota, and exposure to food-related toxins. A lower SES may also cause increased stress exposure. Additionally, persons with lower SES tend to live in communities with higher pollution than other communities [

10]. Each of these exposures influence the person’s biological physiology, and an ‘accumulation of risks’ occurs [

9]. Presently, it is unknown through which pathway(s) underlying mechanisms influence leptin and adiponectin. Therefore, the study of low SES risk accumulation to identify disease processes/mechanisms and treatments, therapies, preventions, and community advancements is critical to reduce these risks.

This paper will discuss the association between low SES and factors contributing to chronic inflammation. Additionally, we propose a model that links low SES to chronic disease, mediated by inflammation; describe the use of leptin and adiponectin as both early and chronic inflammatory biomarkers; and identify multi-level interventions to alleviate health disparities related to SES.

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. Aging

With recent advances in science and medicine, people live longer now than ever before. Diseases eradicated by vaccinations, such as measles and mumps, no longer threaten the lives of those infected. Resources sent to developing countries increase the life expectancy of citizens in those countries. In 2019, 1 in 11 people in the world were 65 or older, by 2050 this number will increase to 1 in 6 people being 65 or older [

11]. Specifically in the United States from 1945 to 1965 there was a significant increase in births, now known as the Baby Boom. Since then, at every great milestone, this generation of Baby Boomers requires an expansion of resources to meet increased needs. Baby Boomers make up the largest subpopulation in the United States. In fact, by 2050, nearly 88 million people (more than twice the population of California) will be over the age of 65 [

12], attributed in large part to Baby Boomers. Thus, the combination of aging Baby Boomers and increased life expectancy due to advances in technology and medicine creates an enormous population at risk for chronic diseases.

2.2. Chronic Diseases in Aging

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP), chronic diseases such as DM, CA and CVD are the primary cause of death and disability in the United States [

13]. Moreover, it is estimated that 95% of Medicare costs are allocated for the treatment of chronic illnesses and 90% of the nation’s

$4.1 trillion in annual health care expenses are for people with chronic and mental health disorders [

13]. Given the significant health and economic costs associated with chronic diseases, prevention or managing symptoms more effectively may help reduce these costs.

Unremittent low-grade systemic inflammation, known as inflammaging, is involved in the pathobiology of many chronic diseases more common to older adults, such as CVD, DM, HTN, Alzheimer’s disease, and CVLU’s [

14]. As such, low-risk interventions targeting factors that contribute to chronic systemic inflammation may help prevent many chronic diseases. The study of interventions targeting inflammation can lead to interventions that assuage symptoms and costs associated with chronic disease.

2.3. Inflammation

When an individual is exposed to trauma or illness, acute inflammation employs adaptation and necessary biological processes to return to a state of health. Increased blood flow, increased capillary permeability, released inflammatory mediators, and migration of leukocytes to cells involved in inflammation cause fatigue, muscle aches, fevers, redness, swelling and a general feeling of being markedly ‘unwell’ [

15]. Typically, acute inflammation resolves, and the cells and body return to a state of homeostasis.

The accumulation of exposures to inflammatory agents, such as toxins and stress, over a lifespan influence chronic inflammation or disease [

16]. These exposures can either recur as in many separate events over time, such as long-term smoking, or occur constantly without break, such as environmental toxins (i.e., smog) [

7]. The lack of resolution of inflammatory processes results in further involvement of other cells, organs, and systems throughout the body, allowing chronic inflammation to become widespread [

17]. Thus, chronic inflammation leads to systemic inflammation. In systemic inflammation, unlike acute inflammation, persons may experience no symptoms [

18]. Despite this, the bodies of those experiencing systemic inflammation endure ramifications of inflammation processes such as tissue degeneration and other biological damage that occurs [

18].

For example, over the last 20 years, researchers have demonstrated that inflammation plays a significant role in the development of CVD. Inflammation causes pathophysiologic changes in the peripheral vasculature and heart. Inflammatory markers form adhesion molecules binding to endothelial cells which leads to the formation of atherosclerotic plaques and encourages macrophages to line the artery intima (layer of artery under endothelium) causing increased vascular hypertrophy, vasoconstriction, and HTN [

19]. Long-term effects of these processes cause stress on the heart and blood vessels, resulting in chronic disease. Therefore, by reducing inflammation and associated processes improved cardiovascular outcomes will result [

20].

Inflammation also plays a role in CA development, treatment, and treatment response [

21]. Thirty-five percent of CAs can be linked to diet, 30% to tobacco usage or inhaled carcinogens, and 20% to chronic infection or inflammation, and 90% to environment or acquired genomic variations [

15] and it is estimated that more than 42% of all CAs in the U.S. are preventable [

22]. Indeed, inflammation induces tumor development in several ways [

23]. Several ways inflammation enhances CA development and progression is through chronic inflammation, infections, or autoimmunity [

21,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. These pathways increase genetic mutations, genomic instability, tumor promotion, and angiogenesis [

25,

30,

31,

32]. Once a tumor begins to develop, tumor-associated-inflammation boosts CA progression through the inability of the body to naturally kill CA cells, stimulating tumor growth; increases genomic instability, immunosuppression, and metastasis [

33,

34,

35,

36].

Additionally, the association of inflammation to diabetes has been well established. An individual’s biological, psychological, environmental, and behavioral factors influence adiposity and thus, insulin resistance, glucose sensitivity, and pancreatic islet malfunction [

37]. This results in muscle cells unable to effectively metabolize systemic glucose, which has been increased by the liver. This results in hyperglycemia and a diagnosis of DM. Hence, treating inflammation may result in improved glucose uptake and insulin sensitivity [

7,

37].

2.4. Inflammatory Markers

Historically the primitive understood purposes and functions of adipose tissue were that it served to store energy, cushion vital organs, and provide insulation for the body’s means of thermoregulation. However, it is now known that adipose tissues functions as an endocrine organ and produces adipokines. Individuals who are overweight or obese produce adipokines in discordance compared to normal weight individuals [

38]. Adipose tissue also increases adipokine production during the aging process, thus creating an accumulation of risk over time in those who are overweight [

38]. Also, those from a low SES have a greater risk of obesity, thus, higher risk for overproduction of adipokines [

39,

40].

Leptin and adiponectin are two adipokines of interest to researchers, due to their location being further upstream than currently used biomarkers. Leptin is an important biomarker of inflammation and an indicator of total body fat status. It is a key regulator of appetite, metabolism, and bone mass [

41]. Obesity leads to increased production of leptin and inflammation at many levels. In adolescents, overweight or obese individuals have significantly higher (nearly 5-fold) leptin levels than their normal weight counterparts [

42]. Leptin levels of overweight/obese individuals remain higher in young adulthood [

43], and in older adults compared to normal weight counterparts [

44]. Leptin increases oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, atherosclerosis and left ventricular hypertrophy [

45], all of which have significant health implications. Overweight individuals exposed to chronically increased levels of leptin may develop leptin resistance [

8,

46]. The effect of leptin resistance on chronic inflammation is not fully understood currently.

Although released by adipose tissue, adiponectin is not directly influenced by body fat percentage [

47]. Low levels of adiponectin lead to proinflammatory responses and increased levels are associated with anti-inflammatory responses indicating adiponectin could be a valuable anti-inflammatory biomarker [

48]. Beneficial anti-inflammatory effects of adiponectin include decreased inflammation, apoptosis, oxidative stress, and increased vasodilation [

48]. Importantly, adiponectin is significantly positively associated with SES [

49]. In those from low SES adiponectin levels are lower than other SES groups. It is believed that effects of adiponectin are associated with increased glucose transport and fatty acid oxidation [

46]. Leptin and adiponectin both have several other important roles in humans. Despite this, leptin and adiponectin are ideal candidates to use for inflammatory biomarkers due to their location in the inflammatory cascade being earlier than other biomarkers, and their closer correlations to inflammation effects than other markers [

50,

51].

Currently, c-reactive protein (CRP) is most often used as an acute phase inflammatory biomarker. CRP is used most regularly as the predictor of chronic disease [

52]. However, leptin induces CRP production [

41,

53,

54,

55,

56]. Therefore, leptin, not CRP, should be considered as an early-stage inflammatory biomarker for clinical and research purposes in chronic disease treatment and prevention. It is also understood that adiponectin levels may affect the production of CRP. When adiponectin levels are low, as often seen in people with obesity, DM, and CVD, the proinflammatory effect of CRP can be amplified [

57,

58,

59]. This correlation makes no exclusion about whether adiponectin could possibly have a role in the regulation of CRP production. Thus, leading researchers to believe adiponectin may serve as a better inflammatory biomarker to quantify over CRP.

The leptin-to-adiponectin ratio (LAR, calculated as (Leptin ng/mL)/(Adiponectin mcg/mL) ) could be more accurate in determining total inflammatory status than leptin or adiponectin alone. Additionally, since leptin and adiponectin have more upstream marker performance than CRP, identifying inflammation prior to tissue and organ damage is more likely. This potentially could lead to LAR being used in the clinical setting to establish interventions in preventing disease.

2.5. Low Socioeconomic Status

In 2018, the U.S. Census Bureau recorded that 38.1 million people, 11.8% of the total US population, lived below the poverty level [

60]. Poverty disproportionately affected women as compared to men, as well as Black and Hispanic/Latino people were disproportionately affected compared to white and non-Hispanic/non-Latino people [

60]. The understanding is that, in the United States, many factors of an individual’s overall status of health are heavily influenced by their SES. One factor that can be most largely affected is a person’s environment.

The differences between environments for SES groups account for some, but certainly not all, of the differences in health outcomes [

61]. These differences occur on multiple nested levels, meaning each level is nested within a larger level (e.g., neighborhood, city, county, state, nation). These differences should be considered when applying health interventions. SES inequalities continue, at all levels, despite moderate attempts in policy to correct them [

62]. Increased violence, pollution, and unreliable social capital are environmental factors that are more likely to occur in low SES communities [

5,

10]. Increased family conflicts plague low SES families due to financial hardships and complicated routines that include competing demands, (e.g., one parent home where the parent works two or three part-time jobs to make ends meet, or a two-parent home where there is only one vehicle for transportation) [

63,

64,

65]. All the above-described issues, that persons in low SESs face, increase the likelihood of abnormally high inflammation due to stress in the body though the exact mechanism is yet to be determined.

Individuals from the lowest SES, incomes lower than 100% of poverty level, experience the worst health outcomes, including lower life expectancy, more limitations of physical activity, and higher incidence of DM, obesity, and CVD [

66,

67]. Defining and measuring SES is challenging. Proxy measures for SES include income, education, and occupation [

68]. However, these indicators do not measure the same SES phenomena or etiology [

68,

69], and should not be used interchangeably. Taking all three indicators into consideration may better elucidate associations between SES, inflammation, and chronic disease. Although exact sensitivity and specificity measures have yet to be determined, recent studies show a strong relationship between SES and chronic inflammation [

3,

5,

70,

71]. Furthermore, it has yet to be determined if blood-based inflammation biomarkers can distinguish changes enhanced by interventions targeting SES.

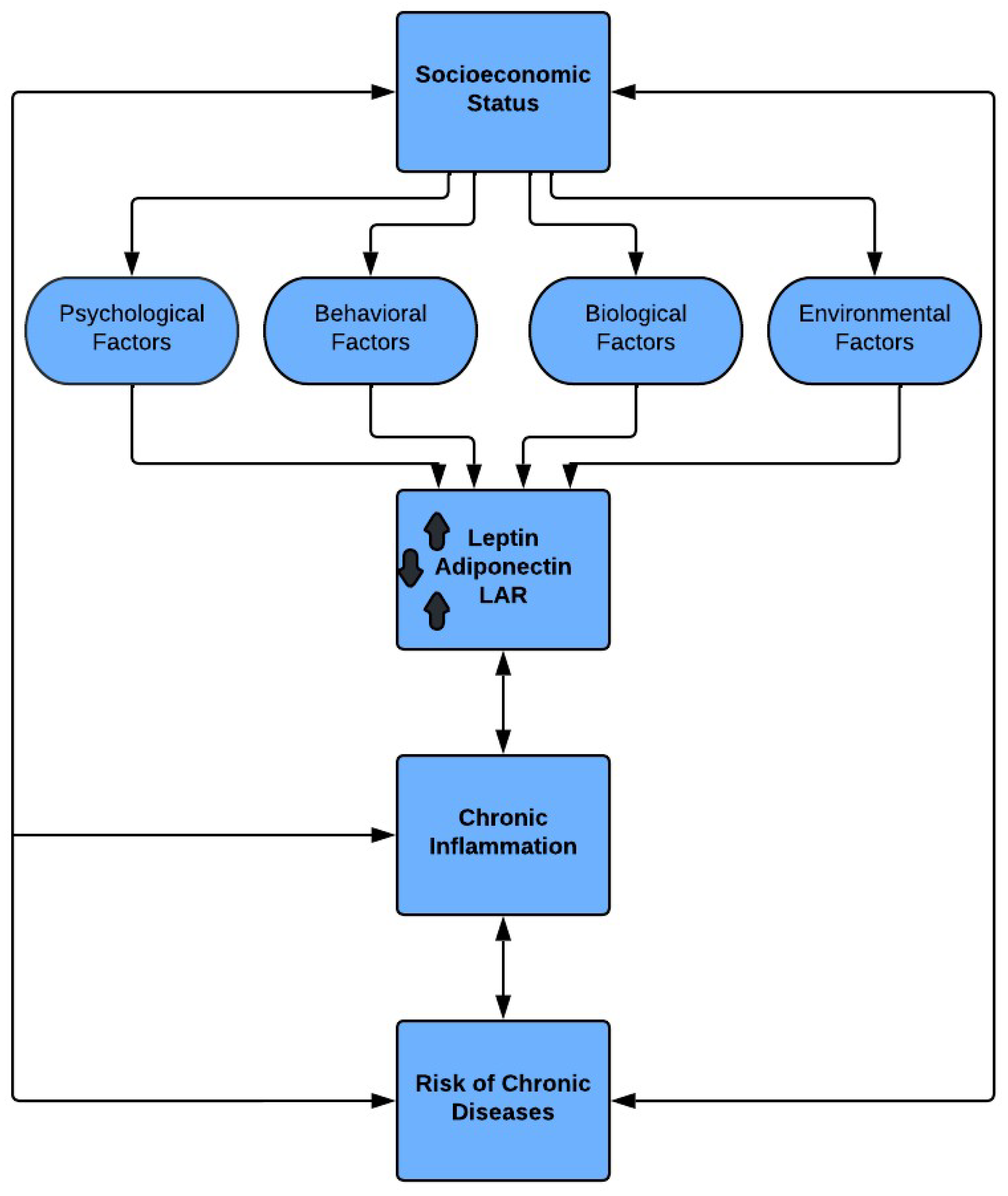

3. Proposed Framework and Pathway

The proposed framework and pathway are based on the lifecourse theory of increased inflammation leading to chronic diseases in persons from low SES. Increased risk of chronic disease in persons from low SES backgrounds is believed to be due to increased exposure to inflammatory factors compared to other groups. Most factors that influence inflammatory pathways fall into one of four categories, psychological, behavioral, biological, and environmental. Thus, we propose the model shown in

Figure 1.

3.1. SES, Psychological Factors, and LAR

Psychological factors, such as stress, emotional state, personality, and affect are exposures that influence disease [

72]. Each of these factors may be different in a low SES group. For example, rates (prevalence) of depression in individuals with low SES are higher, as are negative emotions such as anger and rage [

72]. These negative emotions cause mental stress and fatigue which leads to feelings of social defeat and isolation [

72], resulting in long-term or chronic stress responses [

73]. As previously demonstrated, chronic stress leads to inflammation thus reflected in fluctuations of the LAR.

3.2. SES, Behavioral Factors, and LAR

The health behaviors of people greatly affect their health outcomes. Persons from low SES are less likely to eat a nutritious diet and participate in physical activity [

61], which may be in part due to lower health literacy and health care access. Indeed, individuals from low SES are more likely to engage in risky health related behaviors with higher incidences of smoking, [

74], alcohol or illegal drugs [

75,

76], and safety behaviors (e.g., sunscreen usage) [

61]. Each risky behavior increases the likelihood of chronic inflammation and in-turn risks of chronic disease.

3.3. SES, Biological Factors, and LAR

Biological factors, including genetic factors altered by low SES, occur throughout the lifespan, resulting from and to more inflammation [

61]. In fact, SES in early life predicts monocyte aging [

77], produces over-expression of genes that activate pro-inflammatory pathways [

3], increases stress signaling [

78], and influences DNA methylation of inflammatory genes later in life [

79]. As inflammation increases with age, inflammaging is present, there is an increase in risk of chronic disease diagnoses in older adults.

3.4. SES, Environmental Factors, and LAR

Low SES persons often live in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities due to the lack of affordable housing in more advantaged areas. Low-income housing communities are often in areas with higher incidence of environmental pollution from industry and increased traffic [

80,

81,

82,

83], and lack of access to a guaranteed or safe water connection [

84]. Older homes and buildings, in low SES neighborhoods contain higher levels of hazardous materials such as asbestos and lead paint [

5]. Poor neighborhoods are also characterized by violence, social and physical disorder – which can contribute to stress and maladaptive coping behaviors such as substance use. Additionally, poor neighborhoods have less green space and walkable areas to promote physical activity. Violence, too, can lead to people staying indoors and lack of physical activity due to fears for safety. A lack of influential residents in the community may result in less effort from public officials to make appropriate changes to these areas.

3.5. SES, LAR, Chronic Inflammation, and Risk of Chronic Disease

Mechanisms of the link between SES and health are complex. However, many factors that contribute to adverse health outcomes are inflammatory in nature. For example, although obesity is a direct result of low SES, and inflammatory markers increase with obesity, the inflammation resulting from low SES cannot be accounted for by obesity alone [

3]. Differences in SES environments, or other factors, may account for differences in health outcomes between SES groups.

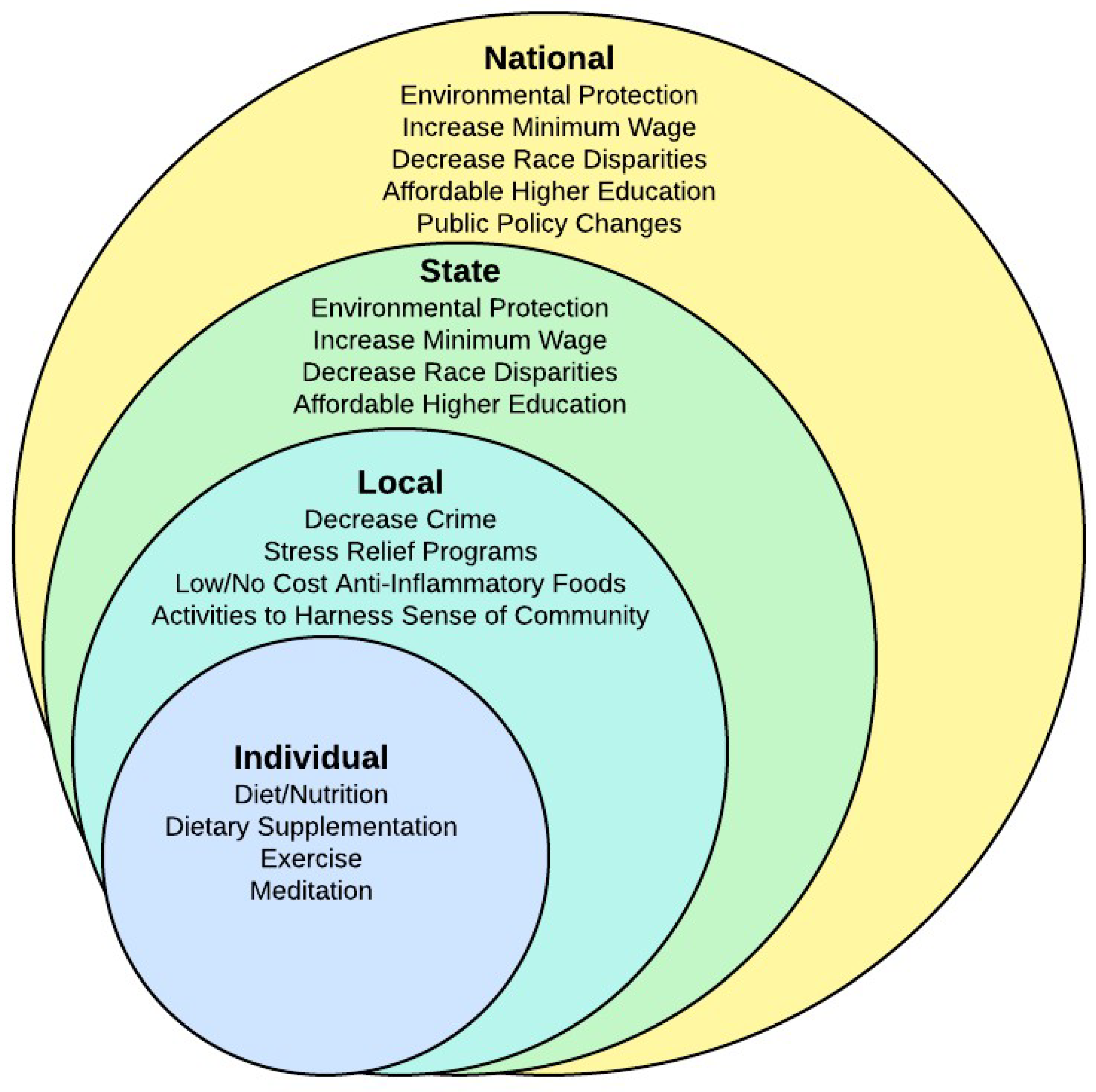

3.6. Nested Model of Interventions

Having low SES increases an individual’s risk for chronic disease. Appropriate interventions at multiple levels of society are critically needed to identify the most reliable actions for low SES persons to reduce potential disease burden. Since CVD has continued to be the leading cause of death for more than 80 years prior to COVID-19, and we have been focusing on individual interventions for most of that time, it is time to consider additional interventions on a larger scale. Both state and national policymakers have the responsibility to decrease disparities in health. Many studies have shown that education, income, discrimination, and pollution are related to health disparities [

63,

64,

65,

85,

86,

87,

88,

89,

90]. For example, policies can be changed to increase the minimum wage, decrease discrimination, provide environmental protection, and provide affordable higher education. At a local community level, interventions could include stress reduction programs, programs to disseminate knowledge, low/no-cost anti-inflammatory food sources, and activities to harness a sense of community. At all three of these levels of government, priority must be given to dealing with buildings that are toxic and to providing healthy affordable alternatives to current living arrangements. (See

Figure 2 for a visualization of the nested model.)

Moreover, interventions at the individual level remain critically important. Providing information on proper nutrition, dietary supplementation, exercise, meditation, and other anti-inflammatory treatments must continue. However, we will be unable to completely disrupt the link between low SES and chronic disease without knowledge, integration, and intervention at the other societal levels of risk. A multi-level approach to disease processes and prevention in future research is essential to meet these needs. Nurses are in a unique position to facilitate interventions at many if not all societal levels. Nurses can participate in research, education, and policy to enhance knowledge and dissemination. Also, nurses can use this information to better assist their patients in practice.

4. Discussion

As was illustrated in the previous paragraphs, the relationships between chronic disease, inflammation, and stress are close, just as the relationship between low SES and stress is. Additionally, with continued investigations the LAR is hoped to be proven a reliable tool of measurement in weighing one’s risk for chronic disease. Applying this metric to people of low SES may be useful in quantifying our understanding as to how much one’s risk for chronic disease increases because of the stresses implicated by low SES. Should this tool prove to be both valid and reliable, research and policy practices could be better informed as to how we handle chronic disease prevention and treatment in both the clinical setting as well as government run public health funding, policies, and initiatives.

Even as more attention is drawn to inflammation, gaps remain. First, there is a lack of prospective longitudinal data. Results from longitudinal studies could identify biomarkers and interventions effective in preventing chronic disease through the SES/inflammation pathway presented here. Second, the complexity and interaction of different biomarker pathways of chronic disease processes are unclear. Many chronic diseases have similar and interacting pathways. Future studies can evaluate interventions across multiple disease processes regarding the common pathway of inflammation. Third, there are two models, the cumulative and critical period models, frequently used in life-course literature; neither has been determined to be the best fit in all cases. Combining aspects of both models in creating a new more comprehensive model is needed. Fourth, although leptin resistance has been identified and interventions have been developed to address it, the process of leptin resistance is not fully understood. Without this piece of the puzzle, it will be difficult to determine exactly what level of leptin is considered a safe level for overall health and wellbeing. Fifth, a more robust validation of biomarkers, leptin, and adiponectin, is needed to understand their roles as risk factors for chronic disease. Including populations from prenatal to the extreme elderly is important in determining the life course of inflammation. Sixth, the role of biological processes in mediating SES links to health need full evaluation. Finally, there is a need for broad interventions at the societal level to reduce health disparities associated with SES. In fact, multi-level interventions may be the most effective way to decrease disparities between groups. The text continues here.

5. Conclusion

This paper has proposed a pathway that links low SES to inflammation and chronic disease, discussed interventions, and identified gaps in the research and potential interventions. Additional research on relationships between inflammation, multiple disease states, and SES is needed. Understanding how to intervene with low SES exposures to decrease inflammation and, therefore, disease risk is imperative to remove the health disparities in SES.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization J.R.; writing—original draft preparation, J.R., K.H.; writing—review and editing, J.R., K.H., L.M.; visualization, J.R., K.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DM |

Diabetes Mellitus |

| CA |

Cancer |

| CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| CRP |

C-Reactive Protein |

| CVD |

Cardiovascular Disease |

| CVLU |

Chronic Venous Leg Ulcer |

| HTN |

Hypertension |

| LAR |

Leptin-to-Adiponectin Ratio |

| NCCDPHHP |

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion |

| SES |

Socioeconomic Status |

References

- Jam, S.A.; Rezaeian, S.; Najafi, F.; Hamzeh, B.; Shakiba, E.; Moradinazar, M.; Darbandi, M.; Hichi, F.; Eghtesad, S.; Pasdar, Y. Association of a Pro-Inflammatory Diet with Type 2 Diabetes and Hypertension: Results from the Ravansar Non-Communicable Diseases Cohort Study. Arch Public Health 2022, 80, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, C.M.; Chen, L.-W.; Heude, B.; Bernard, J.Y.; Harvey, N.C.; Duijts, L.; Mensink-Bout, S.M.; Polanska, K.; Mancano, G.; Suderman, M.; et al. Dietary Inflammatory Index and Non-Communicable Disease Risk: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, P.H.; Chiang, J.J.; Chen, E.; Miller, G.E. Race, Socioeconomic Status, and Low-Grade Inflammatory Biomarkers across the Lifecourse: A Pooled Analysis of Seven Studies. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 123, 104917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, A.; Sullenbarger, B.; Prakash, R.; McDaniel, J.C. Supplementation with Eicosapentaenoic Acid and Docosahexaenoic Acid Reduces High Levels of Circulating Proinflammatory Cytokines in Aging Adults: A Randomized, Controlled Study. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids 2018, 132, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, H.S.; Hart, J.E.; James, P.; Elliott, E.G.; DeVille, N.V.; Holmes, M.D.; De Vivo, I.; Mucci, L.A.; Laden, F.; Rebbeck, T.R. Impact of Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status, Income Segregation, and Greenness on Blood Biomarkers of Inflammation. Environment International 2022, 162, 107164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Deng, H.; Cui, H.; Fang, J.; Zuo, Z.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, L. Inflammatory Responses and Inflammation-Associated Diseases in Organs. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 7204–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furman, D.; Campisi, J.; Verdin, E.; Carrera-Bastos, P.; Targ, S.; Franceschi, C.; Ferrucci, L.; Gilroy, D.W.; Fasano, A.; Miller, G.W.; et al. Chronic Inflammation in the Etiology of Disease across the Life Span. Nat Med 2019, 25, 1822–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frühbeck, G.; Catalán, V.; Rodríguez, A.; Gómez-Ambrosi, J. Adiponectin-Leptin Ratio: A Promising Index to Estimate Adipose Tissue Dysfunction. Relation with Obesity-Associated Cardiometabolic Risk. Adipocyte 2018, 7, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laubach, Z.M.; Holekamp, K.E.; Aris, I.M.; Slopen, N.; Perng, W. Applications of Conceptual Models from Lifecourse Epidemiology in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. Biol. Lett. 2022, 18, 20220194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajat, A.; MacLehose, R.F.; Rosofsky, A.; Walker, K.D.; Clougherty, J.E. Confounding by Socioeconomic Status in Epidemiological Studies of Air Pollution and Health: Challenges and Opportunities. Environ Health Perspect 2021, 129, 065001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs World Population Ageing 2019: Highlights. 2019.

- Centers for Disease Control National Population Projections 2014-2060 Results Form. Available online: https://wonder.cdc.gov/controller/datarequest/D117 (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- CDC About Us. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/about/index.html (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Leonardi, G.C.; Accardi, G.; Monastero, R.; Nicoletti, F.; Libra, M. Ageing: From Inflammation to Cancer. Immun Ageing 2018, 15, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, N.; Baby, D.; Rajguru, J.; Patil, P.; Thakkannavar, S.; Pujari, V. Inflammation and Cancer. Ann Afr Med 2019, 18, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, T.J.; Corr, E.M.; van Solingen, C.; Schlamp, F.; Brown, E.J.; Koelwyn, G.J.; Lee, A.H.; Shanley, L.C.; Spruill, T.M.; Bozal, F.; et al. Chronic Stress Primes Innate Immune Responses in Mice and Humans. Cell Rep 2021, 36, 109595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feehan, K.T.; Gilroy, D.W. Is Resolution the End of Inflammation? Trends Mol Med 2019, 25, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leuti, A.; Fazio, D.; Fava, M.; Piccoli, A.; Oddi, S.; Maccarrone, M. Bioactive Lipids, Inflammation and Chronic Diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2020, 159, 133–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drożdż, D.; Drożdż, M.; Wójcik, M. Endothelial Dysfunction as a Factor Leading to Arterial Hypertension. Pediatr Nephrol 2023, 38, 2973–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfaddagh, A.; Martin, S.S.; Leucker, T.M.; Michos, E.D.; Blaha, M.J.; Lowenstein, C.J.; Jones, S.R.; Toth, P.P. Inflammation and Cardiovascular Disease: From Mechanisms to Therapeutics. American Journal of Preventive Cardiology 2020, 4, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Gems, D. Gross Ways to Live Long: Parasitic Worms as an Anti-Inflammaging Therapy? eLife 2021, 10, e65180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islami, F.; Goding Sauer, A.; Miller, K.D.; Siegel, R.L.; Fedewa, S.A.; Jacobs, E.J.; McCullough, M.L.; Patel, A.V.; Ma, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; et al. Proportion and Number of Cancer Cases and Deaths Attributable to Potentially Modifiable Risk Factors in the United States. CA A Cancer J Clinicians 2018, 68, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohrab, S.S.; Raj, R.; Nagar, A.; Hawthorne, S.; Paiva-Santos, A.C.; Kamal, M.A.; El-Daly, M.M.; Azhar, E.I.; Sharma, A. Chronic Inflammation’s Transformation to Cancer: A Nanotherapeutic Paradigm. Molecules 2023, 28, 4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruk, L.; Mamtimin, M.; Braun, A.; Anders, H.-J.; Andrassy, J.; Gudermann, T.; Mammadova-Bach, E. Inflammatory Networks in Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancers 2023, 15, 2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunes-Santos, C.J.; Kuehn, H.; Boast, B.; Hwang, S.; Kuhns, D.B.; Stoddard, J.; Niemela, J.E.; Fink, D.L.; Pittaluga, S.; Abu-Asab, M.; et al. Inherited ARPC5 Mutations Cause an Actinopathy Impairing Cell Motility and Disrupting Cytokine Signaling. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 3708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rae, W.; Sowerby, J.M.; Verhoeven, D.; Youssef, M.; Kotagiri, P.; Savinykh, N.; Coomber, E.L.; Boneparth, A.; Chan, A.; Gong, C.; et al. Immunodeficiency, Autoimmunity, and Increased Risk of B Cell Malignancy in Humans with TRAF3 Mutations. Sci. Immunol. 2022, 7, eabn3800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roe, K. An Inflammation Classification System Using Cytokine Parameters. Scand J Immunol 2021, 93, e12970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacco, K.; Castagnoli, R.; Vakkilainen, S.; Liu, C.; Delmonte, O.M.; Oguz, C.; Kaplan, I.M.; Alehashemi, S.; Burbelo, P.D.; Bhuyan, F.; et al. Immunopathological Signatures in Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children and Pediatric COVID-19. Nat Med 2022, 28, 1050–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldum, H.; Fossmark, R. Inflammation and Digestive Cancer. IJMS 2023, 24, 13503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvete, O.; Reyes, J.; Benítez, J. Case Report: CMV Infection and Same Mechanism-Originated Intestinal Inflammation Compatible With Bowel/Crohn’s Disease Is Suggested in ATP4A Mutated-Driven Gastric Neuroendocrine Tumors. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 553110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, F.; Catelli, A.; Cifaldi, C.; Leonardi, L.; Mulè, R.; Fusconi, M.; Stefoni, V.; Chiriaco, M.; Rivalta, B.; Di Cesare, S.; et al. Case Report: Hodgkin Lymphoma and Refractory Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Unveil Activated Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase-δ Syndrome 2 in an Adult Patient. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 702546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, P.; Lu, L.; Cai, S.; Chen, J.; Lin, W.; Han, F. Alternative Splicing: A New Cause and Potential Therapeutic Target in Autoimmune Disease. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 713540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chavez-Dominguez, R.; Perez-Medina, M.; Aguilar-Cazares, D.; Galicia-Velasco, M.; Meneses-Flores, M.; Islas-Vazquez, L.; Camarena, A.; Lopez-Gonzalez, J.S. Old and New Players of Inflammation and Their Relationship With Cancer Development. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 722999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, H.; Hagerling, C.; Werb, Z. Roles of the Immune System in Cancer: From Tumor Initiation to Metastatic Progression. Genes Dev. 2018, 32, 1267–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hibino, S.; Kawazoe, T.; Kasahara, H.; Itoh, S.; Ishimoto, T.; Sakata-Yanagimoto, M.; Taniguchi, K. Inflammation-Induced Tumorigenesis and Metastasis. IJMS 2021, 22, 5421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khandia, R.; Munjal, A. Interplay between Inflammation and Cancer. In Advances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology; Elsevier, 2020; Vol. 119, pp. 199–245. ISBN 978-0-12-816844-8. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, G.; Qu, L.; Gong, X.; Pang, B.; Yan, W.; Wei, J. Effect of Social Factors and the Natural Environment on the Etiology and Pathogenesis of Diabetes Mellitus. International Journal of Endocrinology 2019, 2019, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancuso, P.; Bouchard, B. The Impact of Aging on Adipose Function and Adipokine Synthesis. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, S.H.; Habtewold, T.D.; Birhanu, M.M.; Sissay, T.A.; Tegegne, B.S.; Abuzerr, S.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Neighbourhood Socioeconomic Status and Overweight/Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Epidemiological Studies. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e028238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorena, K.; Jachimowicz-Duda, O.; Ślęzak, D.; Robakowska, M.; Mrugacz, M. Adipokines and Obesity. Potential Link to Metabolic Disorders and Chronic Complications. IJMS 2020, 21, 3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Pérez, A.; Sánchez-Jiménez, F.; Vilariño-García, T.; Sánchez-Margalet, V. Role of Leptin in Inflammation and Vice Versa. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 5887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frithioff-Bøjsøe, C.; Lund, M.A.V.; Lausten-Thomsen, U.; Hedley, P.L.; Pedersen, O.; Christiansen, M.; Baker, J.L.; Hansen, T.; Holm, J. Leptin, Adiponectin, and Their Ratio as Markers of Insulin Resistance and Cardiometabolic Risk in Childhood Obesity. Pediatr Diabetes 2020, 21, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mkumbuzi, L.; Mfengu, M.M.; Engwa, G.A.; Sewani-Rusike, C.R. Insulin Resistance Is Associated with Gut Permeability Without the Direct Influence of Obesity in Young Adults. DMSO 2020, Volume 13, 2997–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.-Y.; Chen, W.-L. Examining the Association Between Serum Leptin and Sarcopenic Obesity. JIR 2021, Volume 14, 3481–3487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, K.-W.; Ok, M.; Lee, S.-K. Leptin as a Key between Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease. Journal of Obesity & Metabolic Syndrome 2020, 29, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farkhondeh, T.; Llorens, S.; Pourbagher-Shahri, A.M.; Ashrafizadeh, M.; Talebi, M.; Shakibaei, M.; Samarghandian, S. An Overview of the Role of Adipokines in Cardiometabolic Diseases. Molecules 2020, 25, 5218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T. Adiponectin: Role in Physiology and Pathophysiology. Int J Prev Med 2020, 11, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.M.; Doss, H.M.; Kim, K.S. Multifaceted Physiological Roles of Adiponectin in Inflammation and Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amano, H.; Shirakawa, Y.; Hashimoto, H. Adiponectin Levels among Individuals with Varied Employment Status in Japan: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of the J-SHINE Study. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 10936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, D.; Khanna, S.; Khanna, P.; Kahar, P.; Patel, B.M. Obesity: A Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation and Its Markers. Cureus 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaha, D.; Vesa, C.; Uivarosan, D.; Bratu, O.; Fratila, O.; Tit, D.; Pantis, C.; Diaconu, C.; Bungau, S. Influence of Inflammation and Adipocyte Biochemical Markers on the Components of Metabolic Syndrome. Exp Ther Med 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Giudice, M.; Gangestad, S.W. Rethinking IL-6 and CRP: Why They Are More than Inflammatory Biomarkers, and Why It Matters. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2018, 70, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, S.; Murmu, N.; Bose, M.; Ghosh, S.; Giri, B. Obesity and Chronic Leptin Resistance Foster Insulin Resistance: An Analytical Overview. BLDE University Journal of Health Sciences 2021, 6, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamel, S.M.; Abdel Azeem, M.E.; Mohamed, R.A.; Kamel, M.M.; Abdel Aleem (Abdelaleem), E.A. High Serum Leptin and Adiponectin Levels as Biomarkers of Disease Progression in Egyptian Patients with Active Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2023, 37, 03946320231154988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukito, A.A.; Bakri, S.; Kabo, P.; Wijaya, A. The Mechanism of Coronary Artery Calcification in Centrally Obese Non-Diabetic Men: Study on The Interaction of Leptin, Free Leptin Index, Adiponectin, Hs-C Reactive Protein, Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 and Matrix Gla Protein. Molecular and Cellular Biomedical Sciences 2020, 4, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vales-Villamarín, C.; de Dios, O.; Pérez-Nadador, I.; Gavela-Pérez, T.; Soriano-Guillén, L.; Garcés, C. Leptin Concentrations Determine the Association between High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein Levels and Body Mass Index in Prepubertal Children. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galazka, J.K.; Polak, A.; Matyjaszek-Matuszek, B. Adiponectin as a Novel Predictive Biomarker of Multiple Sclerosis Course. Current Issues in Pharmacy and Medical Sciences 2023, 36, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M.R.; Fasano, R.; Paolisso, G. Adiponectin and Cognitive Decline. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Yuan, M.; Zhang, L.; Wu, B.; Sun, X. Adiponectin Alleviates NLRP3-Inflammasome-Mediated Pyroptosis of Aortic Endothelial Cells by Inhibiting FoxO4 in Arteriosclerosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2019, 514, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: UNITED STATES. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045218 (accessed on 18 April 2019).

- Kraft, P.; Kraft, B. Explaining Socioeconomic Disparities in Health Behaviours: A Review of Biopsychological Pathways Involving Stress and Inflammation. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2021, 127, 689–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuru-Jeter, A.M.; Michaels, E.K.; Thomas, M.D.; Reeves, A.N.; Thorpe, R.J.; LaVeist, T.A. Relative Roles of Race Versus Socioeconomic Position in Studies of Health Inequalities: A Matter of Interpretation. Annual Review of Public Health 2018, 39, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Axford, N.; Berry, V. Money Matters: Time for Prevention and Early Intervention to Address Family Economic Circumstances. J of Prevention 2023, 44, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, S.J.; Volling, B.L.; Grogan-Kaylor, A.C. Examining Mechanisms Linking Economic Insecurity to Interparental Conflict among Couples with Low Income. Family Relations 2023, 72, 1158–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryu, S.; Fan, L. The Relationship Between Financial Worries and Psychological Distress Among U.S. Adults. J Fam Econ Iss 2023, 44, 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, W.M.; Kelli, H.M.; Lisko, J.C.; Varghese, T.; Shen, J.; Sandesara, P.; Quyyumi, A.A.; Taylor, H.A.; Gulati, M.; Harold, J.G.; et al. Socioeconomic Status and Cardiovascular Outcomes: Challenges and Interventions. Circulation 2018, 137, 2166–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, K.; Russ, S.A.; Kahn, R.S.; Flores, G.; Goodman, E.; Cheng, T.L.; Halfon, N. Health Disparities: A Life Course Health Development Perspective and Future Research Directions. In Handbook of Life Course Health Development; Halfon, N., Forrest, C.B., Lerner, R.M., Faustman, E.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 499–520. ISBN 978-3-319-47141-9. [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg, M.H.; Chen, G.; Olsen, J.A.; Abelsen, B. Combining Education and Income into a Socioeconomic Position Score for Use in Studies of Health Inequalities. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, R.; Kröger, H.; Geyer, S. Social Causation Versus Health Selection in the Life Course: Does Their Relative Importance Differ by Dimension of SES? Soc Indic Res 2019, 141, 1341–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraga, S.; Severo, M.; Ramos, E.; Kelly-Irving, M.; Silva, S.; Ribeiro, A.I.; Petrovic, D.; Barros, H.; Stringhini, S. Childhood Socioeconomic Conditions Are Associated with Increased Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation over Adolescence: Findings from the EPITeen Cohort Study. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2020, 105, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, M.; Ponsonby, A.-L.; Collier, F.; Liu, R.; Sly, P.D.; Azzopardi, P.; Lycett, K.; Goldfeld, S.; Arnup, S.J.; Burgner, D.; et al. Exposure to Adversity and Inflammatory Outcomes in Mid and Late Childhood. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity - Health 2020, 9, 100146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghezzi, P.; Floridi, L.; Boraschi, D.; Cuadrado, A.; Manda, G.; Levic, S.; D’Acquisto, F.; Hamilton, A.; Athersuch, T.J.; Selley, L. Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Induced by Environmental and Psychological Stressors: A Biomarker Perspective. Antioxid Redox Signal 2018, 28, 852–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, P.H.; Garbutt, L.D. Stress, Inflammation and Cardiovascular Disease. J Psychosom Res 2002, 52, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Machiorlatti, M.; Krebs, N.M.; Muscat, J.E. Socioeconomic Differences in Nicotine Exposure and Dependence in Adult Daily Smokers. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calling, S.; Ohlsson, H.; Sundquist, J.; Sundquist, K.; Kendler, K.S. Socioeconomic Status and Alcohol Use Disorders across the Lifespan: A Co-Relative Control Study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptiste-Roberts, K.; Hossain, M. Socioeconomic Disparities and Self-Reported Substance Abuse-Related Problems. Addict Health 2018, 10, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Austin, M.K.; Chen, E.; Ross, K.M.; McEwen, L.M.; Maclsaac, J.L.; Kobor, M.S.; Miller, G.E. Early-Life Socioeconomic Disadvantage, Not Current, Predicts Accelerated Epigenetic Aging of Monocytes. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 97, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.E.; Pollak, S.D. Early Life Stress and Development: Potential Mechanisms for Adverse Outcomes. J Neurodevelop Disord 2020, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laubach, Z.M.; Perng, W.; Cardenas, A.; Rifas-Shiman, S.L.; Oken, E.; DeMeo, D.; Litonjua, A.A.; Duca, R.-C.; Godderis, L.; Baccarelli, A.; et al. Socioeconomic Status and DNA Methylation from Birth Through Mid-Childhood: A Prospective Study in Project Viva. Epigenomics 2019, 11, 1413–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgartner, J.; Brauer, M.; Ezzati, M. The Role of Cities in Reducing the Cardiovascular Impacts of Environmental Pollution in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. BMC Med 2020, 18, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutschow, B.; Gray, B.; Ragavan, M.I.; Sheffield, P.E.; Philipsborn, R.P.; Jee, S.H. The Intersection of Pediatrics, Climate Change, and Structural Racism: Ensuring Health Equity through Climate Justice. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 2021, 51, 101028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, J.; Cushing, L. Chemical Exposures, Health, and Environmental Justice in Communities Living on the Fenceline of Industry. Curr Envir Health Rpt 2020, 7, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, C.H.; Brugge, D. Environmental Justice: Disproportionate Impacts of Transportation on Vulnerable Communities. In Traffic-Related Air Pollution; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 495–510. [Google Scholar]

- Meehan, K.; Jurjevich, J.R.; Chun, N.M.J.W.; Sherrill, J. Geographies of Insecure Water Access and the Housing–Water Nexus in US Cities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117, 28700–28707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez, C.H. Structural Racism as an Environmental Justice Issue: A Multilevel Analysis of the State Racism Index and Environmental Health Risk from Air Toxics. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 2023, 10, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kakade, D.S.V.; Dabade, D.T.D.; Patil, D.V.C.; Ajani, D.S.N.; Bahulekar, A.; Sawant, R. Examining the Social Determinants of Health in Urban Communities: A Comparative Analysis. South Eastern European Journal of Public Health 2023, 111–125. [Google Scholar]

- LaVeist, T.A.; Pérez-Stable, E.J.; Richard, P.; Anderson, A.; Isaac, L.A.; Santiago, R.; Okoh, C.; Breen, N.; Farhat, T.; Assenov, A.; et al. The Economic Burden of Racial, Ethnic, and Educational Health Inequities in the US. JAMA 2023, 329, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mata, J.; Kadel, P.; Frank, R.; Schüz, B. Education- and Income-Related Differences in Processed Meat Consumption across Europe: The Role of Food-Related Attitudes. Appetite 2023, 182, 106417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minervini, G.; Franco, R.; Marrapodi, M.M.; Di Blasio, M.; Ronsivalle, V.; Cicciù, M. Children Oral Health and Parents Education Status: A Cross Sectional Study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, K.T.; Chiew, K.S. The Impact of Air Pollution on Neurocognitive Development: Adverse Effects and Health Disparities. Developmental Psychobiology 2023, 65, e22440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).