1. Introduction

The Internet of Things (IoT) has the potential to revolutionize sectors such as precision agriculture and environmental monitoring in low-infrastructure regions [

1]. However, its effective implementation in rural areas of developing countries depends on technologies that combine

long range ,

low power consumption and

affordable cost — core characteristics of LPWAN ( Low Power Wide Area Networks) [

2], as opposed to

short-range networks such as Bluetooth, NFC, Wi-Fi/802.11, Z- Wave , Zigbee [

3], although they are also low energy [

4]consumption , [

5]. To further improve energy efficiency, a variant called BLE (Bluetooth Low Energy) was created in 2010, considered the best option for the new generation of IoT [

6]. Among the LPWAN protocols, LoRaWAN stands out for its use of unlicensed spectrum, support for asynchronous communication, and minimal infrastructure requirements [

7,

8], ideal for the agricultural areas of Mozambique. It

s operating frequencies are 433, 868 and 915 MHz, which operate in ISM (Industrial, Scientific and Medical) bands, internationally reserved for unlicensed use [

9].

According to the regional frequency allocation plan [

10], in this study, the 868 MHz band was selected, as it is allocated by CRASA (Communications Regulators ' Association of Southern Africa) [

11], as an organization of SADC (Southern Africa Development Community), that promotes common regional policies for spectrum use.

Studies highlight the performance and limitations of LoRa in different contexts:

Mining environments: A study conducted by Musonda, analyzed the challenges and design requirements to ensure the reliability of LoRaWAN in mining environments, characterized by underground structures and electromagnetic interference. The results highlighted the need for specific adjustments in the network configuration to maintain the integrity of transmitted data [

12].

Varied terrain: Research indicates that terrain topography significantly influences LoRa communication, potentially resulting in a reduction of up to 58.63% in signal reliability in areas with rugged terrain [

13].

Urban environments: Studies in densely populated urban environments have shown that despite interference, LoRaWAN can maintain reliability of up to 90.23% with appropriate configurations [

14].

Other study reinforces its effectiveness in remote environments, with ranges of up to 15 km in ideal conditions [

15], while another one, warn of

trade-offs between latency and capacity in large-scale deployments — a relevant challenge for agricultural applications that require periodic transmissions, but not in real time [

16].

In Mozambique, where

73% of the rural population does not have access to the internet [

17] and electrical coverage is non-existent in vast areas [

18], commercial solutions such as Starlink [

19] or NB-IoT [

20] are unviable due to

prohibitive costs [

21],

continuous energy dependence [

22] and centralized infrastructure. This reality reflects a broader scenario described by UN-HABITAT [

23]: Rural areas in Africa often lack not only connectivity, but also basic sanitation and energy, perpetuating cycles of digital exclusion and inequality. As highlighted by Rosário [

24], agribusiness in Mozambique is hindered by investment concentration in large-scale producers, leaving small farmers marginalized from digital technologies.

In this context, LoRaWAN emerges as a viable alternative, but its reliability in

rugged terrains — typical of agricultural areas — still lacks local empirical validation [

25]. Previous research has focused on urban or mining environments, neglecting critical rural conditions: topographic variations, dense vegetation, and moderate distances (1–5 km) with natural obstacles.

This gap is addressed through a field trial in an agricultural area of Mozambique, evaluating the impact of distance and relative altitude on metrics such as: RSSI (Received Signal Strength Indicator), SNR (Signal-to-Noise Ratio), PDR (Packet Delivery Rate) and Autonomy energetic.

Using low-cost equipment (Arduino Uno + LoRa Shield) and simulations of real conditions — without GPS, mobile network or continuous power — our method replicates the constraints faced by smallholder farmers. Additionally, we tested practical strategies such as installing gateways on natural elevations, an approach aligned with the recommendations of the studies referenced above, but still little explored in African contexts.

The results demonstrate that, even with limited hardware, LoRaWAN achieved acceptable delivery rates over distances up to 1 km with autonomous operation.

This research offers:

Empirical evidence for digital inclusion policies;

Guidelines for implementation in similar contexts;

Solutions aligned with local needs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Operational Context

The study was conducted in a riverine agricultural area in Nampula province, northern Mozambique. The area is characterized by small communal farmland, lack of electricity, internet and mobile coverage. The location was chosen because it is representative of the challenges faced by rural communities in Africa, providing an ideal setting to test the viability of LPWAN solutions.

The topography features modest elevation variations, with small natural hills. The gateway was installed at one of these natural elevations to optimize signal propagation. The test route featured restricted access, sparse vegetation, and unpaved terrain.

2.2. Network Equipment and Architecture

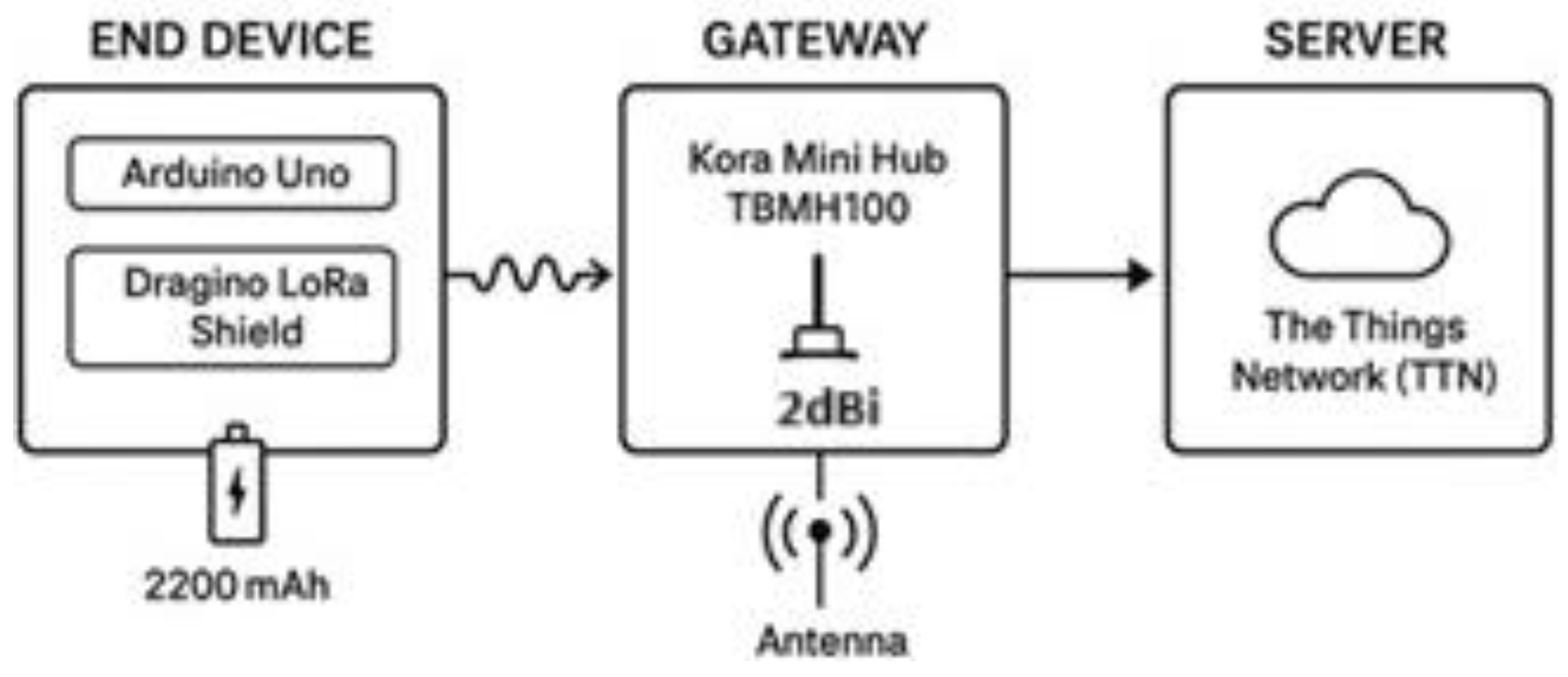

The system was composed of:

A terminal node with Arduino Uno + LoRa Shield (Dragino Kit);

A 2 dBi antenna;

A 2,200 mAh power bank;

A gateway connected to The Things Network (TTN);

Communication configured via OTAA (Over-The-Air Activation).

The Dragino kit with Arduino Uno and LoRa Shield was selected due to its affordable cost and compatibility with LPWAN protocols, features that make it a viable choice for IoT prototyping [

26]. In addition, it operates in the ISM frequency band (also allocated to Mozambique) and offers flexible spreading factor configurations (SF7–SF12), essential for balancing transmission rate and range in urban or rural environments [

27].

The general architecture of the communication system used in the test is illustrated in

Figure 1, as a Diagram representing the data flow between the terminal device (Arduino Uno + Dragino LoRa Shield powered by a 2200 mAh battery), the gateway (Kora Mini Hub TBMH100 with 2 dBi antenna) and The Things Network (TTN) server.

Firmware development was carried out in the Arduino IDE, employing the LMIC library, widely used in LoRaWAN applications. The system did not have GPS, and geolocation was performed manually based on satellite images (Google Earth) and direct observation of physical landmarks.

Both devices operated in the 868 MHz band, which is compatible with the allocation plan defined by The Things Network for countries in the SADC region. Mozambique is part of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and participates in regional spectrum harmonization and digital integration commitments promoted by organizations such as CRASA and recognized by the World Bank as fundamental for the expansion of emerging technologies , and in accordance with TTN's global allocation plan, which defines [

28]LoRaWAN bands by country/region according to ISM standards [

29].

2.3. Experimental Procedure and Data Collection

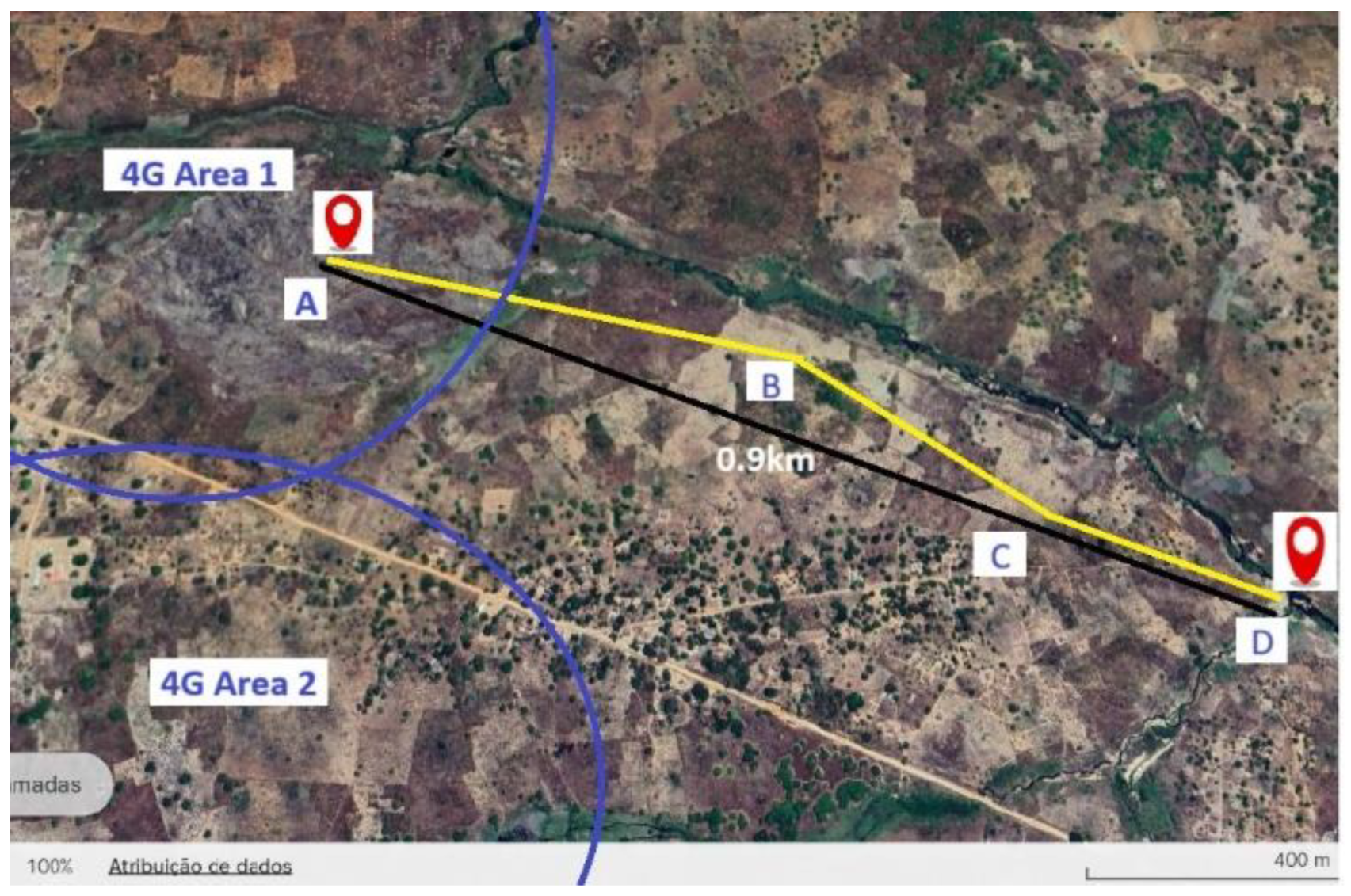

During the tests, four measurement points (A, B, C and D) were defined, positioned along approximately 1 km, with variations in altitude and distance in relation to the gateway. The gateway remained fixed at point A (altitude 334 m), with the others positioned up to 30 meters below.

In each point:

The terminal node was manually restarted to force packet transmission;

The data was not monitored in real time due to lack of internet on the route;

The packages were later verified on the TTN platform;

RSSI, SNR, PDR and operating time on a single battery charge were recorded.

The

Map of the test area with georeferenced four measurement points (A, B, C and D) marked along the experimental route, is shown on

Figure 2, it includes the indication of the 4G coverage zones identified in the region

before the installation of the LoRaWAN network. The yellow line represents the physical route taken on foot and the black line represents the direct distance between the ends.

The georeferencing of the points (coordinates) was done based on expeditious methods, combining direct observation on the ground with the analysis of satellite images via Google Earth, which also contributes to a comprehensive understanding of the topographic and vegetation characteristics of the study area.

Point A: 15°14'01"S, 39°25'10"E;

Point B: 15°14'05"S, 39°25'26"E;

Point C: 15°14'07"S, 39°25'28"E;

Point D: 15°14'08"S, 39°25'31"E.

3. Results

The collected data demonstrates the direct impact of distance and altitude difference between devices on the quality of LoRaWAN communication. Four georeferenced points (A, B, C and D) were analysed, along approximately 1 km, starting from the highest point (gateway) to the agricultural plain.

The Consolidated performance at the four points tested and main parameters analysed are indicated in

Table 1. The energy performance of the end node was also evaluated; these results are discussed separately from the table.

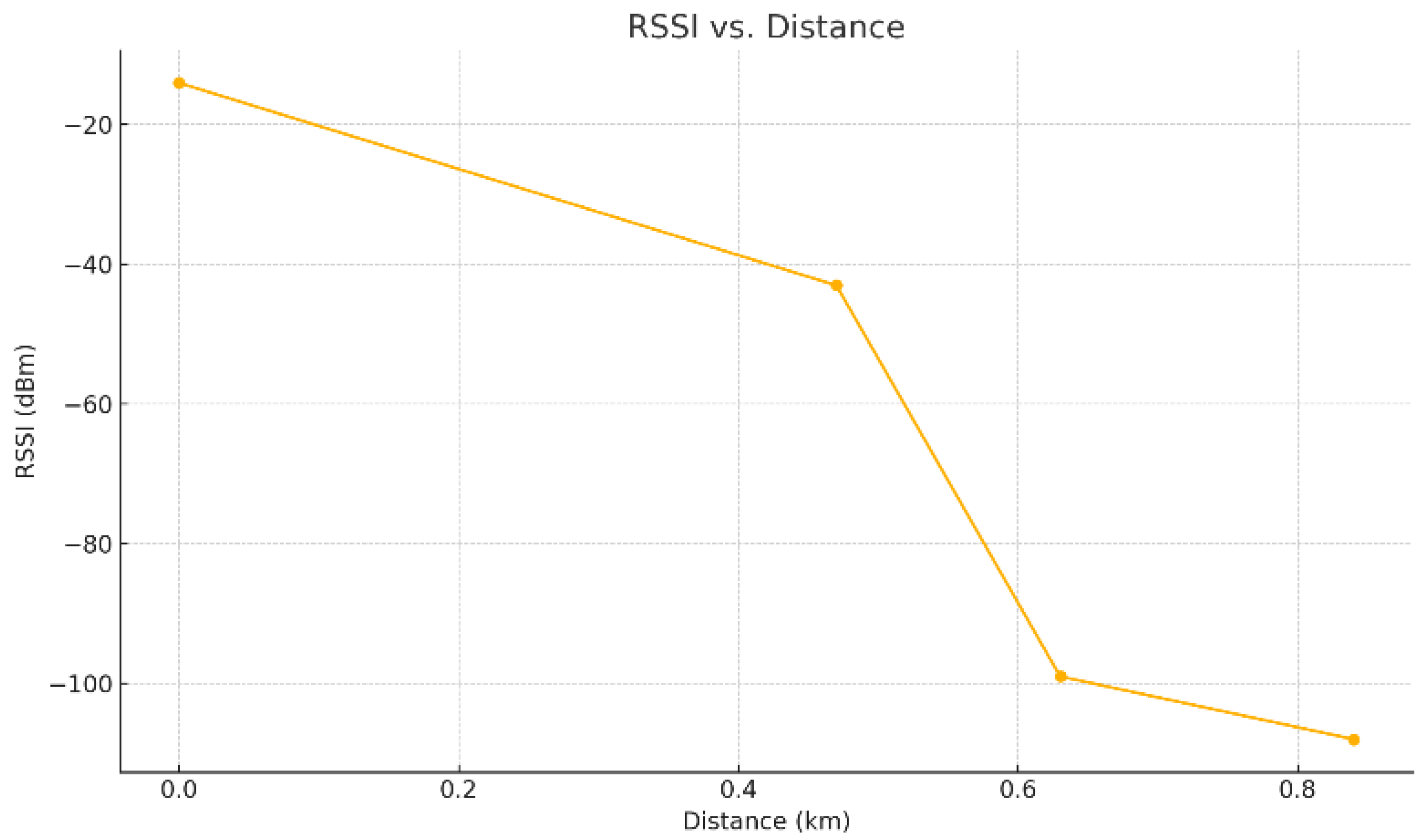

3.1. RSSI

The RSSI indicator showed a decline as distance increased, and altitude decreased. Point A (100 m, altitude 334 m) showed the best value: –14 dBm. Point D (1,000 m, altitude 298 m), located 30 meters below the gateway, recorded the worst value: –108 dBm.

Figure 3, shows the RSSI Average (in dBm) measured at the four points. The value reduces proportionally with the distance and the loss of line of sight with the gateway.

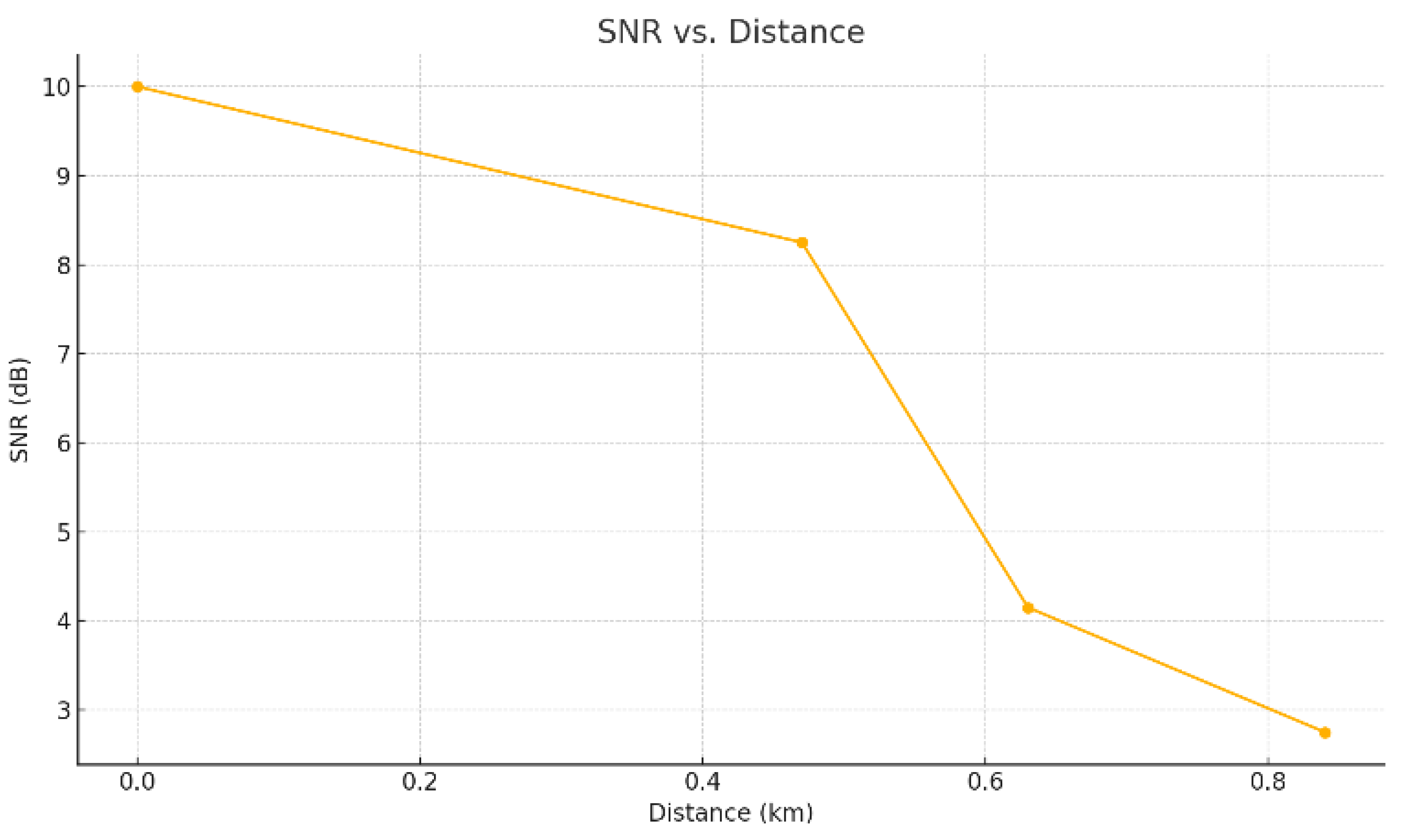

3.2. SNR

The SNR showed similar behavior to the RSSI. The best value was observed at point A (10 dB), while the lowest was at point D (2.75 dB).

Figure 4, demonstrate the deterioration of the signal quality in scenarios with unevenness and greater obstruction of the communication line.

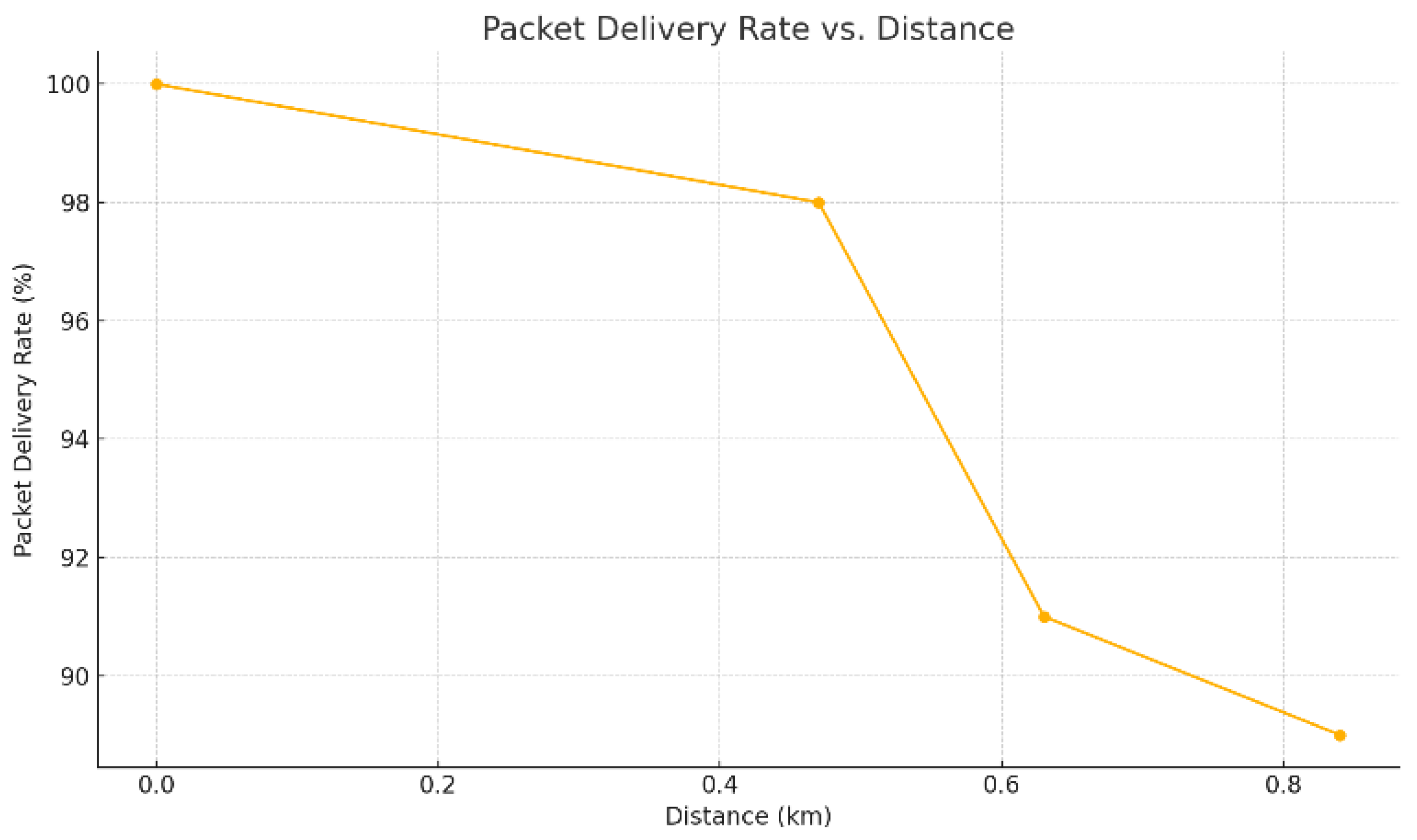

3.3. PDR

Even with signal degradation, the PDR remained high, as illustrated on

Figure 5. Point A had 100%, point B 97%, point C 91% and point D 89%. This robustness confirms the potential of LoRaWAN in harsh rural environments, as also observed in other studies mentioned. A notable drop in PDR was observed with increasing distance, particularly beyond 0.5 km from the gateway.

3.4. Energy Autonomy

The terminal node operated continuously powered by a 2200mAh power bank, during the 6 hours of testing. After this period, the device was kept on for more than 24 hours with a full battery charge. This autonomy reinforces the low energy consumption characteristic of LoRaWAN and its suitability for environments without access to the electrical grid, as observed.

Figure 6, shows LoRa device with 2 dBi antenna, connected on the power bank.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Relative Altitude and Distance

It was observed that, even over short distances (less than 1 km), the difference in altitude had a strong impact on performance. Points C and D, located 30 meters below the gateway, presented the worst indicators. This reinforces the importance of considering the relief when installing gateways, a strategy already recommended by Musonda in the introduction.

Installing the gateway on naturally elevated areas (mounts, hills, rooftops, etc.) increases the effective coverage radius, making it a practical and cost-effective solution for rural areas. This approach has been successfully applied in agricultural and environmental monitoring projects in riverine areas [

30].

4.2. Comparison with Other Technologies

It is evident that short-range technologies fall short of meeting the objectives of this project, for example, NFC, which is relevant in urban contexts and short-range, does not meet the need for broad coverage in remote areas [

31]. Although, NB-IoT, Wi-SUN and Starlink are long-range connectivity technologies, they have limitations when applied in rural African contexts:

While Starlink is promising in remote urban areas, it does not meet the operational and economic conditions of smallholder farmers in Mozambique. Other technologies have limited range or rely on cellular/commercial coverage. LoRa stands out for:

Range greater than 1 km;

Operation in unlicensed ISM bands;

Low consumption energetic;

Cost reduced and autonomy extended.

Therefore, for timely transmission of environmental or agricultural data, LoRa is the most efficient option, which validates the choice of LoRaWAN for this study.

4.3. Implications for Projects in Rural Areas

The observed energy behavior is in agreement with the literature on LoRa device efficiency. Based on the field test and intermittent transmission profile, an autonomy of at least 30 hours is estimated with a 2200 mAh power bank, being even greater with solar panels.

This performance reinforces the use of LoRa as an ideal alternative for remote rural environments, with:

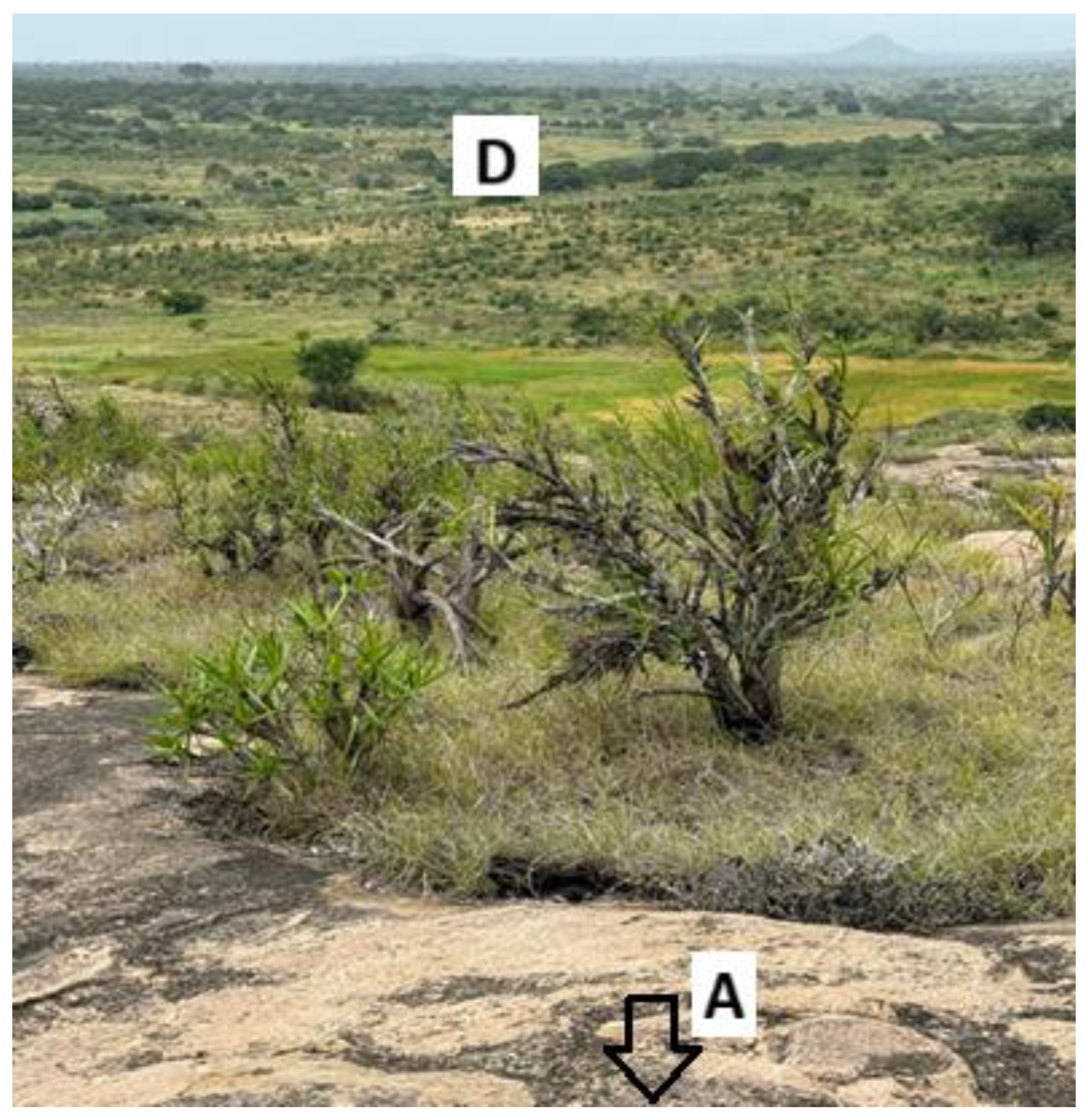

And the evidence confirm that the best performances were obtained at points with elevation close to that of the gateway reinforces the need to consider the relief when installing networks. In agricultural regions located in lowlands (such as areas near rivers), priority should be given to installing gateways in higher areas, with direct line of sight, even if improvised. The

Figure 7, shows an image captured from the top of a natural elevation, (point A). The cultivated field is what can be seen just after the lowest level of the hill extending to the horizon line, the gateway and the last end node test point are indicated on image. the visual line and Geographical illustrate how the natural elevation can be used as a reception tower to extend the coverage of the LoRaWAN network.

4.4. Limitations and Prospects for Improvement

The execution of the tests revealed relevant operational and technological limitations, especially with regard to real-time monitoring and automation of the packet transmission process.

Among the main constraints observed, the following stand out:

The absence of a mobile network along the route prevented direct monitoring of data on the TTN during field tests:

Impossibility of real-time monitoring (no mobile network);

Absence of GPS for automatic location marking;

The need to manually restart the microcontroller to send packets at each point, making the process more time-consuming and subject to human error;

The usage of a 2 dBi antenna, which significantly limited the range. Despite the attempt to explore a route of approximately 3 km (which was traversed on foot), effective connectivity was recorded only at four points, within a radius of approximately 1 km (a third of the route) from the gateway.

These limitations partially compromise the scope and accuracy of the study but also provide clear elements for methodological evolution in future investigations.

As a way to mitigate these challenges and increase data quality and reliability, the following improvements are proposed for future work:

Formation of a minimum technical team of three researchers, with one assigned to the gateway to monitor local connectivity. Communication between team members can be done via portable radios (walkie-talkies), allowing immediate confirmation of packet reception before progressing to the next point;

Optimization of the microcontroller firmware, incorporating automatic transmissions at scheduled intervals. This would eliminate the need for manual reboots and allow for a more continuous data flow. With this model, signal loss could be identified in real time by the base operator, facilitating rapid diagnostics and corrections;

Hardware update for modules with integrated GPS, such as shields LoRa GPS, enabling the use of platforms such as TTN Mapper for the automatic collection of georeferenced data with greater precision;

Replacement of the low-gain antenna (2 dBi) with higher-power models or with better positioning (in height), to significantly expand coverage and enable larger-scale studies in agricultural areas with varied topography.

These improvements are technically feasible and compatible with the project objectives, allowing future implementations to obtain more complete, automated and expanded coverage data, consistent with the requirements of real agricultural environments. Future work consists of developing an IoT ecosystem in the same location, focused on smart irrigation, and this prototype is an integral part of the architecture.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the practical feasibility of using LoRaWAN in rural Mozambican agricultural environments, characterized by the absence of electrical and telecommunications infrastructure. Based on the analysis of indicators such as RSSI, SNR and PDR, it was found that the horizontal distance and, above all, the relative altitude between devices have a significant influence on the quality of communication.

Even with operational limitations, such as manual firmware reboot, lack of GPS and impossibility of real-time monitoring due to lack of internet, the network maintained a packet delivery rate of over 89% and more than 24 hours of energy autonomy, reaffirming the energy efficiency of LoRa technology in decentralized applications.

It was also found that installing gateways in elevated areas is an effective strategy for mitigating signal losses, expanding coverage in agricultural areas located in low-lying areas — such as riverbanks. This approach is compatible with technical recommendations from specialized literature on LPWAN networks.

It is important to highlight that the choice of LoRaWAN was not motivated only by the lack of internet, but rather by its flexible architecture, operation in free bands, low cost and low energy consumption, factors that give it greater autonomy and scalability in rural IoT projects, compared to other technologies such as NB-IoT or Starlink [

34].

Based on the observed limitations, improvements were proposed such as:

Use of modules with GPS and RTC;

Firmware automation with periodic sending;

Adoption of higher gain antennas;

Integration of renewable energy sources;

Formation of technical teams with radio communication.

These measures are essential to enhance the accuracy, scope, and replicability of future trials.

In addition to the technical and energy benefits demonstrated, it is important to highlight the potential social impact of the solution presented. The adoption of LoRaWAN networks by small farmers and rural cooperatives can signify a major advancement in the ability to monitor crops, manage irrigation and respond to climate events more efficiently, even in places without electricity or cellular networks. Because it is a low-cost, operator-independent and energy-independent technology, it can be implemented locally with simple training and accessible resources, promoting digital inclusion, agricultural sustainability and improved productivity [

35,

36]. This approach is aligned with the “Partner2Connect” agenda, which mobilizes government leaders in the technology sector globally to bring digital inclusion to the most difficult-to-connect communities, so that no one is excluded from digital opportunities [

37].

This work therefore contributes useful empirical evidence for digital inclusion, smart agriculture and environmental monitoring projects, and can be replicated in other rural African communities with similar connectivity challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.J.C.; Methodology, N.J.C.; Investigation, N.J.C.; Hardware and field logistics, O.P.; Supervision, O.P.; Writing—Original Draft, N.J.C.; Writing—Review & Editing, O.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is funded by FCT/MECI through national funds and co-funded EU funds under UID/50008: Instituto de Telecomunicações (IT-IUL).

Acknowledgments

This article is part of the doctoral research conducted by the first author at ISCTE – Instituto Universitário de Lisboa (Iscte-IUL), under the academic supervision of Prof. Octavian Postolache. The authors also acknowledge the IT-IUL support and access to hardware resources that made this field study possible.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BLE |

Bluetooth Low Energy |

| CRASA |

Communications Regulators’ Association of Southern Africa |

| GPS |

Global Positioning System |

| IDE |

Integrated Development Environment |

| ISM |

Industrial, Scientific and Medical (frequency band) |

| LPWAN |

Low Power Wide Area Network |

| LoRa |

Long Range |

| LoRaWAN |

Long Range Wide Area Network |

| NB-IoT |

Narrowband Internet of Things |

| NFC |

Near Field Communication |

| OTAA |

Over-The-Air Activation |

| PDR |

Packet Delivery Rate |

| RSSI |

Received Signal Strength Indicator |

| RTC |

Real-Time Clock |

| SADC |

Southern African Development Community |

| SNR |

Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| TTN |

The Things Network |

References

- M. Z. Hasan, M. S. Hossain, and M. Alam, “IoT-Enabled Smart Agriculture: Toward an Automated Monitoring and Irrigation System,” IEEE Internet Things J, vol. 9, no. 12, pp. 9523–9534, 2022.

- U. Raza, P. Kulkarni, and M. Sooriyabandara, “Low Power Wide Area Networks: An Overview,” IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 855–873, 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Adelantado, X. Vilajosana, P. Tuset-Peiro, B. Martinez, J. Melia-Segui, and T. Watteyne, “Understanding the Limits of LoRaWAN,” IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 55, no. 9, pp. 34–40, 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Lin and H. Su, “Experimental Evaluation and Performance Improvement of Bluetooth Mesh Network With Broadcast Storm,” IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 137810–137820, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Microsoft, “Tecnologias e protocolos de IoT,” Microsoft.com. Accessed: Feb. 05, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://azure.microsoft.com/pt-br/solutions/iot/iot-technology-protocols.

- M. Mancini, “Internet das Coisas: História, Conceitos, Aplicações e Desafios,” 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326065859.

- Yan Chen and Yi Qian, “Narrowband Internet of Things: Implementations and Applications,” IEEE Internet Things J, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 1505–1512, 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Vangelista, “Frequency Shift Chirp Modulation: The LoRa Modulation,” IEEE Signal Process Lett, vol. 24, no. 12, pp. 1818–1821, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- L. Meireles, L. Garcia, and A. Segundo, “Coisas para se saber sobre a Internet das Coisas – Um Guia Prático –,” in Anais de XXXVI Simpósio Brasileiro de Telecomunicações e Processamento de Sinais, Sociedade Brasileira de Telecomunicações, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Lora Alliance Inc, “RP002-1.0.2 LoRaWAN® Regional Parameters NOTICE OF USE AND DISCLOSURE 4,” Fremount, 2020.

- CRASA, “Southern African Development Community (SADC) Frequency Allocation Plan,” Gaborone, Botswana, 2019. Accessed: Jun. 13, 2025. [Online]. Available: . [CrossRef]

- S. K. Musonda, M. Ndiaye, H. M. Libati, and A. M. Abu-Mahfouz, “Reliability of LoRaWAN Communications in Mining Environments: A Survey on Challenges and Design Requirements,” Journal of Sensor and Actuator Networks, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 16, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Torres-Sanz, J. A. Sanguesa, F. Serna, F. J. Martinez, P. Garrido, and C. T. Calafate, “Analysis of the Influence of Terrain on LoRaWAN-based IoT Deployments,” in Proceedings of the Int’l ACM Conference on Modeling Analysis and Simulation of Wireless and Mobile Systems, New York, NY, USA: ACM, Oct. 2023, pp. 217–224. [CrossRef]

- B. Abdallah, S. Khriji, R. Chéour, C. Lahoud, K. Moessner, and O. Kanoun, “Improving the Reliability of Long-Range Communication against Interference for Non-Line-of-Sight Conditions in Industrial Internet of Things Applications,” Applied Sciences, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 868, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Augustin, J. Yi, T. Clausen, and W. Townsley, “A Study of LoRa: Long Range & Low Power Networks for the Internet of Things,” Sensors, vol. 16, no. 9, p. 1466, Sep. 2016. [CrossRef]

- M. N. M. G. Paulo Grilo, “Latency and Capacity in LoRaWAN Networks: A Systematic Review,” IEEE Wirel Commun, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 100–107, 2020.

- Mouzinho Rafael, “Cerca de 73% da população moçambicana não tem acesso a serviços de Internet,” aimnews.org. Accessed: Jan. 24, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://aimnews.org/2024/06/19/cerca-de-73-da-populacao-mocambicana-nao-tem-acesso-a-servicos-de-internet/.

- Alliance for Affordable Internet (A4AI), “Moçambique: Resumo do Relatório de Acessibilidade 2017,” Washington, DC, USA, 2017. Accessed: Oct. 26, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://a4ai.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/A4AI_2017_AR_Mozam_Screen_Portuguese_AW-1.pdf.

- Daniel Trefilio, “3 motivos para contratar a Starlink — e outros 3 para ‘fugir’ da rede,” TechTudo. Accessed: Feb. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.techtudo.com.br/listas/2024/11/3-motivos-para-contratar-a-starlink-e-outros-3-para-fugir-da-rede-edmobile.ghtml.

- MOKOLORA, “O que é LoRaWAN?,” mokolora.com. Accessed: Feb. 10, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.mokolora.com/pt/what-is-lorawan/.

- M. V. Gonsalves da Silva, “O Paradoxo do uso dual da Tecnologia: O caso da Starlink em conflitos recentes e nas atividades ilicitas na Amazonia legal Brasileira,” Panorâmico, vol. 2, no. 6, pp. 44–51, 2023, Accessed: Jan. 28, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://ompv.eceme.eb.mil.br/images/publicacoes/panoramico/panoramico-vol2-n06-set-dez2023/O-PARADOXO-DO-USO-DUAL-DA-TECNOLOGIA-O-CASO-DA-STARLINK-EM-CONFLITOS-RECENTES-E-NAS-ATIVIDADES-ILICITAS-NA-AMAZONIA-LEGAL-BRASILEIRA-Marcus-Vinicius-Goncalves-da-Silva.pdf.

- T. S. Cardeal, Internet das Coisas e seus Protocolos: Conhecendo Protocolos. Formiga (MG): MultiAtual, 2022. [CrossRef]

- UN-HABITAT, “Moçambique: Promover a urbanização sustentável em Moçambique como motor de desenvolvimento socioeconómico, da resiliência climática e da paz (Resumo Nacional),” Maputo, 2023. Accessed: Oct. 26, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2023/07/mocambique_resumo_nacional_pt.pdf.

- N. M. Rosário, “Agronegócio em Moçambique: Uma breve análise da situação de estrangeirização do Agronegócio,” Sociedade e Território, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 183–200, Aug. 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Bartolín-Arnau, D. Todoli-Ferrandis, V. Sempere-Payá, J. Silvestre-Blanes, and S. Santonja-Climent, “LoRaWAN Networks for Smart Applications in Rural Settings,” IETE Technical Review, vol. 40, no. 3, pp. 440–452, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Petäjäjärvi, K. Mikhaylov, M. Pettissalo, J. Janhunen, and J. Iinatti, “Performance of a low-power wide-area network based on LoRa technology: Doppler robustness, scalability, and coverage,” Int J Distrib Sens Netw, vol. 13, no. 3, p. 155014771769941, Mar. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Dragino Technology Co., “LoRa Shield for Arduino – Technical Specifications,” Dragino. Accessed: Dec. 24, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://www.dragino.com/products/lora/item/102-lora-shield.html.

- World Bank, “ Southern Africa Economic Outlook: Digital Integration in the SADC Region,” Washington, DC, 2023.

- TTN, “LoRaWAN: Frequency Plans by Country,” thethingsnetwork.org. Accessed: May 30, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.thethingsnetwork.org/docs/lorawan/frequencies-by-country//?utm_source=chatgpt.com.

- Emma He, “O que é LoRaWAN? Tudo o que você precisa saber sobre LoRaWAN para soluções IoT?,” Minew. Accessed: Feb. 06, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.minew.com/pt/what-is-lorawan/.

- A. Roy, “Near Field Communication (NFC): An Overview,” Int J Comput Appl, vol. 113, no. 17, pp. 1–5, 2015.

- Tesswave-Antena-Soluition, “Para que servem as Bandas de Frequência LoRaWAN (WAN-Média)?,” tesswave.com. Accessed: Mar. 09, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.tesswave.com/pt/frequency-bands-for-lorawan/.

- Eduardo Godoy, “O que é The Things Network (TTN)?,” The Things Network. Accessed: Mar. 03, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.thethingsnetwork.org/community/sorocaba/post/o-que-e-the-things-network-ttn.

- LogPyx, “LoRa: o que é essa solução para a conectividade das coisas,” https://logpyx.com/. Accessed: Nov. 24, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://logpyx.com/lora-solucao-para-conectividade-das-coisas/.

- Y. Park and B. Jeon, “An Acquisition Method for Visible and Near Infrared Images from Single CMYG Color Filter Array-Based Sensor,” Sensors, vol. 20, no. 19, p. 5578, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhao, F. Yang, D. An, and J. Lian, “Modeling Structured Dependency Tree with Graph Convolutional Networks for Aspect-Level Sentiment Classification,” Sensors, vol. 24, no. 2, p. 418, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- INCM, “Moçambique Comprometido com a Inclusão Digital,” incm.gov.mz. Accessed: Nov. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.incm.gov.mz/index.php/sala-de-imprensa/noticias/497-mocambique-comprometido-com-a-inclusao-digital.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).