1. Introduction

In the 21st century, air conditioning has become a necessity rather than a luxury. In hot, humid regions, people rely on air conditioning to alleviate the effects of high temperatures and maintain thermal comfort indoors, to reduce heat-related health risks (such as heat stroke, heat syncope), especially among vulnerable groups [

1,

2,

3].

However, the widespread use of air-conditioners has a significant impact on global energy consumption. According to a report from the International Institute of Refrigeration (IIR), the refrigeration and air-conditioning (RAC) sector already consumes approximately 20 % of the world's total electricity, and space cooling alone accounts for over 8 % of worldwide electricity usage [

4]. Under the International Energy Agency (IEA) “Baseline Scenario,” space cooling alone has the potential to triple electricity demand, and IIR further projects electricity consumption to more than double by 2050 [

5]. This is largely due to rising AC ownership in emerging economies (India, China, Indonesia) and hotter ambient temperatures [

5] In addition, the escalating rate in the world economy predicts a 2% to 3% yearly increment in electricity demand by 2030 [

6].

Globally, the mechanical vapour compression (MVC) systems are the prevalent refrigeration and air conditioning (RAC) systems employed for cooling. MVC systems require a high quality of energy to run the compressor and initiate the cooling process (Moran, 2014; Yunus Cengel, 2014) and typically use HFC/HCFC refrigerants with high ozone-depletion and global-warming potential [

7,

8]. Current sector emissions from the refrigeration and air conditioning (RAC) account for 4.14 GtCO2eq, representing 7.8% of total global GHG emissions [

9]. Without intervention, RAC-related CO₂ emissions are estimated to double due to their significant environmental footprint, with 63% stemming from indirect power-sector emissions and 37% global-warming impact from direct refrigerant leakages [

4].

While increasing SEER standards provides some mitigations to enhance the efficiency of MVC systems, many air conditioners currently available operate at only one-third of the efficiency of the best available technology, leaving the remaining two-thirds underutilized [

5]. These drawbacks of MVC systems and energy issues highlight the pressing requirement for a more radical, energy-efficient, and sustainable cooling alternative.

The adsorption cooling chiller is the most promising technology alternative to conventional high-energy-consuming MVC systems. Adsorption chillers, particularly multi-bed configurations, have emerged as a promising solution. They are entirely or partly powered by low-grade energy sources like waste heat from industries, solar, biomass, etc., for heating and cooling applications [

8], offering advantages such as the utilization of environmentally benign refrigerants [

10], durability, quiet operation, lower energy demands and use of simple controls Also, adsorption cooling systems can harness low-grade heat sources such as waste heat (which is usually discharged into the environment) or solar power (which is renewable) as heat sources, making them environmentally friendly [

11].

Despite growing interest, suboptimal performance indicators like low Coefficient of Performance (COP), Specific Cooling Power (SCP) and sensitivity to operational parameters like variations in temperature, flow rates, and working fluids have held back wide-scale deployment of ADC.

Addressing these hurdles requires a robust approach to optimize the performance of single-stage dual-bed adsorption chillers and potentially extend the findings to complex bed adsorption chillers in the future.

Optimization techniques like single and multi-objective optimization employing advanced algorithms to investigate parametric interactions systematically can serve as potential approaches to enhance performance metrics and design criteria of adsorption chillers. Optimisation techniques are methods for finding optimal designs using computational approaches, and multi-objective optimisation deals with problems with more than one objective, where multiple solutions exist due to the conflicting nature of these objectives. Consequently, engineering problems encountered in real-life scenarios are usually multi-objective and fit the scope of multi-objective optimisation applications [

12].

Multi-Objective Optimization is crucial in engineering applications like adsorption chillers and allows for the simultaneous consideration of multiple objectives, leading to a set of optimal solutions that represent various trade-offs between competing goals. Multi-objective optimization requires specific approaches: a priori, a posteriori, and progressive methods. A priori combines objectives into a single objective, while a posteriori maintains a multi-objective formulation.

Advancements in optimization algorithms include Mirjalili’s [

12] improvement of multi-objective challenges in engineering by enhancing the Ant Lion Optimizer (ALO) to create the Multi-Objective Ant Lion Optimizer (MOALO) as a promising alternative to tackle a wide range of optimization challenges. Nadimi-Shahraki et al [

13] also developed a novel variant of the grey wolf optimizer (GWO), referred to as the gaze cues learning-based grey wolf optimizer (GGWO). Application of GGWO to various engineering optimization problems showed its practical applicability in real-world scenarios against several benchmark functions and other optimization algorithms, demonstrating its superior efficiency and effectiveness. Krzywanski

et al. [

14] provided valuable insight into optimizing energy conversion by using genetic algorithms and artificial neural networks to create a non-iterative model that optimizes cooling capacity under varying load conditions for a Tri-bed twin-evaporator adsorption chiller. This novel approach helped identify optimal parameters that used low-temperature heat sources to effectively maximize the ADC's cooling output. This optimized model can serve as a useful tool for engineers when integrated into multigeneration systems to provide a quick and effective means of optimization without the need for extensive empirical experiments. Thus, making it a viable option for more complex numerical and analytical methods. Modifications in control software, such as changes in the sequence of switching valves, optimization of switching and cycle allocation, were reported to significantly improve COP by enabling heat recovery and mass regeneration. Interestingly, these changes can be implemented without altering the hardware, making them a cost-effective solution for the performance enhancement of adsorption chillers. Also, the overall stability of the system and lifespan of the chiller's operational qualities, like vibrations and noise improved after the modifications [

15,

16] . Furthermore, longer adsorption and desorption cycle times significantly improved the ADC's COP and cooling capacity, whereas switching times showed less impact on performance [

16]. Another nature-inspired meta-heuristic optimization algorithm is the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) proposed by Mirjalili and Lewis in 2016 [

17]. The WOA’s performance was validated and benchmarked on six engineering design problems and twenty-nine optimization test functions.

These insights illustrate how optimization algorithms have been progressively adapted to meet the diverse needs of various engineering fields. As highlighted in this section, the evolution of optimization algorithms underscores their broad applicability across various engineering domains. Therefore, employing these algorithms in optimization of ADCs can extend the operational life and stability of the ADC system.

Although the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO), a nature-inspired metaheuristic, is widely applied in various optimisation contexts, it remains unexplored in the design, configuration, and operational optimisation of a single-stage dual-bed adsorption chiller. This study employs GWO to demonstrate the algorithm's efficacy in improving the coefficient of performance (COP), cooling capacity (Qcc), and waste heat recovery efficiency, and offers a comparative analysis of hand-tuned parameter sets against single-objective GWO and its multi-objective approach, MOGWO.

A handful of optimization techniques are displayed in Figure 1 [

18] Meta-heuristic algorithms fall into five categories: swarm intelligence-based algorithms, bio-inspired algorithms, evolutionary algorithms, nature-inspired algorithms, and physics-based algorithms. Genetic Algorithm (GA) proposed by Holland [

19] in 1992, it is the most recognised evolutionary class of algorithms, which was justified in Darwin’s evolution theory. This GA was used in real-world control system optimization by [

20]. Other examples of evolutionary algorithms are Genetic Programming (GP), Differential Evolution (DE) [

21], Biogeography-Based Optimizer (BBO) [

22], Evolutionary Programming (EP) [

23]. Artificial Immune System, Bacterial Foraging Optimization (BFO) and others are part of bio-stimulated algorithms [

18]. GWO [

24] falls under the swarm intelligence-based algorithms and is inspired by the social dominant hierarchy of grey wolves and their social hunting mechanism, like the intelligent behaviour of the other “swarms” under the swarm-based intelligence group, like the particle swarm [

25] which is one of the commonly used optimizations, the Ant colony [

18], Cuckoo search [

26] and Firefly algorithms [

27].

Adsorption cooling systems have been researched and proposed as a promising alternative to fossil fuel-consuming, high electrical energy-demanding VCSs.

Appraisals from the International Institute of Refrigeration in Paris have shown that refrigeration and air conditioning processes alone consume 20% of commercial and household energy. In contrast, only 80% of the total electricity generated worldwide is used for other electricity-demanding processes. These figures emphasise the urgent need for a sustainable alternative, such as ADCs capable of offsetting the significant global warming, ozone-depleting, and energy-intensive MVC paradigm [

9].

Replacing even 50% of the current sales of MVC units with ADC systems could significantly save carbon credits and reduce energy consumption [

28]. Among the modes of operation of adsorption processes, fixed-bed adsorption is the most employed. It could be only one bed or a combination of several adsorption/desorption beds in a complex system to increase the COP [

29,

10].

The single-stage, dual-bed adsorption chiller (ADC) is the most common basic laboratory-scale configuration. A major advantage of the single-stage, dual-bed configuration over the other bed fixtures is its ability to produce a continuous cooling effect [

30].

Nevertheless, many variations of the basic ADC have been developed, studied and proposed to improve the performance of the adsorption chiller [

31]. Multibed systems have been reported to reduce temperature fluctuations in the chilled water outlet and improve the usage of waste heat for waste heat ADCs [

32,

33,

34,

35]. Adding heat and mass recovery processes to the ADC has also been shown to improve the COP and cooling capacity of the ADC [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41].

Table 1 summarises recent studies on two-bed, three-bed, and recovery-enhanced adsorbers, highlighting key performance indicators (KPIs).

Adsorption is a surface phenomenon that usually occurs between solid phases and gases in cooling applications. Certain solid phases (e.g., porous solids like clay, silica gel, etc.) can attract gas molecules onto their surfaces. Such solids are referred to as adsorbents, and the gas molecules they adsorb or surfaces on which adsorption occurs are termed adsorbates [

50]. The adsorption process is exothermic, so energy is released during the process; thus, continuous cooling of the adsorbent bed is required during the adsorption process to remove the heat of adsorption. On the other hand, desorption is the process of removing adsorbents from the exterior of an adsorbate. It involves the application of heat to desorb the adsorbate from the surface of the adsorbent either by a reduction in pressure or an increment in temperature [

7].

Silica gel is frequently employed as an adsorbent in ADCs due to its low desorption temperature, affordability, and environmentally friendly nature [

51,

52]. Also, it has an expansive specific surface area, which makes it effective at capturing substantial volumes of refrigerant vapour [

53]. Water is the common refrigerant used in ADCs, due to its high latent heat and the self-evident environmental benefits. Therefore, the silica gel/water working pair is widely used for commercial, numerical and experimental studies of ADCs [

54,

55,

56]. Zeolite/water [

57], activated carbon/ethanol, activated carbon/methanol pairs, composites [

58,

59], selective water sorbents (SWS)–water [

60,

61] and Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [

62,

63] are other alternative adsorbent/adsorbate working pairs for ADCs.

Single-stage dual-bed ADCs typically use silica gel-water pairs due to their compatibility with low-temperature heat sources, such as waste heat below 100°C. Parameters like cycle time and heat exchanger capacity can be adjusted to optimize the performance of such ADCs [

42,

64].

Metaheuristics are high-level, stochastic global search techniques that can efficiently find good solutions in combinatorial optimization to find a range of feasible solutions, leveraging advanced optimisation methods [

65]. Metaheuristic optimization of single-stage dual-bed adsorption chillers using waste heat is a promising approach to improve the efficiency and performance of cooling systems that use low-grade thermal energy

There have been many applications of metaheuristic optimization in different areas of the operation of adsorption chillers. A metaheuristic framework using particle swarm optimization (PSO) for material screening and operating optimization of adsorption-based heat pumps was proposed to evaluate different operation temperature intervals with emphasis on minimizing heat supply cost while maximizing performance to identify optimal temperature sets and adsorbents. Results showed a quick and intuitive assessment of multiple operation variables and design [

66].

Genetic algorithms and neural networks have been shown to provide a non-iterative technique that yields fast and precise results to optimize the overall performance and cooling capacity of ADCs with a maximum relative error of less than ±10% between measured and calculated data. Such approaches are most suitable for studying the operating parameters on the cooling capacity of complex systems like tri-bed twin-evaporator chillers [

67]

A global optimization method, like the particle swarm optimization was used to determine the optimum cycle time for a single-stage ADC, improving both the COP and specific cooling capacity [

68]. Also, the augmented group search optimization (AGSO) algorithm was used to optimize the loading of multi-chiller plants. Higher convergence speed corresponded to lower energy consumption by avoiding local minima and addressing the hurdles of conventional group search optimization methods [

69].

An improved nature-inspired firefly algorithm (IFA) performed better than the conventional method in minimizing the energy consumption of a multi-chiller system when it was applied to optimize chiller loading. Based on the characteristics of fireflies, the partial loading ratio of each chiller was optimized to improve energy conservation [

70].

Factors such as heat exchanger parameters and adsorbent mass allocation can significantly impact the cooling capacity of ADCs. A study by Khan et al and Farid et al confirms the positive influence of optimization in improving cooling capacity [

71,

72].

For performance and efficiency, factors such as adsorbent mass allocation and heat exchanger parameters influence the cooling capacity of these systems. Optimising these factors can significantly improve cooling capacity, as demonstrated in various studies [

73,

74].

The COP and cooling capacity showed significant improvement when the ratio between the allocation of adsorption/desorption cycle times was optimised for a two-bed silica gel/water-based chiller [

75].

To understand the impact of adsorbent characteristics on chiller performance, dynamic investigations on methanol adsorption in loose grain configurations and compact adsorbent layers were optimized to increase the effectiveness and speed of the adsorption process [

76].

Theoretical investigations into the allocation of adsorption and desorption cycle times have shown that optimising the ratio between these modes can significantly improve system performance in terms of cooling capacity and coefficient of performance (COP). For instance, a two-bed silica gel/water-based chiller demonstrated improved performance by reducing the ratio of desorption to adsorption times [

77].

For material and working fluid selection, optimal methanol-MOF pairs for adsorption-driven heat pumps and chillers were identified through high-throughput computational screening of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), which enabled the selection of suitable working fluids and adsorbents to enhance the coefficient of performance (COP) and working capacity. High-throughput computational screening of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) has been used to identify optimal methanol-MOF pairs for adsorption-driven heat pumps and chillers. This approach helps in selecting promising adsorbents and suitable working fluids, enhancing the system's working capacity and COP [

75].

Furthermore, recent studies have explored the optimization of single-stage two-bed adsorption chillers, which can utilize low-grade waste heat or solar energy for cooling applications. Researchers have developed lumped parameter models to analyze and optimize chiller performance, considering factors such as cycle time, adsorbent thickness, and operating temperatures [

78,

79].

Advanced optimization approaches have been proposed, including simultaneous optimization of operational and material parameters [

80] and the use of artificial neural networks for performance prediction and optimization [

81]. These studies have focused on improving key performance indicators such as cooling capacity (CC) and coefficient of performance (COP). For instance, an optimum cooling capacity of 5.95 kW was reported for an optimized two-bed silica gel–water ADC [

82]. Also, a three-bed adsorption chiller yielded an enhanced maximum cooling capacity of 12.7 kW and a COP of 0.65 through optimization of the chiller by genetic algorithms and neural networks [

14].

Despite the numerous advances in metaheuristic optimization, most optimizations are targeted at enhancing the thermodynamic cycle-time allocations, material selection, and multi-bed configurations, with a few on the simultaneous optimization of all key decision variables (temperatures, mass flows, UA’s) for a single-stage dual-bed ADC under low-grade waste-heat applications [

80,

82]. Therefore, there remains a lack of comprehensive multi-objective optimization frameworks that:

Simultaneously optimize COP, Qcc, and waste-heat recovery efficiency (ηₑ) in a single-stage dual-bed silica-gel/water ADC,

Validate decision variables (inlet temperatures, mass flows, UA’s) against experimentally supported ranges, and

Perform sensitivity analysis on reciprocal-transformed objectives to ensure thermodynamic realism across the operating window.

To address this gap, the present study will:

Develop a novel MOGWO-based approach for optimizing a single-stage dual-bed adsorption chiller.

Optimize the Coefficient of Performance (COP), cooling capacity (Qcc), and waste heat recovery efficiency (ηₑ).

Conduct a one-at-a-time (OAT) sensitivity analysis to quantify how key decision variables influence each objective.

2. Materials and Methods

The single-stage dual-bed ADC described in this paper is according to the study by Papoutsis et al [

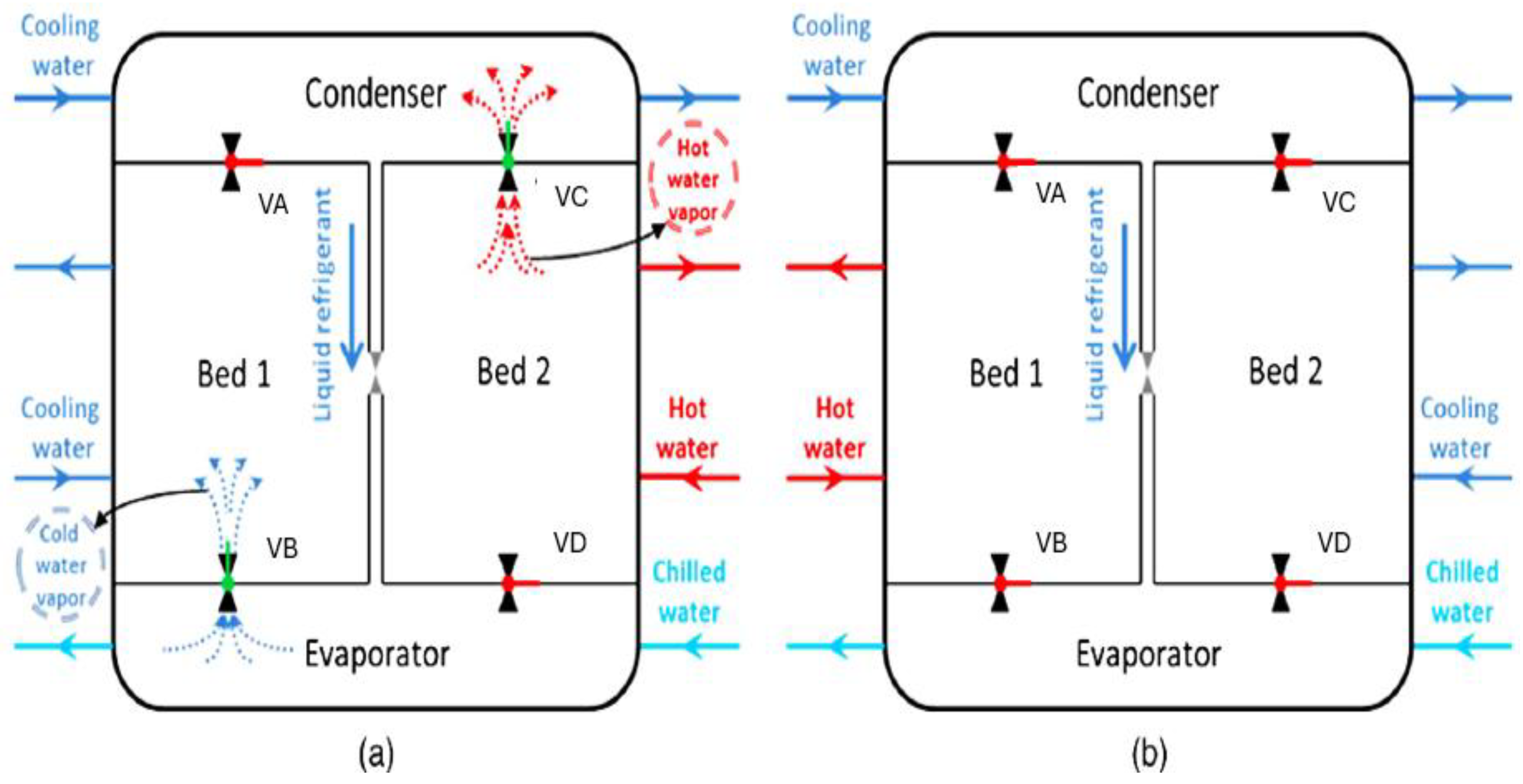

83]. The main components, as shown in

Figure 2, are an evaporator, two adsorbent beds, and a condenser. The condenser and evaporator are connected to the adsorbent by valves (VA–VD), and the adsorbent beds are the fin and tube heat exchangers with adsorbent materials packed between their fins to improve heat exchange.

In Mode A, valves VA and VD are closed, and VB and VC remain open. Adsorbent Bed 1 connects with the evaporator to initiate the adsorption-evaporation process. The chilled water supplies heat to the adsorbate (water) to boil in the evaporator at a low pressure while reducing the temperature. This causes adsorption of the refrigerant vapours from Bed 1. Heat rejected during the adsorption process is sent to the cooling water circuit. Simultaneously, the desorption-condensation process also happens in Bed 2 and the condenser. Heat is supplied to Bed 2 to desorb the refrigerant collected in the adsorbent material, sending the heat of condensation to the cooling water circuit. Modes A and B can alternate as an adsorber or desorber according to the opening and closing of the valves and pressure gains or losses.

Based on the system description in

Figure 2 and

Section 3.1, the three linear regression equations used as objective functions for the single-stage dual-bed adsorption chiller are as follows:

Maximise COP: For adsorption cycles, COP is a key performance indicator calculated by estimating the cooling and heating within the evaporator and condenser, respectively. The formula for the chiller's COP can be expressed as in equation (1) [

64].

= half cycle time

= chilled water mass flow rate

= specific heat capacity of water

= chilled water inlet temperature

= chilled water outlet temperature

= hot water inlet temperature

= hot water outlet temperature

The linear regression equation of COP for the single-stage dual-bed ADC is shown in equation 2, according to [

83] as:

with adjusted

where,

= cooling water inlet temperature

= mass flow rate of hot water

= cooling water mass flow rate of bed

= cooling water mass flow rate of condenser

= adsorbent bed overall thermal conductance

= evaporator overall thermal conductance

= condenser overall thermal conductance

- 2.

Maximize Cooling Capacity (

): Cooling capacity is another primary indicator of adsorption chiller performance. Qcc is defined in equation 3 as [

16]:

The linear regression representation of Qcc for the single-stage dual-bed ADC is defined according to [

84] as equation 4:

with adjusted

- 3.

Maximize waste heat recovery efficiency (

): Effective heat recovery strategies are pivotal in enhancing the efficiency of ADCs, and heat recovery is shown to influence the overall system performance [

85]. Thus,

is defined as a performance indicator for the single-stage dual-bed adsorption chiller according to [

84] by equation 5:

The regression equation for

is represented by equation 8 [

84] as:

With adjusted

Based on the objective functions from equations (2), (4) and (6), the decision variables and bounds are presented in

Table 2.

These decision variables are selected based on their coefficients [

79]. A glance at the adjusted R

2 values of

for COP,

for Qcc and

for

described in the regression analysis equations for the selected decision variables, suggest that the selected equations provide a good fit for the data. Comparatively, the high adjusted R-squared values across all three objective functions (COP, Qcc, and ηe) confirm the suitability of the chosen equations for modelling the relationships between the variables.

2.1. Greywolf Optimization (GWO)

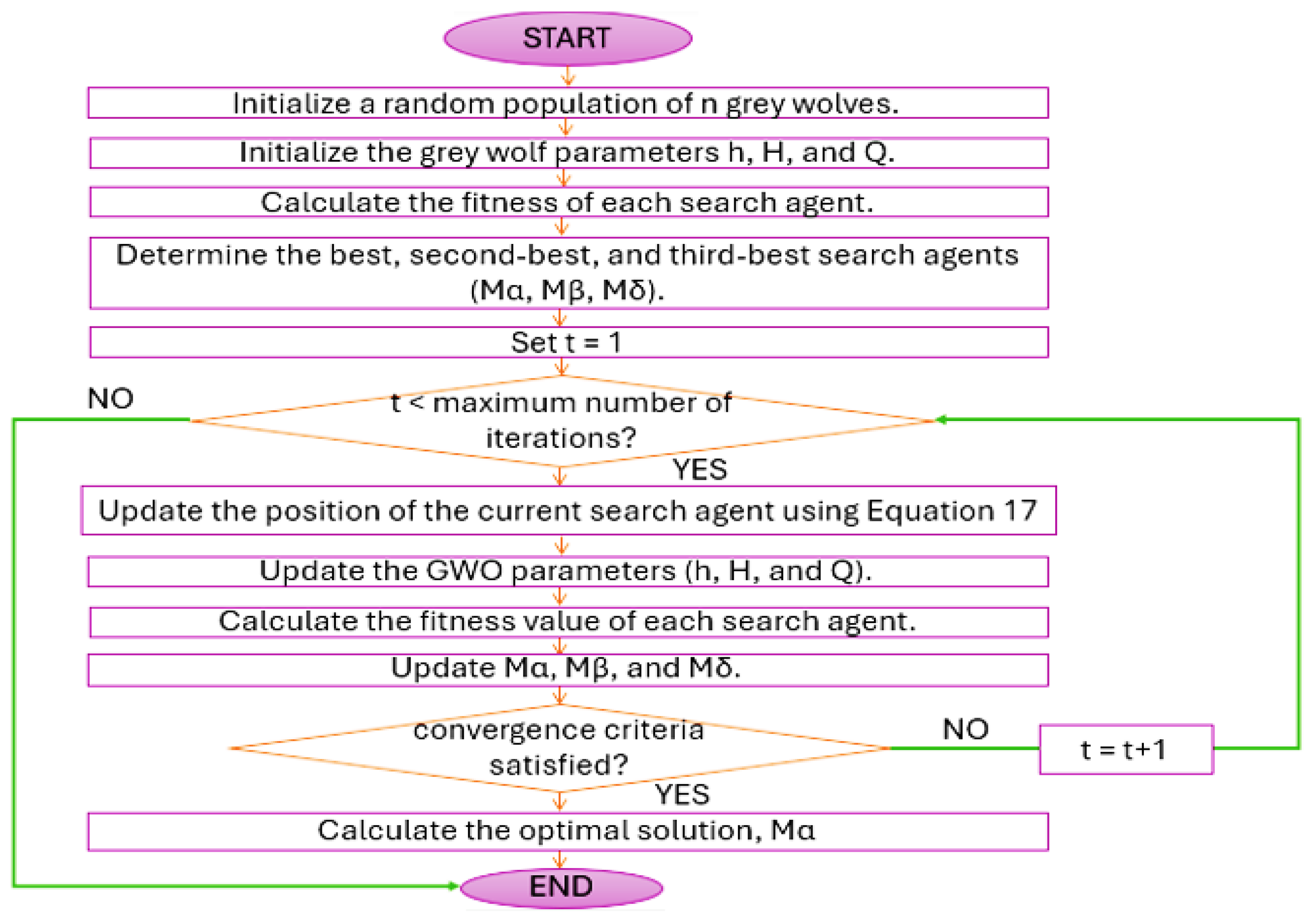

This study employs the GWO, a novel swarm-intelligence algorithm inspired by the grey wolves' social dominance hierarchy and hunting strategy to find optimal solutions for optimisation problems [

86]. In the GWO framework, the best-performing solution is designated alpha (α), signifying the top rank in the wolf’s social structure. The subsequent two best solutions are designated beta (β) and delta (δ), respectively, and the remaining solutions are labelled omega (ω). The α, β, and δ wolves lead the hunting process, with the ω wolves following their lead to find the global optimum. Greywolves begin encircling their prey during hunting by employing the equations shown below [

24].

Equation (7) shows how the position vector, of grey wolves is calculated.

Where,

= current iteration

= coefficient vector

= position vector

= position vector of the prey

The wolf’s position at the next step,

is then updated according to equation (8) as,

where,

= coefficient vector

This update adjusts the wolf's position to the prey's position and the calculated vector , influencing the encircling behaviour.

Equations (9) and (10) are employed to calculate the coefficient vectors

and

, respectively.

Components

and

contain random values between 0 and 1 and

decrease linearly from 2 to 0 during the iterative optimisation process. GWO algorithm generates a random set of solutions when optimisation starts. The algorithm then saves the top three solutions and updates the positions of the remaining search agents to their optimum solutions. When the termination criteria are met, the alpha solution’s location and value define the global optimum. Equations (11) to (13) calculate how far away the search agent is from the three leader wolves.

,

, and

represent the distance and direction of the current search agent (wolf) to the alpha (α), beta (β), and delta (δ) wolves, respectively.

is the current position of search agent and

is a coefficient vector.

and

are the positions of the alpha, beta, and delta wolves.

Equations (14) to (16) use the distance from each of the three top wolves to calculate a probable next position for the search. Thus, these equations update the position based on the leaders.

,

and

denote the next position of the search agent according to the influence of the alpha, beta, and delta wolves, respectively.

,

and

are coefficient vectors.

Equation (17) determines the final position of the search agent by finding the average of

,

and

at the next iteration,

to balance the influence of the alpha, beta, and delta wolves.

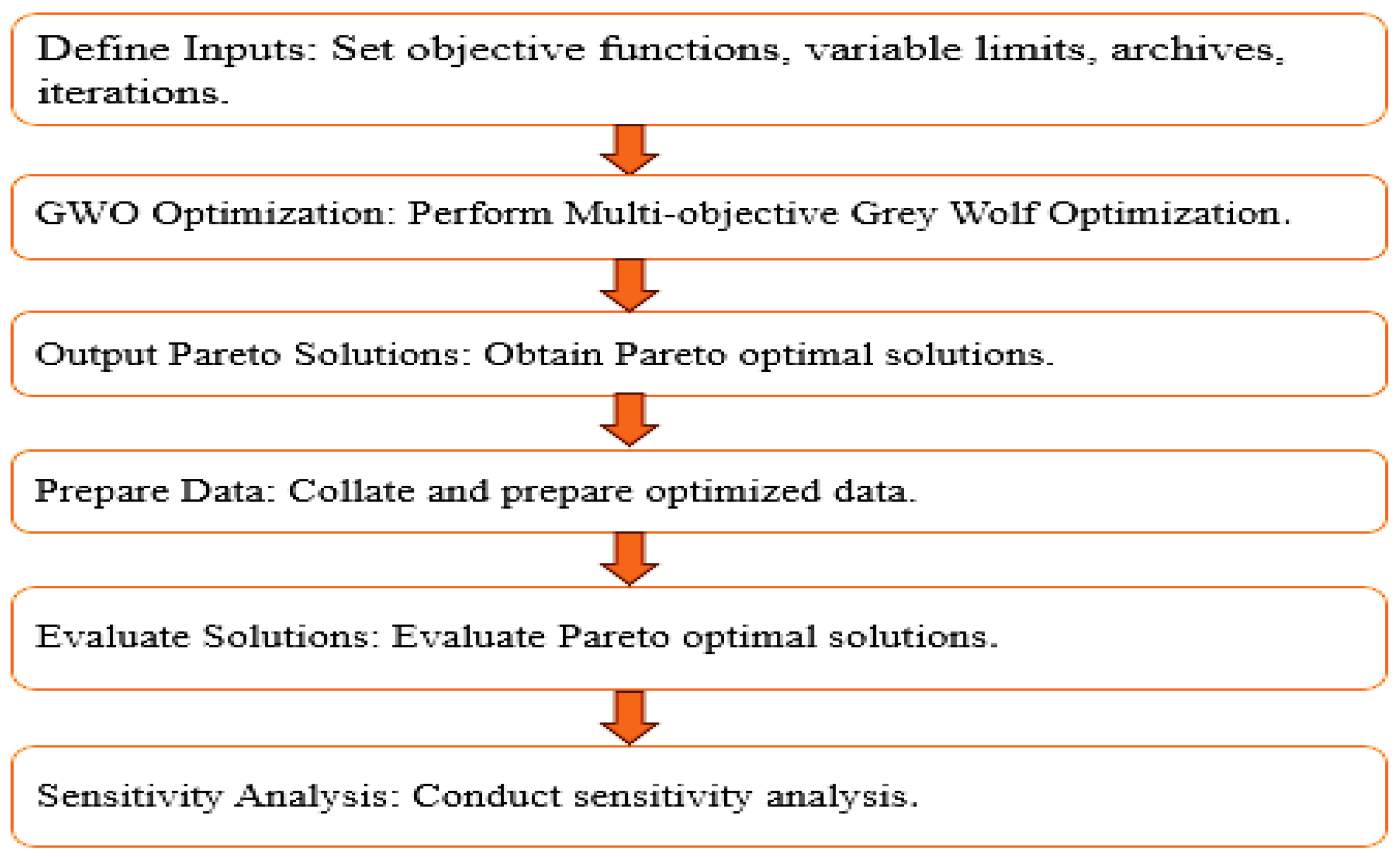

The optimisation methodology followed by this study and the general GWO optimisation flow chart for a single objective optimisation is illustrated in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4.

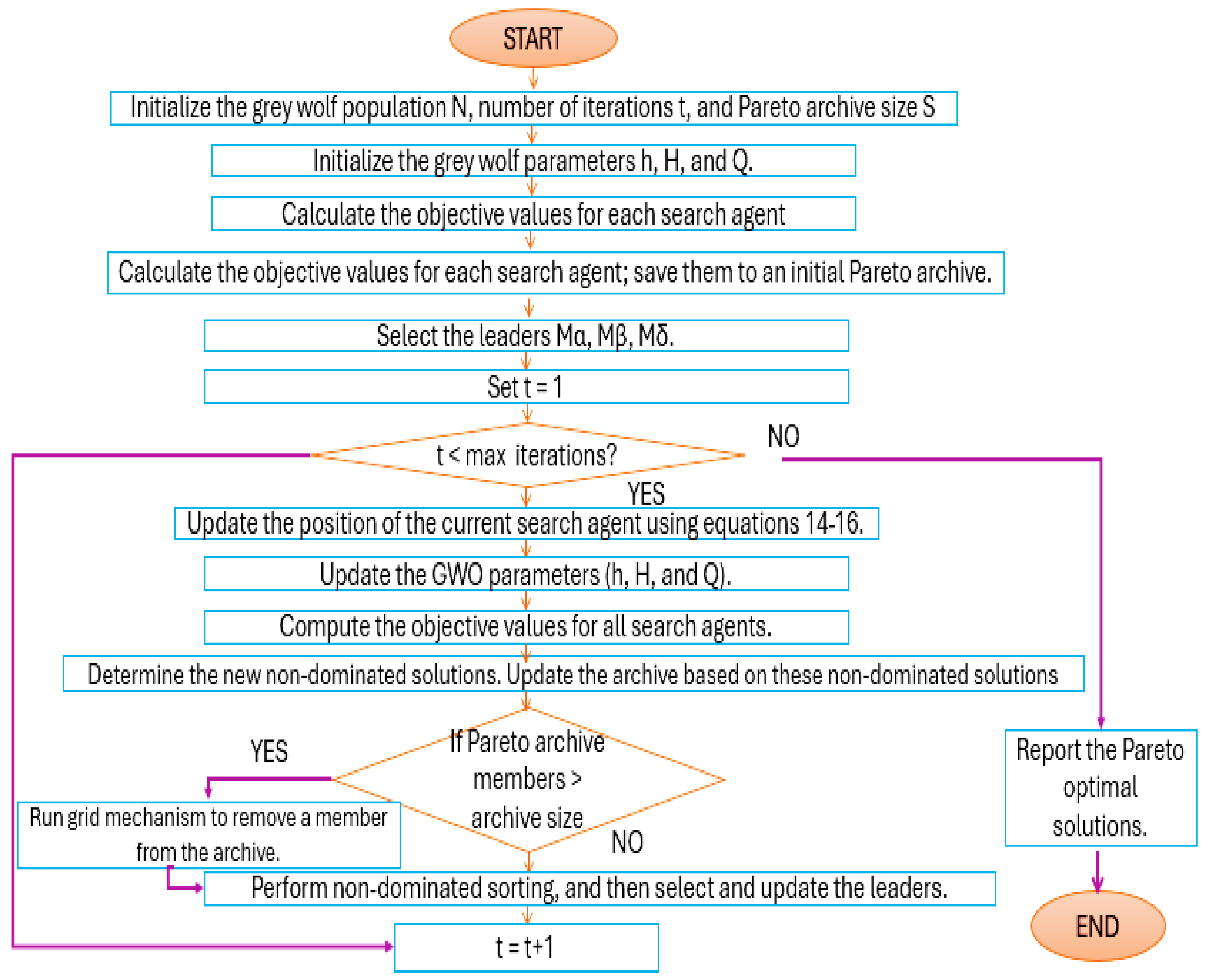

In energy systems, a problem could have multiple conflicting objective functions. In such instances, a multi-objective optimisation approach can be used to simultaneously generate a set of alternative feasible solutions. These solutions are referred to as Pareto Front Optimal or non-dominated solutions.

Figure 5 illustrates the flowchart for the multi-objective GWO technique. To adapt the standard GWO algorithm for multi-objective optimisation (MOGWO), two extra elements are included: the archive, to store the Pareto optimal solutions that are non-dominated. A leader selection mechanism, which chooses the alpha and beta wolves from the archive to head and direct the search.

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic diagram of a single-stage, dual-bed adsorption chiller during the adsorption–desorption cycle; (b) Flow configuration of the system during the inter-bed transitional (switching) phase.

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic diagram of a single-stage, dual-bed adsorption chiller during the adsorption–desorption cycle; (b) Flow configuration of the system during the inter-bed transitional (switching) phase.

Figure 3.

Optimization methodology.

Figure 3.

Optimization methodology.

Figure 4.

Single-objective GWO flowchart.

Figure 4.

Single-objective GWO flowchart.

Figure 5.

Multi-objective Greywolf optimisation flowchart.

Figure 5.

Multi-objective Greywolf optimisation flowchart.

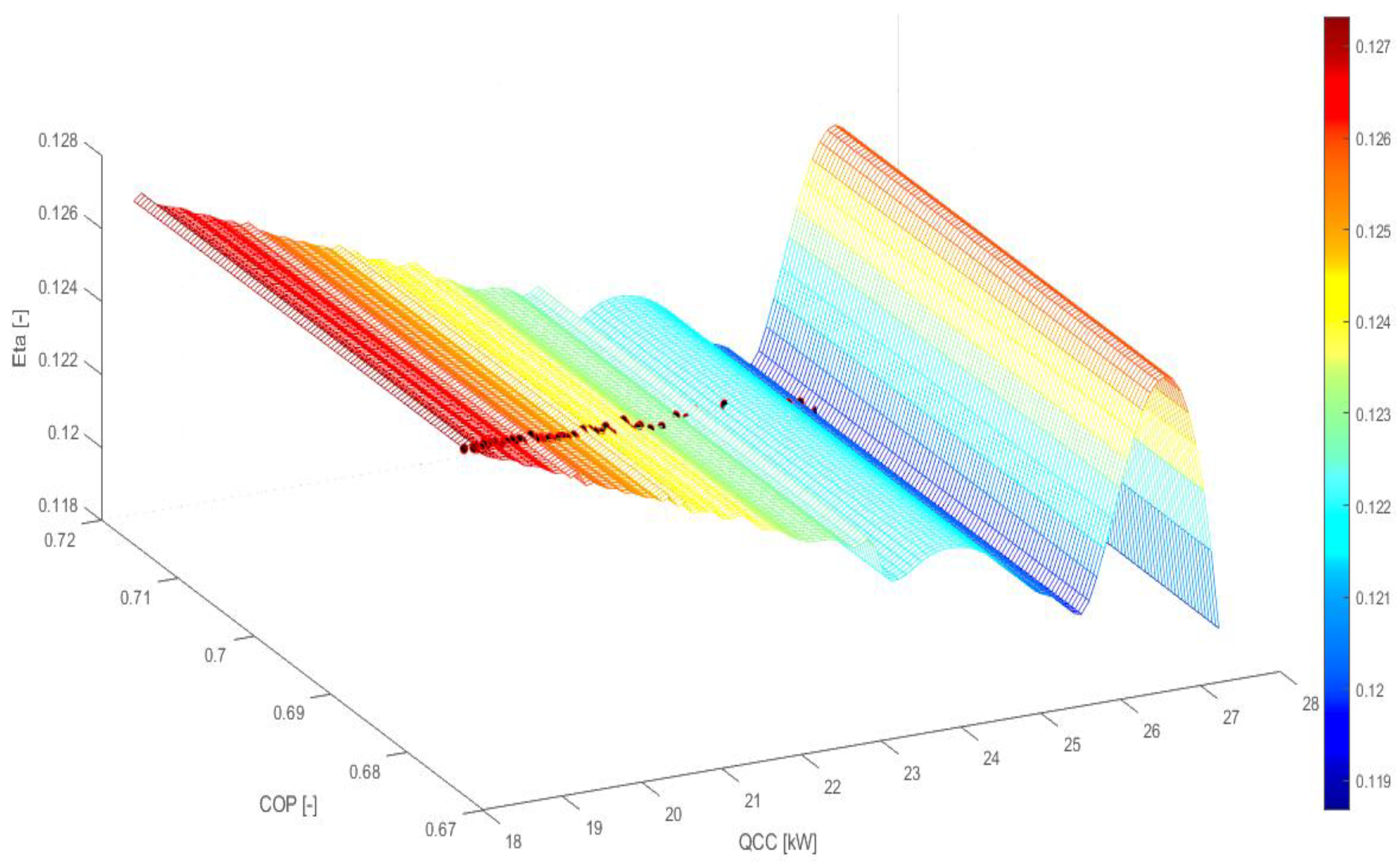

Figure 6.

Pareto front for Eta vs COP vs Qcc.

Figure 6.

Pareto front for Eta vs COP vs Qcc.

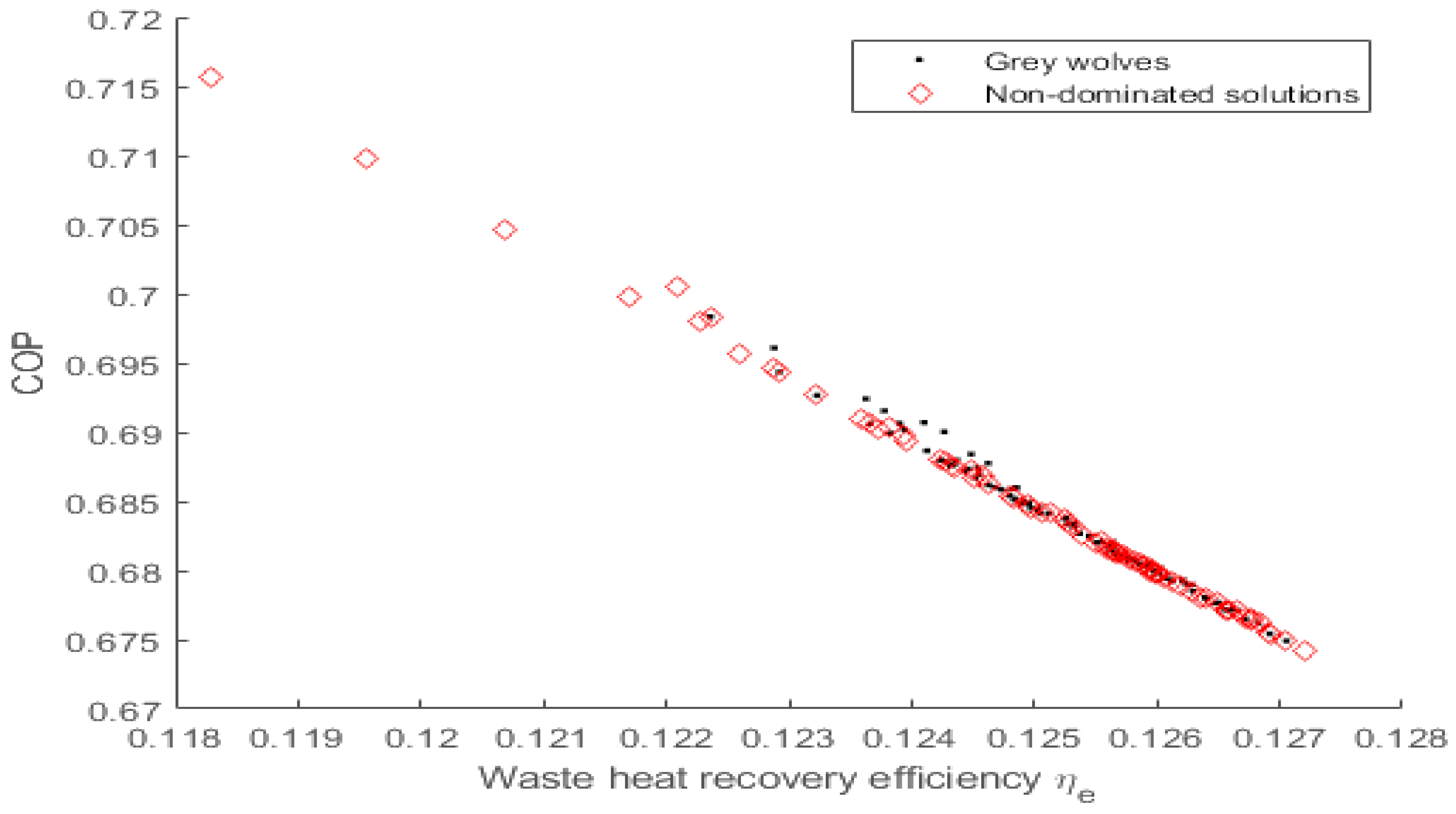

Figure 7.

Pareto front for COP vs Waste heat recovery efficiency, ηe.

Figure 7.

Pareto front for COP vs Waste heat recovery efficiency, ηe.

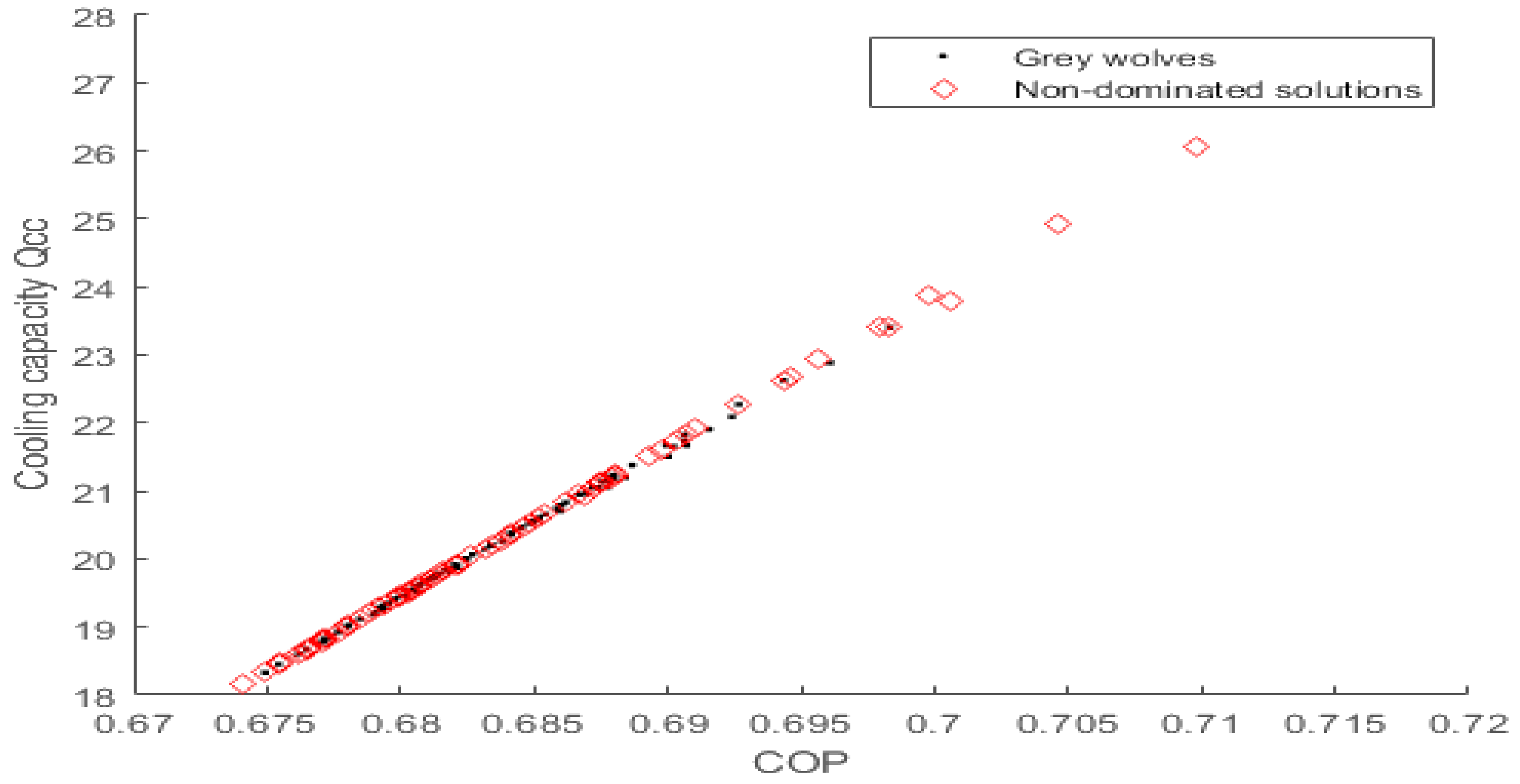

Figure 8.

Pareto front for Qcc vs COP.

Figure 8.

Pareto front for Qcc vs COP.

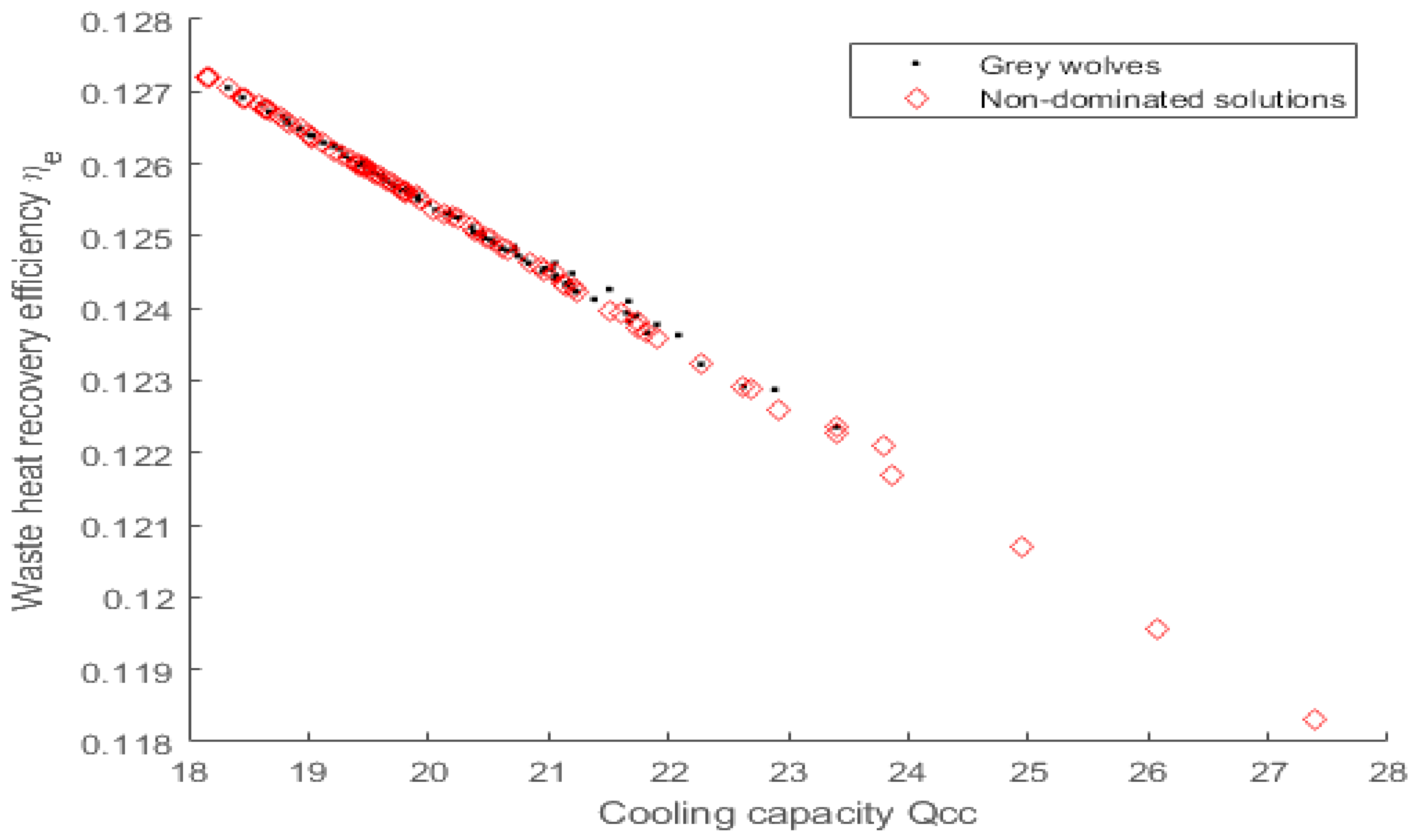

Figure 9.

Pareto front for ηe vs Qcc.

Figure 9.

Pareto front for ηe vs Qcc.

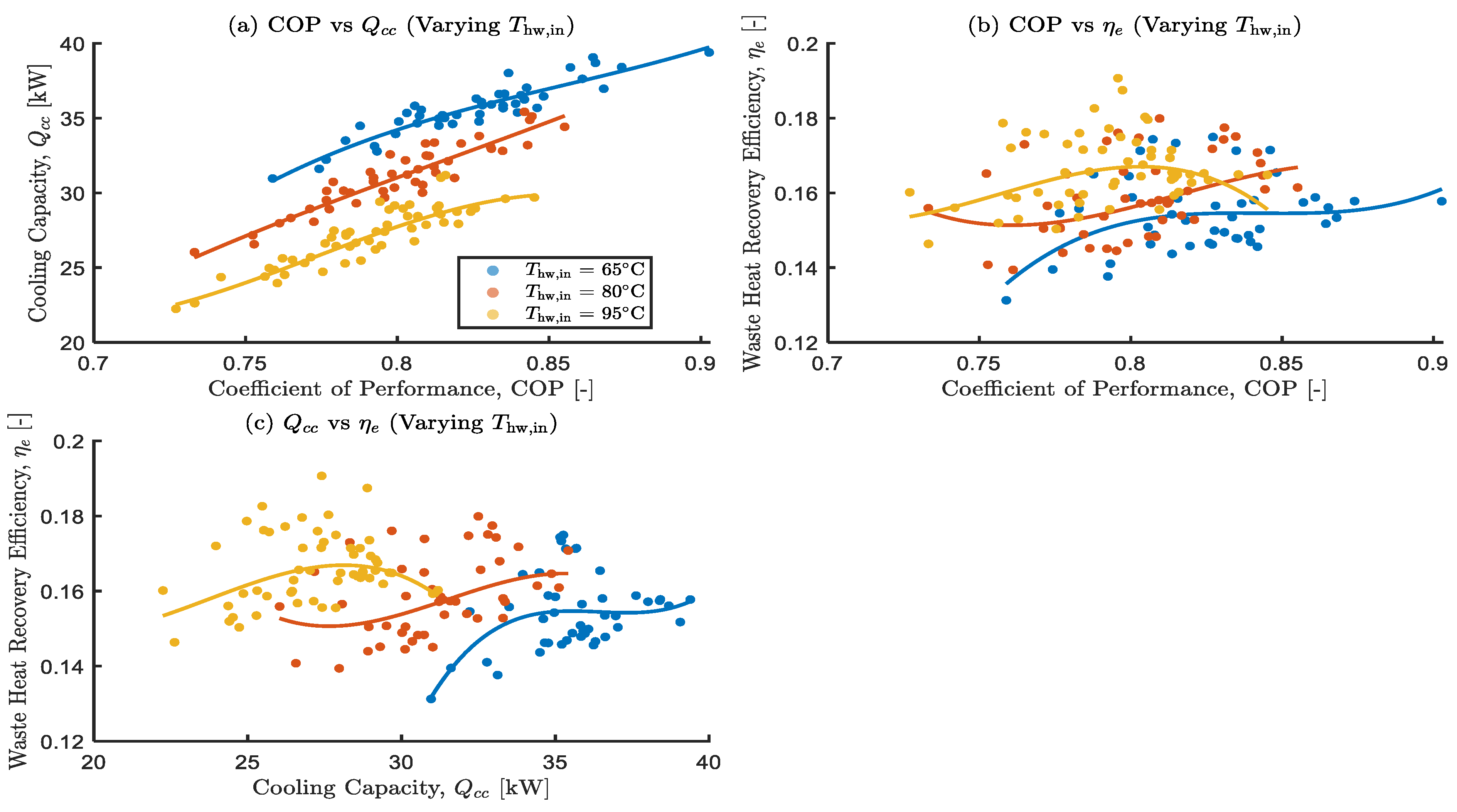

Figure 10.

Effects of varying hot water inlet temperature on the optimal objective functions.

Figure 10.

Effects of varying hot water inlet temperature on the optimal objective functions.

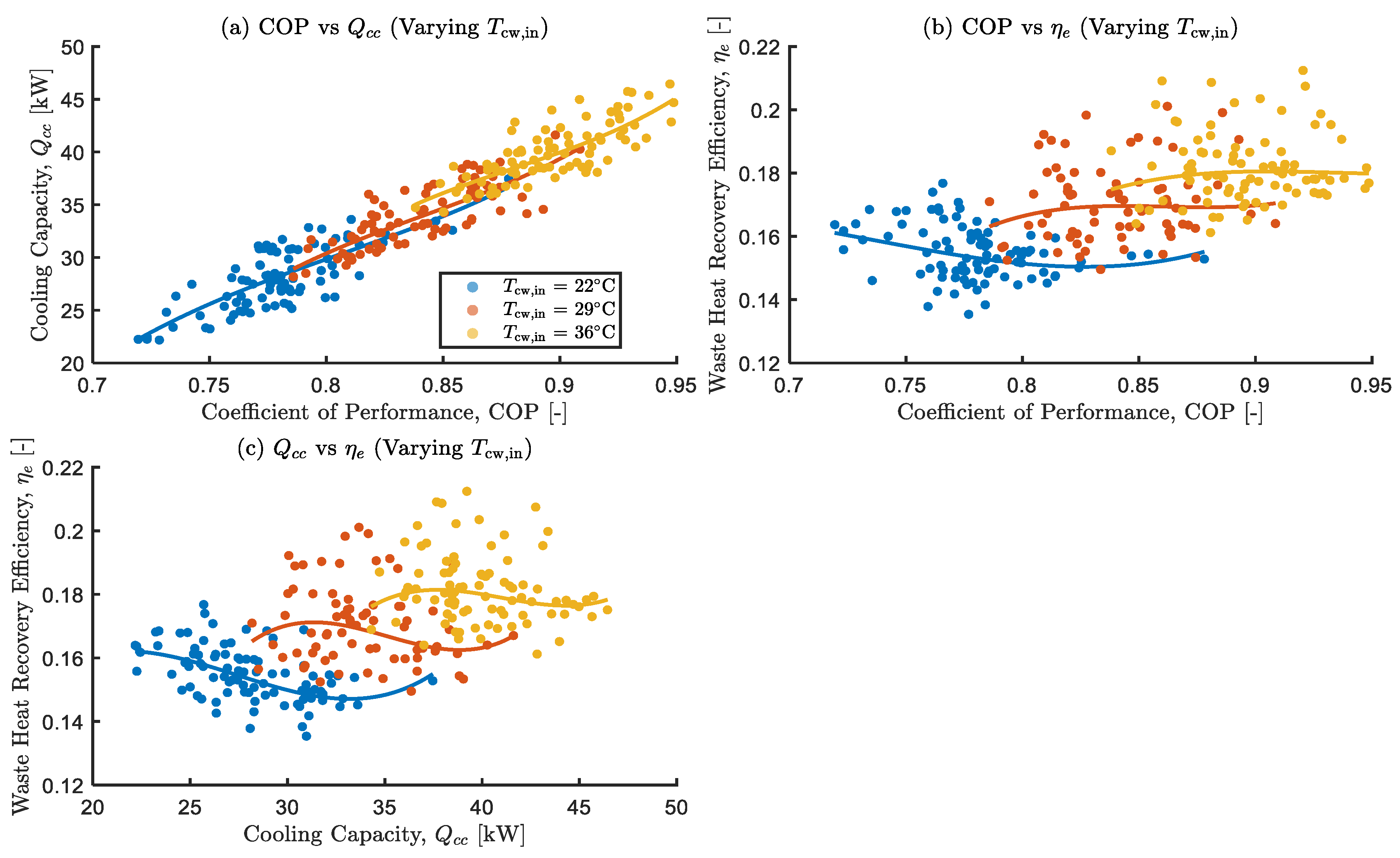

Figure 11.

Effects of varying cooling water inlet temperature on the optimal objective functions.

Figure 11.

Effects of varying cooling water inlet temperature on the optimal objective functions.

Figure 12.

Effects of varying chilled water inlet temperature on the optimal objective functions.

Figure 12.

Effects of varying chilled water inlet temperature on the optimal objective functions.

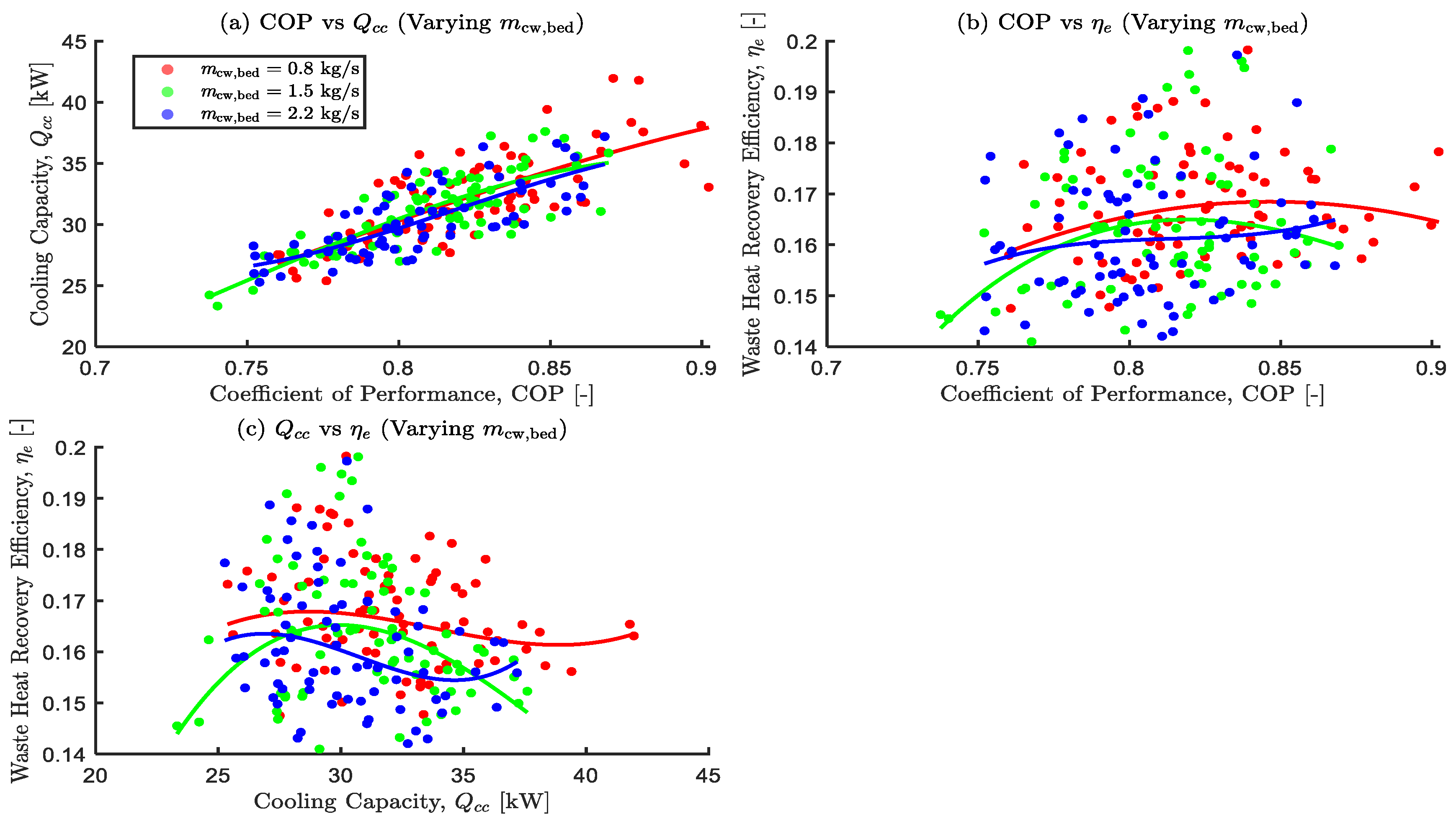

Figure 13.

Effects of varying mass flow rate of cooling water on the optimal objective functions.

Figure 13.

Effects of varying mass flow rate of cooling water on the optimal objective functions.

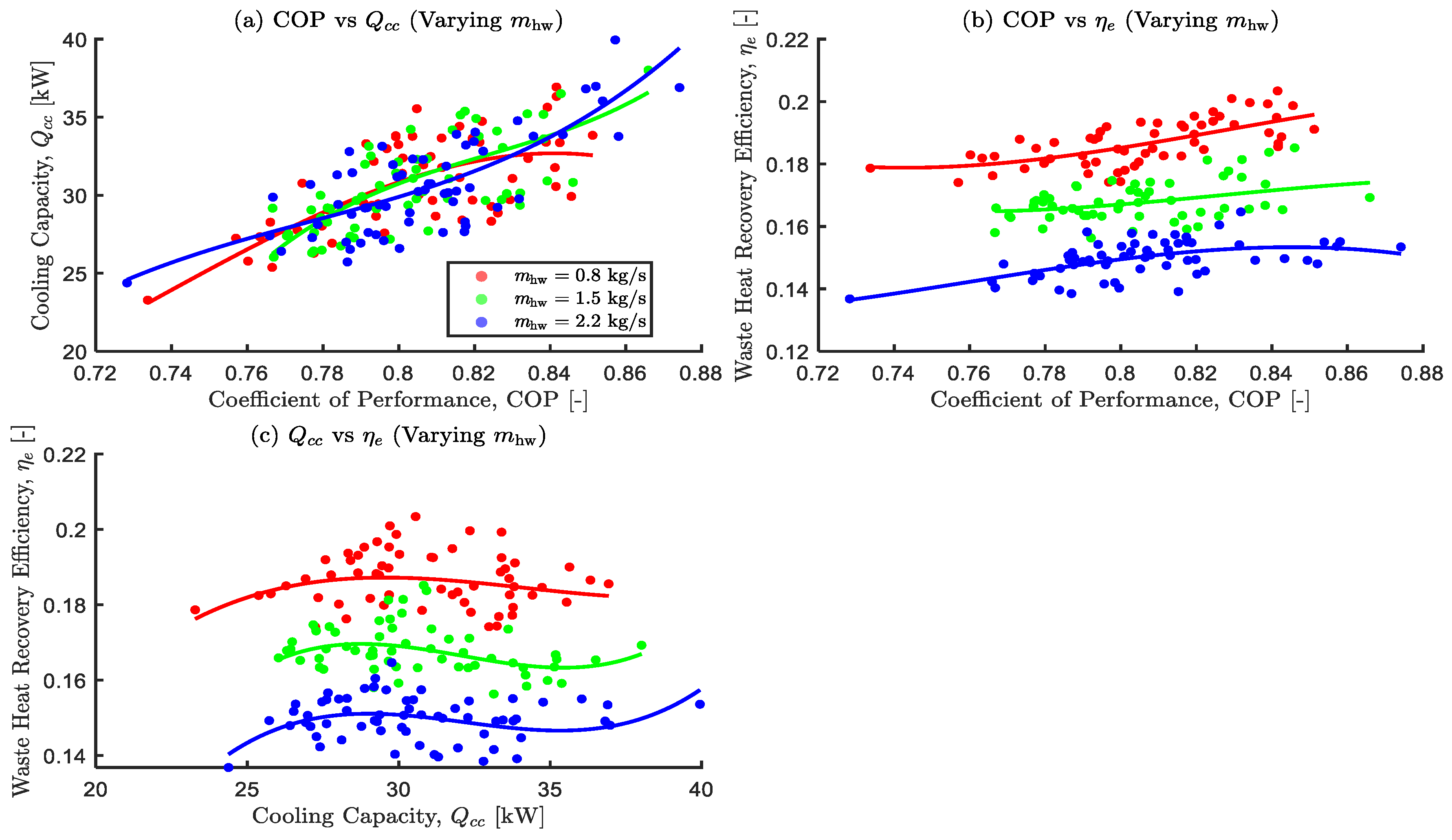

Figure 14.

Effects of varying mass flow rate of hot water on the optimal objective functions.

Figure 14.

Effects of varying mass flow rate of hot water on the optimal objective functions.

Figure 15.

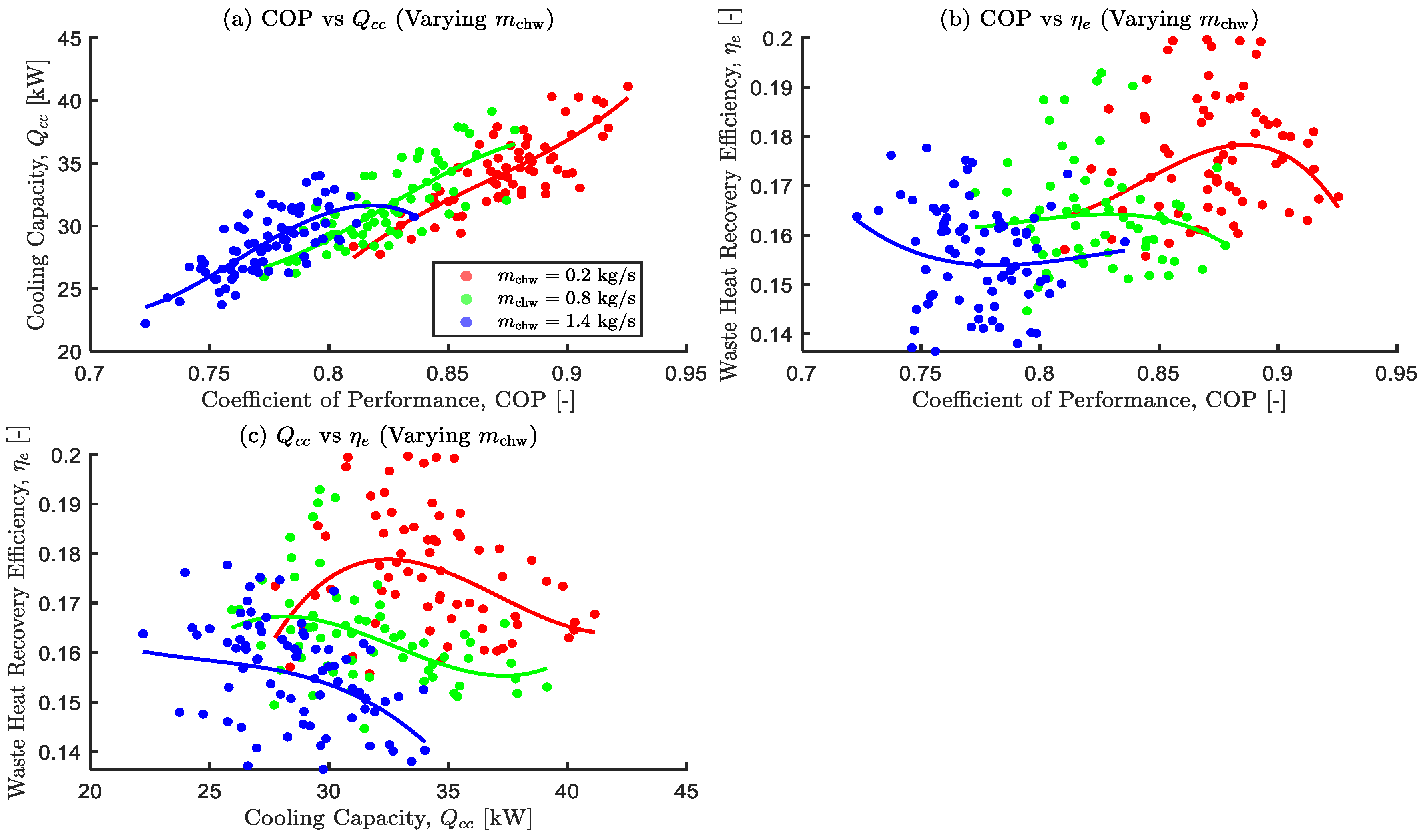

Effects of varying chilled water mass flow rate on the optimal objective functions.

Figure 15.

Effects of varying chilled water mass flow rate on the optimal objective functions.

Figure 16.

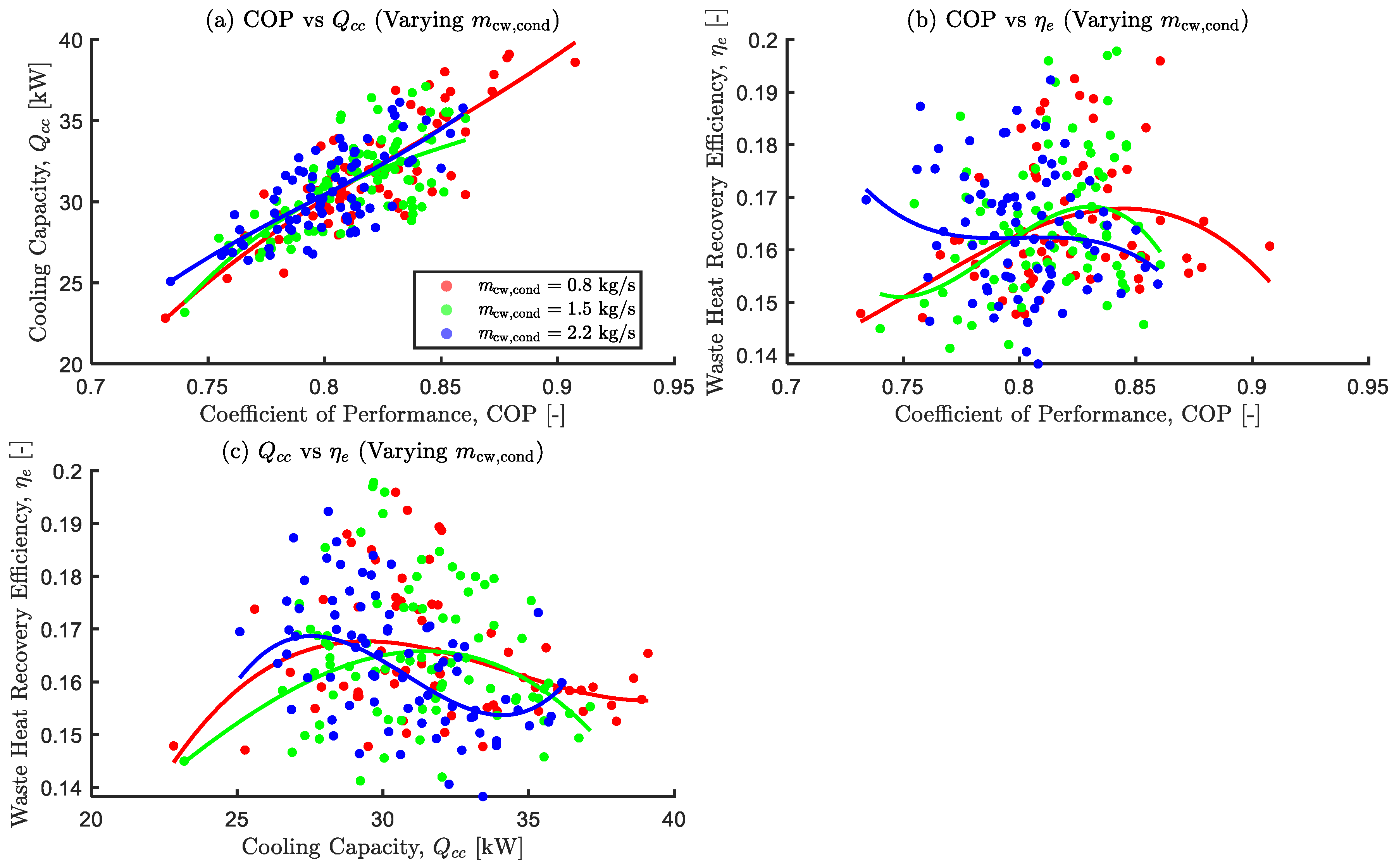

Effects of varying condenser cooling water mass flow rate on the optimal objective functions.

Figure 16.

Effects of varying condenser cooling water mass flow rate on the optimal objective functions.

Figure 17.

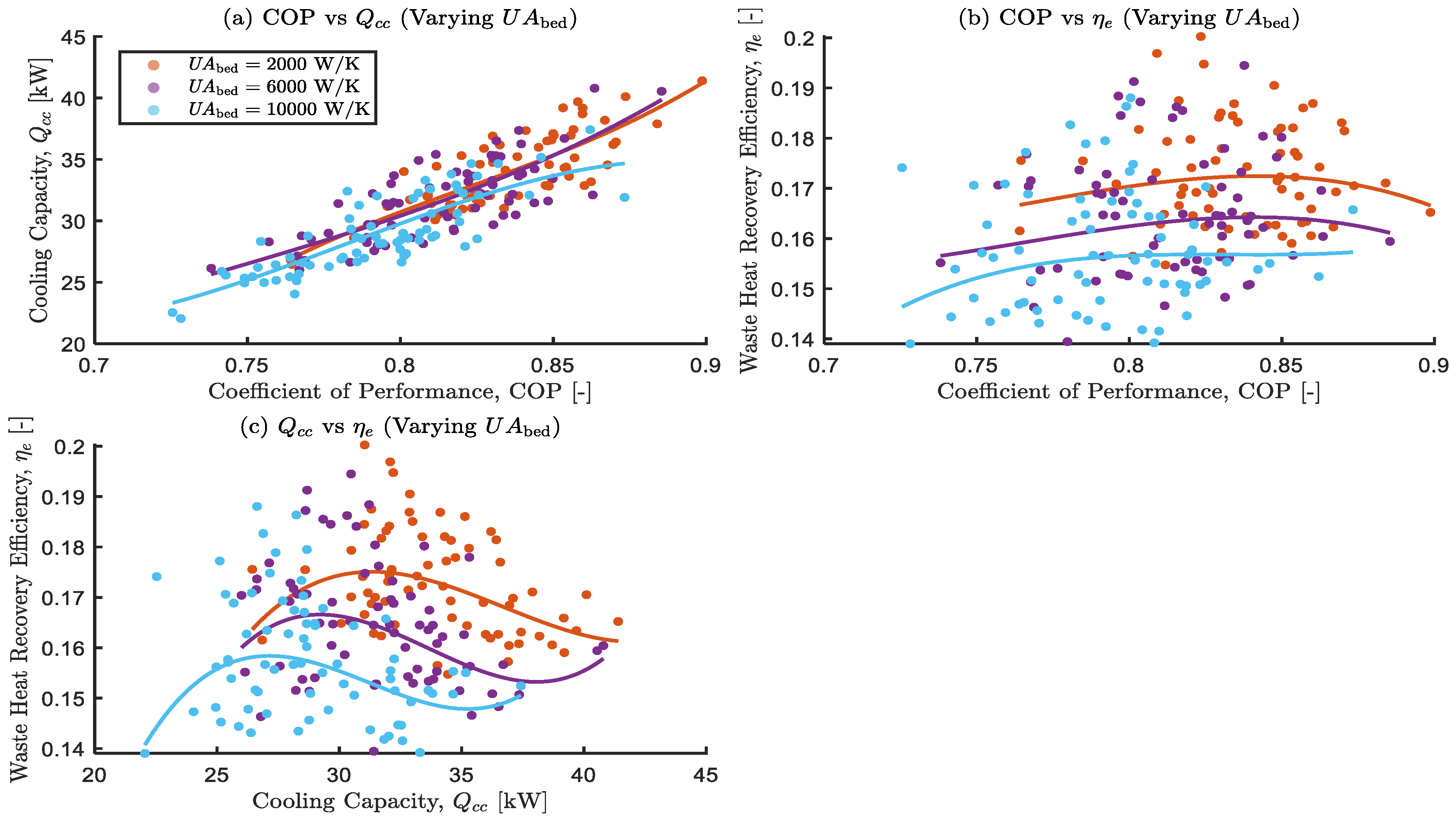

Effects of varying adsorbent bed overall thermal conductance on the optimal objective functions.

Figure 17.

Effects of varying adsorbent bed overall thermal conductance on the optimal objective functions.

Figure 18.

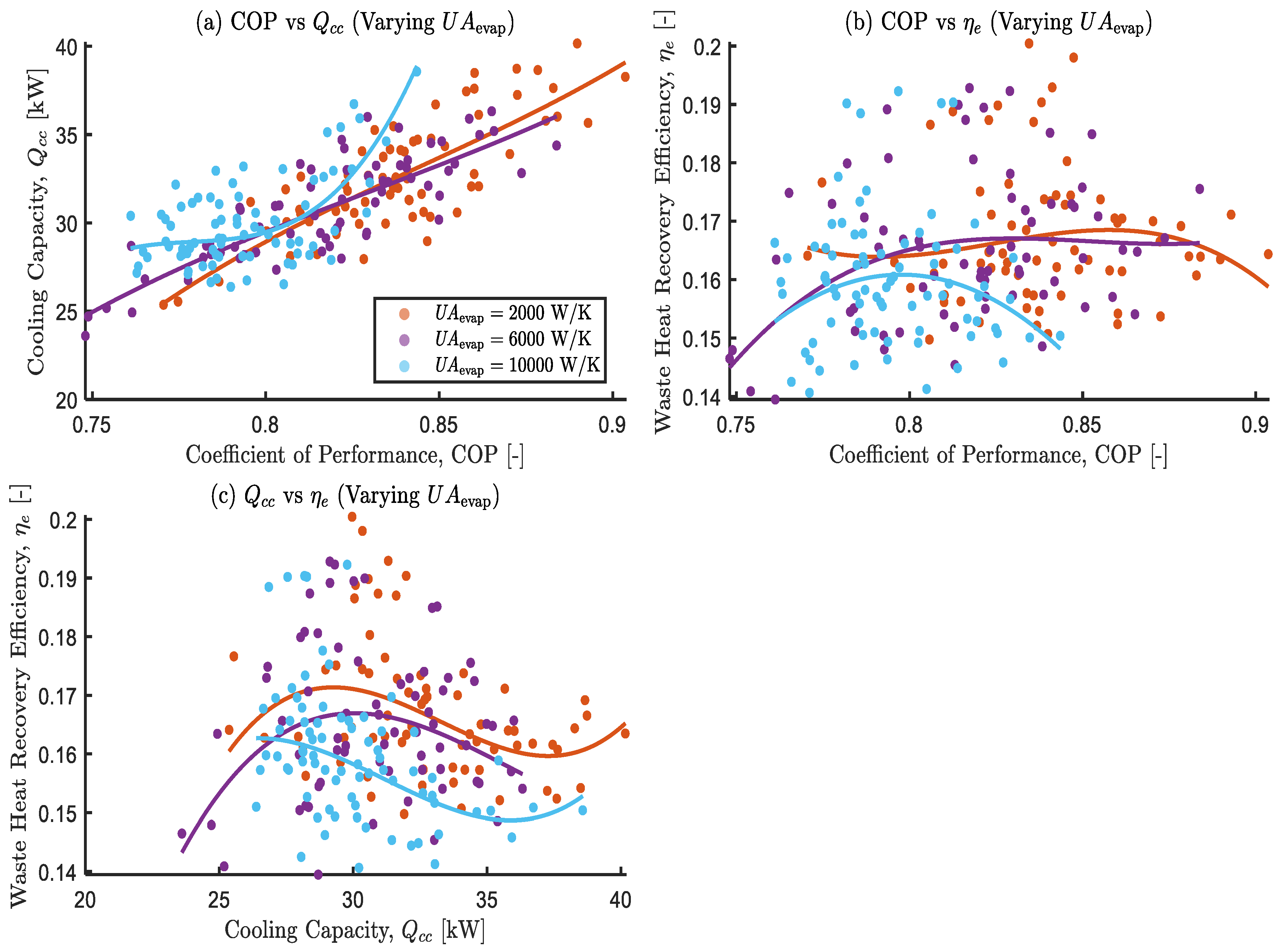

Effects of varying evaporator overall thermal conductance on the optimal objective functions.

Figure 18.

Effects of varying evaporator overall thermal conductance on the optimal objective functions.

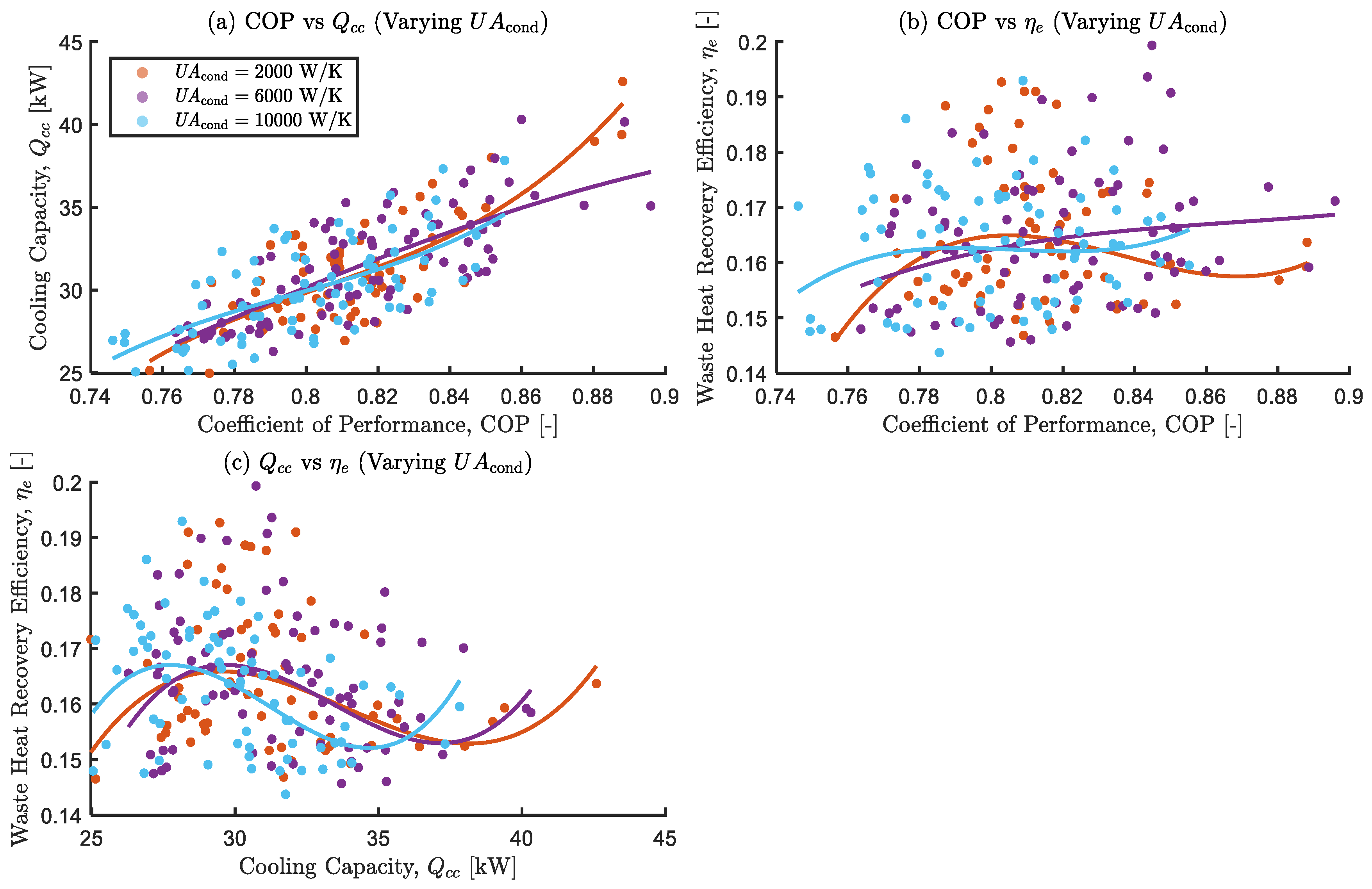

Figure 19.

Effects of varying condenser overall thermal conductance on the optimal objective functions.

Figure 19.

Effects of varying condenser overall thermal conductance on the optimal objective functions.

Table 1.

Major KPIs of adsorption chillers.

Table 1.

Major KPIs of adsorption chillers.

| Paper Titles |

KPIs |

Results Obtained |

| Study of a two-bed silica gel–water adsorption chiller: performance analysis. [42] |

Cooling capacity using the lumped parameter simulation model. |

The optimal value of 5.95 kW for a cycle time of 1600 s with the hot, cooling, and chilled water inlet temperatures at 85 °C, 25 °C, and 14 °C, respectively |

| Performance Prediction of a Two-bed Solar Adsorption Chiller with Adaptive Cycle Time Using a MIL-100(Fe)/Water Working Pair – Influence of Solar Collector Configuration. [43] |

Specific Cooling Power (SCP), Coefficient of Performance (COP) and Solar Coefficient of Performance (COPSc) using numerical simulation. |

A single-glazed insulated transparent solar collector with a predefined adsorption time of 110 s showed the highest thermal COP among other results. |

| Modeling of a re-heat two-stage adsorption chiller by AI approach. [44] |

Analyzed cooling Capacity (Cc) using ANFIS model for optimization. |

Other input parameters must be fixed and remain unaltered when analyzing the effect of a particular operating variable on the cooling capacity of a reheat two-stage adsorption chiller. |

| Examination of the effects of operating and geometric parameters on the performance of a two-bed adsorption chiller. [45] |

Analyzed the Cooling Capacity (CC), Coefficient of Performance (COP) and Specific Cooling Capacity (SCC) on the overall performance of a two-bed adsorption chiller using a detailed numerical model. |

Significant increase in COP and SCC by about 68% and 42%, respectively, with turbulent flow regimes. |

| Experimental Study of Performance Improvement of 3-Bed and 2-Evaporator Adsorption Chiller by Control Optimization. [46] |

Used control software on a modified prototype of a 3-Bed and 2-Evaporator Adsorption Chiller to investigate Coefficient of Performance (COP), Cooperation Adsorption Unit Heating Source and Operational Aspects Such as Noise and Vibrations. |

Substantial improvement in cooperation adsorption unit, heating source and chiller COP. |

| An adaptive neuro-fuzzy model of a re-heat two-stage adsorption chiller. [47] |

Experimentally tested for the effect of thermal conductance values of sorption elements and evaporator on the cooling capacity and other design parameters. |

The highest cooling capacity of 21.7 kW is achieved at the following design and operational parameters: Msorb = 40 kg, t = 1300 s, T = 80 C, Csorb/Cmet = 50, hAsorb = 4000 W/K, hAevap = 4000 W/K. |

| Performance enhancement of an adsorption chiller by optimum cycle time allocation at different operating conditions. [48] |

Experimental allocation of the optimum cycle time at different operating conditions. System to examine the Cooling Capacity and Enhancement Ratio of the System Cooling Capacity. |

Increment in system cooling capacity enhancement ratio of 15.6% at cooling, hot and chilled water inlet temperatures of 40 °C, 95 °C, and 10 °C, respectively. |

| Performance comparison of a two-bed solar-driven adsorption chiller with optimal fixed and adaptive cycle times using a silica gel/water working pair. [49] |

Comparative study of Optimal Fixed and Adaptive Cycle Times, Adsorption/Desorption (Ads/Des) Uptakes and preheating/precooling (Ph/Pc) Times. |

The adaptive cycle time resulted in 19% higher specific cooling power and a 66% higher COP than corresponding predicted values for a fixed cycle time condition, with a 0.7 °C minimum evaporator temperature reported for adsorption research works so far. |

Table 2.

Decision variables and bounds.

Table 2.

Decision variables and bounds.

| Variable Description |

Symbol |

Range |

Units |

| Hot water inlet temperature |

|

65 – 95 |

◦C |

| Cooling water inlet temperature |

|

22 – 36 |

◦C |

| Chilled water inlet temperature |

|

10 – 20 |

◦C |

| Hot water mass flow rate |

|

0.8 – 2.2 |

kgs− 1 |

| Bed cooling water mass flow rate |

|

0.8 – 2.2 |

kgs− 1 |

| Chilled water mass flow rate |

|

0.2 – 1.4 |

kgs− 1 |

| Condenser cooling water mass flow rate |

|

0.8 – 2.2 |

kgs− 1 |

| Adsorbent bed overall thermal conductance |

|

2,000 – 10,000 |

W/K |

| Evaporator overall thermal conductance |

|

2,000 – 10,000 |

W/K |

| Condenser overall thermal conductance |

|

10,000 – 24,000 |

W/K |

Table 3.

Optimal Decision Variables for COP Maximization (GWO).

Table 3.

Optimal Decision Variables for COP Maximization (GWO).

| Decision Variable |

Symbol |

Optimal Value |

Unit |

| Hot water inlet temperature |

|

95.00 |

°C |

| Cooling water inlet temperature |

|

22.00 |

°C |

| Chilled water inlet temperature |

|

20.00 |

°C |

| Hot water mass flow rate |

|

1.051 |

kg/s |

| Bed cooling water mass flow rate |

|

1.388 |

kg/s |

| Chilled water mass flow rate |

|

1.400 |

kg/s |

| Condenser cooling water mass flow rate |

|

1.364 |

kg/s |

| Adsorbent bed overall thermal conductance |

|

9830.45 |

W/K |

| Evaporator overall thermal conductance |

|

9931.11 |

W/K |

| Condenser overall thermal conductance |

|

14157.87 |

W/K |

| Maximized COP |

— |

0.69695 |

— |

Table 4.

Optimal Decision Variables for Qcc Maximization (GWO).

Table 4.

Optimal Decision Variables for Qcc Maximization (GWO).

| Decision Variable |

Symbol |

Optimal Value |

Unit |

| Hot water inlet temperature |

|

95.00 |

°C |

| Cooling water inlet temperature |

|

22.00 |

°C |

| Chilled water inlet temperature |

|

19.99 |

°C |

| Hot water mass flow rate |

|

1.198 |

kg/s |

| Bed cooling water mass flow rate |

|

1.750 |

kg/s |

| Chilled water mass flow rate |

|

1.390 |

kg/s |

| Condenser cooling water mass flow rate |

|

1.126 |

kg/s |

| Adsorbent bed overall thermal conductance |

|

9890.71 |

W/K |

| Evaporator overall thermal conductance |

|

7677.01 |

W/K |

| Condenser overall thermal conductance |

|

11495.20 |

W/K |

| Maximized Qcc |

— |

20.7589 |

kW |

Table 5.

Optimal Decision Variables for ηe Maximization.

Table 5.

Optimal Decision Variables for ηe Maximization.

| Decision Variable |

Symbol |

Optimal Value |

Unit |

| Hot water inlet temperature |

|

65.00 |

°C |

| Cooling water inlet temperature |

|

22.00 |

°C |

| Chilled water inlet temperature |

|

19.98 |

°C |

| Hot water mass flow rate |

|

2.198 |

kg/s |

| Bed cooling water mass flow rate |

|

1.658 |

kg/s |

| Chilled water mass flow rate |

|

1.396 |

kg/s |

| Condenser cooling water mass flow rate |

|

1.244 |

kg/s |

| Adsorbent bed overall thermal conductance |

|

9882.41 |

W/K |

| Evaporator overall thermal conductance |

|

6501.39 |

W/K |

| Condenser overall thermal conductance |

|

12386.87 |

W/K |

| Maximized ηe |

— |

0.12527 |

— |

Table 6.

Trend of Decision Variables under GWO-Based Single-Objective Optimization.

Table 6.

Trend of Decision Variables under GWO-Based Single-Objective Optimization.

| Decision Variable |

COP |

Qcc |

ηe |

Conflict |

|

↑ |

↑ |

↓ |

≠ |

|

↓ |

↓ |

↓ |

|

|

↑ |

↑ |

↑ |

|

|

↓ |

↑ |

↑ |

≠ |

|

↑ |

↑ |

↑ |

|

|

↑ |

↑ |

↑ |

|

|

↑ |

↓ |

↑ |

≠ |

|

↑ |

↑ |

↑ |

|

|

↑ |

↓ |

↓ |

≠ |

|

↑ |

↑ |

↑ |

|

Table 7.

Set values of the hyperparameters.

Table 7.

Set values of the hyperparameters.

| Hyperparameter |

Value |

| Grid inflation parameter, alpha |

0.1 |

| Leader selection pressure parameter, beta |

4 |

| Gamma |

2 |

| Archive size |

100 |

| Number of agents |

100 |

| Maximum iterations |

50 |

| Number of Grids per Dimension, nGrid |

100 |

| Final a |

0 |

| Random seed |

42 |

| Leader selection |

Roulette Wheel based on hypercube crowding |

| Crowding distance |

Crowding handled through hypercube grid and the “DeleteFromRep” function |

Table 8.

Performance metrics comparison for a two-bed, single-stage silica-gel/water adsorption chiller.

Table 8.

Performance metrics comparison for a two-bed, single-stage silica-gel/water adsorption chiller.

| Parameter |

Chua, Ng & Saha [31,89] |

MOGWO – This Work |

| COP Range |

0.50 – 0.65 (at

= 90 °C,

= 25 °C) |

0.5123 – 0.6859 (at

= 86.77 °C,

₎ = 22.01 °C) |

| Cooling Capacity (Qcc) |

6 – 10 kW (depending on cycle time and

) |

12.45 – 20.73 kW |

| Waste-Heat Recovery Efficiency (ηₑ) |

≈ 0.10 – 0.12 (i.e., 10 – 12 % of heat input converted to cooling at 90 °C/25 °C) |

0.0824 – 0.1248 (i.e., 8.24 – 12.48 % of heat input recovered) |

| Operating Conditions |

= 70 – 95 °C (optimal near 90 °C),

= 20 – 30 °C (focus 25 °C), Two beds, ~ 1 kg/bed; finned-tube UA (~ 10³ W/K) |

= 86.77 °C

= 22.01 °C, Two beds; UAevap = 6000 W/K, UAcond = 17 000 W/K |