Submitted:

08 July 2025

Posted:

10 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Multicomponent Program

| Warm up | ||

| Exercise | Repetition | |

Shoulder and hip flexion posture with spinal extension and posterior chain activation.

|

5 repetitions | |

Knee and hip flexion and extension.

|

5 repetitions | |

Hip and knee flexion and extension in a plank position.

|

5 repetitions | |

Dynamic mobility stretching for hips and shoulders (Lunge with Arm Raise).

|

5 repetitions per leg | |

Bird Dog

|

5 repetitions per arm | |

Lumbar flexion.

|

5 repetitions | |

Cat-Cow Stretch

|

5 repetitions | |

Twisting Lunge or Reverse Lunge Pose.

|

5 repetitions per side | |

Lateral trunk stretch with floor support (Gate Pose).

|

5 repetitions per side | |

Hip abduction.

|

5 repetitions per leg | |

| Main part | ||

| Weeks | Muscle/Exercise | Sets/repetition |

| 1 – 4 |

|

3x15 |

| 5 – 8 | 3x12 | |

| 9 – 12 | 3x10 | |

| Return to calm | ||

| Main muscle groups | Execution | Duration |

| Hamstring Stretch | Lie on your back and extend one leg upward, holding it behind the thigh or calf. Keep the other leg bent or flat on the floor | 20 to 30 seconds |

| Quadriceps Stretch | Stand up, grasp one ankle with the corresponding hand, pulling it toward your buttocks. Keep your knees aligned and your torso upright. | 20 to 30 seconds |

| Gluteal Stretch | Lie on your back, cross one leg over the other, placing the ankle on the opposite knee. Pull the lower leg toward your chest. | 20 to 30 seconds |

| Chest Stretch | Stand with your arms extended behind you, interlocking your fingers. Gently lift your arms upward, opening your chest | 20 to 30 seconds |

| Back Stretch | Sit or stand, interlock your fingers and extend your arms forward, rounding your back and pushing your hands away from your body. | 20 to 30 seconds |

| Neck Stretch | Tilt your head to one side, bringing your ear toward your shoulder, and gently press with the opposite hand | 20 to 30 seconds |

| Module | Contents | Objectives | Duration |

| 1 Social Skills Training and Emotional Regulation Mental Health Education and Cognitive Strategies Solution Focused Therapy and Emotional Expression |

Discussion groups Psychoeducation Teachers' suggestion box |

Promote cognitive restructuring, awareness and encourage cognitive restructuring and autonomy |

1 hour |

| 2 Problem Solving and SMART Goal Setting Guided Imagery and Cognitive Rehearsal |

Problem identification and goal setting Vision of the future |

Reduce feelings of helplessness and increase the perception of control over professional reality |

1 hour |

| 3 Cognitive Restructuring and Positive Self-Image Beck's Cognitive Triad Model |

Mirror dynamics Cognitive triad, thought assessment, refocusing Mirror dynamics |

Reduce discomfort regarding self-image and professional perception. |

1 hour |

| Note: SMART - Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant and Timely. | |||

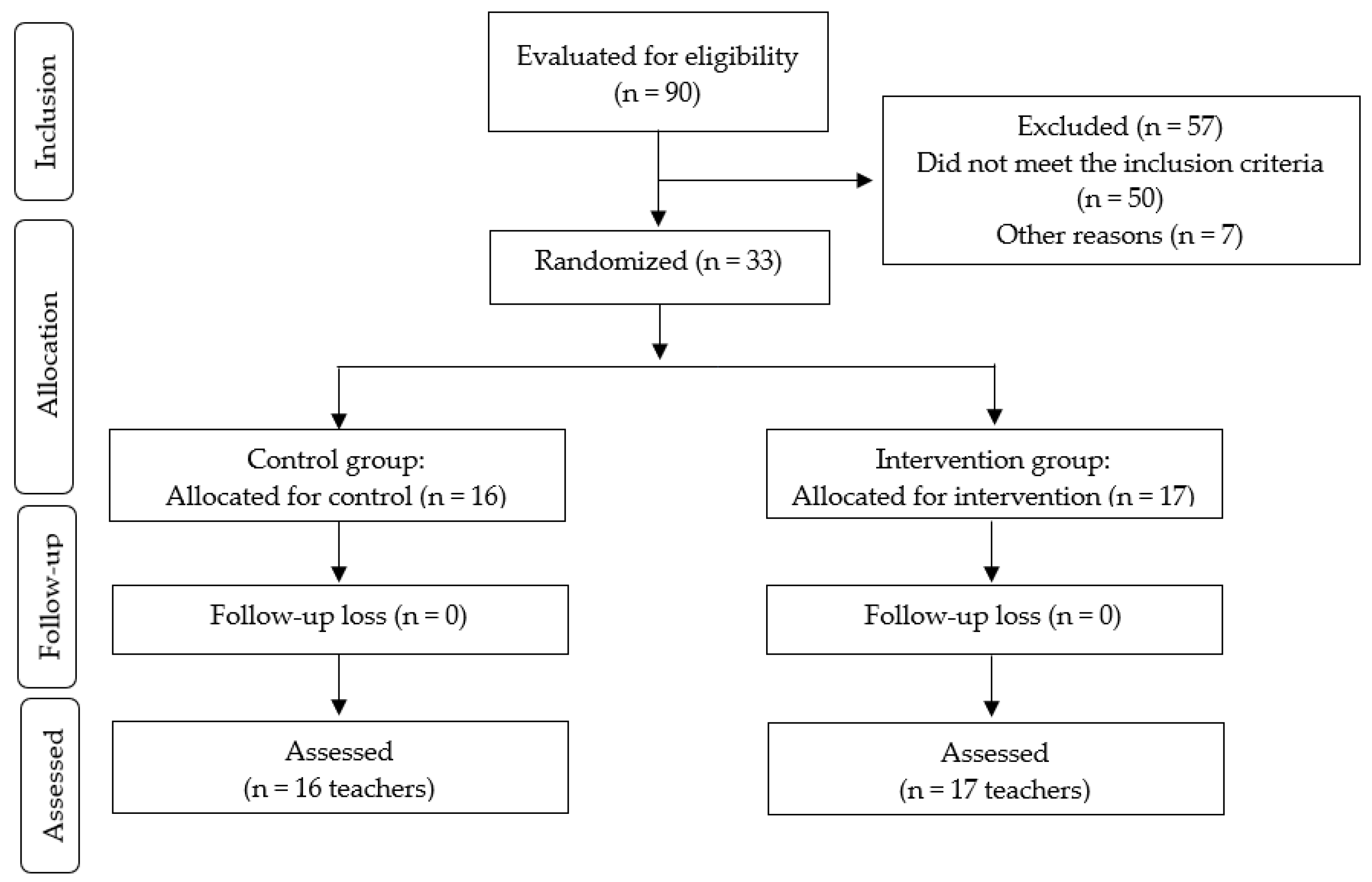

2.4. Study Design

2.5. Biochemical Assessment

2.6. Mental Disorders Assessments

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Participants Description

| Variables | Control (n = 16) | Intervention (n = 17) | |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | p-Value | |

| Age (years) | 43.1 ± 6.5 | 43.8 ± 7.7 | 0.763 |

| Body weight (kg) | 83.2 ± 9.1 | 80.9 ± 8.7 | 0.470 |

| Height (m) | 1.62 ± 0.0 | 1.61 ± 0.0 | 0.776 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.8 ± 3.9 | 31.0 ± 3.2 | 0.577 |

3.2. Mental Disorders

| Symptoms | Control (n = 16) | Intervention (n = 17) | |||

| Baseline | After 12 weeks | Baseline | After 12 weeks | ||

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||

| Depression (Score) | 3.2 ± 3.2 | 2.4 ± 3.2 | 5.6 ± 5.8 | 2.1 ± 2.9* | |

| Anxiety (Score) | 3.1 ± 2.7 | 3.8 ± 4.2 | 6.5 ± 5.1 | 2.7 ± 3.2** | |

| Stress (Score) | 5.2 ± 2.1 | 5.4 ± 4.9 | 8.7 ± 6.3 | 4.2 ± 4.4* | |

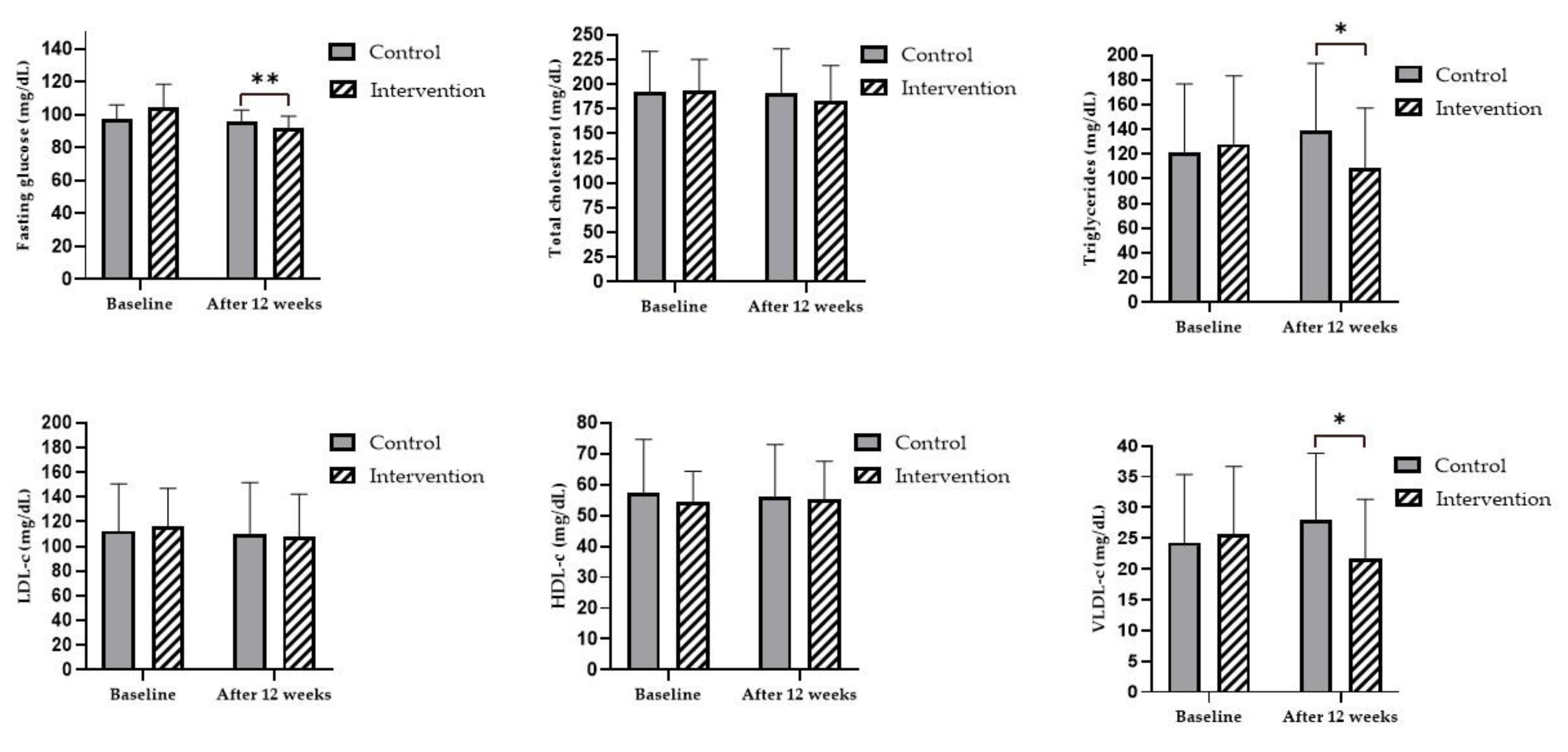

3.2. Biochemical Parameters

3.3. Immunological Parameters

| Immunoglobulins | Control (n = 16) | Intervention (n = 17) | ||||

| Baseline | After 12 weeks | Baseline | After 12 weeks | |||

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||

| IgA (mg/dL) | 225.3 ± 73.9 | 224.4 ± 73.9 | 232.6 ± 87.3 | 227.1 ± 75.9 | ||

| IgG (mg/dL) | 1.152 ± 185.8 | 1.158 ± 205.7 | 1.138 ± 271.2 | 1.180 ± 287.5 | ||

| IgM (mg/dL) | 102.1 ± 41.9 | 100.2 ± 32.7 | 100.0 ± 48.6 | 99.4 ± 49.0 | ||

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agyapong B, Obuobi-Donkor G, Burback L, Wei Y. Stress, Burnout, Anxiety and Depression among Teachers: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(17):10706.

- Morais ÉAHd, Abreu MNS, Assunção AÁ. Autoavaliação de saúde e fatores relacionados ao trabalho dos professores da educação básica no Brasil. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2023;28(1):209-22. [CrossRef]

- Haikal DSA, Prates TEC, Vieira MRM, Magalhães TAd, Baldo MP, Batista de Paula AM, Ferreira EFe. Fatores de risco e proteção para doenças crônicas não transmissíveis entre professores da educação básica. Revista Brasileira de Saúde Ocupacional. 2023;48.

- Vancheri F, Longo G, Vancheri E, Henein MY. Mental Stress and Cardiovascular Health-Part I. J Clin Med. 2022;11(12). [CrossRef]

- Henein MY, Vancheri S, Longo G, Vancheri F. The Impact of Mental Stress on Cardiovascular Health—Part II. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2022;11(15):4405.

- Rocha RERd, Ujiie NT, Blaszko CE. Qualidade de vida de professores da Educação Básica: dialogia com a complexidade e a ecoformação. Revista Diálogo Educacional. 2023;23(78). [CrossRef]

- Fernandes FT, Chiavegatto Filho ADP. Prediction of absenteeism in public schools teachers with machine learning. Rev Saude Publica. 2021;55:23. [CrossRef]

- Tavares P, Honda L. Absenteísmo docente em escolas públicas paulistas: dimensão e fatores associados. Estudos Econômicos (São Paulo). 2021;51(3):601-35. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Loureiro L, Artazcoz L, Lopez-Ruiz M, Assuncao AA, Benavides FG. Joint effect of paid working hours and multiple job holding on work absence due to health problems among basic education teachers in Brazil: the Educatel Study. Cad Saude Publica. 2019;35 Suppl 1:e00081118. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Wang X, Chen J, Lee JC-K, Yan Z, Li J-B. The Intervention Effects on Teacher Well-being: A Three-Level Meta-Analysis. Educational Psychology Review. 2024;36(4):129. [CrossRef]

- Parker EA, McArdle PF, Gioia D, Trilling A, Bahr-Robertson M, Costa N, et al. An Onsite Fitness Facility and Integrative Wellness Program Positively Impacted Health-Related Outcomes Among Teachers and Staff at an Urban Elementary/Middle School. Glob Adv Health Med. 2019;8:2164956119873276. [CrossRef]

- Keating XD, Shangguan R, Xiao K, Gao X, Sheehan C, Wang L, et al. Tracking Changes of Chinese Pre-Service Teachers' Aerobic Fitness, Body Mass Index, and Grade Point Average Over 4-years of College. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(6). [CrossRef]

- Dias J, Dusmann Junior M, Costa MAR, Francisqueti V, Higarashi IH. Physical activities practicing among scholar professors: focus on their quality of life. Escola Anna Nery. 2017;21(4). [CrossRef]

- Agyapong B, Chishimba C, Wei Y, da Luz Dias R, Eboreime E, Msidi E, et al. Improving Mental Health Literacy and Reducing Psychological Problems Among Teachers in Zambia: Protocol for Implementation and Evaluation of a Wellness4Teachers Email Messaging Program. JMIR Res Protoc. 2023;12:e44370. [CrossRef]

- Beames JR, Spanos S, Roberts A, McGillivray L, Li S, Newby JM, et al. Intervention Programs Targeting the Mental Health, Professional Burnout, and/or Wellbeing of School Teachers: Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses. Educational Psychology Review. 2023;35(1):26. [CrossRef]

- Melo SPdSdC, Cesse EÂP, Lira PICd, Ferreira LCCdN, Rissin A, Batista Filho M. Sobrepeso, obesidade e fatores associados aos adultos em uma área urbana carente do Nordeste Brasileiro. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia. 2020;23.

- Karolkiewicz J, Krzywicka M, Szulińska M, Musialik K, Musiałowska D, Zieliński J, et al. Effects of a Circuit Training Program on Myokine Levels in Insulin-Resistant Women: A Randomised Controlled Trial. J Diabetes Res. 2024;2024:6624919. [CrossRef]

- Day ML, McGuigan MR, Brice G, Foster C. Monitoring exercise intensity during resistance training using the session RPE scale. J Strength Cond Res. 2004;18(2):353-8. [CrossRef]

- Fava DC, Andretta I, Marin AH. Teaching Effectiveness and Children Emotional/Behavioral Difficulties: Outcomes from FAVA Program. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa. 2022;38.

- Vignola RC, Tucci AM. Adaptation and validation of the depression, anxiety and stress scale (DASS) to Brazilian Portuguese. J Affect Disord. 2014;155:104-9. [CrossRef]

- Kovess-Masféty V, Rios-Seidel C, Sevilla-Dedieu C. Teachers' mental health and teaching levels. Teaching and Teacher Education. 2007;23(7):1177-92. [CrossRef]

- Ouellette RR, Frazier SL, Shernoff ES, Cappella E, Mehta TG, Maríñez-Lora A, et al. Teacher Job Stress and Satisfaction in Urban Schools: Disentangling Individual-, Classroom-, and Organizational-Level Influences. Behav Ther. 2018;49(4):494-508. [CrossRef]

- Fathi J, Greenier V, Derakhshan A. Self-efficacy, Reflection, and Burnout among Iranian EFL Teachers: The Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research. 2021;9(2):13-37. [CrossRef]

- Chu B, Marwaha K, Sanvictores T, Awosika AO, Ayers D. Physiology, Stress Reaction. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC.; 2025.

- Sandeep Sekhon RM. Depressivo Distúrbios Cognitivos. In: Brianna Chu KM, Terrence Sanvictores, Ayoola O. Awosika, Derek Ayers, editor. Physiology, Stress Reaction. StatPearls [Internet]: Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing;; 2024.

- Demmin DL, Silverstein SM, Shors TJ. Mental and physical training with meditation and aerobic exercise improved mental health and well-being in teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Hum Neurosci. 2022;16:847301. [CrossRef]

- Wan Mohd Yunus WMA, Musiat P, Brown JSL. Systematic review of universal and targeted workplace interventions for depression. 2018;75:66-75.

- Joyce S, Modini M, Christensen H, Mykletun A, Bryant R, Mitchell PB, Harvey SB. Workplace interventions for common mental disorders: a systematic meta-review. 2016;46:683-97.

- Ashdown-Franks G, Firth J, Carney R, Carvalho AF, Hallgren M, Koyanagi A, et al. Exercise as Medicine for Mental and Substance Use Disorders: A Meta-review of the Benefits for Neuropsychiatric and Cognitive Outcomes. Sports Med. 2020;50(1):151-70. [CrossRef]

- Solmi M, Basadonne I, Bodini L, Rosenbaum S, Schuch FB, Smith L, et al. Exercise as a transdiagnostic intervention for improving mental health: An umbrella review. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2025;184:91-101. [CrossRef]

- Gautam M, Tripathi A, Deshmukh D, Gaur M. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62(Suppl 2):S223-s9. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, Qian L, Shen JT, Wang B, Shen XH, Shi GP. Short-term structured dietary and exercise interventions delay diabetes onset in prediabetic patients: a prospective quasi-experimental study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2025;16:1413206. [CrossRef]

- Paoli A. The Influence of Physical Exercise, Ketogenic Diet, and Time-Restricted Eating on De Novo Lipogenesis: A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2025;17(4):663.

- Hei Y, Xie Y. Effects of exercise combined with different dietary interventions on cardiovascular health a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2025;25(1):222. [CrossRef]

- Chan BS, Yu DSF, Wong CWY, Li PWC. Multi-modal interventions outperform nutritional or exercise interventions alone in reversing metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Braggio M, Dorelli G, Olivato N, Lamberti V, Valenti MT, Dalle Carbonare L, Cominacini M. Tailored Exercise Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome: Cardiometabolic Improvements Beyond Weight Loss and Diet—A Prospective Observational Study. Nutrients. 2025;17(5):872.

- Liu D, Zhang Y, Wu Q, Han R, Cheng D, Wu L, et al. Exercise-induced improvement of glycemic fluctuation and its relationship with fat and muscle distribution in type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes. 2024;16(4):e13549. [CrossRef]

- Hejazi K, Wong A. Effects of exercise training on inflammatory and cardiometabolic health markers in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2023;63(2):345-59. [CrossRef]

- Batrakoulis A, Jamurtas AZ, Metsios GS, Perivoliotis K, Liguori G, Feito Y, et al. Comparative Efficacy of 5 Exercise Types on Cardiometabolic Health in Overweight and Obese Adults: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of 81 Randomized Controlled Trials. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2022;15(6):e008243. [CrossRef]

- Hao S, Tan S, Li J, Li W, Li J, Cai X, Hong Z. Dietary and exercise interventions for metabolic health in perimenopausal women in Beijing. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2021;30(4):624-31. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz R, Kluwe B, Lazarus S, Teruel MN, Joseph JJ. Cortisol and cardiometabolic disease: a target for advancing health equity. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2022;33(11):786-97. [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti A, Ellermeier N, Tripathi A, Thirumurthy H, Nugent R. Diet-focused behavioral interventions to reduce the risk of non-communicable diseases in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review of existing evidence. Obes Rev. 2025:e13918. [CrossRef]

- Bahr R, Hansson P, Sejersted OM. Triglyceride/fatty acid cycling is increased after exercise. Metabolism. 1990;39(9):993-9. [CrossRef]

- Børsheim E, Bahr R. Effect of exercise intensity, duration and mode on post-exercise oxygen consumption. Sports Med. 2003;33(14):1037-60. [CrossRef]

- Walzik D, Belen S, Wilisch K, Kupjetz M, Kirschke S, Esser T, et al. Impact of exercise on markers of B cell-related immunity: A systematic review. J Sport Health Sci. 2024;13(3):339-52. [CrossRef]

- Šimunić-Briški N, Zekić R, Dukarić V, Očić M, Frkatović-Hodžić A, Deriš H, et al. Physical Exercise Induces Significant Changes in Immunoglobulin G N-Glycan Composition in a Previously Inactive, Overweight Population. Biomolecules. 2023;13(5). [CrossRef]

- Drummond LR, Campos HO, Drummond FR, de Oliveira GM, Fernandes J, Amorim RP, et al. Acute and chronic effects of physical exercise on IgA and IgG levels and susceptibility to upper respiratory tract infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pflugers Arch. 2022;474(12):1221-48. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).