Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Structure, Function, Diversity, and the Scale of Cells

Scaling Patterns in Cells

Models That Predict Scaling Patterns in Cells

Challenges and Implications

Concluding Remarks

Acknowledgments

References

- Schwann, T.H. Microscopial Researches into the Accordance in the Structure and Growth of Animals and Plants. Obesity Research 1847, 1, 408–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzarello, P. A unifying concept: the history of cell theory. Nature Cell Biology 1999, 1, E13–E15.

- Piras, V.; Tomita, M.; Selvarajoo, K. Is central dogma a global property of cellular information flow? Frontiers in Physiology 2012, 3, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crick, F. What mad pursuit; Basic Books, 2008.

- Volland, J.M.; Gonzalez-Rizzo, S.; Gros, O.; Tyml, T.; Ivanova, N.; Schulz, F.; Goudeau, D.; Elisabeth, N.H.; Nath, N.; Udwary, D.; et al. A centimeter-long bacterium with DNA contained in metabolically active, membrane-bound organelles. Science 2022, 376, 1453–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islas-Morales, P.F.; Cárdenas, A.; Mosqueira Santillán, M.J.; Jiménez-García, L.F.; Voolstra, C.R. Ultrastructural and proteomic evidence for the presence of a putative nucleolus in an Archaeon 2023.

- Hutchison III, C.A.; Chuang, R.Y.; Noskov, V.N.; Assad-Garcia, N.; Deerinck, T.J.; Ellisman, M.H.; Gill, J.; Kannan, K.; Karas, B.J.; Ma, L.; et al. Design and synthesis of a minimal bacterial genome. Science 2016, 351, aad6253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolgemuth, C.W. Does cell biology need physicists? Physics 2011, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J. Quantitative cell biology: the essential role of theory. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2014, 25, 3438–3440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Gaitan, M.; Roux, A. When cell biology meets theory. The Journal of Cell Biology 2015, 210, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, R. Theory in biology: Figure 1 or Figure 7? Trends in cell biology 2015, 25, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalewski, J. Mathematical Models in Cellular Biophysics. PhD thesis, KTH, 2007.

- Arrhenius, S. Über die Reaktionsgeschwindigkeit bei der Inversion von Rohrzucker durch Säuren. Zeitschrift für physikalische Chemie 1889, 4, 226–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyring, H. The activated complex in chemical reactions. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1935, 3, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiber, M. Body size and metabolic rate. Physiological reviews 1947, 27, 511–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, G.B.; Brown, J.H.; Enquist, B.J. A general model for the origin of allometric scaling laws in biology. Science 1997, 276, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquet, P.A.; Allen, A.P.; Brown, J.H.; Dunne, J.A.; Enquist, B.J.; Gillooly, J.F.; Gowaty, P.A.; Green, J.L.; Harte, J.; Hubbell, S.P.; et al. On theory in ecology. BioScience 2014, 64, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; He, H.L.; Church, G.M. Modeling gene expression with differential equations. In Biocomputing’99; World Scientific, 1999; pp. 29–40.

- Michaelis, L.; Menten, M.L.; et al. Die kinetik der invertinwirkung. Biochem. z 1913, 49, 352. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, H.N.; Jørgensen, B.B. Big bacteria. Annual Reviews in Microbiology 2001, 55, 105–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, P.A.; Angert, E.R. Small but mighty: cell size and bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology 2015, 7, a019216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jr., J.P. Bacterial Metabolism. Medical Microbiology. 4th edition. 1996, p. Chapter 4.

- Agrawal, A.; Scott, Z.C.; Koslover, E.F. Morphology and transport in eukaryotic cells. Annual Review of Biophysics 2022, 51, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mignot, T.; Shaevitz, J.W. Active and passive mechanisms of intracellular transport and localization in bacteria. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2008, 11, 580–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allemand, J.F.; Maier, B.; Smith, D.E. Molecular motors for DNA translocation in prokaryotes. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2012, 23, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelezniak, A.; Andrejev, S.; Ponomarova, O.; Mende, D.R.; Bork, P.; Patil, K.R. Metabolic dependencies drive species co-occurrence in diverse microbial communities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 6449–6454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mizuno, K.; Maree, M.; Nagamura, T.; Koga, A.; Hirayama, S.; Furukawa, S.; Tanaka, K.; Morikawa, K. Novel multicellular prokaryote discovered next to an underground stream. Elife 2022, 11, e71920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Cano, D.J.; Reyes-Prieto, M.; Martínez-Romero, E.; Partida-Martínez, L.P.; Latorre, A.; Moya, A.; Delaye, L. Evolution of small prokaryotic genomes. Frontiers in Microbiology 2015, 5, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waites, K.B.; Talkington, D.F. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and its role as a human pathogen. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2004, 17, 697–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobay, L.M.; Ochman, H. The Evolution of Bacterial Genome Architecture. Frontiers in Genetics 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, R.M.; Rappé, M.S.; Connon, S.A.; Vergin, K.L.; Siebold, W.A.; Carlson, C.A.; Giovannoni, S.J. SAR11 clade dominates ocean surface bacterioplankton communities. Nature 2002, 420, 806–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rappé, M.S.; Connon, S.A.; Vergin, K.L.; Giovannoni, S.J. Cultivation of the ubiquitous SAR11 marine bacterioplankton clade. Nature 2002, 418, 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Schwartz, C.L.; Pierson, J.; Giovannoni, S.J.; McIntosh, J.R.; Nicastro, D. Three-Dimensional Structure of the Ultraoligotrophic Marine Bacterium “Candidatus Pelagibacter ubique”. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2017, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courties, C.; Vaquer, A.; Troussellier, M.; Lautier, J.; Chrétiennot-Dinet, M.J.; Neveux, J.; Machado, C.; Claustre, H. Smallest eukaryotic organism. Nature 1994, 370, 255–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, A.M.; Gestinari, L.M.d.S.; Moura, C.W.d.N. The family Valoniaceae (Chlorophyta) in the state of Bahia, Brazil: Morphological aspects and geographical distribution. Hidrobiológica 2010, 20, 171–184. [Google Scholar]

- Meinesz, A.; Hesse, B. Introduction of the tropical alga Caulerpa taxifolia and its invasion of the northwestern Mediterranean. Oceanologica acta. Paris 1991, 14, 415–426. [Google Scholar]

- Young, K.D. The selective value of bacterial shape. Microbiology and molecular biology reviews 2006, 70, 660–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLong, J.P.; Okie, J.G.; Moses, M.E.; Sibly, R.M.; Brown, J.H. Shifts in metabolic scaling, production, and efficiency across major evolutionary transitions of life. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 12941–12945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.H.; West, G.B. Scaling in biology; Oxford University Press on Demand, 2000.

- West, G.B.; Brown, J.; Enquist, B. Scaling in biology: patterns and processes, causes and consequences. Scaling in biology 2000, 87, 112. [Google Scholar]

- Rau, A. Biological scaling and physics. Journal of Biosciences 2002, 27, 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, A.J. Scaling in biology. Current Biology 2009, 19, R57–R61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A. Scaling laws. Mechanics Over Micro and Nano Scales 2011, pp. 61–94.

- West, G.B.; Brown, J.H. The origin of allometric scaling laws in biology from genomes to ecosystems: towards a quantitative unifying theory of biological structure and organization. Journal of Experimental Biology 2005, 208, 1575–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitfield, J. In the Beat of a Heart: Life, Energy, and the Unity of Nature; Washington, DC: Joseph Henry Press, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, F.L.; Pereira, W.R. A Gentle Introduction to Scaling Laws in Biological Systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.01540, arXiv:2105.01540 2021.

- Yang, V.C.; Holehouse, J.; Kempes, C.P.; Hyejin, Y.; Arroyo, J.I.; Redner, S.; West, G.B. Scaling Laws for Function Diversity and Specialization Across Socioeconomic and Biological Complex Systems. 2022; https://arxiv.org/abs/2208.06487v2. [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldo, A.; Rigon, R.; Banavar, J.R.; Maritan, A.; Rodriguez-Iturbe, I. Evolution and selection of river networks: Statics, dynamics, and complexity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 2417–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okie, J.G. General models for the spectra of surface area scaling strategies of cells and organisms: fractality, geometric dissimilitude, and internalization. The American Naturalist 2013, 181, 421–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaechter, M.; Maaløe, O.; Kjeldgaard, N.O. Dependency on medium and temperature of cell size and chemical composition during balanced growth of Salmonella typhimurium. Microbiology 1958, 19, 592–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donachie, W.D. Relationship between cell size and time of initiation of DNA replication. Nature 1968, 219, 1077–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakrishnan, R.; Mori, M.; Segota, I.; Zhang, Z.; Aebersold, R.; Ludwig, C.; Hwa, T. Principles of gene regulation quantitatively connect DNA to RNA and proteins in bacteria. Science 2022, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basan, M.; Zhu, M.; Dai, X.; Warren, M.; Sévin, D.; Wang, Y.P.; Hwa, T. Inflating bacterial cells by increased protein synthesis. Molecular Systems Biology 2015, 11, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafelski, S.M.; Viana, M.P.; Zhang, Y.; Chan, Y.H.M.; Thorn, K.S.; Yam, P.; Fung, J.C.; Li, H.; Costa, L.d.F.; Marshall, W.F. Mitochondrial network size scaling in budding yeast. Science 2012, 338, 822–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempes, C.P.; Wang, L.; Amend, J.P.; Doyle, J.; Hoehler, T. Evolutionary tradeoffs in cellular composition across diverse bacteria. The ISME Journal 2016, 10, 2145–2157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loferer-Krossbacher, M.; Klima, J.; Psenner, R. Determination of bacterial cell dry mass by transmission electron microscopy and densitometric image analysis. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1998, 64, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojkic, N.; Serbanescu, D.; Banerjee, S. Surface-to-volume scaling and aspect ratio preservation in rod-shaped bacteria. Elife 2019, 8, e47033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignatiades, L. Size scaling patterns of species richness and carbon biomass for marine phytoplankton functional groups. Marine Ecology 2017, 38, e12454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkel, Z.; Follows, M.; Irwin, A. Size-scaling of macromolecules and chemical energy content in the eukaryotic microalgae. Journal of Plankton Research 2016, 38, 1151–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cael, B.; Cavan, E.L.; Britten, G.L. Reconciling the size-dependence of marine particle sinking speed. Geophysical Research Letters 2021, 48, e2020GL091771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.; Trickovic, B.; Kempes, C.P. Evolutionary scaling of maximum growth rate with organism size. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 22586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dao, M.H. Reassessment of the cell surface area limitation to nutrient uptake in phytoplankton. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2013, 489, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, W.T.; Govers, S.K.; Xiang, Y.; Parry, B.R.; Campos, M.; Kim, S.; Jacobs-Wagner, C. Nucleoid size scaling and intracellular organization of translation across bacteria. Cell 2019, 177, 1632–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niklas, K.J.; Hammond, S.T. Biophysical effects on the scaling of plant growth, form, and ecology. Integrative and Comparative Biology 2019, 59, 1312–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

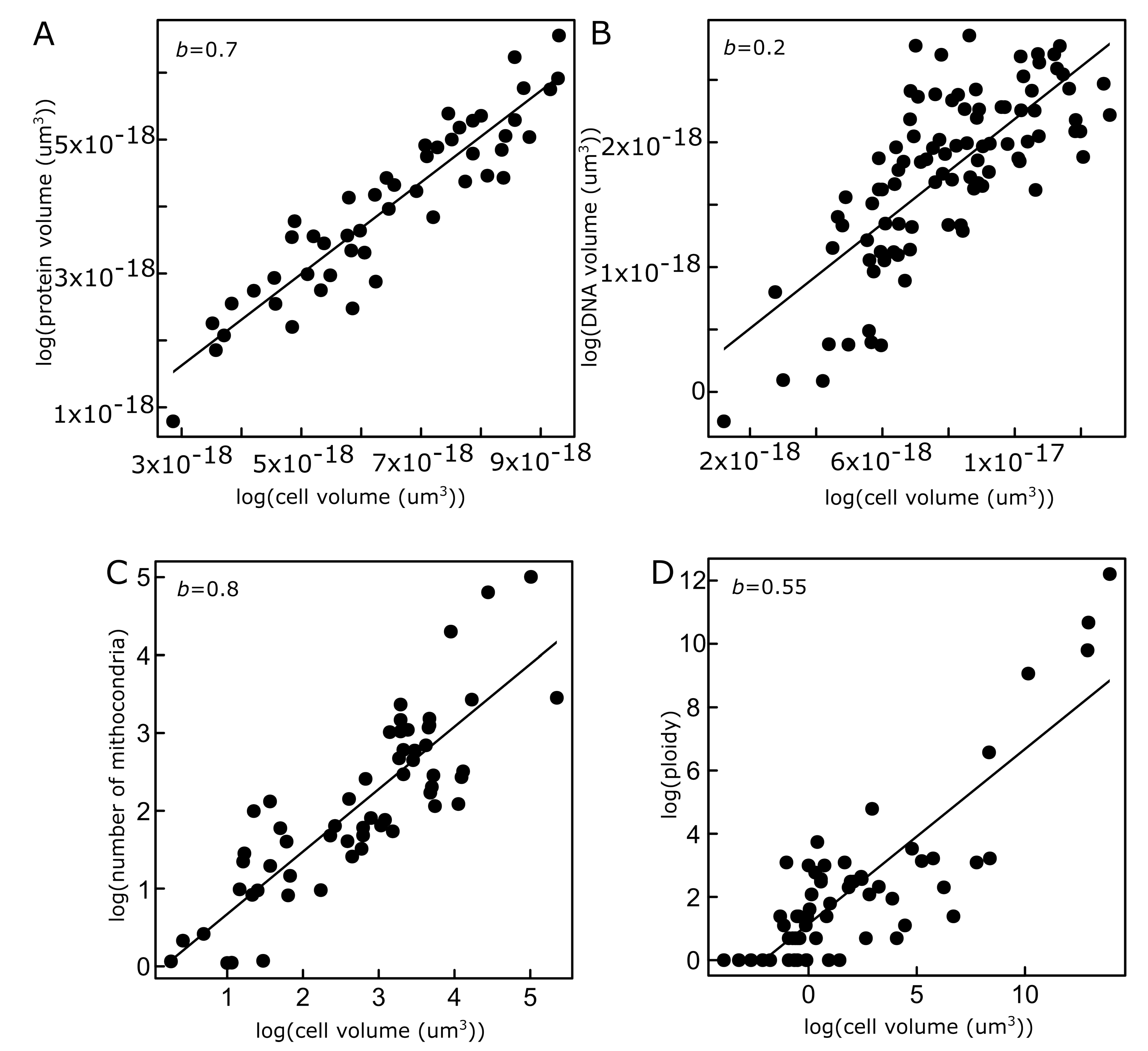

- Okie, J.G.; Smith, V.H.; Martin-Cereceda, M. Major evolutionary transitions of life, metabolic scaling and the number and size of mitochondria and chloroplasts. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2016, 283, 20160611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-de Salceda, L.; Garcia-Pichel, F. The allometry of cellular DNA and ribosomal gene content among microbes and its use for the assessment of microbiome community structure. Microbiome 2021, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynch, M.; Marinov, G.K. Membranes, energetics, and evolution across the prokaryote-eukaryote divide. elife 2017, 6, e20437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillooly, J.F.; Brown, J.H.; West, G.B.; Savage, V.M.; Charnov, E.L. Effects of size and temperature on metabolic rate. science 2001, 293, 2248–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, P.B.; Sowers, T. Temperature dependence of metabolic rates for microbial growth, maintenance, and survival. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2004, 101, 4631–4636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R, M. What is the total number of protein molecules per cell volume? A call to rethink some published values. Bioessays 2013, 35, 1050–5. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Y.H.M.; Marshall, W.F. Scaling properties of cell and organelle size. Organogenesis 2010, 6, 88–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, G.B.; Brown, J.H.; Enquist, B.J. The Fourth Dimension of Life: Fractal Geometry and Allometric Scaling of Organisms. Science 1999, 284, 1677–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertaux, F.; Von Kügelgen, J.; Marguerat, S.; Shahrezaei, V. A bacterial size law revealed by a coarse-grained model of cell physiology. PLoS Computational Biology 2020, 16, e1008245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, M.; Gunderson, C.W.; Mateescu, E.M.; Zhang, Z.; Hwa, T. Interdependence of cell growth and gene expression: origins and consequences. Science 2010, 330, 1099–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, M.; Klumpp, S.; Mateescu, E.M.; Hwa, T. Emergence of robust growth laws from optimal regulation of ribosome synthesis. Molecular Systems Biology 2014, 10, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollin, R.; Joanny, J.F.; Sens, P. Physical basis of the cell size scaling laws. Elife 2023, 12, e82490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krakauer, D.C.; Collins, J.P.; Erwin, D.; Flack, J.C.; Fontana, W.; Laubichler, M.D.; Prohaska, S.J.; West, G.B.; Stadler, P.F. The challenges and scope of theoretical biology. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2011, 276, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barabási, A.L.; Albert, R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science 1999, 286, 509–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, G.B.; Brown, J.H.; Enquist, B.J. A general model for ontogenetic growth. Nature 2001, 413, 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo, J.I.; Díez, B.; Kempes, C.P.; West, G.B.; Marquet, P.A. A general theory for temperature dependence in biology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119, e2119872119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Si, F.; Li, D.; Cox, S.E.; Sauls, J.T.; Azizi, O.; Sou, C.; Schwartz, A.B.; Erickstad, M.J.; Jun, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Invariance of initiation mass and predictability of cell size in Escherichia coli. Current Biology 2017, 27, 1278–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Nimwegen, E. Scaling laws in the functional content of genomes. Trends in Genetics 2003, 19, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chignola, R.; Sega, M.; Stella, S.; Vyshemirsky, V.; Milotti, E. From single-cell dynamics to scaling laws in oncology. Biophysical Reviews and Letters 2014, 9, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, V.C.; Kempes, C.P.; Redner, S.; Arroyo, J.I.; West, G.B.; Youn, H. How much regulation do we need from genomes to society? arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.02884v2 2025.

- Rothschild, L.J.; Averesch, N.J.; Strychalski, E.A.; Moser, F.; Glass, J.I.; Cruz Perez, R.; Yekinni, I.O.; Rothschild-Mancinelli, B.; Roberts Kingman, G.A.; Wu, F.; et al. Building synthetic cells-from the technology infrastructure to cellular entities. ACS Synthetic Biology 2024, 13, 974–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo, J.I.; Kempes, C. An algorithm for predicting per-cell proteomic properties. bioRxiv 2024, pp. 2024–12.

- Lynch, M.; Marinov, G.K. The bioenergetic costs of a gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 15690–15695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Rel. | Type | Exponent | Taxa | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic rate (W) vs. cell size (g) | Rate-Size | 1.96 | Prok. | [38] |

| Amount of RNA vs. cell growth rate | Comp.-Rate | NC | Prok. | [52] |

| Genome size (bp) vs. cell mass (g) | Comp.-Size | 0.24 | Prok. | [44] |

| Proteome size () vs. cell vol. () | Comp.-Size | 0.7 | Bac. | [55] |

| Ribosomes vol. () vs. cell vol. () | Comp.-Size | 0.73 | Bac. | [55] |

| DNA vs. RNA | Comp.-Comp. | NC | Prok. | [52] |

| Dry weight (fg) vs. volume () | Size-Size | 0.86 | Bac. | [56] |

| (Surface) area () vs. volume () | Size-Size | 0.66/0.66 | Bac. | [57] |

| Carbon content () vs. volume () | Comp.-Size | 0.93 | Euk. | [58] |

| Carbon content () vs. volume () | Comp.-Size | 0.78 | Euk. | [59] |

| Dry weight () vs. volume () | Size-Size | 0.82 | Euk. | [59] |

| Protein () vs. volume () | Comp.-Size | 0.83 | Euk. | [59] |

| Lipid () vs. volume () | Comp.-Size | 0.8 | Euk. | [59] |

| Carbohydrate () vs. volume () | Comp.-Size | 0.93 | Euk. | [59] |

| Chemical energy () vs. volume () | Comp.-Size | 0.83 | Euk. | [59] |

| Sinking speed (m/d) vs. diameter (mm) | Rate-Size | 0.63 | Euk. | [60] |

| Max. growth rate vs. cell mass | Rate-Size | -0.025 | Prok. | [61] |

| Max. growth rate vs. cell mass | Rate-Size | 0.292 | Prok. | [38] |

| Max. growth rate vs. cell mass | Rate-Size | -0.112 | Unicel. Euk. | [38] |

| Carbon production rate vs. cell volume | Rate-Size | 0.88 | Unicel. Euk. | [62] |

| Avg. swimming speed vs. cell volume | Rate-Size | 0.3 | Unicel. Euk. | [61] |

| Sp. Avg.nucleoid area vs. average cell SA | Size-Size | 0.6 | Prok., Euk. | [63] |

| Surface area vs. cell volume | Size-Size | 0.71 | Prok., Euk. | [64] |

| Carbon content (mass) vs. cell volume | Comp.-Size | 0.84 | Prok., Euk. | [64] |

| DNA content vs. cell volume | Comp.-Size | 0.74 | Mul. Euk | [64] |

| Total mitoc. volume vs. cell volume | Comp.-Size | 1.01 | Euk. | [65] |

| N. of 16/18S ribos.gene vs. cell volume | Comp.-Size | 0.66 | Prok., Euk. | [66] |

| N. of ATP synthase complexes vs. cell SA | Comp.-Size | 1.26 | Prok., Euk. | [67] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).