Submitted:

09 July 2025

Posted:

10 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Tenosan® Preparation

2.2. Cells Cultures

2.3. Cytotoxicity Assay

2.4. Tendinopathy In Vitro Model

2.5. Cells Treatment

2.6. Detection of Collagen, VEGF and NO Levels

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

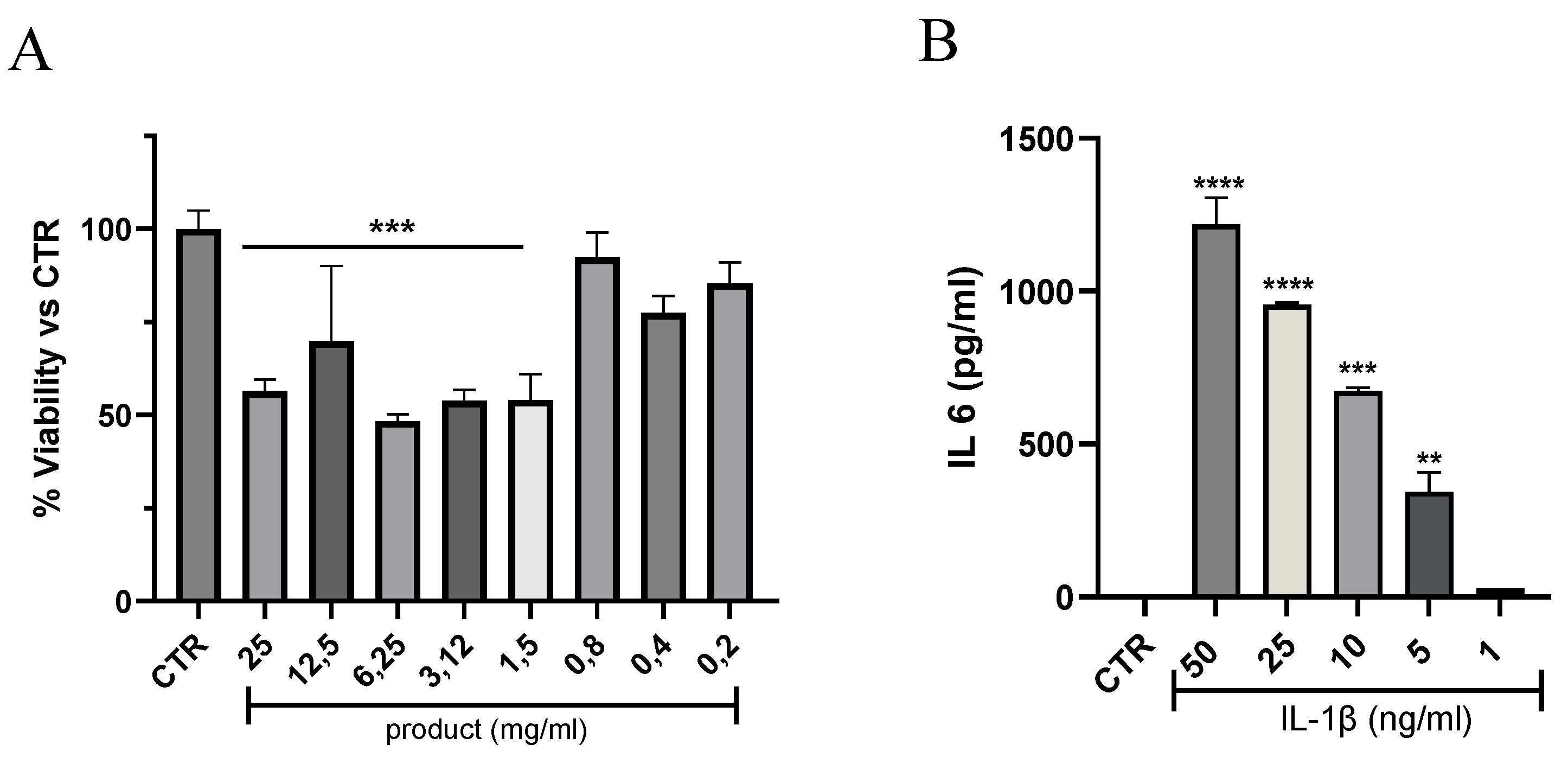

3.1. Effects of Tenosan® on Tenocyte Viability and Tendinopathy In Vitro Model

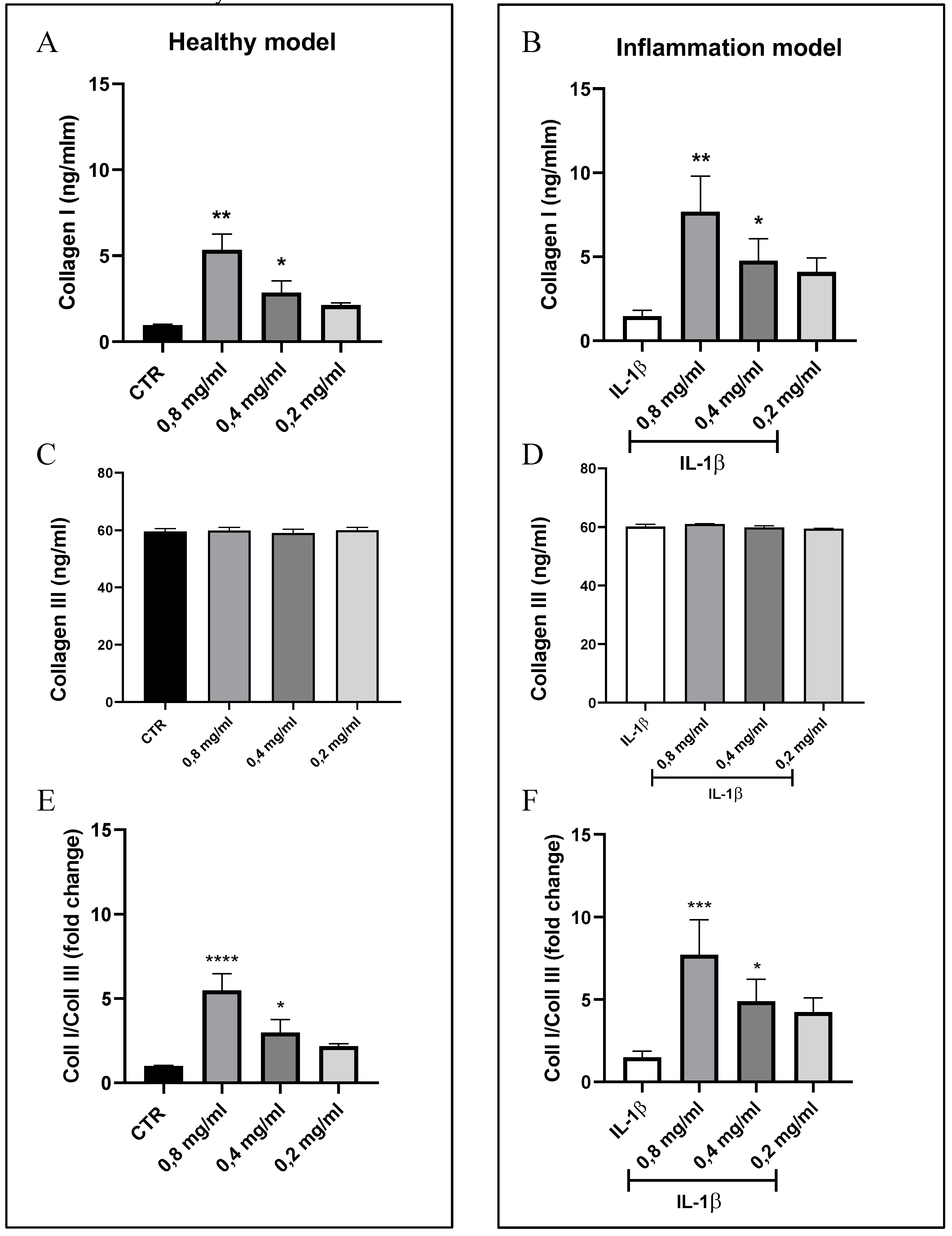

3.2. Quantification of Collagen I and III Levels

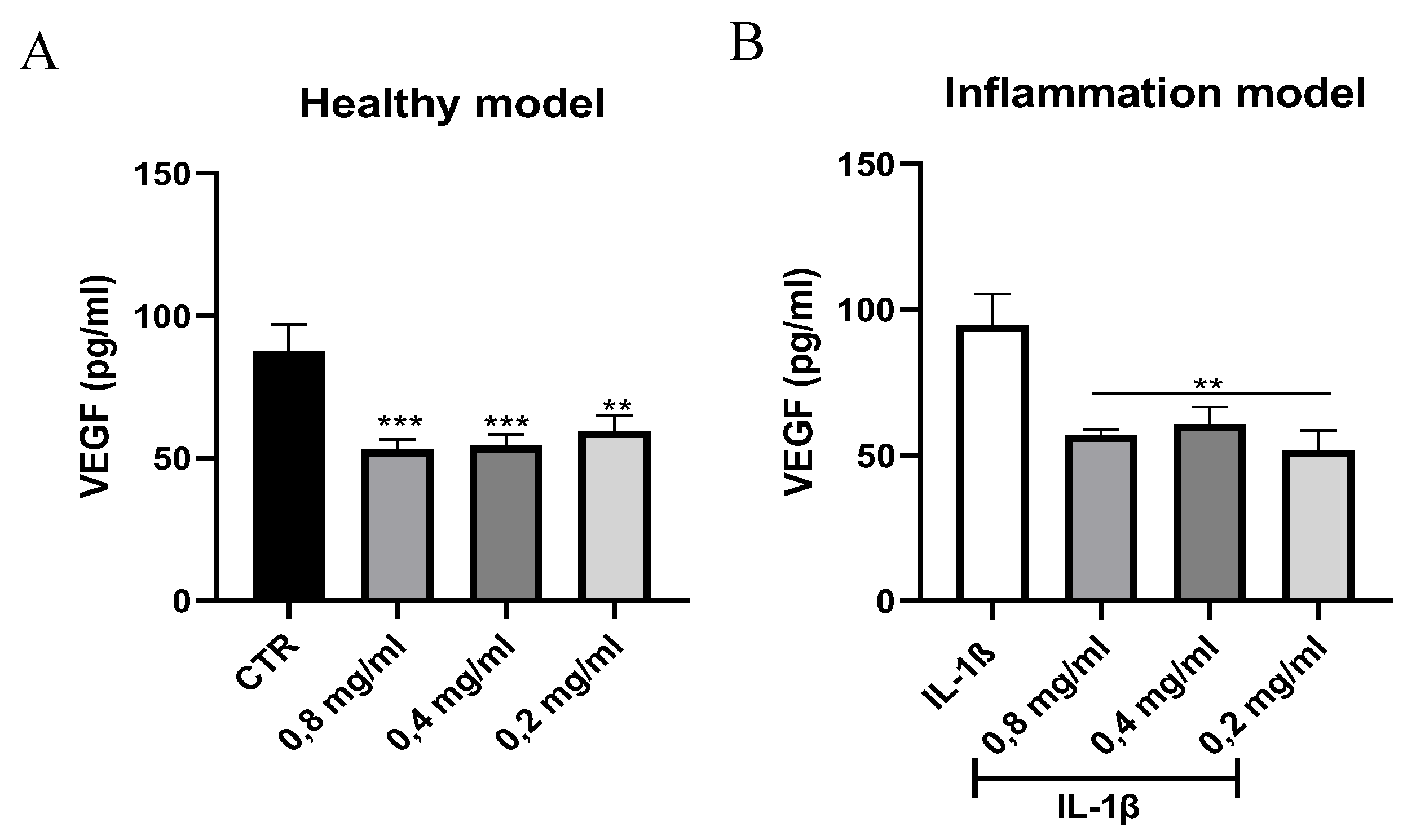

3.3. Quantification of VEGF Levels

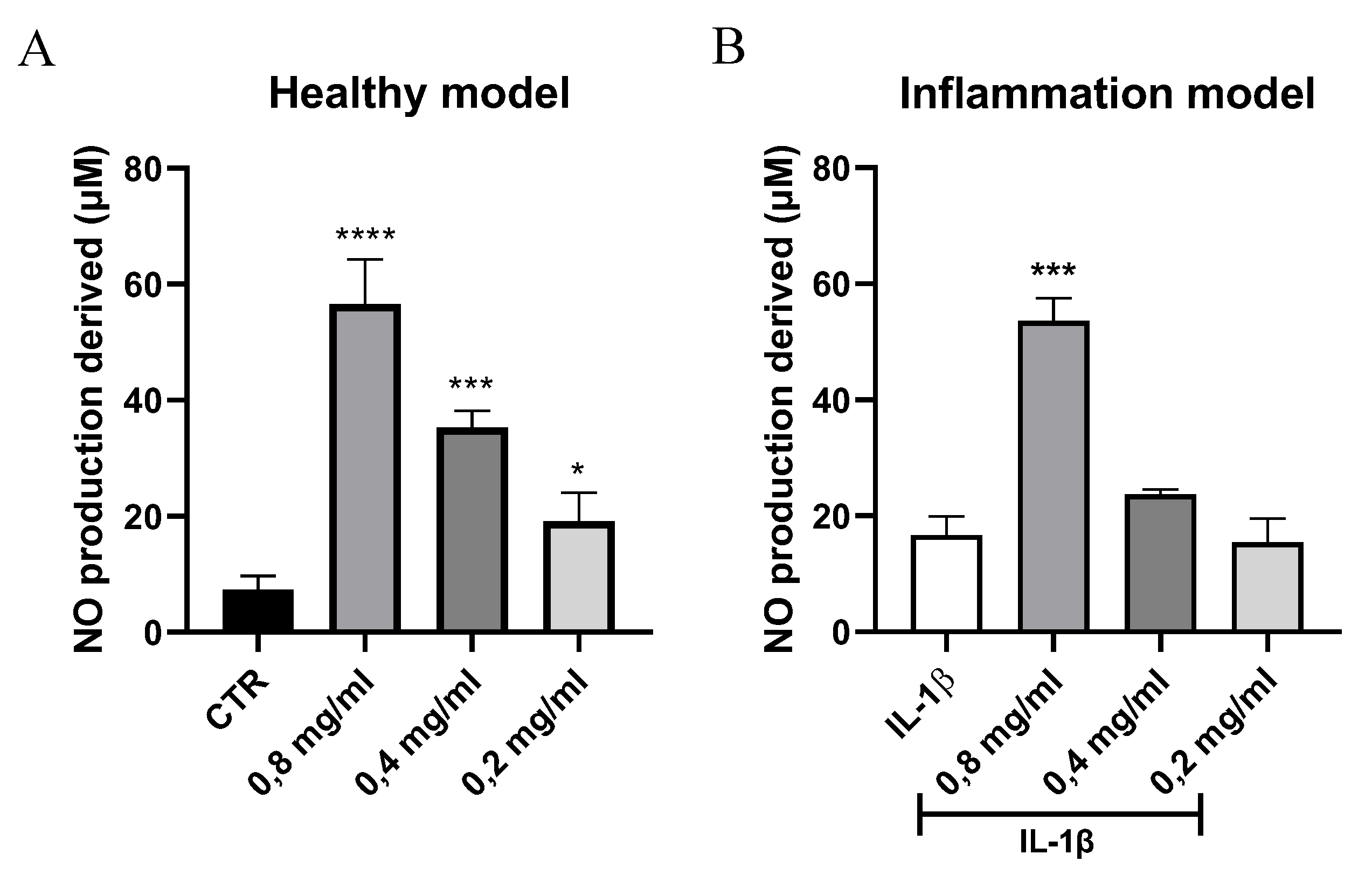

3.4. Quantification of Nitric Oxide Levels

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- C. T. Thorpe and H. R. C. Screen, ‘Tendon Structure and Composition’, Adv Exp Med Biol, vol. 920, pp. 3–10, 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. Zdzieblik, S. Oesser, M. W. Baumstark, A. Gollhofer, and D. König, ‘Collagen peptide supplementation in combination with resistance training improves body composition and increases muscle strength in elderly sarcopenic men: A randomised controlled trial’, British Journal of Nutrition, vol. 114, no. 8, pp. 1237–1245, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- N. Maffulli, F. Cuozzo, F. Migliorini, and F. Oliva, ‘The tendon unit: biochemical, biomechanical, hormonal influences’, J Orthop Surg Res, vol. 18, no. 1, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. L. Millar, G. A. C. Murrell, and I. B. Mcinnes, ‘Inflammatory mechanisms in tendinopathy - towards translation’, Nat Rev Rheumatol, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 110–122, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. L. Millar et al., ‘Tendinopathy’, Nat Rev Dis Primers, vol. 7, no. 1, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. J. F. Dean, P. Gettings, S. G. Dakin, and A. J. Carr, ‘Are inflammatory cells increased in painful human tendinopathy? A systematic review’, Br J Sports Med, vol. 50, no. 4, pp. 216–220, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. Abate et al., ‘Pathogenesis of tendinopathies: inflammation or degeneration?’, Arthritis Res Ther, vol. 11, no. 3, p. 235, Jun. 2009. [CrossRef]

- N. L. Millar, G. A. C. Murrell, and I. B. Mcinnes, ‘Inflammatory mechanisms in tendinopathy - towards translation’, Nat Rev Rheumatol, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 110–122, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. G. Dakin, J. Dudhia, and R. K. W. Smith, ‘Resolving an inflammatory concept: the importance of inflammation and resolution in tendinopathy’, Vet Immunol Immunopathol, vol. 158, no. 3–4, pp. 121–127, Apr. 2014. [CrossRef]

- G. Riley, ‘Tendinopathy--from basic science to treatment’, Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 82–89, Feb. 2008. [CrossRef]

- T. Molloy, Y. Wang, and G. A. C. Murrell, ‘The roles of growth factors in tendon and ligament healing’, Sports Medicine, vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 381–394, 2003. [CrossRef]

- H. Tempfer et al., ‘Bevacizumab Improves Achilles Tendon Repair in a Rat Model’, Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry, vol. 46, no. 3, pp. 1148–1158, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- A. Notarnicola, V. Pesce, G. Vicenti, S. Tafuri, M. Forcignanò, and B. Moretti, ‘SWAAT study: Extracorporeal shock wave therapy and arginine supplementation and other nutraceuticals for insertional achilles tendinopathy’, Sep. 2012. [CrossRef]

- B. M. Andres and G. A. C. Murrell, ‘Treatment of tendinopathy: what works, what does not, and what is on the horizon’, Clin Orthop Relat Res, vol. 466, no. 7, pp. 1539–1554, 2008. [CrossRef]

- N. Maffulli, U. G. Longo, and V. Denaro, ‘Novel approaches for the management of tendinopathy’, J Bone Joint Surg Am, vol. 92, no. 15, pp. 2604–2613, Nov. 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. Scarselli, E. Torricelli, and P. Pasquetti, ‘Trattamento combinato nella tendinopatia calcifica di spalla’, 2012.

- S. Gumina, D. Passaretti, M. D. Gurzì, and V. Candela, ‘Arginine L-alpha-ketoglutarate, methylsulfonylmethane, hydrolyzed type i collagen and bromelain in rotator cuff tear repair: A prospective randomized study’, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Di Gesù and D. Tiso, ‘The multimodal management of patients with tendinopathy: percutaneous electrolysis, nutraceuticals and lifestyle – report from the 2022 I.S.Mu.L.T. Congress’, Drugs Context, vol. 12, pp. 1–5, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Iwai et al., ‘Identification of food-derived collagen peptides in human blood after oral ingestion of gelatin hydrolysates’, J Agric Food Chem, vol. 53, no. 16, pp. 6531–6536, Aug. 2005. [CrossRef]

- I. Burton and A. McCormack, ‘Nutritional Supplements in the Clinical Management of Tendinopathy: A Scoping Review’, J Sport Rehabil, vol. 32, no. 5, pp. 493–504, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. León-López, A. Morales-Peñaloza, V. M. Martínez-Juárez, A. Vargas-Torres, D. I. Zeugolis, and G. Aguirre-Álvarez, ‘Hydrolyzed Collagen—Sources and Applications’, Molecules, vol. 24, no. 22, p. 4031, 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. S. Willoughby, T. Boucher, J. Reid, G. Skelton, and M. Clark, ‘Effects of 7 days of arginine-alpha-ketoglutarate supplementation on blood flow, plasma L-arginine, nitric oxide metabolites, and asymmetric dimethyl arginine after resistance exercise’, Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 291–299, 2011. [CrossRef]

- L. S. Kim, L. J. Axelrod, P. Howard, N. Buratovich, and R. F. Waters, ‘Efficacy of methylsulfonylmethane (MSM) in osteoarthritis pain of the knee: A pilot clinical trial’, Osteoarthritis Cartilage, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 286–294, Mar. 2006. [CrossRef]

- T. Clifford, G. Howatson, D. J. West, and E. J. Stevenson, ‘The Potential Benefits of Red Beetroot Supplementation in Health and Disease’, Nutrients, vol. 7, no. 4, p. 2801, Apr. 2015. [CrossRef]

- G. Deley, D. Guillemet, F. A. Allaert, and N. Babault, ‘An acute dose of specific grape and apple polyphenols improves endurance performance: A randomized, crossover, double-blind versus placebo controlled study’, Nutrients, vol. 9, no. 8, Aug. 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. Min et al., ‘Restoration of Cellular Proliferation and Characteristics of Human Tenocytes by Vitamin D’, Journal of Orthopaedic Research, vol. 37, no. 10, pp. 2241–2248, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. N. DePhillipo, Z. S. Aman, M. I. Kennedy, J. P. Begley, G. Moatshe, and R. F. LaPrade, ‘Efficacy of Vitamin C Supplementation on Collagen Synthesis and Oxidative Stress After Musculoskeletal Injuries: A Systematic Review’, Orthop J Sports Med, vol. 6, no. 10, p. 2325967118804544, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. J. Padayatty et al., ‘Vitamin C as an Antioxidant: Evaluation of Its Role in Disease Prevention’, J Am Coll Nutr, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 18–35, Feb. 2003. [CrossRef]

- C. Hoppe, M. Freuding, J. Büntzel, K. Münstedt, and J. Hübner, ‘Clinical efficacy and safety of oral and intravenous vitamin C use in patients with malignant diseases’, J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, vol. 147, no. 10, p. 3025, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. K. Kang et al., ‘Vitamin C Improves Therapeutic Effects of Adipose-derived Stem Cell Transplantation in Mouse Tendonitis Model’, In Vivo (Brooklyn), vol. 31, no. 3, p. 343, May 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Gallorini, C. Antonetti Lamorgese Passeri, A. Cataldi, A. C. Berardi, and L. Osti, ‘Hyaluronic Acid Alleviates Oxidative Stress and Apoptosis in Human Tenocytes via Caspase 3 and 7’, Int J Mol Sci, vol. 23, no. 15, p. 8817, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Shaw, A. Lee-Barthel, M. L. R. Ross, B. Wang, and K. Baar, ‘Vitamin C–enriched gelatin supplementation before intermittent activity augments collagen synthesis’, Am J Clin Nutr, vol. 105, no. 1, p. 136, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- O. Evrova, D. Kellenberger, M. Calcagni, V. Vogel, and J. Buschmann, ‘Supporting Cell-Based Tendon Therapy: Effect of PDGF-BB and Ascorbic Acid on Rabbit Achilles Tenocytes In Vitro’, Int J Mol Sci, vol. 21, no. 2, p. 458, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. C. Noriega-gonzález, F. Drobnic, A. Caballero-garcía, E. Roche, D. Perez-valdecantos, and A. Córdova, ‘Effect of Vitamin C on Tendinopathy Recovery: A Scoping Review’, Nutrients, vol. 14, no. 13, p. 2663, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- I. Capparucci, A. Federici, C. Bartolucci, M. Valentini, V. Vita, and I. Testa, ‘Terapia del morbo di Duplay con associazione di EDTA calcico per via intrarticolare e supplementazione orale plurifattoriale’, 2013.

- M. Marzagalli et al., ‘Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of a New Mixture of Vitamin C, Collagen Peptides, Resveratrol, and Astaxanthin in Tenocytes: Molecular Basis for Future Applications in Tendinopathies’, Mediators Inflamm, vol. 2024, p. 5273198, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. D. S. Antonio, O. Jacenko, A. Fertala, and J. P. R. O. Orgel, ‘Collagen Structure-Function Mapping Informs Applications for Regenerative Medicine’, Bioengineering 2021, Vol. 8, Page 3, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 3, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. Li, N. Chi, R. A. C. Rathnayake, and R. Wang, ‘Distinctive roles of fibrillar collagen I and collagen III in mediating fibroblast-matrix interaction: A nanoscopic study’, Biochem Biophys Res Commun, vol. 560, pp. 66–71, Jun. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. W. Volk, Y. Wang, E. A. Mauldin, K. W. Liechty, and S. L. Adams, ‘Diminished Type III Collagen Promotes Myofibroblast Differentiation and Increases Scar Deposition in Cutaneous Wound Healing’, Cells Tissues Organs, vol. 194, no. 1, pp. 25–37, Jun. 2011. [CrossRef]

- X. Liu et al., ‘The Role of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Tendon Healing’, Oct. 25, 2021, Frontiers Media S.A. [CrossRef]

- A. R. Bokhari and G. A. C. Murrell, ‘The role of nitric oxide in tendon healing’, J Shoulder Elbow Surg, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 238–244, Feb. 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen et al., ‘MOFs-Based Nitric Oxide Therapy for Tendon Regeneration’, Nanomicro Lett, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 1–17, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Singh, V. Rai, and D. K Agrawal, ‘Regulation of Collagen I and Collagen III in Tissue Injury and Regeneration’, Cardiol Cardiovasc Med, vol. 07, no. 01, 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Liu et al., ‘The Role of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor in Tendon Healing’, Oct. 25, 2021, Frontiers Media S.A. [CrossRef]

- G. A. C. Murrell, ‘Nitric oxide and tendon healing’, 2006. [CrossRef]

- G. A. C. Murrell et al., ‘Modulation of tendon healing by nitric oxide’, Inflammation Research, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 19–27, 1997. [CrossRef]

- G. A. C. Murrell, ‘Oxygen free radicals and tendon healing’, J Shoulder Elbow Surg, vol. 16, no. 5 SUPPL., Sep. 2007. [CrossRef]

- W. Xia, Z. Szomor, Y. Wang, and G. A. C. Murrell, ‘Nitric oxide enhances collagen synthesis in cultured human tendon cells’, Journal of Orthopaedic Research, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 159–172, Feb. 2006. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Cohen and T. Adachi, ‘Nitric-Oxide-Induced Vasodilatation: Regulation by Physiologic S-Glutathiolation and Pathologic Oxidation of the Sarcoplasmic Endoplasmic Reticulum Calcium ATPase’, Trends Cardiovasc Med, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 109–114, May 2006. [CrossRef]

- B. Tong and A. Barbul, ‘Cellular and Physiological Effects of Arginine’, Mini-Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry, vol. 4, no. 8, pp. 823–832, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).