1. Introduction

There is perhaps no better place to begin a conversation of leaping and gliding in amphibians than the tropical dipterocarp forests of Southeast Asia, where gliding vertebrates are more prevalent than anywhere else on Earth (Heinicke et al., 2012). Alfred Russel Wallace, the biologist credited alongside Charles Darwin with the discovery of evolution by natural selection, spent eight years (1854-1862) collecting specimens from the Malay Archipelago in Southeast Asia. It was in 1855 on the island of Borneo, home to one of the oldest rainforests in the world, that Wallace first encountered a flying frog, which he later described in The Malay Archipelago (Wallace, 1869):

“One of the most curious and interesting [Amphibians] which I met with in Borneo was a large tree-frog, which was brought me by one of the Chinese workmen. He assured me that he had seen it come down in a slanting direction from a high tree, as if it flew. On examining it, I found the toes very long and fully webbed to their very extremity, so that when expanded they offered a surface much larger than the body……. This is, I believe, the first instance known of a ‘flying frog,’ and it is very interesting to Darwinians as showing that the variability of the toes which have been already modified for purposes of swimming and adhesive climbing, have been taken advantage of to enable an allied species to pass through the air like the flying lizard.”

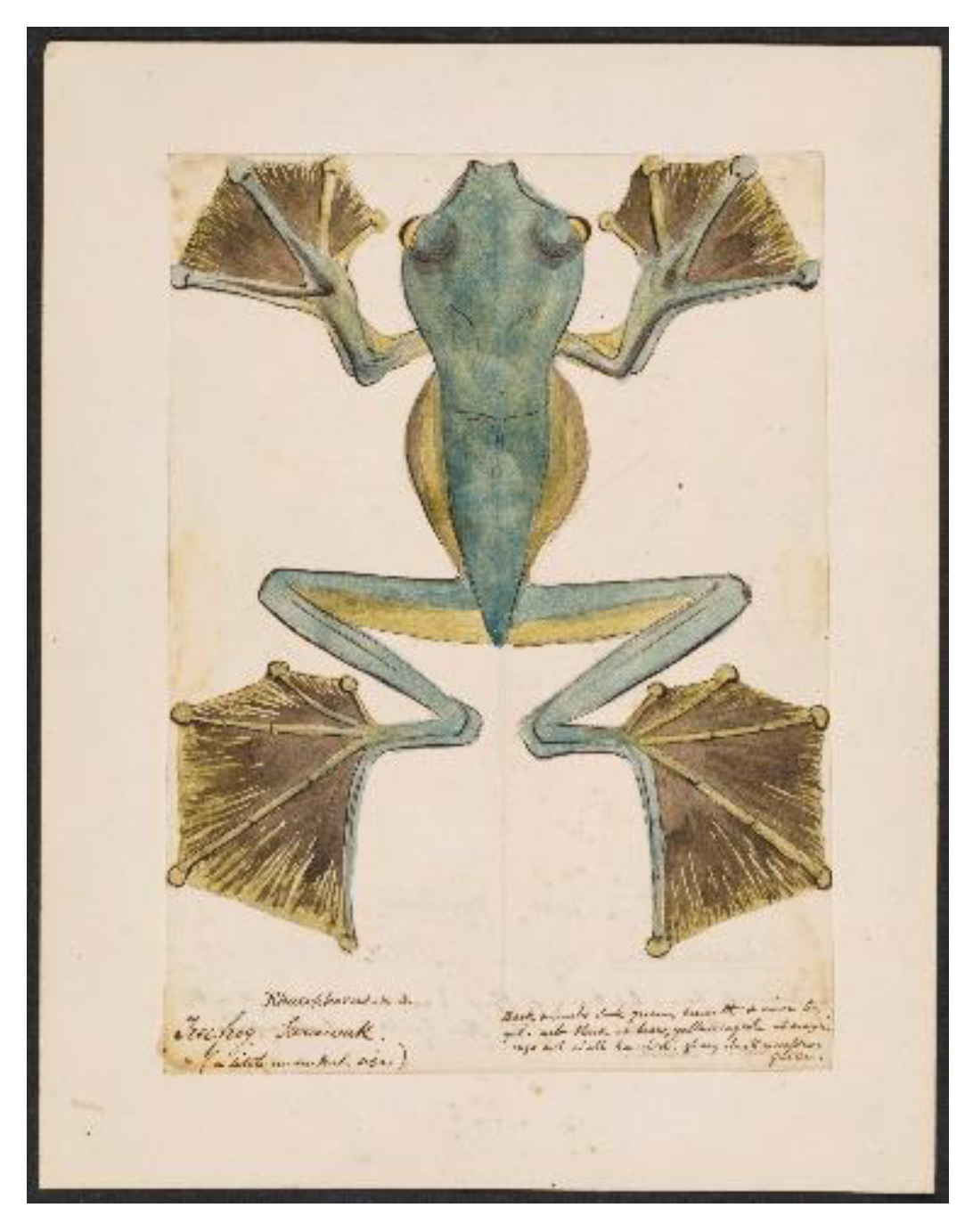

This account of Wallace’s flying frog, later named

Rhacophorus nigropalmatus (Boulenger, 1895), illustrates how captivating gliding by arboreal amphibians can be. It is important to note that we see evidence of human habitation on the island of Borneo dating as far back as 52,000 years (Aubert et al., 2018), so it is highly likely that the people indigenous to Borneo discovered

R. nigropalmatus long before Wallace or the Chinese workmen ever arrived. Nevertheless, Wallace’s watercolor painting (

Figure 1) marks the first known written report of gliding in an amphibian to western science. It was just the tip of the iceberg.

Since 1855, centuries of research on arboreal locomotion suggest that gliding flight has evolved independently several times among both Old World (Rhacophoridae) and New World (Hylidae) families of anurans (Inger, 1966; Emerson & Koehl, 1990; Duellman, 2001). Remarkably, anurans are not alone among arboreal amphibians that leap and glide. Gliding, defined as any controlled descent by an organism that converts gravitational potential energy into useful aerodynamic work effecting horizontal translation (Dudley et al., 2007; Dudley & Yanoviak, 2011), has evolved independently at least once in salamanders as well (Brown et al., 2022).

Wallace, seemingly informed by observations of gliding reptiles, correctly identified some morphological features underpinning gliding performance in amphibians. Modern biologists largely agree with Wallace’s assessment that long and webbed toes facilitate gliding flight in amphibians by virtue of higher proportional pedal surface area (Liem, 1970; Emerson & Koehl, 1990; Wu et al., 2022; Brown & Kirk, 2023), and there is evidence to support Wallace’s claim that webbed toes and large pedal surface area have been co-opted by amphibians for various forms of arboreal locomotion, like climbing and gliding (Manzano et al., 2008; Dang et al., 2018; O’Donnell & Deban, 2020; Brown & Kirk, 2023). In this chapter, we examine convergent functional morphology and aerial behaviors along a gradient of arboreality to better understand the biomechanics of leaping and gliding in amphibians, from primitive frogs to lungless salamanders.

2. Locomotion and Jumping in Basal Anurans

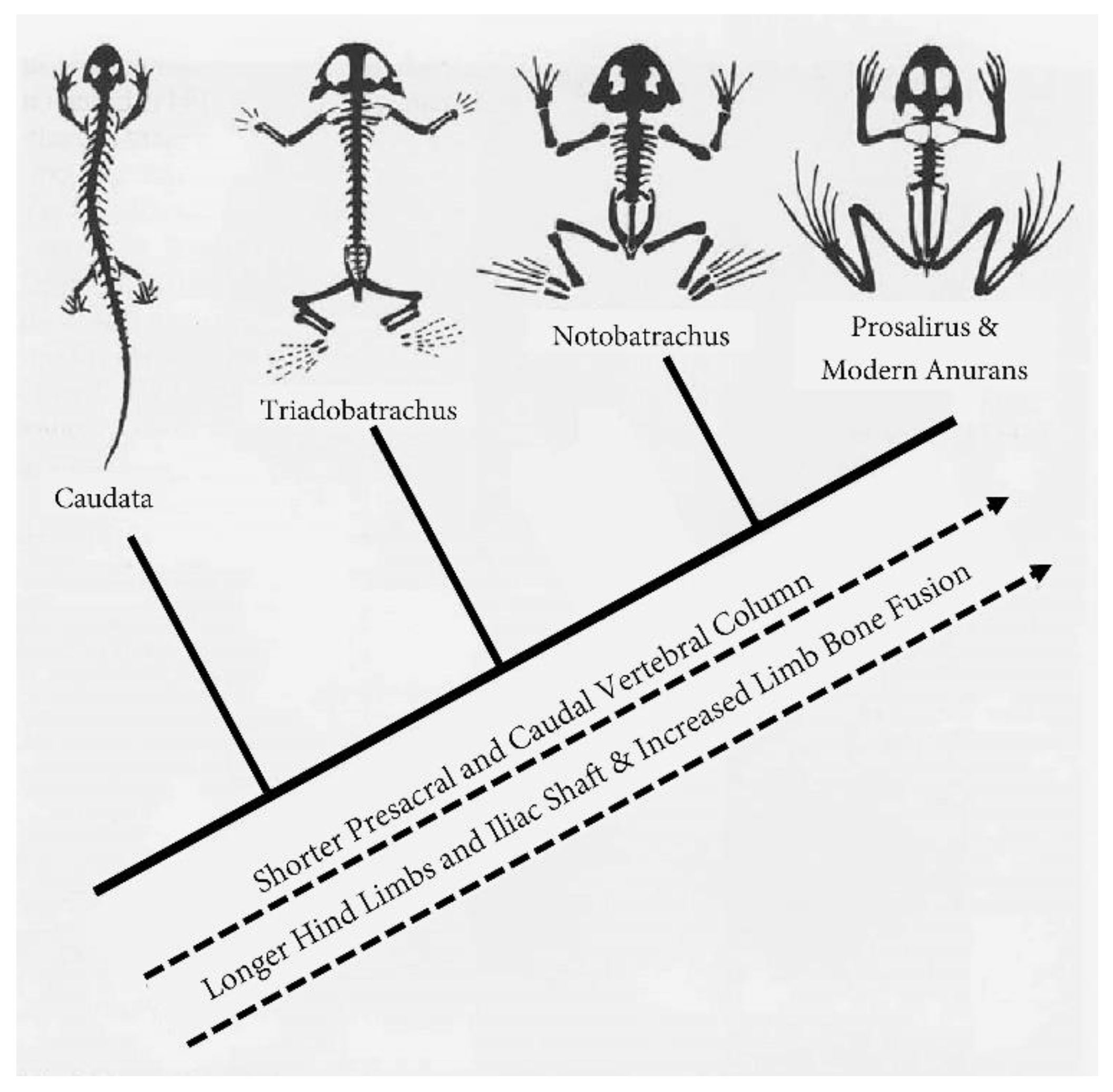

While it is tempting to jump ahead to the most impressive glide angles or flamboyant morphologies among arboreal amphibians, a thorough understanding of their leaping and gliding is best established from the ground up. During the Triassic period roughly 250 million years ago,

Triadobatrachus massinoti of the supercontinent Pangaea was one of the world’s earliest stem anurans (Piveteau, 1936). This 10cm-long, extinct amphibian represents an intermediate stage in the anuran

Bauplan (body plan), with adults reminiscent of yet distinct from modern anurans by virtue of a small tail and 15 (compared with 9 or fewer) presacral vertebrae (Ascarrunz et al., 2016; Stocker et al., 2019) (

Figure 2).

Triadobatrachus swam via alternating kicks of its hindlimbs, however, it likely could not jump and is instead thought to have relied primarily on salamander-like lateral undulatory locomotion (Shubin & Jenkins, 1995; Lires et al., 2016; Stocker et al., 2019). Although

T. massinoti lacked the condensed vertebral column and elongated hindlimbs associated with jumping, its pelvis and shortened tail represent a precursor to the anuran muscle linkage between the ilium and urostyle that enables saltatory locomotion (Shubin & Jenkins, 1995).

Jumping likely evolved in anurans sometime between the Early Triassic and Early Jurassic periods (250-190 Mya), possibly as a means of rapidly escaping into water (Gans & Parsons, 1966; Shubin & Jenkins, 1995; Essner et al., 2010). Prosalirus bitis, the next frog to appear in the fossil record, is hypothesized to represent the earliest Bauplan associated with jumping in anurans (Jenkins & Shubin, 1998; Reilly & Jorgensen, 2011). Several morphological features, such as elongation of the iliac shaft and hindlimbs, radio-ulnar and tibiofibular fusion, and elongate, unfused proximal tarsals, suggest that the skeleton of Prosalirus could absorb the force of jumping and landing (Stocker et al., 2019). While the exact number of presacral vertebrae remains unknown, none of the three existing (incomplete) specimens of Prosalirus have more than eight, and the angular appearance of the back reflects a pronounced flexure at the sacro-urostylic and ilio-sacral joints that would facilitate jumping (Jenkins & Shubin, 1998).

The extinction of taxa like

Triadobatrachus and

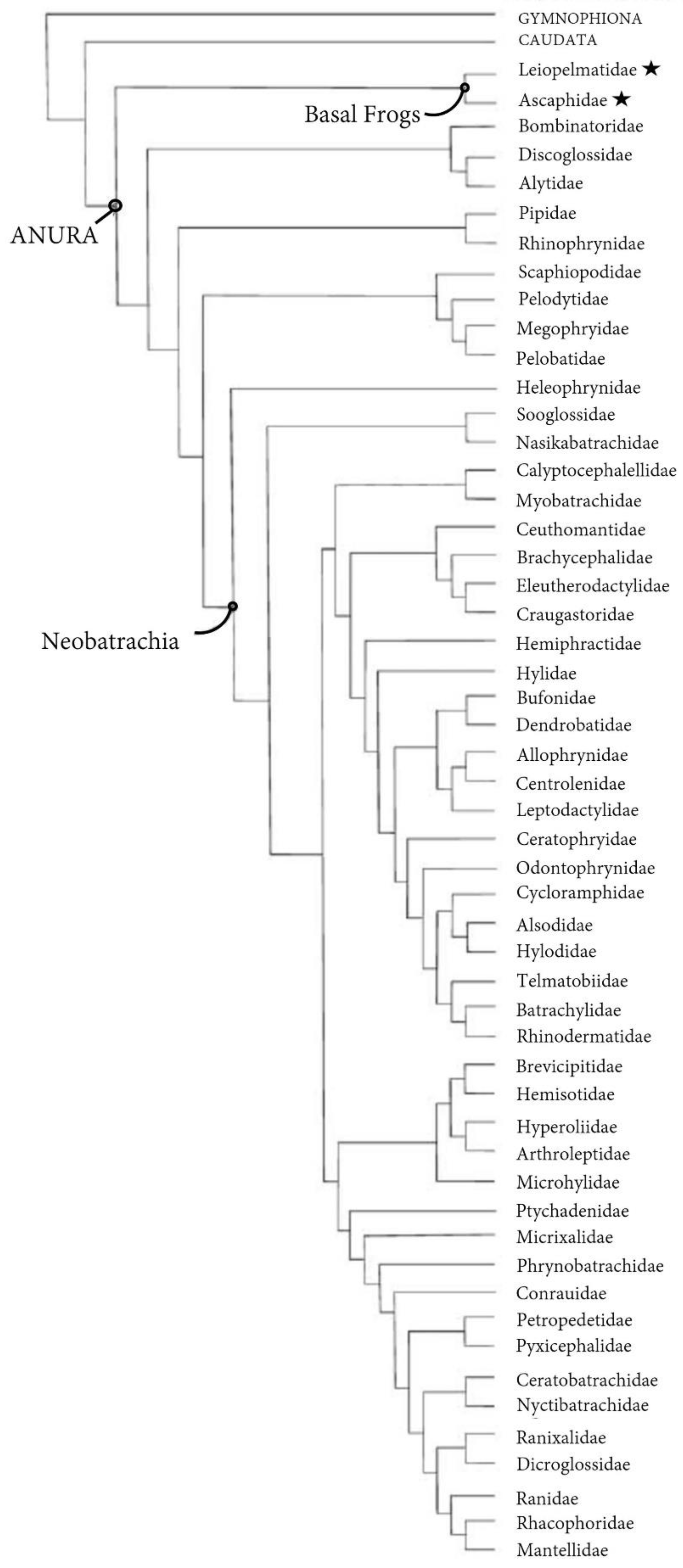

Prosalirus coupled with large gaps in the fossil record make it difficult, but not impossible, to study the biomechanics of jumping in stem anurans. Researchers have had success reconstructing stem anuran locomotion (Lires et al., 2016) and using living frogs of the basal suborder Archaeobatrachia, which includes a few extant species of tailed frogs (

Ascaphus) and New Zealand basal frogs (

Leiopelma), to study the acestral condition of locomotion in anurans (Essner et al., 2010; Reilly & Jorgensen, 2011; Reilly et al., 2015).

Ascaphus and

Leiopelma, henceforth collectively referred to as basal frogs (

Figure 3), locomote across land primarily by walking with a trotting gait and only rarely jump to escape predation or reposition themselves for foraging (Reilly et al., 2015). Reminiscent of

Prosalirus, basal frogs possess a

Bauplan associated with jumping: consolidated vertebral column, enhanced pelvis and pelvic musculature, loss of tail, and lengthened hindlimbs (Lutz and Rome, 1994). Studying how basal frogs jump and respond to short-term airborne flight provides a rare window into the functional foundations of leaping and gliding in more derived anurans.

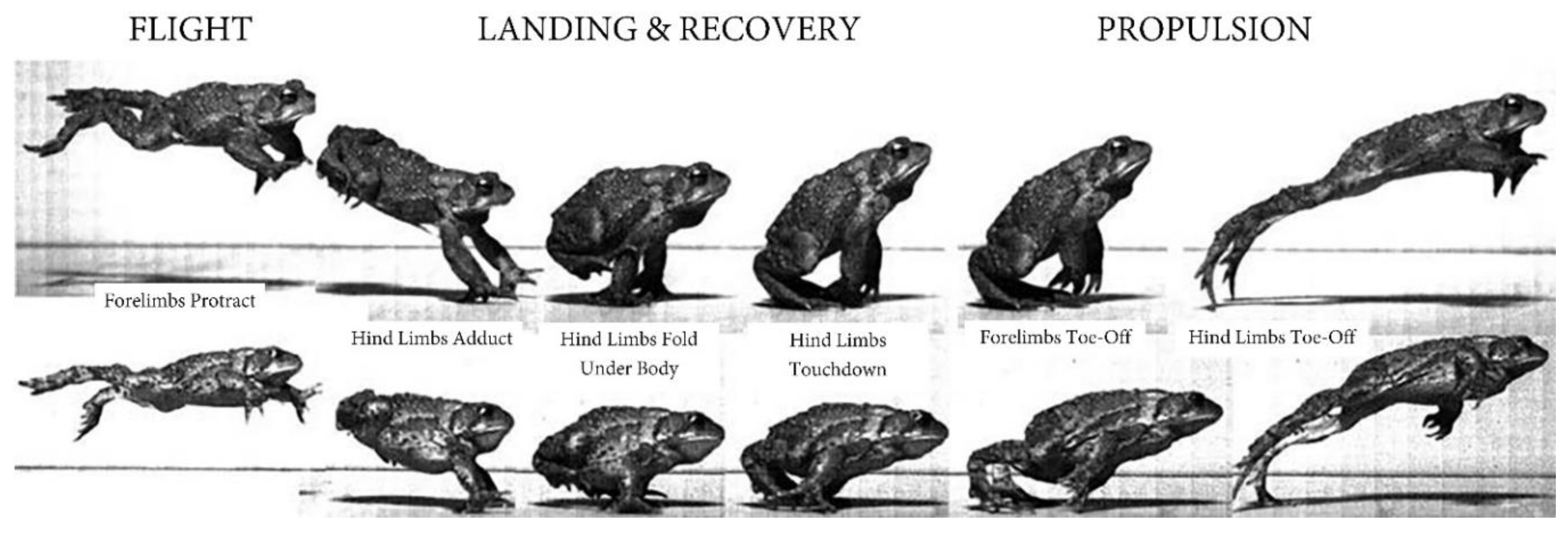

The frog jumping cycle can be divided into four stages: propulsion, flight, landing, and recovery (Nauwelaerts & Aerts, 2006; Essner et al., 2010; Li et al., 2021). Basal frogs propel themselves into the air using the same general biomechanics seen in all other living anurans, powered by a pair of rapidly and symmetrically extending hindlimbs that push against the substrate (Marsh & John-Alder, 1994; Peplowski & Marsh, 1997). The sacrum and presacral vertebral column extends at the sacro-urostylic and ilio-sacral joints via action of the longissimus dorsi muscles, aided by forelimb thrust. Meanwhile, the urostyle remains fixed between the ilia by the coccygeo-iliacus muscles, which transmit thrust for propulsion from the ilia to the urostyle and then to the sacrum and presacral vertebral column (Jenkins & Shubin, 1998). Thorough descriptions of hindlimb muscle (Roberts & Marsh, 2003; Azizi & Roberts, 2010; Azizi, 2014; Kuan et al., 2017) and tendon (Astley & Thomas, 2012; Astley & Roberts, 2014; Abdala et al., 2018; Mendoza & Azizi, 2021) forces during propulsion are plentiful, so this chapter will instead discuss the biomechanics of the rest of the jumping cycle, especially in arboreal anurans (

Section 3).

Similarities in jumping biomechanics and performance between basal frogs and more derived anurans end with propulsion (Reilly et al., 2015). Essner et al. (2010) investigated the complete jumping cycle of basal frogs and found that, unlike most extant frogs, they do not prepare for landing (Video 1). Basal frogs maintain posteriorly extended hindlimbs throughout flight and do not land on adducted forelimbs; in other words, they crash-land in a bellyflop style (Video 1). Landing forces, rather than being directed through the forelimbs, are distributed across the ventrum. As a result, recovery time after jumping is relatively long in basal anurans (Essner et al., 2010; Reilly et al., 2015). Uncontrolled landing and subsequent slow recovery could result in soft tissue damage and predation, respectively, when jumping around on land; the resulting selection pressures may explain the small body size, unusually large and shield-shaped pelvic cartilage, and abdominal ribs present in basal frogs (Essner et al., 2010).

Aside from basal frogs, only a handful of species from one clade of miniaturized frogs from Brazil, commonly referred to as pumpkin toadlets (Brachycephalus), maintain posteriorly extended hindlimbs and fail to adduct the forelimbs to prepare for landing (Video 2). Interestingly, these species also sport small body sizes that should minimize acute physiological damage resulting from uncontrolled landings. While they seem to be an exception to the rule among Neobatrachian frogs, miniaturization may interfere with controlled flight and landing in pumpkin toadlets, as their semicircular canals are the smallest of any adult vertebrate (Essner et al., 2022). Small semicircular canals correspond to low sensitivity to angular acceleration, perhaps explaining the pitiful flights of pumpkin toadlets.

Basal frogs primarily walk with a trotting gait with occasional, uncontrolled jumping included in the repertoire. But what do these clumsy frogs teach us about the impressive leaping and gliding seen in some arboreal amphibians, like Wallace’s flying frog? In amphibians, as in so many other taxa, the first step to flying was jumping.

3. Hopping and Aerial Control in Nonarboreal Anurans

If jumping was the first step towards flying in amphibians, the next was the ability to stay upright and stick the landing. Aside from the notable exceptions of basal frogs and pumpkin toadlets, which represent less than 5% of extant species (Roelants & Bossuyt, 2005), anurans generally control jumping through the landing stage. This shift from uncontrolled to controlled flight facilitated longer distance locomotion, better landing postures, faster recovery, and enhanced foraging and predator evasion that likely played a pivotal role in the adaptive radiation of Neobatrachian frogs (

Figure 3) into more terrestrial niches, including trees.

True frogs (Ranidae) comprise the largest and most widespread family of anurans and are characterized by saltatory (i.e., hopping) locomotion. They possess a generalized anuran Bauplan distinguished from basal frogs by a larger body size, longer and more powerful hindlimbs, more interdigital webbing, and elongated toe and tarsal bones that provide a broad platform for propulsion (Wells, 2007). Because they are larger and jump longer distances (Reilly et al., 2015), true frogs are presumably at even greater risk of injury if they experience uncontrolled landings. Consequently, they employ hindlimb rotations to right themselves in the air and to maintain an upright posture during post-propulsion flight (Nauwelaerts & Aerts, 2006; Wang et al., 2022). Furthermore, most frogs and toads protract their forelimbs anteriorly and laterally during flight to brace the trunk in landing, recover more quickly, and execute consecutive jumps (O’Reilly et al., 2000; Nauwelaerts & Aerts, 2006; Essner et al., 2010; Reilly et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2022).

Studying the morphology and biomechanics of jumping and airborne true frogs, although they are unable to glide, greatly informs our understanding of functional morphology and gliding flight in more specialized flying frogs. Wang et al. (2014; 2022) demonstrated that hindlimb rotations are the dominant mechanism regulating aerial pitch and roll in true frogs. Specifically, the hindlimbs remain extended after propulsion and engage in bilateral-parallel and asymmetric swings to correct for body rotations in the roll and pitch planes, respectively. In the latter third of the flight stage and just before landing, the hindlimbs fold under the body in preparation (Emerson & De Jongh, 1980; Peters et al., 1996; Wang et al., 2022). Importantly, this contraction of the hindlimbs late in flight shifts the frog’s center of mass forward and positions it just above the forelimbs, thus reducing the impact of landing (Azizi & Abbott, 2013; Azizi et al., 2014; Xiao et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022).

The forelimbs of jumping anurans function beyond inert shock absorbers, especially in toads (Bufonidae). After propulsion, the forelimbs protract to serve as a constant stiffness spring during the landing stage (O’Reilly et al., 2000; Xiao et al., 2021) (

Figure 4), perhaps coordinating with the hindlimbs to prepare for touchdown (Cox et al., 2018; Li et al., 2021). Toads exhibit highly coordinated landings, uniquely matching forelimb angle and muscle recruitment to jump height and distance and using the forelimbs to stabilize the body as the hindlimbs touch down (Gillis et al., 2014; Cox and Gillis, 2015; Ekstrom & Gillis, 2015). Impressively, such exquisite forelimb-forward landing control enables not just consecutive hopping but bounding locomotion in toads (Reilly et al., 2015). Bounding toads do not land on folded hindlimbs or stop between jumping cycles, rather they extend the hindlimbs prior to landing (

Figure 4) only on their feet, immediately propelling themselves back into the air. Bounding, famously used by mammals (Hoyt & Kenagy, 1988; Kenagy & Hoyt, 1989), is so effective that it can cut the energetic costs in half compared with walking (Walton & Anderson, 1988; Anderson et al., 1991), perhaps explaining the global expansion and rapid regional invasions of toads (Phillips et al., 2006).

Derived anurans have adapted an impressive suite of morphological characteristics and biomechanical strategies to help them jump and stick the landing from the ground, aiding in terrestrial locomotion. These same aerial righting and landing techniques are important in arboreal locomotion, wherein high degrees of limb coordination are sometimes required to right the body from more precarious starting positions (Wang et al., 2013) and land successfully on more complex substrates (Barnes et al., 2011; Bijma et al., 2016). To bridge the gap between terrestrial and arboreal locomotor demands, some frogs take the leap of faith and glide.

4. Leaping and Gliding in Treefrogs

Arriving at an appreciation for how anurans control the entire jumping cycle, from propulsion through recovery, begs the question: How do arboreal anurans bridge the gap from controlling short-term to long-term airborne flight? For the answer, we head back to the dipterocarp forests of Southeast Asia, the evolutionary cradle that gave rise to Wallace’s flying frog and a number of other gliding herpetofauna with conspicuous gliding morphologies.

4.1. Leaping and Gliding in Old-World Treefrogs (Rhacophoridae)

The rainforests of Southeast Asia are home to more gliding vertebrate species than any other place on Earth, and scientists have hypothesized about the habitat characteristics therein that favor the evolution of gliding vertebrates (Heinicke et al., 2012). Canopy-dwelling animals benefit from moving between different trees without climbing down to the forest floor, thereby wasting energy and exposing themselves to predators. The forests in this region sport relatively few lianas resulting in longer aerial distances between canopy trees, which may select for longer gliding distances (Emmons & Gentry, 1983), though this hypothesis was not well supported by subsequent studies (Appanah et al., 1993). We see more empirical evidence pointing to the dominance of dipterocarp trees in Southeast Asian rainforests (Dudley and DeVries, 1990; Heinicke et al., 2012), which are notably tall, have unpalatable leaves, and fruit in boom-bust cycles (Singh & Sharma, 2009; Corlett & Primack, 2011). Regardless of the precise evolutionary mechanism underpinning prolific gliding in Southeast Asia, its rainforests provide excellent examples of gliding arboreal amphibians.

Wallace’s flying frog is just one of many specialized gliding frog species from Southeast Asia now described and placed in Rhacophoridae. A number of studies have compared the gliding of specialized (Rhachophorus) and nonspecialized (Polypedates) rhacophorid treefrogs (Emerson, 1990; Emerson & Koehl, 1990; McKnight et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2022), both of which can glide under the modern definition (sensu Dudley et al., 2007). For jumping, some gliding treefrogs have what is known as a Type I ilio-sacral joint complex allowing considerable movement of the ilia in the horizontal plane, thus facilitating forward thrust, but restricting pelvic sliding in the vertical plane, which prevents rotation and likely contributes to aerial control (Griffiths, 1963; Emerson, 1982). McKnight et al. (2020) found that jumping performance positively correlates with body size and does not differ significantly between specialized and nonspecialized rhacophorids.

Once airborne, both specialized and nonspecialized rhacophorids assume a stereotypical parachute posture wherein they bend and shift their front and hindlimbs to position them lateral to their bodies, spread their fingers and toes, and constantly adjust limb position to stay upright during flight (Emerson & Koehl, 1990). While specialized rhacophorids always assume the stereotypical parachute posture, nonspecialized species occasionally leave the legs partially extended behind the body. Both can slow their vertical descent using the parachute posture, but specialized rhacophorids take longer (~2.9 s) to descend than nonspecialized individuals (~1.9 s) of the same mass thus reducing the risk of injury due to impact. Furthermore, both specialized and nonspecialized rhacophorids can alter their direction of descent (i.e., glide) and bank turns of up to 180° from the parachute posture by adjusting the orientation of the limbs and feet (Emerson & Koehl, 1990). Rotations and asymmetric postures of the limbs and feet influence the pressure drag around the airborne frogs (McCay, 2001), which they actively manipulate in a controlled manner to effect horizontal translation. Pressure drag (see Section 3.3.4) is the force resulting from the difference in pressure between the upstream and downstream faces of an object (e.g., the ventrum and dorsum of a falling treefrog), and it helps push the object downstream (Denny, 1993).

Upside or head-down treefrogs perform aerial righting via a rapid series of hindlimb movements wherein they 1) extend the hindlimbs laterally and posteriorly, 2) swing the hindlimbs about the body axis leading to a counter-rotation of the body, and 3) retract the hindlimbs. This entire maneuver takes ~42 ms and generates sufficient local angular momentum for a frog to rotate its body and keep momentum conserved (Wang et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2022). An upright body position maximizes body surface area perpendicular to airflow (i.e., frontal area) and generates aerodynamic drag, and holding the large, flat feet perpendicular to airflow effectively generates drag in the direction of airflow and lift perpendicular to it (Hoerner, 1985; Anderson, 1998).

Once upright, airborne treefrogs extend their limbs next to the body and, benefited by interdigital webbing (Wu et al., 2022), harness the resulting lift and drag to constantly maneuver, stay upright, and glide during flight (Emerson & Koehl, 1990; McCay, 2001). Specialized rhacophorids can achieve a shallower glide angle (25°–33°), always referred to relative to horizontal in this chapter, and travel longer horizontal distances (18.0–29.3 m) than nonspecialized species (60°, 13.7 m) (Emerson & Koehl, 1990) (

Table 1). While one study found that gliding performance does not differ between specialized and nonspecialized rhacophorids when falling from short heights (McKnight et al., 2020), it likely only captured the initial ballistic dive wherein gliding frogs fall downwards before breaking into more horizontal trajectories (Abdulali and Sekar, 1988; Emerson & Koehl, 1990). Aerodynamic forces are tied to velocity, and during the ballistic dive gliders are still accelerating to speeds where aerodynamic forces become relevant.

Figure 5.

An airborne Harlequin treefrog, Rhacophorus pardalis, in the stereotypical parachute posture gliding towards a tree in the Danum Valley Conservation Area on the island of Borneo. Photo by Tim Laman©.

Figure 5.

An airborne Harlequin treefrog, Rhacophorus pardalis, in the stereotypical parachute posture gliding towards a tree in the Danum Valley Conservation Area on the island of Borneo. Photo by Tim Laman©.

Arboreal and semiarboreal amphibians are relatively unstudied (Kays & Allison, 2001; Dudley et al., 2007). Arboreal toads from Southeast Asia (Rentapia and Sigalegalephrynus) have been described, but we found no empirical descriptions of how they jump, fly, or land. Given that they are endemic to an environment seemingly favorable to gliding evolution, it may prove interesting to examine the biomechanics of the entire jumping cycle in these arboreal toads. We posit that Rentapia is more likely to glide because it has full webbing between all but the fourth toe (Chan et al., 2016), whereas the toes of Sigalegalephrynus are less than half webbed (Smart et al., 2017; Sarker et al., 2019). But as in Rhacophoridae, gliding ability and performance would depend just as much on the orientation, posture, and movement of these features during flight. Likewise, several Rhacophorus species with more subtle morphological specializations (e.g., Rhacophorus harrissoni, R. dulitensis, R. georgii, R. prominanus, R. maximus, R. feae, and R. rufipes) may also be capable of parachuting or gliding at steep angles, but have not been studied. Outside of Rhacophoridae, a couple of Old World frogs recently had aerial performance described; both Hyperolius castaneus and Hyperolius discodactylus (Hyperoliidae) from Rwanda and the eastern Congo are capable of aerial righting and gliding at steep angles (Dehling, 2012; Dehling & Sinsch, 2023).

4.2. Leaping and Gliding in New World Treefrogs (Hylidae)

Gliding was first reported in arboreal anurans of the New World (Hylidae) roughly 100 years ago, a few decades after Wallace published The Malay Archipelago. Possibly the first hylid reported to glide was Trachycephalus typhonius from Brazil; Cott (1926) reported that, unlike terrestrial and arboreal control species, T. typhonius assumed a parachute posture when launched into the air, and did so without fail. Multiple drops from high perches revealed similar glide angles of ~57° (Cott, 1926). A century later, we know that gliding behavior is widespread within Hylidae and often associated with synchronized descent to explosive breeding sites (Roberts, 1994; Wells, 2007).

Glide performance depends heavily on takeoff, so it is worth briefly examining how hylids, which are ecomorphologically diverse, approach propulsion in complex arboreal environments. Biomechanically, hylids propel themselves like all other frogs (

Section 2); however, they vary in performance, jumping anywhere from 0.5–1.0 m horizontally at takeoff velocities of 1.9-2.9 m/s (Marsh & John-Alder, 1994) slightly below those of terrestrial jumping frogs (Wilson et al., 2000; Roberts & Marsh, 2003). Arboreal hylids commonly propel themselves into the air off compliant perches (e.g., thin branches or lianas) that absorb mechanical energy that would otherwise contribute to takeoff velocity. Despite this, some hylids are able to regain part of the energy lost to the perch during the recoil to maintain their takeoff velocity (Astley et al., 2015). Early investigations of jump distance by frogs from different habitats suggested that the highest performance was observed in arboreal hylids (Zug, 1978). However, follow-up analyses of Zug’s jumping data (1978) using more refined habitat categories clarified that among arboreal hylids, the grass-reed species are the strongest jumpers, and those species found high in the canopy the weakest ones (Gomes et al., 2009). Several separate studies have shown that interspecific variation in jumping performance is intrinsically associated with body form and size (Zug, 1972; Emerson, 1978; Emerson et al., 1990; Marsh & John-Alder, 1994), the influence of which on gliding is discussed in Section 3.3.6.

Takeoff velocity in hylids is lower when jumping from perches than flat ground (Astley et al., 2015) suggesting that high canopy hylids might behaviorally modify jumping performance (e.g., reduce takeoff velocity) to better suit their complex arboreal environments. In humans, propulsion typically produces rotation even when disadvantageous to performance, so athletes correct for this by controlling rotational motion during flight (Yeadon, 2000; Ortega-Jimenez et al., 2023). It is entirely possible that lower takeoff velocities in canopy hylids minimizes disadvantageous body rotations, as hypothesized in other jumping arboreal amphibians (Brown & Deban, 2020).

One arboreal hylid, the Cuban treefrog (Osteopilus septentrionalis), stands apart in jumping performance (Peplowski & Marsh, 1997; Mendoza & Azizi, 2021; Holt & Mayfield, 2023). Cuban treefrogs do not exhibit hindlimb muscle fiber length factors low enough to be considered specialized for elastic strain energy storage (Ker et al., 1988), but the plantaris muscle-tendon unit of Cuban treefrogs is stiffer, produces higher mass-specific energy and mass-specific forces, and has higher pennation angles that suggest muscle architecture is adapted to increase force capacity by packing more muscle fibers (Mendoza & Azizi, 2021).

Once airborne, a number of hylids can engage in gliding flight. Perhaps the most aerially adept is Agalychnis spurrelli, the gliding leaf frog of Central America. We see a Type I ilio-sacral joint complex in A. spurrelli that presumably limits rotation of the body while leaping from branches, after which these frogs assume the parachute posture, spreading out large, extensively webbed hands and fully webbed feet held parallel to the substrate (Savage, 2002). From this posture, A. spurrelli can glide horizontally for considerable distances at glide angles as shallow as 45° (Savage, 2002). These frogs are highly maneuverable and can execute banking turns during short vertical descent (~2 m) (Duellman, 2001). Like many gliding rhacophorids, A. spurrelli has fully webbed feet and nearly fully webbed hands that contribute to gliding performance (Wu et al., 2022). Furthermore, A. spurrelli has noticeable dermal folds at the elbow and along the ventrolateral edge of the forearm down to the base of the fingers (Duellman, 2001), and a thin longitudinal fold runs along the ventrolateral and ventromedian surfaces of each hindlimb, with a thin dermal fold extending across each heel and along the outer edge of each tarsus to the base of the toes (Duellman, 2001).

Gliding ability and performance, as in Rhacophoridae, seems to be highly variable in Hylidae. Even within genus Agalychnis we see species that are specialized (e.g., A. spurrelli), nonspecialized (e.g., Agalychnis saltator), and intermediate (Roberts, 1994; McCay, 2001b; Faivovich et al., 2010). Specialized Agalychnis are larger in body size and have larger, more completely webbed feet. All species of Agalychnis assume the parachute posture and exhibit similar behaviors when airborne, suggesting that aerial posturing was present in basal Agalychnis before the morphological specializations for gliding flight arose (McCay, 2001b). Modern cladistics have broken Agalychnis into two genera (Agalychnis and Cruziohyla) and indicate that gliding arose independently in each (Faivovich et al., 2010). Cruziohyla craspedopus, a species with extensive cutaneous flaps and fringes on the outer edges of the fore- and hindlimbs, is a morphologically likely candidate for gliding behavior, as are other slender-bodied hylids such as Hypsiboas boans, H. rosenbergi, H. wavrini, and Osteopilus vastus (Dudley et al., 2007). Outside of Hylidae, one New World frog in the family Leptodactylidae (Eleutherodactylus coqui) has been documented to parachute (Stewart 1985), but with little or no horizontal transit (Dudley et al., 2007).

A morphologically interesting group of hylids known collectively as the fringe-limbed frogs (Ecnomiohyla) are characterized by scalloped dermal fringes on the outer margin of the forelimb and foot and large toe pads (Faivovich et al., 2005). When threatened, these treefrogs leap from their perch and glide out of trees with outstretched limbs (Mendelson et al., 2008). Ecnomiohyla rabborum was reported to glide when leaping from heights of 9 m (Mendelson et al., 2008), but without a corresponding glide distance included we cannot calculate a glide angle. Sadly, the glide angle of E. rabborum may never be known as it recently went extinct (Platt, 2016), a chilling reminder of the global status of amphibians (Blaustein, 1990; Pounds et al., 2006; Scheele, 2019).

4.3. Functional Morphology of Gliding Treefrogs

I have mentioned a number of morphological adaptations that contribute to aerodynamic properties important for gliding performance. Now, let’s address the functional connections between morphology, much of it apparently co-opted, and biomechanics of gliding in treefrogs.

4.3.1. Elongated Hindlimbs

Morphological adaptations of gliding treefrogs, most notably elongated limbs (Wang et al., 2013; Citadini et al., 2018), lateral skin flaps (Emerson & Koehl, 1990) and enlarged feet with fully webbed toes (McKnight et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2022), are known to: (1) increase horizontal distance travelled, (2) reduce the minimum speed required to glide, (3) increase drag, which increases time aloft, and (4) improve maneuverability (Emerson et al., 1990). Elongated hindlimbs also facilitate rapid aerial righting, a necessary precursor to gliding if falling upside-down. Ultimately, the long hindlimbs that provide power for propulsion in all anurans are even longer and co-opted for initiating and maintaining upright body positions in gliding treefrogs (McCay, 2001; Wang et al., 2013).

4.3.2. Enlarged Toe Pads

Descending treefrogs are reported to land on the abdomen (Emerson & Koehl, 1990) unless landing on narrow branches, attaching via the toe pads (Barnes et al., 2011; Bijma et al., 2016). Rhacophorus have enlarged toe pads that confer greater shear forces during impact, helping them stick the landing on vertical trunks or leaves (McKnight et al., 2020). Exceptionally high friction along the proximal-distal pad axis seems most important for landing (Bijma et al., 2016). Large blood sinuses positioned just below the ventral surface of each toe (Krogh et al., 1922; Langowski et al., 2018) further improve the functional performance of the toe pads for landing (Barnes et al., 2011). Such soft, inelastic material beneath the pad reduces the risk of elastic recoil, increases contact time for adhesion, and increases contact area thereby increasing the probability of sticking the landing. The soft toe pad also molds itself to the contours of the landing surface and, because blood pressure is under physiological control, there exists a possibility that treefrogs somehow adjust the stiffness of the toe pads to fine-tune their landings (Barnes et al., 2011).

4.3.3. Interdigital Webbing

The longer toes and tarsal bones that provide broader surfaces for propulsion in frogs (Wells, 2007) are co-opted for gliding in treefrogs, paired with exaggerated interdigital webbing (Wu et al., 2022) and a parachute posturing to further increase frontal area and aerodynamic forces (Emerson & Koehl, 1990; Duellman, 2001; McCay, 2001). Enlarged feet lower minimum glide speeds, improve turning performance, and have more influence over drag, and thus aerial performance, than any other morphological feature (Emerson & Koehl, 1990). Gliding treefrogs maximize frontal area even further by behaviorally expanding their enlarged feet via phalangeal extension (Wallace, 1869; Emerson et al., 1990; Langowski et al., 2018). Increasing frontal area functions to 1) improve the lift:drag ratio and horizontal traveling distance, 2) lower the minimum speed required to glide, 3) increase the drag in freefall and thus decrease impact forces and maximize the time aloft, and 4) reduce the turning radius (Emerson & Koehl, 1990). In fact, other gliding herpetofauna, such as flying lizards (Draco) and snakes (Chrysopelea), deploy patagia or otherwise actively increase frontal area to glide more effectively after jumping or dropping from trees (Socha et al., 2005; McGuire & Dudley, 2011). Although pedal webbing may represent a functional expansion of the toes, already specialized for swimming as Wallace pointed out, it is increased manus webbing and the associated benefits to gripping, climbing, and gliding that gives Rhacophorus the edge in arboreal locomotion (Wu et al., 2022).

4.3.4. Foot Orientation

Orientation of the feet is especially important for treefrogs during flight. In parachuters and nonspecialized gliders (i.e., glide angle < 45°), pressure drag is the force responsible for the majority of weight support (Rayner, 1981; Vogel, 1996). The feet of gliding treefrogs very much resemble flat plates and, by the laws of fluid dynamics, produce much higher pressure drag when oriented perpendicular to flow. Pressure drag is roughly proportional to frontal area (Vogel, 1996), thus rotating the feet while falling such that the ventral sides are oriented downward increases frontal area, pressure drag, and by extension gliding performance. Additionally, holding the enlarged feet bent next to the center of mass improves the maneuverability of the frogs (Emerson & Koehl, 1990; McCay, 2001). The webbed feet of gliding treefrogs clearly affect a large pressure drag, as seen in the wings of insects, bats, and birds (Denny, 1993), but only if properly oriented.

4.3.5. Lateral Skin Flaps and Body Flatness

Feet are not the only flattened features of gliding frogs. Nearly all species of parachuting or gliding hylid frog are relatively slender with dorsoventrally flattened bodies (Dudley et al., 2007). Some specialized gliding treefrogs (e.g.,

R. nigropalmatus and

A. spurrelli) sport accessory skin flaps on the lateral margins of the limbs (Inger, 1966; Emerson & Koehl, 1990; Duellman, 2001). To understand how lateral skin flaps contribute to gliding performance, it helps to first reduce lift and drag forces to dimensionless coefficients (C

L and C

D, respectively) defined as:

where L is lift force, D is drag force, ρ is fluid (i.e., air) density, S is frontal area for parachuting animals, and V is air velocity. The C

L and C

D can then be expressed as a ratio (C

L:C

D) that is negatively associated with glide angle (i.e., positively associated with glide performance) (Vogel, 1996). Lateral skin flaps function to create a flatter edge during flight. Flat-fronted objects (e.g., falling treefrogs) with rounded edges are more streamlined and disturb the surrounding airflow less, whereas flat-fronted objects with flatter edges are bluffer and generate more drag and larger pressure gradients across the face of the object (Vogel, 1996). Larger pressure gradients across bluff bodies result in higher lift coefficients and, by extension, higher lift:drag ratios. In other words, lateral skin flaps exploit fluid dynamics to generate more pressure drag and higher lift:drag ratios, likely contributing to time aloft and aerial control in specialized treefrogs.

4.3.6. Body Size and Reynolds Number

Body size has substantial implications for gliding performance. Reynolds numbers (

Re) are higher for larger animals moving through fluid compared with smaller animals moving through the same fluid at the same speed (Rapp, 2017), but are dimensionless and only useful for qualitative comparisons (DeMont & Hokkanen, 1992). Gliding treefrogs typically have a

Re between 5,000 and 35,000 (Emerson et al., 1990), roughly between that of a flying insect (100-1,000) and a flying bird (1,000-1,000,000) (Dong et al., 2018). Ultimately, the higher

Re represents the importance of inertia, dominant in treefrogs and at

Re > 1,000, relative to viscosity, which is dominant in microbes and at very small

Re, for a particular fluid flow situation.

Re is given by:

where U is velocity (of the air relative to a falling treefrog), L is a linear dimension (e.g., snout-vent length of a treefrog), and v is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid (1.5 × 10

−5 m

2/s for air at 20°C) (e.g., Vogel, 1981). Bigger species (i.e., higher L) have a higher

Re (Rapp, 2017), so it is reasonable to assume that differences in treefrog body size largely account for any interspecific differences in

Re.

In Rhacophorus, Re (i.e., body size) interacts with morphology to regulate the effects of different morphological configurations on gliding performance (Emerson et al., 1990). Furthermore, while morphology explains most of the variation in glide speed, horizontal distance, and maneuverability, it is largely Re that accounts for differences in drag while parachuting. As a result, some species in genus Rhacophorus (e.g., Rhacophorus smaragdinus) have fully webbed feet but cannot glide due to their large body size (Wu et al., 2022). Although the large body sizes of some of the most impressive gliders (e.g., R. nigropalmatus) likely reduce time aloft and horizontal gliding distance, maneuverability might be a more important performance metric for airborne treefrogs trying to dodge obstacles or land on the nearest branch (Emerson & Koehl, 1990).

5. Jumping and Gliding in Arboreal Salamanders

5.1. Jumping in Lungless Salamanders

Salamanders, like anurans, stem from an ancient lineage of amphibians that could walk and breathe on land but were largely bound to permanent bodies of water (Duellman and Trueb 1994; Fröbisch et al., 2010; Fortuny, 2011; Schoch, 2014). However, unlike anurans, there is no morphological evidence to suggest extinct stem salamanders could jump, nor is jumping thought to be as critical a component in the adaptive radiation of salamanders into terrestrial niches. Rather, jumping is employed primarily in response to predator cues, described in just a handful of species from a single family of lungless salamanders (Ryerson, 2013; Ryerson et al., 2016; Hessel & Nishikawa, 2017; Brown & Deban, 2020) and anecdotally observed in a captive Dicamptodon tenebrosus (see Morris, 2015), a species known to lunge for its prey in the wild (Bury, 1972; Brodie Jr., 1978; Parker, 1993).

Lungless salamanders (Plethodontidae) diverged from other living salamanders over 100 Mya (Shen et al., 2016) and have since experienced multiple adaptive radiations, invading almost every terrestrial niche imaginable, including treetops (Wake, 1987; Rovito et al., 2013; Blankers et al., 2012). While the initial radiation of this family could be attributed to other factors, such as the evolution of specialized ballistic feeding mechanisms (Deban et al., 1997), the loss of lungs was nonetheless important and may have even lifted evolutionary constraints on the hyoid apparatus, enabling ballistic feeding (Wake, 1982; Roth & Wake, 1985; Deban, 2003). Whatever the driving force behind these radiations, they left in their wake over 500 described species of extant plethodontids comprising the largest, widest ranging, and most diverse family of salamanders and more than two-thirds of extant salamander diversity (AmphibiaWeb). Adult plethodontids, unless paedomorphic (e.g., Eurycea sosorum), breathe entirely through moist skin and mouth tissues, and most species retain direct development from their common plethodontid ancestor (Bonet & Blair, 2017); consequently, most plethodontids can complete their entire life cycle without any permanent body of water, allowing some to occupy trees permanently (Spickler et al., 2006). Even those plethodontids that may have re-evolved free-living aquatic larvae (e.g., Desmognathus) spend much of their adult lives in terrestrial microhabitats where jumping might prove advantageous. Given that all arboreal salamanders and, as far as we know, most jumping salamanders are lungless, we will focus entirely on plethodontids.

Jumping plethodontids are especially interesting because the family exhibits a high rate of direct development, meaning most plethodontids retain a generalized tetrapod Bauplan throughout their entire life cycle (Blankers et al., 2012). Thus, studying the biomechanics of jumping in plethodontids can inform the evolution and biomechanics of jumping in tetrapods more generally. Although jumping has been recognized as part of the lungless salamander repertoire since the 19th century (Kingsley, 1885; Cochran, 1911; Brodie Jr., 1977; Dowdey & Brodie Jr., 1989), empirical investigations of the underlying biomechanics and kinematics did not appear in the literature until the 21st century (Ryerson, 2013). Consequently, we likely have an incomplete record of how widespread and diverse jumping really is in salamanders. Nevertheless, some progress has been made in the last decade, with jumping now described in both terrestrial (Ryerson, 2013; Ryerson et al., 2016) and arboreal (Brown & Deban, 2020) plethodontids.

In contrast to nearly all other legged vertebrates, jumping plethodontids power propulsion with axial rather than appendicular musculature. They bend the trunk laterally, then rapidly straighten the trunk to propel the body forward (Ryerson, 2013; Ryerson et al., 2016; Hessel & Nishikawa, 2017) (Video 3). Biomechanically, this propulsion mechanism works like a C-start in more aquatic salamanders and amphibious fish (Weihs, 1973), some of which even use it to escape predation on land (Swanson & Gibb, 2004; Gibb et al., 2011). The limbs of plethodontids do not seem to contribute to propulsive power, but they do serve important functions during propulsion and flight. During propulsion, one hindlimb (ipsilateral to the C-shaped bend) is planted on a horizontal surface and acts as a strut to lift the body into the air as the trunk unbends, not unlike a pole-vaulter (Hessel & Nishikawa, 2017). Takeoff velocities of nonarboreal salamanders average 0.9-1.0 m/s (Brown & Deban, 2020), comparable to those of jumping amphibious fishes that rely on similar biomechanics (Perlman, 2016).

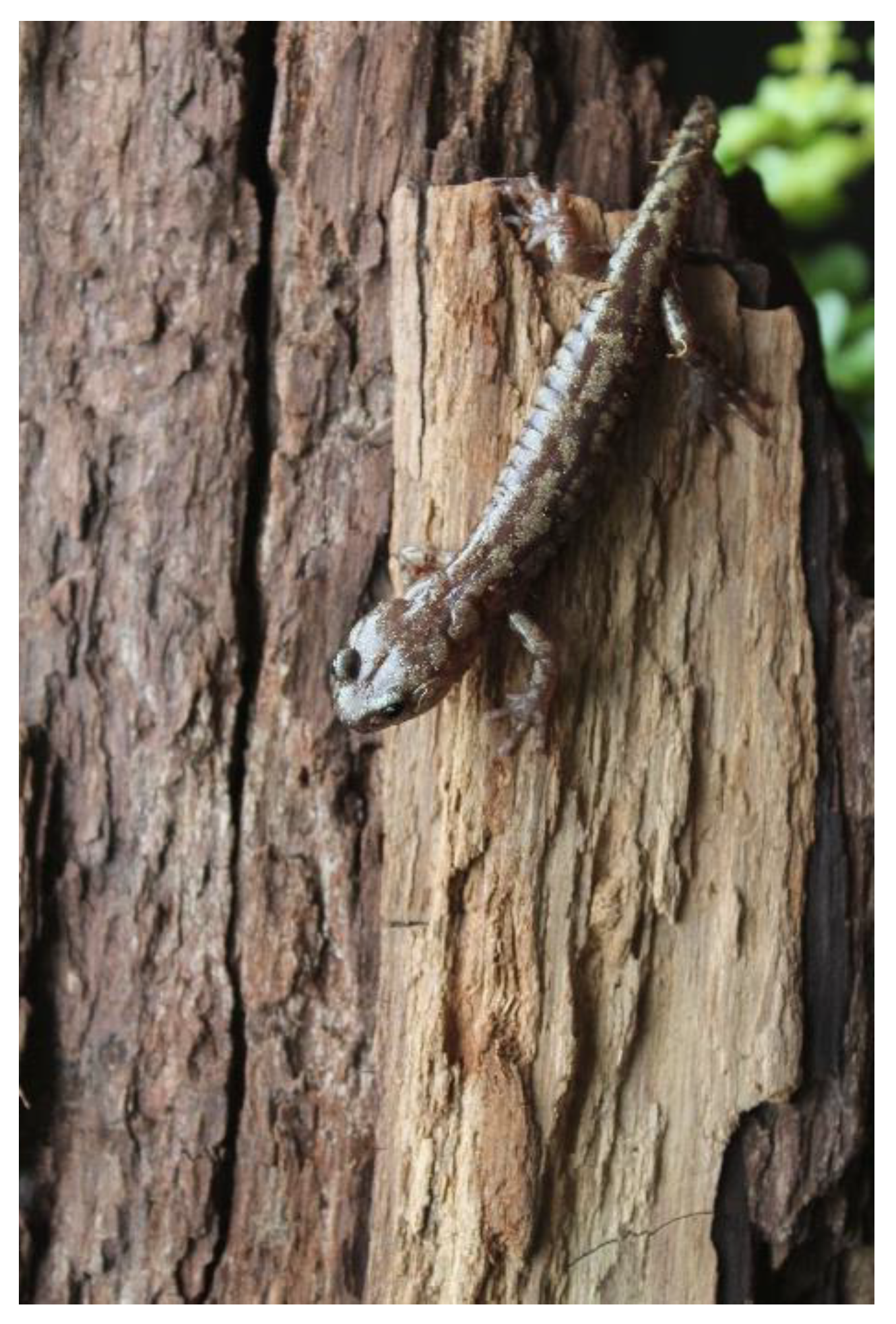

5.2. Jumping in Arboreal Salamanders

Aneides, a genus of climbing plethodontid from North America, contains several species along a gradient of arboreality. The least arboreal species of this genus (e.g., Aneides flavipunctatus, Aneides hardii) are found on the ground in talus slopes, leaf litter, and decaying logs whereas the most arboreal species of this genus (e.g., A. vagrans, Aneides ferreus, Aneides aeneus, Aneides lugubris) are commonly found off the ground in tree crowns, stumps, snags, and elevated crevices of rocky outcrops (Stebbins, 2003; Petranka, 1998). We can use that natural arboreality gradient to structure biomechanical experiments and compare jumping and aerial performance (Brown & Deban, 2020; Brown et al., 2022). Aneides vagrans, known to occupy the crowns of the world’s tallest trees (Sequoia sempervirens), occupies the extreme end of the gradient as arguably the most arboreal plethodontid on Earth, found as far as 88 m up a redwood tree (Sillett, 1999) and consistently captured throughout the redwood canopy between 20-80 m over decades (Spickler et al., 2006; Campbell-Spickler & Sillett, 2017). Miraculously, A. vagrans has been observed leaping from redwood branches ~60 m off the forest floor on more than one occasion (Brown et al., 2022).

The relatively long hindlimbs of Aneides (Brown & Kirk, 2023) play a very different role in jumping compared with nonarboreal plethodontids. During propulsion, Aneides use less lateral bending and frequently toe-off with both feet from a vertical (rather than horizontal) surface (Brown & Deban, 2020) (Video 4). These subtle differences in biomechanics translate to takeoff velocities of ~0.65 m/s (Brown & Deban, 2020), significantly lower than other plethodontids but similar to takeoff velocities of arboreal Anolis lizards (Losos, 1990). Likewise, pushing off with both feet (Video 4) provides a more symmetrical approach to propulsion that likely leads to less rotation in the roll plane during the flight stage of the jump cycle (Yeadon, 2000) and allows Aneides to assume a parachute posture more often and significantly more quickly (~0.042 s) than nonarboreal salamanders (~0.075 s) (Brown & Deban, 2020) (Video 5). Presumably, the combination of lower takeoff velocities, two-foot toe-offs, and rapidly deployed parachute postures all contribute to a more upright body position immediately after propulsion.

5.3. Parachuting and Gliding in Arboreal Salamanders

The tail does not contribute to salamander propulsion (Hessel et al., 2017), but it is essential for both short-term and long-term airborne flights. Shortly after takeoff, all jumping plethodontids assume a stereotypical parachute posture (Brown & Deban, 2020) from which they can use limb and tail movements to correct for body rotations in the roll, yaw, and pitch planes (Brown et al., 2022). Terrestrial salamanders are mostly observed correcting for body rotations in the roll plane resulting from their asymmetrical propulsion strategy (see Video 3), whereas arboreal salamanders are more frequently observed correcting pitch and yaw with their tails. Specifically, the limbs move as coordinated ipsilateral pairs, with a paired adduction of the left fore- and hindlimbs to roll the body left and a paired abduction of the left fore- and hindlimbs to roll the body right, with vice versa outcomes for comparable motion of the right-side limbs. Arboreal salamanders experiencing longer bouts of flight (0-5 s) reliably swing their tails upward through the sagittal plane to pitch head-down and downward to pitch head-up (Video 6). Body yaw is similarly elicited, but with the tail swinging right in the coronal plane to yaw left and swinging left in the coronal plane to yaw right (Brown et al., 2022).

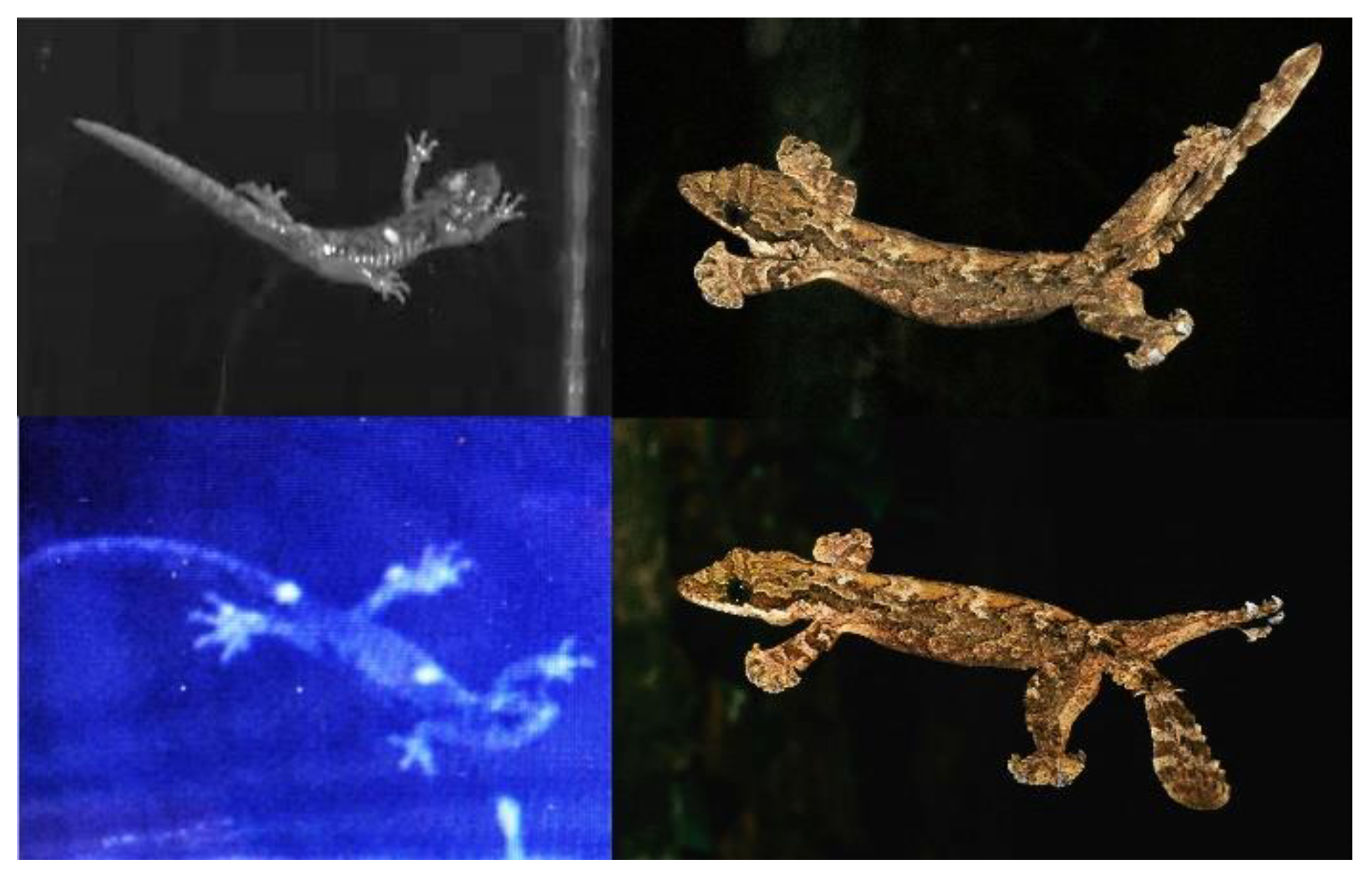

The parachute posture functions to decelerate falling salamanders (Brown et al., 2022) and is characterized by a parasagittal extension of the vertebral column, abduction of all four limbs so that they are maintained perpendicular to the trunk, and rotation of all four feet such that they are prone and retracted slightly above the center of mass (

Figure 6). In this posture, the head and tail point upwards so that the salamander forms a U-shape with the center of mass at the bottom, not unlike a common shuttlecock. Manipulating postures to create a shuttlecock-like shape is a highly effective behavioral adaptation for maintaining upright aerial body positions, one that is shared with an astounding diversity of organisms of all sizes and taxa, including dandelions, springtails, lizards, snakes, and humans (Ortega-Jimenez et al., 2023). The duration and efficacy of parachute postures differs greatly between airborne plethodontids along the arboreality gradient (Brown et al., 2022). While parachuting, the highly arboreal

A. vagrans and

A. lugubris had average instantaneous vertical velocities of 9.40 ms

−1 and 9.90 ms

−1 and accelerations of -0.10 ms

−2 and 0.20 ms

−2, respectively. Brief bouts of parachuting by less arboreal plethodontids (e.g.,

A. flavipunctatus and

Ensatina eschscholtzii) were less effective and never resulted in instantaneous glide angles below ~89°.

Jumping more cautiously seems to be a prudent strategy for maintaining upright aerial postures (Zug, 1978; Yeadon, 2000; Brown & Deban, 2020), but jumping does not always precede flight. Aneides that simply drop or fall from the canopy or experience foot slipping or tail dragging while jumping can find themselves upside- or head-down high above the ground. Luckily, arboreal salamanders have proportionally longer limbs and digits (Stebbins, 2003; Petranka, 1998), morphological distinctions known to aid aerial righting and gliding flight in treefrogs (see Section 3.3). To right themselves, airborne salamanders extend all four limbs dorsolaterally while rapidly rotating the tail, causing the body to counter-rotate, and then immediately assume a parachute posture with the tail held above the body; the entire maneuver takes ~0.116 ± 0.056 s to complete (Ortega-Jimenez et al., 2023). Interestingly, salamanders and treefrogs appear to achieve aerial righting via the same biomechanical principles—extending and rotating appendages behind the body to initiate counter rotations of the body—despite stark differences in caudal morphology. Landing upright and reducing descent speed via parachute postures likely protect leaping and gliding arboreal amphibians from injury during vertical descent (e.g., Savile, 1962).

From an upright, parachute posture, the most arboreal species of

Aneides never thrash or tumble out of control and contrariwise can even manipulate horizontal acceleration to glide at steep angles (Brown et al., 2022). Salamanders glide using postures strikingly similar to those of specialized gliding lizards (

Figure 7), adjusting the angle of their trunk, tail, legs, and feet with respect to the oncoming airflow. The resulting lift provided pulls the salamanders forwards in the horizontal direction, which enables them to glide and turn. Modulating aerial body posture modulates the net aerodynamic force with respect to the center of gravity, allowing gliding salamanders to steer left and right. Whereas lift is indispensable for directing powered flight, salamanders rely predominantly on high drag to slow their descent (see Section 4.4.3).

While gliding, both A. vagrans and A. lugubris retract the limbs dorsally placing the hands and feet above the center of mass. Then, they use repeated parasagittal undulations of the tail and torso to accelerate horizontally, a behavior striking similar to that of gliding geckos (Jusufi et al., 2008). While gliding, A. vagrans and A. lugubris have average instantaneous horizontal velocities of 0.71 ms−1 and 0.35 ms−1 and accelerations of 2.64 ms−2 and 1.90 ms−2, respectively. Instantaneous glide angles average 85.6° for A. vagrans and 87.3° for A. lugubris, though the minimum respective glide angles reported are ~84° and ~85° (Brown et al., 2022). Both species oscillate around a body angle of 0° while gliding, much like gliding geckos (Jusufi et al., 2008).

During flight, neither the tail nor the limbs adduct to prepare for landing. As far as we can tell, all jumping salamanders crash-land in a bellyflop style reminiscent of basal frogs, with the caveat that the limbs are extended laterally rather than posteriorly (Ortega-Jimenez et al., 2023). Even nonarboreal plethodontids reliably correct for body rotations in the roll plane and frequently, but not always, land in a prone position despite asymmetrically propelling themselves into the air over one hindlimb. Impressively, A. vagrans lands in a prone posture over 95% of the time when jumping or dropping from short heights (~3 m) (Brown et al., 2022). During landing, the area near the pectoral girdle touches down first, followed quickly by the posterior half of the trunk, the pelvic girdle and hindlimbs, the head, and finally the tail (see Video 4). The specific landing forces and recovery times associated with salamander jump cycles have not yet been investigated.

5.4. Functional Morphology of Gliding Salamanders

Within Aneides, the same parachute posture is twice as effective for vertical deceleration in A. vagrans compared with A. lugubris and four times as effective compared with A. flavipunctatus. Clearly, something about the morphology of A. vagrans, and to a lesser extent A. lugubris, enables or enhances gliding flight. Morphological features traditionally associated with climbing in salamanders (Stebbins, 2003; Petranka, 1998) may also contribute to incipient forms of flight, like parachuting and gliding (Brown & Kirk, 2023). In this section, we will examine the functional morphologies that gliding salamanders, treefrogs, and other nonvolant tetrapods seem to have converged upon (Khandelwal et al., 2023).

5.4.1. Elongated Hindlimbs

Gliding salamanders have elongated hindlimbs but, like gliding treefrogs from the high canopy, do not employ them to jump further or more powerfully (Gomes et al., 2009; Brown & Deban, 2020). Rather, both gliding salamanders and treefrogs use long hindlimbs to stabilize and correct for body rotations throughout flight. Importantly, elongated hindlimbs allow Aneides to elevate the feet above the center of mass resulting in an effective shuttlecock-like shape while airborne (Ortega-Jimenez et al., 2023). Keeping the center of mass below the aerodynamic control surfaces improves aerodynamic torque and reduces the turning radius, elements of maneuverability that are critical for gliding amphibians (Emerson & Koehl, 1990). It is unclear whether elongated hindlimbs are a functional adaptation for gliding, climbing, or both; however, it is certainly noteworthy that amphibians of different Orders with such disparate Bauplans share such aerodynamically effective morphological features.

5.4.2. Interdigital Webbing

As in gliding treefrogs, the toes of A. vagrans are extended during flight to expand the foot and increase frontal area (Brown et al., 2022). The semi webbed feet of gliding salamanders make up a large proportion of the frontal (~32%) and overall (~28%) surface area when properly oriented in the parachute posture (Brown, 2023). Surface area of the foot has been studied closely in plethodontid salamanders (Adams & Nistri, 2010; O’Donnell & Deban, 2020; Baken & O’Donnell, 2021), especially in neotropical plethodontids from the genus Bolitoglossa (Wake & Lynch, 1976; Alberch, 1981; Alberch & Alberch, 1981). Some arboreal bolitoglossans exhibit reduced digits, expanded foot sole, retained tissue and skin between digits (i.e., webbing), and a central concavity of the foot (Alberch, 1981) that all have potential implications for aerial control. Similarly, European cave salamanders (Hydromantes) also have large, webbed feet and even display rapid evolution towards increased foot surface area in more vertically oriented habitats (Adams & Nistri, 2010; Salvidio et al., 2015; Adams et al., 2017). More rigorous comparative analyses suggest that foot centroid size and contact area correlate with cling performance in plethodontids (O’Donnell & Deban, 2020; Baken & O’Donnell, 2021), but given jumping plethodontids maintain upright aerial postures, parachute, and glide, it is worth reexamining the functional morphology of plethodontid feet in the context of aerial control. The functional morphology of the large, square toe tips of Aneides, which host a large blood sinus on each lateral side, has long been hypothesized to relate to oxygen absorption (Noble, 1925) or clinging and climbing (Stebbins, 2003; Petranka, 1998; O’Donnell & Deban, 2020); however, it remains to be tested whether the toe tips and blood sinuses confer any advantages during flight or landing.

5.4.3. Body Size and Flatness

Body size is perhaps even more important in gliding salamanders than gliding treefrogs because these salamanders do not have fully webbed feet to compensate for the decreased time aloft and glide distance associated with larger size. Because gliding salamanders are relatively small (~5-10 g), they have a lower Re and thus depend more on drag to maneuver in the air. Conveniently, as their body size pre-determines their reliance on pressure drag, gliding salamanders have relatively flat bodies that maximize the pressure drag they have to work with while airborne (Brown & Kirk, 2023). By comparison, salamanders that are more rounded are more streamlined and plummet faster (i.e., reduced time aloft) in the same orientation (Brown & Kirk, 2023). Dorsoventral flatness, another morphological feature attributed to helping Aneides climb (Stebbins, 2003; Petranka, 1998), is common in other gliding herpetofauna (e.g., Hemidactylus), some of which even augment aerial performance by actively flattening the body during flight (e.g., Chrysopelea) (Socha, 2011). Active dorsoventral flattening during the jump cycle is a possibility that remains to be tested in Aneides.

5.5. Ecological Applications of Gliding in Salamanders

Interestingly, Aneides will only jump outwards and downwards from perches whereas nonarboreal plethodontids readily jump upwards and outwards over gaps (Ryerson et al., 2016; Brown & Deban, 2020). This behavior, taken together with their relatively steep glide angles, hints at the ecological application of leaping and gliding by A. vagrans; by all indications, these salamanders leap and direct their descent within their home crowns but cannot glide between canopy trees (Brown et al., 2022). These ancient trees can be thousands of years old and have complex crowns with upwards of sixty vertical branches and reiterated trunks creating a plethora of crotches and an array of epiphytic fern mats that sustain entire populations of A. vagrans (Sillett, 1999; Spickler et al., 2006; Sillett & Van Pelt, 2007). Airborne A. vagrans can hypothetically intercept the home trunk or lower branches of an old-growth coast redwood if descending from the crown at a conservatively estimated equilibrium glide angle of 85° (Brown et al., 2022). Gliding into a vertical trunk, especially at high translational velocities, may not be effective for landing given the tendency of salamanders to land in a belly flop. However, the abundance of relatively soft, spongey, horizontally oriented fern mats in the crowns of coast redwoods (Sillett & Bailey, 2003) suggests that A. vagrans could instead belly flop onto lower mats to stay aloft. Gliding from one fern mat to another would be a relatively fast way to escape from predators, such as owls and omnivorous mammals (Aretz et al., 2021). That A. vagrans readily jumps from branches as high as ~60 m in the redwood canopy (Video 7) suggests that this may be a common behavioral response to stimuli yet to be characterized in-situ.

Gliding could also be an energy-efficient mode of vertical locomotion for arboreal salamanders not escaping predators but otherwise trying to descend trees (Norberg, 1981; Stewart, 1985; Rayner, 1988; Norberg, 2012; Aretz et al., 2021), perhaps part of an efficient foraging strategy (Savile, 1962). Crown-dwelling

A.

vagrans are highly associated with epiphytic fern mats that hold moisture like sponges and host population explosions of invertebrates (

Collembola) during the rainy season (Jones, 2005). As the clouds and fog lift at the end of the rainy season, the upper canopy receives more light and wind and less humidity compared with the lower canopy (Parker, 1995; Sillett & Van Pelt, 2007). Fern mats in the upper canopy are thus subjected to more frequent and severe periods of desiccation than those in the lower canopy. Salamanders that disperse into the upper crown in search of food and mates during the wet season (i.e., resource boom) might glide into the lower canopy to find more prey or avoid desiccation during the dry season (i.e., resource bust). The only alternative way to locomote downwards, walking down the redwood trunk, just prolongs exposure to desiccation (and predation) and would hypothetically require greater expenditure of energy (Norberg, 1981; Full, 1986; Feder, 1987).

A. vagrans is reluctant to walk straight down and does so less efficiently than walking upward or horizontally, hypothetically increasing the total distance traveled and energy burned (Aretz et al., 2021) (

Figure 8).

That canopy-dwelling salamanders have been observed leaping from great heights (~60 m) suggests that A. vagrans routinely undergoes aerial descent. However, the kinematics of gliding still need to be rigorously tested in-situ to get an idea of how arboreal salamanders perform under natural conditions. A general lack of aerodynamic stability suggests that A. vagrans could be susceptible to being blown off-course by wind gusts (McCay, 2003). Furthermore, the morphological features that help A. vagrans glide (e.g., semi webbed feet and flat Bauplan) are seen in other arboreal plethodontids and warrant deeper investigations of jumping and gliding flight in a wider range of species.

6. Concluding Remarks

Amphibians have come to occupy almost every conceivable terrestrial niche available to nonvolant vertebrates, owing their success in part to impressive adaptations for locomotion in the water, on land, and even in the air. While arboreal reptiles (Chapters 4-6), birds (Chapters 7-9), and mammals (Chapters 10-18) might provide more striking examples of morphological adaptations for aerial control, arboreal amphibians represent the most basal nonvolant tetrapods. Specifically, arboreal salamanders have great potential for serving as models for incipient forms of flight in other nonspecialized tetrapods, especially once we establish descriptions of aerial behavior in a wider diversity of plethodontids.

Behaviorally, canopy-dwelling salamanders and treefrogs both seem to jump more cautiously and employ similar limb movements to correct for body rotations after takeoff; additionally, they maintain parachute postures and spread and extend their toes to fan out the webbed feet during flight. Both gliding salamanders and treefrogs frequently position their relatively large feet above the center of mass, improving aerodynamic torque and maneuverability important for aerial locomotion. Morphologically, gliding salamanders (Aneides) and gliding treefrogs (e.g., Rhacophorus, Agalychnis, Ecnomiohyla) are somewhat similar because they all possess relatively long hindlimbs and greater interdigital webbing compared with nongliding species within their respective families. Dorsoventrally flattened bodies contribute to higher lift:drag ratios in salamanders (Brown & Kirk, 2023), and many treefrogs sport lateral skin flaps that should function in much the same way. Arboreal salamanders and treefrogs both seem to have co-opted and expanded upon morphologies with high relative surface area, resulting in larger attachment areas that benefit clinging and climbing and higher lift:drag ratios that benefit gliding. Interestingly, these convergent behaviors and morphologies are also common in nonamphibious gliders, from fellow vertebrates like geckos and snakes (Young et al., 2002; Jusufi et al., 2008; Socha, 2011) to invertebrates like ants and spiders (Yanoviak et al., 2005; Yanoviak et al., 2015).

Arboreal salamanders and treefrogs also appear to have converged upon similar aerial righting biomechanics, despite stark differences in caudal morphology. Both taxa return to and maintain a prone aerial body position by posteriorly extending and rotating appendages behind the body just once to initiate a counter rotation of the body, then reassuming the parachute posture to prevent overcorrecting and rotating out of control. Airborne arboreal salamanders rotate the tail to initiate the counter-rotation of the body, just like geckos (Jusufi et al., 2011; Siddall et al., 2021), whereas airborne treefrogs employ the same inertial strategy but extend the hindlimbs posteriorly to substitute for a tail (Wang et al., 2013). It seems that rotating a tail, or at least an appendage where a tail would be, is vital for aerial righting in airborne amphibians.

Given what we now know about the convergent functional morphology of leaping and gliding in amphibians and gliding vertebrates in general (Khandelwal et al., 2023), we will offer a few predictions. First, we predict that there should be at least several more species of gliding salamander, both inside and outside genus Aneides. Within Aneides, we suspect that hatchlings and juveniles might benefit from lower Re and exhibit shallower glide angles; a scaling experiment is needed to test this prediction. Second, we predict that newly recognized gliding species will be arboreal, occupying tree crowns and forest canopies (e.g., Bolitoglossa) as almost half of tropical plethodontids do facultatively (McEntire, 2016). Lastly, we predict that salamanders with webbed feet (e.g., Chiropterotriton magnipes) and long hindlimbs (e.g., Nyctanolis) are more likely to exhibit aerial control. Specifically, Ixalotriton niger is a prolific jumper from Chiapas, Mexico that has been found wandering around on the trunks of trees rich in bromeliads; they even leap away from tree trunks or off understory leaves when disturbed (Amphibiaweb), suggesting they might frequently engage in long-term airborne flight to avoid predators.

Finally, the discovery of gliding in a salamander from a temperate rainforest with the tallest canopy on Earth, a canopy already known to harbor an endemic flying squirrel, Glaucomys oregonensis (Arbogast et al., 2017), rekindles hypotheses about the environmental drivers of gliding evolution. The ancient coast redwood forests of northern California, although temperate, are not completely unlike the tropical dipterocarp rainforests of Southeast Asia where Wallace first marveled at flying frogs. Both forests are characterized by tall dominant tree species, high canopies connected by relatively few lianas, and boom-bust resource cycling that might select for gliding flight in vertebrates. The tall redwood canopy provides enough vertical space to make gliding ecologically relevant and possible, as gliding animals go through an initial falling phase after jumping (i.e., the ballistic dive) before they glide (Abdulali & Sekar, 1988; Emerson & Koehl, 1990; McGuire & Dudley, 2005; Socha et al., 2005; Bahlman et al., 2013). The Mediterranean-like climate in the coast redwood forest leads to boom-bust cycling of precipitation, fog, and invertebrate prey that depend on moisture; additionally, the canopy dries out from upper-to-lower crown throughout the summer, which could encourage animals to efficiently drop or leap to habitat on lower branches. It is possible that ancient redwood forests function as less biodiverse, temperate cradles for the evolution of incipient forms of flight, and we look forward to future investigations of aerial performance in other small, nonvolant amphibians, like Pacific treefrogs (Hyla regilla), which are known to locomote through the redwood canopy but have not been tested for gliding.

Acknowledgements

Insights on salamanders that inhabit the redwood canopy would not be possible without the pioneering efforts of scientists Jim Campbell-Spickler, Sharyn Marks, Steve Sillett, and Hartwell Welsh, as well as everyone involved in the ongoing movement to protect old-growth redwood groves. An acknowledgement is extended to the British Broadcasting Corporation, National Geographic, and Humblebee Films for sponsoring and shooting separate documentary scenes of the jumping and aerial behavior in canopy salamanders, thus generating data and leading to new avenues of arboreal locomotion research. Data collection and interpretation was greatly assisted by Jessalyn Aretz and Alexander M. Kirk. I am also grateful to Mary Kate O’Donnell for enlightening conversations about salamander feet, and to Stephan Deban, Robert Dudley, and Erik Sathe for critically reading this manuscript. Funding for research pertaining to gliding salamanders was provided in part by the Fern Garden Club of Odessa, the Porter Family Foundation, the Fred L. and Helen M. Tharp Fellowship, the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology’s (SICB) Fellowship for Graduate Student Travel (FGST), and USF’s Office of Graduate Studies and Integrative Biology Department.

References

- Abdulali, H., & Sekar, A. (1988). On a small collection of amphibians from Goa. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc, 85, 202-205. [CrossRef]

- Adams, D. C., & Nistri, A. (2010). Ontogenetic convergence and evolution of foot morphology in European cave salamanders (Family: Plethodontidae). BMC Evolutionary Biology, 10(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Adams, D. C., Korneisel, D., Young, M., & Nistri, A. (2017). Natural history constrains the macroevolution of foot morphology in European plethodontid salamanders. The American Naturalist, 190(2), 292-297. [CrossRef]

- Alberch, P. (1981). Convergence and parallelism in foot morphology in the neotropical salamander genus Bolitoglossa. I. Function. Evolution, 84-100. [CrossRef]

- Alberch, P., & Alberch, J. (1981). Heterochronic mechanisms of morphological diversification and evolutionary change in the neotropical salamander, Bolitoglossa occidentalis (Amphibia: Plethodontidae). Journal of Morphology, 167(2), 249-264. [CrossRef]

- AmphibiaWeb. 2023. (https://amphibiaweb.org) University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Accessed 26 May 2023.

- AmphibiaWeb. 2007. Ixalotriton niger: Black Jumping Salamander (https://amphibiaweb.org/species/4082) University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA. Accessed Jun 8, 2023.

- Anderson, J. D. (1998). A history of aerodynamics: and its impact on flying machines (No. 8). Cambridge University Press.

- Anderson, B. D., Feder, M. E., & Full, R. J. (1991). Consequences of a gait change during locomotion in toads (Bufo woodhousii fowleri). Journal of experimental biology, 158(1), 133-148. [CrossRef]

- Appanah, S., Gentry, A. H., & LaFrankie, J. V. (1993). Liana diversity and species richness of Malaysian rain forests. Journal of Tropical Forest Science, 116-123.

- Aretz, J., Brown, C. E., & Deban, S. M. (2021). Vertical locomotion in the arboreal salamander Aneides vagrans. Zoology, 316, 72-79. [CrossRef]

- Arbogast, B. S., Schumacher, K. I., Kerhoulas, N. J., Bidlack, A. L., Cook, J. A., & Kenagy, G. J. (2017). Genetic data reveal a cryptic species of New World flying squirrel: Glaucomys oregonensis. Journal of Mammalogy, 98(4), 1027-1041. [CrossRef]

- Ascarrunz, E., Rage, J. C., Legreneur, P., & Laurin, M. (2016). Triadobatrachus massinoti, the earliest known lissamphibian (Vertebrata: Tetrapoda) re-examined by μCT scan, and the evolution of trunk length in batrachians. Contributions to Zoology, 85(2), 201-234. [CrossRef]

- Astley, H. C., Haruta, A., & Roberts, T. J. (2015). Robust jumping performance and elastic energy recovery from compliant perches in tree frogs. Journal of Experimental Biology, 218(21), 3360-3363. [CrossRef]

- Aubert, M., Setiawan, P., Oktaviana, A. A., Brumm, A., Sulistyarto, P. H., Saptomo, E. W., Istiawan, B., Ma’rifat, T. A., Wahyuono, V. N., Atmoko, F. T., Zhao, J.-X., Huntley, J., Taçon, P. S. C., Howard, D. L., & Brand, H. E. A. (2018). Palaeolithic cave art in Borneo. Nature, 564(7735), 254-257. [CrossRef]

- Azizi, E., Larson, N. P., Abbott, E. M., & Danos, N. (2014). Reduce torques and stick the landing: limb posture during landing in toads. Journal of Experimental Biology, 217(20), 3742-3747. [CrossRef]

- Azizi, E., & Roberts, T. J. (2010). Muscle performance during frog jumping: influence of elasticity on muscle operating lengths. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277(1687), 1523-1530. [CrossRef]

- Bahlman, J. W., Swartz, S. M., Riskin, D. K., & Breuer, K. S. (2013). Glide performance and aerodynamics of non-equilibrium glides in northern flying squirrels (Glaucomys sabrinus). Journal of the Royal Society interface, 10(80), 20120794. [CrossRef]

- Baken, E. K., & O’Donnell, M. K. (2021). Clinging ability is related to particular aspects of foot morphology in salamanders. Ecology and evolution, 11(16), 11000-11008. [CrossRef]

- Barnes, W. J. P., Goodwyn, P. J. P., Nokhbatolfoghahai, M., & Gorb, S. N. (2011). Elastic modulus of tree frog adhesive toe pads. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 197, 969-978. [CrossRef]

- Barrionuevo, J. S. (2016). Independent evolution of suction feeding in Neobatrachia: feeding mechanisms in two species of Telmatobius (Anura: Telmatobiidae). The Anatomical Record, 299(2), 181-196. [CrossRef]

- Bijma, N. N., Gorb, S. N., & Kleinteich, T. (2016). Landing on branches in the frog Trachycephalus resinifictrix (Anura: Hylidae). Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 202, 267-276. [CrossRef]

- Blankers, T., Adams, D. C., & Wiens, J. J. (2012). Ecological radiation with limited morphological diversification in salamanders. Journal of evolutionary biology, 25(4), 634-646. [CrossRef]

- Blaustein, A. R. (1990). Declining amphibian populations: a global phenomenon?. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 5, 203-204. [CrossRef]

- Bonett, R. M., & Blair, A. L. (2017). Evidence for complex life cycle constraints on salamander body form diversification. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(37), 9936-9941. [CrossRef]

- Brodie Jr, E. D. (1977). Salamander antipredator postures. Copeia, 523-535. [CrossRef]

- Brodie Jr, E. D. (1978). Biting and vocalization as antipredator mechanisms in terrestrial salamanders. Copeia, 127-129. [CrossRef]

- Brown, C. E. (2023). How Some Arboreal Salamanders (Genus Aneides) Jump, Glide, and Generate Lift (Doctoral dissertation, University of South Florida).

- Brown, C. E., & Deban, S. M. (2020). Jumping in arboreal salamanders: a possible tradeoff between takeoff velocity and in-air posture. Zoology, 138, 125724. [CrossRef]

- Brown, C. E., & Kirk, A. M. (2023). Characterizing lift, drag, and pressure differences across wandering salamanders (Aneides vagrans) with computational fluid dynamics to investigate aerodynamics. Journal of Morphology. [CrossRef]

- Brown, C. E., Sathe, E. A., Dudley, R., & Deban, S. M. (2022). Aerial maneuvering by plethodontid salamanders spanning an arboreality gradient. Journal of Experimental Biology, 225(20), jeb244598. [CrossRef]

- Bury, R. B. (1972). Small mammals and other prey in the diet of the Pacific giant salamander (Dicamptodon ensatus). American Midland Naturalist, 524-526. [CrossRef]

- Campbell-Spickler, J., & Sillett, S. C. (2017). Redwood experimental forest: a sentinel site for biodiversity response to climate change. USDA Report.

- Chan, K. O., Grismer, L. L., Zachariah, A., Brown, R. M., & Abraham, R. K. (2016). Polyphyly of Asian tree toads, genus Pedostibes Günther, 1876 (Anura: Bufonidae), and the description of a new genus from Southeast Asia. PLoS One, 11(1), e0145903. [CrossRef]

- Citadini, J. M., Brandt, R., Williams, C. R., & Gomes, F. R. (2018). Evolution of morphology and locomotor performance in anurans: relationships with microhabitat diversification. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 31(3), 371-381. [CrossRef]

- Cochran, M. E. (1911). The biology of the red-backed salamander (Plethodon cinereus erythronotus Green). The Biological Bulletin, 20(6), 332-349. [CrossRef]

- Cott, H. B. (1926, December). Observations on the Life-Habits of some Batrachians and ‘Reptiles from the Lower Amazon: and a Note on some Mammals from Marajó Island. In Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London (Vol. 96, No. 4, pp. 1159-1178). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Cox, S. M., & Gillis, G. B. (2015). Forelimb kinematics during hopping and landing in toads. Journal of Experimental Biology, 218(19), 3051-3058. [CrossRef]

- Cox, S. M., Ekstrom, L. J., & Gillis, G. B. (2018). The influence of visual, vestibular, and hindlimb proprioceptive ablations on landing preparation in cane toads. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 58(5), 894-905. [CrossRef]

- Dang, N. X., Wang, J. S., Liang, J., Jiang, D. C., Liu, J., Wang, L., & Li, J. T. (2018). The specialisation of the third metacarpal and hand in arboreal frogs: Adaptation for arboreal habitat?. Acta Zoologica, 99(2), 115-125. [CrossRef]

- Deban, S. M., Wake, D. B., & Roth, G. (1997). Salamander with a ballistic tongue. Nature, 389(6646), 27-28. [CrossRef]

- Deban, S. M. (2003). Constraint and convergence in the evolution of salamander feeding. In: Vertebrate Biomechanics and Evolution, J.-P. Gasc, A. Casinos, and V.L. Bels, eds., BIOS Scientific Publishers, Oxford. 163-180.

- Dehling, J. M. (2012). Hyperolius discodactylus (disc-fingered reed frog): parachuting. Herpetological Review, 43, 463.

- Dehling, J. M., & Sinsch, U. (2023). Amphibians of Rwanda: Diversity, Community Features, and Conservation Status. Diversity, 15(4), 512. [CrossRef]

- Denny, M. (1993). Air and water: the biology and physics of life’s media. Princeton University Press.

- Dong, H., Bode-Oke, A. T., & Li, C. (2018). Learning from nature: unsteady flow physics in bioinspired flapping flight. Flight physics-models, techniques and technologies.

- Dowdey, T. G., & Brodie Jr, E. D. (1989). Antipredator strategies of salamanders: individual and geographical variation in responses of Eurycea bislineata to snakes. Animal Behaviour, 38(4), 707-711. [CrossRef]

- Dudley, R., Byrnes, G., Yanoviak, S. P., Borrell, B., Brown, R. M., & McGuire, J. A. (2007). Gliding and the functional origins of flight: biomechanical novelty or necessity?. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst., 38, 179-201. [CrossRef]

- Dudley, R., & DeVries, P. (1990). Tropical rain forest structure and the geographical distribution of gliding vertebrates. Biotropica, 22(4), 432-434. [CrossRef]

- Dudley, R. and Yanoviak, S. P. (2011). Animal aloft: The origins of aerial behavior and flight. Integrative & Comparative Biology, 51(6), 926–936. [CrossRef]

- Duellman, W. E. (2001). The Hylid Frogs of Middle America. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles, Ithaca, New York.

- Duellman, W. E., & Trueb, L. (1994). Biology of amphibians. JHU press.

- Ekstrom, L. J., & Gillis, G. B. (2015). Pre-landing wrist muscle activity in hopping toads. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 218(15), 2410-2415. [CrossRef]

- Emerson, S. B. (1978). Allometry and jumping in frogs: helping the twain to meet. Evolution, 551-564. [CrossRef]

- Emerson, S. B. (1982). Frog postcranial morphology: identification of a functional complex. Copeia, 603-613. [CrossRef]