1. Introduction

As shown in the International Roadmap for Devices and Systems (IRDS) edited by the IEEE Computer Society or in works such as [

1,

2,

3], in System on Chip (SoC) or Network on Chip (NoC), the memory part has a growing share, currently covering 75-85% of the integrated area. Therefore, in the production of reliable integrated circuits at competitive costs, efficient testing of the memory part is a very important requirement.

In this paper, the authors address the issue of testing

RAMs with regard to the complex fault model of static unlinked neighborhood NPSFs, as a subclass of coupling faults (CFs) model [

4,

5]. According to the classification of memory faults, as presented for example in [

2,

6,

7,

8], the ‘static faults’ class refers to those faults sensitized by performing at most one memory operation, while the ‘dynamic faults’ class refers to those faults sensitized by two or more operations performed sequentially. According to the same taxonomy presented in [

6] or [

7], for example, CFs are said to be unlinked when they do not influence each other. In this paper, the class of static unlinked CFs is addressed.

The CF model reflects imperfections in the memory cell area that cause two or more cells to influence each other in their operation [

2,

3]. Depending on the number of cells involved in a memory fault, there are several classes of coupling faults, such as: two-cell coupling, three-cell coupling, four-cell coupling, or five-cell coupling. In the two-cell CF model, it is considered that the cells involved in a CF can be anywhere in the memory [

9]. In this way, this model also covers addressing memory faults [

6]. For more complex

-cell CF models,

, it is assumed that the cells involved in a memory fault are physically adjacent [

5,

10,

11]. It is therefore necessary to know the memory structure, or more precisely the correspondence between logical addresses and physical addresses, in the form of row and column addresses. This realistic limitation allows the complexity of these fault models to be more easily managed [

12,

13,

14]. For these complex CF models, testing is usually done with additional integrated architectures, called built-in self-test (BIST) logic [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

Regarding the

-cell CFs, depending on the technology used, the accuracy of the testing, and the costs involved, two classes of fault models have been defined to cover the most common memory errors, namely: (a) the classical model class in which it is considered that a memory fault can be sensitized only by a transition write operation, and (b) an extended class of models in which it is admitted that memory faults can be sensitized by transition write operations, as well as by non-transition writes or read operations – extended CF models (ECF) [

9,

12,

13,

14]. With the increase in density and the decrease in supply voltage, the range of memory defects has diversified, and as a result, for high testing accuracy, ECF models are increasingly used. The authors appreciate, however, that a memory test covering the classical CF model can be adapted relatively easily to cover the corresponding ECF model [

12]. This is also highlighted in this work.

For three-cell or four-cell classical CF models, reference tests are reported in [

10,

11,

21,

22,

23,

24]. For three-cell or four-cell ECF models, near-optimal tests are presented in [

14].

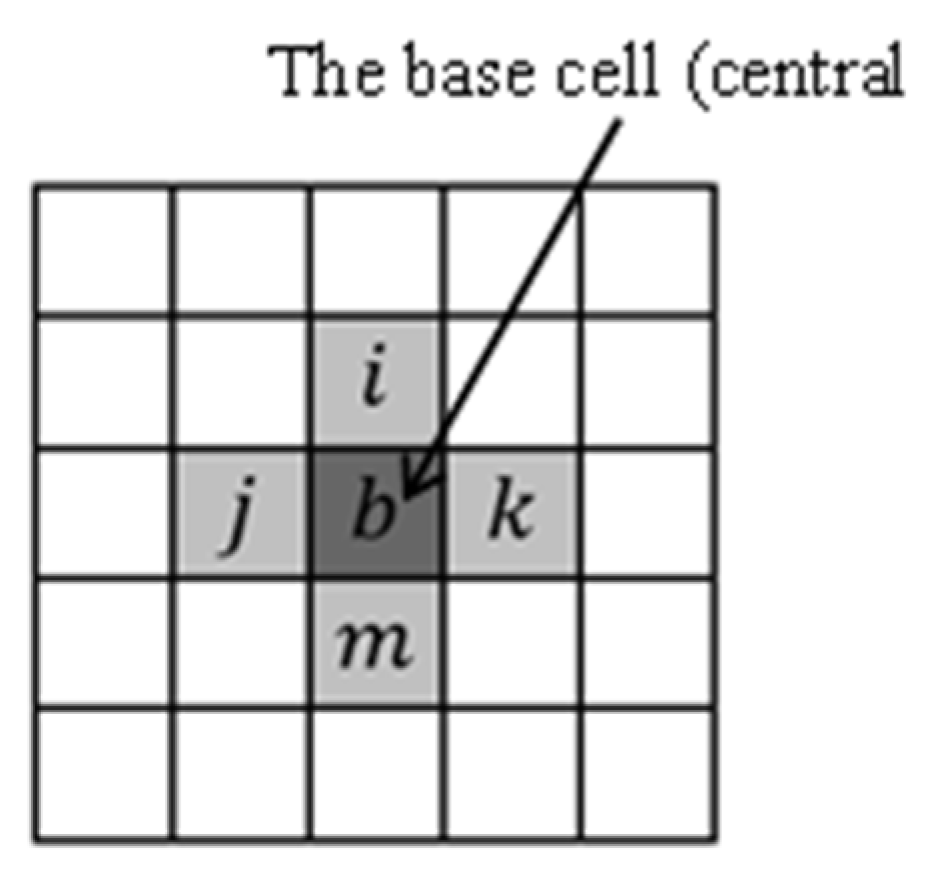

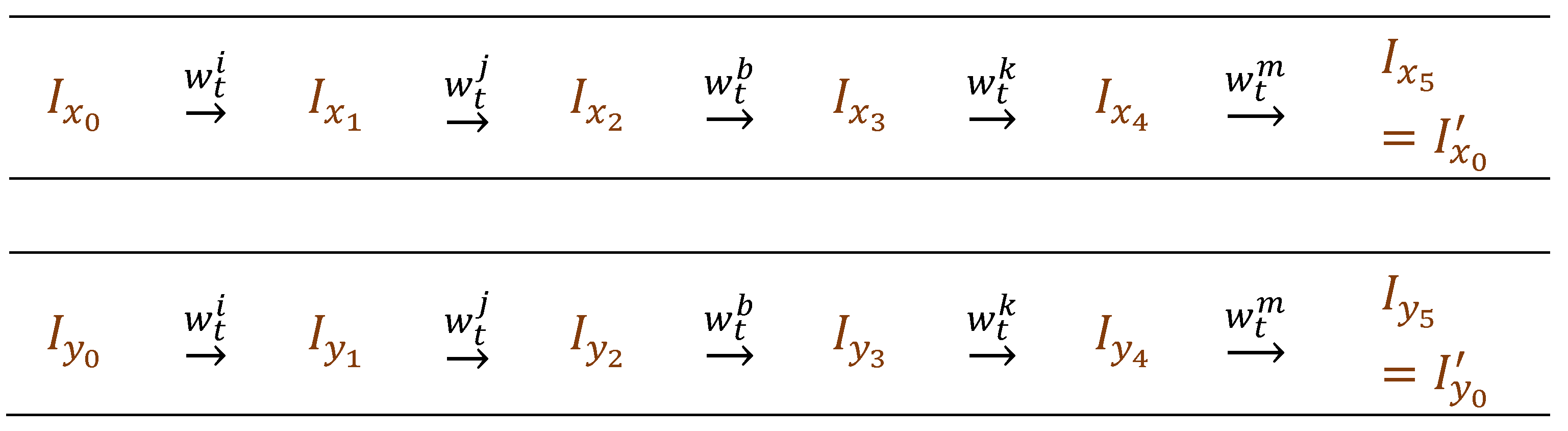

In this paper, we focus exclusively on the NPSF fault model involving five physically adjacent memory cells, arranged in a configuration like the one shown in

Figure 1.

This NPSF fault model, which reflects the influence of neighboring cells on the central memory cell, has been defined since the 1970s [

25]. Specifically, we refer here to the classical NPSF model in which a fault sensitization involves a transition write operation in one cell in the group, the other four cells being in a certain state that favors the occurrence of the memory error. The scientific community has continuously studied the NPSF model because of its importance and complexity. Memory testing for NPSF models is covered extensively in books, like [

2,

3,

4,

26], and in review papers, such as [

16,

17,

19].

For the NPSF model, some memory tests have been proposed since the 1980s, that were quite effective for the memory sizes of that period [

27,

28]. For example, the memory test given by Suk and Reddy [

28] is based on an algorithm for dividing the set of memory cells into two halves, based on row and column addresses, and is

long. A reduction in testing time was possible by applying march-type tests on different memory initialization patterns (data backgrounds). This idea was first proposed by Cockborn [

23]. This technique, called ‘multirun march memory testing’, was then used to identify efficient memory tests for this complex NPSF model [

29,

30,

31,

32]. For example, in [

31], to reduce the length of the test, Buslowska and Yarmolik propose a multirun technique with a random background variation. However, in that case, the NPSF model is not fully covered. A first near-optimal deterministic memory test for the NPSF model was proposed by Cheng, Tsai, and Wu in 2002 [

32]. This memory test called

is

long and uses 16 memory initialization patterns of size 3×3. Ten years later, Huzum and Cascaval [

33] improved this result with another near-optimal memory test (called

), slightly shorter, of length

Compared to the

, the

memory test applies a different testing technique, but also uses 3×3 data background patterns. The

and

tests are the shortest memory tests dedicated to this complex NPSF model. Although near-optimal, these tests are not exactly suitable for BIST implementation due to the complexity of the address-based data generation logic. More on this issue can be found in the works [

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40], but an in-depth analysis is also presented in this paper. For this reason, Cheng, Tsai and Wu also proposed in the same article [

32] another memory test (

) which, although longer (and obviously non-optimal), is easier to implement in BIST-RAM architectures due to its 4×4 memory initialization patterns. A modified version of the

memory test for diagnosis of SRAM is given by Julie, Sidek, and Wan Zuha [

36].

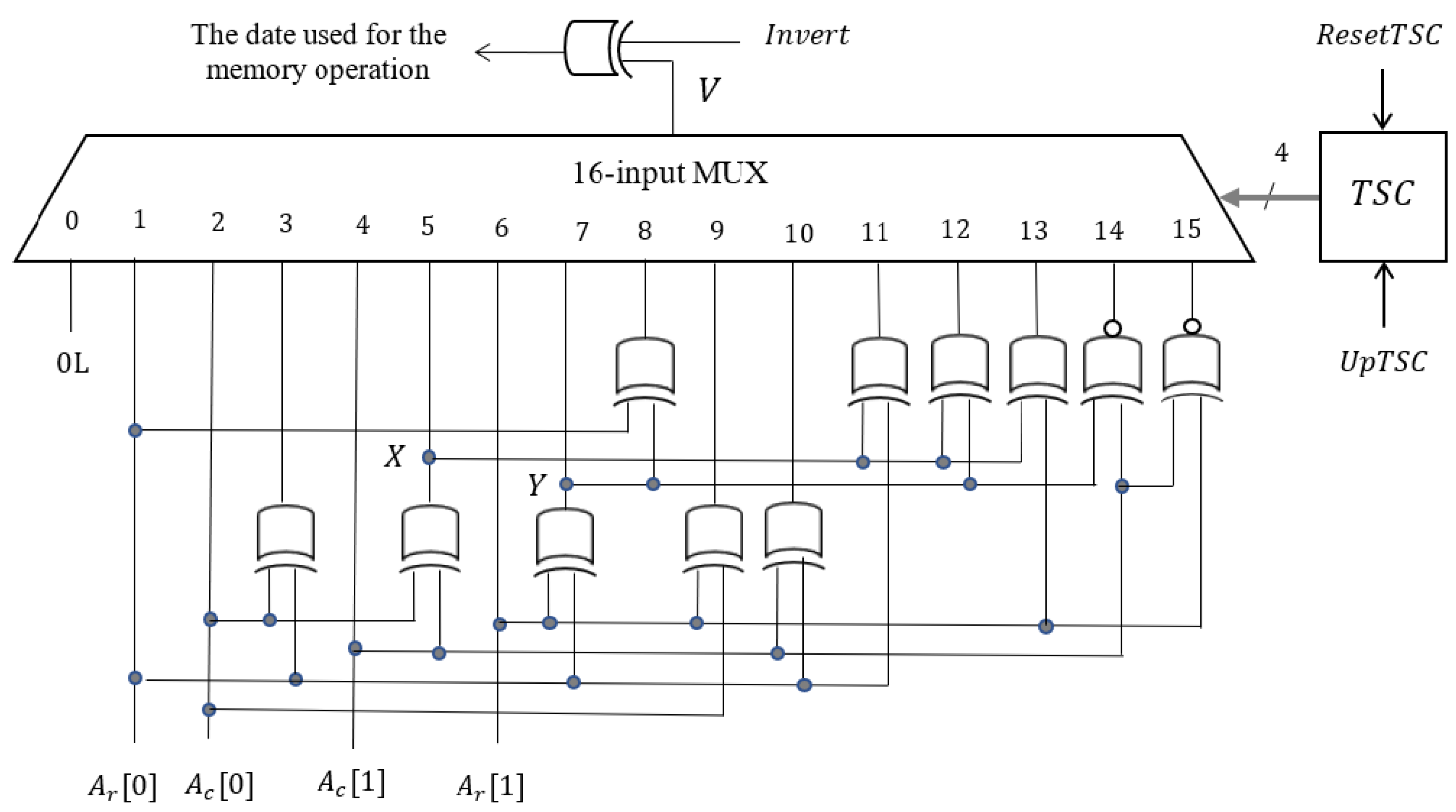

In this work, a new near-optimal test () able to cover the classical NPSF model is proposed. This new test is of length and uses 16 data backgrounds with patterns of 4×4 in size, making it suitable for implementation in BIST-RAM architectures. Compared to the test, this new memory test is significantly shorter and has a simpler structure. The synthesis of the address-based data generation logic for this memory test, considering a possible BIST implementation, is also discussed. This work also highlights the simplicity of address-based data generation logic in the case of 4×4 data backgrounds, compared to 3×3 ones. For the extended NPSF model (ENPSF), a near-optimal test of length is proposed.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 presents assumptions, notations, and some preliminary considerations related to multirun memory tests, or to the necessary and sufficient conditions for detecting memory coupling faults.

Section 3 describes new near-optimal memory tests for the classical NPSF model and the extended NPSF one, respectively, that use 4×4 data background patterns.

Section 4 presents a synthesis of data generation logic for memory operations, for a possible BIST implementation of the proposed memory tests. To emphasize the advantage of the proposed tests, compared to other known memory tests that use 3×3 background patterns, where modulo 3 residues are required for row and column addresses, an additional analysis showing the complexity of generating modulo 3 residues is presented in the Appendix.

Section 5 completes the paper with some conclusions regarding this work.

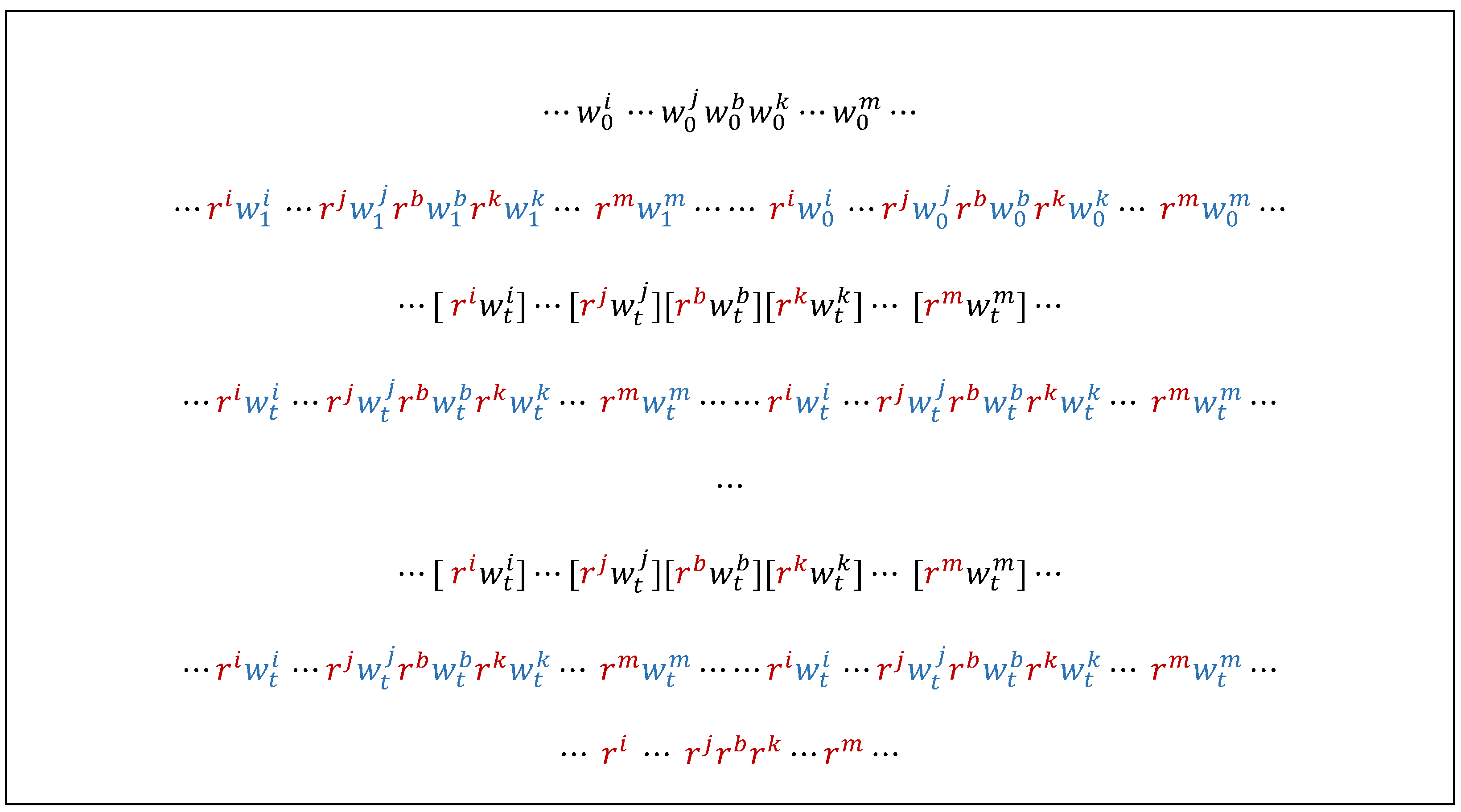

3. Near-Optimal March Tests for the NPSF Model

To cover the classical NPSF model, where a fault sensitization involves a transition write operation in a cell of the coupled cell group with the configuration shown in

Figure 1, a new memory test is proposed, called

. In this test, two march elements are applied sixteen times on different data backgrounds (i.e., a multirun technique). The description of this new march multirun memory test is given in

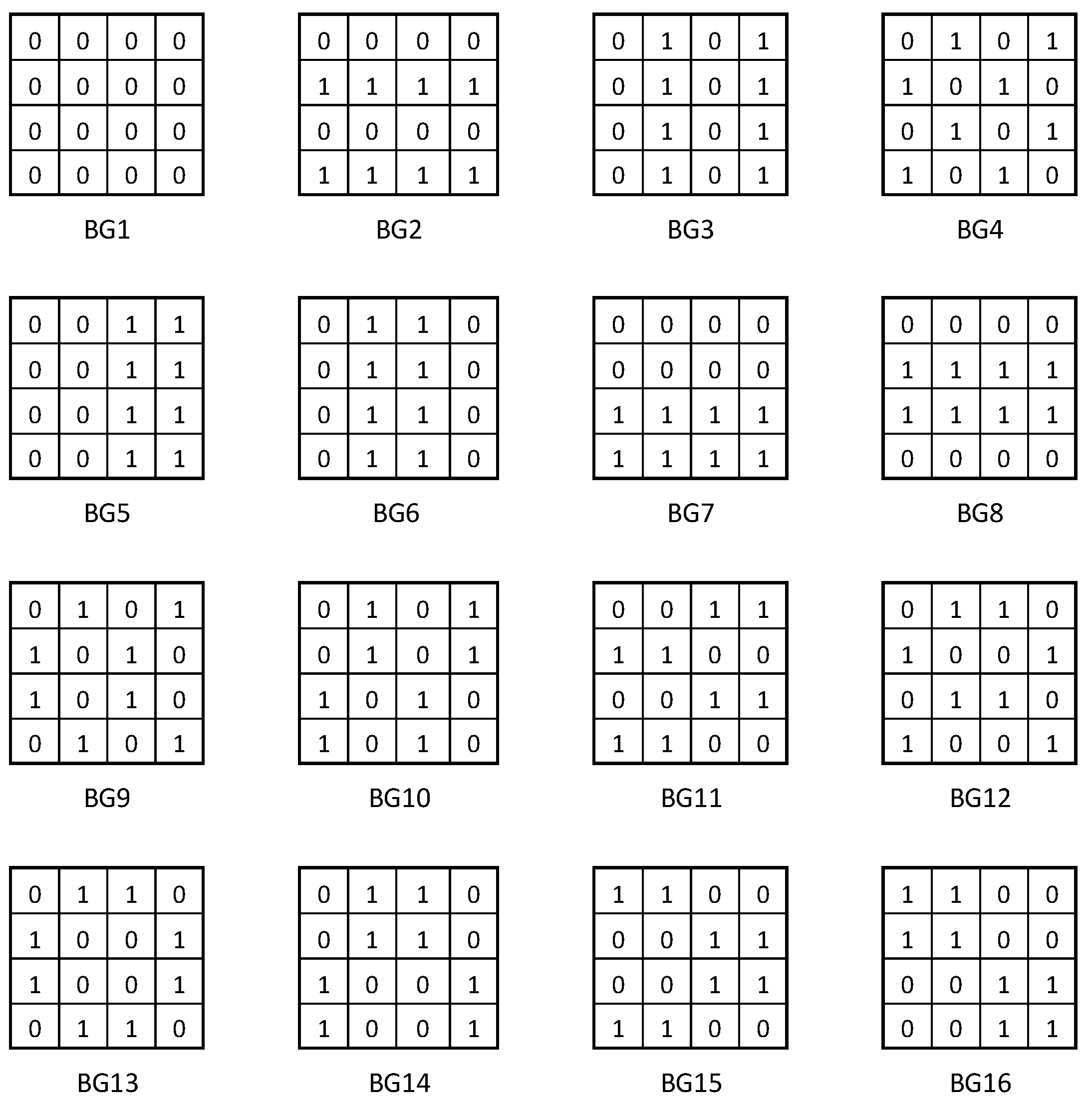

Figure 4, and the sixteen patterns used for memory initialization are shown in

Figure 5.

In this description,

indicates the primary memory initialization sequence while

,

, represent test sequences with background changes, according to the patterns shown in

Figure 5. Note that, any change of data background involves a status update only for half of the memory cells. On the other hand, in order to satisfy the

observability condition, any write operation to change the state of a memory cell is preceded by a read operation. Thus, the initialization sequence

, which is of the form

, involves

write operations, while a test sequence with background change,

,

, requires

read operations and

write operations. Thus, the length of the memory test is:

The ability of the memory test to cover the NPSF model is discussed in the following.

Theorem 1 . The test algorithm is able to detect all unlinked static faults of this classical NPSF model.

Let

be an arbitrary group of five neighboring memory cells corresponding to the well-known NPSF configuration shown in

Figure 1. Considering the order in which these cells are accessed on a memory scan in ascending address order, cells in group

are denoted by

,

and

, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

The ability of the

test algorithm to sensitize and observe any fault that may affect a cell in a cell group

is demonstrated in the following.

To prove this statement, it is shown that during the memory testing, performs all possible operations in the group of cells . In other words, completely covers the graph of states describing the normal functioning of cells in this group.

Given that the test uses 4×4 memory initialization patterns, it follows that the cells selected 4 by 4 per row or column are brought to the same initial state and, consequently, the same operations are then performed on them during the application of a march element. Starting from this observation, the memory cells are divided into 16 classes (subsets),

depending on the residues of the row address modulo 4 (

) and the column address modulo 4 (

), as shown in the following table (

Table 1).

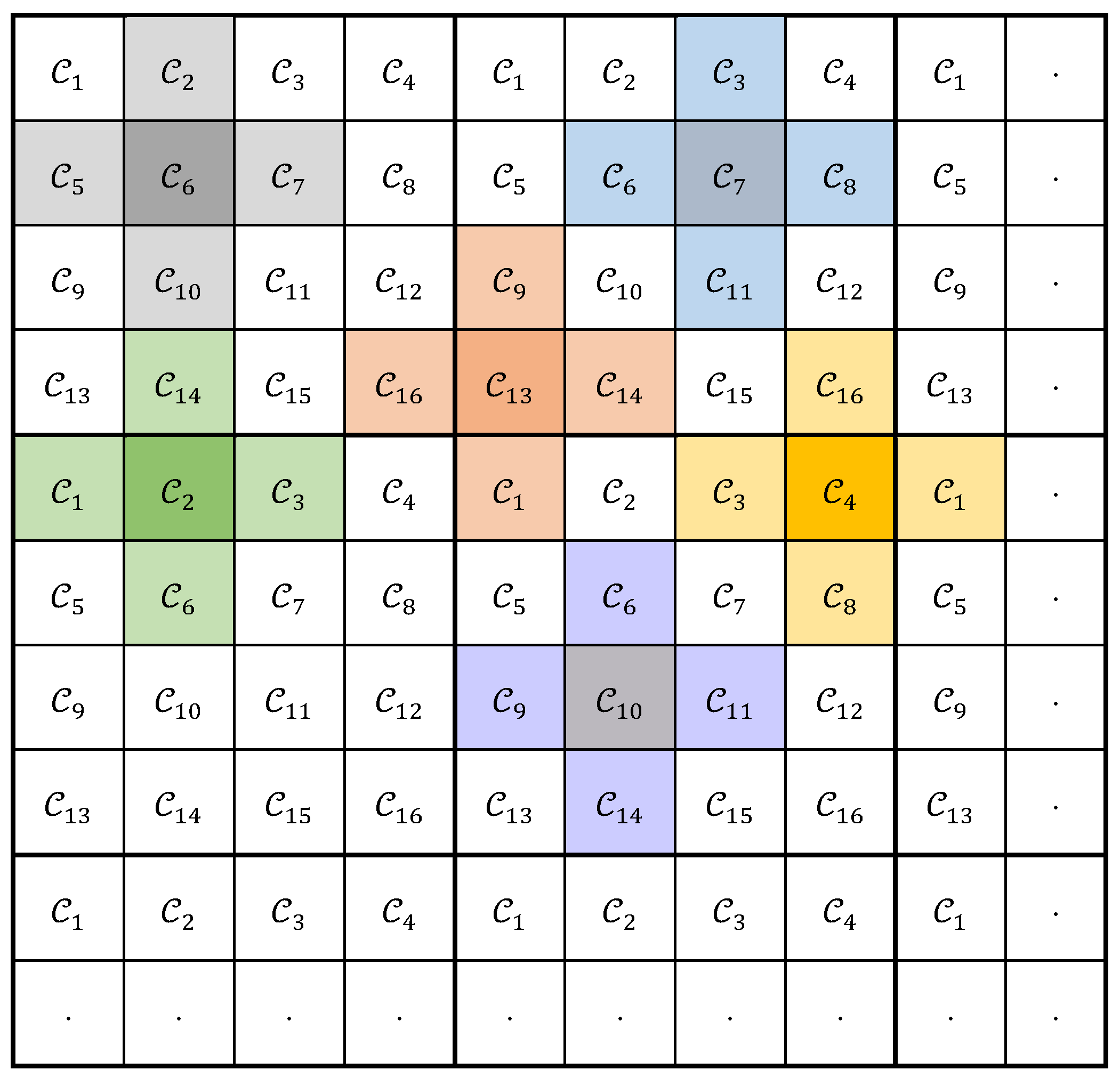

This division of the memory cell set into 16 classes according to row and column addresses is illustrated in

Figure 6.

Let now

be the subset of all

-groups of five cells in the known configuration for which the base cell

. This class division of the

-groups of five cells is also illustrated in

Figure 6. This figure shows that the cells in the neighborhood of the base cells also belong to the same classes. For example, for the groups of cells in the subset

, the cells identified with

belong to

, those identified with

belong to

, and so on.

In the following, let us analyze the initial state for a group of five memory cells in the known configuration, depending on the data background and the class of groups it belongs to .

The status code for a group of cells is a word that includes the five logical values of the component cells, in the form

. It is worth noting that a group

of cells in the state

will reach the complementary state

when the march element

is applied. We say that

and

are complementary states because for any pair

and

the following relation holds:

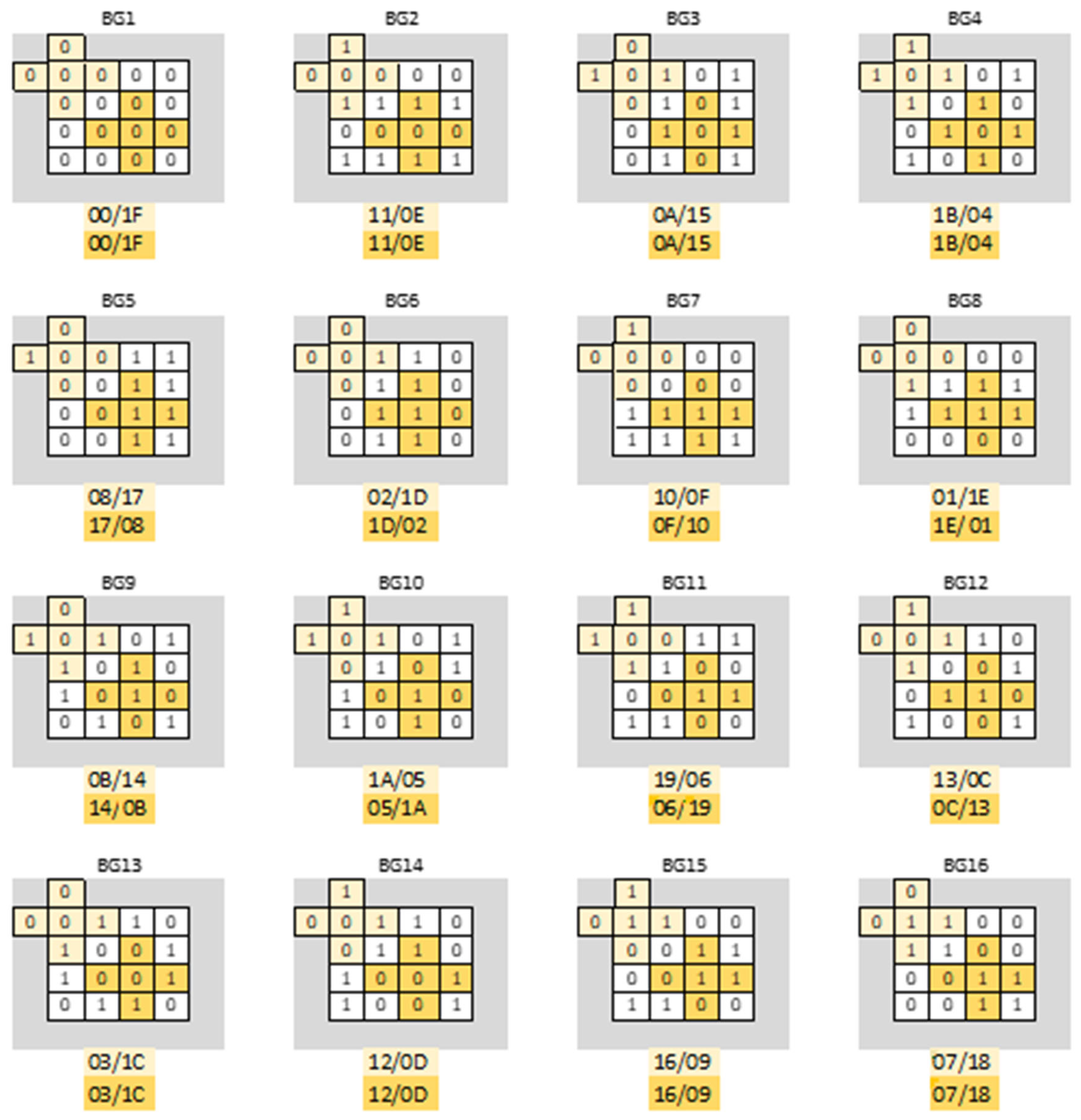

Figure 7 illustrates the initial and complementary states,

and

, for two groups of cells depending on data background, BG

, namely

and

The initial state and the complementary one for a group of cells in the known configuration, depending on the initialization pattern

and the class of which the group belongs

, are presented in

Table 2. In this table, it can be verified that for any group

of five neighboring cells in the known configuration, regardless of the class to which the group belongs (i.e., any column), the 16 background changes result in 16 distinct initial states, such that

Furthermore, for any column in

Table 2, the following equation is valid:

If

represents the set of all

states (as in the truth table), based on (3) and (4) we can write:

Note that the states in any of the 16 columns of

Table 2 satisfy equation (5), which means that all initial states and their complementary ones are different from each other and all together form the set

.

As a remark, identifying those initialization models for which this property is fulfilled has involved a considerable research effort.

It is also important to note that, starting from an initial state , upon execution of the first march element (of the form ), a group of cells is brought to the complementary state , and after the next march element (identical to the first), that group of cells is returned to the initial state .

Based on all these aspects, we can conclude that any group of cells in the known configuration is brought into each of the 32 possible states, and then a march element of the form is applied.

In a full memory scan with the march element

, 5 different transitions are performed in any group of five cells. On the whole, in a group of five cells,

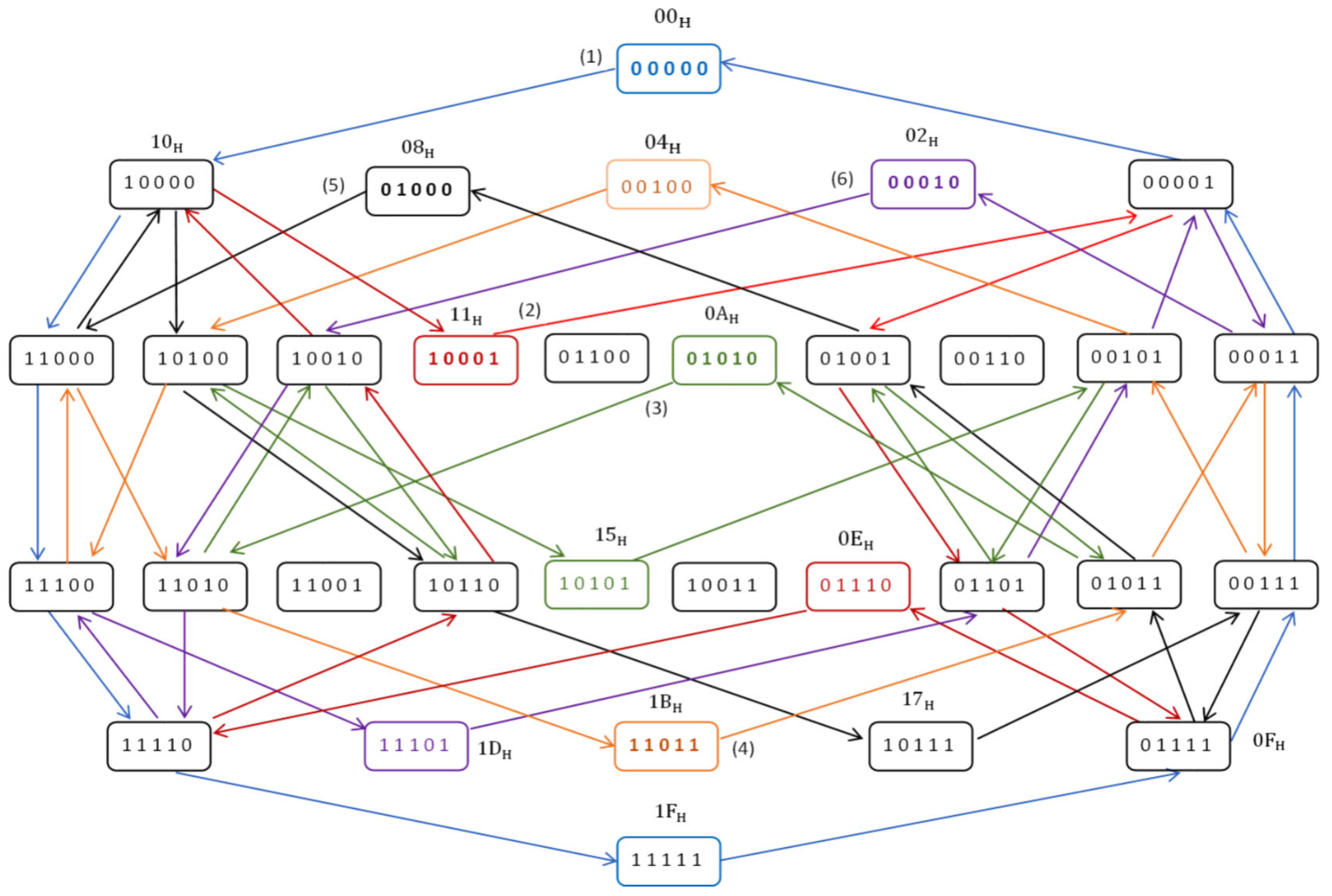

transitions are performed. For example,

Figure 8 shows the transitions performed in a group

of cells of class

in the first 6 of the 16 stages of the memory test. The initial states after the 6 background changes are highlighted in bold. For easier identification, the transitions performed at each iteration are shown in different colors, and for the first transition within an iteration, an identification number is written on the edge.

Next, it is shown that all 160 transitions performed in a group of cells are different transitions and therefore the state transition graph is completely covered.

Figure 9 shows the evolution of the states for a group of cells

, starting from two different initial states,

, when the march element

is applied. The intermediate states that appear in the figure,

and

,

are detailed in

Table 3.

From

Table 3, it follows that, since

,

Note that although often

,

in the two cases, the write operations are performed on different memory cells and therefore the respective transitions are also different. Several such cases are found in

Figure 8, such as the transitions made in the states 10000, 10100, 10010 or 01001.

In conclusion, by applying the memory test, different transitions are performed in the -group of cells, completely covering the state transition graph. Moreover, each of these transitions is performed only once. As a result, the sensitization condition for all coupling faults specific to this classical NPSF model is met.

Proving this property involves verifying the fulfillment of the two observability conditions,

and

, presented in

Section 2. For an easier and more direct verification of the fulfillment of the observability conditions,

Figure 10 shows all the operations performed in a group of cells

during the execution of the

memory test. In the sequence of operations performed on cells in group

, write operations for initialization or background change are written in normal font, and those with the role of memory fault sensitization are highlighted in blue. Read operations that have the role of detecting possible errors resulting from fault sensitization are written in red.

Analyzing the sequence of operations shown in

Figure 10, it can be seen that when a cell is accessed, it is first read, thus checking whether a state change has occurred in the cell, as a result of an influence from another aggressor cell. This check is required by condition

. Also, by analyzing the sequence of operations illustrated in this figure, it can be seen that after performing a write operation on a cell, it is then read (immediately or later) to verify that the operation was performed correctly. Thus, condition

is also met.

With the verification of both conditions regarding the sensitization of all considered memory faults and the ability to detect any resulting errors, the proof of the theorem is complete. ?

Remark 1. For any group of cells that corresponds to the considered NPSF model, the state transition graph is completely covered, and furthermore, each transition is performed only once. That means that the graph of states is Eulerian. The only redundant operations are used for background changes. With this argument, it can be said that this memory test is near-optimal.

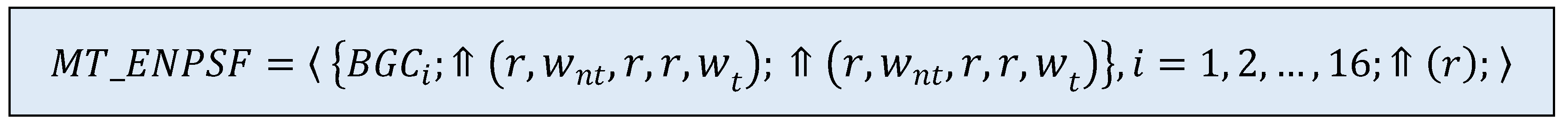

The proposed memory test can be adapted to cover the extended NPSF model (ENPSF), in which memory faults can be sensitized by transition write operations but also by read or non-transition write operations [

41]. To this end, the two march elements of form

are extended to the form

. This extension leads to a near-optimal memory test for the ENPSF model, called

, of length

, as shown in

Figure 11.

Note that in this case, when a certain state is reached, the and operations are first executed and checked, and then the state is changed by a operation.

Remark 2. The ability of each of the two memory tests to cover the considered NPSF model was also verified by simulation. In the case of faults sensitized by transition write operations, the TRAP interrupt was used to simulate memory errors. For the other memory faults, dedicated simulation programs were required.

Remark 3. The proposed tests,

and

, also cover the three-cell CF model involving neighboring memory cells arranged in a corner or on a row or column [

5,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14], in the classical and extended versions, respectively, since the three-cell configurations are included in the five-cell one.

Figure 1.

Cell configuration in the NPSF model.

Figure 1.

Cell configuration in the NPSF model.

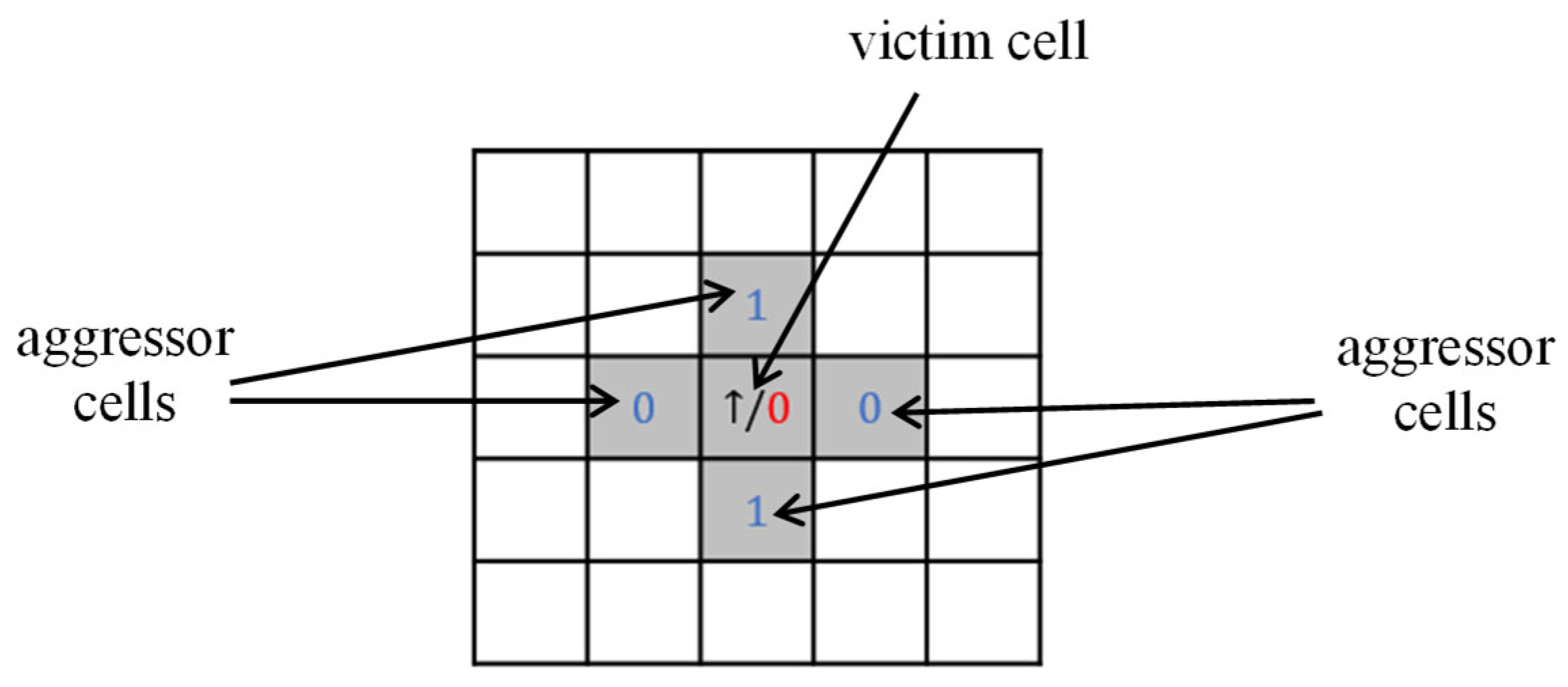

Figure 2.

Example of passive NPSF fault.

Figure 2.

Example of passive NPSF fault.

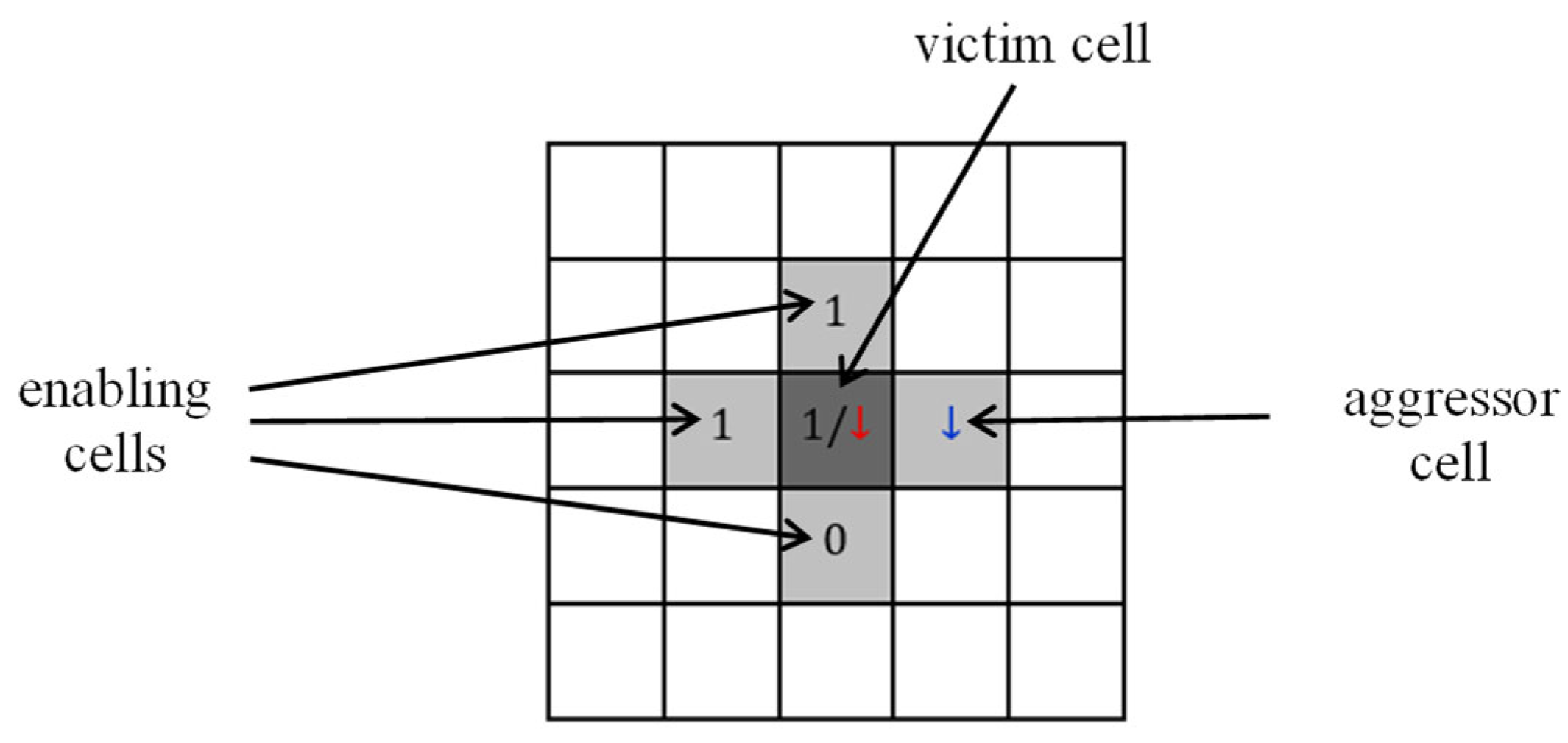

Figure 3.

Example of active NPSF fault.

Figure 3.

Example of active NPSF fault.

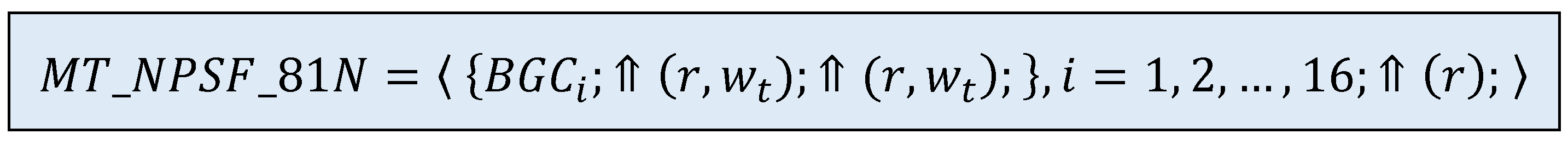

Figure 4.

march memory test.

Figure 4.

march memory test.

Figure 5.

Memory initialization patterns used by the multirun march test

Figure 5.

Memory initialization patterns used by the multirun march test

Figure 6.

Division of memory cells and the -groups of cells, respectively, into 16 classes.

Figure 6.

Division of memory cells and the -groups of cells, respectively, into 16 classes.

Figure 7.

The initial and complementary states, expressed in hexadecimal as / for two groups of cells of classes (light yellow) and (dark yellow), depending on data background: BG.

Figure 7.

The initial and complementary states, expressed in hexadecimal as / for two groups of cells of classes (light yellow) and (dark yellow), depending on data background: BG.

Figure 8.

The transitions performed in a group of 5 cells of class in the first 6 of the 16 iterations. of the memory test.

Figure 8.

The transitions performed in a group of 5 cells of class in the first 6 of the 16 iterations. of the memory test.

Figure 9.

The state evolution for a group of cells by applying the march element starting from different initial states, and .

Figure 9.

The state evolution for a group of cells by applying the march element starting from different initial states, and .

Figure 10.

The operations carried out in a group of cells when applying. the memory test.

Figure 10.

The operations carried out in a group of cells when applying. the memory test.

Figure 11.

march memory test.

Figure 11.

march memory test.

Figure 12.

Data generation logic for the memory test.

Figure 12.

Data generation logic for the memory test.

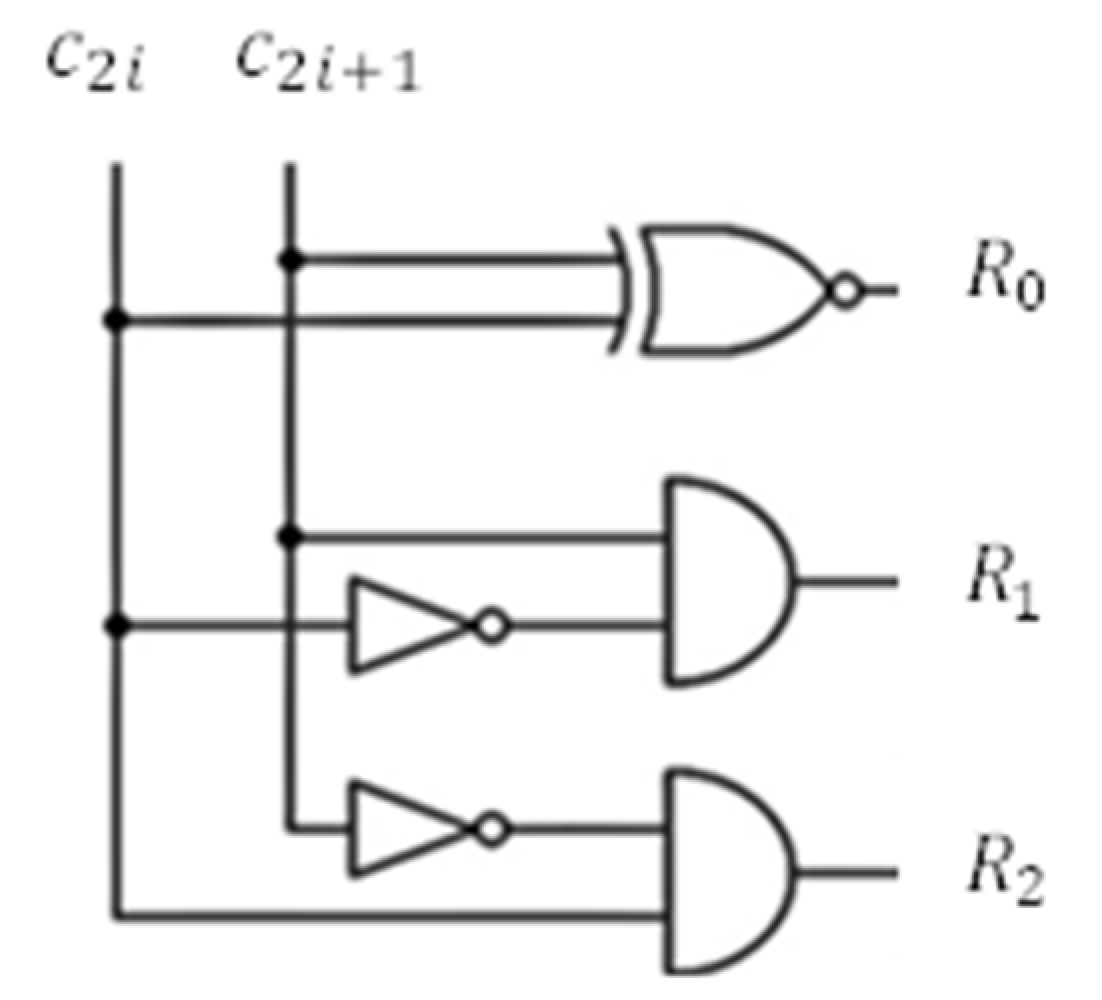

Figure A1.

CLC1 combinational logic.

Figure A1.

CLC1 combinational logic.

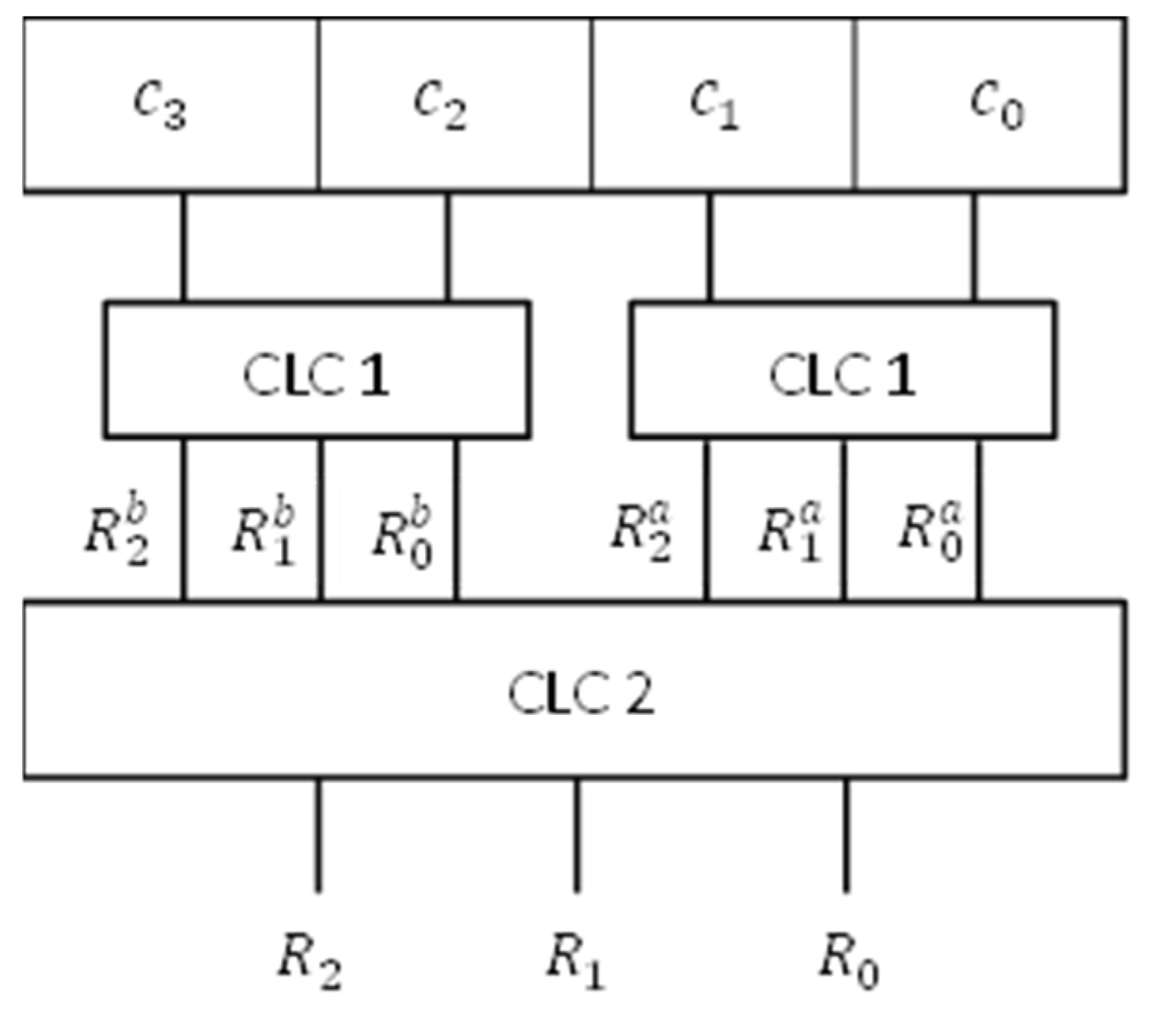

Figure A2.

Processing the values obtained from two basic CLC1 logics.

Figure A2.

Processing the values obtained from two basic CLC1 logics.

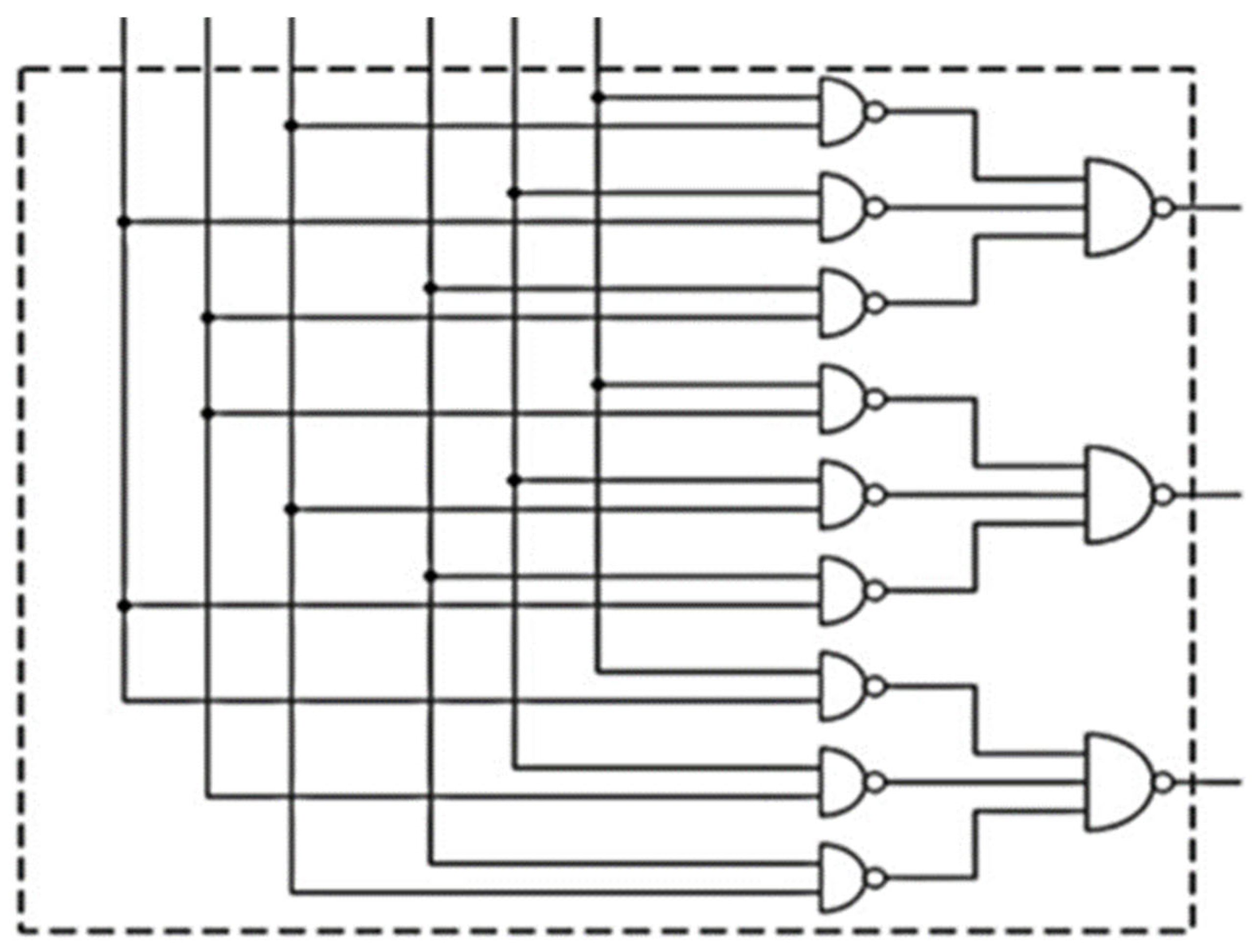

Figure A3.

combinational logic.

Figure A3.

combinational logic.

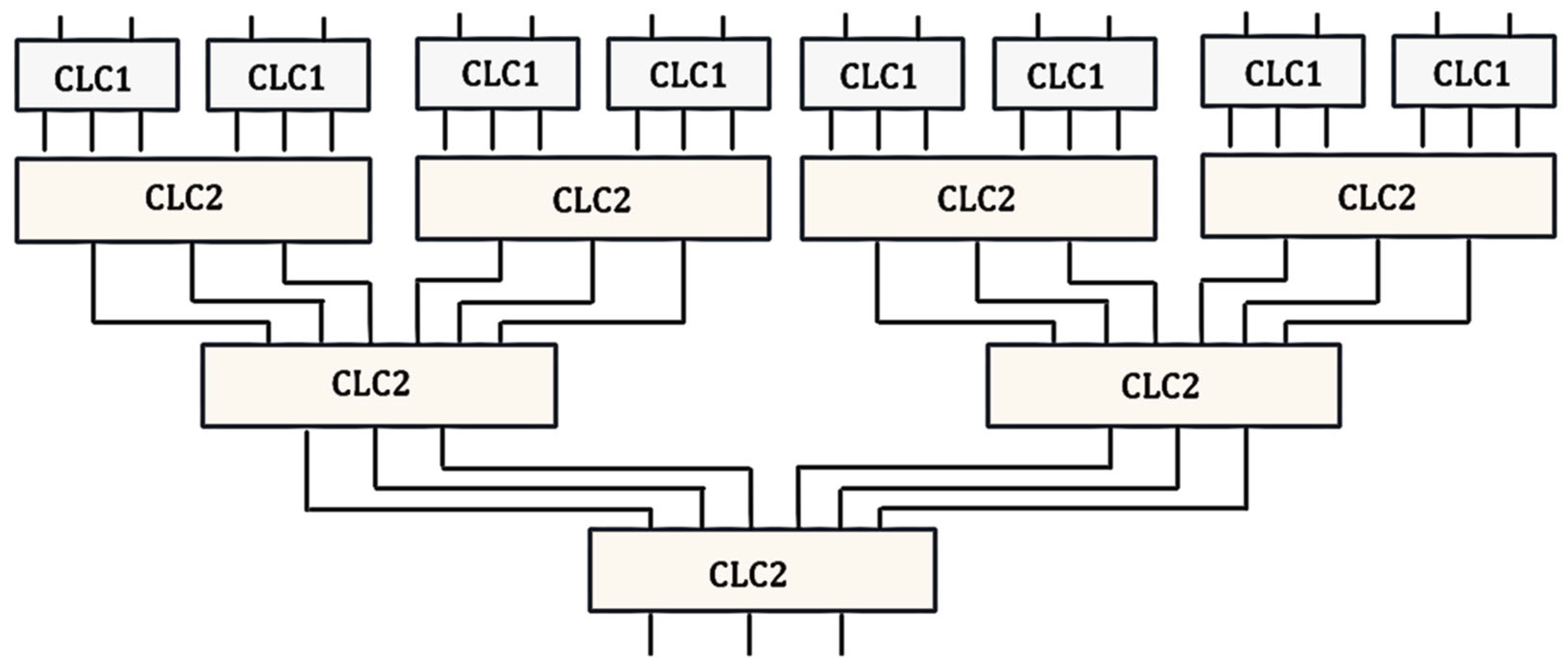

Figure A4.

Example of a series-parallel structure for calculating the value.

Figure A4.

Example of a series-parallel structure for calculating the value.

Table 1.

Dividing cells into classes by row and column addresses.

Table 1.

Dividing cells into classes by row and column addresses.

| |

|

| 0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

0 |

|

|

|

|

| 1 |

|

|

|

|

| 2 |

|

|

|

|

| 3 |

|

|

|

|

Table 2.

The initial and complementary states for a -group of cells. depending on data background and the class of which the group belongs.

Table 2.

The initial and complementary states for a -group of cells. depending on data background and the class of which the group belongs.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| BG1 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

00 |

| 1F |

1F |

1F |

1F |

1F |

1F |

1F |

1F |

1F |

1F |

1F |

1F |

1F |

1F |

1F |

1F |

| BG2 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

0E |

0E |

0E |

0E |

11 |

11 |

11 |

0E |

0E |

11 |

0E |

0E |

| 0E |

0E |

0E |

0E |

11 |

11 |

11 |

11 |

0E |

0E |

0E |

11 |

11 |

0E |

11 |

11 |

| BG3 |

0A |

15 |

0A |

15 |

0A |

15 |

0A |

15 |

0A |

0A |

0A |

15 |

0A |

15 |

0A |

15 |

| 15 |

0A |

15 |

0A |

15 |

0A |

15 |

0A |

15 |

15 |

15 |

0A |

15 |

0A |

15 |

0A |

| BG4 |

1B |

04 |

1B |

04 |

04 |

1B |

04 |

1B |

1B |

04 |

1B |

04 |

04 |

1B |

04 |

1B |

| 04 |

1B |

04 |

1B |

1B |

04 |

1B |

04 |

04 |

1B |

04 |

1B |

1B |

04 |

1B |

04 |

| BG5 |

08 |

02 |

07 |

1D |

08 |

02 |

17 |

1D |

08 |

02 |

17 |

1D |

08 |

02 |

17 |

1D |

| 17 |

1D |

08 |

02 |

17 |

1D |

08 |

02 |

17 |

1D |

08 |

02 |

17 |

1D |

08 |

02 |

| BG6 |

02 |

17 |

1D |

08 |

02 |

17 |

1D |

08 |

02 |

17 |

1D |

08 |

02 |

17 |

1D |

08 |

| 1D |

08 |

02 |

17 |

1D |

08 |

02 |

17 |

1D |

08 |

02 |

17 |

1D |

08 |

02 |

17 |

| BG7 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

01 |

01 |

01 |

01 |

0F |

0F |

0F |

0F |

1E |

1E |

1E |

1E |

| 0F |

0F |

0F |

0F |

1E |

1E |

1E |

1E |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

01 |

01 |

01 |

01 |

| BG8 |

01 |

01 |

01 |

01 |

0F |

0F |

0F |

0F |

1E |

1E |

01 |

1E |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

| 1E |

1E |

1E |

1E |

10 |

10 |

10 |

10 |

01 |

01 |

1E |

01 |

0F |

0F |

0F |

0F |

| BG9 |

0B |

14 |

0B |

14 |

05 |

1A |

05 |

1A |

14 |

0B |

14 |

0B |

1A |

05 |

1A |

05 |

| 14 |

0B |

14 |

0B |

1A |

05 |

1A |

05 |

0B |

14 |

0B |

14 |

05 |

1A |

05 |

1A |

| BG10 |

1A |

05 |

1A |

05 |

0B |

14 |

0B |

14 |

05 |

1A |

05 |

1A |

14 |

0B |

14 |

0B |

| 05 |

1A |

05 |

1A |

14 |

0B |

14 |

0B |

1A |

05 |

1A |

05 |

0B |

14 |

0B |

14 |

| BG11 |

19 |

13 |

06 |

0C |

06 |

0C |

19 |

13 |

19 |

13 |

06 |

0C |

06 |

0C |

19 |

13 |

| 06 |

0C |

19 |

13 |

19 |

13 |

06 |

0C |

06 |

0C |

19 |

13 |

19 |

13 |

06 |

0C |

| BG12 |

13 |

06 |

0C |

19 |

0C |

19 |

13 |

06 |

13 |

06 |

0C |

19 |

0C |

19 |

13 |

06 |

| 0C |

19 |

13 |

06 |

13 |

06 |

0C |

19 |

0C |

19 |

13 |

06 |

13 |

06 |

0C |

19 |

| BG13 |

03 |

16 |

1C |

09 |

0D |

18 |

12 |

07 |

1C |

09 |

03 |

16 |

12 |

07 |

0D |

18 |

| 1C |

09 |

03 |

16 |

12 |

07 |

0D |

18 |

03 |

16 |

1C |

09 |

0D |

18 |

12 |

07 |

| BG14 |

12 |

07 |

0D |

18 |

03 |

16 |

1C |

09 |

0D |

18 |

12 |

07 |

1C |

09 |

03 |

16 |

| 0D |

18 |

12 |

07 |

1C |

09 |

03 |

16 |

12 |

07 |

0D |

18 |

03 |

16 |

1C |

09 |

| BG15 |

16 |

1C |

09 |

03 |

18 |

12 |

07 |

0D |

09 |

03 |

16 |

1C |

07 |

0D |

18 |

12 |

| 09 |

03 |

16 |

1C |

07 |

0D |

18 |

12 |

16 |

1C |

09 |

03 |

18 |

12 |

07 |

0D |

| BG16 |

07 |

0D |

18 |

12 |

16 |

1C |

09 |

03 |

18 |

12 |

07 |

0D |

09 |

03 |

16 |

1C |

| 18 |

12 |

07 |

0D |

09 |

03 |

16 |

1C |

07 |

0D |

18 |

12 |

16 |

1C |

09 |

03 |

| Fulfillment of equation (5) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 3.

The intermediate states illustrated in

Figure 9.

Table 3.

The intermediate states illustrated in

Figure 9.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

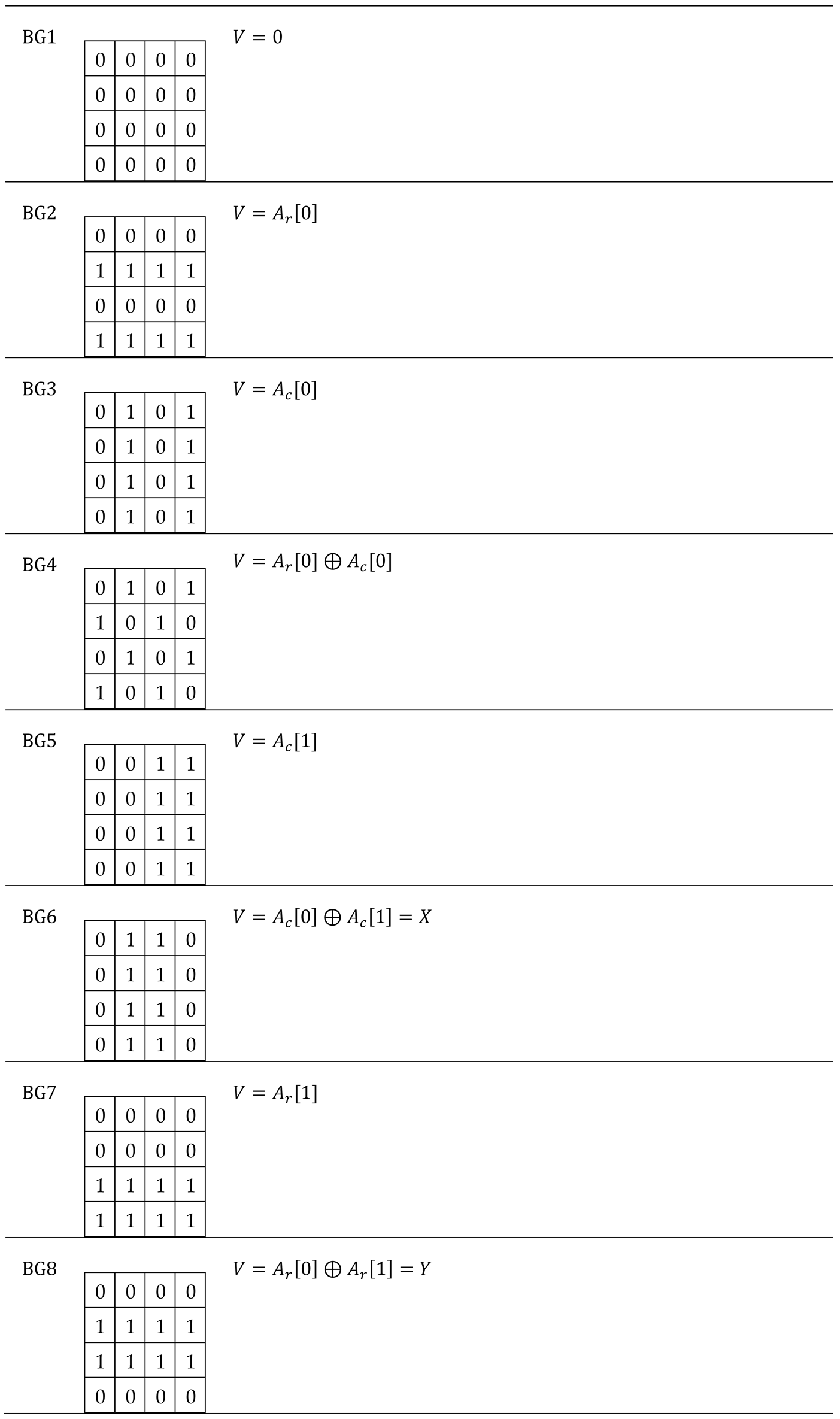

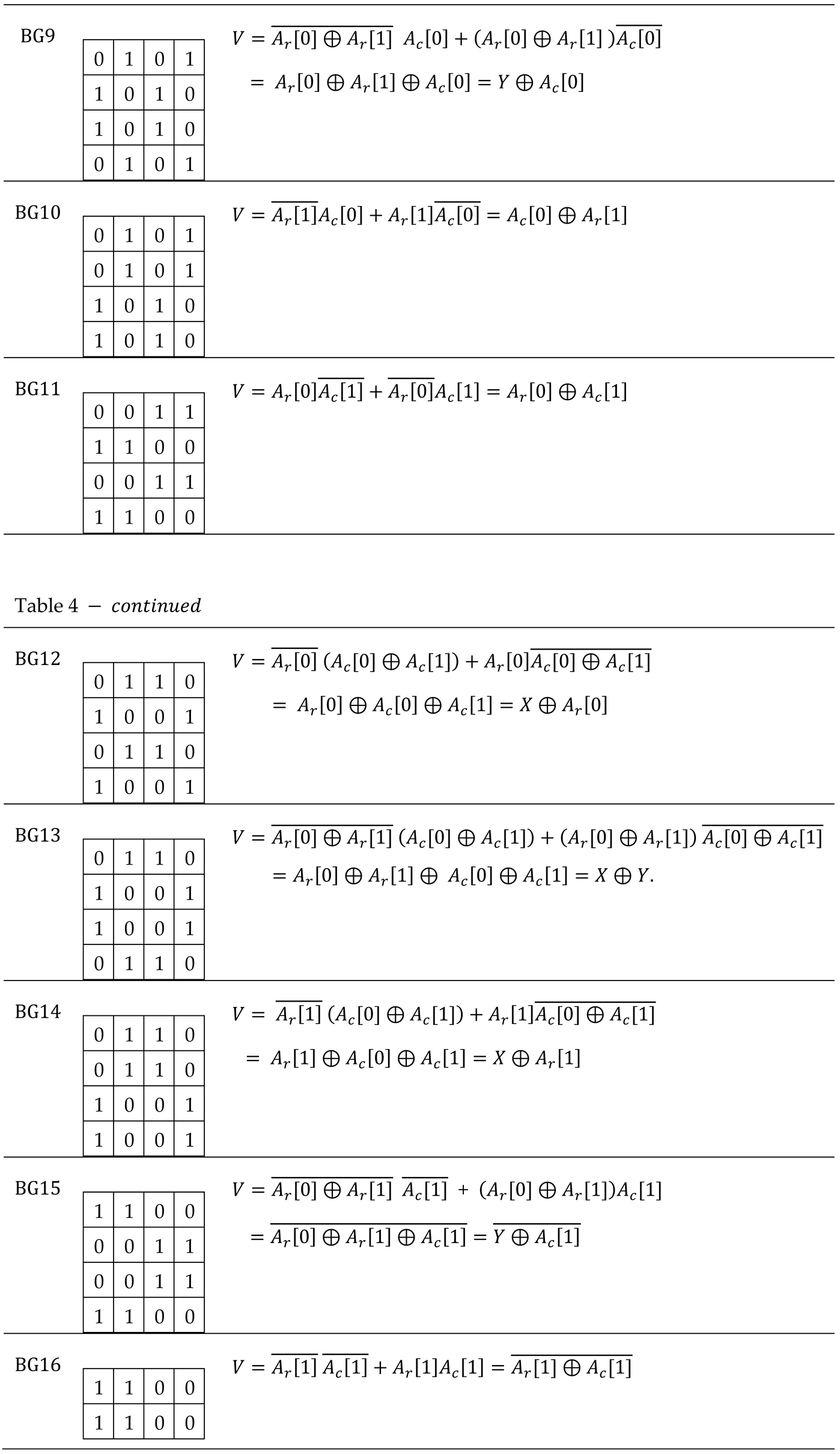

Table 4.

Initialization value of a memory cell depending on the address.

Table 4.

Initialization value of a memory cell depending on the address.

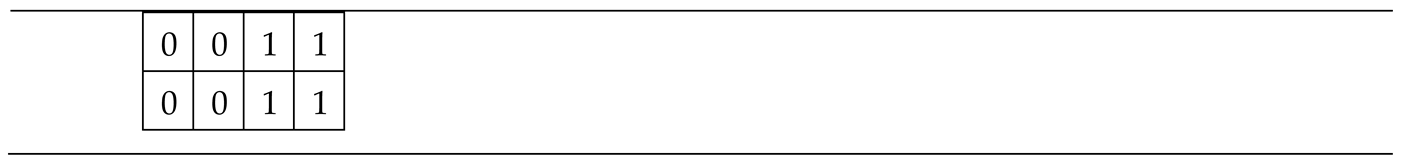

Table A2.

Truth table for logical variables

Table A2.

Truth table for logical variables

|

|

|

|

|

| 0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| 0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| 1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| 1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |