1. Introduction

Influenza A viruses (IAV) are segmented, negative-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses of the Orthomyxoviridae family that affect a broad range of hosts, including birds, humans, and pigs. Pigs are considered “mixing vessels” due to the presence of both α2,3 and α2,6 sialic acid receptors in their respiratory tract, facilitating the replication and reassortment of avian and human IAV strains. Consequently, pigs play a key role in the ecology and evolution of IAVs, with significant implications for public and animal health [

1,

2,

3].

The IAV genome comprises eight gene segments encoding at least ten proteins. Genetic reassortment between different lineages can lead to the emergence of novel strains with pandemic potential. Since the 2009 pandemic, the pH1N1 virus has become endemic in swine populations worldwide, co-circulating with other lineages such as classical H1N1, human-like H1 (huH1), and human-derived H3N2. In Brazil, following multiple introductions of human seasonal IAVs—including H1N1, H1N2, and H3N2—into swine populations, the pH1N1 virus has not only established endemic transmission but also undergone reassortment with previously circulating human-origin strains. These events led to the emergence of genetically diverse lineages and several reassortant viruses currently co-circulating in Brazilian swine herds, as highlighted in recent phylogenetic and phylodynamic studies [

4,

5].

Surveillance of IAV in pigs is typically performed using nasal swabs due to the virus's respiratory tropism. However, studies have reported the detection of IAV RNA in feces of both humans and pigs, indicating potential intestinal shedding or environmental contamination. In swine, experimental infections with avian- and human-origin IAVs have demonstrated the presence of viral RNA in the intestinal tract and feces. This may be explained by the expression of both α2,3- and α2,6-linked sialic acid receptors on intestinal epithelial cells, suggesting the potential for local replication or viral persistence in this tissue [

10,

11]. In humans, the virus has been detected in feces for extended periods, even after respiratory shedding has declined, raising questions about similar shedding patterns in pigs [

6,

7,

8].

During outbreaks, the presence and viability of swine-origin IAV (swIAV) in environmental matrices—such as airborne particles, oral fluids, and fomites—have been consistently demonstrated [

12]. Environmental transmission has also been inferred from the early infection of suckling piglets through contaminated udder skin of lactating sows. In human public health, wastewater surveillance has emerged as a valuable strategy for monitoring IAV circulation, with viral RNA levels in sewage correlating with community incidence and supporting early outbreak detection [

13]. In swine production, however, effluent sampling has typically been restricted to the detection of environmentally stable DNA viruses—such as circoviruses and adenoviruses—routinely excreted in feces [

14]. The use of effluent for RNA virus detection, including IAV, remains underexplored in swine herds, despite its potential for environmental surveillance and understanding indirect transmission routes.

Wastewater-based surveillance has emerged as an important tool for monitoring virus circulation in populations, capable of detecting asymptomatic carriers and identifying emerging viral subtypes, including IAV and SARS-CoV-2 [

13,

15]. The adaptation of this approach to swine production systems could provide valuable insight into the dynamics of IAV circulation, especially when combined with fecal and environmental sampling.

Although fecal-oral transmission of IAV has not been well documented in mammals, the detection of viable virus in feces and environmental samples raises concerns about its potential contribution to viral spread within herds and into the surrounding environment.

Thus, implementing a practical and effective sampling system for feces and environmental matrices may enhance early detection and surveillance of IAV lineages circulating within swine herds. Understanding the role of fecal shedding and environmental contamination in IAV ecology is key to improving biosecurity strategies, mitigating the risk of viral persistence and spread within farms, and ultimately protecting both animal and public health.

In this context, the present study aimed to: (i) assess the detection rates and viral loads in nasal, rectal, and environmental samples; (ii) isolate viable virus from feces and effluents; and (iii) perform phylogenetic and molecular characterization of the circulating IAV strains.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Farm Description

In 2023, a total of 745 samples were collected from a farrow-to-finish commercial swine farm located in Minas Gerais state, southeastern Brazil. The farm houses approximately 70,000 pigs across various production phases. Over a four-year period, the farm experienced recurrent respiratory disease outbreaks, predominantly affecting piglets in the farrowing and nursery phases, with a mortality rate of approximately 10%. Other categories such as growing and finishing pigs were also affected intermittently.

To mitigate these outbreaks, the farm initially adopted mass vaccination using a commercial inactivated pH1N1 vaccine, administered to breeding sows and weaned piglets at four-month intervals over a ten-month period. Despite this strategy, influenza outbreaks persisted, prompting the adoption of an autogenous vaccine targeting pH1N1, H3N2, and huH1 viruses, administered to sows during the final third of gestation.

2.2. Water and Effluent Management System

The farm operates a multi-stage effluent treatment system. Effluent is first homogenized in a large collection tank, and the liquid fraction proceeds to a biodigester. For reuse purposes, the effluent from the receiving pond is treated in a biological reactor with aerators and then transferred to a settler. Settled solids are returned to the reactor, while the supernatant flows into a polishing pond and then into a settling pond. The latter supplies the Wastewater Treatment Plant for Water Reuse, which includes a flotation tank, sludge removal tank, treated water receiving tank, and chemical dosing units. The final treated water is stored in impermeable membrane-lined ponds and is pumped to distribution tanks used for gravity-fed washing of pig pen floors.

The drinking water supplied to pigs is sourced from an 80-meter-deep underground reservoir and stored in stainless steel tanks. No treatment is applied prior to distribution, as the groundwater is considered suitable for direct consumption.

2.3. Sampling Procedures

During the sampling period, piglets in the farrowing and nursery phases exhibited clinical signs of respiratory disease, including coughing, sneezing, prostration, weight loss, and diarrhea. These symptomatic animals were selected for sample collection. In other categories such as replacement gilts, gestating sows, growing, and finishing pigs - where no respiratory signs were observed - animals were randomly selected for sample collection.

Nasopharyngeal secretions were collected using 15 cm synthetic swabs, while rectal swabs were obtained by gently introducing the same type of swab into the rectum. Swabs were placed in 3 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) supplemented with 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin.

Environmental samples included 500 mL of raw waste from the shed outlet, reuse water, and drinking water, collected in sterile containers, homogenized, stored in duplicates, and kept at -80°C until analysis.

2.4. Milk and Colostrum Collection

A total of 59 samples were collected, comprising 17 colostrum and 42 milk samples. Samples were obtained after administering 10 IU of oxytocin intravenously into the auricular vein using a 20-gauge, 1.5-inch needle, as previously described [

16].

In the first collection phase, 23 samples (7 colostrum and 16 milk) were collected without udder sanitization. In the second phase, 36 samples (10 colostrum and 26 milk) were collected following a rigorous udder sanitization protocol involving disposable wipes and 80% alcohol. Approximately 20 mL of each sample was manually collected from a pool of functional teats, homogenized, and stored in duplicate sterile containers at -80°C.

2.5. Viral Detection and Subtyping

Viral RNA was extracted from nasal and rectal swabs using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN), and from environmental samples using the AllPrep DNA/RNA Micro Kit (QIAGEN), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-qPCR targeting the Matrix gene was performed for universal detection of IAV [

17]. The detection limit of the IAV screening RT-qPCR assay was established by extracting RNA from a swine nasal swab positive for pH1N1, followed by serial 10-fold dilutions in nuclease-free water. Each dilution was tested in triplicate, and the lowest dilution with consistent amplification in all replicates was considered the assay's LoD. The determined LoD had a Ct value of 40, which was then adopted as the positivity threshold for all sample types in the present study.

Subtyping (H3N2, huH1, and pH1N1) was conducted using conventional RT-PCR as previously described [

18]. Positive samples from nasal, rectal, and environmental sources with lower Ct values were randomly selected for virus isolation in MDCK (CCL-34) cells.

2.6. Virus Isolation

To assess viral viability, IAV-positive samples from nasal swabs, rectal swabs, and feces were diluted 1:3 in tenfold-concentrated PBS supplemented with 1% antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin), and filtered through 0.22 µm membranes. A volume of 200 µL from each filtered sample was inoculated into 10- to 11-day-old specific-pathogen-free chicken embryonated eggs, incubated at 37°C for 72 hours. Allantoic fluid was then harvested [

19].

Subsequent passages were conducted in MDCK (CCL-34) cells, which were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 in complete Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; SIGMA) containing 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 4.5 mg/mL L-glucose, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 5% fetal bovine serum [

19].

2.7. Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis

Positive samples were subjected to full-genome amplification using multi-segment reverse transcription PCR (MS-RT-PCR), following the protocol described by [

18]. Sequencing libraries were constructed on the Illumina platform in collaboration with Instituto Butantan, according to the methodology outlined in [

21]. Raw reads were assembled using the VIPER pipeline (

https://github.com/alex-ranieri/viper). Resulting segment assemblies were subsequently validated by read mapping with BBMap and visual inspection using Geneious software. Multiple sequence alignments were performed with MAFFT v7, and phylogenetic trees were inferred using the maximum likelihood (ML) method implemented in RAxML v8.2.11 through the MEGA12 platform. Bootstrap support was estimated using 1,000 replicates. All trees were midpoint-rooted and visualized in the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL v6), with nodes arranged in descending order of bootstrap support.

To contextualize the Brazilian swine IAV sequences, separate phylogenetic trees were constructed for each gene segment (H1, H3, N1, and N2), incorporating local sequences and representative references from key clades. Reference panels were selected to ensure coverage of: (1) Brazilian swine-origin HA and NA sequences, previously classified [

4,

5], representing major clades (e.g., pH1 clades #1–4; pN1 clades #1–6; H3 clades 1990.5.1, 1990.5.2, 1990.5.3; N2 clades #1–6); (2) Human H3N2 clades 3C.2a1b.2a.2a.1 and 3C.2a1b.2a.2b, circulating in Brazil in 2022–2023, retrieved from GISAID; (3) Historic human H3 sequences from 1998, retrieved from GenBank, which shared the highest nucleotide identity with Brazilian swine H3 sequences based on BLASTn analysis; (4) Swine H3 sequences from Chile, representative of clade 1990.5.4 and its ancestral clade 1900.5; (5) Swine H3 clade 2010.1 reference sequences from U.S. swine [

23]; (6) Historic human N2 sequences, retrieved from GenBank, dated from 2001 to 2002, which shared the highest nucleotide identity with Brazilian swine N2 sequences based on BLASTn analysis;

A reduced set of 2–3 representative sequences per clade was selected based on year, geographic origin, and sequence completeness to ensure optimal tree resolution and clarity. The complete list of accession numbers and selection criteria is provided in

Supplementary Table S1.

3. Results

3.1. Viral Detection in Nasal and Rectal Swabs

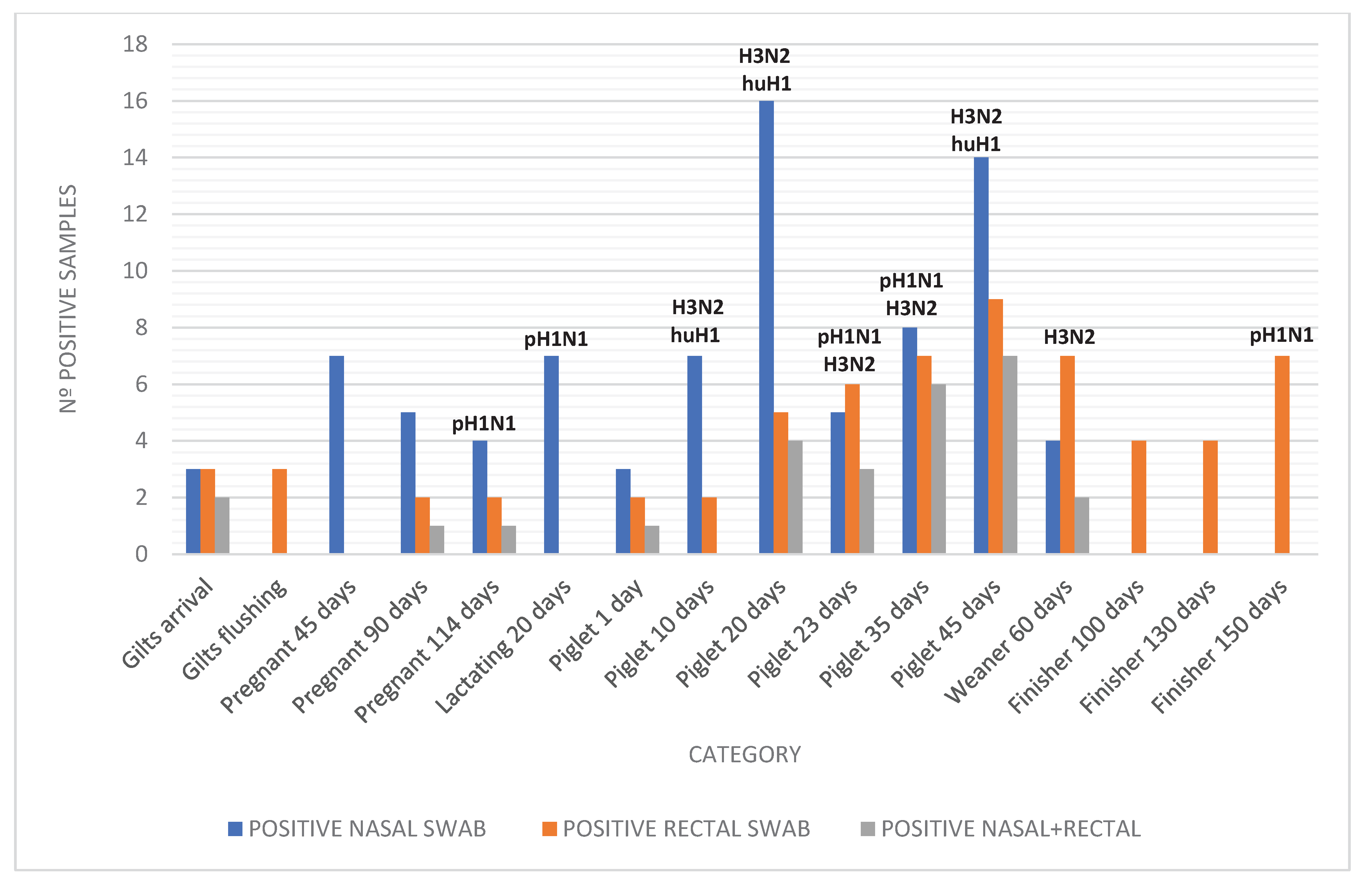

From the total of 532 samples, 28% (149/532) were positive for IAV. Of the positive animals detected across all categories, 42% (62/149) were from animals that did not show any clinical respiratory signs, particularly among the categories of incoming gilts, sows at different stages of gestation, and sows in the maternity phase. Among the maternity piglets, which showed the highest frequency of respiratory symptoms, we observed 7% (5/66) positivity in piglets only 1 day old, rising to 31% (21/68) in piglets 20 days of age.

Samples were selected based on both clinical signs and representation across the full range of production phases. In symptomatic categories (e.g., nursery and farrowing piglets), animals were chosen according to typical signs of influenza-like illness, whereas in asymptomatic groups (e.g., gilts, pregnant sows), sampling was randomized to allow detection of subclinical infections and provide comprehensive surveillance coverage.

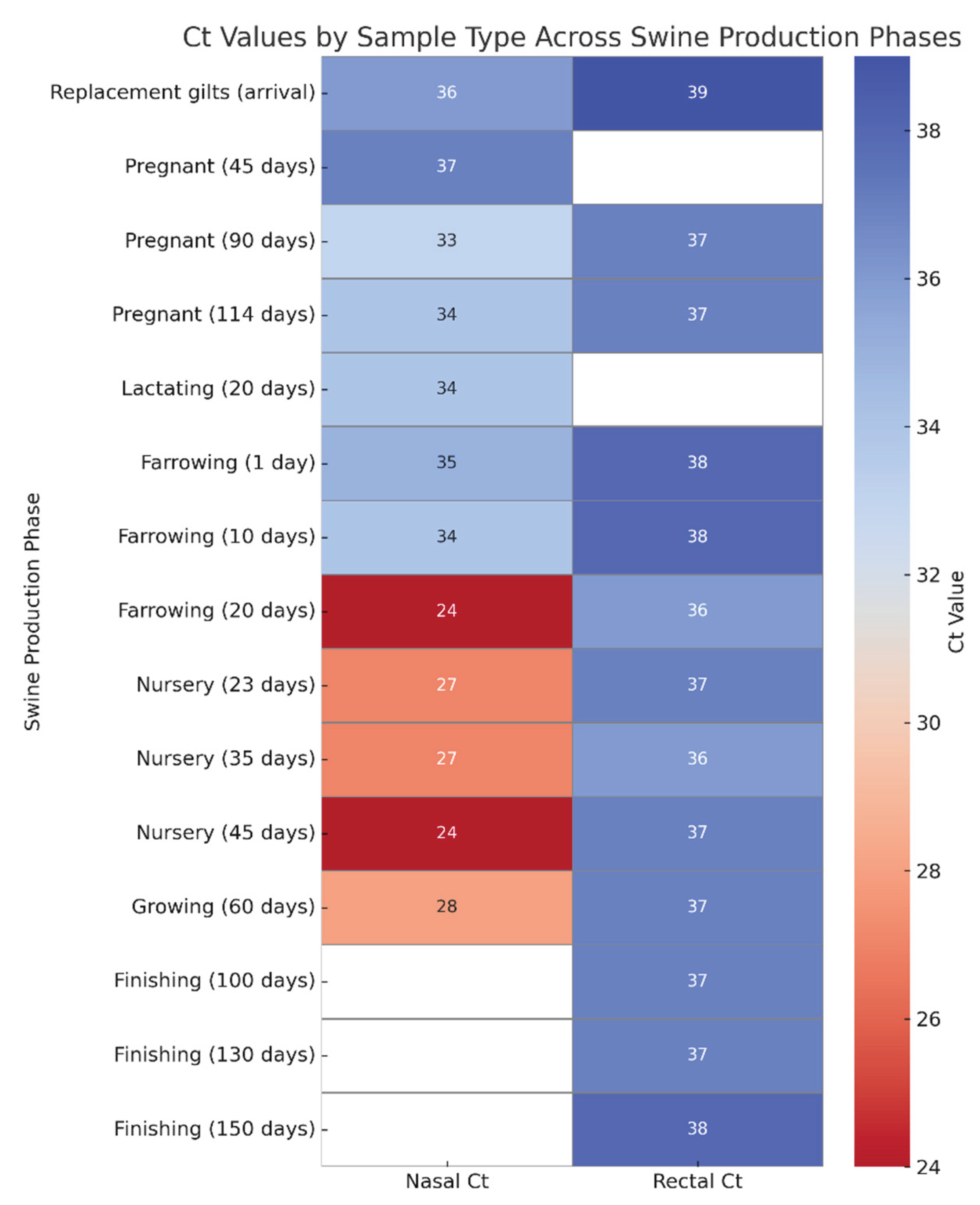

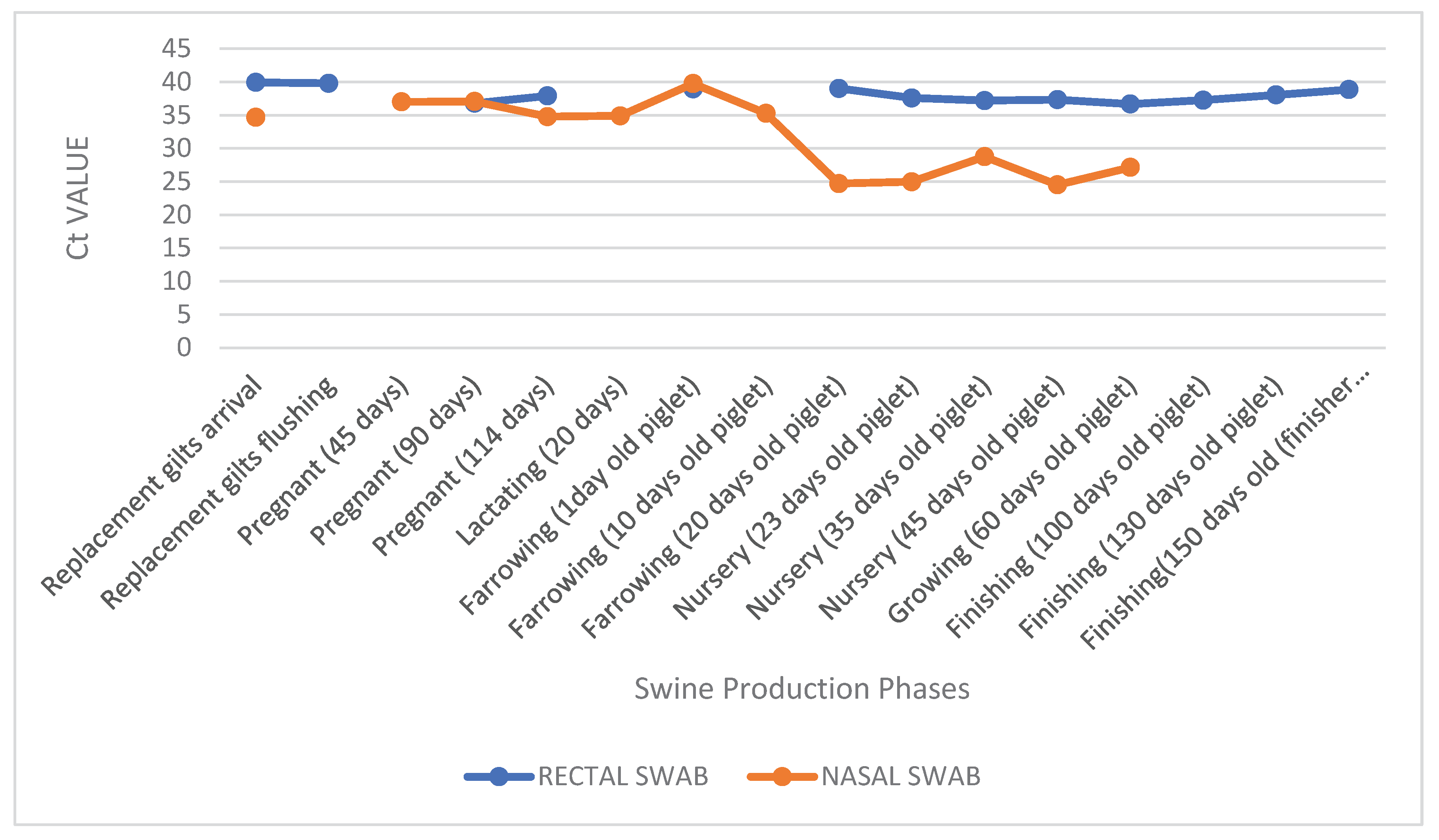

Using nasal swabs, IAV was detected at 31% (83/265), primarily in lactating sows, pregnant sows, nursery piglets, and maternity piglets. Using rectal swabs, 24% (63/267) of samples tested positive, especially among nursery piglets and finishing pigs. Of the 149 positive samples, 18% (27) were positive in both nasal and rectal swabs, particularly in nursery piglets and replacement gilts (

Table 1). In the nasal swab, 36% (30/83) of the positive animals were asymptomatic, while 64% (53/83) exhibited respiratory symptoms. In the rectal swab, 51% (32/63) of the positive animals were asymptomatic, while 49% (31/63) exhibited symptoms. We observed distinct shedding patterns between production categories: older animals in the finishing phase tested positive only in fecal samples, suggesting potential late-stage fecal excretion, whereas lactating sows and sows at 45 days of gestation showed positivity exclusively in nasal secretions (

Figure 1). These findings suggest a differential tissue tropism or temporal shedding profile between age groups.

During the different production phases, Ct values obtained from nasal and rectal swabs varied significantly. Overall, Ct values from rectal swabs were consistently high (typically ranging from 36 to 40), with minimal variation across categories, suggesting either low viral loads or intermittent shedding in feces. For instance, rectal samples from asymptomatic pigs yielded Ct values of 39 upon arrival of replacement gilts, 37 at 114 days of gestation, and 38 at 150 days in finishing pigs.

In contrast, nasal swab Ct values demonstrated greater fluctuation between phases. Notably, marked reductions were observed during the nursery phase (20 to 45 days of age), with Ct values dropping to 24 in symptomatic piglets at both 20 and 45 days. Conversely, in asymptomatic categories such as sows in gestation or lactation, nasal Ct values were higher - reaching 37 at 45 days of gestation and 34 at 114 days and during lactation.

This contrast is particularly evident when comparing paired samples from the same production stage. For example, in "Nursery (45 days)", the nasal swab presented a Ct value of 24, while the corresponding rectal swab was 37, indicating a significantly higher viral load in the upper respiratory tract compared to fecal excretion at this stage (

Figure 2). These results highlight the complexity of IAV dynamics in swine, prompting further investigation into viral subtypes and environmental detection, as explored in the following sections.

Among the nasal and rectal swab samples positive for IAV, a subset underwent subtyping to determine the circulating viral lineages. Subtyping was successful in 32 nasal swabs, revealing a predominance of H3 (41%), followed by pH1N1 (19%) and huH1 (16%). In rectal swabs, 34 samples were subtyped, with lower proportions of H3 (9%) and pH1N1 (18%), and no detection of huH1. These findings suggest potential differences in viral lineage distribution or detection efficiency between respiratory and fecal routes (

Figure 3). The distribution of subtypes detected by sample type and production category is summarized in

Figure 3. H3 was more prevalent in nursery piglets and sows, whereas pH1N1 appeared across multiple stages. huH1 was exclusively found in nasal swabs and milk samples, highlighting its possible association with human-to-swine spillover events. To better understand subtype distribution by production stage,

Table 2 summarizes the number of samples tested and subtyped by category and sample type.

3.2. Environmental Samples

A total of 13 environmental samples were collected, including raw waste from the shed outlet (n = 5), reclaimed reuse water (n = 6), and water from animal drinking troughs (n = 2). Of these, 4 samples (4/13; 30%) tested positive for IAV by RT-qPCR. Positive detections included two samples of reclaimed water, one from the finishing phase shed and another from the reservoir lagoon, as well as one raw waste sample from the maternity unit and one water sample from the drinking trough in the finishing area. These findings indicate the circulation of IAV genetic material in both effluent and drinking water systems within the farm environment.

Subtyping was performed on all positive environmental samples. One sample of reclaimed water from the reservoir lagoon tested positive for pH1N1, while another sample of reclaimed water used in the gestation barn was positive for huH1N1. Subtyping was not successful for the positive raw waste and drinking water samples, possibly due to low viral loads or RNA degradation in these matrices (

Table 3).

In addition to viral detection, pH analyses of environmental samples were conducted. The pH values ranged from 6.5 to 8.0, with reclaimed water samples tending toward a more alkaline profile compared to raw waste and drinking water (

Table 2). The near-neutral to slightly alkaline pH observed in most samples may provide conditions favorable to the environmental stability of the IAV, potentially enhancing its persistence in water sources. This physicochemical characteristic, along with repeated detection of viral RNA, highlights the potential role of water as a vehicle for indirect transmission within swine farms.

These results underscore the importance of effluent-based surveillance strategies for IAV. The detection of the huH1 subtype - a lineage of human origin - in reclaimed water also raises concern about reverse zoonotic events, supporting the hypothesis that human-origin viruses may not only infect pigs but persist in the shared farm environment. Such environmental persistence creates opportunities for inter-host transmission and viral reassortment, underscoring the need for integrated One Health approaches to monitor and mitigate influenza spread in intensive livestock settings.

3.3. Detection Rate of Milk and Colostrum Samples from Lactating Sows

Of the 59 milk and colostrum samples obtained from lactating sows in the maternity unit, 12 samples tested positive for IAV, representing a detection rate of 20%. These positive samples were distributed among 3 colostrum samples (25%) and 9 milk samples (75%) (Figure 10). Notably, 75% (9/12) of the positive samples were detected during the first collection—comprising 1 colostrum sample and 8 milk samples—while 25% (3/12) were identified during the second collection—comprising 2 colostrum and 1 milk sample.

All IAV-positive milk and colostrum samples originated from sows housed with piglets exhibiting respiratory symptoms. This association suggests that environmental contamination of the udder skin may contribute to viral presence in mammary secretions, particularly in the absence of strict hygiene protocols. Indeed, during the second collection phase, a rigorous udder sanitization procedure was implemented, coinciding with a noticeable reduction in positive samples. This supports the hypothesis that indirect contamination, rather than systemic excretion into milk, may account for the viral RNA detected.

Cycle threshold (Ct) values ranged from 37 to 39, indicating low viral loads consistent with superficial contamination or non-productive infection. Twelve milk and colostrum samples underwent subtyping, and among these, only one milk sample tested positive for the huH1 subtype. Although isolated, the detection of a human-origin IAV lineage in a lactating sow sample reinforces the need to consider the potential for reverse zoonosis, particularly in maternity sectors where close contact between humans and animals is frequent.

These findings underscore the importance of implementing and maintaining rigorous hygiene protocols in the maternity environment—not only to prevent pathogen dissemination to neonates, but also to mitigate environmental contamination that may result in indirect routes of IAV transmission within swine herds.

3.4. Isolation of Positive Samples

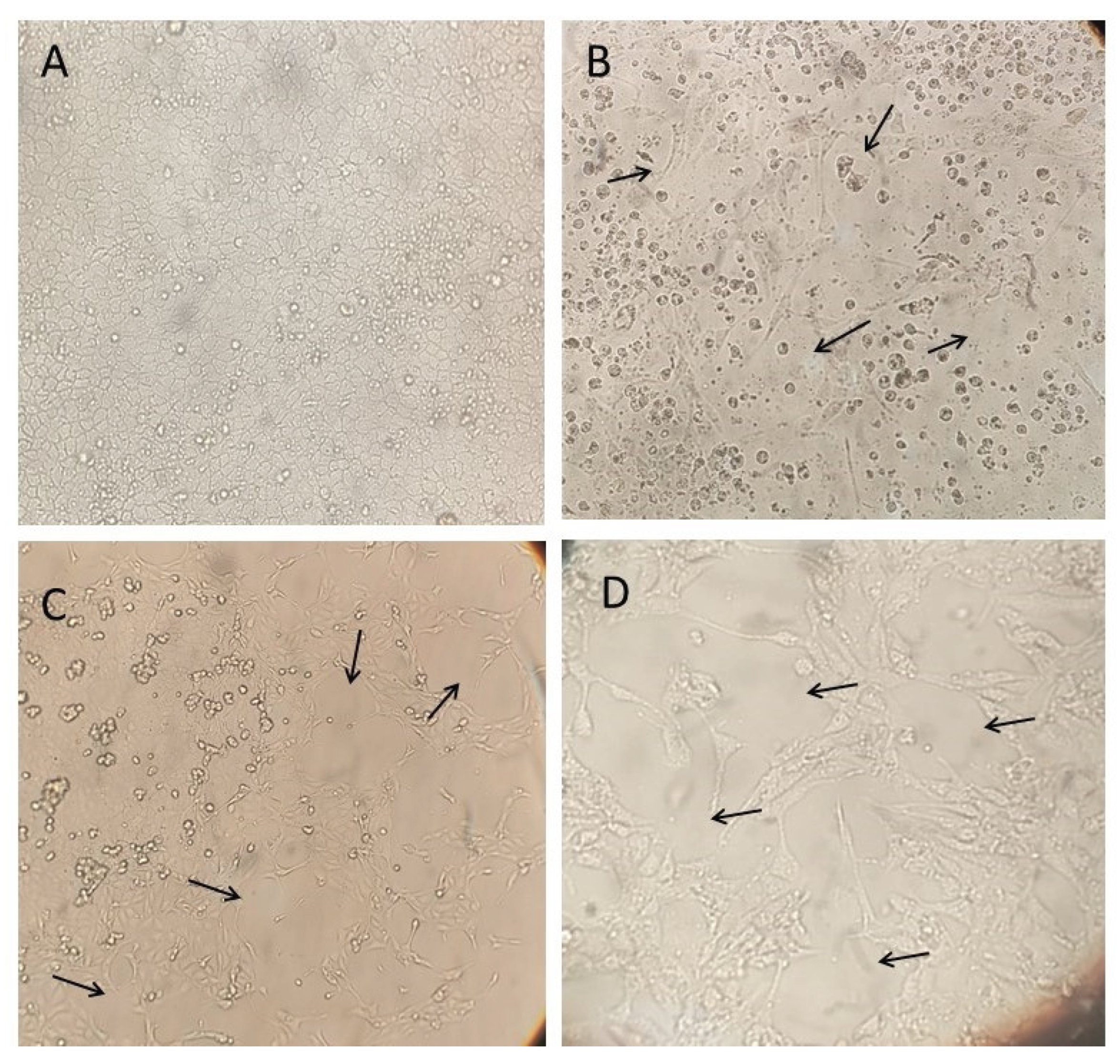

Five samples were selected for virus isolation based on their lower Ct values: three rectal swabs (from a sow at 90 days of gestation, a 35-day-old piglet, and a 130-day-old finishing pig), one nasal swab (from a 60-day-old piglet), and one environmental sample (effluent from the 150-day-old finishing barn) (

Table 4). Each sample underwent six to seven passages in MDCK (CCL-34) cells to monitor the appearance of cytopathic effects (CPE), such as cell rounding and detachment.

Among the rectal swab samples, CPE was first observed in the sample from the sow at 90 days of gestation at the fifth passage, reaching 60% by the seventh passage. In the sample from the 35-day-old piglet, CPE emerged at the fourth passage and increased to 80% by the sixth passage. The sample from the 130-day-old finishing pig showed faster progression, with CPE reaching 90% by the sixth passage (

Figure 4).

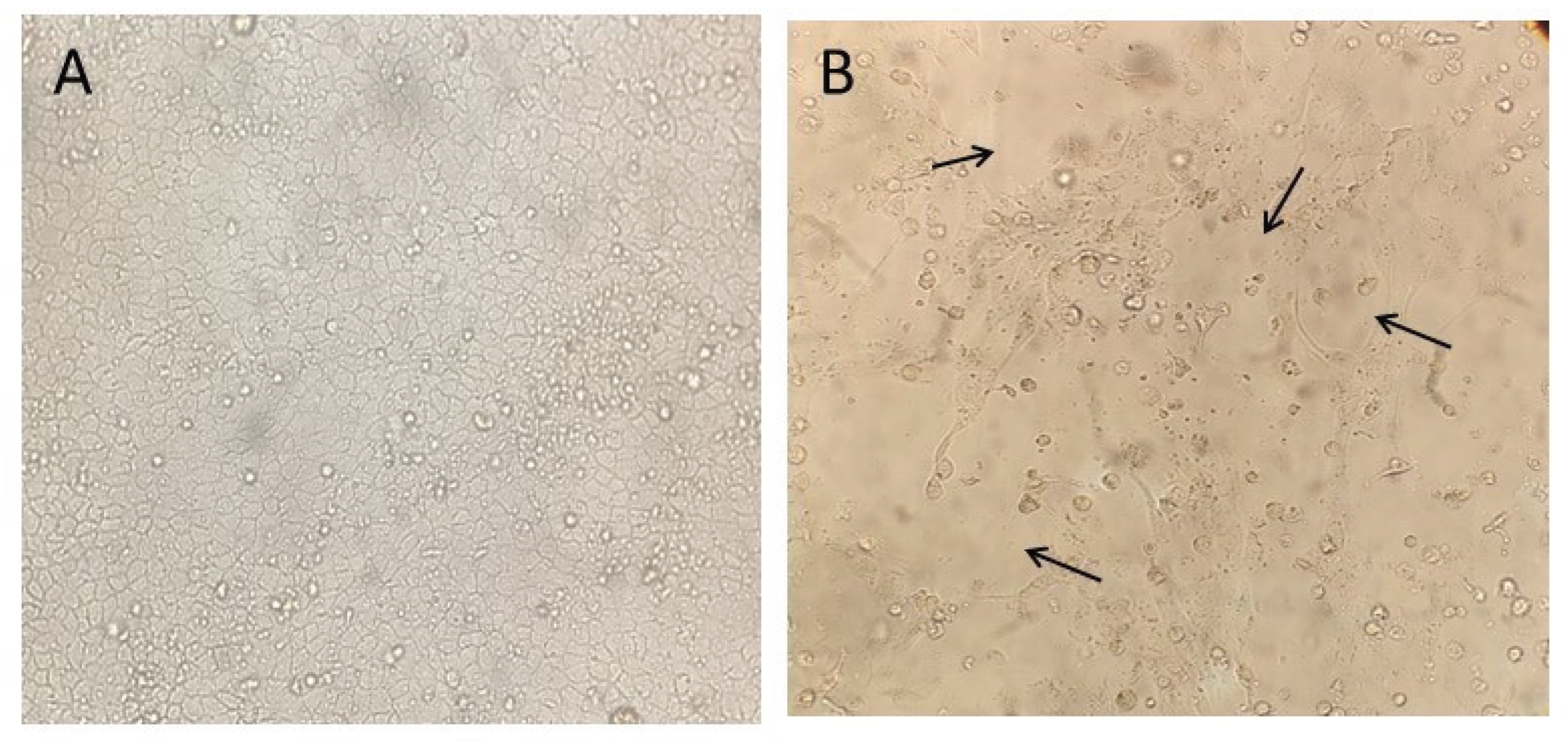

The effluent sample showed CPE beginning at the fourth passage, reaching 80% by the sixth passage (

Figure 5). The nasal swab sample from the 60-day-old piglet exhibited pronounced CPE by the fifth passage, reaching 90% by passage six. RT-qPCR confirmed the presence of IAV in all inocula post-culture.

Among these five successfully isolated samples, two underwent subtyping. The nasal swab sample from the growing phase (60 days old) was identified as H3N2, and the rectal swab sample from the 130-day-old pig was identified as pH1N1.

3.5. Sequencing and Phylogenetic Analysis

3.5.1. Sample Selection and Sequencing Yield

For whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of the HA and NA segments of IAV, a total of 75 RT-qPCR–positive clinical samples were selected based on low Ct values. These included nasal swabs (n = 54), rectal swabs (n = 16), environmental samples (n = 4), and one inoculum sample obtained from viral isolation of a nasal swab. The samples originated from sows, piglets in maternity and nursery phases, and finishing pigs.

Due to the low quality of sequencing reads for internal gene segments, only HA and NA gene sequences were analyzed. Among the 75 selected samples, 25 yielded paired HA and NA sequences, 5 yielded only HA sequences, and 7 yielded only NA sequences (

Table 5).

3.5.2. Subtype Classification

Among the 25 subtyped nucleotide sequences, 22 were identified as pH1N1 and three as H3N2. All 25 sequences were obtained from nasal swab samples. Of the five samples that yielded only HA sequences, four were classified as pH1Nx and one as H3Nx. Notably, two of the pH1Nx sequences originated from rectal swabs and three from nasal swabs, while the single H3Nx sequence was derived from a rectal swab. Among the seven samples that yielded only NA sequences, all were classified as HxN1; six were obtained from nasal swabs, and one from a maternity barn effluent sample. Although the huH1 subtype (pre-pandemic human-origin H1) was detected by RT-qPCR subtyping in some clinical and environmental samples, no corresponding HA or NA sequences were recovered, likely due to low viral loads or RNA degradation.

3.5.3. Host and Age Distribution

The nucleotide sequences obtained were predominantly recovered from nursery piglets during stages associated with overt respiratory symptoms. Specifically; among the 22 pH1N1 samples; all were nasal swabs collected from piglets aged 10 to 60 days; particularly at 20 and 45 days of age; when viral loads were highest. Similarly; the three H3N2 samples were derived from nasal swabs of piglets aged 20 and 35 days

In the H1Nx group (n = 5), three sequences were obtained from 45-day-old piglets (one nasal swab and two rectal swabs), and two from 60-day-old piglets (nasal swabs). For the HxN1 group (n = 7), six sequences were recovered from nasal swabs of 45-day-old piglets, and one from a maternity barn effluent sample (

Table 5). No full-length sequences corresponding to huH1 strains were recovered, despite their detection by RT-qPCR subtyping.

3.5.4. Phylogenetic Characterization

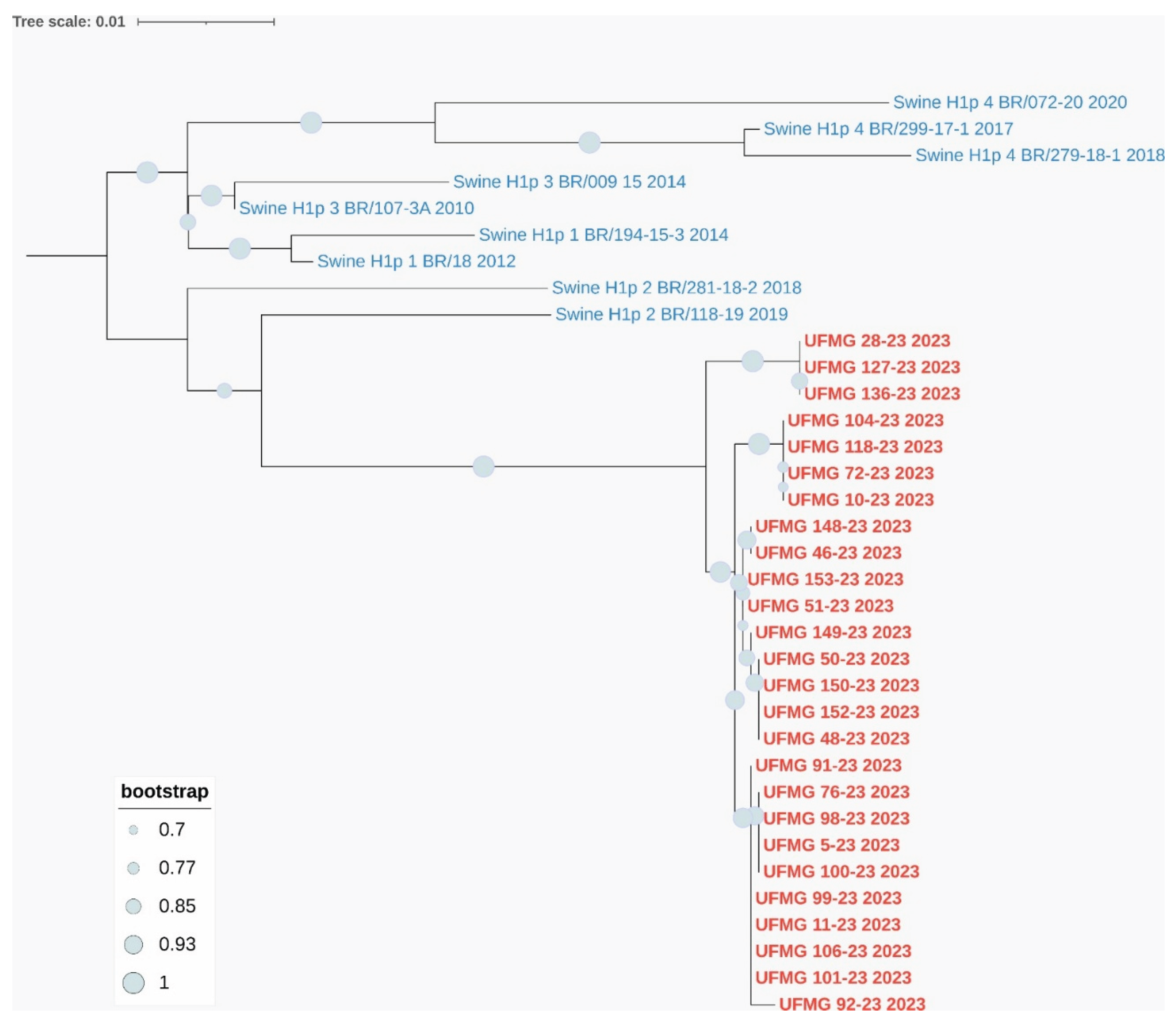

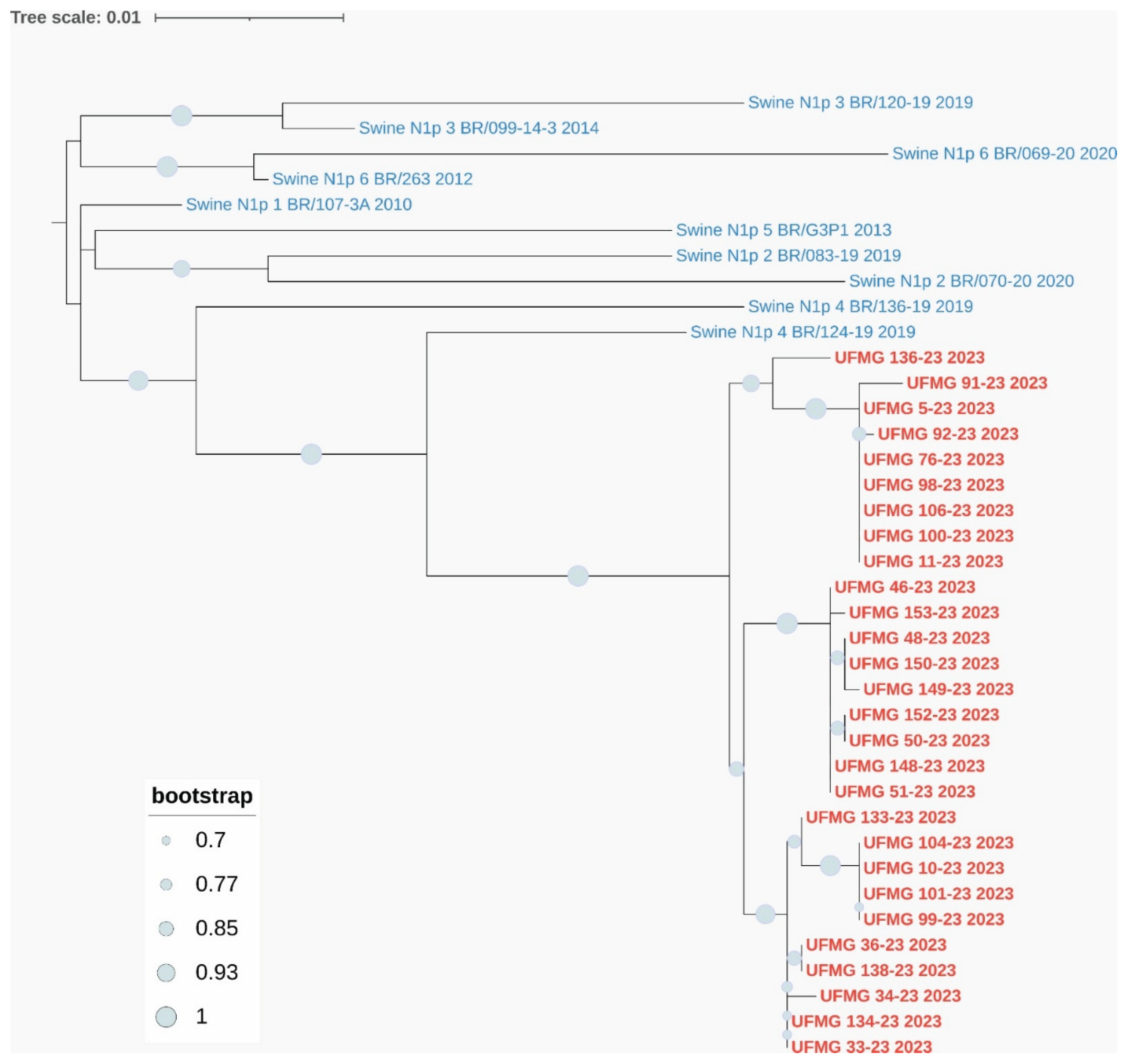

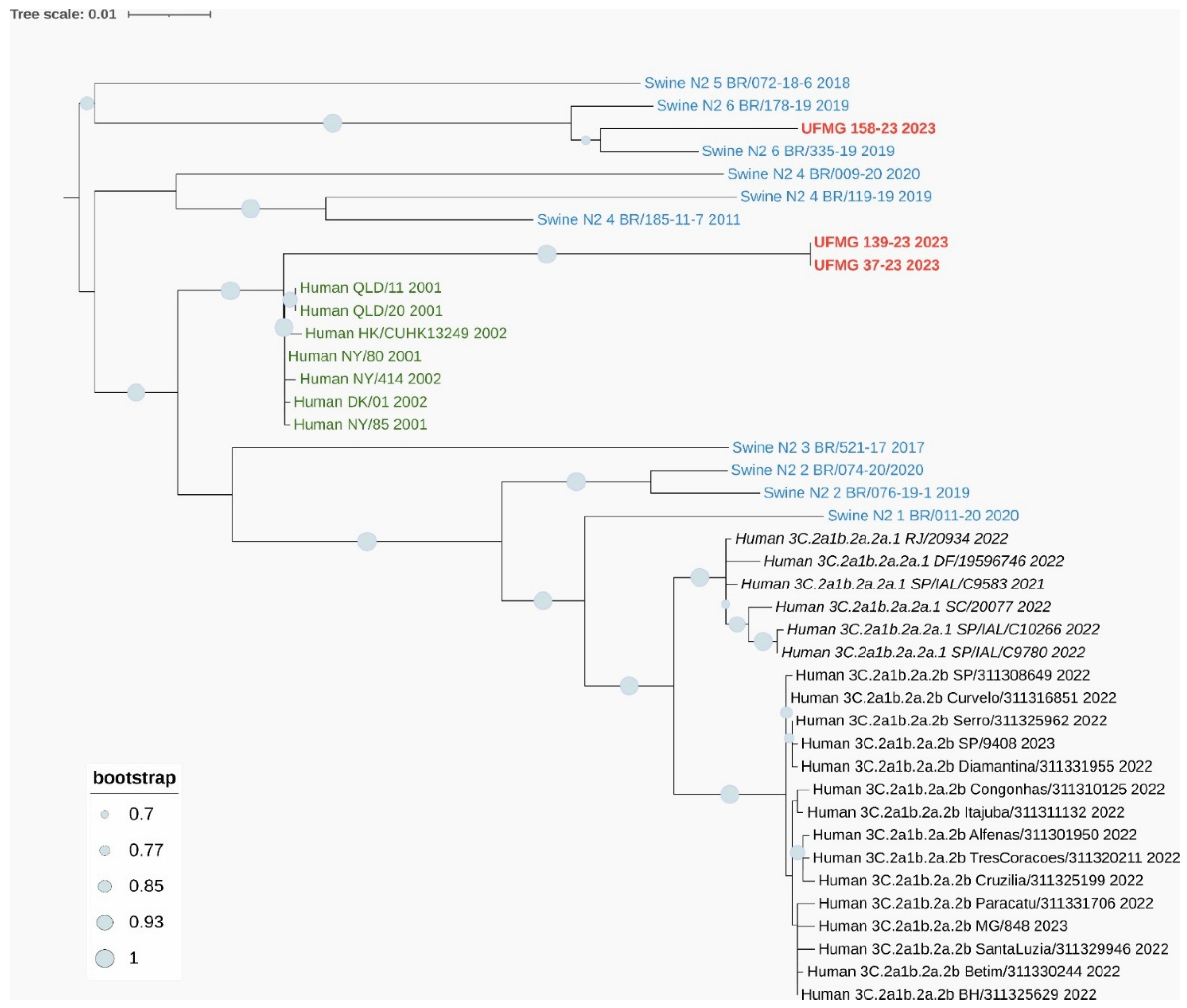

Phylogenetic analyses based on the HA and NA gene segments revealed distinct lineage clustering of the IAV strains circulating in this study. All H1 sequences were classified within pH1 clade #2, sharing high nucleotide similarity and strong bootstrap support with previously described Brazilian swine pH1N1 strains from this clade (

Figure 6A).

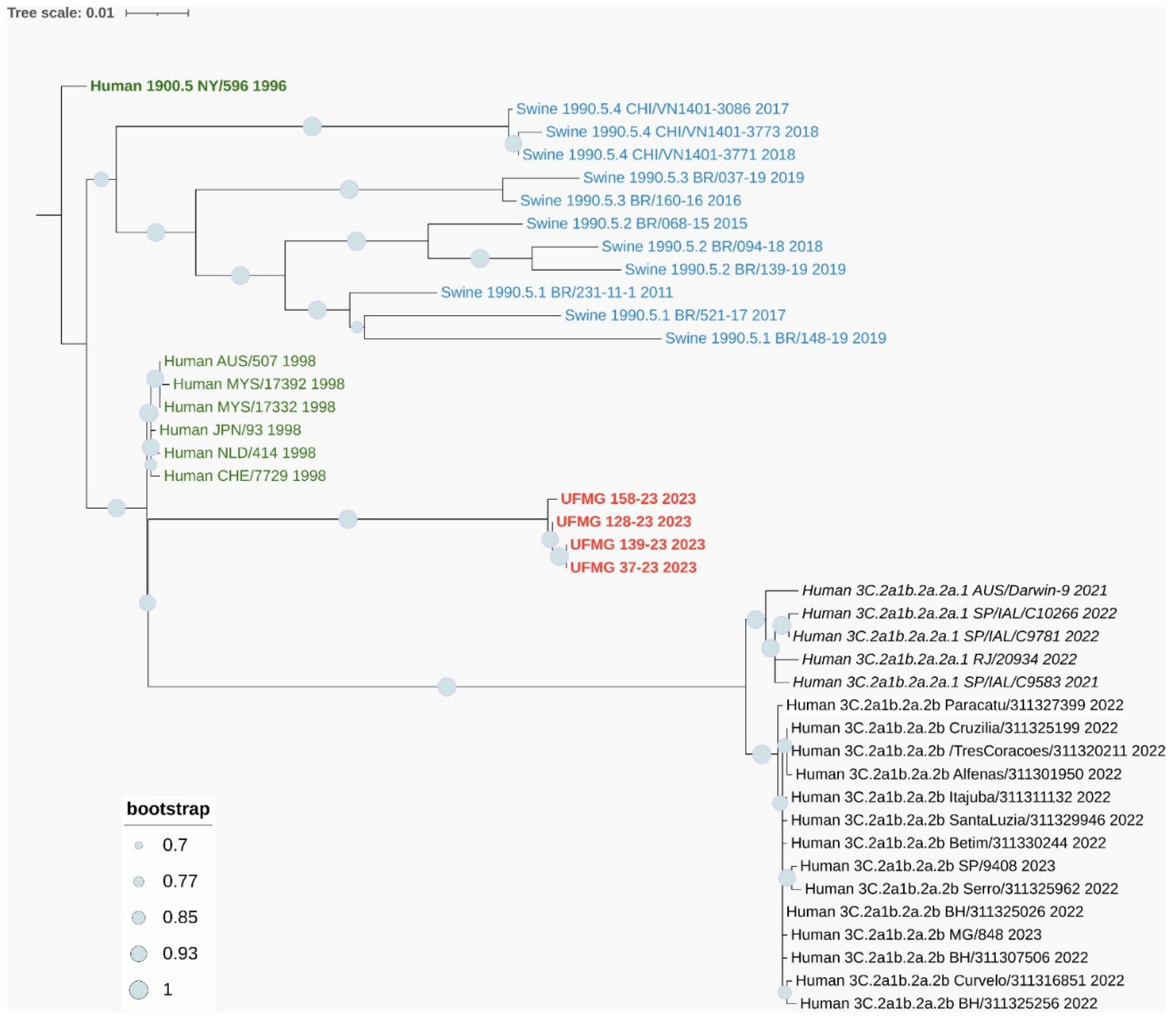

The three complete H3 sequences (UFMG_37, UFMG_128, and UFMG_139) clustered within the human-derived clade 3C.2a1b.2a.2a.1, which circulated in Brazil between 2021 and 2023. These swine sequences grouped tightly with recent human seasonal H3N2 strains, showing robust bootstrap support (≥95%), suggesting recent reverse zoonotic transmission from humans to pigs (

Figure 7A). No sequences clustered within clade 3C.2a1b.2a.2b, reinforcing the specificity of this lineage association.

This phylogenetic placement was further supported by p-distance analysis, which revealed a mean pairwise nucleotide divergence of 0.016 between the swine H3 sequences and the human clade 3C.2a1b.2a.2a.1 sequences. In contrast, divergence was higher when compared to clade 3C.2a1b.2a.2b (0.037) and swine H3 clade 1990.5.2 (0.081) (

Table 6).

Regarding the NA segments, the six N1 sequences were grouped within pN1 clade #1, consistent with co-circulating pH1 clade #2 viruses, and displayed high similarity to previously characterized Brazilian pN1 strains (

Figure 6B). The three N2 sequences clustered with human seasonal N2 viruses from 2001–2002, genetically related to pre-3C human strains that circulated globally prior to the emergence of the modern 3C clades. Notably, these N2 sequences did not group with the enzootic swine N2 clades #4 or #6 commonly found in Brazil, further supporting the human origin of the detected H3N2 strains (

Figure 7B). One of the Brazilian swine sequences (UFMG_128) grouped with high confidence alongside human N2 strains from 2002, reinforcing this inference.

p-distance analysis of the N2 segment showed a mean divergence of 0.022 between the swine N2 sequences and human N2 strains from 2001–2002, while divergence from swine clade #4 and clade #6 sequences was considerably higher (0.071 and 0.085, respectively), further supporting the phylogenetic placement.

Together, these findings highlight the continued circulation of endemic pH1N1 lineages in swine and provide strong molecular evidence for recent human-to-swine transmission events involving seasonal H3N2 viruses.

Among the sequences included in the phylogenetic analysis, two HA sequences classified as pH1Nx and one H3Nx were derived from rectal swabs, and one NA sequence classified as HxN1 was obtained from maternity barn effluent. These findings reinforce the relevance of non-respiratory matrices in genomic surveillance and support the detection of phylogenetically informative IAV genomes from fecal and environmental sources.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic analysis of HA and NA genes from pH1N1 strains detected in swine. (A) Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of H1 hemagglutinin (HA) gene sequences. Red labels indicate sequences obtained in this study; blue labels represent reference swine pH1 sequences from clades #1–4. All UFMG sequences clustered within clade pH1-#2 with strong bootstrap support (≥70%) and low intra-clade nucleotide diversity (mean p-distance = 0.010).

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic analysis of HA and NA genes from pH1N1 strains detected in swine. (A) Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of H1 hemagglutinin (HA) gene sequences. Red labels indicate sequences obtained in this study; blue labels represent reference swine pH1 sequences from clades #1–4. All UFMG sequences clustered within clade pH1-#2 with strong bootstrap support (≥70%) and low intra-clade nucleotide diversity (mean p-distance = 0.010).

Figure 6.

(B) Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of N1 neuraminidase (NA) gene sequences. All N1 sequences from this study (in red) grouped within clade pN1-1, consistent with co-circulating pH1 clade #2 viruses. Reference Brazilian swine N1 sequences from clades #1–6 (in blue) were included. High bootstrap values (≥70%) and low intra-clade distance (mean p-distance = 0.009) confirmed close genetic relatedness. All trees were inferred using RAxML with 1,000 bootstrap replicates, midpoint-rooted, and visualized using MEGA12.

Figure 6.

(B) Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of N1 neuraminidase (NA) gene sequences. All N1 sequences from this study (in red) grouped within clade pN1-1, consistent with co-circulating pH1 clade #2 viruses. Reference Brazilian swine N1 sequences from clades #1–6 (in blue) were included. High bootstrap values (≥70%) and low intra-clade distance (mean p-distance = 0.009) confirmed close genetic relatedness. All trees were inferred using RAxML with 1,000 bootstrap replicates, midpoint-rooted, and visualized using MEGA12.

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic analysis of HA and NA genes from H3N2 strains detected in swine. (A) Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of H3 hemagglutinin (HA) gene sequences. Sequences obtained in this study (in red), including one from a rectal swab (UFMG_128), clustered within the human-like clade 3C.2a1b.2a.2a.1 (in italic black), showing high similarity to human H3N2 strains circulating in Brazil between 2021 and 2023. Reference sequences from swine clades 1990.5.1 to 1990.5.4 (in blue), historic human strains from 1998 (in green), and ancestral clade 1900.5 (dark green) were included for phylogenetic context.

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic analysis of HA and NA genes from H3N2 strains detected in swine. (A) Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of H3 hemagglutinin (HA) gene sequences. Sequences obtained in this study (in red), including one from a rectal swab (UFMG_128), clustered within the human-like clade 3C.2a1b.2a.2a.1 (in italic black), showing high similarity to human H3N2 strains circulating in Brazil between 2021 and 2023. Reference sequences from swine clades 1990.5.1 to 1990.5.4 (in blue), historic human strains from 1998 (in green), and ancestral clade 1900.5 (dark green) were included for phylogenetic context.

Figure 7.

(B) Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of N2 neuraminidase (NA) gene sequences. Two distinct clusters were observed among the three sequences from this study (in red): UFMG_158 grouped with Brazilian swine clade N2-#6, while UFMG_37 and UFMG_139 clustered with human-origin strains from 2001–2002 (pre-3C clade, in dark green), suggesting historical reverse zoonotic events. Reference sequences included swine N2 clades #1–6 (in blue) and contemporary human clades 3C.2a1b.2a.2a.1 and 3C.2a1b.2a.2b (in italic and regular black, respectively). All trees were inferred using RAxML with 1,000 bootstrap replicates, midpoint-rooted, and visualized using MEGA12. Bootstrap values ≥ 70% are shown at major nodes.

Figure 7.

(B) Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of N2 neuraminidase (NA) gene sequences. Two distinct clusters were observed among the three sequences from this study (in red): UFMG_158 grouped with Brazilian swine clade N2-#6, while UFMG_37 and UFMG_139 clustered with human-origin strains from 2001–2002 (pre-3C clade, in dark green), suggesting historical reverse zoonotic events. Reference sequences included swine N2 clades #1–6 (in blue) and contemporary human clades 3C.2a1b.2a.2a.1 and 3C.2a1b.2a.2b (in italic and regular black, respectively). All trees were inferred using RAxML with 1,000 bootstrap replicates, midpoint-rooted, and visualized using MEGA12. Bootstrap values ≥ 70% are shown at major nodes.

4. Discussion

This study confirms that IAV RNA can be detected in swine feces under natural conditions, aligning with prior experimental data [

4,

8]. Notably, 42% of positive animals were asymptomatic, with multiple categories—including pregnant and lactating sows, and finishing pigs—testing positive in both nasal and rectal swabs. These findings highlight the relevance of including asymptomatic individuals in surveillance programs, as they may contribute to sustained viral circulation on farms.

Although nasal swabs yielded higher detection rates (31%) than rectal swabs (24%), Ct values were markedly higher in the latter (mean 37), reflecting lower viral loads. This supports the hypothesis that IAV replicates more efficiently in the respiratory tract. Still, sustained detection of viral RNA in feces—especially from asymptomatic animals—suggests intermittent or prolonged shedding via the gastrointestinal route. In humans, respiratory shedding peaks within four days, whereas viral RNA in feces can persist for over three weeks [

24], reinforcing this interpretation.

Ct values also varied by production phase and clinical status. Symptomatic piglets in the nursery phase (20 to 45 days old) exhibited the lowest Ct values (~24), indicating active viral replication. In contrast, asymptomatic gestating and lactating sows showed higher values (e.g., 37 at 45 days of gestation, 34 during lactation), or undetectable levels in some finishing pigs, reinforcing the correlation between nasal shedding and clinical signs.

The isolation of viable virus from feces reinforces the potential for fecal–oral transmission or environmental contamination. While replication in enterocytes remains uncertain, the presence of α2,3- and α2,6-linked sialic acid receptors in the porcine intestinal tract supports the possibility of local infection [

9]. Alternatively, swallowed virus-laden mucus may resist degradation due to protective mucins [

25], allowing viral RNA to persist in feces. The presence of IAV antigens in immune cells such as monocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages [

26,

27,

28,

29] may contribute to viral dissemination and persistence. While productive replication in these cells remains debated [

29,

30], circulating monocytes may facilitate systemic dissemination of viral RNA due to their migratory capacity. In contrast, resident macrophages may support local persistence in tissues, potentially contributing to prolonged shedding.

Detection of IAV RNA in effluent samples from asymptomatic 150-day-old pigs, with 47% positivity in feces despite negative nasal swabs, emphasizes the importance of environmental surveillance. Virus isolation from these samples confirmed viability. In the maternity barn, piglets of varying ages tested positive in both swab types, and lactating sows exhibited 77% nasal positivity. These findings indicate that pigs shed IAV through both nasal and fecal routes, contributing to environmental contamination. Detection of viral RNA in reclaimed water after biological treatment further supports this risk. Water samples showed neutral to slightly alkaline pH (6.5–8.0), a condition that may favor viral stability, whereas acidic pH reduces viability [

31]. The persistence of viral RNA in treated effluent suggests incomplete removal by standard biological treatments, a pattern also observed for SARS-CoV-2 [

32,

33]. Although viral loads were lower in reclaimed water, their presence points to residual contamination and reinforces the value of wastewater surveillance.

Detection of IAV RNA in milk and colostrum (20% positivity) from asymptomatic sows raises concerns about vertical transmission or early-life exposure. Only pH1N1 was identified, consistent with nasal detection in sows. While mammary shedding is plausible [

34], environmental contamination cannot be ruled out. These findings underscore the dual role of respiratory and fecal shedding in IAV dissemination and support the incorporation of effluent and fecal testing into surveillance to improve early detection and inform interventions.

Phylogenetic analysis revealed the co-circulation of distinct IAV lineages within the studied herd. All H1 sequences were classified within pH1 clade #2, a lineage derived from the 2009 pandemic H1N1 virus. This clade was introduced into pigs during 2009–2011 and has since become endemic in Brazilian swine [

5]. The N1 segments belonged to clade pN1 clade #4, a reassortant lineage also of pandemic origin. Although both clades descend from the same ancestral pH1N1 virus, their independent evolutionary trajectories and frequent reassortment have been documented in Brazil [

4,

5], supporting the genotypic constellation identified in our samples.

In contrast, the H3N2 sequences presented strong molecular evidence of recent reverse zoonosis. All three H3 sequences clustered within clade 3C.2a1b.2a.2a.1, a human seasonal lineage that circulated widely in Brazil between 2021 and 2023. This clade has been responsible for major human H3N2 outbreaks in multiple Brazilian states, including Minas Gerais, where the studied farm is located [

21]. The detection of this clade in pigs, with high bootstrap support and low p-distance values relative to human strains, indicates a recent introduction from humans to swine.

Interestingly, the N2 sequences grouped with H3N2 human seasonal viruses from 2001–2002, genetically related to strains such as A/Moscow/10/99–like and A/Fujian/411/2002–like, which circulated globally before the emergence of clade 3C. These N2 genes likely represent historical introductions of human-origin viruses into pigs, previously unreported in Brazil. One of our swine sequences (UFMG_128) clustered closely with human N2 strains from 2002, reinforcing this inference.

Similar events involving human-derived H3 and N2 segments have recently been reported in Mexico and the southern United States [

22,

35], but to our knowledge, this is the first documented case in Brazil of reverse zoonotic transmission of clade 3C.2a1b.2a.2a.1 into pigs. These findings highlight the increasing frequency and global distribution of such events and the critical role of local surveillance in early detection.

Importantly, phylogenetically informative sequences were also recovered from non-respiratory samples. Among the HA sequences, two pH1Nx and one H3Nx originated from rectal swabs, while one NA sequence (HxpN1) was derived from maternity barn effluent. These results reinforce the value of environmental matrices—often overlooked in surveillance—for recovering complete or partial viral genomes. The successful detection and sequencing of these samples may be explained by contamination via respiratory secretions, but also by the expression of both α2,3- and α2,6-linked sialic acid receptors in the swine intestinal tract, which could support intestinal replication or persistence of the virus [

11].

Importantly, the swine herd investigated in this study experienced a severe respiratory outbreak, characterized by intense clinical signs and an estimated mortality rate of 10%. Despite the use of autogenous vaccines, the outbreak persisted, raising concerns regarding vaccine efficacy. The genomic detection of human-origin H3N2 viruses—specifically from clade 3C.2a1b.2a.2a.1—in affected pigs suggests that the herd was likely immunologically naïve to this novel strain. This mismatch between the vaccine formulation and the circulating viruses may have contributed to the increased disease severity observed. These findings underscore the potential consequences of reverse zoonotic events in commercial herds and highlight the urgent need for continuous genomic surveillance and timely updating of swine vaccine strains.

Together, our results demonstrate the co-circulation of enzootic pH1N1 viruses, human-origin H3N2 strains, and historically introduced N2 genes in a single herd, reflecting the complex evolutionary dynamics and reassortment potential of IAVs in swine. These findings underscore the importance of integrating fecal and environmental sampling into IAV monitoring strategies, as such approaches enhance detection sensitivity, facilitate early recognition of emerging reassortants, and provide a broader picture of viral circulation within production systems.

Finally, in light of the emergence of HPAI H5N1 in Brazil, the role of pigs as potential intermediary hosts must be emphasized. A One Health framework, integrating molecular, clinical, and environmental surveillance, is essential to detect emerging IAV threats and prevent future pandemics.

5. Conclusions

This study provides novel evidence that Influenza A virus (IAV) RNA, including viable virus, can be detected in swine feces and effluent under natural conditions. These findings underscore the relevance of fecal and environmental matrices in IAV surveillance and highlight the potential for alternative transmission routes beyond the respiratory tract. The identification of IAV RNA in fecal samples from asymptomatic animals, and the successful isolation of infectious virus, suggest a possible role for gastrointestinal shedding in the persistence and spread of IAV within pig herds and into the environment.

Furthermore, the detection of human-origin H3N2 viruses (clade 3C.2a1b.2a.2a.1) in Brazilian pigs—combined with N2 segments related to pre-3C human strains from the early 2000s—provides strong molecular evidence of reverse zoonotic events and historical reassortments. The co-circulation of enzootic pH1N1 strains (clade #2) with reassorted NA segments (pN1 clade #4 and human-derived N2) within a single herd highlights the ongoing genetic evolution of swine IAVs in Brazil.

These results reinforce the need to integrate respiratory, fecal, and environmental sampling into routine surveillance programs. Such strategies will enhance early detection, improve our understanding of IAV ecology in swine populations, and help mitigate the zoonotic risks posed by emerging strains. A comprehensive One Health approach remains essential for anticipating and preventing future public and animal health threats.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.S.A.S.S., N.R.A., B.Z.C. and E.A.C.; methodology, B.S.A.S.S., N.R.A., E.A.C., V.L.V., B.C.L., A.R.J.L., J.S.T.B., B.M.M.R., B.F.S.R., A.S.D., A.L.S.F.; validation, N.R.A., B.C.L, B.S.A.S.S., B.Z.C., R.R.C., J.S.T.B., V.L.V., G.R., B.C.L.; investigation, N.R.A., B.S.A.S.S., B.Z.C., A.S.D.; resources, E.A.C., M.G., S.C.S., M.C.Q.B.E.S., L.C.J.A., M.I.M.C.G., and Z.I.P.L.; data curation, N.R.A., E.A.C., B.S.A.S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, N.R.A., E.A.C.; writing—review and editing, N.R.A., E.A.C., V.L.V., M.I.M.C.G., Z.I.P.L.; visualization, N.R.A., E.A.C., V.L.V., M.G., B.C.L., C.R.M.F., M.I.M.C.G., Z.I.P.L.; supervision, E.A.C., V.L.V.; project administration, E.A.C.; funding acquisition, E.A.C., M.G., S.C.S., M.C.Q.B.E.S., L.C.J.A., M.I.M.C.G., and Z.I.P.L.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Animal Virology Laboratory (LPVA). E.A. Costa received funding from the Minas Gerais State Research Support Foundation (FAPEMIG), grant number APQ-02856-24, and a research productivity fellowship from the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). This work was also partially funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), grant number U01 AI151698, through the United World Antiviral Research Network, and by the CeVIVAS Project, coordinated by Dr. Sandra Coccuzzo Sampaio Vessoni and funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), grant number 2021/11944-6. M. Giovanetti is supported by the PON “Ricerca e Innovazione” 2014–2020 program and the CRP-ICGEB Research Grant 2020 (project CRP/BRA20-03, contract CRP/20/03).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the institutional animal care and use committee Ethics Committee on Animal Use (CEUA) of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, under protocol number 259/2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The full genome sequences of all samples were submitted to GenBank (Accession numbers PV875989 to PV876014; PV876016 to PV876046; PV876062 to PV876068).

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the team involved in sample collection, including farm workers and veterinarians, as well as to our colleagues at the Animal Virology Laboratory, School of Veterinary Medicine, UFMG. We are also grateful to Orlando Javier Silva Rolón for his assistance during technical visits. Special thanks go to the Immunology of Viral Diseases Laboratory at the René Rachou Institute (Fiocruz Minas) for their technical support and assistance with cell culture. We also thank the Instituto Butantan and the CeVIVAS Project team for their collaboration and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Chen, L.M.; Rivailler, P.; Hossain, J.; Carney, P.; Balish, A.; Perry, I.; Davis, C.T.; Garten, R.; Shu, B.; Xu, X.; Klimov, A.; Paulson, J.C.; Cox, N.J.; Swenson, S.; Stevens, J.; Vincent, A.; Gramer, M.; Donis, R.O. Receptor specificity of subtype H1 influenza A viruses isolated from swine and humans in the United States. Virology 2011, 412, 401-410. [CrossRef]

- Crisci, E.; Mussá, T.; Fraile, L.; Montoya, M. Review: influenza virus in pigs. Mol Immunol 2013, 55, 200-211. [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.; Zhu, X.; Li, Y.; Shi, M.; Zhang, J.; Bourgeois, M.; Yang, H.; Chen, X.; Recuenco, S.; Gomez, J.; Chen, L.M.; Johnson, A.; Tao, Y.; Dreyfus, C.; Yu, W.; McBride, R.; Carney, P.J.; Gilbert, A.T.; Chang, J.; Guo, Z.; Davis, C.T.; Paulson, J.C.; Stevens, J.; Rupprecht, C.E.; Holmes, E.C.; Wilson, I.A.; Donis, R.O. New world bats harbor diverse influenza A viruses. PLoS Pathog 2013, 9, e1003657. [CrossRef]

- Tochetto, C.; Junqueira, D.M.; Anderson, T.K.; Gava, D.; Haach, V.; Cantão, M.E.; Vincent Baker, A.L.; Schaefer, R. Introductions of Human-Origin Seasonal H3N2, H1N2 and Pre-2009 H1N1 Influenza Viruses to Swine in Brazil. Viruses 2023, 15, 576. [CrossRef]

- Junqueira, D.M.; Tochetto, C.; Anderson, T.K.; Gava, D.; Haach, V.; Cantão, M.E.; Baker, A.L.V.; Schaefer, R. Human-to-swine introductions and onward transmission of 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza viruses in Brazil. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1243567. [CrossRef]

- De Vleeschauwer, A.; Atanasova, K.; Van Borm, S.; van den Berg, T.; Rasmussen, T.B.; Uttenthal, A.; Van Reeth, K. Comparative pathogenesis of an avian H5N2 and a swine H1N1 influenza virus in pigs. PLoS One 2009, 4, e6662. [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.J.; Moon, S.J.; Kuak, E.Y.; Yoo, H.M.; Kim, C.K.; Chey, M.J.; Shin, B.M. Frequent detection of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 virus in stools of hospitalized patients. J Clin Microbiol 2010, 48, 2314-2315. [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.C.; Lee, N.; Chan, P.K.; To, K.F.; Wong, R.Y.; Ho, W.S.; Ngai, K.L.; Sung, J.J. Seasonal influenza A virus in feces of hospitalized adults. Emerg Infect Dis 2011 , 17, 2038-2042. [CrossRef]

- Kurmi, B.; Murugkar, H.V.; Nagarajan, S.; Tosh, C.; Dubey, S.C.; Kumar, M. Survivability of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 Virus in Poultry Faeces at Different Temperatures. Indian J Virol 2013, 24, 272-7. [CrossRef]

- Kawaoka, Y.; Bordwell, E.; Webster, R.G. Intestinal replication of influenza A viruses in two mammalian species. Brief report. Arch Virol 1987, 93. 303-308. [CrossRef]

- Nelli, R.K.; Kuchipudi, S.V.; White, G.A.; Perez, B.B.; Dunham, S.P.; Chang, K.C. Comparative distribution of human and avian type sialic acid influenza receptors in the pig. BMC Vet Res 2010, 6, 4. [CrossRef]

- Turlewicz-Podbielska, H.; Augustyniak, A.; Pomorska-Mól, M. Novel Porcine Circoviruses in View of Lessons Learned from Porcine Circovirus Type 2-Epidemiology and Threat to Pigs and Other Species. Viruses 2022, 14, 261. [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, M.K.; Duong, D.; Bakker, K.M.; Ammerman, M.; Mortenson, L.; Hughes, B.; Arts, P.; Lauring, A.S.; Fitzsimmons, W.J.; Bendall, E.; Hwang, C.E.; Martin, E.T.; White, B.J.; Boehm, A.B.; Wigginton, K.R. Wastewater-Based Detection of Two Influenza Outbreaks. Environ Sci Techno. Lett 2022, 9, 687-692. [CrossRef]

- Viancelli, A.; Garcia, L.A.; Kunz, A.; Steinmetz, R.; Esteves, P.A.; Barardi, C.R. Detection of circoviruses and porcine adenoviruses in water samples collected from swine manure treatment systems. Res Vet Sci 2012, 93, 538-43. [CrossRef]

- Mercier, E.; D'Aoust, P.M.; Thakali, O.; Hegazy, N.; Jia, J.J.; Zhang, Z.; Eid, W.; Plaza-Diaz, J.; Kabir, M.P.; Fang, W.; Cowan, A.; Stephenson, S.E.; Pisharody, L.; MacKenzie, A.E.; Graber, T.E.; Wan, S.; Delatolla, R. Municipal and neighbourhood level wastewater surveillance and subtyping of an influenza virus outbreak. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 15777. [CrossRef]

- Martins, T.D.D.; Costa, N.A.; da Silva, J.H.V.; Brasil, L.H.A.; Valença, R.M.B.; Souza, N.M. Produção e composição do leite de porcas híbridas mantidas em ambiente quente. Ciência Rural, 2007, 37, 1079-1083. [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.S.; Curran, M.D. Simultaneous molecular detection and confirmation of influenza AH5, with internal control. Methods Mol Biol 2011, 665, 161-181. [CrossRef]

- Fraiha, A.L.S.; Matos, A.C.D.; Cunha, J.L.R.; Santos, B.S.Á.D.S.; Peixoto, M.V.C.; Oliveira, A.G.G.; Galinari, G.C.F.; Nascimento, H.I.J.; Guedes, M.I.M.C.; Machado, A.M.V.; Costa, E.A.; Lobato, Z.I.P. Swine influenza A virus subtypes circulating in Brazilian commercial pig herds from 2012 to 2019. Braz J Microbiol 2021, 52, 2421-2430. [CrossRef]

- Eisfeld, A.J.; Neumann, G.; Kawaoka, Y. Influenza A virus isolation, culture and identification. Nat Protoc 2014, 9, 2663-2681. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Donnelly, M.E.; Scholes, D.T.; St George, K.; Hatta, M.; Kawaoka, Y.; Wentworth, D.E. Single-reaction genomic amplification accelerates sequencing and vaccine production for classical and Swine origin human influenza a viruses. J Virol 2009, 83, 10309-10313. [CrossRef]

- Brcko, I.C.; de Souza, V.C.; Ribeiro, G.; Lima, A.R.J.; Martins, A.J.; Barros, C.R.D.S.; de Carvalho, E.; Pereira, J.S.; de Lima. L.P.O.; Viala, V.L.; Kashima, S.; de La Roque, D.G.L.; Santos, E.V.; Rodrigues, E.S.; Nunes, J.A.; Torres, L.S.; Caldeira, L.A.V.; Palmieri, M.; Medina, C.G.; de Arruda, R.A.; Lopes, R.B.; Sobrinho, G.R.; Jorge, D.M.M.; Arruda, E.; Mendes, E.C.B.D.S.; Santos, H.O.; de Mello, A.L.E.S.; Pereira, F.M.; Gómez, M.K.A.; Nardy, V.B.; Henrique, B.; Vieira, L.L.; Roll, M.M.; de Oliveira, E.C.; Almeida, J.D.P.C.; da Silva, S.F.; Borges, G.A.L.; Furtado, K.C.L.; da Costa, P.M.S.S.B.; Chagas, S.M.D.S.; Kallás, E.G.; Larh, D.; Giovanetti, M.; Nanev Slavov, S.; Coccuzzo, S.S.; Elias, M.C. Comprehensive molecular epidemiology of influenza viruses in Brazil: insights from a nationwide analysis. Virus Evol 2024, 11, veae102. [CrossRef]

- Zeller, M.A.; Carnevale, de A.M.D.; Ciacci Zanella, G.; Souza, C.K.; Anderson, T.K.; Baker, A.L.; Gauger, P.C. Reverse zoonosis of the 2022-2023 human seasonal H3N2 detected in swine. Npj Viruses 2024, 2, 27. [CrossRef]

- Pow ell, J.D.; Abente, E.J.; Chang, J.; Souza, C.K.; Rajao, D.S.; Anderson, T.K.; Zeller, M.A.; Gauger, P.C.; Lewis, N.S.; Vincent, A.L. Characterization of contemporary 2010.1 H3N2 swine influenza A viruses circulating in United States pigs. Virology 2021, 553, 94-101. [CrossRef]

- Hirose, R.; Daidoji, T.; Naito, Y.; Watanabe, Y.; Arai, Y.; Oda, T.; Konishi, H.; Yamawaki, M.; Itoh, Y.; Nakaya, T. Long-term detection of seasonal influenza RNA in faeces and intestine. Clin Microbiol Infect 2016, 22, 813.e1-813.e7. [CrossRef]

- Hirose, R.; Nakaya, T.; Naito, Y.; Daidoji ,T.; Watanabe, Y.; Yasuda, H.; Konishi, H.; Itoh, Y. Mechanism of Human Influenza Virus RNA Persistence and Virion Survival in Feces: Mucus Protects Virions From Acid and Digestive Juices. J Infect Dis 2017, 216, 105-109. [CrossRef]

- Perrone, L.A.; Plowden, J.K.; García-Sastre, A.; Katz, J.M.; Tumpey, T.M. H5N1 and 1918 pandemic influenza virus infection results in early and excessive infiltration of macrophages and neutrophils in the lungs of mice. PLoS Pathog 2008, 4, e1000115. [CrossRef]

- Sakabe, S.; Iwatsuki-Horimoto, K.; Takano, R.; Nidom, C.A.; Le, M.T.Q.; Nagamura-Inoue, T.; Horimoto, T.; Yamashita, N.; Kawaoka, Y. Cytokine production by primary human macrophages infected with highly pathogenic H5N1 or pandemic H1N1 2009 influenza viruses. J Gen Virol 2011, 92, 1428-1434. [CrossRef]

- Hoeve, M.A.; Nash, A.A.; Jackson, D.; Randall, R.E.; Dransfield, I. Influenza virus A infection of human monocyte and macrophage subpopulations reveals increased susceptibility associated with cell differentiation. PLoS One 2012, 7, e29443. [CrossRef]

- Cline, T.D.; Beck, D.; Bianchini, E. Influenza virus replication in macrophages: balancing protection and pathogenesis. J Gen Virol 2017, 98, 2401-2412. [CrossRef]

- Londrigan, S.L.; Short, K.R.; Ma, J.; Gillespie, L.; Rockman, S.P.; Brooks, A.G.; Reading, P.C. Infection of Mouse Macrophages by Seasonal Influenza Viruses Can Be Restricted at the Level of Virus Entry and at a Late Stage in the Virus Life Cycle. J Virol 2015, 89, 12319-12329. [CrossRef]

- Ramey, A.M.; Reeves, A.B.; Drexler, J.Z.; Ackerman, J.T.; de La Cruz, S.; Lang, A.S.; Leyson, C.; Link, P.; Prosser, D.J.; Robertson, G.J.; Wight, J.; Youk, S.; Spackman, E.; Pantin-Jackwood, M.; Poulson, R.L.; Stallknecht, D.E. Influenza A viruses remain infectious for more than seven months in northern wetlands of North America. Proc Biol Sci. 2020 Sep 9;287(1934):20201680. R. Imoldi, sara giordana et al. Presence and infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 virus in wastewaters and rivers. Sci Total Environ 2020, 744, 140911. [CrossRef]

- Baldovin, T.; Amoruso, I.; Fonzo, M.; Buja, A.; Baldo, V.; Cocchio, S.; Bertoncello, C. SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection and persistence in wastewater samples: An experimental network for COVID-19 environmental surveillance in Padua, Veneto Region (NE Italy). Sci Total Environ 2021, 760,143329. [CrossRef]

- Rimoldi, S.G.; Stefani, F.; Gigantiello, A.; Polesello, S.; Comandatore, F.; Mileto, D.; Maresca, M.; Longobardi, C.; Mancon, A.; Romeri, F.; Pagani, C.; Cappelli, F.; Roscioli, C.; Moja, L.; Gismondo, M.R.; Salerno, F. Presence and infectivity of SARS-CoV-2 virus in wastewaters and rivers. Sci Total Environ 2020, 744, 140911. [CrossRef]

- Paquette, S.G.; Banner, D.; Huang, S.S.; Almansa, R.; Leon, A.; Xu, L.; Bartoszko, J.; Kelvin, D.J.; Kelvin, A.A. Influenza Transmission in the Mother-Infant Dyad Leads to Severe Disease, Mammary Gland Infection, and Pathogenesis by Regulating Host Responses. PLoS Pathog 2015, 11, e1005173. [CrossRef]

- Moraes, D.C.A.; Zeller, M.A.; Thomas, M.N.; Anderson, T.K.; Linhares, D.C.L.; Baker, A.L.; Silva, G.S.; Gauger, P.C. Influenza a Virus Detection at the Human-Swine Interface in US Midwest Swine Farms. Viruses 2024, 16, 1921. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Heatmap of Influenza A virus Ct values in nasal and rectal swabs across swine production phases. Ct values were obtained by RT-qPCR from nasopharyngeal (left column) and rectal (right column) swabs collected at different production stages. Lower Ct values (indicative of higher viral load) are shown in dark red, while higher Ct values (suggestive of lower viral load or late infection) are represented in blue. Nasal swabs generally exhibited lower Ct values, particularly during the nursery phase (20–45 days of age), whereas rectal swabs showed higher Ct values across most categories, indicating lower viral loads. This visual comparison emphasizes the differential viral shedding patterns in respiratory versus enteric routes.

Figure 1.

Heatmap of Influenza A virus Ct values in nasal and rectal swabs across swine production phases. Ct values were obtained by RT-qPCR from nasopharyngeal (left column) and rectal (right column) swabs collected at different production stages. Lower Ct values (indicative of higher viral load) are shown in dark red, while higher Ct values (suggestive of lower viral load or late infection) are represented in blue. Nasal swabs generally exhibited lower Ct values, particularly during the nursery phase (20–45 days of age), whereas rectal swabs showed higher Ct values across most categories, indicating lower viral loads. This visual comparison emphasizes the differential viral shedding patterns in respiratory versus enteric routes.

Figure 2.

Cycle threshold (Ct) values obtained by RT-qPCR for IAV detection in nasal and rectal swabs collected from pigs at different stages of production. Each bar represents the mean Ct value observed in a specific production phase. Nasal samples showed lower Ct values during the nursery period (20–45 days of age), particularly in symptomatic piglets, indicating higher viral loads. In contrast, rectal samples exhibited consistently higher Ct values across all phases, including asymptomatic animals, suggesting lower levels of fecal viral shedding. These findings highlight differences in viral load dynamics between respiratory and enteric excretion routes.

Figure 2.

Cycle threshold (Ct) values obtained by RT-qPCR for IAV detection in nasal and rectal swabs collected from pigs at different stages of production. Each bar represents the mean Ct value observed in a specific production phase. Nasal samples showed lower Ct values during the nursery period (20–45 days of age), particularly in symptomatic piglets, indicating higher viral loads. In contrast, rectal samples exhibited consistently higher Ct values across all phases, including asymptomatic animals, suggesting lower levels of fecal viral shedding. These findings highlight differences in viral load dynamics between respiratory and enteric excretion routes.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Influenza A virus subtypes detected in nasal and rectal swabs from pigs in different production phases. The figure shows the frequency of detection for H3, pH1N1, and huH1 across categories, emphasizing the higher detection of H3 in piglets and sows and the absence of huH1 in fecal samples.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Influenza A virus subtypes detected in nasal and rectal swabs from pigs in different production phases. The figure shows the frequency of detection for H3, pH1N1, and huH1 across categories, emphasizing the higher detection of H3 in piglets and sows and the absence of huH1 in fecal samples.

Figure 4.

Cytopathic effects (CPE) observed in MDCK (CCL-34) cell cultures after inoculation with Influenza A virus–positive samples from swine rectal swabs. MDCK CCL34 cells (Madin-Darby canine kidney). Black arrows highlight the cytopathic effects caused by influenza A, observed 72 hours after inoculation. A) Cell control inoculated with DMEM; B) 7th inoculum of the rectal swab sample from a sow at 90 days of gestation; C) 6th inoculum of the rectal swab sample from a 35-day-old piglet; D) 6th inoculum of the rectal swab sample from a 130-day-old finishing pig. Magnification: 500x.

Figure 4.

Cytopathic effects (CPE) observed in MDCK (CCL-34) cell cultures after inoculation with Influenza A virus–positive samples from swine rectal swabs. MDCK CCL34 cells (Madin-Darby canine kidney). Black arrows highlight the cytopathic effects caused by influenza A, observed 72 hours after inoculation. A) Cell control inoculated with DMEM; B) 7th inoculum of the rectal swab sample from a sow at 90 days of gestation; C) 6th inoculum of the rectal swab sample from a 35-day-old piglet; D) 6th inoculum of the rectal swab sample from a 130-day-old finishing pig. Magnification: 500x.

Figure 5.

Cytopathic effects (CPE) observed in MDCK (CCL-34) cell cultures after inoculation with Influenza A virus–positive samples from swine and environmental sources. Black arrows highlight the cytopathic effects caused by viral influenza infection. A) Cell control inoculated with DMEM; B) 6th inoculum of the effluent sample from the 150-day-old finishing barn. Magnification: 500x.

Figure 5.

Cytopathic effects (CPE) observed in MDCK (CCL-34) cell cultures after inoculation with Influenza A virus–positive samples from swine and environmental sources. Black arrows highlight the cytopathic effects caused by viral influenza infection. A) Cell control inoculated with DMEM; B) 6th inoculum of the effluent sample from the 150-day-old finishing barn. Magnification: 500x.

Table 1.

Distribution of influenza A virus–positive samples detected by RT-qPCR in nasal and rectal swabs across swine production categories. The table shows the number and percentage of positive samples per category, as well as the number of animals with simultaneous detection in both nasal and rectal swabs. Distinct shedding patterns were observed between age groups, with nursery piglets and replacement gilts exhibiting higher rates of dual-route detection.

Table 1.

Distribution of influenza A virus–positive samples detected by RT-qPCR in nasal and rectal swabs across swine production categories. The table shows the number and percentage of positive samples per category, as well as the number of animals with simultaneous detection in both nasal and rectal swabs. Distinct shedding patterns were observed between age groups, with nursery piglets and replacement gilts exhibiting higher rates of dual-route detection.

| Swine production phases |

Positive nasal swabs |

Positive rectal swab |

Positive nasal + rectal |

| Replacement gilts arrival |

3/10 (30%) |

3/10 (30%) |

2/6 (33%) |

| Replacement gilts flushing |

0 (0%) |

3/10 (30%) |

0(0%) |

| Pregnant (45 days) |

7/10 (70%) |

0 (0%) |

0(0%) |

| Pregnant (90 days) |

5/10 (50%) |

2/10 (20%) |

1/7 (14%) |

| Pregnant (114 days) |

4/10 (40%) |

2/10 (20%) |

1/6 (17%) |

| Lactating (20 days) |

7/9 (77%) |

0(0%) |

0(0%) |

| Farrowing (1day old piglet) |

3/33 (9%) |

2/33 (6%) |

1/5 (20%) |

| Farrowing (10 days old piglet) |

7/33 (21%) |

2/33 (6%) |

0(0%) |

| Farrowing (20 days old piglet) |

16/34 (47%) |

5/34 (15%) |

4/21 (19%) |

| Nursery (23 days old piglet) |

5/10 (50%) |

6/10 (60%) |

3/11 (27%) |

| Nursery (35 days old piglet) |

8/17 (47%) |

7/17 (41%) |

6/15 (40%) |

| Nursery (45 days old piglet) |

14/26 (54%) |

9/26 (35%) |

7/23 (30%) |

| Growing (60 days old piglet) |

4/19 (21%) |

7/19 (37%) |

2/11 (18%) |

| Finishing (100 days old piglet) |

0(0%) |

4/10 (40%) |

0(0%) |

| Finishing (130 days old piglet) |

0(0%) |

4/ 10 (40%) |

0(0%) |

| Finishing(150 days old (finisher piglet) |

0(0%) |

7/15 (47%) |

0(0%) |

| Total |

83 |

66 |

27 |

Table 2.

Distribution of positive samples for the influenza A virus subtypes pH1N1, H3N2, and huH1 detected by RT-PCR across different animal categories. The table presents the number of positive samples for each subtype and the total number of samples tested per category, allowing a comparative analysis of subtype prevalence in swine production stages.

Table 2.

Distribution of positive samples for the influenza A virus subtypes pH1N1, H3N2, and huH1 detected by RT-PCR across different animal categories. The table presents the number of positive samples for each subtype and the total number of samples tested per category, allowing a comparative analysis of subtype prevalence in swine production stages.

| Swine production phases |

pH1N1 |

H3N2 |

huH1 |

| Replacement gilts arrival |

0/4 (0%) |

0/4 (0%) |

0/4 (0%) |

| Replacement gilts flushing |

0/2(0%) |

0/2 (0%) |

0/2(0%) |

| Pregnant (45 days) |

0/0 (0%) |

0/0 (0%) |

0/0(0%) |

| Pregnant (90 days) |

0/4 (0%) |

0/4 (0%) |

0/4 (0%) |

| Pregnant (114 days) |

2/4 (50%) |

0/4 (0%) |

0/4 (0%) |

| Farrowing (2 old days) |

1/2 (50%) |

0/2(0%) |

0/2(0%) |

| Farrowing (1day old piglet) |

0/3 (0%) |

0/3 (0%) |

0/3 (0%) |

| Farrowing (10 days old piglet) |

0/4 (0%) |

1/4 (25%) |

1/4(25%) |

| Farrowing (20 days old piglet) |

0/16 (0%) |

8/16 (50%) |

1/16 (6%) |

| Nursery (23 days old piglet) |

1/6 (17%) |

4/6 (67%) |

0/6 (0%) |

| Nursery (35 days old piglet) |

1/6 (17%) |

1/6 (17%) |

0/6 (0%) |

| Nursery (45 days old piglet) |

0/5 (0%) |

2/5 (40%) |

2/5 (40%) |

| Growing (60 days old piglet) |

0/4 (0%) |

2/4 (50%) |

0/4 (0%) |

| Finishing (100 days old piglet) |

0/2(0%) |

0/2 (0%) |

0/2(0%) |

| Finishing (130 days old piglet) |

0/2(0%) |

0/2 (0%) |

0/2(0%) |

| Finishing(150 days old (finisher piglet) |

1/2(50%) |

0/2 (0%) |

0/2(0%) |

| Total |

6 |

18 |

5 |

Table 3.

Detection of Influenza A virus by RT-qPCR in environmental samples collected from different locations of a swine farm. The table indicates the sample type, location of collection, cycle threshold (Ct) values for positive samples, and viral subtype detected by RT-PCR. Among the 13 samples analyzed, 4 tested positive for IAV, including two from reclaimed water, one from raw effluent, and one from drinking water. The pH values of each sample are also presented, with mildly alkaline conditions observed in the reclaimed water samples, which may favor viral persistence.

Table 3.

Detection of Influenza A virus by RT-qPCR in environmental samples collected from different locations of a swine farm. The table indicates the sample type, location of collection, cycle threshold (Ct) values for positive samples, and viral subtype detected by RT-PCR. Among the 13 samples analyzed, 4 tested positive for IAV, including two from reclaimed water, one from raw effluent, and one from drinking water. The pH values of each sample are also presented, with mildly alkaline conditions observed in the reclaimed water samples, which may favor viral persistence.

| Sample type |

Collection site building |

Cycle threshold (ct) |

Subtype detected |

pH |

| Reuse Water |

Ponds serving as reservoirs for reuse water |

36.758 |

pH1N1 |

7.8 |

| Reuse Water |

Gestation building |

36.589 |

huH1N1 |

7.9 |

| Reuse Water |

Nursery building |

undetermined |

|

8 |

| Water |

Whole-farm storage tank |

undetermined |

|

- |

| Water |

Farrowing waterer/watering system |

undetermined |

|

7.1 |

| Raw Effluent |

Replacement gilts building |

undetermined |

|

- |

| Raw Effluent |

150-day finishing building |

31.17 |

Not subtyped |

7.6 |

| Raw Effluent |

Post-chemical treatment slaughterhouse |

undetermined |

|

6.5 |

| Raw Effluent |

Nursery building |

undetermined |

|

7.04 |

| Raw Effluent |

Farrowing building |

undetermined |

|

7.27 |

| Raw Effluent |

Farrowing building |

undetermined |

|

7.34 |

| Raw Effluent |

Farrowing building |

36.467 |

Not subtyped |

7.71 |

| Raw Effluent |

Farrowing building |

undetermined |

|

7.69 |

Table 4.

Influenza A virus–positive samples selected for virus isolation. Samples were chosen based on lower Ct values and included nasal and rectal swabs, environmental water samples, and milk or colostrum from lactating sows.

Table 4.

Influenza A virus–positive samples selected for virus isolation. Samples were chosen based on lower Ct values and included nasal and rectal swabs, environmental water samples, and milk or colostrum from lactating sows.

| Sample type |

Collection site building |

Cycle threshold (ct) |

Subtype Detected |

| Effluent |

150-day finishing |

31.17 |

Not performed |

| Rectal swab |

Pregnant 90 days |

36.00 |

Not performed |

| Rectal swab |

Piglet 35 days |

33.72 |

Not performed |

| Rectal swab |

Finishing 130 days |

32.66 |

pH1N1 |

| Nasal swab |

Growing 60 days |

21.58 |

H3N2 |

Table 5.

swIAV strains sequenced in this study with corresponding sample type, subtypes, HA and.

Table 5.

swIAV strains sequenced in this study with corresponding sample type, subtypes, HA and.

| Strains |

Sample type |

Subtype |

HA clade |

NA Clade |

HA_GenBank Accession number |

NA_GenBank Accession number |

| A/swine/Brazil/10 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV876006 |

PV876028 |

| A/swine/Brazil/11 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV875989 |

PV876018 |

| A/swine/Brazil/46 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV875997 |

PV876039 |

| A/swine/Brazil/48 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV875999 |

PV876045 |

| A/swine/Brazil/50 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV876000 |

PV876041 |

| A/swine/Brazil/51 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV876002 |

PV876016 |

| A/swine/Brazil/76 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV875990 |

PV876026 |

| A/swine/Brazil/91 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV875991 |

PV876025 |

| A/swine/Brazil/92 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV875995 |

PV876024 |

| A/swine/Brazil/98 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV875996 |

PV876019 |

| A/swine/Brazil/99 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV875992 |

PV876029 |

| A/swine/Brazil/100 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV875994 |

PV876022 |

| A/swine/Brazil/101 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV876005 |

PV876030 |

| A/swine/Brazil/104 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV876007 |

PV876031 |

| A/swine/Brazil/106 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV875993 |

PV876023 |

| A/swine/Brazil/136 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV876008 |

PV876035 |

| A/swine/Brazil/148 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV875998 |

PV876040 |

| A/swine/Brazil/149 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV876004 |

PV876044 |

| A/swine/Brazil/150 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV876009 |

PV876046 |

| A/swine/Brazil/152 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV876001 |

PV876042 |

| A/swine/Brazil/153 |

Nasal swab |

pH1N1 |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV876003 |

PV876043 |

| A/swine/Brazil/37 |

Nasal swab |

H3N2 |

H3#2 |

N2#6 |

PV876064 |

PV876066 |

| A/swine/Brazil/139 |

Nasal swab |

H3N2 |

H3#2 |

N2#6 |

PV876065 |

PV876033 |

| A/swine/Brazil/158 |

Nasal swab |

H3N2 |

H3#2 |

N2#6 |

PV876063 |

PV876067 |

| A/swine/Brazil/5 |

Nasal swab |

pH1Nx |

H1#2 |

N1#4 |

PV876010 |

PV876021 |

| A/swine/Brazil/28 |

Nasal swab |

pH1Nx |

H1#2 |

- |

PV876013 |

- |

| A/swine/Brazil/72 |

Rectal swab |

pH1Nx |

H1#2 |

- |

PV876011 |

- |

| A/swine/Brazil/118 |

Nasal swab |

pH1Nx |

H1#2 |

- |

PV876012 |

- |

| A/swine/Brazil/127 |

Nasal swab |

pH1Nx |

H1#2 |

- |

PV876014 |

- |

| A/swine/Brazil/128 |

Rectal swab |

H3Nx |

H3#2 |

- |

PV876062 |

- |

| A/swine/Brazil/33 |

Nasal swab |

HxN1 |

- |

N1#4 |

- |

PV876036 |

| A/swine/Brazil/34 |

Nasal swab |

HxN1 |

- |

N1#4 |

- |

PV876037 |

| A/swine/Brazil/36 |

Nasal swab |

HxN1 |

- |

N1#4 |

- |

PV876038 |

| A/swine/Brazil/55 |

Maternity barn effluent |

HxN1 |

- |

N1#4 |

- |

PV876017 |

| A/swine/Brazil/133 |

Nasal swab |

HxN1 |

- |

N1#4 |

- |

PV876032 |

| A/swine/Brazil/134 |

Nasal swab |

HxN1 |

- |

N1#4 |

- |

PV876034 |

| A/swine/Brazil/138 |

Nasal swab |

HxN1 |

- |

N1#4 |

- |

PV876020 |

Table 6.

Distribution of UFMG Influenza A virus samples according to segment and phylogenetic clade. Clade classification was based on maximum-likelihood analysis of the HA and NA genes using reference sequences from Brazilian swine, human-origin H3N2 clades circulating in Brazil (2021–2023), and historical human strains.

Table 6.

Distribution of UFMG Influenza A virus samples according to segment and phylogenetic clade. Clade classification was based on maximum-likelihood analysis of the HA and NA genes using reference sequences from Brazilian swine, human-origin H3N2 clades circulating in Brazil (2021–2023), and historical human strains.

| Segment |

Clade |

No. of UFMG samples |

| H1 |

pH1-#2 (swine-like) |

26 |

| H3 |

3C.2a1b.2a.2a.1 (human-like) |

4 |

| N1 |

pN1-#4 |

28 |

| N2 |

N2-#6 (swine-like) |

1 |

| N2 |

Pre-3C (human-like) |

2 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).