Submitted:

09 July 2025

Posted:

10 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Phytochemical Research

2.2. Pharmacological Research

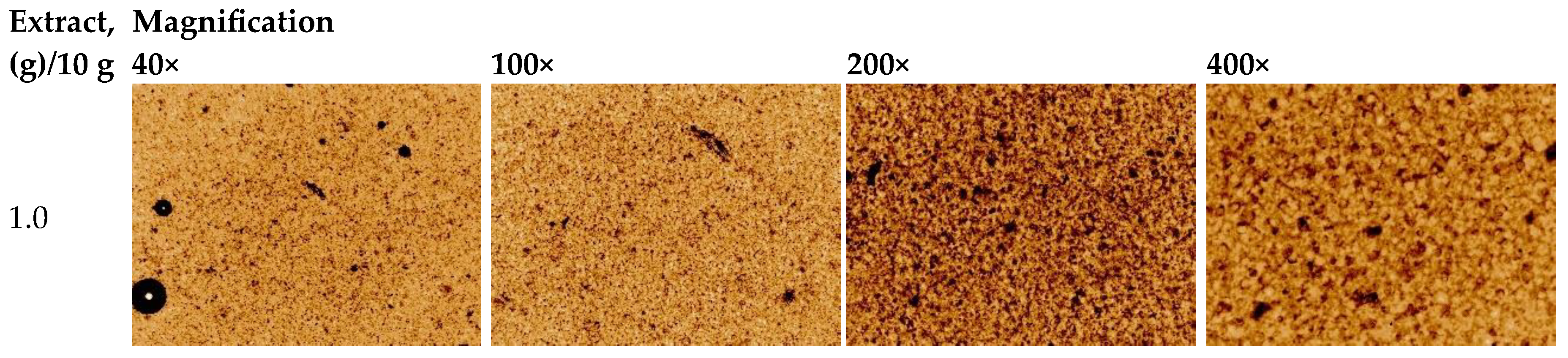

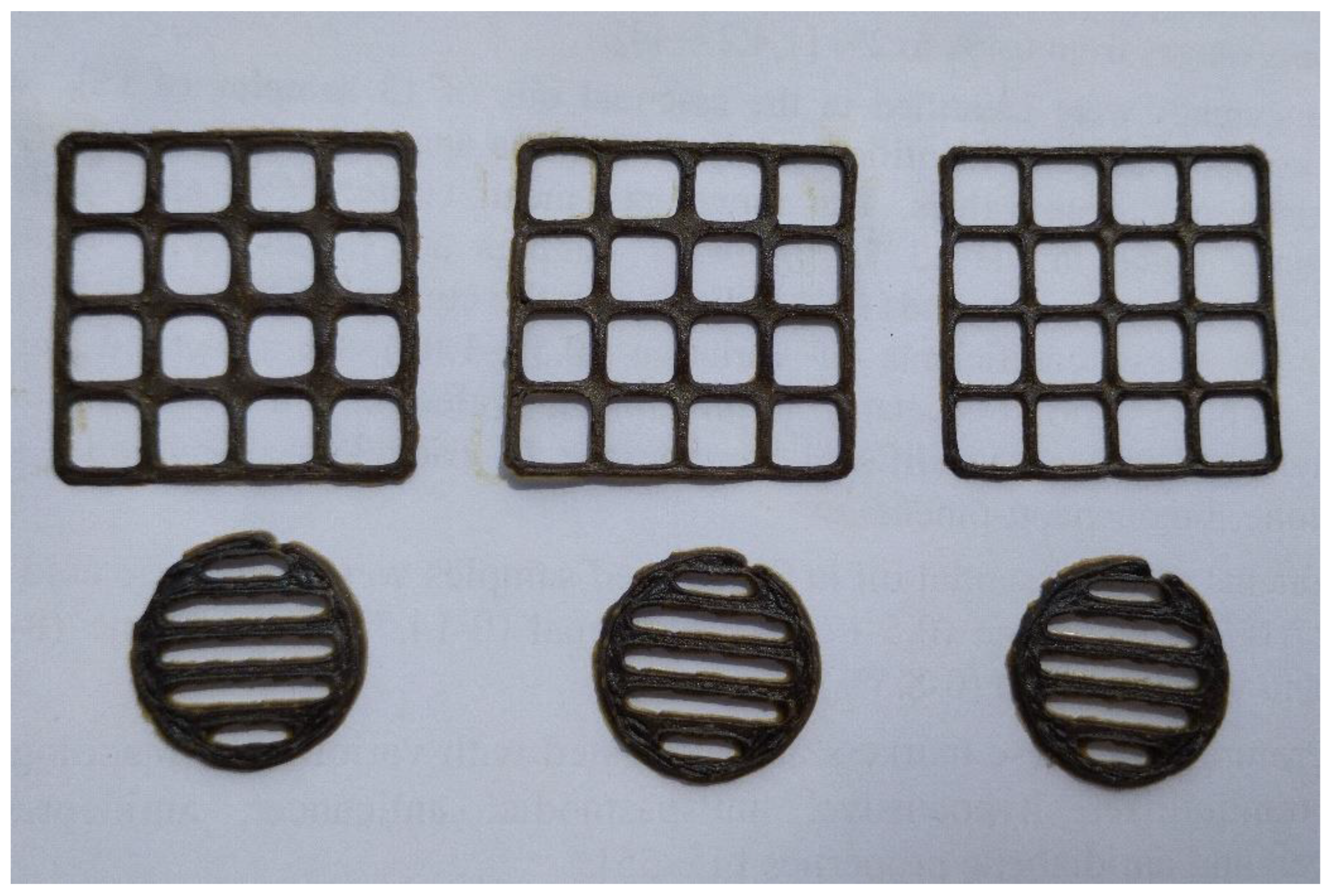

2.3. Novel 3D-Printed oral Dosage Forms for the Verbena Officinalis Extract

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Assay of Main Phytochemicals by Spectrophotometry

4.3. Analysis of Phenolic Compounds by LC-MS/MS

4.4. Assay of Amino Acids by LC-MS/MS

4.5. Pharmacological Research

4.6. Three-Dimensional (3D) Printing of V. Officinalis Extracts

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vélez-Gavilán, J. Verbena Officinalis (Vervain) 2020, 56184.

- Kubica, P.; Szopa, A.; Dominiak, J.; Luczkiewicz, M.; Ekiert, H. Verbena Officinalis (Common Vervain)—A Review on the Investigations of This Medicinally Important Plant Species. Planta Med 2020, 86, 1241–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehecho, S.; Hidalgo, O.; García-Iñiguez De Cirano, M.; Navarro, I.; Astiasarán, I.; Ansorena, D.; Cavero, R.Y.; Calvo, M.I. Chemical Composition, Mineral Content and Antioxidant Activity of Verbena Officinalis L. LWT—Food Science and Technology 2011, 44, 875–882. [CrossRef]

- Shu, J.; Chou, G.; Wang, Z. Two New Iridoids from Verbena Officinalis L. Molecules 2014, 19, 10473–10479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Xin, F.; Sha, Y.; Fang, J.; Li, Y.-S. Two New Secoiridoid Glycosides from Verbena Officinalis. Journal of Asian Natural Products Research 2010, 12, 649–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubica, P.; Szopa, A.; Kokotkiewicz, A.; Miceli, N.; Taviano, M.F.; Maugeri, A.; Cirmi, S.; Synowiec, A.; Gniewosz, M.; Elansary, H.O.; et al. Production of Verbascoside, Isoverbascoside and Phenolic Acids in Callus, Suspension, and Bioreactor Cultures of Verbena Officinalis and Biological Properties of Biomass Extracts. Molecules 2020, 25, 5609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Wakil, E.S.; El-Shazly, M.A.M.; El-Ashkar, A.M.; Aboushousha, T.; Ghareeb, M.A. Chemical Profiling of Verbena Officinalis and Assessment of Its Anti-Cryptosporidial Activity in Experimentally Infected Immunocompromised Mice. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2022, 15, 103945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gan, Y.; Yu, J.; Ye, X.; Yu, W. Key Ingredients in Verbena Officinalis and Determination of Their Anti-Atherosclerotic Effect Using a Computer-Aided Drug Design Approach. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1154266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibitz-Eisath, N.; Eichberger, M.; Gruber, R.; Sturm, S.; Stuppner, H. Development and Validation of a Rapid Ultra-High Performance Liquid Chromatography Diode Array Detector Method for Verbena Officinalis L. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2018, 160, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falleh, H.; Hafsi, C.; Mohsni, I.; Ksouri, R. Évaluation de Différents Procédés d’extraction Des Composés Phénoliques d’une Plante Médicinale: Verbena Officinalis. Biologie Aujourd’hui 2021, 215, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raal, A.; Dolgošev, G.; Ilina, T.; Kovalyova, A.; Lepiku, M.; Grytsyk, A.; Koshovyi, O. The Essential Oil Composition in Commercial Samples of Verbena Officinalis L. Herb from Different Origins. Crops 2025, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Martino, L.; D’Arena, G.; Minervini, M.M.; Deaglio, S.; Fusco, B.M.; Cascavilla, N.; De Feo, V. Verbena Officinalis Essential Oil and Its Component Citral as Apoptotic-Inducing Agent in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2009, 22, 1097–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohini, K.; Mohini, U.; Amrita, K.; Aishwarya, Z.; Disha, S.; Padmaja, K. Verbena Officinalis (Verbenaceae): Pharmacology, Toxicology and Role in Female Health. IJAM 2022, 13, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posatska, N.M.; Grytsyk, A.R.; Struk, O.A. RESEARCH OF STEROID AND VOLATILE COMPOUNDS IN VERBENA OFFICINALIS L. HERB. Scientific and practical journal 2024, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jin, H.; Qin, J.; Fu, J.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, W. Chemical Constituents from Verbena Officinalis. Chem Nat Compd 2011, 47, 319–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Pharmacopoeia; 11th ed.; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, 2022.

- Chevallier, A. Encyclopedia of Herbal Medicine; Second edition.; DK Publishing Inc., 2000.

- Popova, A.; Mihaylova, D.; Spasov, A. Plant-Based Remedies with Reference to Respiratory Diseases—A Review. TOBIOTJ 2021, 15, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovich, V.I.; Beketova, H.V. Results of a Randomised Controlled Study on the Efficacy of a Combination of Saline Irrigation and Sinupret Syrup Phytopreparation in the Treatment of Acute Viral Rhinosinusitis in Children Aged 6 to 11 Years. Clin Phytosci 2018, 4, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziurka, M.; Kubica, P.; Kwiecień, I.; Biesaga-Kościelniak, J.; Ekiert, H.; Abdelmohsen, S.A.M.; Al-Harbi, F.F.; El-Ansary, D.O.; Elansary, H.O.; Szopa, A. In Vitro Cultures of Some Medicinal Plant Species (Cistus × Incanus, Verbena Officinalis, Scutellaria Lateriflora, and Scutellaria Baicalensis) as a Rich Potential Source of Antioxidants—Evaluation by CUPRAC and QUENCHER-CUPRAC Assays. Plants 2021, 10, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrytsyk, A.R.; Posatska, N.M.; Klymenko, А.O. OBTAINING AND STUDY OF PROPERTIES OF EXTRACTS VERBENA OFFICINALIS. Pharmaceutical review. 2016, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, E.; García-Mina, J.M.; Calvo, M.I. Antioxidant and Antifungal Activity of Verbena Officinalis L. Leaves. Plant Foods Hum Nutr 2008, 63, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Liu, X.; Ma, D.; Hua, X.; Jin, N. Optimization of Polysaccharides Extracted from Verbena Officinalis L and Their Inhibitory Effects on Invasion and Metastasis of Colorectal Cancer Cells. Trop. J. Pharm Res 2017, 16, 2387–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Encalada, M.A.; Rehecho, S.; Ansorena, D.; Astiasarán, I.; Cavero, R.Y.; Calvo, M.I. Antiproliferative Effect of Phenylethanoid Glycosides from Verbena Officinalis L. on Colon Cancer Cell Lines. LWT—Food Science and Technology 2015, 63, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, R.; Adhikary, S.; Ahmad, S.; Alam, M.A. In Vitro Antimelanoma Properties of Verbena Officinalis Fractions. Molecules 2022, 27, 6329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kou, W.-Z.; Yang, J.; Yang, Q.-H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.-F.; Xu, S.-L.; Liu, J. Study on In-Vivo Anti-Tumor Activity of Verbena Officinalis Extract. Afr. J. Trad. Compl. Alt. Med. 2013, 10, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharachorloo, M.; Amouheidari, M. Chemical Composition, Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities of the Essential Oil Isolated from Verbena Officinalis. Journal of Food Biosciences and Technology 2016, 6, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchooli, N.; Saeidi, S.; Barani, H.K.; Sanchooli, E. In Vitro Antibacterial Effects of Silver Nanoparticles Synthesized Using Verbena Officinalis Leaf Extract on Yersinia Ruckeri, Vibrio Cholera and Listeria Monocytogenes. Iran J Microbiol 2018, 10, 400–408. [Google Scholar]

- Ashfaq, A.; Khan, A.; Minhas, A.M.; Aqeel, T.; Assiri, A.M.; Bukhari, I.A. Anti-Hyperlipidemic Effects of Caralluma Edulis (Asclepiadaceae) and Verbena Officinalis (Verbenaceae) Whole Plants against High-Fat Diet-Induced Hyperlipidemia in Mice. Trop. J. Pharm Res 2017, 16, 2417–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Oliveira, S.M.; Dias, E.; Girol, A.P.; Silva, H.; Pereira, M.D.L. Exercise Training and Verbena Officinalis L. Affect Pre-Clinical and Histological Parameters. Plants 2022, 11, 3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekara, A.; Amazouz, A.; Benyamina Douma, T. Evaluating the Antidepressant Effect of Verbena Officinalis L. (Vervain) Aqueous Extract in Adult Rats. Basic Clin. Neurosci. J. 2020, 91–98. [CrossRef]

- Jawaid, T.; Imam, S.A.; Kamal, M. Antidepressant Activity of Methanolic Extract of Verbena Officinalis Linn. Plant in Mice. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research 2015, 8, 308–310. [Google Scholar]

- Rashidian, A.; Kazemi, F.; Mehrzadi, S.; Dehpour, A.R.; Mehr, S.E.; Rezayat, S.M. Anticonvulsant Effects of Aerial Parts of Verbena Officinalis Extract in Mice: Involvement of Benzodiazepine and Opioid Receptors. J Evid Based Complementary Altern Med 2017, 22, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kravchenko, G.; Krasilnikova, O.; Raal, A.; Mazen, M.; Chaika, N.; Kireyev, I.; Grytsyk, A.; Koshovyi, O. Arctostaphylos Uva-Ursi L. Leaves Extract and Its Modified Cysteine Preparation for the Management of Insulin Resistance: Chemical Analysis and Bioactivity. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2022, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshovyi, O.; Sepp, J.; Jakštas, V.; Žvikas, V.; Kireyev, I.; Karpun, Y.; Odyntsova, V.; Heinämäki, J.; Raal, A. German Chamomile (Matricaria Chamomilla L.) Flower Extract, Its Amino Acid Preparations and 3D-Printed Dosage Forms: Phytochemical, Pharmacological, Technological, and Molecular Docking Study. IJMS 2024, 25, 8292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshovyi, O.; Vlasova, I.; Jakštas, V.; Vilkickytė, G.; Žvikas, V.; Hrytsyk, R.; Grytsyk, L.; Raal, A. American Cranberry (Oxycoccus Macrocarpus (Ait.) Pursh) Leaves Extract and Its Amino-Acids Preparation: The Phytochemical and Pharmacological Study. Plants 2023, 12, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDougall, C. Pharmacokinetics of Valaciclovir. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2004, 53, 899–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpov, Yu.A. Perindopril Arginine: A New ACE Inhibitor Salt Increases Therapeutic Potential. Cardiovascular therapy and prevention 2008, 7, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Koshovyi, O.; Raal, A.; Kireyev, I.; Tryshchuk, N.; Ilina, T.; Romanenko, Y.; Kovalenko, S.M.; Bunyatyan, N. Phytochemical and Psychotropic Research of Motherwort (Leonurus Cardiaca L.) Modified Dry Extracts. Plants 2021, 10, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshovyi, O.; Granica, S.; Piwowarski, J.P.; Stremoukhov, O.; Kostenko, Y.; Kravchenko, G.; Krasilnikova, O.; Zagayko, A. Highbush Blueberry (Vaccinium Corymbosum L.) Leaves Extract and Its Modified Arginine Preparation for the Management of Metabolic Syndrome—Chemical Analysis and Bioactivity in Rat Model. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azad, M.A.; Olawuni, D.; Kimbell, G.; Badruddoza, A.Z.M.; Hossain, Md.S.; Sultana, T. Polymers for Extrusion-Based 3D Printing of Pharmaceuticals: A Holistic Materials–Process Perspective. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Aita, I.; Rahman, J.; Breitkreutz, J.; Quodbach, J. 3D-Printing with Precise Layer-Wise Dose Adjustments for Paediatric Use via Pressure-Assisted Microsyringe Printing. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2020, 157, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshovyi, O.; Heinämäki, J.; Raal, A.; Laidmäe, I.; Topelius, N.S.; Komisarenko, M.; Komissarenko, A. Pharmaceutical 3D-Printing of Nanoemulsified Eucalypt Extracts and Their Antimicrobial Activity. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2023, 187, 106487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanov, O.V. Preclinical Studies of Drugs; Avicenna: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Prokopchuk, О.G.; Aleksandrova, O.I.; Kravchenko, I.A. Study of the Dynamics of Anticonvulsant and Anxiolytic Action after Oral Administration of Tin (II) Chloride. Rep. of Vinnytsia Nation. Med. Univ. 2019, 23, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovchiga, O.V.; Shtrygol’, S.J.; Balia, A.A. The Influence of Goutweed (Aegopodium Podagraria l.) Extract and Tincture on the Behavioural Reactions Of Mice against the Background of Caffeine-Sodium Benzoate. Klìn. farm. 2018, 22, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Jalwal, P.; Dahiya, J.; Khokhara, S. Research Methods for Animal Studies of the Anxiolytic Drugs. The Pharma Innovation Journal 2016, 5, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Cryan, J.F.; Mombereau, C.; Vassout, A. The Tail Suspension Test as a Model for Assessing Antidepressant Activity: Review of Pharmacological and Genetic Studies in Mice. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2005, 29, 571–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steru, L.; Chermat, R.; Thierry, B.; Simon, P. The Tail Suspension Test: A New Method for Screening Antidepressants in Mice. Psychopharmacology 1985, 85, 367–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gojak-Salimović, S.; Alijagić, N.; Ramić, S. Investigation of Antioxidant Activity of Gallic, Protocatechuic and Vanilic Acid Using the Briggs-Rauscher Reaction as Tool. Glas. hem. tehnol. Bosne Herceg. 2023, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A.P.G.; Sganzerla, W.G.; John, O.D.; Marchiosi, R. A Comprehensive Review of the Classification, Sources, Biosynthesis, and Biological Properties of Hydroxybenzoic and Hydroxycinnamic Acids. Phytochem Rev 2025, 24, 1061–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enogieru, A.B.; Haylett, W.; Hiss, D.C.; Bardien, S.; Ekpo, O.E. Rutin as a Potent Antioxidant: Implications for Neurodegenerative Disorders. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2018, 2018, 6241017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshpurkar, A.; Saluja, A.K. The Pharmacological Potential of Rutin. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2017, 25, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dhabi, N.A.; Valan Arasu, M.; Park, C.H.; Park, S.U. An Up-to-Date Review of Rutin and Its Biological and Pharmacological Activities. EXCLI Journal; 14:Doc59; ISSN 1611-2156 2015. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.V.; Nguyen, K.D.A.; Ma, C.-T.; Nguyen, Q.-T.; Nguyen, H.T.H.; Yang, D.-J.; Tran, T.L.; Kim, K.W.; Doan, K.V. P-Coumaric Acid Enhances Hypothalamic Leptin Signaling and Glucose Homeostasis in Mice via Differential Effects on AMPK Activation. IJMS 2021, 22, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X. Research Progress on the Mechanisms of Protocatechuic Acid in the Treatment of Cognitive Impairment. Molecules 2024, 29, 4724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Zhang, X.; Lv, C.; Li, C.; Yu, Y.; Wang, X.; Han, F. Protocatechuic Acid Ameliorates Neurocognitive Functions Impairment Induced by Chronic Intermittent Hypoxia. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 14507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogut, E.; Armagan, K.; Gül, Z. The Role of Syringic Acid as a Neuroprotective Agent for Neurodegenerative Disorders and Future Expectations. Metab Brain Dis 2022, 37, 859–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperringer, J.E.; Addington, A.; Hutson, S.M. Branched-Chain Amino Acids and Brain Metabolism. Neurochem Res 2017, 42, 1697–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ren, H.; Guo, X.; Han, L. Branched-Chain Amino Acids and the Risks of Dementia, Alzheimer’s Disease, and Parkinson’s Disease. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2024, 16, 1369493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holeček, M. Branched-Chain Amino Acids in Health and Disease: Metabolism, Alterations in Blood Plasma, and as Supplements. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2018, 15, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouyaala, O.; Bougrine, S.; Brikat, S.; Brouzi, M.Y.E.; Elhessni, A.; Mesfioui, A.; Ouahidi, M.L. The Anxiolytic, Anti-Depressive, and Antioxidative Effects of Lemon Verbena in Rat Rendered Diabetic by Streptozotocin Injection. Neurosci Behav Physi 2025, 55, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.W.; Khan, A.; Ahmed, T. Anticonvulsant, Anxiolytic, and Sedative Activities of Verbena Officinalis. Front. Pharmacol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cowen, P.J.; Williamson, D.J.; McTavish, S.F.B. Effect of Valine on 5-HT Neurotransmission and Mood. In Recent Advances in Tryptophan Research; Filippini, G.A., Costa, C.V.L., Bertazzo, A., Eds.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer US: Boston, MA, 1996; Vol. 398, pp. 67–71 ISBN 978-1-4613-8026-9.

- Singh, N.; Ecker, G.F. Insights into the Structure, Function, and Ligand Discovery of the Large Neutral Amino Acid Transporter 1, LAT1. IJMS 2018, 19, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Cai, X.; Zhao, J.; Yan, Z. Serotonin Receptors Modulate GABAA Receptor Channels through Activation of Anchored Protein Kinase C in Prefrontal Cortical Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 6502–6511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rautio, J.; Gynther, M.; Laine, K. LAT1-Mediated Prodrug Uptake: A Way to Breach the Blood–Brain Barrier? Therapeutic Delivery 2013, 4, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Huang, W.; Harris, M.B.; Goolsby, J.M.; Venema, R.C. Interaction of the Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase with the CAT-1 Arginine Transporter Enhances NO Release by a Mechanism Not Involving Arginine Transport. Biochemical Journal 2005, 386, 567–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banjarnahor, S.; König, J.; Maas, R. Screening of Commonly Prescribed Drugs for Effects on the CAT1-Mediated Transport of l-Arginine and Arginine Derivatives. Amino Acids 2022, 54, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shima, Y.; Maeda, T.; Aizawa, S.; Tsuboi, I.; Kobayashi, D.; Kato, R.; Tamai, I. L-Arginine Import via Cationic Amino Acid Transporter CAT1 Is Essential for Both Differentiation and Proliferation of Erythrocytes. Blood 2006, 107, 1352–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koshovyi, O.; Hrytsyk, Y.; Perekhoda, L.; Suleiman, M.; Jakštas, V.; Žvikas, V.; Grytsyk, L.; Yurchyshyn, O.; Heinämäki, J.; Raal, A. Solidago Canadensis L. Herb Extract, Its Amino Acids Preparations and 3D-Printed Dosage Forms: Phytochemical, Technological, Molecular Docking and Pharmacological Research. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshovyi, O.; Heinämäki, J.; Laidmäe, I.; Topelius, N.S.; Grytsyk, A.; Raal, A. Semi-Solid Extrusion 3D-Printing of Eucalypt Extract-Loaded Polyethylene Oxide Gels Intended for Pharmaceutical Applications. Annals of 3D Printed Medicine 2023, 12, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kute, V.G.; Patil, R.S.; Kute, V.G.; Kaluse, P.D. Immediate-Release Dosage Form; Focus on Disintegrants Use as a Promising Excipient. J. Drug Delivery Ther. 2023, 13, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohalkar, R.; Poul, B.; Patil, S.S.; Hetkar, M.A.; Chavan, S.D. A Review on Immediate Release Drug Delivery Systems. PharmaTutor 2014, 2, 95–109. [Google Scholar]

- Kovaleva, A.M.; Georgievskyi, G.V.; Kovalev, V.M.; et al. Development of the Method of Standardization of the New Medicinal Product Piflamin. Pharmacom 2002, 92–97. [Google Scholar]

- Krivoruchko, E.; Markin, A.; Samoilova, V.A.; Ilina, T.; Koshovyi, O. Research in the Chemical Composition of the Bark of Sorbus Aucuparia. Ceska a Slovenska Farmacie 2018, 67, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riguene, H.; Moussaoui, Y.; Salem, R.B.; Rigane, G. Response Surface Methodology as a Predictive Tool and UPLC-HRMS Analysis of Phenolic Rich Extract from Verbena Officinalis L. Using Microwave-Assisted Extraction: Part I. Chemistry Africa 2023, 6, 2857–2869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polumackanycz, M.; Petropoulos, S.A.; Añibarro-Ortega, M.; Pinela, J.; Barros, L.; Plenis, A.; Viapiana, A. Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Common and Lemon Verbena. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata Flores, E.D.J.; Herodes, K.; Leito, I. Comparison of the Ionisation Mode in the Determination of Free Amino Acids in Beers by Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A 2022, 1677, 463320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciel, L.S.; Marengo, A.; Rubiolo, P.; Leito, I.; Herodes, K. Derivatization-Targeted Analysis of Amino Compounds in Plant Extracts in Neutral Loss Acquisition Mode by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Journal of Chromatography A 2021, 1656, 462555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Law of Ukraine No. 3447-IV of 21.02.2006 “On the Protection of Animals from Cruelty” (as amended and supplemented). 2006.

- On Approval of the Procedure for Preclinical Study of Medicinal Products and Examination of Materials of Preclinical Study of Medicinal Products; 2009.

- European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals Used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes 1999.

- Viidik, L.; Seera, D.; Antikainen, O.; Kogermann, K.; Heinämäki, J.; Laidmäe, I. 3D-Printability of Aqueous Poly(Ethylene Oxide) Gels. European Polymer Journal 2019, 120, 109206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegel, J.; Mayer, W.; Havre, Y.V. FreeCAD 2001.

- State Pharmacopoeia of Ukraine; 2nd ed.; Ukrainian Scientific Pharmacopoeial Center of Drugs Quality: Kharkiv, Ukraine, 2015.

- Lapach, S.N.; Chubenko, A.V.; Babich, P.N. Statistical Methods in Biomedical Research Using Excel; MORION: Kyiv, 2000.

| Compound | Content in the dry extract, mg/kg | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 (extractant 70% ethanol) |

V2 (extractant water) |

V1-Gly | V1-Phe | V1-Lys | V1-Val | V1-Arg | |

| Phenolic compounds | |||||||

| p-Coumaric acid | 14 ± 3 | 25 ± 5 | 8 ± 1 | 13 ± 1 | 15 ± 2 | 15 ± 1 | 12 ± 5 |

| Quercetin | 285 ± 10 | 137 ± 6 | 137 ± 8 | 231 ± 11 | 240 ± 3 | 217 ± 5 | 208 ± 8 |

| Gallic acid | 11 ± 3 | 102 ±14 | 13 ±1 | 16 ±2 | 13 ±1 | 13 ±1 | 11 ±1 |

| Protocatechuic acid | 79 ± 11 | 116 ± 27 | 91 ± 14 | 168 ± 12 | 78 ± 11 | 82 ± 11 | 76 ± 8 |

| Syringic acid | 54 ± 3 | 101 ± 6 | 51 ± 7 | 62 ± 15 | 70 ± 8 | 66 ± 11 | 60 ± 7 |

| Isovanillin | 5405 ± 1432 | 6414 ± 1514 | 983 ± 281 | 5435 ± 847 | 824 ± 70 | 3401 ± 533 | 2519 ± 354 |

| Ferulic acid | 33 ± 1 | 53 ± 5 | 21 ± 3 | 36 ± 3 | 35 ± 1 | 31 ± 2 | 27 ± 2 |

| Rutin | 14 ± 2 | 7 ± 1 | 6 ± 0 | 16 ± 1 | 14 ± 0 | 11 ± 1 | 10 ± 1 |

| Amino acids | |||||||

| Histidine | 27 ± 4 | 52 ± 4 | 17 ± 3 | 33 ± 7 | 31 ± 9 | 27 ± 7 | 23 ± 6 |

| Arginine | 187 ± 7 | 289 ± 8 | 154 ± 6 | 216 ± 14 | 195 ± 9 | 175 ± 13 | 134100 ± 2600 |

| Asparagine | 1253 ± 56 | 2238 ± 77 | 1114 ± 51 | 1533 ± 24 | 1265 ± 93 | 1141 ± 41 | 1196 ± 46 |

| Glutamine | 4995 ± 533 | 666 ± 37 | 3958 ± 124 | 5839 ± 27 | 5574 ± 1219 | 4501 ± 324 | 4612 ± 333 |

| Serine | 329 ± 22 | 421 ± 14 | 317 ± 10 | 411 ± 10 | 356 ± 34 | 326 ± 11 | 310 ± 9 |

| Aspartic acid | 345 ± 36 | 359 ± 36 | 295 ± 6 | 331 ± 29 | 306 ± 50 | 292 ± 22 | 286 ± 16 |

| Glycine | 46 ± 5 | 90 ± 5 | 58500 ± 1900 | 489 ± 8 | 57 ± 8 | 72 ± 4 | 54 ± 2 |

| Threonine | 121 ± 3 | 181 ± 3 | 128 ± 4 | 172 ± 1 | 132 ± 8 | 120 ± 3 | 118 ± 2 |

| β-Alanine | 29 ± 6 | 43 ± 7 | 34 ± 2 | 50 ± 2 | 33 ± 7 | 28 ± 5 | 37 ± 3 |

| α-Alanine | 721 ± 30 | 915 ±45 | 763 ± 9 | 919 ± 12 | 789 ± 65 | 950 ± 24 | 722 ± 13 |

| Tyrosine | 71 ± 4 | 113 ± 1 | 70 ± 3 | 167 ± 4 | 73 ± 1 | 114 ± 4 | 75 ± 7 |

| Valine | 97 ± 22 | 305 ± 47 | 196 ±21 | 333 ±50 | 135 ±32 | 85900 ±3000 | 102 ± 32 |

| Tryptophan | 56 ± 9 | 74 ± 9 | 50 ± 4 | 78 ± 9 | 56 ± 6 | 53 ± 6 | 46 ± 8 |

| Phenylalanine | 48 ± 11 | 106 ± 7 | 93 ± 6 | 183500 ± 5600 | 57 ± 11 | 123 ± 8 | 55 ± 8 |

| Isoleucine | 93 ± 28 | 182 ± 26 | 124 ± 9 | 379 ± 28 | 94 ± 20 | 249 ± 23 | 108 ± 25 |

| Leucine | 73 ±6 | 182 ±4 | 97 ±4 | 999 ±34 | 78 ±3 | 814 ±40 | 86 ± 6 |

| Lysine | 26 ±12 | 67 ±13 | 27 ± 3 | 50 ± 7 | 68000 ± 4200 | 53 ± 10 | 29 ± 8 |

| Spectrophotometry, % | |||||||

| Hydroxycinnamic acids (chlorogenic acid equivalents, spectrophotometry), % | 5.79 ± 0.39 | 3.95 ± 0.31 | 5.51 ± 0.73 | 5.15 ± 0.47 | 4.46 ± 0.43 | 4.34 ± 0.67 | 3.78 ± 0.75 |

| Flavonoids (rutin equivalents, spectrophotometry), % | 2.91 ± 0.12 | 2.00 ± 0.09 | 2.48 ± 0.05 | 2.39 ± 0.06 | 2.27 ± 0.06 | 2.24 ± 0.08 | 2.07 ± 0.04 |

| Total phenolic compounds (gallic acid equivalents, spectrophotometry), % | 7.77 ± 0.28 | 5.75 ± 0.25 | 6.76 ± 0.38 | 6.26 ± 0.10 | 5.93 ± 0.18 | 5.85 ± 0.18 | 5.56 ± 0.16 |

| Investigated indicator | Intact animals | Comparison group (Sedaphyton) | V1 (extractant 70% ethanol) |

V2 (extractant water) |

V1-Gly | V1-Phe | V1-Lys | V1-Val | V1-Arg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of crossed squares | 75.33±5.68 | 73.17±5.85 | 79.50±4.55 | 94.17±6.64 */** | 80.50±8.24 | 83.50±3.77 | 81.50±5.96 | 50.33±5.27*/** | 67.83±7.46 |

| Number of vertical stands | 10.50±1.77 | 7.83±0.91 | 12.17±1.25** | 11.17±1.05** | 7.33±0.67* | 10.67±1.02** | 9.00±0.58 | 6.67±1.09* | 4.33±0.49*/** |

| Number of hole explorations | 14.17±1.08 | 2.83±0.48* | 12.50±0.76** | 12.17±0.98** | 11.00±1.39** | 8.17±0.48*/** | 9.83±0.95*/** | 2.17±0.60* | 3.17±0.60* |

| Conditional units of exploratory research activity | 3 | 1.91 | 3.10 | 3.17 | 2.54 | 2.70 | 2.58 | 1.45 | 1.53 |

| Boluses | 1.33±0.33 | 1.50±0.81 | 1.50±0.22 | 2.33±0.42 | 2.67±0.56 | 1.33±0.21 | 1.00±0.26 | 1.67±0.21 | 1.17±0.60 |

| Grooming | 0.67±0.21 | 0.33±0.33 | 1.17±0.31 | 0.67±0.33 | 0.67±0.21 | 0.83±0.17 | 1.00±0.26 | 0.5±0.22 | 0.33±0.21 |

| Conditional units of emotional reaction indicators | 2 | 1.62 | 2.87 | 2.75 | 3 | 2.25 | 2.25 | 2 | 1.37 |

| Conditional units of all activities | 5 | 3.54 | 5.97 | 5.92 | 5.54 | 4.95 | 4.83 | 3.45 | 2.91 |

| Group of animals | Time spent in the open arm of the maze, s | Time spent in the closed arm of the maze, s. | Number of peeks from the closed arm | Number of crossings over the central platform | Number of downward glances from the ends of open arms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact animals | 24.17±3.95 | 273.17±5.40 | 10.50±1.80 | 3.33±1.2 | 4.67±0.61 |

| Comparison group (Sedaphyton) | 18.50±1.84 | 279.00±8.54 | 3.33±0.42* | 1.00±0.37* | 3.00±0.63* |

| V1 (extractant 70% ethanol) |

54.67±2.80*/** | 235.67±5.52*/** | 8.50±0.43** | 8.50±1.06*/** | 10.17±1.05*/** |

| V2 (extractant water) |

24.00±2.53 | 270.17±3.84 | 10.83±1.35** | 6.33±0.92*/** | 5.33±0.42** |

| V1-Gly | 29.33±2.75** | 262.50±6.57 | 3.17±0.40* | 3.83±0.06** | 4.33±0.42 |

| V1-Phe | 59.50±4.21*/** | 238.00±5.85*/** | 10.33±0.49** | 8.50±1.06*/** | 11.33±1.20*/** |

| V1-Lys | 47.17±3.32*/** | 250.50±8.50*/** | 8.00±0.58*/** | 5.50±1.52** | 11.00±1.41*/** |

| V1-Val | 9.50±1.43*/** | 287.17±1.96* | 2.67±0.42*/** | 1.83±0.48* | 1.00±0.37*/** |

| V1-Arg | 23.50±2.01 | 275.00±5.94 | 4.67±1.02*/** | 3.00±0.68** | 3.83±1.25 |

| Group of animals | Time spent in the dark compartment, s | Number of peeks from the dark compartment | Time spent in the illuminated compartment, s | Number of exits into the illuminated compartment | Average time of a single stay in the illuminated compartment, s |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact animals | 101.00±4.93 | 5.83±1.17 | 78.33±4.89 | 4.83±0.31 | 16.73±1.87 |

| Comparison group (Sedaphyton) | 119.00±5.16* | 2.17±0.70* | 59.67±4.67* | 3.33±0.71* | 25.68±9.18 |

| V1 (extractant 70% ethanol) |

24.67±5.28*/** | 2.00±1.06* | 100.33±5.28*/** | 3.17±0.91 | 47.98±12.85** |

| V2 (extractant water) |

98.33±6.82** | 7.00±1.15** | 80.17±6.84** | 5.83±0.54 | 14.14±1.48 |

| V1-Gly | 75.67±6.58*/** | 2.33±0.61* | 103.00±6.61*/** | 7.33±0.71*/** | 14.60±1.33 |

| V1-Phe | 73.67±5.49*/** | 2.17±1.22 | 105.5±5.60*/** | 6.33±0.61** | 17.43±1.82 |

| V1-Lys | 97.67±10.55 | 3.83±1.11 | 82.00±10.56 | 5.33±0.42** | 15.60±1.97 |

| V1-Val | 104.33±9.27 | 3.17±1.08 | 75.33±9.28 | 4.83±0.87 | 20.23±6.57 |

| V1-Arg | 126.67±6.80* | 2.67±0.92 | 53.83±7.06* | 5.50±1.12 | 11.66±2.66 |

| Group of animals | Total immobility time, s |

|---|---|

| Intact animals | 103.67±5.00 |

| Comparison group (Sedaphyton) | 190.67±12.44* |

| V1 (extractant 70% ethanol) | 84.67±5.38*/** |

| V2 (extractant water) | 125.00±3.01*/** |

| V1-Gly | 124.83±7.96** |

| V1-Phe | 97.50±5.76** |

| V1-Lys | 99.67±6.25** |

| V1-Val | 177.50±8.11* |

| V1-Arg | 133.67±7.29*/** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).