1. Introduction

A natural tooth and peri-implant area have similar surrounding soft tissue. The interface in which the connective tissue of the peri-implant area connects to the implant abutment represents the major difference in comparison to natural dentition [1-3]. The evaluation of the dimensions and composition of this soft tissue, namely gingivae and implant’s transmucosal regions includes studies using animal models [4-6] and humans [7-9]. Mucosal peri-implant tissue is the transmucosal part that is always at risk of infection from the oral environment. Researchers have developed an exceptional interest in exploring the impact of implant’s soft tissue attachment, particularly by modifying the chemistry and surface topography of implant abutments to enhance muco-integration [10-12]. The chairside surface modification of abutment has become more popular nowadays due to its simplistic modality [

13].

The UV treatment of the abutments follows the concept of photofuctionalization, the exposure of materials to intense UV light of specific wavelength, strength, and time to induce photocatalytic degradation of the material surface which then alter its surface chemistry and energy. The influence of photofunctionalization on osseointegration has been demonstrated by many [

14,

15,

16]. Thus, the photofunctionalization of the abutment could lead to improvement in soft tissue sealing ability, especially the formation of non-pocket mucosa surrounding dental abutments.

It is believed that the non-pocket mucosa formed at the implant tissue interface may perform better sealing than the pocket-type mucosa [

17,

18]. There are several documented advantages of subjecting the transmucosal area to surface modification, such as preserving the crystal bone, improving soft tissue attachment, minimizing adhesion of bacterial biofilms, and facilitating strong binding between the surrounding soft tissue and the implant abutment [

19]. Henceforth, effective healing of soft tissues prevents bacterial invasion, diminishes inflammatory changes, and elicits regeneration of gingival tissues. The pockets and non-pocket types represent the ability of soft tissue cells to form a tight seal [

17]. The biological seal from peri-implant mucosa is made up of hemidesmosomes attachment by epithelial tissue adjacent to the implant interface and from very minimal if present, connective tissue attachment [

20,

21]. The best methods to demonstrate the cell-cell reaction and attachment to peri-implant soft tissue are via histological evidence, like osseointegration, at the bone-implant region, and periodontal ligament attachment-tooth in periodontal regeneration procedures [

22]. The models that can be used to demonstrate the histological evidence are biopsies of human clinical studies or animal models.

It is challenging to investigate the peri-implant interface in enhancing the attachment of connective tissues in animals and humans. Removing the implant to achieve en-bloc tissue for histological examination in human subjects is also considered unethical. Meanwhile, the ultrastructural makeup of the peri-implant interface is not succinctly represented in autopsy reports. The interpretation of results obtained from experiments on animals needs to perform with caution as the immune reaction and healing responses may differ in animals and humans. These events may generate incomparable data between both species. In this case, it is indispensable to develop different models for the evaluation of peri-implant tissue attachment in response to different materials or the effect of surface modifications. The use of 3D organotypic models fabricated in-vitro has proven that this method is able to offer multiple biological endpoints for the assessment of implant-soft tissue interface [

23,

24,

25] compared to conventional monolayer cell culture [

26]. This study aims to investigate the impact of UV-mediated photofunctionalization on soft tissue contour created by a three-dimensional oral mucosal model around three various types of implant-abutment materials. Specifically, the quantification of the soft tissue attachment formed after photofunctionalization was performed using 3D-OMM. Measurement of the angle formed by the soft tissue interface contour was taken for this purpose.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample preparation

Three categories of materials were used in this experiment. These materials were (1) grade 2 commercially pure titanium (CPTi) (Edgetech Industries LLC, FL, USA), which acted as control material; (2) yttria-stabilized zirconia (YSZ), cut from Nacera® Pearl 1 (DOCERAM Medical Ceramics GmbH, Germany) using Nacera®’s cutting tools and (3) alumina-toughened zirconia (ATZ) prepared from Zeramex® P6 (Dentalpoint AG, Switzerland). Both zirconias were used as received. All the materials were prepared as discs with a dimension of 5 mm diameter and 3 mm thickness. Silicon carbide grinding paper ranging from 1800 to 2000 grit was further used to polish the CPTi in order to yield standardized smooth surface roughness (Sa) with values ranging from 0.00 to 0.5 µm / 500 nm.

The samples were randomly divided into two groups and labelled either as a non-treated group (NTx) or a UV-treated group (PTx). The samples in the UV-treated group received UV light exposure for 12 minutes using a UV light device (Therabeam® SuperOsseo, Ushio, Tokyo, Japan) (courtesy of the supplier). A mixture of UV light spectra was generated by the UV light device; amounting to an intensity of approximately 0.05 mW/cm2 (λ = 360 nm) and 2 mW/cm2 (λ = 250 nm). Only one disc of each material was placed in the device at a time for one experiment to standardize and optimize the exposure to all specimens. The experiments were carried out immediately after UV treatment.

2.2. Three-dimensional cell culture and maintenance

This study obtained ethical approval from the Research and Ethics Committee, Secretariat of Research and Innovation, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM PPI/111/8/JEP-2020-618). Oral epithelial cancer cell lines, TR146, sourced from cancer of buccal mucosa were used the keratinocyte, whereas Professor Dr Chai Wen Lin (W.L.C.) assisted in providing the human gingival fibroblasts from a High Impact Research Grant funded by the Ministry of Higher Education (UM.C/ 625/ HIR/MOHE/DENT/05). A media comprising Ham/F12 and supplemented with 0.5% of 5000 U/mL penicillin, 10% fetal bovine serum and 05000 U/mL streptomycins was used in growing the TR146s. Thereafter, the cultivated cells were incubated at room temperature (37°C) in a humidified atmosphere of 0.05 CO2. All reagents used were supplied by Gibco® (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Likewise, a confluency of 80% was reached before the dissociating the cell growth with 5 ml of 0.25% trypsin/EDTA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The dissociated cells were then resuspended until further usage.

Patients subjected the surgical extraction of third molar were used as the source of human gingival fibroblast. Healthy biopsies were collected from the patients accordingly. This step was performed by isolating the primary human gingival fibroblasts (HGFs) from the gingival biopsy, which were then cultured based on the explant method described by Chai, et al. [

17]. For optimal growth, the media were changed at two days interval, and the cells were sub-cultured to passage 5 when the cells attained a confluency of 80.0%. Upon completing the culturing and passage, the HGFs were incubated at a room temperature (37°C) and humidified environment of 5% CO

2. The HGFs were further preserved in a whole media, consisting of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium and 10% fetal bovine serum as supplement (Gibco®, Thermo Fisher Scientific Pty Ltd, VIC, Australia), Glutamax, and Gibco

® Antibiotic-Antimycotic (Gibco®, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

The development of a 3D-OMM in this study was based on the modification in a prior report employed for implant-soft tissue interface [

20]. In sum, an acellular dermal membrane (Alloderm GBR™ RTM, LifeCell Corporation, Branchburg, USA) was cut into a round shape to fit into a 12mm ring insert (Corning

® Costar

® Snapwell

™ Insert, Corning Life Sciences, Corning, NY, USA) in a 6-well plate. Both the HGF and TR146 cell suspensions were mixed and co-cultured onto the basement membrane side of the acellular dermis at a density of 500,000 for each cell. One ml of Ham/F12 mixture was added into the insert and incubated for approximately 2 hours in the incubator to allow the cells to settle onto the membrane. Approximately 5ml of Ham/F12 mixture was added into the wells of a 6-well plate afterwards. The models were incubated as described previously and the media were changed at two days interval both in the well and the insert with Ham/F12 mixture. On Day 4 of the culture, a punch hole was fabricated in the middle of the acellular dermal membrane and filled with a specimen disc. Epithelial stratification was enhanced by lifting the tissues at the air-liquid interface (ALI) after culturing for 10 days. The cells were left to grow further for 14 days in the incubator while changing the media every two days.

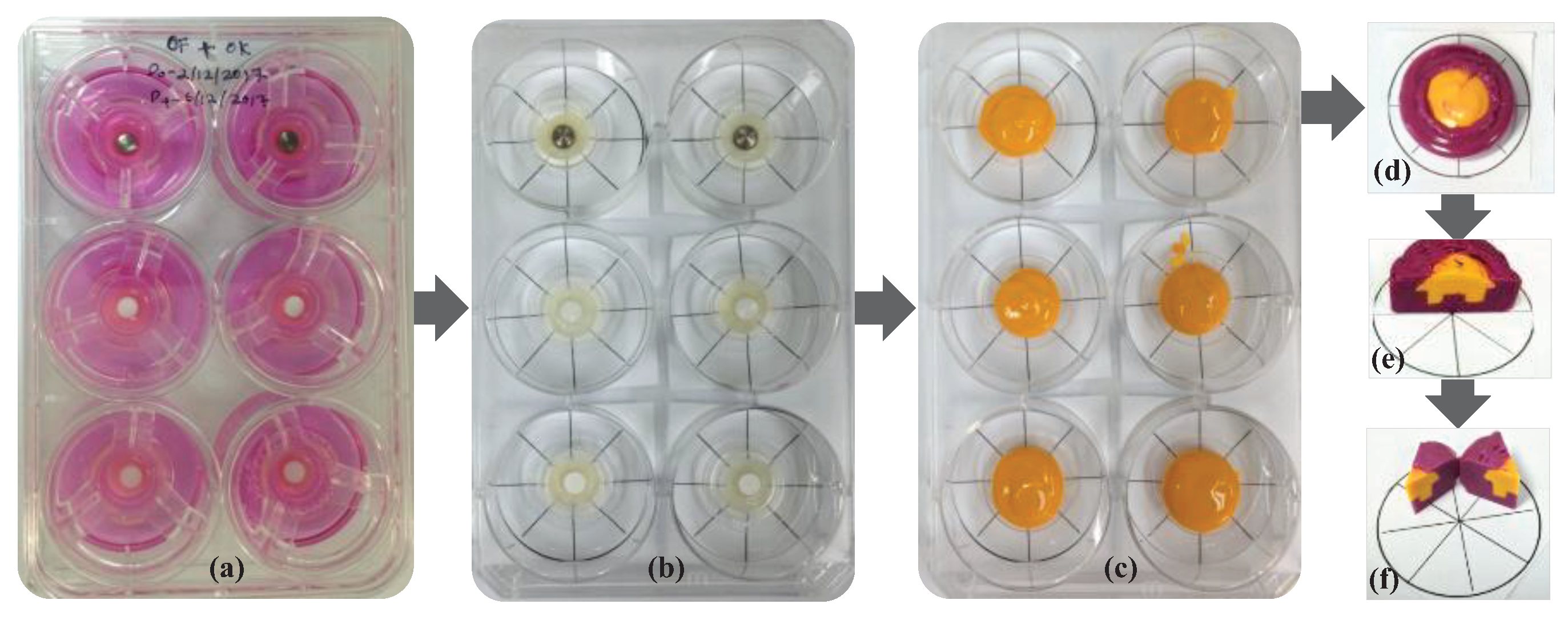

2.3. Soft tissue contour preparation and analyses

The interface contour assessment procedures were carried out on the 14

th day of tissue culture. Two different colors of impression materials used to present the model impression, particularly for the positive duplicate of the contour generated by the soft tissue. The ring insert and tissue model were lifted from the well and washed with Dulbecco’s phosphate buffer solution (Gibco

®, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) three times for five minutes. Following washing, the models were gently dried by removing all excess liquid using small tip pipettes with care taken not to touch the interface between the tissue and test materials. Silicone impression materials were injected carefully into the silicone model formed from the duplicated and dried 3D-OMM (Aquasil Ultra XLV, Dentsply Caulk International Inc., Milford, DE, USA). This procedure enables the recording of the surface and contour of the interface of the 3D-OMM and the specimens. The impression material was allowed to set according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Once hardened, the tissue model and specimen were separated from the impression. Following this, a purple regular-bodied silicone impression material (Examix™ NDS Monophase, GC America, Inc., IL, USA) was injected into the hardened yellow impression materials. After that, a scalpel blade was used to divide the duplicated blocks of silicone models into eight portions. The division was performed in four main directions: east to west, north to south, northeast to southwest and northwest to southeast. The technical procedures for impression-taking are simplified in

Figure 1.

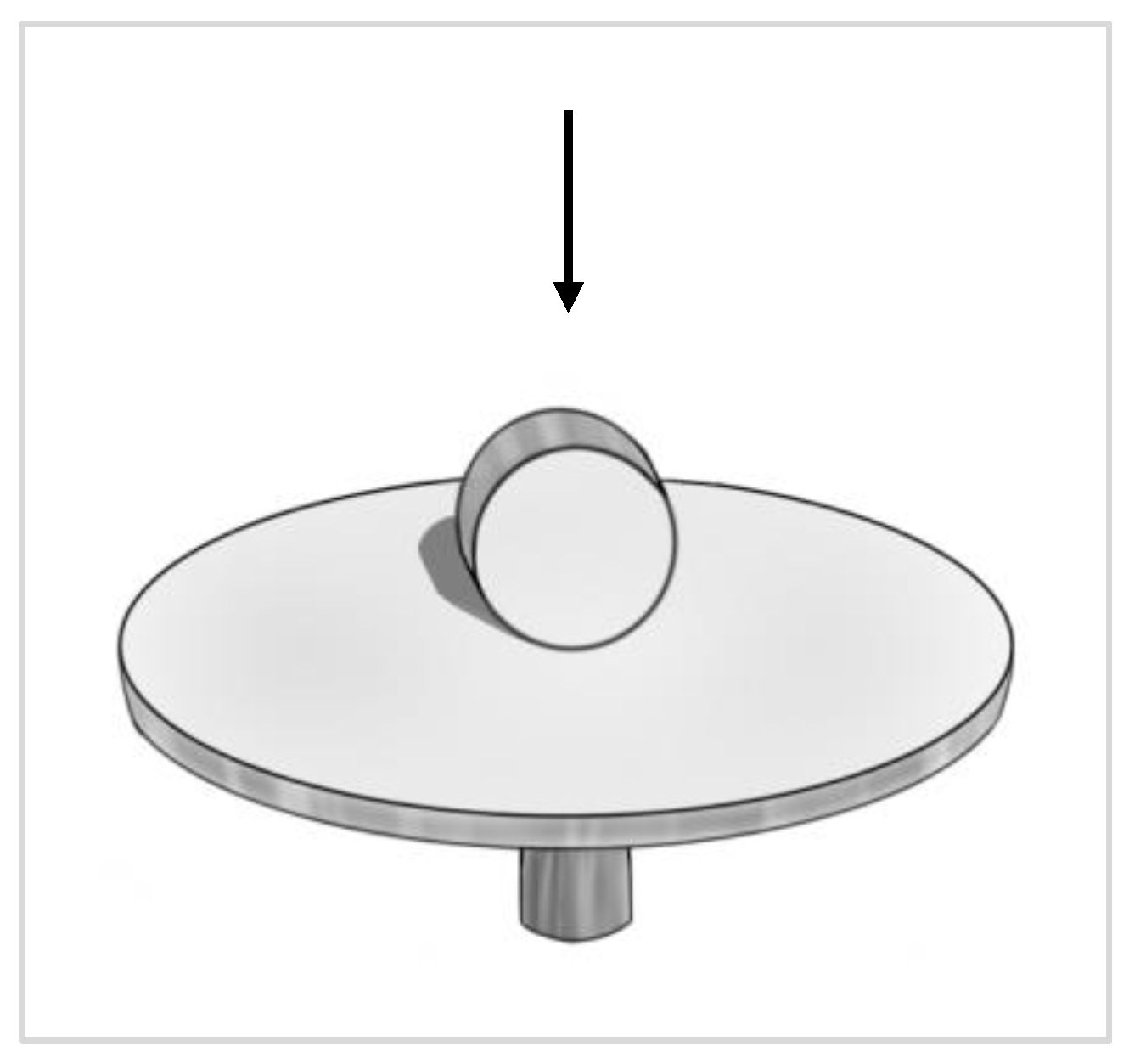

The cut surfaces were examined under a stereomicroscope (Olympus SZ2-ILST, Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The angles were studied under imaging software (Cell^D Olympus Software, Olympus, Japan). For scoring, the angles measured were categorized as θ° < 45°, 45°

< θ°

< 90° and θ° > 90°.

Figure 2.

Figure 2 depicts the angles created at the material–soft tissue interface. The following three scores represent the categories of the angle formed at the tissue surface and the interface: (i) score 1: θ° < 45° (ii) score 2: 45°

< θ°

< 90° (iii) score 3: θ° > 90°. These scores were further categorized into pocket type for score 1: θ° < 45° and non-pocket type for score 2: 45°

< θ°

< 90° and score 3: θ° > 90°. The percentage of the frequency of each score in each group was computed.

2.4. Assessment of cell morphology

For assessment of cell morphology, the specimens were carefully pulled upward from the 3D-PIMM and washed with Dulbecco’s phosphate buffer saline (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) three times for 5 minutes each to remove any loose cells. The specimens were then fixed in McDowell-Trump fixative prepared in 0.1M phosphate buffer with a pH of 7.2 at 4 °C for 24 hours. The samples were prepared for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) evaluation using the hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) technique. Briefly, after fixing, the specimens were washed with 0.1M phosphate buffer three times for 10 minutes each, followed by 2 hours postfix in 1% osmium tetroxide prepared in 0.2M phosphate buffer. Following dehydration in ascending order of ethanol concentration, the specimens were immersed in an HMDS solution for 10 minutes. The air-dried specimens were coated with gold before viewing. Care has been taken to ensure the top surface of the discs always faces upwards during the preparation.

The surface morphology and texture of the untreated materials were analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (FEI Quanta 250 FEG SEM, Quesant Instrument Corp., Agoura Hills, CA, USA). The specimens were mounted on the SEM pin stub with the side of the discs facing up in the image viewer, as shown in

Figure 3.

2.5. Ground section and staining

Additionally, the 3D-OMM units (tissue and specimens in-situ) were also prepared for the ground section. The 3D OMM units were fixed with 4% formaldehyde buffered at pH 7.0 for at least 2 h. The models were then submerged in increasing concentrations of ethanol at 50.0%, 70.0%, 90.0%, 95.0% and 100.0% for 60 minutes each in a vacuum flask. A mixture of alcohol/ methylmethacrylate (MMA) resin (Technovit 7200 VLC; Kulzer, Wehrheim, Germany) at a ratio of 70:30 was allowed to pre-infiltrate into the tissue followed by infiltration of a mixture of alcohol/MMA resin at a ratio of 50:50 for one hour each. The procedures were repeated for a mixture of alcohol/MMA resin at a ratio of 30:70 for one hour and pure (100%) MMA resin for one week. Thereafter, the specimens were implanted in new epoxy resin and polymerized using a light polymerization unit for 8 hours, and sectioned on a cutting machine (Exakt 300, Exakt Apparatebau, Norderstedt, Germany) using a diamond band saw (0.1 mm D32). The sections were polished on a grinding machine (Exakt 400CS, Exakt Apparatebau) under constant pressure and using waterproof silicon carbide papers of grit ranging from 300 to 3600 (Struers, Gothenburg, Sweden). These carbide papers assited in generating smooth and thin sections of thickness that ranged from 30 to 50 um. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) was used to stain the sections, which were then examined under light microscopy.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All the experiments were performed in triplicates. This study tested the following null hypothesis: no difference in the contour interface amongst materials regardless of UV treatment. Since the data were not numerical, the ordinal regression analysis was used to test the null hypothesis. The null hypothesis will be rejected when both the Test of Parallel Lines have p > 0.05, and Model Fitting Information and Parameter Estimates have p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Contour analyses

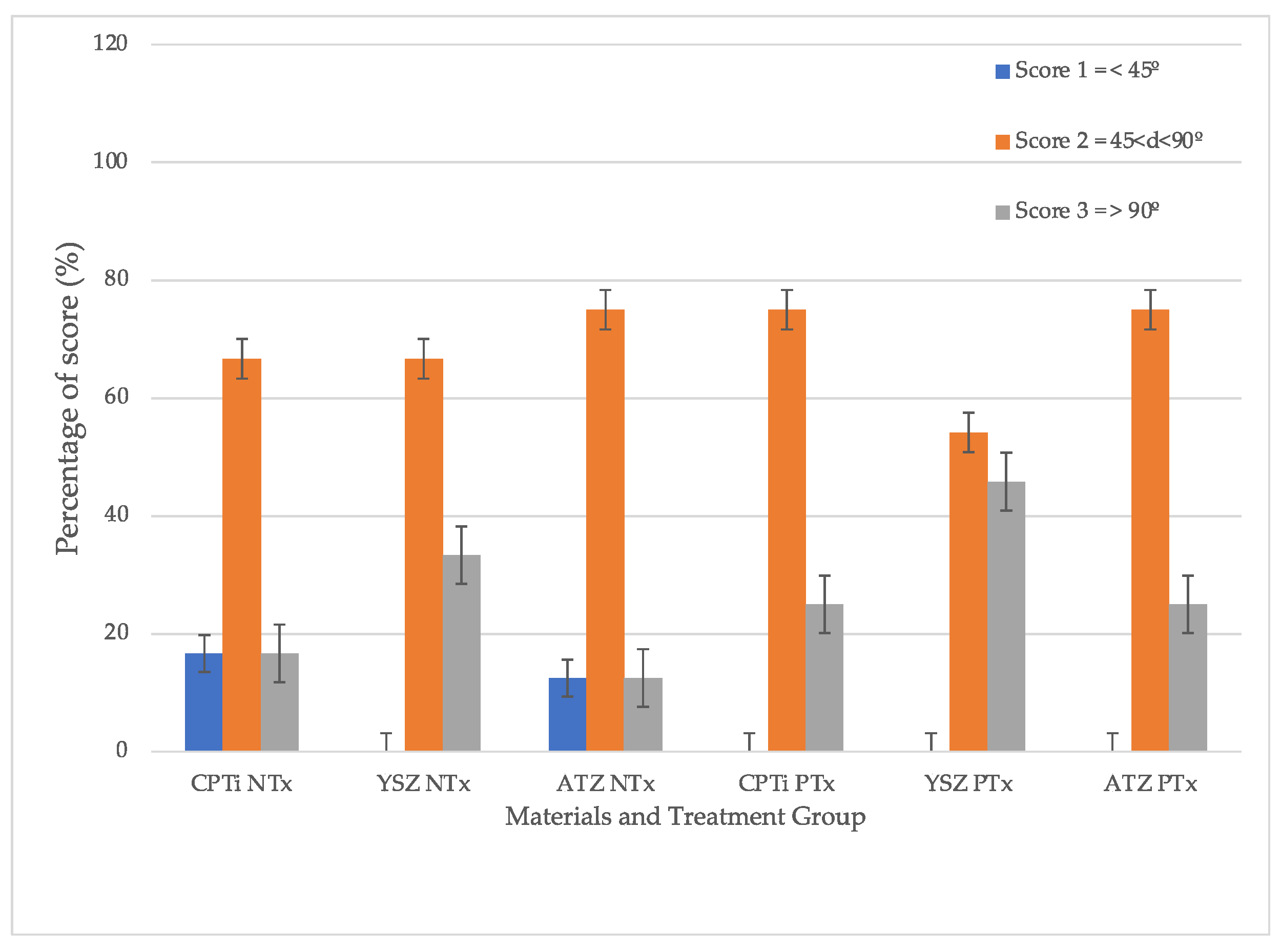

The scores were tabulated in

Figure 4. From the graph, it can be summarized that UV treatment on all surfaces of test materials led to the formation of a non-pocket type of contour. Given the p-value of 0.123, the hypothesis that no difference was present between the groups was rejected. In other words, a statistically significant difference was detected in the contour scores between the treated groups (

p = 0.001). Meanwhile, the non-treated groups tended to exhibit lower cumulative scores. The difference in non-pocket type scores in YSZ was statistically significantly higher than the rest of the materials with

p < 0.001, yet there was no difference between CPTi and ATZ (

p = 0.838). The overall material-treatment effect was also significant in the formation of non-pocket type contour.

3.2. Cell morphology

There were higher cell numbers in the treated group when observed using SEM. Although the morphology of epithelial cells and fibroblasts are difficult to distinguish through their shapes observed through SEM, some appear distinctive in features. While the epithelial cells tend to be squamous or almost rounded in shape with many blebs (lumps) and microvilli (small projections) showing a typical appearance of epithelial cancer cell [

27], the fibroblasts are more spindle and elongated in shape (as shown in

Figure 5 Figure 5 as white and red arrows respectively). Both of these cells attached well to the surface, regardless of surface treatment. However, the epithelial cells appeared to attach more on the UV-treated surfaces.

3.2. Ground section analyses

Histologically, the ground section of the soft tissue-implant interface revealed the migration of epithelial cell attachment to the implant interface. This ground section result was observed in all materials. The attachment and the proliferation of the cells at the interface resulted in the formation of pocket and non-pocket contours of the tissue. The contour of the tissue is depicted in

Figure 6.

4. Discussions

Previous

in vitro studies most used the fibroblasts on zirconia surfaces or monolayer culture of keratinocytes as the basis for evaluating the interaction between implants and soft tissues [

15,

28,

29]. The present 3D model experiment depicted more clinically relevant findings from the oral mucosa model at multiple-endpoint analyses of peri-implant tissues. The results provided more information relative to the monolayer cell culture systems. This technique was novel, straightforward, and easy to conduct for the evaluation of soft tissue surrounding the peri-implant mucosa. The combination these techniques facilitated quantitative biological analyses of how the dimension of the peri-implant tissue is affected by modifying the material’s surface [

23,

24]. This present study showed that the 3D oral mucosal model can be used to evaluate efficacy of UV photofunctionalization in improving cellular attachment of zirconia abutment of an implant. Not only this 3D model useful for assessing the toxicity of biomaterials prior to animal studies, but also it provides more meaningful clinical translation than the 2D or monolayer studies [

21,

30]. Among the endpoint outcomes that can be evaluated from this model are cytotoxicity or cell viability assays [

31,

32], ELISA test to quantify the release of proinflammatory cytokines [

33] and histology assessment to visualize the epithelial or connective tissue morphology [

34]. These 3D oral mucosal models have been compared to a 2D monolayer for the biological evaluation of glass ionomer cement and ethanol-containing solution [

34,

35]. Both studies have proved that the monolayer keratinocytes or fibroblasts are more sensitive to the tested material compared to the 3D oral mucosal models.

Maintaining peri-implant health the general final restoration aesthetics require appropriate dimensions of soft-tissue attachment to the abutment or implant surface. In order to ensure successful implantation, it is pertinent to consider the gingival margin’s position, the colour, shape, and contour of the labial gingival tissue, as well as the suitability of the interdental papillae. The quantification of the quality of the peri-implant attachment was first described by Chai, et al. [

36] in their study to compare the effect of surface treatment on peri-implant mucosa.

It is natural to find the peri-implant mucosa surrounded by a sulcus or pocket. The depth of the peri-implant sulcus dependent upon the length of an abutment. In healthy state, the sulcus sometimes is virtually non-existence due to tight attachment of the mucosa to the abutment surfaces [

37]. For instance, Chai, et al. [

17], developed a 3D oral mucosal model by utilising fibroblasts and primary human oral keratinocytes. However, it was suggested that a slightly higher score for a non-pocket type in our study is attributed to the cell-line-based model’s ability to proliferate and ascend the specimen’s surface. Raising the model to the air-liquid interface for a longer duration would elicit more stratifications of the epithelial cells [

31,

38].

Although studies on soft tissue reactions towards zirconia are numerous [

39,

40,

41,

42], the soft tissue reaction to zirconia under UV light’s influence is rather limited. To our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluated peri-implant cells in response to UV-mediated photofunctionalization zirconia surfaces, utilizing a 3-dimensional tissue engineering technology. It was discovered that the UV treatment led to more development of non-pocket types in all implant materials tested. Additionally, it was observed that YSZ displayed more favourable results of cell attachment regardless of UV surface treatment compared to CPTi and ATZ. Despite being in the smooth surface category, the surface chemistry of YSZ was different from ATZ. This difference could be a reasonable explanation for YSZ being more favourable to soft tissue cell attachment. In the quest to enhance zirconia’s bioactivity, Yang, et al. [

43] investigated human gingival fibroblasts’ behaviour on zirconia disks of different surface roughness and under the influence of UV light treatment. Their study demonstrated that human gingival fibroblast behaviour, including cell adhesion, proliferation, and collagen release was affected by UV-mediated photofunctionalization and the roughness of the zirconia surface. In this study, UV surface treatment increased cellular migration from the membrane and attached to the materials. However, epithelial cells are shown to attach more to the surface compared to fibroblasts based on the morphology of these cells.

Meanwhile, in a very recent study [

44], an exposure of zirconia to excimer UV for 10 min have shown to increase vinculin expression of L929 fibroblasts at 6- and 24-hour observations. It was also reported that the expression levels of integrin β1 and collagen type I α1 in the experimental group were enhanced compared to the control group. These observations indicate that UV light treatment might be a potential technique to be used as abutment surface modification, especially on zirconia where physical and chemical surface modifications are rather challenging.

In this study, the 3D-PIMM developed in this study was based on fibroblasts and keratinocyte cell lines only, rather than normal primary gingival keratinocytes and fibroblasts. To mimic the oral condition, the primary gingival cells should be used. The 3D dimensional structure consisted of the connective tissue collagen layer, containing fibroblasts and the distinct epithelial layer, with multi-layered stratified oral keratinocytes. However, it remains to be established which cells have a greater tendency for attachment to the material surface. Therefore, in future experiments, identification of the type of cells (fibroblasts or keratinocytes) that remain attached on different abutment surfaces after the pull test, to further explore the effect of photofunctionalization on abutment surfaces and the nature of the soft tissue attachment should be conducted.

5. Conclusions

Within the limitation of this study, it can be concluded that the UV-mediated photofunctionalization has improved the peri-implant region’s soft tissue form with the formation of non-pocket type contour evaluated using a three-dimensional peri-implant mucosal model. Zirconia (YSZ) formed a better soft tissue contour than ATZ and titanium.

Supplementary Materials

Will be provided upon request.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.C.N. and W.L.C; methodology, M.R. and W.L.C.; formal analysis, M.R.; investigation, M.R.; resources, M.R., W.C.N. and W.L.C; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.; writing—review and editing, M.R., W.C.N., R.A.O. and W.L.C.; supervision, W.C.N., R.A.O. and W.L.C.; project administration, W.C.N.; funding acquisition, M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the Research University Grant of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia under code GUP 2018-077.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Secretariat of Research and Innovation, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM PPI/111/8/JEP-2020-618), 22nd October 2020.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest and the funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Berglundh, T.; Lindhe, J. Dimension of the periimplant mucosa. Biological width revisited. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1996, 23, 971–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canullo, L.; Penarrocha Oltra, D.; Pesce, P.; Zarauz, C.; Lattanzio, R.; Penarrocha Diago, M.; Iezzi, G. Soft tissue integration of different abutment surfaces: An experimental study with histological analysis. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2021, 32, 928–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, W.L.; Razali, M.; Moharamzadeh, K.; Zafar, M.S. The hard and soft tissue interfaces with dental implants. In Dental Implants; Zafar, M.S., Khurshid, Z., Eds.; United Kingdom, 2020; pp. 173–201. [Google Scholar]

- Areid, N.; Willberg, J.; Kangasniemi, I.; Narhi, T.O. Organotypic in vitro block culture model to investigate tissue-implant interface. An experimental study on pig mandible. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2021, 32, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuhashi, A.; Ayukawa, Y.; Atsuta, I.; Rakhmatia, Y.D.; Koyano, K. Soft tissue interface with various kinds of implant abutment materials. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanauskaite, A.; Schwarz, F.; Sader, R.; Becker, J.; Obreja, K. Assessment of peri-implant tissue dimensions following surgical therapy of advanced ligature-induced peri-implantitis defects. Int. J. Implant Dent. 2021, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borie, M.; Lecloux, G.; Bosshardt, D.; Barrantes, A.; Haugen, H.J.; Lambert, F.; Bacevic, M. Peri-implant soft tissue integration in humans - influence of materials: A study protocol for a randomised controlled trial and a pilot study results. Contemp. Clin. Trials Commun. 2020, 19, 100643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevins, M.; Camelo, M.; Nevins, M.L.; Schupbach, P.; Kim, D.M. Connective tissue attachment to laser-microgrooved abutments: A human histologic case report. Int. J. Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2012, 32, 385–392. [Google Scholar]

- Pieri, F.; Aldini, N.N.; Marchetti, C.; Corinaldesi, G. Influence of implant-abutment interface design on bone and soft tissue levels around immediately placed and restored single-tooth implants: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2011, 26, 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Canullo, L.; Annunziata, M.; Pesce, P.; Tommasato, G.; Nastri, L.; Guida, L. Influence of abutment material and modifications on peri-implant soft-tissue attachment: A systematic review and meta-analysis of histological animal studies. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blazquez-Hinarejos, M.; Ayuso-Montero, R.; Jane-Salas, E.; Lopez-Lopez, J. Influence of surface modified dental implant abutments on connective tissue attachment: a systematic review. Arch. Oral Biol. 2017, 80, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corvino, E.; Pesce, P.; Mura, R.; Marcano, E.; Canullo, L. Influence of modified titanium abutment surface on peri-implant soft tissue behavior: A systematic review of in vitro studies. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2020, 35, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, M.; Ngeow, W.C.; Omar, R.A.; Chai, W.L. An integrated overview of ultraviolet technology for reversing titanium dental implant degradation: mechanism of reaction and effectivity. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, C.; Nagay, B.E.; Magno, M.B.; Maia, L.C.; Barao, V.A.R. Photofunctionalization as a suitable approach to improve the osseointegration of implants in animal models-A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesce, P.; Menini, M.; Santori, G.; Giovanni, E.; Bagnasco, F.; Canullo, L. Photo and plasma activation of dental implant titanium surfaces. A systematic review with meta-analysis of pre-clinical studies. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tominaga, H.; Matsuyama, K.; Morimoto, Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Komiya, S.; Ishidou, Y. The effect of ultraviolet photofunctionalization of titanium instrumentation in lumbar fusion: a non-randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, W.L.; Moharamzadeh, K.; Brook, I.M.; Emanuelsson, L.; Palmquist, A.; van Noort, R. Development of a novel model for the investigation of implant-soft tissue interface. J. Periodontol. 2010, 81, 1187–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, S.; Roffel, S.; Meyer, M.; Gasser, A. Biology of soft tissue repair: gingival epithelium in wound healing and attachment to the tooth and abutment surface. Eur. Cell Mater. 2019, 38, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farronato, D.; Santoro, G.; Canullo, L.; Botticelli, D.; Maiorana, C.; Lang, N.P. Establishment of the epithelial attachment and connective tissue adaptation to implants installed under the concept of "platform switching": a histologic study in minipigs. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2012, 23, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razali, M.; Ngeow, W.C.; Omar, R.A.; Chai, W.L. An in-vitro analysis of peri-implant mucosal seal following photofunctionalization of zirconia abutment materials. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, W.L.; Brook, I.M.; Palmquist, A.; van Noort, R.; Moharamzadeh, K. The biological seal of the implant-soft tissue interface evaluated in a tissue-engineered oral mucosal model. J. Royal Soc. Interface 2012, 9, 3528–3538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Md Fadilah, N.I.; Mohd Abdul Kader Jailani, M.S.; Badrul Hisham, M.A.I.; Sunthar Raj, N.; Shamsuddin, S.A.; Ng, M.H.; Fauzi, M.B.; Maarof, M. Cell secretomes for wound healing and tissue regeneration: Next generation acellular based tissue engineered products. J. Tissue Eng. 2022, 13, 20417314221114273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roffel, S.; Wu, G.; Nedeljkovic, I.; Meyer, M.; Razafiarison, T.; Gibbs, S. Evaluation of a novel oral mucosa in vitro implantation model for analysis of molecular interactions with dental abutment surfaces. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2019, 21, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, E.; AlQobaly, L.; Shaikh, Z.; Franklin, K.; Moharamzadeh, K. Implant soft-tissue attachment using 3D oral mucosal models - A pilot study. Dent. J. (Basel) 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakulpaptong, W.; Clairmonte, I.A.; Blackstone, B.N.; Leblebicioglu, B.; Powell, H.M. 3D engineered human gingiva fabricated with electrospun collagen scaffolds provides a platform for in vitro analysis of gingival seal to abutment materials. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0263083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat-Baharin, N.H.; Razali, M.; Mohd-Said, S.; Syarif, J.; Muchtar, A. Influence of alloying elements on cellular response and in-vitro corrosion behavior of titanium-molybdenum-chromium alloys for implant materials. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2020, 64, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heremans, H.; Billiau, A.; Mulier, J.C.; de Somer, P. In vitro cultivation of human tumor issues II. Morphological and virological characterization of the three cell lines. Oncology 1978, 35, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, M.; Corti, A.; Dorocka-Bobkowska, B.; Pompella, A. Positive effects of UV-photofunctionalization of titanium oxide surfaces on the survival and differentiation of osteogenic precursor cells—An in vitro study. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkunas, V.; Borusevicius, R.; Balciunas, E.; Jasinskyte, U.; Alksne, M.; Simoliunas, E.; Zlatev, S.; Ivanova, V.; Bukelskiene, V.; Mijiritsky, E. The effect of UV treatment on surface contact angle, fibroblast cytotoxicity, and proliferation with two types of zirconia-based ceramics. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongari-Bagtzoglou, A.; Kashleva, H. Development of a highly reproducible three-dimensional organotypic model of the oral mucosa. Nat. Protoc. 2006, 1, 2012–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dongari-Bagtzoglou, A.; Kashleva, H. Development of a novel three-dimensional in vitro model of oral Candida infection. Microb. Pathog. 2006, 40, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharamzadeh, K.; Brook, I.M.; Scutt, A.M.; Thornhill, M.H.; Van Noort, R. Mucotoxicity of dental composite resins on a tissue-engineered human oral mucosal model. J. Dent. 2008, 36, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasarudin, N.A.; Razali, M.; Goh, V.; Chai, W.L.; Muchtar, A. Expression of Interleukin-1beta and Histological Changes of the Three-Dimensional Oral Mucosal Model in Response to Yttria-Stabilized Nanozirconia. Materials (Basel) 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moharamzadeh, K.; Franklin, K.L.; Brook, I.M.; van Noort, R. Biologic assessment of antiseptic mouthwashes using a three-dimensional human oral mucosal model. J. Periodontol. 2009, 80, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharamzadeh, K.; Van Noort, R.; Brook, I.M.; Scutt, A.M. Cytotoxicity of resin monomers on human gingival fibroblasts and HaCaT keratinocytes. Dent. Mater. 2007, 23, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chai, W.L.; Moharamzadeh, K.; van Noort, R.; Emanuelsson, L.; Palmquist, A.; Brook, I.M. Contour analysis of an implant-soft tissue interface. J. Periodontal Res. 2013, 48, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renvert, S.; Persson, G.R.; Pirih, F.Q.; Camargo, P.M. Peri-implant health, peri-implant mucositis, and peri-implantitis: Case definitions and diagnostic considerations. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, S278–S285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, L.R.; Colley, H.E.; Ong, J.; Panagakos, F.; Masters, J.G.; Trivedi, H.M.; Murdoch, C.; Whawell, S. Development and characterization of In vitro human oral mucosal equivalents derived from immortalized oral keratinocytes. Tissue Eng. Part C Methods 2016, 22, 1108–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, M.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, M.; Yang, Y.; Liu, X.; Tan, J. Biofunctionalization of zirconia with cell-adhesion peptides via polydopamine crosslinking for soft tissue engineering: effects on the biological behaviors of human gingival fibroblasts and oral bacteria. RSC Advances 2020, 10, 6200–6212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riivari, S.; Shahramian, K.; Kangasniemi, I.; Willberg, J.; Narhi, T.O. TiO2-modified zirconia surface improves epithelial cell attachment. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2019, 34, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz-Martín, I.; Sanz-Sánchez, I.; Carrillo de Albornoz, A.; Figuero, E.; Sanz, M. Effects of modified abutment characteristics on peri-implant soft tissue health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2018, 29, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zheng, M.; Liao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, H.; Tan, J. Different behavior of human gingival fibroblasts on surface modified zirconia: a comparison between ultraviolet (UV) light and plasma. Dent. Mater. J. 2019, 38, 756–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Liu, X.; Zheng, M.; Yang, J.; Tan, J. Ultraviolet light-treated zirconia with different roughness affects function of human gingival fibroblasts in vitro: the potential surface modification developed from implant to abutment. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2015, 103, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akashi, Y.; Shimoo, Y.; Hashiguchi, H.; Nakajima, K.; Kokubun, K.; Matsuzaka, K. Effects of excimer laser treatment of zirconia disks on the adhesion of L929 fibroblasts. Materials (Basel) 2022, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).