1. Introduction

The tanning and finishing processes of leather have a significant environmental impact due to the tanning processes, moreover only 20% of animal hides are converted into leather during tanning and manufacturing, generating large amounts of solid waste. Currently, leather scraps are primarily disposed of through landfilling or incineration [

1,

2]. In response, research has been directed toward recycling and valorizing tannery solid waste as an alternative to conventional disposal methods, aligning with the principles of a circular economy. In the last years, efforts were made to upcycle leather solid waste into new products. For example, leather scraps were employed as solid fillers, flame retardants [

3], integrated into natural rubber to create leather alternatives [

4], or hydrolyzed to produce gelatin [

5] and hydrolyzed collagen [

6,

7].

The most used methods for collagen extraction rely on its solubility in acidic solutions, as well as in alkaline solutions [

8]. One of the most challenging aspects of leather hydrolysis through acid or alkaline process is the production of soluble salts, such as sodium chloride and sodium sulfate, at the end of neutralization process [

9].

Together with the increasing effort in circular economy and eco-friendly industrial processes, Additive Manufacturing (AM) is a technique that meets the requirement of sustainability and zero-waste manufacture [

10,

11]. Direct Ink Writing (DIW) is one of the most adopted AM techniques and broadens the scope of recycled feedstocks for novel applications . DIW enables the extrusion of viscous pastes, hydrogels, inks, or cross-linkable resins at room temperature through a nozzle [

12,

13]. This process allows materials to transition from a liquid-like state under shear force to a solid-like form upon deposition [

14]. DIW facilitates the reprocessing of various virgin and recycled feedstocks that are otherwise unsuitable for other extrusion-based 3D-printing techniques, such as biomass-based pastes, ceramic scraps, and fiber-reinforced composites [

15].

Among the AM techniques, LCD vat photopolymerization is a highly effective 3D printing process recognized for its exceptional dimensional precision and superior surface quality [

16]. This process uses vector scanning and mask projection methods to solidify photopolymer resin at a specific wavelength. It has attracted considerable attention from both academia and industry due to its rapid processing speed, high precision, and diverse applications in fields such as functional devices, ceramics, and biomedical engineering [

17].

Moreover, despite growing interest in AM for recycled feedstocks, the significant availability of leather scraps and byproducts remains underutilized as a potential secondary raw material for these novel zero-waste manufacturing techniques. This represents an untapped opportunity to close the loop in the tanning industry and reduce reliance on virgin resources. Based on current literature, no studies have yet explored the use of hydrolyzed leather waste AM technologies. The potential of exploitation of DIW for the upcycling of leather waste has been already investigated by authors’ previous works [

18,

19], with some limitation due to scraps aspect ratio.

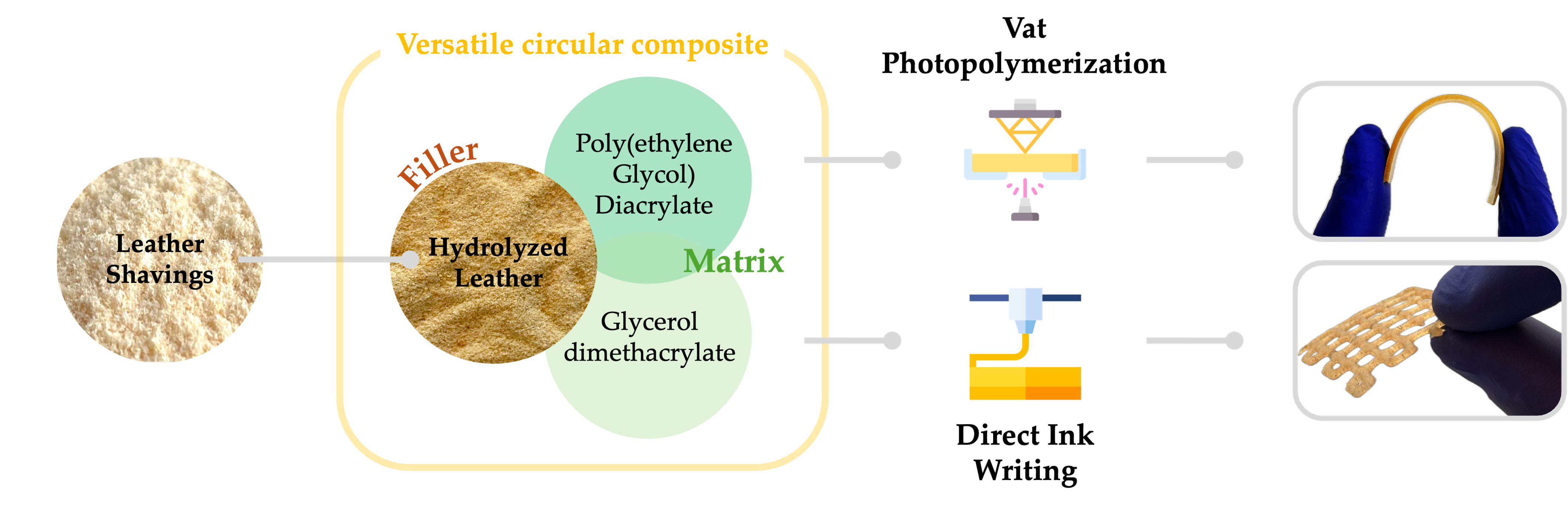

Laying on the principle of circular economy and sustainable processes, this work aims to valorize leather scraps through hydrolyzation under mild conditions and to employ leather hydrolysate as filler in a matrix composed of polyethylene-glycol-diacrylate and glycerol dimethacrylate. Leveraging chemical recycling of leather enables effective pulverization, potentially allowing for a high content of circular fillers and improved rheological properties for both DIW and LCD vat photopolymerization AM techniques.

The selection of the two monomers allows to have tunable mechanical properties together with the possibility of using materials from renewable sources [

20]. The final mechanical properties, similar to the ones of virgin leather, could allow the use of such composites for leather repair or customization, in a circular economy fashion.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Leather Shavings Hydrolysis

LS were recovered from the market with a granulometry up to 4 mm. LS hydrolysis was conducted mixing 1M sulfuric acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at a 1:6.25 (w/v) ratio for 3 hours at 90°C under mechanical stirring. The resulting suspension was vacuum filtered to remove non-hydrolyzed residues. The liquid fraction was subsequently neutralized with calcium hydroxide, and the precipitated CaSO₄ was separated through additional vacuum filtration. The hydrolyzed LS (HLS) solution was then dried at 70°C, ground into a fine powder using a jade mortar and pestle and employed as filler in composite formulations.

2.2. Composite Formulations

Composite formulations were prepared using a matrix of polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA, Mw 700, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and glycerol dimethacrylate (GDMA, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at a ratio of 80:20 (w/wMATRIX). Ethyl phenyl (2,4,6-trimethyl benzoyl) phosphinate (TPO-L, 3% w/wMATRIX, Lambson Limited, Wetherby, United Kingdom) and dicumyl peroxide (0.5% w/wMATRIX, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) were added as photoinitiator and thermal initiator, respectively.

For LCD vat photopolymerization, pulverized HLS was introduced as a filler at a concentration of 10% w/wMATRIX. For DIW, HLS was added at 10% and 20% w/wMATRIX, together with 4% w/wMATRIX fumed silica (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) as a rheological modifier. Each formulation is named according to the intended technology and the percentage of hydrolysate included. For instance, DIW10 refers to the formulation designed for DIW, containing 10% HLS filler and fumed silica.

2.3. Rheological Properties

Rheological behavior of composite formulations were evaluated by flow and strain sweep tests with a rotational rheometer Discovery HR2 (TA instrument, New Castle, DE, USA). A plate-plate geometry with a diameter of 20 mm and a 400 gap were chosen. Rheological tests were performed at 25°C.

During flow tests, the shear rate was logarithmically increased from 0.01 s−1 to 10 s−1 recording three points per decade. In the strain sweep tests, an oscillatory strain was applied from 0.01% to 1000% with a frequency of 1 Hz.

2.4. 3D printing Processes

LCD vat photopolymerization was performed with Anycubic Photon Mono 4K LCD printer (Anycubic Inc., Shenzhen, China) to produce samples for mechanical characterization. Printing parameters are reported in Error! Reference source not found.. After the 3D printing process, samples underwent thermal post-curing for 4 hours at 140°C.

Table 1.

Parameters used for vat photopolymerization of composite formulations

Table 1.

Parameters used for vat photopolymerization of composite formulations

| Parameter |

Neat Resin |

Resin + 10% HLS |

| Layer height |

0.05 mm |

0.05 mm |

| Transition layers |

6 |

6 |

| Exposure time (bottom layers) |

45 s |

60 s |

| Exposure time |

10 s |

25 s |

| Lifting speed |

60 mm/min |

60 mm/min |

| Lifting distance |

5 mm |

5mm |

3D printed structures were modeled with Fusion 360 (Autodesk, USA) software. The slicing process was carried out with the open-source slicing software PrusaSlicer 2.5.0 (Prusa Research, Prague, Czech Republic). DIW 3D printing was carried out using a custom-designed platform equipped with multiple extruders and a UV curing module (365 nm, 25 mW/cm2). Extrusion was performed at 25°C, 10 mm min-1 using a 18G tapered nozzle and 0.4 mm as layer height.

2.5. DIW Printability Evaluation

Printability tests were conducted to assess the shape fidelity of the materials. Specifically, the spreading factor (SF) was determined as the ratio of the printed filament diameter to the nozzle diameter. Measurements were performed on five filaments, with diameters recorded at seven random points along each filament.

The uniformity index (U) was calculated to evaluate the flow stability and homogeneity of the extruded material using the following equation:

where

is the average diameter of the printed filament

is the measured filament diameter and n is the number of measurements performed. Three filaments were evaluated measuring their diameter in seven random points.

The Pore Index (Pr) was evaluated to quantify the material's ability to accurately reproduce corners and sharp edges. A 30x30 mm square with 70% grid infill pattern was 3D printed. The index is defined as [

21]:

where l and A represent the perimeter and area of each pore, respectively. Seven pores were analyzed to calculate the index.

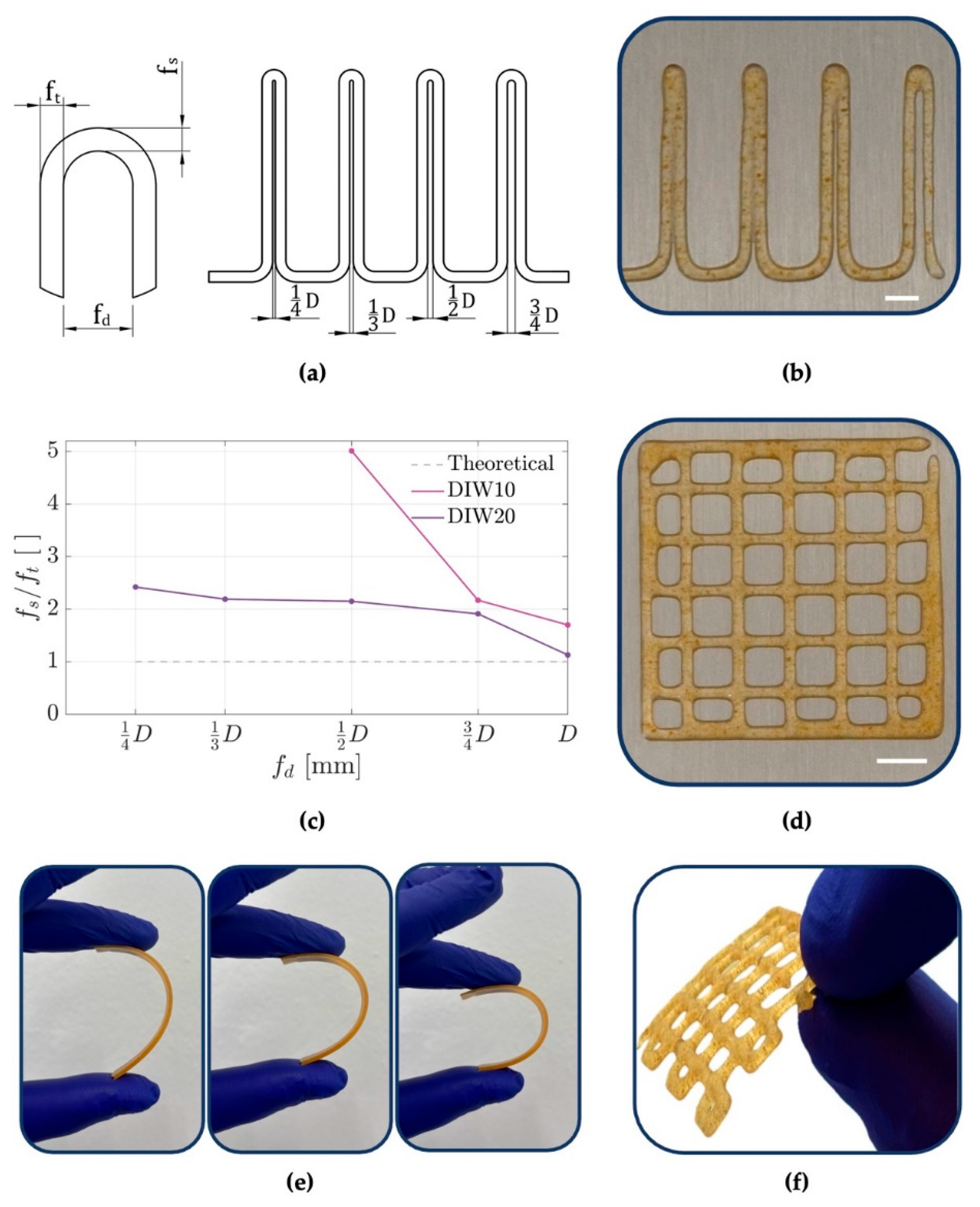

Additionally, a filament fusion test was performed by printing coil patterns with loops spaced at increasing distances (Figure 3a). The ratio f

s/f

t, where f

s is the filament diameter at the loop's peak and f

t is the average filament diameter measured at five random points, was plotted against f

d, the distance between filaments [

22]. This test assessed the material's capability to accurately replicate features such as closely spaced filaments and sharp curves.

2.6. Mechanical Characterization

Mechanical properties of composites were evaluated following the ASTM standard test method D3039/D3039M-17 [

23], using a Zwick Roell Z010 (ZwickRoell GmbH & Co. KG, Ulm, Germany) with a 10 kN cell load. Rectangular specimens with a length of 70 mm, width of 10 mm and thickness of 2 mm were tested at a loading rate of 2 mm/min with a gauge length of 40 mm, without the use of extensometers. At least three specimens for every formulation were tested. Characterization of formulations for LCD printing were performed on 3D printed samples. Characterization of formulations for DIW was performed on samples produced by casting into silicone molds and cured for 1 hour at 110°C followed by 1 hour at 140°C.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Leather Shavings Hydrolysis

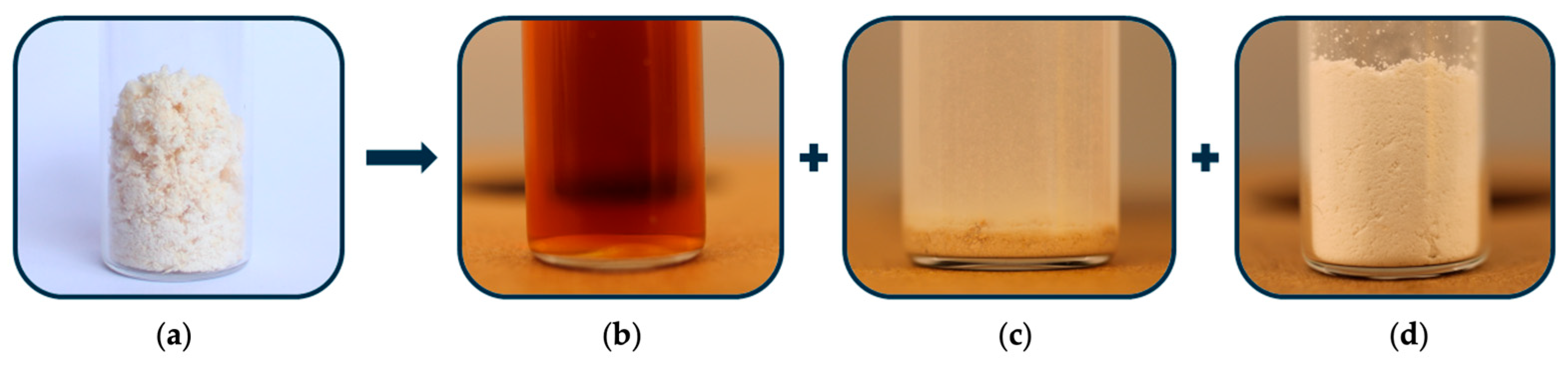

Leather hydrolysis resulted in a solution and a solid fraction which was separated through an initial vacuum filtration. The solid fraction, representing the non-hydrolyzed residues, accounted for approximately 8.7% of the initial leather mass. The solution was then neutralized with calcium hydroxide, leading to the formation of hydrated calcium sulfate. The combination of these acid and base was chosen to produce an insoluble salt that can be easily separated from the hydrolysate. The separation of soluble salts from the hydrolysate is typically challenging and may not be practical for the upcycling of industrial waste. Moreover, the resulting salt is gypsum, a valuable raw material, thereby contributing to zero-waste and circular processes. After neutralization and drying, the hydrolysate corresponded to 91.3% of the initial leather mass, demonstrating the high efficiency of the hydrolyzation process.

Figure 1.

(a) Leather shavings used for hydrolysis; products of hydrolysis: (b) liquid fraction, (c) solid residue and (d) calcium sulphate.

Figure 1.

(a) Leather shavings used for hydrolysis; products of hydrolysis: (b) liquid fraction, (c) solid residue and (d) calcium sulphate.

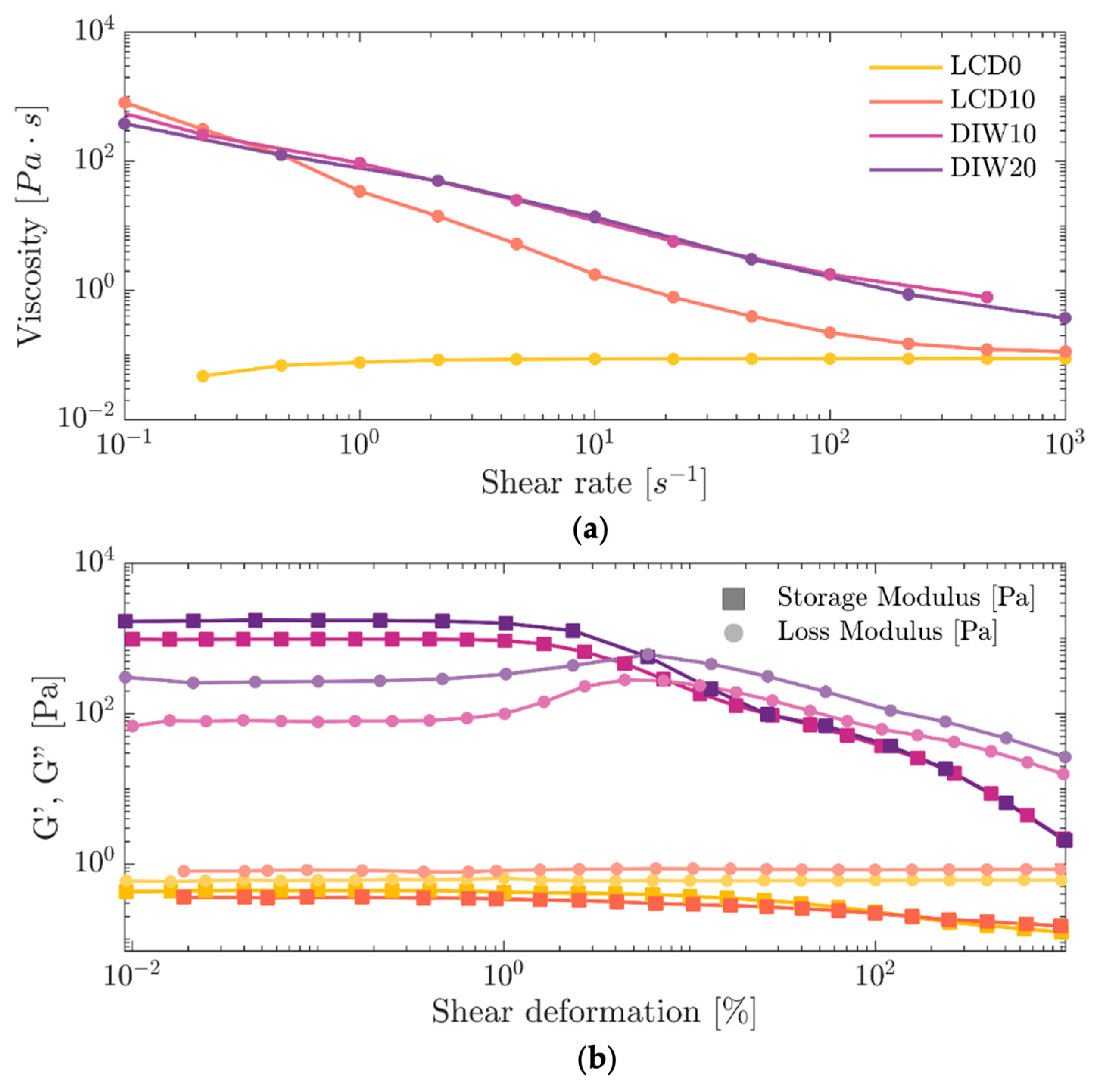

3.2. Rheological Characterization

Composite formulations were tested to evaluate their rheological behavior and suitability for the two adopted 3D printing technologies. DIW requires shear-thinning behavior and yield stress to ensure proper extrusion and shape retention. Shear thinning, observed as a decrease in viscosity with increasing shear rate, facilitates smooth flow through the nozzle during extrusion. The presence of a yield stress corresponds to a storage modulus (G’) higher than the loss modulus (G′′) at small deformations, indicating a solid-like behavior [

24]. Such behavior is essential for shape fidelity since it avoids post-extrusion flow of material. DIW10 and DIW20 exhibit decreasing viscosity with increasing shear rate (

Figure 2(a)) and have G′ values exceeding G′′ for small deformations (

Figure 2(b)). The yield point, defined as the crossover of G′ and G′′, occurs at 7.23% and 5.95% strain for DIW10 and DIW20, respectively. The corresponding yield stress values are 29 Pa and 38 Pa.

For vat photopolymerization, the material must not exhibit excessive viscosity or solid-like behavior, as this could hinder smooth movement within the resin and cause printed piece detachment. The results confirm these requirements: LCD10 exhibits higher viscosity than LCD0, which is expected due to the addition of filler (

Figure 2(a)). However, the strain sweep test shows no yield stress, as the storage modulus remains consistently lower than the loss modulus (

Figure 2(b)). This indicates that the materials do not exhibit any solid-like behavior and thus maintain continuous flow.

Additionally, the shear-thinning behavior of the LCD10 formulation mitigates the impact of its increased viscosity. During the platform's movement, the viscosity decreases under shear stress, resulting in a lower effective viscosity compared to the zero-shear viscosity.

Finally, the absence of yield stress in the LCD formulations and its presence in the DIW formulations confirmed that the addition of fumed silica as a rheological modifier was both beneficial and necessary. Its inclusion imparted the required yield stress to the DIW formulations, ensuring their suitability for the direct ink writing process.

3.3. Printability Assessment

Filaments 3D printed through DIW displayed a Spreading factor (SF,

Table 2), a dimensionless parameter dependent on printing settings, that closely matched the ideal value. Consequently, the measured filament diameters were consistent with the employed nozzle size (0.80 mm). The 3D-printed composites also showed a Uniformity index (U,

Table 2) near the ideal value, indicating the smoothness and homogeneity of the printed filaments. Additionally, the Pore Coefficient (Pr,

Table 2), which assesses the pore aspect-ratio of 3D-printed grids, was comparable to the ideal value. These results highlight the material's capability to retain its shape after extrusion, enabling the printing of squared pores

Figure 3(d). To further evaluate filament fusion, a coil with increasing loop distances (

Figure 3(a)) was 3D-printed. The plotted ratio (

Figure 3(c)) demonstrated that as the distance between loops (fd) increased, the ratio (fs/ft) approached the unitary ideal value, resulting in more uniform filament (

Figure 3(b)). Overall, these results, combined with the findings from rheological characterization, confirm the suitability of the leather hydrolysate-based composites for DIW.

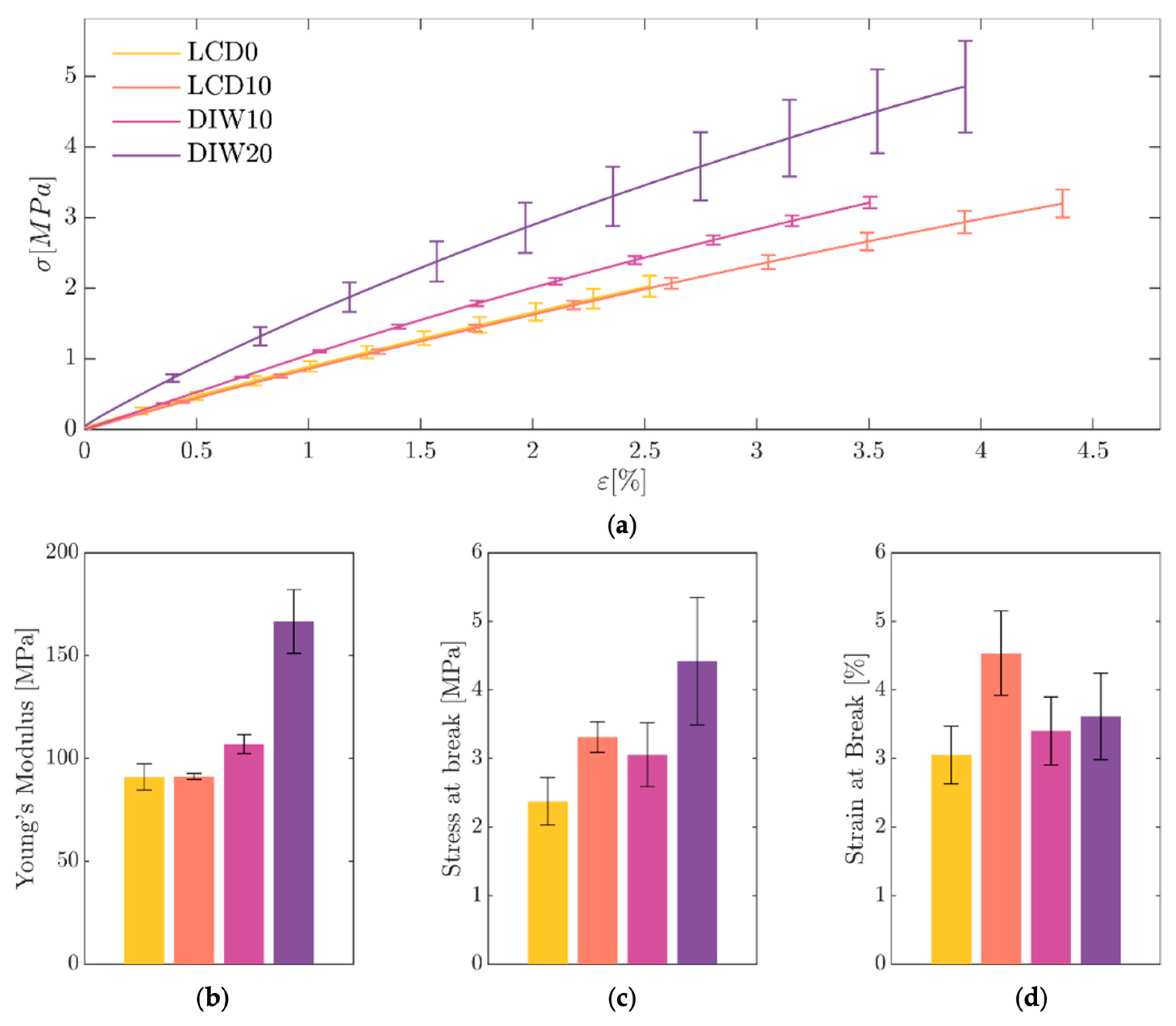

3.4. Mechanical Characterization

Samples were tested to evaluate their mechanical properties, revealing the significant influence of the filler on the composite performance. The addition of the filler improves the mechanical properties of the matrix, as evidenced by increases in modulus, stress at break, and strain at break (

Figure 4). Higher filler content further enhances the modulus and stress at break but reduces strain at break, a typical outcome when incorporating a rigid filler into a flexible matrix. Leather exhibits a modulus of 100 MPa, a strain at break of 10%, and a stress at break of 12 MPa, making the proposed material properties not far from those of leather. By adjusting the ratio of glycerol dimethacrylate, a rigid component, to polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA), a highly flexible component, it is likely possible to match the mechanical properties of leather. This suggests the material's potential for applications in leather’s defects repair and customization, as well as serving as sustainable alternative material for use in the fashion industry.

5. Conclusions

The large amount of leather solid waste spurred the optimization of processes and techniques to valorize leather scraps. In this work, acidic hydrolysis carried out under mild conditions has proven to be a promising strategy for valorizing leather scraps as filler for resin-based 3D-printable composites. The specific selection of the acid-base combination for hydrolysis and subsequent neutralization resulted in the formation of calcium sulfate, a byproduct that can be easily removed and utilized as a raw material, ensuring a zero-waste process. Leather hydrolysate addition as filler in a green matrix of polyethylene glycol diacrylate and glycerol dimethacrylate resulted in enhanced mechanical strength. Rheological tests showed that the composites exhibited viscoelastic properties suitable for DIW and vat photopolymerization 3D printing techniques. Moreover, printability assessments on structures printed with DIW displayed shape fidelity and retention. Mechanical tests demonstrated that leather hydrolysate addition improved the composite's mechanical properties, with further enhancements expected by reducing the particle size of the filler. Ball milling offers a viable and practical method for achieving this finer particle size, which could enhance the dispersion and interaction of the filler within the matrix, leading to improved composite performances. To the best of our knowledge, this work demonstrates the potential of leather shavings, hydrolyzed through a sustainable protocol, to be employed as filler in composites suitable for different additive manufacturing techniques to produce fashion-related accessories and to repair leather microscopic and macroscopic damages.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.V., L.G. and M.L.; methodology, G.V. and L.G.; validation, G.V., L.G. and M.L.; formal analysis, G.V. and L.G.; investigation, G.V. and L.G.; resources, M.L.; data curation, G.V. and L.G.; writing—original draft preparation, G.V. and L.G.; writing—review and editing, G.V. and L.G.; visualization, G.V. and L.G.; supervision, M.L.; project administration, M.L.; funding acquisition, M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was carried out within the MICS (Made in Italy – Circular and Sustainable) Extended Partnership and received funding from the European Union Next-GenerationEU (PIANO NAZIONALE DI RIPRESA E RESILIENZA (PNRR) – MISSIONE 4 COMPONENTE 2, INVESTIMENTO 1.3 – D.D. 1551.11-10-2022, PE00000004). This manuscript reflects only the authors’ views and opinions, neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be considered responsible for them.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Italian Leather Research Institute (SSIP, Pozzuoli, Naples, Italy) for kindly providing the milled glutaraldehyde-tanned leather shavings used for the experimental work. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT for the purposes of improving the readability of the manuscript. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.Graphical abstract icons were sourced from flaticon.com and were designed by Freepik.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pati, A.; Chaudhary, R.; Subramani, S. A Review on Management of Chrome-Tanned Leather Shavings: A Holistic Paradigm to Combat the Environmental Issues. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2014, 21, 11266–11282. [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, V.; Palanivel, S.; Balaraman, M. Turning Problem into Possibility: A Comprehensive Review on Leather Solid Waste Intra-Valorization Attempts for Leather Processing. J Clean Prod 2022, 367. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Olivares, G.; Rockel, D.; Calderas, F.; Schartel, B. Utilizing Leather Fibers from Industrial Wastes as Bio-Filler to Improve Flame Retardancy in Polypropylene. Joc 2024, 132, 148–160. [CrossRef]

- Raksaksri, L.; Phunpeng, V. Leather-like Composite Materials Prepared from Natural Rubber and Two Leather Wastes: Wet Blue Leather and Finished Leather. Journal of Elastomers and Plastics 2022, 54, 1254–1276. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Qiang, T.; Chen, X.; Ren, W.; Zhang, H.J. Gelatin from Leather Waste to Tough Biodegradable Packaging Film: One Valuable Recycling Solution for Waste Gelatin from Leather Industry. Waste Management 2022, 145, 10–19. [CrossRef]

- León-López, A.; Morales-Peñaloza, A.; Martínez-Juárez, V.M.; Vargas-Torres, A.; Zeugolis, D.I.; Aguirre-Álvarez, G. Hydrolyzed Collagen-Sources and Applications. Molecules 2019, 24.

- Paul, R.; Adzet, J.M.; Brouta-Agnésa, M.; Balsells, S.; Esteve, H. Hydrolyzed Collagen: A Novel Additive in Cotton and Leather Dyeing. Dyes and Pigments 2012, 94, 475–480. [CrossRef]

- Matinong, A.M.E.; Chisti, Y.; Pickering, K.L.; Haverkamp, R.G. Collagen Extraction from Animal Skin. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Hong, H.; Fan, H.; Chalamaiah, M.; Wu, J. Preparation of Low-Molecular-Weight, Collagen Hydrolysates (Peptides): Current Progress, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. Food Chem 2019, 301. [CrossRef]

- Garg, M.; Rani, R.; Meena, V.K.; Singh, S. Significance of 3D Printing for a Sustainable Environment. Materials Today Sustainability 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Vennam, S.; KN, V.; Pati, F. 3D Printed Personalized Assistive Devices: A Material, Technique, and Medical Condition Perspective. Appl Mater Today 2024, 40. [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Elsayed, H.; Franchin, G.; Colombo, P. Embedded Direct Ink Writing of Freeform Ceramic Components. Appl Mater Today 2021, 23. [CrossRef]

- van Hazendonk, L.S.; Vonk, C.F.; van Grondelle, W.; Vonk, N.H.; Friedrich, H. Towards a Predictive Understanding of Direct Ink Writing of Graphene-Based Inks. Appl Mater Today 2024, 36. [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Lowe, S.E.; Teo, A.J.T.; Dinh, T.K.; Tan, S.H.; Qin, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, Y.L.; Zhao, H. A Versatile PDMS Submicrobead/Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite Ink for the Direct Ink Writing of Wearable Micron-Scale Tactile Sensors. Appl Mater Today 2019, 16, 482–492. [CrossRef]

- Romani, A.; Rognoli, V.; Levi, M. Design, Materials, and Extrusion-Based Additive Manufacturing in Circular Economy Contexts: From Waste to New Products. Sustainability (Switzerland) 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Paral, S.K.; Lin, D.Z.; Cheng, Y.L.; Lin, S.C.; Jeng, J.Y. A Review of Critical Issues in High-Speed Vat Photopolymerization. Polymers (Basel) 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhu, L.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Shi, J.; Tang, W.; Li, N.; Yang, J. The Recent Development of Vat Photopolymerization: A Review. Addit Manuf 2021, 48. [CrossRef]

- Guida, L.; Romani, A.; Negri, D.; Cavallaro, M.; Levi, M. 3D-Printable PVA-Based Inks Filled with Leather Particle Scraps for UV-Assisted Direct Ink Writing: Characterization and Printability. Sustainable Materials and Technologies 2025, 44. [CrossRef]

- Venturelli, G.; Guida, L.; Fasani, M.G.T.; Mantero, S.; Petrini, P.; Levi, M. 3D-Printable Circular Composites as Sustainable Leather Alternative for the Valorization of Tanneries’ Solid Waste. Appl Mater Today 2025, 44, 102776. [CrossRef]

- Fantoni, A.; Ecker, J.; Ahmadi, M.; Koch, T.; Stampfl, J.; Liska, R.; Baudis, S. Green Monomers for 3D Printing: Epoxy-Methacrylate Interpenetrating Polymer Networks as a Versatile Alternative for Toughness Enhancement in Additive Manufacturing. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2023, 11, 12004–12013. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Yao, R.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, W. Effect of Bioink Properties on Printability and Cell Viability for 3D Bioplotting of Embryonic Stem Cells. Biofabrication 2016, 8. [CrossRef]

- Bagatella, S.; Guida, L.; Scagnetti, G.; Gariboldi, E.; Salina, M.; Galimberti, N.; Castoldi, L.; Cavallaro, M.; Suriano, R.; Levi, M. Tailoring Thermal Conductivity and Printability in Boron Nitride/Epoxy Nano- and Micro-Composites for Material Extrusion 3D Printing. Polymer (Guildf) 2025, 317. [CrossRef]

- Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Polymer Matrix Composite Materials 1. [CrossRef]

- Herrada-Manchón, H.; Fernández, M.A.; Aguilar, E. Essential Guide to Hydrogel Rheology in Extrusion 3D Printing: How to Measure It and Why It Matters? Gels 2023, 9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).