Submitted:

09 July 2025

Posted:

10 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

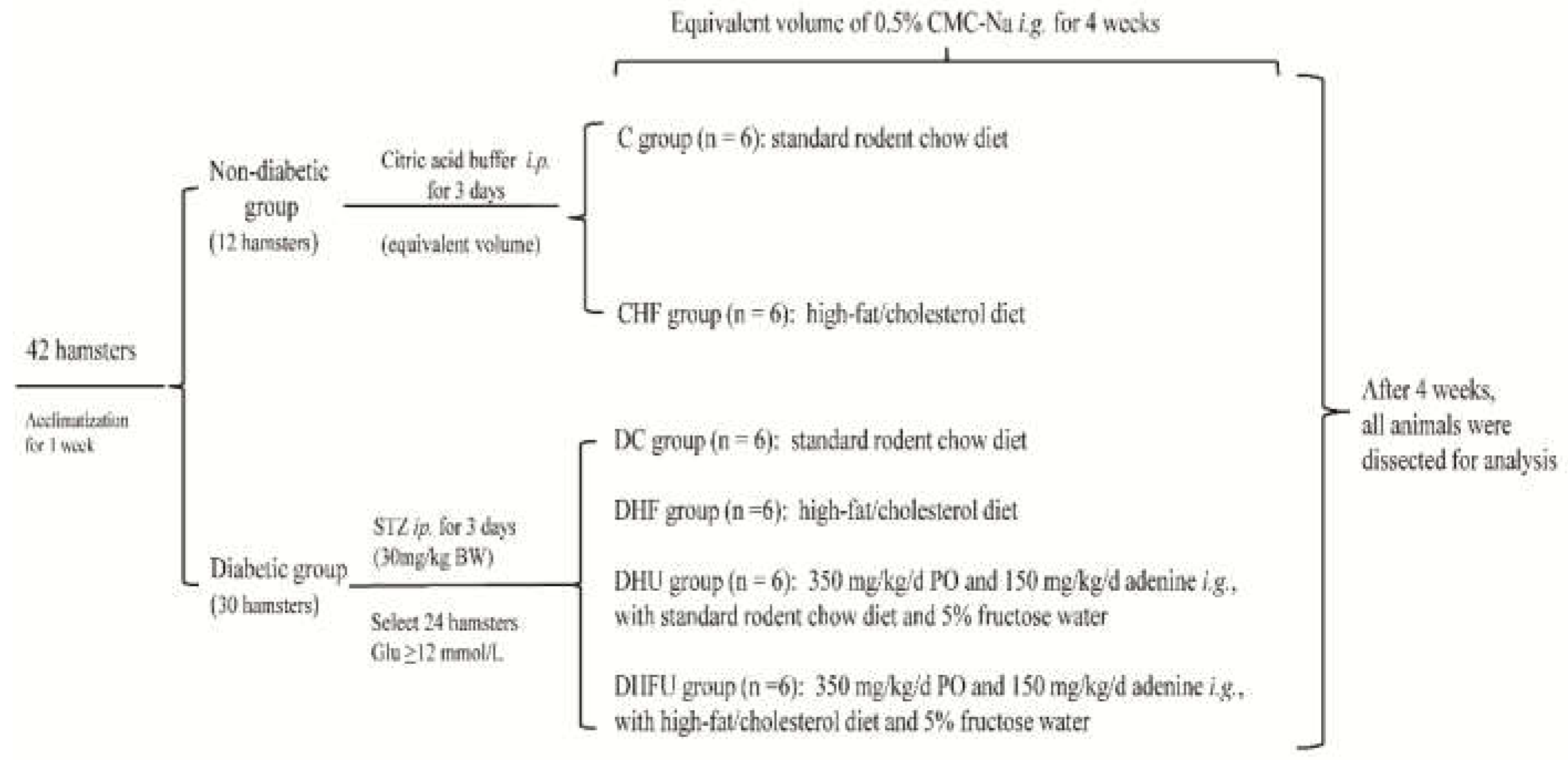

2.1. Animal Experimental Design

2.2. Measurements of Body Weight (BW), Organ Index, and Serum Biochemical Indicators

2.3. Measurement of Liver Xanthine Oxidase (XOD) and Kidney Antioxidant Parameters

2.4. Renal Histological analysis

2.5. Total RNA Extraction and Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

2.6. Fecal SCFA measurement

2.7. Gut Microbiota Analysis

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

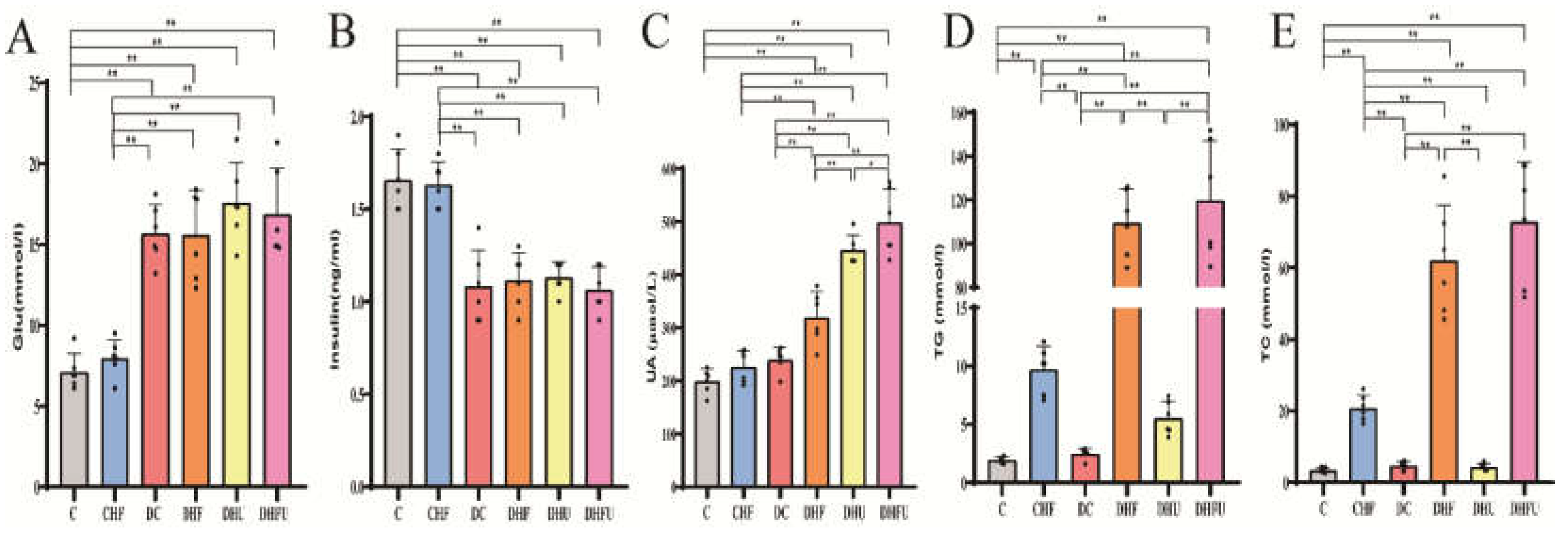

3.1. Induction of diabetes, hyperuricemia and dyslipidemia in hamsters

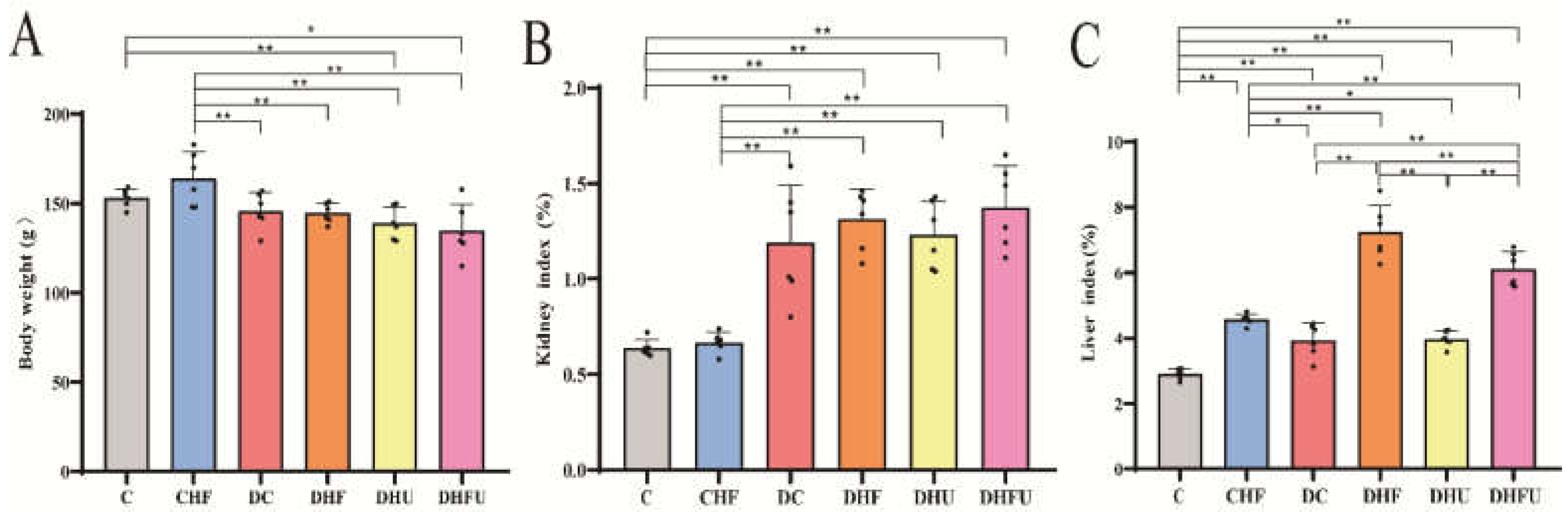

3.2. Effects of high UA on BW and Organ Index in diabetic hamsters

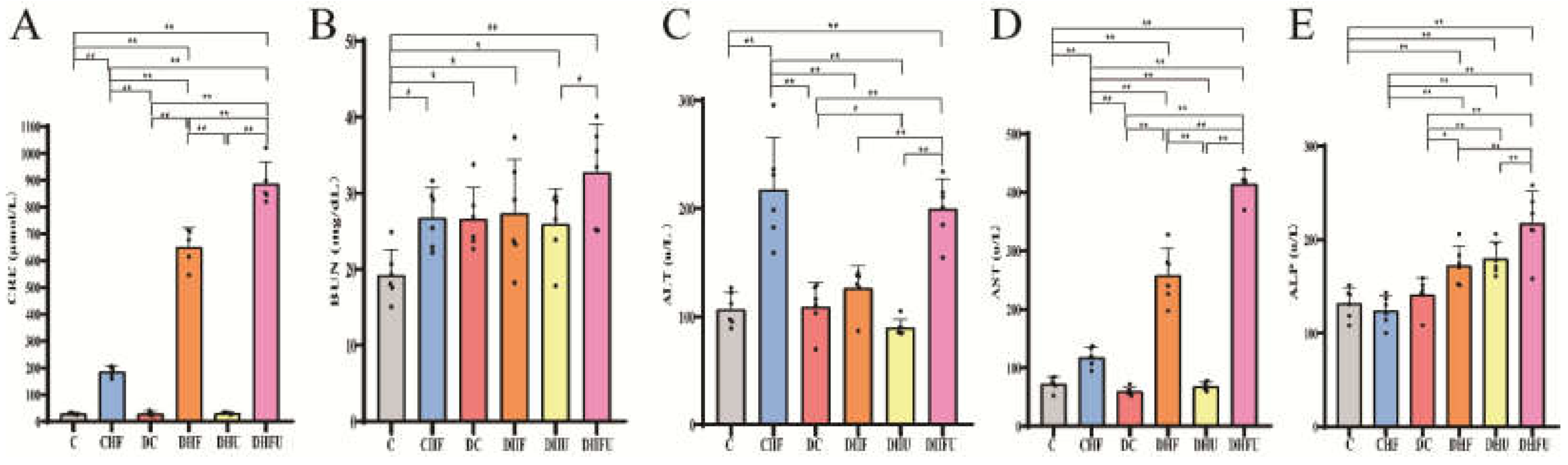

3.3. Effects of high UA on CRE, BUN, ALT, AST and ALP in diabetic hamsters

3.4. Effects of high UA on Liver and Kidney Enzyme Levels to Analyze Oxidative Stress in diabetic hamsters

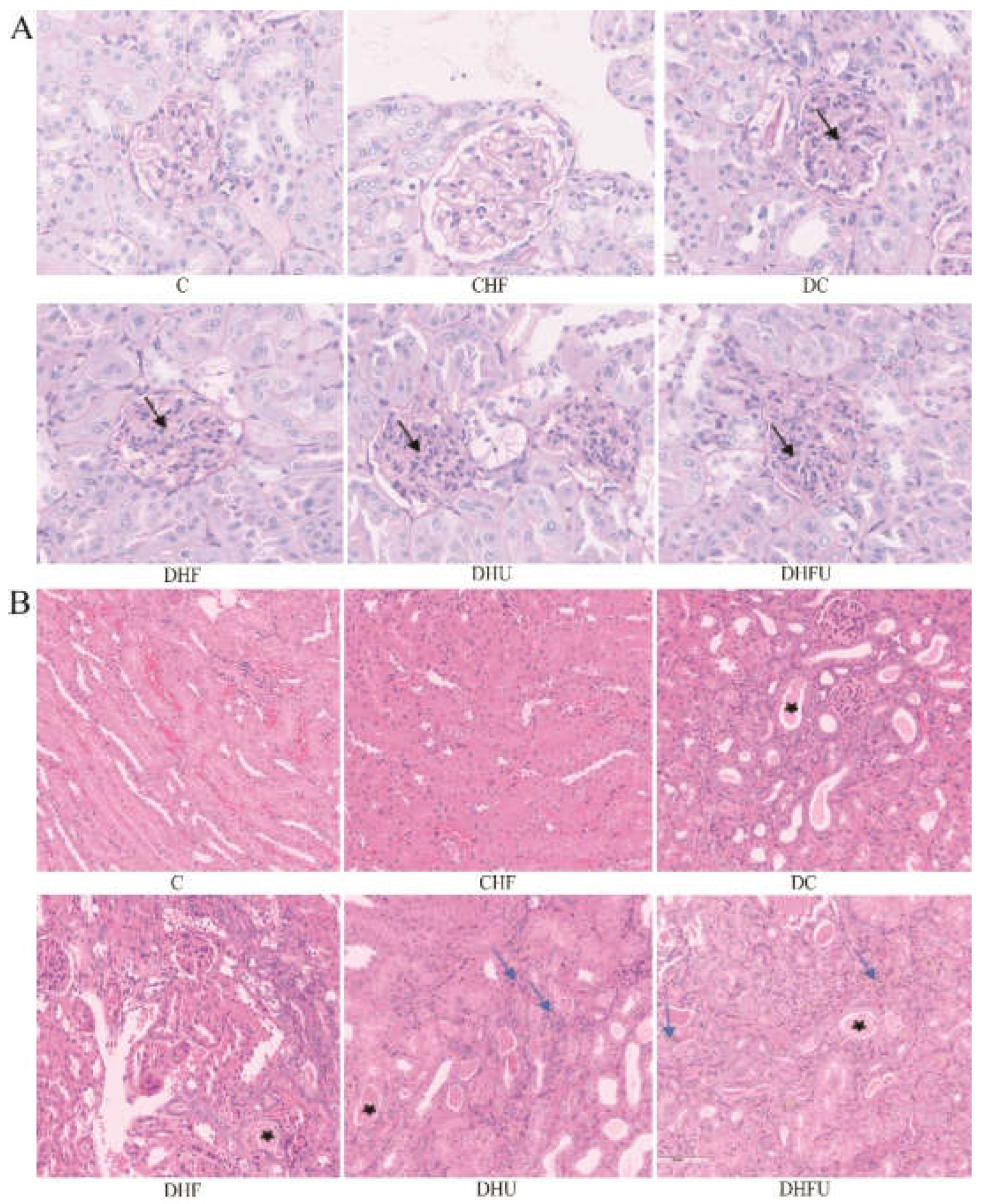

3.5. Effects of high UA on renal histology in diabetic hamsters

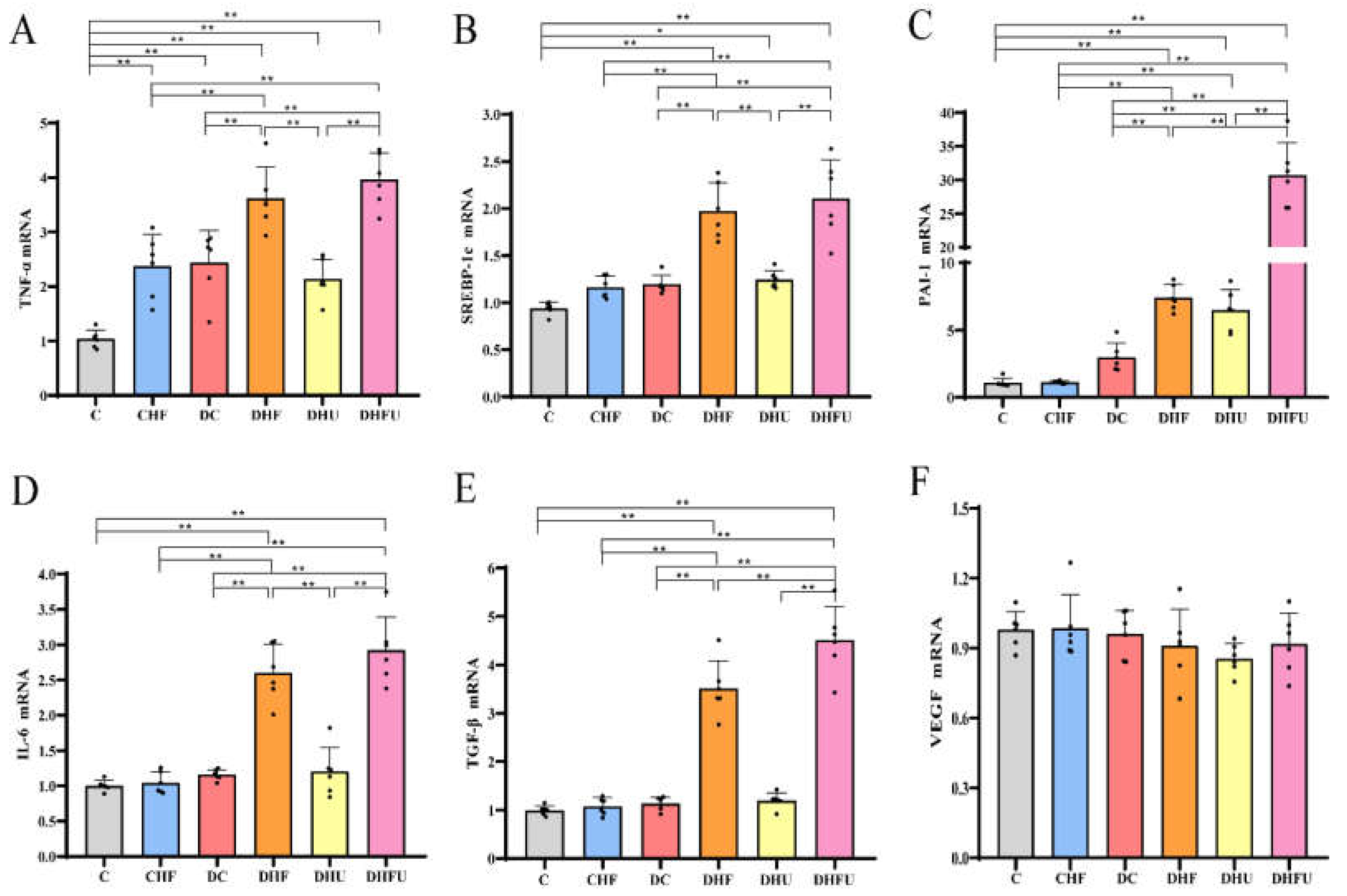

3.6. Effects of high UA on renal gene expression in diabetic hamsters

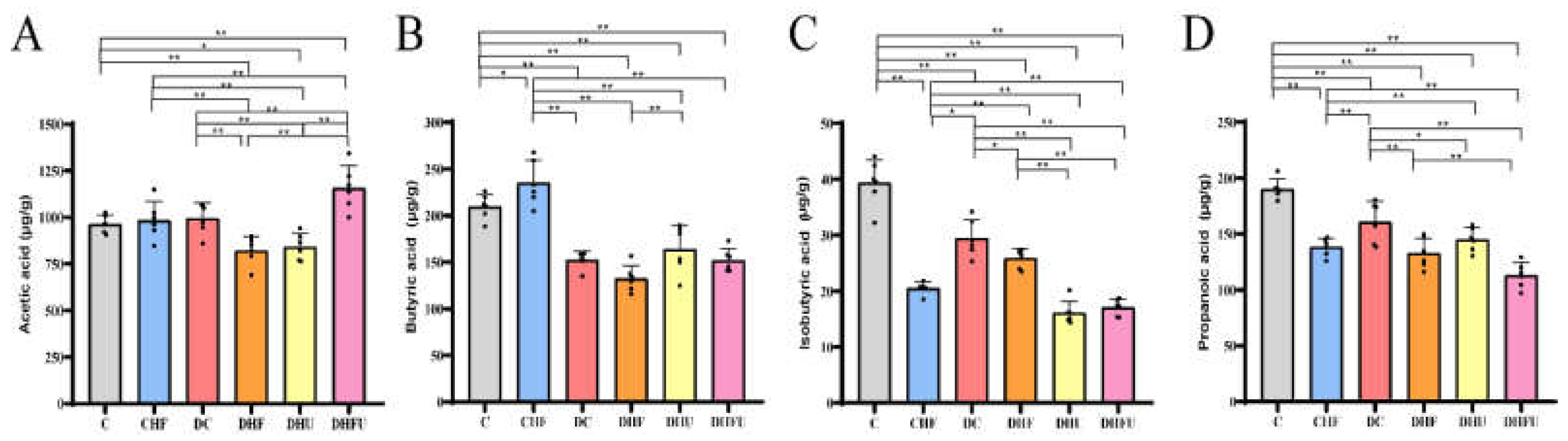

3.7. Evaluation of the high UA effects on fecal SCFAs in diabetic hamsters

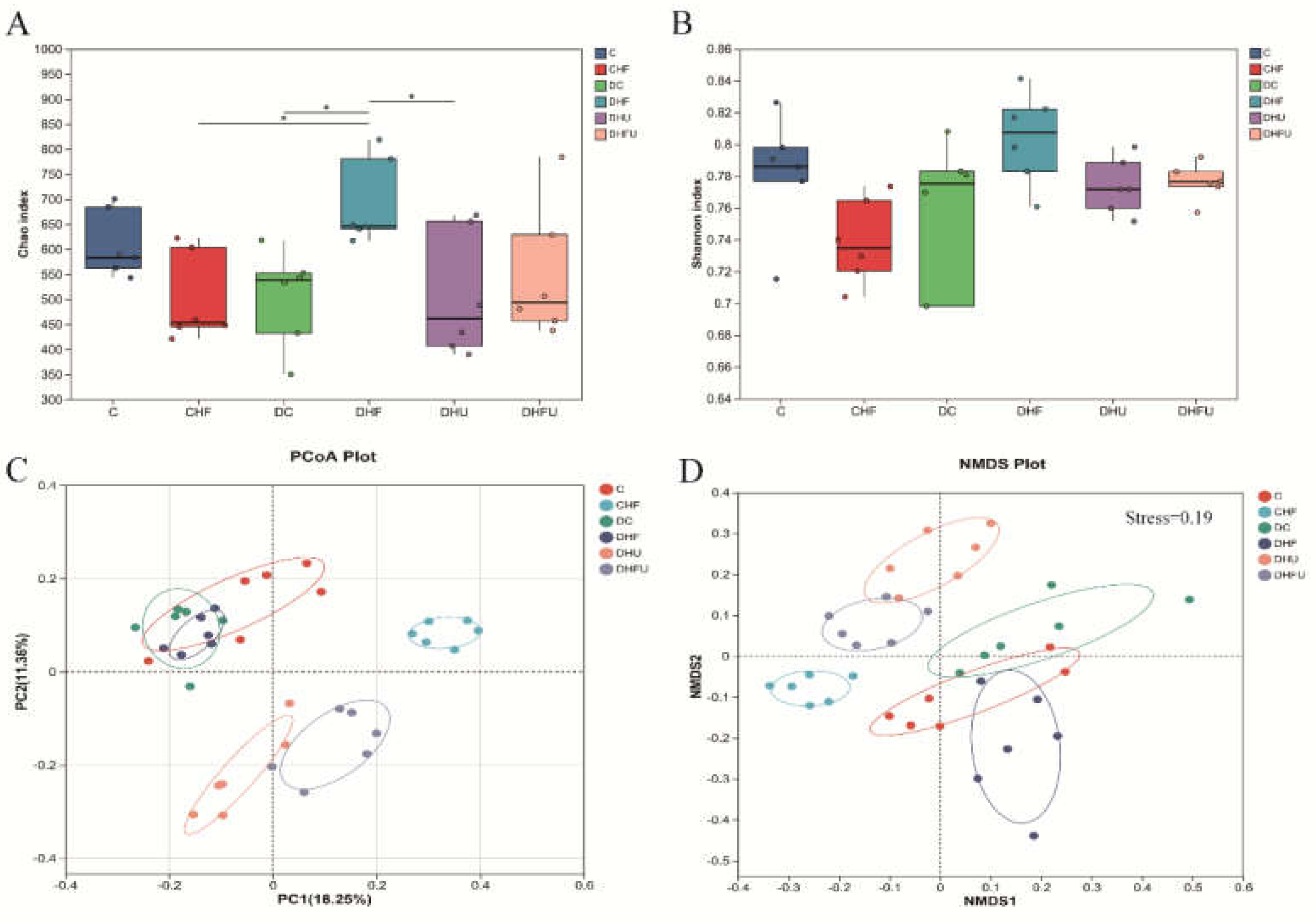

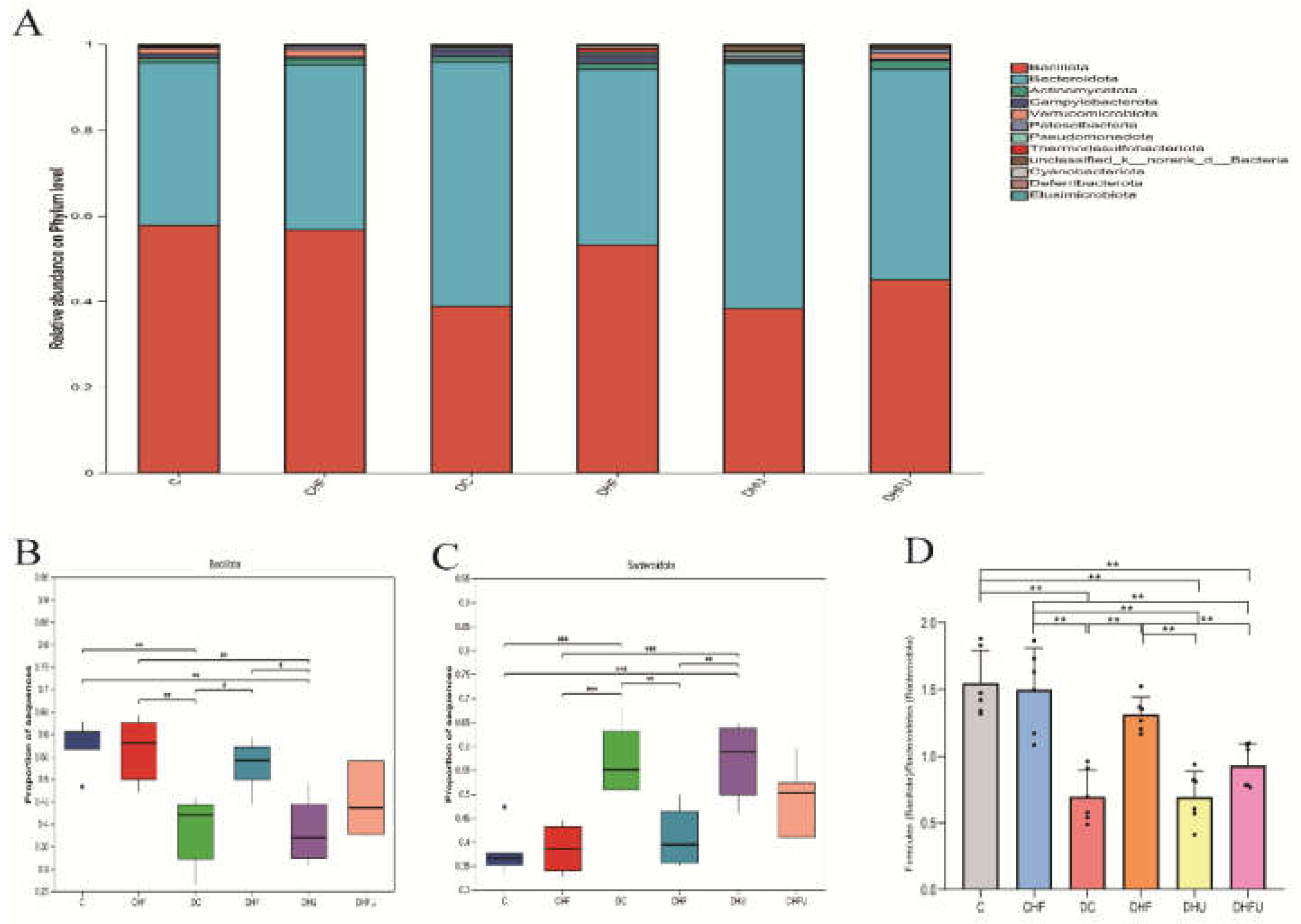

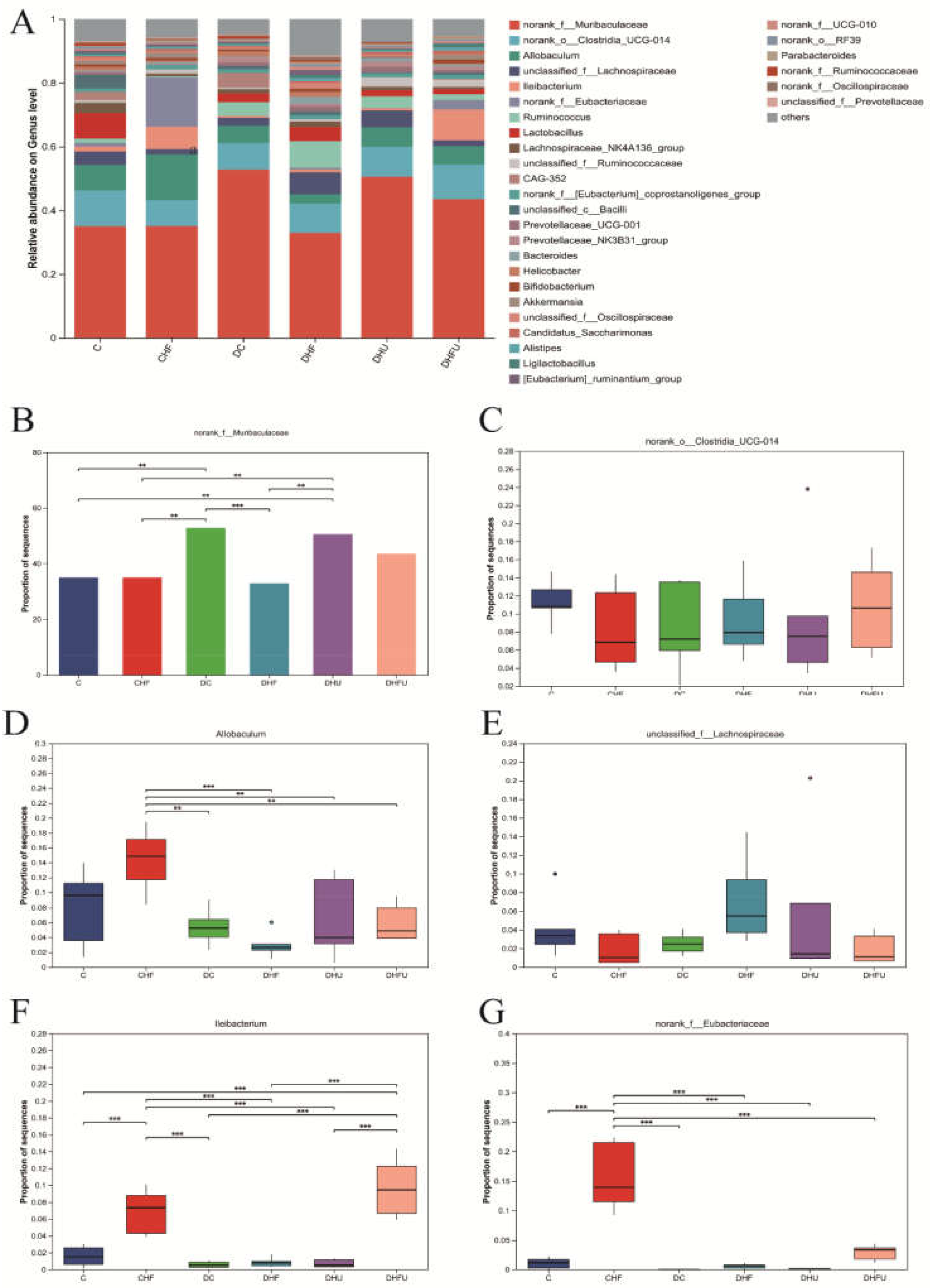

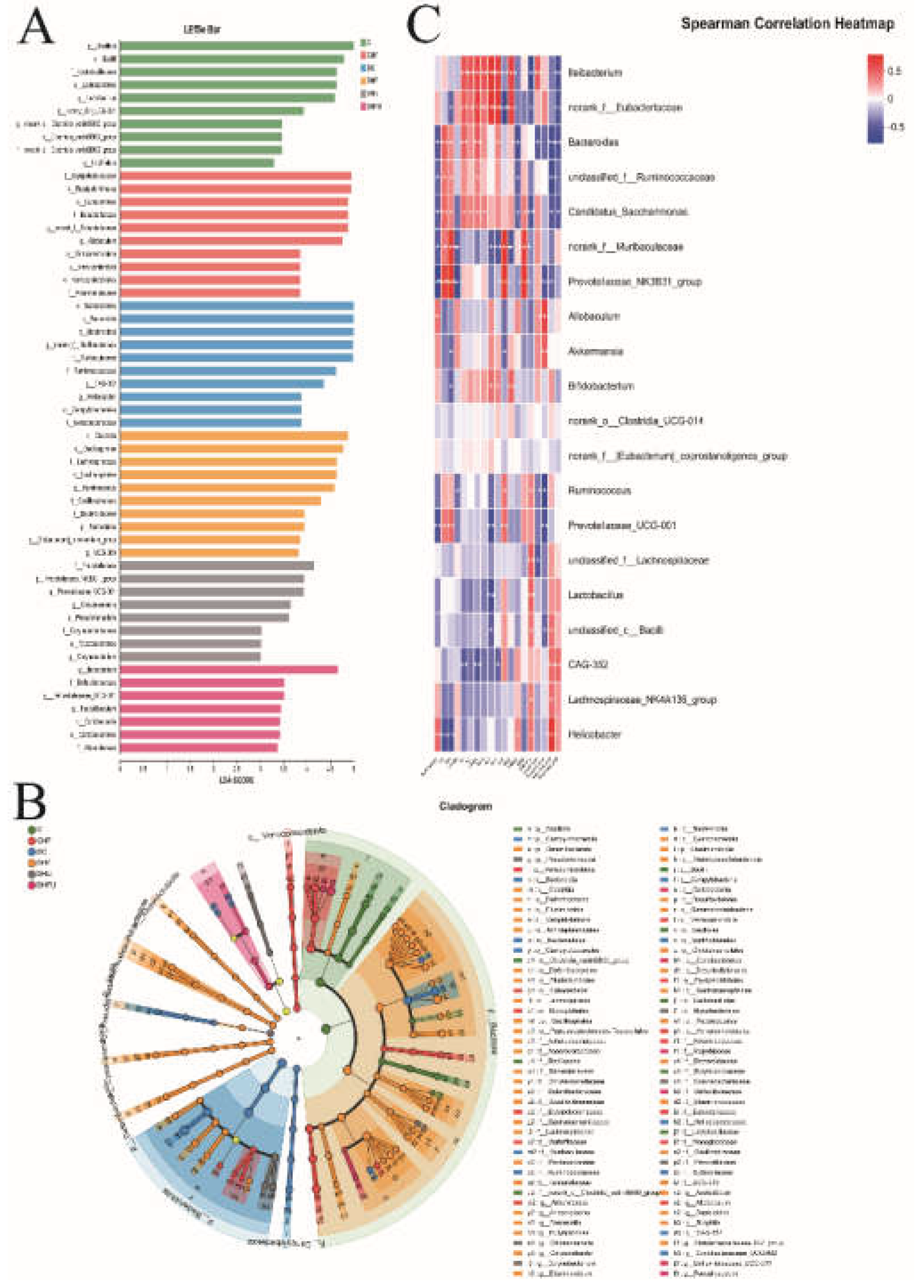

3.8. Evaluation of the high UA effects on the gut microbiota in diabetic hamsters

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schlesinger, N. Dietary factors and hyperuricaemia. Curr Pharm Des 2005, 11, 4133–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Burdett, T.C.; Desjardins, C.A.; Logan, R.; Cipriani, S.; Xu, Y.; Schwarzschild, M.A. Disrupted and transgenic urate oxidase alter urate and dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013, 110, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Xu, M.; Yokose, C.; Rai, S.K.; Pillinger, M.H.; Choi, H.K. Contemporary Prevalence of Gout and Hyperuricemia in the United States and Decadal Trends: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2007-2016. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019, 71, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Jin, C.; Shan, Z.; Teng, W.; Li, J. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Hyperuricemia and Gout: A Cross-sectional Survey from 31 Provinces in Mainland China. J Transl Int Med 2022, 10, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Q.; Lu, X.; Chen, C.; Du, H.; Zhang, R. Risk factors for the development of hyperuricemia: A STROBE-compliant cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019, 98, e17597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zeng, X.; Liu, F.; Fu, P. Is hyperuricemia an independent risk factor for new-onset chronic kidney disease?: A systematic review and meta-analysis based on observational cohort studies. BMC Nephrol 2014, 15, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, S.; Zhang, S.; Qiu, M. Hyperuricemia as a possible risk factor for abnormal lipid metabolism in the Chinese population: a cross-sectional study. Ann Palliat Med 2021, 10, 11454–11463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, S.; Xing, Y.; Fang, Y.; Xing, H.; Pei, M.; Li, J.; Qiao, Y.; Tian, Y.; et al. Gut microbiota and hyperuricemia: From mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. EJMO 2025, 9(2), 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samsu, N. Diabetic Nephropathy: Challenges in Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Biomed Res Int 2021, 2021, 1497449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhole, V.; Choi, J.W.J.; Kim, S.W.; de Vera, M.; Choi, H. Serum uric acid levels and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study. Am J Med 2010, 123, 957–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cosmo, S.; Viazzi, F.; Pacilli, A.; Giorda, C.; Ceriello, A.; Gentile, S.; Russo, G.; Rossi, M.C.; Nicolucci, A.; Guida, P.; et al. Serum Uric Acid and Risk of CKD in Type 2 Diabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015, 10, 1921–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tao, L.; Zhao, Z.; Mu, Y.; Zou, D.; Zhang, J.; Guo, X. Two-Year Changes in Hyperuricemia and Risk of Diabetes: A Five-Year Prospective Cohort Study. J Diabetes Res 2018, 2018, 6905720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; He, Y.; Cui, L.; Xing, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Sun, W.; Ji, A.; et al. Hyperuricemia Predisposes to the Onset of Diabetes via Promoting Pancreatic beta-Cell Death in Uricase-Deficient Male Mice. Diabetes 2020, 69, 1149–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.; Rahman, S.; Islam, S.; Haque, T.; Molla, N.H.; Sumon, A.H.; Kathak, R.R.; Asaduzzaman, M.; Islam, F.; Mohanto, N.C.; et al. The relationship between serum uric acid and lipid profile in Bangladeshi adults. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2019, 19, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, T.-C.; Wang, C.-C.; Kao, T.-W.; Chan, J.Y.-H.; Yang, Y.-H.; Chang, Y.-W.; Chen, W.-L. Relationship between hyperuricemia and lipid profiles in US adults. Biomed Res Int 2015, 2015, 127596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasalic, D.; Marinkovic, N.; Feher-Turkovic, L. Uric acid as one of the important factors in multifactorial disorders--facts and controversies. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2012, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susic, D.; Frohlich, E.D. Hyperuricemia: A Biomarker of Renal Hemodynamic Impairment. Cardiorenal Med 2015, 5, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, X.Z.; Varghese, Z.; Moorhead, J.F. An update on the lipid nephrotoxicity hypothesis. Nat Rev Nephrol 2009, 5, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Sharma, G.S.; Kumbala, D.R. Acute kidney injury in diabetic patients: A narrative review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023, 102, e33888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnenburg, J.L.; Backhed, F. Diet-microbiota interactions as moderators of human metabolism. Nature 2016, 535, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Jarman, J.B.; Low, Y.S.; Augustijn, H.E.; Huang, S.; Chen, H.; DeFeo, M.E.; Sekiba, K.; Hou, B.-H.; Meng, X.; et al. A widely distributed gene cluster compensates for uricase loss in hominids. Cell 2023, 186, 4472–4473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basnet, T.B.; Gc, S.; Basnet, R.; Fatima, S.; Safdar, M.; Sehar, B.; Alsubaie, A.S.R.; Zeb, F. Interaction between gut microbiota metabolites and dietary components in lipid metabolism and metabolic diseases. Access Microbiol 2023, 5, acmi000403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.-F.; Li, Y.-M. Role of gut microbiota in the development of insulin resistance and the mechanism underlying polycystic ovary syndrome: a review. J Ovarian Res 2020, 13, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.X.L.; Yang, L.; Cheng, L.; Chi, F.S.; Tang, L.; Tan, J. Experimental Study on Preparation of Hyperuricemia Rat Model by Five Methods. Journal of Guangzhou University of Traditional Chinese Medicine 2021, 38, 2456–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhouibi, R.; Affes, H.; Salem, M.B.; Moalla, D.; Marekchi, R.; Charfi, S.; Hammami, S.; Sahnoun, Z.; Jamoussi, K.; Zeghal, K.M.; et al. Creation of an adequate animal model of hyperuricemia (acute and chronic hyperuricemia); study of its reversibility and its maintenance. Life Sci 2021, 268, 118998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, K.; Forte, T.M.; Taniguchi, S.; Ishida, B.Y.; Oka, K.; Chan, L. The db/db mouse, a model for diabetic dyslipidemia: molecular characterization and effects of Western diet feeding. Metabolism 2000, 49, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, B.L. Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Models in Mice and Rats. Curr Protoc 2021, 1, e78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.R.; Guo, Q.; Ippolito, M.; Wu, M.; Milot, D.; Ventre, J.; Doebber, T.; Wright, S.D.; Chao, Y.S. High fat fed hamster, a unique animal model for treatment of diabetic dyslipidemia with peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha selective agonists. Eur J Pharmacol 2001, 427, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Evivie, S.E.; Lu, J.; Jiao, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Liu, F.; Huo, G. Lactobacillus helveticus KLDS1.8701 alleviates d-galactose-induced aging by regulating Nrf-2 and gut microbiota in mice. Food Funct 2018, 9, 6586–6598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimoto, T.; Ito, C.; Kato, M.; Ogura, M.; Muto, S.; Kusano, E. Reduced hydration status characterized by disproportionate elevation of blood urea nitrogen to serum creatinine among the patients with cerebral infarction. Med Hypotheses 2011, 77, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Giavarotti, K.A.; Giavarotti, L.; Gomes, L.F.; Lima, A.F.; Veridiano, A.M.; Garcia, E.A.; Mora, O.A.; Fernandez, V.; Videla, L.A.; Junqueira, V.B.C. Enhancement of lindane-induced liver oxidative stress and hepatotoxicity by thyroid hormone is reduced by gadolinium chloride. Free Radic Res 2002, 36, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ussar, S.; Fujisaka, S.; Kahn, C.R. Interactions between host genetics and gut microbiome in diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Mol Metab 2016, 5, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Li, J.; Wang, B.; Yin, X.; Wei, J.; Qiu, H. Progress in modeling avian hyperuricemia and gout (Review). Biomed Rep 2025, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, D.L.; Liu, S.Y.; Tang, M.H.; Lu, Y.Z.; Zhao, M.; Mao, R.W.; Wang, C.S.; Yuan, Y.J.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.N.; et al. Phloretin ameliorates hyperuricemia-induced chronic renal dysfunction through inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome and uric acid reabsorption. Phytomedicine 2020, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, B.X.; Ma, W.J.; Zheng, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, D.; Zhang, Y.J.; Li, Y.H.; Wang, D. Effects of resveratrol on the inflammatory response and renal injury in hyperuricemic rats. Nutr Res Pract 2021, 15, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.W.; Li, L.J.; Zhang, Y.P.; Zeng, C.C. Recent advances in fructose intake and risk of hyperuricemia. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2020, 131, 11079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.N.; Mei, L.; Deng, Y.; Liu, Y.H.; Wei, X.Q.; Liu, M.; Zhou, J.R.; Ma, H.; Zheng, P.Y.; Yuan, J.L.; et al. DM9218 ameliorates fructose-induced hyperuricemia through inosine degradation and manipulation of intestinal dysbiosis. Nutrition 2019, 62, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.C.; Mei, W.D.; Wang, C.X.; Ren, X.; Hu, J.; Su, F.; Cao, L.; Tavengana, G.; Jiang, M.F.; Wu, H.; et al. Dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia: a cross-sectional study of residents in Wuhu, China. Bmc Endocr Disord 2024, 24, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Hao, L.; Fu, X.; Huang, M.; Li, R. Severe hypertriglyceridemia and hypercholesterolemia accelerating renal injury: a novel model of type 1 diabetic hamsters induced by short-term high-fat / high-cholesterol diet and low-dose streptozotocin. BMC Nephrol 2015, 16, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardhana, W.; Rudijanto, A. Effect of Uric Acid on Blood Glucose Levels. Acta Med Indones 2018, 50, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.Y.Z., H. Y.;Wu, L.Y.; Mo, X.W.; Li,J. Establishment and study of a hyperuricemia rat model. Acta Lab Anim Sci Sin 2019, 27, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esen, A.M.; Akcakoyun, M.; Esen, O.; Acar, G.; Emiroglu, Y.; Pala, S.; Kargin, R.; Karapinar, H.; Ozcan, O.; Barutcu, I. Uric acid as a marker of oxidative stress in dilatation of the ascending aorta. Am J Hypertens 2011, 24, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sha, J.; Sui, B.; Su, X.; Meng, Q.; Zhang, C. Alteration of oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines induces apoptosis in diabetic nephropathy. Mol Med Rep 2017, 16, 7715–7723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Zhang, P.; Wang, A.Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Li, G.; Hong, D. Hyperuricemia and its related histopathological features on renal biopsy. BMC Nephrol 2019, 20, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Ma, Y.; Chen, X.; Liang, N.; Qu, S.; Chen, H. Hyperuricemia causes kidney damage by promoting autophagy and NLRP3-mediated inflammation in rats with urate oxidase deficiency. Dis Model Mech 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrass, C.K. Cellular lipid metabolism and the role of lipids in progressive renal disease. Am J Nephrol 2004, 24, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziyadeh, F.N.; Hoffman, B.B.; Han, D.C.; Iglesias-De La Cruz, M.C.; Hong, S.W.; Isono, M.; Chen, S.; McGowan, T.A.; Sharma, K. Long-term prevention of renal insufficiency, excess matrix gene expression, and glomerular mesangial matrix expansion by treatment with monoclonal antitransforming growth factor-beta antibody in db/db diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2000, 97, 8015–8020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmeyer, M.T.; Kretzler, M.; Boucherot, A.; Berra, S.; Yasuda, Y.; Henger, A.; Eichinger, F.; Gaiser, S.; Schmid, H.; Rastaldi, M.P.; et al. Interstitial vascular rarefaction and reduced VEGF-A expression in human diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 2007, 18, 1765–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Gallausiaux, C.; Marinelli, L.; Blottiere, H.M.; Larraufie, P.; Lapaque, N. SCFA: mechanisms and functional importance in the gut. Proc Nutr Soc 2021, 80, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindt, A.; Liebisch, G.; Clavel, T.; Haller, D.; Hormannsperger, G.; Yoon, H.; Kolmeder, D.; Sigruener, A.; Krautbauer, S.; Seeliger, C.; et al. The gut microbiota promotes hepatic fatty acid desaturation and elongation in mice. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.-H.; Alexander, L.M.; Pan, M.; Schueler, K.L.; Keller, M.P.; Attie, A.D.; Walter, J.; van Pijkeren, J.-P. Dietary Fructose and Microbiota-Derived Short-Chain Fatty Acids Promote Bacteriophage Production in the Gut Symbiont Lactobacillus reuteri. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 273–284.e276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, R.; Yu, Y.; Liu, X.; Tian, Z. Protective effect of sodium butyrate on intestinal barrier damage and uric acid reduction in hyperuricemia mice. Biomed Pharmacother 2023, 161, 11456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.V.; Frassetto, A.; Kowalik, E.J., Jr.; Nawrocki, A.R.; Lu, M.M.; Kosinski, J.R.; Hubert, J.A.; Szeto, D.; Yao, X.; Forrest, G.; et al. Butyrate and propionate protect against diet-induced obesity and regulate gut hormones via free fatty acid receptor 3-independent mechanisms. PLoS One 2012, 7, e35240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Liu, Y.L.; Guo, R.; Wang, H.N.; Zhang, W.J.; Wang, Y.Y. Molecular mechanisms of gut microbiota in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Res Clin Pr 2024, 213, 111726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.J.; Jiang, F.L.; Cheng, R.Y.; Luo, Y.T.; Wang, J.N.; Luo, Z.H.; Li, M.; Shen, X.; He, F. A high-fat diet and high-fat and high-cholesterol diet may affect glucose and lipid metabolism differentially through gut microbiota in mice. Exp Anim Tokyo 2021, 70, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ness, C.; Svistounov, D.; Solbu, M.D.; Petrenya, N.; Boardman, N.; Ytrehus, K.; Jenssen, T.G.; Holmes, A.; Simpson, S.J.; Zykova, S.N. Gut Microbiome Diversity and Uric Acid in Serum and Urine. Kidney International Reports 2025, 10, 1683–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Rawat, A.; Alwakeel, M.; Sharif, E.; Al Khodor, S. The potential role of vitamin D supplementation as a gut microbiota modifier in healthy individuals. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 21641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, L.M.; Schafer, M.J.; Sohn, J.; Vincentini, J.; Weiner, H.L.; Ginsberg, S.D.; Blaser, M.J. Calorie restriction slows age-related microbiota changes in an Alzheimer's disease model in female mice. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 17904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, H.C.; Ren, Y.C.; Wang, Y.Q.; Ren, Y.P.; Wang, X.W.; Yue, T.L.; Wang, Z.L.; Gao, Z.P. Preparation, model construction and efficacy lipid-lowering evaluation of kiwifruit juice fermented by probiotics. Food Biosci 2022, 47, 101710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Guo, M.; Yuan, X.; Fan, X.; Wang, J.; Jiao, X. Gut Microbiota and Their Metabolites: The Hidden Driver of Diabetic Nephropathy? Unveiling Gut Microbe's Role in DN. J Diabetes 2025, 17, e70068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, X.; Yang, X. Altered Gut Microbiota in Children With Hyperuricemia. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 848715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Li, W.; Chen, Y.; Lei, L.; Li, F.; Zhao, J.; Zeng, K.; Ming, J. Dietary fiber of Tartary buckwheat bran modified by steam explosion alleviates hyperglycemia and modulates gut microbiota in db/db mice. Food Res Int 2022, 157, 111386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, Y.; Guo, Y.; Chen, M.; Lu, X.; Guo, Z.; Zheng, B. Gut microbiome-serum metabolic profiles: insight into the hypoglycemic effect of Porphyra haitanensis glycoprotein on hyperglycemic mice. Food & function 2023, 14, 7977–7991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Genes | Forward | Reverse |

| TNF-α | AACCTCCTGTCCGCCATCAA | GCACTGAGTCGGTCACCTTTC |

| SREBP-1c | GCTGCTGACAACGGTAAAAACA | CCAGTCTATGGATGGGCAGTTT |

| PAI-1 | CCGTGGAACCAGAACGAGATT | TGATCATACCTCTGGTGTGCCTC |

| IL-6 | CAAGTCGGAGGTTTGGTTACATATG | CATTGTCCATACAGCCAGGGTT |

| TGF-β | TGACAGCAAAGACAACGCACTC | TGGAGCTGAAGCAGTAGTTGGTG |

| VEGF | CCTGGCTTTACTGCTGTACCTCC | CAATAGCTGCGCCGGTAGAC |

| β-actin | CTTTCTTCGCCGCTCCACA | TGACAATGCCGTGTTCAATGG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).