1. Introduction

Contemporary organizations face unprecedented

complexity, volatility, and uncertainty in their operating environments (Uhl-Bien

& Arena, 2018; Reeves et al., 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic, climate change,

geopolitical instability, and technological disruption have all underscored the

limitations of traditional management approaches that assume relative stability

and predictability. In this context, organizational resilience—the capacity to

absorb disturbances while maintaining essential functions and identity while

adapting to changing circumstances (Williams et al., 2017)—has emerged as a

critical capability.

Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS) theory offers a

promising framework for understanding and enhancing organizational resilience.

While CAS principles have gained traction in organizational theory (Dooley,

2017; Allen et al., 2019), empirical research validating their effectiveness in

organizational contexts remains limited, particularly regarding quantifiable

outcomes and implementation methodologies. The field currently lacks robust

evidence connecting specific CAS principles to resilience outcomes and practical

guidance on how organizations can effectively implement these principles within

their unique contexts.

This study addresses these gaps through a

mixed-methods investigation examining how CAS principles manifest in

organizations and their relationship to measurable resilience outcomes.

Specifically, the research investigates four key principles derived from CAS

theory:

Organizations as natural living systems

Organizations as self-maintaining systems

Resilient systems having deep foundations

Systems maintaining stability through feedback loops

The research questions are:

RQ1: To what extent do organizations

demonstrating higher implementation of CAS principles show greater resilience

during disruptive events?

RQ2: Which specific CAS principles most

strongly correlate with organizational resilience metrics?

RQ3: What implementation approaches most

effectively translate CAS principles into organizational practice, and how are

these approaches influenced by contextual factors?

This paper makes three primary contributions.

First, it provides empirical validation of CAS principles in organizational

contexts through quantitative analysis, extending theoretical understanding of

how complex systems theory applies to organizational resilience. Second, it

identifies specific mechanisms through which CAS principles enhance

organizational resilience, clarifying the causal pathways between

implementation and outcomes. Third, it offers a practical, context-sensitive

framework for implementing CAS principles, addressing the theory-practice gap

that has limited the practical application of complexity science in

organizations.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Systems Thinking and Complex Adaptive Systems

Systems thinking represents a paradigm shift from

reductionist approaches that analyze components in isolation to holistic

approaches emphasizing relationships, patterns, and context (Meadows, 2008;

Senge, 2006). A system is defined as “a set of elements or parts that is

coherently organized and interconnected in a pattern or structure that produces

a characteristic set of behaviors” (Meadows, 2008, p. 188).

Building on general systems theory, Complex

Adaptive Systems (CAS) theory focuses specifically on systems characterized by

nonlinearity, emergence, self-organization, and adaptation (Holland, 2014;

Gell-Mann, 2020). For this study, complex adaptive systems are defined as

networks of interdependent agents that interact dynamically, self-organize, and

generate emergent properties not reducible to the system’s components

(Mitchell, 2009).

The distinction between complicated and complex

systems is crucial for organizational theory. Complicated systems (e.g., an

aircraft) have many interacting parts but operate in predictable ways, while

complex systems (e.g., an ecosystem) feature numerous agents interacting in

ways that produce unpredictable emergent behaviors (Snowden & Boone, 2007).

This distinction has significant implications for management

approaches—complicated systems can be optimized through careful analysis and

planning, while complex systems require adaptive, experimental approaches.

2.2. Theoretical Perspectives on Organizational Resilience

Organizational resilience has been conceptualized

through multiple theoretical lenses, each offering distinct insights and

prescriptions. Understanding how CAS theory complements and extends these

perspectives is essential for positioning the research contribution.

Resource-Based View (RBV): From an RBV

perspective, resilience stems from possessing valuable, rare, inimitable, and

non-substitutable resources that enable adaptation (Barney, 1991; Duchek,

2020). While RBV provides insights into the importance of resource

configurations, it often treats these configurations as relatively static and

underemphasizes the dynamic processes through which resources are reconfigured

during disruptions.

Dynamic Capabilities: This perspective views

resilience as deriving from an organization’s ability to integrate, build, and

reconfigure competencies in response to changing environments (Teece, 2018;

Fainshmidt et al., 2023). Dynamic capabilities theory aligns more closely with

CAS principles but often focuses on deliberate managerial actions rather than

emergent, self-organizing processes.

High Reliability Organization (HRO) Theory:

HRO theory examines how organizations maintain reliable performance in

high-risk environments through mindfulness, redundancy, and expertise (Weick

& Sutcliffe, 2015). While offering valuable insights into reliability, HRO

theory typically emphasizes error prevention rather than adaptive response to

unpredictable disruptions.

Institutional Theory: This perspective

examines how institutional pressures shape organizational responses to

disruption, highlighting the role of legitimacy and isomorphism in resilience

strategies (Linnenluecke, 2017). Institutional theory provides context for

understanding external constraints but may underemphasize internal adaptive

processes.

CAS Theory’s Distinctive Contribution: CAS

theory complements these perspectives by emphasizing:

Emergent properties arising from agent interactions rather than top-down design

Self-organization as a natural adaptive process rather than solely managed change

Nonlinear causality and the potential for small interventions to create large effects

The importance of distributed intelligence rather than centralized control

Adaptation as an ongoing process rather than a planned response to specific disruptions

By integrating CAS theory with these established

frameworks, we gain a more comprehensive understanding of organizational

resilience that acknowledges both deliberate design and emergent adaptation,

internal capabilities and external contexts, and stability and change dynamics.

2.3. Conceptual Model: CAS Principles and Organizational Resilience

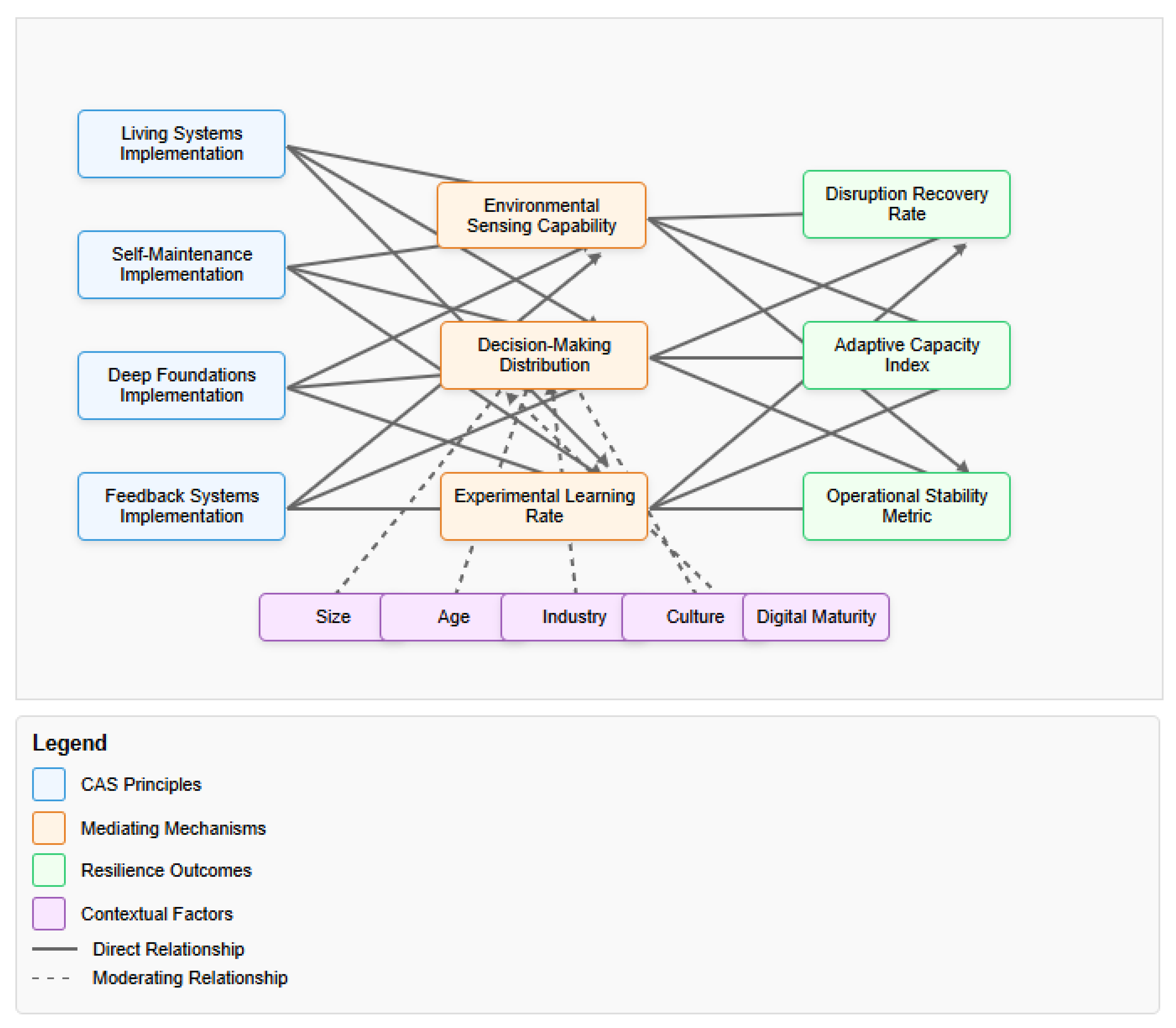

Based on the review of complexity science and

organizational theory, we propose a conceptual model linking CAS principles to

organizational resilience (Figure 1).

This model hypothesizes relationships between the implementation of CAS

principles and organizational resilience outcomes, mediated by specific

organizational capabilities and moderated by contextual factors.

Figure 1

depicts the four CAS principles (left side) influencing three organizational

resilience metrics (right side). The model illustrates three key mediating

mechanisms—environmental sensing capability, decision-making distribution, and

experimental learning rate—that translate CAS principles into resilience

outcomes. Additionally, the model shows how contextual factors (organizational

size, age, industry, culture, and digital maturity) moderate both the

implementation approach selected and the effectiveness of that implementation.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of CAS Principles and Organizational Resilience.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model of CAS Principles and Organizational Resilience.

The model posits that:

Higher implementation of CAS principles will positively correlate with organizational resilience metrics

Different CAS principles will influence different aspects of resilience to varying degrees

The relationship between CAS implementation and resilience will be mediated by specific organizational capabilities

Contextual factors will moderate the relationship between implementation approaches and CAS principles

This conceptual model guided the empirical

investigation and helps position the findings within the broader theoretical

landscape.

2.4. The Four CAS Principles

Building on prior research, this study investigates

four key CAS principles and their organizational applications:

2.4.1. Organizations as Natural Living Systems

This principle conceptualizes organizations not as

machines with interchangeable parts but as living entities with complex,

interdependent relationships (Wheatley, 2006; Allen et al., 2019). Living

systems operate through distributed intelligence rather than centralized

control, with each component responding to local conditions while contributing

to the system’s overall functioning (Laloux, 2014; Lee & Edmondson, 2017).

This perspective challenges traditional

command-and-control approaches to management, suggesting instead that

organizations thrive when they embrace distributed decision-making, permeable

boundaries, and emergent strategy. Recent research in digital transformation

highlights how this principle becomes increasingly important in

knowledge-intensive and rapidly changing environments (Sambamurthy et al.,

2021).

2.4.2. Organizations as Self-Maintaining Systems

Drawing on autopoiesis theory (Maturana &

Varela, 1980; Magalhães & Sanchez, 2009), this principle emphasizes

organizations’ capacity to continuously regenerate their components while

preserving their overall identity and purpose. This requires balancing

stability (in core values and purpose) with flexibility (in strategies and

structures)—what organizational theorists call “ambidexterity” (O’Reilly &

Tushman, 2013).

Self-maintenance connects to organizational

identity theory (Albert & Whetten, 1985) and recent work on identity

plasticity (Kreiner et al., 2022), which examines how organizations maintain

coherence while adapting to changing environments. This principle suggests that

resilience depends not just on adaptation but on maintaining core identity

elements that provide continuity amid change.

2.4.3. Resilient Systems Having Deep Foundations

This principle focuses on the structural

characteristics that enable system resilience. These include diversity (variety

in perspectives and capabilities), redundancy (multiple ways to accomplish

critical functions), social capital (strong relationships and trust), and

distributed resources (avoiding single points of failure) (Walker & Salt,

2012; Folke et al., 2016).

This principle intersects with social capital

theory (Adler & Kwon, 2002) and research on organizational slack

(Rahrovani, 2020), highlighting how seemingly “inefficient” investments in

relationships and redundancy contribute to adaptive capacity during

disruptions. Recent pandemic research has reinforced the importance of these

foundations, showing how organizations with pre-existing diversity and

redundancy adapted more effectively to COVID-19 disruptions (Heylighen et al.,

2022).

2.4.4. Systems Maintaining Stability Through Feedback Loops

This principle examines how feedback mechanisms

enable system adaptation and stability. Both balancing feedback (maintaining

stability) and reinforcing feedback (amplifying change) are necessary for

healthy system functioning (Meadows, 2008; Senge, 2006). In organizational

contexts, these feedback mechanisms operate at multiple time scales and across

system boundaries.

This principle connects to organizational learning

theory (Argote & Miron-Spektor, 2011) and recent work on strategic sensing

capabilities (Schoemaker et al., 2018). It suggests that resilience depends not

just on responding to feedback but on designing multiple feedback channels that

provide information at different timescales and from diverse perspectives.

2.5. Potential Tensions and Paradoxes in CAS Implementation

While CAS principles offer significant potential

benefits, they also present tensions and paradoxes that organizations must

navigate. These include:

Efficiency vs. Resilience: Building redundancy and diversity enhances resilience but may reduce short-term efficiency (Rahrovani, 2020). Organizations must balance optimization with maintaining adaptive capacity.

Autonomy vs. Alignment: Distributed decision-making enhances local responsiveness but can create coordination challenges and strategic inconsistency (Lee & Edmondson, 2017). Organizations must develop mechanisms to balance local autonomy with systemic coherence.

Exploration vs. Exploitation: Adapting to changing environments requires exploration of new possibilities, but organizations must also exploit existing capabilities (O’Reilly & Tushman, 2013). This creates tension in resource allocation and organizational focus.

Emergence vs. Intention: CAS principles emphasize emergent, bottom-up processes, but organizations also require intentional design and direction (Uhl-Bien & Arena, 2018). Finding the appropriate balance between allowing emergence and providing direction presents ongoing challenges.

These tensions highlight that CAS implementation is

not a simple prescription but requires nuanced approaches adapted to specific

organizational contexts. This research examines how organizations successfully

navigate these tensions in practice.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

The study employed a sequential explanatory

mixed-methods design (Creswell & Creswell, 2017) consisting of:

A quantitative study examining the relationship between CAS implementation and organizational resilience metrics across 42 organizations (Phase 1)

Qualitative case studies of 12 organizations selected from the quantitative sample to investigate implementation approaches in depth (Phase 2)

Integration of findings to develop a comprehensive framework for CAS implementation (Phase 3)

This design was selected to provide both

statistical validation of CAS principles (addressing RQ1 and RQ2) and rich

contextual understanding of implementation processes (addressing RQ3). The

sequential nature allowed Phase 1 findings to inform case selection and focus

areas for Phase 2, while the integration phase enabled development of a

comprehensive implementation framework grounded in both quantitative and

qualitative evidence.

3.2. Quantitative Study (Phase 1)

3.2.1. Sample

The quantitative sample comprised 42 organizations

across four industries: healthcare (n=11), technology (n=14), manufacturing

(n=9), and financial services (n=8). Organizations varied in size (small:

<500 employees, n=14; medium: 500-5,000 employees, n=17; large: >5,000

employees, n=11) and age (young: <10 years, n=13; established: 10-50 years,

n=19; mature: >50 years, n=10). While this sample size was sufficient for

primary analyses based on power calculations, we acknowledge the limitations of

a relatively small sample, particularly for more complex statistical procedures

such as mediation analyses (see Limitations section).

Organizations were recruited through industry

associations and researcher networks. Participation required commitment to

provide data access, facilitate interviews, and share performance metrics. The

sample was not randomly selected but designed to represent diverse

organizational contexts. This sample size provided sufficient statistical power

(0.82) to detect medium effect sizes (f2 = 0.25) at α = 0.05 in the

regression analyses with up to seven predictors, based on a priori power

analysis using G*Power (Faul et al., 2009).

3.2.2. Measures

Independent Variables: CAS Implementation

The researchers developed the Complex Adaptive Systems Implementation Scale (CASIS) to measure implementation of CAS principles. The scale was validated through a pilot study with 8 organizations not included in the main sample (Cronbach’s α = 0.87). The CASIS comprises four subscales corresponding to the CAS principles:

Living Systems Implementation (LSI): Measures distributed decision-making, permeable boundaries, and other living systems characteristics (8 items, α = 0.84)

Self-Maintenance Implementation (SMI): Assesses continuous learning practices, identity preservation, and adaptive balancing (7 items, α = 0.81)

Deep Foundations Implementation (DFI): Measures diversity, redundancy, social capital, and resource distribution (9 items, α = 0.86)

Feedback Systems Implementation (FSI): Assesses presence and effectiveness of balancing and reinforcing feedback mechanisms (8 items, α = 0.83)

Data were collected through structured interviews with organizational leaders (minimum 3 per organization) and analysis of organizational documentation. Responses were coded by two independent raters (inter-rater reliability = 0.89). To mitigate common method bias, we triangulated interview data with documentation analysis and collected CASIS data from multiple respondents per organization (Podsakoff et al., 2012).

Dependent Variables: Resilience Metrics

- 1.

Disruption Recovery Rate (DRR): Time to return to pre-disruption performance levels following significant market disruptions (normalized across industries)

- 2.

Adaptive Capacity Index (ACI): Composite measure of innovation implementation rate, strategic pivot frequency, and environmental sensing capability (The ESC component of ACI specifically measures formalized sensing processes and tools, which is distinct from the broader environmental sensing capability examined in the mediation analysis (see section 4.4)

- 3.

Operational Stability Metric (OSM): Variance in key performance indicators during industry disruptions relative to industry averages

These metrics were collected from organizational records, with appropriate controls for industry-specific factors. For each industry, we identified sector-specific normalization factors based on typical recovery patterns, innovation rates, and performance volatility, allowing for meaningful cross-industry comparison.

Control Variables

Control variables included organization size (log of employee count), age (years since founding), industry (dummy coded), financial resources (revenue/assets, standardized within industry), and market position (relative market share within primary industry).

3.2.3. Analysis

Hierarchical multiple regression was used to examine relationships between CAS implementation and resilience metrics, controlling for organizational characteristics. Mediation analyses were also conducted using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2018) to identify mechanisms through which CAS principles influence resilience outcomes. To assess robustness, we conducted sensitivity analyses with alternative model specifications and tested for multicollinearity, heteroscedasticity, and influential outliers.

3.3. Qualitative Study (Phase 2)

3.3.1. Sample

From the 42 organizations in the quantitative sample, 12 were selected for in-depth case studies using maximum variation sampling to ensure diverse implementation approaches. The sample included 3 organizations from each industry, with varying levels of CAS implementation (high, medium, low) based on CASIS scores.

3.3.2. Data Collection

For each organization, the researchers conducted:

Semi-structured interviews with 8-12 stakeholders across hierarchical levels (total n=118)

Document analysis of strategy documents, implementation plans, and internal communications

Observation of key organizational processes (where permitted)

Interviews focused on implementation approaches, challenges, contextual factors, and perceived outcomes. All interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded. The interview protocol was informed by Phase 1 findings, with particular attention to understanding the mechanisms identified in the mediation analysis and exploring contextual factors influencing implementation effectiveness.

Observational data were collected using a structured protocol focusing on decision-making processes, information flows, and responses to unexpected events. Field notes documented both descriptive observations and researcher reflections, with attention to how CAS principles manifested in organizational practices.

3.3.3. Analysis

Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006) was used to identify patterns in implementation approaches and contextual factors. Initial coding was conducted independently by two researchers, followed by collaborative refinement of themes. Constant comparative analysis was employed to identify similarities and differences across cases.

The coding framework included both deductive codes derived from the theoretical framework and inductive codes emerging from the data. Regular team meetings were held to resolve coding discrepancies, with an external auditor reviewing the coding process to enhance trustworthiness. Member checking was conducted with key informants from each organization to verify interpretations.

3.4. Integration and Framework Development (Phase 3)

Phase 3 integrated the quantitative and qualitative findings to develop a comprehensive implementation framework. This integration followed Fetters et al.’s (2013) guidelines for mixed-methods integration, using joint displays, data transformation, and narrative weaving approaches to identify patterns across methods.

We created case-variable matrices mapping qualitative themes against quantitative metrics, allowing for systematic comparison across organizations. We also transformed qualitative data into quantified codes to enable direct comparison with statistical findings. This integration process was iterative, with the research team collaboratively refining the framework based on converging evidence and testing it against outlier cases.

3.5. Visual Representation Development

As part of the analysis and communication strategy, we developed three key visual representations to illustrate the research findings:

Conceptual Model (Figure 1): This figure visually represents the theoretical relationships between CAS principles, mediating mechanisms, resilience outcomes, and contextual factors. It was developed during the theoretical framework phase and guided the empirical investigation.

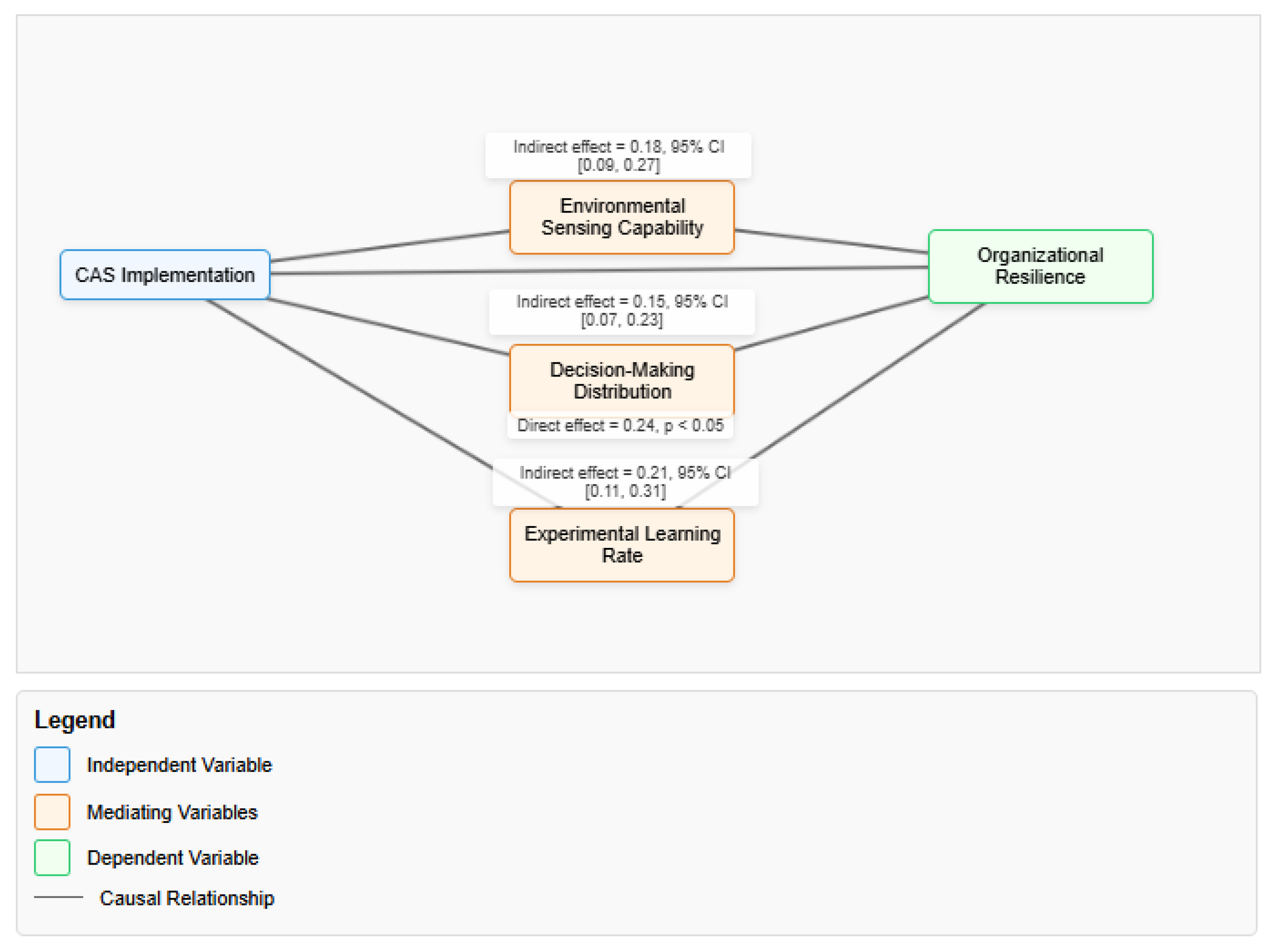

Mediation Analysis (Figure 2): Based on the quantitative findings, this figure illustrates the statistical relationships between CAS implementation and organizational resilience, showing both direct effects and indirect effects through the three mediating variables.

Implementation Framework (Figure 3): This figure synthesizes both quantitative and qualitative findings into a practical implementation guide. It was iteratively refined during the integration phase to accurately represent the pathways, contextual influences, and feedback loops identified in the research.

Figure 2.

Mediation Analysis of CAS Implementation and Organizational Resilience.

Figure 2.

Mediation Analysis of CAS Implementation and Organizational Resilience.

Figure 3.

Integrated Framework for CAS Implementation.

Figure 3.

Integrated Framework for CAS Implementation.

These visual representations serve both analytical and communication purposes, helping to clarify complex relationships and translate research findings into actionable insights.

Having established the research design and methodological approach, the following section will now present the findings from the mixed-methods investigation, beginning with descriptive statistics and followed by analyses addressing each of the three primary research questions.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and correlations for all key variables. The correlation matrix reveals significant relationships between CAS implementation measures and resilience metrics, providing initial support for the conceptual model. All four CAS principles show moderate to strong positive correlations with resilience metrics, with particularly strong relationships between Living Systems Implementation and Adaptive Capacity (r = 0.58, p < 0.001) and between Feedback Systems Implementation and Operational Stability (r = 0.53, p < 0.001).

Notable relationships among control variables include negative correlations between organization size and Living Systems Implementation (r = -0.31, p < 0.05) and between age and Adaptive Capacity (r = -0.33, p < 0.01), suggesting potential challenges in implementing certain CAS principles in larger, more established organizations.

4.2. CAS Implementation and Resilience Outcomes (RQ1)

Hierarchical regression analysis revealed significant positive relationships between overall CAS implementation (CASIS score) and all three resilience metrics (

Table 2). Organizations with higher CASIS scores demonstrated faster disruption recovery (β = -0.42, p < 0.01), higher adaptive capacity (β = 0.51, p < 0.001), and greater operational stability during disruptions (β = -0.38, p < 0.01), even after controlling for organizational characteristics.

These results provide strong support for RQ1, confirming that organizations with higher implementation of CAS principles demonstrate greater resilience across multiple dimensions. The significant R2 changes (ranging from 0.14 to 0.26) indicate that CAS implementation explains substantial variance in resilience outcomes beyond organizational characteristics.

Control variables showed some significant effects: larger and older organizations demonstrated lower adaptive capacity (β = -0.21, p < 0.05 and β = -0.28, p < 0.01, respectively); healthcare organizations showed slower disruption recovery and lower operational stability; and technology sector organizations showed higher adaptive capacity and operational stability. However, CAS implementation remained a significant predictor even after accounting for these effects.

4.3. Relative Impact of CAS Principles (RQ2)

Analysis of individual CASIS subscales revealed differential impact across resilience metrics (

Table 3). Deep Foundations Implementation (DFI) had the strongest relationship with Disruption Recovery Rate (β = -0.47, p < 0.001, where negative coefficients indicate faster recovery). Living Systems Implementation (LSI) most strongly predicted Adaptive Capacity Index (β = 0.53, p < 0.001). Feedback Systems Implementation (FSI) showed the strongest relationship with Operational Stability (β = -0.49, p < 0.001, where negative coefficients indicate greater stability).

These findings address RQ2 by demonstrating that different CAS principles contribute differentially to specific aspects of resilience:

Deep Foundations (diversity, redundancy, social capital) particularly enhance recovery from disruptions

Living Systems characteristics (distributed intelligence, permeable boundaries) most strongly influence adaptive capacity and innovation

Feedback Systems most strongly contribute to maintaining operational stability during disruptions

These differential relationships support the conceptual model’s proposition that CAS principles operate through distinct mechanisms to enhance different aspects of organizational resilience.

4.4. Mediation Analysis: Mechanisms of Influence

Mediation analysis revealed that the relationship between CAS implementation and resilience outcomes was partially mediated by three organizational capabilities (

Figure 2). As shown in

Figure 2, the analysis identified significant indirect effects through:

Environmental sensing capability (indirect effect = 0.18, 95% CI [0.09, 0.27])

Decision-making distribution (indirect effect = 0.15, 95% CI [0.07, 0.23])

Experimental learning rate (indirect effect = 0.21, 95% CI [0.11, 0.31])

These findings suggest specific mechanisms through which CAS principles enhance organizational resilience. Environmental sensing capabilities enable organizations to detect changes earlier and respond more appropriately. Distributed decision-making allows for faster local responses to disruptions. Experimental learning facilitates rapid adaptation through testing and refining approaches.

The direct effect of CAS implementation on resilience remained significant even after accounting for these mediators (direct effect = 0.24, p < 0.05), suggesting that additional mechanisms may also contribute to the relationship.

It’s important to note that the environmental sensing capability measured in the mediation analysis represents a broader organizational capability than the environmental sensing component (ESC) used within the Adaptive Capacity Index. While related, the environmental sensing capability in the mediation analysis encompasses the organization’s overall ability to detect and interpret environmental changes, whereas the ESC component of ACI focuses specifically on formal sensing processes and tools.

4.5. Implementation Approaches and Contextual Factors (RQ3)

Thematic analysis of case studies revealed patterns in implementation approaches and contextual factors influencing CAS effectiveness. Three distinct implementation approaches emerged, each associated with specific organizational contexts and outcomes.

4.5.1. Implementation Approaches

Incremental Integration

Organizations with high historical centralization and hierarchy (particularly in manufacturing and financial services) achieved better results through gradual implementation, beginning with:

Creating protected spaces for experimentation

Implementing tiered authority systems with clear boundaries

Gradually expanding autonomy as capabilities developed

A manufacturing executive explained: “We couldn’t just flip a switch to distributed decision-making. We started with quality circles where teams could make specific improvements, then gradually expanded their authority as they demonstrated capability.” (Manufacturing-7)

Another executive from a financial services organization described their approach: “We identified specific decision domains where we could safely distribute authority while maintaining compliance. Starting with customer experience decisions allowed teams to build confidence while we maintained centralized control in regulatory areas.” (Financial-5)

This approach was particularly effective in organizations with:

Strong hierarchical cultures

Limited prior experience with distributed authority

Regulated environments requiring careful compliance

Established operational processes

Native Integration

Younger organizations (primarily in technology) often integrated CAS principles into their founding DNA through:

Purpose-driven organizing structures

Default distribution of authority with clear exception processes

Embedded experimental processes

A technology founder described: “We built complexity thinking into our organizational design from day one. Our structure assumes distributed intelligence and rapid adaptation as the default mode.” (Technology-2)

The CEO of a healthcare startup elaborated: “Rather than creating separate innovation processes, we designed our core operating model around experimentation. Every team has both operational metrics and learning metrics, with learning treated as a primary outcome rather than a nice-to-have.” (Healthcare-9)

This approach was characteristic of:

Startup and young organizations

Organizations with founding leaders familiar with complexity principles

Knowledge-intensive industries

Digital-native companies

Table 4 provides a comparative analysis of these three implementation approaches, highlighting their key characteristics, advantages, challenges, and contextual fit.

4.5.2. Contextual Factors

Several contextual factors influenced CAS implementation effectiveness across all approaches:

Regulatory Environment

Highly regulated industries required careful boundary-setting around compliance issues while enabling autonomy in other domains. Organizations in these contexts developed what one participant called “bounded autonomy systems” that clearly delineated non-negotiable requirements while encouraging adaptation elsewhere.

One healthcare organization created a “compliance foundation” that clearly identified regulatory requirements as non-negotiable, while encouraging experimental approaches in service delivery, administrative processes, and patient experience. This allowed them to maintain regulatory compliance while fostering innovation in other areas.

As the Chief Compliance Officer explained: “We created very clear guardrails around regulatory requirements, then actively encouraged experimentation within those boundaries. This clarity actually increased innovation because people felt safe knowing exactly where the boundaries were.” (Healthcare-3)

Cultural Context

Both national and organizational culture significantly influenced implementation. Organizations in hierarchical or uncertainty-avoidant cultures required more structured approaches to distributed authority and experimentation. As one financial services executive noted: “In our culture, people expect clear direction. We had to create very explicit processes for autonomous decision-making with clear parameters.” (Financial-3)

Cultural factors particularly influenced the pace of implementation, with organizations in high power-distance cultures typically requiring longer transition periods and more explicit frameworks for distributed authority. Successful implementations in these contexts emphasized clarity of boundaries and decision rights rather than undefined autonomy.

A manufacturing leader observed: “We couldn’t just tell people ‘be more autonomous’ and expect results. Our culture values clarity and structure, so we developed a detailed decision rights framework that clearly specified who could make which decisions and when escalation was required.” (Manufacturing-2)

Digital Maturity

Organizations’ technological capabilities influenced implementation effectiveness, particularly regarding feedback systems and distributed decision-making. Those with advanced digital infrastructure could implement more sophisticated sensing and feedback mechanisms, while those with limited digital capabilities required analog approaches to CAS principles.

A manufacturing organization with limited digital infrastructure successfully implemented CAS principles by creating physical information radiators, regular in-person feedback sessions, and visual management systems. While less sophisticated than digital approaches, these methods effectively supported distributed decision-making and rapid feedback cycles.

The operations director explained: “Not having advanced analytics didn’t stop us from implementing feedback systems. We created physical dashboards throughout the facility and established daily huddles where teams reviewed performance and identified improvement opportunities.” (Manufacturing-5)

Organizational Size and Age

Size and age influenced both implementation approach and effectiveness. Larger organizations typically required more structured approaches with clear boundary conditions and explicit decision rights. Older organizations often faced greater implementation challenges due to entrenched practices and cultural inertia.

However, size and age were not deterministic. Several large, established organizations successfully implemented CAS principles through well-designed incremental approaches that recognized and addressed cultural and structural constraints. As one executive noted: “Size isn’t destiny. It’s about how you design your systems to enable local responsiveness within a coherent whole.” (Manufacturing-3)

4.5.3. Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Case studies revealed common implementation challenges and effective solutions:

Resistance to Distributed Authority

Both managers (fearing loss of control) and employees (fearing increased responsibility) often initially resisted distributed authority. Effective solutions included:

Gradual implementation with clear boundaries

Skill development before authority distribution

Recognition systems for autonomous decision-making

Explicit decision frameworks clarifying authority domains

A technology company addressed this challenge by developing a “decision rights matrix” that clearly specified which decisions could be made at which levels, with gradually expanding autonomy as teams demonstrated capability. This clarity reduced anxiety among both managers and employees while enabling progressive implementation.

The HR director reflected: “We discovered that resistance wasn’t just from managers—many employees were uncomfortable with the ambiguity of increased autonomy. Creating clear decision frameworks with graduated authority levels made the transition much smoother for everyone.” (Technology-6)

Feedback System Dysfunction

Many organizations struggled with feedback system implementation, particularly regarding psychological safety for honest feedback. Successful approaches included:

Leadership modeling of vulnerability

“No-blame” postmortem processes

Celebration of productive failures

Structured feedback protocols separating observation from evaluation

A healthcare organization implemented a “learning from failure” protocol that separated event analysis from performance evaluation. This structural separation created psychological safety for honest reporting while maintaining accountability for improvement actions.

The Chief Medical Officer explained: “We completely redesigned our incident reporting process to focus on system learning rather than individual blame. The key innovation was separating the learning process from performance evaluation, which dramatically increased reporting of near-misses and small failures before they became major problems.” (Healthcare-11)

Resource Allocation Tensions

Building resilience foundations (particularly redundancy) often created tension with short-term efficiency goals. Organizations addressed this through:

Portfolio approaches to resilience investment

Clear articulation of resilience ROI

Strategic framing of resilience as competitive advantage

Incremental building of redundancy in critical areas

A healthcare leader explained: “We had to make the business case for redundancy. We analyzed the cost of past disruptions and demonstrated how relatively small investments in backup systems would pay for themselves in just one significant disruption event.” (Healthcare-11)

A financial services executive described their approach: “Rather than seeing resilience investments as pure cost, we reframed them as strategic insurance that enabled more aggressive growth in other areas. By having strong resilience foundations, we could take bigger risks in market expansion knowing we could weather disruptions.” (Financial-7)

Efficiency-Resilience Paradox

Organizations frequently struggled with balancing efficiency and resilience objectives. Successful approaches included:

Explicit recognition and discussion of the paradox

Different metrics for efficiency versus resilience

Contextual application of principles based on criticality

Viewing redundancy as capability insurance rather than waste

A financial services organization developed dual metrics for teams—efficiency metrics for routine operations and resilience metrics for critical functions and disruption periods. This dual-metric approach acknowledged the different requirements for different contexts rather than forcing a single optimization approach.

The COO noted: “The breakthrough came when we stopped seeing efficiency and resilience as opposites and started seeing them as different operating modes requiring different optimization approaches. We now explicitly design our systems to shift between these modes based on context.” (Financial-1)

4.6. Integrated Framework for CAS Implementation

Integrating quantitative and qualitative findings, we developed a comprehensive framework for CAS implementation (

Figure 3). The framework illustrates the relationships between assessment, context analysis, implementation strategy, capability development, measurement, and feedback loops. As shown in

Figure 3, the framework includes:

Assessment Phase: Evaluating current CAS implementation using the CASIS instrument and analyzing organizational context to establish a baseline

Context Analysis: Examining organizational characteristics including size, industry, culture, and digital maturity to determine which implementation approach will be most effective

Implementation Strategy Selection: Choosing an implementation approach (incremental, comprehensive, or native) based on organizational context and assessment results

Capability Development: Building environmental sensing, distributed decision-making, and experimental learning capabilities through structured initiatives tailored to the selected implementation approach

Monitoring and Adaptation: Using feedback systems to evaluate progress against resilience metrics and adjust implementation approach as needed

The framework emphasizes tailoring implementation to organizational context while focusing on developing core capabilities that mediate between CAS principles and resilience outcomes. Importantly, the framework features feedback loops that enable continuous adaptation of the implementation approach based on emerging outcomes.

The framework goes beyond a linear implementation process by illustrating how CAS principles themselves should inform the implementation approach—emphasizing experimentation, learning, and adaptation throughout the process. This creates a meta-level application of complexity principles to the implementation process itself.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The findings provide empirical validation for the application of CAS principles in organizational contexts, addressing a significant gap in the literature. The results support the theoretical proposition that organizations demonstrating CAS characteristics exhibit greater resilience during disruptions (supporting RQ1).

The differential impact of CAS principles on resilience metrics (addressing RQ2) suggests that different aspects of resilience require different complex systems capabilities. Deep foundations (diversity, redundancy) particularly enhance recovery from disruptions, while living systems characteristics (distributed intelligence, permeable boundaries) most strongly influence adaptive capacity. This advances understanding of the specific mechanisms through which CAS principles enhance organizational functioning.

The mediation analysis further refines this understanding by identifying specific organizational capabilities that translate CAS implementation into resilience outcomes. The significance of environmental sensing capability, decision-making distribution, and experimental learning rate as mediating factors aligns with theoretical work by Teece (2018) on dynamic capabilities and Schoemaker et al. (2018) on strategic foresight, while offering greater specificity about how these capabilities operate in practice.

The identification of distinct implementation approaches (incremental, comprehensive, native) contributes to theoretical understanding of how abstract CAS principles translate into organizational practice (addressing RQ3). These approaches offer a more nuanced view than previous literature, which often implied a universal implementation method. This finding aligns with recent work on contextual implementation of management innovations (Ansari et al., 2022) and extends it specifically to CAS theory.

The findings also contribute to understanding the paradoxes and tensions in CAS implementation, particularly the efficiency-resilience paradox. Rather than viewing this as a simple trade-off, the research suggests that organizations can develop contextual approaches that optimize differently across functions and time periods. This nuanced view extends organizational paradox theory (Smith & Lewis, 2011) by demonstrating how paradoxes manifest specifically in complex adaptive systems and how organizations successfully navigate them.

While the findings predominantly highlight the benefits of CAS implementation, the research also revealed potential tensions and challenges that warrant critical consideration. The efficiency-resilience paradox, in particular, represents a significant challenge for organizations implementing CAS principles. The qualitative data suggest that organizations sometimes experience short-term performance declines during implementation, especially when building redundancy and diversity at the expense of immediate efficiency. Additionally, distributed decision-making, while enhancing adaptive capacity, can sometimes lead to coordination difficulties and strategic inconsistency without appropriate boundary conditions. These observations align with complexity leadership theory, which acknowledges the inherent tensions between administrative, adaptive, and enabling leadership functions (Uhl-Bien & Arena, 2018). Future research should further explore these tensions and potential downsides of CAS implementation, particularly examining whether certain organizational contexts might be better served by alternative approaches in specific situations.

5.2. Integration with Existing Theoretical Perspectives

The findings demonstrate how CAS theory complements and extends existing theoretical perspectives on organizational resilience:

Resource-Based View: The identification of deep foundations (diversity, redundancy, social capital) as particularly important for recovery from disruptions extends RBV by highlighting specific resource configurations that enhance resilience. However, the findings also emphasize that static resource configurations are insufficient—organizations must develop dynamic capabilities that enable resource reconfiguration.

Dynamic Capabilities: The mediation analysis identifying environmental sensing, distributed decision-making, and experimental learning as key mechanisms aligns with dynamic capabilities theory while providing greater specificity about how these capabilities operate in practice. The findings suggest that effective dynamic capabilities emerge not just from deliberate managerial action but from appropriate system design that enables distributed intelligence and self-organization.

High Reliability Organization Theory: The findings on feedback systems and deep foundations complement HRO theory by demonstrating how these principles contribute to reliability in non-high-risk contexts. However, the results extend beyond reliability to adaptive capacity, showing how similar principles enable not just consistent performance but innovation and transformation.

Institutional Theory: The findings on contextual factors influencing implementation effectiveness acknowledge the role of institutional pressures but demonstrate that organizations can successfully implement CAS principles even in constraining institutional environments through careful design and boundary-setting.

By integrating CAS theory with these established frameworks, the research provides a more comprehensive understanding of organizational resilience that acknowledges both deliberate design and emergent adaptation, internal capabilities and external contexts, and stability and change dynamics.

5.3. Practical Implications

The findings provide several practical implications for organizational leaders seeking to enhance resilience through CAS principles.

First, the CASIS instrument offers a diagnostic tool for assessing current CAS implementation and identifying specific areas for improvement. Organizations can use this assessment to benchmark their capabilities and develop targeted interventions.

Second, the differential impact of CAS principles on resilience metrics enables organizations to prioritize implementation based on their specific resilience needs. Organizations primarily concerned with recovery from disruptions should emphasize deep foundations, while those focused on innovation and adaptation should prioritize living systems characteristics.

Third, the identification of three distinct implementation approaches provides practical guidance for selecting an appropriate strategy based on organizational context. Rather than a one-size-fits-all approach, organizations can select implementation strategies aligned with their history, culture, and capabilities.

Fourth, the mediation analysis highlights three specific organizational capabilities worth developing: environmental sensing, distributed decision-making, and experimental learning. These capabilities represent actionable targets for organizational development initiatives.

Finally, the integrated framework provides a structured approach to CAS implementation, guiding organizations through assessment, strategy selection, capability development, and ongoing adaptation.

5.4. Implementation Guidance for Practitioners

Based on the research findings, the following guidance is offered for practitioners considering CAS implementation:

Evaluate current CAS implementation using the CASIS instrument

Analyze organizational context (size, age, industry, culture, digital maturity)

Identify specific resilience needs based on industry challenges and organizational strategy

For established organizations with hierarchical cultures: Consider Incremental Integration

For organizations at strategic inflection points: Consider Comprehensive Transformation

For new organizations or major new ventures: Consider Native Integration

Adapt approach based on specific contextual factors identified in assessment

Focus on capabilities that mediate between CAS principles and resilience outcomes

Design specific initiatives to develop environmental sensing capabilities

Create structures and processes that enable distributed decision-making

Establish systems for experimental learning and knowledge dissemination

Address anticipated challenges proactively with specific mitigation strategies

Ensure executive alignment and commitment to selected approach

Develop clear communication strategy explaining rationale and process

Identify and empower change agents throughout the organization

Create appropriate measurement systems to track progress

Follow implementation plan while remaining responsive to feedback

Create feedback mechanisms to monitor progress and identify barriers

Celebrate early wins to build momentum

Adjust approach based on emerging challenges and opportunities

Embed CAS principles in organizational systems and processes

Develop mechanisms to maintain principles during leadership transitions

Continue to evolve implementation as organization and environment change

Regularly reassess using CASIS to identify new improvement opportunities

5.5. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that suggest directions for future research.

First, while the sample included diverse organizations, it was not randomly selected and may not be fully representative. Future research should test these findings with larger, more representative samples, potentially including international organizations to explore cultural variations more systematically.

Second, while we collected longitudinal data on organizational outcomes, the implementation assessments were cross-sectional. Future research should examine CAS implementation and outcomes longitudinally to better establish causality and explore implementation trajectories over time. Longitudinal studies could also examine how CAS implementation evolves as organizations grow and mature.

Third, the measures, while validated, rely partially on self-reported data. Future research should incorporate more objective measures of CAS implementation and explore alternative measurement approaches, potentially including network analysis to assess information flows and decision patterns.

Fourth, while we identified contextual factors influencing implementation, their complex interactions could not be fully explored. Future research should examine how multiple contextual factors jointly influence CAS implementation effectiveness, potentially using configurational approaches like qualitative comparative analysis to identify successful combinations of factors.

Fifth, the study focused on organizational-level outcomes. Future research should explore multi-level effects, examining how CAS principles at organizational levels influence team and individual outcomes and vice versa. This could include investigating how individual leadership behaviors interact with system-level designs to enable or constrain adaptation.

Sixth, while the statistical power analysis indicated adequate power for detecting medium effect sizes, the sample size of 42 organizations remains relatively modest for some of the more complex statistical analyses conducted, particularly the mediation analyses with multiple predictors. This limitation potentially affects the robustness and generalizability of the quantitative findings. Although we employed various analytical techniques to enhance reliability, including bootstrapping for mediation analyses and sensitivity analyses with alternative model specifications, the results should be interpreted with appropriate caution. Future research with larger samples would help validate the patterns observed in the data and potentially reveal more nuanced relationships among variables.

Finally, future research should explore potential downsides or limitations of CAS implementation. While the findings predominantly showed positive outcomes, there may be contexts or conditions under which CAS principles are less effective or even counterproductive. Identifying these boundary conditions would further refine the understanding of when and how to apply these principles.

6. Conclusion

This study provides empirical evidence that organizations implementing Complex Adaptive Systems principles demonstrate greater resilience during disruptive events. The findings validate the practical value of CAS theory for organizational design and management while advancing theoretical understanding of how complex systems principles translate into organizational practice.

The four CAS principles examined—organizations as living systems, self-maintaining systems, systems with deep foundations, and systems with effective feedback mechanisms—all contribute significantly to organizational resilience, though their relative impact varies across different resilience dimensions. These relationships are mediated by three key organizational capabilities: environmental sensing, distributed decision-making, and experimental learning.

The identification of three distinct implementation approaches—incremental integration, comprehensive transformation, and native integration—highlights the importance of contextual factors in successful implementation. Rather than a universal prescription, effective CAS implementation requires tailoring approaches to specific organizational contexts, including industry, culture, size, age, and digital maturity.

As organizations continue to navigate increasingly complex and volatile environments, the ability to function as adaptive systems becomes increasingly critical. This research suggests that by embracing complexity rather than attempting to simplify or control it, organizations can develop the resilience needed to thrive amid disruption. However, successful implementation requires thoughtful design, contextual adaptation, and navigation of inherent tensions and paradoxes.

By providing both theoretical insights and practical guidance, this research aims to bridge the gap between complexity science and organizational practice, enabling more organizations to develop the adaptive capacity needed for sustainable success in complex environments.

Appendix A: Research Instruments

A.1 Complex Adaptive Systems Implementation Scale (CASIS)

The CASIS is designed to measure the degree to which organizations have implemented complex adaptive systems principles. The instrument should be administered to multiple organizational leaders (minimum 3 per organization) to ensure reliability. Respondents rate each item on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Not at all implemented, 7 = Fully implemented). The instrument can be administered via structured interview or online survey.

The CASIS comprises four subscales corresponding to the CAS principles, with a total of 32 items:

Decision-making authority is distributed throughout the organization rather than concentrated at the top.

Employees at all levels have autonomy to respond to situations within clearly defined boundaries.

Information flows freely across departmental and hierarchical boundaries.

The organization maintains permeable boundaries with its external environment, actively exchanging information.

Teams are cross-functional and can self-organize to address emerging challenges.

Roles and responsibilities adapt based on context rather than being rigidly defined.

Local units can develop unique approaches to implementing organizational strategy.

Leaders focus on creating enabling conditions rather than controlling outcomes.

The organization has clearly articulated its core identity and purpose.

Continuous learning is embedded in regular work practices.

The organization simultaneously maintains stability in core values while encouraging flexibility in strategies.

Resources are allocated both to exploit current capabilities and explore new possibilities.

The organization regularly reviews and refines its identity in response to changing environments.

Knowledge and expertise are actively transferred across the organization.

Processes exist to identify and incorporate emerging practices into standard operations.

The organization deliberately builds diversity in perspectives, backgrounds, and thinking styles.

Critical functions have redundant systems or personnel to ensure continuity.

Resources are distributed across the organization rather than centralized.

The organization invests in building strong relationship networks across departments.

Psychological safety is actively fostered throughout the organization.

The organization maintains strategic reserves (financial, talent, etc.) for unexpected challenges.

Failure is treated as a learning opportunity rather than cause for punishment.

The organization regularly tests its resilience through simulations or scenario planning.

Decision processes deliberately incorporate diverse perspectives.

The organization has systems to rapidly detect changes in its environment.

Feedback loops provide information at multiple time scales (short, medium, and long-term).

The organization regularly measures outcomes against expectations and adjusts accordingly.

Information about failures and successes is systematically collected and shared.

Formal processes exist for testing and validating new ideas before full implementation.

The organization can rapidly amplify successful innovations across units.

The organization has mechanisms to identify and counter dysfunctional behaviors or processes.

Stakeholder feedback is systematically collected and incorporated into decision-making.

Individual item scores range from 1-7

Subscale scores are calculated as the mean of all items in that subscale

Total CASIS score is calculated as the mean of all four subscale scores

-

Interpretation guidelines:

- ○

1.0-2.9: Low CAS implementation

- ○

3.0-4.9: Moderate CAS implementation

- ○

5.0-7.0: High CAS implementation

A.2 Resilience Metrics Measurement Protocol

This protocol standardizes the collection of three key resilience metrics across different organizations and industries.

Definition: Time required to return to pre-disruption performance levels following significant market disruptions, normalized across industries.

Identify significant disruption events relevant to the organization in the past 3 years

-

For each event, record:

- ○

Date of disruption onset

- ○

Key performance indicators (KPIs) at pre-disruption baseline

- ○

Date when KPIs returned to within 5% of baseline

- ○

Calculate recovery time in days

Normalize recovery times using industry-specific factors derived from the research dataset. For each industry, we calculated average recovery times for similar disruption events, creating a standardized baseline. This approach allows for meaningful cross-industry comparison based on internal study data rather than external sources.

DRR = (Organization’s recovery time / Industry average recovery time) × 100

Definition: Composite measure of innovation implementation rate, strategic pivot frequency, and environmental sensing capability.

-

Innovation Implementation Rate (IIR):

- ○

Record number of significant innovations implemented in past 24 months

- ○

Calculate implementation efficiency: % of proposed innovations successfully implemented

- ○

Standardize against organization size and industry

-

Strategic Pivot Frequency (SPF):

- ○

Document major strategic shifts in past 36 months

- ○

Rate each pivot’s effectiveness (1-5 scale)

- ○

Calculate weighted pivot score

-

Environmental Sensing Capability (ESC):

- ○

Administer Environmental Sensing Assessment (12 items, 7-point scale)

- ○

Calculate mean score

ACI = (0.4 × IIR) + (0.3 × SPF) + (0.3 × ESC)

Definition: Variance in key performance indicators during industry disruptions relative to industry averages.

OSM = Average of stability ratios across all operational metrics

Appendix B: Case Study Protocol

B.1 Purpose

This protocol guides the collection and analysis of qualitative data to understand CAS implementation approaches, contextual factors, and outcomes.

B.2 Case Selection Criteria

Organizations for case studies are selected based on:

B.3 Data Collection Methods

B.3.1 Semi-Structured Interviews

Senior executives (2-3)

Middle managers (2-3)

Front-line employees (2-3)

Support function representatives (1-2)

External stakeholders where relevant (1)

-

Background and Context

- ○

“Please describe your role and how long you’ve been with the organization.”

- ○

“How would you characterize your organization’s approach to managing complexity and change?”

-

Implementation Approaches

- ○

“What specific practices or systems has your organization implemented to enhance adaptability?”

- ○

“How did the implementation process unfold? Was it planned or emergent?”

- ○

“What barriers did you encounter during implementation and how were they addressed?”

-

Living Systems Principle

- ○

“How are decisions made in your organization? To what extent is authority distributed?”

- ○

“How does information flow across departmental or hierarchical boundaries?”

- ○

“How does your organization interact with its external environment?”

-

Self-Maintenance Principle

- ○

“How does your organization maintain its core identity while adapting to change?”

- ○

“How do you balance stability and flexibility in your operations?”

- ○

“What processes support continuous learning and knowledge transfer?”

-

Deep Foundations Principle

- ○

“How does your organization approach diversity in perspectives and capabilities?”

- ○

“What redundancies or backup systems exist for critical functions?”

- ○

“How are relationships and trust developed across the organization?”

-

Feedback Systems Principle

- ○

“What mechanisms exist to detect changes in your environment?”

- ○

“How does the organization gather and respond to feedback?”

- ○

“How are successful innovations identified and scaled?”

-

Outcomes and Challenges

- ○

“What benefits has your organization realized from these approaches?”

- ○

“What metrics or indicators do you use to assess adaptability and resilience?”

- ○

“What ongoing challenges do you face in implementing these principles?”

-

Contextual Factors

- ○

“What aspects of your organization’s culture, history, or industry influence your approach?”

- ○

“How have external factors shaped your implementation strategy?”

- ○

“What resources or capabilities have been most important for successful implementation?”

B.4 Data Analysis Procedures

B.4.1 Coding Process

Initial coding: Open coding of all data sources

Focused coding: Organization of codes into themes aligned with research questions

Cross-case analysis: Identification of patterns across organizations

B.4.2 Quality Assurance Procedures

Dual independent coding of 25% of data to establish reliability

Regular research team meetings to resolve coding discrepancies

Triangulation across data sources

Member checking with organizational participants

Audit trail documenting all analytical decisions

References

- Adler, P.S.; Kwon, S.W. Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review 2002, 27, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, S.; Whetten, D.A. Organizational identity. Research in Organizational Behavior 1985, 7, 263–295. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, P.; Maguire, S.; McKelvey, B. The SAGE Handbook of Complexity and Management; SAGE Publications, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, S.; Reinecke, J.; Spaan, A. Contextualizing management innovations: Investigating the adoption and adaptation of management practices across cultural and geographical boundaries. Research in the Sociology of Organizations 2022, 78, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Argote, L.; Miron-Spektor, E. Organizational learning: From experience to knowledge. Organization Science 2011, 22, 1123–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benbya, H.; Nan, N.; Tanriverdi, H.; Yoo, Y. Complexity and information systems research in the emerging digital world. MIS Quarterly 2023, 44, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Berger-Tal, O.; Greggor, A.L. The behavior-adaptation continuum and the role of learning in rapid environmental change. Behavioral Ecology 2023, 34, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite, J.; Churruca, K.; Long, J.C.; Ellis, L.A.; Herkes, J. When complexity science meets implementation science: A theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Medicine 2018, 16, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches; Sage publications, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dooley, K.J. Using complexity science to manage organizations: A complex adaptive systems approach. In Handbook of Research Methods in Complexity Science; Mitleton-Kelly, E., Paraskevas, A., Day, C., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing, 2017; pp. 316–334. [Google Scholar]

- Duchek, S. Organizational resilience: A capability-based conceptualization. Business Research 2020, 13, 215–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainshmidt, S.; Andrews, D.S.; Gaur, A.; Schotter, A. Reclaiming dynamism: A renewed research agenda for dynamic capabilities. Journal of Management Studies 2023, 60, 783–813. [Google Scholar]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—principles and practices. Health Services Research 2013, 48(6pt2), 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folke, C.; Biggs, R.; Norström, A.V.; Reyers, B.; Rockström, J. Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecology and Society 2016, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gell-Mann, M. Complexity and complex adaptive systems; Oxford University Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hannan, M.T.; Freeman, J. Organizational ecology in the digital age: Revised foundations for a theory of organizations as complex adaptive systems. Annual Review of Sociology 2023, 49, 211–232. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Heylighen, F.; Beigi, S.; Veloz, T. The mathematical foundations of resilience: Anticipation, resistance, recovery and adaptation. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 2022, 64, 102019. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, J.H. Complexity: A very short introduction; Oxford University Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kaivo-oja, J.; Ahokas, I.; Sauer, A.; Normann, H. Advanced digital organizational resilience: Antifragility, resilience, agility, and robustness intelligence. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2022, 178, 121588. [Google Scholar]

- Kreiner, G.E.; Murphy, C.; Sheep, M.L. Advancing research on organizational identity change and plasticity. Journal of Management 2022, 48, 1474–1497. [Google Scholar]

- Laloux, F. Reinventing organizations: A guide to creating organizations inspired by the next stage of human consciousness; Nelson Parker, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lavie, D.; Stettner, U.; Tushman, M.L. Organizational ambidexterity: Past, present, and future. Academy of Management Annals 2022, 16, 143–194. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.Y.; Edmondson, A.C. Self-managing organizations: Exploring the limits of less-hierarchical organizing. Research in Organizational Behavior 2017, 37, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M.K. Resilience in business and management research: A review of influential publications and a research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews 2017, 19, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Zeng, J.; Li, X. How digitalization enhances organizational resilience: Unpacking the multi-level mechanisms. Journal of Business Research 2023, 157, 113591. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães, R.; Sanchez, R. Autopoiesis in organization theory and practice; Emerald Group Publishing, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Maturana, H.R.; Varela, F.J. Autopoiesis and cognition: The realization of the living. D. Reidel Publishing Company. 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in systems: A primer; Chelsea Green Publishing, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, M. Complexity: A guided tour; Oxford University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Tushman, M.L. Organizational ambidexterity: Past, present, and future. Academy of Management Perspectives 2013, 27, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahrovani, Y. Platform drifting: When work digitalization hijacks its spirit. Journal of Strategic Information Systems 2020, 29, 101615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, M.; Levin, S.; Fink, T.; Levina, A. Taming complexity. Harvard Business Review 2020, 98, 112–121. [Google Scholar]

- Sambamurthy, V.; Wei, K.K.; Lim, K.; Lee, D. Digital ecodynamics in organizations: Examining the interplay of digital platform implementation, resilience, and innovation capabilities. MIS Quarterly 2021, 45, 337–366. [Google Scholar]

- Schoemaker, P.J.; Heaton, S.; Teece, D. Innovation, dynamic capabilities, and leadership. California Management Review 2018, 61, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senge, P.M. The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Currency. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, W.K.; Lewis, M.W. Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. Academy of Management Review 2011, 36, 381–403. [Google Scholar]

- Snowden, D.J.; Boone, M.E. A leader’s framework for decision making. Harvard Business Review 2007, 85, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Teece, D.J. Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Planning 2018, 51, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.; Swart, J.; Maylor, H.; Antonacopoulou, E. Making it happen: How managerial actions enable project-based ambidexterity. Management Learning 2022, 53, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl-Bien, M.; Arena, M. Leadership for organizational adaptability: A theoretical synthesis and integrative framework. The Leadership Quarterly 2018, 29, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Salt, D. Resilience thinking: Sustaining ecosystems and people in a changing world; Island Press, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E.; Sutcliffe, K.M. Managing the unexpected: Sustained performance in a complex world, 3rd ed.; Wiley, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley, M.J. Leadership and the new science: Discovering order in a chaotic world; Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, T.A.; Gruber, D.A.; Sutcliffe, K.M.; Shepherd, D.A.; Zhao, E.Y. Organizational response to adversity: Fusing crisis management and resilience research streams. Academy of Management Annals 2017, 11, 733–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).