Submitted:

08 July 2025

Posted:

09 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

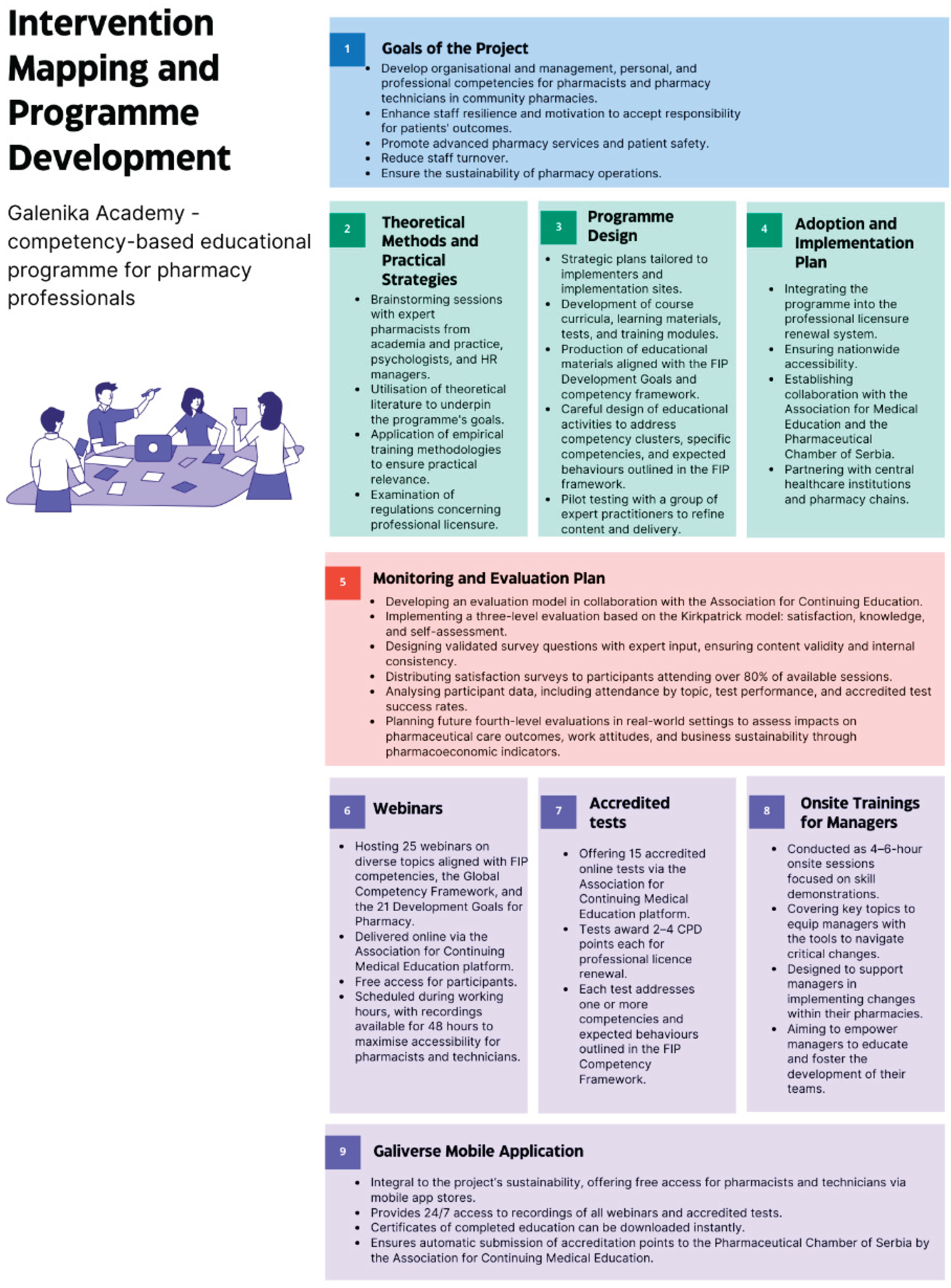

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Tools

2.1.1. Defining Programme Objectives According to the Previous Needs Assessment

2.1.2. Selecting Theory-Based Intervention Methods and Practical Strategies

2.1.3. Designing and Organising Online Lectures, Tests, and Courses

2.1.4. Specifying Adoption and Implementation Plans

2.1.5. Generating a Plan for Evaluating Programme Outcomes

2.2. Setting, Sampling, and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis, Interpretation, and Storage

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Programme Participants

3.2. Demographic Characteristics of the Satisfaction Survey (Participants Who Attended ≥ 80% of the Education)

3.3. Participant Engagement and Performance Outcomes

3.3.1. Online Education: Webinars Accessible to the Entire Pharmacy Community

3.3.2. Accredited Tests: Available to All Pharmacy Professionals

3.3.3. Onsite Trainings for Pharmacy Managers

3.4. Galenika Academy Satisfaction Questionnaire Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| CPD | Continuous Professional Development |

| FIP | International Pharmaceutical Federation |

References

- Banse, E.; Petit, G.; Cool, G.; Durbecq, J.; Hennequin, I.; Khazaal, Y.; de Timary, P. Case study: Developing a strategy combining human and empirical interventions to support the resilience of healthcare workers exposed to a pandemic in an academic hospital. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1023362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Förster, C.; Füreder, N.; Hertelendy, A. Why time matters when it comes to resilience: how the duration of crisis affects resilience of healthcare and public health leaders. Public Health 2023, 215, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, I.M.; Moretti, F.; Purgato, M.; Barbui, C.; Wu, A.W.; Rimondini, M. Dealing With Adverse Events: A Meta-analysis on Second Victims' Coping Strategies. J Patient Saf 2020, 16, e51–e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, I.M.; Moretti, F.; Campagna, I.; Benoni, R.; Tardivo, S.; Wu, A.W.; Rimondini, M. Promoting the Psychological Well-Being of Healthcare Providers Facing the Burden of Adverse Events: A Systematic Review of Second Victim Support Resources. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, I.M.; Moretti, F.; Purgato, M.; Barbui, C.; Wu, A.W.; Rimondini, M. Psychological and Psychosomatic Symptoms of Second Victims of Adverse Events: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Patient Saf 2020, 16, e61–e74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burlison, J.D.; Quillivan, R.R.; Scott, S.D.; Johnson, S.; Hoffman, J.M. The Effects of the Second Victim Phenomenon on Work-Related Outcomes: Connecting Self-Reported Caregiver Distress to Turnover Intentions and Absenteeism. J Patient Saf 2021, 17, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann, E.; Falkenbach, M.; Brînzac, M.G.; Correia, T.; Panagioti, M.; Rechel, B.; Sagan, A.; Santric-Milicevic, M.; Ungureanu, M.I.; Wallenburg, I.; Burau, V. Tackling the primary healthcare workforce crisis: time to talk about health systems and governance-a comparative assessment of nine countries in the WHO European region. Hum Resour Health 2024, 22, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, L.J.; Neelam, D. World patient safety day: A call for action on health worker safety. Journal of Patient Safety and Risk Management 2020, 25, 171–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevan, A.; Rivera, R.; Najhawan, M.; Saadat, S.; Strehlow, M.; Rao, G.V.R.; Youm, J. Assessing the Efficacy of a Novel Massive Open Online Soft Skills Course for South Asian Healthcare Professionals. J Med Syst 2024, 48, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astier-Peña, M.P.; Martínez-Bianchi, V.; Torijano-Casalengua, M.L.; Ares-Blanco, S.; Bueno-Ortiz, J.M.; Férnandez-García, M. The Global Patient Safety Action Plan 2021-2030: Identifying actions for safer primary health care. Aten Primaria 2021, 53, 102224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Caring for those who care: Guide for the development and implementation of occupational health and safety programmes for health workers: Executive summary. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240040779 (accessed on 08.07.2025).

- Dreischulte, T.; van den Bemt, B.; Steurbaut, S.; European Society of Clinical Pharmacy. European Society of Clinical Pharmacy definition of the term clinical pharmacy and its relationship to pharmaceutical care: a position paper. Int J Clin Pharm 2022, 44, 837–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allemann, S.S.; van Mil, J.W.; Botermann, L.; Berger, K.; Griese, N.; Hersberger, K.E. Pharmaceutical care: the PCNE definition 2013. Int J Clin Pharm 2014, 36, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, J.B.K.; Yap, C.Y.H.; Tan, S.L.L.; Thong, X.R.; Fang, Y.; Smith, H.E. General practitioners' perceptions of the roles of community pharmacists and their willingness to collaborate with pharmacists in primary care. J Pharm Policy Pract 2023, 16, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Molina, A.I.; Benrimoj, S.I.; Ferri-Garcia, R.; Martinez-Martinez, F.; Gastelurrutia, M.A.; Garcia-Cardenas, V. Development and validation of a tool to measure collaborative practice between community pharmacists and physicians from the perspective of community pharmacists: the professional collaborative practice tool. BMC Health Serv Res 2022, 22, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griese-Mammen, N.; Hersberger, K.E.; Messerli, M. Leikola, S.; Horvat, N., van Mil, J.W.F., Eds.; Kos, M. PCNE definition of medication review: reaching agreement. Int J Clin Pharm 2018, 40, 1199-1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundipe, A.; Sim, T.F.; Emmerton, L. The case to improve technologies for pharmacists' prescribing. Int J Pharm Pract 2023, 31, 113–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, I.; Bader, L.R.; Galbraith, K. A global survey on trends in advanced practice and specialisation in the pharmacy workforce. Int J Pharm Pract 2020, 28, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.; Bates, I.; Beck, D.; Brock, T.P.; Futter, B.; Mercer, H.; Rouse, M.; Whitmarsh, S.; Wuliji, T.; Yonemura, A. The WHO UNESCO FIP Pharmacy Education Taskforce. Hum Resour Health 2009, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreischulte, T.; Fernandez-Llimos, F. Current perceptions of the term Clinical Pharmacy and its relationship to Pharmaceutical Care: a survey of members of the European Society of Clinical Pharmacy. Int J Clin Pharm 2016, 38, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, J.P.B.; Torre, C.; Sousa Lobo, J.M.; Sepodes, B. A review of the continuous professional development system for pharmacists. Hum Resour Health 2022, 20, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koudmani, D.; Bader, L.R.; Bates, I. Developing and validating development goals towards transforming a global framework for pharmacy practice. Res Social Adm Pharm 2024, 20, 1118–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udoh, A.; Bruno-Tomé, A.; Ernawati, D.K.; Galbraith, K.; Bates, I. The development, validity and applicability to practice of pharmacy-related competency frameworks: A systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm 2021, 17, 1697–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udoh, A.; Bruno-Tomé, A.; Ernawati, D.K.; Galbraith, K.; Bates, I. The effectiveness and impact on performance of pharmacy-related competency development frameworks: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Social Adm Pharm 2021, 17, 1685–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meilianti, S.; Galbraith, K.; Bader, L.; Udoh, A.; Ernawati, D.; Bates, I. The development and validation of a global advanced development framework for the pharmacy workforce: a four-stage multi-methods approach. Int J Clin Pharm 2023, 45, 940–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushworth, G.F.; Innes, C.; Macdonald, A.; MacDonald, C.; McAuley, L.; McDavitt, A.; Stewart, F.; Bruce, R. Development of innovative simulation teaching for advanced general practice clinical pharmacists. Int J Clin Pharm 2021, 43, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimonjić, I.; Marinković, V.; Mira, J.J.; Djokic, B.B.; Odalović, M. Addressing the second victim phenomenon among community pharmacists and its impact on clinical pharmacy practice: a consensus study. Int J Clin Pharm 2025, 47, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle-Payne, K.; Forsyth, P.; Johnson, C.F.; Harrison, H.; Robertson, S.; Weidmann, A.E. The standards of practice for delivery of polypharmacy and chronic disease medication reviews by general practice clinical pharmacists: a consensus study. Int J Clin Pharm 2022, 44, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojkov, S.; Tadić, I.; Crnjanski, T.; Krajnović, D. Assessment and self-assessment of the pharmacists' competencies using the global competency framework (GbCF) in Serbia. Vojnosanit Pregl 2016, 73, 803–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomew, L.K.; Parcel, G.S.; Kok, G. Intervention mapping: a process for developing theory- and evidence-based health education programs. Health Educ Behav 1998, 25, 545–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; Lamb, S.E.; Dixon-Woods, M.; McCulloch, P.; Wyatt, J.C.; Chan, A.W.; Michie, S. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ 2014, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, M.; Prunuske, J.; DiCorcia, M.; Learman, L.A.; Mutcheson, B.; Huang, G.C. The DoCTRINE Guidelines: Defined Criteria To Report Innovations in Education. Acad Med 2022, 97, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Awaisi, A.; Koummich, S.; Koraysh, S.; El Hajj, M.S. Patient Safety Education in Entry to Practice Pharmacy Programs: A Systematic Review. J Patient Saf. 2022, 18, e373–e386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friedman, E.A.; Bickford, R.; Bjork, C.; Campbell, J.; Cometto, G.; Finch, A.; Kane, C.; Wetter, S.; Gostin, L. The global health and care worker compact: evidence base and policy considerations. BMJ Glob Health 2023, 8, e012337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIsaac, M.; Buchan, J.; Abu-Agla, A.; Kawar, R.; Campbell, J. Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030-A Five-Year Check-In. Hum Resour Health 2024, 22, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballaram, S.; Perumal-Pillay, V.; Suleman, F. A scoping review of continuing education models and statutory requirements for pharmacists globally. BMC Med Educ 2024, 24, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader. ; Kusynová, Z.; Duggan, C. FIP Perspectives: Realising global patient safety goals requires an integrated approach with pharmacy at the core. Res Social Adm Pharm 2019, 15, 815–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajis, D.; Al-Haqan, A.; Mhlaba, S.; Bruno, A.; Bader, L.; Bates, I. An evidence-led review of the FIP global competency framework for early career pharmacists training and development. Res Social Adm Pharm 2023, 19, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, G.F.B.; Amoadu, M.; Obeng, P.; Sarkwah, H.N.; Malcalm, E.; Abraham, S.A.; Baah, J.A.; Agyare, D.F.; Banafo, N.E.; Ogaji, D. Effectiveness of eLearning programme for capacity building of healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health 2024, 22, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BinDhim, N.F.; Althumiri, N.A.; Albluwi, R.A.; Aljadhey, H.S. Competencies, skills, and personal characteristics needed for pharmacy leaders: An in-depth interview. Saudi Pharm 2024, 32, 102181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smidt, A.; Balandin, S.; Sigafoos, J.; Reed, V.A. The Kirkpatrick model: A useful tool for evaluating training outcomes. J Intellect Dev Disabil 2009, 34, 266–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.F.; Beck, C.T. The content validity index: are you sure you know what's being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health 2006, 29, 489–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, L.A. Snowball Sampling. Annals of Mathematical Statistics 1961, 32, 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamiru, H.; Huluka, S.A.; Negash, B.; Hailu, K.; Mekonen, Z.T. National Continuing Professional Development (CPD) training needs of pharmacists in Ethiopia. Hum Resour Health 2023, 21, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alnahar, S.A.; Darwish, R.M.; Al Qasas, S.Z.; Al Shabani, M.M.; Bates, I. Identifying training needs of practising community pharmacists in Jordan-a self-assessment study. BMC Health Serv Res 2024, 24, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safwan, J.; Akel, M.; Sacre, H.; Haddad, C.; Sakr, F.; Hajj, A.; Zeenny, R.M.; Iskandar, K.; Salameh, P. Academic pharmacist competencies in ordinary and emergency situations: content validation and pilot description in Lebanese academia. BMC Med Educ 2023, 23, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeineddine, L.; Sacre, H.; Haddad, C.; Zeenny, M.R.; Akel, M.; Hajj, A.; Salameh, P. The association of management and leadership competencies with work satisfaction among pharmacists in Lebanon. J Pharm Policy Pract 2023, 16, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimonjić, I.; Marinković, V.; Mira, J.J.; Knežević, B.; Djokic, B.B.; Bogavac-Stanojević, N.; Odalović, M. The second victim experience and support tool: a cross-cultural adaptation, validation and psychometric evaluation of the Serbian version for pharmacy professionals (SR-SVEST-R). Int J Clin Pharm 2025, 47, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Platform for Vocational Excellence in Health Care. Innovation and development of the healthcare sector. Available online: https://euveca.eu/ (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Blueprint alliance for a future health workforce strategy on digital and green skills. Shaping the health and care workforce of tomorrow. Available online: https://bewell-project.eu/ (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- The Pharmaceutical Chamber of Serbia. Register of Pharmacists. Available online: https://www.farmkom.rs/registar-farmaceuta (accessed on 8 July 2025).

| Sociodemographic variables (n=222) | Categories | n (%) | Mean (min-max) (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 43 (20-74) (11.6) | ||

| Years of work experience | 17 (1-65) (11.9) | ||

| Gender | Female | 203 (91.4) | |

| Male | 19 (8.6) | ||

| Level of education | Secondary School | 58 (26.1) | |

| College - Bachelor's Degree | 14 (6.3) | ||

| University - Master's Degree | 107 (48.2) | ||

| Specialised Academic Studies | 29 (13.1) | ||

| Health Specialisation | 3(1.3) | ||

| Master's or Doctorate | 11 (4.9) | ||

| Job position | Pharmacy technician in a community pharmacy | 75 (33.8) | |

| Pharmacist in a community pharmacy | 147 (66.2) | ||

| Type of institution | Private Pharmacy | 193 (87.0) | |

| State Pharmacy | 29 (13.0) | ||

| Size of the city | Rural area | 22 (9.9) | |

| Smaller town (up to 100,000 inhabitants) | 90 (40.5) | ||

| Medium-sized city (100-200,000 inhabitants) | 30 (13.5) | ||

| Large city (over 200,000 inhabitants) | 80 (36.0) |

| Webinar topics | Competence cluster 1 | Competencies | Number of participants |

|---|---|---|---|

| "Small school of resilience for healthcare professionals – burnout" | 1. Pharmaceutical Public Health, 4. Professional/Personal | 1.1 Emergency response, 4.5 Leadership and self-regulation, 4.7 Professional and ethical practice | 787 |

| "Small school of resilience for healthcare professionals – second victims" | 1. Pharmaceutical Public Health, 4. Professional/Personal | 1.1 Emergency response, 4.5 Leadership and self-regulation | 692 |

| "Teamwork in healthcare" | 1. Pharmaceutical Public Health, 3. Organisation and Management | 3.2 Human resources management | 563 |

| "Small school of resilience for healthcare professionals – resilience" | 1. Pharmaceutical Public Health, 4. Professional/Personal | 1.1 Emergency response, 4.5 Leadership and self-regulation | 452 |

| "Communication in healthcare" | 1. Pharmaceutical Public Health, 4. Professional/Personal | 4.1 Communication skills | 438 |

| "Quality in pharmaceutical care" | 4. Professional/Personal | 4.2. Continuing Professional Development (CPD), 4.8 Quality assurance and research in the workplace | 433 |

| "Why is time management important for pharmacists in pharmacies?" | 3. Organisation and Management, 4. Professional/Personal | 3.2. Human resources management, 3.6. Workplace management, 4.5 Leadership and self-regulation | 752 |

| "Risk management in pharmaceutical care" | 1. Pharmaceutical Public Health, 3. Organisation and Management, 4. Professional/Personal | 1.1 Emergency response, 3.3 Improvement of service, 3.4 Procurement, 3.5 Supply chain management, 4.5. Leadership and self-regulation, 4.6. Legal and regulatory practice | 734 |

| "Why are digital communication and leadership important for pharmacists?" | 4. Professional/Personal | 4.1 Digital literacy, 4.5. Leadership and self-regulation | 650 |

| "Why is negotiation important for pharmacists?" | 3. Organisation and Management | 3.1 Budget and reimbursement, 3.4 Procurement, 3.5 Supply chain management | 570 |

| "Why team development is important for pharmacists" | 3. Organisation and Management | 3.2 Human resources management | 558 |

| "How to motivate employees in pharmacies?" | 3. Organisation and Management, 4. Professional/Personal | 3.2 Human resources management, 3.6. Workplace management, 4.5 Leadership and self-regulation | 514 |

| "Why a business plan is important for a new service in a pharmacy" | 3. Organisation and Management | 3.1. Budget and reimbursement, 3.2 Human resources management, 3.3 Improvement of service | 446 |

| "Why conflict management is important for pharmacists" | 4. Professional/Personal | 4.4. Interprofessional collaboration | 410 |

| "Why is communication important for pharmacists in pharmacies?" | 4. Professional/Personal | 4.1 Communication skills, 4.4. Interprofessional collaboration | 375 |

| "Why is business continuity management important in pharmacies?" | 3. Organisation and Management, 4. Professional/Personal | 3.1. Budget and reimbursement, 3.6 Workplace management, 4.8 Quality assurance and research in the workplace | 286 |

| "Pharmacy as a business system and the development of personal skills" | 3. Organisation and Management | 3.1 Budget and reimbursement, 3.2 Human resources management, 3.6 Workplace management | 269 |

| "Why is research in pharmaceutical practice important for pharmacists?" | 3. Organisation and Management, 4. Professional/Personal | 3.3. Improvement of service, 4.2. Continuing Professional Development (CPD), Quality assurance and research in the workplace, 4.3. Digital literacy, 4.4. Interprofessional collaboration | 250 |

| "Tools for problem solving and business decision-making in pharmacies" | 1. Pharmaceutical Public Health, 3. Organisation and Management, 4. Professional/Personal | 1.1 Emergency response, 3.3 Improvement of services, 3.6 Workplace management, 4.7 Professional and ethical practice | 239 |

| "Why is performance management important for pharmacy professionals?" | 3. Organisation and Management, 4. Professional/Personal | 3.2 Human resources management, 3.6 Workplace management, 4.2 Continuing Professional Development (CPD) | 189 |

| "Why is employee development important for the business of pharmacies?" | 3. Organisation and management, 4. Professional/Personal | 3.2. Human resources management, 4.2 Continuing Professional Development (CPD) | 172 |

| "Pharmacy marketing mix and brand management" | 4. Professional/Personal | 4.6 Legal and regulatory practice, 4.7 Professional and ethical practice | 171 |

| "Regulations in advertising in pharmacies" | 4. Professional/Personal | 4.6 Legal and regulatory practice, 4.7 Professional and ethical practice | 167 |

| "Project management in pharmaceutical practice" | 3. Organisation and Management, 4. Professional/Personal | 3.1. Budget and reimbursement, 3.6 Workplace management, 4.8 Quality assurance and research in the workplace | 158 |

| "Why are professionalism and ethics important for pharmacy professionals?" | 4. Professional/Personal | 4.6 Legal and regulatory practice, 4.7 Professional and ethical practice | 152 |

| Total | 10,427 |

| Education - accredited test | Accreditation number ² | Expected learning time | Number of questions | Number of points for licence renewal | Number of participants | Number of successfully completed (>60% of questions with correct answers) | Success rate (% of enrolled) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

B-74/23, Re-accreditation B-41/24 | 2 hours for learning, 30 minutes for test completion | 20 | 2 | 725 | 605 | 83.4% |

|

B-88/21, Re-accreditations: B-122/22, B-161/23 | 4 hours for learning, 1 hour for test completion | 40 | 4 | 762 | 654 | 85.8% |

|

B-89/21, Re-accreditations: B-118/22, B-157/23 | 4 hours for learning, 1 hour for test completion | 40 | 4 | 479 | 292 | 61.0% |

|

B-75/23, Re-accreditation B-44/24 | 2 hours for learning, 30 minutes for test completion | 20 | 2 | 572 | 498 | 87.1% |

|

B-20/23, Re-accreditation B-6/24 | 4 hours for learning, 1 hour for test completion | 40 | 4 | 928 | 722 | 77.8% |

|

B-73/23, Re-accreditation B-46/24 | 3 hours for learning, 45 minutes for test completion | 30 | 3 | 521 | 436 | 83.7% |

|

B-79/21, Re-accreditations: B-119/22, B-159/23 | 4 hours for learning, 1 hour for test completion | 40 | 4 | 291 | 216 | 89.7% |

|

B-22/23, Re-accreditation B-11/24 | 2 hours for learning, 20 minutes for test completion | 20 | 2 | 555 | 470 | 84.7% |

|

B-21/23, Re-accreditation B-7/24 | 3 hours for learning, 45 minutes for test completion | 30 | 3 | 813 | 694 | 85.4% |

|

B-77/23, Re-accreditation B-45/24 | 2 hours for learning, 20 minutes for test completion | 20 | 2 | 371 | 297 | 80.1% |

|

B-31/23, Re-accreditation B-10/24 | 2 hours for learning, 30 minutes for test completion | 20 | 2 | 682 | 544 | 79.8% |

|

B-76/23, Re-accreditation B-40/24 | 2 hours for learning, 30 minutes for test completion | 20 | 2 | 361 | 292 | 80.9% |

|

B-29/23, Re-accreditation B-9/24 | 2 hours for learning, 30 minutes for test completion | 20 | 2 | 506 | 482 | 95.3% |

|

B-30/23, Re-accreditation B-8/24 | 2 hours for learning, 30 minutes for test completion | 20 | 2 | 546 | 516 | 94.5% |

|

B-78/23, Re-accreditation B-39/24 | 2 hours for learning, 30 min for completion | 20 | 2 | 140 | 126 | 90.0% |

|

8,252 | 6,844 | 82.9% |

| Training topic | Educational goals | Expected outcomes | Number of participants |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. "Building effective relationships in pharmaceutical practice" | 1. Enhance communication skills for effective collaboration. 2. Understand how to build trust with colleagues and patients. 3. Develop strategies for managing professional relationships. 4. Learn how to improve teamwork and conflict resolution skills. 5. Learn how to strengthen pharmaceutical care effectiveness in pharmacy practice. |

1. Improved communication skills for effective collaboration. 2. Building trust with colleagues and patients. 3. Effective management of professional relationships. 4. Improved teamwork and conflict resolution. 5. Strengthen pharmaceutical care effectiveness in pharmacy practice. |

28 |

| 2. "Effective leadership in pharmaceutical practice" | 1. Understand core principles of leadership in pharmacy practice. 2. Develop skills to inspire and motivate team members. 3. Enhance decision-making and problem-solving abilities. 4. Foster a collaborative and productive work environment. 5. Build strategies for effective team management and performance improvement. |

1. Enhanced understanding of leadership principles in pharmaceutical practice. 2. Improved ability to inspire and motivate pharmacy teams. 3. Strengthened decision-making and problem-solving skills. 4. Creation of a more collaborative and productive workplace. 5. Effective implementation of team management strategies for improved performance. |

30 |

| 3. "Performance management and employee development in pharmacy practice" | 1. Understand the key concepts of performance management in pharmacy practice. 2. Develop skills to assess and improve employee performance. 3. Learn strategies for setting clear goals and expectations. 4. Enhance abilities in providing constructive feedback and coaching. 5. Foster a culture of continuous professional development and growth. |

1. Improved understanding of performance management practices in pharmacy. 2. Enhanced ability to assess and support employee performance effectively. 3. Clear goal setting and expectation management for pharmacy teams. 4. Improved skills in providing constructive feedback and coaching. 5. Stronger culture of continuous professional development and growth within the pharmacy. |

28 |

| 4. "Change management in pharmacy business" | 1. Understand the principles and processes of change management in the pharmacy business. 2. Develop skills to assess and manage change effectively within the pharmacy environment. 3. Learn strategies for overcoming resistance to change and fostering acceptance. 4. Enhance the ability to lead and support teams through change. 5. Explore methods for evaluating the success of change initiatives in pharmacy business operations. |

1. Enhanced understanding of change management principles and processes in the pharmacy business. 2. Improved ability to manage and implement change effectively in the pharmacy setting. 3. Increased competency in addressing resistance to change and promoting acceptance. 4. Stronger leadership skills in guiding teams through change initiatives. 5. Greater capability in evaluating and measuring the success of change efforts within the pharmacy business. |

30 |

| 5. "Change implementation: the impact of (i) resilience, (ii) effective time management, and (iii) change management in the education system on success" | 1. Understand the role of resilience in change implementation. 2. Develop effective time management skills for managing change. 3. Learn key change management strategies for successful implementation. 4. Explore the impact of resilience and time management on educational success. 5. Strengthen skills to adapt and lead in changing educational environments. |

1. Improved resilience in managing and adapting to change. 2. Enhanced time management skills for more effective change implementation. 3. Better understanding and application of change management strategies. 4. Greater ability to assess the impact of resilience and time management on success. 5. Increased capacity to lead and succeed in dynamic educational settings. |

25 |

| Variable | How much are you satisfied with the content of Galenika Academy? | P* Value | How much are you satisfied with the quality of education and the choice of lecturers? | p Value | How much are you satisfied with the content of the materials provided for test preparation? | p Value | How much are you satisfied with the mobile application? | p Value | How much are you satisfied with how education improved your business sustainability? | P Value | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) of participants, n=222 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 - Very dissatisfied | 2 - Dissatisfied | 3 - Neutral | 4 - Satisfied | 5 - Very satisfied | 1 - Very dissatisfied | 2 - Dissatisfied | 3 - Neutral | 4 - Satisfied | 5 - Very satisfied | 1 - Very dissatisfied | 2 - Dissatisfied | 3 - Neutral | 4 - Satisfied | 5 - Very satisfied | 1 - Very dissatisfied | 2 - Dissatisfied | 3 - Neutral | 4 - Satisfied | 5 - Very satisfied | 1 - Very dissatisfied | 2 - Dissatisfied | 3 - Neutral | 4 - Satisfied | 5 - Very satisfied | |||||||

| Are you aware that you have attended ≥ 80% educations within the Galenika Academy? | Yes | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (2.6%) | 25 (12.9%) | 163 (84%) | <0.001 | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (2.6%) | 23 (11.9%) | 165 (85.1%) | <0.001 | 3 (1.5%) | 2 (1.0%) | 7 (3.6%) | 31 (16.0%) | 151 (77.8%) | 0.096 | 12 (6.2%) | 7 (3.6%) | 24 (12.4%) | 32 (16.5%) | 119 (61.3%) | 0.603 | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 23 (11.9%) | 35 (18.0%) | 134 (69.1%) | 0.684 |

| No | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (3.6%) | 3 (10.7%) | 8 (28.6%) | 16 (57.1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3.6%) | 6 (2.4%) | 4 (14.3%) | 17 (60.7%) | 2 (7.1%) | 1 (3.6%) | 2 (7.1%) | 7 (25%) | 16 (27.1%) | 3 (10.7%) | 1 (3.6%) | 4 (14.3%) | 7 (25.0%) | 13 (46.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (21.4%) | 4 (14.3%) | 18 (64.3%) | ||||||

| 0.319 | 0.030 | 0.018 | <0.001 | 0.085 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Have you heard of the Galiverse application? | Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 5 (2.9%) | 26 (15.2%) | 139 (81.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 5 (2.9%) | 20 (11.7%) | 145 (84.8%) | 1 (0.6%) | 3 (1.8%) | 8 (4.7%) | 27 (15.8) | 132 (77.2%) | 5 (2.9%) | 5 (2.9%) | 13 (7.6%) | 33 (19.3%) | 115 (67.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.6%) | 18 (10.5%) | 32 (18.7%) | 120 (70.2) | |||||

| No | 1 (2.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (5.9%) | 7 (13.7%) | 40 (78.4) | 1 (2.0%) | 0 (0.0.%) | 6 (11.8%) | 7 (13.7%) | 37 (72.5%) | 4 (7.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.0%) | 11 (21.6%) | 35 (68.6%) | 10 (19.3%) | 3 (5.9%) | 15 (29.4%) | 6 (11.8%) | 17 (33.3%) | 1 (2.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (21.6%) | 7 (13.6%) | 32 (32.7%) | ||||||

| 0.416 | 0.284 | 0.093 | <0.001 | 0.147 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Do you use the Galiverse application? | Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (3.2%) | 16 (12.8%) | 105 (84.0%0 | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (3.2%) | 14 (11.2%) | 107 (85.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.6%) | 6 (4.8%) | 19 (15.2%) | 98 (78.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 3 (2.4%) | 29 (23.2%) | 92 (73.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 11 (8.8%) | 24 (19.2%) | 89 (71.2%) | |||||

| No | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 4 (4.1%) | 17 (17.5%) | 74 (76.3%) | 1 (1.0%) | 1 (1.0%) | 7 (7.2%) | 13 (13.4%) | 75 (77.3%) | 5 (5.2%) | 1 (1.0%) | 3 (3.1%) | 19 (19.6%) | 69 (71.1%) | 15 (15.5%) | 7 (7.2%) | 25 (25.8%) | 10 (10.3%) | 40 (40.1%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 18 (18.6%) | 15 (15.5%) | 63 (64.9%) | ||||||

| 0.350 | 0.029 | 0.005 | <0.001 | 0.062 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Do you perceive that the programme(s) you attended improved your competence? | Yes | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 7 (3.3%) | 30 (14.1%) | 174 (81.7%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 9 (4.2%) | 24 (11.3%) | 178 (83.6%) | 4 (1.9%) | 3 (1.4%) | 7 (3.3%) | 35 (16.4%) | 164 (77.0%) | 11 (5.2%) | 8 (3.8%) | 26 (12.2%) | 38 (17.8%) | 130 (61.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.05%) | 25 (11.7%) | 37 (17.4%) | 149 (70.0%) | |||||

| No | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (11.1%) | 3 (33.3%) | 5 (55.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (22.2%) | 3 (33.3%) | 4 (44.4%) | 1 (11.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (22.2%) | 3 (33.3%) | 3 (33.3%) | 4 (44.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (22.2%) | 1 (11.1%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (44.4%) | 2 (22.2%) | 3 (33.3%) | ||||||

| <0.001 | 0.009 | <0.001 | 0.346 | 0.476 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Would you recommend an educational program to colleagues who wish to develop professionally? | Yes | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 6 (2.8%) | 33 (15.2%) | 176 (81.1%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 9 (4.1%) | 27 (12.4%) | 179 (82.5%) | 4 (1.8%) | 2 (0.9%) | 9 (4.1%) | 38 (17.5%) | 164 (75.6%) | 15 (6.9%) | 8 (3.7%) | 26 (12.0%) | 39 (18.0%) | 129 (29.4%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 27 (12.4%) | 38 (17.5%) | 150 (69.1%) | |||||

| No | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (40%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | ||||||

| <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| How much are you satisfied with how you have improved your resilience through the educational program? | 1 - Very dissatisfied | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||||

| 2 - Dissatisfied | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (20.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | 2 (40.0%) | ||||||

| 3 - Neutral | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 12.8%) | 15 (28.5%0 | 19 (48.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (17.9%) | 13 (33.3%) | 19 (48.7%) | 3 (7.7%) | 1 (2.6%) | 5 (12.8%) | 18 (46.2%) | 12 (30.8%) | 6 (15.4%) | 2 (5.1%) | 12 (30.8%) | 12 (30.8%) | 7 (17.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.6%) | 23 (29.0%) | 11 (28.2%) | 4 (10.3%) | ||||||

| 4 - Satisfied | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.1%) | 8 (17.0%) | 38 (80.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (6.4%) | 7 (14.9%) | 37 (78.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.1%) | 10 (21.3%) | 36 (76.6%) | 3 (6.4%) | 2 (4.3%) | 10 (21.3%) | 13 (27.7%) | 19 (40.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (10.6%) | 21 (44.7%) | 21 (44.7%) | ||||||

| 5 - Very satisfied | 1 (0.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.8%) | 8 (6.2%) | 119 (92.2%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (0.5%) | 11 (5.0%) | 27 (12.2%) | 182 (82.0%) | 2 (1.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (1.6%) | 8 (6.2%) | 117 (90.7%) | 5 (3.9%) | 3 (2.3%) | 6 (4.7%) | 12 (9.3%) | 103 (79.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4 (3.1%) | 125 (96.9%) | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).