Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

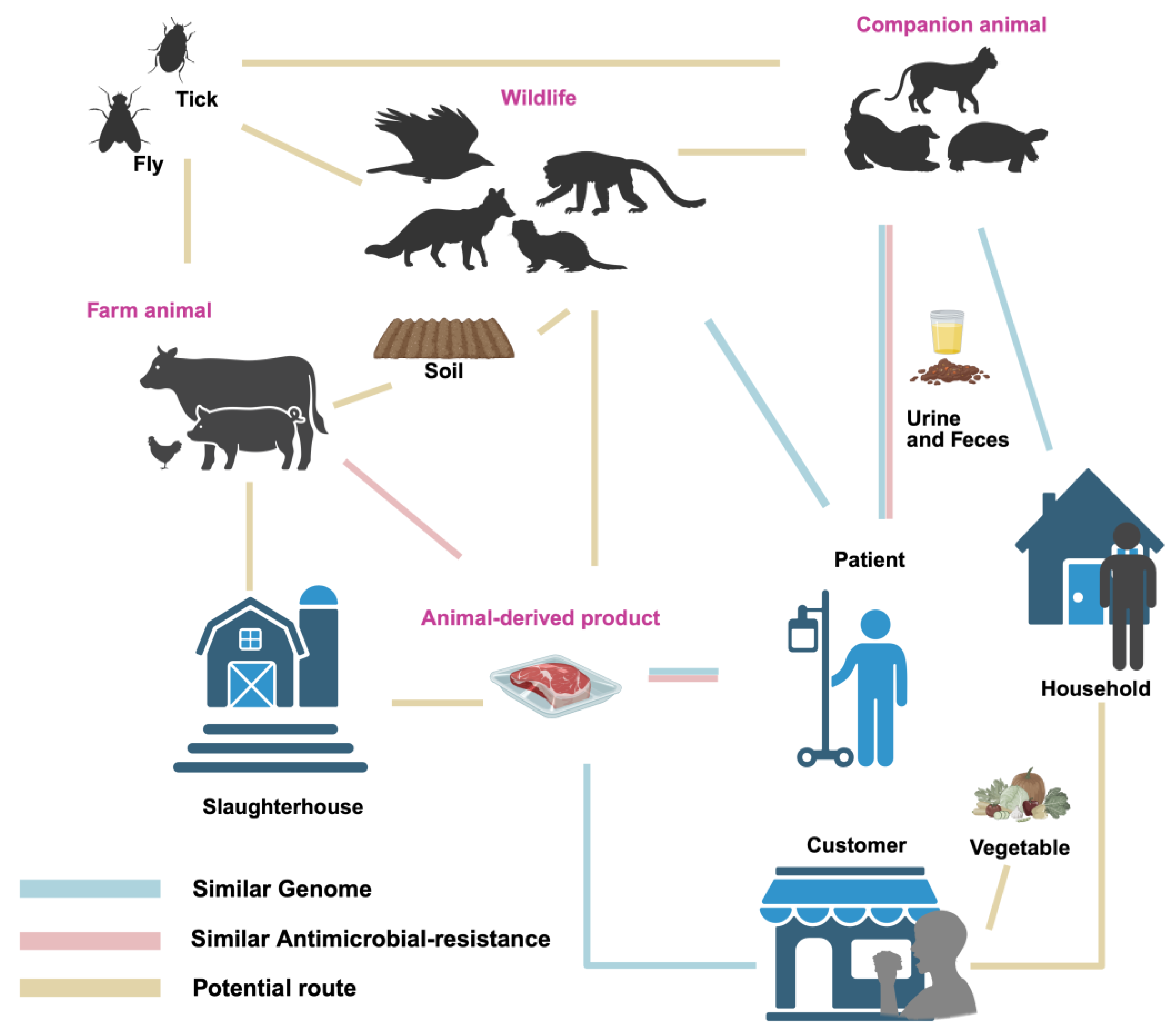

2. The Detection of P. mirabilis in Animals

3. Detection of P. mirabilis in Animal-Derived Foods

4. Genomic Similarity Between Animal- and Human-Derived P. mirabilis

5. Pathogenicity of P. mirabilis in Humans and Animals

6. Antibiotic Resistance of P. mirabilis from Animals and Animal-Derived Products

7. Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| P. mirabilis | Proteus mirabilis |

| NDRJ | multi-drug resistant |

| XDR | extensively drug-resistant |

| PDR | pan-drug-resistant |

References

- Adeolu, M.; Alnajar, S.; Naushad, S.; Gupta, R.S. Genome-Based Phylogeny and Taxonomy of the ‘Enterobacteriales’: Proposal for Enterobacterales Ord. Nov. Divided into the Families Enterobacteriaceae, Erwiniaceae Fam. Nov., Pectobacteriaceae Fam. Nov., Yersiniaceae Fam. Nov., Hafniaceae Fam. Nov., Morganellaceae Fam. Nov., and Budviciaceae Fam. Nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016, 66, 5575–5599.

- Liu, H.; Xia, N.; Suksawat, F.; Tengjaroenkul, B.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Li, X.; Huang, C.; Bao, Y.; Wu, Q.; et al. Prevalence and Characterization of IncQ1α-Mediated Multi-Drug Resistance in Proteus Mirabilis Isolated from Pigs in Kunming, Yunnan, China. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1483633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr O’hara, C.; Brenner, F.W.; Miller, J.M. Classification, Identification, and Clinical Significance of Proteus, Providencia, and Morganella. Clin Microbiol Rev 2000, 13, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chai, J. Research Progress on Proteus mirabilis. Chin Vet Sci 2017, 37, 196–200. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zahng, Z.; Wang, S.; Liu,Y. Mixed infection and drug sensitivity analysis of Escherichia coli, Proteus mirabilis and coccidia from rabbits. Acta Vet. Zootech. Sin. 2024, 55, 4204–4212.

- Ali, S.; Karaynir, A.; Salih, H.; Öncü, S.; Bozdoğan, B. Characterization, Genome Analysis and Antibiofilm Efficacy of Lytic Proteus Phages RP6 and RP7 Isolated from University Hospital Sewage. Virus Res 2023, 326, 199049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienes, L. Reproductive Processes in Proteus Cultures. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. 1946, 63, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y, Isolation. Identification, and Analysis of Drug Resistance and Virulence Genes of ESBLs-Producing Proteus mirabilis from Fur - Bearing Animals. Master’s Professional Degree Thesis, Shandong Agricultural University, Tai’an, June 2021.

- Cobbley, H.K.; Evans, S.I.; Brown, H.M.F.; Eberhard, B.; Eberhard, N.; Kim, M.; Moe, H.M.; Schaeffer, D.; Sharma, R.; Thompson, D.W.; et al. Complete Genome Sequences of Six Chi-Like Bacteriophages That Infect Proteus and Klebsiella. Microbiol Resour Announc 2022, 11, e01215–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.J.; Navarro, N.; Cruz, E.; Sánchez, S.; Morales, J.O.; Zunino, P.; Robino, L.; Lima, A.; Scavone, P. First Report on the Physicochemical and Proteomic Characterization of Proteus Mirabilis Outer Membrane Vesicles under Urine-Mimicking Growth Conditions: Comparative Analysis with Escherichia Coli. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1493859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drzewiecka, D. Significance and Roles of Proteus Spp. Bacteria in Natural Environments. Microb Ecol 2016, 72, 741–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, J.D.; Bens, L.; Santos, A.J. do C.; Lavigne, R.; Soares, J.; Melo, L.D.R.; Vallino, M.; Dias, R.S.; Drulis-Kawa, Z.; de Paula, S.O.; et al. Isolation and Characterization of the Acadevirus Members BigMira and MidiMira Infecting a Highly Pathogenic Proteus Mirabilis Strain. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2141.

- Coker, C.; Poore, C.A.; Li, X.; Mobley, H.L.T. Pathogenesis of Proteus Mirabilis Urinary Tract Infection. Microbes Infect 2000, 2, 1497–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Tian, Y.; Li, X. Unveiling the Hidden Arsenal: New Insights into Proteus Mirabilis Virulence in UTIs. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2024, 14, 1465460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Hoedt, E.C.; Liu, Q.; Berendsen, E.; Teh, J.J.; Hamilton, A.; O’ Brien, A.W.; Ching, J.Y.L.; Wei, H.; Yang, K.; et al. Elucidation of Proteus Mirabilis as a Key Bacterium in Crohn’s Disease Inflammation. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Li, P.; Qiu, K.; Liao, Y.; Chen, X.; Xuan, J.; Wang, F.; Ma, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, M. Proteus Mirabilis Exacerbates Ulcerative Colitis by Inhibiting Mucin Production. Front Microbiol 2025, 16, 1556953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Pérez, A.; Corbera, J.A.; González-Martín, M.; Tejedor-Junco, M.T. Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of Bacteria Isolated from Chicks of Canarian Egyptian Vultures (Neophron Percnopterus Majorensis): A “One Health” Problem? Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 2023, 92, 101925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Liu, S.; Bano, S.; Xia, X.; Baloch, Z. First Report of Complete Genome Analysis of Multiple Drug Resistance Proteus Mirabilis KUST-1312 Isolate from Migratory Birds in China: A Public Health Threat. Transbound Emerg Dis 2024, 2024, 8102506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergunay, K.; Mutinda, M.; Bourke, B.; Justi, S.A.; Caicedo-Quiroga, L.; Kamau, J.; Mutura, S.; Akunda, I.K.; Cook, E.; Gakuya, F.; et al. Metagenomic Investigation of Ticks From Kenyan Wildlife Reveals Diverse Microbial Pathogens and New Country Pathogen Records. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 932224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zheng, W.; Huang, H.; Liu, S.; Yang, M.; Yan, X.; Li, Y.; Yue, C.; Hou, R.; Zhang, D. Establishment and application of multiplex PCR detection method for Proteus mirabilis,Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli from giant panda. Chin J Prev Vet Med 2023, 45, 598–603. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D.; Su, X.; Yue, C.; E.Ayala, J.; Yan, X.; Hou, R.; Li, L.; Xie, Y.; et al. Mortality Analysis of Captive Red Panda Cubs within Chengdu, China. BMC Vet Res 2022, 18, 68.

- Lv, P.; Hao, G.; Cao, Y.; Cui, L.; Wang, G.; Sun, S. Detection of Carbapenem Resistance of Proteus Mirabilis Strains Isolated from Foxes, Raccoons and Minks in China. Biology (Basel) 2022, 11, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; He, Z.; Huang, F. Multidrug-Resistant Proteus Mirabilis Isolated from Newly Weaned Infant Rhesus Monkeys and Ferrets. Jundishapur J Microbiol 2015, 8, e16822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Wang, W.; Tong, P.; Liu, C.; Jia, J.; Lu, C.; Han, Y.; Sun, X.; Kuang, D.; Li, N.; et al. Comparative Genomic Analysis of Proteus Spp. Isolated from Tree Shrews Indicated Unexpectedly High Genetic Diversity. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0229125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinnam, B.K.; Nelapati, S.; Tumati, S.R.; Bobbadi, S.; Peddada, V.C.; Bodempudi, B. Detection of β-Lactamase-Producing Proteus Mirabilis Strains of Animal Origin in Andhra Pradesh, India and Their Genetic Diversity. J Food Prot 2021, 84, 1374–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Zhou, J.; Huang, H.; Wang, W.; Xiao, Y.; Tang, B.; Liu, H.; Xu, C.; Xiao, X. Genomic Investigation of Proteus Mirabilis Isolates Recovered From Pig Farms in Zhejiang Province, China. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 952982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costinar, L.; Herman, V.; Pitoiu, E.; Iancu, I.; Degi, J.; Hulea, A.; Pascu, C. Boar Semen Contamination: Identification of Gram-Negative Bacteria and Antimicrobial Resistance Profile. Animals 2022, 12, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Peng, C.; Zhang, G.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Liu, M.; Wang, F. Prevalence and Characteristics of Multidrug-Resistant Proteus Mirabilis from Broiler Farms in Shandong Province, China. Poult Sci 2022, 101, 101710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramatla, T.; Ramaili, T.; Lekota, K.; Mileng, K.; Ndou, R.; Mphuthi, M.; Khasapane, N.; Syakalima, M.; Thekisoe, O. Antibiotic Resistance and Virulence Profiles of Proteus Mirabilis Isolated from Broiler Chickens at Abattoir in South Africa. Vet Med Sci 2024, 10, e1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Q.; Ma, D.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, H.; Yuan, J.; Li, X.; Wang, X. Isolation, identification and characteristics analysis of Proteus mirabilis from swine. China Anim Husb Vet Med 2021, 48, 1804–1815. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Wen, S.; Zhao, L.; Xia, Q.; Pan, Y.; Liu, H.; Wei, C.; Chen, H.; Ge, J.; Wang, H. Association among Biofilm Formation, Virulence Gene Expression, and Antibiotic Resistance in Proteus Mirabilis Isolates from Diarrhetic Animals in Northeast China. BMC Vet Res 2020, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algammal, A.M.; Hashem, H.R.; Alfifi, K.J.; Hetta, H.F.; Sheraba, N.S.; Ramadan, H.; El-Tarabili, R.M. AtpD Gene Sequencing, Multidrug Resistance Traits, Virulence-Determinants, and Antimicrobial Resistance Genes of Emerging XDR and MDR-Proteus Mirabilis. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 9476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, C.; Belas, A.; Menezes, J.; da Silva, J.M.; Cavaco-Silva, P.; Trigueiro, G.; Gama, L.T.; Pomba, C. Human and Companion Animal Proteus Mirabilis Sharing. Microbiol Res (Pavia) 2022, 13, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Dong, Z.; Ai, S.; Chen, S.; Dong, M.; Li, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhong, Z.; Ma, X.; et al. Virulence-Related Factors and Antimicrobial Resistance in Proteus Mirabilis Isolated from Domestic and Stray Dogs. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1141418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathirana, H.N.K.S.; De Silva, B.C.J.; Wimalasena, S.H.M.P.; Hossain, S.; Heo, G.J. Comparison of Virulence Genes in Proteus Species Isolated from Human and Pet Turtle. Iran. J. Vet. Res. 2018, 68, 72–76+154. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca, J.D.; Mavrides, D.E.; Graham, P.A.; McHugh, T.D. Results of Urinary Bacterial Cultures and Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing of Dogs and Cats in the UK. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2021, 62, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyaert, H.; Morrissey, I.; De Jong, A.; El Garch, F.; Klein, U.; Ludwig, C.; Thiry, J.; Youala, M. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Monitoring of Bacterial Pathogens Isolated from Urinary Tract Infections in Dogs and Cats across Europe: ComPath Results. Microb. Drug Resist. 2017, 23, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amphaiphan, C.; Yano, T.; Som-in, M.; Kungwong, P.; Wongsawan, K.; Pusoonthornthum, R.; Salman, M.D.; Tangtrongsup, S. Antimicrobial Drug Resistance Profile of Isolated Bacteria in Dogs and Cats with Urologic Problems at Chiang Mai University Veterinary Teaching Hospital, Thailand (2012–2016). Zoonoses Public Health 2021, 68, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Kong, L.; Dong, W.; Liu, S.; Gao, Y.; Ma, H.; Luan, W. Isolation identification and biological characteristics of Proteus mirabilis of canine. Heilongjiang Anim Sci Vet Med 2020, 68, 72–76+154. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, Z. Isolation,Identifi cation and Drug Susceptibility of Proteus mirabilis Isolates from Dogs in Weifang City. Chin. J. Anim. Infect. Dis. 2022, 30, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Sanches, M.S.; Rodrigues da Silva, C.; Silva, L.C.; Montini, V.H.; Lopes Barboza, M.G.; Migliorini Guidone, G.H.; Dias de Oliva, B.H.; Nishio, E.K.; Faccin Galhardi, L.C.; Vespero, E.C.; et al. Proteus Mirabilis from Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infections (UTI-CA) Shares Genetic Similarity and Virulence Factors with Isolates from Chicken, Beef and Pork Meat. Microb Pathog 2021, 158, 105098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edris, S.N.; Hamad, A.; Awad, D.A.B.; Sabeq, I.I. Prevalence, Antibiotic Resistance Patterns, and Biofilm Formation Ability of Enterobacterales Recovered from Food of Animal Origin in Egypt. Vet World 2023, 16, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Joossens, M.; Van den Abeele, A.M.; Kerkhof, P.J.; Houf, K. Isolation, Characterization and Antibiotic Resistance of Proteus Mirabilis from Belgian Broiler Carcasses at Retail and Human Stool. Food Microbiol 2021, 96, 103724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, H.; Liu, N.; Liu, Y.; Du, J. Quantitative PCR detection and antimicrobial resistance analysis of Proteus mirabilis in fresh chicken meat. Farm Prod Process 2022, 24, 63–67+71. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.Q.; Han, Y.Y.; Zhou, L.; Peng, W.Q.; Mao, L.Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, T.J.; Wang, H.N.; Lei, C.W. Contamination of Proteus Mirabilis Harbouring Various Clinically Important Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Retail Meat and Aquatic Products from Food Markets in China. Front Microbiol 2022, 13, 1086800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, C.; Hu, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, C.; Bi, S. Prevalence and Antibiotics Resistance of Proteus Mirabilis in Raw Meat. Sci. Technol. Food Ind. 2023, 44, 257–263. [Google Scholar]

- Zaher, A.H.; Kabadaia, M.M.; Hammad, K.M.; Mekky, A.E.; Salem, S.S. Forensic Flies as Carries of Pathogenic Bacteria Associated with a Pig Carcass in Egypt. Al-Azhar Bulletin of Science 2023, 34, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, C.; Belas, A.; Aboim, C.; Trigueiro, G.; Cavaco-Silva, P.; Gama, L.T.; Pomba, C. Clonal Relatedness of Proteus Mirabilis Strains Causing Urinary Tract Infections in Companion Animals and Humans. Vet Microbiol 2019, 228, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanches, M.S.; Silva, L.C.; Silva, C.R. da; Montini, V.H.; Oliva, B.H.D. de; Guidone, G.H.M.; Nogueira, M.C.L.; Menck-Costa, M.F.; Kobayashi, R.K.T.; Vespero, E.C.; et al. Prevalence of Antimicrobial Resistance and Clonal Relationship in ESBL/AmpC-Producing Proteus Mirabilis Isolated from Meat Products and Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infection (UTI-CA) in Southern Brazil. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, T.; Linhares, I.; Ferreira, R.; Neves, J.; Almeida, A. Frequency and Antibiotic Resistance of Bacteria Implicated in Community Urinary Tract Infections in North Aveiro between 2011 and 2014. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018, 24, 493–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, J.N.; Pearson, M.M. Proteus Mirabilis and Urinary Tract Infections. Microbiol Spectr 2017, 3, 383–433. [Google Scholar]

- Chakkour, M.; Hammoud, Z.; Farhat, S.; El Roz, A.; Ezzeddine, Z.; Ghssein, G. Overview of Proteus Mirabilis Pathogenicity and Virulence. Insights into the Role of Metals. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1383618. [Google Scholar]

- Hafiz, T.A.; Alghamdi, G.S.; Alkudmani, Z.S.; Alyami, A.S.; Almazyed, A.; Alhumaidan, O.S.; Mubaraki, M.A.; Alotaibi, F.E. Multidrug-Resistant Proteus Mirabilis Infections and Clinical Outcome at Tertiary Hospital in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Infect Drug Resist 2024, 17, 571–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Ruan, H.; Yang, H.; Mu, H.; Jin, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ge, Y.; Zheng, J. Study on identification, biological characteristic of Proteus mirabilis isolated from canine and its ability to induced calculus formation. Heilongjiang Anim Sci Vet Med 2021, 68, 80–84+163. [Google Scholar]

- Herout, R.; Khoddami, S.; Moskalev, I.; Reicherz, A.; Chew, B.H.; Armbruster, C.E.; Lange, D. Role of Bacterial Surface Components in the Pathogenicity of Proteus Mirabilis in a Murine Model of Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection. Pathogens 2023, 12, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Shi, X.; Bai, F.; He, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Wan, Y.; Lin, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, Q.; et al. Characterization of a Novel Diarrheagenic Strain of Proteus Mirabilis Associated With Food Poisoning in China. Front Microbiol 2019, 10, 2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yu, J.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, Z.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, Y.; Song, H. An Outbreak of Proteus Mirabilis Food Poisoning Associated with Eating Stewed Pork Balls in Brown Sauce, Beijing. Food Control 2010, 21, 302–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Li, X.; Wu, X.; Ni, K. Etiological characteristics and clinical features analysis of 486 pediatric diarrhea cases caused by Proteus mirabilis. Chin J Rural Med Pharm 2021, 28, 52–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kitamoto, S.; Nagao-Kitamoto, H.; Jiao, Y.; Gillilland, M.G.; Hayashi, A.; Imai, J.; Sugihara, K.; Miyoshi, M.; Brazil, J.C.; Kuffa, P.; et al. The Intermucosal Connection between the Mouth and Gut in Commensal Pathobiont-Driven Colitis. Cell 2020, 182, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Q.; Zhai, S.; Lv, Y.; Wen, X.; Wu, G.; Huo, W.; Tu, D.; Wei, W.; Jia, C.; Zhou, X. Isolation, Identification and Drug Resistance of Proteus Mirabilis from Bamboo Rats. Chin J Anim Infect Dis 2021, 29, 94–97. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Wei, L.; Zhu, X.; Liu,Y. Isolation, identification and pathogenicity analysis of Proteus mirabilis from rabbits. Chin J Prevent Vet Med 2024, 46, 32–38.

- Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Jin, H.; Hou, S.; Feng, J. Isolation,Identification and Drug Resistance Analysis of Rabbit Proteus mirabilis. China Anim Husb Vet Med 2019, 46, 1509–1515. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, G.; Yang, G.; Jiang, X.; Zhang,S.; Wang, Y.; Hr, J.; Tao D. Isolation and Identification of Proteus Mirabilis from Diarrhea Lamb in Xinjiang and Its Pathogenicity in Mice. J Anim Sci Vet Med 2022, 54, 91–95.

- Mistry, R.D.; Scott, H.F.; Alpern, E.R.; Zaoutis, T.E. Prevalence of Proteus Mirabilis in Skin Abscesses of the Axilla. Journal of Pediatrics 2010, 156, 850–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; He, C.; Li, C.; Zeng, W.; Ma, L.; Liu, J.; Bai, A.; Yang, L.; Wu, J. Isolation and Identifi cation of Biofilm-forming Protrus mirabils from Diseased Pigs and Its Pathogenicity. Chin. J. Anim. Infect. Dis. 2023, 31, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; ma, L.; Qin, S.; Chen, Y.; Song, R.; Sun, Q.; Qin, S.; Liu, J.; Chen,F.; Wu, J. Isolation,identification and biological characteristics of swine-sourced Proteus mirabilis producing AmpC enzyme. Anim Husb Vet Med 2023, 55, 46–52.

- Li, N.; Wang, B.; Shu, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Huang, T.; Tang, D.; Wu,X. Isolation and identification of swine-sourced Proteus mirabilis, and detection of its drug resistance and virulence genes. J Anim Sci Vet Med 2021, 53, 89–94.

- Sanches, M.S.; Baptista, A.A.S.; de Souza, M.; Menck-Costa, M.F.; Justino, L.; Nishio, E.K.; Oba, A.; Bracarense, A.P.F.R.L.; Rocha, S.P.D. Proteus Mirabilis Causing Cellulitis in Broiler Chickens. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2020, 51, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Javan, A.J.; Shokrpoor, S.; Beidokhtinezhad, M.; Tamai, I.A. Pyoderma Caused by Proteus Mirabilis in Sheep. Vet Med Sci 2022, 8, 2562–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najd Ghahremani, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Shokrpoor, S.; Ashrafi Tamai, I. Pericarditis Caused by Proteus Mirabilis in Sheep. Vet Med Sci 2023, 9, 1737–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacristán, C.; Costa-Silva, S.; Reisfeld, L.; Navas-Suárez, P.E.; Ewbank, A.C.; Duarte-Benvenuto, A.; Coelho Couto de Azevedo Fernandes, N.; Albergaria Ressio, R.; Antonelli, M.; Rocha Lorenço, J.; et al. Novel Alphaherpesvirus in a Wild South American Sea Lion (Otaria Byronia) with Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2021, 52, 2489–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanayak, S.; Kumar, P.R.; Sahoo, M.K.; Paul, A.; Sahoo, P.K. First Field-Based Evidence of Association of Proteus Mirabilis Causing Large Scale Mortality in Indian Major Carp Farming. Aquaculture 2018, 495, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhou, H.; Chen, G.; Dong, N. Isolation of Four Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Species from a Single Fly. Animal Diseases 2024, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odetoyin, B.; Adeola, ; Babatunde; Olaniran, Olarinde. Frequency and Antimicrobial Resistance Patterns of Bacterial Species Isolated from the Body Surface of the Housefly (Musca Domestica) in Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria. J. Arthropod-Borne Dis. 2020, 14, 88.

- El-Tarabili, R.M.; Ahmed, E.M.; Alharbi, N.K.; Alharbi, M.A.; AlRokban, A.H.; Naguib, D.; Alhag, S.K.; El Feky, T.M.; Ahmed, A.E.; Mahmoud, A.E. Prevalence, Antibiotic Profile, Virulence Determinants, ESBLs, and Non-β-Lactam Encoding Genes of MDR Proteus Spp. Isolated from Infected Dogs. Front Genet 2022, 13, 952689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.A.; Guo, C.H.; Yang, T.Y.; Li, F.Y.; Song, F.J.; Liu, B.T. Whole-Genome Analysis of BlaNDM-Bearing Proteus Mirabilis Isolates and Mcr-1-Positive Escherichia Coli Isolates Carrying BlaNDM from the Same Fresh Vegetables in China. Foods 2023, 12, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Host | Region (Year) | Isolation Rate | Virulence Gene | Reference |

| Wildlife | Migratory Birds | China (2024) | 2.7% (1/37) | NA | [18] |

| Canarian Egyptian Vultures | Spain (2022) | 36.2% (17/47) | NA | [17] | |

| Tick from wildlife | Kenya (2022) | 48.5% (17/35) | NA | [19] | |

| Panda | China (2023) | 30% (30/100) | NA | [20] | |

| Red panda | China (2022) | 9.38% (3/32) | NA | [21] | |

| Fox | China (2022) | 41.51% (22/53) | ureC, zapA, pmfA, atfA, mrpA, atfC , hmpA, rsmA, rsbA, ucaA | [22] | |

| Raccoon | China (2022) | 33.96% (18/53) | ureC, zapA, pmfA, atfA, mrpA, atfC , hmpA, rsmA, rsbA, ucaA | [22] | |

| Ferrets | China (2015) | 30% (4/12) | NA | [23] | |

| Mink | China (2020, 2022) | 24.53% (13/53)-28.7% (62/216) | ureC, zapA, pmfA, atfA, mrpA, atfC , hmpA, rsmA, rsbA, ucaA, FliL | [22,31] | |

| Rhesus Monkeys | China (2015) | 9.5% (7/74) | NA | [23] | |

| Tree shrews | China (2020) | 94.4% (34/36) | NA | [24] | |

| Farm animals | Pig | China (2021, 2022), Rome (2021), India (2021) | 5.55% (30/541)-21.43% (21/98) | ureC, hpmA, zapA, pmfA, rsbA, ucaA, mrpA, atfA, ireA , ptA | [25,26,27,30] |

| Broiler | China (2020, 2022), India (2021), South Africa (2024) | 5.4% (26/480)-22.5% (18/80) | ureC, rsmA, hmpA, FliL , ireA, ptA , zapA, ucaA, pmfA, atfA , mrpA, hlyA , hpmA | [25,28,29,31] | |

| Duck | Egypt (2021) | 14.6% (35/240) | atpD, ureC, rsbA , zapA | [32] | |

| Cattle | China (2020), India (2021) | 23.26% (20/86)-33.33% (20/60) | ureC, zapA, rsmA, hmpA, mrpA, atfA, pmfA, FliL, ucaA | [25,31] | |

| Sheep | India (2021) | 31.91% (15/47) | NA | [25] | |

| Companion animals | Dog | China (2020, 2022, 2023), Egypt (2022), UK (2021), Thailand (2019), European countries (2016), Portugal (2018, 2021) | 11.0% (48/437)-87.85% (94/107) | ureC, FliL, ireA, zapA, ptA, hpmA, hpmB, pmfA, rsbA, mrpA, ucaA, rsmA, atfA | [31,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,48,75] |

| Cat | UK (2021), Thailand (2020), Europe (2017), Portugal (2019, 2022) | 0-16.7% (4/24) | hmpA/hmpB, mrpA, pmfA, ucaA | [33,36,37,38,48] | |

| Pet turtle | South Korea (2018) | 28.8% (15/52) | ureC, rsbA, zapA , mrpA | [35] | |

| Animal-derived foods | Pork | China (2022, 2023), Brazil (2021), India (2021) | 14.38% (23/160)- 65.61% (149/227) | mrpA, pmfA, ucaA, atfA, hpmA, zapA, ptA, ireA | [25,41,45,46] |

| Beef | Brazil (2021) | 27.8% (100/360)- 32.73% (17/55) | mrpA, pmfA, ucaA, atfA, hpmA, zapA, ptA, ireA | [25,41] | |

| Mutton | India (2021) | 25.51% (25/98) | NA | [25] | |

| Chicken | China (2022, 2023), Belgium (2020), Brazil (2021), India (2021), Egypt (2023) | 1.51% (1/66)-100% (200/200) | mrpA, pmfA, ucaA, atfA, hpmA, zapA, ptA, ireA | [25,41,42,43,45,46] | |

| Duck meat | China (2023) | 67.9% (84/124) | NA | [46] | |

| Milk/Dairy Products | India (2021), Egypt (2023) | 3.45% (2/58)-22.11% (21/95) | NA | [25,42] | |

| Other source | Aquatic products | China (2022) | 7.61% (7/92) | NA | [45] |

| Vegetables | China (2023) | 62.5% (5/8) | hpmA, mrpA, ptA, ireA, zapA, pmfA , atfA | [76] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).