1. Introduction

The development of mesoporous organically modified silicates with customizable pore sizes began in the 1990s and has since evolved into one of the fastest growing areas of nanomaterials research [

1,

2,

3,

4], as functional compounds, characterized by their well-defined structures, find applications across various branches of chemistry and related disciplines [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. One of the most intriguing features of these organic–inorganic hybrid materials is their molecular architecture, consisting of an inorganic Si–O core covalently bonded to organic substituents [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. They are typically synthesized through the hydrolytic condensation of tailored alkoxysilane derivatives, under suitable conditions, resulting inorganic cage-like silicon-oxygen (siloxane) frameworks surrounded by functionalized organic side-chains [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

Moreover, functionalized hydrogels derived from these materials can exhibit desirable surface characteristics, including high interfacial toughness, tunable thickness, fitting topology, transparency, and adjustable hydrophobicity, enabling properties such as anti-fouling, anti-fogging, lubricant, and abrasion resistance [

7,

8,

9,

17]. With recent advancements in surface-modified nanosystems for bioengineering and biomedical applications [

7,

8,

9,

17], silica-based nanomaterials have gained significant attention due to their ease of surface functionalization, bioactivity, biocompatibility, biodegradability, and bioavailability, and as a result have been exploited in a range of therapeutic processes [

14,

18,

19,

20,

21]. For example, covalent hybrid networks based on substituted spherosilicate cores incorporating functionalized methacrylates have shown promise in bone tissue engineering [

14,

21]. Similarly, virus-like mesoporous silica nanoparticles have demonstrated enhanced cellular uptake [

20], while large-pore mesoporous silica nanoparticles have been utilized in immunotherapy, particularly for the co-delivery of protein antigens and toll-like receptor 9 agonists to boost cancer vaccine efficacy [

18,

19].

Silica-based sol–gels are particularly notable for their high porosity, glassy rigidity, large specific surface area, and thermal stability, coupled with the convenience of tunability of pores size and volume [

11,

16,

22,

23,

24,

25]. In addition, the presence of heteroatoms at the organic linkers within their cage-like structures improve their effectiveness as metal nanoparticles’ stabilizers [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. This feature has been exploited in the heterogenization of homogeneous catalytic systems, allowing for the dispersion or encapsulation of metallic nanoparticles within their porous structures [

2][

31]. Such systems not only maintain high surface area and enables customizable pore sizes, but also facilitate an easy product separation, and catalyst reusability [

2][

31]. As a result, these hybrid catalysts are increasingly being implemented in continuous flow chemical processes [

31,

32,

33,

34].

We here report the dispersion and stabilization of platinum (Pt), palladium (Pd), cobalt (Co), and palladium-cobalt (Pd-Co) metal nanoparticles in organically modified silicates using a sol–gel synthesis approach. The resulting hybrid materials were comparatively characterized using FTIR, TEM, SEM, and XPS techniques. These materials are ultimately designed to serve as potential recyclable catalysts for various chemical transformations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

All chemicals and solvents were obtained from major suppliers such as Fisher Scientific or Avantor Science Central, and used as received, without further purification unless otherwise specified.

2.2. FTIR and XPS

FTIR experiments were conducted using a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS20 FTIR Spectrometer, equipped with advanced LightDrive™ optical engine technology, a GA-IR module, and external microscopes suitable for both liquid and solid samples.

XPS measurements were performed using a ScientaOmicron ESCA 2SR X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy system equipped with a flood source charge neutralizer. Powder samples were pressed into small pellets and mounted on the sample stage using double-sided carbon tape. Samples were then loaded into the load-lock chamber and evacuated to a vacuum level below 5 × 10⁻⁷ mBar before being transferred to the analysis chamber. All measurements were conducted using a monochromatic Al Kα X-ray source (1486.6 eV) operating at 450 W, with the pressure in the analysis chamber maintained below 3 × 10⁻⁹ mBar. A wide-range survey scan and high-resolution core-level scans for all elements were acquired and calibrated using the C(1s) peak at 284.8 eV as the reference. Core-level spectra were deconvoluted to determine chemical state information.

2.3. SEM and TEM

SEM imaging and EDS analysis were conducted using an FEI Quanta 3D FEG FIB-SEM dual-beam system equipped with an EDAX Apollo XL EDS detector. Powder samples were mounted on SEM stubs using double-sided carbon tape and coated with a thin layer of platinum to minimize charging effects during imaging and analysis.

For TEM imaging, data were acquired using a JEOL 2011 TEM operated at 200 kV. TEM samples were prepared following a standard protocol: grinding, mixing with ethanol to form a suspension, ultrasonic bathing, vortexing, and applying the suspension to a holey carbon film supported by 300-mesh copper grids.

2.4. General Procedure for the Preparation of Metal Nanoparticles Dispersed and Stabilized in Organically Modified Silicates

The general procedure for the preparation of these materials was adapted from previously reported methods [

26,

35,

36,

37]. It involves vigorous stirring of the selected alkoxysilane, used as the matrix precursor, in approximately 10 mL of 0.05 M HCl until a homogeneous solution is obtained. The appropriate metal salt, dissolved in about 30 mL of an acetonitrile:water mixture (3:2), is then added, and the resulting mixture stirred until fully homogeneous. Subsequently, a solution of 1 M NaOH is added until the pH reaches approximately 8, and the mixture stirred until gelation occurs. The resulting transparent gel is air-dried for 4 to 5 days, after which the xerogel is crushed and ground. The embedded metal nanoparticles are then reduced in situ using a sodium borohydride solution in 50 mL of THF:ethanol (1:1), with a metal-to-NaBH₄ molar ratio of 1:10. The reduced material is washed with two 100 mL portions of distilled water and one 100 mL portion of THF, then air-dried at room temperature for 24 hours, followed by an additional 24 hours at 150 °C in an oven to yield the final material.

The distribution of metal nanoparticles within the material was analyzed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), while surface morphology was examined via scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Qualitative and quantitative chemical microanalysis was performed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), allowing for precise determination of both the metal content and the chemical state of the dispersed nanoparticles. These experiments were conducted at the Shared Instrumentation Facility (SIF) at Louisiana State University (LSU) in Baton Rouge.

Preparation of Pt@MTES

A mixture of methyltriethoxysilane (MTES: 30.0 g, 168.3 mmol) and 10 mL of 0.05 M aqueous HCl was vigorously stirred until the solution became homogeneous. A solution of potassium tetrachloroplatinate(II) (K₂PtCl₄: 2.50 g, 6.02 mmol) in 30 mL of acetonitrile–water (3:2) was then added. The resulting mixture was stirred until complete homogeneity, followed by the addition of 8.4 mL of 1 M NaOH to induce gelation. The resulting light-orange xerogel was air-dried for 4 days, then reduced with a solution of sodium borohydride (NaBH₄: 2.28 g, 60.23 mmol) in 50 mL of THF–ethanol (1:1), then washed and dried as above described.

Preparation of Pd@MTES

A mixture of methyltriethoxysilane (MTES: 27.0 g, 151.4 mmol) and 10 mL of 0.05 M aqueous HCl was vigorously stirred until the solution became homogeneous. A solution of palladium(II) nitrate dihydrate (Pd(NO₃)₂·2H₂O: 3.00 g, 11.3 mmol) in 30 mL of acetonitrile–water (3:2) was then added. The mixture was stirred until a brownish homogeneous solution is obtained. Approximately 22 mL of 1 M NaOH was added until the solution became slightly basic, as indicated by pH paper (pH ~ 8), and the mixture was stirred further until gelation occurred. The resulting homogeneous and transparent gel was allowed to air dry for 4 days. The resulting dark xerogel was reduced with a solution of sodium borohydride (NaBH₄: 4.26 g, 112.6 mmol) in 50 mL of THF–ethanol (1:1), then washed and dried as above described.

Preparation of Co@MTES

A mixture of methyltriethoxysilane (MTES: 35.0 g, 196.3 mmol) and 12 mL of 0.05 M aqueous HCl was vigorously stirred until the solution became homogeneous. A solution of cobalt(II) nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O: 3.00 g, 10.3 mmol) in 30 mL of acetonitrile–water (3:2) was then added. The mixture was stirred until a homogeneous solution is obtained. Approximately 20 mL of 1 M NaOH was added until the solution became slightly basic, as indicated by pH paper (pH ~ 8), and the mixture was stirred further until gelation occurred. The resulting homogeneous and transparent gel was allowed to air dry for 5 days. The resulting xerogel was reduced with a solution of sodium borohydride (NaBH₄: 3.90 g, 103.1 mmol) in 50 mL of THF–ethanol (1:1), then washed and dried as above described.

Preparation of Pd-Co@MTES

A mixture of methyltriethoxysilane (MTES: 33.0 g, 185.1 mmol) and 10 mL of 0.05 M aqueous HCl was vigorously stirred until the solution became homogeneous. A solution of palladium(II) nitrate dihydrate (Pd(NO₃)₂·2H₂O: 2.00 g, 7.51 mmol) and cobalt(II) nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O: 3.00 g, 10.3 mmol) in 30 mL of acetonitrile–water (3:2) was then added. The mixture was stirred until a homogeneous solution is obtained. Approximately 45 mL of 1 M NaOH was added until the solution became slightly basic, as indicated by pH paper (pH ~ 8), and the mixture was stirred further until gelation occurred. The dark homogeneous and transparent gel was allowed to air dry for 5 days. The resulting xerogel was reduced with a solution of sodium borohydride (NaBH₄: 6.66 g, 178.1 mmol) in 50 mL of THF–ethanol (1:1), then washed and dried as above described.

3. Results and Discussion

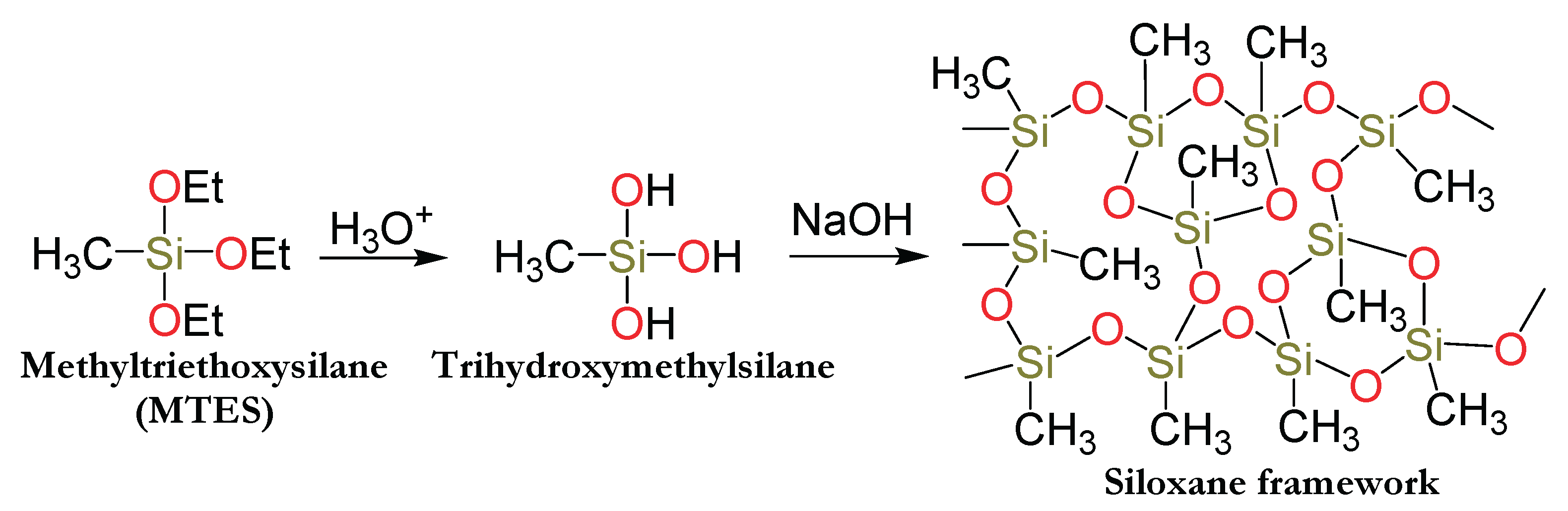

Mesoporous organically modified silicates are organic–inorganic hybrid materials typically synthesized through the hydrolytic condensation of customized alkoxysilane derivatives, as illustrated in

Scheme 1. The choice of silane precursor is crucial, as it significantly influences the architecture of the resulting inorganic siloxane framework [

12,

24,

25,

38]. Owing to their high porosity, large specific surface area, excellent thermal stability, and the presence of heteroatoms linkers within their cage-like structure, these materials are particularly well-suited for the dispersion and stabilization of metal nanoparticles [

12,

24,

25,

38]. Consequently, they were selected as the matrix of choice for this study.

Furthermore, in a previous investigation, we evaluated a series of silane precursors including triethoxysilane (HTEOS), methyltriethoxysilane (MTES), ethyltriethoxysilane (ETES), triethoxyvinylsilane (TEVS), and propyltriethoxysilane (PTES), for their ability to stabilize platinum(0) nanoparticles [

26]. Among them, HTEOS, MTES, and ETES, which contain hydrogen, methyl, and ethyl substituents respectively, promoted a more uniform distribution of nanoparticles. In contrast, PTES and TEVS tended to form rubber-like films during the polymerization process, resulting in poor nanoparticle dispersion [

26]. Based on these observations, methyltriethoxysilane (MTES) was selected as the siloxane precursor for the current study.

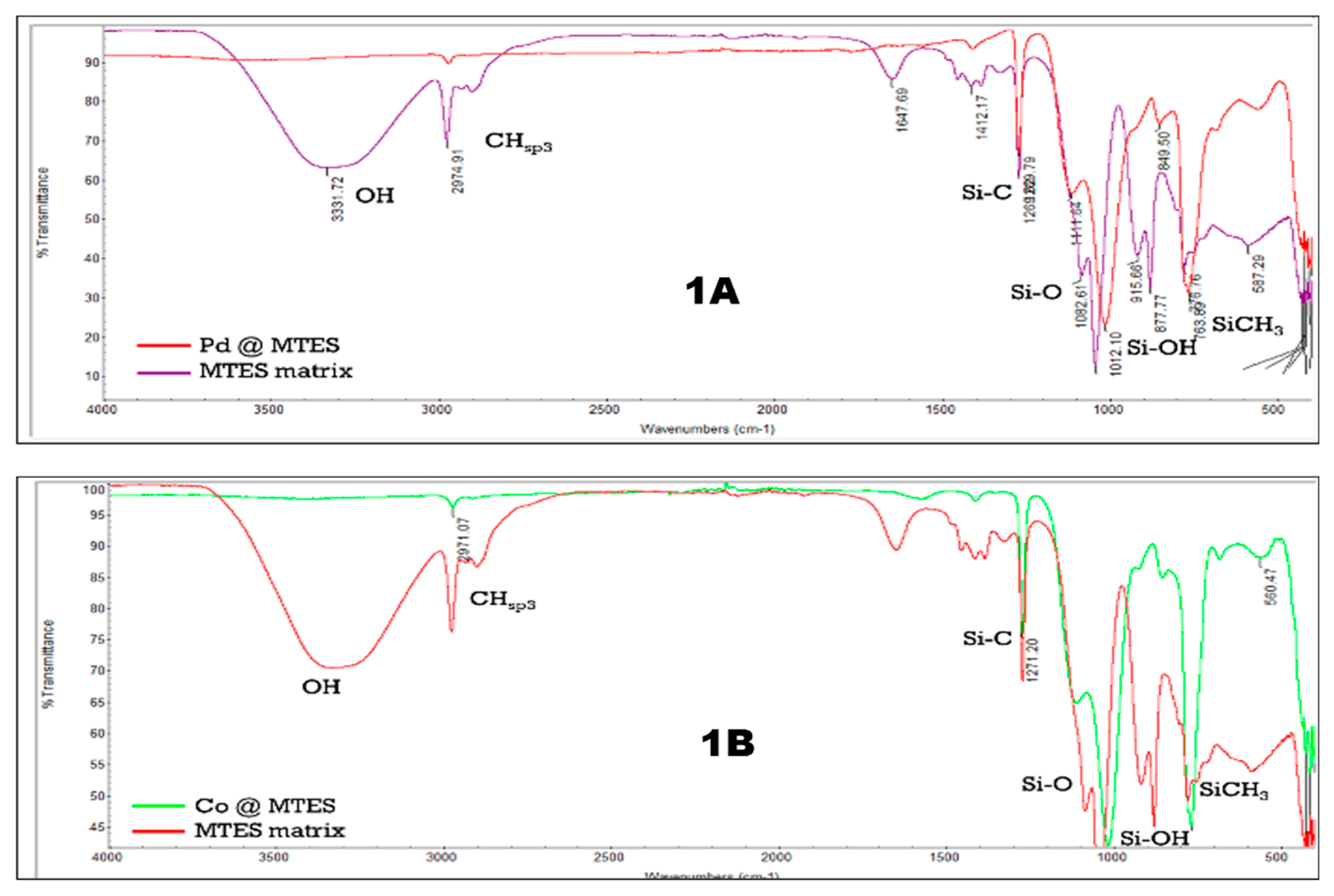

The dispersion and stabilization of each of the metal nanoparticles described in this study into the mesoporous organically modified silicate matrix was monitored using FTIR spectroscopy.

Figure 1a displays the FTIR spectra of trihydroxymethylsilane (the hydrolyzed but unpolymerized form of MTES, shown in purple) and the final condensed sol–gel product following the encapsulation of palladium nanoparticles within the three-dimensional siloxane network (Pd@MTES, shown in red). A similar spectral trend was observed for the cobalt-loaded material (Co@MTES), as depicted in

Figure 1b, where the spectrum of trihydroxymethylsilane is shown in red and that of the condensed sol–gel network in green. It is worth noting that the FTIR data (not shown) for other materials discussed in this study, namely Pt@MTES and Pd-Co@MTES, exhibited spectral patterns closely resembling those presented in

Figure 1.

The FT-IR spectra of both trihydroxymethylsilane and the organically modified silicate material in both spectra align closely with previously reported data on the characterization of organically modified silicate sol-gels [

12,

14,

35,

38,

39]. In the spectra of trihydroxymethylsilane, a broad absorption band at ~3331 cm⁻¹, attributed to ν(OH), along with a bending vibration at ~915 cm⁻¹ corresponding to ν(Si–OH), confirms the presence of free hydroxyl groups bonded to silicon. Additional bands at ~1082 cm⁻¹ and ~1042 cm⁻¹, assigned to ν(O–Si–O) bending vibrations, further support the formation of siloxane linkages. Characteristic absorptions for the methyl groups bonded to silicon are also present: ν(CH_sp3) at ~2975 cm⁻¹, ν(Si–C) at ~1269 cm⁻¹, and a bending vibration at ~776 cm⁻¹ attributed to ν[(Si)CH₃]. These signals collectively confirm the hydrolysis of triethoxymethylsilane to trihydroxymethylsilane.

Following the incorporation of metal nanoparticles and subsequent polymerization of trihydroxymethylsilane into a gel, a comparative analysis of the IR spectrum of the hydrolyzed but unpolymerized trihydroxymethylsilane and that of both final materials (Pd@MTES and Co@MTES) is provided in

Table 1. Notably, the signals associated with free hydroxyl groups, namely the broad ν(OH) at ~3331 cm⁻¹ and the ν(Si–OH) bending at ~915 cm⁻¹, are absent in the post-polymerization material. This absence indicates successful condensation and gel formation. Meanwhile, signals corresponding to ν(CH_sp3), ν(Si–C), ν(O–Si–O), and ν[(Si)CH₃] remain present in both spectra, confirming the formation of the siloxane network. These findings collectively demonstrate that trihydroxymethylsilane underwent complete polymerization and that the metal nanoparticles are effectively dispersed and stabilized within the resulting homogeneous, three-dimensional silicate matrix [

12,

14].

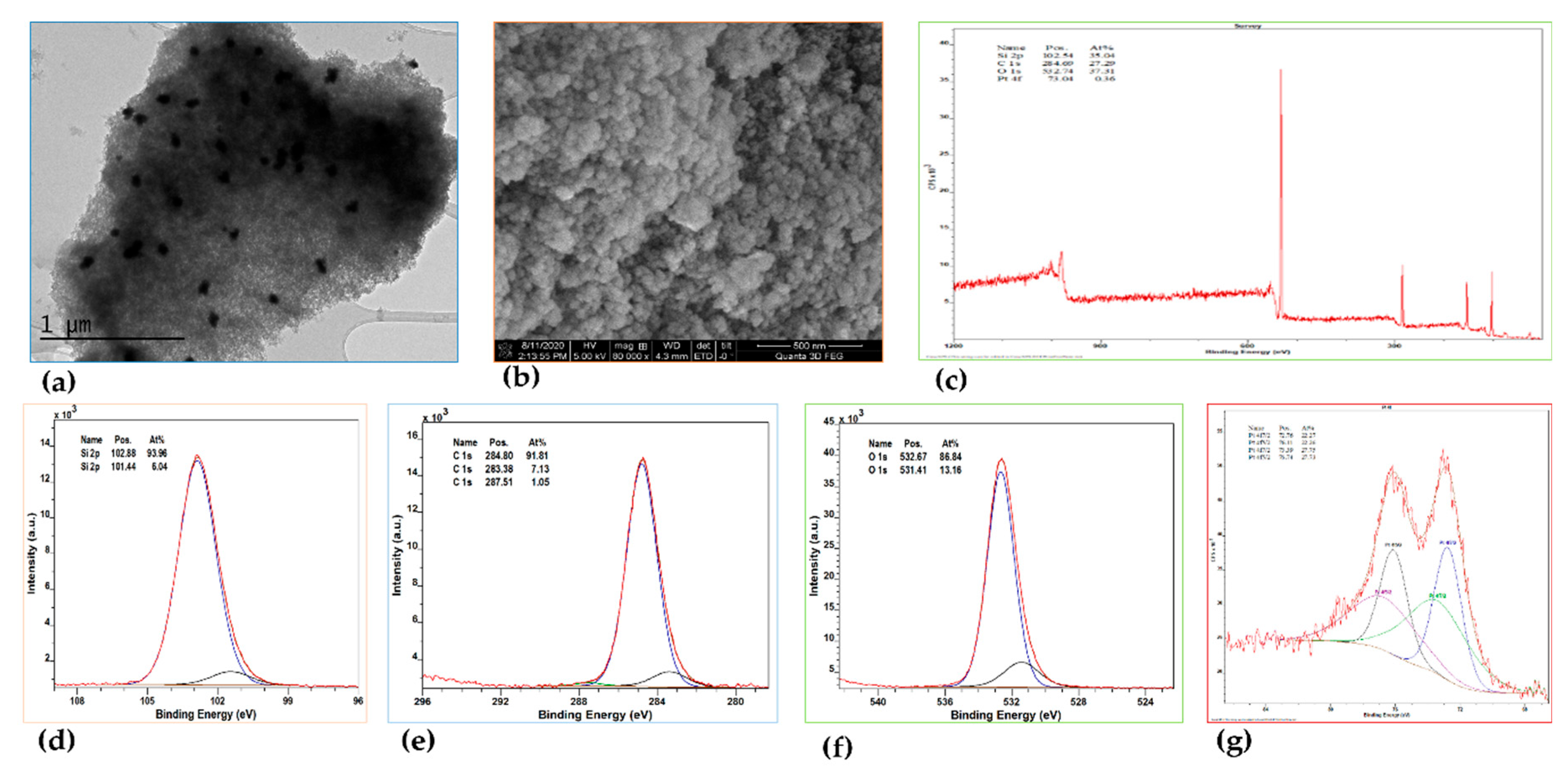

3.1. Characterization of Pt@MTES

The distribution of metal nanoparticles within Pt@MTES was examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), while scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to assess surface morphology. TEM images revealed that the nanoparticles were uniformly dispersed throughout the siloxane matrix, with particle diameters ranging approximately from 5 to 7 nm (

Figure 2a). SEM analysis showed the surface of Pt@MTES to be relatively rough, granular, and uneven, yet overall uniform in texture (

Figure 2b).

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was conducted to further analyze the surface composition. The survey spectrum revealed peaks corresponding to silicon (Si 2p), carbon (C 1s), oxygen (O 1s), and platinum (Pt 4f), with binding energies located at 102.54, 284.69, 532.74, and 73.04 eV, respectively (

Figure 2c). Deconvolution of the Si(2p) signal revealed superimposed peaks at 102.88 (Si 2p

3/2) and 101.44 (Si 2p

1/2) eV (

Figure 2d), characteristic of silicones and siloxanes [

40,

41]. The C(1s) spectrum exhibited three fitted peaks at 283.38 eV and 284.80 eV corresponding to C–Si, and at 287.51 eV attricutable to the C–O bond, respectively (

Figure 2e) [

42,

43,

44]. While the C–Si signal is characteristic of the siloxane framework [

22], the marginal C–O peak (1.05 At%) is attributed to residual ethoxy groups from the methyltriethoxysilane precursor used in the sol–gel synthesis. Additionally, the analysis of the O(1s) region revealed deconvoluted peaks at 531.41 and 532.67 eV (

Figure 2f), supporting the predominance of organically modified silicate species on the material’s surface. The same XPS analysis displayed in Pt(4f) region, two primary peaks at 72.76 eV (Pt 4f₇/₂) and 76.11 eV (Pt 4f₅/₂), indicating the presence of metallic platinum, Pt(0) (

Figure 2g) [

45]. Additional peaks at 73.39 and 76.74 eV were detected, suggesting a significant presence of Pt(II) species [

45]. Quantitative analysis based on peak areas estimated Pt(0) at approximately 44.53 At% and Pt(II) at about 55.48 At%, attesting for only a partial reduction of Pt(II). The total platinum loading was estimated at 0.36 At% of the material.

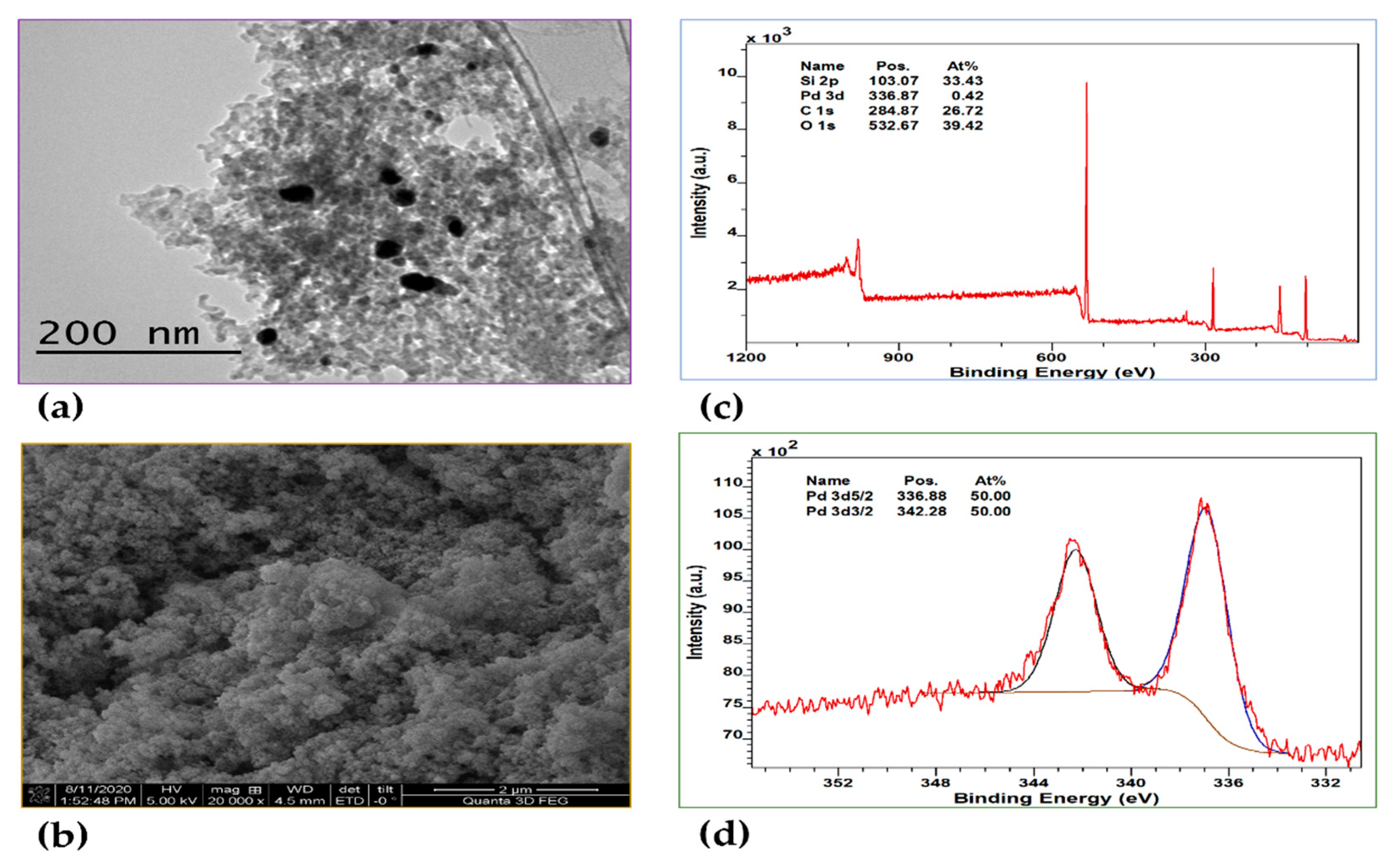

3.2. Characterization of Pd@MTES

As with Pt@MTES, the distribution of metal nanoparticles within Pd@MTES was examined by TEM, and the surface morphology analyzed using SEM. Both materials showed strong similarities, with the Pd nanoparticles uniformly dispersed and approximately 3 to 5 nm in diameter (

Figure 3a). The surface of Pd@MTES also exhibited a rough, granular, uneven and consistent texture, mirroring the morphology observed in Pt@MTES (

Figure 3b).

XPS analysis further confirmed the material's composition, with the survey spectrum (

Figure 3c) displaying characteristic peaks for silicon (Si 2p), carbon (C 1s), oxygen (O 1s), and palladium (Pd 3d), with binding energies at approximately 103.07, 284.87, 532.67, and 336.87 eV, respectively. The deconvolution of the Si(2p), C(1s), and O(1s) peaks revealed trends consistent with those seen in Pt@MTES. The high-resolution XPS spectrum of Pd(3d) (

Figure 3d) showed only two main peaks at 336.88 and 342.28 eV, corresponding to Pd(3d₅/₂) and Pd(3d₃/₂), respectively, indicative of metallic Pd(0) [

46,

47]. Unlike in Pt@MTES, no additional signals were observed in the XPS spectrum of Pd(3d), indicating the absence of other palladium species, with the total palladium content estimated to be 0.42 At% of the material. This suggests that, in contrast to Pt@MTES, where less than half of the Pt(II) species were reduced to Pt(0), all Pd(II) species in Pd@MTES were successfully reduced.

Generally, a higher or more positive redox potential indicates a greater tendency for a metal ion to accept electrons and be reduced. Based on this principle, one would expect platinum(II) (Pt²⁺/Pt(s), E° = 1.18 V) to be more readily reduced than palladium(II) (Pd²⁺/Pd(s), E° = 0.915 V). It is unclear why this does not appear to be the case in the present context. It is possible that palladium, as a result of the smaller particle sizes, is occupying a higher effective surface area resulting in a more efficient reduction of Pd(II) to metallic palladium, despite the thermodynamic expectations based on redox potentials.

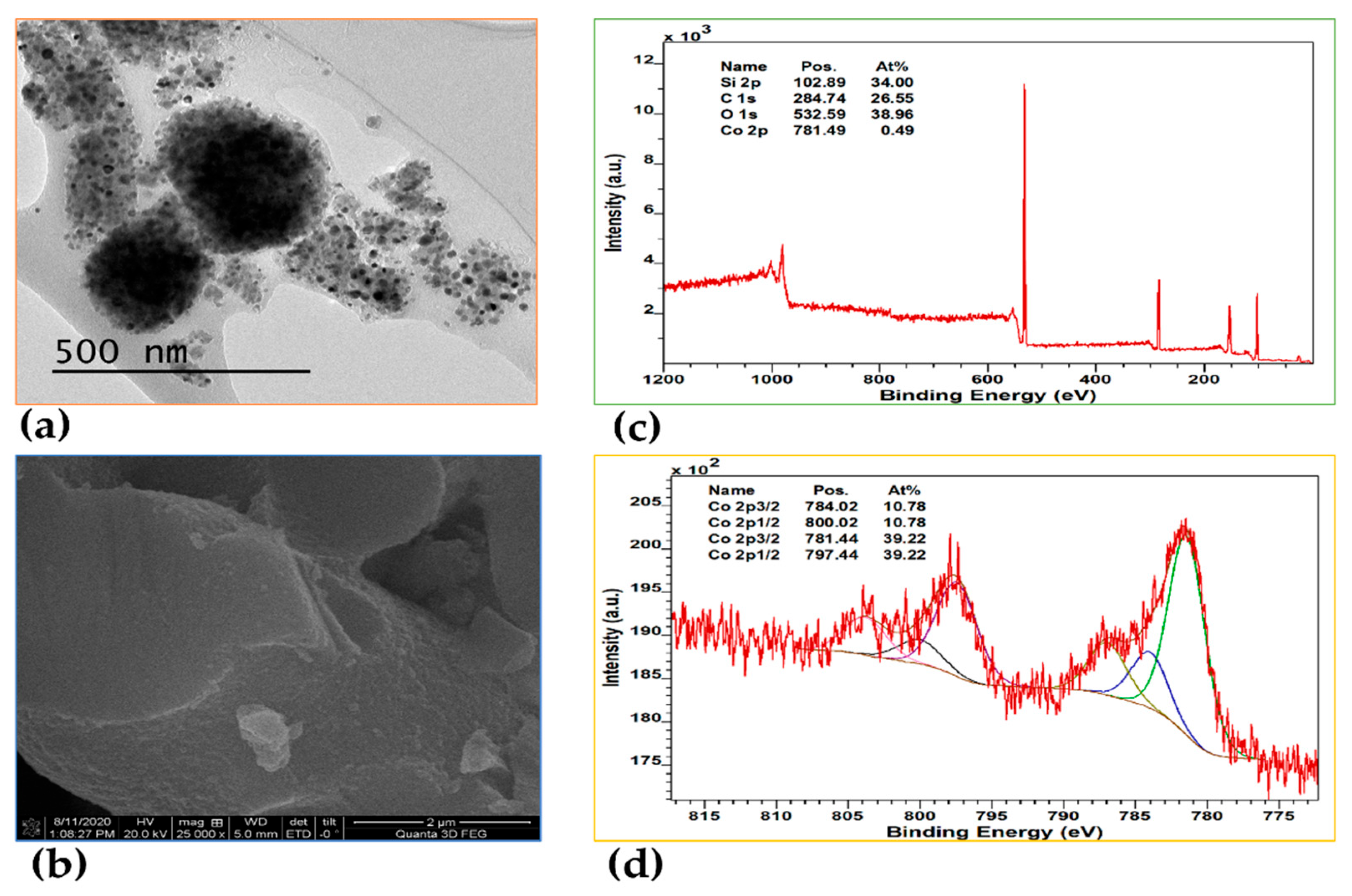

3.3. Characterization of Co@MTES

The nanoparticles in Co@MTES also appeared to be uniformly dispersed, with particle sizes ranging from approximately 2 to 4 nm in diameter (

Figure 4a). In contrast to Pt@MTES and Pd@MTES, which exhibited relatively rough and uneven surfaces, the surface morphology of Co@MTES appeared smooth, dense, and finely textured, with a polished appearance as illustrated by the SEM image in

Figure 4b.

XPS analysis further confirmed the composition of the material, with the survey spectrum (

Figure 4c) showing characteristic peaks for silicon (Si 2p), carbon (C 1s), and oxygen (O 1s), similar to those observed in Pt@MTES and Pd@MTES, along with an additional signal corresponding to cobalt (Co 2p), with binding energies at approximately 102.89, 284.74, 532.59, and 781.49 eV, respectively. Deconvolution of the Co(2p) spectrum (

Figure 4d) revealed two peaks at 784.02 and 800.02 eV, corresponding to Co(2p₃/₂) and Co(2p₁/₂), indicative of metallic cobalt (Co⁰) [

48,

49,

50]. Two additional peaks at 781.44 and 797.44 eV, also attributed to Co(2p₃/₂) and Co(2p₁/₂), suggest the presence of another cobalt species, likely cobalt(II) [

48,

49,

50,

51]. The XPS data also indicated that the material contains approximately 21.56 At% of metallic cobalt and 78.44 At% of Co(II), with the total cobalt content estimated at 0.49 At% of the material. These observations from the XPS data suggest that only a limited fraction of Co(II) species in Co@MTES was successfully reduced to metallic cobalt. In this case, the negative redox potential of cobalt(II) (Co²⁺/Co(s), E° = –0.277 V) may be responsible for the limited reduction, as the nanoparticles appear to be well distributed throughout the material.

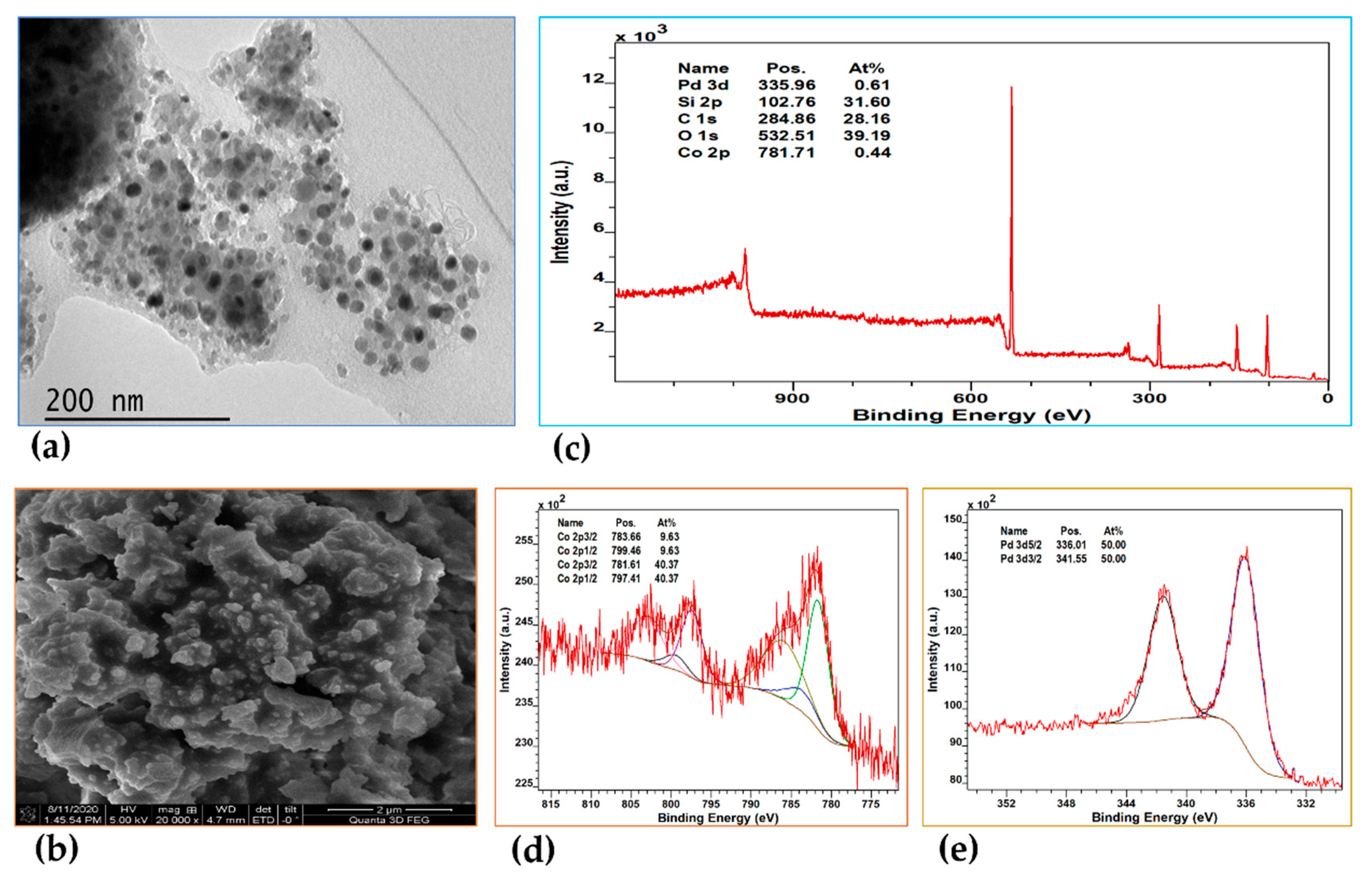

3.4. Characterization of Pd-Co@MTES

Similar to the other materials above described, both palladium and cobalt nanoparticles in this sample appeared uniformly dispersed, with particle sizes ranging from approximately 2 to 5 nm in diameter (

Figure 5a). Notably, the two types of nanoparticles were indistinguishable in appearance under TEM imaging. The surface morphology of this material is also markedly different from that of Co@MTES and Pd@MTES. While Co@MTES exhibited a smooth, dense, finely textured, and polished surface, and Pd@MTES showed a relatively rough and uneven topography, the surface of the current material is distinctively more irregular and complex. It is primarily characterized by jagged, craggy formations and deep ridges, with crevices cutting through the material (

Figure 5b). The texture appears as a heterogeneous blend of hardened crusts and semi-glossy flows, evocative of thick caramel that has unevenly cooled, with the edges smooth in places as if softened and warped by intense heat (

Figure 5b). Interestingly, this unique morphology arises despite the standard sol-gel synthesis procedure being carried out at room temperature, with drying performed only at 150 °C for 24 hours. It is also noteworthy that such surface behavior was not observed in either of the other materials prepared using the same method.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis further revealed that the material is primarily composed of silicon, carbon, and oxygen, with the survey spectrum (

Figure 5c) showing characteristic peaks at binding energies of 102.76 eV (Si 2p), 284.86 eV (C 1s), and 532.51 eV (O 1s). Signals corresponding to cobalt (Co 2p) and palladium (Pd 3d) were also present at 781.71 eV and 335.96 eV, respectively.

Deconvolution of the Co(2p) spectrum (

Figure 5d) yielded features consistent with those observed for Co@MTES, with the Co(2p₃/₂) and Co(2p₁/₂) peaks for metallic cobalt (Co⁰) at 783.66 eV and 799.46 eV, respectively [

48,

49,

50,

51]. Additionally, peaks at 781.61 eV (Co 2p₃/₂) and 797.41 eV (Co 2p₁/₂) indicated the presence of cobalt(II) species [

48,

49,

50], and as with Co@MTES, the composition was found to be approximately 19.26 At% metallic cobalt and 80.74 At% cobalt(II), with a total cobalt content of 0.44 At%.

The high-resolution XPS spectrum for Pd(3d) (

Figure 5d) showed the Pd(3d₅/₂) and Pd(3d₃/₂) signals for metallic palladium (Pd⁰) at 336.01 eV and 341.55 eV, respectively [

46,

47]. In contrast to cobalt, and consistent with observations in Pd@MTES, no additional palladium species were detected, suggesting the exclusive presence of metallic Pd, with a total palladium content of 0.61 at%. Since the particle sizes are very similar, with cobalt nanoparticles even statistically smaller than those of palladium, the more negative redox potential of cobalt (Co²⁺/Co(s), E° = –0.277 V) compared to that of palladium (Pd²⁺/Pd(s), E° = 0.915 V) is likely the determining factor in the observed difference in reduction behavior.

4. Conclusions

Platinum, palladium, cobalt, and palladium–cobalt metal nanoparticles were individually dispersed and stabilized within organically modified silicates, synthesized via sol–gel polymerization of methyltriethoxysilane (MTES) as the siloxane matrix precursor. In situ reduction of the corresponding metal ions yielded finely dispersed nanoparticles with distinct surface morphologies and compositions depending on the metal incorporated. The resulting materials were characterized by FTIR, TEM, SEM, and XPS. Among the nanoparticles, it appeared that only palladium was fully reduced to metallic Pd(0) during the in situ process. In contrast, platinum(II), despite its higher redox potential, was only partially reduced, while cobalt showed minimal reduction, even when co-dispersed within the same matrix with palladium, which appears fully reduced at the end. The limited reduction of cobalt could be attributed to its negative redox potential. As Pt(II) was expected to be more readily reduced than Pd(II), it was speculated that palladium’s smaller nanoparticle size and higher effective surface area facilitated a more efficient reduction. Therefore, the contrasting reduction behaviors of palladium and platinum might be driven more by nanoparticle distribution and surface accessibility than by redox potential alone.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, J.F.; formal analysis, J.F.; investigation, J.F. and C.L.B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F. and C.L.B.; writing—review and editing, J.F.; project administration, J.F.; funding acquisition, J.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

J.F. acknowledges the financial support from NSF CHE-1954734 and from the Edward G. Schlieder Educational Foundation.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supporting information. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the Louisiana State University Shared Instrumentation Facility (SIF) for providing access to TEM, SEM, and XPS instrumentation and for assisting with data collection on a fee-for-service basis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper. Furthermore, the funding agencies listed above had no involvement in the study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation. They also played no role in the writing of the manuscript or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EDAX |

energy dispersive x-ray analysis |

| EDS |

energy-dispersive x-ray spectroscopy |

| ETES |

ethyltriethoxysilane |

| FIB-SEM |

focused ion beam scanning electron spectroscopy |

| HTEOS |

triethoxysilane |

| MTES |

methyltriethoxysilane |

| ORMOSILs |

organically modified silicates |

| PTES |

propyltriethoxysilane |

| SEM |

scanning electron microscopy |

| TEM |

transmission electron microscopy |

| TEVS |

triethoxyvinylsilane |

| XPS |

x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy |

References

- Hay, J.N.; Raval, H.M. Synthesis of organic-inorganic hybrids via the nonhydrolytic sol-gel process. Chem Mater. 2001, 13, 3396–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, J.D.; Bescher, E.P. Structures, properties and potential applications of Ormosils. J Sol-Gel Sci Technol. 1998, 13, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinson, MM. Recent trends in analytical applications of organically modified silicate materials. Trends Anal Chem. 2002, 21, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collinson, M.M. Analytical applications of organically modified silicates. Mikrochim Acta. 1998, 129, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Q.; Deng, W.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y. Recent advances in heterogeneous selective oxidation catalysis for sustainable chemistry. Chem Soc Rev. 2014, 43, 3480–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, J.; Tsubaki, N. Clever nanomaterials fabrication techniques encounter sustainable C1 catalysis. Acc Chem Res. 2023, 56, 2341–2353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, F.; Cao, Z.; Ji, X.; Chu, B.; Su, Y.; He, Y. Silicon nanostructures for cancer diagnosis and therapy. Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 2109–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, F.; Su, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Fan, C.; Lee, S.-T.; He, Y. Silicon nanomaterials platform for bioimaging, biosensing, and cancer therapy. Acc Chem Res. 2014, 47, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Wang, G.; Chang, N. ; Wang Q, editors. Applications of porous silicon materials in drug delivery in Porous Silicon: From Formation to Application: Biomedical and Sensor Applications. First Edition, Volume 2. 2016: CRC Press. pp 1–17.

- Friend, C.M.; Xu, B. Heterogeneous catalysis: a central science for a sustainable future. Acc Chem Res. 2017, 50, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassindale, A.R.; Liu, Z.; MacKinnon, I.A.; Taylor, P.G.; Yang, Y.; Light, M.E.; Horton, P.N.; Hursthouse, M.B. A higher yielding route for T8 silsesquioxane cages and X-ray crystal structures of some novel spherosilicates. Dalton Trans. 2003(14), 2945–2949. [CrossRef]

- Janeta, M.; John, L.; Ejfler, J.; Szafert, S. Novel organic-inorganic hybrids based on T8 and T10 silsesquioxanes: synthesis, cage-rearrangement and properties. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 72340–72351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeta, M.; John, L.; Ejfler, J.; Szafert, S. High-yield synthesis of amido-functionalized polyoctahedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes by using acyl chlorides. Chem - Eur J. 2014, 20, 15966–15974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, L.; Janeta, M.; Szafert, S. Synthesis of cubic spherosilicates for self-assembled organic-inorganic biohybrids based on functionalized methacrylates. New J Chem. 2018, 42, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanprasit, S.; Tungkijanansin, N.; Prompawilai, A.; Eangpayung, S.; Ervithayasuporn, V. Synthesis and isolation of non-chromophore cage-rearranged silsesquioxanes from base-catalyzed reactions. Dalton Trans. 2016, 45, 16117–16120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Liu, L.; Zhang, W.; Yang, R. Synthesis of epoxy and phenyl groups-containing polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane of large Si16O24 cage and its flame retardant and mechanical performances on epoxy resins. J Appl Polym Sci. 2023, 140, e54378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.-Y.; Zhang, A.-Q.; Zhang, X.-Z. Recent advances in targeted tumor chemotherapy based on smart nanomedicines. Small. 2018, 14, e1802417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L. Tailored silica nanomaterials for immunotherapy. ACS Cent Sci. 2018, 4, 527–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, B.G.; Jeong, J.H.; Kim, J. Extra-large pore mesoporous silica nanoparticles enabling co-delivery of high amounts of protein antigen and toll-like receptor 9 agonist for enhanced cancer vaccine efficacy. ACS Cent Sci. 2018, 4, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, P.; Tang, X.; Elzatahry, A.A.; Wang, S.; Al-Dahyan, D.; Zhao, M.; Yao, C.; Hung, C.-T.; Zhu, X.; Zhao, T.; Li, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, D. Facile synthesis of uniform virus-like mesoporous silica nanoparticles for enhanced cellular internalization. ACS Cent Sci. 2017, 3, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, L.; Ejfler, J. A brief review on selected applications of hybrid materials based on functionalized cage-like silsesquioxanes. Polymers. 2023, 15, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, M.; Herrmann, N.; Ramsahye, N.; Totee, C.; Carcel, C.; Unno, M.; Bartlett, J.R.; Chi Man, M.W. Large polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane cages: the isolation of functionalized POSS with an unprecedented Si18O27 core. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2021, 60, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckstorff, F.; Zhu, Y.; Maurer, R.; Mueller, T.E.; Scholz, S.; Lercher, J.A. Materials with tunable low-k dielectric constant derived from functionalized octahedral silsesquioxanes and spherosilicates. Polymer. 2011, 52, 2492–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feher, F.J.; Terroba, R.; Jin, R.-Z.; Wyndham, K.D.; Lucke, S.; Brutchey, R. Silsesquioxanes and spherosilicates as precursors to hybrid inorganic/organic materials. Polym Mater Sci Eng. 2000, 82, 301–302. [Google Scholar]

- Feher, F.J.; Soulivong, D.; Eklund, A.G.; Wyndham, K.D. Cross-metathesis of alkenes with vinyl-substituted silsesquioxanes and spherosilicates: a new method for synthesizing highly-functionalized Si/O frameworks. Chem Commun. 1997, (13), 1185–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duke, B.J.; Akeroyd, E.N.; Bhatt, S.V.; Onyeagusi, C.I.; Bhatt, S.V.; Adolph, B.R.; Fotie, J. Nano-dispersed platinum(0) in organically modified silicate matrices as sustainable catalysts for a regioselective hydrosilylation of alkenes and alkynes. New J Chem. 2018, 42, 11782–11795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzelak, M.; Marciniec, B. Synthesis of bifunctional silsesquioxanes and spherosilicates with organogermyl functionalities. Chem - Asian J. 2020; 15, 2437–2441. [Google Scholar]

- Cybulski, A.; Moulijn, J.A. Monoliths in heterogeneous catalysis. Catal Rev - Sci Eng. 1994, 36, 179–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boger, T.; Heibel, A.K.; Sorensen, C.M. Monolithic catalysts for the chemical industry. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2004, 43, 4602–4611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Guo, Y.; Gao, P.-X. Nano-array based monolithic catalysts: concept, rational materials design and tunable catalytic performance. Catal Today. 2015, 258, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholder, P.; Nischang, I. Miniaturized catalysis: monolithic, highly porous, large surface area capillary flow reactors constructed in situ from polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes (POSS). Catal Sci Technol. 2015, 5, 3917–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marra, L.; Fusillo, V.; Wiles, C.; Zizzari, A.; Watts, P.; Rinaldi, R.; Valentina, A. Sol-gel catalysts as an efficient tool for the Kumada-Corriu reaction in continuous flow. Sci Adv Mater. 2013, 5, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moein, A.; Kebritchi, A. New insights into the structure, properties, and applications of polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane. Silicon. 2023, 15, 5845–5875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, R.; Katz, J.L. Toward the selection of sustainable catalysts for Suzuki-Miyaura coupling: a gate-to-gate analysis. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2018, 6, 14880–14887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devarajan, S.; Bera, P.; Sampath, S. Bimetallic nanoparticles: a single step synthesis, stabilization, and characterization of Au-Ag, Au-Pd, and Au-Pt in sol-gel derived silicates. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 290, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciriminna, R.; Pandarus, V.; Gingras, G.; Beland, F.; Pagliaro, M. Closing the organosilicon synthetic cycle: efficient heterogeneous hydrosilylation of alkenes over SiliaCat Pt(0). ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2013, 1, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matherne, C.M.; Wroblewski, J.E.; Drago, H.S.; Marchan, G.T.; Young, A.R.; Kingsley, N.; Plaisance, C.P.; Fotie, J. Palladium nano-dispersed and stabilized in organically modified silicate as a heterogeneous catalyst for the conversion of aldehydes into O-silyl ether derivatives under neat conditions. Synthesis. 2024, 56, 2031–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharathi, S.; Fishelson, N.; Lev, O. Direct synthesis and characterization of gold and other noble metal nanodispersions in sol-gel-derived organically modified silicates. Langmuir. 1999, 15, 1929–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Souza, L.; Sampath, S. Preparation and characterization of silane-stabilized, highly uniform, nanobimetallic Pt-Pd particles in solid and liquid matrixes. Langmuir. 2000, 16, 8510–8517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Hare, L.-A.; Parbhoo, B.; Leadley, S.R. Development of a methodology for XPS curve-fitting of the Si 2p core level of siloxane materials. Surf Interface Anal. 2004, 36, 1427–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, H.; Takemura, S.; Takakuwa, N.; Ninomiya, K.; Watanabe, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Nanba, N.; Hiramatsu, T. X-ray photoemission spectroscopy characterization of electrochemical growth of conducting polymer on oxidized Si surface. J Vac Sci Technol, A. 2006, 24, 1505–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashouti, M.Y.; Paska, Y.; Puniredd, S.R.; Stelzner, T.; Christiansen, S.; Haick, H. Silicon nanowires terminated with methyl functionalities exhibit stronger Si-C bonds than equivalent 2D surfaces. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2009, 11, 3845–3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puniredd, S.R.; Assad, O.; Haick, H. Highly stable organic modification of Si(111) surfaces: towards reacting Si with further functionalities while preserving the desirable chemical properties of full Si-C atop site terminations. J Am Chem Soc. 2008, 130, 9184–9185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puniredd, S.R.; Assad, O.; Haick, H. Highly stable organic monolayers for reacting silicon with further functionalities: the effect of the C-C bond nearest the silicon surface. J Am Chem Soc. 2008, 130, 13727–13734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dablemont, C.; Lang, P.; Mangeney, C.; Piquemal, J.-Y.; Petkov, V.; Herbst, F.; Viau, G. FTIR and XPS study of Pt nanoparticle functionalization and interaction with alumina. Langmuir. 2008, 24, 5832–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-L.; Feng, J.-X.; Wang, A.-J.; Wei, J.; Feng, J.-J. Simple synthesis of bimetallic alloyed Pd-Au nanochain networks supported on reduced graphene oxide for enhanced oxygen reduction reaction. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 52640–52646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, A.; Chen, L.; Yu, Y. N-Formylation of amines with CO2 and H2 using Pd-Au bimetallic catalysts supported on polyaniline-functionalized carbon nanotubes. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2017, 5, 2516–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.H.; Eren, B.; Bluhm, H.; Salmeron, M.B. Ambient-pressure X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy study of cobalt foil model catalyst under CO, H2, and their mixtures. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 1150–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castner, D.G.; Watson, P.R. X-ray absorption spectroscopy and x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy studies of cobalt catalysts. 3. Sulfidation properties in hydrogen sulfide/hydrogen. J Phys Chem. 1991, 95, 6617–6623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zeng, Y.; Ma, X.; Wang, H.; Gao, L.; Zhong, H.; Meng, Q. Cobalt nanoparticles embedded into n-doped carbon from metal organic frameworks as highly active electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. Polymers 2019, 11, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronda-Lloret, M.; Wang, Y.; Oulego, P.; Rothenberg, G.; Tu, X.; Shiju, N.R. CO2 hydrogenation at atmospheric pressure and low temperature using plasma-enhanced catalysis over supported cobalt oxide catalysts. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2020, 8, 17397–17407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).