1. Introduction

Water bodies support social and economic activities, such as human consumption, agriculture, industry, and wildlife preservation. However, these resources face increasing restrictions due to pollution caused by natural and human activities. Thus, water usage is subject to significant restrictions for purposes such as human supply [

1]. The rapid demographic growth and urbanization resulted in elevated pollution levels in the region’s waters [

2,

3]. Consequently, remote and continuous sensor-based monitoring has become essential.

In traditional water monitoring, samples are collected manually and sent to laboratories for analysis using chemical methods, consuming human, time, and financial resources [

4]. However, those techniques do not provide real-time insights or low-cost solutions. In contrast, low-cost sensors, integrated into microcontrollers such as Esp32, can be deployed to collect data such as pH, turbidity, temperature, and others, from water bodies in a cost-effective solution of data collection device [

5].

In addressing these challenges, deploying Internet of Things (IoT) technology has emerged as a promising solution for real-time environmental monitoring. Among IoT technologies, LoRa (Long Range) offers the possibility of long-distance communication, low power consumption, and cost-effective solutions to the aforementioned IoT scenarios [

6]. To address it, LoRa utilizes a modulation technique to transmit information using chirp signals on the physical layer [

7,

8]. Additionally, it provides specific physical parameters to ensure proper communication. These parameters include:

Bandwidth (BW): refers to the communication channel’s capacity to transmit data within a specific time frame. BW significantly influences data transmission speed and sensitivity to noise. For instance, increasing bandwidth enhances data transmission speed but may reduce sensitivity [

8].

Spreading Factor (SF): determines the trade-off between data rate and range in LoRa. Lower SF values provide higher data rates and shorter ranges, suitable for nodes closer to gateways. In contrast, higher SF values are preferable for nodes situated at a greater distance. LoRa defines six SF values (7 to 12) that influence the chirp bit count and directly influence energy consumption and data rate [

8,

9].

Coding Rate (CR): determines the bits allocated for error-checking transmission redundancy. In summary, a higher CR value implies a greater degree of redundancy, which contributes to an improvement in the error-correction capabilities of the transmitted data.

Transmission Power (TP): TP represents the transmission power used by the transmitter. Lower TP values contribute to reduced battery consumption, while higher values increase the probability of successful communication and extend the communication range.

Given the potential combinations of these parameters—over 6720 in total [

9]—the proper selection of LoRa communication settings is crucial to optimize network performance, minimize packet collisions, and extend the battery life of sensor nodes [

9,

10,

11]. Further, energy consumption can vary —by factors of more than 100 [

11]—depending on the selected parameters, highlighting the requirement for careful configuration to ensure the longevity of battery-powered nodes, which could be useful for remote monitoring scenarios.

Deploying LoRa-based sensors in remote regions, including the challenging Amazon region, offers a cost-effective alternative, despite the geographical and environmental challenges, including non-line-of-sight (LoS) communication and dense forest cover [

12].

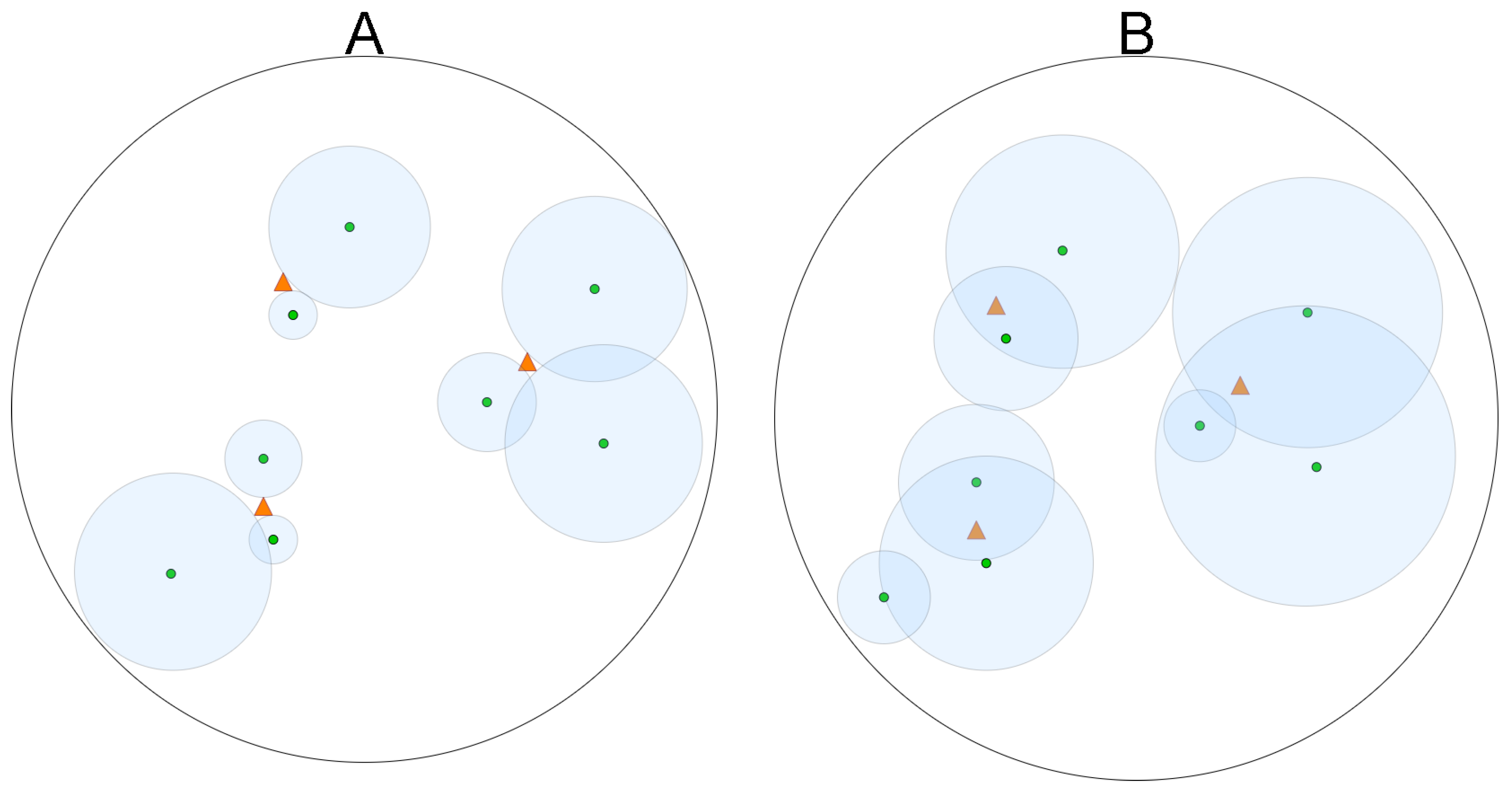

These geographical features and communication through forests contribute to distinct interference levels. For instance,

Figure 1A illustrates an example of LoRa communication among devices when the LoRa parameters are set into the optimal values in the communication to gateways represented by a red triangle. At the same time, in

Figure 1B, incorrect parameter selection can lead to suboptimal configurations and waste of energy resources [

9,

11].

Furthermore, in the context of this project, it is relevant to highlight that the communication must include transmission across forested environments.

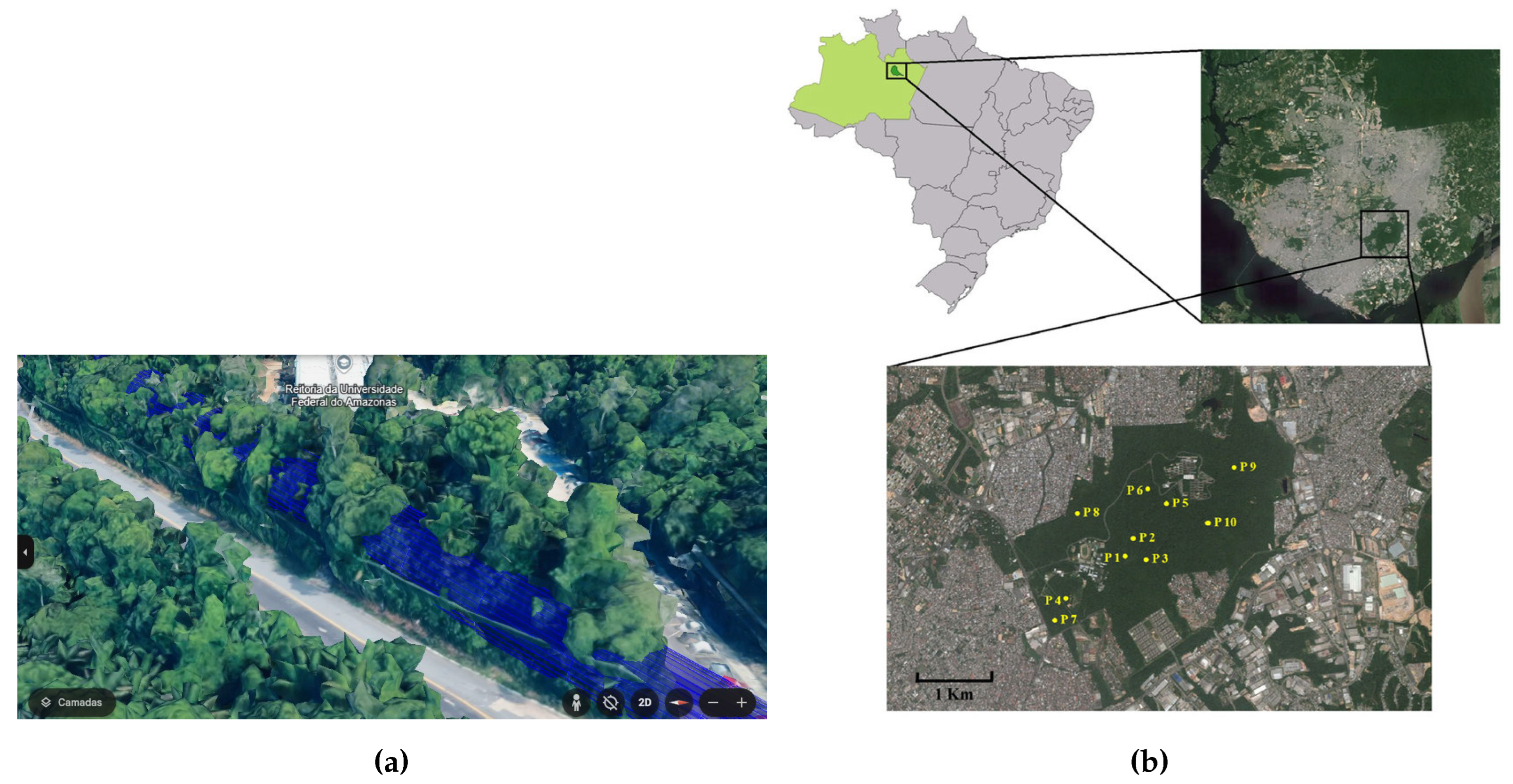

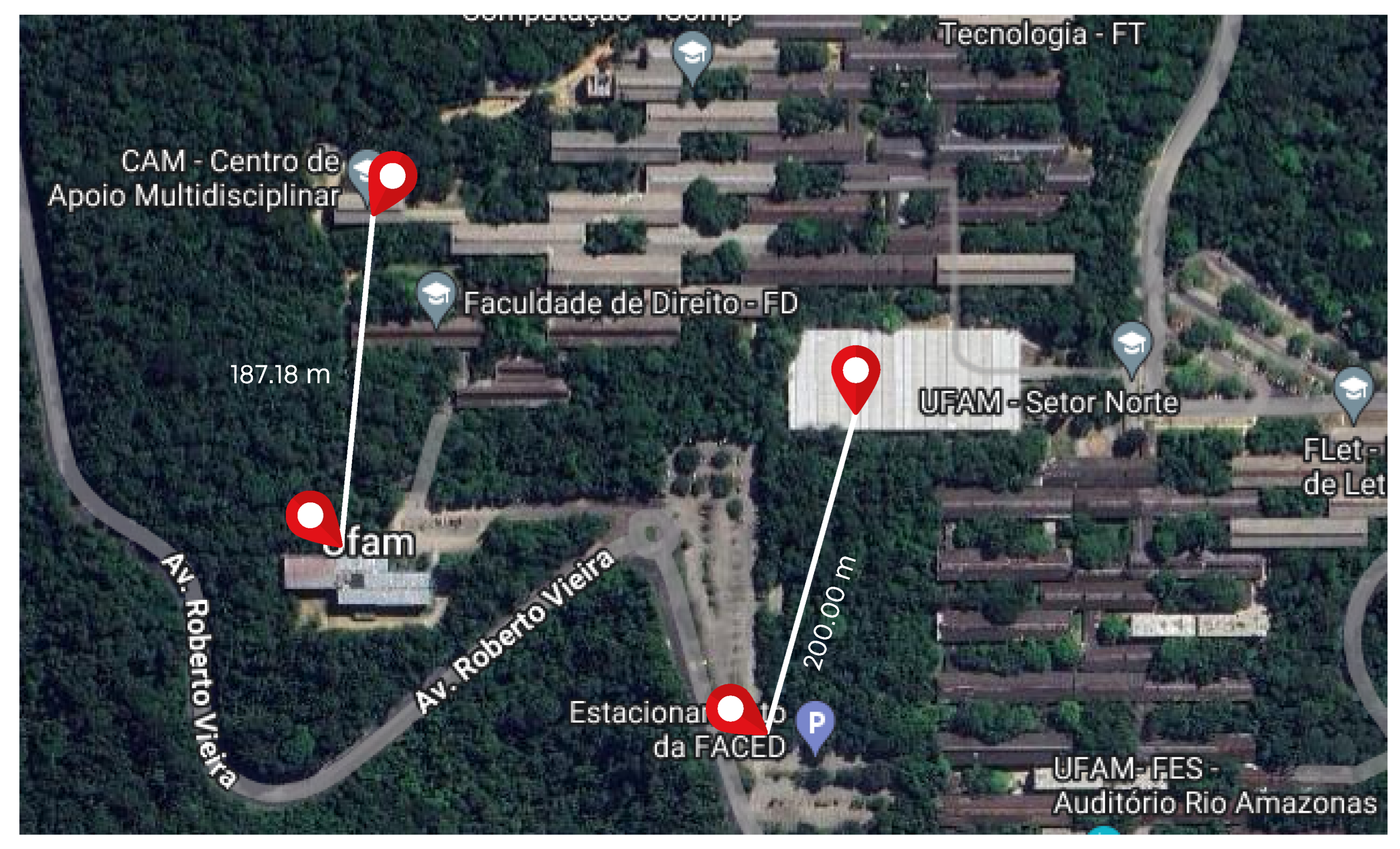

Figure 2a illustrates an example of the line-of-sight communication used in this work’s experiments. The image was taken on the campus of the Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM), located in Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil (03º04’34”S, 59º57’30”W; DATUM = WGS84). Despite being situated on a university campus, this environment likewise illustrates the same conditions of real-world experiments in the Amazon Rainforest. UFAM hosts one of the largest urban forest fragments of the planet, a 776-ha campus mainly composed of primary and secondary forest, as well as anthropic areas and water bodies as illustrated in

Figure 2b taken by the research in [

13].

Despite the recent literature about the usage of LoRa in IoT scenarios [

14], we have found a lack of research studies on LoRa parameter selection, such as the absence of combining multiple LoRa parameters and the need for experimentation in real and challenging environments such as remote areas or forest areas [

15]. These research gaps highlight the requirement for researchers to consider non-line-of-sight (LoS) conditions typically found in forest environments.

In response to these challenges, this paper offers the following contributions: a) it proposes a novelty algorithm as one of the first works in the literature to incorporate the three major LoRa metrics (Received Signal Strength Indicator (RSSI), Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), and Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR)) in the parameter selection algorithm design; b) introduces an in-situ rainforest transmission characterization and validation conducted in a real and challenging Amazon rainforest scenario; c) proposes an algorithm for selecting LoRa parameters using the traditional binary search methodology. This approach provides an accurate representation of LoRa transmission in a challenging scenario such as that experienced in the Amazon region.

The proposed algorithm, entitled LoRaBB (Lora Parameter Selection via Binary Search), utilizes a

R-array of reference values from key LoRa metrics — RSSI, SNR, and PDR - by combining the following LoRa parameters: SF, BW, and PT. The

R-array, embedded in the source code of each deployed node, serves as a benchmark. During the LoRa parameter selection phase, each node compares its current communication metrics with these reference values to identify feasible arrangements for the parameters selected. Finally, the proposed algorithm compares parameters and metrics employing a binary search methodology, fully described in

Section 3.1 until appropriately adjusted to optimal values.

To validate and test the LoRaBB algorithm, we conducted characterisation experiments to evaluate LoRa transmission in a forest scenario, as illustrated in

Figure 2a, with low or non-line-of-sight (LoS) conditions. The results were evaluated to verify if the strategy of

built-in R-array is suitable for representing, in a numerical form, the combination of selected parameters in a LoRa transmission between nodes.

The results have demonstrated that the LoRaBB algorithm can fit into a forest communication real-world scenario, encompassing different distances and levels of interference based on the LoRa parameter combination. In addition, the results have shown that LoRa is more suitable for the forest scenarios when compared to the ADR algorithm used in LoRaWAN, achieving a Time on Air (ToA), 16.20% lower, and theoretical energy consumption spent during transmission.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the related works found in the literature, while

Section 3 presents the general overview of the architecture that supports the solution proposed, as well as the proposed algorithm.

Section 4 presents the design of the experiment to validate the proposed algorithm. Finally,

Section 5 and

Section 6 present the major results and discussions, as well as the conclusions and future remarks.

2. Related Works

Previous studies on LoRa have been focused predominantly on the applicability of LoRa in IoT scenarios and applications, particularly in contexts such as smart cities, animal tracking, environment monitoring, and other scenarios [

16,

17].

In LoRa transmissions, several parameters must be adjusted to ensure the link transmission quality between nodes or between nodes and gateways, optimize energy consumption, and improve network performance. Thus, these parameters must be used for:

i) link estimation quality: when the nodes estimate the communication quality based on LoRa metrics such as RSSI, SNR and PDR; and

ii) parameter selection: when nodes adjust transmission parameters based on the assessed communication quality [

18].

LoRa devices can be configured with different values of SF, BW, CR, and TP from 0dBm to 14dBm (or 20dBm in some devices) [

14]. Li et al. describe that parameter selection can be influenced by environmental factors, necessitating consideration of trade-offs between packet delivery ratio and energy consumption [

14]. These insights align with other research findings, indicating the need to adapt transmission parameters according to deployment scenarios [

14,

19,

20,

21].

For instance, Gao et al. [

22] demonstrate that the distance between the transmitter and receiver should lead LoRa parameters selection to achieve a low data rate and increase the chances of delivery, particularly over greater distances. Moreover, Angrisani et al. [

23] evaluated that, although LoRa is highly robust to high noise levels, the parameters’ variation can impact packet losses over different values of SF, CR, and BW. Cattani et al. further concluded that the packet delivery ratio and the parameter selected are on a narrow boundary, where the packet delivery ratio was only 10% lower than that of the slowest LoRa parameter selected when a node was distanced from the gateway [

21].

Another notable LoRa parameter selection strategy is the Adaptive Data Rate (ADR) strategy, initially implemented by The Things Network (TTN) according to Semtech’s development recommendations [

24]. ADR adjusts LoRa parameters based on the SNR values from the most recent packets received during the algorithm’s execution. To address it, the gateway listens for frames transmitted in multiple frequency channels. However, as highlighted by Wang et al. [

18], the ADR adds computational complexity to the gateway’s processes. In a low-cost system, as discussed in this paper, increased computational complexity can lead to a costly gateway build process.

To automate the selection of LoRa parameters, Serati et al. [

25] have developed an algorithm, entitled ADR-Lite, which employs a binary search methodology. The ADR-Lite considers four parameters: SF, TP, Carrier Frequency (CF), and CR, using Packet Delivery Ratio as the query key, to identify the most suitable setting to achieve improved PDR values. Moreover, an upper bound for energy consumption values is considered, specifying that the parameter chosen must adhere to this criterion to be considered as the optimal choice. However, the strategy design did not consider RSSI and SNR factors in algorithm design, and even the BW parameter, which plays an important role in energy consumption, was not incorporated into its combination of parameters.

Following a similar approach, de Jesus et al. proposed the algorithm ADR-X [

26] by slightly modifying the classic ADR was to incorporate an adaptive threshold representing the acceptable SNR level to compensate inaccurate estimation of the transmission quality, such as found in lossy channels. Unlike the traditional ADR, this threshold is automatically adjusted for each node.

The research by Khalifeh, Shefaa, and Darabkh [

27] presented an algorithm that enables the dynamic exchange of channels to select the option with the least traffic and choose the more appropriate SF to support the data rate demand in LoRa communications. Moreover, the aforementioned research presented a need for experimentation in real environments and it is a centralized solution, not suitable for some IoT scenarios. Further, the details of the algorithm design were not fully given.

Moreover, a recent trend, widely disseminated in the literature, involves the application of machine learning (ML) techniques to select smart LoRa parameters. In the research referenced [

28] and [

29], the authors investigated this methodology that prioritizes energy efficiency and improves the PDR using conventional ML approaches. Similarly, Ilahi et al. [

30] applied a deep learning algorithm formulated as a Markov decision process to optimize the PDR in the ADR process.

Finally, as evidenced in the related works analyzed, the current research focuses on performance evaluation within simulated environments. In addition, there is a gap concerning the study of parameter selection in wooded contexts, particularly in scenarios such as Amazonian rainforest regions. The

Table 1 presents a summary of the main literature research analyzed, the LoRa parameter used in their research and scenarios conditions.

3. Architecture Overview

The architecture and all the protocols and algorithms presented in this work were developed using ESP32 Heltec V2 devices (as End Node Devices) and V3 devices (as Gateway). Each one of these devices was equipped with SX1276 and SX1262 modules, respectively. To enhance signal quality, Steelbras AP3900 antennas with 5 dBi gain were utilized. Furthermore, the data generated during samplings were stored using a Raspberry Pi 4 Model B and a Pi 3 Model B+ in gateway and end node devices, respectively. To clarify, in the context of this paper, each end node device is integrated to water sensors and transmits a C-styled struct payload of 20 bytes over LoRa. Considering that only packets with information about data collected is sent, there is no reasonable reason to explore higher payloads sizes.

Further, it is important to highlight that LoRaWAN capabilities such as LoRaWAN gateways were not deployed due to the unavailability of LoRaWAN gateways in the Amazonas region. Further, using microcontrollers and shields to deploy LoRaWAN gateways could increase the costs of the project contextualized in this paper up to 10 times.

The following subsections detail the establishment of LoRa parameters between end nodes and gateway, providing an overview of ADR algorithm, and describing the operational process of the proposed LoRaBB algorithm.

3.1. Tecnique Overview Requirements

The communication protocol is designed based on the requirements that both LoRaBB and ADR must fulfil. The following assumptions were adopted in the design of the techniques presented in this research:

Stationary end nodes: each node deployed remains stationary, serving as a communication network endpoint. However, its initial location is initially unknown to both nodes.

Node-gateway discovery: gateway is designed to attempt to initiate the LoRa parameter selection by using a set of default parameters, facilitates the node discovery phase.

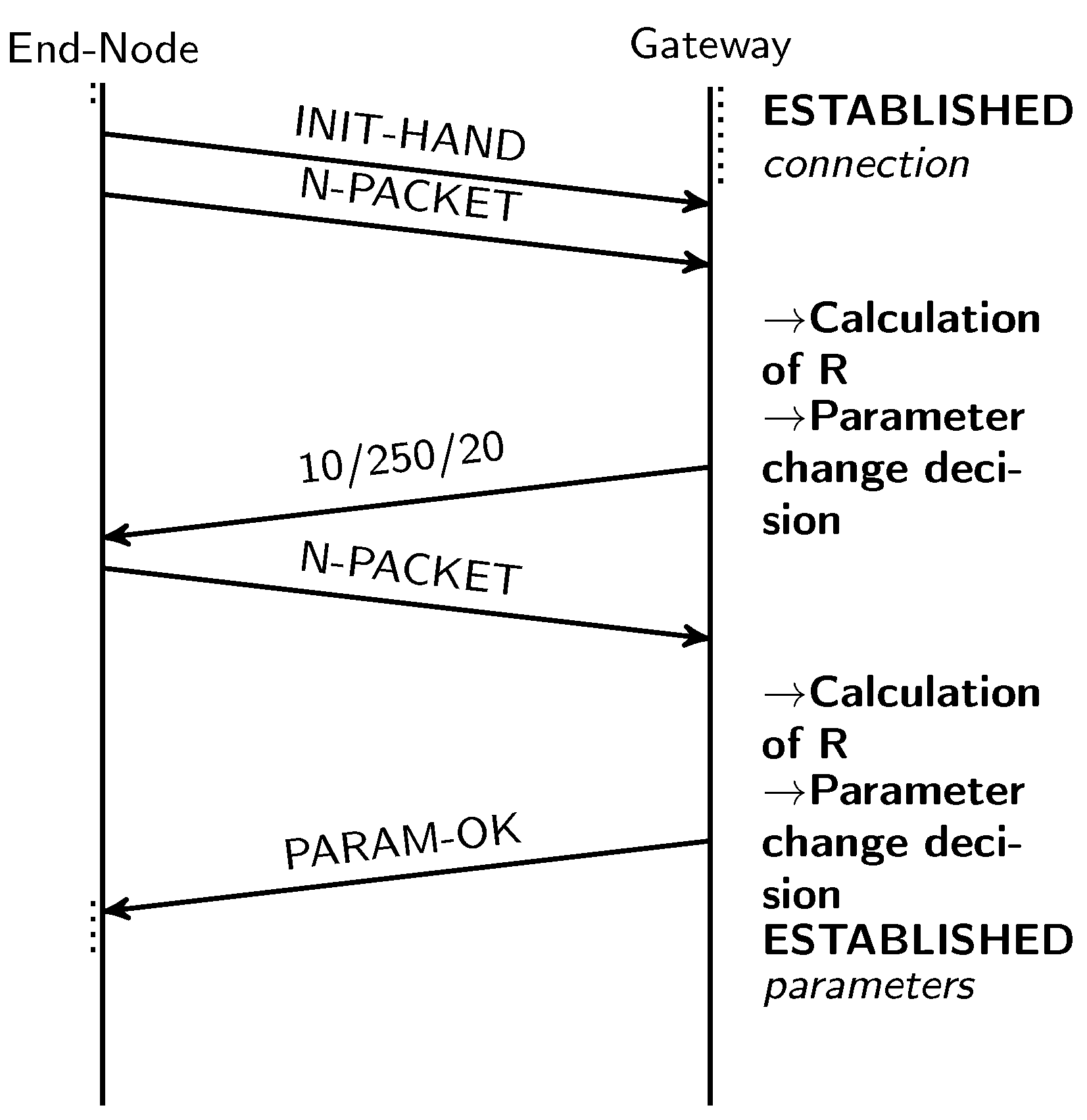

We assume that algorithms can be triggered to initiate when gateway and end nodes are in the same set of default parameters (DP); enabling the three-way handshake.

The three-way handshake was employed to establish the device connection and initiate the algorithms steps. To establish the initial exchange of messages, the DP was adopted, as summarized in

Table 2, as they theoretically provide a more robust setting for data transmission. This handshake mechanism allows devices to verify compatibility and ensures the synchronized adjustment of their parameters during communication.

Figure 3 presents this whole process, concisely describing the preliminary algorithmic steps.

Moreover, each gateway is designed to retains information about LoRa parameters to facilitate the communication with other nodes, periodically adjusting its settings for data transmission and new nodes discovering.

3.2. ADR LoRaWAN

The Adaptive Data Rate (ADR) algorithm from The Things Stack is a widely well-known strategy for optimizing communication in LoRaWAN networks. The ADR analyzes the SNR to determine the most appropriate data rate and transmission power setting for the network devices [

31].

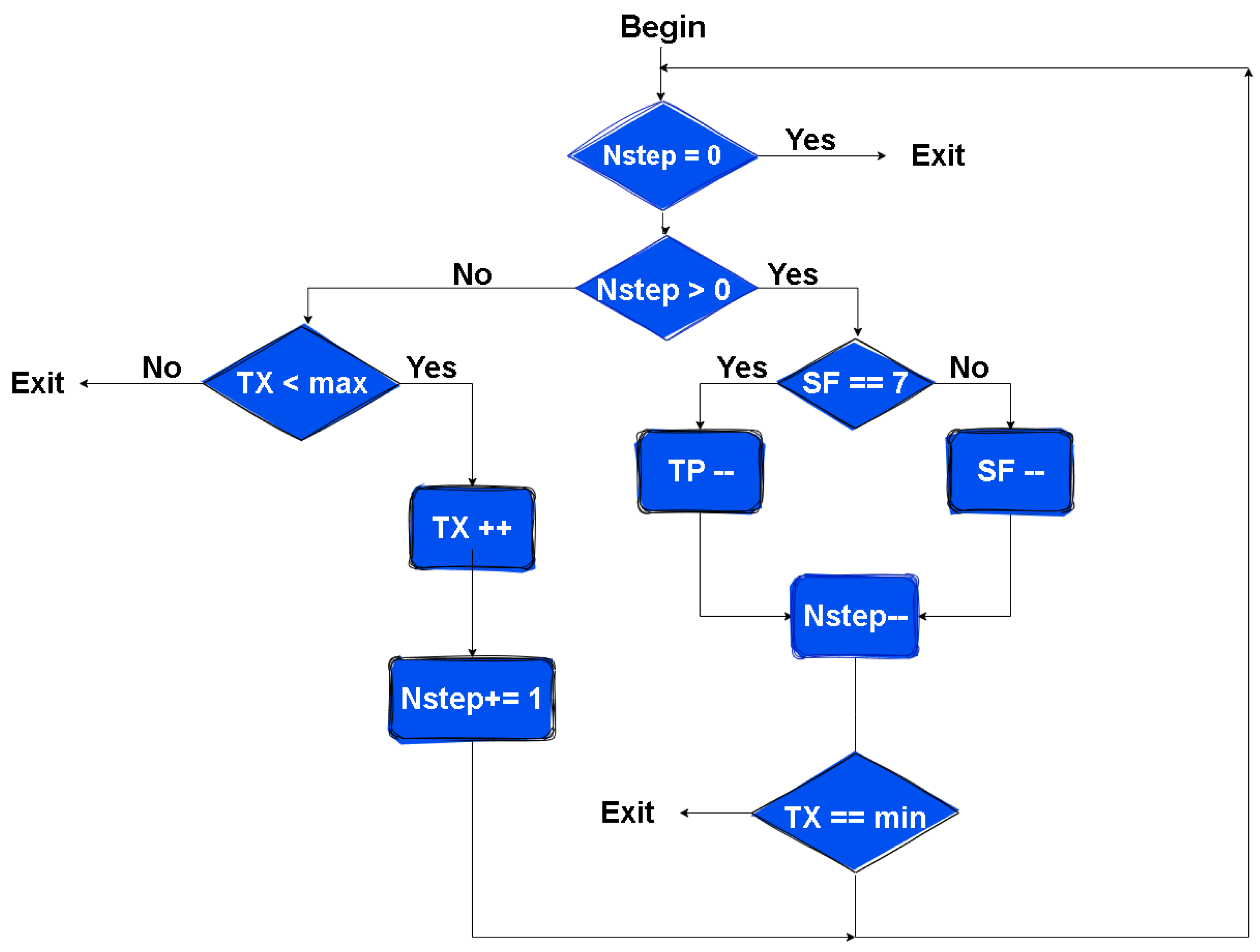

The Equation (

1), in the first phase of ADR execution, determines the number of steps performed in the algorithm, as illustrated in

Figure 4. Thus, the gateway estimates the maximum SNR value (

) of the last

N transmissions, while the value of

varies between 5 and

[

32]. In our implementation of the algorithm, we set

. The

represents the SNR required for successful demodulation.

3.3. The Proposed LoRaBB Parameter Selection Algorithm

Optimizing the trade-off between convergence time toward the optimal configuration and parameter selection drives the decision to employ the binary search methodology in our proposed algorithm. Therefore, we designed the proposed algorithm in two main phases: the R-array building and the algorithm design, as further described.

3.3.1. The R-Array Building

Initially, we built a

R-array using data collected from practical experiments conducted in a forest environment. This array is an instrument to evaluate the relationships between RSSI, SNR, and PDR regarding to SF, BW, and PT values in our forest scenario. In summary, it is a method of representing communication performance over different parameters combinations. Moreover, we followed some consolidated LoRa theories to build the

R-array:

a)

higher SF produces higher reliability, resulting in lower receiver sensitivity and increasing the probability of packet delivery [

33,

34] and

b)

Time on Air doubles the transmission duration at each increase in SF[

34]. Therefore, LoRaBB intends to represent these affirmations in a single value for each parameter combination, called

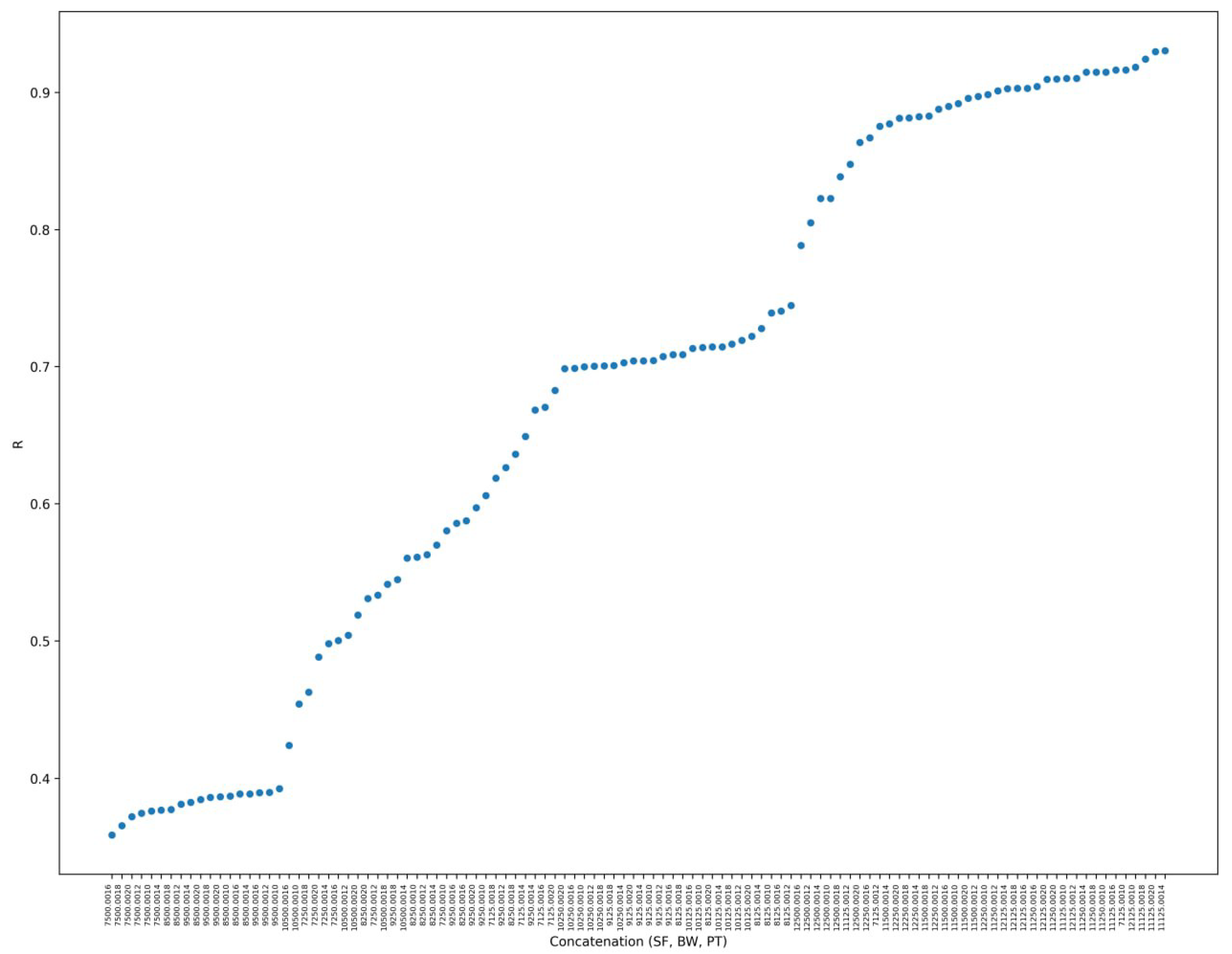

R.

Each entry

R in the

R-array represents a value derived from a reward equation called

R (Equation (

2)). Assigning weights (

,

,

) to each metric, so, RSSI, SNR, and PDR exhibit distinct patterns for specific parameter combinations. Additionally, RSSI, SNR, and PDR values used in both the

R-array and algorithm design undergo normalization, ensuring a standardized range of 0 to 1 using the formula

, such that

RSSI, SNR, PDR}. Finally, it is worth highlighting that the computation of the

R value for each parameter combination during this phase is performed using the average of the RSSI, SNR, and PDR values found in the experiments. In the equation, this is represented by the overbar symbol.

To build the

R-array, two ESP32 were placed within the campus of the Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM) to generate the results of data communication within the forest. As stated in

Section 1, the UFAM campus is one of the largest urban forest environments, which is suitable for any characterization and further validation in this project context. The data collected characterized the Amazon rainforest environment and established the base

R-array used as a parameter for LoRaBB.

The ESP32 modules, designed as transmitter and receiver (similarly to the end node and gateway behavior, respectively), were placed at different locations and separated by significant distances to exchange data through an area of vegetation typical of the Amazon rainforest. These characterization experiments occurred in sunny conditions, with detailed parameter values provided in

Table 3.

In the initial experiment, the transmitter was situated at approximately 12 meters on the third floor of the Institute of Computing (IComp) building, while the receiver was positioned at a height of approximately 8 meters on the second floor of the Analytical Chemistry building. Twenty packets were transmitted for each parameter combination, covering 107 meters during this stage. Subsequently, the transmitter device was relocated to the ICOMP2 building for a subsequent experiment, extending the distance to 134 meters. The experimental placements are illustrated in

Figure 5.

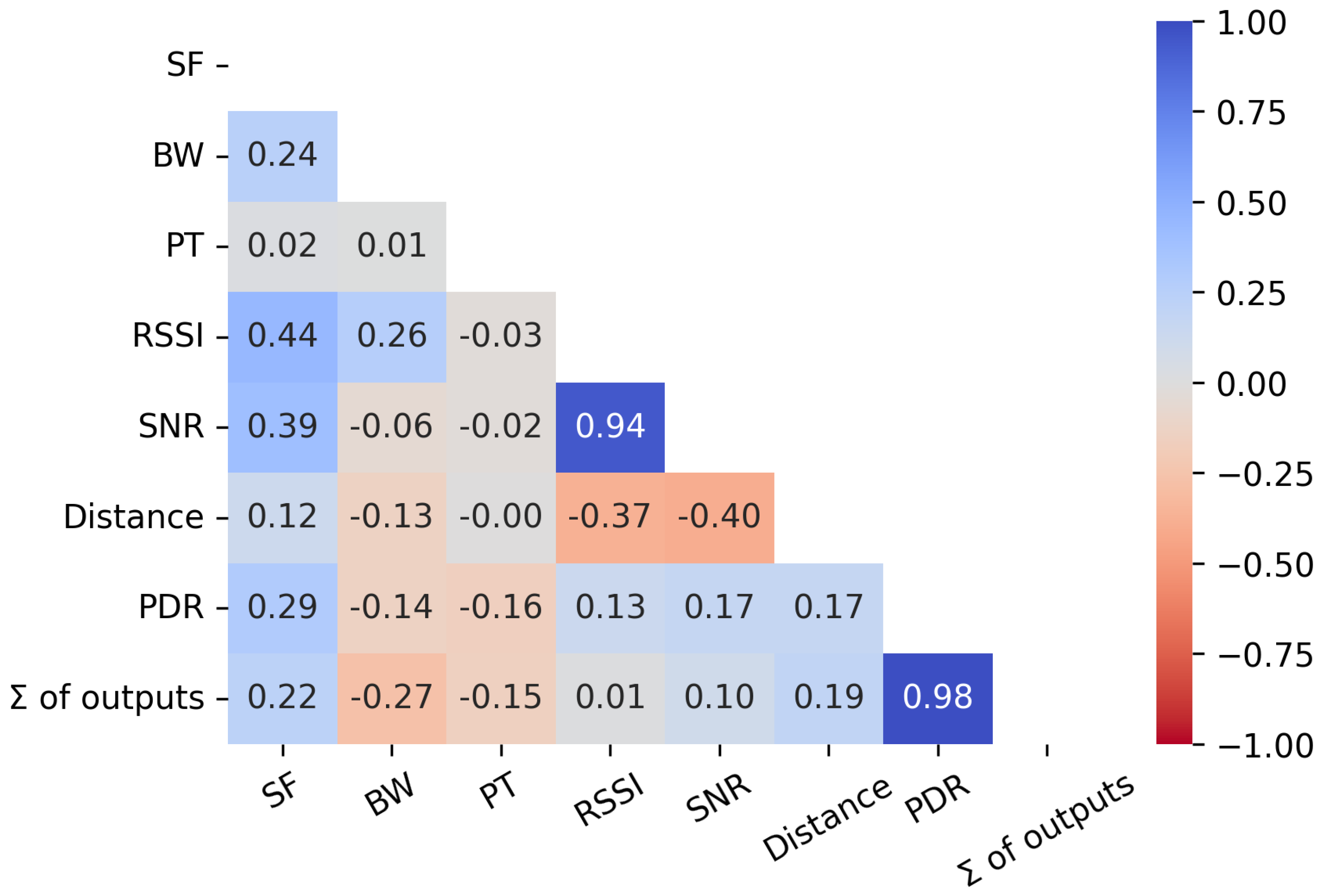

The results from practical experiments illustrate that the behaviour of the evaluated metrics (RSSI, SNR, and PDR) can be influenced by the values of SF, BW, and PT. In addition, it was added another value named ∑ of outputs, a straightforward summation of normalized RSSI, SNR, and PDR values. This underscores the appropriateness of our R characterization methodology in modelling the parameter selection algorithm.

While factors like distance negatively impact RSSI and SNR, as depicted in

Figure 6, these metrics can be directly influenced by SF and BW choices. Thus, we can organize them in a way that clarifies the impact of parameter selection on

R, as shown in

Figure 7.

Moreover, it was identified that PT has a lower or no relation to RSSI, SNR, and PDR as also illustrated in

Figure 7, where the chosen PT values for each parameter combination are spread over the plot. Furthermore, the left values on the plot where

result in some packet loss, particularly in the experiment with 134.55 meters of distance.

Figure 7 also demonstrates that parameter choices yield different

R values, which can have implications, such as in energy consumption or PDR. For instance, suppose a parameter combination that generates an

R value close to 1 is chosen for a specific communication. When analyzed, it becomes evident that this parameter selection tends to favour values that could maximize delivery possibilities, especially with higher SF and lower BW values, which directly impact PDR and energy consumption, for example.

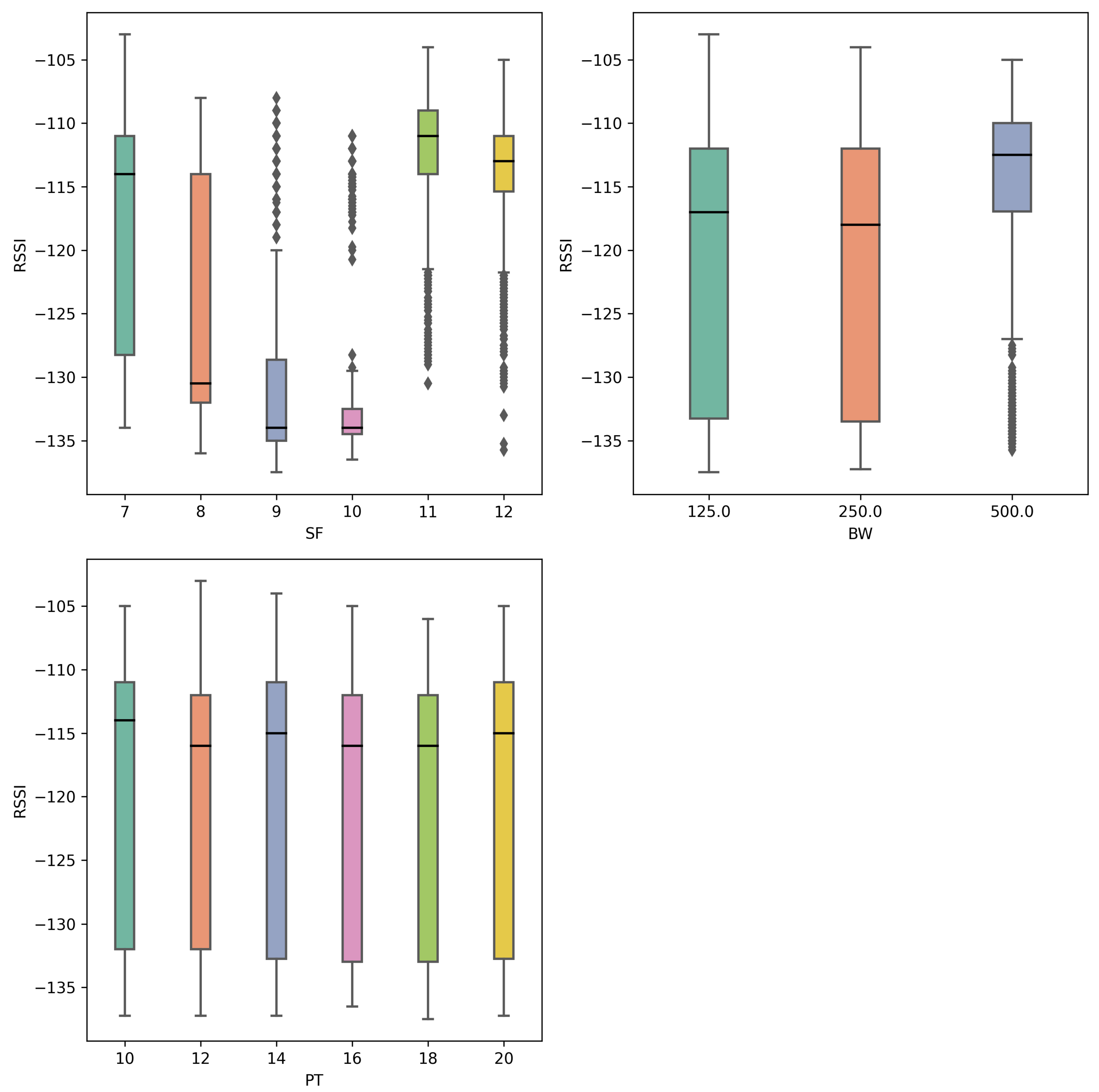

Subsequently, the R-array is sorted based on the value of R entry and deployed into the firmware code of each deployed end node. It is important to highlight that the first step of this work demonstrated that the values on R-array could not follow a usual distribution of LoRa parameter combination. This irregular pattern may be attributed to signal attenuation and environmental factors such as dense foliage, which can affect certain SF values, especially when SF is between 8 and 11, as stated in the chart aforementioned of R values, where it can be observed that SF combinations are spread over the middle part of the R values chart.

Although this behaviour may seem unusual, it has been observed in previous studies with forest environments, as observed by Ansah et al. [

34], where the authors found higher SF (SF = 11 and 12) values produced less ToA and extended range than the lower SF values from 7 to 9. Our findings corroborate this, as demonstrated in

Figure 8, which presents the average RSSI values found for each parameter in all characterization runs. The characterization results demonstrate SF 9 and 10 produced the best sensitivity values in the forest environment, while transmission power had low impact at the distances tested in the experiments.

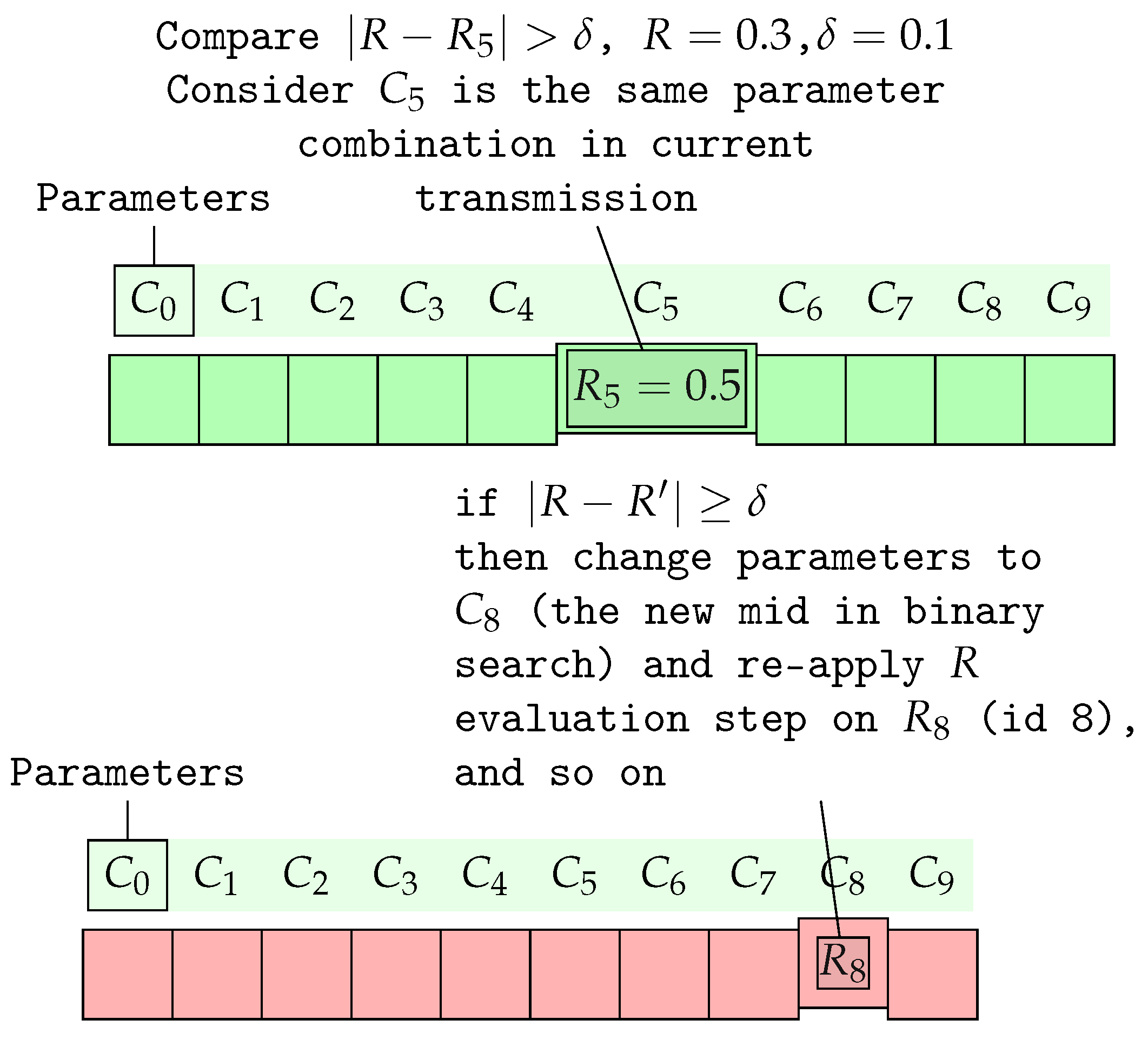

3.3.2. The Binary Search Phase

The algorithm execution comprises three primary steps: the initial step, the R evaluation step, and the optimal LoRa parameter selection step.

In the initial step, the algorithm initiates its process with the DP configuration, as detailed in Sub

Section 3.1. Notably, communication is established before testing the parameter selection. Further, it is worth highlighting that gateways overhear the DP configuration, initiating the LoRa parameter selection binary search algorithm for each newly deployed node.

During the

R evaluation step, after transmitting

N packets from the node to the gateway, the algorithm employs Equation

2 to compare the calculated R to the

R-array. The comparative analysis determines whether the calculated

R for the current parameter combination aligns with empirical results or if parameter modifications are necessary to test and identify a more suitable combination. Thus, if adjustments are required, the configuration is adjusted to the left or right side of the

R-array, using the classic binary search methodology, iterating through packet transmission and assessment until convergence on the appropriate configuration is achieved.

Figure 9 illustrates an instance of the algorithm’s R evaluation step. Suppose the parameter combination in

is the first to be tested. The current

R is calculated following the

R evaluation step using the LoRa parameters (SF, BW, and PT) represented by

, and we compare to its position in the

R-array, denoted in green,

. Suppose

, if the absolute difference

, where

-array and

exceeds

, for instance, and

R is greater than

(it is true in this example), indicating a potentially more suitable parameter combination, the algorithm shifts to the right side of the

R-array using binary strategy. Subsequently, the

R-evaluation step iterates through packet transmission to calculate

R again, as well as the new

in the

R-array for comparison, as depicted in the red

R-array. Moreover, if the difference between the new

and the new

is lower than the

, the algorithm will shift to the left side to search for a more suitable parameter combination since

R is greater than

, so the parameters still can be optimized. The search stops when the absolute difference between

R and

is lower than

or no binary step is available.

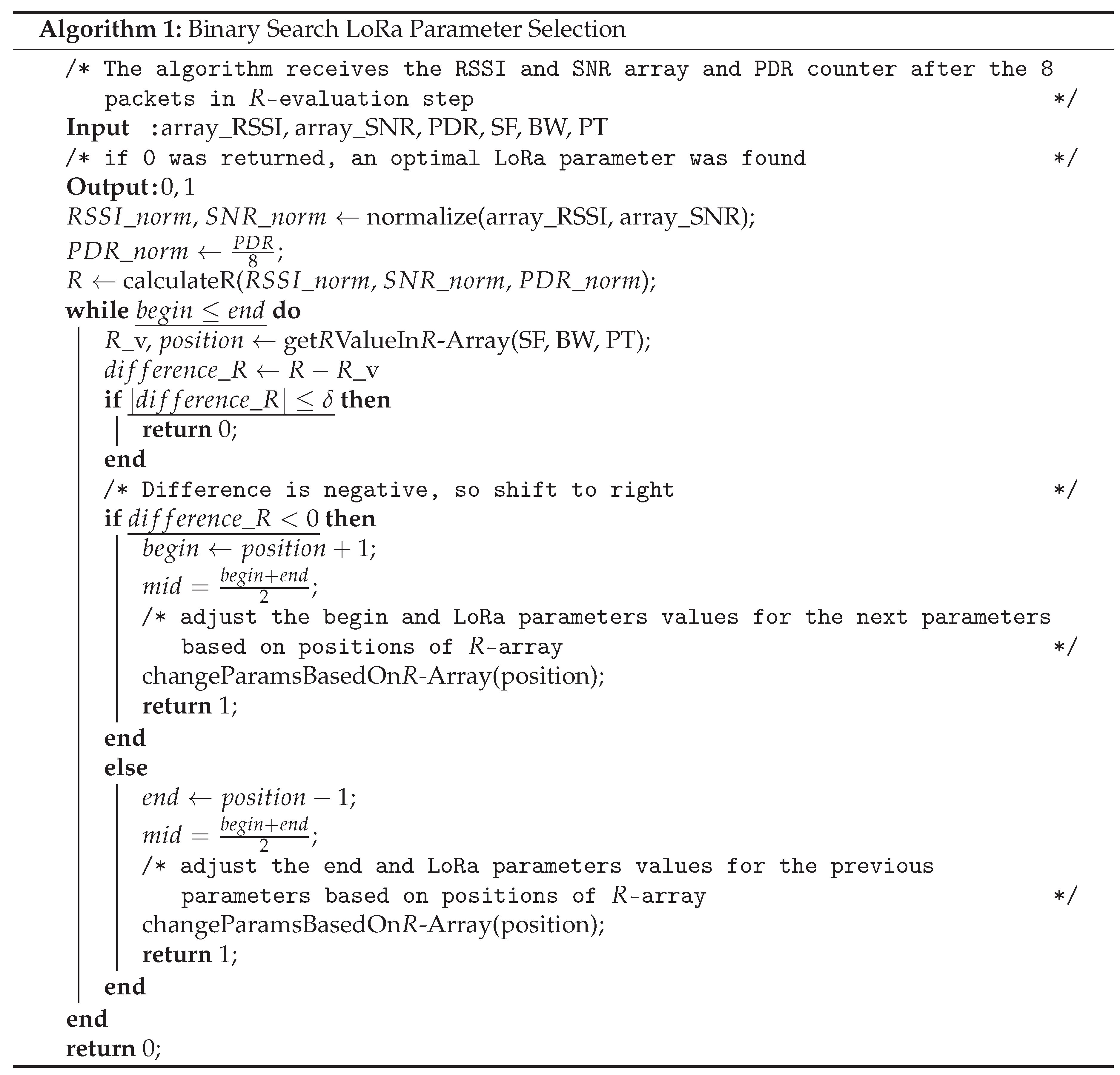

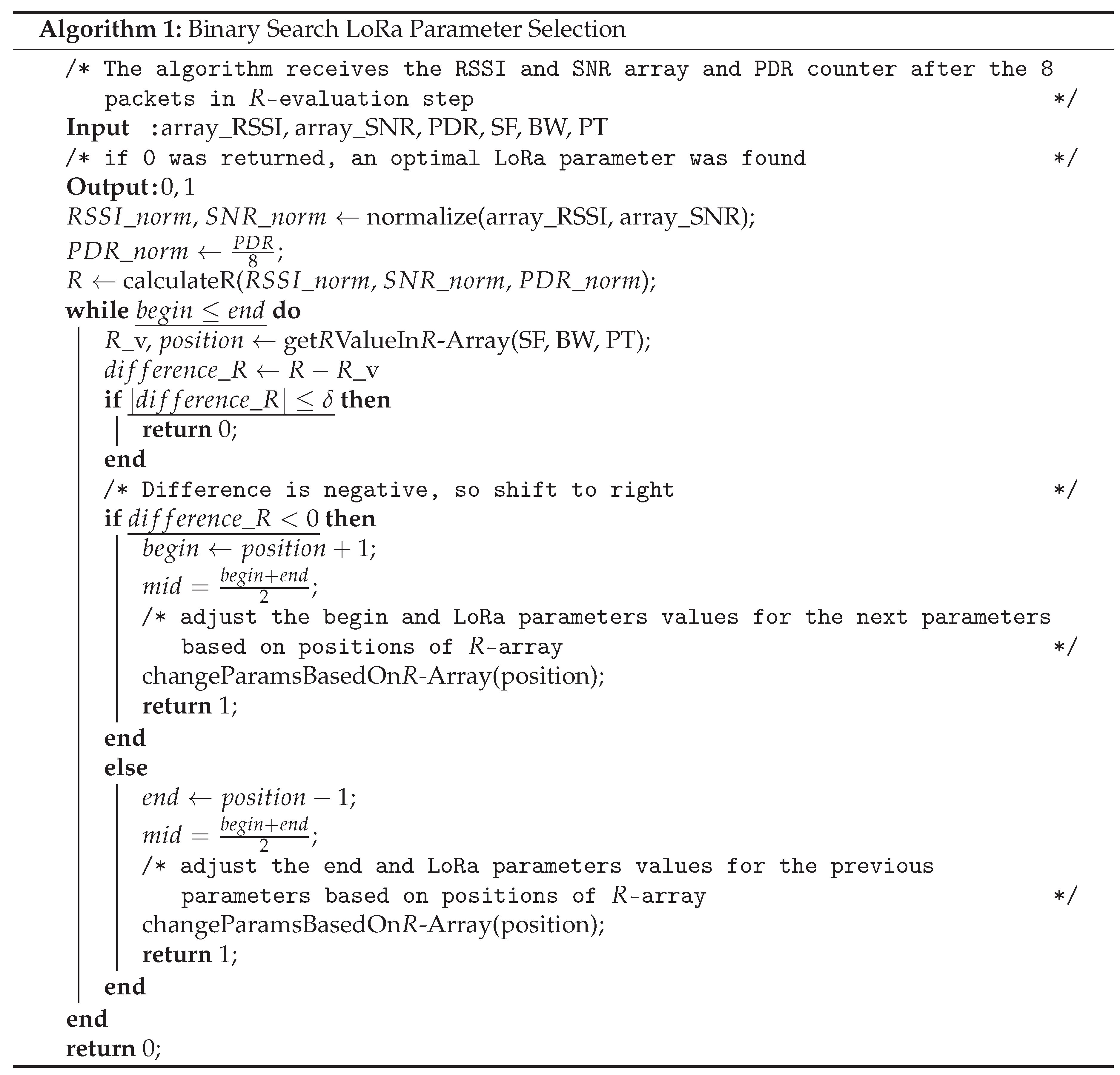

In the final step, if no additional binary search steps are available, or if the difference is less than , the identified optimal LoRa parameter combination is configured as the transmission parameters for the end node. Consequently, standard monitoring and transmission operations of the end node are initiated as usual. The complete and detailed algorithm of the binary search proposed can be seen in Algorithm 1.

4. Design of Experiments

To test the effectiveness of our proposed algorithm, we experimented to compare its performance with the traditional ADR approach. The experiments were conducted in vegetation and climate conditions similar to the experiments used to build the

R-array, described in

Section 3.3.1, except the distance of 187 and 200 meters, respectively. Moreover, each experiment consisted of the initial stage described in

Section 3.1. The decision to use similar scenarios was motivated by the familiarity with the potential outcomes of the characterization experiments. This familiarity facilitated the subjective-qualitative analysis concerning the suitability and comprehensibility of the potential results employed in the phase of

R-array building. The detailed location of validation experiments are illustrated in

Figure 10.

The metrics evaluated were: a) convergence time, representing the duration for the algorithms to select optimal parameters, b) Packet Delivery Ratio, representing the number of packets delivered in a communication after LoRa parameters was selected by proposed algorithm and ADR, and c) qualitative analysis of the chosen parameters.

Weight values were assigned based on the results obtained from the characterization experiments. The weights used for

R calculation were 0.2 for RSSI and SNR and 0.6 for PDR in the equation (Equation

2). The weight choices aim to substantially elevate the significance of PDR by choosing a parameter combination focused on minimizing packet losses.

5. Results

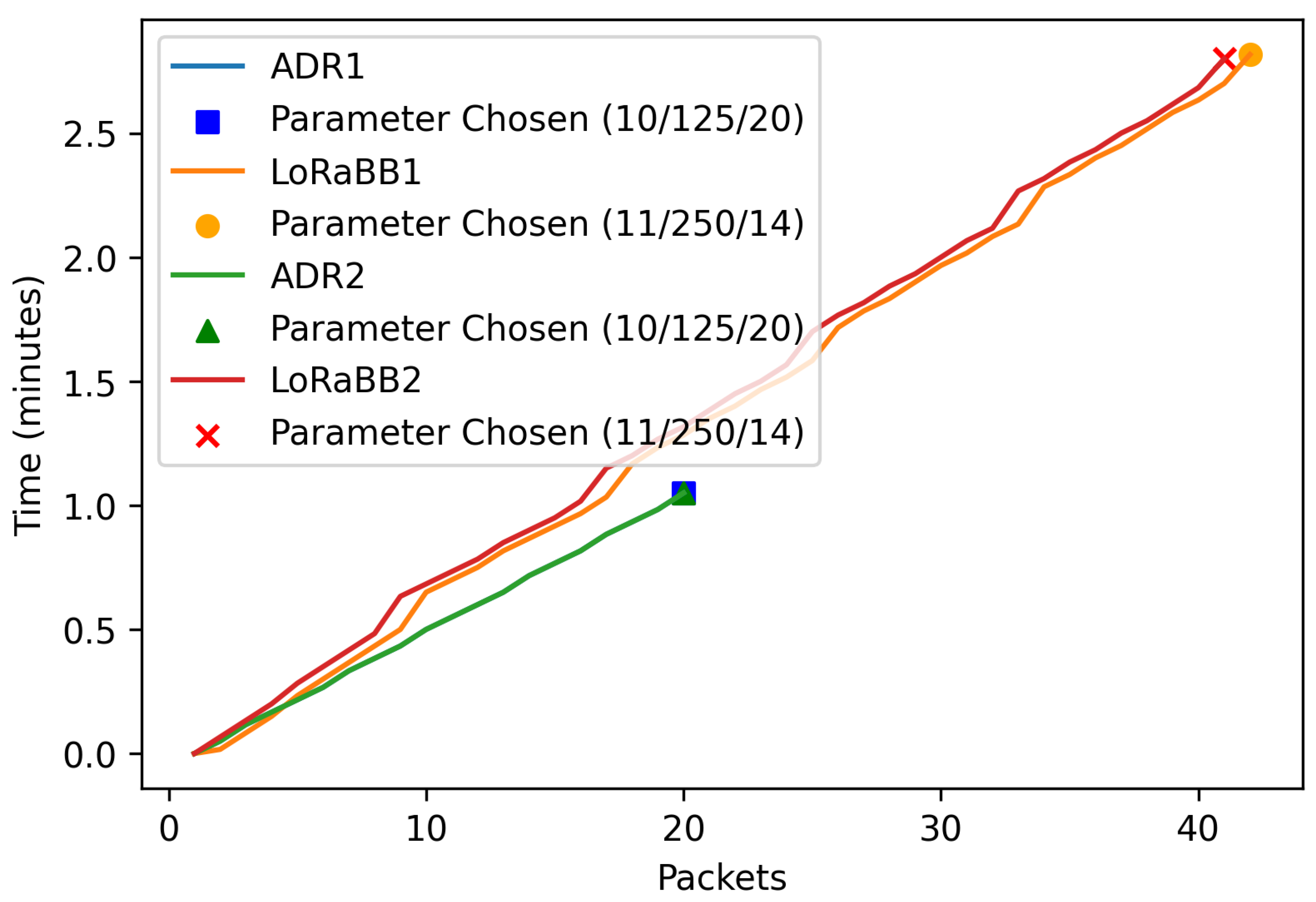

The results evaluated LoRaBB compared to ADR LoRaWAN for the aforementioned devices setup forest transmission conditions. In the following charts, the number following the names ADR and LoRaBB represents the location of experimentation described in the previous section.

The results for convergence time are illustrated in

Figure 11. We observed a minimal difference in convergence time, primarily influenced by two factors: the LoRaBB processing time, as we can observe in the convergence time for approximately 20 packets transmitted by ADR, and 8 packets for LoRaBB. Therefore, the total convergence time of the proposed algorithm was slightly more than double compared to the ADR result due to the number of packets transmitted by LoRaBB, which was slightly more than 40 packets due to the iterations of the binary search.

On the other hand, in the qualitative analysis, the LoRaBB algorithm consistently chose parameters SF = 11, BW = 250, and TP = 14 in both experiments, contrasting with ADR, which assigned SF = 10, BW = 125, and TP = 20. We highlight that in both experiments ADR did not decrease the TP value. Due to foliage across forest, the SNR value, used in ADR, is usually poorer in these environment, which leads the ADR to keep higher TP values.

LoRaBB held an advantage by selecting specific parameters which result in a ToA, compared to ADR result, 206.84 ms and 247.80 ms, respectively

2. As stated by Križanović et al. [

35], ToA is fully related to device energy consumption, where higher ToA implies in more energy consumption by the transmitter device.

The performance evaluation shows LoRaBB can perform similarly to ADR in terms of SF parameter selection. Since higher SF can handle more information on its chirp and consume more device energy consumption, it also can lead to fewer messages sent by day (considering the fair use policies and regulated duty cycle limits) [

35]. Although communication operations involving SF are quite exponential, we believe this does not significantly impact operations related to remote monitoring systems, such as sensor-based monitoring of water quality - the main use case of this research - since there is no requirement for devices to send a large volume of messages daily in such environments.

In addition, as expected, the LoRaBB reached a lower TP when compared to the ADR result. While ADR is not properly indicated for TP parameter selection due to algorithm and scenario properties, LoRaBB can handle TP selection, choosing a TP

in both experiments evaluated. It is worth mentioning that, as stated in [

36], the energy consumption can increase more than 340% when TP goes from 13 to 20 dB considering the Semtech chip datasheet and 38% when TP goes from 17 to 20. The difference found in the literature and chip datasheet support our findings can lead to a minimum device energy consumption.

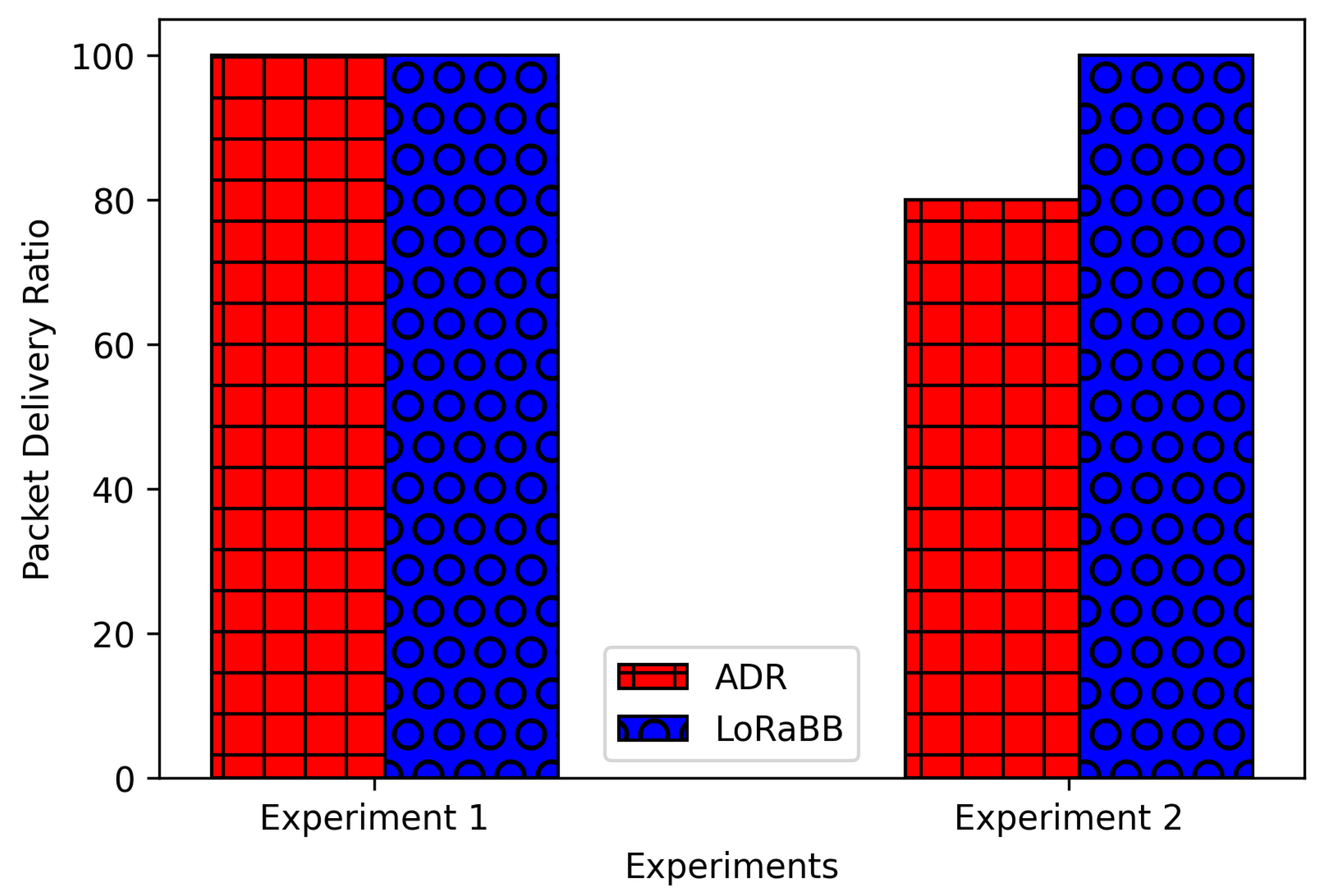

Further, analyzing packet delivery performance, as illustrated in

Figure 12, the ADR had the worst performance on experiment 2, reaching 100% and 80% for each experiment scenario, while LoRaBB performed 100% of PDR in such cases. Even in a scenario of a relevant short distance for LoRa communication, ADR did not reach 100% of PDR.

One of our hypotheses is that, as ADR uses SNR as the basis of its algorithm, SNR was verified to be a metric of minor applicability in forest scenarios, which is corroborated by the investigation by Ansah et al. [

34]. where the authors found the received signal power deviated due to scattering caused by tree trunks and canopy. Moreover, our results follow the theory that higher values of SF had longer ToA and lower minimum receiver sensitivity, as LoRaBB achieved SF

, while ADR

, which could result in the high variance on received signal power found in [

34], impacting the PDR.

Although minimizing the TP value selected for cost-effective deployment in non-critical and non-real-time applications, LoRaBB chosen parameters are preferred due to device energy constraints.

6. Conclusions and Future Remarks

In this work, we introduced a novel algorithm for LoRa parameter selection based on the binary search methodology, entitle LoRaBB. To achieve this, we characterized the communication using a pre-built R-array that identifies the relationship between key parameters (SF, BW, and TP) used in LoRa communication and the major LoRa evaluated metrics for transmission quality: RSSI, SNR, and Packet Delivery Ratio. Further, this characterization was applied and evaluated in forest scenarios with the objective to support environmental monitoring systems.

Our approach calculated the R value, which quantifies each parameter combination based on a performance equation of parameters related to transmission quality. Thus, employing a binary search-based algorithm during the phase of the node’s parameter selection, a suitable parameter combination is obtained. When the R value is near to the value presented on the pre-built R-array for the current parameter combination being tested, these parameters are chosen in the communication.

Our algorithm achieved more energy-efficient parameters than the traditional ADR algorithm and resulted in a lower Time on Air and a lower TP, despite a longer time to find the suitable parameter combination. It also selected more feasible parameters for LoRa communication in forest environments, such as the Amazon rainforest, for extending the device’s lifespan in IoT monitoring scenarios with strict data transmission time constraints, such as monitoring water quality in the Amazon rainforest and other monitoring scenarios in forest environments.

According to our research, using a not suitable LoRa communication parameter for remote monitoring in non-critical and non-real-time applications in the Amazon rainforest can significantly decrease the energy cost for devices. Combined with the logistical cost of deploying end devices in regions of the Amazon rainforest, this can increase the overall cost of the monitoring architecture. We therefore conclude our approach can reduce other device-related expenses due to the self-healing and self-configuration settings presented in our work.

On the other hand, the long-range capabilities and gateway configurations for managing multiple devices with different LoRa parameters emerge as a new issue in this context. In the next step, we intend to analyze environmental factors in such scenarios and how LoRa parameter selection algorithms can handle these situations. Furthermore, we plan to increase this study by deploying nodes on lakes and water bodies on the university campus. Finally, we intend to evaluate the performance by comparing it to novel machine learning approaches for LoRa parameter selection in real scenarios.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.S.M and E.M.; methodology, D.S.M.; software, P.B.S. and P.V.F.M.; validation, D.S.M., G.S. and E.M.; formal analysis, A.E.Y.; investigation, D.S.M. and A.E.Y.; resources, E.M.; data curation, D.S.M., G.S. and A.E.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, D.S.M.; writing—review and editing, D.S.M., G.S., A.E.Y. and E.M.; supervision, E.M.; project administration, D.S.M. and E.M.; funding acquisition, E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research, carried out within the scope of the Samsung-UFAM Project for Education and Research (SUPER), according to Article 39 of Decree n°10.521/2020, was funded by Samsung Electronics of Amazonia Ltda., under the terms of Federal Law n°8.387/1991 through agreement 001/2020, signed with UFAM and FAEPI, Brazil.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LoRa |

Long Range |

| TP |

Transmission Power |

| BW |

Bandwidth |

| SF |

Spreading Factor |

| CR |

Coding Rate |

| ADR |

Adaptive Data Rate |

| ToA |

Time on Air |

| RSSI |

Received Signal Strength Indicator |

| SNR |

Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| PDR |

Packet Delivery Ratio |

References

- de Souza, J.R.; de Moraes, M.E.B.; Sonoda, S.L.; Santos, H.C.R.G. A importância da qualidade da água e os seus múltiplos usos: caso Rio Almada, sul da Bahia, Brasil. REDE-Revista Eletrônica do Prodema 2014, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Rico, A.; de Oliveira, R.; de Souza Nunes, G.S.; Rizzi, C.; Villa, S.; López-Heras, I.; Vighi, M.; Waichman, A.V. Pharmaceuticals and other urban contaminants threaten Amazonian freshwater ecosystems. Environment International 2021, 155, 106702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Filho, E.A.; Alves, S.B.d.S.M.; Neves, R.K.R.; Batista, I.H.; de Albuquerque, C.C.; Damasceno, S.B.; do Nascimento, D.A. Estudo comparativo de aspectos físico-químicos entre águas da microbacia do mindu e igarapés sob influência antrópica na cidade de Manaus-AM/Comparative study of physicochemical aspects between mindu microbacy waters and igarapes under anthropic influence in Manaus-AM city. Brazilian Journal of Development 2020, 6, 2419–2433. [Google Scholar]

- Das, B.; Jain, P. Real-time water quality monitoring system using Internet of Things. 2017 International conference on computer, communications and electronics (Comptelix). IEEE, 2017, pp. 78–82.

- Pasika, S.; Gandla, S.T. Smart water quality monitoring system with cost-effective using IoT. Heliyon 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.; Hao, X.; Lu, J.; Yan, K.; Liu, J.; He, C.; Xu, X. Research and design of distributed IoT water environment monitoring system based on LoRa. Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing 2021, 2021, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almuhaya, M.A.M.; Jabbar, W.A.; Sulaiman, N.; Abdulmalek, S. A Survey on LoRaWAN Technology: Recent Trends, Opportunities, Simulation Tools and Future Directions. Electronics 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoRa modulation basics, 2015. Acessed december 2023.

- Bor, M.; Roedig, U. LoRa transmission parameter selection. 2017 13th International Conference on Distributed Computing in Sensor Systems (DCOSS). IEEE, 2017, pp. 27–34.

- Sugiyama, S.; Makizoe, K.; Arai, M.; Hasegawa, M.; Otsuki, T.; Li, A. Fully Autonomous Distributed Transmission Parameter Selection Method for Mobile IoT Applications Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. 2024 IEEE 99th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2024-Spring). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–5.

- Rašić, T.; Simon, J.L.E.; Zorić, N.; Simić, M. The Impact of LoRa Transmission Parameters on Packet Delivery and Dissipation Power. 2021 International Balkan Conference on Communications and Networking (BalkanCom). IEEE, 2021, pp. 11–15.

- Polidori, L.; Caldeira, C.R.T.; Smessaert, M.; Hage, M.E. Digital elevation modeling through forests: the challenge of the Amazon. Acta Amazonica 2022, 52, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida-Correa, T.; Frazao, L.; Costa, D.M.; Menin, M.; Kaefer, I.L. Effect of environmental parameters on squamate reptiles in an urban forest fragment in central Amazonia. Acta Amazonica 2020, 50, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Cao, Z. Lora networking techniques for large-scale and long-term iot: A down-to-top survey. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2022, 55, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, A.; Kuzminykh, I.; Franksson, R.; Liljegren, A. Measuring a LoRa network: Performance, possibilities and limitations. Internet of Things, Smart Spaces, and Next Generation Networks and Systems: 18th International Conference, NEW2AN 2018, and 11th Conference, ruSMART 2018, St. Petersburg, Russia, August 27 –29, 2018, Proceedings 18. Springer, 2018, pp. 116–128.

- Sarker, V.K.; Queralta, J.P.; Gia, T.N.; Tenhunen, H.; Westerlund, T. A survey on LoRa for IoT: Integrating edge computing. 2019 Fourth International Conference on Fog and Mobile Edge Computing (FMEC). IEEE, 2019, pp. 295–300.

- Ojo, M.O.; Adami, D.; Giordano, S. Experimental evaluation of a LoRa wildlife monitoring network in a forest vegetation area. Future Internet 2021, 13, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Pei, P.; Pan, R.; Wu, K.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Yang, J. A collision reduction adaptive data rate algorithm based on the fsvm for a low-cost lora gateway. Mathematics 2022, 10, 3920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, P.; Montavont, J.; Noel, T. Indoor deployment of low-power wide area networks (LPWAN): A LoRaWAN case study. 2016 IEEE 12th international conference on wireless and mobile computing, networking and communications (WiMob). IEEE, 2016, pp. 1–8.

- Kartakis, S.; Choudhary, B.D.; Gluhak, A.D.; Lambrinos, L.; McCann, J.A. Demystifying low-power wide-area communications for city IoT applications. Proceedings of the Tenth ACM International Workshop on Wireless Network Testbeds, Experimental Evaluation, and Characterization, 2016, pp. 2–8.

- Cattani, M.; Boano, C.A.; Römer, K. An experimental evaluation of the reliability of lora long-range low-power wireless communication. Journal of Sensor and Actuator Networks 2017, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Du, W.; Zhao, Z.; Min, G.; Singhal, M. Towards energy-fairness in lora networks. 2019 IEEE 39th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS). IEEE, 2019, pp. 788–798.

- Angrisani, L.; Arpaia, P.; Bonavolontà, F.; Conti, M.; Liccardo, A. LoRa protocol performance assessment in critical noise conditions 2017. pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- The Things Network. LoRaWAN Adaptive Data Rate, 2023.

- Serati, R.; Teymuri, B.; Anagnostopoulos, N.A.; Rasti, M. ADR-Lite: A Low-Complexity Adaptive Data Rate Scheme for the LoRa Network. 2022 18th International Conference on Wireless and Mobile Computing, Networking and Communications (WiMob), 2022, pp. 296–301. [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, G.G.M.; Souza, R.D.; Montez, C.; Hoeller, A. LoRaWAN Adaptive Data Rate With Flexible Link Margin. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2021, 8, 6053–6061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifeh, A.; Shraideh, S.; Darabkh, K.A. Joint Channel and Spreading Factor Selection Algorithm for LoRaWAN Based Networks. 2020 International Conference on UK-China Emerging Technologies (UCET), 2020, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Filho, M.C.; Campista, M. Economia de Energia através da Configuração Inteligente de Parâmetros de Camada Física em Redes LoRa. Anais do XL Simpósio Brasileiro de Redes de Computadores e Sistemas Distribuídos; SBC: Porto Alegre, RS, Brasil, 2022; pp. 559–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yatagan, T.; Oktug, S. Smart Spreading Factor Assignment for LoRaWANs. 2019 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), 2019, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Ilahi, I.; Usama, M.; Farooq, M.O.; Umar Janjua, M.; Qadir, J. LoRaDRL: Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Adaptive PHY Layer Transmission Parameters Selection for LoRaWAN. 2020 IEEE 45th Conference on Local Computer Networks (LCN), 2020, pp. 457–460. [CrossRef]

- LoRaWAN - simple rate adaptation recommended algorithm, 2016. Acessed december 2023.

- Corporation, S. LoRaWAN—Simple Rate Adaptation Recommended Algorithm, 2016.

- Demetri, S.; Zúñiga, M.; Picco, G.P.; Kuipers, F.; Bruzzone, L.; Telkamp, T. Automated estimation of link quality for LoRa: A remote sensing approach. Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Information Processing in Sensor Networks, 2019, pp. 145–156.

- Richardson Ansah, M.; Sowah, R.A.; Melià-Seguí, J.; Katsriku, F.A.; Vilajosana, X.; Owusu Banahene, W. Characterising foliage influence on LoRaWAN pathloss in a tropical vegetative environment. IET Wireless Sensor Systems 2020, 10, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Križanović, V.; Grgić, K.; Spišić, J.; Žagar, D. An Advanced Energy-Efficient Environmental Monitoring in Precision Agriculture Using Lora-Based Wireless Sensor Networks 2023.

- Bouguera, T.; Diouris, J.F.; Chaillout, J.J.; Jaouadi, R.; Andrieux, G. Energy Consumption Model for Sensor Nodes Based on LoRa and LoRaWAN. Sensors 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).