Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Evaluation of Olfactory Sensitivity

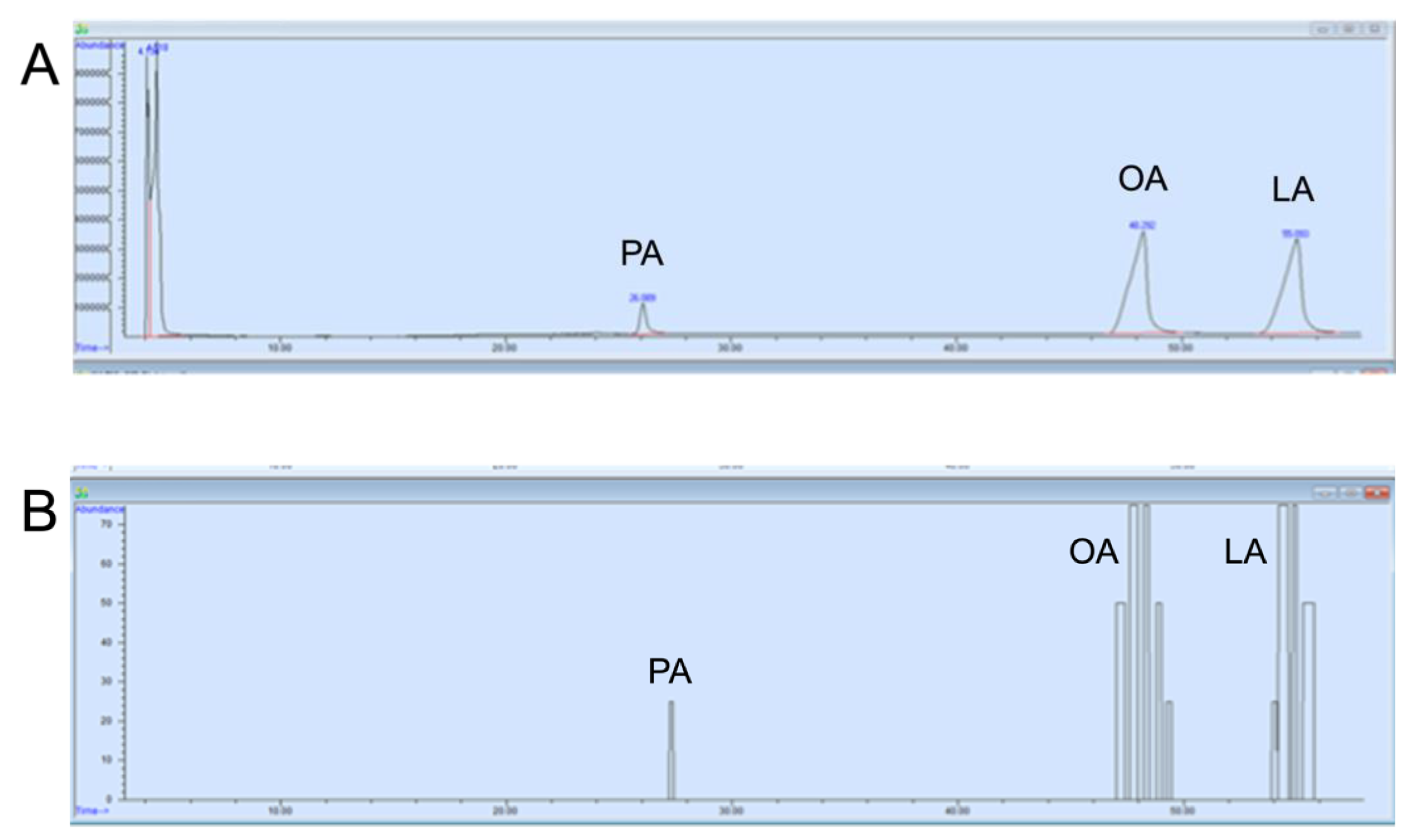

2.3. Mass Spectrometry-Gas Chromatography-Olfactometry (MS-GC-O) Technique

2.4. Determination of the Olfactory Threshold to Fatty Acids

2.5. Statistical Analysis

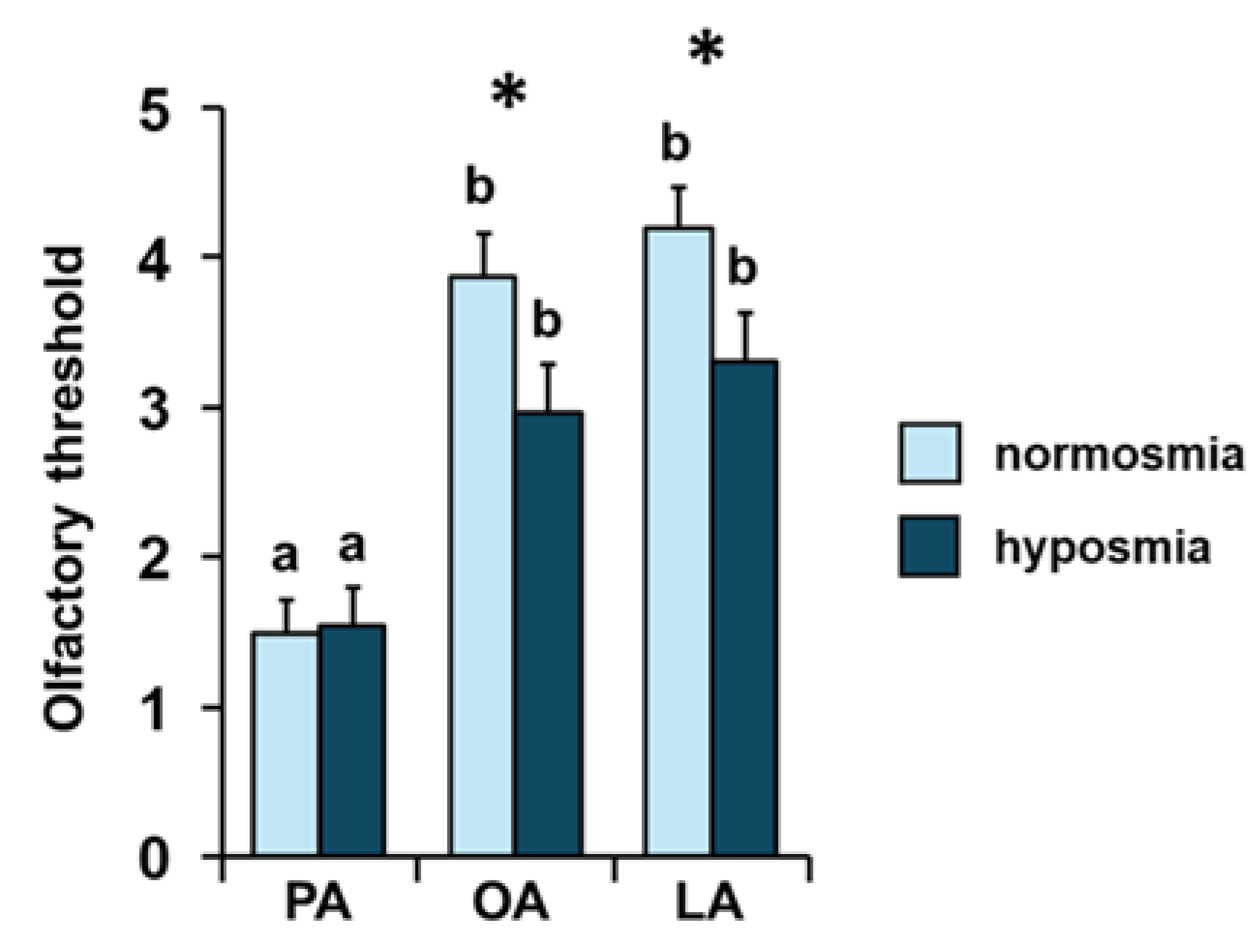

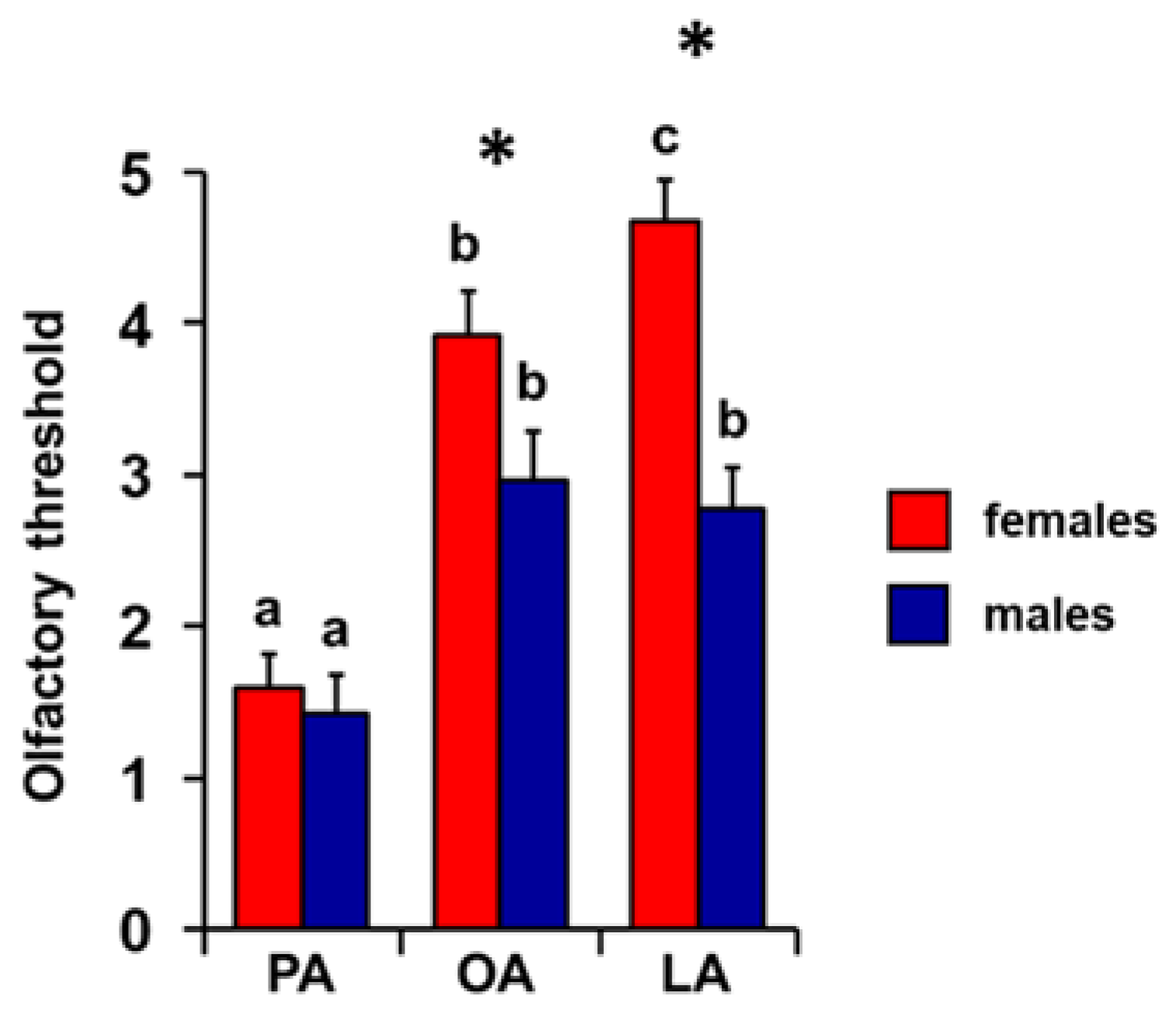

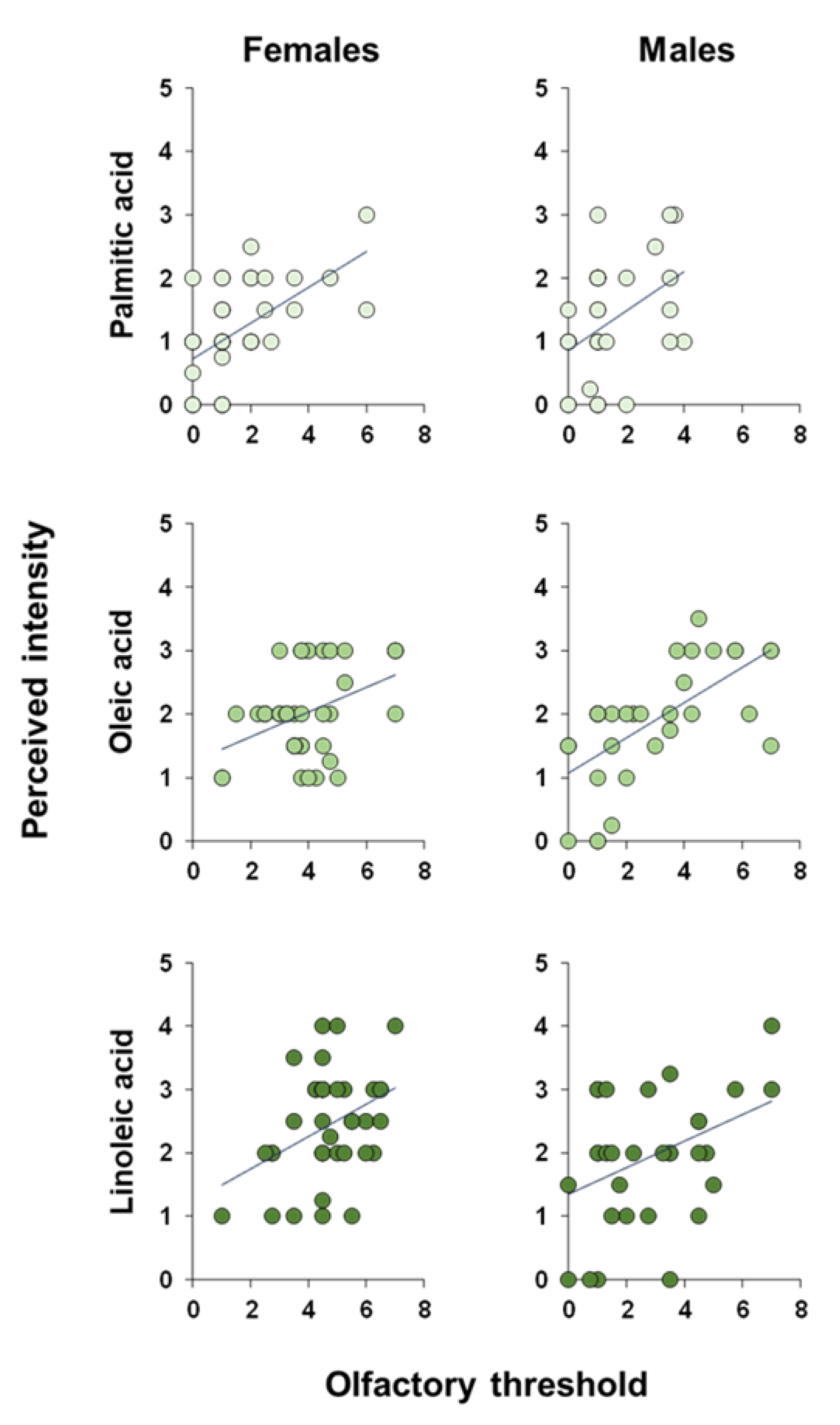

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lobb, K.; Chow, C. Fatty Acid Classification and Nomenclature. 2007; pp. 1-15.

- Bolton, B.; Halpern, B.P. Orthonasal and retronasal but not oral-cavity-only discrimination of vapor-phase fatty acids. Chem Senses 2010, 35, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, C.K. Fatty acids in foods and their health implications, third edition; 2007; pp. 1-1283.

- Bazinet, R.P.; Layé, S. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their metabolites in brain function and disease. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2014, 15, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calder, P.C. Functional Roles of Fatty Acids and Their Effects on Human Health. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 2015, 39, 18S–32S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyall, S.C.; Balas, L.; Bazan, N.G.; Brenna, J.T.; Chiang, N.; da Costa Souza, F.; Dalli, J.; Durand, T.; Galano, J.-M.; Lein, P.J.; et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and fatty acid-derived lipid mediators: Recent advances in the understanding of their biosynthesis, structures, and functions. Progress in Lipid Research 2022, 86, 101165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harayama, T.; Shimizu, T. Roles of polyunsaturated fatty acids, from mediators to membranes. Journal of Lipid Research 2020, 61, 1150–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, B.; Kapoor, D.; Gautam, S.; Singh, R.; Bhardwaj, S. Dietary Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids (PUFAs): Uses and Potential Health Benefits. Current Nutrition Reports 2021, 10, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mititelu, M.; Lupuliasa, D.; Neacșu, S.M.; Olteanu, G.; Busnatu, Ș.S.; Mihai, A.; Popovici, V.; Măru, N.; Boroghină, S.C.; Mihai, S.; et al. Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Human Health: A Key to Modern Nutritional Balance in Association with Polyphenolic Compounds from Food Sources. Foods 2025, 14, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sioen, I.; van Lieshout, L.; Eilander, A.; Fleith, M.; Lohner, S.; Szommer, A.; Petisca, C.; Eussen, S.; Forsyth, S.; Calder, P.C.; et al. Systematic Review on N-3 and N-6 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Intake in European Countries in Light of the Current Recommendations - Focus on Specific Population Groups. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 2017, 70, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinze, J.M.; Costanzo, A.; Baselier, I.; Fritsche, A.; Lidolt, M.; Hinrichs, J.; Frank-Podlech, S.; Keast, R. Oil Perception-Detection Thresholds for Varying Fatty Stimuli and Inter-individual Differences. Chem Senses 2017, 42, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, X.; Yeo, P.L.Q.; Loo, Y.T.; Henry, C.J. Associations between circulating fatty acid levels and metabolic risk factors. Journal of Nutrition & Intermediary Metabolism 2019, 15, 65–69. [Google Scholar]

- Boden, G. Obesity and Free Fatty Acids. Endocrinology and metabolism clinics of North America 2008, 37, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerab, D.; Blangero, F.; da Costa, P.C.T.; de Brito Alves, J.L.; Kefi, R.; Jamoussi, H.; Morio, B.; Eljaafari, A. Beneficial Effects of Omega-3 Fatty Acids on Obesity and Related Metabolic and Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorente-Cebrián, S.; Costa, A.G.; Navas-Carretero, S.; Zabala, M.; Martínez, J.A.; Moreno-Aliaga, M.J. Role of omega-3 fatty acids in obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular diseases: a review of the evidence. J Physiol Biochem 2013, 69, 633–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravaut, G.; Légiot, A.; Bergeron, K.-F.; Mounier, C. Monounsaturated Fatty Acids in Obesity-Related Inflammation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subošić, B.; Kotur-Stevuljević, J.; Bogavac-Stanojević, N.; Zdravković, V.; Ješić, M.; Kovačević, S.; Đuričić, I. Circulating Fatty Acids Associate with Metabolic Changes in Adolescents Living with Obesity. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrzosek, M.; Zawadzka, Z.; Sawicka, A.; Bobrowska-Korczak, B.; Białek, A. Impact of Fatty Acids on Obesity-Associated Diseases and Radical Weight Reduction. Obesity surgery 2022, 32, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesveldt, S.; de Graaf, K. The Differential Role of Smell and Taste For Eating Behavior. Perception 2017, 46, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesveldt, S.; Parma, V. The importance of the olfactory system in human well-being, through nutrition and social behavior. Cell and tissue research 2021, 383, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollai, G.; Crnjar, R. Age-Related Olfactory Decline Is Associated With Levels of Exercise and Non-exercise Physical Activities. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2021, 13, 695115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, R.J. An initial evaluation of the functions of human olfaction. Chem Senses 2010, 35, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velluzzi, F.; Deledda, A.; Lombardo, M.; Fosci, M.; Crnjar, R.; Grossi, E.; Sollai, G. Application of Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) to Elucidate the Connections among Smell, Obesity with Related Metabolic Alterations, and Eating Habit in Patients with Weight Excess. Metabolites 2023, 13, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aschenbrenner, K.; Hummel, C.; Teszmer, K.; Krone, F.; Ishimaru, T.; Seo, H.S.; Hummel, T. The influence of olfactory loss on dietary behaviors. The Laryngoscope 2008, 118, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, V.B.; Backstrand, J.R.; Ferris, A.M. Olfactory dysfunction and related nutritional risk in free-living, elderly women. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 1995, 95, 879–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazzino, T.L.; Rohde, K.; Sullivan, D.K. Hyper-Palatable Foods: Development of a Quantitative Definition and Application to the US Food System Database. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.) 2019, 27, 1761–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henkin, R.I. Effects of smell loss (hyposmia) on salt usage. Nutrition 2014, 30, 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattes, R.D. Nutritional implications of the cephalic-phase salivary response. Appetite 2000, 34, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, E.; Graaf, C.; Boesveldt, S. Food preferences and intake in a population of Dutch individuals with self-reported smell loss: An online survey. Food Quality and Preference 2019, 79, 103771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boesveldt, S.; Lundström, J.N. Detecting fat content of food from a distance: olfactory-based fat discrimination in humans. PloS one 2014, 9, e85977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewnowski, A. Why do we like fat? Journal of the American Dietetic Association 1997, 97, S58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalanza, J.F.; Snoeren, E.M.S. The cafeteria diet: A standardized protocol and its effects on behavior. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 2021, 122, 92–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, D.S.; Aronne, L.J.; Astrup, A.; de Cabo, R.; Cantley, L.C.; Friedman, M.I.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Johnson, J.D.; King, J.C.; Krauss, R.M.; et al. The carbohydrate-insulin model: a physiological perspective on the obesity pandemic. The American journal of clinical nutrition 2021, 114, 1873–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Montero, C.; Fraile-Martínez, O.; Gómez-Lahoz, A.M.; Pekarek, L.; Castellanos, A.J.; Noguerales-Fraguas, F.; Coca, S.; Guijarro, L.G.; García-Honduvilla, N.; Asúnsolo, A.; et al. Nutritional Components in Western Diet Versus Mediterranean Diet at the Gut Microbiota-Immune System Interplay. Implications for Health and Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustig, R.H. Ultraprocessed Food: Addictive, Toxic, and Ready for Regulation. Nutrients 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcon, G.; Roco, J.; Medina, M.; Medina, A.; Peral, M.; Jerez, S. High fat diet-induced metabolically obese and normal weight rabbit model shows early vascular dysfunction: mechanisms involved. International Journal of Obesity 2018, 42, 1535–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palouzier-Paulignan, B.; Lacroix, M.C.; Aimé, P.; Baly, C.; Caillol, M.; Congar, P.; Julliard, A.K.; Tucker, K.; Fadool, D.A. Olfaction under metabolic influences. Chem Senses 2012, 37, 769–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, A.; Fernández-Aranda, F.; Fitó, M.; Jiménez-Murcia, S.; Botella, C.; Fernández-Real, J.M.; Frühbeck, G.; Tinahones, F.J.; Fagundo, A.B.; Rodriguez, J.; et al. A Lower Olfactory Capacity Is Related to Higher Circulating Concentrations of Endocannabinoid 2-Arachidonoylglycerol and Higher Body Mass Index in Women. PloS one 2016, 11, e0148734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, Z.M.; DelGaudio, J.M.; Wise, S.K. Higher Body Mass Index Is Associated with Subjective Olfactory Dysfunction. Behavioural neurology 2015, 2015, 675635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stipanuk, M. Biochemical and Physiological Aspects of Human Nutrition. 2000.

- Kallas, O.; Halpern, B.P. Retronasal Discrimination Between Vapor-Phase Long-Chain, Aliphatic Fatty Acids. Chemosensory Perception 2011, 4, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirc, M.; Maas, P.; De Graaf, K.; Lee, H.-S.; Boesveldt, S. Humans possess the ability to discriminate food fat content solely based on retronasal olfaction. Food Quality and Preference 2022, 96, 104449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.-Q.; Xue, C.-H.; Zhang, H.-W.; Xu, L.-L.; Wang, X.-H.; Bi, S.-J.; Xue, Q.-Q.; Xue, Y.; Li, Z.-J.; Velasco, J.; et al. Concomitant oxidation of fatty acids other than DHA and EPA plays a role in the characteristic off-odor of fish oil. Food Chemistry 2023, 404, 134724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, D.W.; Wroblewski, K.E.; Schumm, L.P.; Pinto, J.M.; Chen, R.C.; McClintock, M.K. Olfactory Function in Wave 2 of the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 2014, 69, S134–S143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sollai, G.; Crnjar, R. Association among Olfactory Function, Lifestyle and BMI in Female and Male Elderly Subjects: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollai, G.; Solari, P.; Crnjar, R. Qualitative and Quantitative Sex-Related Differences in the Perception of Single Molecules from Coffee Headspace. Foods 2024, 13, 3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorokowski, P.; Karwowski, M.; Misiak, M.; Marczak, M.K.; Dziekan, M.; Hummel, T.; Sorokowska, A. Sex Differences in Human Olfaction: A Meta-Analysis. Front Psychol 2019, 10, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, S.; Grillo, C.; Agnello, C.; Maiolino, L.; Intelisano, G.; Serra, A. A prospective study evidencing rhinomanometric and olfactometric outcomes in women taking oral contraceptives. Human Reproduction 2001, 16, 2288–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCHNEIDER, R.A.; COSTILOE, J.P.; HOWARD, R.P.; WOLF, S. OLFACTORY PERCEPTION THRESHOLDS IN HYPOGONADAL WOMEN: CHANGES ACCOMPANYING ADMINISTRATION OF ANDROGEN AND ESTROGEN*†. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 1958, 18, 379–390. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell Kärnekull, S.; Jönsson, F.U.; Willander, J.; Sikström, S.; Larsson, M. Long-Term Memory for Odors: Influences of Familiarity and Identification Across 64 Days. Chemical Senses 2015, 40, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaal, B.; Marlier, L.; Soussignan, R. Olfactory function in the human fetus: evidence from selective neonatal responsiveness to the odor of amniotic fluid. Behavioral neuroscience 1998, 112, 1438–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, M.; Finkel, D.; Pedersen, N.L. Odor identification: influences of age, gender, cognition, and personality. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences 2000, 55, P304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öberg, C.; Larsson, M.; Bäckman, L. Differential sex effects in olfactory functioning: The role of verbal processing. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society 2002, 8, 691–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthoff, M.; Tschritter, O.; Berg, D.; Liepelt, I.; Schulte, C.; Machicao, F.; Haering, H.U.; Fritsche, A. Effect of genetic variation in Kv1.3 on olfactory function. Diabetes/metabolism research and reviews 2009, 25, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melis, M.; Tomassini Barbarossa, I.; Crnjar, R.; Sollai, G. Olfactory Sensitivity Is Associated with Body Mass Index and Polymorphism in the Voltage-Gated Potassium Channels Kv1.3. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, N.; Ramazanoglu, L.; Onen, M.R.; Yilmaz, I.; Aydin, M.D.; Altinkaynak, K.; Calik, M.; Kanat, A. Rationalization of the Irrational Neuropathologic Basis of Hypothyroidism-Olfaction Disorders Paradox: Experimental Study. World Neurosurgery 2017, 107, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besser, G.; Erlacher, B.; Aydinkoc-Tuzcu, K.; Liu, D.T.; Pablik, E.; Niebauer, V.; Koenighofer, M.; Renner, B.; Mueller, C.A. Body-Mass-Index Associated Differences in Ortho- and Retronasal Olfactory Function and the Individual Significance of Olfaction in Health and Disease. Journal of clinical medicine 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlin, K.W.; Yuan, Y.; Li, C.; Luo, Z.; Reeves, M.; Kucharska-Newton, A.; Pinto, J.M.; Ma, J.; Simonsick, E.M.; Chen, H. Olfactory Impairment and the Risk of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes in Older Adults. Journal of the American Heart Association 2024, 13, e033320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croy, I.; Nordin, S.; Hummel, T. Olfactory Disorders and Quality of Life—An Updated Review. Chemical Senses 2014, 39, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, P.T.; Vilarello, B.J.; Tervo, J.P.; Waring, N.A.; Gudis, D.A.; Goldberg, T.E.; Devanand, D.P.; Overdevest, J.B. Associations between olfactory dysfunction and cognition: a scoping review. Journal of neurology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzuki, M.; Suzuki, T.; Nagano, M.; Nakamura, S.; Katsumata, Y.; Takamura, A.; Urakami, K. Comparison of olfactory and gustatory disorders in Alzheimer's disease. Neurological sciences : official journal of the Italian Neurological Society and of the Italian Society of Clinical Neurophysiology 2018, 39, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, M.R.; Chen, J.H.; Lobban, N.S.; Doty, R.L. Olfactory dysfunction from acute upper respiratory infections: relationship to season of onset. International forum of allergy & rhinology 2020, 10, 706–712. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, G.W.; Petrovitch, H.; Abbott, R.D.; Tanner, C.M.; Popper, J.; Masaki, K.; Launer, L.; White, L.R. Association of olfactory dysfunction with risk for future Parkinson's disease. Annals of neurology 2008, 63, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, H.; Tamura, K.; Naito, Y.; Ogata, K.; Mogi, A.; Tanaka, T.; Ikari, Y.; Masaki, M.; Nakashima, Y.; Takamatsu, Y. Patient perceptions of symptoms and concerns during cancer chemotherapy: 'affects my family' is the most important. International journal of clinical oncology 2017, 22, 793–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollai, G.; Melis, M.; Mastinu, M.; Paduano, D.; Chicco, F.; Magri, S.; Usai, P.; Hummel, T.; Barbarossa, I.T.; Crnjar, R. Olfactory Function in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Is Associated with Their Body Mass Index and Polymorphism in the Odor Binding-Protein (OBPIIa) Gene. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velluzzi, F.; Deledda, A.; Onida, M.; Loviselli, A.; Crnjar, R.; Sollai, G. Relationship between Olfactory Function and BMI in Normal Weight Healthy Subjects and Patients with Overweight or Obesity. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Kong, S.; Zou, B.; Wang, M.; Cheng, N.; Zhang, H.M.; Sun, J. Investigating factors influencing subjective taste and smell alterations in colorectal cancer patients. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 2025, 33, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummel, T.; Sekinger, B.; Wolf, S.R.; Pauli, E.; Kobal, G. 'Sniffin' sticks': olfactory performance assessed by the combined testing of odor identification, odor discrimination and olfactory threshold. Chem Senses 1997, 22, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, T.; Kobal, G.; Gudziol, H.; Mackay-Sim, A. Normative data for the "Sniffin' Sticks" including tests of odor identification, odor discrimination, and olfactory thresholds: an upgrade based on a group of more than 3,000 subjects. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2007, 264, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crnjar, R.; Solari, P.; Sollai, G. The Human Nose as a Chemical Sensor in the Perception of Coffee Aroma: Individual Variability. Chemosensors 2023, 11, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollai, G.; Tomassini Barbarossa, I.; Usai, P.; Hummel, T.; Crnjar, R. Association between human olfactory performance and ability to detect single compounds in complex chemical mixtures. Physiology & behavior 2020, 217, 112820. [Google Scholar]

- Melis, M.; Tomassini Barbarossa, I.; Hummel, T.; Crnjar, R.; Sollai, G. Effect of the rs2890498 polymorphism of the OBPIIa gene on the human ability to smell single molecules. Behavioural brain research 2021, 402, 113127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuzzi, M.; Lo Scalzo, R.; Testoni, A.; Rizzolo, A. Evaluation of Fruit Aroma Quality: Comparison Between Gas Chromatography–Olfactometry (GC–O) and Odour Activity Value (OAV) Aroma Patterns of Strawberries. Food Analytical Methods 2008, 1, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ruth, S.M.; O'Connor, C.H. Evaluation of three gas chromatography-olfactometry methods: comparison of odour intensity-concentration relationships of eight volatile compounds with sensory headspace data. Food Chemistry 2001, 74, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, S.; Stieger, M.; Boesveldt, S. Can humans smell tastants? Chem Senses 2024, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, G.M. The Cell: A Molecular Approach. 2nd edition; Sinauer Associates 2000: 2000.

- Getchell, T.V.; Margolis, F.L.; Getchell, M.L. Perireceptor and receptor events in vertebrate olfaction. Progress in neurobiology 1984, 23, 317–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pace, U.; Hanski, E.; Salomon, Y.; Lancet, D. Odorant-sensitive adenylate cyclase may mediate olfactory reception. Nature 1985, 316, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelosi, P. Perireceptor events in olfaction. Journal of neurobiology 1996, 30, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollai, G.; Melis, M.; Magri, S.; Usai, P.; Hummel, T.; Tomassini Barbarossa, I.; Crnjar, R. Association between the rs2590498 polymorphism of Odorant Binding Protein (OBPIIa) gene and olfactory performance in healthy subjects. Behavioural brain research 2019, 372, 112030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollai, G.; Melis, M.; Tomassini Barbarossa, I.; Crnjar, R. A polymorphism in the human gene encoding OBPIIa affects the perceived intensity of smelled odors. Behavioural brain research 2022, 427, 113860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Innocenzo, S.; Biagi, C.; Lanari, M. Obesity and the Mediterranean Diet: A Review of Evidence of the Role and Sustainability of the Mediterranean Diet. Nutrients 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Gea, A.; Ruiz-Canela, M. The Mediterranean Diet and Cardiovascular Health. Circulation research 2019, 124, 779–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-González, M.A.; Salas-Salvadó, J.; Estruch, R.; Corella, D.; Fitó, M.; Ros, E. Benefits of the Mediterranean Diet: Insights From the PREDIMED Study. Progress in cardiovascular diseases 2015, 58, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Schwedhelm, C.; Galbete, C.; Hoffmann, G. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet and Risk of Cancer: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archunan, G. Odorant Binding Proteins: a key player in the sense of smell. Bioinformation 2018, 14, 36–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Briand, L. Odorant-Binding Proteins. 2009; pp. 2953-2957.

- Briand, L.; Eloit, C.; Nespoulous, C.; Bézirard, V.; Huet, J.C.; Henry, C.; Blon, F.; Trotier, D.; Pernollet, J.C. Evidence of an odorant-binding protein in the human olfactory mucus: location, structural characterization, and odorant-binding properties. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 7241–7252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Getchell, M.L.; Ding, X.; Getchell, T.V. Immunolocalization of two cytochrome P450 isozymes in rat nasal chemosensory tissue. Neuroreport 1992, 3, 749–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getchell, T.V.; Margolis, F.L.; Getchell, M.L. Perireceptor and receptor events in vertebrate olfaction. Progress in neurobiology 1984, 23, 317–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarazzo, V.; Zsürger, N.; Guillemot, J.C.; Clot-Faybesse, O.; Botto, J.M.; Dal Farra, C.; Crowe, M.; Demaille, J.; Vincent, J.P.; Mazella, J.; et al. Porcine odorant-binding protein selectively binds to a human olfactory receptor. Chem Senses 2002, 27, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagashima, A.; Touhara, K. Enzymatic conversion of odorants in nasal mucus affects olfactory glomerular activation patterns and odor perception. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 2010, 30, 16391–16398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelosi, P. Odorant-binding proteins. Critical reviews in biochemistry and molecular biology 1994, 29, 199–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelosi, P. Odorant-binding proteins: structural aspects. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1998, 855, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pevsner, J.; Hwang, P.M.; Sklar, P.B.; Venable, J.C.; Snyder, S.H. Odorant-binding protein and its mRNA are localized to lateral nasal gland implying a carrier function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1988, 85, 2383–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melis, M.; Sollai, G.; Masala, C.; Pisanu, C.; Cossu, G.; Melis, M.; Sarchioto, M.; Oppo, V.; Morelli, M.; Crnjar, R.; et al. Odor Identification Performance in Idiopathic Parkinson's Disease Is Associated With Gender and the Genetic Variability of the Olfactory Binding Protein. Chem Senses 2019, 44, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melis, M.; Mastinu, M.; Sollai, G. Effect of the rs2821557 Polymorphism of the Human Kv1.3 Gene on Olfactory Function and BMI in Different Age Groups. Nutrients 2024, 16, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| YES | NO | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Palmitic acid | 55 (78.57) | 15 (21.43) | 0.001 |

| Oleic acid#break# Linoleic acid |

67 (95.71) | 3 (4.29) | |

| 66 (94.29) | 4 (5.71) |

| Group | YES | NO | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Females | Palmitic acid | 29 (76.32) | 9 (23.68) | 0.002 |

| Oleic acid | 37 (97.37) | 1 (2.63) | ||

| Linoleic acid | 37 (97.37) | 1 (2.63) | ||

| Males | Palmitic acid | 26 (81.25) | 6 (18.75) | 0.263 |

| Oleic acid | 30 (93.75) | 2 (6.25) | ||

| Linoleic acid | 29 (90.63) | 3 (9.37) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).