1. Introduction

The implantable medical devices used in the mobile joints of the human body, as well as for dental purposes, require biocompatibility with the surrounding tissues and organs, mechanical strength, and corrosion resistance. The body fluids constitute a hostile environment for the implant, which is also subjected to various loads. The implant, due to corrosion, corrosion associated with fatigue, or friction with bones and other body parts, can detach particles, which, when coming into contact with bodily fluids, can migrate to locations far from the source, causing complications for patients. Okazaki [

1] evaluated the properties of metallic biomaterials concerning the effect of friction on anodic polarization.

Metallic particles released from the corrosion process may move passively through tissue and/or the circulatory system or can be actively transported [

2], compromising biocompatibility. According to Anderson [

3], we cannot assure that a biocompatible biomaterial for a given application will also be biocompatible in another area of application.

Among the characteristics related to the effects caused by metal implants in the human body are the structure of the metal surface, its mechanical properties, size, and shape. Regarding the effects caused by the implant body, factors include the existence of wear particles in the physiological environment, the state of hydration of the medium, the intensity of efforts or stresses to which the entire human body is subjected and, consequently, the implant, as well as the corrosion and oxidation of the surface, which are topics of interest for this work [

3].

The orthopedic implants are designed and manufactured so that when used under the intended conditions and for their intended purposes, any risks associated with the implants’ use are deemed acceptable in comparison to the benefits for the patients.

The ISO 5832-1 stainless steel is commonly used for implant manufacturing due to its good mechanical and electrochemical properties and low cost [

4,

5]. Stainless steel medical devices are used as permanent or temporary implants to assist in bone healing. Marking techniques are employed for identification or traceability purposes [

4,

5,

6,

7].

The micro-scale abrasion test (or ball-cratering wear test) is a practical method for analyzing the wear resistance of diverse materials [

8,

9,

10]. The ball-cratering wear test has been widely utilized in studies focusing on the abrasive wear behavior of various materials [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

Wear tests conducted using the ball-cratering technique offer advantages over other types of tests, as they can be performed with normal forces (N) and sphere rotations (n) that are relatively low (N < 0.5 N and n < 80 rpm) [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21].

Topographic aspects directly affect several surface properties, including electrochemical and tribological responses. Rougher surfaces increase susceptibility to localized corrosion and decrease mechanical resistance [

22,

23]. Corrosion is the process through which metallic materials deteriorate due to their chemical reactivity with the environment [

24,

25]. Some metals, such as iron, titanium, aluminum, copper, chromium, and nickel, form an oxide film on their surface that can slow down the corrosion phenomenon through a barrier effect and cathodic protection [

26].

The aim of this study is to evaluate the cytotoxicity, corrosion resistance, and tribological behavior of ISO 5832-1 austenitic stainless steel (SS) marked using laser and mechanical techniques, through a ball-cratering wear method and electrochemical tests.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Specimens of ISO 5832-1 austenitic stainless steel (chemical composition (wt%): 0.023 C, 0.78 Si, 2.09 Mn, 0.026 P, 0.0003 S, 18.32 Cr, 2.59 Mo, 14.33 Ni, and Fe balance) were marked mechanically and with a nanosecond Q-switched Nd: YAG laser, at a wavelength of 1064 nm, with a frequency of 20 Hz and a scanning speed of 4 mm s−1. Balls made of AISI 316L stainless steel and polypropylene (PP) with a diameter of D = 25.4 mm (D = 1”) were used.

A phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS) with the chemical composition (g/l): 8.0 NaCl, 0.2 KCl, 1.15 Na2HPO4, 0.2 KH2PO4, a pH value of 7.4, and a conductivity of 15.35 mS was applied as a lubricant between the ball and the specimen.

Table 1 presents the hardness (H) of the biomaterials used in this study (specimens and balls).

2.2. Ball-Cratering Wear Test Equipment and Data Acquisition

An apparatus with a free-ball configuration was used for the sliding wear tests. Two load cells were employed in the ball-cratering equipment: one to control the normal force (N) and another to measure the tangential force (T) developed during the experiments. The “Normal” and “tangential” force load cells have a maximum capacity of 50 N and an accuracy of 0.001 N. The values of “N” and “T” are read by a readout system.

Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of the wear test principle, where a rotating ball is pressed against the tested specimen. At the same time, a lubricant is provided between the ball and the specimen during the experiments. The ball-cratering wear test aims to create “wear craters” on the specimen. The wear volume (V) can be calculated as a function of the wear crater radius (b), using equation 1 [

11], where R is the radius of the ball.

Table 2 outlines the test conditions chosen for the experiments conducted in this work.

Based on the density (ρ) of the material of the ball (AISI 316L SS: ρ316L = 8 g/cm³; polypropylene: ρPP = 0.91 g/cm³) were defined the values of the normal (N) for the wear experiments: N316L = 0.40 N and NPP = 0.05 N.

The ball’s rotational speed was n = 75 rpm. For n = 75 rpm and D = 25.4 mm (R = 12.7 mm), the tangential sliding velocity at the ball’s external diameter is equal to v = 0.1 m/s.

The wear tests were conducted during t = 10 min, with the values of v = 0.1 m/s and t = 10 min (t = 600 s), which calculated a sliding distance of S = 60 m.

All experiments were conducted without interruption, and the chemical solution was continuously agitated and fed between the ball and the specimen during the experiments at a rate of 1 drop every 10 seconds.

Both the normal force (N) and the tangential force (T) were continuously monitored and recorded. The coefficient of friction (COF) was then determined using equation 2 [

11].

2.3. Surface Characterizations

Surface analyses were performed using an optical microscope (Olympus, TM) and a scanning electron microscope paired with a high-resolution field emission gun (SEM-FEG, FEI – INSPECT F50). The surface chemical composition was determined through energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) semi-quantitative analysis and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), obtained using a Kratos XSAM HS equipment under ultra-high vacuum (p ≈ 3 × 10−8 Torr). The excitation source was magnesium K, with an energy of 1.2536 keV [

27].

2.4. Electrochemical Experiments

The electrochemical tests were conducted using a potentiostat/galvanostat (Gamry PCI4/300). A conventional three-electrode cell arrangement was employed: the metallic specimen as the working electrode, a platinum wire as the counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl (KCl, 3 M) electrode as the reference. The electrolyte was a phosphate buffer solution (PBS) at pH 7.4 and 37 ºC. The open circuit potential versus time was monitored for 17 hours (61200 s), after which the cyclic potentiodynamic polarization measurement was performed at a scan rate of 0.167 mV.s−1. All electrochemical tests were repeated six times to confirm their reproducibility.

2.5. Cytotoxicity Analysis

Cytotoxicity was assessed using a quantitative methodology. The assay is based on determining viable cells after exposing the cell population to different concentrations of the extract obtained from incubating the specimens in RPMI (Gibco ®) cell culture medium at 37 °C for 24 hours under constant stirring.

The number of viable cells was analyzed using a colorimetric method that involved the incorporation of supravital dye along with the electron-coupling agent (MTS/PMS), followed by spectrophotometric reading at 490 nm. The dye uptake by the cell population directly correlates with the count of viable cells in culture.

The relationship between the concentration of the extract and the number of viable cells resulted in a dose-response curve, and the parameter used to assess cytotoxicity is calculated by the extract concentration that killed 50% of the exposed cells in the test (Inhibitory Concentration – IC50%).

The identification of the test substances was extracted from ISO 5832-1 austenitic stainless steel with mechanical marks and laser marks; their controls were conducted under “Positive Control: Phenol 0.5%” and under “Negative control: commercially pure titanium.” The system test was the CHO-K1 cell line derived from Chinese hamster ovary (cell type: epithelial form).

The preparation of extracts was according to ISO 10993-12. Serial dilutions with five concentrations were defined: 100%, 50%, 25%, 12.5%, and 6.25%. The net extractor was RPMI culture medium (Gibco ®) with serum, and the incubation condition was 24 h at 37 °C with constant stirring. The test was conducted in quadruplicate incubated plates for 24 h in a CO2 glasshouse at 37 °C.

The vital dye MTS / PMS was applied in the following conditions:

1) Solution of MTS / PMS prepared with PBS in a concentration of 20:1;

2) Solution of MTS / PMS more culture medium with serum: 20 μl was added to the solution of MTS / PMS, more 80 μl of culture medium in each test well.

Finally, the incubation was conducted in a glasshouse with CO2 at 37 °C for 2 h, and the reading was made in a microplate reader at 490 nm.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Wear Volume Analysis

Figure 2 (a)–(f) presents some images of the specimens submitted to wear tests. Surfaces marked via laser and mechanical techniques were analyzed by optical microscopy. For comparison reasons, the pristine surfaces were also evaluated. These results are relevant to the biomaterial field as they enable to choice of a suitable area to perform markings to avoid wear.

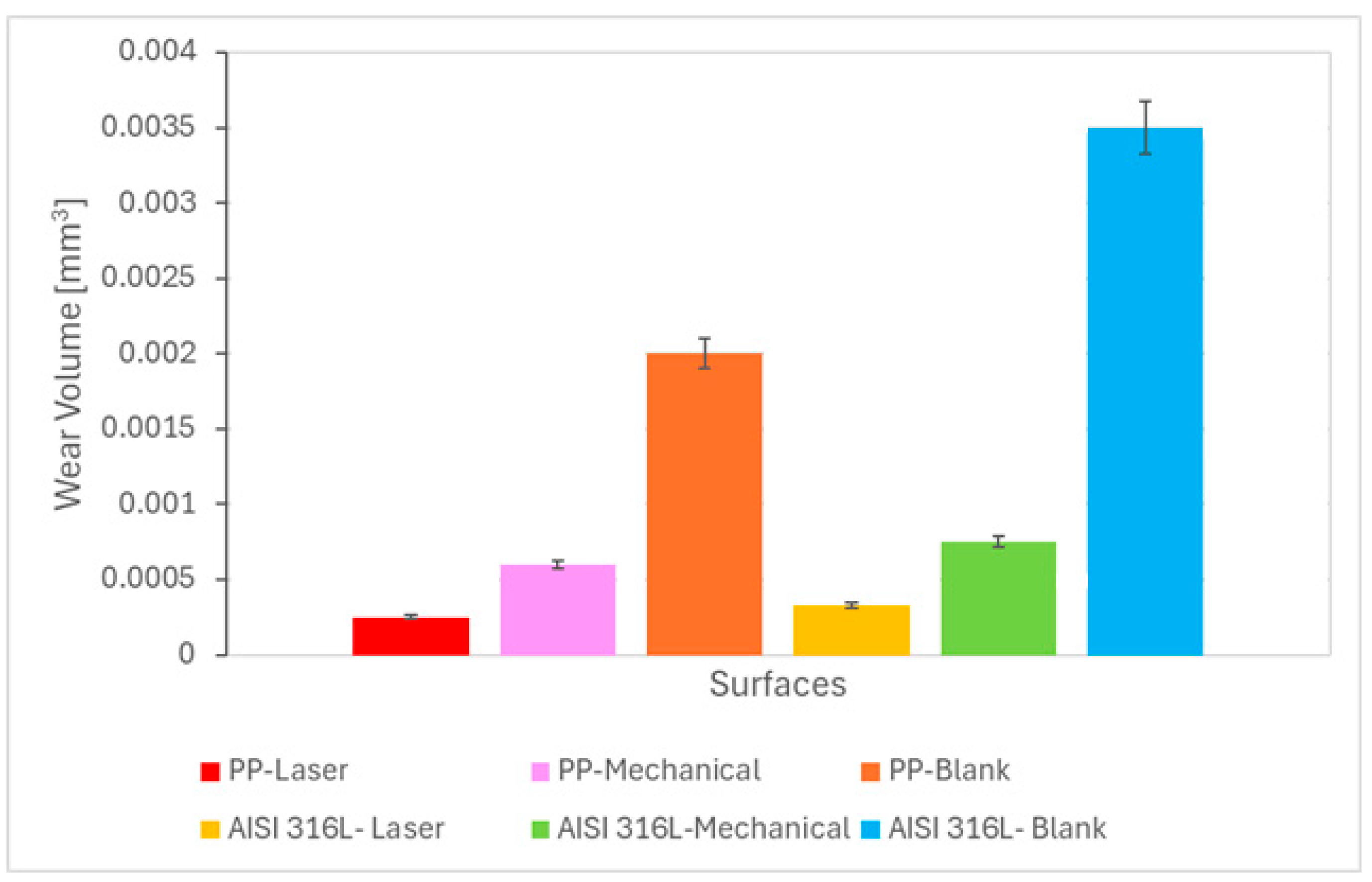

Figure 3 presents the wear volume (V) for the pristine and mechanically- and laser-marked specimens. It is demonstrated that the wear volume decreased on the marked specimens. This decrease is associated with a possible increase in the hardness of the specimen due to localised heat treatment produced by the laser beam or to the mechanical work by the stamp.

3.2. Analysis of the Coefficient of Friction

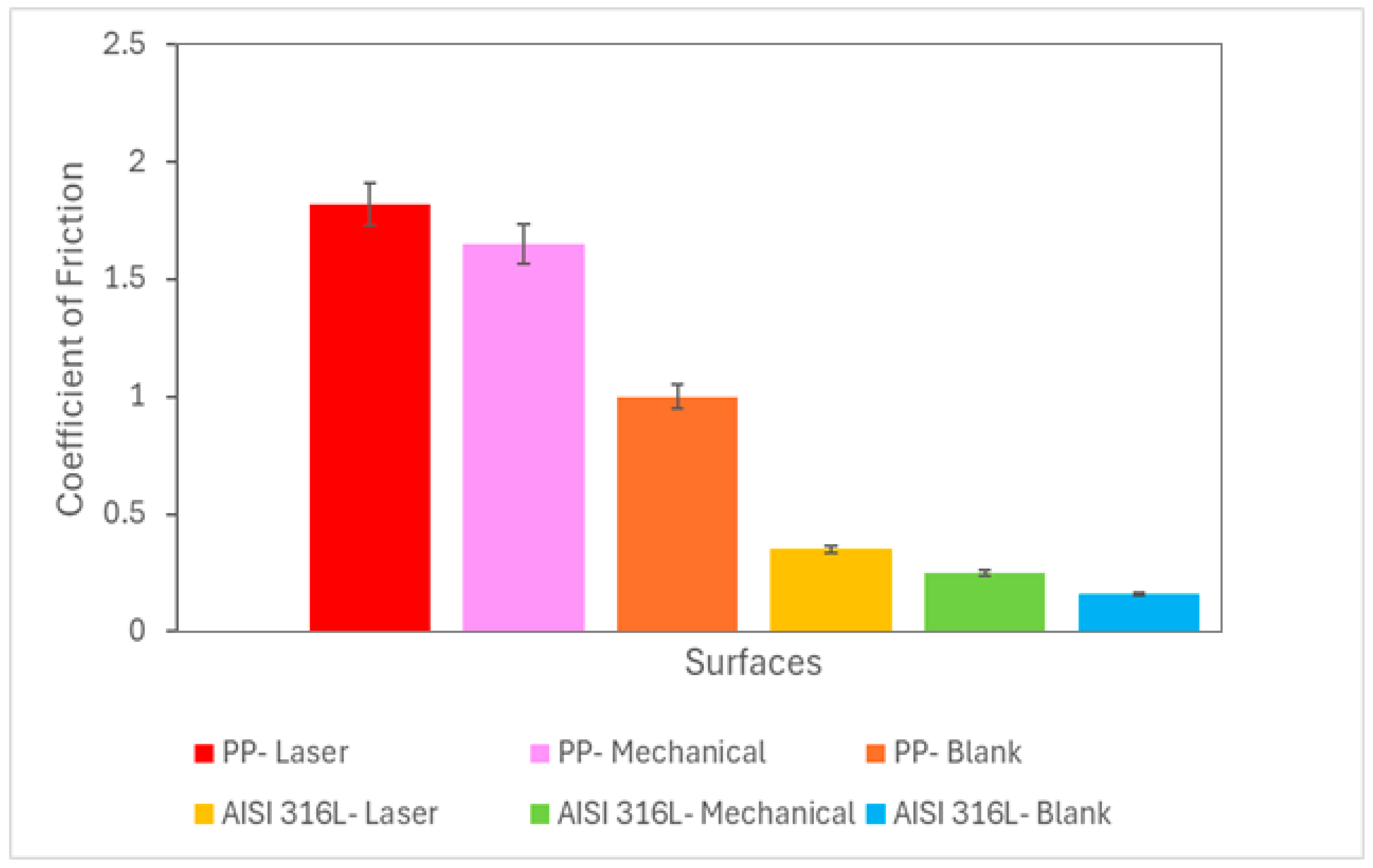

Figure 4 shows the coefficient of friction (

μ) values for the mechanical- or laser-marked specimens. For the AISI 316L austenitic stainless steel (SS) ball tests, the coefficient of friction was lower when compared with the coefficient of friction values reported for the polypropylene (PP) ball.

The amount of wear increased with the increase in normal force. This behaviour was reported in the literature [

28,

29,

30,

31]. The highest wear volume values were reported for blank samples. The marks made mechanically or by laser increased the wear resistance of the samples.

Regarding the coefficient of friction, the highest values were observed using the polypropylene ball. Magnitudes of these values were reported elsewhere [

12] with the same type of assay under a different tribological system.

No direct relationship between wear volume and friction coefficient was observed, i.e., the highest value of wear volume was not related to the highest value of coefficient of friction.

3.3. Cytotoxicity Analysis

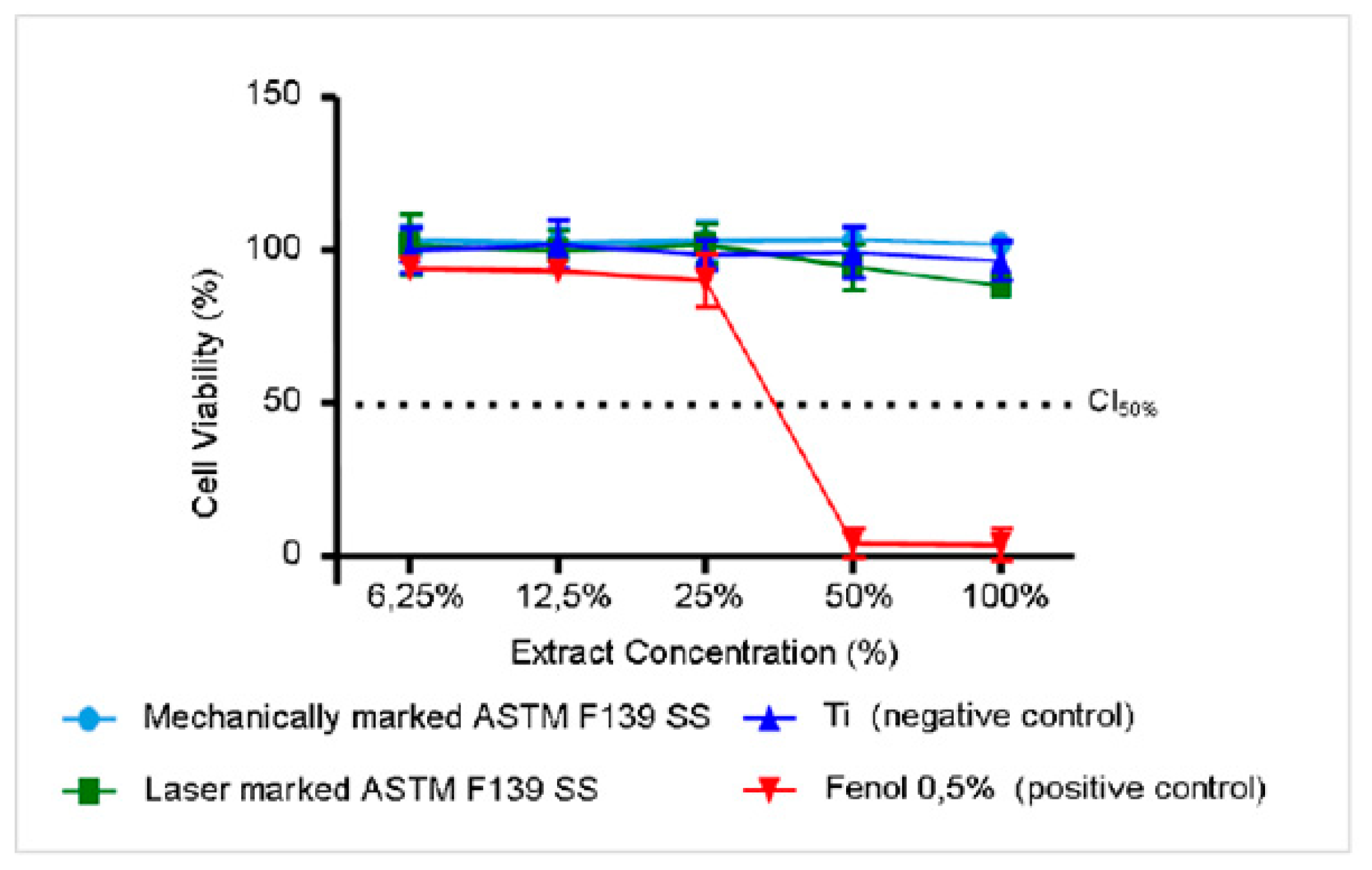

Table 3 shows the pH of the extracts at a concentration of 100%. The results presented in

Figure 5 indicate that the ISO 5832-1 SS exhibited a similar behaviour to the negative control, that is, no cytotoxicity. This is indicated by the cell viability curve for mechanically and laser-marked samples above the IC

50% level of cytotoxicity. Blank specimens were not evaluated, as this alloy is commonly used for biomedical applications.

The cytotoxicity of the ISO 5832-1 SS was evaluated in the present study according to ISO 10993- 5 [

32]. No cytotoxicity is desired for stainless steels for medical and dental applications [

33]. The slight decrease in cell viability for the laser-marked samples is explained by their susceptibility to localized corrosion [

4,

5]. Since this method examines only the surface’s characteristics and corrosion is a surface phenomenon, the laser marking process affects the corrosion resistance of austenitic stainless steel, producing a less protective passive film with areas prone to its breakdown [

4], although in this case, the samples were considered non-cytotoxic.

3.4. Electrochemical Tests

Electrochemical measurements are important to provide an estimate of the corrosion susceptibility of biomaterials with different surface finishes. The passive film formed on the ISO 5832-1 stainless steel plays a dominant role in the improvement of corrosion resistance. When the alloy is in contact with a simulated body fluid, the formation of a less defective and more homogeneous passive film is generated [

34,

35].

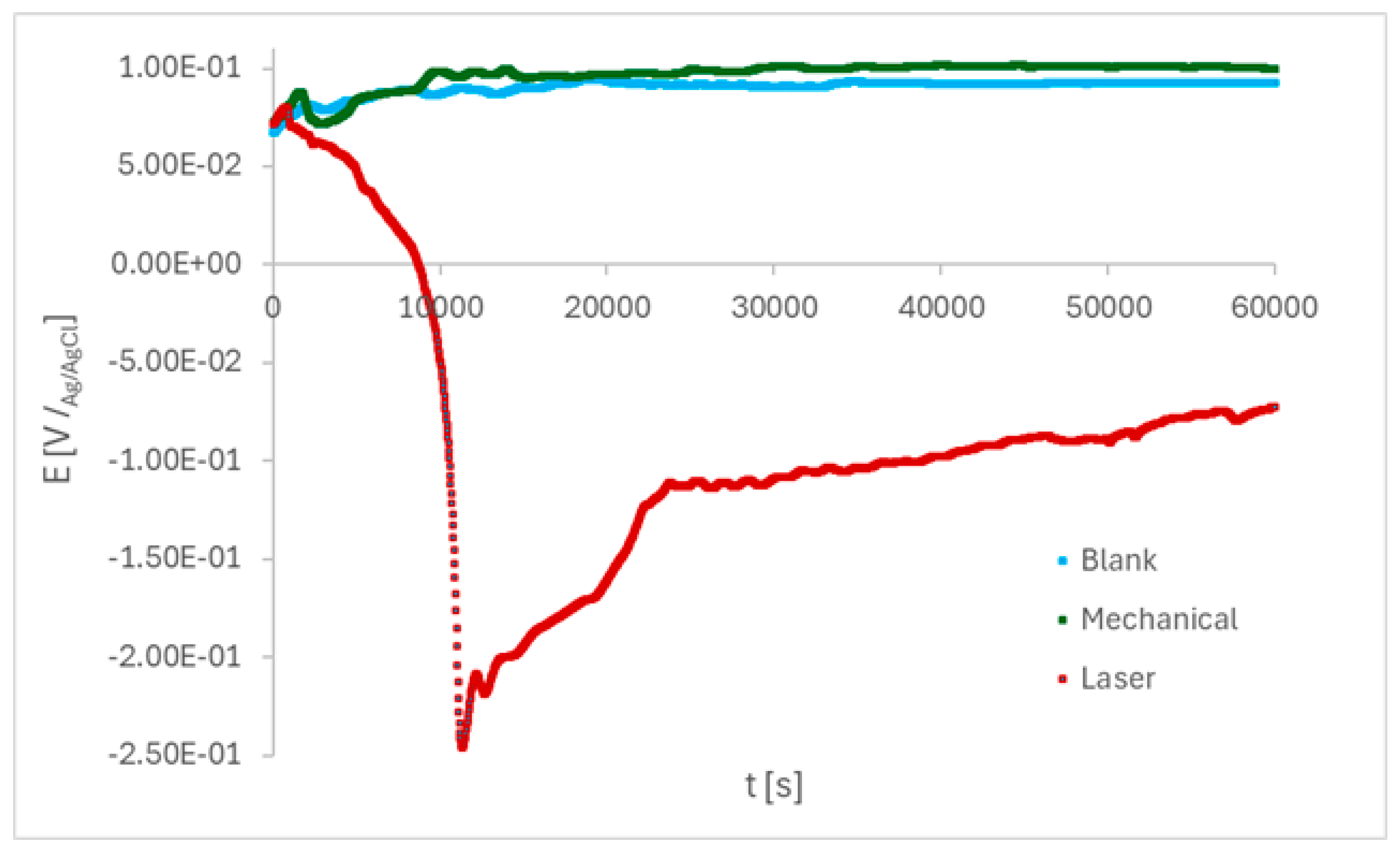

Initially, the open circuit potential (OCP) was monitored in PBS during 61200 s, as shown in

Figure 6. The E

ocp shifted towards a positive direction, suggesting a protective oxide layer begins to grow on blank and mechanically-marked samples, and dropped to negative values on laser-marked samples for the first periods of immersion. Then, E

ocp shifted to values around -0.1 V /

Ag/AgCl and showed an increasing tendency throughout the test for the laser-treated sample. For blank and mechanically-marked samples, E

ocp around 0.07 V /

Ag/AgCl were found at the beginning of the monitoring period and then shifted to nobler potentials, and showed an E

ocp stabilizing tendency throughout the test, starting at around 30000 s.

The OCP fluctuations are explained by the instantaneous competition between the oxide layer formation and dissolution [

36] during the first periods of immersion. The passive film in the laser-marked regions is irregular, and the appearance of micro-pits leads to an oscillation in the potential, which may be attributed to the micron defects originating during the laser melting process. Conversely, the broken passive films are re-passivated quickly, indicating an increase in the potential.

Figure 7 shows the anodic linear polarization curves of the marked and pristine ISO 5832-1 SS samples after 17 h of immersion in PBS solution. Low corrosion current density (i

corr) indicates low corrosion rate or high corrosion resistance [

37,

38].

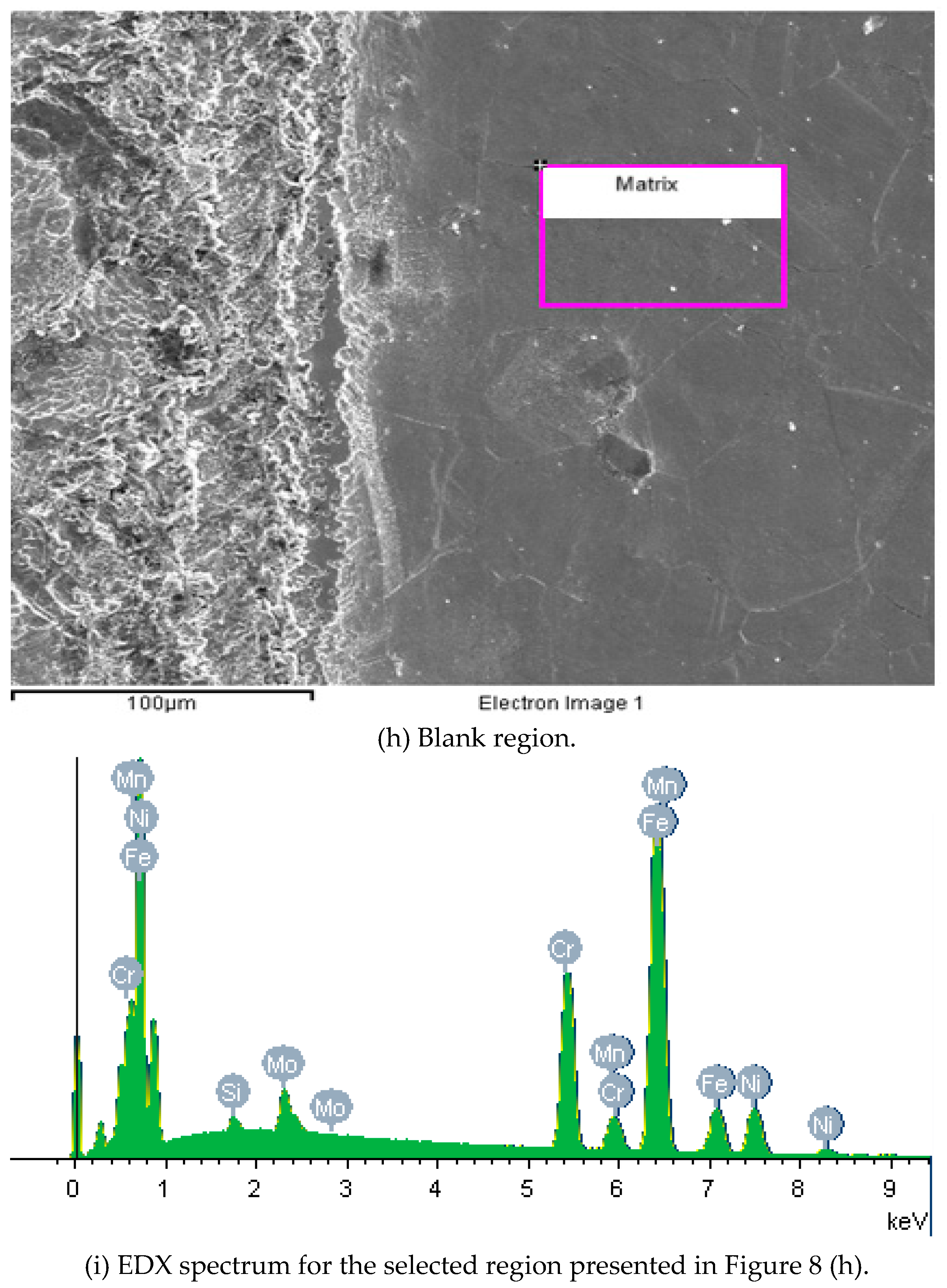

The pitting susceptibility of the marked specimens was evidenced by the current oscillations observed before the breakdown of the protective layer. These results indicated that the passive film formed on laser-marked specimens had a greater number of defects than those produced in the mechanical and blank specimens, as

Figure 8 illustrates. A lower pitting resistance is associated with the laser-marked samples. This behaviour was confirmed by the XPS data, as presented in

Table 4.

The EDX spectrum displays data obtained at the selected region of

Figure 8 (f). This technique has identified Al and Si concentrations, which must be found as ceramics inclusions of Al

2O

3 and SiO

2. These ceramic inclusions can be easily detached during the wear tests or act as a potential site to start the corrosive processes. For non-marked regions, Al concentrations were not found, as observed in

Figure 8 (i). EDX data were also indicative of Cr and Mn enrichment and Mo and Fe impoverishment at the laser-marked area.

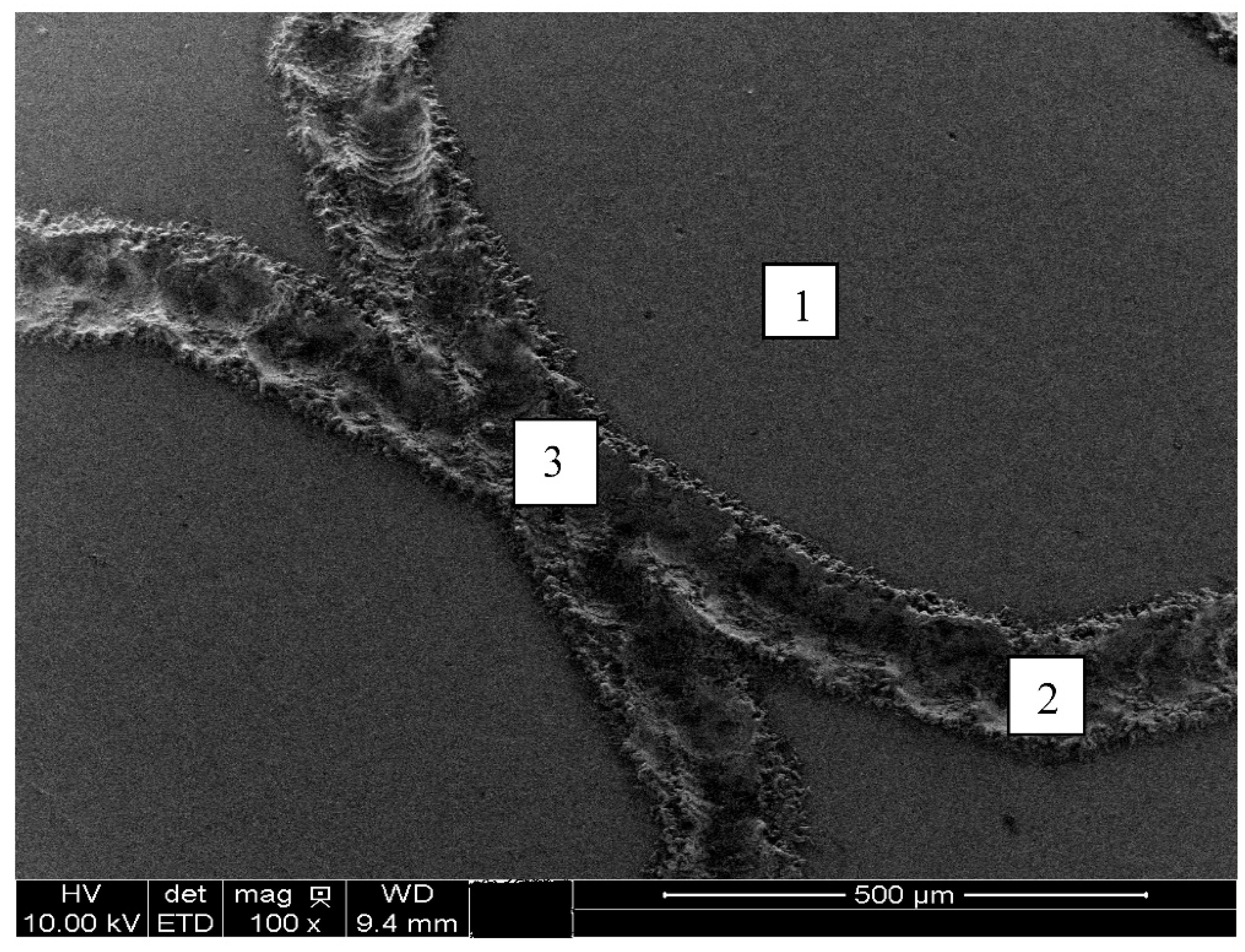

A prominent effect of the laser marking process was the significant change in chemical composition of the oxide passive film, as shown in

Table 4, which displays data obtained by XPS of different regions of the samples before cyclic polarisation, as shown in

Figure 9. Three areas were investigated: (a) the matrix, i.e., pristine specimens, (b) laser-marked areas, (c) laser-marked areas with double laser incidence.

Examining the variation in the Cr/Fe ratio throughout the surface’s selected regions provides insights into the variation of oxide layers. The Cr/Fe ratio increases with the incidence of the laser beam. Similar surface composition atomic percentages were found by Swayne et al. [

39] for samples of AISI 316L treated by Q-switched Nd-YAG laser.

Suslov et al. [

40] observed that higher laser energy density results in reduced Cr and Fe metallic phase content within the subsurface layer. This outcome is due to the increased oxide formation during the laser thermal exposure in an oxygen environment. An increase in energy density has resulted in a reduction in chromium oxide content. This phenomenon can be attributed to the different oxidation sensitivities of iron and chromium, with iron requiring higher temperatures for oxidation. It is crucial to note that the discrepancies observed between our findings and those of other researchers are due to their insufficient specification of the exact locations selected for analysis on the laser-treated surfaces. In the current work, these regions are delineated, as illustrated in

Figure 8 and

Figure 9.

This work aimed to evaluate the effect of two marking techniques on the wear and corrosion resistance of the ISO 5832-1 stainless steel. It was found that the laser markings reduce the resistance to pitting corrosion due to significantly changing the characteristics of the passive film, compared to the material without markings.

Pulsed laser marking processes are fast and extremely localised. Some chemical elements like Cr, Mo, and Mn concentrate in an area and impoverish the surrounding areas. Thus, the electrochemical reactions occurred at regions near the laser-marked sites. Furthermore, the pits are more prone to nucleate and propagate in the areas where the laser passed twice.

Oxide inclusions were raised into relief by the double incidence of the laser beam. The attack of the steel-matrix surrounding the inclusions promotes the formation of micro-crevices, favoring pitting growth and propagation. The roughness of the surface potentiates the electrochemical attack. This was the mechanism proposed to explain the increased susceptibility to localized corrosion at the laser-affected areas.

Wear and corrosion processes are additional effects arising from the interaction between metallic biomaterials and the body tissues [

41].

4. Conclusions

The tribological behaviour is influenced by the type of the marking process used on this biomaterial, and the wear rate is dependent on the normal force and the kind of sphere. The surface characterization showed microstructure modification due to the high temperatures involved in the laser engraving process. None of the samples were considered cytotoxic, but the laser-marked surfaces showed the lowest cellular viability among the tested surfaces.

The laser engraving technique induces large variation in the chemical composition of the surface, high concentration of defects, and increased roughness. The inclusions found at the surface were composed mainly of oxides. These types of ceramic inclusions are not melted by the fast incidence of the laser beam, remaining in evidence on the surface. These modifications in the material microstructure reduced its pitting corrosion resistance, leading to the breakdown of the passive film. The marked surfaces, at OCP, behave as anodic sites, dissolving actively in PBS medium.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, grant # 443931/2023-2), Prof. Eng. Tomaz Puga Leivas, from IOT-HCFMUSP, for kindly providing the marked samples, MSc James Wallace for CAD drawing support, and Dr. Olga Zazuco Higa for the cytotoxicity analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Y. Okasaki, Effect of friction on anodic polarization properties of metallic biomaterials, Biomaterials 23 (2002) 2071-2077. [CrossRef]

- J. Black, Systemic effects of biomaterials, Biomaterials 5 (1984) 11-18. [CrossRef]

- J.M. Anderson, Biological response to materials, Materials Research 31 (2001) 81-110. [CrossRef]

- E. F. Pieretti, I. Costa, Surface characterisation of ASTM F139 stainless steel marked by laser and mechanical techniques, Electrochimica Acta 114 (2013) 838 – 843. [CrossRef]

- E. F. Pieretti, S. M. Manhabosco, L. F. P. Dick, S. Hinder, I. Costa, Localized corrosion evaluation of the ASTM F139 stainless steel marked by laser using scanning vibrating electrode technique, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and Mott-Schottky techniques, Electrochimica Acta 124 (2014) 150 – 155. [CrossRef]

- E. F. Pieretti, R. P. Palatnic, T. P. Leivas, I. Costa, M. D. M. Neves, Evaluation of Laser Marked ASTM F 139 Stainless Steel in Phosphate Buffer Solution with Albumin, Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 9 (2014) 2435 – 2444. [CrossRef]

- E. F. Pieretti, I. Costa, R. A. Marques, T. P. Leivas, M. D. M. Neves, Electrochemical Study of a Laser Marked Biomaterial in Albumin Solution, Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 9 (2014) 3828 – 3836. [CrossRef]

- K. Adachi, I. M. Hutchings, Wear-mode mapping for the micro-scale abrasion test, Wear 255 (2003) 23-29. [CrossRef]

- G. B. Stachowiak, G. W. Stachowiak, O. Celliers, Ball-cratering abrasion tests of high-Cr white cast irons, Tribology International 38 (2005) 1076-1087. [CrossRef]

- G. B. Stachowiak, G. W. Stachowiak, J. M. Brandt, Ball-cratering abrasion tests with large abrasive particles, Tribology International 39 (2006) 1-11. [CrossRef]

- K.L. Rutherford, I.M. Hutchings, Theory and application of a micro-scale abrasive wear test, Journal of Testing and Evaluation - JTEVA 25 (2) (1997) 250-260. [CrossRef]

- Ali Günen, Mourad Keddam, Sabri Alkan, Azmi Erdoğan, Melik Çetin, Microstructural characterization, boriding kinetics and tribo-wear behavior of borided Fe-based A286 superalloy, Materials Characterization, 186, 2022, 111778. [CrossRef]

- A.P. Krelling, C.E. da Costa, J.C.G. Milan, E.A.S. Almeida, Micro-abrasive wear mechanisms of borided AISI 1020 steel, Tribol. Int., Volume 111, 2017, 234-242. [CrossRef]

- D.N. Allsopp, R.I. Trezona, I.M. Hutchings, The effects of ball surface condition in the micro-scale abrasive wear test, Tribology Letters, 5 (1998), pp. 259-264. [CrossRef]

- R.I. Trezona, D.N. Allsopp, I.M. Hutchings, Transitions between two-body and three-body abrasive wear: influence of test conditions in the microscale abrasive wear test, Wear 225-229 (1999) 205-214. [CrossRef]

- A comparison of boundary wear film formation on steel and a thermal sprayed Co/Cr/Mo coating under sliding conditions, Wear, 252 (2002), pp. 227-239.

- Zhenguo Wang, Yan Li, Weijiu Huang, Xiaoli Chen, Haoran He, Micro-abrasion–corrosion behaviour of a biomedical Ti–25Nb–3Mo–3Zr–2Sn alloy in simulated physiological fluid, J. of the Mec. Behav. of Biomed. Mater., Volume 63, 2016, 361-374.

- K. Bose, R.J.K. Wood, Optimum test conditions for attaining uniform rolling abrasion in ball cratering tests on hard coatings, Wear 258 (2005) 322-332. [CrossRef]

- N. Axén, S. Jacobson, S. Hogmark, Influence of hardness of the counterbody in three-body abrasive wear – an overlooked hardness effect, Tribology International 27 (4) (1994) 233-241. [CrossRef]

- M.G. Gee, M.J. Wicks, Ball crater testing for the measurement of the unlubricated sliding wear of wear-resistant coatings, Surf. And Coat. Technol. 133-134 (2000) 376-382. [CrossRef]

- R. Colaço, R. Vilar, Abrasive wear of metallic matrix reinforced materials, Wear, 255 (2003) 643–650. [CrossRef]

- Pieretti, E. F.; Leivas, T. P.; Pillis, M. F.; Das Neves, M. D. M., Failure Analysis of Metallic Orthopedic Implant for Total Knee Replacement. Materials Science Forum (Online), v. 1012, p. 471-476, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Pieretti, E. F.; Corrêa, O. V.; Neves, M. D. M.; Antunes, R. A.; Pillis, M. F., Tribology analysis on anodized aluminum surfaces for biomedical purposes. Brazilian Journal of Motor Behavior, v. 17, 196-197, 2023.

- J. Feng, Z. M. Wang, D. Zheng, G.-L. Song Influence of dissolved oxygen on the corrosion of mild steel in a simulated cement pore solution under supercritical carbon dioxide, Const. Build. Mat. 311 (2021) 125270. [CrossRef]

- X. Han, D. Y. Yang, D. M. Frangopol, Optimum maintenance of deteriorated steel bridges using corrosion resistant steel based on system reliability and life-cycle cost, Engg. Struct. 243 (2021) 112633. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, G. Tan, J. Tang, L. Zhang, G. Shen, Z. GU, X. Jie, Enhanced corrosion and wear resistance of Zn–Ni/Cu–Al2O3 composite coating prepared by cold spray. J Solid State Electrochem 27 (2023).439–453. [CrossRef]

- J.F. Moulder, W.F. Stickle, P.E. Sobol, K.D. Bomben, J. Chastain (Ed.), Handbook of X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy, PerkinElmer Corporation, Physical Electronics Division, Eden Prairie, MN, USA (1992).

- K. Adachi, I.M. Hutchings, Wear-mode mapping for the micro-scale abrasion test, Wear 255 (2003) 23-29. [CrossRef]

- K. Adachi, I.M. Hutchings, Sensitivity of wear rates in the micro-scale abrasion test to test conditions and material hardness, Wear 258 (2005) 318-321. [CrossRef]

- D.N. Allsopp, I.M. Hutchings, Micro-scale abrasion and scratch response of PVD coatings at elevated temperatures, Wear 251 (2001) 1308-1314. [CrossRef]

- G.B. Stachowiak, G.W. Stachowiak, Wear mechanisms in ball-cratering tests with large abrasive particles, Wear, 256 (2004), pp. 600-607. [CrossRef]

- ISO 10.993 - Biological evaluation of medical devices - part 5: Tests for cytotoxicity: in vitro methods, p. 1-7, 1992.

- R. A. Marques, S. O. Rogero, M. Terada, E. F. Pieretti, I. Costa, Localized Corrosion Resistance and Cytotoxicity Evaluation of Ferritic Stainless Steels for Use in Implantable Dental Devices with Magnetic Connections, Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 9 (2014) 1340 – 1354. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Li, S.J., Hao, Y.L., Yang, R., Electrochemical characterization of nanostructured Ti–24Nb–4Zr–8Sn alloy in 3.5% NaCl solution. Int. J. Hydrog. Energ. 2014; 39(30):17452–17459.

- Tang, J., Luo, H. Y., Zhang, H. B., Enhancing the surface integrity and corrosion resistance of Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy through cryogenic burnishing, Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017; 88: 2785–2793. [CrossRef]

- Hodgson, A. W. E., Mueller, Y., Forster, D., Virtanen, S., Electrochemical characterisation of Passive Films on Ti Alloys Under Simulated Biological Conditions, Electrochi. Acta. 2002; 47 (12): 1923. [CrossRef]

- Hou, X., Ren, Q., Yang, Y., Cao, X., Hu, J., Zhang, C., Deng, H., Yu, D., Li, K., Lan, W. Effect of temperature on the electrochemical pitting corrosion behavior of 316L stainless steel in chloride-containing MDEA solution. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng., 2021; 86: 103718. [CrossRef]

- Jafarzadegan, M., Ahmadian, F., Salarvand, V., Kashkooli, S. Investigation of microstructure and corrosion resistance of AISI 304 stainless steel joint with ER308 and ERNiCr-3 filler metals by GTAW. Metall. Res. Technol., 2020; 117: 507. [CrossRef]

- Swayne, M., Perumal, G., Padmanaban, D. B., Mariotti, D., Brabazon, D., Exploring the impact of laser surface oxidation parameters on surface chemistry and corrosion behaviour of AISI 316L stainless steel, App. Surf. Sci. Adv., 22, 2024, 100622. [CrossRef]

- R. Suslov, V. P. R. Bogdanov, V. Vorkel, I. Filatov, A. Grishina, M. Sokolov, S. Khubezhov, E. Davydova, G. Romanova, Effect of chemical composition on pitting corrosion resistance of AISI 430 stainless steel after laser surface structuring, Optics & Laser Technol. 183 (2025) 112286. [CrossRef]

- Feyzi, M., Fallahnezhad, K., Taylor, M., Hashemi, R., The Tribocorrosion Behaviour of Ti-6Al-4 V Alloy: The Role of Both Normal Force and Electrochemical Potential, Tribology Letters, 70:83 (2022). [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the operational principle of the ball-cratering wear test.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the operational principle of the ball-cratering wear test.

Figure 2.

(a). Wear test conducted on the ISO 5832-1 SS, mechanically marked. Ball of AISI 316L SS. (b). Wear test conducted on the ISO 5832-1 SS, mechanically marked. Ball of polypropylene. (c). Wear test conducted on the ISO 5832-1 SS marked by laser. Ball of AISI 316L SS. (d). Wear test conducted on the ISO 5832-1 SS marked by laser. Ball of polypropylene. (e). Wear test conducted on the ISO 5832-1 SS without marks. Ball of AISI 316L SS. (f). Wear test conducted on the ISO 5832-1 SS without marks. Ball of polypropylene.

Figure 2.

(a). Wear test conducted on the ISO 5832-1 SS, mechanically marked. Ball of AISI 316L SS. (b). Wear test conducted on the ISO 5832-1 SS, mechanically marked. Ball of polypropylene. (c). Wear test conducted on the ISO 5832-1 SS marked by laser. Ball of AISI 316L SS. (d). Wear test conducted on the ISO 5832-1 SS marked by laser. Ball of polypropylene. (e). Wear test conducted on the ISO 5832-1 SS without marks. Ball of AISI 316L SS. (f). Wear test conducted on the ISO 5832-1 SS without marks. Ball of polypropylene.

Figure 3.

Wear volume as a function of the ball material and the type of marking process.

Figure 3.

Wear volume as a function of the ball material and the type of marking process.

Figure 4.

Coefficient of friction as a function of the ball material and type of marking process.

Figure 4.

Coefficient of friction as a function of the ball material and type of marking process.

Figure 5.

Cell viability versus the extract concentration for samples marked by laser and mechanical techniques.

Figure 5.

Cell viability versus the extract concentration for samples marked by laser and mechanical techniques.

Figure 6.

Variation of the OCP with the immersion time in PBS for the ISO 5832-1 stainless steel, mechanically, laser-marked, and pristine samples. Total time: 61200 s. (n=6).

Figure 6.

Variation of the OCP with the immersion time in PBS for the ISO 5832-1 stainless steel, mechanically, laser-marked, and pristine samples. Total time: 61200 s. (n=6).

Figure 7.

Cyclic potentiodynamic polarisation curves of the ISO 5832-1 stainless steel samples after 17 h of immersion in PBS. (n=6).

Figure 7.

Cyclic potentiodynamic polarisation curves of the ISO 5832-1 stainless steel samples after 17 h of immersion in PBS. (n=6).

Figure 8.

Micrographs images of the ISO 5832-1 stainless steel marked by laser beam, mechanically and without marks (blank), after electrochemical tests in PBS at 37 °C, and semi-quantitative analysis of the EDX spectrum prior to electrochemical tests.

Figure 8.

Micrographs images of the ISO 5832-1 stainless steel marked by laser beam, mechanically and without marks (blank), after electrochemical tests in PBS at 37 °C, and semi-quantitative analysis of the EDX spectrum prior to electrochemical tests.

Figure 9.

Laser-marked region selected for XPS analyses, prior to electrochemical tests, without etching.

Figure 9.

Laser-marked region selected for XPS analyses, prior to electrochemical tests, without etching.

Table 1.

Hardness of the materials used in this work.

Table 1.

Hardness of the materials used in this work.

| |

Material |

Hardness |

| Sample |

ISO 5832-1 SS |

88 HRB |

| Ball |

AISI 316L SS |

25-39 HRC |

| Ball |

Polypropylene |

R85 |

Table 2.

Selected test conditions for the ball-cratering wear experiments.

Table 2.

Selected test conditions for the ball-cratering wear experiments.

| (N) Normal force [N] – ball of AISI 316L SS |

0.40 |

| (N) Normal force [N] – ball of PP |

0.05 |

| (S) Sliding distance [m] |

60.00 |

| (n) Ball rotational speed – [rpm] |

75 |

| (v) Tangential sliding velocity – [m/s] |

0.10 |

| (t) Test duration – [min] |

10 |

Table 3.

Values of pH for the extracts at a concentration of 100%.

Table 3.

Values of pH for the extracts at a concentration of 100%.

| Extracts |

pH |

| CP (Fenol 0.5%) |

7.50 |

| CN (Pure Ti) |

7.50 |

| Mechanically-marked |

7.88 |

| Laser-marked |

7.88 |

Table 4.

Atomic percentage of chemical elements presented in ISO 5832-1 stainless steel oxide layer measured by XPS.

Table 4.

Atomic percentage of chemical elements presented in ISO 5832-1 stainless steel oxide layer measured by XPS.

| Element (Atomic%) / Selected Region |

1 |

2 |

3 |

| C |

9.67 |

3.75 |

3.99 |

| Cr |

13.68 |

16.87 |

21.62 |

| Fe |

14.86 |

14.31 |

11.28 |

| Mn |

0.62 |

1,32 |

2.07 |

| Mo |

1.23 |

0.27 |

0.34 |

| N |

3.38 |

3.51 |

3.39 |

| Ni |

4.06 |

5.56 |

5.88 |

| O |

50.29 |

51.00 |

47.80 |

| P |

2.21 |

3.41 |

3.63 |

| Cr/Fe |

0.92 |

1.18 |

1.92 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).