Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

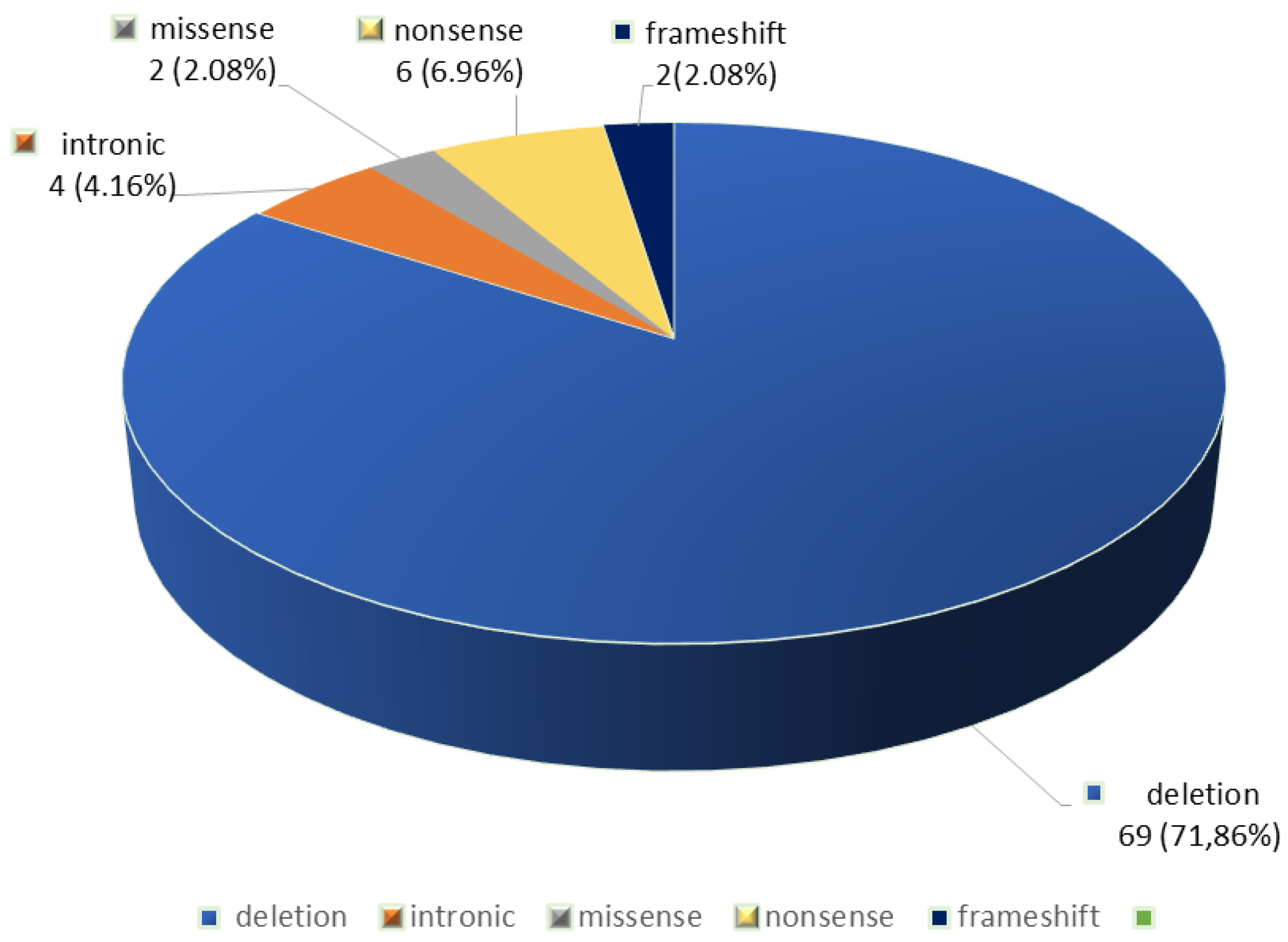

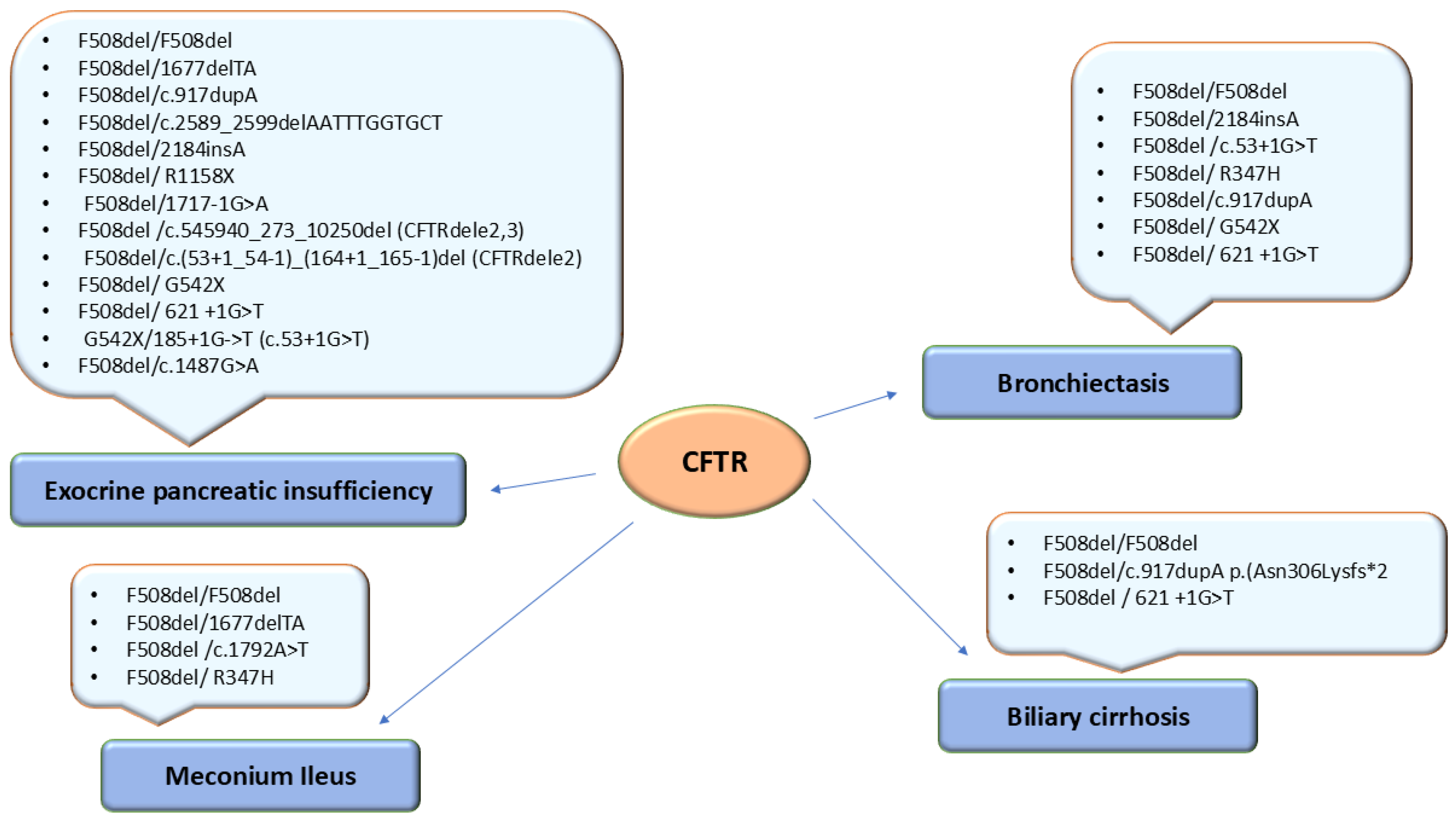

3. Results

4. Discussions

Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Online Inherithance of Man (OMIM). Available online: https://omim.org/entry/602421?search=CFTR&highlight=cftr, (accessed on 6 March 2025).

- Diab Cáceres, L.; Zamarrón de Lucas, E. Cystic fibrosis: Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Med Clin (Barc). 2023, 161(9),389-396.

- Savant, A.; Lyman, B.; Bojanowsk, C.; Upadia, J.Cystic Fibrosis. 2001 Mar 26 [Updated 2024 Aug 8]. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1250/, (accessed on 7 March 2025).

- Crespo-Lessmann, A.; Bernal, S.; Del Río, E.; Rojas, E.; Martínez-Rivera, C.; Marina, N.; Pallarés-Sanmartín, A.; Pascual, S.; García-Rivero, J.L.; ,Padilla-Galo A. Association of the CFTR gene with asthma and airway mucus hypersecretion. PLoS One. 2021, 16(6), e0251881.

- Yu, C.; Kotsimbos, T. Respiratory Infection and Inflammation in Cystic Fibrosis: A Dynamic Interplay among the Host, Microbes, and Environment for the Ages. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24(4),4052. [CrossRef]

- Cystic Fibrosis Mutations Database. Available online: http://www.genet.sickkids.on.ca/StatisticsPage.html, accessed on 6 March 2025.

- Rueda-Nieto, S.; Mondejar-Lopez, P.; Mira-Escolano, M.P.; Cutillas-Tolín, A.; Maceda-Roldán, L.A.; Arense-Gonzalo, J.J.; Palomar-Rodríguez, J.A. Analysis of the genotypic profile and its relationship with the clinical manifestations in people with cystic fibrosis: study from a rare disease registry. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2022,17(1):222. [CrossRef]

- Van Rens, J.; Fox, A.; Krasnyk, M.; Orenti, A.; Zolin, A.; Jung, A.; Naehrlich, L. The European Cystic Fibrosis Society Patient Registry’s Data Quality programme. In 10th European Conference on Rare Diseases & Orphan Products (ECRD 2020). Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020, 15 (Suppl 1), 310 .

- Mei-Zahav, M., Orenti, A.; Jung, A.; Kerem, E. Variability in disease severity among cystic fibrosis patients carrying residual-function variants: data from the European Cystic Fibrosis Society Patient Registry. ERJ Open Res. 2025 , 11(1), 00587-2024. [CrossRef]

- Petrova, N.; Balinova, N.; Marakhonov, A.; Vasilyeva, T.; Kashirskaya, N.; Galkina, V.; Ginter, E.; Kutsev, S.; Zinchenko, R. Ethnic Differences in the Frequency of CFTR Gene Mutations in Populations of the European and North Caucasian Part of the Russian Federation. Front Genet. 2021,12, 678374. [CrossRef]

- Estivill, X.; Bancells, C.; Ramos, C. Geographic distribution and regional origin of 272 cystic fibrosis mutations in European populations. The Biomed CF Mutation Analysis Consortium. Hum Mutat. 1997, 10(2),135-54.

- WHO Human Genetics Programme. (2004). The molecular genetic epidemiology of cystic fibrosis : report of a joint meeting of WHO/IECFTN/ICF(M)A/ECFS, Genoa, Italy, 19 June 2002. World Health Organization. Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/68702, (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Abeliovich, D.; Lavon, I.P.; Lerer, I.; Cohen, T.; Springer, C.; Avital, A.; Cutting, G.R. Screening for five mutations detects 97% of cystic fibrosis (CF) chromosomes and predicts a carrier frequency of 1:29 in the Jewish Ashkenazi population. Am J Hum Genet. 1992, 51(5), 951-6.

- Messaoud, T.; Bel Haj Fredj, S.; Bibi, A.; Elion, J.; Férec, C.; Fattoum, S. Epidémiologie moléculaire de la mucoviscidose en Tunisie [Molecular epidemiology of cystic fibrosis in Tunisia]. Ann Biol Clin (Paris). 2005, 63(6), 627-30.

- Marson, F.A.L.; ,Bertuzzo C.S.; Ribeiro, J.D. Classification of CFTR mutation classes. Lancet Respir Med. 2016, 4(8), e37-e38.

- Stanke, F.; Tümmler, B. Classification of CFTR mutation classes. Lancet Respir Med. 2016, 4(8), e36. [CrossRef]

- De Boeck, K.; Amaral, M.D. Progress in therapies for cystic fibrosis. Lancet Respir Med. 2016, 4(8), 662-674.

- Zemanick, E.T.; Emerman, I.; McCreary, M.; Mayer-Hamblett, N.; Warden, M.N.; Odem-Davis, K.; VanDevanter, D.R.; Ren, C.L.; Young, J.; Konstan, M.W.; et al. Heterogeneity of CFTR modulator-induced sweat chloride concentrations in people with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2024, 23(4), 676-684. [CrossRef]

- Lopes-Pacheco, M. CFTR modulators: the changing face of cystic fibrosis in the era of precision medicine. Front Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1662. [CrossRef]

- Butnariu, L.I.; Țarcă, E.; Cojocaru, E.; Rusu, C.; Moisă, Ș.M.; ,Leon Constantin M.M.; Gorduza, E.V.;Trandafir, L.M. Genetic Modifying Factors of Cystic Fibrosis Phenotype: A Challenge for Modern Medicine. J Clin Med. 2021, 10(24), 5821.

- Mésinèle, J.; Ruffin, M.; Guillot, L.; Corvol, H. Modifier Factors of Cystic Fibrosis Phenotypes: A Focus on Modifier Genes. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23(22),14205. [CrossRef]

- Varkki, S.D.; Aaron, R.; Chapla, A.; Danda, S.; Medhi, P.; Jansi Rani, N.; Paul, G.R. CFTR mutations and phenotypic correlations in people with cystic fibrosis: a retrospective study from a single centre in south India. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2024, 27, 100434. [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, A.; Keenan, K.; Ooi, C.Y.; Dorfman, R.; Sontag, M.K.; Naehrlich, L:, Castellani, C.; Strug, L.J.; Rommens, J.M.; Gonska, T. Prevalence of meconium ileus marks the severity of mutations of the Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR) gene. Genet Med. 2016, 18(4), 333-40. [CrossRef]

- Frenţescu, L.; Brownsell, E.; Hinks, J.; Malone, G.; Shaw, H.; Budişan, L.; Bulman, M.; Schwarz, M.; Pop, L.; Filip, M et al. The study of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene mutations in a group of patients from Romania. J Cyst Fibros. 2008, 7(5), 423-8. [CrossRef]

- Sciuca, S.; Turcu, O.; Posselt, H.G.; Fergelot, P.; Hedtfeld, S.; Sylvie Labatut, S.; Oberkanins, C.; Pühringer, H.; Reboul, M. P.; Tümmler, B. CFTR mutations of patients with cystic fibrosis from Republic of Moldova., MJHS, 2015, 3, 27-30. Available online:https://repository.usmf.md/bitstream/20.500.12710/2445/1/Mutatiile_CFTR_la_pacientii_cu_fibroza_chistica_din_RM.pdf, accesed on 13 March 2025.

- Kasmi, I.; Kasmi, G.; Basholli, B.; Sefa, H.S.; ,Vevecka E. The Spectrum and Frequency of Cystic Fibrosis Mutations in Albanian Patients. Balkan J Med Genet. 2024, 27(1), 31-36.

- Petrova, G.; Yaneva, N.; Hrbková, J.; Libik, M.; Savov, A.; Macek, M. Jr. Identification of 99% of CFTR gene mutations in Bulgarian,Bulgarian Turk, and Roma cystic fibrosis patients. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2019, 7(8), e696.

- Křenková, P.; Piskáčková, T.; Holubová, A.; Balaščaková, M.; Krulišová, V.; Čamajová, J.; Turnovec, M.; Libik, M.; Norambuena, P.; Štambergová A et al. Distribution of CFTR mutations in the Czech population: positive impact of integrated clinical and laboratory expertise, detection of novel/de novo alleles and relevance for related/derived populations. J Cyst Fibros. 2013, 12(5), 532-7. [CrossRef]

- Apostol, P.; Cimponeriu, D.; Radu, I.; Gavrila, L. The analysis of some CFTR gene mutations in a small group of cf patients from southern part of Romania. Analele Univ din Oradea Fasc Biol [Internet]. 2009, TOM XVI(1), 8-11. Available online: https://bioresearch.ro/2009-1/008-11-APOSTOL.P.-An.U.O.Bio.2009.1.pdf.

- Dobre, M.; Chesaru, B.; Romila, A.; Tutunaru, D.; Gurău, G. Cystic fibrosis in Romanian children [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2020 Apr 3]. Available online: https://www.re searchgate.net/publication/279202066_Cystic_fibrosis_in_Romanian_children, accessed on 19 March 2025.

- Popa, I.; Pop, L.; Popa, Z.; Schwarz, M.J.; Hambleton, G.; Malone, G.M.; Haworth, A.; Super, M. Cystic fibrosis mutations in Romania. Eur J Pediatr. 1997, 156(3), 212-3. [CrossRef]

- European Cystic Fibrosis Society Pacient Registry. ECFSPR Annual Report 2021. Zolin A, Orenti A, Jung A, van Rens J et al, 2023. Available online: https://www.ecfs.eu/sites/default/files/Annual%20Report_2021_09Jun2023.pdf, (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Ideozu, J.E.; Liu, M.; Riley-Gillis, B.M.; Paladugu, S.R.; Rahimov, F.; Krishnan, P.; Tripathi, R.; Dorr, P, Levy, H.; ,Singh A.; et al. Diversity of CFTR variants across ancestries characterized using 454,727 UK biobank whole exome sequences. Genome Med. 2024,16(1), 43.

- Brennan, M.L.; Schrijver, I. Cystic Fibrosis: A Review of Associated Phenotypes, Use of Molecular Diagnostic Approaches, Genetic Characteristics, Progress, and Dilemmas. J Mol Diagn. 2016, 18(1), 3-14.

- Casals, T.; Nunes, V.; Palacio, A.; Giménez, J.; Gaona, A.; Ibáñez, N.; Morral, N.; Estivill, X. Cystic fibrosis in Spain: high frequency of mutation G542X in the Mediterranean coastal area. Hum Genet. 1993, 91(1), 66-70.

- Rosa, K.M.D.; Lima, E.D.S.; Machado, C.C.; Rispoli, T.; Silveira, V.D.; Ongaratto, R.; Comaru, T.; Pinto, L.A. Genetic and phenotypic traits of children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis in Southern Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2018, 44(6), 498-504. [CrossRef]

- McHugh, D.R.; Steele, M.S.; Valerio, D.M.;Miron, A.; Mann, R.J.; LePage, D.F.; Conlon, R.A.; Cotton, C.U.; Drumm, M.L.; Hodges, C.A. A G542X cystic fibrosis mouse model for examining nonsense mutation directed therapies. PLoS One. 2018, 13(6), e0199573. [CrossRef]

- Viotti Perisse, I.; Fan, Z.; Van Wettere, A.; Liu, Y.; Leir, S.H.; Keim, J.; Regouski, M.; Wilson, M.D.; Cholewa, K.M.; Mansbach, S.N.; et al. Sheep models of F508del and G542X cystic fibrosis mutations show cellular responses to human therapeutics. FASEB Bioadv. 2021, 3(10), 841-854. [CrossRef]

- ClinVar database. Available online; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/, accessed on 29 March 2025.

- Ooi, C.Y.; Durie, P.R. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene mutations in pancreatitis. J Cyst Fibros. 2012, 11(5), 355-62. [CrossRef]

- Bienvenu, T.; Viel, M.; Leroy, C.; Cartault, F.; Lesure, J.F.; Renouil, M. Spectrum of CFTR mutations on Réunion Island: impact on neonatal screening. Hum Biol. 2005, 77(5), 705-14. [CrossRef]

- Indika, N.L.R.; Vidanapathirana, D.M.; Dilanthi, H.W.; Kularatnam, G.A.M.; Chandrasiri, N.D.P.D.; Jasinge ,E. Phenotypic spectrum and genetic heterogeneity of cystic fibrosis in Sri Lanka. BMC Med Genet. 2019, 20(1), 89. [CrossRef]

- https://cftr2.org/mutations_history, (accessed on 29 March 2025).

- Zielenski, J.; Bozon, D.; Markiewicz, D.; Aubin, G.; Simard, F.; Rommens, J.M.; Tsui, L.C. Analysis of CFTR transcripts in nasal epithelial cells and lymphoblasts of a cystic fibrosis patient with 621 + 1G-->T and 711 + 1G-->T mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 1993, 2(6), 683-7. [CrossRef]

- De Braekeleer, M.; Allard, C.; Leblanc, J.P.; Simard, F.; Aubin, G. Genotype-phenotype correlation in five cystic fibrosis patients homozygous for the 621 + 1G-->T mutation. J Med Genet. 1997, 34(9), 788-9. [CrossRef]

- Petrova, N.V.; Kashirskaya, N.Y.; Vasilyeva, T.A.; Kondratyeva, E.I.; Zhekaite, E.K.; Voronkova, A.Y.; Sherman, V.D.; Galkina, V.A.; Ginter, E.K.; Kutsev, S.I.; et al. Analysis of CFTR Mutation Spectrum in Ethnic Russian Cystic Fibrosis Patients. Genes (Basel). 2020,11(5), 554. [CrossRef]

- Sosnay, P.R.; Raraigh, K.S.; Gibson, R.L. Molecular Genetics of Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator: Genotype and Phenotype. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2016, 63(4), 585-98.

- Angelicheva, D.; Boteva, K.; Jordanova, A.; Savov, A.; Kufardjieva, A.; Tolun, A.; Telatar, M.; Akarsubaşi, A.; Köprübaşi, F.; Aydoğdu, S.; et al. Cystic fibrosis patients from the Black Sea region: the 1677delTA mutation. Hum Mutat. 1994, 3(4), 353-7. [CrossRef]

- Tkemaladze, T.; Kvaratskhelia, E.; Ghughunishvili, M.; Rtskhiladze, I.; Zaalishvili, Z.; Nakaidze, N.; Lentze, M.J.; Abzianidze, E.; Skrahina, V.; Rolfs, A. Additional evidence on the phenotype produced by combination of CFTR 1677delTA alleles and their relevance in causing CFTR-related disease. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2023, 11. 2050313X231177163. [CrossRef]

- Amato, F.; Bellia, C.; Cardillo, G.; Castaldo, G.; Ciaccio, M.; Elce, A.; Lembo, F.; Tomaiuolo, R. Extensive molecular analysis of patients bearing CFTR-related disorders. J Mol Diagn. 2012, 14(1), 81-9. [CrossRef]

- Cohn, J.A.; Friedman, K.J.; Noone, P.G.; Knowles, M.R.; Silverman, L.M.; Jowell, P.S. Relation between mutations of the cystic fibrosis gene and idiopathic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1998, 339(10), 653-8. [CrossRef]

- Genome Aggregation Database. Available on: https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/, (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Makukh, H.; Krenková, P.; Tyrkus, M.; Bober, L.; Hancárová, M.; Hnateyko, O.; Macek, M. Jr. A high frequency of the Cystic Fibrosis 2184insA mutation in Western Ukraine: genotype-phenotype correlations, relevance for newborn screening and genetic testing. J Cyst Fibros. 2010 , 9(5), 371-5.

- Dörk, T.; Mekus, F.; Schmidt, K.; Bosshammer, J.; Fislage, R.; Heuer, T.; Dziadek, V.; Neumann, T.; Kälin ,N.; Wulbrand, U.; et al. Detection of more than 50 different CFTR mutations in a large group of German cystic fibrosis patients. Hum Genet. 1994, 94(5), 533-42. [CrossRef]

- Stuhrmann, M.; Dörk, T.; Frühwirth, M.; Golla, A.; Skawran, B.; Antonin, W.; Ebhardt, M.; Loos, A.; Ellemunter, H.; Schmidtke, J. Detection of 100% of the CFTR mutations in 63 CF families from Tyrol. Clin Genet. 1997, 52(4), 240-6. [CrossRef]

- Ivady, G.; Madar, L.; Nagy, B.; Gonczi, F.; Ajzner, E.; Dzsudzsak, E.; Dvořáková, L.; Gombos, E.; Kappelmayer, J.; Macek, M.; et al. Distribution of CFTR mutations in Eastern Hungarians: relevance to genetic testing and to the introduction of newborn screening for cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2011, 10(3), 217-20. [CrossRef]

- Kolesar, P.; Minarik, G.; Baldovic, M.; Ficek, A.; Kovacs, L.; Kadasi, L. Mutation analysis of the CFTR gene in Slovak cystic fibrosis patients by DHPLC and subsequent sequencing: identification of four novel mutations. Gen Physiol Biophys 2008, 27, 299–305.

- Buratti, E.; Chivers, M.; Královicová, J.; Romano, M.; Baralle, M.; Krainer, A.R.; Vorechovsky, I. Aberrant 5’ splice sites in human disease genes: mutation pattern, nucleotide structure and comparison of computational tools that predict their utilization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35(13), 4250-63. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.Q. Statistical features of human exons and their flanking regions. Hum Mol Genet. 1998, 7(5), 919-32. [CrossRef]

- Terzic, M.; Jakimovska, M.; Fustik, S.; Jakovska, T.; Sukarova-Stefanovska, E.; Plaseska-Karanfilska D. Cystic Fibrosis Mutation Spectrum in North Macedonia: A Step Toward Personalized Therapy. Balkan J Med Genet. 2019, 22(1), 35-40. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.;,Wang .; Zhang, W.; Li, H.; Wang, B. Compound heterozygous mutations in CFTR causing CBAVD in Chinese pedigrees. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2018, 6(6), 1097-1103.

- Kilinç, M.O.; Ninis, V.N.; Dağli, E.; Demirkol, M.; Ozkinay, F.; Arikan, Z.; Coğulu, O.; Hüner, G.; Karakoç, F.; Tolun, A. Highest heterogeneity for cystic fibrosis: 36 mutations account for 75% of all CF chromosomes in Turkish patients. Am J Med Genet. 2002, 113(3), 250-7. [CrossRef]

- Akinsal, E.C.; Baydilli, N.; Dogan, M.E.; Ekmekcioglu, O. Comorbidity of the congenital absence of the vas deferens. Andrologia. 2018, 50, e12994. [CrossRef]

- Adler, A.I.; Shine, B.S.; Chamnan, P.; Haworth, C.S.; Bilton, D. Genetic determinants and epidemiology of cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: results from a British cohort of children and adults. Diabetes Care. 2008, 31(9),1789-94.

- Nowak, J.K.; Szczepanik, M.; Wojsyk-Banaszak, I.; Mądry, E.; Wykrętowicz, A.; Krzyżanowska-Jankowska, P.; Drzymała-Czyż, S; Nowicka, A.; Pogorzelski, A, Sapiejka E, et al. Cystic fibrosis dyslipidaemia: A cross-sectional study. J Cyst Fibros. 2019, 18(4), 566-571. [CrossRef]

- McCague, A.F.; Raraigh, K.S.; Pellicore, M.J.; Davis-Marcisak, E.F.; Evans, T.A.; Han, S.T.; Lu, Z.; Joynt, A.T.; Sharma, N.; Castellani, C.; et al. Correlating Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator Function with Clinical Features to Inform Precision Treatment of Cystic Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019, 199(9), 1116-1126. [CrossRef]

- Petrova, N.V.; Marakhonov, A.V.; Vasilyeva, T.A.; Kashirskaya, N.Y.; Ginter, E.K., Kutsev, S.I.; Zinchenko, R.A. Comprehensive genotyping reveals novel CFTR variants in cystic fibrosis patients from the Russian Federation. Clin Genet. 2019, 95(3), 444-447. [CrossRef]

- Claustres, M.; Thèze, C.; des Georges, M.; Baux, D.; Girodon, E.; Bienvenu, T.; Audrezet, M.P.; Dugueperoux, I.; Férec, C.; Lalau, G.; et al. CFTR-France, a national relational patient database for sharing genetic and phenotypic data associated with rare CFTR variants. Hum Mutat. 2017, 38(10), 1297-1315.

- Gaitch, N.; Hubert, D.; Gameiro, C.; Burgel, P.R.; Houriez, F., Martinez, B.; Honoré, I.; Chapron, J.; Kanaan, R.; Dusser, D.; et al. CFTR and/or pancreatitis susceptibility genes mutations as risk factors of pancreatitis in cystic fibrosis patients? Pancreatology. 2016, 16(4), 515-22. [CrossRef]

- Smits, R.M.; Oud, M.S.; Vissers L.E.L.M.; Lugtenberg, D.; Braat, D.D.M.; Fleischer, K.; Ramos, L.; D’Hauwers, K.W.M. Improved detection of CFTR variants by targeted next-generation sequencing in male infertility: a case series. Reprod Biomed Online. 2019, 39(6), 963-968. [CrossRef]

- Kerem, B.S.; Zielenski, J.; Markiewicz, D.; Bozon, D.; Gazit, E.; Yahav, J.; Kennedy, D.; Riordan, J.R.; Collins, F.S.; Rommens, J.M.; et al. Identification of mutations in regions corresponding to the two putative nucleotide (ATP)-binding folds of the cystic fibrosis gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990, 7(21):8447-51. [CrossRef]

- Hull, J.; Shackleton, S.; Harris, A. Abnormal mRNA splicing resulting from three different mutations in the CFTR gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1993, 2(6), 689-92. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Sosnay, P.R.; Ramalho, A.S.; Douville, C.; Franca, A.; Gottschalk, L.B.; Park, J.; Lee, M.; Vecchio-Pagan, B.; Raraigh, K.S.; et al. Experimental assessment of splicing variants using expression minigenes and comparison with in silico predictions. Hum Mutat. 2014, 35(10), 1249-59. [CrossRef]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015, 17(5), 405-24. [CrossRef]

- Shelton, C.; LaRusch, J.; Whitcomb, D.C. Pancreatitis Overview. 2014 Mar 13 [updated 2020 Jul 2]. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK190101/, (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Sosnay, P.R.; Siklosi, K.R.; Van Goor, F.; Kaniecki, K.; Yu, H.; Sharma, N.; Ramalho, A.S.; Amaral, M.D.; Dorfman, R.; Zielenski, J.; et al. Defining the disease liability of variants in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene. Nat Genet. 2013, 45(10), 1160-7. [CrossRef]

- Kanavakis, E.; Efthymiadou, A.; Strofalis, S.; Doudounakis, S.; Traeger-Synodinos, J.; Tzetis, M. Cystic fibrosis in Greece: molecular diagnosis, haplotypes, prenatal diagnosis and carrier identification amongst high-risk individuals. Clin Genet. 2003, 63(5), 400-9.

- Cohn, J.A.; Friedman, K.J.; Noone, P.G.; Knowles, M.R.; Silverman, L.M.; Jowell, P.S. Relation between mutations of the cystic fibrosis gene and idiopathic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1998, 339(10), 653-8. [CrossRef]

| Allele1 | Allele 2 | No of cases |

|---|---|---|

| F508del | F508del | 22 |

| F508del | 621 +1G>T (c.489+1 G>T) | 3 |

| F508del | G542X | 3 |

| F508del | 1677delTA | 3 |

| G542X | 185+1G->T (c.53+1G>T) | 3 |

| F508del | 2184insA (c.2052dup) (p.Gln685fs ) (Q685fs) | 2 |

| F508del | c.917dupA p.(Asn306Lysfs*2) | 2 |

| F508del | c.3849G->A (c.3717G>A) (p.Arg1239=) | 2 |

| F508del | R1158X | 1 |

| F508del | K598*(c.1792A>T ) (p.Lys598Ter) | 1 |

| F508del | c.1040G>A (p.Arg347His) (R347H) | 1 |

| F508del | c.54-5940_273+10250del (CFTRdele2,3 (21kb) | 1 |

| F508del | 1717-1G>A | 1 |

| F508del | c2589_2599delAATTTGGTGCT c.2589_2599del (p.Ile864fs)(I864fs) |

1 |

| F508del | c.1487G>A, p.(Trp496Ter) | 1 |

| F508del | c.(53+1_54-1)_(164+1_165-1)del (CFTRdele2) | 1 |

| CFTR variant | No. allele (%)(our study) | Frentescu et al. [24](Romania) | Sciucaet al. [25](Rep. Moldova) | Kasmi et al. [26](Albania) | Petrova et al. [27](Bulgaria | Křenková et al.[28]Czech Rep.) | Ruenda -Nieto et al. [7](Spain) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F508del | 67 (69.79%) | 144 (56.3%) |

79 (57.4%) | 203 (83.19%) | 154 (55%) | 809 (67.42%) | 142 (37.0%) |

| G542X | 6 (6.25%) | 10 (3.9%) | 4 ( 3.3%) | 4(1.63%) | 11 (3.93%) | 24 (2%) | 31 (8.1%) |

| 621 +1G>T (c.489+1G>T) | 3 (3.12%) | 2 ( 0.8%) |

1 (0.8%) | 6(2.45%) | 4 (1.43%) | 5 (0.43%) | 1 (0.3%) |

| 1677delTA | 3 (3.12%) | 1 (0.4%) | 1 (0.8%) | - | 3 (1.07%) | - | - |

| 185+1G ->T (c.53+1G>T) | 3 (3.12%) | - | 1 (0.8%) | - | - | 2 (0.17%) | - |

| 2184insA | 2 (2.08%) | - | 4 ( 3.3%) | - | 8 (2.89%) | 5 (0.42%) | - |

| c.917dupA p.(Asn306Lysfs*2) | 2 (2.08%) | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 3849G>A (c.3717G>A) (p.Arg1239=) |

2 (2.08%) | - | 2 ( 1.6%) | - | - | - | 1 (0.3%) |

| R1158X (c.3472C>T) | 1 (1.04%) | - | - | 1(0.40%) | 1 (0.36%) | 1 (0.08) | 1 (0.3%) |

| K598* (c.1792A>T ) (p.Lys598Ter) | 1 (1.04 %) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| R347H (c.1040G>A) | 1 (1.04%) | - | - | - | - | 1 (0.08%) | - |

| c.54-5940_273+10250del (CFTRdele2,3 (21kb) |

1 (1.04%) | 4 (1.6%) | 2 ( 1.6%) | 1(0.40%) | 2 (0.71) | 69 (5.75%) | - |

| 1717-1G>A (c.1585-2A>T) | 1 (1.04%) | 1 (0.4%) | - | - | - | 4 (0.33) | 1 (0.3%) |

| c2589_2599delAATTTGGTGCT c.2589_2599del (p.Ile864fs) |

1 (1.04%) | - | - | - | - | 1 (0.08) | - |

| R496H (c.1487G>A) p.(Trp496Ter) | 1 (1.04%) | - | - | - | - | - | |

| c.(53+1_54-1)_(164+1_165-1)del (CFTRdele2) | 1 (1.04%) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| No total allele | 96 | 256 | 122 | 244 | 277 | 1200 | 384 |

| Criteria | Homozygous no. (%) | Compound Heterozygous no. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 12 / 22 (54.5%) | 12 /26 (46.15%) |

| Male | 10 / 22 (45.5%) | 14 /26 (53.84%) |

| Respiratory Manifestations | ||

| Bronchiectasis | 5 /22 (22.72%) | 9 /26 (34.61%) |

| R-URTIs a | 10 /22 (45.45%) | 13 /26 (50%) |

|

Gastrointestinal and nutritional manifestations |

||

| Hepatocytolysis | 14 /22 (63.63%) | 18 /26 (69.23%) |

| Biliary cirrhosis | 3 /22 (13.63%) | 2 /26 (7.69%) |

| Liver fibrosis | 1 /22 (4.54%) | - |

| Gallbladder stones | 2 /22 (9.09%) | 1 /26 (3.84%) |

| EPIb | 22/22 (100%) | 19/26 (73.07%) |

| CF-related pancreatitis | 1/22 (4.54%) | - |

| CF-Related GI manifestations | - | 1 /26 (3.84%) |

| Growth Failure | 19/22 (86.36%) | 26/26 (100%) |

| Metabolic manifestations | ||

| Dyslipidemia | 2 /22 (9.09%) | 3 /26 (11.53%) |

| Hepatic steatosis | 5 /22 (22.72%) | 6 /26 (23.07%) |

| CFRD | 3 /22 (13.63%) | 3 /26 (11.53%) |

| 25-OH Vitamin D Deficiency | 13/22 (59.09%) | 14 /26 (53.84%) |

| Surgical manifestations | ||

| Meconium ileus | 6 /22 (27.27%) | 3 /26 (11.53%) |

| Subocclusive syndrome | 2 /22 (9.09%) | 1 /26 (3.84%) |

| Rectal prolapse | 2 /22 (9.09%) | 4 /26 (15.38%) |

| Renal and urological manifestations | ||

| Urolithiasis | - | 1 /26(3.84%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).