Submitted:

09 July 2025

Posted:

10 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

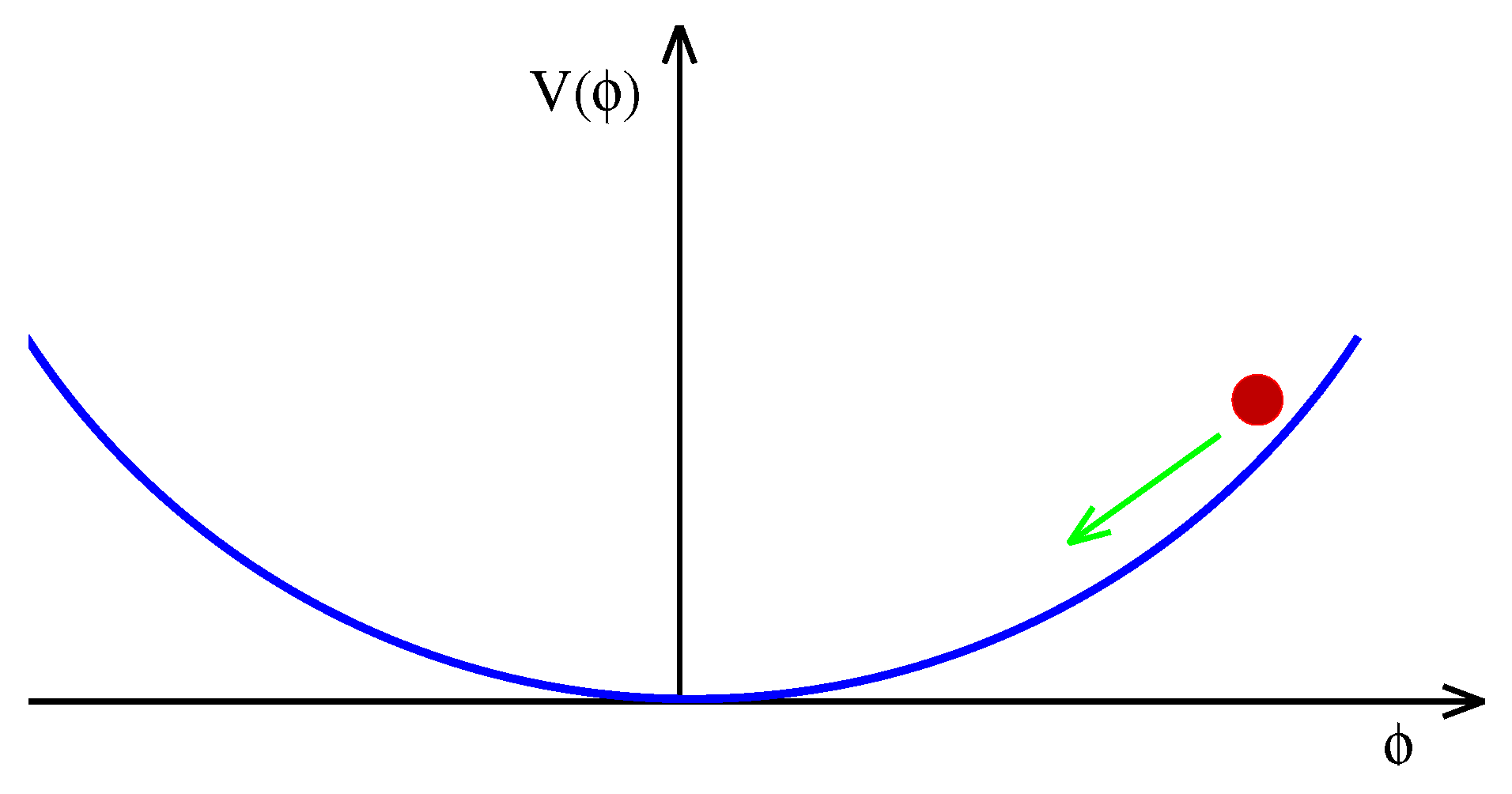

2. Single-Field Inflation: Successes and Concealed Assumptions

2.1. Implicit Assumptions

2.2. Emerging Tensions

Lyth Bound and Tensor Amplitudes

Fine-Tuning of Potential and Initial Conditions

3. Drivers of the Multifield Turn

3.1. Observational Provocations

3.2. Philosophical Shifts

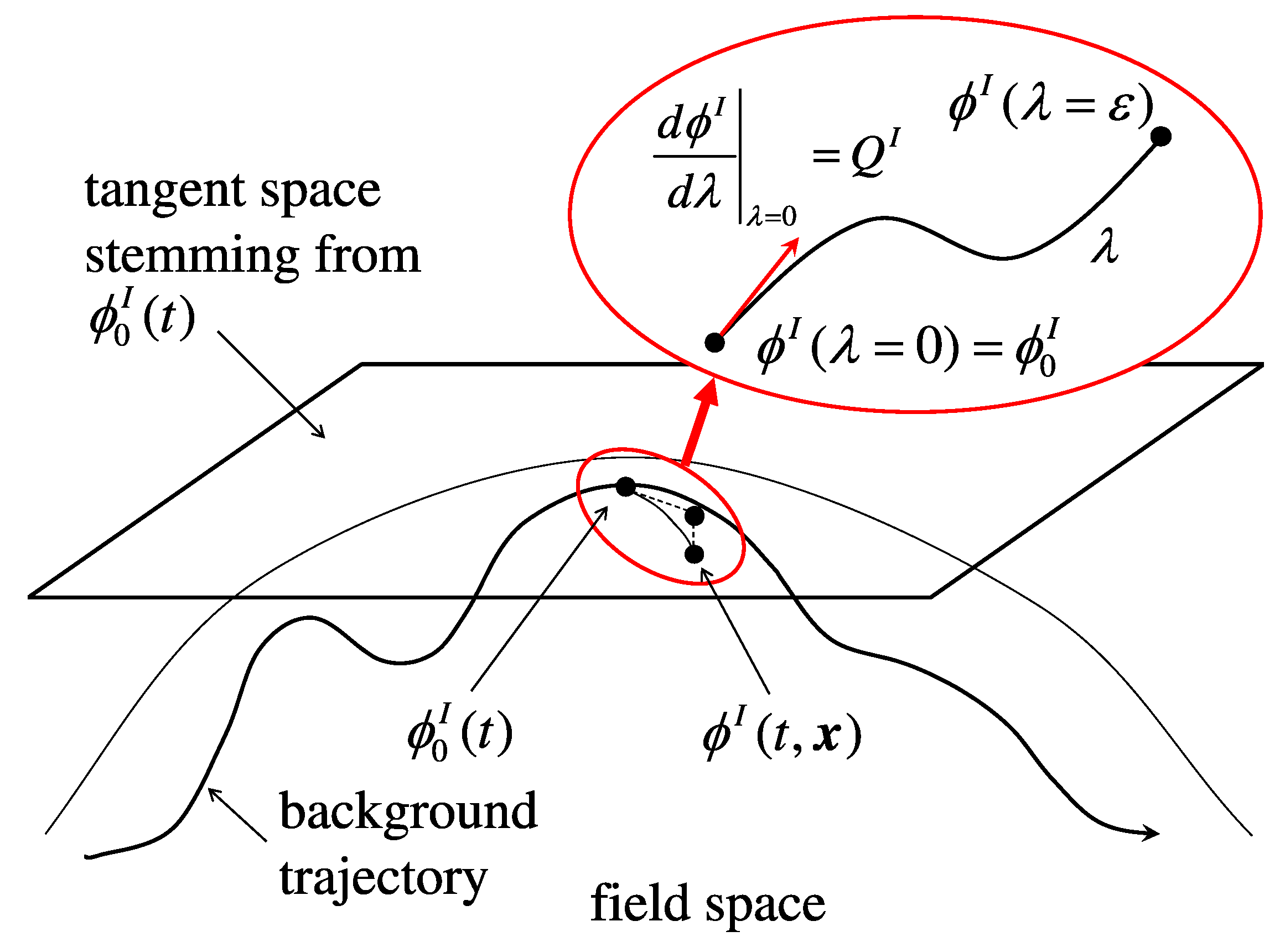

4. Conceptual Framework of Multifield Inflation

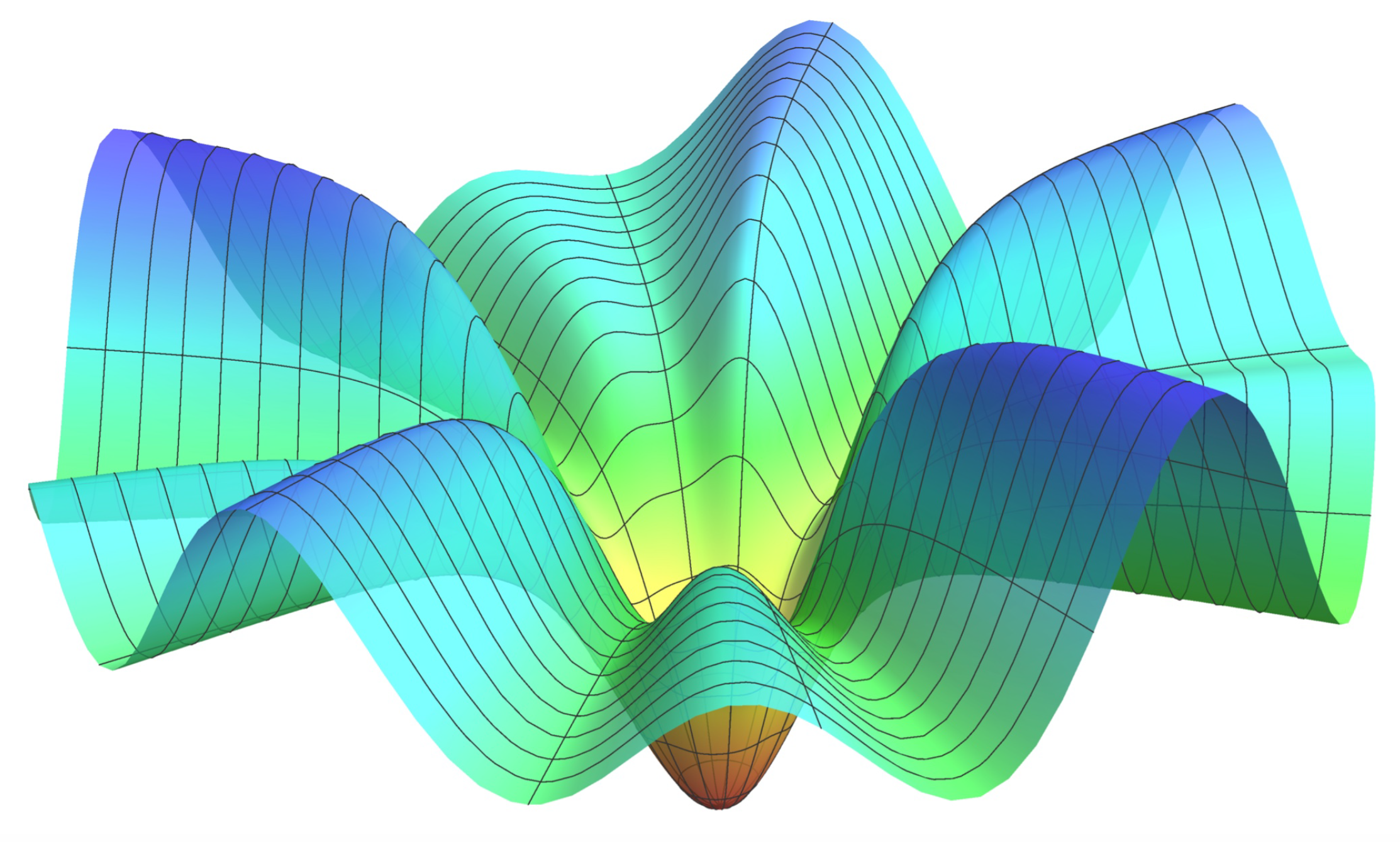

4.1. Field-Space Geometry

4.2. Mode Decomposition

- is the adiabatic unit vector, defined as the tangent to the trajectory

- with span the entropy subspace orthogonal to .

- , the second derivative of the potential along the trajectory,

- , the entropy mass term,

- , the turn-rate.

- If is transiently large, sharp features or oscillations can arise in or .

- If is sustained, the model can mimic a single-field scenario but with modified consistency relations.

4.3. Dynamics and Attractors

Multifield Attractor Solutions

Waterfall and Hybrid Transitions

- Tachyonic preheating: The exponential growth of -modes leads to efficient particle production.

- Entropy transfer: Rapid evolution in generates isocurvature perturbations that feed into .

- Topological defects: If has a nontrivial vacuum manifold, cosmic strings or domain walls can form.

5. Comparing Paradigms: Single- vs. Multifield Inflation

5.1. Predictivity and the Measure Problem

Volume Weighting in Eternal Inflation

5.1.0.1. Langevin and Fokker-Planck Treatments

5.1.0.2. Toward a Predictive Framework

- Conditional Probabilities: Weighting predictions by likelihood of ending up in an attractor basin compatible with observed parameters.

- Holographic Cutoffs: Defining measures on the boundary of field space using covariant entropy bounds [43].

- Anthropic Conditioning: Restricting to regions where complex structure or life-supporting conditions are met.

5.2. Initial-Condition Naturalness

5.3. Quantum-to-Classical Transition

- Wigner function positivity: The Wigner quasi-probability distribution should become positive-definite and sharply peaked [172].

- Squeezing of modes: The field modes become highly squeezed on super-Hubble scales, implying classical stochastic behavior [173].

- Suppression of off-diagonal density matrix elements: Decoherence functionals suppress quantum interference terms [167].

6. Primordial Relics in Multifield Scenarios

6.1. Transient Turns and Spectator-Field Spikes

(a) Transient Turns in Field Space.

(b) Excited Spectator Fields.

(c) Coupled Field Oscillations.

Threshold and Abundance

- Field-Space Geometry: Nontrivial curvature can induce dynamical focusing, attractor behavior, or instabilities that localize power spectrum enhancement [103].

- Potential Structure: Small localized features in that are irrelevant for CMB-scale modes can dominate on smaller scales [185].

- Isocurvature Conversion: The efficiency and scale-dependence of isocurvature sourcing of is sensitive to turning trajectories, mass hierarchies, and kinetic couplings [19].

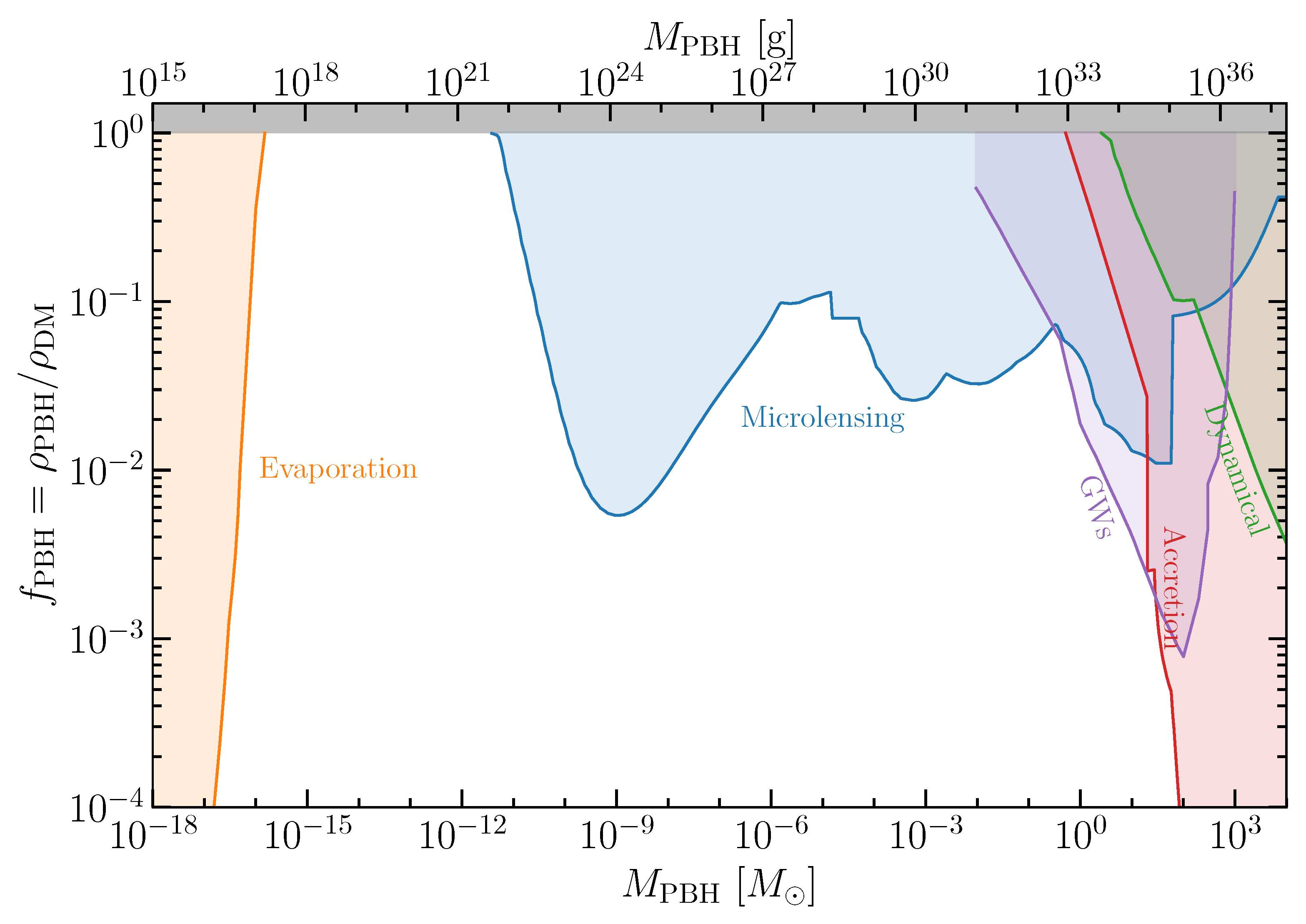

PBHs as a “microscope”

| Feature | Single-field | Multifield |

|---|---|---|

| Amplitude source | USR / inflection point | Turn-induced sourcing, entropy modes |

| Field-space geometry | Flat (usually) | Curved |

| Multiple spikes | Fine-tuned | Natural (multiple turns / fields) |

| Predictivity | Higher | Requires trajectory classification |

| Observational signatures | Single peak | Broadened / multimodal mass spectrum |

6.2. Multifield DM production

Curvaton mechanism.

| Thermal freeze-out | Non-thermal (curvaton/spectator) | |

|---|---|---|

| Production | Boltzmann suppression | Decay of heavy field |

| Velocity dispersion | Warm/cold depending on mass | Typically cold |

| Isocurvature | Negligible | Potentially significant |

| Predictivity | Relic density fixed by cross-section | Sensitive to decay rates and branching |

6.3. Synergies and Tensions

| Observable | Scale | Key Constraint | Multifield Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMB | Mpc−1 | , r, , | Entropy-curvature transfer |

| LSS | Mpc−1 | Halo bias, shape | Non-Gaussianity bias |

| Microlensing | PBH masses | Small-scale power spikes | |

| GW | Hz | spectrum | Second-order scalar sourcing |

7. Observational Implications as Conceptual Tests

- Entropy sourcing: Part of comes from isocurvature modes ⇒ enhanced scalar spectrum ⇒ reduced r.

- Heavy field production: Tensor spectrum sourced nontrivially.

- Non-standard reheating: Affects post-inflation evolution of modes.

8. Synthesis

8.1. Toward an Effective Single-Field Emergent Description

8.2. Role of Reheating Entropy

9. Conclusions

Refining theoretical frameworks.

Observational frontiers.

Acknowledgments

Appendix A. Foundational Reflections: What Counts as a “Field”?

- Field redefinitions: Scalar fields related by nonlinear transformations may describe the same physical system. The physical observables depend on invariant geometric quantities, suggesting fields are coordinate-dependent labels on a manifold rather than absolute entities.

- Non-geodesic motion: Multifield inflation often involves turning trajectories in field space, generating entropy perturbations. This challenges the notion of fields as isolated objects and highlights their relational character.

References

- A.H., Guth. The Inflationary Universe: A Possible Solution to the Horizon and Flatness Problems. Phys. Rev. D 1981, 23, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.D., Linde. A New Inflationary Universe Scenario: A Possible Solution of the Horizon, Flatness, Homogeneity, Isotropy and Primordial Monopole Problems. Phys. Lett. B 1982, 108, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Albrecht and P.J., Steinhardt. Cosmology for Grand Unified Theories with Radiatively Induced Symmetry Breaking. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1982, 48, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A., Starobinsky. A new type of isotropic cosmological models without singularity. Physics Letters B 1980, 91, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V.F. Mukhanov and G.V., Chibisov. Quantum Fluctuations and a Nonsingular Universe. JETP Lett. 1981, 33, 532. [Google Scholar]

- A. Achúcarro et al., Inflation: Theory and Observations, 2203.08128.

- C.L. Bennett; et al. Nine-year wilkinson microwave anisotropy probe ( wmap ) observations: Final maps and results. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2013, 208, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planck collaboration. Planck 2018 results. X. Constraints on inflation. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 641, A10 [1807.06211]. [Google Scholar]

- Simons Observatory collaboration, The Simons Observatory: Science goals and forecasts, JCAP 02 (2019) 056 [1808. 0 7445.

- K. Abazajian et al., CMB-S4 Science Case, Reference Design, and Project Plan, 1907.04473.

- M., Hazumi; et al. LiteBIRD satellite: JAXA’s new strategic L-class mission for all-sky surveys of cosmic microwave background polarization. In Space Telescopes and Instrumentation 2020: Optical, Infrared, and Millimeter; Wave, M. Lystrup, M.D. Perrin, Ed.; International Society for Optics and Photonics, SPIE, 2020; Volume 11443, p. 114432F. [Google Scholar]

- BICEP, Keck collaboration. Improved Constraints on Primordial Gravitational Waves using Planck, WMAP, and BICEP/Keck Observations through the 2018 Observing Season. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 127, 151301 [2110.00483]. [Google Scholar]

- ACT collaboration, The Atacama Cosmology Telescope: DR6 Constraints on Extended Cosmological Models, 2503. 1 4454.

- D.H. Lyth and A. Riotto, Particle physics models of inflation and the cosmological density perturbation, Physics Reports 314 (1999) 1–146.

- D. Baumann, Tasi lectures on inflation, 2012.

- M. Cicoli, J.P. M. Cicoli, J.P. Conlon and F. Quevedo, General analysis of large volume scenarios with string loop moduli stabilisation, Journal of High Energy Physics 2008 (2008) 105–105.

- A. Achucarro, J.-O. Gong, S. Hardeman, G.A. Palma and S.P. Patil, Features of heavy physics in the CMB power spectrum, JCAP 01 (2011) 030 [1010.3693].

- D. Baumann and D. Green, Equilateral non-gaussianity and new physics on the horizon, Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2011 (2011) 014.

- C. Gordon, D. Wands, B.A. Bassett and R. Maartens, Adiabatic and entropy perturbations from inflation, Phys. Rev. D 63 (2000) 023506 [astro-ph/0009131].

- D.H. Lyth and D. Wands, Generating the curvature perturbation without an inflaton, Phys. Lett. B 524 (2002) 5 [hep-ph/0110002].

- D. Wands, N. Bartolo, S. Matarrese and A. Riotto, An Observational test of two-field inflation, Phys. Rev. D 66 (2002) 043520 [astro-ph/0205253].

- Z. Lalak, D. Langlois, S. Pokorski and K. Turzynski, Curvature and isocurvature perturbations in two-field inflation, JCAP 07 (2007) 014 [0704.0212].

- D. Wands, Multiple field inflation, Lect. Notes Phys. 738 (2008) 275 [astro-ph/0702187].

- D. Langlois, Cosmological perturbations from multi-field inflation, J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 140 (2008) 012004 [0809.2540].

- S. Groot Nibbelink and B.J.W. van Tent, Scalar perturbations during multiple field slow-roll inflation, Class. Quant. Grav. 19 (2002) 613 [hep-ph/0107272].

- C.M. Peterson and M. Tegmark, Testing Two-Field Inflation, Phys. Rev. D 83 (2011) 023522 [1005.4056].

- M. Dias, J. Frazer and D. Seery, Computing observables in curved multifield models of inflation—A guide (with code) to the transport method, JCAP 12 (2015) 030 [1502.03125].

- S. Clesse and J. García-Bellido, Massive Primordial Black Holes from Hybrid Inflation as Dark Matter and the seeds of Galaxies, Phys. Rev. D 92 (2015) 023524 [1501.07565].

- O. Özsoy and G. Tasinato, Inflation and Primordial Black Holes, Universe 9 (2023) 203 [2301.03600].

- M. Kawasaki, N. Kitajima and T.T. Yanagida, Primordial black hole formation from an axionlike curvaton model, Phys. Rev. D 87 (2013) 063519 [1207.2550].

- T. Markkanen, A. Rajantie and T. Tenkanen, Spectator Dark Matter, Phys. Rev. D 98 (2018) 123532 [1811.02586].

- T. Tenkanen, Dark matter from scalar field fluctuations, Phys. Rev. Lett. 123 (2019) 061302 [1905.01214].

- T. Tenkanen and L. Visinelli, Axion dark matter from Higgs inflation with an intermediate H*, JCAP 08 (2019) 033 [1906.11837].

- S. Hawking and D.N. Page, How probable is inflation?, Nuclear Physics B 298 (1988) 789.

- G.W. Gibbons and N. Turok, The Measure Problem in Cosmology, Phys. Rev. D 77 (2008) 063516 [hep-th/0609095].

- D.N. Page, Finite Canonical Measure for Nonsingular Cosmologies, JCAP 06 (2011) 038 [1103.3699].

- V. Vanchurin, Dynamical systems of eternal inflation: a possible solution to the problems of entropy, measure, observables and initial conditions, Phys. Rev. D 86 (2012) 043502 [1204.1055].

- J.S. Schiffrin and R.M. Wald, Measure and Probability in Cosmology, Phys. Rev. D 86 (2012) 023521 [1202.1818].

- A. Ashtekar and D. Sloan, Loop quantum cosmology and slow roll inflation, Physics Letters B 694 (2010) 108.

- A.H. Guth, Eternal inflation and its implications, J. Phys. A 40 (2007) 6811 [hep-th/0702178].

- B. Freivogel, Making predictions in the multiverse, Class. Quant. Grav. 28 (2011) 204007 [1105.0244].

- L. Susskind, The Anthropic landscape of string theory, hep-th/0302219.

- R. Bousso, Positive vacuum energy and the N bound, JHEP 11 (2000) 038 [hep-th/0010252].

- D. Wands, K.A. Malik, D.H. Lyth and A.R. Liddle, A New approach to the evolution of cosmological perturbations on large scales, Phys. Rev. D 62 (2000) 043527 [astro-ph/0003278].

- S. Weinberg, Cosmology (2008).

- A.R. Liddle, An Introduction to cosmological inflation, in ICTP Summer School in High-Energy Physics and Cosmology, pp. 260–295, 1, 1999 [astro-ph/9901124].

- M., Sasaki. Large Scale Quantum Fluctuations in the Inflationary Universe. Prog. Theor. Phys. 1986, 76, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V.F. Mukhanov, Gravitational Instability of the Universe Filled with a Scalar Field, JETP Lett. 41 (1985) 493.

- V. Mukhanov, H. Feldman and R. Brandenberger, Theory of cosmological perturbations, Physics Reports 215 (1992) 203.

- D. Baumann and L. McAllister, Inflation and String Theory, Cambridge Monographs on Mathematical Physics, Cambridge University Press (5, 2015), 10.1017/CBO9781316105733, [1404.2601].

- S. Cespedes, V. Atal and G.A. Palma, On the importance of heavy fields during inflation, JCAP 05 (2012) 008 [1201.4848].

- M. Cicoli and A. Mazumdar, Reheating for Closed String Inflation, JCAP 09 (2010) 025 [1005.5076].

- C.P. Burgess, M. Majumdar, D. Nolte, F. Quevedo, G. Rajesh and R.-J. Zhang, The Inflationary brane anti-brane universe, JHEP 07 (2001) 047 [hep-th/0105204].

- F. Quevedo, Lectures on string/brane cosmology, Class. Quant. Grav. 19 (2002) 5721 [hep-th/0210292].

- A.J. Tolley and M. Wyman, The Gelaton Scenario: Equilateral non-Gaussianity from multi-field dynamics, Phys. Rev. D 81 (2010) 043502 [0910.1853].

- A. Ijjas, P.J. Steinhardt and A. Loeb, Inflationary paradigm in trouble after Planck2013, Phys. Lett. B 723 (2013) 261 [1304.2785].

- J. Martin, V. Vennin and P. Peter, Cosmological Inflation and the Quantum Measurement Problem, Phys. Rev. D 86 (2012) 103524 [1207.2086].

- Antoniadis, A. Karam, A. Lykkas and K. Tamvakis. Palatini inflation in models with an R2 term. JCAP 2018, 11, 028 [1810.10418]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Karam, T. Pappas and K. Tamvakis, Nonminimal Coleman–Weinberg Inflation with an R2 term, JCAP 02 (2019) 006 [1810.12884].

- T. Tenkanen, Minimal Higgs inflation with an R2 term in Palatini gravity, Phys. Rev. D 99 (2019) 063528 [1901.01794].

- I. Antoniadis, A. Karam, A. Lykkas, T. Pappas and K. Tamvakis, Single-field inflation in models with an R2 term, PoS CORFU2019 (2020) 073 [1912.12757].

- I.D. Gialamas, A. Karam and A. Racioppi, Dynamically induced Planck scale and inflation in the Palatini formulation, JCAP 11 (2020) 014 [2006.09124].

- A. Karam, E. Tomberg and H. Veermäe, Tachyonic preheating in Palatini R 2 inflation, JCAP 06 (2021) 023 [2102.02712].

- A. Ghoshal, D. Mukherjee and M. Rinaldi, Inflation and primordial gravitational waves in scale-invariant quadratic gravity with Higgs, JHEP 05 (2023) 023 [2205.06475].

- S. Aoki, A. Ghoshal and A. Strumia, Cosmological collider non-Gaussianity from multiple scalars and R2 gravity, JHEP 11 (2024) 009 [2408.07069].

- N. Bostan and R.H. Dejrah, Minimally coupled β-exponential inflation with an R2 term in the Palatini formulation, 2409.10398.

- F.L. Bezrukov and M. Shaposhnikov, The Standard Model Higgs boson as the inflaton, Phys. Lett. B 659 (2008) 703 [0710.3755].

- F.L. Bezrukov, The Standard model Higgs as the inflaton, in 43rd Rencontres de Moriond on Electroweak Interactions and Unified Theories, pp. 53–58, 5, 2008 [0805.2236].

- D. Boyanovsky, H.J. de Vega and N.G. Sanchez, Clarifying slow roll inflation and the quantum corrections to the observable power spectra, in 15th Workshop on General Relativity and Gravitation, 1, 2006 [astro-ph/0601132].

- K.I. Izawa, Fine tunings for inflation with simple potentials, PTEP 2014 (2014) 113B05 [1407.2328].

- S.M. Carroll, In What Sense Is the Early Universe Fine-Tuned?, (2014) [1406.3057].

- R. Kallosh and A. Linde, Universality Class in Conformal Inflation, JCAP 07 (2013) 002 [1306.5220].

- R. Kallosh and A. Linde, Hidden Superconformal Symmetry of the Cosmological Evolution, JCAP 01 (2014) 020 [1311.3326].

- D.H. Lyth, What would we learn by detecting a gravitational wave signal in the cosmic microwave background anisotropy?, Phys. Rev. Lett. 78 (1997) 1861 [hep-ph/9606387].

- G. Efstathiou and K.J. Mack, The Lyth bound revisited, JCAP 05 (2005) 008 [astro-ph/0503360].

- J. Garcia-Bellido, D. Roest, M. Scalisi and I. Zavala, Lyth bound of inflation with a tilt, Phys. Rev. D 90 (2014) 123539 [1408.6839].

- D.S. Goldwirth and T. Piran, Inhomogeneity and the onset of inflation, Phys. Rev. Lett. 64 (1990) 2852.

- W.E. East, M. Kleban, A. Linde and L. Senatore, Beginning inflation in an inhomogeneous universe, JCAP 09 (2016) 010 [1511.05143].

- K. Clough, E.A. Lim, B.S. DiNunno, W. Fischler, R. Flauger and S. Paban, Robustness of Inflation to Inhomogeneous Initial Conditions, JCAP 09 (2017) 025 [1608.04408].

- P. Carrilho, D. Mulryne, J. Ronayne and T. Tenkanen, Attractor Behaviour in Multifield Inflation, JCAP 06 (2018) 032 [1804.10489].

- D.I. Kaiser, Nonminimal Couplings in the Early Universe: Multifield Models of Inflation and the Latest Observations, Fundam. Theor. Phys. 183 (2016) 41 [1511.09148].

- T. Rudelius, Constraints on Axion Inflation from the Weak Gravity Conjecture, JCAP 09 (2015) 020 [1503.00795].

- E. Palti, The Weak Gravity Conjecture and Scalar Fields, JHEP 08 (2017) 034 [1705.04328].

- E. Palti, The Swampland: Introduction and Review, Fortsch. Phys. 67 (2019) 1900037 [1903.06239].

- L. McAllister, E. Silverstein and A. Westphal, Gravity Waves and Linear Inflation from Axion Monodromy, Phys. Rev. D 82 (2010) 046003 [0808.0706].

- M. Grana, Flux compactifications in string theory: A Comprehensive review, Phys. Rept. 423 (2006) 91 [hep-th/0509003].

- M.R. Douglas and S. Kachru, Flux compactification, Rev. Mod. Phys. 79 (2007) 733 [hep-th/0610102].

- F. Denef, Lectures on constructing string vacua, Les Houches 87 (2008) 483 [0803.1194].

- M. Cicoli, C.P. M. Cicoli, C.P. Burgess and F. Quevedo, Fibre Inflation: Observable Gravity Waves from IIB String Compactifications, JCAP 03 (2009) 013 [0808.0691].

- J.J. Blanco-Pillado, C.P. Burgess, J.M. Cline, C. Escoda, M. Gomez-Reino, R. Kallosh et al., Racetrack inflation, JHEP 11 (2004) 063 [hep-th/0406230].

- J. Read and B. Le Bihan, The landscape and the multiverse: What’s the problem?, Synthese 199 (2021) 7749.

- B.A. Bassett, S. Tsujikawa and D. Wands, Inflation dynamics and reheating, Rev. Mod. Phys. 78 (2006) 537 [astro-ph/0507632].

- C.T. Byrnes and K.-Y. Choi, Review of local non-Gaussianity from multi-field inflation, Adv. Astron. 2010 (2010) 724525 [1002.3110].

- G. Leung, E.R.M. Tarrant, C.T. Byrnes and E.J. Copeland, Reheating, Multifield Inflation and the Fate of the Primordial Observables, JCAP 09 (2012) 008 [1206.5196].

- S. Enomoto and T. Matsuda, Curvaton mechanism after multifield inflation, Phys. Rev. D 87 (2013) 083513 [1303.7023].

- C. Vafa, The String landscape and the swampland, hep-th/0509212.

- T.D. Brennan, F. Carta and C. Vafa, The String Landscape, the Swampland, and the Missing Corner, PoS TASI2017 (2017) 015 [1711.00864].

- H. Ooguri and C. Vafa, On the Geometry of the String Landscape and the Swampland, Nucl. Phys. B 766 (2007) 21 [hep-th/0605264].

- M. Etheredge, B. Heidenreich, S. Kaya, Y. Qiu and T. Rudelius, Sharpening the Distance Conjecture in diverse dimensions, JHEP 12 (2022) 114 [2206.04063].

- G. Payeur, E. McDonough and R. Brandenberger, Swampland conjectures constraints on dark energy from a highly curved field space, Phys. Rev. D 110 (2024) 106011 [2405.05304].

- G. Obied, H. G. Obied, H. Ooguri, L. Spodyneiko and C. Vafa, De Sitter Space and the Swampland, 1806.08362.

- D. Andriot, On the de Sitter swampland criterion, Phys. Lett. B 785 (2018) 570 [1806.10999].

- S. Renaux-Petel and K. Turzyński, Geometrical Destabilization of Inflation, Phys. Rev. Lett. 117 (2016) 141301 [1510.01281].

- R. Kallosh and A. Linde, New models of chaotic inflation in supergravity, JCAP 11 (2010) 011 [1008.3375].

- J.-O. Gong and T. Tanaka, A covariant approach to general field space metric in multi-field inflation, JCAP 03 (2011) 015 [1101.4809].

- R. Kallosh, A. R. Kallosh, A. Linde and D. Roest, Large field inflation and double α-attractors, JHEP 08 (2014) 052 [1405.3646].

- D. Wands, Primordial perturbations from inflation, in 5th RESCEU International Symposium on New Trends in Theoretical and Observations Cosmology, pp. 1–10, 1, 2002 [astro-ph/0201541].

- T. Moroi and T. Takahashi, Effects of cosmological moduli fields on cosmic microwave background, Phys. Lett. B 522 (2001) 215 [hep-ph/0110096].

- J.M. Maldacena, Non-Gaussian features of primordial fluctuations in single field inflationary models, JHEP 05 (2003) 013 [astro-ph/0210603].

- R. Bravo, S. Mooij, G.A. Palma and B. Pradenas, A generalized non-Gaussian consistency relation for single field inflation, JCAP 05 (2018) 024 [1711.02680].

- G. Dvali, A. G. Dvali, A. Gruzinov and M. Zaldarriaga, A new mechanism for generating density perturbations from inflation, Phys. Rev. D 69 (2004) 023505 [astro-ph/0303591].

- X. Chen, Primordial Non-Gaussianities from Inflation Models, Adv. Astron. 2010 (2010) 638979 [1002.1416].

- J. Kristiano and J. Yokoyama, Comparing sharp and smooth transitions of the second slow-roll parameter in single-field inflation, JCAP 10 (2024) 036 [2405.12145].

- D.I. Kaiser, E.A. D.I. Kaiser, E.A. Mazenc and E.I. Sfakianakis, Primordial Bispectrum from Multifield Inflation with Nonminimal Couplings, Phys. Rev. D 87 (2013) 064004 [1210.7487].

- M. Alvarez et al., Testing Inflation with Large Scale Structure: Connecting Hopes with Reality, 1412.4671.

- A.R. Brown, Hyperbolic Inflation, Phys. Rev. Lett. 121 (2018) 251601 [1705.03023].

- A. Achúcarro and Y. Welling, Orbital Inflation: inflating along an angular isometry of field space, 1907.02020.

- T. Bjorkmo, Rapid-Turn Inflationary Attractors, Phys. Rev. Lett. 122 (2019) 251301 [1902.10529].

- S. Dimopoulos, S. Kachru, J. McGreevy and J.G. Wacker, N-flation, JCAP 08 (2008) 003 [hep-th/0507205].

- R. Easther and L. McAllister, Random matrices and the spectrum of N-flation, JCAP 05 (2006) 018 [hep-th/0512102].

- A.D. Linde, Chaotic Inflation, Phys. Lett. B 129 (1983) 177.

- P. Christodoulidis, D. Roest and E.I. Sfakianakis, Scaling attractors in multi-field inflation, JCAP 12 (2019) 059 [1903.06116].

- P. Christodoulidis, D. Roest and R. Rosati, Many-field Inflation: Universality or Prior Dependence?, JCAP 04 (2020) 021 [1907.08095].

- J. Fumagalli, S. Garcia-Saenz, L. Pinol, S. Renaux-Petel and J. Ronayne, Hyper-Non-Gaussianities in Inflation with Strongly Nongeodesic Motion, Phys. Rev. Lett. 123 (2019) 201302 [1902.03221].

- O. Grocholski, M. Kalinowski, M. Kolanowski, S. Renaux-Petel, K. Turzyński and V. Vennin, On backreaction effects in geometrical destabilisation of inflation, JCAP 05 (2019) 008 [1901.10468].

- M. Dias, J. Frazer and M.c.D. Marsh, Seven Lessons from Manyfield Inflation in Random Potentials, JCAP 01 (2018) 036 [1706.03774].

- R. Bousso, Precision cosmology and the landscape, in Amazing Light: Visions for Discovery: An International Symposium in Honor of the 90th Birthday Years of Charles H. Townes, 10, 2006 [hep-th/0610211].

- P. Christodoulidis, D. Roest and E.I. Sfakianakis, Angular inflation in multi-field α-attractors, JCAP 11 (2019) 002 [1803.09841].

- P. Christodoulidis, R. P. Christodoulidis, R. Rosati and E.I. Sfakianakis, Robust non-minimal attractors in many-field inflation, 2504.12406.

- E. McDonough, A.H. Guth and D.I. Kaiser, Nonminimal Couplings and the Forgotten Field of Axion Inflation, 2010.04179.

- D. Langlois and S. Renaux-Petel, Perturbations in generalized multi-field inflation, JCAP 04 (2008) 017 [0801.1085].

- A. Achúcarro, R. Kallosh, A. Linde, D.-G. Wang and Y. Welling, Universality of multi-field α-attractors, JCAP 04 (2018) 028 [1711.09478].

- P. Christodoulidis, D. Roest and E.I. Sfakianakis, Attractors, Bifurcations and Curvature in Multi-field Inflation, JCAP 08 (2020) 006 [1903.03513].

- R. Kallosh, A. Linde and D. Roest, Superconformal Inflationary α-Attractors, JHEP 11 (2013) 198 [1311.0472].

- Y.-F. Cai, X. Chen, M.H. Namjoo, M. Sasaki, D.-G. Wang and Z. Wang, Revisiting non-Gaussianity from non-attractor inflation models, JCAP 05 (2018) 012 [1712.09998].

- R. Bravo and G.A. Palma, Unifying attractor and nonattractor models of inflation under a single soft theorem, Phys. Rev. D 107 (2023) 043524 [2009.03369].

- S. Clesse, Hybrid inflation along waterfall trajectories, Phys. Rev. D 83 (2011) 063518 [1006.4522].

- J.-O. Gong and M. Sasaki, Waterfall field in hybrid inflation and curvature perturbation, JCAP 03 (2011) 028 [1010.3405].

- H. Kodama, K. Kohri and K. Nakayama, On the waterfall behavior in hybrid inflation, Prog. Theor. Phys. 126 (2011) 331 [1102.5612].

- A.D. Linde, Hybrid inflation, Phys. Rev. D 49 (1994) 748 [astro-ph/9307002].

- J.-O. Gong, Multi-field inflation and cosmological perturbations, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 26 (2016) 1740003 [1606.06971].

- K.D. Olum, Is there any coherent measure for eternal inflation?, Phys. Rev. D 86 (2012) 063509 [1202.3376].

- S. Brahma and S. Shandera, Stochastic eternal inflation is in the swampland, JHEP 11 (2019) 016 [1904.10979].

- M. Tegmark, The multiverse hierarchy, 2009.

- A.D. Linde, Eternally Existing Selfreproducing Chaotic Inflationary Universe, Phys. Lett. B 175 (1986) 395.

- A. Vilenkin, Predictions from quantum cosmology, Phys. Rev. Lett. 74 (1995) 846 [gr-qc/9406010].

- A.D. Linde, D.A. Linde and A. Mezhlumian, Do we live in the center of the world?, Phys. Lett. B 345 (1995) 203 [hep-th/9411111].

- M. Tegmark, What does inflation really predict?, JCAP 04 (2005) 001 [astro-ph/0410281].

- R. Bousso, B. Freivogel and I.-S. Yang, Boltzmann babies in the proper time measure, Phys. Rev. D 77 (2008) 103514 [0712.3324].

- D.N. Page, Return of the Boltzmann Brains, Phys. Rev. D 78 (2008) 063536 [hep-th/0611158].

- A.D. Linde and A. Mezhlumian, Stationary universe, Phys. Lett. B 307 (1993) 25 [gr-qc/9304015].

- A.D. Linde, D.A. Linde and A. Mezhlumian, From the Big Bang theory to the theory of a stationary universe, Phys. Rev. D 49 (1994) 1783 [gr-qc/9306035].

- S. Winitzki, A Volume-weighted measure for eternal inflation, Phys. Rev. D 78 (2008) 043501 [0803.1300].

- R. Bousso, B. Freivogel, S. Leichenauer and V. Rosenhaus, Boundary definition of a multiverse measure, Phys. Rev. D 82 (2010) 125032 [1005.2783].

- I. Huston and A.J. Christopherson, Isocurvature Perturbations and Reheating in Multi-Field Inflation, 1302.4298.

- R. Allahverdi et al., The First Three Seconds: a Review of Possible Expansion Histories of the Early Universe, Open J. Astrophys. 4 (2021) astro.2006.16182 [2006.16182].

- A.A. Starobinsky and J. Yokoyama, Equilibrium state of a self-interacting scalar field in the de sitter background, Phys. Rev. D 50 (1994) 6357.

- J. Grain and V. Vennin, Stochastic inflation in phase space: Is slow roll a stochastic attractor?, JCAP 05 (2017) 045 [1703.00447].

- S.A. Kim and A.R. Liddle, N-flation: Multifield inflationary dynamics and perturbations. Phys. Rev. D 2006, 74, 023513. [CrossRef]

- N. Kaloper and A.R. Liddle, Dynamics and perturbations in assisted chaotic inflation, Phys. Rev. D 61 (2000) 123513 [hep-ph/9910499].

- A.R. Liddle, A. Mazumdar and F.E. Schunck, Assisted inflation, Phys. Rev. D 58 (1998) 061301 [astro-ph/9804177].

- S.M. Carroll and J. Chen, Spontaneous inflation and the origin of the arrow of time, hep-th/0410270.

- G.N. Remmen and S.M. Carroll, How Many e-Folds Should We Expect from High-Scale Inflation?, Phys. Rev. D 90 (2014) 063517 [1405.5538].

- N. Tetradis, Fine tuning of the initial conditions for hybrid inflation, Phys. Rev. D 57 (1998) 5997 [astro-ph/9707214].

- A. Belfiglio, O. Luongo and S. Mancini, Quantum entanglement in cosmology, 2506.03841.

- V.F. Mukhanov, Quantum Theory of Gauge Invariant Cosmological Perturbations, Sov. Phys. JETP 67 (1988) 1297.

- C. Kiefer, D. Polarski and A.A. Starobinsky, Quantum to classical transition for fluctuations in the early universe, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 7 (1998) 455 [gr-qc/9802003].

- N. Bolis, T. Fujita, S. Mizuno and S. Mukohyama, Quantum Entanglement in Multi-field Inflation, JCAP 09 (2018) 004 [1805.09448].

- D. Boyanovsky, Effective field theory during inflation: Reduced density matrix and its quantum master equation, Phys. Rev. D 92 (2015) 023527 [1506.07395].

- J.-c. Hwang and H. Noh, Cosmological perturbations with multiple scalar fields, Phys. Lett. B 495 (2000) 277 [astro-ph/0009268].

- D. Polarski and A.A. Starobinsky, Semiclassicality and decoherence of cosmological perturbations, Class. Quant. Grav. 13 (1996) 377 [gr-qc/9504030].

- J.J. Halliwell, Decoherence in quantum cosmology, Phys. Rev. D 39 (1989) 2912.

- L.P. Grishchuk and Y.V. Sidorov, Squeezed quantum states of relic gravitons and primordial density fluctuations, Phys. Rev. D 42 (1990) 3413.

- D. Campo and R. Parentani, Decoherence and entropy of primordial fluctuations. I: Formalism and interpretation, Phys. Rev. D 78 (2008) 065044 [0805.0548].

- D. Campo and R. Parentani, Decoherence and entropy of primordial fluctuations II. The entropy budget, Phys. Rev. D 78 (2008) 065045 [0805.0424].

- T. Prokopec and G.I. Rigopoulos, Decoherence from Isocurvature perturbations in Inflation, JCAP 11 (2007) 029 [astro-ph/0612067].

- K. Boutivas, D. Katsinis, G. Pastras and N. Tetradis, Entanglement in cosmology, JCAP 04 (2024) 017 [2310.17208].

- J. Weenink and T. Prokopec, On decoherence of cosmological perturbations and stochastic inflation, 1108.3994.

- D. Langlois and B. van Tent, Isocurvature modes in the CMB bispectrum, JCAP 07 (2012) 040 [1204.5042].

- A.M. Green, Primordial black holes as a dark matter candidate - a brief overview, Nucl. Phys. B 1003 (2024) 116494 [2402.15211].

- A.L. Miller, Gravitational wave probes of particle dark matter: a review, 2503.02607.

- W.H. Kinney, Horizon crossing and inflation with large eta, Phys. Rev. D 72 (2005) 023515 [gr-qc/0503017].

- J. Martin, H. Motohashi and T. Suyama, Ultra Slow-Roll Inflation and the non-Gaussianity Consistency Relation, Phys. Rev. D 87 (2013) 023514 [1211.0083].

- J. Garcia-Bellido and E. Ruiz Morales, Primordial black holes from single field models of inflation, Phys. Dark Univ. 18 (2017) 47 [1702.03901].

- J.M. Ezquiaga, J. Garcia-Bellido and E. Ruiz Morales, Primordial Black Hole production in Critical Higgs Inflation, Phys. Lett. B 776 (2018) 345 [1705.04861].

- K. Kannike, L. Marzola, M. Raidal and H. Veermäe, Single Field Double Inflation and Primordial Black Holes, JCAP 09 (2017) 020 [1705.06225].

- C. Germani and T. Prokopec, On primordial black holes from an inflection point, Phys. Dark Univ. 18 (2017) 6 [1706.04226].

- H. Motohashi and W. Hu, Primordial Black Holes and Slow-Roll Violation, Phys. Rev. D 96 (2017) 063503 [1706.06784].

- H. Di and Y. Gong, Primordial black holes and second order gravitational waves from ultra-slow-roll inflation, JCAP 07 (2018) 007 [1707.09578].

- G. Ballesteros and M. Taoso, Primordial black hole dark matter from single field inflation, Phys. Rev. D 97 (2018) 023501 [1709.05565].

- C. Pattison, V. Vennin, H. Assadullahi and D. Wands, Quantum diffusion during inflation and primordial black holes, JCAP 10 (2017) 046 [1707.00537].

- S. Passaglia, W. Hu and H. Motohashi, Primordial black holes and local non-Gaussianity in canonical inflation, Phys. Rev. D 99 (2019) 043536 [1812.08243].

- C.T. Byrnes, P.S. Cole and S.P. Patil, Steepest growth of the power spectrum and primordial black holes, JCAP 06 (2019) 028 [1811.11158].

- M. Biagetti, G. Franciolini, A. Kehagias and A. Riotto, Primordial Black Holes from Inflation and Quantum Diffusion, JCAP 07 (2018) 032 [1804.07124].

- P. Carrilho, K.A. Malik and D.J. Mulryne, Dissecting the growth of the power spectrum for primordial black holes, Phys. Rev. D 100 (2019) 103529 [1907.05237].

- K. Inomata, E. McDonough and W. Hu, Amplification of primordial perturbations from the rise or fall of the inflaton, JCAP 02 (2022) 031 [2110.14641].

- K. Inomata, E. McDonough and W. Hu, Primordial black holes arise when the inflaton falls, Phys. Rev. D 104 (2021) 123553 [2104.03972].

- C. Pattison, V. Vennin, D. Wands and H. Assadullahi, Ultra-slow-roll inflation with quantum diffusion, JCAP 04 (2021) 080 [2101.05741].

- X. Gao, D. Langlois and S. Mizuno, Oscillatory features in the curvature power spectrum after a sudden turn of the inflationary trajectory, JCAP 10 (2013) 023 [1306.5680].

- S.S. Mishra and V. Sahni, Primordial Black Holes from a tiny bump/dip in the Inflaton potential, JCAP 04 (2020) 007 [1911.00057].

- S.R. Geller, W. Qin, E. McDonough and D.I. Kaiser, Primordial black holes from multifield inflation with nonminimal couplings, Phys. Rev. D 106 (2022) 063535 [2205.04471].

- B. Carr and F. Kuhnel, Primordial black holes as dark matter candidates, SciPost Phys. Lect. Notes 48 (2022) 1 [2110.02821].

- S. Kasuya and M. Kawasaki, Axion isocurvature fluctuations with extremely blue spectrum, Phys. Rev. D 80 (2009) 023516 [0904.3800].

- D.I. Kaiser, Conformal Transformations with Multiple Scalar Fields, Phys. Rev. D 81 (2010) 084044 [1003.1159].

- K. Schutz, E.I. Sfakianakis and D.I. Kaiser, Multifield Inflation after Planck: Isocurvature Modes from Nonminimal Couplings, Phys. Rev. D 89 (2014) 064044 [1310.8285].

- D.I. Kaiser and E.I. Sfakianakis, Multifield Inflation after Planck: The Case for Nonminimal Couplings, Phys. Rev. Lett. 112 (2014) 011302 [1304.0363].

- A.E. Romano, S.A. Vallejo-Peña and K. Turzyński, Model-independent approach to effective sound speed in multi-field inflation, Eur. Phys. J. C 82 (2022) 767 [2006.00969].

- G. Gelmini and P. Gondolo, Neutralino with the right cold dark matter abundance in (almost) any supersymmetric model, Phys. Rev. D 74 (2006) 023510.

- T. Moroi and L. Randall, Wino cold dark matter from anomaly mediated SUSY breaking, Nucl. Phys. B 570 (2000) 455 [hep-ph/9906527].

- M. Viel, G.D. Becker, J.S. Bolton and M.G. Haehnelt, Warm dark matter as a solution to the small scale crisis: New constraints from high redshift Lyman-α forest data, Phys. Rev. D 88 (2013) 043502 [1306.2314].

- J. Chluba and R.A. Sunyaev, The evolution of CMB spectral distortions in the early Universe, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 419 (2012) 1294 [1109.6552].

- H. Niikura et al., Microlensing constraints on primordial black holes with Subaru/HSC Andromeda observations, Nature Astron. 3 (2019) 524 [1701.02151].

- K.N. Ananda, C. Clarkson and D. Wands, The Cosmological gravitational wave background from primordial density perturbations, Phys. Rev. D 75 (2007) 123518 [gr-qc/0612013].

- NANOGrav collaboration, The NANOGrav 12.5 yr Data Set: Search for an Isotropic Stochastic Gravitational-wave Background, Astrophys. J. Lett. 905 (2020) L34 [2009.04496].

- M. Beltran, J. Garcia-Bellido and J. Lesgourgues, Isocurvature bounds on axions revisited, Phys. Rev. D 75 (2007) 103507 [hep-ph/0606107].

- J.-O. Gong, N. Kitajima and T. Terada, Curvaton as dark matter with secondary inflation, JCAP 03 (2017) 053 [1611.08975].

- G. D’Amico, N. Kaloper and A. Westphal, General double monodromy inflation, Phys. Rev. D 105 (2022) 103527 [2112.13861].

- C. Cheung, P. Creminelli, A.L. Fitzpatrick, J. Kaplan and L. Senatore, The Effective Field Theory of Inflation, JHEP 03 (2008) 014 [0709.0293].

- J. Butterfield, Emergence, reduction and supervenience: A varied landscape, Foundations of Physics 41 (2011) 920–959 [1106.0704].

- L. Kofman, A.D. Linde and A.A. Starobinsky, Towards the theory of reheating after inflation, Phys. Rev. D 56 (1997) 3258 [hep-ph/9704452].

- N. Bartolo et al., Science with the space-based interferometer LISA. IV: Probing inflation with gravitational waves, JCAP 12 (2016) 026 [1610.06481].

- J.D. Jackson, Classical Electrodynamics, Wiley (1998).

- S. Weinberg, The Quantum theory of fields. Vol. 1: Foundations, Cambridge University Press (6, 2005), 10.1017/CBO9781139644167.

- H. Georgi, Effective field theory, Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 43 (1993) 209.

- A. Vilenkin, Many Worlds in One: The Search for Other Universes, Farrar, Straus and Giroux (2007).

| 1 | For a conceptual discussion on the nature and definition of fields in the context of multifield inflation, see App. Appendix A. |

| 2 | See [69] for a discussion regarding the stability of flat potentials against quantum corrections, [70] examines how realizing SR often entails tuning model parameters, even in simple monomial or polynomial potentials, and [71] argues that the early universe’s remarkable smoothness is not best captured by the horizon or flatness problems but by the fact that, under a natural measure on cosmological histories conditioned on late-time observations, almost all trajectories are wildly inhomogeneous at early times—making our universe’s initial state extraordinarily fine-tuned. |

| 3 | However, this attractor behavior may depend on the underlying gravitational formulation: for instance, in multifield -attractor models, the metric formulation exhibits attractor behavior in the large-coupling limit, while the Palatini formulation does not [80]. |

| 4 | These challenges include issues such as backreaction from branes or fluxes, the potential flattening required for SR conditions, and the difficulty of stabilizing moduli without spoiling inflationary dynamics. Moreover, achieving trans-Planckian field excursions in a controlled setting often leads to tensions with the Weak Gravity Conjecture and related swampland criteria; see, [82,83,84]. |

| 5 | As emphasized in [92], the presence of multiple light fields fundamentally alters the post-inflationary dynamics. Unlike in single-field models, where predictions are robust and largely independent of reheating details, multifield scenarios require careful treatment of reheating and entropy transfer processes. This opens a novel window into particle physics beyond the Standard Model through cosmological observations. However, it also enlarges the parameter space and weakens some of the model-independent appeal of single-field inflation. The authors highlight the exciting opportunity that future data from missions like Planck, LSST, and the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) will offer in probing such multifield effects. |

| 6 | The measure problem in eternal inflation remains unresolved. As [142] argues, the infinities generated by eternal inflation render probabilities ill-defined, and no measure satisfying reasonable axioms has yet been found that is fully acceptable. Similarly, surveys by [35] and others highlight deep mathematical ambiguities in regularizing the diverging spacetime volume, noting that different cutoff schemes yield dramatically different predictions. |

| 7 | This scenario underlies what Max Tegmark classifies as a Level II multiverse, where different “bubble" universes arise with varying low-energy physics due to eternal inflation populating a landscape of vacua [144]. Tegmark’s multiverse hierarchy extends to Level III (quantum many-worlds) and Level IV (the mathematical universe hypothesis). He also discusses the measure problem, a deep challenge in assigning probabilities in an infinite multiverse. Foundational work on eternal inflation and its implications for a multiverse was independently developed by Andrei Linde and Alexander Vilenkin [145,146]. |

| 8 | [168] develops a general formalism to describe quantum entanglement between scalar field perturbations in multi-field inflation. They construct entangled initial states by expressing the in-vacuum as an excited state of the out-vacuum via Bogoliubov transformations involving multiple creation and annihilation operators. Their analysis shows that multi-field dynamics can naturally lead to entangled quantum states and oscillatory features in the power spectrum, offering potential observational signatures. |

| 9 | In this expression, the operator ⨂ denotes the tensor product, a mathematical operation that combines the state spaces of different fields into a single composite Hilbert space. Concretely, the tensor product corresponds to a state where each field’s perturbations are independent and uncorrelated with the others, forming a product (separable) state. The inequality indicates that, in general, the actual full density matrix is not equal to this simple tensor product of individual field density matrices. This reflects the presence of quantum entanglement and correlations between the different fields, which must be accounted for when analyzing decoherence and the emergence of classicality in multifield inflationary models. |

| 10 | [170] presented a complete gauge-ready formulation of multi-field perturbation equations and showed that adiabatic and isocurvature modes decouple on super-horizon scales under SR when field-space curvature is neglected. [19] demonstrates that this decoupling cannot, in general, be assumed when the background trajectory is curved even in SR inflation models, highlighting the importance of curvature-induced adiabatic–entropy mixing. |

| 11 | For a comprehensive overview of gravitational-wave probes of particle DM, see [181]. |

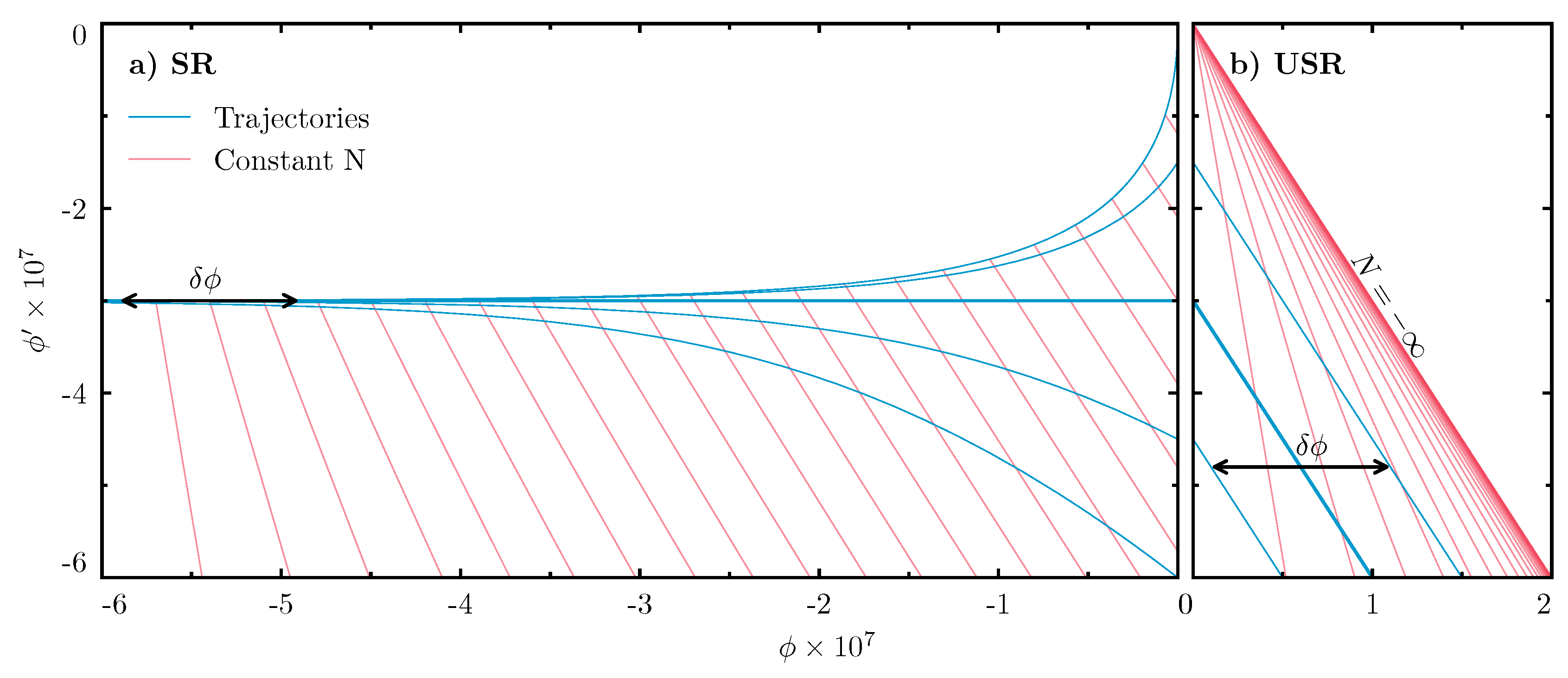

| 12 | USR inflation refers to a brief phase during inflation where the inflaton field experiences a nearly flat potential region, leading to a significant departure from the usual SR conditions. In this regime, the inflaton’s velocity decreases rapidly due to Hubble friction, and the usual relation between the curvature perturbation and the inflaton potential breaks down. As a result, curvature perturbations on superhorizon scales can grow significantly, even exponentially, which is in stark contrast to the conserved behavior in standard SR. This makes USR an attractive mechanism for generating the large enhancements in the curvature power spectrum, , necessary for PBHs formation. However, achieving a sustained and controlled USR phase typically demands a delicate tuning of the inflationary potential, such as constructing an inflection point or a near-plateau feature, which often raises concerns about naturalness and stability in single-field models. For a detailed discussion, see [182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198]. |

| 13 |

The function appearing in Eq. (49) is the complementary error function, defined as

It quantifies the probability that a Gaussian-distributed variable exceeds a certain threshold. In the context of PBHs formation, it captures the exponentially suppressed probability that the curvature perturbation exceeds the critical threshold necessary for gravitational collapse. Since is typically modeled as a Gaussian random field with variance , the fraction of regions collapsing into PBHs of mass M, denoted , is highly sensitive to the amplitude of . Even a small increase in around the relevant scale can dramatically enhance , making a powerful diagnostic of sharp features or amplification mechanisms in multifield inflation.

|

| Aspect | Single-field | Multifield |

|---|---|---|

| Quantum fluctuation criterion | ||

| Attractor structure | Unique | Manifold of attractors |

| Isocurvature degrees | Absent | Present; slow or fast decay |

| Measure ambiguities | Severe | Modulated by field-space geometry |

| Exit channels | Unique or tunneling | Rich network of transitions |

| Model | Mechanism | Compatible? |

|---|---|---|

| Curvaton | Post-inflation decay of light field | Yes, if |

| Hybrid (waterfall) | Sudden field drop with reheating | Often Yes |

| Axion inflation | Axionic isocurvature survives | Often No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).