1. Introduction

Vibrating feeders are short vibrating conveyors with the trough vibration provided by a harmonic vibration source, the so-called vibration exciter [

1]. The vibration exciter is usually implemented as a forced drive by a crank mechanism [

2,

3]; as a drive by a mechanical exciter with unbalances [

4,

5,

6] or as an electromagnetic drive [

7,

8].

The aim of the measurements carried out in this paper has been to verify the assumption whether the monitoring of vibrations (using vibrating sensors) transmitted to the supporting frame of a vibrating feeder can provide information about its operating characteristics.

The information, i.e. the electrical signals, detected by the vibration sensors can be used to diagnose the working operation of vibrating feeders in locations that may be in a considerable distance from where the vibrating feeder is installed. Such diagnostics of vibrating feeder parameters can provide controllers in the control centre with the information on whether the required amount of material is on the trough of the vibrating feeder, whether the vibrating feeder is in an optimal operating state or in a fault state.

P. Czubak et al. in their paper [

9] analyse the influence of such parameters as the weight of the conveyed material and frequency on the reduction of vibration transmission to the bottom layer. They have come to the conclusion that the choice of optimal parameters, such as accurate calibration of spring stiffness, selection of materials with high absorption capacity and correct sizing of vibration elements, can significantly contribute to reducing vibration transmission to the substrate.

W. Surówka and P. Czubak in their paper [

10] describe the operational behaviour of vibrating conveyors at resonance and its impact on the efficiency of material conveying.

Experimental tests have been carried out using two vibration sensors. One sensor has been installed on the trough of the vibrating feeder, the other on its supporting frame.

The vibrating feeder was equipped with an electromagnetic vibration exciter, the basic part of which consists of an electromagnet, which consists of an armature, a core and a coil with a given number of coil turns. An electromagnet [

11] is coil with a core of magnetically soft steel used to create a temporary magnetic field. The principle consists in transforming energy of the electromagnetic field into the mechanical energy. The magnetic force [

12] is generated when an electric current passes through the winding of a coil on a steel core, which attracts a movable part, called the armature. The magnetic flux of the electromagnet and the attractive force of the electromagnet depend directly on the magnitude of the electric current I [A] flowing through the coil, the number of coil turns N

c [–] and indirectly on the length δ [m] of the air gap between the core and the armature [

13,

14,

15]. In practice, the attractive force is limited by the total magnetic conductivity of the electromagnet core and the magnetic flux dissipation [

16].

The trough with a horizontally situated bottom (trough inclination angle β = 0 deg) was mechanically (by means of screw connections) attached to the end parts of four mounted pieces of leaf springs, each L

s = 88 mm, obliquely (at an angle α = 30 deg). The solenoid coil of the electromagnetic exciter has been powered from an amplitude/frequency controller (FQ1 DIG Process Controller) [

17].

In the paper [

18] V. Korendiy et al. present theoretical modelling and experimentally obtained data (defining the influence of design parameters on the operational stability and transport efficiency) for the assessment of dynamic properties of vibrating conveyors.

G. Cieplok in his paper [

19] declares by numerical simulations the ability of easier control of undesired resonant vibrations by optimizing the geometry of the vibratory drive parameters.

The maximum attractive force F

max [N] of the electromagnet [

20,

21,

22] can be determined according to Eq. (1) assuming that the permeability of the vacuum μ

0 [H·m

–1] (μ

0 = 1.257 [N·A

–2]) is known, the magnetic induction in the air gap B

δ [T] and the cross-section of the contact area of the electromagnet core S [m

2].

The cross-section S [m

2] of the contact surface of the electromagnet core of the electromagnetic exciter of the vibratory feeder described in this paper is specified in

Figure 1.

If the distance of the armature δ [m] from the electromagnet core, the number of coil turns N

c [‒] and the current I [A] flowing through the electromagnet coil, the permeability of the vacuum μ

0 [H·m

–1], the contact surface of the electromagnet core S [m

2] are known, it is possible to express the attractive force F

h [N] of the electromagnet by the relation (2).

The property of a coil is characterized by its inductance L [H]. The inductance is a physical quantity expressing the ability of an electrically conducting body flowing with an electric current to generate a magnetic field in its surroundings. A coil with a larger inductance acts in an AC circuit in such a way that it generates higher resistance to the current. This is due to the fact that the coil induces a voltage directed by its own induction against the voltage of the source. A magnetic field periodically appears and disappears in the coil, so there is no heating of the coil. The action of the coil on the alternating current is characterized by the quantity of inductive reactance (inductance XL [Ω].

Since the voltage induced in the coil also depends on the rate, at which the alternating current changes, it is obvious that the inductance also depends on the frequency of the alternating current. The greater the frequency of the AC current, the greater the inductance of the coil. The coil of inductance L [H] has inductance XL [Ω], in an AC circuit, for which the relation (1) applies.

With AC single-phase electromagnets [

23,

24] the current is determined by the resistance and self-inductance of the coil, which depends on the position of the armature. If the resistance of the coil is negligible with respect to its reactance, the magnetic flux will be constant and the electromagnet will induce a constant pull at any position of the armature. Resistance, which cannot be neglected, will manifest itself by altering this ideal tensile characteristic. In the initial position, when the air gap is large, the coil impedance is low and the coil draws a high current. The voltage drop induced on the coil resistance will cause the voltage drop across the reactance generates a significantly weaker magnetic flux [

25]. Therefore, the initial thrust will be relatively small. If the air gap decreases, the reactance of the coil increases, the current and voltage drop across the coil resistance decreases, the voltage across the reactance increases, and therefore the thrust increases because the magnetic flux corresponding to the voltage across the reactance gradually increases.

In electromagnetic exciters, the effect of the excitation force is induced by the dynamic force generated during the straight-line reciprocating uniform motion of the metal armature of the electromagnet [

26]. The armature of the electromagnet is firmly connected to the trough. The core of the solenoid is connected to the exciter body via pre-tensioned springs.

If the exciter is supplied with AC current at a frequency of 50 Hz, the trough oscillates at a frequency of 100 Hz. If we include a frequency rectifier in the circuit, the oscillation of the exciter is reduced by half and oscillates only at 50 Hz frequency [

27].

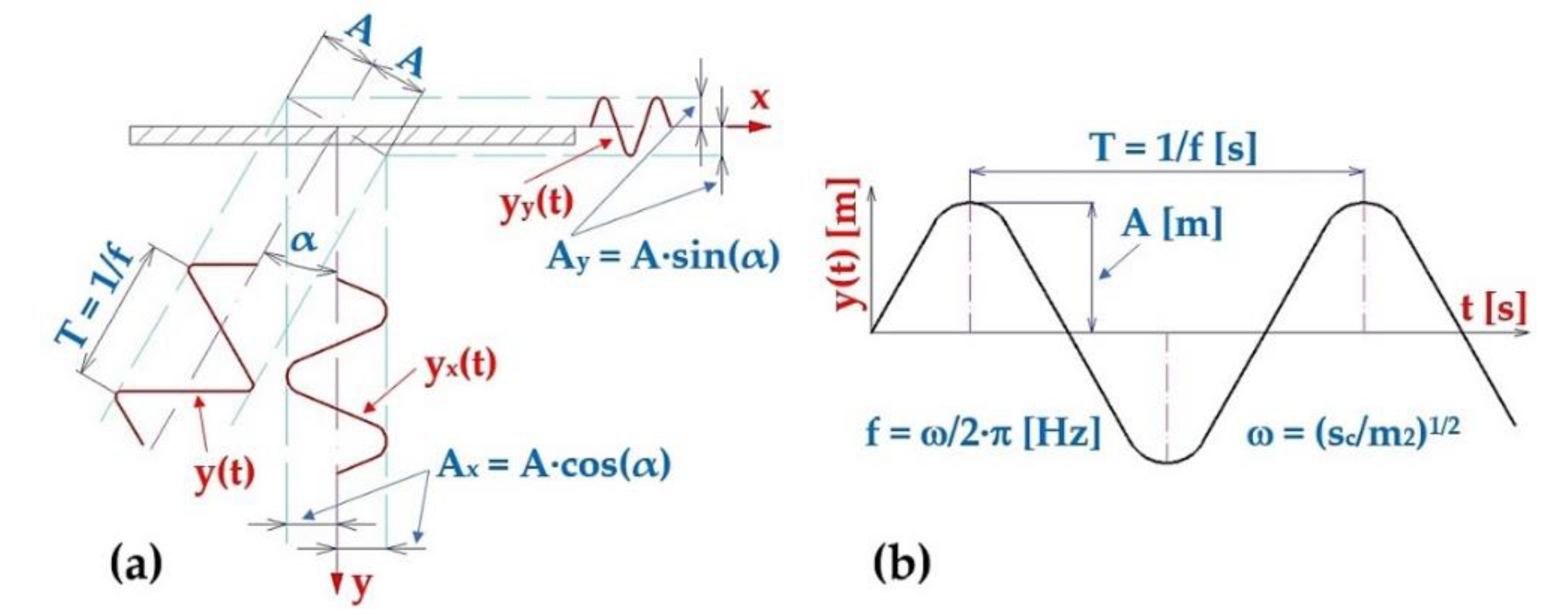

A simple harmonic motion [

28] is the typical motion of a mass on a spring when subjected to a linear elastic reciprocating force given by Hooke's law. The motion is sinusoidal in time and exhibits a single resonant frequency [

29].

A mass oscillating by harmonic motion has one resonant frequency determined by its spring constant s

c [N·m

–1] and mass m

2 [kg]. Using the Hooke's law, neglecting damping and the mass of the spring, the Newton's second law produces the equation of motion (4).

The solution of differential equation (4) has the form (5).

where "B" is the integration constant. By substituting the equation (5) into equation (4 ), we obtain (6).

The integration constant "B" can be expressed from the assumption, see

Figure 2, saying that if

then

. By substituting this consideration into the equation (6 ), we obtain (7).

The constant "B" (7) defines the elongation y(t) [m] (8) of the leaf spring of stiffness s

c [N·m

–1] due to the mass m

2 [kg]. The harmonic oscillation of a trough mounted on springs of total stiffness s

c [N·m

‒1] is caused by the force F(t) [N] (8), the magnitude of which is directly proportional to the deflection y(t) [m] and is oriented towards the equilibrium position at each instant.

S. Ogonowski and P. Krauze describe in [

30] how the dynamic properties of magnetorheological dampers and the motion trajectory of vibration devices can be influenced by the magnetic field control.

The authors M. Pesík and P. Němeček in their paper [

31] analyse various types of vibration isolation elements (such as rubber dampers, spring systems and viscous dampers) and evaluate their effectiveness (reduction of vibration transmission to the structural frame and bottom layer) in various operating conditions of vibrating conveyors.

4. Discussion

The vibration of the trough, a vibrating feeder with an electromagnetic vibration exciter, see

Figure 7(b), supported by leaf springs (made of FR4 Epoxy, Steel or Plastic PCCF materials) is transmitted through these springs to the steel frame of the vibrating feeder. The magnitude of the vibrations transmitted to the frame of the vibrating feeder varies and depends on the stiffnes s

c [N·mm

–1] of the used springs (see Chapter 2.2 and Chapter 3.2). If the spring stiffnesses are chosen appropriately, the vibrations transmitted to the vibrating feeder frame are multiple times lower than the vibration of the trough. The vibration of the trough is generated by a source of harmonic vibrations, the so-called vibration exciter. In this paper, an electromagnetic oscillator was used as an exciter for the measuring device (see Chapter 2.3).

The obtained results confirm the conclusion that it is possible to reduce the transmission of vibrations to the bottom layer in vibrating conveyors using leaf springs, presented in the article [

42] by J. Michalczyk and P. Czubak.

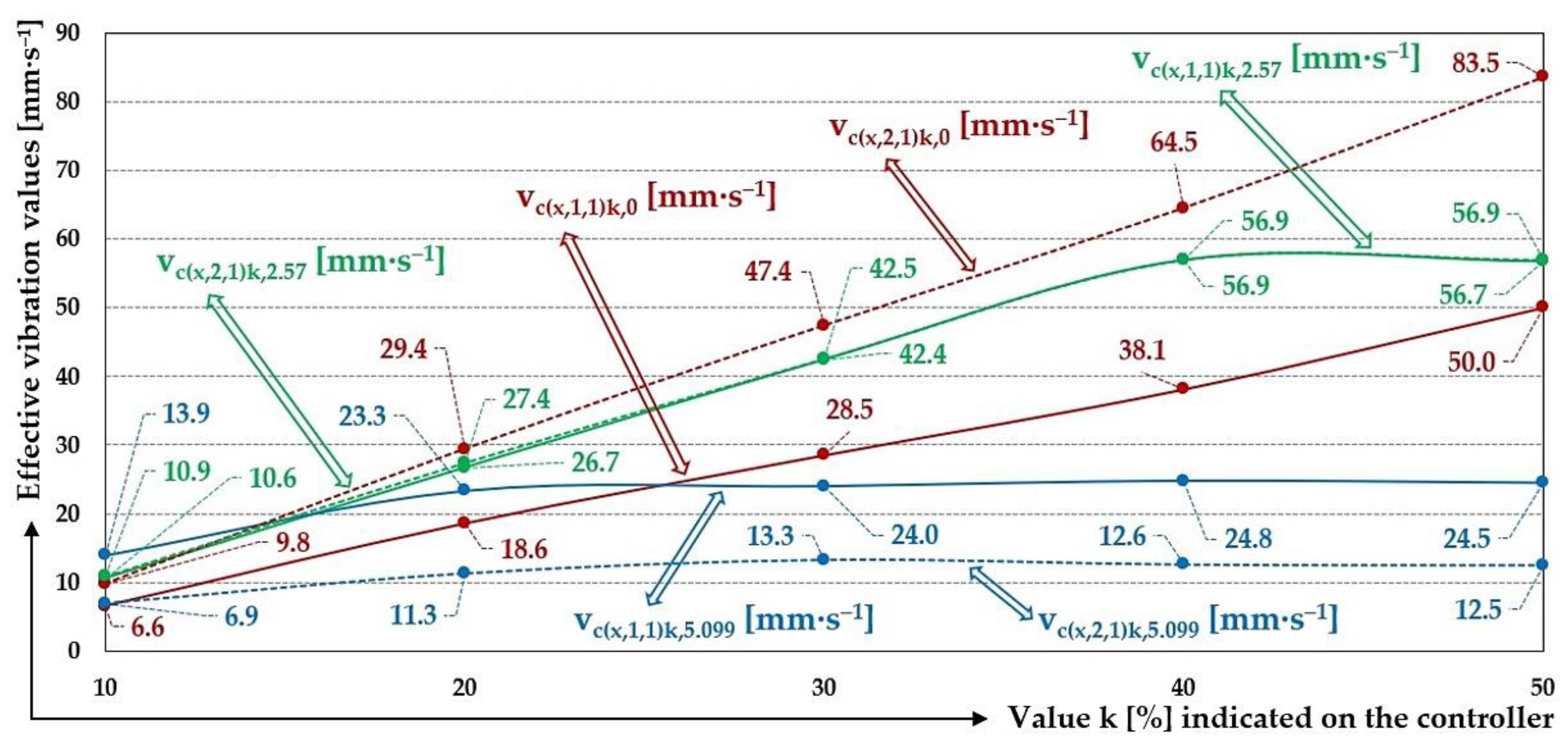

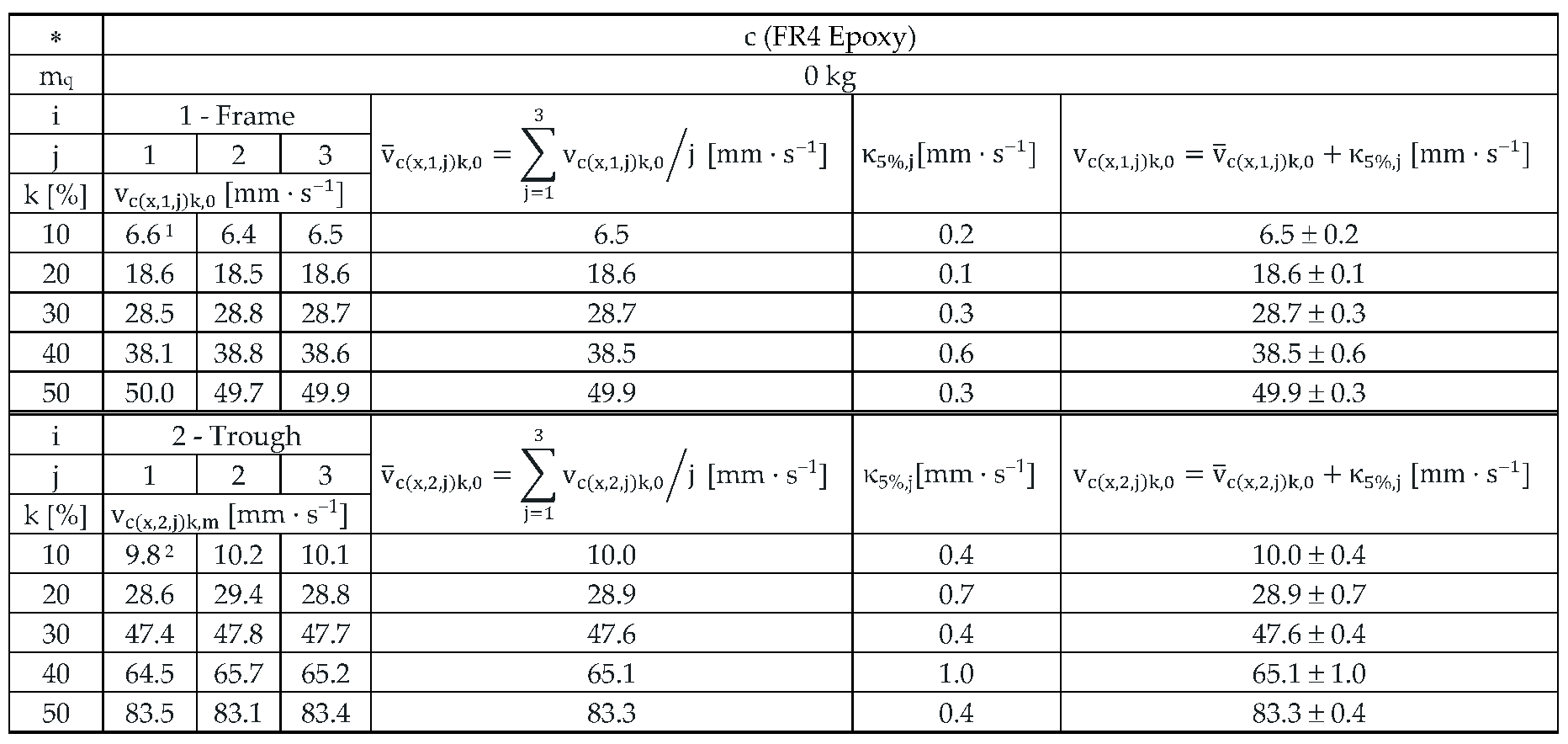

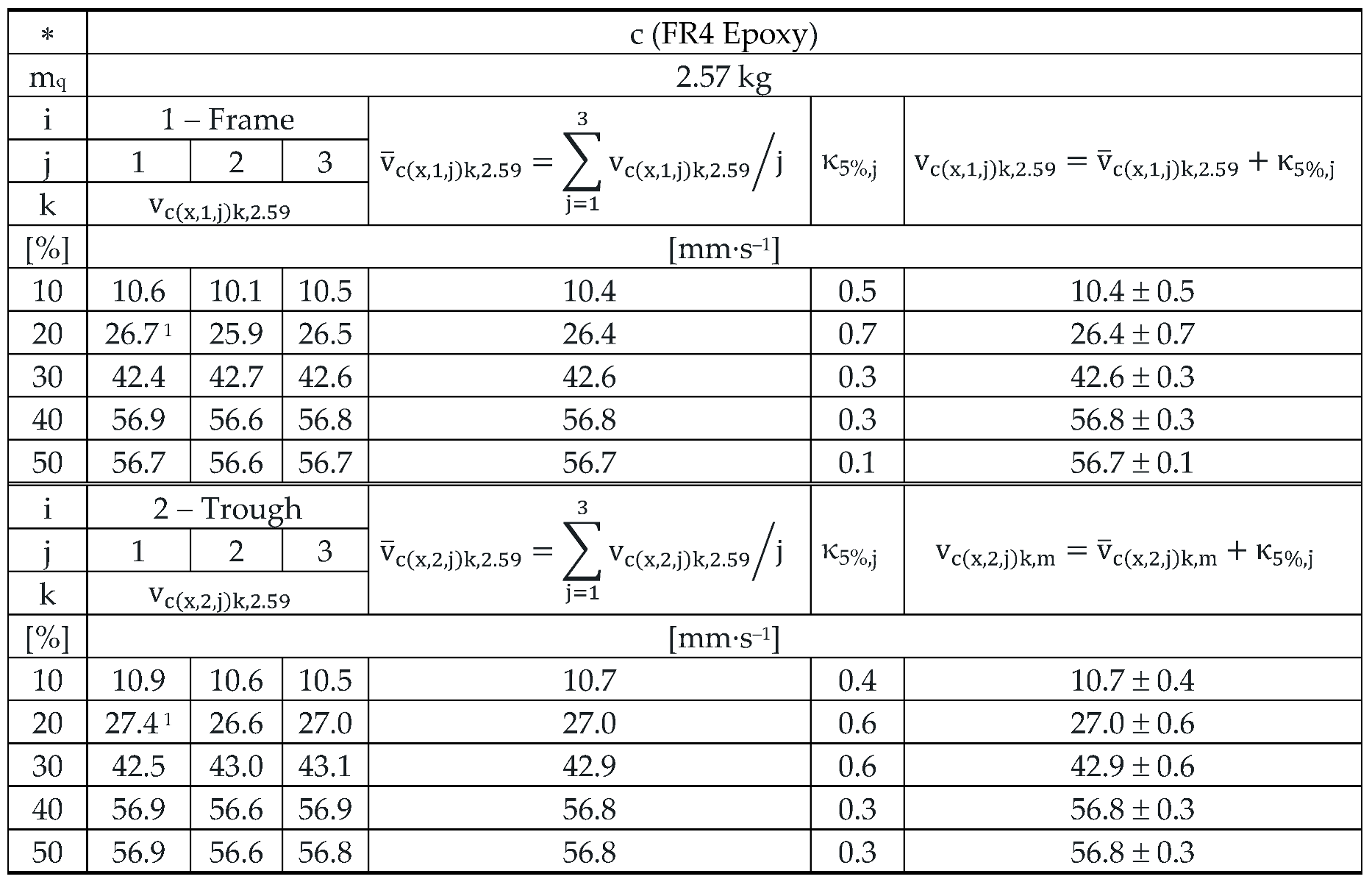

The measurements of the effective vibration velocities (see Chapter 3.3) indicate that when using leaf springs made of FR4 Epoxy (optimally chosen stiffness of leaf springs), with a total stiffness of s

cc = 47.8 N·mm

–1, the vibration of the trough is higher in the case of an unloaded trough with conveyed material (the owne weight of the trough m

z = 3.37 kg), see

Table 9 and

Figure 21, and lower in the case when there is material on the trough (m

q = 2.57 kg or 5.099 kg), see

Table 10,

Table 11 and

Figure 21.

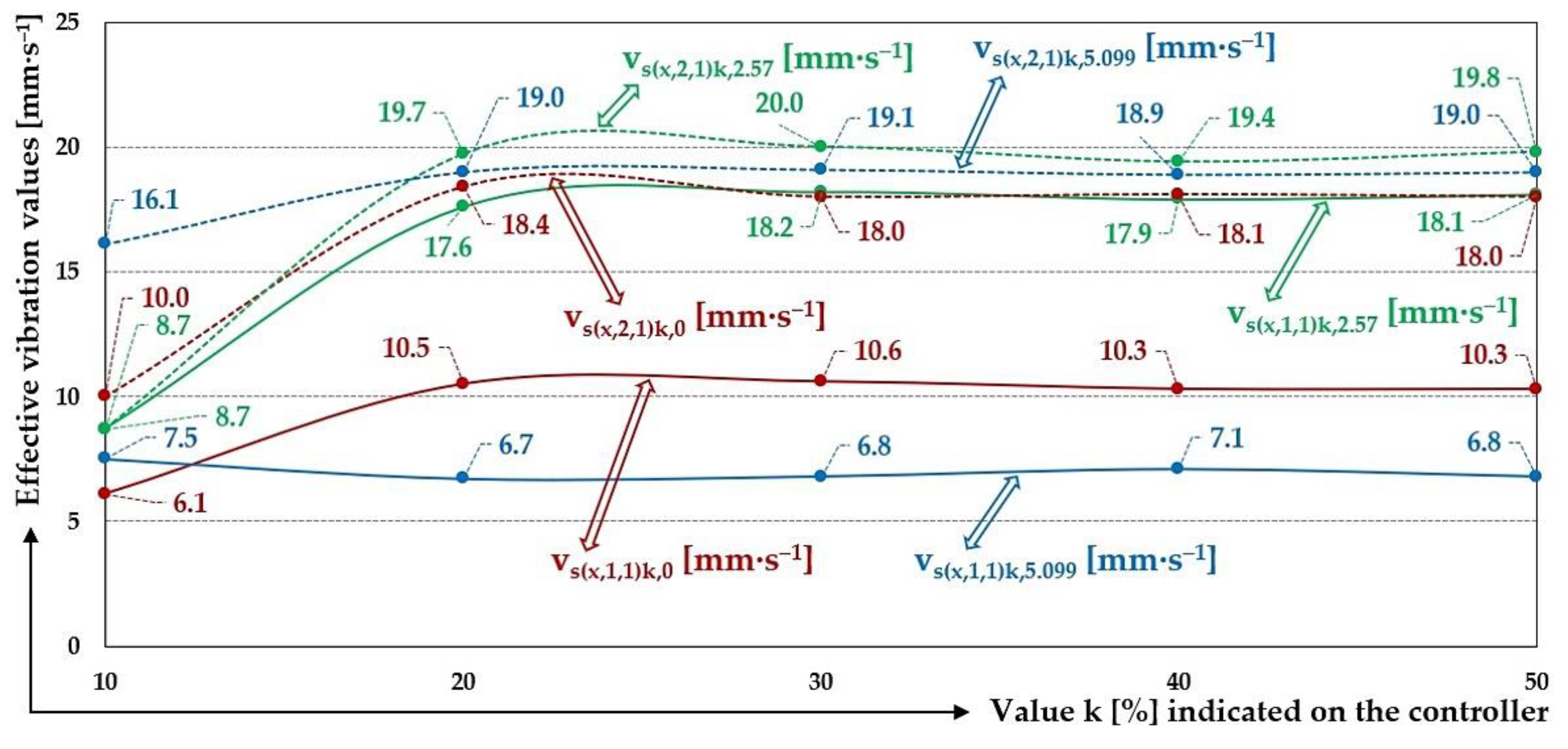

When using leaf springs made of steel (high stiffness of leaf springs), with a total stiffness of s

cs = 107.1 N·mm

–1, the vibration of the trough is higher when the trough is not loaded with the material being conveyed, see

Table 12 and

Figure 22, as well as when there is material loaded on the trough (m

q = 2.57 kg or 5.099 kg), see

Table 13,

Table 14 and

Figure 22.

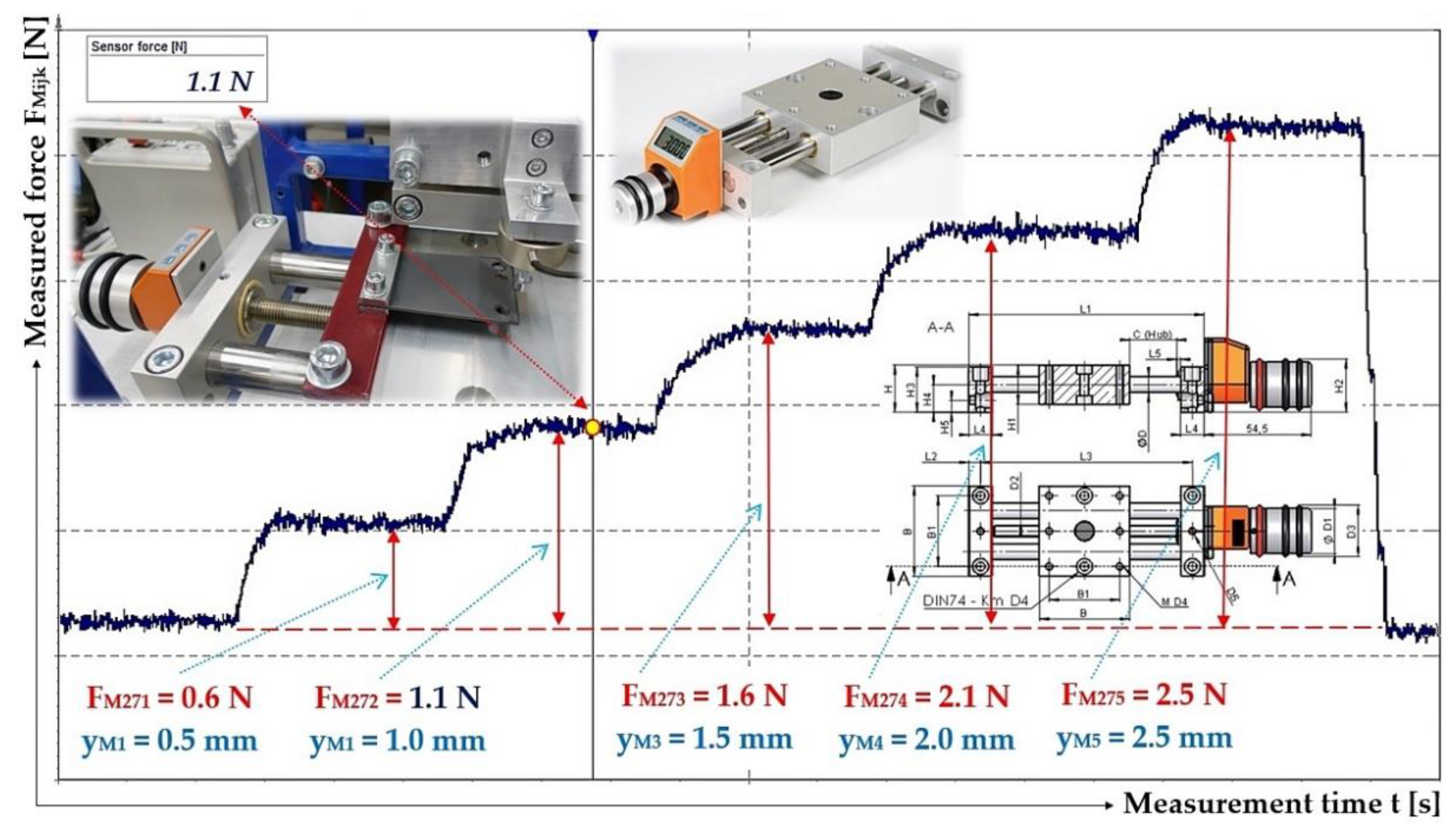

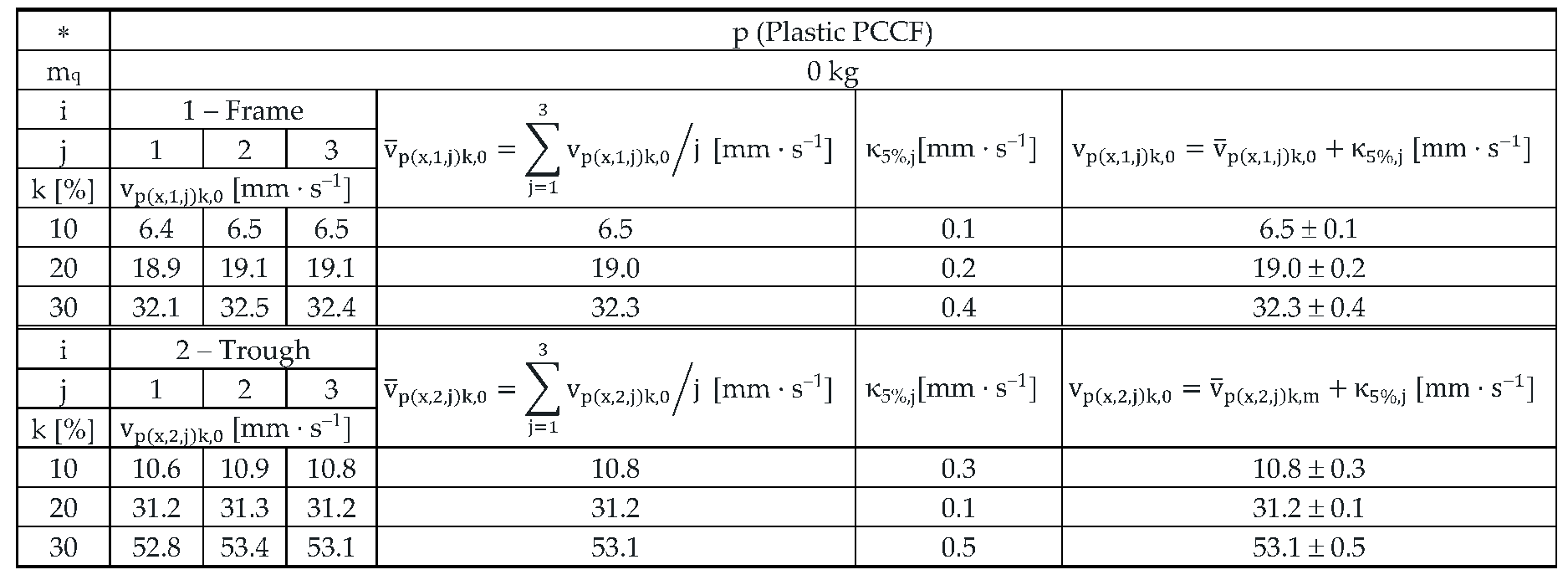

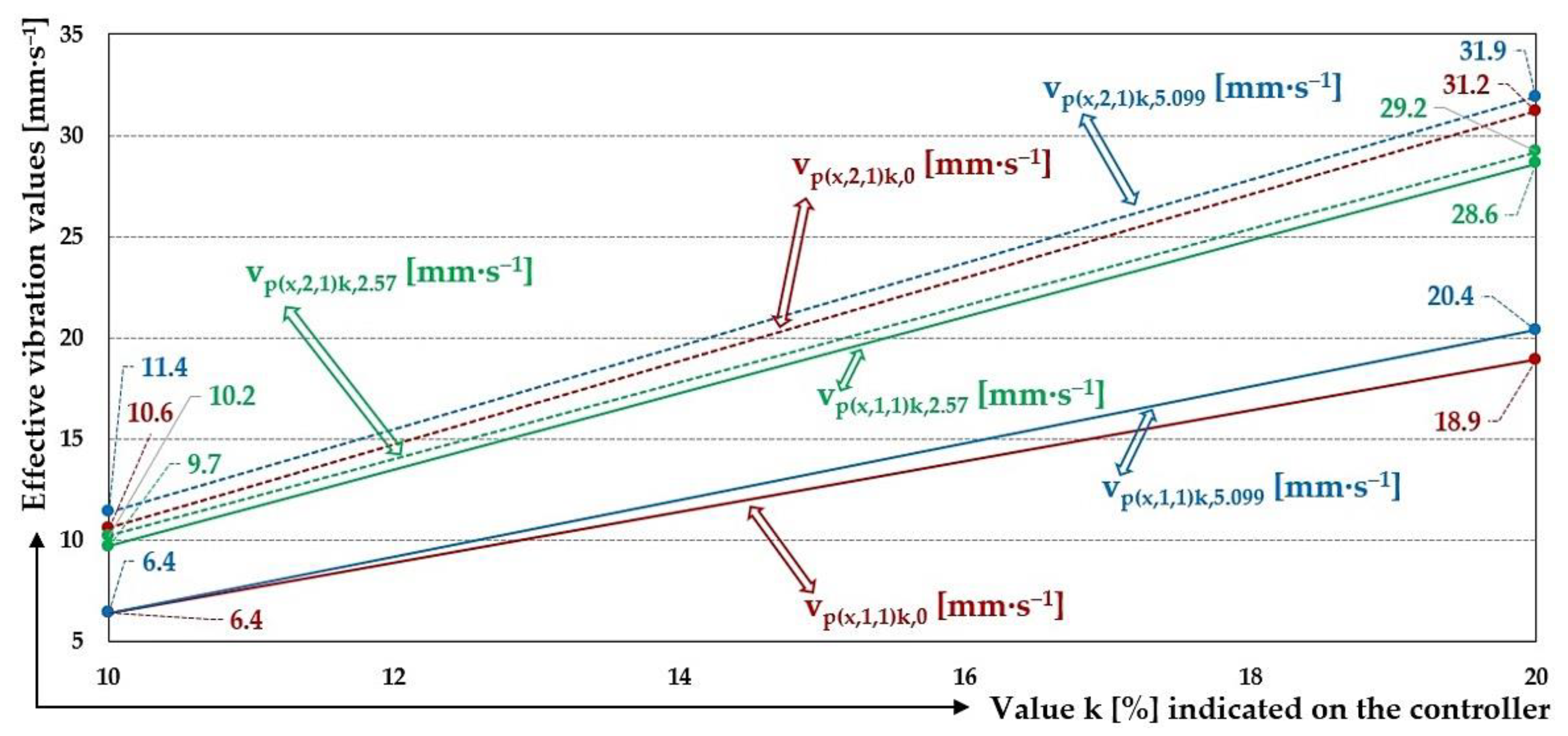

When using Plastic PCCF leaf springs (low stiffness leaf springs), with a total stiffness of s

cp = 4.4 N·mm

‒1, the vibration of the trough is also higher when the trough is unloaded with material (trough dead weight m

z = 3.37 kg), see

Table 15 and

Figure 23, and when there is material on the trough (m

q = 2.57 kg or 5.099 kg), see

Table 16,

Table 17 and

Figure 23.

To analyse and justify whether the signals obtained by the acceleration sensors (i.e. the measured effective vibration speeds) can be used to remotely diagnose the working condition of the vibrating feeder, the measured values of the effective spring vibration speeds for k = 40% only, indicated in

Table 9 to

Table 11, will be examined in more detail.

The measured values, when using leaf springs made of FR4 Epoxy and zero filling of the vibrating feeder trough with the conveyed material (m

q = 0 kg) indicate that the effective vibration velocity detected on the steel frame of the vibrating feeder reaches the value of 38.5 mm·s

–1 (see

Table 9) and on the trough 65.1 mm·s

–1. On the steel frame, the effective vibration velocity takes 59.1% of the value of the effective vibration velocity measured on the trough.

With the mass of material to be conveyed on the trough m

q = 2.57 kg, both the effective vibration velocities measured on the steel frame and on the trough are the same 56.8 mm·s

‒1, see

Table 10.

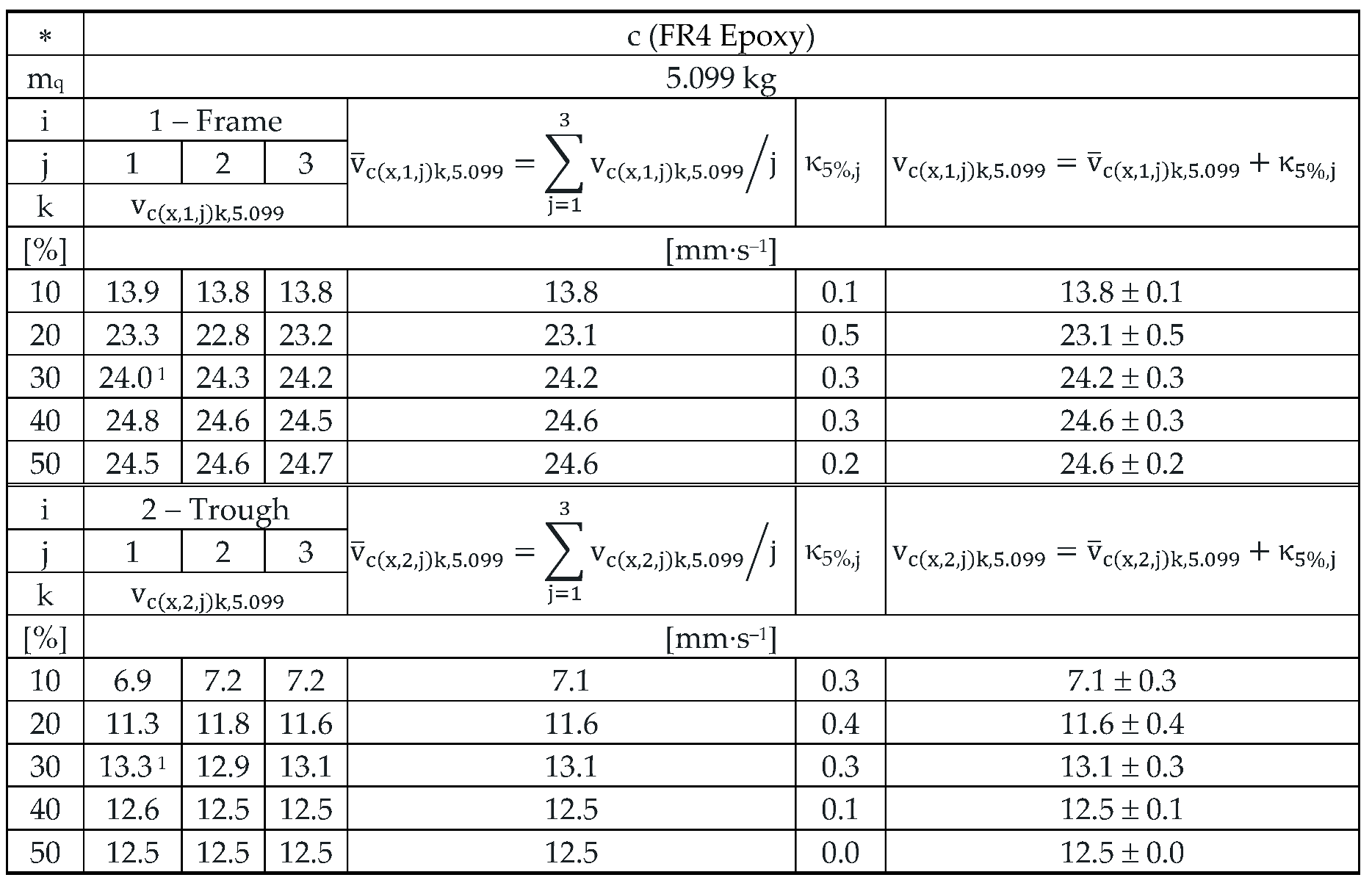

With a conveyed material mass on the trough of m

q = 5.099 kg, the mean value of the effective vibration velocity measured on the steel frame is 24.6 mm·s

–1 and on the trough 12.5 mm·s

–1, see

Table 11. On a steel frame, the effective vibration velocity takes 50.8% of the value of the effective vibration relocity measured on the trough.

For leaf springs with optimum stiffness (material FR4 Epoxy − s

cc = 47.8 N·mm

–1) it applies that the mean values of the measured effective vibration velocities take the highest value (65.1 mm·s

–1 see

Table 9) and decrease with increasing mass of material on the trough (56.8 mm·s

–1 pro m

q = 2.57 kg, see

Table 10 and 12.5 mm·s

‒1 for m

q = 5.099 kg, see

Table 11).

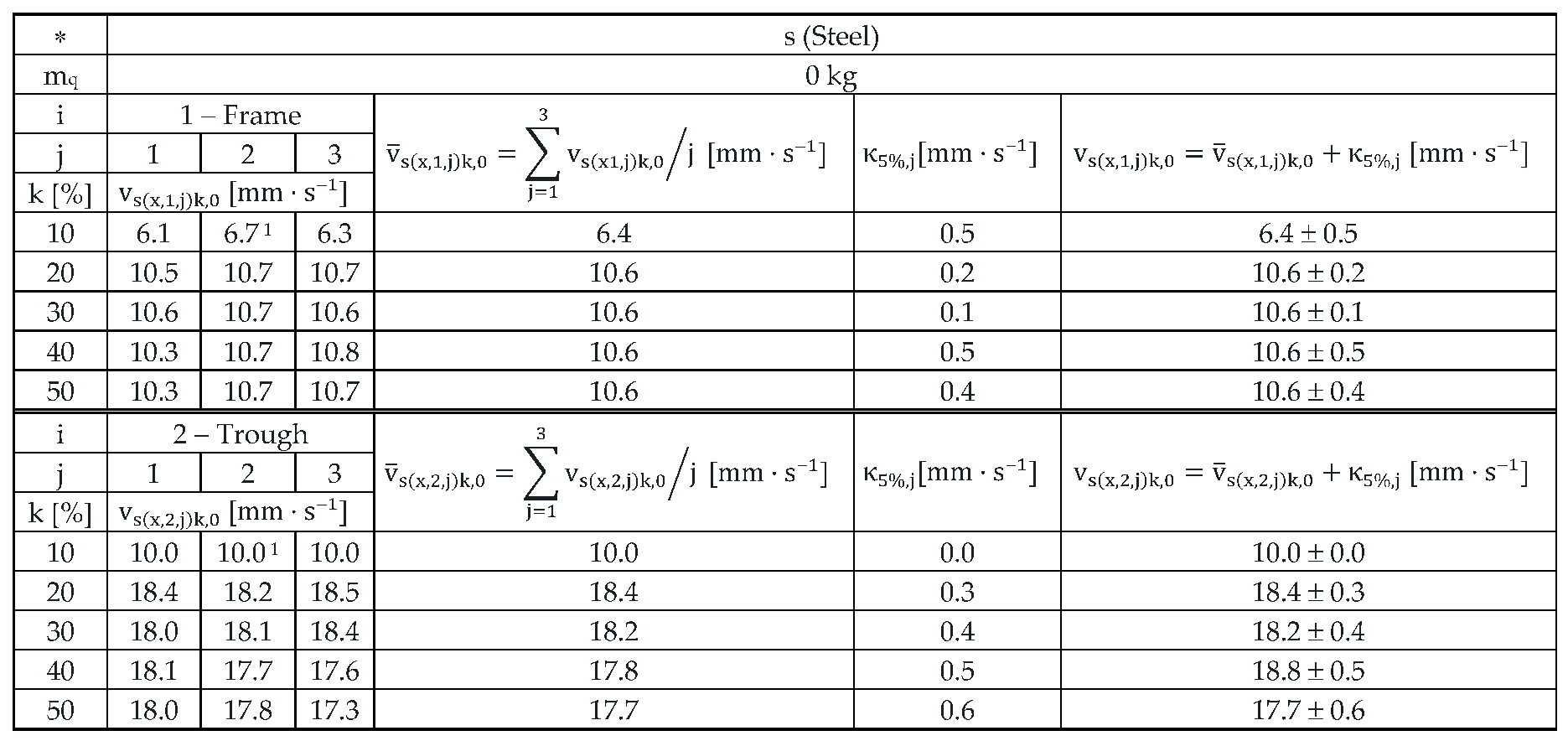

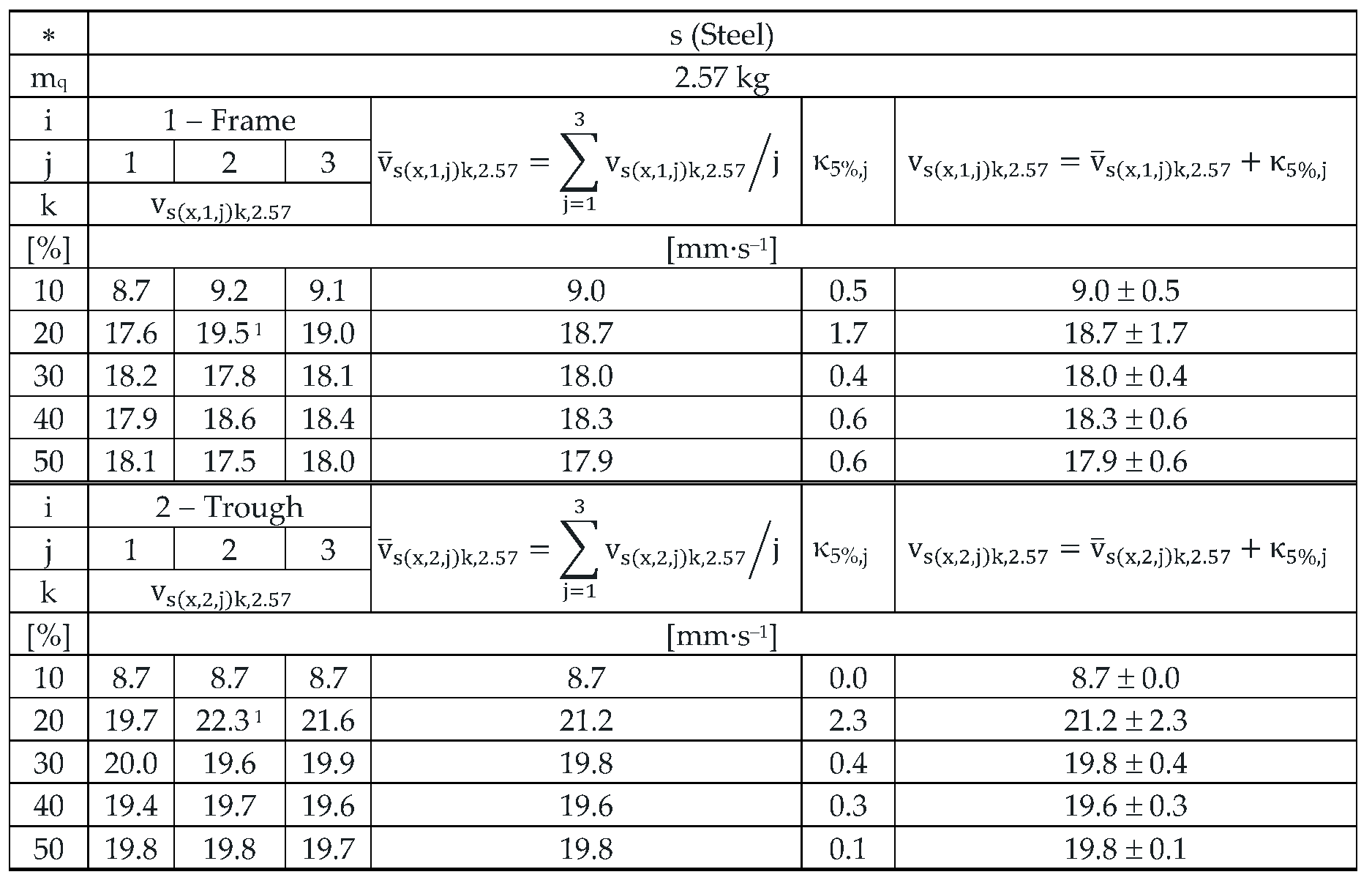

The measured values of the effective vibration velocities, when using leaf springs made of Steel, (see

Table 12 to

Table 14) alo indicate (according to the mean values of the effective vibration velocities) whether or not the material to be conveyed is on the trough and what mass size it takes on.

On the steel frame; at k = 40% and at zero filling of the trough of the vibrating feeder with the conveyed material (mq = 0 kg); the value of the mean effective vibration velocity was measured to be 10.6 mm·s–1 and 18.8 mm·s–1 on the trough, respectively, using steel springs. Thus, on the steel frame, the effective vibration velocity is 56.4% of the effective vibration velocity measured on the trough.

With the weight of the material conveyed on the trough mq = 2.57 kg, the mean value of the effective vibration velocity measured on the steel frame is 93.4% of the value of the effective vibration velocity measured on the trough.

With the weight of the material conveyed on the trough mq = 5.099 kg, the mean value of the effective vibration velocity measured on the steel frame is 37.4% of the value of the effective vibration velocity measured on the trough.

For leaf springs that have high stiffness (material Steel − s

cs = 107.1 N·mm

–1) it applies that the mean values of the measured effective vibration velocities are the lowest (18.8 mm·s

–1 see

Table 12) in the absence of the conveyed material on the trough and increase with increasing weight of the material on the trough (19.6 mm·s

–1 pro m

q = 2.57 kg, see

Table 13 and 19.0 mm·s

–1 for m

q = 5.099 kg, see

Table 14).

Measured values of the effective vibration velocities when using leaf springs made of Plastic PCCF (see

Table 15 to

Table 17) also indicate that it can be predicted from the measured values of the effective vibration velocities whether or not there is material (and if so and of what mass size) to be conveyed on the trough of the vibrating feeder.

During the measurements carried out on the laboratory device, i.e. a vibrating feeder with an electromagnetic vibration exciter, using low stiffness leaf springs (s

cp = 4.4 N·mm

–1), it was not possible to set the amplitude/frequency controller - FQ1 DIG Process Controller [

17] to higher values of k [%] than 20%. This was due to the low stiffness of the leaf springs (made of Plastic PCCF), which caused the armature to come into contact with the core of the electromagnet – a situation that is unacceptable in electromagnetic exciters used in practice.

On the steel frame; at k = 20% and with zero filling of the vibrating feeder trough with the conveyed material (mq = 0 kg); the value of the mean effective vibration velocity has been measured to be 31.2 mm·s–1 and 19.0 mm·s–1 at the trough. Thus, on a steel frame, the effective vibration velocity reaches 60.9% of the effective vibration velocity measured on the trough.

With the weight of the material conveyed on the trough mq = 2.57 kg, the mean value of the effective vibration velocity measured on the steel frame is 97.2% of the value of the effective vibration velocity measured on the trough.

With the weight of the material conveyed on the trough mq = 5.099 kg, the mean value of the effective vibration velocity measured on the steel frame is 62.2% of the value of the effective vibration velocity measured on the trough.

Based on the above conclusions of the measured values of the effective vibration velocities (see

Table 9 to

Table 17 and

Figure 21 to

Figure 23), it can be predicted with a high degree of probability that it is possible to estimate remotely whether or not there is material being conveyed on the trough of the vibrating feeder and also that there is a larger or smaller mass quantity of material on the trough.

Conclusion: From the measurements carried out in the article [

4] by L. Hrabovský et al. it can be traced that with inappropriately selected stiffnesses of springs supporting the trough of the vibrating conveyor, it can be traced from the analysis of vibration signals (transmitted to the machine frame) generated by sensors that the vibration of a loaded trough (m

m > 0 kg) is higher than the vibration of an unloaded trough (m

m = 0 kg) of the vibrating conveyor.

From the analysis of the measured values presented in Chapter 3.3 it can be concluded that by monitoring the vibrations (using vibration sensors) transmitted to the supporting frame of the vibrating feeder, information about its working properties can be obtained, thus confirming the intended objective of the conducted experiments.

The information, i.e. the electrical signals, detected by the vibration sensors can be used to diagnose the working operation of vibrating feeders in locations that may be in a considerable distance from where the vibrating feeder is installed. Such diagnostics of vibrating feeder parameters can provide controllers in the control centre with the information on whether the required amount of material is on the trough of the vibrating feeder, whether the vibrating feeder is in an optimal operating state or in a fault state.

5. Conclusions

In the presented paper, the tables indicate the effective vibration velocity values obtained by measurements, detected by acceleration sensors, on the trough surface and on the frame of the vibrating feeder model with electromagnetic vibration exciter. The trough of the vibrating conveyor is supported by three types of leaf springs, which differ in terms of their stiffness (spring characteristics). The harmonic oscillation of the trough is induced by an electromagnetic oscillator, the frequency and amplitude of oscillation of which is controlled by the controller (amplitude/frequency regulator – FQ1 DIG Process Controller).

The main objective of the realized signal measurements (which define the magnitude of the vibrations in three mutually perpendicular planes) was to determine whether (with varying input values, namely the amplitude of vibrations, the mass of the conveyed material) it is possible to obtain (from the measured magnitudes of the vibrations acting on the frame of the vibrating conveyor) information about the operating characteristics and the mass of material to be conveyed on the trough with respect to the stiffness of the rubber springs supporting the vibrating masses.

Acceleration magnitudes of the effective vibration velocity values measured by sensors have demonstrated and confirmed that if springs of a particular stiffness supporting the vibrating trough are selected appropriately, it is possible to remotely monitor the correct operational operation of the vibratory conveyor and to have information that the required mass quantity of conveyed/sorted material is on the trough of the vibratory machine.

Knowing the magnitude of the vibrations acting on the frame of a particular vibrating feeder (obtained by sensor measurements), with known values of the stiffness of the springs supporting the trough, it is also possible to trace the failure state of their working activities, or to obtain information about the failure or damage of the rubber or steel coil cylindrical springs (used on the vibrating machine).

Signals indicating the magnitude of the vibration values acting on the frame of vibrating conveyors/sorting machines, transmitted to the control station, allow remote monitoring of the operation of vibrating machines at any time without the need for physical inspection of these devices by authorized persons at a place of their installation.

The obtained data on the magnitudes of the measured signals detected by the vibration sensors allowed to confirm the correctness of the initial idea that (with appropriately designed machine parts) it is possible to monitor the proper working operation and the failure state of vibrating conveyors under operating conditions.

The current trend towards digitalization and computer-controlled or monitored optimum operation of conveyor handling equipment (including vibrating feeders) heavily relies on sensors, measuring equipment and digital signal transmission over any distance.

Figure 1.

Dimensional sketch of the electromagnet, a/b [m] - length/width of the electromagnet core, δ [m] - armature clearance (air gap).

Figure 1.

Dimensional sketch of the electromagnet, a/b [m] - length/width of the electromagnet core, δ [m] - armature clearance (air gap).

Figure 2.

Harmonic oscillation of the vibrating conveyor trough, (a) components yx(t) [m] a yy(t) [m] of the trough deflection, (b) harmonic oscillation parameters.

Figure 2.

Harmonic oscillation of the vibrating conveyor trough, (a) components yx(t) [m] a yy(t) [m] of the trough deflection, (b) harmonic oscillation parameters.

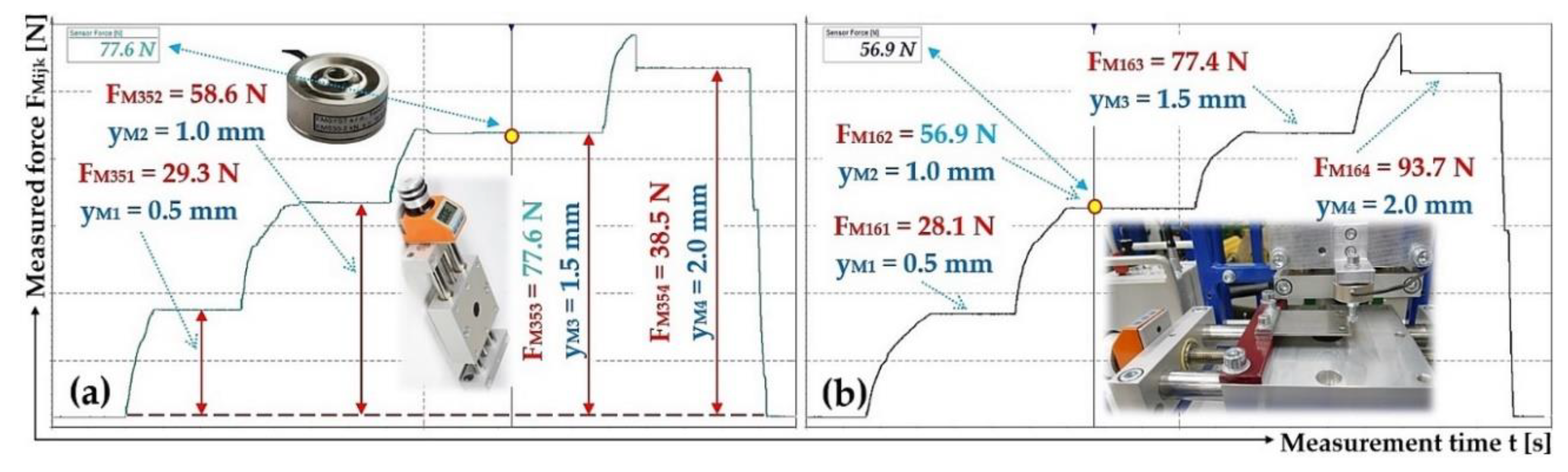

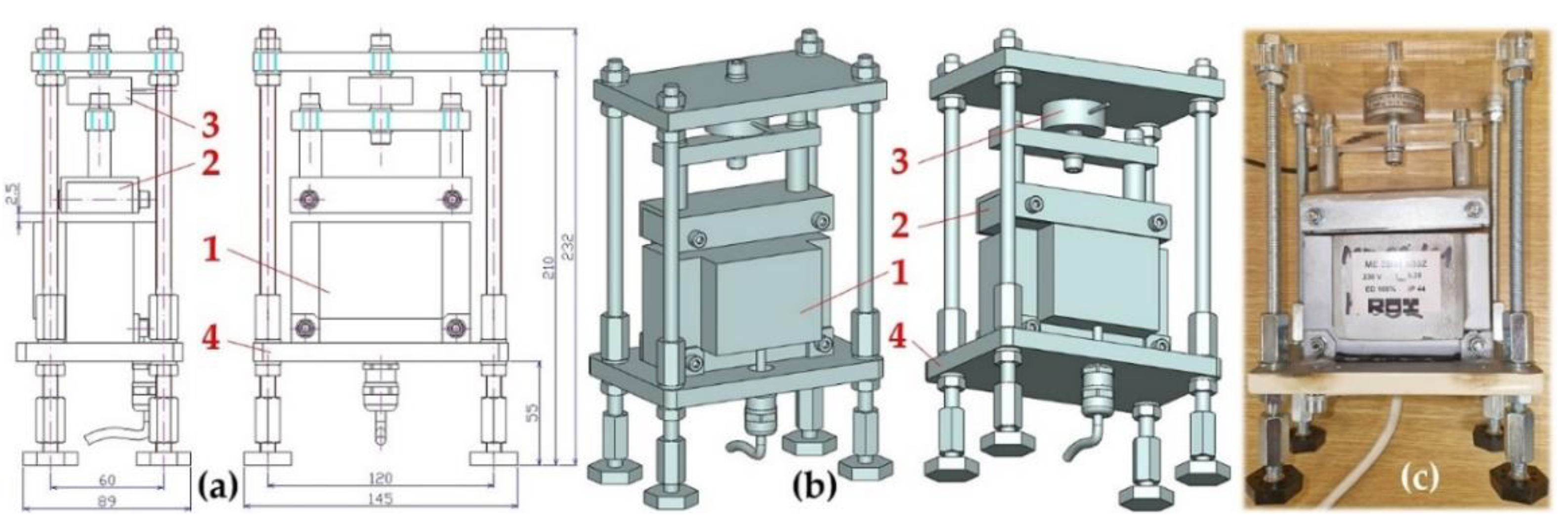

Figure 3.

Laboratory device for detecting the magnitude of the electromagnet's holding force (a) 2D dimensional sketch, (b) 3D model, (c) implementation. 1 ‒ electromagnet, 2 ‒ electromagnet armature, 3 ‒ force sensor, 4 ‒ support frame.

Figure 3.

Laboratory device for detecting the magnitude of the electromagnet's holding force (a) 2D dimensional sketch, (b) 3D model, (c) implementation. 1 ‒ electromagnet, 2 ‒ electromagnet armature, 3 ‒ force sensor, 4 ‒ support frame.

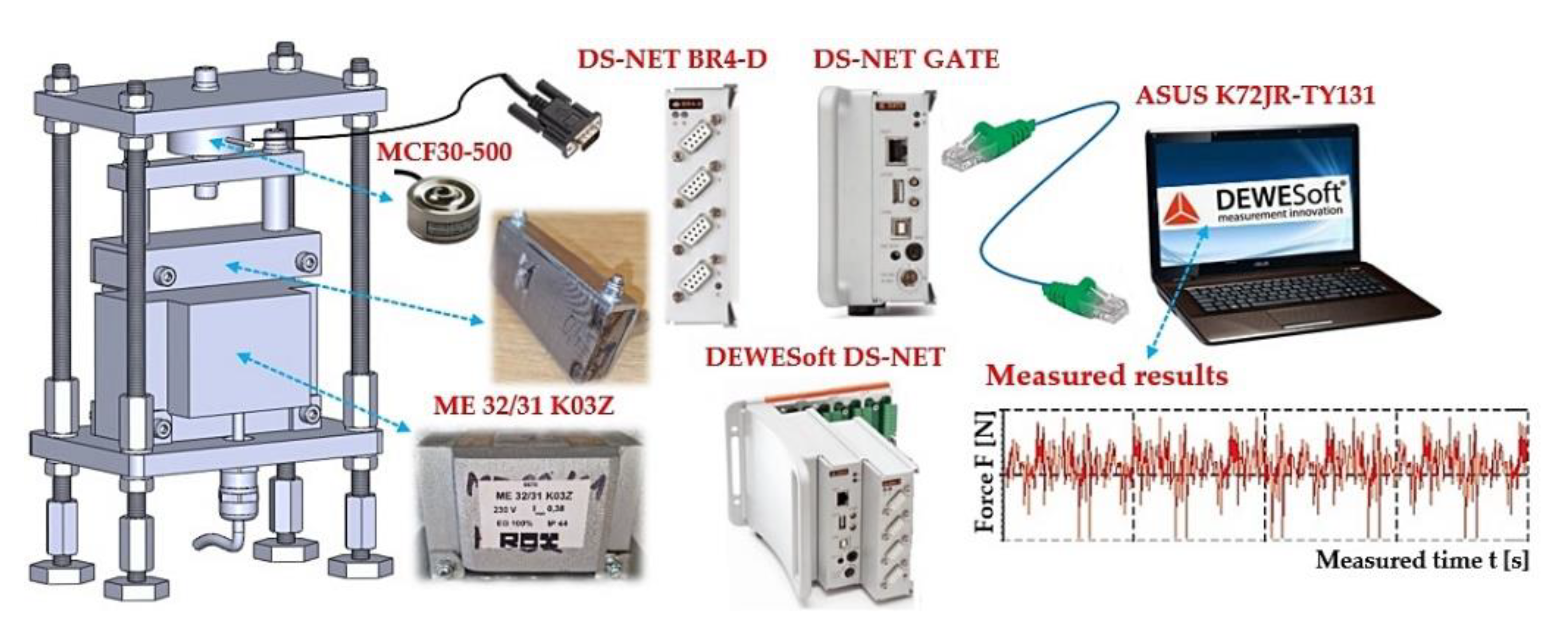

Figure 4.

Measuring chain ‒ a sequence of interconnected instruments and devices that enable the detection and processing of measured signals.

Figure 4.

Measuring chain ‒ a sequence of interconnected instruments and devices that enable the detection and processing of measured signals.

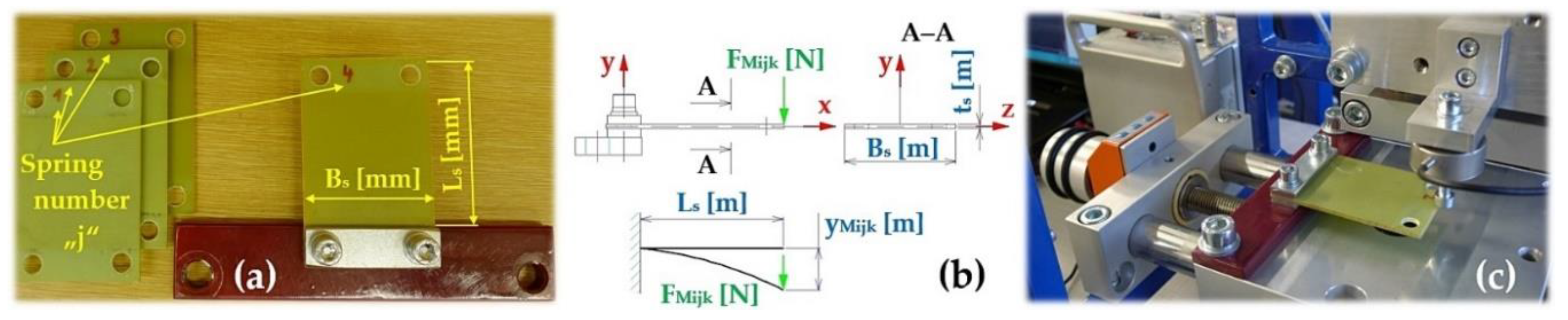

Figure 5.

(a) leaf springs made of FR4 Epoxy, (b) deflection yMijk [m] of a leaf spring of length Ls [m] loaded with force FMijk [N], (c) of measuring the deflection of the leaf spring on laboratory device.

Figure 5.

(a) leaf springs made of FR4 Epoxy, (b) deflection yMijk [m] of a leaf spring of length Ls [m] loaded with force FMijk [N], (c) of measuring the deflection of the leaf spring on laboratory device.

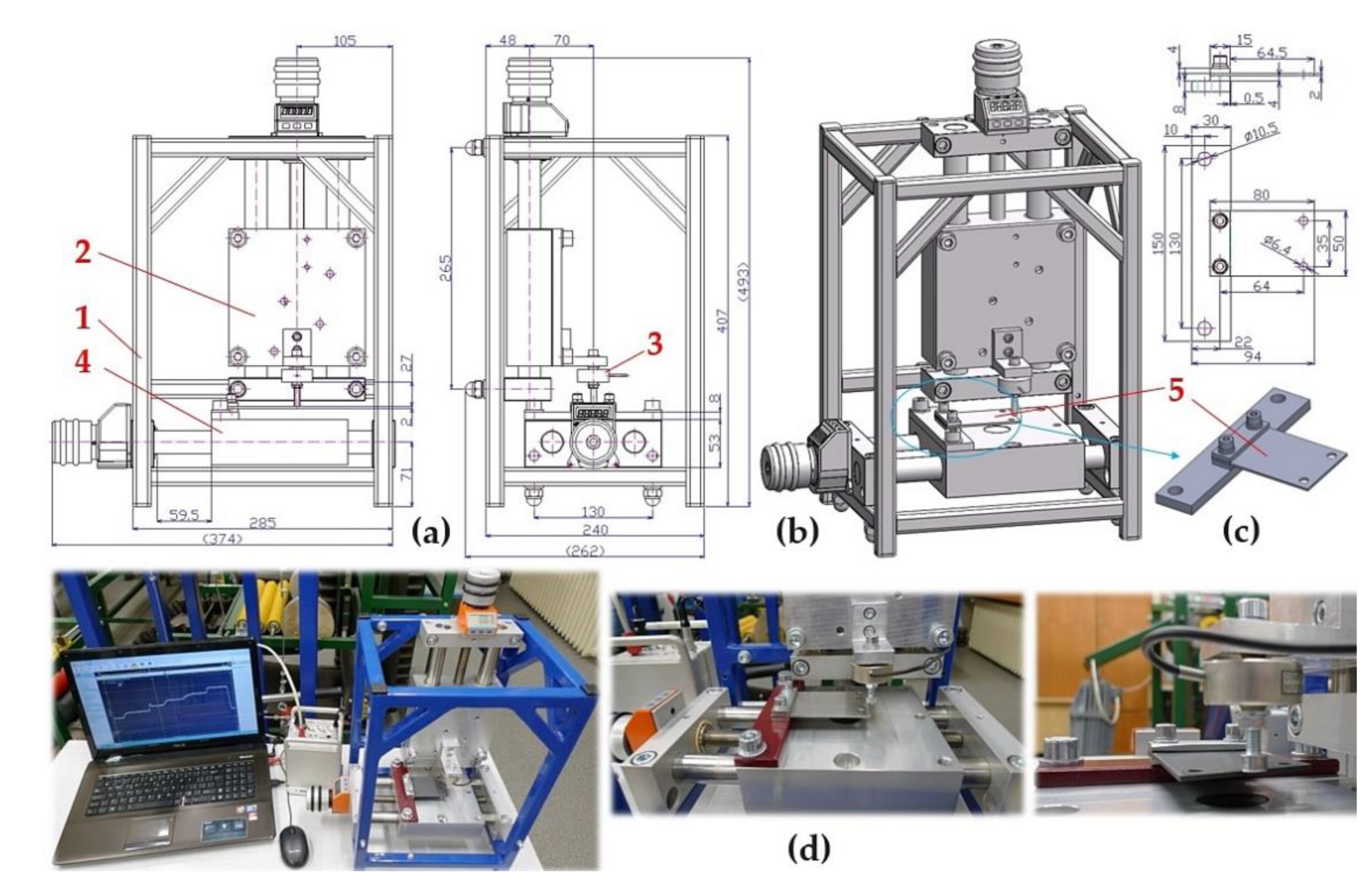

Figure 6.

Laboratory device for measuring the stiffness of leaf springs, (a) dimensional sketch, (b) 3D model, (c) attachment of the leaf spring to the flat bar by a bolted connection, (d) implemented device. 1 ‒ steel frame, 2, 4 ‒ positioning table PT7312-PA, 3 ‒ MCF30-500 force transducer, 5 ‒ leaf spring.

Figure 6.

Laboratory device for measuring the stiffness of leaf springs, (a) dimensional sketch, (b) 3D model, (c) attachment of the leaf spring to the flat bar by a bolted connection, (d) implemented device. 1 ‒ steel frame, 2, 4 ‒ positioning table PT7312-PA, 3 ‒ MCF30-500 force transducer, 5 ‒ leaf spring.

Figure 7.

The vibrating feeder with electromagnetic vibration exciter (a) dimensional sketch and 3D model, (b) implemented measuring device. 1 ‒ steel trough, 2 ‒ steel frame, 3 ‒ leaf spring, 4 ‒ electromagnet, 5 ‒ armature of the electromagnet, 6 ‒ amplitude/frequency regulator - FQ1 DIG.

Figure 7.

The vibrating feeder with electromagnetic vibration exciter (a) dimensional sketch and 3D model, (b) implemented measuring device. 1 ‒ steel trough, 2 ‒ steel frame, 3 ‒ leaf spring, 4 ‒ electromagnet, 5 ‒ armature of the electromagnet, 6 ‒ amplitude/frequency regulator - FQ1 DIG.

Figure 8.

The vibrating feeder with electromagnetic vibration exciter. 1 ‒ steel trough, 2 ‒ steel frame, 3 ‒ acceleration sensors, 4 ‒ amplitude/frequency controller, 5 ‒ measuring apparatus, 6 ‒ PC with DEWESoft X software.

Figure 8.

The vibrating feeder with electromagnetic vibration exciter. 1 ‒ steel trough, 2 ‒ steel frame, 3 ‒ acceleration sensors, 4 ‒ amplitude/frequency controller, 5 ‒ measuring apparatus, 6 ‒ PC with DEWESoft X software.

Figure 15.

Measured values of effective vibration velocities vc(l,i,1)10,0 [mm·s–1] in three mutually perpendicular planes of (a) trough supported by 4 FR4 Epoxy leaf springs, (b) steel frame of vibrating feeder.

Figure 15.

Measured values of effective vibration velocities vc(l,i,1)10,0 [mm·s–1] in three mutually perpendicular planes of (a) trough supported by 4 FR4 Epoxy leaf springs, (b) steel frame of vibrating feeder.

Figure 16.

Measured values of the effective vibration velocity vc(x,i,1)20,2.57 [mm·s–1] in the direction of the x-axis of the trough (supported by 4 FR4 Epoxy leaf springs) and the steel frame of the vibrating feeder.

Figure 16.

Measured values of the effective vibration velocity vc(x,i,1)20,2.57 [mm·s–1] in the direction of the x-axis of the trough (supported by 4 FR4 Epoxy leaf springs) and the steel frame of the vibrating feeder.

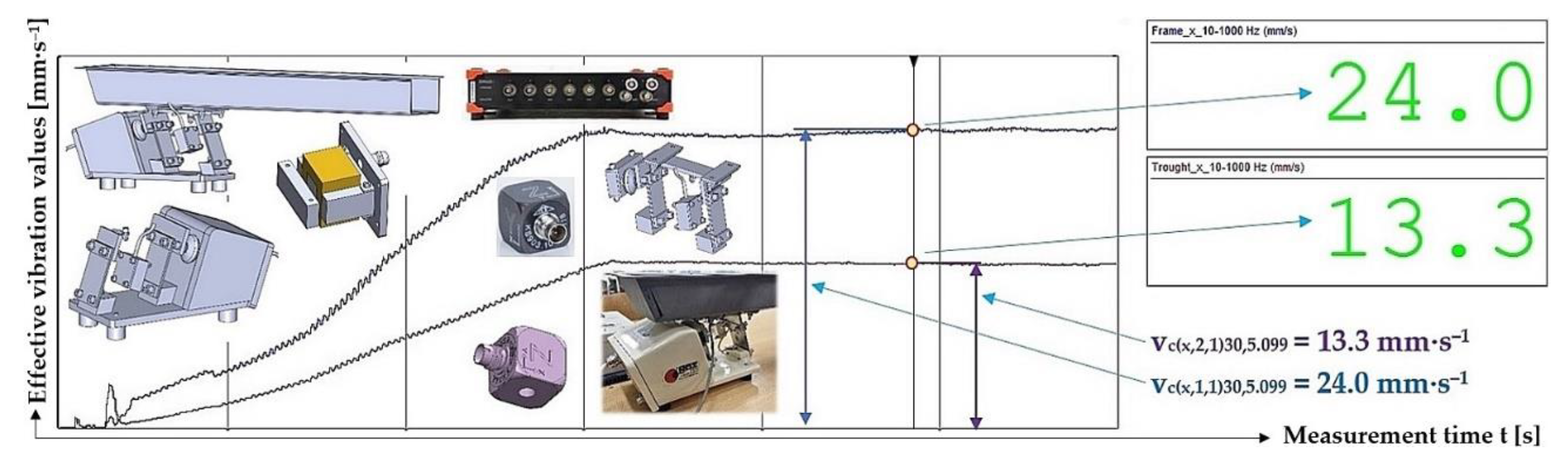

Figure 17.

Measured values of the effective vibration velocity vc(x,i,1)30,5.099 [mm·s‒1] in the direction of the x-axis of the trough (supported by 4 FR4 Epoxy leaf springs) and the steel frame of the vibrating feeder.

Figure 17.

Measured values of the effective vibration velocity vc(x,i,1)30,5.099 [mm·s‒1] in the direction of the x-axis of the trough (supported by 4 FR4 Epoxy leaf springs) and the steel frame of the vibrating feeder.

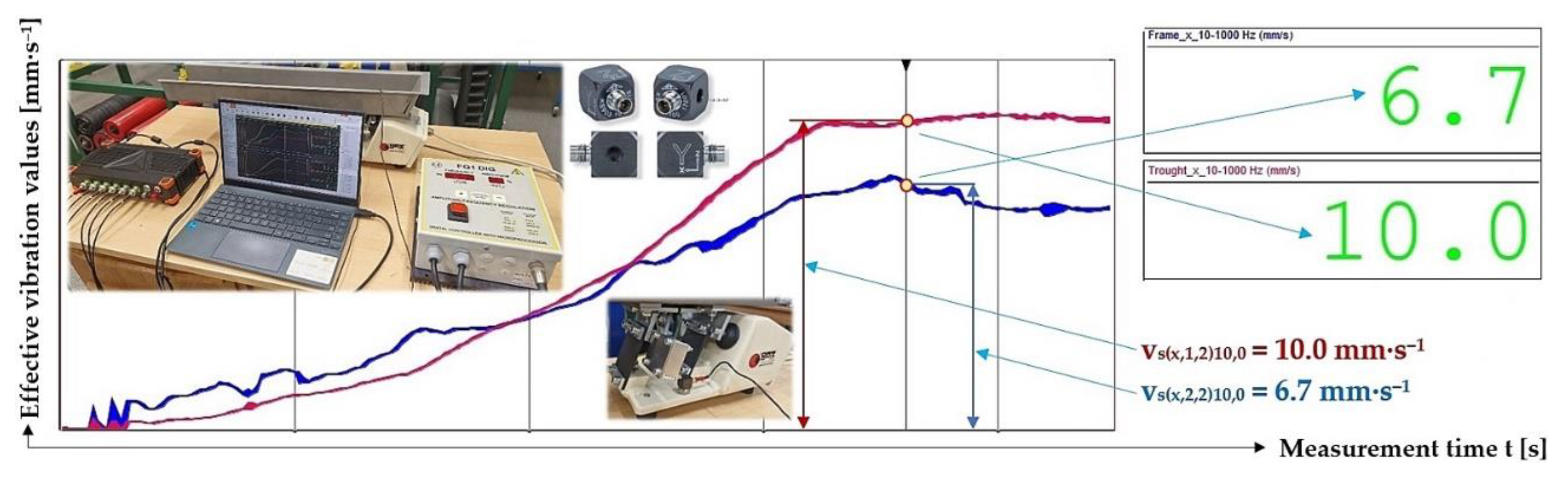

Figure 18.

Measured values of the effective vibration velocity vs(x,i,2)10,0 [mm·s‒1] in the direction of the x-axis of the trough (supported by 2 Steel leaf springs) and the steel frame of the vibrating feeder.

Figure 18.

Measured values of the effective vibration velocity vs(x,i,2)10,0 [mm·s‒1] in the direction of the x-axis of the trough (supported by 2 Steel leaf springs) and the steel frame of the vibrating feeder.

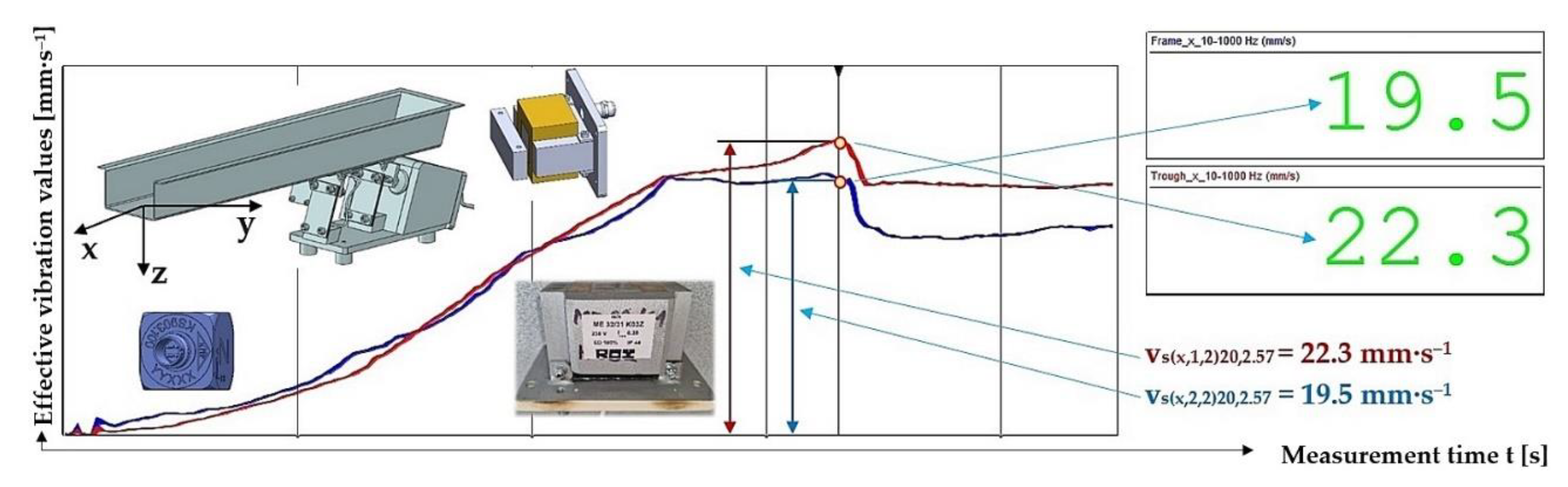

Figure 19.

Measured values of the effective vibration velocity vs(x,i,2)20,2.57 [mm·s‒1] in the direction of the x-axis of the trough (supported by 2 Steel leaf springs) and the steel frame of the vibrating feeder.

Figure 19.

Measured values of the effective vibration velocity vs(x,i,2)20,2.57 [mm·s‒1] in the direction of the x-axis of the trough (supported by 2 Steel leaf springs) and the steel frame of the vibrating feeder.

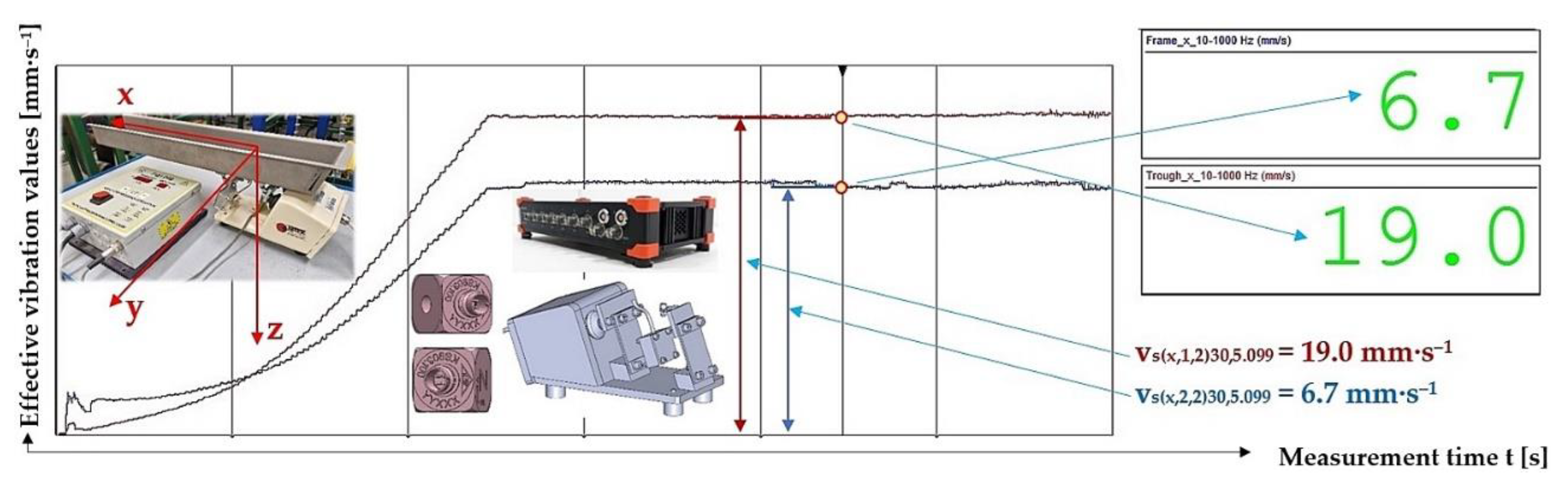

Figure 20.

Measured values of the effective vibration velocity vs(x,i,2)30,5.099 [mm·s‒1] in the direction of the x-axis of the trough (supported by 2 Steel leaf springs) and the steel frame of the vibrating feeder.

Figure 20.

Measured values of the effective vibration velocity vs(x,i,2)30,5.099 [mm·s‒1] in the direction of the x-axis of the trough (supported by 2 Steel leaf springs) and the steel frame of the vibrating feeder.

Figure 21.

Measured values of the effective vibration velocities vc(x,i,j)k,m [mm·s‒1] of the oscillation of the steel frame (continuous curve) and trough (dashed curve) of the vibrating feeder with various values of k [%] and the selected material of the leaf springs FR4 Epoxy.

Figure 21.

Measured values of the effective vibration velocities vc(x,i,j)k,m [mm·s‒1] of the oscillation of the steel frame (continuous curve) and trough (dashed curve) of the vibrating feeder with various values of k [%] and the selected material of the leaf springs FR4 Epoxy.

Figure 22.

Measured values of the effective vibration velocities vs(x,i,j)k,m [mm·s‒1] of the oscillation of the steel frame (continuous curve) and trough (dashed curve) of the vibrating feeder with various values of k [%] and the selected material of the leaf springs Steel.

Figure 22.

Measured values of the effective vibration velocities vs(x,i,j)k,m [mm·s‒1] of the oscillation of the steel frame (continuous curve) and trough (dashed curve) of the vibrating feeder with various values of k [%] and the selected material of the leaf springs Steel.

Figure 23.

Measured values of the effective vibration velocities vp(x,i,j)k,m [mm·s‒1] of the oscillation of the steel frame (continuous curve) and trough (dashed curve) of the vibrating feeder with various values of k [%] and the selected material of the leaf springs Plastic PCCF.

Figure 23.

Measured values of the effective vibration velocities vp(x,i,j)k,m [mm·s‒1] of the oscillation of the steel frame (continuous curve) and trough (dashed curve) of the vibrating feeder with various values of k [%] and the selected material of the leaf springs Plastic PCCF.

Table 9.

Effective vibration velocities vc(x,i,j)k,0 [mm·s–1] of the steel frame (i = 1) and trough (i = 2) measured in the "x" axis (l = x) of the coordinate system. Load weight m = 0 kg, leaf spring material FR4 Epoxy (∗ = c).

Table 9.

Effective vibration velocities vc(x,i,j)k,0 [mm·s–1] of the steel frame (i = 1) and trough (i = 2) measured in the "x" axis (l = x) of the coordinate system. Load weight m = 0 kg, leaf spring material FR4 Epoxy (∗ = c).

Table 10.

Effective vibration velocities vc(x,i,j)k,2.57 [mm·s–1] of the steel frame (i = 1) and trough (i = 2) measured in the "x" axis of the coordinate system. Load weight m = 2.57 kg, leaf spring material FR4 Epoxy (∗ = c).

Table 10.

Effective vibration velocities vc(x,i,j)k,2.57 [mm·s–1] of the steel frame (i = 1) and trough (i = 2) measured in the "x" axis of the coordinate system. Load weight m = 2.57 kg, leaf spring material FR4 Epoxy (∗ = c).

Table 11.

Effective vibration velocities vc(x,i,j)k,5.099 [mm·s‒1] of the steel frame (i = 1) and trough (i = 2) measured in the "x" axis of the coordinate system. Load weight m = 5.099 kg, leaf spring material FR4 Epoxy (∗ = c).

Table 11.

Effective vibration velocities vc(x,i,j)k,5.099 [mm·s‒1] of the steel frame (i = 1) and trough (i = 2) measured in the "x" axis of the coordinate system. Load weight m = 5.099 kg, leaf spring material FR4 Epoxy (∗ = c).

Table 12.

Effective vibration velocities vs(x,i,j)k,0 [mm·s‒1] of the steel frame (i = 1) and trough (i = 2) measured in the "x" axis (l = x) of the coordinate system. Load weight m = 0 kg, leaf spring material Steel (∗ = s).

Table 12.

Effective vibration velocities vs(x,i,j)k,0 [mm·s‒1] of the steel frame (i = 1) and trough (i = 2) measured in the "x" axis (l = x) of the coordinate system. Load weight m = 0 kg, leaf spring material Steel (∗ = s).

Table 13.

Effective vibration velocities vs(x,i,j)k,2.57 [mm·s‒1] of the steel frame (i = 1) and trough (i = 2) measured in the "x" axis (l = x) of the coordinate system. Load weight m = 2.57 kg, leaf spring material Steel (∗ = s).

Table 13.

Effective vibration velocities vs(x,i,j)k,2.57 [mm·s‒1] of the steel frame (i = 1) and trough (i = 2) measured in the "x" axis (l = x) of the coordinate system. Load weight m = 2.57 kg, leaf spring material Steel (∗ = s).

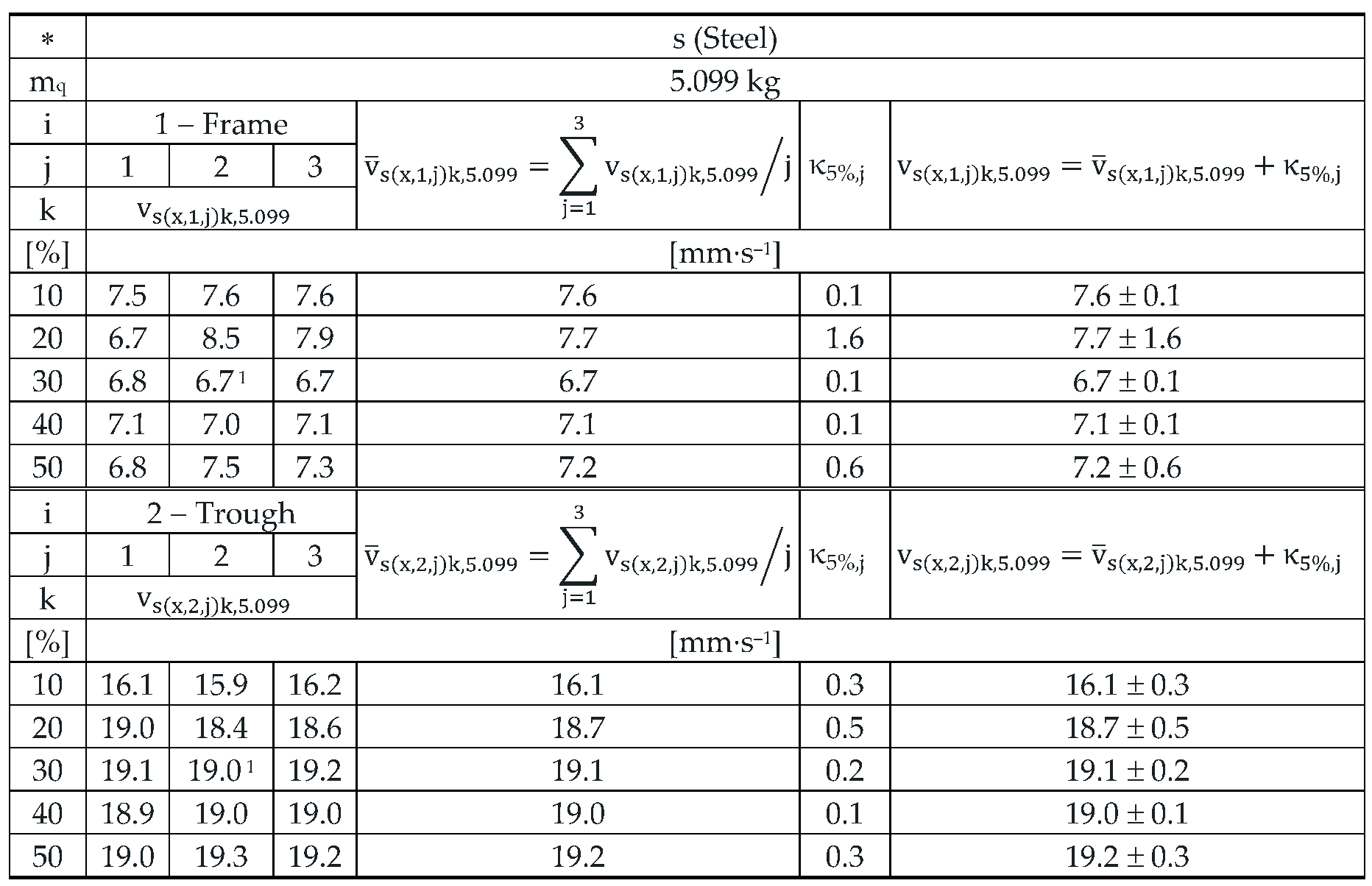

Table 14.

Effective vibration velocities vs(x,i,j)k,5.099 [mm·s‒1] of the steel frame (i = 1) and trough (i = 2) measured in the "x" axis (l = x) of the coordinate system. Load weight m = 5.099 kg, leaf spring material Steel (∗ = s).

Table 14.

Effective vibration velocities vs(x,i,j)k,5.099 [mm·s‒1] of the steel frame (i = 1) and trough (i = 2) measured in the "x" axis (l = x) of the coordinate system. Load weight m = 5.099 kg, leaf spring material Steel (∗ = s).

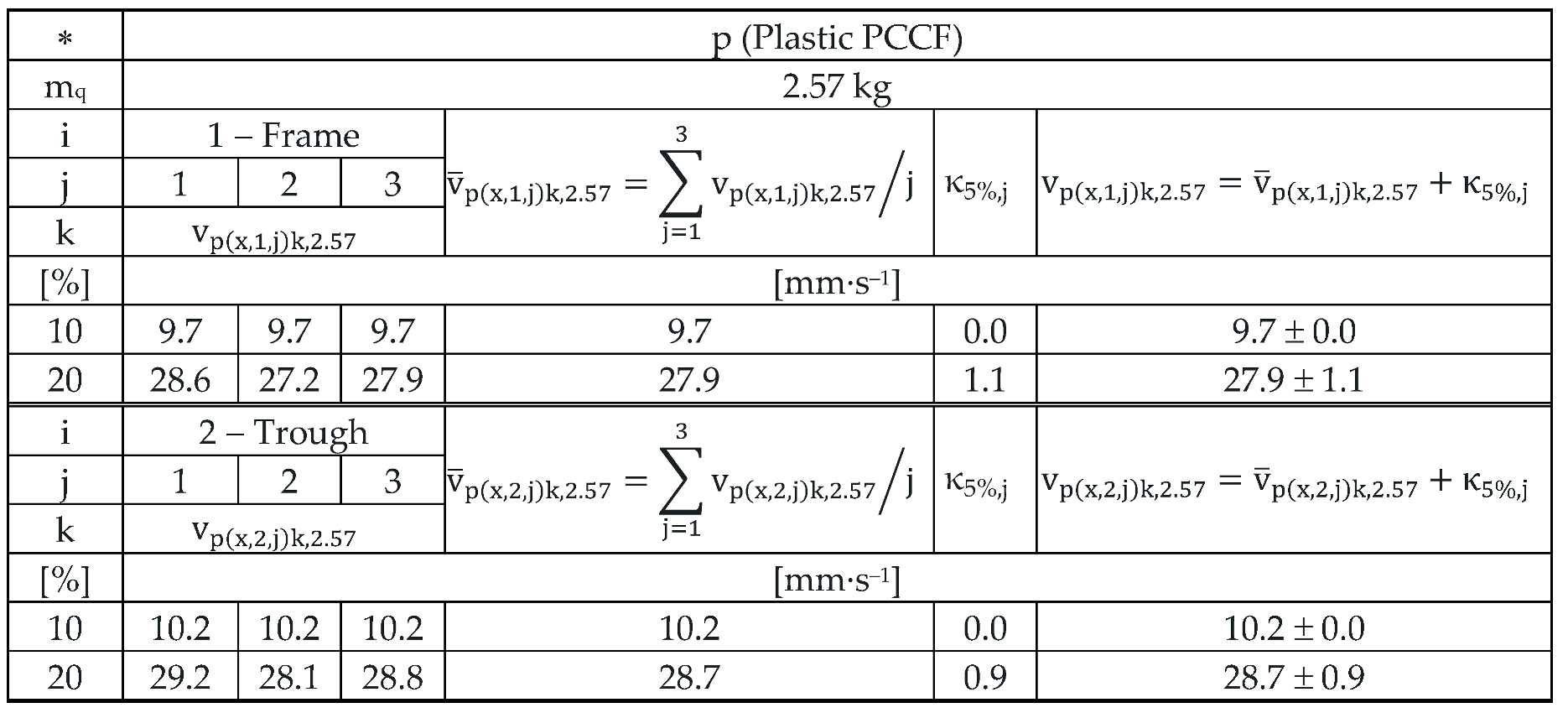

Table 16.

Effective vibration velocities vp(x,i,j)k,2.57 [mm·s‒1] of the steel frame (i = 1) and trough (i = 2) measured in the "x" axis (l = x) of the coordinate system. Load weight m = 2.57 kg, leaf spring material Plastic (∗ = p).

Table 16.

Effective vibration velocities vp(x,i,j)k,2.57 [mm·s‒1] of the steel frame (i = 1) and trough (i = 2) measured in the "x" axis (l = x) of the coordinate system. Load weight m = 2.57 kg, leaf spring material Plastic (∗ = p).

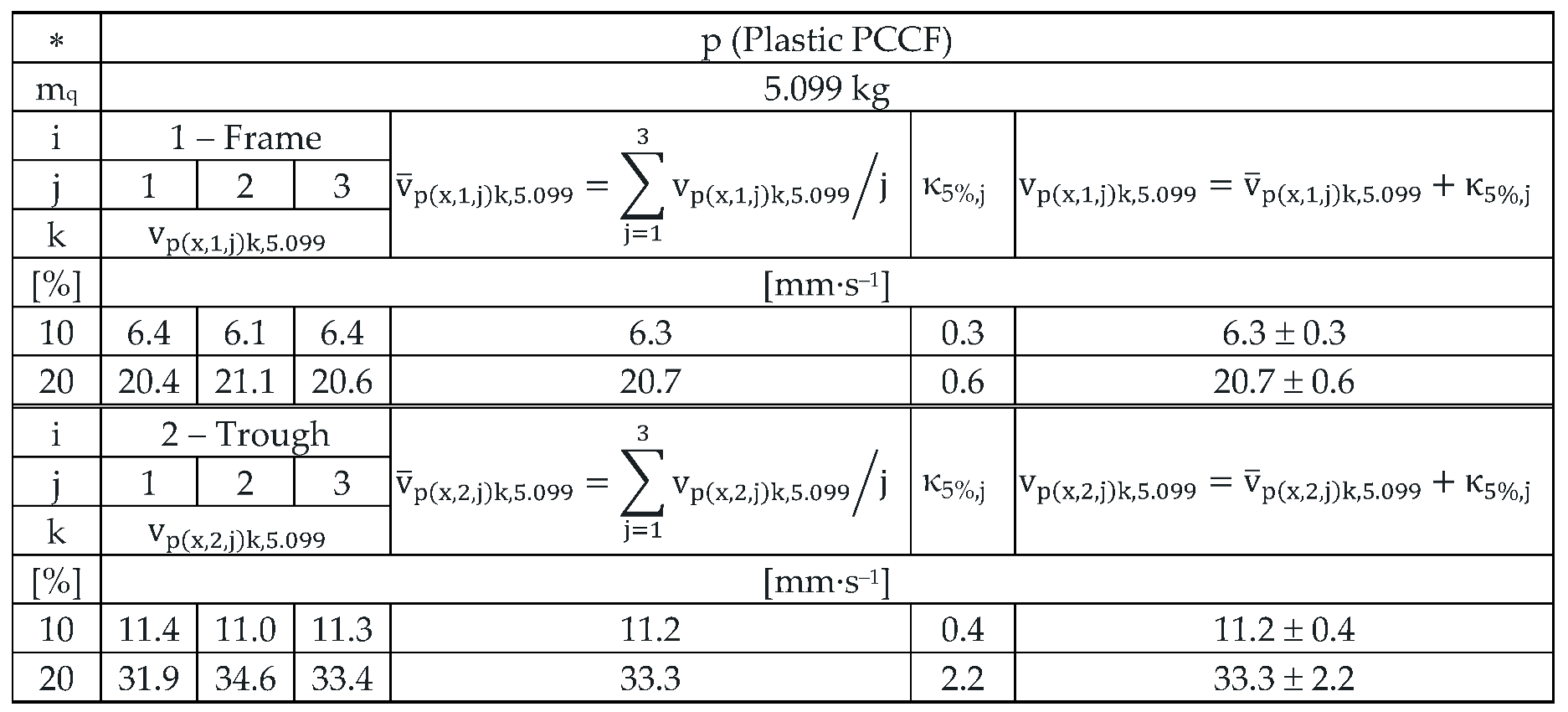

Table 17.

Effective vibration velocities vp(x,i,j)k,5.099 [mm·s‒1] of the steel frame (i = 1) and trough (i = 2) measured in the "x" axis (l = x) of the coordinate system. Load weight m = 5.099 kg, leaf spring material Plastic (∗ = p).

Table 17.

Effective vibration velocities vp(x,i,j)k,5.099 [mm·s‒1] of the steel frame (i = 1) and trough (i = 2) measured in the "x" axis (l = x) of the coordinate system. Load weight m = 5.099 kg, leaf spring material Plastic (∗ = p).